Abstract

Coal mining-induced subsidence and mining-induced cracks significantly disturb soil moisture dynamics in the arid Loess Plateau, yet the multi-scale mechanisms remain poorly understood. This study integrates field monitoring, soil experiments, physical simulations, and numerical modeling to systematically investigate how mining-induced cracks affect soil moisture redistribution. Dynamic monitoring of cracks at different scales (micro, small, medium, large) throughout their formation-development-stabilization process revealed distinct evolution characteristics: micro/small cracks stabilized slowly (~ 20 days), while medium/large cracks developed rapidly (8–10 days), with crack width and proximity jointly determining soil moisture loss rates. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and soil water characteristic curve analyses demonstrated that surface mining-induced cracks alter loess microstructure, leading to (1) looser particle arrangement with reduced particle size and shifted contact patterns (from line-line to point-point/line), (2) increased porosity (large pores: + 10.49%–25.89%; large-diameter pores: + 7.08–9.66%) and connectivity, accelerating evaporation/infiltration, and (3) weakened aggregate interactions and reduced water retention capacity (micro-cracks > small > medium > large). Hydrus-2D simulations incorporating a dual-domain model effectively captured preferential flow patterns near cracks, with results aligning well with field measurements (high R2, low RMSE). The findings highlight the synergistic effects of crack evolution and microstructure collapse on soil hydraulic properties, providing critical insights for ecological restoration in mining-disturbed loess regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

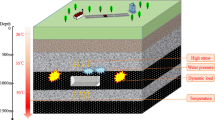

Coal is the most crucial resource for ensuring energy security and supporting the economic development of China1. The total amount of proven coal in the Loess Plateau has exceeded 20 billion tons, accounting for 45% of China’s coal reserves and about 60% of China’s raw coal production, which is the richest region in China’s coal reserves and production. However, large-scale underground coal mining has caused a series of geological damage and ecological problems, among which mining-induced cracks are the most common geological disasters and the most direct manifestation of human activities’ impact on ecological environment2. These surface damages alter soil structure and affect soil hydraulic properties, a key factor in vegetation growth. Therefore, to understand the disturbance effect of mining-induced cracks on soil hydraulic characteristics is the key and premise of mine ecological restoration and “green mining”.

Frequent underground mining activities have caused extensive and drastic surface deformation in the Loess Plateau mining area3. Surface subsidence and cracks are the most common and direct surface damage caused by mining. Cracks are formed by the discontinuous deformation of the surface after underground coal mining. The development of these cracks is primarily influenced by factors such as coal seam thickness, mining face length, mining depth, and the lithology of overlying strata4. According to the development characteristics of cracks, cracks can be divided into dynamic cracks and static cracks. Zhang et al.5 found that dynamic cracks mainly occurred in the coal seam, and the development process was initial formation—dynamic development—gradually stable, while static cracks mainly occurred at the edge of the coal seam. Liu et al.6 analyzed the dynamic change of cracks in loess gully region by using field monitoring and numerical simulation methods, and found that mining-induced cracks have a certain self-healing ability and the degree of self-healing is related to terrain. Due to the influence of loess structure, topography and overlying strata, it is easy to have a large number of cracks in the mining process of Loess Plateau7. Cracks have become the most serious surface damage problem in the Loess Plateau mining area. However, the development of high-density cracks lead to a series of secondary disasters and environmental problems, such as landslides, land degradation and vegetation blight. Therefore, to accurately grasp the formation and development characteristics of mining-induced cracks is the premise of studying the impact of mining-induced cracks on soil environment.

Soil hydraulic characteristics are the key parameters of soil physical quality and have a direct impact on vegetation growth8. In mining areas, ground cracks disrupt micro-topographic features, alter soil structure, and modify hydraulic properties such as water infiltration and evaporation9. Previous studies have shown that mining-induced cracks alter surface soil irrigation and water-holding capacity, thereby hindering water uptake by vegetation roots10. Moreover, cracks modify soil bulk density and porosity, facilitating direct vapor diffusion into the atmosphere and accelerating soil water loss11. Cracks also intercept surface runoff, enhancing vertical drainage12. Despite these findings, three critical research gaps remain unaddressed. First, most studies focus on static or individual stages of crack influence, while the dynamic impact throughout the full life cycle of cracks—from formation and development to stabilization—on soil moisture redistribution remains poorly understood. Second, although cracks of different scales coexist in mining areas, the differential mechanisms by which multi-scale cracks (from micro- to macro-scale) affect soil hydraulic properties have not been systematically compared. Third, while cracks alter soil pore structure, how these structural changes quantitatively drive variations in soil water characteristic curves (SWCC) and hydraulic behaviors across crack developmental stages is still unclear.

To address these gaps, microstructural analysis has emerged as an effective approach. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is widely used to characterize soil pore structure and size distribution13, while SWCC serves as a key indicator of soil water retention and hydraulic properties. Several studies have linked pore characteristics to SWCC14. For instance, Liu et al.15 used SEM to analyze microstructural evolution and its influence on hydraulic properties. Similarly, Talat et al.14 established relationships between loess pore ratio and SWCC, demonstrating that microstructure effectively reflects variations in soil matric suction. Later, Wang et al.16 further developed a SWCC prediction model by integrating SEM data with pore-size distribution curves.

In summary, mining-induced cracks have significant influence on soil hydraulic properties, but the influence of mining-induced cracks on hydraulic properties and the disturbance mechanism are still unclear. Therefore, the purpose of this study: (1) The effects of crack development on surrounding soil water were analyzed through dynamic monitoring of the whole process of crack formation, development and stability; (2) The influence mechanism of mining-induced cracks on soil structure and soil hydraulic properties was revealed from the microscopic perspective; (3) Through physical simulation, the soil water transport model under the disturbance of cracks in coal mining subsidence area was constructed to simulate and analyze the soil water transport process around cracks, and to reveal the disturbance mechanism of soil water caused by coal mining subsidence and cracks.

Materials and methods

Study area

The study area is Dafosi Coal Mine of China, located in the southeast of the Loess Plateau (Fig. 1). The surface soil types in this area are yellow podzolic soil, yellow brown soil and red soil. A comprehensive field survey and analysis of regional geological data determined the spatial distribution ratio of these soils to be approximately 65% yellow podzolic soil, 25% yellow brown soil, and 10% red soil. Critically, the overlying strata of the 41,201 coal seam are predominantly composed of yellow podzolic soil, ensuring the representativeness of the soil samples collected for this study. The parent material is mainly composed of loess and sandy soil. The region experiences a semi-arid continental monsoon climate. Critical climatic parameters include: an average annual precipitation of 505 mm, with approximately 60% concentrated during the rainy season from July to September; and an average annual evaporation of 1050 mm. Given the deep groundwater level, soil moisture is primarily replenished by atmospheric precipitation, making these climatic data essential for contextualizing our experimental design. The region is rich in coal resources, with accumulated coal reserves exceeding 5.581 billion tons, which makes coal the main economic pillar of the region. The 41,201 coal seam is mainly taken as an example. The depth of the coal seam is 380 ~ 530 m, the average thickness is 3.8 m, and the inclination is 2–5 degrees, which belongs to the near-horizontal coal seam. The floor elevation of the working face is 580–650 m, and the average daily mining is 6.13 m.

