Abstract

The underwater heave plates (UHPs), which are suspended beneath the bridge by flexible cables, can be temporarily utilized to mitigate bridge flutter. This study employs a simulation method to investigate the additional damping characteristics of the UHPs for controlling bridge vibration under various conditions. An analytical model including a rigid bridge deck, square heave plates, and suspension cables is developed. Detailed calculation steps for the system’s response under impulsive conditions are provided. The accuracy of the developed simulation model and computational program is confirmed by the experiments for a simplified bridge deck. The control effects of the UHP’s dimensions, mass, and cable stiffness on the deck’s torsional vibration are analyzed under different torsional amplitudes and frequencies. Explicit formulas for determining the UHP mass, as well as the corresponding maximum cable force and damping ratio, are derived, and their accuracy are validated by comparing with the directly simulated results. The proposed simulation method simplifies the research process and improves overall efficiency. It facilitates the rapid optimization of the UHP’s mass corresponding to the best control performance. This research provides valuable insights for designing, applying, and promoting UHPs in bridge flutters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Under extreme offshore strong wind conditions, bridges may experience large-amplitude catastrophic flutter, which must be strictly prevented. Control measures for bridge flutter include structural, aerodynamic, and mechanical approaches. Structural measures1 often significantly increase construction costs. Aerodynamic measures2, such as deflectors3, central stabilizing plates4, and edge wing plates5,6, vary in shape and layout parameters depending on the specific bridge and their applicability is typically determined through model tests or numerical simulations. Mechanical measures7 include passive energy dissipation devices such as Tuned Mass Dampers (TMD)8,9 and Tuned Mass Dampers with Inertia (TMDI)10,11, as well as active energy dissipation devices like Active Mass Dampers (AMD)12, Active Rotational Inertia Dampers (ARID)13, eddy current dampers14, etc. According to the study by Chen and Kareem15, passive control devices such as TMDs are effective in controlling linear flutter (where the aerodynamic damping of the deck increases gradually with wind speed after the deck starts to vibrate). However, their ability to control nonlinear flutter (where the aerodynamic damping of the deck increases rapidly with wind speed after the deck starts to vibrate) is ineffective. Active control devices require a stable power supply, which presents a significant challenge in extreme weather conditions that can induce bridge flutter. Therefore, passive flutter control devices with strong energy dissipation capabilities are more attractive.

UHPs can be used as passive control devices to enhance the bridge’s damping and wind-resistance performance for many large-span bridges crossing rivers or seas. The UHP is suspended beneath the bridge by flexible cables. When the bridge experiences vertical or torsional motion, the UHP moves up and down in water, dissipating the bridge’s mechanical energy and controlling its vibrations. For bridges without navigational clearance requirements, the UHP may be installed permanently, and the VIV, buffeting and even galloping can be mitigated. In contrast, for bridges with navigation requirements, the UHPs are installed temporarily under extreme wind conditions, and the VIV will not occur, and large-amplitude buffeting can be prohibited. In such cases, the UHP may serve as a temporary flutter control device that can be installed and removed within one day or even a shorter time. Flutter in large-span offshore bridges typically occurs only during extreme wind conditions, a rare event that may occur once every ten years or even several decades. Moreover, such extreme wind events can be predicted in advance. Therefore, the UHP can be quickly installed before the onset of strong winds and swiftly removed after the wind event, which doesn’t affect navigation beneath the bridge in normal weather.

The UHP’s submergence depth is generally 20–30 m, which is easy to achieve. The maximum wave height offshore is generally around 5 m, meaning the UHP is almost not influenced by the surface waves. The water flow induces a horizontal displacement of the UHP, causing a angle between the cable’s axis and the vertical direction. However, the flow velocity is generally low at 20 to 30 m depth, and the horizontal hydrodynamic force acting on the UHP is much smaller than its gravitational force, meaning the cable’s inclination angle remains very small (less than 1°). Furthermore, the UHP primarily dissipates energy through vertical motion, the influence of water flow on the UHP can be negligible.

Mao16 conducted experimental investigations on the additional damping characteristics provided by UHPs for the vertical vibration of the deck. The results indicated that the damping ratio induced by UHPs could reach up to approximately 10%. Zhang’s17 experimental study demonstrated that UHPs can significantly enhance the flutter critical wind speed of the deck. However, in Zhang’s setup, only a single dumbbell-shaped heave plate was suspended beneath the deck, and this configuration was found to be insufficient in fully exploiting the energy dissipation potential of the UHP when controlling torsional motion. In An’s18 research, in order to improve the effectiveness of UHPs in mitigating torsional vibrations of the deck, a configuration involving two symmetrically arranged heave plates suspended on either side of the deck was adopted. The experimental results showed that this arrangement provided effective control over both soft and hard flutter of the girder.

However, all the above studies were based solely on physical experiments, in which the motion of the UHPs was difficult to monitor, and the available data for in-depth analysis were insufficient. Consequently, the analysis was primarily limited to the displacement response of the deck, and a detailed understanding of the energy dissipation mechanism of UHPs remained lacking. Moreover, these studies were conducted under scaled model conditions only; the additional damping characteristics of UHPs under full-scale conditions, as well as parameter selection strategies for their optimal performance, have not yet been clarified. These limitations hinder the further optimization and broader application of the UHP.

The additional damping characteristics of UHPs for mitigating bridge vibration can be studied by water tank test method and Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) method. However, water tank tests are challenging to implement and require substantial work. Since the optimal parameters of the UHP are unknown, extensive preliminary experiments may be required to determine the appropriate experimental parameter range, which results in a heavy workload. The parameters of the deck and UHP can only be selected based on the experimental conditions, and it may not be possible to adjust them to the ideal target range, which could lead to insufficient research on the UHP. CFD methods can provide rich data but are difficult to implement and computationally slow. The main reasons for the arisen challenges conclude: ① The coupling of motion between the different structures and between the structure and fluid must be accounted for in the calculations, resulting in a complex computational process. ② The computational area may need to be discretized into a large number of grid cells, potentially reaching millions or more for experimental size, which will result in a substantial consumption of computational resources and time.

This paper develops a coupled computational model for the deck-cables-UHPs system to study the control characteristics of UHPs on bridge vibrations, with the hydrodynamics of the UHPs calculated using empirical formulas. The system’s response time history is obtained by iteratively solving in the time domain. This approach not only significantly reduces the difficulty and workload of the study but also facilitates a comprehensive analysis of a wider range of parameter cases, allowing for a thorough understanding of the energy dissipation characteristics of the UHP.

Rectangular UHPs with a length-to-width ratio of 4 to 6 are more convenient for transportation and installation. The hydrodynamic forces acting on these UHPs during motion in water are similar to those of square UHPs with the same area19. The length-to-width ratio of the UHP needs to be determined based on the specific application. In this study, square UHPs are chosen for research convenience. Extensive research has been conducted on the hydrodynamic characteristics of UHPs, where the hydrodynamic forces acting on a UHP in water are generally divided into added mass force and drag force. In most research, these forces are then non-dimensionalized into the added mass coefficient Cm and drag coefficient Cd, which facilitates the calculation of the hydrodynamic forces during the motion of the UHP under similar conditions.

