Abstract

This research investigates the analytical traveling wave solutions of Sasa-Satsuma equation in a new manner by involving beta, M-truncated and conformable derivatives. The extended generalized Riccati equation mapping (EGREM) method is employed to obtain exact solutions such as bright soliton, dark soliton, kink soliton, anti-kink soliton and periodic soliton solutions. A systematic dynamical analysis, including bifurcation behavior, chaotic evolution, and parameter sensitivity, discloses the roles of fractional order and medium properties in wave propagation and stability. The results show that every fractional operator produces unique memory-based physical effects with a significant influence on dispersion, pulse shaping, and nonlinear coupling. The outcomes improve the understanding of fractional nonlinear wave models and facilitate practical applications in nonlinear optics, plasma physics, and complex signal transmission systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The study of the behavior of nonlinear systems is a fundamental subject in contemporary mathematical physics since most natural phenomena show responses that cannot be modelled by linear systems. Wave propagation in nonlinear and dispersive media tends to produce coherent structures like solitons, shocks and rogue waves features that are best modelled using non-linear evolution equations (NLEEs). NLEEs are basic mathematical models to describe a broad variety of complex physical phenomena in many areas of science, such as fluid dynamics, plasma physics, biophysics, condensed matter physics and nonlinear optics1,2. These equations capture the fine interplay among dispersion, nonlinearity and dissipation that governs wave propagation in different media. Some of the most notable examples of NLEEs are the Korteweg-de Vries (KdV) equation3, nonlinear Schrödinger (NLS) equation4, Zakharov–Kuznetsov (ZK) equation5, Sine-Gordon equation6 and the Kundu-Eckhaus equation7. These models all have significant roles in understanding various wave behaviors. Owing to their application in modeling systems of the real world, much attention has been paid to finding exact solutions of NLEEs. These solutions have various applications in signal processing, optical communications and energy transport . There have been various analytical methods proposed to obtain traveling wave solutions over the years, such as the Bäcklund and Darboux transformations8, Hirota’s bilinear method9, the \((G^{\prime }/G)\)-expansion method10, Lie symmetry analysis11 and the sine-cosine method12.

The Sasa-Satsuma equation (SSE) is a higher-order generalization of the NLS and serves as a fundamental model for studying ultrashort pulse propagation in mono mode optical fibers. Unlike the standard NLS, the SSE incorporates third-order dispersion, self-steepening and delayed nonlinear response, making it more suitable for capturing realistic wave dynamics in nonlinear media. The SSE is given by:

where p(x, t) represents the slowly varying envelope of the electric field and the real constants correspond to third-order dispersion, self-steepening and stimulated Raman scattering, respectively. The SSE is commonly used in nonlinear optics to describe ultrafast optical pulses. It explains how solitons (steady wave pulses) distort and shift frequency because of effects such as Raman scattering and third-order dispersion. There are many applications of this model in fluid dynamics to model how water waves propagate in deep oceans, particularly when waves become steep or break. It is also useful in plasma physics, where it models the behavior of ion-acoustic waves under the influence of strong nonlinear effects, assisting researchers with wave turbulence and energy flow in plasmas13. Numerous approaches have been employed to find the solution of the SSE, such as the simplest equation method14 and the extended direct algebraic method15.

To better describe nonlocal and memory-dependent behavior in such systems, the classical SSE extended with the help of the methods of fractional calculus16. With the passage of time, fractional calculus has been shown to be an effective way of generalizing classical differential models to account for memory effects and non-local interactions. Several analytical methods have been applied to fractional models, including modified fractional sub-equation method17, fractional sine-cosine method19, fractional rational sinh-cosh function method20, the functional variable method21, improved F-expansion method22, modified extended direct algebraic method23, enhanced algebraic method24 and complete discrimination system for polynomials (CDSP)25. Fractional derivatives give a better description of systems where the past states influence the present behavior. For the examination of this equation, the EGREM method is utilized for building exact traveling wave solutions. This technique properly produces a diverse range of structures for waves, such as bright soliton, dark soliton, periodic waves soliton, kink soliton and anti kink soliton solutions. Among the available methods, this method has been a strong and powerful tool for obtaining exact traveling wave solutions of nonlinear fractional differential equations26. In this paper new forms of exact travelling wave solutions of the SSE by EGREM method are obtained. Further, a bifurcation analysis27 is performed to study the qualitative variations of the system’s dynamical behavior with respect to variation in important parameters. This involves determining critical transitions among various forms of wave solutions and identifying regions of parameter space where physically acceptable solutions exist. The findings of this research are valuable contribution to knowledge on nonlinear wave dynamics under fractional-order models. They also present a sound analytical structure which can be applied to other integrable and non-integrable systems in nonlinear optics, plasma physics and fluid dynamics.

The organization of this study is categorized into different sections. Section 2 is devoted to the necessary preliminaries. The governing models involving Beta, M-truncated and conformable derivatives with their transformation are given in Sect. 3. Section 4 is dedicated to the framework of the method utilized to obtain exact solutions of the SSE. In Sect. 5, the adoption of the method is carried out. Section 6 is dedicated to the graphical representation of the obtained solutions through 3D, 2D and contour plots to visualize the physical characteristics of the waves. Section 7 contains a bifurcation analysis to investigate the qualitative changes of the system dynamics under varying parameters. Section 8 is devoted to the discussion of the chaotic nature of the model and Sect. 8 contains a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of small parameter variations on the evolution of the system. Section 10 is dedicated to the physical significance and implications of the obtained solutions in practical applications. Finally, Section 11 briefly concludes the study by presenting the key results and suggesting possible avenues for future research.