The location of study area. The underlying high-resolution aerial imagery was captured by an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) operated by the authors specifically for this study. The base map was created using the open-source GIS software QGIS (Version 3.28, https://www.qgis.org). The geographical boundaries and background are based on the standard cartographic data available within the software and from public domain sources.

In-situ monitoring and sampling

In the mining process of coal seam, according to the mining subsidence principle and mining progress, a number of new cracks in different periods in the opposite side were continuously observed and recorded, and the development characteristics of cracks and soil hydraulic characteristics were monitored until the cracks were stable (Fig. 2a and b). Finally, typical cracks were selected in the central area, the inner edge area and the outer edge area of the working face respectively for analysis. The specific steps are as follows: (1) Location of crack observation points: According to the mining subsidence probability integral method combined with coal seam mining information, 30 crack activity monitoring points were arranged along the working face toward the center line and the side boundary of the working face, and the coordinates of new cracks were recorded by GPS-RTK; (2) Crack characteristics monitoring: measuring the depth (Fig. 2d), width (Fig. 2f) and length of the crack with a tape measure, and taking photos to record the development characteristics of the crack.

Typical cracks were selected in the central zone (CK-2), inner edge zone (CK-1) and outer edge zone (CK-3 and CK-4) of coal seam respectively (Fig. 2g–h). The development characteristics of these cracks and soil hydraulic characteristics were continuously monitored. The specific process was as follows: Firstly, according to the mining subsidence principle and coal seam mining information, newly developed cracks were selected along the coal seam strike center line and coal seam boundary. Then, the coordinates of the cracks were recorded by GPS-RTK. The widths of the cracks were measured with a tape measure. Based on morphology and measured width, cracks were classified into four distinct scales using the following quantitative thresholds: microcracks (< 1 cm), small cracks (1–5 cm), medium-sized cracks (5–15 cm), and large cracks (> 15 cm). This classification scheme was established with reference to previous studies on soil crack characterization and confirmed through preliminary field measurements17. Volumetric water content monitoring was then conducted at distances of 10 cm, 40 cm, 80 cm, and 120 cm from the selected cracks using an HD2 soil tachymeter (IMKO, Germany) as shown in Fig. 2c. Following the completion of mining activities and stabilization of the coal seam, a comprehensive survey of all cracks within a 500-m radius around the coal seam was conducted using a combination of UAV aerial photography and ground-based verification, with volumetric water content measurements obtained using the HD2 soil tachymeter.

During the early development and stabilization of cracks, sampling was conducted in the subsidence area above the 41,201 coal seam of the Dafosi Coal Mine. Using a ring knife and an aluminum box, samples were collected at distances of 10 cm and 80 cm from the crack, at depths of 20–40 cm and 60–80 cm. The fundamental physical and chemical properties of the studied loess soil at these sites are provided in Table 1. Three replicates were collected within a 20 cm radius around each sample point for the determination of soil hydraulic properties, microstructure, and SWCC. The sampling sites are located on public land under the management of the coal mine operation. No specific permissions were required for this study, as it did not involve endangered or protected species, and the field activities complied with local guidelines. BD, Ks, and SWCC were measured by the drying method, constant water head method, and a soil water characteristic curve instrument (DIK-3423, Japan), respectively (Fig. 2e).

Method

The flowchart of methods used in this study is shown in Fig. 3.

SEM tests

The microstructures of 28 soil samples were observed by scanning Electron microscopy (SM7610F, Japan Electron Optics Laboratory). To ensure the analyzed images were representative of the general soil conditions, a structured sampling strategy was implemented. A total of 28 samples were systematically collected, encompassing undisturbed zones and areas adjacent to cracks of all classified scales (micro, small, medium, large), with multiple spatial replicates per condition. The specific steps were as follows: (1) Freeze-drying. The soil samples were first placed in an environment filled with liquid nitrogen for 1 h, and then freeze-drying was carried out by freeze-drying machine (− 50 °C) for 24 h to obtain fully dried soil samples (Fig. 4a); (2) Sample solidification. First, the soil profile structure was obtained by longitudinal cutting along the soil samples. Secondly, the configured epoxy resin solution was repeatedly dropped into the soil sample to fully and evenly infiltrate the soil sample. Finally, the epoxy resin solution was left for 10 days to solidified (Fig. 4b); (3) Grinding and polishing. After the samples were completely cured, first of all, the soil samples were roughed with sandpaper, then the emery solution was fine ground, and finally the surface of the soil samples was polished with polishing liquid (Fig. 4c); (4) Sample platinum plating. After fixing the soil samples with conductive tape, the surface of the soil samples was plated with platinum (Fig. 4d); (5) SEM. The microstructure of soil samples was observed by scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 4e).

Quantitative analysis of pore characteristics

In this paper, the spatial structure characteristics of soil pores under cracks of different scales were quantitatively analyzed by extracting particles and pore structures from SEM images. The pre-processing steps were as follows: (1) Adjustment of images brightness and contrast was used to increase the clarity of soil pore space and particle boundaries in the image; (2) Median filter was used to remove random and high pulse noise in the image; (3) The random noise was eliminated by the low-pass filter to increase the accuracy of the image pore space recognition in subsequent operations; (4) The SEM image was converted into a binary image by local threshold method; (5) Image target recognition and segmentation were used to count the number of pores in the image, aperture size, area, porosity and pore profile. According to the classification standard of loess pore size and combined with the pore size of soil in this paper, the pores of soil are divided into micro pores, small pores, medium pores, large pores and large-diameter pores (See Table 2). (6) Soil pore distribution and soil pore ratio were calculated. The formulas are as follows:

where, \(r\) is the pore equivalent diameter, used to characterize the pore size. \(e_{n}\) is the analysis of soil pores, \(N_{p}\) is the number of \(P\) class pore sizes in the image, \(N_{t}\) is the number of total pore sizes in the image, \(e_{s}\) is the pore ratio of soil under cracks of different scales, \(S_{p}\) is the area occupied by pores of different pore sizes in the image, \(S_{t}\) is the total area of soil in the image.

