Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the impact of forest cover loss on the composition of vector and non-vector mosquitoes and to identify potential thresholds for some mosquito species across the gradient of forest cover loss. The study was carried out in an area of the Cerrado hotspot in Brazil. We used linear and non-linear models to assess the response of mosquito abundance to forest cover loss. We registered a total of 6910 specimens and detected a positive effect of the amount of forest cover on the total abundance of mosquitoes in the landscapes. In addition, non-vector species are more susceptible to landscapes with low forest cover, which negatively affects the abundance of these species. On the other hand, the high abundance of vector species was associated with a low percentage of native forest cover. The threshold values ranged from 12.5 to 81% of the forest cover and presented different values for the 14 species. We emphasize that as deforestation increases in the region, there is a clear loss of species and an increase in the presence of potential disease vectors for animals and humans, which is associated with potential implications for the emergence of arboviruses and for public health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The dynamics of vectors of diseases, such as mosquitoes, and landscape changes are among the most critical issues in tropical environments1,2,3. The ecological and environmental conditions that influence the abundance of these vector-borne diseases are of public interest because of their public health importance4. The conversion of natural landscapes to anthropogenic landscapes has caused negative effects on biodiversity, including population declines in many species5,6, but a significant increase in the number of some mosquitoes7, particularly anthropophilic species8,9.

Deforestation contributes to the displacement of vectors and their etiological agents, providing contact between wild animals, human populations, and their domestic animals10,11,12. These interactions favor several zoonoses, mainly in settlements and peripheries13. Although some studies agree that habitat loss drastically decreases populations of forest-dependent mosquito species14,15,16, how different mosquito species are affected across gradients of deforestation, from the most preserved environment to the most altered environment, is poorly known17.

The conversion of natural ecosystems to other uses is highly important in the tropics. The land that is converted is used for animal and agricultural production, particularly cattle18,19,20, and for vegetal commodities, such as soy, oil palm, and corn. Brazil ranks first as an exporter of grains, meat and other animal and vegetal products21, and this demand creates an enormous amount of land for production, resulting from deforestation22. In some regions, such as the Brazilian Cerrado, deforestation is expected to increase dramatically in the coming years, particularly due to the international demand for meat and grains21,23,24. The converted lands may provide the formation of habitats favorable to the proliferation of mosquitoes that transmit human infections25.

Our knowledge is still limited in identifying the levels of transformation that generate critical changes in ecological systems26,27, that is, if the mosquito communities change gradually (following a given trend) or if the changes are drastic and sudden. These ecological systems are vulnerable to irreversible change when the key properties of the system are pushed over thresholds. Perhaps the most important of these predictors is the total amount of native vegetation remaining28.

Many studies have focused on the identification of non-linear responses of biodiversity elements to the proportion of native vegetation, a pattern in which the response variable (e.g., richness or community composition) has a disproportional effect on a certain value of native vegetation (i.e., thresholds)27,29,30,31. However, not all biodiversity responses to environmental changes exhibit unique thresholds, which apparently occur within certain amounts of the environmental gradient (usually when habitat loss exceeds 60%) and are modulated by the landscape configuration28. In addition, the shape and dynamics of the matrix around the fragments (usually in the form of agricultural areas) and the quantity and type of domestic animals can play important roles in the response of the zoophilic and anthropophilic mosquito community. For example, forest cover loss causes a decrease in mosquito biodiversity and an increase in the abundance of vector species, such as the malaria vector Anopheles darlingi15,17. However, the identification of the level of deforestation that causes disproportional changes in mosquito communities or if these changes are gradual (linear) is poorly known.

With successive modifications of habitats, impacts on the dynamics of infectious diseases are expected, especially those associated with vectors and reservoirs in forests, such as malaria, leishmaniasis and arboviruses32. Thus, the behavior of species associated with ecological factors allows for a better characterization of the interrelationships between vector species or potential vectors and human populations and their domestic animals that settle in a region33,34,35. Therefore, understanding how mosquitoes respond to landscape gradients is a priority for inferring the potential of disease transmission, which is key to planning more sustainable landscapes in the tropics, including reducing disease risk for humans and animals, maintaining biodiversity and agricultural production.

In this research, our primary goals are twofold: i) to discern the impact of forest cover loss on the abundance of both vector and non-vector mosquitoes within a region in the Cerrado hotspot and ii) to identify potential thresholds for each mosquito species. We hypothesize that the richness and abundance of mosquitoes are positively affected by native forest cover, with a positive effect on the abundance of vector species. In addition, considering that mosquito species may have different ecological requirements and levels of dependence on forests (e.g., larval habitats, hosts)36, we expected that each species would respond differently to forest cover gradients and that sylvatic mosquitoes would be negatively affected by forest loss.

Materials and methods

Study area

The study was carried out in the Bodoquena Plateau region, the southwest region of the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, specifically in the area studied by the Long-Term Ecological Research—Planalto da Bodoquena. The region has forested and well-preserved environments, such as Serra da Bodoquena National Park, and fragmented areas, demonstrating landscape complexity and environmental heterogeneity37,38. The vegetation in the region is composed of remnants of the Atlantic Forest and is mostly from the Cerrado biome (Brazilian savanna). The Brazilian Cerrado is characterized by a high level of endemism, with a high number of species39,40; moreover, it is considered a hotspot of biodiversity41,42 (Fig. 1). The region has been threatened by anthropogenic land use changes on a large scale, especially with the expansion of agriculture and livestock43,44.

Spatial distribution of the 21 landscapes in the Bodoquena Plateau, Cerrado hotspot in Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. The map was created via QGIS 3.16.5 (https://download.qgis.org).