Preliminaries

We have discussed some derivatives with their applications in this section. Numerous applications exist for the Beta, M-truncated, and conformable derivatives in the modeling of complex systems with memory and nonlocal dynamics. Because the beta derivative may capture memory effects with non-singular kernels, it is utilized in fractional differential equations to describe processes like dynamics of epidemics, and anomalous diffusion. The M-truncated derivative is a computationally simplified local approximation of fractional operators that is used in biological systems, engineering, and physics to more simply represent fluid flow, heat and mass transport, and the spread of epidemics. Whereas the Conformable derivative maintains the properties of classical calculus, it can be used to solve fractional models in domains such as population dynamics, control theory, signal processing, and economics, where fractional-order behavior affects system evolution while retaining analytical tractability.

Beta derivative

Definition 1

Let the function \(P: [0,\infty ) \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\). Then, the beta derivative28,29 of P(t) of order \(\beta\) is defined as:

Theorem 1

Suppose that \(P, Q: (0,\infty ) \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) are \(\beta\)-differentiable functions \(\forall\) \(t > 0\) and \(\beta \in (0,1]\), then they satisfy the following properties:

-

1.

\(D^{\beta }(g P(t) +a Q(t)) = g D^{\beta }(P(t)) + a D^{\beta }(Q(t)), \quad \forall\) \(g,a \in \mathbb {R}.\)

-

2.

\(D^{\beta }(P(t) Q(t)) = Q(t) D^{\beta }(P(t)) + P(t) D^{\beta }(Q(t)).\)

-

3.

\(D^{\beta }(P(t)) = \left( t + \frac{1}{\Gamma (\beta )} \right) ^{1-\beta } \frac{dP(t)}{dt}.\)

M-truncated derivative

Definition 2

Let the function \(w: [0, \infty ) \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) with order \(\Lambda \in\) (0, 1] be the M-truncated derivative (MTD) is defined as30

\(D_{j,t}^{\beta ,\Lambda }w(t)=\underset{h \rightarrow 0}{\lim }\ \frac{w\left( t\xi _{j, \Lambda }(h t^{-\beta })\right) - w(t)}{h}\),

where \(\xi _{j, \Lambda }(t)\) the truncated Mittag-Leffler function, is defined as follows for t \(\in\) C and \(\Lambda > 0\):

\(\xi _{j, \Lambda }(t)=\sum _{n=0}^{j} \frac{t^n}{\Gamma (\Lambda n + 1)}\).

The following properties of the MTD apply to any real integers f and e:

-

\(D_{j,t}^{\beta ,\Lambda }(ew+fu)=eD_{j,t}^{\beta ,\Lambda }(w)+fD_{j,t}^{\beta ,\Lambda }(u)\).

-

\(D_{j,t}^{\beta ,\Lambda }(wu)=uD_{j,t}^{\beta ,\Lambda }(w)+wD_{j,t}^{\beta ,\Lambda }(u)\).

-

\(D_{j,t}^{\beta ,\Lambda }w(t)=\frac{t^{1 - \beta }}{\Gamma (\Lambda + 1)} \frac{\textrm{d}w(t)}{\textrm{d}t}\).

-

\(D_{j,t}^{\beta ,\Lambda }(t^w)= \frac{w}{\Gamma (\Lambda + 1)} t^{w - \beta }\).

Conformable derivative

Let \(h(t):[0,+\infty ) \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) be a function. Then, the conformable fractional derivative31 of order \(\beta\) of h is given as:

Following properties hold for conformable derivative:

Theorem 2

Let the functions \(h_{1}=h_{1}(t)\) and \(h_{2}=h_{2}(t)\) be \(\beta\)-conformable differentiable at any point \(t>0\), \(\beta \in (0,1]\). Then, we have:

-

(i)

\(D_{t}^{\beta }(zh_{1}+bh_{2}) = z D_{t}^{\beta } h_{1} + b D_{t}^{\beta } h_{2}, \quad \forall z,b \in \mathbb {R}\).

-

(ii)

\(D_{t}^{\beta }(t^{n}) = n t^{\,n-\beta }, \quad \forall n \in \mathbb {R}\).

-

(iii)

\(D_{t}^{\beta }(z) = 0\), where z is any constant.

-

(iv)

\(D_{t}^{\beta }(h_{1}h_{2}) = h_{1}D_{t}^{\beta }h_{2} + h_{2}D_{t}^{\beta }h_{1}\).

-

(v)

\(D_{t}^{\beta }\!\left( \frac{h_{1}}{h_{2}}\right) = \dfrac{h_{2}D_{t}^{\beta }h_{1} - h_{1}D_{t}^{\beta }h_{2}}{h_{2}^{2}}\).

-

(vi)

If \(h_{1}\) is differentiable, then \(D_{t}^{\beta }(h_{1})(t) = t^{1-\beta } \dfrac{dh_{1}}{dt}\).

Governing models

This section deals with the representation of (1.1) in beta, M-truncated and conformable derivatives form and also deals with their transformations that are used to convert (1.1) into ordinary differential equation (ODE).

The sasa-satsuma equation involving beta derivative

The SSE with beta derivative is described as:

Following wave transformations for analytical solutions are considered as:

The sasa-satsuma equation involving M-truncated derivative

The SSE with M-truncated derivative is given by:

The following wave transformations are considered as:

The sasa-satsuma equation involving conformable derivative

The SSE with conformable derivative is defined as:

Following wave transformations are taken for analytical solutions:

Framework of the proposed method

Suppose the general nonlinear partial differential equation (PDE)

here \(p = p(x, t)\) denotes an unknown function and \(\Xi\) represents a polynomial in p(x, t). The subscripts refer to partial derivatives. The key steps of the EGREM method32 are outlined below:

Step 1: Consider the traveling wave transformation

The Eq. (4.1) is transformed into an ODE by applying Eq. (4.2), as follows:

Step 2: Each of the term in Eq. (4.3) is integrated separately, in some cases even several times, leading to integration constants which, for simplicity, are set to zero.

