Abstract

Reservoir compartmentalization restricts fluid flow, and failing to recognize or properly understand this phenomenon can significantly impact future decisions and designs in the field. Due to the importance of this issue, various methods have been developed in the literature, and there’s an ongoing effort to develop new strategies for reducing uncertainties in recognizing reservoir compartmentalization. In this study, the moving window root mean square deviation method was developed and applied as a novel approach to evaluate reservoir compartmentalization in the Asmari–Jahrum reservoir of the Nargesi oil field, as a case study. By incorporating a moving-window concept, this method enhances the sensitivity of compositional comparison and provides a more detailed insight into reservoir heterogeneity. The proposed method revealed subtle differences in the crude oil fingerprints obtained from the FTIR spectroscopy of asphaltenes and those obtained from GC fingerprinting. This efficient approach disclosed some heterogeneities in the oil fingerprints across the studied field. The reservoir engineering data, such as bulk PVT properties (e.g., solution GOR and saturation pressure) and reservoir fluid composition, also confirmed these oil composition heterogeneities. The final decision regarding the connectivity between wells was made by integrating all individual data sets to provide a compartmentalization model for the studied field. This model demonstrated that the Asmari–Jahrum reservoir in the Nargesi oil field comprises two distinct zones with no flow communication during production. The activity of paleo highs in the Dezful Embayment, resulting from the reactivation of inherited basement faults, is likely the reason for the observed compartmentalization. Although the proposed method is straightforward for comparing every data set, the results are robust and reliable for inferring reservoir architecture and evaluating reservoir compartmentalization. This phenomenon is a key control on pressure communication, fluid flow behaviour, and the efficiency of field development and reservoir management strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to flow barriers, a compartmentalized reservoir is segregated into distinct flow units, either laterally or vertically. Consequently, fluid movement is restricted within each compartment, preventing free flow across the entire reservoir1,2,3. An intuitive example of a highly compartmentalized reservoir is bubble wrap4. This phenomenon is among the most critical uncertainties, significantly impacting future designs and decisions, which can make a field economically successful or lead to its breakdown. The reservoir compartmentalization also has an essential role in storage studies5,6,7. Hence, obtaining information about the reservoir architecture is crucial in the various life cycles of every field, especially during the appraisal and development stages, to apply practical scenarios in the field1,8,9,10,11.

While various methods have been employed to investigate reservoir compartmentalization, evaluating the heterogeneity of reservoir fluid composition often outperforms other approaches12,13,14. A reservoir without compartmentalization has a homogenous composition in different wells across the reservoir due to molecular diffusion and mixing at geological time scales15. Reservoir geochemistry science utilizes the chemical fingerprint of oil to infer information about the reservoir continuity or compartmentalization. Slentz16 demonstrated the capability of geochemistry science in obtaining information about reservoir compartmentalization and applying it in reservoir management. Kaufman et al.17 developed the GC fingerprinting technique as a new tool in reservoir geochemistry studies. These authors employed this technique in various disciplines, including production allocation and reservoir compartmentalization. Hwang18 employed the oil fingerprint technique to investigate reservoir continuity in the Unity field, Sudan, and examined the influence of rock–fluid interactions on oil fingerprint variations. Larter et al.19 investigated the applications of reservoir geochemistry science in solving different reservoir engineering problems. They suggested this discipline is a cost-effective tool for reservoir management and obtaining information about rock–fluid interactions. Milkov et al.20 addressed reservoir surveillance in the Horn Mountain field, Gulf of Mexico, by integrating different disciplines, including geochemistry, geology, and reservoir engineering data. Ekpo et al.21 performed geochemical fingerprinting by gas chromatography (GC), gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS), and carbon isotope in the western offshore Niger Delta to infer information about the origin of oils and assess reservoir compartmentalization/connectivity.

Although fingerprinting of light-end components of crude oils, especially with GC, is a routine technique, asphaltenes have also become a reliable, straightforward, and comparable method in reservoir continuity studies in recent years. The gradient of asphaltenes measured by the downhole fluid analysis (DFA)22,23,24 or the structural characterization of asphaltenes9,15,25 is used for this purpose. FTIR spectroscopy is the most suitable technique for studying functional groups and characteristics of complex materials such as asphaltenes. This technique is helpful to obtain detailed structural characteristics of asphaltenes. Asemani et al.25 employed structural characteristics of asphaltenes to obtain oil fingerprints. This cost-effective, straightforward technique yields results comparable to other widely used methods. The structural characteristics of asphaltenes have been utilized in conjunction with other routine methods in various case studies to evaluate reservoir compartmentalization9,15,26.