The regional climate is tropical, as determined by the Köppen-Geiger classification, with wet summers and dry winters45. The average annual precipitation varies from 1400 to 1600 mm, and the climate has two distinct seasons: rainy (October–March) and dry (April-September). The annual average temperatures vary between 22 and 26 °C, with the relative humidity of the air reaching a maximum of 80%46.

Mosquito collection

Mosquitoes were collected between February and July 2019 in 21 landscapes, using CDC and Shannon light traps. For each landscape, a CDC light trap was installed in the tree canopy, a CDC trap was installed near the ground, and a Shannon light trap was installed inside the forest, approximately 200 m away from each other. Castro manual suction and tubes impregnated with ethyl acetate from 4:00 to 10:00 pm in each landscape (performed next to Shannon’s trap), with a sampling effort of 6 h in each landscape for the three collection techniques, totaling 126 h of sampling for all landscapes. All the samples were collected with personal protective equipment, minimizing contact between the mosquitoes and the collectors.

The mosquitoes were sent for identification at the Laboratório de Malária e Dengue of the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA) and will be deposited in the entomological collection of the Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS) and the Laboratório de Malária e Dengue (INPA). The species names followed the recommendations of Reinert85, according to the list of valid species by Harbach86. The nomenclature of species of the genus Aedes followed the taxonomic classification recommended by87. Collections were authorized under SISBIO permit 58,866 and mosquitoes were identified using specialized dichotomous Keys47,48. The species collected were deposited in the Zoological Reference Collection of the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (ZUFMS) (ZUFMS-DIP01532 to ZUFMS-DIP01595).

Landscape analysis

We defined circular concentric buffers with a radius of 500 m around each sampling point to estimate the percentage of native vegetation. This buffer represents an approximate area of dispersion movement per day for some genera (e.g., Anopheles, Aedes, Culex, Haemagogus, Sabethes)49,50. To classify land use, we used 2019 images from the Sentinel-2 Level-1C sensor with a 10-m spatial resolution51. After the images were processed, bands 3, 4 and 8 (green, red and near infrared, respectively) were merged to perform a semiautomatic classification in Quantun GIS version 3.4.13—Madeira—using the Plugin SCP (semiautomatic classification plugin) version 6.4.0 Greenbelt. The classification resulted in binary data (e.g., forest or non-forest) and the classification accuracy was tested via the SCP plugin in Quantum GIS using Google Earth images as references (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S1).

The forest cover gradient ranged from 99 to 10% around 21 points on the Bodoquena Plateau, which is a Cerrado hotspot in Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. The image was created using Adobe Illustrator 2020 (https://www.adobe.com/ br/products/illustrator/).

Abiotic variables

We characterized the areas of each sampling locally in terms of relative humidity and air temperature, using a digital thermohygrometer model 7663 Incoterm. In addition, we also measured the distance (meters) between the traps and the nearest water body. These lotic water bodies, consisting of streams, canals, and small rivers, had flowing water and intersected the landscapes studied. Although not as accurate, daily precipitation amounts (mm) were obtained from automatic weather stations in the cities of Bonito and Bodoquena, available in the Meteorological Database for Teaching and Research (BDMEP) of the National Institute of Meteorology52. All these variables served to characterize our study area in terms of abiotic variables and were not necessarily used in our models of richness and abundance in relation to vegetation cover itself. Data available in the supplementary material.

Data analyses

Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) was performed using the vegan package53 as an exploratory analysis to elucidate the relationships between environmental variables (forest cover, distance of the water body and air temperature) and mosquito composition.

To test our hypothesis, we applied different models that assess whether the response of total abundance and the abundance of vector and non-vector species to forest cover (predictor variable) is linear (GLM with Poisson distribution), non-linear (segmented linear regression model—piecewise) or null. The effects of the predictor variable (forest cover gradient) on the abundance of some species were evaluated through a GLM with a Poisson distribution. Although we detected some degree of overdispersion in the data, the Poisson models were retained because they still provided robust and consistent estimates of ecological trends, and model diagnostics indicated that the general patterns remained reliable. We used segmented regression analysis to identify possible species thresholds along a gradient of loss of native forest cover. The analysis divides explanatory variables into two or more linear regressions, seeking to locate the points where there is a relationship of linear change. The identification of thresholds (breakpoints) is estimated using different starting points and identifying regressions with higher R2 values54. The null model represents the absence of effects. The classification of species as vectors or non-vectors was based on evidence reported in the literature.

To compare the best model for the richness and abundance of each species, we use the corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc) for small sample sizes. We considered models with ΔAICc < 2 as having the strongest empirical support55. The models were generated using specimens identified at the species level, and for all the models, we used the native forest cover (500 m radius) as a predictor variable. Analyses were conducted using the packages “bbmle”56 and “segmented”57. All plots were made with the package “ggplot2”58 in R59.

Results

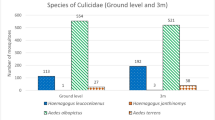

We registered a total of 6910 mosquito specimens, belonging to 12 mosquito genera, representing 33 species. The genus Aedes presented the greatest number of specimens (4,447 mosquitoes), with the occurrence of seven species, followed by Chagasia (636), with a single species, and Anopheles (517), with seven species. The genera Culex (361), Psorophora (311) and Haemagogus (290) were represented by three, four and two species, respectively. Ae. scapularis was the most abundant and frequently captured species in all landscapes (3,637 individuals, representing 52% of the specimens identified), followed by Ae. fulvus (724), Ch. bonneae (636), Cx. sp. (348) and An. triannulatus, with 310 specimens (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1). The species richness decreased with the loss of forest cover along the gradient (Fig. 3). Overall, few specimens were collected in the traps installed in the tree canopy; among them, the most frequent genera were Haemagogus and Sabethes.