Step 3: Assume the traveling wave solution to Eq.(4.3) is

where \(A_m ( m = 0, 1, 2, \ldots , n)\) and \(A_n \ne 0\), with \(G = G(\xi )\) being the solution of the generalized Ricatti equation given as:

where \(\rho\), \(\delta\), and \(\lambda\) are constants, with the condition \(\lambda \ne 0\).

Step 4: The value of the positive integer n is determined by balancing the highest-order derivative with the nonlinear terms in Eq. (4.3).

Step 5: By substituting Eq. (4.4) together with Eq. (4.5) into Eq. (4.3), and then collecting terms with identical orders, the left-hand side of Eq. (4.3) is transformed into a polynomial in powers of \(G^j(\xi )\) and \(G^{-j}(\xi )\), where \(j = 0, 1, 2, \ldots\). Setting each coefficient of these polynomials to zero results in a system of algebraic equations involving the unknown parameters \(A_j\) \((j = 0, 1, 2, \ldots , n)\), \(\rho\), \(\delta\), \(\lambda\), and others.

Step 6: By making the substitutions \(A_0,A_1,A_2.......A_j\), k and the general solution of Eq. (4.5) into Eq. (4.4), the travelling wave solution of Eq. (4.1) is achieved. Twenty-seven different solutions to the generalized Riccati equation are given below, grouped in four families:

Family 1: When \(\mu = \sqrt{\delta ^2 - 4\lambda \rho }\), \(\mu ^2 > 0\) and \(\delta \lambda \ne 0\) or \(\lambda \rho \ne 0\), the hyperbolic solutions to Eq. (4.5) are:

The F and S are two non zero real constants where \(S^2-F^2>0.\)

Family 2: When \(\nu = \sqrt{4\lambda \rho - \delta ^2}\), \(\nu ^2 >0\) and \(\delta \lambda \ne 0\) or \(\lambda \rho \ne 0\), the trigonometric solutions to Eq.(4.5) are:

The F and S are two non zero real constants where \(F^2-S^2>0\).

Family 3: When \(\rho = 0\), \(\delta \lambda \ne 0\) and \(g_1\) is an arbitrary constant, then we have more solutions to Eq.(4.5):

Family 4: When \(\rho = \delta = 0\), \(\lambda \ne 0\) and \(e_1\) is an arbitrary constant, then the rational solutions to Eq.(4.5) are:

Application of the proposed method

The transformations given in Eq.(3.2), Eq.(3.4) and Eq.(3.6) are used for derivation of soliton solutions. After substituting concerned transformations in Eq.(3.1), Eq.(3.3) and Eq.(3.5), yield the same following real and imaginary parts of ODE in Eqs. (5.1) and (5.2), respectively.

and

From above Eqs.(5.1) and (5.2), the condition for consistency of these two equations is:

which gives:

Taking the homogeneous balance between \(q^3\) and \(q''\) in Eq.(5.1), provides \(n = 1\). Hence, the solution of Eq. (5.1) takes the form:

with \(G' = \rho + \delta G + \lambda G^2\), \(\lambda \ne 0\).

By substituting value of k given above and Eq.(5.3) into Eq.(5.1), collecting all coefficients of \(G^m\) \(( m = 0,1,2,\ldots )\) and equating the coefficients to zero leads to a new set of algebraic equations involving \(A_0\), \(A_1\), \(\rho\), \(\delta\), and \(\lambda\) (omitted here for brevity). Solving the obtained system with the aid of mathematica provides the following values

By inserting the solution of the nonlinear algebraic equation and general solution of the generalized Riccati equation into equation (5.3), different travelling wave solutions in different families of the SSE are derived.

Family 1: When \(\mu = \sqrt{\delta ^2 - 4\lambda \rho }\), \(\mu ^2 > 0\) and \(\delta \lambda \ne 0\) or \(\lambda \rho \ne 0\), the hyperbolic solutions to Eq.(3.1) are:

where F and S are two non-zero real constants with \(S^2-F^2>0\).

Family 2: When \(\nu = \sqrt{4\lambda \rho - \delta ^2}\), \(\nu ^2 >0\) and \(\delta \lambda \ne 0\) or \(\lambda \rho \ne 0\), the trigonometric solutions to Eq.(3.1) are:

where F and S are two non zero real constants with \(F^2-S^2>0\).

Family 3: When \(\rho = 0\), \(\delta \lambda \ne 0\) and \(g_1\) is an arbitrary constant, then we have more solutions to Eq.(3.1):

Family 4: When \(\rho = \delta = 0\), \(\lambda \ne 0\) and \(d_1\) is an arbitrary constant, then the rational solutions to Eq.(3.1) are:

where

Graphical illustration

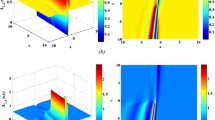

This part provides the 3D, 2D and contour profiles of the precise solutions of the SSE. The graphical representations are important sources of information about the physical behavior and dynamic nature of the derived soliton solutions. Similar structural patterned graphs are not included to prevent duplication. Nonlinear PDEs often occur in applied mathematics, physics, engineering and other scientific fields to model complicated physical phenomena. Therefore, calculation and analysis of their exact solutions are essential to grasp their physical implications. For the investigation of physical characteristics of the obtained solutions, graphical representations are employed.