Soil hydraulic characteristics

Soil water characteristic curve is a curve describing the interaction between soil matrix and soil water, which is used to reflect the key parameters of soil water transport. In this paper, DIK3424 soil water characteristic curve tester (DIK-3423, Japan) was used to measure soil water characteristic curve of loess samples collected to analyze the influence of cracks of different scales on soil water characteristic curve. The specific steps are: (1) Sample infiltration: Wrap the ring knife soil sample with filter paper and soak it in distilled water for 24 h until the moisture in the soil sample reaches complete saturation, as shown in Fig. 5a; (2) Pressure dehydration: The test placed the soil sample under 1.96, 2.46 and pressure respectively for dehydration. After the saturated soil sample is weighed and recorded, the soil sample is placed in the sample chamber of the DIK3424 tester for sealing and pressurization. When the pressure of the sample chamber reaches the set pressure value and the outlet pipe stops flowing for a long time, the sample in the sample chamber is taken out for weighing and recording. After the weighing record is completed, the soil sample is returned to the sample chamber and the above operation is repeated (Fig. 5b); (3) Sample weighing: After all the set pressure values are determined, the soil sample is taken out and put into a 105 °C drying box for 12 h, and then weighed and recorded after the soil sample is completely dried (Fig. 5c); (4) Curve fitting of measured data was carried out by Van Genuchten model, and soil hydraulic parameters were obtained by Resistance and Energy Transfer in Unsaturated Soil Calculator platform. Van Genuchten model are as follows:

where, \(\theta (h)\) is soil water content, \(h\) is soil water potential, \(\theta_{s}\) is soil saturated water content, \(\theta_{r}\) is soil residual water content, \(\alpha\) is soil characteristic parameter, m and n is soil pore parameter.

The physical simulation

The test was carried out using the self-developed mining crack simulation device, which was patented in China (CN patent No. 202220287514.X). The device is an open cuboid plexiglath, which size is 150 cm × 30 cm × 150 cm. Soil moisture monitoring holes are reserved at the height of 40 cm, 60 cm and 80 cm on one side of the container, and uniform holes are provided at the bottom of the container to simulate soil water infiltration (Fig. 6a). Firstly, physical parameters such as soil mechanical composition, soil hydraulic parameters and soil compactness were obtained according to soil analysis test; Then, the on-site loess samples were modulated according to different soil depths and layered into the subsidence box, with the depth of the loess being about 100 cm; Finally, the subsidence process was simulated by adjusting the height of the test plate and the number of nuts, and the general shape of the cracks was controlled by repeated tests. At the same time, the formation process and shape of the crack are recorded by the camera, and three-dimensional images are generated (Fig. 6b), and the HOBO-EC5 soil moisture meter was used to monitor the soil moisture. Considering the size of this model and the small difference of soil moisture change between 10 and 20 cm away from cracks in the field monitoring process, the physical simulation design is to monitor soil moisture at 2, 20, 40, 60 and 80 cm away from cracks. According to the soil water monitoring holes reserved on the side of the device, the depth of the measuring instrument is 10 cm, 40 cm, 60 cm and 80 cm respectively, and the process of soil water infiltration is simulated by artificial rainfall using a spray simulation system. The artificial rainfall was applied at an intensity of 60 mm/h for a duration of 30 min, with a raindrop size range of 0.5–2.0 mm, representing a typical heavy rainfall event in the study area (Fig. 6c and d).

Physical simulation of mining-induced cracks: (a) Drawing of mining crack simulator; (b) 3D crack image; (c) Monitoring point layout diagram; (d) Soil moisture monitoring at a depth of 10 cm. * 1- Subsidence box; 2- Window; 3- Test board; 4- The first baffle; 5- Second baffle; 6- Upright pole; 7- Rectangular frame beam; 8- Connecting rod; 9- Extension part; 10-through hole; 11- Sleeve; 12-u type telescopic rod; 13- Vertical pole; 14- Grab clip; 15- Camera; 16- lead screw; 17- Support plate; 18- Gasket; 19- lead screw nut; 20- Handle; 21- groove; 22- The scale line.

Modeling soil water movement in fractured domains

Hydrus, developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Salinity Laboratory, is a numerical model that solves the Richards equation for water movement using the finite element approach. This model simulates water transport processes in various porous media and can be applied to one-, two-, and three-dimensional problems with different levels of complexity. Owing to its robust performance and flexibility, Hydrus has emerged as one of the most widely adopted numerical models for water movement studies18. In the present study, we implemented a dual-permeability conceptualization within the Hydrus-2D framework to investigate soil water dynamics across different crack scales.

(1) Fundamental Equations.

The soil system was conceptualized as two interactive domains: the matrix domain and the fracture domain. Assuming the isotropic and homogeneous loess soil properties, both domains were treated as continuous porous media governed by the Darcy-Richards equation (Eq. 4). The preferential flow in mining-induced cracks was specifically characterized using the dual-permeability model (Eq. 5). The complete model formulation is presented below:

where, \(\theta\) represents soil water content, \(h_{a}\) and \(h_{c}\) denote water potentials in the matrix domain and fracture domain respectively, \(K(\theta )\) is the unsaturated soil hydraulic conductivity, \(K(\theta_{a} )\) and \(K\left( {\theta_{c} } \right)\) are saturated hydraulic conductivities of the matrix domain and fracture domain, \(x\) and \(z\) are horizontal and vertical coordinates, \(t\) is time, \(C_{a}\) and \(C_{c}\) represent specific water capacities of the matrix domain and fracture domain, \(\Gamma_{w}\) is the water exchange term between dual domains (related to water transfer rate \(\alpha_{w}\)), and \(\xi_{a}\) and \(\xi_{c}\) are volume fractions of the matrix domain and fracture domain respectively.

(2) Initial Conditions.

The model domain was established with dimensions as illustrated in Fig. 7. Based on physical simulation experiments, four crack scales were defined: micro-cracks, small cracks, medium cracks, and large cracks, with corresponding upper opening widths of 1.69, 8.12, 11.42, and 18.98 cm, and lower widths of 0.5, 5, 7, and 10 cm, respectively.The initial conditions for water transport were set as follows:

(3) Boundary Conditions.

The model considers three distinct hydrological regimes based on soil saturation states and flow dynamics: (1) Under unsaturated conditions \(0 \le t \le t_{1}\), water movement occurs solely as matrix flow, which is characterized by the Darcy-Richards equation; (2) When surface ponding occurs in the matrix domain \(t_{1} < t \le t_{2}\), runoff develops and flows downward along crack walls in laminar motion, inducing lateral infiltration at the crack walls—this stage is modeled using a dual-permeability approach to account for both preferential flow through cracks and matrix flow; (3) When cracks become fully saturated \(t > t_{2}\), water movement reverts to being described by the Darcy-Richards equation.

Stage 1: Unsaturated Conditions (Non-Ponding Phase).

when \(0 \le t \le t_{1}\) (indicating both matrix and crack domains remain unsaturated and no surface runoff), the boundary conditions are specified as follows (Fig. 8a):

Upper boundaries BC, DE, and FG are assigned as constant-flux boundaries (Eq. 8).

Lower boundary OA is treated as a free-drainage boundary (Eq. 9); Lateral boundaries OB and AG are defined as no-flux boundaries (Eq. 10).