We identified 28 species of mosquitoes, with the occurrence of twelve vector species of medical importance in the Neotropical region. Among them, An. darlingi (Malaria), Ae. aegypti (Dengue, Zika, Chikungunya), Cx. quinquefasciatus (Filariose, Oropouche fever), Hg. leucocelaenus (Sylvatic yellow fever), Hg. janthinomys (Sylvatic yellow fever), Ma. titillans (Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis virus), Ae. scapularis (Rocio Encephalitis virus, Dirofilariose, Filariose), Ae. serratus (Oropouche fever, secondary vector of sylvatic yellow fever), Ps. ferox (Rocio virus), Sa. belisarioi (Saint Louis Encephalitis Virus—SLEV) (Table 2), are important species with vector competence in Brazil34,48,66,67,68,104.

The relative air humidity in the landscapes ranged from 47.9 to 73.7% (mean = 64.1 ± 6.4% standard deviation), and the air temperature ranged from 24.0 to 27.9 °C, with a mean of 26.0 ± 0.9 °C standard deviation. The average rainfall was 7.7 mm ± 12.3 mm standard deviation, ranging from 0.0 to 47.6 mm (Supplementary Table S1).

The first axis of the CCA captured 80.0% of the constrained inertia, the second axis captured 15.0%, and the two generated axes explained 95.0%. The CCA ordination clearly revealed a separation between the three groups, with greater associations of species in group 1 (e.g., Ae. fulvus, Sa. glaucodaenon, Hg. leucocelaenus) with respect to the percentage of forest. In addition, the species in group 3 (e.g., Cx. quinquefasciatus, Ae. aegypti, An. evansae) were more related to the temperature and distance from the water body; however, the group of species 2 was not associated with the environmental variables addressed (Fig. 4).

Ordering diagram of the canonical correlation analysis (CCA) of the relationships between the environmental factors (air temperature, % forest cover, and distance of water) and the abundance of mosquitoes. Group 1 (sp3: Ae. fulvus, sp4: Ae. fulvithorax, sp5: Ae. sp, sp6: Ps. albigenu, sp9: Ps. sp, sp10: Hg. leucocelaenus, sp11: Hg. janthinomys, sp14: Ma. sp, sp17: An. benarrochi, sp18: An. triannulatus, sp19: An. rangeli, sp21: An. sp, sp23: Ch. bonnae, sp24: Wy. aporonoma, sp25: Wy. sp, sp28: Cx. (Mel.) sp, sp29: Cq. albicosta, sp32: Sa. belisarioi, sp33: Sa. glaucodaemon); Group 2 (sp1: Ae. serratus, sp8: Ps. ferox, sp15: An. darlingi, sp27: Cx. (Cx.) sp, sp30: Ad. squamipennis); Group 3 (sp2: Ae. scapularis, sp7: Ps. cingulata, sp12: Ma. titillans, sp13: Ma. humeralis, sp16: An. albitarsis, sp20: An. evansae, sp22: Ae. aegypti, sp26: Cx. quinquefasciatus, sp31: Ur. sp.).

The best fit model for total abundance, the abundance of vectors and non-vector species was the generalized linear model. Species abundance was positively related to forest cover. On the other hand, the abundance of vector species was negatively associated with forest cover, and the abundance of non-vector species was positively related to forest cover. The variation in species abundance was strongly explained by the percentage of forest cover (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 2).

Relationships between mosquito abundance—gray color (a), vector species—orange color (b), non-vector especies—blue color (c) and percentage of forest cover at a radius of 500 m, modeled by generalized linear models. The gray shading represents the confidence interval (95%) for the generalized linear model fitted.

The best fit model for a group of species was the piecewise regression model. We detected thresholds for 14 species along the gradient of forest cover. The Ma. titillans change threshold was 81% forest cover. The threshold for Ae. scapularis and Ae. fulvus was 12% of forest cover. The thresholds for Ch. bonneae, Hg. leucocelaenus, Ae. fulvithorax, An. darlingi were between 61 and 62%, and the Ps. albigenu, Hg. janthinomys, An. triannulatus, Wy. aporonoma, Sa. glaucodaemon, we observed a threshold between 48 and 54% native forest cover. For An. albitarsis, a threshold of 30% forest cover was found, and for Cx. quinquefasciatus and Ae. aegypti, the threshold was approximately 12% forest cover. The null model was the best fit for the other species (An. rangeli, An. evansae, Ae. serratus, Ps. cingulate, Ps. ferox, Ma. humeralis) (Fig. 6, Supplementary Table 2).

Relationships between the abundance of each mosquito species and the percentage of native forest cover across landscape gradients on the Bodoquena Plateau, Cerrado hotspot in Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. The dashed red line indicates the threshold of forest cover of the species. The gray shading represents the confidence interval (95%) for the generalized linear model fitted. Letters (a) to (n) are the best fits for the piecewise regression model, and letters (m) to (r) are the best fits for the generalized linear model.

Discussion

We identified a positive effect of forest cover on the total abundance of mosquitoes and the abundance of non-vector species. On the other hand, forest cover negatively influences the abundance of vector species. The threshold values ranged from 12.5 to 81% of the forest cover and presented different values for the 14 species evaluated. When looking at the total abundance, we detected a clear pattern of forest cover by sylvatic species (approximately 60%) and low threshold values (less than 30%) for urban and anthropophilic species, such as Ae. aegypti (approximately 12%). Our results add further evidence that deforestation favors anthropophilic species in tropical regions36 and further demonstrate that species responses are not linear and that forest cover loss of approximately 30–40% already benefits some vector species (such as Ae. scapularis, Ma. titillans and An. darlingi), which has serious implications for public health in rapidly changing landscapes, such as the Cerrado hostpot in Brazil. In deforested and anthropized areas, the loss of natural habitats is compensated by the proliferation of artificial breeding sites, which accumulate rainwater and organic matter (e.g., fish tanks, dams, clay pits, artificial ponds). These microhabitats offer ideal conditions (new habitats for colonization, high temperature, and high nutrient availability) for the reproduction of vector mosquitoes, significantly increasing the risk of outbreaks of vector-borne diseases in ecologically disturbed areas17,33,34,35. Such environmental changes bring mosquitoes closer to humans, making them more efficient at transmitting diseases, increasing the spread of vector-borne diseases, resulting in a growing number of cases, and posing a public health problem3,10,12,15,25,36.

