Abstract

Accurately predicting the State of Health (SoH) of Lithium-ion Batteries (LIBs) is critical for improving Electric Vehicle (EV) performance and enabling smarter charging strategies, yet existing methods often struggle with variable cycle data and the limitations of physical models in capturing the complex behaviour of LIBs. To overcome these challenges, the present work introduces a hybrid deep learning framework, the Optuna-Optimised Convolutional Neural Network and Stacked Long Short-Term Memory (OptiCNN-SLSTM) model, which combines a 1D CNN for temporal feature compression with a stateful LSTM to capture both inter- and intra-sample dependencies. A two-step hyperparameter optimisation process is applied, first exploring different parameter sets and then refining them through Optuna optimisation. The model was trained and tested on the NASA and Oxford datasets and validated on a real-world EV E-kart battery dataset, achieving strong accuracy with RMSE values of 2.15% (B0005) and 2.18% (B0007) on NASA, 0.67% (cell-1) and 1.02% (cell-2) on Oxford, and exceptionally low errors on the E-kart dataset (MSE = 0.001%, RMSE = 0.03%, MAE = 0.28%), demonstrating its robustness and generalisability for practical EV battery health estimation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

LIBs are essential to EVs, though they undergo inevitable ageing and performance degradation over time, raising significant safety concerns1. Assessing the SoH, the ratio of current to nominal maximum capacity is crucial for ensuring safe operation2. However, SoH estimation is complicated by factors such as charge/discharge rates, temperature, and operating conditions, making direct measurement infeasible3. In Equation (1), the SoH is defined as the ratio of the battery’s measured capacity at a specific cycle, \(C_n\), to its nominal (initial) capacity at the beginning of life, \(C_0\):

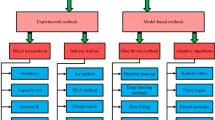

SoH is a key metric used to quantify the overall condition of a battery relative to its nominal performance. It reflects the battery’s ability to store and deliver energy compared to when it was new. SoH is typically expressed as a percentage, where 100% indicates a fully healthy battery and lower values indicate ageing or degradation. Factors affecting SoH include cycle count, depth of discharge, temperature, and charging-discharging rates. Accurate SoH estimation is crucial for BMS to ensure safe operation, optimise performance, and predict RUL. SoH estimation techniques are generally classified into model-based and data-driven approaches. Model-based methods offer simplicity and low computational cost but have limited accuracy over extended use and under complex conditions34. On the other hand, data-driven approaches can effectively handle large-scale operational data and nonlinear dynamics, showing superior accuracy and generalisation over time5.

Recently, Machine Learning and Deep Learning models, including Support Vector Machines (SVM), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)6, and stacked Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks7, have gained traction for SoH estimation. As deep learning models become more sophisticated and widely used in predictive systems, their increasing complexity often hides how decisions are made. This lack of transparency has fueled a growing need for interpretable and explainable frameworks. Explainable AI (XAI) has emerged to meet this need, striving to combine strong predictive performance with clear, understandable reasoning.

The primary objective of this study is to develop a robust hybrid deep learning model for accurate SoH prediction in LIBs, addressing the challenges of variable cycle data and complex degradation dynamics.

This work proposes a hybrid Optuna + CNN + stacked LSTM architecture named OptiCNN-SLSTM, which efficiently processes time-series battery data. The model independently handles charging and discharging profiles using 1D CNN blocks and stacked LSTM layers. Data balancing and subsampling strategies help retain critical information while ensuring a lightweight structure. Hyperparameter optimisation is performed using Optuna Optimisation for computational efficiency. We evaluate OptiCNN-SLSTM on the NASA battery dataset (B0005 and B0007), Oxford and real-time from E-kart at TIET, using MAE, MSE, RMSE, and MAPE as performance metrics and a real-time TIET E-kart dataset.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows: Section II reviews related literature; Section III describes the proposed method; Section IV presents the experimental setup and results; and Section V concludes the study.