In Fig. 1 the dark soliton solution of Eq.(5.4) is illustrated by way of 3D, 2D profile (fractional derivative impact) for different parameter values i.e \(\sigma = 1,\ \delta = 2.5,\ \lambda = 1,\ \rho = 1,\ \alpha = 0.5,\ \theta = -1,\ \tau = 3,\ c = 1,\ \beta = \frac{1}{2},\ \epsilon = 0.2\).

In Fig. 2 the bright soliton solution of Eq.(5.6) is illustrated by way of 3D, 2D profile (fractional derivative impact) and contour plot for different parameter values i.e \(\sigma = 1,\ \delta = 4,\ \lambda = 1,\ \rho = 1,\ \alpha = 1,\ \theta = 1,\ \tau = 1,\ c = 0.5,\ \beta = \frac{1}{2},\ \epsilon = 0.2\).

In Fig. 3 the periodic wave solution of Eq.(5.9) is illustrated by way of 3D, 2D profile (fractional derivative impact) and contour plot for different parameter values i.e \(\sigma = -0.12,\ \delta = 3,\ \lambda = -15,\ \rho = 1.4,\ \alpha = -0.91,\ \theta = 1,\ \tau = -12.2,\ c = 5.3,\ \beta =0.41,\ \epsilon = 1,\ S=1,\ F=0.5\).

In Fig. 4 the W-shaped soliton solution of Eq.(5.11) is illustrated by way of 3D, 2D profile (fractional derivative impact) and contour plot for different parameter values i.e \(\sigma = 1,\ \delta = 2,\ \lambda = 0.8,\ \rho = 1,\ \alpha = 1.5,\ \theta = 0.2,\ \tau = -1,\ c = -2,\ \beta = 0.95,\ \epsilon = 0\).

In Fig. 5 the kink-type solution of Eq.(5.28) is illustrated by way of 3D, 2D profile (fractional derivative impact) and contour plot for different parameter values i.e \(\sigma = 3,\ \delta = 2.5,\ \lambda = -1,\ \rho = 0,\ \alpha = 0.01,\ \theta = 1,\ \tau = 2,\ c = 1,\ \beta = 0.53,\ \epsilon = 1,\ g_1=1.2\).

In Fig. 6 the anti-kink type solution of Eq.(5.29) is illustrated by way of 3D, 2D profile (fractional derivative impact) and contour plot for different parameter values i.e \(\sigma = 2,\ \delta = 5,\ \lambda = 1,\ \rho = 0,\ \alpha = 0.11,\ \theta = 2,\ \tau = 5,\ c = 0.3,\ \beta = \frac{1}{2},\ \epsilon = 0.5,\ g_1=2\).

These plots bring out the heterogeneous solution structure and the localized nature of the obtained solutions.

The dark soliton solution of Eq.(5.4) is illustrated in the form of 3D surface, 2D profile (fractional derivative impact) and contour representation for different parameter values i.e \(\sigma = 1,\ \delta = 2.5,\ \lambda = 1,\ \rho = 1,\ \alpha = 0.5,\ \theta = -1,\ \tau = 3,\ c = 1,\ \beta = \frac{1}{2}\), and \(\epsilon = 0.2\).

The bright soliton solution of Eq.(5.6) is illustrated in the form of 3D surface, 2D profile (fractional derivative impact) and contour representation for different parameter values i.e \(\sigma = 1,\ \delta = 4,\ \lambda = 1,\ \rho = 1,\ \alpha = 1,\ \theta = 1,\ \tau = 1,\ c = 0.5,\ \beta = \frac{1}{2}\), and \(\epsilon = 0.2\).

The periodic wave solution of Eq.(5.9) is illustrated in the form of 3D surface, 2D profile (fractional derivative impact) and contour representation for different parameter values i.e \(\sigma = -0.12,\ \delta = 3,\ \lambda = -15,\ \rho = 1.4,\ \alpha = -0.91,\ \theta = 1,\ \tau = -12.2,\ c = 5.3,\ \beta =0.41,\ \epsilon = 1,\ S=1\), and \(F=0.5\).

The W-shaped soliton solution of Eq.(5.11) is illustrated in the form of 3D surface, 2D profile (fractional derivative impact) and contour representation for different parameter values i.e \(\sigma = 1,\ \delta = 2,\ \lambda = 0.8,\ \rho = 1,\ \alpha = 1.5,\ \theta = 0.2,\ \tau = -1,\ c = -2,\ \beta = 0.95\), and \(\epsilon = 0\).

The kink-type solution of Eq.(5.28) is illustrated in the form of 3D surface, 2D profile (fractional derivative impact) and contour representation for different parameter values i.e \(\sigma = 3,\ \delta = 2.5,\ \lambda = -1,\ \rho = 0,\ \alpha = 0.01,\ \theta = 1,\ \tau = 2,\ c = 1,\ \beta = 0.53\), and \(\epsilon = 1\), and \(g_1=1.2\).

The anti-kink type solution of Eq.(5.29) is illustrated in the form of 3D surface, 2D profile (fractional derivative impact) and contour representation for different parameter values i.e \(\sigma = 2,\ \delta = 5,\ \lambda = 1,\ \rho = 0,\ \alpha = 0.11,\ \theta = 2,\ \tau = 5,\ c = 0.3,\ \beta = \frac{1}{2}\), and \(\epsilon = 0.5\), and \(g_1=2\).

Phase portraits’ bifurcation

This section shows the bifurcation analysis of the time fraction SSE. Bifurcation analysis is applied to investigate how the system behavior changes as some of the parameters vary. It determines significant parameter values at which the solution type changes e.g, from the periodic to chaotic behavior or the appearance of soliton-like structures. This technique is useful in deriving significant information concerning the stability, existence and classification of various types of solutions, which are significant in the analysis of the physical processes included in the model. For bifurcation points Eq (5.1) can be written as:

The Galilean transformation is now applied to Eq.(7.1) in the following form:

\(V_1=\frac{(k \tau + \gamma )}{(3\sigma k + \alpha )},\qquad V_2=\frac{(d+\sigma k^3 + \alpha k^2 )}{(3\sigma k + \alpha )},\)

where h is hamiltonian constant.