Forest cover is an important predictor of the composition, distribution, and abundance of several species, especially mosquitoes, which are vectors of diseases15,17,60. Mosquitoes have been used as important bioindicators of environmental degradation61, helping to assess the degree of environmental changes in a given area62 in response to changes in the landscape with drastic changes in its density or local extinction of certain species63,64. Studies have shown positive and negative effects of forest cover on the occurrence of key species for public health, such as An. darlingi, Cx. quinquefasciatus, Ae. aegypti, Ae. scapularis9,15. Our results revealed that forest cover affects the abundance of 25 species, revealing a strong relationship between sylvatic vector species in landscapes with high values of forest cover (e.g., Hg. leucocelaenus, Hg. janthinomys, An. darlingi), and species with greater adaptability to urban regions and anthropogenic areas with less native forest cover (e.g., Ae. scapularis, Ae. aegypti, Ma. titillans, Cx. quinquefasciatus). These results show that forest cover is an important driver of the total abundance of mosquitoes. Moreover, the deconstruction of the community data for vector and non-vector species helped us reveal important patterns that are usually masked when all species are pooled65.

We emphasize that the analyses used to relate the percentage of vegetation cover and the occurrence of vector mosquito species have some limitations. The main one is the existence of a species complex in the mosquito samples collected, especially involving Anopheles albitarsis, which has five formally named species and five unnamed ones105. Biological problems in species delimitation were a limiting factor that may have influenced our results.

Although these species have already been reported in forest remnants and riparian forests in Mato Grosso do Sul69, their occurrence throughout the landscapes on the Bodoquena Plateau is relevant from an epidemiological point of view. This region atract people from Brazil and other countries due to its ecotouristic activities, including snorkeling in clear waters, visits to rivers and stremas with clear waters and waterfalls, and cave visits70,71.

In our study, the loss of forest cover favored the emergence of potential vector species (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1). This relationship can also explain the strong link between the loss of culicid species and the increased risk of pathogen transmission in urban landscapes8. Moreover, the urbanization process positively affects the abundance of mosquitoes of medical importance9, and changes in land use and anthropogenic activities are highlighted as potential drivers of the emergence of viruses and arboviruses72,73. The response of some species to forest cover may be related to the biological and ecological characteristics of mosquitoes, such as their preference for blood meals (zoophilic and anthropophilic), the availability of aquatic habitats for oviposition, the presence of animals and humans and microclimate factors36,74.

Most studies on mosquitoes have detected the effects of forest cover on mosquito biodiversity, with an indication of potential impacts on the abundance of vector species and the risk of disease emergence68,75,76. Studies on tropical biodiversity have shown that the loss of forests can cause non-linear responses in different groups, such as mammals, fish, amphibians, and aquatic insects30,31,77,78,79. However, for mosquitoes, evidence of a non-linear response to gradients of native vegetation is still scarce9,80. From this perspective, our study assessed the response of abundance (including total abundance and the abundance of vectors and non-vectors of different species) and detected thresholds for vector and non-vector species. We found that 46% of the species presented thresholds between 61 and 81%, 40% of the species presented thresholds between 54 and 30%, and 13% presented thresholds of approximately 12% forest cover. The vector species presented low to moderate forest cover thresholds, demonstrating their versatility and ability to adapt to altered areas, which has potential implications for the emergence of arboviruses. For example, altered environments can force these species to migrate and, consequently, to change hosts and increase the contact of vectors with humans and domestic animals68,81. With the remodeling of existing ecosystem boundaries, the dynamics between the environment-vector-human triad are altered, leading to the emergence of vector-borne zoonotic diseases3. Additionally, “pathogenic landscapes” serve as early warnings of environments prone to mosquito-borne disease transmission2.

When the percentage of forest cover exceeds the threshold values, some aquatic and terrestrial organisms (e.g., dragonflies) are affected at the same time31. This congruent effect can be extrapolated to several mosquito species that use both environments during their life cycle, especially sylvatic species. On the other hand, the relationship between land use and habitat loss has increased the abundance of arboviral vectors, which occur in landscapes with medium and high degrees of anthropization76. Two urban vector species were rare in this study (Ae. aegypti and Cx. quinquefasciatus), presenting thresholds of approximately 12% forest cover, being more abundant in landscapes with a high degree of human modification, demonstrating their relationship with altered and urban environments. In addition, six vector species were more likely to occur in landscapes with a medium to high degree of human modification, with thresholds ranging from 12 to 60% forest cover. We emphasize that as deforestation increases in the Cerrado hotspot, there is a clear loss of species and an increase in the presence of potential disease vectors for animals and humans.

In general, when the forest cover of mosquito species is less than 48%, it is negatively affected; in contrast, many vector species ultimately benefit from a decrease in native forest cover (e.g., Ae. scapularis, Ma. titillans, An. darlingi, An. albitarsis, Ae. aegypti, Cx. quinquefasciatus). This main result has implications for public health because if a landscape loses more than ~ 50% of its forest cover, it can favor species that transmit diseases. Furthermore, maintaining the integrity of forest ecosystems, especially reducing deforestation, helps (1) maintain biodiversity, (2) maintain the natural balance between wild animals and their own pathogens, (3) decrease contact between vectors and domestic animals and humans, and (3) decrease the transmission of diseases, favoring the maintenance of human health82,83,84.