Generally, evaluating reservoir connectivity based on composition heterogeneity involves two critical steps: obtaining detailed compositional information and comparing these characteristics between different samples. Various methods have been suggested in the literature to compare the oil fingerprints. The moving window correlation coefficient is one of the most reliable techniques for comparing oil fingerprints and declaring subtle differences15,25,27,28. This technique uses the Pearson correlation coefficient to measure the similarity or dissimilarity between different samples in successive windows. Despite its inherent benefits, this measuring technique is insensitive to absolute magnitude differences and indicates the degree of linear association between datasets. In contrast, the root mean square deviation (RMSD) quantifies the absolute differences between two datasets, meaning that RMSD captures not only whether two data series vary together but also the actual magnitude of their differences. In this paper, for the first time, the moving window was coupled with the RMSD to reveal even minor deviations in spectral intensity, compositional ratios, or molecular distribution that correlation-based metrics may overlook.

The primary goal of this paper is to propose a novel, efficient, and straightforward procedure for investigating reservoir compartmentalization based on chemical composition heterogeneities. The proposed technique combines the moving window and RMSD techniques to compare the structural characteristics of asphaltenes and GC fingerprints. The moving window RMSD technique was tested to investigate crude oil fingerprint heterogeneities in the Nargesi oil field and to disclose possible compartmentalized regions. The obtained results were also checked using the bulk PVT properties and reservoir fluid composition results.

Geological setting

Most Iranian oil fields are located in the Dezful Embayment, a depression within the Zagros Fold and Thrust Belt. The Lurestan Mountains border this embayment to the northwest, the Fars region to the southeast, and Khuzestan to the northeast29,30. At least 45 oil fields have been explored in this region, containing more than 360 billion barrels of oil, equivalent to over 8% of the world’s reserves. The right-lateral Qatar-Kazerun fault and the left-lateral Balarud fault have played a significant role in forming this depression (Fig. 1). Approximately 95% of oils in this area accumulated in the carbonate reservoirs of Asmari (Early Miocene) and Bangestan Group, which includes the Cenomanian–Turonian age Sarvak formation and the Santonian age Ilam formation31 (Fig. 2). Although many studies have been conducted in this region, the reservoir compartmentalization studies are relatively less common. Given the long history of oil exploration in the Dezful Embayment and the gradual decline in pressure in most fields, reservoir compartmentalization studies are now more critical than ever in this region.

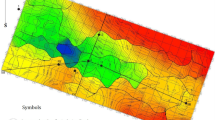

(a) Different structural zones in the Zagros fold and thrust belt showing the Nargesi field in the eastern part of the Dezful Embayment32, (b) the contour map of the Nargesi field based on the top of the Asmari–Jahrum reservoir, illustrating the location of the studied wells. Structural contour map generated by the authors using Surfer (version 23.1.162; Golden Software, LLC; https://www.goldensoftware.com/).

The lithostratigraphic column in different zones of the Zagros fold and thrust belt33.

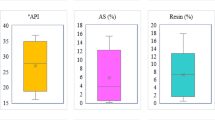

The Nargesi oil field is located in the easternmost part of the Dezful Embayment. It has a length of 39 km and a width of 6–8 km, oriented northwest-southeast. While sufficient evidence on the exact effect of the Kazerun fault on this field is not precisely determined, it appears to exhibit a right-angled movement influenced by the Kazerun fault from the Giskan surface anticline. The main reservoir of this field is the Asmari–Jahrum successions, which contain oil of about 35–37°API and more than 1% sulfur content. The Bangestan group is a subsidiary in this field; oil traces have recently been reported.

Materials and methods

Sample

Six oil samples were collected from different wells across the Nargesi field to characterize the reservoir architecture of the Asmari–Jahrum reservoir. These wells are produced from a similar reservoir layer and represent spatial variability across the field. The studied samples capture the main heterogeneities within the Asmari–Jahrum reservoir in the Nargesi field. The location of studied wells are illustrated in Fig. 1, and the samples are labelled NI-AS-1 to NI-AS-6.

To ensure data reliability, high-purity reagents were used for asphaltenes extraction and FTIR analysis, including n-hexane (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥ 97.0%, HPLC-grade), Toluene (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥ 99.9%, HPLC-grade), and KBr (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥ 99.999%, HPLC-grade).

Asphaltene extraction

Asphaltene extraction from the studied samples (e.g., NI-AS-1 to NI-AS-6) was performed according to the ASTM D 6560 standard34. Crude oil and n-hexane solvent were mixed (1 g: 30 ml) and refluxed for 1 h. The mixture was sealed and placed in a dark location overnight before being filtered with Whatman No. 42 filter paper. Impurities were washed with hot n-hexane, and the pure asphaltenes were recovered using a toluene solvent. The solvent was evaporated, and the asphaltenes were heated at 100 °C for 30 min. The asphaltene content of all samples averages 1.23%, ranging from 0.74 to 1.65%. The consistency and repeatability of the asphaltenes yield were calculated by extracting one sample six times. The uncertainty in the asphaltenes yield was ± 0.2%.