For Eq.(7.3) the obtained equillibrium points are \((0,0),(\sqrt{\frac{V_2}{V_1}},0)\), and \((-\sqrt{\frac{V_2}{V_1}},0)\).

The determinant of Jacobian matrix for Eq. (7.3) is:

\(R(q, \phi ) = \begin{vmatrix} 0&1 \\ -3q^2V_1+V_2&0 \end{vmatrix}=3q^2V_1-V_2\).

Hence:

-

If \(R(q,\phi )>0\) then (q, 0)is a center point.

-

If \(R(q,\phi )<0\) then (q, 0)is a saddle point.

-

If \(R(q,\phi )=0\) then (q, 0)is a cuspidal point.

The following are potential results based on provided factors:

Case 1:

For \(V_1 > 0\) and \(V_2 > 0\), and under these parameter conditions, \(\sigma = 1, \; \gamma = 1, \; \tau =4, \; \theta = -1, \; \alpha = -2, \; d = -10.34 \;\) and \(\; k = -1.2\), there are three equilibrium points for Eq. (7.2). It can be seen in Fig. 7(a) that (0, 0) is a center point, while \((-2, 0)\) and (2, 0) show saddle-like behavior.

Case 2:

For \(V_1 < 0\) and \(V_2 < 0\), and under these parameter conditions, \(\sigma = -1, \; \gamma = 1, \; \tau =2, \; \theta = 3, \; \alpha = -1, \; d = 4.096\;\) and \(\; \quad k = -0.28\), there are three equilibrium points for Eq. (7.2). It can be seen in Fig. 7(b) that (0, 0) is a saddle point, while \((-2, 0)\) and (2, 0) show center-like behavior.

Case 3:

For \(V_1 < 0\) and \(V_2 > 0\), and under these parameter conditions, \(\sigma = 1, \; \gamma = -1, \; \tau =1, \; \theta = -2, \; \alpha = -1, \; d = 2.1 \;\) and \(\; k = 0.5\), there are three equilibrium points for Eq. (7.2). It can be seen in Fig. 7(c) that (0, 0) is a center point.

Case 4:

For \(V_1 > 0\) and \(V_2 < 0\), and under these parameter conditions, \(\sigma = 1, \; \gamma = 1, \; \tau =4, \; \theta = -1, \; \alpha = -2, \; d = 8 \;\) and \(\; k = -1.2\), there are three equilibrium points for Eq. (7.2). It can be seen in Fig. 7(d) that (0, 0) is a saddle point.

The phase portrait of the Eq.(7.2).

To enrich the bifurcation analysis, all phase portraits have been enhanced to explicitly mark the equilibrium points and to plot the separatrices passing through saddle points. These separatrices divide the phase plane into dynamically distinct regions and provide a clear geometric interpretation of the corresponding traveling-wave solutions.

In this framework, homoclinic orbits, which originate from and return to the same saddle point, represent localized bright or dark solitons whose amplitudes decay to identical asymptotic values. Conversely, heteroclinic orbits, which connect two distinct saddle points, correspond to kink and anti-kink solitons, where the field transitions between two different equilibrium states. The center-type points are associated with periodic or oscillatory wave structures.

The phase portraits Fig. 7 therefore depict a direct correspondence between the phase-space topology and the analytical soliton families obtained via the EGREM method. This visual correspondence reinforces the physical interpretation of the bifurcation dynamics and confirms the coexistence of bright, dark, kink, and anti-kink wave structures under different parameter regimes.

Chaotic behaviour

This part discusses the chaotic behavior33 of the given modified system:

\(\psi\) is the vibration frequency and M indicates the intensity of external disturbances on the system. Figure 8 illustrates the behavior of the system by the following parameters, given as \(\sigma = 1, \; \gamma = 1, \; \tau =4, \; \theta = -1, \; \alpha = -2, \; d = 8 \; k = -1.2,\;M=0.1\;\) and \(\;\psi =2\). In these conditions, the system is stable and its motion regular and predictable. That is to say, at low frequencies and under slight disturbances, the system has an orderly structure and never behaves chaotically.

Figure 9 illustrates what occurs when the strength of the disturbance M is raised slightly to 3. With only this small adjustment, the system starts to act chaotically. This demonstrates how a small adjustment in parameters can have a large effect on the behavior of the system.

Figure 10 illustrates another example, where the frequency \(\psi\) is raised to 10. That too results in chaotic behavior in the system. The irregular and unpredictable nature of the patterns evident in the figures are characteristic of nonlinear systems, in which slight changes result in very intricate outcomes. In general, these numbers indicate the sensitivity of the system to the outside parameters such as frequency and disturbance power. The minute changes in these parameters are enough to drive the system from a stable to a chaotic state, illustrating the sensitive balance and intricacies of nonlinear dynamic systems.

Chaotic Phase portrait for Eq.(8.1) when \(M=0.1\; and\; \psi =2\).

Chaotic Phase portrait for Eq.(8.1) when \(M=3\; and\; \psi =2\pi\).

Chaotic Phase portrait for Eq.(8.1) when \(M=3\; and\; \psi =10\).

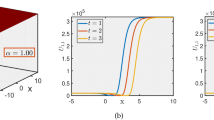

Analysis of dependence on initial conditions and parametric sensitivity

This section first investigates the dependence of the unperturbed system Eq.(7.2) on different initial conditions, highlighting how small variations in initial states affect the system trajectory (orbital stability). Additionally, to perform a true parametric sensitivity analysis, the perturbed system Eq.(8.1) is examined numerically to determine how minor changes in fractional order \(\beta\), nonlinear coefficient \(\gamma\), and perturbation strength M affect the system’s amplitude and energy.