In summary, we found strong evidence of the influence of forest cover on the abundance of mosquito species in the Cerrado hotspot. The relationships between increased forest cover and the total abundance of species and non-vector species can be clearly observed. On the other hand, vector species were associated with landscapes that presented a loss of forest cover. Information about mosquito distribution, particularly from this poorly studied region, is necessary to contribute to local and national vector surveillance strategies, including possible monitoring and risk assessment programs for the emergence of arboviruses and other diseases transmitted by mosquito vectors in Brazil.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article, supplementary material and available from the corresponding author, A.N.A. No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Foley, J. A. et al. Amazonia revealed: Forest degradation and loss of ecosystem goods and services in the Amazon Basin. Front. Ecol. Environ. 5, 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-929 (2007).

Lambin, E. F., Tran, A., Vanwambeke, S. O., Linard, C. & Soti, V. Pathogenic landscapes: Interactions between land, people, disease vectors, and their animal hosts. Int. J. Health Geogr. 9, 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-9-54 (2010).

Gottwalt, A. Impacts of deforestation on vector-borne disease incidence. JGH 3, 16–19. https://doi.org/10.7916/thejgh.v3i2.4864 (2013).

Chaves, L. F. & Koenraadt, C. J. Climate change and highland malaria: fresh air for a hot debate. Q. Rev. Biol. 85, 27–55 (2010).

Fahrig, L. Effects of habitats fragmentation on biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 34, 487–515 (2003).

Ewers, R. M. & Didham, R. K. Confounding factors in the detection of species responses to habitat fragmentation. Biol. Rev. 81, 117–142 (2006).

Steiger, D. M. et al. Effects of landscape disturbance on mosquito community composition in tropical Australia. J. Vec. Ecol. 37, 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1948-7134.2012.00201.x (2012).

Medeiros-Sousa, A. R., Fernandes, A., Ceretti-Junior, W., Wilke, A. B. B. & Marrelli, M. T. Mosquitoes in urban green spaces: Using an island biogeographic approach to identify drivers of species richness and composition. Sci. Rep. 7, 17826. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18208-x (2017).

Wilke, A. B. B., Medeiros-Sousa, A. R., Ceretti-Junior, W. & Marrelli, M. T. Mosquito populations dynamics associated with climate variations. Acta trop. 166, 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.10.025 (2017).

Gottdenker, N. L., Streicker, D. G., Faust, C. & Carroll, C. R. Anthropogenic land use change and infectious diseases: A review of the evidence. EcoHealth 11, 619–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-014-0941-z (2014).

Ortiz, D. I., Piche-Ovares, M., Romero-Vega, L. M., Wagman, J. & Troyo, A. The impact of deforestation, urbanization, and changing land use patterns on the ecology of mosquito and tick-borne diseases in Central America. Insects https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13010020 (2022).

Roque, F. O. et al. Incorporating biodiversity responses to land use change scenarios for preventing emerging zoonotic diseases in areas of unknown host-pathogen interactions. Front. Vet. Sci. 10, 1229676. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1229676 (2023).

Carvalho, J. A., Teixeira, S. R. F., Carvalho, M. P., Vieira, V. & Alves, F. A. Doenças Emergentes: uma Análise Sobre a Relação do Homem com o seu Ambiente. Rev. Praxis 1, 19–23 (2009).

Colfer, CJP, Sheil, D, Kishi, M. Forests and human health: assessing the evidence. (Center for Internationa Forestry Research, Jakarta 2006).

Chaves, L. S. M. et al. Anthropogenic landscape decreases mosquito biodiversity and drives malaria vector proliferation in the Amazon rainforest. PLoS ONE 16, e0245087. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245087 (2021).

Sánchez-Bayo, F. & Wyckhuys, K. A. G. Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: A review of its drivers. Biol. Conserv. 232, 8–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.01.020 (2019).

Arcos, A. N. et al. Seasonality modulates the direct and indirect influences of forest cover on larval anopheline assemblages in western Amazônia. Sci. Rep. 11, 12721. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92217-9 (2021).

Rivero, S., Almeida, O., Ávila, S. & Oliveira, W. Pecuária e desmatamento: uma análise das principais causas diretas do desmatamento na Amazônia. Nova Economia 19, 41–66 (2009).

Venturieiri, A, Belluzzo, AP, Salim, ACF, Marcuartú, BC, Pinto, JFSKC et al. Dinâmica das queimadas no estado do Mato Grosso entre os anos de 2008 e 2010. https://www.alice.cnptia.embrapa.br/alice/bitstream/doc/962541/1/p1274.pdf (2013).

Domingues, M. S., Bermann, C. & Manfredini, S. A produção de soja no Brasil e sua relação com o desmatamento na Amazônia. RPGeo 1, 32–47 (2014).

Ganem, RS. O crescimento da agropecuária e a busca pela sustentabilidade. Câmara dos Deputados: Políticas setoriais em meio ambiente. http://bd.camara.gov.br/bd/bitstream/handle/bdcamara/21119/politicas_setoriais_ganen.pdf?s (2015).

Stabile, M. C. et al. Solving Brazil’s land use puzzle: Increasing production and slowing Amazon deforestation. Land Use Policy 91, 104362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104362 (2020).

Melz, L. J., Marion Filho, P. J., Bender Filho, R. & Gastardelo, T. A. R. Determinantes da demanda internacional de carne bovina brasileira: Evidências de quebras estruturais. Rev. Eco. Soc. Rural 52, 743–760 (2014).

Soterroni, A. C. et al. Expanding the soy moratorium to Brazil’s Cerrado. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav7336. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aav7336 (2019).

Norris, D. E. Mosquito-borne diseases as a consequence of land use change. EcoHealth 1, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-004-0008-7 (2004).