Literature

Researchers have worked on various SoH estimation techniques. For example, Xu et al.8 proposed a technique for evaluating the SoH of a particular EV by employing discrete incremental capacity analysis. Furthermore, the utilisation of a Bidirectional LSTM (Bi-LSTM) network for online capacity estimation in LIBs has gained attention. Similarly, Ning et al.9 provide a novel approach for estimating the SoH of LIBs by combining an arctangent function adaptive genetic algorithm with a back propagation neural network (ATAGA-BP). The process of error point optimisation and correlation verification is also conducted. The simulation results utilising NASA data demonstrate a correlation of over 85% between the suggested health indicator and LIBs capacity. Moving ahead, Yongzhi et al.10 proposed a hybrid of LSTM and Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) to effectively capture the inherent long-term dependencies among the deteriorated capacities. The developed RUL predictor has been focused on the capacity explicitly, thereby showcasing the efficacy of the Auto-CNN-LSTM model in improving its long-term learning capabilities. However, the works mentioned above are yet to work on the sampling techniques. Sampling is crucial to derive precise inferences on the holistic condition of batteries within a broader cohort. Therefore, to overcome this, Yan Ma et al.11 have proposed a combination of deep belief networks (DBNs) and LSTM, along with transfer learning, for the estimation of SoH in LIBs. Joint distribution adaptation (JDA) has been used to fuse the health indicators, which are subsequently fed into a hybrid DBN-LSTM network for SoH estimation. The experiments have been conducted, and the findings showed improved results in terms of estimation accuracy. In a similar vein, Xu et al.12 employed the LSTM RNN model, using cycle sequences of capacities within discharge voltage windows as input data. The authors compared the performance of their model to other prediction methods, such as particle filter and support vector regression, and found that the LSTM RNN model outperformed them. Additionally, a framework known as the digital twin, encompassing a real-time SoH estimation method featuring a time-attention SoH estimation model and a future data reconstruction strategy, has been developed by Qin et al.13. The presented approach aimed to achieve accurate SoH estimation by having smaller samples compared to existing approaches. Sharma et al.14 highlight that battery SoH estimation is challenging due to nonlinear ageing and variable operating conditions. Their study employs a stacking framework combining LR, RF, and XGBoost, enhanced by CPDE preprocessing and GridSearchCV tuning. Experiments on real-world and NASA datasets demonstrate improved accuracy over conventional methods, supporting smarter battery management and extended battery lifespan. Kamboj et al.15 emphasise the importance of accurate RUL prediction for reliable battery management and propose the Opt-KAN-XAI model, which integrates Optuna-tuned KAN with SHAP-based explainability. Their approach effectively captures complex ageing patterns, identifies temperature as a key influencing factor, and demonstrates superior accuracy and robustness on NASA and CALCE datasets compared to existing methods. Similarly, Lie et al.16 developed an improved CNN and LSTM model called Auto-CNN-LSTM for the prediction of the RUL of LIBs. The augmentation of data dimension has been done using autoencoders required for the training of CNN and LSTM models. Moreover, a filter has been used that smooths the value predicted by the proposed Auto-CNN-LSTM model. The experiments have been conducted, and the findings illustrate the effective performance of Auto-CNN-LSTM. Houde et al.17 presented a Markov chain and Prior Knowledge-based Neural Network (PKNN) method for the estimation of SoH. Multiple features have been extracted to capture the ageing process of the battery. The experiment is conducted and compared with the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. The findings showed that the work performed well by reducing the loss by 1.7% as compared to the existing method. Moving ahead, Yajun et al.18 introduced a new approach that integrates a voltage-capacity (VC) model-based incremental capacity analysis (ICA) with support vector regression (SVR) to estimate the SoH of batteries. To ensure accurate and efficient acquisition of incremental capacity (IC) curves, an evaluation is conducted on a total of 18 voltage-current (VC) models. After conducting an association analysis between the retrieved health variables and the reference battery capacity, the decision is made to employ the SVR algorithm for the development of models aimed at SoH prediction. The experimental findings demonstrate that the SVR models exhibit a notable level of accuracy when employed for SoH estimation. Moreover, Wang et al.19 devised a transferable data-driven framework to effectively estimate the capacity of LIBs in real-world scenarios, specifically focusing on batteries with the same chemistry but varying capacities. The suggested methodology takes universal data obtained from a laboratory dataset and employs a pre-existing network specifically tailored for small-capacity batteries that undergo constant-current discharge patterns. The findings indicate that the suggested approach substantially improves both resilience and accuracy. Nevertheless, efforts in this domain have been predominantly focused on CNN, LSTM, and RNN models, with minimal exploration of hybrid deep learning architectures. Furthermore, the requisite dataset preprocessing step, specifically sampling, has been overlooked in previous research endeavours8,9,10. Accurate SoH estimation is vital for repurposing electric vehicle batteries. Recent literature shows a strong shift toward machine learning methods, with deep learning especially LSTM networks being the most widely used. Public datasets, notably from NASA, are increasingly utilised, enabling reproducible research. New trends include transfer learning and hybrid models, aimed at improving accuracy. SoH prediction is also gaining relevance in smart energy systems like IoT and smart grids for better energy management11. In addition, the application of optimisation techniques for refining model parameters remains an unaddressed aspect.

In light of these limitations, this research has addressed the aforementioned gaps by proposing OptiCNN-SLSTM, an optuna-optimised hybrid CNN and stacked LSTM for SoH estimation. Table 1 presents a critical analysis of related work along with a comparative evaluation against the proposed OptiCNN-SLSTM.

Specifically, the proposed OptiCNN–SLSTM model demonstrates strong potential for real-time battery health monitoring in electric vehicles (EVs) and predictive maintenance of energy storage systems (ESS). In EVs, its lightweight and computationally efficient architecture enables accurate on-board State of Health (SoH) estimation, supporting predictive maintenance, optimal charging strategies, and enhanced driving range prediction to improve reliability and operational safety. In ESS applications, the model enables health-aware scheduling, lifecycle forecasting, and load management, thereby ensuring a prolonged system lifespan and a stable energy supply under varying operating conditions. These applications underscore the practical relevance and industrial scalability of the proposed framework in advancing intelligent battery management and sustainable energy systems.

Contributions

The key contributions of this work are summarised as follows:

i. Proposed a hybrid, lightweight, and computationally efficient deep learning architecture that combines a 1D CNN for temporal compression with a stacked LSTM for capturing intra- and inter-cycle dependencies, enabling accurate SoH prediction.

ii. Introduced an optimized sub-sampling strategy that leverages complete charging–discharging cycles while performing cycle-based segmentation to preserve critical degradation patterns and reduce computational overhead from long time-series inputs.

iii. Developed an OptiCNN–SLSTM framework with stateful LSTM integration, enabling phase continuity and improving temporal learning efficiency for practical real-time deployment.

iv. Implemented a two-phase training mechanism that independently learns phase-specific dynamics from charging and discharge data, improving generalization and predictive robustness under varying operational conditions.

Proposed framework

In this research, Optuna optimised a hybrid architecture combining a 1D CNN and stacked LSTM for the estimation of SoH in Li-ion batteries. The research utilises an open-source dataset provided by NASA, Oxford, and the real-time TIET Ekart dataset. Before model training, extensive data pre-processing has been carried out to prepare, refine, and balance the dataset effectively. The pre-processed data is subsequently fed into the hybrid architecture, consisting of a CNN and stacked LSTM layers. The key architectural parameters, including the number of cycles per sub-sample and CNN kernel size, have been optimised through the optuna optimisation technique. To assess the performance of the proposed methodology, four fundamental evaluation metrics have been employed: MSE, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE. Figure 1 presents the workflow of the proposed framework of OptiCNN-SLSTM, elaborated in the following section.

Dataset description

In this research, the dataset made available by NASA has been harnessed for analysis. This dataset comprises .mat files, each corresponding to a multitude of LIBs. Every individual battery encompasses two distinct profiles: charging and discharging. These profiles have been characterised by specific features. It is noteworthy that the cycle number, while implicit, has not been explicitly delineated within the dataset. There is an interval of 1 cycle between any 2 consecutive cycles’ data in the NASA dataset, and each battery has around 167 cycles. Additionally, the dataset includes information pertaining to the maximum battery capacity achieved at the conclusion of each cycle.

Dateset 1. Two NASA lithium-ion batteries (B0005 and B0007) were tested under distinct operational profiles involving both charging and discharging at ambient temperature. Charging was performed in constant-current (CC) mode at 1.5 A until the cell voltage reached 4.2 V, followed by constant-voltage (CV) charging until the current dropped to 20 mA. Discharging was carried out in CC mode at 2 A, terminating when the voltage fell to 2.7 V for Battery 0005 and 2.5 V for Battery 0007. Testing continued until each cell reached its end-of-life criterion, defined as a 30% reduction in rated capacity (from 2 Ah to 1.4 Ah).