Prislin et al.20 investigated the hydrodynamic coefficients of single and multi-UHP systems with varying inter-plate spacing through free decay tests. Their results showed that when the Reynolds number exceeds 105, the hydrodynamic coefficients primarily depend on the Keulegan-Carpenter (KC) number. Several researchers, including Tao and Dray21, Wadhwa and Krishnamoorthy22, Li et al.23, An and Faltinsen24, Lopez-Pavon and Souto-Iglesias25, have conducted experimental studies on the effects of various parameters such as the scale ratio of UHPs, KC number, vibration frequency, and distance to the water boundary on the hydrodynamic characteristics of UHP. Their findings consistently show that the drag coefficient and added mass coefficient are mainly influenced by changes in the KC number and are largely unaffected by variations in vibration frequency. Medina-Manuel et al.26 studied the hydrodynamic coefficients of UHPs installed on floating wind turbines through forced motion and free decay vibration tests. They found that for the same KC number, the hydrodynamic coefficients obtained from both test methods were identical, and they provided formulas for calculating the added mass force and damping force of full-scale UHPs. Hegde and Nallayarasu27 investigated the effects of the diameter ratio (the ratio of UHP’s diameter to structure diameter) and immersion ratio (the ratio of immersion depth to UHP’s diameter) on damping effectiveness through CFD and experimental studies. They provided reference ranges for the optimal diameter and immersion ratios for effective damping. Additionally, Tian et al.19 and Zhang and Ishihara28 combined experimental and CFD methods to explore the effects of parameters such as UHP size, shape, and KC number on hydrodynamic coefficients, offering reference values for hydrodynamic coefficients under various conditions.

Bridge wind-induced vibrations include vertical and torsional vibrations, which can be simultaneously controlled by symmetrical placing UHPs on both sides of the bridge cross-section. In all vertical, torsional, or coupled bending-torsional motion cases, the UHP always moves in the vertical direction. Therefore, the control mechanism of the UHP is similar for all three vibration modes. Given the numerous possible conditions for calculating the three types of bridge motions and considering that torsional vibrations generally dominate during bridge flutter, the study simplifies the analysis by focusing primarily on controlling the bridge torsional vibrations by UHP. The UHPs are installed at particular positions along the bridge span, and the additional damping is related to the position due to different amplitude for the same vibration mode. For different vibration modes with different frequencies, the additional damping are different for the same amplitude. So, if several UHPs are installed at different positions, it is very complex to reveal the characteristics of additional damping ratios. In fact, in wind tunnel tests, a rigid segmental deck is usually employed to investigate the VIV and flutter behavior of a three-dimensional aeroelastic deck. As long as the similarity relations are satisfied, the results obtained from rigid segmental deck can be reasonably extended to investigate the response of a full bridge. This study mainly investigates the UHP’s additional damping characteristic for mitigating the bridge torsional vibration, thus only considering the torsional free decay vibration of the rigid segmental bridge deck. This study provides valuable preliminary insights into the UHP’s controlling mechanism and control performance. These findings serve as a reference for future studies on applying UHPs in controlling bridge wind-induced vibrations.

This study develops an analytical model for the rigid deck-cables-UHPs system. Detailed calculation steps for the system’s response under various impulsive conditions are provided and the corresponding computational analysis program is written. The accuracy of the established analytical model and computational program is validated through experimental tests. Based on this analytical approach, the effects of the UHP’s dimensions, mass, and cable stiffness on bridge deck’s torsional vibration control are investigated under different torsional amplitudes and frequencies. Finally, explicit formulas are proposed for calculating the square UHP’s mass, maximum cable tension, and additional damping ratio for optimal control performance by combining induction and three reasonable assumptions. This provides a method and parameter design reference for flutter control in long-span bridges.

Coupled response calculation of the deck-cables-UHPs system

Mechanical analysis model of the deck-cables-UHPs system

The UHP is suspended beneath the deck in the water by flexible cables, as shown in Fig. 1. When the deck experiences vertical or torsional vibrations, the UHPs move vertically under the traction of the cables, dissipating the deck’s mechanical energy and controlling the deck’s vibrations. This paper establishes a analysis mechanical model for the coupled motion of the rigid deck-cables-UHPs system, focusing on the UHP control effect on the deck’s torsional vibrations.

The static equilibrium position of the rigid deck, with a length of L, is taken as the displacement origin, and the initial position of the UHP is set at its displacement origin. Vertical upwards is assumed as the positive direction of vibration, and counterclockwise is assumed as the positive direction of torsional. The equations of motion for the vertical and torsional movements of the deck are as follows:

where mb and Jb respectively represent the mass and mass moment of inertia of the deck, Cbh, Kbh, Cbα and Kbα denote the damping and stiffness coefficients for the vertical and torsional motions of the deck, yb(t) and αb(t) represent the vertical displacement and torsional displacement of the deck, respectively. Ft(t) and Tt(t) correspond to the cables vertical force and torque on the deck. It should be noted that Ft(t)=⅀ Fti(t) and Tt(t)=⅀ Fti(t)×ds/2, where i denotes the index of the UHP (i = 1, 2), as shown in Fig. 1, here, index 1 denotes the left-side UHP, and index 2 denotes the right-side UHP. ds is the center-to-center distance between the UHPs symmetrically arranged on both sides of the deck cross-section. Since the primary focus of this study is on the additional damping provided by the UHP, it is assumed that the mechanical damping of the structure is zero. The simplified equation of motion for the deck is then given by:

Some reasonable assumptions are made for simplicity of analysis:

-

(1)

The deck and UHPs are both treated as rigid bodies, with local deformations caused by other loads neglected.

-

(2)

The UHPs only move in the vertical direction, with their torsional and horizontal motions disregarded. This assumption is based on the following: the UHP’s vertical motion consumes the deck’s mechanical energy. Mao’s16 study indicated that even a UHP’s inclination angle of 10° has a negligible effect on energy dissipation.

-

(3)

The UHPs are placed sufficiently deep below the water surface, with the effects of the water boundary and waves ignored.

In this study, two square UHPs with identical side lengths and masses are used in the transverse direction of the bridge. The UHPs motion equation in water is as follows:

where mp is the UHP’s mass, ypi is the vertical displacement of the ith plate. Fti denotes the total cable force on the ith plate. Fg and Fb denote the plate gravitational force and buoyancy in water, respectively. Fhi represents the hydrodynamic loading on the ith plate, which can be quantified by the Morison Eq. 29. Fg, Fb, and Fhi can be expressed as follows:

where g is the gravity acceleration, ρ is the density of water, Vp (= L2d) is the volume of the plate, L and d represent the length and thickness of the square UHP. \(\:{\dot{y}}_{pi}\) and \(\:{\ddot{y}}_{pi}\) represent the vertical velocity and acceleration of the UHP, Cd and Cm are the drag force coefficient and added mass coefficient, respectively. The calculations in this study are based on the hydrodynamic coefficient formulas proposed by Prislin et al.20 and Bearman et al.30, as follows:

where α = 8.0, KC = 2πA/L, A denotes the vibration amplitude of the plate.