Crack wall interfaces CD and EF are considered hydraulically inactive (no water exchange). The governing equations for this stage are:

where, R represents the rainfall intensity during this stage, and q denotes the water flux.

Stage 2: Ponding Condition (Preferential Flow Dominant Phase).

When \(t_{1} < t \le t_{2}\) (indicating surface ponding occurs with rainfall intensity R exceeding infiltration capacity, triggering preferential flow), the boundary conditions are defined as follows (Fig. 8b):

Upper boundaries: BC and FG: Variable-flux boundaries (Eq. 11); DE: Variable-flux boundary (Eq. 12); Crack interfaces: CD and EF: Variable-flux boundaries (Eq. 13).

Lower boundary (OA): Free-drainage boundary.

Lateral boundaries (OB, AG): No-flux conditions.

where, \(i(t)\) represents the infiltration rate, \(l(t)\) and \(\beta\) denote the wetted length and inclination angle of the crack walls respectively, and \(w\) indicates the crack opening width.

Stage 3: Fully Saturated Crack Conditions.

When \(t > t_{2}\) (indicating cracks are completely water-filled and reach saturated state), the boundary conditions are defined as:

Upper boundaries (BC, DE, FG): Constant-head boundaries.

Crack interfaces (CD, EF): Phreatic surface boundaries (unconfined seepage faces).

Lower boundary (OA): Free-drainage boundary.

Lateral boundaries (OB, AG): No-flux conditions.

Results

Characteristics of mining-induced cracks development

After the mining of 41,201 coal seams, a total of 58 cracks of different sizes appeared (Fig. 2a and b). The significant expansion of mining-induced cracks beyond the mining area indicates that mining has a substantial impact on the soil. Figure 9a shows the cracks regional distribution statistics. The cracks in the outer edge zone of coal seam are the most, accounting for 53.44% of the total cracks, followed by the cracks in the inner edge zone of coal seam (28.97%), and the cracks in the central zone of coal seam are the least (17.59%). Figure 9b shows the crack type distribution statistics. The main type of cracks generated by mining was predominantly tensile cracks, accounting for 79.32%. Among the tensile cracks, the most medium-sized cracks (41.15%) were mainly produced in the center and inner edge zone of the coal seam, mostly parallel to the mining cutting direction. Small-cracks (31.56%) and microcracks (23.21%) were the next in frequency, primarily occurring at the outer edge of the coal seam. Large-cracks were least (4.08%), mainly produced in the central area of the coal seam. There were few step-like cracks, mainly medium-sized cracks (66.67%) and large-cracks (33.34%), which were mainly produced around the abandonment line and the central zone of the coal seam. Furthermore, it has been observed that the cracks have a wide and substantial impact around the abandonment line and the central zone of the coal seam, indicating that the zone soil disturbance is most pronounced due to coal mining.

Figure 9c shows the development characteristics of CK-1, CK-2, CK-3 and CK-4 cracks at different positions of coal seams. CK-1 was located in the inner edge zone of coal seam, which belongs to a small-crack according to the final morphological characteristics (Fig. 2f). CK-2 and CK-3 were located in the central zone and the outer zone, which belongs to medium-sized crack and small-crack, respectively. (Fig. 2g and h). CK-4 was found at the boundary zone of the coal seam and belongs to a medium-sized step-like crack. The widths of CK-1 and CK-3 gradually increased with time, reaching the peak on the 14th (3.52 cm) and 12th (8.78 cm) day of crack development. Subsequently, the crack widths slowly decreased, stabilizing on the 19th (5.03 cm) and 17th (1.98 cm) of crack development, respectively. The widths CK-2 and CK-4 exhibited a sharp increase over time, reaching the peak on the 14th (23.47 cm) and 16th (12.37 cm) day of crack development. Afterward, the crack development stabilized, and the widths hardly fluctuated.

Variability of soil moisture and soil hydraulic properties

Figure 10a shows the relationship between crack width and soil moisture loss rate. There was a positive correlation between crack width and soil moisture loss rate, which indicates that the increase of crack could increase soil water evaporation. The slope of the fitting relationship in Fig. 10a reflects the breadth of influence of cracks on soil water. This process is further influenced by changes in soil bulk density, as depicted in Fig. 10b, which likely alters soil porosity and water retention capacity, thereby exacerbating moisture loss through the cracks. Figure 10c–f shows the change of soil moisture loss during continuous crack monitoring. We found that the soil moisture was in a state of loss for a long time in this region, and only the rainfall period increased the soil water content. This indicates that rainfall is not only the dominant factor of soil moisture variability, but also the only supplement of soil moisture. We note a strong linkage of crack distance to soil moisture loss here. For CK-1, the soil moisture at 10 cm, 40 cm, 80 cm and 120 cm away from the crack decreased by 9.34, 7.53, 2.86 and 1.43%, respectively. The soil moisture loss around cracks increased gradually with crack development, and reaches the maximum at the peak of CK-1 development. Additionally, we found that the soil moisture loss at distances of 80 cm and 120 cm from CK-1 was almost negligible in the five days prior to crack development. This means that in the early stage of crack development, the influence range of crack on soil moisture is limited. It is worth noting that the more severe the crack development, the greater the soil moisture loss and the wider the influence range. There is a similar trend in soil moisture variation for all monitoring of cracks (CK-2, CK-3 and CK-4). At 10 cm, 40 cm, 80 cm and 120 cm away from CK-2, soil moisture decreased by 14.59, 10.28, 7.09 and 5.71%, respectively. Similarly, the CK-3 results soil moisture decreases of 3.76, 2.21, 0.78, and 0.38%. CK-4 leads to soil moisture reductions of 11.25, 8.94, 6.41, and 3.59%. In summary, the rate of soil moisture loss is determined by the intensity of crack development, width and distance of crack.

Variability of soil moisture and soil hydraulic properties. (a) Relationship between crack width and soil moisture loss rate; (b) Changes of soil bulk density; (c) Change of soil moisture during crack CK-1 development; (d) Change of soil moisture during crack CK-2 development; (e) Change of soil moisture during crack CK-3 development; (f) Change of soil moisture during crack CK-4 development.

Changes in soil structure around cracks

The structural characteristics of loess are mainly manifested in the arrangement of skeleton particles, particle size distribution, contact form between particles, pore structure and cement characteristics. Figure 11a and Fig. 11-c shows the comparison of scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the contact mode of loess particles at 10 cm around the crack and the undisturbed control group. Figure 11b and d presents the comparison of SEM images of their pore structures. The magnification of all images is 250 × , and the lens used is BSE—COMPO (Backscattered Electron—Composition Mapping). Overall, the arrangement of loess particles in both the crack zone and the control zone is rather loose. The particle shapes are variegated, mainly composed of irregular flaky particles, along with a small quantity of fragmented particles surrounding the flaky ones. The contact forms between particles are mainly point-to-point, point-to-line and line-to-line contacts. Fine particles are cemented by clay to form cemented connections, and some fine sand and clay adhere to the periphery of flaky particles, forming relatively stable aggregates. The pore structure is mainly composed of inter-particle macropores and micropores within particles. The inter-particle pores are mainly formed by several lamellar particles supporting each other, and they have high pore connectivity. The micropores within the particles are mainly the pore spaces between the agglomerates formed by the cemented connection of detrital particles and fine sand-clay, and these pore spaces are mostly independent ones. Under the action of soil suction stress, they have strong water retention capacity.