Dateset 2. The Oxford Lithium-ion Battery dataset contains long-term cycling data from commercial Li-ion cells tested under controlled laboratory conditions. It includes high-resolution measurements of voltage, current, and temperature during repeated charge–discharge cycles, enabling analysis of degradation patterns and SOH estimation prediction. The dataset is widely used for benchmarking battery prognostics and health management algorithms.

Dateset 3. The TIET E-Kart dataset was collected from an in-house electric kart equipped with a 2500 W motor capable of delivering peak currents up to 100 A. The motor and vehicle dynamics produce diverse discharge patterns representing acceleration, braking, idling, and stop-and-go driving. An on-board BMS logs high-resolution time-series data, including pack and cell voltages, current, temperatures, and state-of-charge, providing a rich resource for online SoH modelling. However, the BMS also introduces challenges: measurement noise, sensor drift, and occasional data gaps can affect the reliability of recorded signals. Additionally, high current transients and thermal effects during aggressive driving may complicate accurate SoH estimation. Despite these challenges, the dataset offers a controlled yet realistic environment, balancing reproducibility and operational variability, making it well-suited for developing and validating real-time SoH prediction models. Table 2 summarises the lithium battery chemistries used in the dataset.

Data pre-processing and balancing

Data pre-processing involves three stages comprising data preparation, refinement, and balancing, which are as follows:

a. Data Preparation: Two batteries comprising B0005 and B0007 have been utilised in the current study. Within each .mat file corresponding to a battery, cycles are arranged in chronological order. Each of the two battery states, namely charging and discharging, corresponds to a single cycle. However, these states are not inherently synchronised by a cycle number. Consequently, it is imperative to establish a consistent cycle ordering to facilitate further data processing. To achieve this, an additional feature denoting the cycle number for each cycle has been introduced. For each cycle, data from both battery states were carefully extracted and stored, with charging data saved in one file and discharging data in another. To ensure synchronisation across all files and preserve the chronological relationships inherent in the battery states, the cycle number feature has been uniformly incorporated into each file.

b. Data Refinement: A random anomaly occurred during the data extraction phase. For some of the cycles, the discharging data state was not presented in the correct order, or there was more than one discharging cycle after one charging cycle. Therefore, the discharging data that was closest to the previous cycle’s data has been retained from the two discharging cycles.

c. Data Balancing: This pre-processing step involves harmonising data entries (timestamps) across all cycles before their input into the model. It should be noted that the original length of each cycle varies, with the initial cycle encompassing the greatest number of time stamps and the concluding cycle featuring the fewest. This discrepancy arises from the inherent nature of battery ageing, wherein the total capacity diminishes over time, leading to a progressive reduction in cycle duration.

Consequently, it is essential to equalise the time stamps across all cycles to enable the model to accurately capture their influence on battery performance. To achieve this, an averaging technique is applied to homogenise cycle lengths. First, the maximum and minimum lengths among all cycles are determined, and a fixed reference cycle length, less than or equal to the minimum, is selected. Each cycle is then subdivided into continuous intervals based on this fixed length, and within each interval, all rows (time stamps) are averaged column-wise, producing a single representative row. This approach standardises variable-length cycles into a uniform format, facilitating consistent model input.

To further enhance model performance, all input features are normalised to a common scale, reducing bias from differing units or magnitudes and improving convergence during training. Furthermore, two features, ’Time’ and ’cycle number’, preserve the uniqueness of each cycle. The ‘Time’ feature within a cycle remains independent of other cycles, with its maximum value helping maintain uniqueness, while ‘Cycle Number’ explicitly indicates the chronological position of each record in the battery’s life. Together, these techniques ensure that the model can accurately track the battery’s ageing state at any given moment.

For each cycle i with original length \(L_i\), the standardized length \(L_{\text {fixed}}\) is determined as:

The averaging operation for each interval j:

Where k = number of timestamps in interval j, \(X_{i,j}\) = feature value at timestamp i in interval j and \(\bar{X}_j\) = averaged feature value for interval j.

These include SoH capacity, which indicates the current health relative to nominal capacity; initial SoH, providing a baseline for tracking capacity fade; and charge capacity (QC), reflecting the battery’s ability to store energy during charging, which decreases with ageing and repeated cycles. Additionally, voltage captures the electrochemical state and internal resistance, current represents load conditions and discharge-charge rates affecting stress and ageing, and temperature influences chemical reactions, with high or fluctuating temperatures accelerating degradation. By integrating these features, the model effectively captures both short-term operational dynamics and long-term degradation trends.

Model development

A hybrid deep learning model architecture comprising CNN and stacked LSTM has been built for predicting the SoH after each cycle. The underlying challenges of time-series preprocessing and random data size of battery cycles have been efficiently resolved by the proposed OptiCNN-SLSTM. Firstly, appropriately sized input sub-samples have been created for a single battery, which can be fed into the model. Additionally, input sub-samples have been compressed using temporal compression with a 1D CNN. The compressed sub-samples are then fed into a 3-layer stacked LSTM architecture for estimating battery capacity. Finally, the hyperparameters of the proposed hybrid model are tuned. A detailed description of the approach used in model development is as follows:

Sub-sampling

Although the duration of each cycle has been standardised, the dataset from an individual battery still comprises an extensive number of timestamp entries. Processing the entire dataset in a single iteration is infeasible for the model. Therefore, the dataset is partitioned into smaller sub-samples. Sub-sampling serves to input a decreased count of timestamp entries to the model in each iteration. Sub-sampling is a form of mini-batch learning where the batch size equals 1, but at the same time, there is no shuffling between the chronological order of batches/sub-samples. In each sub-sample, data from only a specified number of cycles (n), is assembled. Adjacent cycles are selected as part of a sub-sample, which helps maintain continuity within it. For any 2 adjacent sub-samples, n−1 cycles are overlapping, i.e., there is a jump of 1 cycle from a sub-sample to its succeeding sub-sample. This helps in leveraging data from the latest n cycles before estimating SoH at the end of a cycle.

For a battery with N total cycles, sub-samples are created as:

Where \(S_i\) = i-th sub-sample, \(C_j\) = j-th cycle data, n = number of cycles per sub-sample (optimised to \(n=3\)), and Sliding window: \(S_{i+1} = \{C_{i+1}, C_{i+2}, \ldots , C_{i+n}\}\).