The cable force is determined using a simplified mathematical model based on steel cables. The material stress wave transmission speed is (E/ρ)0.5, and the cable length typically ranges from 60 m to 100 m. For common materials, the strain force at the bottom end of the cable is transmitted to the top end within approximately 0.02 s. Given that the bridge’s flutter vibration period is around 5 s, the time delay for tension propagation along the cable can be neglected. Therefore, the tension along the entire cable length can be considered equal. The damping of the cables is ignored. The tensions in the left and right cables, Ft1 and Ft2, are expressed as follows:

where l, A, and E represent the length, cross-sectional area, and Young’s modulus of the cable, respectively.

Parameter design method for UHPs and cables

Changes in parameters such as the area and mass of the UHP and the cable’s cross-sectional area all influence the UHP’s additional damping characteristics for mitigating deck vibration. Therefore, for a deck with specific mass, mass moment of inertia, vertical vibration frequency, and torsional vibration frequency, it is necessary to adopt a rational method to optimize the UHP and cable parameters. The goal is to minimize the required material area and mass while achieving the desired additional damping ratio, reducing the overall project cost.

For large-span bridges, multiple UHPs are needed to achieve the desired additional damping ratio. The design parameters include the size and mass of a single UHP, the number of UHPs, and the stiffness of the cables. Several UHPs of the same size and mass, typically square-shaped, are used for convenience in research and design.

Generally, the larger the side length of the UHP, the greater the additional damping ratio it can provide to the deck. However, larger UHP sizes increase transportation and installation challenges and make it difficult to maintain the required stiffness. Additionally, more suspension points are needed along the deck’s transverse direction. Conversely, if the UHP’s size is too small, too many units will be required, leading to excessive length along the bridge’s longitudinal direction, which could reduce vibration control effectiveness. Therefore, the UHP side length should be neither too large nor too small, with an optimal recommended range of 4 m to 5 m.

The distance between the deck and the water surface typically ranges from 50 m to 80 m for large-span bridges across rivers or seas. The UHPs need to be submerged at least 20 m below the water surface, with the cable length is assumed to be 100 m in this study. The cable is made of Φ5.0 mm galvanized high-strength steel wire, with a tensile stiffness of approximately 4 × 104 N/m and a maximum tensile load capacity of around 4 × 104 N. It should be noted that increasing the stiffness of the cable does not necessarily lead to a larger additional damping ratio for the deck. When designing the cable, its tensile strength must be verified to ensure safety.

Since, in the case of flutter control, the deck will vibrate at a specific amplitude under the control of the UHPs, it is essential to investigate the damping effect of the UHP near the particular amplitude. The damping ratio calculated based on one cycle may overestimate the damping ratio of UHP with a smaller mass. This is because the UHP with a smaller mass may be pulled upward by the deck to a higher position, and then it falls too slowly, failing to dissipate the deck’s mechanical energy in the subsequent cycle. Therefore, the deck’s vibration damping ratio under the control of UHPs is calculated based on the first two cycles. The damping ratio is calculated using ζ = ln(A0/A2), where A0 is the deck’s initial torsional amplitude, and A2 is the torsional amplitude of the deck at the end of the second cycle.

The following outlines the optimization process for determining the mass of a single UHP, the cable’s total cross-sectional area, and the deck length that can be controlled with a given initial amplitude and target additional damping ratio. In the optimization design example, the deck is defined with a specific mass and mass moment of inertia per unit length, vertical vibration frequency, and torsional vibration frequency, and a single square UHP with a side length of 4 m is used. The specific design process is as follows:

-

(1)

The required additional damping ratio may vary for different decks to achieve the same increase in flutter critical wind speed or reduction in vibration amplitude. A 5% or even 3% additional damping ratio provided by the UHP has significant control effectiveness for soft flutter. However, for hard flutter, the effect of additional damping is relatively minimal, and achieving a 10% additional damping ratio is challenging. For conservatism, the additional damping ratio range considered in this study is approximately 5% to 15%.

-

(2)

Determine the position and spacing of the suspension points based on the deck’s actual conditions. Set a series of UHP mass (recommended range: [3: 0.5: 8] tons), initial tensile stiffness of the cables (1 × 106 N/m), and initial deck length (50 m).

-

(3)

For various UHP mass conditions, solve the coupled dynamic response of the deck-cables-UHPs system with relaxed constraints and calculate the deck’s motion-damping ratio under each condition. Specific calculation steps for this process are provided later.

-

(4)

Determine the optimal UHP mass based on the deck’s vibration attenuation damping ratios among various cases.

-

(5)

Select a series of UHP masses with smaller increments (e.g., 0.1 tons) around the optimal UHP mass determined in step (5), and repeat steps (3) and (4) to find the optimal UHP mass that provides the highest vibration attenuation damping ratio.

-

(6)

Evaluate whether the absolute difference between the calculated additional damping ratio and the target damping ratio is less than a predefined threshold (e.g., 0.5%). If the condition is not met, adjust the length of the controlled deck based on the relative difference, and repeat steps (2)-(5) until the condition is satisfied.

Calculation steps for deck-cable-UHP dynamics

The coupled dynamic response of the deck-cables-UHPs system is solved in the time domain. The specific calculation steps are as follows:

-

(1)

Set the initial vertical displacement (yb0), vertical velocity (\({\dot {y}_{b0}}\)), torsional displacement (αb0), and torsional velocity (\({\dot {\alpha }_{b0}}\)) of the deck, initial displacement (yp10) and initial velocity (\({\dot {y}_{p10}}\)) of the left UHP, the initial displacement (yp20) and initial velocity (\({\dot {y}_{p20}}\)) of the right UHP, initial tension in the left cable (Ft10), and initial tension in the right cable (Ft20). Set the time stepΔt (suggested value: 1/fα/1000, i.e., 1000 steps per period).

-

(2)

Set yp10 as the UHP’s amplitude and substitute it into Eqs. (9)–(10) to calculate Cm and Cd. Then, substitute these values, along with the system parameters and initial parameters set in step (1), into the reduced-order motion equations of the deck and UHPs:

The system’s coupled dynamic response is solved using the fourth-order Runge-Kutta method applied to Eqs. (13)–(15), yielding the values of yb(t1), \({\dot {y}_b}\)(t1), αb(t1), \({\dot {\alpha }_b}\)(t1), yp1(t1), \({\dot {y}_{p1}}\)(t1), yp2(t1), \({\dot {y}_{p2}}\)(t1) at the first time step.