FTIR spectroscopy

Asphaltenes were pulverized and mixed with the KBr powder (1 wt%: 100 wt%). The mixture was pressed under high pressure to obtain a transparent pellet. The FTIR spectra were recorded on the pellets using a Bruker Tensor 27, with 32 scans in the 4000–400 cm−1 range and a resolution of 4 cm−1. Each sample was analyzed three times, and the average value was then further processed. The second derivative was calculated using the Savitzky–Golay (S–G) derivative method for spectra to remove the effect of baseline variations before processing.

The comparison threshold was calculated based on the repeatability and reproducibility of samples by performing asphaltene extraction and FTIR analysis six times on a single sample.

High-resolution gas-chromatography (HRGC) analysis

A small aliquot of crude oil was injected into an HP 5890 Series II gas chromatograph with an FID detector. The temperatures of the detector and injector were set both at 300 °C. A DB-1 capillary column (100 m × 0.1 mm inner diameter and 0.25 µm film thickness) was used to separate the different components and achieve baseline resolution. The oven temperature program was set from 30 to 320 °C at a rate of 3 °C/min and held at the final temperature for 20 min. Quantitative calibration was performed using a standard hydrocarbon mixture (n-C10 to n-C40) and certified reference oils to ensure accurate comparison of retention times and peak areas. The reproducibility and accuracy of the chromatographic results were validated through triple analyses of a sample, yielding deviations of less than ± 2% in peak ratio measurements.

Moving window root mean square deviation (MW-RMSD) method

The moving window method examines the similarity or dissimilarity between successive windows of a data series, rather than comparing the entire series at once. This approach provides a detailed comparison between different data series, and its efficiency has been well-established35. The standard comparison parameter in each window is the Pearson correlation coefficient. This similarity index ranges from − 1 to 1, illustrating the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two compared data series. Data series with higher similarity have values closer to 1 or − 1. A value of 1 indicates a direct linear relationship, while a value of − 1 implies an inverse linear relationship. In other words, the data series reveals harmonious and uniform changes.

Another common similarity measurement index is root mean square deviation (RMSD). This parameter measures the quadratic mean of the differences between two data series. This non-negative parameter is routinely expressed as a percentage (%), indicating the deviation and differences between the two compared data series. Although the Pearson correlation coefficient is valuable for evaluating the strength and direction of a linear relationship, RMSD is more effective for quantitatively measuring the actual difference between two data series. The RMSD parameter is also important when the relationship is non-linear, and the magnitude of the difference is critical.

Here, the RMSD was calculated in successive windows to improve the pairwise comparison of samples. The method is called Moving Window-Root Mean Square Deviation (MW-RMSD). The maximum and average RMSD values (Max-RMSD and Ave-RMSD) across all moving windows were used to determine the similarity or dissimilarity of samples. The repeatability of the analysis was employed to define the comparison threshold. Samples with similar fingerprints are those for which both the Max-RMSD and Ave-RMSD values are lower than the specified threshold.

Results and discussion

FTIR assignments

The raw FTIR spectra and the second derivative of asphaltenes are illustrated in Fig. 3. The general pattern of all spectra is similar, indicating that all samples possess identical functional groups, though their concentrations differ. Detailed assignment of FTIR spectra can be found elsewhere36,37; general characteristics are mentioned here. A broad band above 3100 cm−1 corresponds to O–H and N–H functional groups. This peak may also appear due to the moisture absorption by the prepared pellet during analysis. A small shoulder at 3050 cm−1 is related to the Aromatic C–H stretching vibrations, and this peak resolved to two peaks at about 3050 cm−1 and 3018 cm−1 in the second derivative spectra. Aliphatic functional groups, such as methyl, methylene, and methine groups, generate strong peaks in the 3000–2750 cm−1 region. Carbonyl (C=O) stretching vibrations associated with oxygen-containing functional groups appear at 1730 cm−1. Aromatic C=C stretching produces a characteristic signal at 1600 cm−1, while the 1460 cm−1 and 1375 cm−1 bands correspond to CH2 and CH3 groups, respectively. A peak at 1030 cm−1 related to the Sulfoxide (S=O) functional groups and the C–H out-of-plane bending (wagging) vibrations from aromatic compounds are visible in the region below 900 cm−1. Methylene rocking vibrations in straight-chain alkanes (> 4 C atoms) arise as a small shoulder at 724 cm−1.