Model architecture

This research utilises both charging data and discharging data for model development. The hybrid model is developed using a 1D-CNN for sub-sample compression and a stacked LSTM having three layers for estimating the battery capacity. The developed model is divided into two phases: the first phase represents the training of the model on charging data, and the second phase utilises the same model for discharging data, incorporating the output of the first phase. Two identical architectures (phases) have been utilised so as to aid the final model in distinguishing between charging data and discharging data. Each architecture has its own weights corresponding to its data profile. At the same time, fusing the 2 architectures together, sequentially, helps utilise data from both profiles, while maintaining the chronological order of data. If it were a single CNN+LSTM network, the combined length of timestamps from the 2 battery profiles would make it difficult for a single LSTM network to do temporal mapping optimally and would also increase the training time. The final concluding dense layer gives the battery capacity at the end of each cycle based on charging and discharging data. The working of the developed hybrid model has a 1-D CNN and stacked LSTM having three layers. Both these networks are arranged in sequential order, with the CNN layer preceding the LSTM layer and are discussed in the following subsections.

Temporal compression using 1D CNN

1D CNN has been used in the proposed architecture for temporal compression of sub-samples. When a sub-sample (charging/discharging) is fed through the model, it first passes through the CNN layer. It is worth noting that CNN used in the architecture only compresses the data within a cycle, while the number of original cycles remains uncompressed. It has been applied independently to each feature in the sub-sample. All the features are processed through a separate CNN kernel. The amount of temporal compression is kept the same for all the features to maintain homogeneity. The role of CNN in the proposed model is of critical importance. The inclusion of a 1-D CNN layer enables a lightweight overall architecture by efficiently extracting salient features from raw input data. Without the CNN, the LSTM network would be overwhelmed by the large influx of raw input data. To handle this, the LSTM would need to be made more complex, either by adding more layers or increasing the number of neurons per cell. This would significantly increase the complexity of the architecture, leading to longer training times. Moreover, LSTM’s ability to hold time-domain information decreases as its chain length increases. CNN enables the model to learn data characteristics effectively without significant information loss. Additionally, a single CNN layer typically has fewer trainable parameters compared to a single LSTM layer. Therefore, incorporating a CNN is a more efficient way to manage the complexity of the model while maintaining performance, rather than making the LSTM network more complex. CNN was chosen over other mathematical tools for temporal compression because it can learn the optimal weights to compress the data during training. This adaptability allows the model to adjust more flexibly compared to a fixed compression formula. Further, the reason to compress the time scale (and not enlarge it) is to utilise the whole dataset, in general, and put as many cycles as possible in a single sub-sample. The aim is to provide context from a wider timeframe to the succeeding LSTM network. If we enlarge the sampling interval, then it could lead to information loss owing to intervals (gaps) within the sampled data. Figure 2 shows the working of the CNN layer. So, it is better to encrypt the data meaningfully than to skip any part of it. The underlying logic is as follows: Let the sub-sample passed as input be represented by I, i.e., I = [\(I_1\), \(I_2\), \(I_3\), . . . \(I_m\)] where m is the number of features in the dataset. Then, the CNN operation on the \(J^{th}\) feature, i.e.,

where \(Z_j\) is the temporal compression output for the \(j^{\text {th}}\) feature, \(act_f\) is the activation function, \(Y_j^t\) represents the \(j^{\text {th}}\) feature at time step t, \(W_{tj}\) denotes the kernel weights, and the stride is 1. This compression is applied consistently across all features within the sub-sample, ensuring a standardised temporal compression process.

To feed cycles of varying lengths into the CNN, it is necessary to standardise their temporal dimension. This is achieved by calculating a compression ratio for each dataset. First, the maximum and minimum cycle lengths are identified, and a fixed reference cycle length is chosen, typically less than or equal to the minimum length.

LSTM layer

The output of the CNN layer is passed as an input to the LSTM. Since time-series data is being used in the current research, the best way to capture temporal dependency is to use the best recurrent network, LSTM20. The stacked LSTM architecture has been framed to process the data. Figure 3 shows the operational mechanism of LSTM layers. A 3-layer stacked architecture is used to aid the LSTM network in learning the sophisticated data characteristics. 3 memory cells at a single time stamp have been used to forward the important information temporally. The reason to choose a 3-layer architecture is based on results obtained after experimenting with 2 to 5 layers. It was found that 3 layers were giving better results. Almost similar results are obtained with 3 and 4 layers, while 4 and 5 layers took longer to train the model without any improvement in the results.

For each LSTM layer i, the state transitions are:

Forget Gate:

Input Gate:

Cell State Update:

Output Gate:

Where \(\sigma\) = sigmoid activation function, \(W_f, W_i, W_C, W_o\) = weight matrices, \(b_f, b_i, b_C, b_o\) = bias vectors, \(h_t\) = hidden state at time t, \(C_t\) = cell state at time t, and \(\odot\) = element-wise multiplication.

The number of neurons per LSTM cell in the first, second, and third LSTM layers is 100, 80, and 60, respectively, for charging as well as discharging input. The output of the LSTM1, LSTM2, and LSTM3 of the first phase is fed to LSTM4, LSTM5, and LSTM6, respectively, along with CNN compressed sub-samples of discharging data. The final output of the two phases, having six LSTM layers, is passed to dense layers connected at the end of the network. Mathematically, it is expressed as follows: Let us suppose that the output of CNN is denoted by charg/disch, and Uhi, ci denotes the output of an LSTM cell where charg/disch stands for charging/discharging phase, h for hidden state, c for cell state, and i for LSTM layer sequence number. The processing of data through stacked LSTM is given by the following equation:

where Uhi(j), ci(j) represents the output of an LSTM cell at layer i and timestamp j. As stated earlier, the single battery sample is sub-sampled in the current research. Each sub-sample comprises data from a range of n cycles, with n varying from 1 to the total number of cycles available. The optimal cycle number has been determined to be 3 after comparing with other values in the range of 2 to 5. Consequently, each sub-sample incorporates data derived from precisely 3 cycles and enables mapping from the latest 3 cycles to SoH. These sub-samples are fed to the model using the sliding window technique. Overall, each sub-sample first goes through the CNN layer for temporal compression, and then its result is fed into the LSTM network, which maps the temporal dependency of the sub-sample through its chain structure. This helps capture the intra-sub-sample time dependency. For capturing inter-subsample relationships, the LSTM network has been made ‘stateful’, which means that the LSTM states are not reset after processing a sub-sample. When the chronologically ordered next sub-sample is fed to the LSTM network, the final states of the previous sub-sample are used. This makes it possible to do sub-sampling of the input sample because a ‘stateful’ LSTM can capture inter-sub-sample dependencies. This contributes to making the model lightweight since at a single instance, only a sub-sample of data is fed to it. Along with a ‘stateful’ LSTM, the batch size is set to 1 without shuffling, so that only one sub-sample is fed to the network in a single batch and its final states are propagated to the next batch. Hence, temporal relationships are optimally captured in the model architecture.