-

(3)

The values of yb(t1), \({\dot {y}_b}\)(t1), αb(t1), \({\dot {\alpha }_b}\)(t1) are chosen as the initial values of yb, \({\dot {y}_b}\), αb, \({\dot {\alpha }_b}\) in Eqs. (13)–(14), respectively. The values of yp1(t1), \({\dot {y}_{p1}}\)(t1), yp2(t1), \({\dot {y}_{p2}}\)(t1) are chosen as the initial values of yp1, \({\dot {y}_{p1}}\), yp2, \({\dot {y}_{p2}}\) in Eq. (15).

-

(4)

The values of yb(t1), αb(t1), yp1(t1), yp2(t1) are substituted into Eqs. (11)–(12) to calculate Ft1 and Ft2. These results are then substituted into Eqs. (13)–(15) to solve for the values of yb(t2), \({\dot {y}_b}\)(t2), αb(t2), \({\dot {\alpha }_b}\)(t2), yp1(t2), \({\dot {y}_{p1}}\)(t2), yp2(t2), \({\dot {y}_{p2}}\)(t2).

-

(5)

Steps (3) and (4) are repeated iteratively to compute the system response over two periods, with time steps t0 (= 0), t1, t2, ……, tn,…… t5000.

-

(6)

The vertical vibration damping ratio ζh and/or the torsional vibration damping ratio ζα of the deck are calculated based on the system’s response. The damping ratio is calculated using ζ = ln(A0/A2), where A0 is the initial vertical amplitude or torsional amplitude of the deck, and A2 is the vertical or torsional amplitude of the deck at the end of the second cycle.

-

(7)

The value on the UHP’s envelope is used to calculate the Cm and Cd at each time step. Steps (1)–(7) are repeated. Verify whether the absolute difference between the damping ratios obtained from the two calculations is less than a specified threshold (e.g., 0.2%). If the condition is not met, the current step is repeated until it is satisfied. If the condition is met, the calculation is concluded.

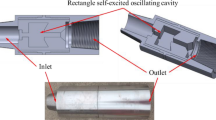

Verification of simulation accuracy

Compare the simulation results and experimental data to verify the accuracy of the simulation method. The experimental system is shown in Fig. 2. In the experiment, the cross-section of the deck is rectangular, with the rigid deck having dimensions of 3 m in length, 1.3 m in width, and 0.13 m in height. The mass of the deck is mb=120.2 kg, the mass moment of inertia is Jb=26.1 kg⋅m2, the vertical vibration frequency is fh=0.53 Hz, and the vertical motion exhibits a damping ratio of ζh < 0.5% when the amplitude Ah <8 cm. The torsional frequency is fα=0.94 Hz, with a corresponding damping ratio of ζα < 0.2% when the torsional amplitude Aα <7°. The tank dimensions are 3.3 m × 2.2 m × 2 m (length × width × depth). According to the study of Liu et al.31, the influence of side boundaries on the flow field can be neglected when the distance S between the heave plate and the boundary parallel to its motion direction satisfies S > 5D, where D is the diameter of a circular heave plate with the same area. In the present experiment, the distances between the horizontally oscillating UHP and both the sidewalls of the tank, as well as the adjacent UHP, all exceed 5D. Therefore, the influence of the tank sidewalls on the vibration control performance of the UHPs can be considered negligible. Moreover, Garrido-Mendoza32 and Wadhwa22 reported that the effects of the free surface and tank bottom can be ignored when the vertical distances between the heave plate and the water surface and tank bottom are greater than D and 0.5D, respectively. In this experiment, the vertical clearances between each UHP and both the free surface and tank bottom were set to 4D, ensuring that boundary effects from above and below can also be neglected. The related parameters for the experiment and simulation analysis are listed in Table 1. Two square UHPs are symmetrically arranged on both sides of the deck, with a spacing of 1.1 m between them. Each UHP has dimensions of 0.2 m × 0.2 m × 0.003 m (length × width × thickness), with a horizontal projected area (Ap) of 0.04 m2. Each UHP is suspended using four identical flexible cables, and the cable stiffness (Kc) is 36.5 × 103 N/m.

Figure 3 presents a comparison of deck’s displacement time histories obtained from simulation calculations and experiments for four different cases. They are in good agreement, which fully demonstrates the high accuracy of the simulation analysis method. Some discrepancies can be attributed to the following factors.

-

(1)

In the simulation cases, the deck undergoes pure vertical or pure torsional motion, whereas, in the experiments, it is impossible to ensure that the initial displacement excitation applied to the deck is purely vertical or purely torsional motion.

-

(2)

In the simulation calculations, the UHPs only move vertically. However, in tests, they experience horizontal motion as well.

-

(3)

The UHPs did not perform simple harmonic motion in the experiments, while the hydrodynamic coefficients used in the simulation were derived from simple harmonic forced vibration tests. Therefore, the results of the simulated hydrodynamic calculations inevitably exhibited some deviation from the actual behavior.

Overall, the simulation results were in good agreement with the experimental results, demonstrating the high accuracy of the simulation method in modeling the coupled motion of the deck-cables-UHPs system. This provides an efficient approach for rapidly, comprehensively, and intensely studying the additional damping effect of the UHPs and their ability to control the vibration characteristics of decks through simulation-based analysis.

In simulation, the values of Cm and Cd are calculated using empirical formulas. However, discrepancies may arise between these values and actual conditions, making it necessary to investigate the impact of Cm and Cd on the simulation results. The deck parameters in this section are the same as the one shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 4 illustrates the displacement time histories of the deck for different Cm and Cd. It can be observed that: ① The vibration period of the deck varies with the increasing of Cm. The control effect increases with the increase of Cm, while it is similar in the first two cycles for different Cm. ② When Cd changes, the deck’s vibrating period almost remains unchanged. Since the UHP’s additional damping effect during the first two cycles was primarily analyzed, deviations of Cm and Cd within 20% have a negligible impact on the research results.

Torsional vibration control analysis

The key parameters influencing the UHP’s control effectiveness include the UHP mass and area, the cable stiffness, the deck’s initial displacement, and vibration frequency. The control effects of these parameters on the deck’s torsional vibration are analyzed in this section. Suspension bridge decks spanning kilometers are typically constructed with steel box girders or trusses. The width of the deck typically ranges between 30 m and 50 m, with the mass per unit length generally ranging from 20 t to 50 t. The mass moment of inertia per unit length typically ranges between 0.5 × 107 kg·m2 to 1.5 × 107 kg·m2, and the torsional frequency fα typically ranges as [0.1, 0.25] Hz.