This kind of analysis is crucial to enhance the accuracy and robustness of mathematical models. It facilitates effective decision-making by noting what parameters play a major role in affecting the system. An application of the Runge-Kutta method enables accurate numerical estimation, thus making it simpler to test how stable and reliable the model is when conditions change. Two- and three solution curves are analyzed and compared, as illustrated in Figs. 11, 12, 13, 14, using different parameter values of \(\sigma = 1, \; \gamma = 1, \; \tau =4, \; \theta = -1, \; \alpha = -2, \; d = 8 \; {and} \;k = -1.2\). In Fig. 11, two solutions are shown: \((q(0), \phi (0))= (0.7, 0.2)\) represented by the red line, and \((q, \phi )= (0.7, 1.5)\) represented by the green line. In Fig. 12, two solutions are again presented: \((q(0), \phi (0))= (0.7, 0.1)\) in blue and \((q(0), \phi (0))= (0.9, 0.3)\) in green. In Fig. 13, two solutions are again presented: \((q(0), \phi (0))= (0.9, 0.9)\) in blue and \((q(0), \phi (0))= (0.6, 0.3)\) in red.Similarly, Figure 14 displays three solutions: \((q(0), \phi (0))= (0.7, 0.8)\) in blue, \((q(0), \phi (0))= (0.5, 0.3)\) in red and \((q(0), \phi (0))= (0.3, 0.1)\) in green. Sensitivity analysis is important for enhancing the reliability, resilience and efficacy of models in various disciplines. By analyzing the impact of changes in input parameters on model results, researchers can minimize risks, make more informed decisions and increase the precision of predictions.

Behaviour of Eq.(7.2) with the parameters \(\sigma = 1, \; \gamma = 1, \; \tau =4, \; \theta = -1, \; \alpha = -2, \; d = 8 \;\) and \(\;k = -1.2\) , with initial values (0.7, 0.2) in red and (0.7, 1.5) in green.

Behaviour of Eq.(7.2) with the parameters \(\sigma = 1, \; \gamma = 1, \; \tau =4, \; \theta = -1, \; \alpha = -2, \; d = 8 \;\) and \(\;k = -1.2\) , with initial values (0.7, 0.1) in blue and (0.9, 0.3) in green.

Behaviour of Eq.(7.2) with the parameters \(\sigma = 1, \; \gamma = 1, \; \tau =4, \; \theta = -1, \; \alpha = -2, \; d = 8 \;\) and \(\;k = -1.2\) , with initial values (0.9, 0.9) in blue and (0.6, 0.3) in red.

Behaviour of Eq.(7.2) with the parameters \(\sigma = 1, \; \gamma = 1, \; \tau =4, \; \theta = -1, \; \alpha = -2, \; d = 8 \;\) and \(\;k = -1.2\) , with initial values (0.7, 0.8) in blue, (0.5, 0.3) in red and (0.3, 0.1) in green.

To further illustrate the system’s parameter sensitivity, Eq.(8.1) was numerically integrated using the fourth-order Runge–Kutta method for slightly varied parameter values (e.g., \(\beta\) = 0.5 ± 0.01, \(\gamma\) = 1 ± 0.05, M = 0.1 ± 0.01). The results indicate that even small perturbations in these parameters significantly influence the oscillation amplitude and energy of the system, confirming its sensitivity to external and fractional effects. This demonstrates that the fractional Sasa–Satsuma system exhibits both sensitivity to initial conditions (intrinsic nonlinear dynamics) and sensitivity to parameter variations (external perturbations).

Physical significance

The fractioanl term determines the memory-dependent temporal evolution, allowing the system to display fractional-order dynamics. This is an indication of a nonlocal-in-time response, which is essential when describing complex physical systems, e.g., viscoelastic optical fibers or biologic media.

The three fractional derivatives studied in this work, the beta, M-truncated and conformable derivatives, which represent different physical interpretations of memory and relaxation effects in nonlinear media. Though they generate the same mathematical forms of the time-fractional SSE but their physical mechanisms are different and account for different kinds of medium responses.

The conformable derivative is a local operator, meaning that the present state of the system mainly depends on its current value. It describes media with short-time or instantaneous relaxation where memory effects vanish quickly. In optics, this derivative can be used to model propagation of ultrashort pulses in weakly nonlocal media, generating more localized and sharper soliton structures.

The M-truncated derivative gives a partially non-local account of the system. It creates a finite memory effect, in which the system remembers its proximate history. This is a behavior corresponding to materials having truncated or restricted relaxation kernels, for example, some plasmas or viscoelastic optical fibers, in which the effects of previous states reduce gradually but never become zero instantaneously. Thus, it simulates intermediate dynamics between local and strongly nonlocal responses.

The Beta derivative is completely non-local operator which accounts for long-time memory behavior under the control of a power-law kernel. Here, all previous states affect the current behavior and therefore is a good choice for modeling complex media whose response is conditioned on a broad history of past excitations, including photonic crystal fibers, biological tissues, or non-Newtonian fluids. It is well-suited to describe slow relaxation and hereditary behavior characteristic of systems with power-law time correlations. A comparison of the physical characteristics of the three fractional derivatives in the time-fractional SSE is given in Table 1.