Where \(W_{\text {out}}\) = output layer weights, \(b_{\text {out}}\) = output layer bias, \(H_{\text {final}}\) = final hidden state from stacked LSTM, \(X_{\text {charg}}\), \(X_{\text {disch}}\) = charging and discharging phase data, \(O_{\text {charg}}\), \(O_{\text {disch}}\) = CNN outputs for each phase, and \(H_{\text {charg}}\), \(H_{\text {disch}}\) = LSTM hidden states for each phase.

Hyperparameter tuning using Optuna

Optuna is designed to automatically search for the best set of parameters that either minimise or maximise a given objective function. Unlike traditional approaches that rely on a fixed, manually defined search space, Optuna constructs this space dynamically as the optimisation progresses. Each attempt to evaluate the objective function is called a trial. To improve efficiency, Optuna also integrates pruning strategies that stop unpromising trials early, preventing unnecessary computations. For sampling, it employs advanced optimisation techniques such as Bayesian optimisation, Tree-Structured Parzen Estimators (TPE), and multi-armed bandit methods. The framework is organised around three main components: the study, which represents the entire optimisation process; the trial, which corresponds to one evaluation with a specific set of hyperparameters; and the sampler, the algorithm that decides which parameter values should be tested next.

Optuna defines hyperparameter optimisation as the task of finding the parameter set \(\theta\) that minimises the objective function \(f(\theta )\), as shown below :

In Equation (12), \(\theta\) denotes the set of hyperparameters, \(\Theta\) represents the overall search space, and \(f(\theta )\) refers to the objective function that needs to be minimised.

The key hyperparameters used for training the Opt-KAN-XAI model are summarised in Table 3. The model was trained for 300 epochs, allowing sufficient iterations to effectively learn and capture the underlying patterns in the data. For optimisation, the Adam algorithm was employed owing to its adaptive learning rate mechanism and strong performance in handling sparse data.

-

Train-Test Split and Cross-Validation: The dataset has been split chronologically into an 80:20 ratio, with 80% used for training and 20% reserved for testing. To improve the model’s robustness, Five Cross Validation is utilised where the dataset has been partitioned into five equally sized folds (K=5), with each fold serving once as the validation set while the remaining folds were used for training. This process was repeated until all folds had been used for validation. This approach exposes the model to different subsets of data, reducing reliance on any single partition and enhancing its ability to generalise across diverse battery degradation patterns.

-

Regularisation: The model incorporates built-in mechanisms to manage complexity during training. These dynamically adjust regularisation parameters, preventing excessive parameter growth and striking a balance between model simplicity and predictive accuracy.

Table 4 shows a comparison of training time, inference speed (testing time), and memory usage for several deep learning models used for battery SoH prediction. These metrics are critical for evaluating the computational efficiency and practical deployment of models in real-time applications.

Explainability

As deep learning models advance and gain prominence in predictive systems, their growing complexity often obscures the underlying decision-making processes. This opacity has led to a rising demand for transparent and interpretable frameworks. XAI has emerged to address this challenge, aiming to balance high predictive accuracy with interpretability. XAI techniques fall broadly into two categories: post-hoc and intrinsic methods. Post-hoc approaches focus on interpreting the decisions of already trained models. Among the most prominent are SHAP and LIME. SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) offers a mathematically grounded way to quantify the contribution of each input feature to a model’s output, fostering a global understanding of feature importance. In contrast, LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) provides local fidelity by approximating a model’s behaviour around a specific prediction, offering insight into why a model made a particular decision.

SHapley Additive exPlanation

SHAP is a model-agnostic post-hoc method that can be applied to any machine learning model. Rooted in game theory, it evaluates each player’s contribution to the overall payoff. In the context of machine learning, the players correspond to features, and the payoff corresponds to the model’s output. SHAP assigns an importance score to each feature, reflecting its influence on the model’s prediction. These scores are computed by considering all possible combinations of features, ensuring that every scenario, including subsets of features, is accounted for. Because the computational cost of SHAP grows exponentially with the number of features, an efficient approximation called Kernel SHAP has been introduced. The mathematical formulation of the SHAP approach is given in Equation (13).

Where (g) is the explanation model, \(z' \in (0,1)^{M}\) is the vector of features, M is the maximum coalition size of the vector, and \(\phi _{j} \in R\) is the weight assigned to each feature for feature j. The pseudo code for SHAP is illustrated in Algorithm 2.

Experimental setup and results

In this research, the NASA dataset of two batteries comprising B0005 and B0007 has been used to perform the experiments. The minimum hardware requirements to perform the experiments are 8GB RAM, an i5 processor, and an NVIDIA GPU. The language used to perform the implementation is Python,y and the libraries used are Numpy, Pandas, opt, Tensorflow, Keras, and Matplotlib. The performance evaluation is conducted through the utilisation of four parameters comprising MSE, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE.

a. Root Mean Square Error (RMSE)

b. Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

c. Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE)

d. Mean Squared Error (MSE)

Results and discussion with comparison

OptiCNN-SLSTM framework is developed, incorporating a hybrid of CNN and stacked LSTM networks, to assess the SoH estimation for batteries B0005 and B0007. SoH estimation curves have been generated for various models, including LSTM, CNN combined with Bidirectional LSTM (CNN + BiLSTM), CNN combined with stateless LSTM (CNN + stateless LSTM), and the proposed Optuna optimised CNN combined with stacked stateful LSTM. The results for all the models have been obtained after hyperparameter tuning. SoH estimation for the B0005 and B0007 batteries has been conducted over a span of 167 cycles, and the actual and predicted results are visually presented in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. Based on the observations from the plots, it has been noted that the SoH estimation results of the OptiCNN-SLSTM model exhibited superior performance compared to the PINN, CNN + BiLSTM, and KAN + LSTM models. Results for models other than the OptiCNN-SLSTM have been shown to validate the architecture of the proposed model through comparisons with other models that are lighter or more complex than it. This has helped to design the balanced architecture of OptiCNN-SLSTM, which can optimally map battery data to SoH.