In this study, the parameters of rigid segmental deck are as follows: a length of 50 m, a width of 50 m, a mass per unit length of 40 t, and a mass moment of inertia per unit length of 1 × 107 kg·m2. The research range of fα is chosen as [0.1: 0.05: 0.25] Hz. The center-to-center distance of the two UHPs is set as ds=40 m. The cable length is assumed to be 100 m. The cables comprise decades of strands of galvanized high-strength steel wires, each 5.0 mm in diameter and 100 m in length. For ease of analysis, the total cable stiffness is chosen as [1, 2, 4]×106 N/m in the subsequent analyses. The specific parameters for the torsional vibration control analysis are shown in Table 2.

Influence of UHP mass and dimension

Several cases were analyzed to investigate the influence of UHP’s dimensions and mass on deck’s control effect, where Ap=[16, 20.25, 25] m2, and mp=[2: 0.5: 12]×103 kg.

For different Ap and mp, the corresponding ζ is shown in Fig. 5. It can be seen that: ① The control effect of UHP does not continually improve with increasing UHP mass for a specific Ap. As mp increases, the value of ζ first increases and then decreases, eventually stabilizing, showing little further change. ② The optimal ζ and the corresponding optimal mp increase with the increase of Ap. ③ The optimal mp follows a linear relationship with Ap3/2.

For different Ap and mp, the corresponding Fmax is shown in Fig. 6. It can be observed that for UHPs with the same Ap, Fmax changes slightly with mp, with the force being largest at the optimal mp that corresponds to the optimal ζ.

The reason for ζ with mp variation is analyzed based on the displacement time histories of the deck and the UHPs. The parameters directly related to the cable forces are the displacements at the left and right cable suspension points, yb1(t) and yb2(t), respectively. Where yb1(t)=-αb(t)×ds/2, yb2(t)=αb(t)×ds/2. The arrangement of the left-side and the right-side cable suspension points is shown in Fig. 1. As the two UHPs are arranged symmetrically around the deck’s longitudinal axis, their motion characteristics are identical. Only yb1(t) and yp1(t) are analyzed for simplicity.

Figure 7 shows the time histories of yb1(t) and yp1(t) for three mp conditions when Ap=25 m2; the cable is under tension when the dashed line is positioned below the solid line. Figure 8 presents the corresponding time histories of the left-side cable force. It can be observed that during the system’s motion, the cable experiences both slackening and tensioning states within each cycle. For different mp cases, the timing of the cable tensioning differs within each cycle.

For the case mp = 7.5 × 103 kg, the cable tensioning moments in each motion cycle occur are closest to the 3T/4 (T represents the deck’s motion period). This case exhibits the best control performance. For the mp = 3.5 × 103 kg case, cable tensioning occurs the latest in each motion cycle, with the smallest peak cable force and the worst control performance. For the mp = 10.5 × 103 kg case, the tensioning moments occur the earliest in each cycle, with the average control performance. In the first cycle, the maximum cable force is almost the same as the mp = 7.5 × 103 kg case. However, in the second cycle, the peak cable force is smaller, with the cable tensioning occurring much earlier.

The ζ of the mp = 7.5 × 103 kg case is the maximum, and the reason is as follows. The cable tensioning in each cycle almost occurs at 3T/4, when the cable suspension point moves upward fastest, while the UHP moves downward fastest. As a result, the velocity difference (Vdiff) between the cable suspension point and the UHP is maximized (Vdiff corresponding to the three mp cases are 2.27 m/s, 2.44 m/s, and 2.37 m/s, respectively), which leads to the maximum cable force and the highest energy dissipation by the UHP during each cable tensioning period.

This paper will analyze the variation characteristics of the moments when the cables transition from slack to tensioned state (tzji , where i = 1 or 2 represent the index of left and right-side cables, respectively) and the duration of tension (tdi). Figure 9 shows the displacement time histories of the UHPs and the cable suspension points under the optimal damping condition. When the dashed line is below the solid line, the cable is tensioned (highlighted area) in Fig. 9. The UHP motion includes: ① The UHP moves force-driven by the cable when the cable is under tension. ② The UHP freely falls in the water when the cable is slack. The figure shows that after T/2, tzji and tdi generally follow a specific pattern in each subsequent cycle, and the detailed expression formula will be provided later. If this pattern is consistent for all cases, it can serve as a basis for optimizing the UHP mass. For simplicity, the analysis will focus only on the first td1 and td2 in the following discussion.

Under the optimal damping condition, the relationship between tzji and tdi follows a specific pattern. To facilitate observation, tzji and tdi are normalized by T and 2T, respectively. For different Ap and mp, the corresponding tzji/T and tdi/2T are shown in Figs. 10 and 11, respectively. Red squares correspond to the optimal damping condition. It can be observed that the optimal mp generally corresponds to the relationships: td1/2 + tzj1=3T/4 and td2/2 + tzj2=5T/4. This pattern corresponds to the cable suspension point reaching its maximum upward velocity and the UHP reaching its maximum downward velocity, with the largest cable force and the highest energy dissipation. This pattern can serve as a criterion for determining the optimal UHP mass.

Influence of cable stiffness

Several cases were analyzed to investigate the influence of cable stiffness on deck’s control effect, where Kc=[1, 2, 4]×106 N/m and mp=[3: 0.5: 12]×103 kg.

For different Kc and mp, the corresponding ζ is shown in Fig. 12. It can be observed that, as mp increases, the value of ζ first increases, then decreases, and eventually stabilizes, with the stabilized value being close to the optimal ζ. Additionally, the optimal ζ and the optimal mp decrease with the increasing of Kc. When mp varies around the optimal value, the damping effect remains robust.

For different Kc and mp, the corresponding Fmax is shown in Fig. 13. It can be seen that Fmax increases with the increasing of Kc. However, for the same Kc, Fmax changes slightly with mp.

For different Kc and mp, the corresponding tzji/T and tdi/2T are shown in Figs. 14 and 15, respectively. It can be seen that: ① For the same Kc, td1 and td2 are almost identical. ② For each level of Kc, the optimal mp generally corresponds with the following relationships: td1/2 + tzj1=3T/4 and td2/2 + tzj2=5T/4, which can be used as a criterion for determining the optimal UHP mass.

Influence of the deck torsional amplitude

Several cases were selected to investigate the UHP’s control effectiveness on the deck, where α0=[1°: 2°: 5°], and mp=[3: 0.5: 12]×103 kg.

For different α0 and mp, the corresponding ζ is shown in Fig. 16. It can be observed that: ① the optimal ζ and the optimal mp increase with the increasing of the α0. ② As mp increases, ζ first increases, then decreases, and finally stabilizes, almost remaining unchanged. The larger the deck’s torsional amplitude, the closer the stabilized value of ζ is to the optimal ζ. ③ The optimal mp generally follows a linear relationship with α0.

For different α0 and mp, the corresponding Fmax is shown in Fig. 17. It can be observed that, Fmax increases with the increasing of α0. However, for the same α0, Fmax changes slightly with mp, The maximum cable force under the optimal mp case generally follows a linear relationship with α0.