FTIR spectra (a) and second-derivative spectra (b) for the studied asphaltene samples from the Nargesi field. In the raw FTIR spectra, the characteristic bands appear as peaks, whereas in the second-derivative spectra, they appear as valleys. The baseline variations are eliminated in the second derivative spectrum, and the comparison of different samples is more reliable.

Reservoir compartmentalization assessment

Reservoir compartmentalization studies are vital in the appraisal and development stages of a field to reduce uncertainties20,38. Our understanding of reservoir architecture significantly influences oil in place and reserve estimation, decisions on the number and location of wells, the design of surface facilities, and the choice of reservoir operation scenarios. The underestimation or overestimation of each item directly impacts the project’s profit and economics. The presence of flow barriers is the primary reason for reservoir compartmentalization, which, in turn, influences the reservoir’s architecture. These flow barriers restrict fluid flow between wells, leading to chemical composition heterogeneity across the reservoir. This results from limitations on fluid mixing and the prevention of fluid compositional equilibrium over geological time scales. Hence, the well-organized solution to inferring reservoir compartmentalization involves comparing the chemical composition of crude oils in different wells, or, more precisely, comparing oil fingerprints. Oil fingerprints refer to the yield and distribution of various chemical components in crude oil4.

Various methods have been developed to obtain oil fingerprints from different aspects. While GC fingerprinting is favourable for obtaining oil fingerprints from the light-end components of crude oil, the structural characteristics of asphaltenes are also applicable in deriving oil fingerprints from the heavy-end components. PVT data are invaluable for acquiring bulk characteristics of crude oils. Since every technique has pros and cons, integrating different methods benefits from the synergy of individual strategies, with each technique representing a piece of the reservoir architecture puzzle. Efficient and straightforward methods for comparing oil fingerprints are ongoing attempts in reservoir compartmentalization studies to enhance heterogeneity assessment.

In this paper, the oil fingerprint, derived from the structural characteristics of asphaltenes, and the GC fingerprinting were compared across different wells of the Asmari-Jahrum reservoir in the Nargesi field, utilizing the proposed moving window-root mean square deviation (MW-RMSD) method as a novel and efficient technique. Finally, the results were correlated with the PVT properties and fluid composition data.

Structural characteristics of asphaltenes

Asphaltenes represent the heaviest and most polar fraction of crude oil. This fraction of crude oil is not defined by its inherent structure or characteristics but is primarily regarded as a solubility class39,40,41. Thus, asphaltenes are a fraction of oil that is soluble in aromatic solvents (e.g., toluene and benzene) and insoluble in light n-alkanes (e.g., n-pentane, n-hexane, and n-heptane). Asphaltenes pose numerous challenges in the oil industry and are among the most problematic compounds37,42. These problems stem from the self-association of asphaltenes, which leads to precipitation43. If precipitation occurs in the reservoir, permeability will be reduced due to plugging pores and pore throats, and wettability reversal becomes a predictable issue. Asphaltene precipitation also causes plugging of the wellbore, tubing, surface facilities, or pipelines. Fouling of catalysts or catalyst poisoning is another associated problem44,45,46. While asphaltenes are mostly known as detrimental compounds, they have been demonstrated to be valuable in geochemical studies. They are primarily applied to obtain oil fingerprints and assess reservoir compartmentalization9,15,47.

Here, the oil fingerprints were derived from the structural characteristics of asphaltenes using the FTIR technique. Then, the MW-RMSD technique was applied to assess heterogeneities in these oil fingerprints. Asphaltene extraction and FTIR analysis were performed on one sample six times. These replicates (e.g., R1–R6) were treated as separate samples to measure repeatability and establish a threshold for determining the similarity or dissimilarity of other samples. Eleven distinctive bands were selected from the 2nd derivative spectra of FTIR, including 3052, 3018, 2958, 2923, 2850, 1600, 1460, 1375, 862, 808, and 746 cm−1. Subsequently, 110 peak ratios were calculated by dividing the height of each band by every other bands. Different samples were compared based on these 110 characteristic peak ratios. The optimum window width in the moving window was determined from replicate samples, as explained elsewhere25. The width of 11 points was found to be the optimum window width for the studied samples from the Nargesi field. The maximum values of Max-RMSD and Ave-RMSD across all windows for replicate samples were calculated and used as a dividing line to distinguish between similar and dissimilar samples. This means that the maximum permissible difference between similar samples is at this threshold, and a higher difference implies dissimilar samples. The measured threshold value, Max-RMSD and Ave-RMSD for the studied samples were 20% and 14%, respectively.