There is a closeness between the results of PINN and KAN + LSTM, as the LSTM network in CNN-BiLSTM does not retain the state information of a sub-sample (batch) before feeding the next sub-sample. This leads to the elimination of inter-sub-sample mapping. Hence, KAN LSTM fails to outperform PINN, despite having a heavier architecture. In the case of CNN+BiLSTM, it includes a PINN network that performs temporal mapping in both forward and backwards directions. When the network runs backwards in time, it loses the context of the decrease in SoH with decreasing cycle number. It fails to do inter-sub-sample mapping when the data is reversed. OptiCNN-SLSTM’s accuracy demonstrates that it is a balanced model, losing its effectiveness when its architecture is modified to a more complex or simplified version.

Furthermore, the evaluation of the performance of the OptiCNN-SLSTM model for batteries B0005 and B0007 has been conducted using various metrics, including MSE, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE. The corresponding results are presented in Table 5 and Table 6. The data indicate that the OptiCNN-SLSTM model demonstrated robust performance compared to the established models, evident from its RMSE, MSE, mean MAE, and MAPE values of 2.15%, 0.046%, 1.7%, and 1.1% for B0005, and 2.18%, 0.047%, 1.5%, and 0.9% for B0007, respectively.

Figure 6 shows the training and validation error curves of OptiCNN-SLSTM. The training loss decreases rapidly at the start and then stabilises, while the validation loss follows a nearly parallel trend, indicating strong generalisation and minimal overfitting. Unlike CNN, which converges quickly but plateaus, and LSTM, which converges slowly, OptiCNN-SLSTM combines fast feature extraction with long-term temporal learning, offering a more efficient approach. The smooth curves confirm efficient convergence, robustness, and reliable performance for battery SoH estimation.

Explainability results

Figure 7 illustrates the feature importance based on SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) values, which are commonly used to interpret predictions from machine learning models. The x-axis represents the mean absolute SHAP value, indicating the average contribution of each feature to the model’s output. The y-axis lists the feature names. Among all features, QC stands out as the most influential, demonstrating the highest average impact on the model’s predictions. Following QC, \(cycle\_number\) and chargetime are also identified as significant contributors, suggesting that battery cycle characteristics and charging behaviour play key roles in the model’s decision-making process. Features such as IR (likely internal resistance), Tmax, Tmin, and Tavg (temperature-related features) exhibit moderate importance. QD appears to have the least influence among the listed features. Overall, the plot highlights that the model relies most heavily on QC and cycling-related metrics, with SHAP values providing a transparent way to understand how each feature affects the model’s predictions.

This SHAP waterfall Fig. 8 analyses the prediction for Sample 21, showing how different features contribute to the final model output of f(x) = 0.195. The analysis begins with a baseline expectation E[f(X)] of 0.192 and demonstrates how each feature shifts the prediction above or below this baseline.

The most significant contributor is the QC feature with a SHAP value of -0.951, which has a strong positive impact of +0.06 on prediction. (QC) capacity appears as the most important feature because SoH is inherently defined on the basis of capacity fade, i.e., the ratio of available capacity to nominal capacity. QC capacity directly reflects this usable charge storage capability, and thus its degradation has the most pronounced influence on SoH compared to other parameters (e.g., voltage or temperature), which contribute more indirectly through their impact on ageing. This is followed by several features that have smaller negative impacts: IR (-0.966) contributes -0.02, cycle_number (-0.954) contributes -0.01, another IR feature (-0.953) contributes -0.01, and QC (-0.965) contributes -0.01. The remaining features - QD (-0.963), Tmax (-0.958), and chargetime (-0.956) each contribute small negative adjustments of -0.01 to the final prediction.

The waterfall structure illustrates how these individual feature contributions accumulate from the baseline expectation of 0.192 to reach the final predicted value of 0.195. The large positive contribution from the first QC feature is the primary driver that elevates the prediction above the baseline, while the other features provide minor negative adjustments.

Case study using Oxford dataset with comparison

The OptiCNN-SLSTM has been validated on the Oxford dataset21. The dataset comprises four distinct layers. Layer 1 encompasses Cells 1 to 8, denoting individual cell units. Layer 2 involves characterisation cycles labelled with cycle numbers. Layer 3 contains specific parameters: 1-C charge (C1ch), 1-C discharge (C1dc), pseudo-OCV charge (OCVch), and pseudo-OCV discharge (OCVdc). Lastly, layer 4 includes data attributes such as time (t), voltage (v), charge (q), and temperature (T). For each cell in the Oxford dataset, the cycle data is not continuous. Data is provided for a cycle occurring after an interval of 100 cycles. The cell-1 data is used for training, and cell-2 is used for testing. After data balancing through the averaging technique, the optimal values for the hyperparameters are 2.95, 102, and 102 for the number of cycles per sub-sample, CNN kernel size for charging sub-sample, and CNN kernel size for discharging sub-sample, respectively. It is worth noting that all the models under consideration underwent hyperparameter tuning before obtaining their results.

The SoH estimation for cell-1 is shown in Fig. 9. Comparing the NASA dataset (167 cycles) and the Oxford dataset (approx. 8000 cycles), the results for the NASA dataset are more precise than the Oxford dataset. For each cell in the Oxford dataset, the cycle data is not continuous. This is because in the Oxford dataset, when considering the latest n cycles, there is a gap of 100 cycles between any 2 adjacent cycles. Such a distribution of data leads to the learning of general trends in data by the model instead of predicting in detail. The detailed error predictions at various points (cycles) in time, depicting the precision variation, have been shown in the Table 7.

For cell-2, the SoH estimation plot is depicted in Fig. 10. The abrupt drop in SoH after the 80% mark indicates the completion of the battery’s RUL, making it unsuitable for further use. As the battery approaches its End of Life Cycle (EOL), the ’Knee’ phenomenon22 occurs, where the rate of capacity (SoH) decay accelerates, and the battery enters a non-linear decay phase. In this phase, a mapping relationship between the ageing mechanisms of the electrode material and the nonlinear characteristics needs to be established. To accurately train the model beyond the RUL, this mapping, along with sensor data, should be included so that the model can account for significant changes in battery characteristics.