For different α0 and mp, the corresponding tzji/T and tdi/2T are shown in Figs. 18 and 19, respectively. It can be seen that: ① For the same α0, td1 and td2 are almost identical. ② For each level of α0, the optimal mp generally corresponds with the following relationships: td1/2 + tzj1=3T/4 and td2/2 + tzj2=5T/4, which can be used as a criterion for determining the optimal UHP mass.

Influence of deck torsional frequency

Several cases were selected to investigate the control effectiveness of UHP on the deck, where fα=[0.1: 0.05: 0.25] Hz, and mp=[0. 5: 0.5: 20] ×103 kg.

For different fα and mp, the corresponding ζ is shown in Fig. 20. It can be observed that: ① As mp increases, ζ first increases, then decreases, and finally stabilizes. The smaller fα, the closer the stabilized value of ζ is to the optimal ζ. ② As fα increases, the sensitivity of ζ to fα decreases when mp is below the optimal UHP mass. ③ The optimal ζ increases with the increasing of fα.

For different fα and mp, the corresponding Fmax is shown in Fig. 21. It can be concluded that: ① Fmax increases with the increasing of fα. ② For the same fα, Fmax changes slightly with mp.

For different fα and mp, the corresponding tzji/T and tdi/2T are shown in Figs. 22 and 23, respectively. It can be observed that: For each level of fα, the optimal mp generally corresponds with the following relationships: td1/2 + tzj1=3T/4 and td2/2 + tzj2=5T/4, which can be used as a criterion for determining the optimal UHP mass.

Calculation methods for the main design parameters of the damping control system

The section "Parameter design method for UHPs and cables" presents a method for optimizing and selecting the parameters of the UHP and cables, where each parameter change requires calculating the optimal UHP mass, corresponding maximum cable force, and additional damping ratio. This process involves executing the calculation steps from the section "Calculation steps for deck-cable-UHP dynamics" repeatedly for each parameter change and selecting the optimal parameters based on the results. This parameter design method requires substantial computation and analysis, resulting in low efficiency. In this section, explicit formulas for calculating the UHP mass, maximum cable force, and additional damping ratio under optimal conditions were derived based on the induction and reasonable assumptions. These formulas can replace the response calculations of the deck-cables-UHPs system and parameter selection process (Steps 2–5) in the section "Parameter design method for UHPs and cables", which can significantly simplify the design process.

Additionally, in our calculation cases, the parameters of the rigid segmental deck—such as mass moment of inertia per unit length and vibration frequency—were selected with reference to those of long-span bridges. The deck length used in the simulations ranges from 50 m to 100 m. Based on these cases, the additional damping ratio induced by UHPs can be extrapolated to real bridges.

Specifically, if a UHP with area Ap, mass mp, is suspended on a rigid deck of length Lb, unit mass moment of inertia Jb, torsional amplitude Aα, and torsional frequency fα, and produces an additional damping ratio ζ, then under the same parameters, suspending n UHPs on a deck of length n×Lb yields the same additional damping ratio ζ. Similarly, for a 3D deck with equivalent mass and vibration frequency fα, if the n UHP are installed at locations with identical torsional amplitude Aα, the resulting additional damping ratio remains ζ. If the UHPs are installed at locations with varying vibration amplitudes, the additional damping ratio can be obtained by computing the mechanical energy dissipated by each UHP per cycle using the method or results presented in this paper (or by inversely estimating energy dissipation from known damping ratios). The total energy dissipated per cycle by all UHPs can then be used to derive the effective additional damping ratio of the 3D aeroelastic deck.

Induction and assumptions

Based on the previous analysis, it can be concluded that the optimal mp generally corresponds to the following relationships: td1/2 + tzj1=3T/4 and td2/2 + tzj2=5T/4. Since the tensioning moments and durations of the two side cables follow similar patterns, only the left-side cable is analyzed for simplicity in explanation and derivation.

For optimal control conditions, the two side cables are not tensioned simultaneously. During the one-side cable tensioning, the deck-cable-UHP system can be simplified as a two-oscillator spring system. The main parameters influencing the vibration period of the double-spring oscillator system include the moment of inertia of the deck (Jb), the equivalent mass of the UHP (mp + ρCmL3, mp can be neglected, since mp is much smaller compared to ρCmL3, shown as Fig. 24), and the cable stiffness (Kc). The drag force (Fd) acting on the UHP can be seen as a damping force related to its velocity. Generally, during cable tensioning, the UHP experiences significant acceleration, and its weight and the drag force acting on it are relatively small compared to its added mass force (Fm) (shown in Fig. 24, Fa represents the UHP’s inertial force). Therefore, the influence of Fd on calculating the cable tensioning duration can be neglected. Thus, Assumption 1 is made: During cable tensioning, the influence of UHP’s weight and drag force on calculating the vibration period of the deck-cable-UHP system.

Based on Assumption 1, the vibration period of the double oscillator spring system composed of the deck, cable, and UHP is given by: \({T_s}=2\pi \sqrt {\frac{{4{J_b} \cdot \rho {C_m}{L^3}d_{s}^{2}}}{{(4{J_b}+\rho {C_m}{L^3}d_{s}^{2}){K_c}}}}\). The duration of the cable tensioning is half of the vibration period of the double-oscillator spring system, which can be expressed as:

When the cable is relaxed, the UHP motion equation satisfies:

The UHP maximum downward velocity, i.e., vp_max, can be expressed as:

The vertical velocity and acceleration of the UHP before the cable tensioning in the first cycle under the optimal mp condition are shown in Fig. 25. It can be observed that the acceleration of the UHP approximately follows a linear variation over time. When the cable is tensioned, the acceleration of the UHP approaches zero, and its velocity is close to vp_max. Therefore, Assumption 2 is proposed: the acceleration of the UHP during its free fall in the water follows a linear variation. Within the time interval [0,tzj], the acceleration decreases from a vp_max to 0.

Since the duration of cable tensioning td is much shorter than the period of the deck, and the variation in deck velocity during this period is relatively small. Therefore, Assumption 3 is proposed: the velocity of the deck increases linearly over the interval [tzj-td/2, tzj], and decreases linearly over the interval [tzj, tzj+td/2].

Explicit formulas for the main design parameters of the damping control system

Based on Assumption 2 in the section "Induction and assumptions", the UHP’s acceleration during free fall in water varies linearly. The falling distance of the UHP within the time interval [0, tzj] can thus be calculated as:

Based on the equation of motion of the deck, the displacement of the UHP when the cable initially tightens can be expressed as:

where A is the torsional amplitude (in radians).

By combining Eqs. (19)–(20), the optimal UHP’s mass can be derived as:

where \(S=\frac{{A{d_s}}}{2}(1 - \cos (2\pi f \cdot {t_{zj}}))\).