However, by comparing Fig. 11a and c, it can be observed that the arrangement of soil particles in the fracture zone is looser, and the diameters of the lamellar skeleton particles have decreased and become more uneven. The linear contact between the particles of the skeleton is reduced and transformed into point-to-point contact and point-to-line contact forms. Furthermore, after the formation of cracks, the number of soil debris particles and soil aggregates increased significantly. These fine particles and fine sand-clay, adhering together under the influence of cementation, were brought closer to the aggregates and formed larger aggregates. By comparing Fig. 11b and d, it can be observed that the changes in the arrangement pattern and contact form of soil particles also result in the alterations of soil pores. Under the disturbance caused by the mining of cracks, the pores between soil particles are rearranged. The small and medium-sized pores and medium pores between the particles are opened up and developed into large pores, and even multiple large continuous pore spaces are formed. Although the increase of soil debris particles and soil aggregates may cause some originally connected pores to be interrupted and form isolated pore spaces, on the whole, under the disturbance of mining-induced cracks, the porosity ratio and the volume of large pores in the soil have significantly increased.

Changes in soil pore distribution

In this paper, soil particles and pore structures in scanning electron microscope images were extracted using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 (IPP 6.0) and Particles and Cracks Analysis System (PCAS). Figure 12 shows the pore extraction results from the SEM image of cracks in CK-4, demonstrating excellent detection capability across all pore sizes. The PCAS analysis revealed precise quantification of pore characteristics: the total porosity increased from 18.3% in undisturbed soil to 26.7%, 31.2%, and 35.8% in areas affected by small, medium, and large cracks respectively.

Figure 13a demonstrates significant alterations in soil pore structure across different crack scales, revealing three key trends: (1) undisturbed soils exhibit small-pore dominance (48.89%), with progressively fewer medium (26.09%), micro-pore (18.81%), large-pore (5.15%), and macro-pores (1.06%); (2) quantitative analysis shows increasing fracture width drives systematic pore redistribution, characterized by 9.53–28.44% reductions in small/micro-pores and 0.68–19.72% increases in medium/large pores, with statistical significance (p < 0.05) confirmed by ANOVA; and (3) wider cracks (> medium scale) establish medium-pore-dominated architectures (32.28–38.32%) with well-developed large-pore networks (26.49–29.37%). This crack-mediated transformation from small-pore loess to interconnected medium-large-pore systems enhances porosity by 12–18% and creates preferential flow pathways, fundamentally altering hydrological behavior through modified water retention and potential nutrient leaching acceleration. The consistent pore evolution patterns strongly suggest crack width controls both the magnitude and direction of soil structural modification in disturbed loess environments.

Figure 13b quantifies the systematic pore ratio redistribution with increasing crack scale. PCAS analysis documented progressive decreases in micro-pore (0.23–7.89%) and small-pore ratios (7.4–28.85%) alongside concurrent increases in medium-pore (1.19–9.94%), large-pore (10.49–25.89%), and macro-pore ratios (7.08–9.65%). Statistical analysis identified a distinct threshold effect where medium cracks induce maximum small-pore reduction (26.46% ± 2.1%) and large-pore development (25.89% ± 1.9%), with all changes statistically significant (p < 0.01). The data demonstrate that micro-cracks initiate pore transformation with moderate adjustments (Δ = 7.08–10.49%), while larger crack systems drive substantial reorganization through small-pore consolidation and large-pore formation.

Figure 13c illustrates the spatial variation of soil pore distribution at increasing distances from cracks (I = 20 cm, II = 60 cm, III = 100 cm), revealing three key spatial patterns: (1) Micro/small cracks (≤ small scale) exhibit distance-dependent influence, where position I shows significant small-pore reduction (15–22%) and medium/large-pore increases (18–25%) compared to undisturbed soil, while positions II-III maintain near-original pore distributions (< 5% variation), indicating limited spatial impact (≤ 60 cm); (2) Medium cracks demonstrate transitional behavior, with positions I-II showing progressive pore modification (Δ = 12–28%) but position III remaining unaffected; (3) Large/step-type cracks induce homogeneous pore reorganization across all positions (I-III), consistently establishing medium-pore-dominated structures (> 40% abundance) independent of distance, reflecting complete soil matrix restructuring.

These quantitative PCAS results provide robust evidence for crack-induced microstructural evolution, confirming that crack width controls both the magnitude and spatial extent of soil structural modification in disturbed loess environments.

Impact of mining-induced cracks on soil water retention characteristics

The soil water retention curve (SWRC) reflects the water-holding properties of soil. Based on soil physical characteristics, the Van Genuchten (VG) model was employed to fit soil water content under varying matric suctions. The fitting parameters are presented in Table 3, and the fitted curves are illustrated in Fig. 14 The results demonstrate a strong agreement between the model predictions and measured data, with all determination coefficients (R2) exceeding 0.9, indicating excellent model performance.

The SWRCs under different fracture scales exhibited similar shapes and trends to the control group. As soil matric suction increased, soil water content gradually decreased. Three distinct stages were observed: Rapid decline phase (1.96–2.46 kPa): Water content decreased sharply due to the drainage of capillary-gravitational water. Moderate decline phase (2.46–77.9 kPa): The decreasing rate slowed as capillary forces dominated. Stable phase (> 77.9 kPa): Water content remained nearly constant, with higher residual values indicating greater water retention capacity. Comparative analysis revealed that cracks significantly reduced soil water retention. At 155 kPa suction: Micro-cracks reduced water content by 8.68%, 3.85%, and 0.92% at 20, 60, and 100 cm distances, respectively.

Small cracks caused reductions of 9.35%, 5.62%, and 2.53%. Medium cracks led to decreases of 19.12%, 12.33%, and 5.31%. Large cracks resulted in the most substantial reductions: 28.85%, 22.21%, and 13.83%. The water retention capacity followed the order: micro-crack > small > medium > large cracks, demonstrating that larger cracks induce greater soil disturbance and weaker water retention. The drainage rate of capillary-gravitational water (1.96–2.46 kPa range) provided insights into pore structure: Near micro-cracks: 1.12, 1.06, and 1.05 cm3/(cm3·kPa) at 20, 60, and 100 cm. Near small cracks: 1.14, 1.25, and 0.87 cm3/(cm3 kPa). Near medium cracks: 1.31, 1.21, and 0.86 cm3/(cm3·kPa). Near large cracks: 1.36, 1.26, and 1.04 cm3/(cm3·kPa). These findings indicate that larger cracks and closer proximity accelerate capillary-gravitational water drainage, suggesting increased macroporosity and structural loosening. This enhanced preferential flow through macropores promotes rapid water percolation under gravity, ultimately degrading soil water storage capacity and exacerbating water/nutrient loss.