It is worth noting that PINN LSTM has a huge gap from the OptiCNN-SLSTM due to a drawback in the former’s architecture. The PINN has an LSTM network that does not retain the previous sub-sample (batch) state before processing the next sub-sample. This defers the inter-sub-sample mapping. But OptiCNN-SLSTM uses stateful LSTM, which can retain the previous sub-sample (batch) state before processing the next sub-sample. Hence, OptiCNN-SLSTM performs better than CNN+ BiLSTM. The aforementioned drawback in CNN+stateless LSTM also leads to the closeness between its result and that of only the KAN LSTM model, even though the former has a heavier architecture. Moreover, the error plots of MSE and RMSE have been plotted for cell-1 and cell-2 to show the comparison of OptiCNN-SLSTM with existing base models. The RMSE for cell-1 and cell-2 on OptiCNN-SLSTM is 0.67% and 1.02%, respectively. Similarly, MSE for cell-1 and cell-2 is 0.004% and 0.01%, respectively. Based on the research findings, it has been observed that the OptiCNN-SLSTM model demonstrated strong performance not only on the NASA dataset but also on the Oxford dataset.

Case study using TIET E-kart dataset with comparison

This case study focuses on a LiFePO4 battery pack manufactured by Likraft and deployed in an electric cart (E-kart) used for campus transportation at TIET. The objective is to design a real-time SoH prediction system by leveraging the battery’s intrinsic characteristics and its operating parameters. To achieve this, the pack is equipped with sensors that continuously monitor voltage, current, temperature, and cycle count. These parameters are fed into the Battery Management System (BMS), which aggregates sensor data along with the estimated SoH. As illustrated in Fig. 11, the system enables real-time SoH prediction for the E-kart.

The BMS is further integrated with Wi-Fi and Bluetooth modules, allowing seamless data transmission to a central server or cloud for storage and advanced analytics. The proposed model is trained using this data, ensuring the prediction process is adaptive to real-world usage patterns. The experimental evaluation confirms the robustness of the model, achieving remarkably low error values: MSE of 0.001%, RMSE of 0.03%, and MAE of 0.28%. These results underline the accuracy and reliability of the framework in monitoring battery health under dynamic operating conditions. The detailed specifications of the LiFePO4 battery pack are summarised in Table 8.

Comparison of OptiCNN-SLSTM with existing works

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed OptiCNN-SLSTM model, its results have been systematically compared with several state-of-the-art approaches, including those of Ning et al.9, Huixing et al.23, Ang et al.24, Robbert et al.25, as well as standard deep learning baselines such as CNN and LSTM models.

The comparison spans multiple benchmark datasets, namely the NASA batteries B0005 and B0007, and the Oxford dataset, which are widely used in SoH and RUL estimation research.

Ning et al.9 and Huixing et al.23 focused their investigations on the B0005 and B0007 cells. Their works primarily employed data-driven deep learning models but still exhibited relatively higher error rates, particularly when dealing with long-term degradation patterns. Ang et al.24, on the other hand, concentrated only on the B0007 cell, introducing a refined estimation strategy. While their model achieved slightly improved performance, it still struggled to capture nonlinear degradation under fluctuating conditions. Robbert et al.25 conducted their experiments on the Oxford dataset, leveraging a different experimental setup and data characteristics. Although their results were competitive, they too highlighted the need for architectures that can better generalise across datasets.

Meanwhile, the CNN and LSTM baselines were implemented to provide a fair comparison with the proposed hybrid framework. CNN alone was able to extract spatial patterns but lacked long-term temporal modeling capability, leading to moderate accuracy. Similarly, LSTM captured sequential dependencies effectively but was less efficient at feature extraction from raw signals. Their inclusion highlights how the hybrid OptiCNN-SLSTM achieves a more balanced and robust performance.

The comparative analysis summarised in Table 9 clearly shows that OptiCNN-SLSTM consistently outperforms not only prior studies but also baseline CNN and LSTM models across all datasets. Specifically, it reduces RMSE by approximately 0.14% compared to LSTM and by 0.21% compared to CNN on B0005, by 0.08% and 0.14% respectively on B0007, and by 0.19% and 0.32% on the Oxford dataset.

These findings highlight that while CNN and LSTM individually capture certain aspects of the degradation process, the hybrid OptiCNN-SLSTM leverages their complementary strengths. The convolutional layers efficiently extract spatial features from the input signals, while the stacked LSTM layers capture long-term temporal dependencies. The integration of Bayesian optimisation further ensures that the model operates with well-tuned hyperparameters, preventing overfitting and enhancing generalisation. By achieving consistently lower prediction errors, OptiCNN-SLSTM advances the accuracy of battery SoH estimation and demonstrates adaptability across diverse datasets, including both NASA and Oxford benchmarks.

Overlapping vs. Non-Overlapping: SOH error metrics

Table 10 gives the comparison of SOH error metrics in overlapping samples (stride<window) and non-overlapping samples (stride\(=\)window). Here, overlapping in samples consistently reduces error metrics (RMSE, MAE, and MAPE) across all models by preserving temporal continuity, retaining transitional information, and enriching feature extraction. PINN and KAN-LSTM exhibit moderate improvements, as they already leverage physics fundamentals and attention, respectively. CNN+BiLSTM benefits more, as overlapping enhances both local feature learning and sequential modelling. The proposed OptiCNN-SLSTM achieves the highest performance, reducing RMSE from 3.1–3.8% to 2.15% and MAPE to just 1.1%, confirming its effectiveness in combining CNN’s local feature extraction with SLSTM’s long-term dependency learning for accurate battery health forecasting. The Fig. 12 shows the stride window for overlapping and non-overlapping samples taken in the study.

Conclusion

In this study, we introduce OptiCNN-SLSTM, a lightweight hybrid deep learning model that combines a one-dimensional CNN with a stacked LSTM to predict battery SoH after each operational cycle. The CNN is used for temporal compression, while the stateful LSTM effectively captures both short and long-term dependencies within the compressed sequences. To further enhance performance, we employed Optuna for hyperparameter optimisation, making the model not only accurate but also computationally efficient. We evaluated the model on the NASA dataset using two batteries (B0005 and B0007). OptiCNN-SLSTM achieved strong predictive accuracy, with RMSE values of 2.15% and 2.18%, respectively. To ensure robustness, the model was also validated on the Oxford dataset, where cell-1 was used for training and cell-2 for testing, achieving RMSE values of 0.6% and 1.02%, respectively. Finally, we compared OptiCNN-SLSTM with existing approaches, including those by Ning et al.10, Huixing et al.23, and Ang et al.24 on the NASA dataset, and Robbert et al.25 on the Oxford dataset. Across all cases, OptiCNN-SLSTM consistently outperformed prior methods, reducing RMSE by 0.28% and 0.42% on B0005, 0.29%, 1.54%, and 0.38% on B0007, and 0.59% on cell-2.