Taking the cable suspension point as the reference system, the relative velocity of the UHP is vdiff=vb_s-vp_s when the cable begins to tighten, where vb_s is the velocity of the cable suspension point when the cable starts tightening (vb_s=-πfAdssin(2πftzj)). The cable force amplitude is calculated by:

In the motion of the two-oscillator spring system, the variation of cable force acting on the heave plate follows a sinusoidal curve. To compute the negative work done by the cable force on the deck, it is necessary to first determine the displacement of the deck over the interval [tzj-td/2, tzj+td]. Taking the suspension point of the cable as the reference frame, the velocity of the heave plate varies from vdiff to 0 during the interval [tzj-td/2, tzj], and from 0 to − vdiff during [tzj, tzj+td/2]. Accordingly, in the ground-fixed reference frame, the velocity of the heave plate varies from (vb_s-vdiff) to vb_m (vb_m denotes the velocity of the suspension point at time tzj) during [tzj, tzj+td/2], and from vb_m to (vb_e+vdiff) during [tzj, tzj+td/2], where vb_s and vdiff are known quantities.

According to Assumption 1, the external force acting on the two-oscillator spring system within the interval [tzj-td/2, tzj+td/2] is the restoring force of the deck, expressed as -Jb·(2πf)2α, where α is the torsional angle of the deck and αzj0 = Acos(2πftzj) denotes its value at tzj-td/2. According to Assumption 3, the total displacement of the deck is given by δα1 = - (vb_s+vb_m)·td/(2ds) during the interval [tzj, tzj+td/2], and byδα2 = - (vb_e+vb_m) ·td/(2ds) during the interval [tzj, tzj+td/2].

According to the principle of linear momentum, the system satisfies the following two equations over the intervals [tzj-td/2, tzj] and [tzj, tzj+td/2], respectively:

It follows that:

During the cable tensioning, the cable force equals the sum of the inertial force, net gravitational force (difference between gravitational and buoyant forces), added mass force, and drag force acting on the UHP.

The net gravitational force and the added mass force acting on the heave plate vary in a sinusoidal manner. Before the time tzj+td/2, the drag force is significantly smaller than the combined effect of the other two components (as shown in Fig. 24). Therefore, the contribution of drag force work is neglected during the interval [tzj, tzj+td/2], and only its work in the interval [tzj+td/2, tzj+td] is considered. Since td is much smaller than the period of the main beam, the velocity of the heaving plate in this interval is assumed to vary linearly from vb_m to vp_e (= vb_e+vdiff). The drag force work is then calculated using the average drag force, given by 1/6CdL2vp_e2.

In the following, only the deck mechanical energy consumed by the UHP during the first half of the cycle under optimal control conditions is calculated; the process is similar for subsequent cycles. The deck mechanical energy dissipated by the UHP during the cable tensioning period [3T/4-td/2, 3T/4 + td/2] is expressed as:

The damping ratio provided by the UHP can be calculated as follows:

where E0 = 2·Jb(πfA)2.

Validation of the formulas’ calculation accuracy

A comparison between the optimal parameters obtained from simulation calculations and those derived from the formulas in the section "Explicit formulas for the main design parameters of the damping control system" is shown in Fig. 26. “Simulation” represents the parameters selected from the simulation results, and “Formula” refers to the parameters derived from the calculation formulas in this section. The compared cases parameters are as follows: Jb=5 × 108 kg·m2, α0 = 5°, fα=0.2 Hz, K = 2 × 106 N/m, Ap=[16, 20.25, 25] m2. The following parameters under optimal conditions are compared: the surface density of the UHP ρp (mp/Ap), the ratio of the maximum cable force to the gravitational force of the UHP (F/mpg), and the damping ratio (ζ) provided by the UHP. As shown, the optimal parameters obtained from the formulas agree well with those selected from the simulation results. This demonstrates the high accuracy of the proposed formulas, and further validates the reasonableness of the assumptions in the section "Induction and assumptions".

Optimized parameters by using simulation and formulas: (a) ρp, with fα=0.2 Hz, α0 = 5°; (b) Fmax/mpg, with fα=0.2 Hz, α0 = 5°; (c) ζ, with fα=0.2 Hz, α0 = 5°; (d) ρp, with fα=0.2 Hz, α0 = 3°; (e) Fmax/mpg, with fα=0.2 Hz, α0 = 3°; (f) ζ, with fα=0.2 Hz, α0 = 3°; (g) ρp, with fα=0.1 Hz, α0 = 5°; (h) Fmax/mpg, with fα=0.1 Hz, α0 = 5°; (i) ζ, with fα=0.1 Hz, α0 = 5°; (j) ρp, with fα=0.1 Hz, α0 = 3°; (k) Fmax/mpg, with fα=0.1 Hz, α0 = 3°; (l) ζ, with fα=0.1 Hz, α0 = 3°.

Concluding remarks

This paper investigates the additional damping characteristics of the UHP for deck vibration control. A coupled motion analytical model of the rigid deck-cables-square UHP system was established, and detailed calculation steps for the system’s response under impulsive conditions were provided. A computational analysis program was developed based on the model. Experimental validation confirmed the accuracy of both the simulation model and the developed program, demonstrating that the program can accurately compute the motion responses of the deck and UHPs. This work offers a simple and efficient method for studying the additional damping characteristics of UHP for mitigating deck vibration and proposes an optimization design method for the UHP and cable parameters.

The simulation-based study investigated the control effects of the UHP’s dimensions, mass, and cable stiffness on the deck’s torsional vibration. The following findings were made: ① When the UHP’s area is the same, a larger UHP’s mass does not necessarily lead to a larger additional damping ratio of the deck. The additional damping ratio provided by the UHP initially increases with the mass, then decreases and eventually stabilizes, with the stabilized value closely approaching the optimal damping ratio. Therefore, in cases where the optimal mass of the UHP cannot be precisely determined, increasing the mass of the UHP provides a safer choice for the deck vibration control. ② As the deck’s torsional amplitude or frequency increases, the maximum additional damping ratio that the UHP can provide to the deck also increases. However, this comes with an increase in the corresponding mass of the UHP.

Based on analyzing many simulation results, it was found that the UHP optimal control condition corresponds to specific patterns between the cable tensioning time and duration. Based on the three assumptions from the section "Induction and assumptions", explicit formulas for calculating the UHP mass, maximum cable force, and additional damping ratio under optimal conditions were derived. A comparison revealed that the design parameters of the damping device obtained through the formula-based approach closely match those selected from simulation-based calculations. Therefore, the formula-based method can be applied to optimizing the UHP and cable parameters, significantly reducing the computational workload.

While this study does not allow simultaneous evaluation of multiple vibration modes and varying UHP installation positions, it offers a simplified and efficient means to analyze the energy dissipation mechanisms and characteristics of UHP. As long as the similarity relations are satisfied, the results obtained from rigid segmental deck can be reasonably extended to investigate the response of a full bridge. This approach facilitates the derivation of practical analytical expressions for UHP mass, cable force, and damping ratio. Specifically, the effectiveness of UHPs under three-dimensional aeroelastic conditions should be evaluated through advanced numerical simulations or experimental testing. Key factors such as the number of UHP, suspension locations, and the modal characteristics of the deck must be systematically investigated. Given the complexity and scope of such an analysis, it falls beyond the scope of the present work. This will constitute a primary focus of our subsequent research.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Zhang, Z. T., Yang, J. J. & Zeng, J. D. Structural countermeasures against aerodynamic torsional divergence of a suspension Bridge with a main span of 3 000 m. Int J. Struct. Stab. Dyn 2650029 (2024).