A pairwise comparison of samples was conducted to identify heterogeneities, and the comparison results based on Ave-RMSD and Max-RMSD are presented in Fig. 4a and b. These figures illustrate the difference between different samples based on the MW-RMSD method. The green area shows the threshold of repeatability for similar samples.

The comparison of structural characteristics of asphaltenes based on Ave-RMSD (a) and Max-RMSD (b) for the studied samples from the Nargesi field. The figures show the difference for each pair of samples, and the samples with an RMSD higher than the threshold (above the green area) are considered different.

When two samples have an RMSD higher than the threshold, it signifies the difference in oil fingerprints and the lack of flow communication between these wells during production. At first glance, composition heterogeneity is evident in the Asmari–Jahrum reservoir of the Nargesi field, as some samples exceed the threshold in Fig. 4a and b. For example, the NI-AS-1 sample has a fingerprint similar to the NI-AS-3, NI-AS-4, and NI-AS-5 samples, as determined by the Ave-RMSD and Max-RMSD.

GC fingerprinting

GC fingerprinting is a well-established geochemistry method for assessing interconnectivity between wells and obtaining information about reservoir architecture. This method aims to disclose slight differences in oil fingerprints. Hence, it integrates analytical and interpretive techniques to differentiate and measure various components in a crude oil sample, produce higher-resolution measurements, and interpret them efficiently4. Therefore, analytical conditions, including capillary column dimensions, temperature, and flow rates, should be optimized to minimize co-elution and enhance repeatability and reproducibility. The interpretation of GC fingerprint involves measuring several hundred inter-paraffin peak ratios, and generally, this method focuses on differences rather than similarities. Despite its capabilities, this method requires longer analysis times and higher costs than FTIR analysis of asphaltenes due to specialized analytical conditions. Due to these challenges, sample selection should be conducted with caution.

The studied samples from the Asmari–Jahrum reservoir of the Nargesi field were also evaluated using the GC fingerprinting method here. Several hundred peak ratios based on neighbouring inter-paraffin peaks were calculated, and more than 450 peak ratios with greater differences between samples were selected for comparison of oil fingerprints in different wells. The comparison of oil fingerprints was carried out using the MW-RMSD method. The thresholds were determined based on the replicate analysis of a sample. The measured threshold value, Max-RMSD and Ave-RMSD for the studied sample sets were 20% and 8.5%, respectively. The comparison results based on Ave-RMSD and Max-RMSD are shown in Fig. 5a and b. Compositional heterogeneity between different samples is also evident based on the light-end component of crude oils. For example, the NI-AS-1 sample has a distinct fingerprint from the NI-AS-2 and NI-AS-6 samples, as determined by the Ave-RMSD and Max-RMSD.

Bulk pressure/volume/temperature (PVT) properties and fluid composition data

PVT properties and fluid composition data are valuable reservoir engineering tools for inferring information about reservoir fluid heterogeneities. Three representative bottom-hole samples from NI-AS-1, NI-AS-2, and NI-AS-5 wells were analyzed to measure PVT properties and fluid composition. Bulk PVT properties, including solution GOR and saturation pressure, were compared between different samples using the RMSD method. The simple method of RMSD, rather than the moving window RMSD, was employed due to the smaller data series. The results of the pairwise comparison of different samples for solution GOR and saturation pressure were illustrated in Fig. 6a and b, respectively. A threshold of 10% was established to determine the similarity or dissimilarity of the samples. Both figures exhibit a similar pattern: samples from NI-AS-1 and NI-AS-5 have identical properties and are entirely different from the NI-AS-2 sample. The reservoir fluid composition including CO2, N2, H2S, C1, C2, C3, i-C4, n-C4, i-C5, n-C5, C6, C7, C8, C9, C10, C11, and C12+ was also compared for the these three studied wells. The reservoir fluid composition also shows differences for NI-AS-1 and NI-AS-5 compared to NI-AS-2 (Fig. 6c).

The comparison of solution GOR (a), saturation pressure (b), and reservoir fluid composition (c) based on RMSD for studied samples from the Nargesi field. The figures show the difference for each pair of samples, and the samples with an RMSD higher than the threshold (above the green area) are considered different.