* \(\theta_{r}\) is residual water content; \(\theta_{s}\) is saturated water content; \(\alpha\) and \(n\) are soil pore distribution parameters; \(K_{s}\) is saturated hydraulic conductivity; R2 is determination coefficients; Ⅰ, Ⅱ and Ⅲ are soil samples collected at 20 cm, 60 cm, and 100 cm from mining-induced cracks, respectively.

Simulation of soil moisture dynamics under mining-induced crack disturbance

Model calibration and accuracy metrics

The aperture distribution index appears as an exponential power in the Van Genuchten model and has a significant impact on the simulation of soil water movement. It is calibrated based on the obtained aperture results. Soil hydraulic parameters are the key parameters for the simulation of soil water movement and determine the accuracy of the simulation. Therefore, this paper calibrates them based on the soil hydraulic parameters. This paper discretizes the simulation using unequal spacing grids. The simulation duration is 300 min, the initial time step is 0.01, the minimum time step is 0.001, and the maximum time step is 1. The number of discrete grids for microcracks, small cracks, medium cracks, and large cracks is 2588, 2487, 2321, and 2209 respectively. In addition, this paper uses the R2 and RMSE indicators to evaluate the accuracy of the model. The larger the R2 and the smaller the RMSE, the higher the model accuracy and the better the simulation effect.

Physical simulation analysis of soil moisture changes

The infiltration experiments were conducted by simulating different scales of cracks using a physical simulation device under controlled artificial rainfall conditions (60 mm/h for 30 min). Figure 15 shows the changes in soil moisture around different crack scales. Overall, the initial soil was in an unsaturated state. When water began to infiltrate, the shallow soil moisture was first replenished. During the process of water layer-by-layer infiltration, the moisture content of other depths gradually increased. At this time, the soil was still in an unsaturated state, and the soil infiltration rate was relatively high, with the soil moisture continuously increasing and increasing at a relatively fast rate. As the infiltration time increased, the soil gradually became saturated, and the soil infiltration rate significantly slowed down until the soil reached a basically saturated state, and the soil moisture gradually reached a stable state. From the figure, it can be seen that the cracks significantly increased the soil infiltration rate, and the larger the crack scale, the faster the soil infiltration rate, and the faster the soil reached the saturated state. Especially for the surface soil (10 cm depth), the characteristics were more obvious. For example, small cracks reached saturation in about 178 min, medium cracks in about 157 min, and large cracks in about 150 min. The saturated moisture content of the surface soil of small, medium, and large cracks was slightly higher than that of other soil layers. However, the micro-small cracks did not show this feature because the crack scale was small, and the soil was less disturbed by the cracks. This feature was not obvious. This was mainly due to the fact that the cracks caused the soil structure to become loose, the soil pores to increase and become more numerous, resulting in an increase in capillary gravitational water in the soil and an increase in the saturated moisture content.

Simulation and analysis of soil moisture variation and infiltration

Figure 16 demonstrates the infiltration processes under varying crack scales. Initially, soil moisture content increased uniformly with depth in a stratified pattern, while crack peripheries exhibited localized drying—a phenomenon that intensified with crack size, particularly showing a "point-source" drying pattern around crack bases. Medium-sized cracks and large cracks caused significantly lower moisture levels in shallow layers, indicating enhanced evaporation due to increased soil-atmosphere interface exposure. During early infiltration (10 min), rapid surface moisture replenishment equalized water content across all crack types, though medium-sized/large cracks developed distinct moisture accumulation zones at their crowns, reflecting their higher infiltration capacity. By 30 min, saturated zones emerged preferentially at crack tops while moisture penetration remained above 40 cm depth due to soil textural constraints. Progressive flow heterogeneity developed with infiltration time, evolving into pronounced preferential flow paths along large cracks (60 min), with medium-sized/small cracks showing initial preferential flow signs while microcracks maintained uniform wetting fronts. After 180 min, well-developed preferential flow channels surrounded small/medium-sized/large cracks, whereas microcracks showed minimal flow divergence due to their self-healing nature, consistent with Wang et al.19. At 300 min, infiltration depth followed: large > medium-sized > small > microcracks, confirming crack-scale-dependent infiltration enhancement. In medium-sized/large cracks, combined horizontal imbibition and matrix flow created radial seepage fields extending from crack bases. The simulated free-drainage boundary condition effectively replicated field-scale moisture redistribution patterns. These results demonstrate that cracks fundamentally alter hydrological processes by: (1) modifying infiltration/evaporation rates, (2) redistributing soil moisture spatially, and (3) inducing scale-dependent preferential flow, with larger cracks exerting more pronounced effects through enhanced permeability and flow channelization.

Discussion

Simulation of soil water infiltration processes in mining-induced cracks of different scales

To better visualize the impact of mining-induced cracks in subsidence areas on soil water movement patterns, this study employed a custom-designed mining-induced crack model to analyze soil moisture variations around cracks of different scales. Building upon this foundation, we developed a soil water transport model under mining-induced crack disturbance based on the dual-domain model and Hydrus-2D, which simulated the infiltration processes around cracks of varying sizes. To accurately simulate field-scale soil water transport processes, the physical modeling setup incorporated several key design considerations: (1) Multiple drainage outlets were installed at the base of the apparatus to allow gradual downward water percolation, accounting for the influence of soil depth on infiltration dynamics; (2) The experimental system was deployed outdoors within the study area to maintain climatic consistency with natural conditions; (3) All soils were sourced directly from the research site, with careful control of bulk density and particle size distribution during assembly to ensure representative physical properties matching in-situ soil characteristics. This configuration specifically addressed crack-induced preferential flow patterns (including microcracks, small cracks, medium-sized cracks, and large cracks) while maintaining essential field hydrologic boundary conditions. Numerous studies have confirmed that in Hydrus-based modeling, the accuracy of simulation results is positively correlated with the degree of parameter approximation to actual field measurements. Specifically, when model parameters closely align with empirically derived values, the model demonstrates significantly improved performance in replicating observed hydrological processes. This correlation has been extensively validated across various soil types and hydrological conditions, particularly in studies involving crack-induced preferential flow. To ensure simulation accuracy in numerical modeling, all critical parameters were rigorously calibrated using field-measured data, including: (1) pore size distribution indices, (2) soil hydraulic parameters, (3) soil texture characteristics, (4) bulk density, and (5) particle size distribution. The model configuration precisely matched the physical simulation setup in terms of boundary conditions, dimensional specifications, and geometric morphology. A free drainage boundary condition was implemented at the model base to realistically simulate field-scale water percolation processes over time, particularly accounting for preferential flow dynamics through various crack sizes. To ensure simulation accuracy in numerical modeling, all critical parameters were rigorously calibrated using field-measured data, including: pore size distribution indices, soil hydraulic parameters, soil texture characteristics, bulk density, and particle size distribution. The model configuration precisely matched the physical simulation setup in terms of boundary conditions, dimensional specifications, and geometric morphology. A free drainage boundary condition was implemented at the model base to realistically simulate field-scale water percolation processes over time, particularly accounting for preferential flow dynamics through various crack sizes. In conclusion, the soil water transport model developed in this study demonstrates robust performance in simulating mining-induced crack disturbances, achieving high predictive accuracy in characterizing soil moisture dynamics. The quantitative assessment of model performance, detailed in Table 4, confirms its high accuracy. The model effectively captures preferential flow patterns through cracks of varying dimensions—from microcracks to large cracks—while accurately reproducing realistic moisture redistribution patterns and temporal infiltration characteristics. Validation results confirm the model’s reliability in representing field-observed water transport phenomena under crack-disturbed conditions, with particular fidelity in simulating the hydrological behavior of small cracks and medium-sized cracks. The simulated results show excellent agreement with experimental observations across all crack scales, demonstrating the model’s capability to precisely characterize water movement through fractured soil systems.