Li, M., Sun, Y., Lei, Y., Liao, H. L. & Li, M. S. Experimental study of the nonlinear torsional flutter of a Long-Span suspension Bridge with a Double-Deck truss girder. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 21 (07), 2150102 (2021).

Zhou, R. et al. Nonlinear behaviors of the flutter occurrences for a twin-box girder Bridge with passive countermeasures. J. Sound Vibr. 447, 221–235 (2019).

Mei, H., Wang, Q., Liao, H. & Fu, H. Improvement of flutter performance of a streamlined box girder by using an upper central stabilizer. J. Bridge Eng. 25 (9), 04020053 (2022).

Phan, D. H. Passive winglet control of flutter and buffeting responses of suspension bridges. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 1850072, 1–16 (2022).

Phan, D. H. Aeroelastic control of Bridge using active control surfaces: analytical and experiment study. Structures 27, 2309–2318 (2020).

Wu, S. Z. et al. Performance of different damping devices for mitigating Vortex-induced vibration of long span bridges: A comparative study. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2650137, 1–34 (2024).

Peng, S., Zhang, L., Liu, Y. & Li, S. Parameters optimization and performance evaluation of multiple tuned mass dampers to mitigate the vortex-induced vibration of a long-span Bridge. Structures 38, 1595–1606 (2022).

Pourzeynali, S. & Datta, T. Control of flutter of suspension Bridge deck using Tmd. Wind Struct. 5 (5), 407–422 (2022).

Dai, J., Xu, Z. D., Xu, W. P., Yan, X. & Chen, Z. Q. Multiple tuned mass damper control of vortex-induced vibration in bridges based on failure probability. Structures 43, 1807–1818 (2022).

Feng, Z., Jing, H., Wu, Q., Li, Y. & Hua, X. Performance evaluation of inerter-based dampers for Bridge flutter control: A comparative study. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 24 (06), 2450058: 1–22 (2022).

Chen, X., Xu, F., Qiu, W. & Zhang, Z. AMD application for suppressing the lateral and torsion buffeting response of suspension pipeline Bridge. Adv. Mater. Res. 163, 4114–4119 (2022).

Zhang, C. The active rotary inertia driver system for flutter vibration control of bridges and various promising applications. Sci. China-Technol Sci. 66 (2), 390–405 (2022).

Zhu, J., Jiang, S. J., Xiong, Z., Wu, M. & Li, Y. Longitudinal vibration control strategy for long-span suspension bridges under operational and extreme excitations using eddy current dampers. Structures 58, 105603 (2022).

Chen, X. & Kareem, A. Efficacy of tuned mass dampers for Bridge flutter control. J. Struct. Eng. 129 (10), 1291–1300 (2003).

Mao, T. Investigations on the performance of heave damping device for suppressing vibration of long-span bridges. Master Degree dissertation from Dalian University of Technology (2022). (in Chinese)

Li, Y. W., Qing, Q. Z. & Zhang, Z. T. Wind tunnel test of a new type of wind resistant underwater damping system. In The 20th National Conference on Bridges of China, Changsha City, Hunan Province, China. 2, 123–129 (2012).

An, W., Xu, F. & Wang, J. Experimental study on the performance of underwater heave plates for mitigating Bridge flutter. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219455426503360 (2025).

Tian, X., Tao, L., Li, X. & Yang, J. Hydrodynamic coefficients of oscillating flat plates at 0.15⩽ KC⩽ 3.15. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 22, 101–113 (2017).

Prislin, I. Viscous damping and added mass of solid square plates. In 17th Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering Conference, Lisbon, Portugal 1–7 (1998).

Tao, L. & Dray, D. Hydrodynamic performance of solid and porous heave plates. Ocean. eng. 35 (10), 1006–1014 (2008).

Wadhwa, H., Krishnamoorthy, B. & Thiagarajan, K. Variation of heave added mass and damping near seabed. In International conference on offshore mechanics and arctic engineering, Shanghai, P. R. China 49095, 271–277 (2010).

Li, J. et al. Experimental investigation of the hydrodynamic characteristics of heave plates using forced Oscillation. Ocean. Eng. 66, 82–91 (2010).

An, S. & Faltinsen, O. An experimental and numerical study of heave added mass and damping of horizontally submerged and perforated rectangular plates. J. Fluid Struct. 39, 87–101 (2013).

Lopez-Pavon, C. & Souto-Iglesias, A. Hydrodynamic coefficients and pressure loads on heave plates for semi- submersible floating offshore wind turbines: A comparative analysis using large scale models. Renew. Energy. 81, 864–881 (2015).

Medina-Manuel, A., Botia-Vera, E., Saettone, S., Calderon-Sanchez, J. & Bulian, G. Hydrodynamic coefficients from forced and decay heave motion tests of a scaled model of a column of a floating wind turbine equipped with a heave plate. Ocean. Eng. 252, 110985 (2022).

Hegde, P. & Nallayarasu, S. Investigation of heave damping characteristics of buoy form Spar with heave plate near the free surface using CFD validated by experiments. Ships Offshore Struct. 18 (12), 1650–1667 (2023).

Zhang, S. & Ishihara, T. Numerical study of hydrodynamic coefficients of multiple heave plates by large eddy simulations with volume of fluid method. Ocean. Eng. 163, 583–598 (2010).

Morison, J., Johnson, J. & Schaaf, S. The force exerted by surface waves on piles. J. Pet. Technol. 2 (05), 149–154 (1950).

Bearman, P., Downie, M., Graham, J. & Obasaju, E. D. Forces on cylinders in viscous oscillatory flow at low Keulegan- carpenter numbers. J. Fluid Mech. 154, 337–356 (1985).

Liu, I. H. & Oztekin, A. Three-dimensional transient flows past plates translating near a wall. Ocean. Eng. 159 (JUL.1), 9–21 (2018).

Garrido-Mendoza, C. A. et al. Numerical investigation of the flow features around heave plates oscillating close to a free surface or seabed. In International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering. American Society of Mechanical Engineers 45493, V007T12A014 (2014).

Funding

The presented research work was funded by the National Natural Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholar (Grant No. 52125805), which is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wanbo An: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation, Software, Visualization, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing & editing. Fuyou Xu: Conceptualization, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Writing & editing, Supervision.Miaomin Wang: Visualization, Data Curation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

An, W., Xu, F. & Wang, M. Simulation of the additional damping characteristics of underwater heave plates for mitigating long-span bridges vibration. Sci Rep 15, 44502 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28157-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28157-5