Compartmentalization model

While different individual data sets exhibit dissimilarities between various wells, indicating reservoir compartmentalization, multiple factors can influence the effectiveness of each data set in assessing this phenomenon. However, integrating multiple data sets is crucial for achieving synergy and reducing uncertainties. Here, various data series—including structural characteristics of asphaltenes, GC fingerprinting, bulk PVT properties, and reservoir fluid composition—were individually employed to evaluate fluid heterogeneity between different wells. Figure 7 summarizes the pairwise comparison of different wells in the Asmari-Jahrum reservoir of the Nargesi field based on these techniques. For the structural characteristics of asphaltenes and GC fingerprints, green cells indicate that both Ave-RMSD and Max-RMSD for the two compared samples are lower than the threshold, signifying fingerprint similarity. Red cells imply the reverse conclusion. For PVT properties and reservoir fluid composition, differences higher than 10% of RMSD were considered different. The integration of these results is presented in the last column. Variations in PVT properties, fluid composition, and other geochemical information are reliable indicators of reservoir compartmentalization and a lack of fluid communication during production20.

The studied samples appear to belong to two distinct zones. The first zone includes wells NI-AS-1, NI-AS-3, NI-AS-4, and NI-AS-5, while the second zone includes wells NI-AS-2 and NI-AS-6. Figure 8 shows a schematic of these distinct compartments in the Asmari–Jahrum reservoir of the Nargesi field.

The schematic of different reservoir compartments in the Asmari-Jahrum reservoir from the Nargesi field. A fluid barrier separates the two distinct zones, and the fluid community is not established. Structural contour map generated by the authors using Surfer (version 23.1.162; Golden Software, LLC; https://www.goldensoftware.com/).

The Zagros fold and thrust belt is an active tectonic area that has experienced several geological events. One of the most critical tectonic activities is the reactivation of inherited basement faults resulting from the closure of the Neo-Tethys ocean during the Mesozoic. The reactivation of basement faults led to the formation of several paleo-highs in the Zagros Basin, especially in the Dezful Embayment48,49. The Kazerun High passes through the Nargesi field, and the observed reservoir compartmentalization is likely related to this structural activity.

Conclusions

Reservoir compartmentalization remains a critical uncertainty in field development and management. In this study, a novel moving window- root mean square deviation (MW-RMSD) method was introduced and applied to evaluate fluid compositional heterogeneity in the Asmari–Jahrum reservoir of the Nargesi oil field, SW Iran. The main findings are summarized as follows:

-

a.

The proposed MW-RMSD technique by integrating the moving window approach with the RMSD index proved highly sensitive in detecting subtle variations in GC and FTIR-derived oil fingerprints, outperforming the conventional RMSD method.

-

b.

Quantitative fingerprint comparisons revealed distinct lateral heterogeneity and confirmed the presence of two main reservoir compartments separated by an NE–SW trending barrier, likely related to reactivated basement faults.

-

c.

Integration of the MW-RMSD technique for comparison of geochemical fingerprints with reservoir engineering data provided a consistent compartmentalization model, demonstrating the method’s robustness and cross-applicability to different datasets and reservoirs.

-

d.

The strong agreement between the independently applied techniques validates the presence of well-defined flow barriers with high confidence. This convergence provides decisive evidence that the proposed methodology can reliably resolve reservoir compartmentalization, even under complex geological conditions. Therefore, the observed consistency should be regarded as a robust validation of both the detection accuracy and the predictive capability of the workflow.

In summary, this study highlights the MW-RMSD approach as a reliable, straightforward, and efficient technique for assessing reservoir connectivity and compositional heterogeneity in any reservoir, especially complex reservoir systems, and any datasets.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

References

Smalley, P. C. & Muggeridge, A. H. Reservoir compartmentalization: Get it before it gets you. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 347, 25–41 (2010).

Jolley, S. J., Fisher, Q. J. & Ainsworth, R. B. Reservoir compartmentalization: An introduction. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 347, 1–8 (2010).

Dembicki, H. Reservoir geochemistry. In Practical Petroleum Geochemistry for Exploration and Production (ed. Dembicki, H.) 215–244 (Elsevier, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-95924-7.00007-7.

Elshahawi, H., Hashem, M. N., Mullins, O. C. & Fujisawa, G. The missing link-identification of reservoir compartmentalization through downhole fluid analysis. In SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition (SPE, Dallas, Texas, 2005).

Al-Khdheeawi, E. A., Vialle, S., Barifcani, A., Sarmadivaleh, M. & Iglauer, S. Impact of reservoir wettability and heterogeneity on CO2-plume migration and trapping capacity. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 58, 142–158 (2017).

Al-Khdheeawi, E. A., Vialle, S., Barifcani, A., Sarmadivaleh, M. & Iglauer, S. Influence of injection well configuration and rock wettability on CO2 plume behaviour and CO2 trapping capacity in heterogeneous reservoirs. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 43, 190–206 (2017).

Al-Khdheeawi, E. A., Vialle, S., Barifcani, A., Sarmadivaleh, M. & Iglauer, S. Effect of wettability heterogeneity and reservoir temperature on CO2 storage efficiency in deep saline aquifers. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 68, 216–229 (2018).