Wilson, M. C. et al. Habitat fragmentation and biodiversity conservation: Key findings and future challenges. Landsc. Ecol. 31, 219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-015-0312-3 (2016).

Shennan-Farpón, Y., Visconti, P. & Norris, K. Detecting ecological thresholds for biodiversity in tropical forests: Knowledge gaps and future directions. Biotropica 53, 1276–1289. https://doi.org/10.1111/btp.12999 (2021).

Pardini, R., Bueno, A. A., Gardner, T. A., Prado, P. I. & Metzger, J. P. Beyond the fragmentation threshold hypothesis: Regime shifts in biodiversity across fragmented landscapes. PLoS ONE 5, e13666 (2010).

Banks-Leite, C. et al. 2014. Using ecological thresholds to evaluate the costs and benefits of set-asides in a biodiversity hotspot. Science 345, 1041–1045 (2014).

Ochoa-Quintero, J. M., Gardner, T. A., Rosa, I., Ferraz, S. F. B. & Sutherland, W. J. Thresholds of species loss in Amazonian deforestation frontier landscapes. Conserv. Biol. 29, 440–451. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12446 (2015).

Rodrigues, M. E. et al. Nonlinear responses in damselfly community along a gradient of habitat loss in a savanna landscape. Biol. Conserv. 194, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.12.001 (2016).

Githeko, A. K., Lindsay, S. W., Confalonieri, U. E. & Patz, J. A. Climate change and vector-borne diseases: A regional analysis. Bull. World Health Organ. 78, 1136–1147 (2000).

Tadei, W. P. Biologia de anofelinos amazônicos. X Ocorrência de espécies de Anopheles nas áreas de influência das hidrelétricas de Tucuruí (Pará e Balbina (Amazonas). Rev. Bras. Eng. 1, 71–78 (1986).

Arcos, A. N., Ferreira, F. A. S., Cunha, H. B. & Tadei, W. P. Characterization of artificial larval habitats of Anopheles darlingi (Diptera: Culicidae) in the Brazilian Central Amazon. Rev. Bras. Entomol. 62, 267–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbe.2018.07.006 (2018).

Arcos, A. N., Silva Ferreira, F. A., Tadei, W. P., Cunha, H. B. & Roque, R. A. Limnological variables associated with the presence of Anopheles Meigen, 1818 (Diptera: Culicidae) larvae in breeding sites in Amazonas. Brazil. Rev. Chil. Entomol. 49, 871–885 (2023).

Burkett-Cadena, N. D. & Vittor, A. Y. Deforestation and vector-borne disease: forest conversion favors important mosquito vectors of human pathogens. Basic Appl. Ecol. 26, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2017.09.012 (2018).

Boggiani, PC. Geologia da Bodoquena: Por que Bonito é bonito? In Nos jardins submersos da Bodoquena: um guia de identificação de plantas aquáticas de Bonito e região (eds. Scremin-Dias, E, Pott, JÁ, Hora, RC, Souza, PR.) 10–23 (Editora UFMS, 1999).

ICMBio. Instituto Chico Mendes De Conservação Da Biodiversidade. Plano de Manejo do Parque Nacional da Serra da Bodoquena. http://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/docs-planos-de-manejo/Encarte1_2013.pdf (2013).

Klink, C. A. & Machado, R. B. Conservation of the Brazilian Cerrado. Conserv. Biol. 19, 707–713 (2005).

ZEE-MS. Zoneamento ecológico-econômico do estado de Mato Grosso do Sul. https://www.semagro.ms.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Consolida%C3%A7%C3%A3o-ZEE-1%C2%AA-Aproxima%C3%A7%C3%A3o.pdf (2009).

Brasil. Áreas prioritárias para conservação, uso sustentável e repartição dos benefícios da biodiversidade. Ministério do Meio ambiente. World Wide Web publication. 2016. http://www.mma.gov.br/images/arquivo/80049/Areas%20Prioritarias/Cerrado%20e%20Pantanal/FICHAS%20Areas%20Prioritarias%20Cerrado%20e%20Pantanal_2%20atualizacao%2022ago16.pdf (2016).

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R., Mittermeier, C., Fonseca, G. A. B. & Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858. https://doi.org/10.1038/35002501 (2000).

Rausch, L. L. et al. Soy expansion in Brazil’s Cerrado. Conserv. Lett. 12, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12671 (2019).

Strassburg, B. B. N. et al. Moment of truth for the Cerrado hotspot. Nat. Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0099 (2017).

Kottek, M., Grieser, J., Beck, C., Rudolf, B. & Rubel, F. World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Z. 15, 259–263 (2006).

Baptista-Maria, V. R., Rodrigues, R. R., Damasceno Junior, G., Maria, F. D. S. & Souza, V. C. Composição florística de florestas estacionais ribeirinhas no estado de Mato Grosso do Sul. Brasil. Acta Bot. Bras. 23, 535–548 (2009).

Consoli, RAGB, Lourenço-de-Oliveira, R. Principais Mosquitos de Importância Sanitária no Brasil (Fiocruz, 1994).

Forattini, OP. Culicidologia Médica. 2nd. (Edusp 2002).

Forattini, O. P., Gomes, A. D. C., Santos, J. L. F., Kakitani, I. & Marucci, D. Freqüência ao ambiente humano e dispersão de mosquitos Culicidae em área adjacente à mata atlântica primitiva da planície. Rev. Saúde Pública 24, 101–107 (1990).

Service, M. W. Mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) dispersal—the long and short of it. J. Med. Entomol. 34, 579–588 (1997).

ESA. European Space Agency. Sentinel-2 https://sentinels.copernicus.eu/documents/247904/1848117/Sentinel-2_Data_Products_and_Access (2015).