The approach can be extended to other battery chemistries and real-world conditions, integrated with additional features like temperature or usage patterns, and deployed on edge devices as TinyML for real-time SoH monitoring. Explainable AI techniques can further enhance the understanding of battery ageing mechanisms. Future work will incorporate partial-cycle and random SoC training to further align with real-world battery usage.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analysed in this study is available from the corresponding author upon request (Ashima Singh).

References

Tian, H., Qin, P., Li, K. & Zhao, Z. A review of the state of health for lithium-ion batteries: Research status and suggestions. J. Clean. Prod. 261, 120813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120813 (2020).

Basia, A., Simeu-Abazi, Z., Gascard, E. & Zwolinski, P. Review on state of health estimation methodologies for lithium-ion batteries in the context of circular economy. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 32, 517–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirpj.2021.02.004 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. On the feature selection for battery state of health estimation based on charging-discharging profiles. J. Energy Stor. 33, 102122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2020.102122 (2021).

Khodadadi Sadabadi, K., Jin, X. & Rizzoni, G. Prediction of remaining useful life for a composite electrode lithium ion battery cell using an electrochemical model to estimate the state of health. J. Power Sour. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2020.228861 (2020).

Rauf, H., Arshad, N. & Khalid, M. Machine learning in state of health and remaining useful life estimation: Theoretical and technological development in battery degradation modelling. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111903 (2021).

Kaur, K., Garg, A., Cui, X., Singh, S. & Panigrahi, B. K. Deep learning networks for capacity estimation for monitoring soh of li-ion batteries for electric vehicles. Int. J. Energy Res. 45(2), 3113–3128. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.6005 (2021).

Oji, T. et al. Data-driven methods for battery soh estimation: Survey and a critical analysis. IEEE Access https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3111927 (2021).

Xu, Z., Wang, J., Lund, P. & Zhang, Y. Estimation and prediction of state of health of electric vehicle batteries using discrete incremental capacity analysis based on real driving data. Energy 225, 120160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.120160 (2021).

Li, N. et al. An indirect state-of-health estimation method based on improved genetic and back propagation for online lithium-ion battery used in electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Vehic. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2022.3196225 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Xiong, R., Hongwen, H. & Pecht, M. Long short-term memory recurrent neural network for remaining useful life prediction of lithium-ion batteries. IEEE Trans. Vehic. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2018.2805189 (2018).

Sylvestrin, G. R. et al. State of the art in electric batteries’ state-of-health (soh) estimation with machine learning: A review. Energies https://doi.org/10.3390/en18030746 (2025).

Ma, Y., Shan, C., Gao, J. & Chen, H. Multiple health indicators fusion-based health prognostic for lithium-ion battery using transfer learning and hybrid deep learning method. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 229, 108818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2022.108818 (2023).

Qin, Y., Arunan, A. & Yuen, C. Digital twin for real-time li-ion battery state of health estimation with partially discharged cycling data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.04622https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2212.04622. (2022) Accepted for IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics

Sharma, R., Bala, A. & Singh, A. Enhancing battery health monitoring using a stacking approach for precise and real-time state-of-health estimation. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-025-10453-x (2025).

Kamboj, R. K., Singh, M., Singh, A. & Bala, A. Explainable artificial intelligence driven estimation of remaining useful life for lithium-ion battery. Ionics https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-025-06707-1 (2025).

Qin, Y., Arunan, A. & Yuen, C. Digital twin for real-time li-ion battery state of health estimation with partially discharged cycling data. IEEE Trans. Indus. Inform. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2022.3230698 (2023).

Ren, L. et al. A data-driven auto-cnn-lstm prediction model for lithium-ion battery remaining useful life. IEEE Trans. Indus. Inform. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2020.3008223 (2020).

Dai, H., Zhao, G., Lin, M., Wu, J. & Zheng, G. A novel estimation method for the state of health of lithium-ion battery using prior knowledge-based neural network and markov chain. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 66(10), 7706–7716. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2018.2880703 (2019).

Wang, Q., Cai, X., Ye, M., Sauer, D. U. & Li, W. Transferable data-driven capacity estimation for lithium-ion batteries with deep learning: A case study from laboratory to field applications. Appl. Energy 350, 121747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.121747 (2023).

Yu, Y., Si, X., Hu, C. & Zhang, J. A review of recurrent neural networks: Lstm cells and network architectures. Neural Comput. 31, 1235–1270. https://doi.org/10.1162/neco_a_01199 (2019).

Dhillon, A., Singh, A. & Bhalla, V. K. Biomarker identification and cancer survival prediction using random spatial local best cat swarm and bayesian optimized dnn. Appl. Soft Comput. 146, 110649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2023.110649 (2023).

Birkl, C. Diagnosis and Prognosis of Degradation in Lithium-Ion Batteries (University of Oxford, 2017).

Gao, Z. et al. Soh estimation method for lithium-ion batteries under low temperature conditions with nonlinear correction. J. Energy Stor. 75, 109690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.109690 (2024).

Meng, H., Geng, M. & Han, T. Long short-term memory network with bayesian optimization for health prognostics of lithium-ion batteries based on partial incremental capacity analysis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 236, 109288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2023.109288 (2023).

Ang, E. Y. M. & Paw, Y. C. Linear model for online state of health estimation of lithium-ion batteries using segmented discharge profiles. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 9(2), 2464–2471. https://doi.org/10.1109/TTE.2022.3206469 (2023).

Chen, J., Manivanan, M., Duque, J., Kollmeyer, P., Panchal, S., Gross, O. & Emadi, A. A convolutional neural network for estimation of lithium-ion battery state-of-health during constant current operation. In: 2023 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference & Expo (ITEC), pp. 1–6 https://doi.org/10.1109/ITEC55900.2023.10186914 (2023).

Xu, G., Xu, J. & Zhu, Y. Lstm-based estimation of lithium-ion battery soh using data characteristics and spatio-temporal attention. PLOS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0312856 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ashima Singh and Sanju Singh designed the study. Anju Bala collected the data. Ashima Singh, Sanju Singh, and Anju Bala analysed the data. Ashima Singh, Sanju Singh, and Rahul Kumar Kamboj collaborated on manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, A., Singh, S., Kamboj, R.K. et al. Explainable OptiCNN-SLSTM hybrid model for enhanced lithium-ion battery state of health prediction. Sci Rep 15, 44364 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28091-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28091-6