Muggeridge, A. H., Smalley, P. C. et al. A diagnostic toolkit to detect compartmentalization using time-scales for reservoir mixing. In Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference (2008).

Asemani, M., Rabbani, A. R. & Sarafdokht, H. An efficient and straightforward procedure for rapid investigation of reservoir compartmentalization by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of asphaltenes. SPE J. 28, 1–15 (2022).

Didi, C. N., Osinowo, O. O. & Akpunonu, O. E. Reservoir characterization of Yolde Formation, Kolmani Field, Gongola Basin, Nigeria using pressure, temperature, PVT, and well log data. Sci. Rep. 15, 20742 (2025).

Hendawy, Y., Elkadi, H. H. & Mostafa, T. FMI and 2D seismic integration for fractured basement reservoir assessment, Geisum area, Gulf of Suez. Sci. Rep. 15, 23998 (2025).

Dong, C. et al. Evaluation of reservoir connectivity from downhole fluid analysis, asphaltene equation of state model and advanced laboratory fluid analyses. In SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition (2012).

Zuo, J. Y. et al. Advances in the Flory–Huggins–Zuo equation of state for asphaltene gradients and formation evaluation. Energy Fuels 27, 1722–1735 (2012).

Chen, J. Deepwater reservoir compartmentalization: Causes, impacts on production, and methods of identification. In Offshore Technology Conference (2013).

Asemani, M. & Rabbani, A. R. Crude oil fingerprint heterogeneity assessment by investigation of asphaltene subfractions: Implementation for reservoir continuity evaluation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 195, 107925 (2020).

Slentz, L. W. Geochemistry of reservoir fluids as a unique approach to optimum reservoir management. In Middle East Technical Conference and Exhibition, 9–12 March, Bahrain. SPE-9582-MS (1981). https://doi.org/10.2118/9582-MS

Kaufman, R. L., Ahmed, A. S. & Hempkins, W. B. A New Technique for the Analysis of Commingled Oils and Its Application to Production Allocation Calculations (1987).

Hwang, R. J. Reservoir connectivity and oil homogeneity in a large-scale reservoir. Proc. Middle East Geosci. Conf. 2, 529–541 (1994).

Larter, S. R. et al. Reservoir geochemistry: A link between reservoir geology and engineering?. SPE Reserv. Eng. 12, 12–17. https://doi.org/10.2118/28849-P (1997).

Milkov, A. V. et al. Compartmentalization and time-lapse geochemical reservoir surveillance of the Horn Mountain oil field, deep-water Gulf of Mexico. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 91, 847–876 (2007).

Ekpo, B. O., Essien, N., Neji, P. A. & Etsenake, R. O. Geochemical fingerprinting of western offshore Niger Delta oils. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 160, 452–464 (2018).

Betancourt, S. S. et al. Predicting downhole fluid analysis logs to investigate reservoir connectivity. In International Petroleum Technology Conference (2007).

Mullins, O. C. et al. The colloidal structure of crude oil and the structure of oil reservoirs. Energy Fuels 21, 2785–2794 (2007).

Pomerantz, A. E. et al. Assessing reservoir connectivity through biomarker and bulk compositional gradient analysis. In SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition (2010).

Asemani, M., Rabbani, A. R. & Sarafdokht, H. Evaluation of oil fingerprints similarity by a novel technique based on FTIR spectroscopy of asphaltenes: Modified moving window correlation coefficient technique. Mar. Pet. Geol. 120, 104542 (2020).

Asemani, M., Rabbani, A. R. & Sarafdokht, H. Implementation of an integrated geochemical approach using polar and nonpolar components of crude oil for reservoir-continuity assessment: verification with reservoir-engineering evidences. SPE J. 26, 1–18 (2021).

Chu, X.-L., Xu, Y.-P., Tian, S.-B., Wang, J. & Lu, W.-Z. Rapid identification and assay of crude oils based on moving-window correlation coefficient and near infrared spectral library. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 107, 44–49 (2011).

Li, J., Chu, X., Tian, S. & Lu, W. The identification of highly similar crude oils by infrared spectroscopy combined with pattern recognition method. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 112, 457–462 (2013).

Bordenave, M. L. & Huc, A. Y. The Cretaceous source rocks in the Zagros foothills of Iran. Rev. L’inst. Fr. Pet. 50, 727–752 (1995).

Motiei, H. Geology of Iran, the stratigraphy of zagros. In Geological Survey of Iran (In Persian) 536pp (1993).

Eftekhari, S. H., Memariani, M., Maleki, Z., Aleali, M. & Kianoush, P. Hydraulic flow unit and rock types of the Asmari Formation, an application of flow zone index and fuzzy C-means clustering methods. Sci. Rep. 14, 5003 (2024).