INMET. National Institute of Meteorology. Meteorological Database for Teaching and Research. http://www.inmet.gov.br/portal/index.php?r=bdmep/bdmep (2021).

Oksanen, J, Kindt, R, Legendre, P, O’hara, RB, Stevens, MHH. Vegan: Community Ecology Package: R package. http://r-forger-projectorg/projects/vegan (2011).

Muggeo, V. M. R. Estimating regression models with unknown break-points. Stat. Med. 22, 3055–3071. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1545 (2003).

Burnham, KP, Anderson, DR. Model selection and multimodel inference. A pratical information-theoritical approach (Springer, 2002).

Bolker, B. bbmle. Tools for general maximum likelihood estimation. – R package ver. 1.0.18 (2016).

Muggeo, V. M. Segmented: An R package to fit regression models with broken-line relationships. R News 8, 20–25 (2008).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag, New York https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (2016).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria https://www.R-project.org/ (2020).

Moyes, C. L. et al. Predicting the geographical distributions of the macaque hosts and mosquito vectors of Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in forested and non-forested areas. Parasit Vectors 9, 242. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1527-0 (2016).

Dorvillé, L. F. M. Mosquitoes as bioindicators of forest degradation in southeastern Brazil, a statistical evaluation of published data in the literature. Stud. Neotrop. Fauna Environ. 31, 68–78 (1996).

Alencar, J. et al. Ecosystem diversity of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in a remnant of Atlantic Forest, Rio de Janeiro state. Brazil. Aust. Entomol. 60, 244–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/aen.12508 (2021).

Medeiros-Sousa, A. R. et al. Diversity and abundance of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in an urban park: Larval habitats and temporal variation. Acta Trop. 150, 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.08.002 (2015).

Chaves, L. S. M., Sá, I. L. R., Bergamaschi, D. P. & Sallum, M. A. M. Kerteszia Theobald (Diptera: Culicidae) mosquitoes and bromeliads: A landscape ecology approach regarding two species in the Atlantic rainforest. Acta Trop. 164, 303–313 (2016).

Marquet, PA, Fernandez, M, Navarrete, SA, Valdovinos, C. Diversity emerging: toward a deconstruction of biodiversity patterns. In Frontiers of Biogeography: New Directions in the Geography of Nature (eds. Lomolino, M. Heaney, LR) 191–209 (Cambridge University Press, 2004)

Cardoso, J. C. et al. Novos registros e potencial epidemiológico de algumas espécies de mosquitos (Diptera, Culicidae), no estado do Rio Grande do Sul. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 43, 552–556 (2010).

Leal-Santos, F. A. et al. Species composition and fauna distribution of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) and its importance for vector-borne diseases in a rural area of Central Western-Mato Grosso, Brazil. EntomoBrasilis 10, 94–105. https://doi.org/10.12741/ebrasilis.v10i2.687 (2017).

Tadei, W. P. et al. Adaptative processes, control measures, genetic background, and resilience of malaria vectors and environmental changes in the Amazon region. Hydrobiol. 789, 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-016-2960-y (2017).

Almeida, P. S. et al. Vector aspects in risk areas for sylvatic yellow fever in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul. Brazil. Rev. Patol. Trop. 45, 398–411 (2016).

Boggiani, P. C., Trevelin, A. C., Sallun Filho, W., Oliveira, E. C. D. & Almeida, L. H. S. Turismo e conservação de tufas ativas da Serra da Bodoquena, Mato Grosso do Sul. Tourism and Karst Areas 4, 55–63 (2011).

Klein, F. M. et al. Educação ambiental e o ecoturismo na Serra da Bodoquena em Mato Grosso do Sul. Sociedade & Natureza 23, 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1982-45132011000200013 (2011).

Jones, K. E. et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451, 990–993. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06536 (2008).

Donalisio, M. R., Freitas, A. R. R. & Zuben, A. P. B. V. Arboviruses emerging in Brazil: Challenges for clinic and implications for public health. Rev Saúde Pública https://doi.org/10.1590/s1518-8787.2017051006889 (2017).

Barros, F. S., Honório, N. A. & Arruda, M. E. Mosquito anthropophily: implications on malaria transmission in the Northern Brazilian Amazon. Neotrop. Entomol. 39, 1039–1043. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1519-566X2010000600029 (2010).

Ferraguti, M. et al. Effects of landscape anthropization on mosquito community composition and abundance. Sci. Rep. 6, 29002. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29002 (2016).

Vieira, C. J. S. P. et al. Land use effects on mosquito biodiversity and potential arbovirus emergence in the Southern Amazon Brazil. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 69, 1770–1781. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.14154 (2021).

Dala-Corte, R. B. et al. Thresholds of freshwater biodiversity in response to riparian vegetation loss in the Neotropical region. J. Appl. Ecol. 57, 1391–1402. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13657 (2020).

Verga, E. G., Huais, P. Y. & Herrero, M. L. Population responses of pest birds across a forest cover gradient in the Chaco ecosystem. For. Ecol. Manage. 491, 119174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119174 (2021).

Valente-Neto, F. et al. Incorporating costs, thresholds and spatial extents for selecting stream bioindicators in an ecotone between two Brazilian biodiversity hotspots. Ecol. Indic. 127, 107761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107761 (2021).

Câmara, D. C. P., Silva Pinel, C., Rocha, G. P., Codeço, C. T. & Honório, N. A. Diversity of mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) vectors in a heterogeneous landscape endemic for arboviruses. Acta Trop. 212, 105715 (2020).

Vinod, S. Deforestation and water pollution impact on mosquitoes related epidemic diseases in nanded region. Biosci. Discov. 2, 309–316 (2011).

Keusch, GT, Pappaioanou, M, Gonzalez, MC, Scott, KA, Tsai, P. Sustaining Global Surveillance and Response to Emerging Zoonotic Diseases. (National Academies Press, 2009).