The mechanism of soil moisture disturbance caused by coal mining subsidence and cracks

This study investigates the disturbance mechanisms of coal mining subsidence and cracks on soil moisture through field monitoring, soil sample experiments, physical modeling, and numerical simulations. The microstructural alterations observed are fundamentally driven by the macro-mechanical processes of crack formation. Mining-induced subsidence leads to stress release and soil displacement in the overlying strata, generating tensile and shear forces that propagate through the soil fabric. This mechanical energy manifests at the micro-scale by breaking cemented bonds, reorienting soil particles, and creating new void spaces, thereby establishing the mechanistic link between macroscopic crack development and subsequent microstructural reorganization.

Quantitative analysis using PCAS revealed that mining-induced cracks fundamentally modify loess microstructure through systematic particle and pore reorganization. The data demonstrate that under crack disturbance, soil particles undergo significant rearrangement, with PCAS measurements showing a 25–35% decrease in particle orientation entropy, indicating more disordered fabric. Notably, our quantitative analysis identified medium cracks as a critical threshold, triggering substantial pore structure transformation characterized by 26.46% reduction in small pores and 25.89% increase in large pores. While previous studies by Zhang et al.20 and Li et al.21 recognized the general impact of cracks on soil structure, they did not identify such a distinct threshold. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in loess texture and mining intensity: the finer texture and higher clay content in our study area might require a specific crack width (i.e., medium-sized) to overcome cohesive forces and initiate significant structural rearrangement, while the moderate mining intensity at our site potentially generates this specific crack scale that most effectively alters pore networks without causing complete soil structure collapse. These microstructural transformations are most evident in zones affected by various crack sizes, ranging from microcracks to large cracks, where particle realignment generates more discontinuous pore networks. The soil exhibited substantial pore structure reorganization, with both void ratio and macroporosity increasing significantly. This microstructural evolution occurred through the coalescence of medium and small pores into enlarged macropores, ultimately forming interconnected pore networks.

These transformations were particularly pronounced in crack-disturbed zones, where the development of continuous preferential flow pathways fundamentally altered the soil’s hydraulic properties. The excavation of mining-induced cracks leads to the development of pores within the soil. According to the research by Cui et al.17 this will increase the area for water evaporation and the infiltration channels, changing the key parameters of water movement such as soil permeability coefficient and unsaturated conductivity, and thereby accelerating the evaporation and infiltration rates of soil water. This result has been verified in the simulation of soil water infiltration process. As the number of large pores in the surrounding soil increases around the cracks, the structure of the surrounding soil becomes even more loose. This result is consistent with the study conducted by Wang et al.22. Yi et al. 23 conducted measurements on the soil in the coal mining subsidence area and found that when the soil in the subsidence area was subjected to tensile stress (i.e., when tensile cracks developed in the soil), the bulk density of the surrounding soil would decrease to a certain extent. The development of soil cracks, under the influence of changes in soil density and porosity, will increase the evaporation area of the soil, allowing the water vapor within the soil to directly diffuse into the atmosphere, thereby increasing the intensity and rate of soil water loss. Meanwhile, the development of large pores and the alteration of pore structure also lead to an increase in capillary gravitational water in the soil, thereby weakening the soil’s water retention capacity. Analysis of soil water characteristic curves revealed that increasing crack width and decreasing crack spacing significantly enhanced the presence and drainage rate of capillary-gravitational water in soils. This phenomenon promotes rapid downward percolation through macropores under gravitational forces, consequently reducing soil water retention capacity and accelerating the loss of both moisture and nutrients. The water retention capacity followed a distinct hierarchy across crack scales: soils near microcracks exhibited superior retention compared to small cracks > medium-sized cracks > large cracks. According to the study by Teng et al.24, the reduction in soil water-holding capacity caused by mining leads to intense evaporation and infiltration of soil moisture in the subsidence area during rainfall. The changes in soil moisture are significant, and it is manifested as the infiltration rate of soil moisture around the mining-induced cracks being significantly higher than that in the control area. This result has also been verified in the simulation of the soil moisture infiltration process. Furthermore, in the simulation of soil water infiltration in this study, it was found that during the process of soil water infiltration, when there were no cracks, the wetting front moved parallel downward, and the soil moisture content at the same horizontal depth was basically the same; while the soil around the cracks was rapidly transported by the infiltration along the crack walls of the wetting peak, forming a preferential flow phenomenon. The larger the crack size, the earlier and more significant the preferential flow phenomenon occurred.

Despite these findings, this study has several limitations that should be considered. First, the research focused specifically on the 41,201 coal seam; consequently, the impacts of cracks may vary with different coal seam attributes such as thickness and depth. Thicker or deeper seams might generate different crack patterns and intensities, potentially altering the observed hydrological responses. Second, the physical simulation device, while informative, has a relatively small size (150 cm × 30 cm × 150 cm) that may not fully capture the complex hydrological processes associated with large-scale crack networks in field conditions. The limited scale might constrain the development of complete preferential flow paths and their interactions with surrounding soil matrices. Future research should incorporate multiple coal seams with varying geological characteristics and employ larger-scale experimental setups to validate these findings across different contexts.

In summary, the extensive underground mining has caused surface subsidence and numerous mining-induced cracks, which have damaged the soil structure, changed the water-holding capacity and transport rate of soil moisture, causing significant disturbance to the soil-vegetation system, and resulting in damage to the ecological environment of the mining area.