Esrafili-Dizaji, B. & Rahimpour-Bonab, H. Carbonate reservoir rocks at giant oil and gas fields in SW Iran and the adjacent offshore: A review of stratigraphic occurrence and poro-perm characteristics. J. Pet. Geol. 42, 343–370 (2019).

James, G. A. & Wynd, J. G. Stratigraphic nomenclature of Iranian oil consortium agreement area. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 49, 2182–2245 (1965).

ASTM D6560-17. Standard Test Method for Determination of Asphaltenes (Heptane Insolubles) in Crude Petroleum and Petroleum Products (ASTM International, West Conshohocken, 2017). www.astm.org.

Asemani, M. & Rabbani, A. R. A novel and efficient chemometric approach to identifying oil families by saturate biomarker data and FTIR spectroscopy of asphaltene subfractions. Mar. Pet. Geol. 124, 104838 (2021).

Pavia, D. L., Lampman, G. M., Kriz, G. S. & Vyvyan, J. A. Introduction to Spectroscopy 4th edn. (Cengage Learning, 2008).

Asemani, M. & Rabbani, A. R. Detailed FTIR spectroscopy characterization of crude oil extracted asphaltenes: Curve resolve of overlapping bands. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 185, 106618 (2020).

Go, J., Smalley, P. C. & Muggeridge, A. Appraisal of reservoir compartmentalization using fluid mixing time-scales: Horn Mountain Field, Gulf of Mexico. Pet. Geosci. 18, 305–314 (2012).

Lehne, E., Dieckmann, V., di Primio, R., Fuhrmann, A. & Horsfield, B. Changes in gas composition during simulated maturation of sulfur rich type II-S source rock and related petroleum asphaltenes. Org. Geochem. 40, 604–616 (2009).

Painter, P., Veytsman, B. & Youtcheff, J. Guide to asphaltene solubility. Energy Fuels 29, 2951–2961 (2015).

Gray, M. R. et al. Distributed properties of asphaltene nanoaggregates in crude oils: A review. Energy Fuels 35, 18078–18103 (2021).

Mohammed, I., Mahmoud, M., Al Shehri, D., El-Husseiny, A. & Alade, O. Asphaltene precipitation and deposition: A critical review. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 197, 107956 (2021).

Rashid, Z., Wilfred, C. D., Gnanasundaram, N., Arunagiri, A. & Murugesan, T. A comprehensive review on the recent advances on the petroleum asphaltene aggregation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 176, 249–268 (2019).

Mullins, O. C., Sheu, E. Y., Hammami, A. & Marshall, A. G. Asphaltenes, Heavy Oils, and Petroleomics (Springer, 2007).

Leyva, C., Ancheyta, J., Berrueco, C. & Millán, M. Chemical characterization of asphaltenes from various crude oils. Fuel Process. Technol. 106, 734–738 (2013).

Tirjoo, A., Bayati, B., Rezaei, H. & Rahmati, M. Molecular dynamics simulations of asphaltene aggregation under different conditions. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 177, 392–402 (2019).

Asemani, M. & Rabbani, A. R. Oil-oil correlation by FTIR spectroscopy of asphaltene samples. Geosci. J. 20, 273–283 (2016).

Elyad, S., Yassaghi, A. & Najafi, M. Structural evolution of anticlines over the hendijan paleo-high in the northwestern Persian Gulf: Insights into the influence of inherited basement faults. Mar. Pet. Geol. 180, 107479 (2025).

Navidtalab, A., Mehrabi, H., Shafaii Moghadam, H. & Rahimpour-Bonab, H. Strontium isotope proxy of sedimentological records reveals uplift and erosion in the Southeastern Neo-Tethys ocean during the late Cretaceous. Sci. Rep. 14, 3499 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to Assistant Editor, Dr. Shivani Dhokne, and Editorial Board Member, Dr. Oyinkepreye Orodu, for their thorough and constructive comments. Special thanks go to the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful reviews and constructive suggestions, which helped to improve the quality of this article. The authors would like to extend their thanks to the R&D department of the National Iranian South Oil Company (NISOC) for their cooperation. Dr. Hashem Sarafdokht is also gratefully acknowledged for his help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA: Conceptualization, validation, writing—review and editing, supervision, investigation, project administration. MHSK: Methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft. ARR: Supervision, validation, writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Asemani, M., Kouhanjani, M.H.S. & Rabbani, A.R. Developing a straightforward and robust approach for investigating reservoir compartmentalization based on chemical composition heterogeneities. Sci Rep 15, 44342 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27994-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27994-8