Watson, J. E. M. et al. The exceptional value of intact forest ecosystems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 599–610. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0490-x (2018).

Ellwanger, J. H. et al. Beyond diversity loss and climate change: Impacts of Amazon deforestation on infectious diseases and public health. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 92, e20191375. https://doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765202020191375 (2020).

Reinert, J. F. List of abbreviations for currently valid generic-level taxa in family Culicidae (Diptera). European Bulletin 27, 68–76 (2009).

Harbach, RE. Mosquito Taxonomic Inventory. Available from: http://mosquitotaxonomic-inventory.info/ (accessed 15.06.25). (2025).

Wilkerson, R. C. et al. Making mosquito taxonomy useful: A stable classification of tribe aedini that balances utility with current knowledge of evolutionary relationships. PLoS ONE 10, e0133602. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133602 (2015).

Klein, T. A., Lima, J. B. & Tada, M. S. Comparative susceptibility of anopheline mosquitoes to Plasmodium falciparum in Rondonia Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 44, 598–603. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.1991.44.598 (1991).

Póvoa, M. M. et al. The importance of Anopheles albitarsis E and An. darlingi in human malaria transmission in Boa Vista, state of Roraima Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 101, 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0074-02762006000200008 (2006).

Gonçalves, C. M. et al. Variação distinta na competência vetorial entre nove populações de campo de Aedes aegypti em uma cidade brasileira com risco de dengue endêmica. Parasit. Vectors 7, 1–8 (2014).

Garcia-Luna, S. M., Weger-Lucarelli, J., Rückert, C. & Murrieta, R. A. Variation in competence for ZIKV transmission by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in Mexico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2, e0006599. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006599 (2018).

Cevallos, V. et al. Zika and Chikungunya virus detection in naturally infected Aedes aegypti in Ecuador. Acta Trop. 177, 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.09.029 (2018).

Mitchell, C. J., Forattini, O. P. & Miller, B. R. Experimentos de competência vetorial com vírus Rocio e três espécies de mosquitos da zona epidêmica do Brasil. Rev. Saúde Pública. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89101986000300001 (1986).

Macêdo, F. C., Labarthe, N. & Lourenço-de-Oliveira, R. Susceptibility of Aedes scapularis (Rondani, 1848) to Dirofilaria immitis (Leidy, 1856), an Emerging Zoonosis. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz https://doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761998000400003 (1998).

de Pinheiro, F. et al. Epidemia do vírus Oropouche em Belém. Revi. Ser. Esp. Saúde Públ. 12, 15–23 (1962).

Cardoso, J. C. et al. Yellow fever virus in Haemagogus leucocelaenus and Aedes serratus mosquitoes, southern Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 16, 1918–1924. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1612.100608 (2010).

Subramanian, S. et al. The relationship between microfilarial load in the human host and uptake and development of Wuchereria bancrofti microfilariae by Culex quinquefasciatus: A study under natural conditions. Parasitology 116, 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182097002254 (1998).

Feitoza, L. H. M. et al. Integrated surveillance for Oropouche Virus: Molecular evidence of potential urban vectors during an outbreak in the Brazilian Amazon. Acta Trop. 261, 107487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2024.107487 (2025).

Cardoso, B. F. et al. Detecção do segmento S do vírus Oropouche em pacientes e em Culex quinquefasciatus no estado de Mato Grosso Brasil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 110, 745–754. https://doi.org/10.1590/0074-02760150123 (2015).

Abreu, F. V. S. et al. Haemagogus leucocelaenus and Haemagogus janthinomys are the primary vectors in the major yellow fever outbreak in Brazil, 2016–2018. Emerg Microbes Infect. 8, 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2019.1568180 (2019).

Turell, M. J. et al. Vector competence of peruvian mosquitoes (Diptera Culicidae) for epizootic and enzootic strains of venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis virus. J. Med. Èntomol. 37, 835–839. https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-37.6.835 (2000).

De Sousa, F. B. et al. Report of natural Mayaro virus infection in Mansonia humeralis (Dyar & Knab, Diptera: Culicidae). Parasit Vectors https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-023-05707-2 (2023).

Mitchell, C. J., Forattini, O. P. & Miller, B. R. Experimentos de competência vetorial com vírus Rocio e três espécies de mosquitos da zona epidêmica do Brasil. Rev. Saúde Pública https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89101986000300001 (1986).

Causey, O. R., Shope, R. E. & Theiler, M. Isolation of St Louis encephalitis virus from arthropods in Pará, Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. Baltim 13, 449 (1964).

Bourke, B. P. et al. Phylogenetic analysis of the Neotropical Albitarsis Complex based on mitogenome data. Parasites Vectors 14, 589. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-05090-w (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank the technicians of the Malaria and Dengue Laboratory of the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia—INPA, and Fundação Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul—UFMS/MEC—Brazil, for their support in collection and analysis. We also thank Gervilane Lima for the identification of specimens.

Funding

This work was supported by fellowships from Fundacão de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento do Ensino, Ciência e Tecnologia do Estado de Mato Grosso do Sul (FUNDECT) and from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—“Finance Code 001”. This study was financed in part by the Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul- Brasil (UFMS)—Finance Code 001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N.A.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. P.T.S.: Assisted in data analysis, Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing. F.A.S.F.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—review and editing. F.V.N.: Assisted in data analysis, Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing. W.P.T.: Conceptualization, Supervision. F.O.R.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wanderli Pedro Tadei: In memoriam.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arcos, A.N., Soares, P.T., da Silva Ferreira, F.A. et al. Responses of vector and non-vector mosquito communities to a gradient of native forest cover loss in the Cerrado hotspot, Brazil. Sci Rep 15, 44523 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28034-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28034-1