Fractional SSE is an integrable nonlinear higher-order evolution equation that generalizes the standard NLS model by including higher-order dispersion, nonlinear effects, and fractional time dynamics. The equation was originally proposed to model ultrashort optical pulse propagation in nonlinear media, namely, in the scenario where third-order dispersion, self-steepening, and stimulated Raman scattering are of special interest. In the updated variant, the equation includes a time-fractional derivative, enabling it to successfully model wave evolution in non-Markovian environments, where memory effects and long-time correlations play an essential role. Every term introduced in Eq.(3.1) captures essential features of nonlinear wave motion:

The dispersive term \(\alpha p_{xx}\) characterizes group velocity dispersion, which governs the tendency of the pulse to widen or narrow while propagating in the medium.

The cubic nonlinear term \(\gamma |p|^2 p\) creates a Kerr-type nonlinearity, which is at the center of the self-focusing or self-phase modulation phenomenon of the wave envelope.

The notation \(i \sigma p_{xxx}\) represents third-order dispersion , which affects the asymmetry and chirp of the pulse, particularly in ultrashort pulse regimes.

The nonlinear derivative terms \(i \tau |p|^2 p_x\) and \(i \theta p (|p|^2)_x\) represent self-steepening and stimulated Raman scattering, respectively. These effects cause spectral broadening, temporal pulse distortion, and nonlinear frequency shifting, all important in real optical systems.

With the help of advanced analytical techniques like EGREM method, several classes of soliton solutions have been derived, that is, bright, dark, periodic, kink and anti kink-type solitons. The SSE soliton solutions have immediate applications in optical communication, mechanical waves and other fields:

-

Bright solitons, with single, localized pulses, play a pivotal role in optical communications, enabling high-speed transmission of data over long distances with low distortion.

-

Dark solitons, as dips in an underlying continuous wave, are important for the investigation of nonlinear excitations in quantum fluids and Bose-Einstein condensates.

-

Periodic solitons explain periodic wave trains and can be used to model nonlinear lattice patterns, photonic crystals, and fiber lasers.

-

Kink solitons, or sharp transitions from one state to another, are applied in ferromagnetic domain walls, neural signal transmission, and phase-change materials.

Besides their exciting mathematical and physical significance, these soliton solutions find important implications in technological developments. Bright and dark solitons are crucial for the construction of all-optical switching devices, compressors for neuromorphic circuits, and nonlinear signal processors. Anti kink and kink solitons are utilized in magnetic data storage, neuromorphic circuits, and nonlinear control systems. These practical applications highlight the significance of the time fractional SSE in addressing contemporary scientific and engineering problems, especially those incorporating nonlinear dynamics, memory effects, and wave-based computation.

Conclusion

This study analyzed the time-fractional Sasa-Satsuma equation with the three fractional derivative impact. The EGREMM was employed to find exact bright, dark, kink, anti-kink and periodic wave solutions. Bifurcation analysis showed the influence of parameter variation on the wave forms. Chaotic behavior analysis at the same time showed sensitivity to initial conditions. The results show that the fractional order has a great influence on the solution behavior. This may be important in nonlinear optics, quantum systems and other fields.

Future work will expand this study by conducting thorough parameter scans and stability analysis in order to underline the distinct physical effects of these fractional derivatives. Such studies may investigate how each derivative affects soliton stability, energy localization and transitions between regular and chaotic behavior. Realistic systems, like photonic crystal fibers or nonlinear plasmas with memory, can also be considered within such a model.

Multi-soliton interactions or higher-order fractional models may further enhance the knowledge of the complex wave phenomena involved. The extended sensitivity analysis revealed that the system exhibits not only dependence on initial conditions but also significant sensitivity to small variations in key parameters such as the fractional order, nonlinear coefficient, and perturbation strength, confirming the intricate parametric responsiveness of the fractional SSE. Such efforts will also bridge the theoretical results with practical applications in nonlinear optics and plasma physics.

.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript.

References

Rosales, R. R. Exact solutions of some nonlinear evolution equations. Stud. Appl. Math. 59(2), 117–151 (1978).

Ablowitz, M. J. & Haberman, R. Nonlinear evolution equations-two and three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 35(18), 1185 (1975).

Kumar, S. & Malik, S. A new analytic approach and its application to new generalized Korteweg-de Vries and modified Korteweg-de Vries equations. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 47(14), 11709–11726 (2024).

Khatun, M. A., Arefin, M. A., Akbar, M. A. & Uddin, M. H. Existence and uniqueness solution analysis of time-fractional unstable nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Res. Phys. 57, 107363 (2024).

Ali, K. K. & Mehanna, M. S. Computational and analytical solutions to modified Zakharov-Kuznetsov model with stability analysis via efficient techniques. Opt. Quant. Electron. 53(12), 723 (2021).

Sadiya, U., Inc, M., Arefin, M. A. & Uddin, M. H. Consistent travelling waves solutions to the non-linear time fractional Klein-Gordon and Sine-Gordon equations through extended tanh-function approach. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 16(1), 594–607 (2022).

Hussain, E., Tedjani, A. H., Farooq, K. & Beenish. Modeling and Exploration of Localized Wave Phenomena in Optical Fibers Using the Generalized Kundu-Eckhaus Equation for Femtosecond Pulse Transmission. Axioms14(7), 513 (2025).

Pal, N. K., Nasipuri, S., Chatterjee, P. & Raut, S. Bilinear Bäcklund transformation, Lax pair, Darboux transformation, multi-soliton, periodic wave, complexiton, higher-order breather and rogue wave for geophysical Boussinesq equation. Pramana 98(3), 110 (2024).

Alquran, M. & Alhami, R. Analysis of lumps, single-stripe, breather-wave, and two-wave solutions to the generalized perturbed-KdV equation by means of Hirota’s bilinear method. Nonlinear Dyn. 109(3), 1985–1992 (2022).