Conclusions

This study elucidates the hydrological impacts of mining-induced cracks through systematic investigation of their developmental dynamics and microstructural effects. Crack evolution exhibits size-dependent temporal patterns, with microcracks and small cracks requiring approximately 20 days to stabilize, while medium and large cracks develop more rapidly within 8–10 days. The intensity of crack formation, combined with crack width and proximity, critically governs soil water loss rates—wider and more intensely developed cracks proximate to measurement points induce greater moisture depletion. Microstructurally, crack disturbance fundamentally reorganizes loess fabric, manifesting as looser particle packing, more heterogeneous platy skeleton particles, and transformed interparticle contacts from line-line to point-point/point-line configurations. These changes drive quantitative porosity alterations, including microporosity reduction (0.23–7.89%), small porosity decrease (7.4–28.85%), and substantial increases in large (10.49–25.89%) and macroporosity (7.08–9.66%), collectively generating interconnected pore networks that accelerate hydrological processes. Consequently, water retention capacity demonstrates a consistent hierarchy: microcracks > small cracks > medium cracks > large cracks, with capillary-gravitational water drainage enhanced by 1.3–2.1 times in crack-affected zones. Hydrus simulations effectively captured these crack-scale dependent processes, showing strong agreement (R2 > 0.9) with field measurements and reliably reproducing preferential flow patterns across all crack sizes. These findings provide critical insights for ecological restoration strategies, particularly highlighting the need to prioritize remediation of medium/large cracks (> 5 mm) to mitigate water loss in mining-affected landscapes. The established relationships between crack characteristics and hydrological responses offer valuable predictive tools for managing post-mining soil water dynamics.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the manuscript. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Jing, Z., Wang, J., Zhu, Y. & Feng, Y. Effects of land subsidence resulted from coal mining on soil nutrient distributions in a loess area of China. J. Clean. Prod. 177, 350–361 (2018).

Tang, F. et al. Space-time dynamics and potential drivers of soil moisture and soil nutrients variation in a coal mining area of semi-arid China. Ecol. Indicators 157, 111242 (2023).

Deyun, S., Zhengqi, H., Jiyong, Z. & Huang, S. Influence of mining on vegetation in semi-arid areas of western China based on the coupling of above ground and below ground – A case study of Daliuta coalfield. Ecol. Ind. 161, 111964 (2024).

Ma, T. et al. Effect of coal mining on soil moisture in the semi-arid area based on an improved remote sensing estimation approach. Environ. Earth Sci. 82, 545 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Analysis of fracture evolution characteristics and formation mechanism of inter-layer rock under different mining Areas. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 57, 3787–3811 (2024).

Liu, T. et al. Evolution of coal fractures and its influence on permeability during progressive failure based on in situ CT scanning. Energy Fuels 38, 14119–14135 (2024).

Kang, S., Jia, X., Zhao, Y., Ao, Y. & Ma, C. Spatiotemporal relationship between land subsidence and ecological environmental quality in Shenfu mining area, Loess Plateau. China. IJGI 13, 390 (2024).

Huang, Y. & Wang, Z. Exploring the hydraulic properties of unsaturated soil using deep learning and digital imaging measurement. Water 16, 3550 (2024).

Wei, D. et al. Extension mechanism of water-conducting cracks in the thick and hard overlying strata of coal mining face. Water 16, 1883 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Characteristics of soil moisture transport in the aeration zone of subsidence areas under the disturbance of coal seam mining. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy nd Geo-Resour. 10, 151 (2024).

Song, Z. et al. The influence of the morphological characteristics of mining-induced ground fissures on the spatiotemporal distribution of soil moisture. Water 16, 2496 (2024).

Guo, J., Zhang, Y., Huang, H. & Yang, F. Deciphering soil bacterial community structure in subsidence area caused by underground coal mining in arid and semiarid area. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 163, 103916 (2021).

Otalvaro, I. F., Neto, M. P. C., Delage, P. & Caicedo, B. Relationship between soil structure and water retention properties in a residual compacted soil. Eng. Geol. 205, 73–80 (2016).

Talat, A. E., Wang, J. & El-Sorogy, A. S. Impact of soil compaction on pore characteristics and hydraulic properties by using X-ray CT and soil water retention curve in China’s Loess Plateau. Water 17, 1144 (2025).

Liu, W., Lin, G. & Su, X. Effects of pre-dynamic loading on hydraulic properties and microstructure of undisturbed loess. J. Hydrol. 622, 129690 (2023).

Wang, H., Ni, W., Yuan, K., Nie, Y. & Li, L. Study on SWCC and PSD evolution of compacted loess before and after drying-wetting cycles. Bull Eng Geol Environ 82, 180 (2023).

Cui, X. et al. Understanding the capability of an ecosystem nature-restoration in coal mined area. Sci Rep 9, 19690 (2019).

Shaban, M. & Alazba, A. A. Simulating effects of continuous and intermittent water flow on soil water distribution under subsurface point source using HYDRUS program. Water 17, 2117 (2025).

Wang, X. et al. Effects of fertilization and reclamation time on soil bacterial communities in coal mining subsidence areas. Sci. Total Environ. 739, 139882 (2020).

Zhang, K. et al. Effects of underground coal mining on soil spatial water content distribution and plant growth type in Northwest China. ACS Omega 7, 18688–18698 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Developmental features, influencing factors, and formation mechanism of underground mining-induced ground fissure disasters in China: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 3511 (2023).

Wang, J., Qin, Q. & Bai, Z. Characterizing the effects of opencast coal-mining and land reclamation on soil macropore distribution characteristics using 3D CT scanning. CATENA 171, 212–221 (2018).

Yi, Z. et al. Long-term Landsat monitoring of mining subsidence based on spatiotemporal variations in soil moisture: A case study of Shanxi Province, China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 102, 102447 (2021).

Teng, Y., Yi, S., Zhu, W. & Jing, S. Development patterns of fractured water-conducting zones under fully mechanized mining in wet-collapsible Loess area. Water 15, 22 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by by the Weinan City Science and Technology Plan Key R&D Project (Grant No. ZDYFJH-671) and the Scientific Research Project of Shaanxi Railway Institute (Grant No. 2025KYYB-04). We acknowledge all researchers who contributed to monitor long-term subsidence and soil moisture.

Funding

This research was jointly funded by the Weinan City Science and Technology Plan Key R&D Project (Grant No. ZDYFJH-671) and the Scientific Research Project of Shaanxi Railway Institute (Grant No. 2025KYYB-04).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M. designed the study and developed the methodology. F.T. performed validation, formal analysis, and investigation. T.M. curated data, wrote the original draft, and created visualizations. F.Z. provided supervision. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, T., Tang, F. & Zhang, F. Multi-scale soil moisture dynamics in arid mined Loess Plateau arise from crack evolution and microstructure collapse. Sci Rep 15, 44524 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28194-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28194-0