Durur, H. Different types analytic solutions of the (1+ 1)-dimensional resonant nonlinear Schrödinger’s equation using \((G^{\prime }/G)\)-expansion method. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 34(03), 2050036 (2020).

Zhao, Z. & He, L. Lie symmetry, nonlocal symmetry analysis, and interaction of solutions of a (2+ 1)-dimensional KdV–mKdV equation. Theor. Math. Phys. 206(2), 142–162 (2021).

Mahak, N. & Akram, G. Exact solitary wave solutions by extended rational sine-cosine and extended rational sinh-cosh techniques. Phys. Scr. 94(11), 115212 (2019).

Gao, X. Y. Symbolic computation on a (2+ 1)-dimensional generalized nonlinear evolution system in fluid dynamics, plasma physics, nonlinear optics and quantum mechanics. Qualitative Theory Dynamical Syst. 23(5), 202 (2024).

Sadaf, M., Arshed, S., Akram, G., Shadab, H. & Alzaidi, A. S. Traveling wave dynamics of the generalized Sasa-Satsuma equation by two integrating schemes. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(2), 209 (2024).

Shafique, T., Abbas, M., Hamed, Y. S., Iqbal, M. K. & Aljohani, A. F. Study on the fractional Sasa-Satsuma equation of optical solitons in optical fibers and telecommunications. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(10), 1650 (2024).

Joshi, M., Bhosale, S. & Vyawahare, V. A. A survey of fractional calculus applications in artificial neural networks. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56(11), 13897–13950 (2023).

Wang, K. L. Dynamical analysis of the soliton solutions for the nonlinear fractional Akbota equation. Fractals. (2025).

Wei, C. F. & Wang, K. L. Construction of novel soliton solutions for the fractional chiral nonlinear Schrodinger equation. Fractals. (2025).

Wang, K. L. New Perspective to the Coupled Fractional Nonlinear Schrödinger Equations in Dual-Core Optical Fibers. Fractals 33(05), 2550034 (2025).

Wang, K. L. & Wei, C. F. Novel optical soliton solutions to nonlinear paraxial wave model. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 39(12), 2450469 (2025).

Wang, K. L. New dynamical behaviors and soliton solutions of the coupled nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Int. J. Geometric Methods Modern Phys. 22(8), 2550047–692 (2025).

Akbar, M. A., Abdullah, F. A. & Khatun, M. M. Analytical soliton solutions of time-fractional higher-order Sasa-Satsuma equations: nonlinear optics and beyond and the impact of fractional-order derivative. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(2), 227 (2024).

Han, T., Jiang, Y. & Fan, H. Exploring shallow water wave phenomena: A fractional approach to the Whitham-Broer-Kaup-Boussinesq-Kupershmidt system. Ain Shams Eng. J. 16(11), 103700 (2025).

Han, T., Liang, Y. & Fan, W. Dynamics and soliton solutions of the perturbed Schrödinger-Hirota equation with cubic-quintic-septic nonlinearity in dispersive media. AIMS Math 10(1), 754–776 (2025).

Han, T., Zhang, K., Jiang, Y. & Rezazadeh, H. Chaotic pattern and solitary solutions for the (21)-dimensional beta-fractional double-chain DNA system. Fractal and Fractional 8(7), 415 (2024).

Hattaf, K. On the stability and numerical scheme of fractional differential equations with application to biology. Computation 10(6), 97 (2022).

Ghori, M. B., Naik, P. A., Zu, J., Eskandari, Z. & Naik, M. U. D. Global dynamics and bifurcation analysis of fractional-order SEIR epidemic model with saturation incidence rate. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 45(7), 3665–3688 (2022).

Grossman, M. & Katz, R. Non-Newtonian Calculus (Lee Press, Pigeon Cove, MA, USA, 1972).

Atangana, A. & Baleanu, D. New fractional derivatives with nonlocal and non-singular kernel: Theory and application to heat transfer model. Therm. Sci. 20(2), 763–769 (2016).

Sousa, J. V. D. C. & de Oliveira, E. C. A new truncated M-fractional derivative type unifying some fractional derivative types with classical properties. Int. J. Anal. Appl. 6, 83–96 (2018).

Alabedalhadi, M., Al-Omari, S., Al-Smadi, M., Momani, S. & Suthar, D. L. New chirp soliton solutions for the space-time fractional perturbed Gerdjikov-Ivanov equation with conformable derivative. Appl. Math. Sci. Eng. 32(1), 2292175 (2024).

ALqufail, M. A., ALDamki, S. A.,. Exact Solutions to New Potential Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations Using Extended Generalized Riccati Equation Mapping Method. J. Faculties Edu.-Univ. Aden18(2), 826–838 (2024).

Hosseini, K., Hinçal, E. & Ilie, M. Bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors, sensitivity analysis, and soliton solutions of a generalized Schrödinger equation. Nonlinear Dyn. 111(18), 17455–17462 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The research team thanks the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Najran University for supporting the research project through the Nama’a program, with the project code (NU/GP/SERC/13/77-7).

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Najran University under grant number (NU/GP/SERC/13/77-7).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Farwa Munir: Methodology, Investigation, Writing–original draft. Khaled M. Saad: Software, Investigation, Writing–review & editing . Muhammad Abbas: Supervision, Writing–original draft, Writing–review & editing. Asnake Birhanu: Funding Acquisition, Investigation, Writing–review & editing . Waleed M. Hamanah: Software, Investigation, Writing–review & editing. Tahir Nazir: Supervision, Writing–original draft, Writing–review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to publish the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Munir, F., Saad, K.M., Abbas, M. et al. Bifurcation analysis and analytical traveling wave solutions of a sasa-satsuma equation involving beta, M-truncated and conformable derivatives using the EGREM method. Sci Rep 15, 44483 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28164-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28164-6