Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly applied in medical imaging, yet its ability to predict biological sex from pediatric radiographs remains unclear. This study investigates the performance of convolutional neural network (CNN) models in sex classification using a large dataset of pediatric trauma imaging and compares results with human raters. Radiographs from computed and digital radiography systems were processed to normalize grayscale and enhance contrast. The EfficientNet family of CNN models (B0–B7) was trained on this dataset, with attention to balancing the test set by age, sex, and fracture visibility. A subset of 1,000 images was independently assessed by human raters for comparison. AI models achieved a mean precision of 0.731 ± 0.035, recall of 0.718 ± 0.110, accuracy of 0.722 ± 0.032, and F1-score of 0.724 ± 0.050 across all network variants. Performance improved with age, peaking in the 13–18 group. Pelvic X-rays achieved the highest classification metrics. Human raters showed significantly lower agreement. AI can classify biological sex from pediatric radiographs with high accuracy, surpassing human performance. Results vary by age and body region, supporting the potential for AI-assisted imaging in pediatric clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have gained substantial momentum in medical research in recent years, demonstrating remarkable capabilities in image analysis and diagnostics. CNNs as a subcategory of artificial intelligence (AI) have already been successfully applied to various tasks in medical imaging, such as detecting tumors, classifying diseases, and predicting patient outcomes with high accuracy1. Expanding on these capabilities, the estimation of sex from pediatric radiographs holds significant potential across various domains, including forensic investigations, demographic modeling, epidemiological studies, and quality assurance in AI pipelines. Although not a routine clinical task, the automatic determination of sex using CNNs is particularly valuable in scenarios involving large datasets, such as epidemiological studies or high-throughput clinical environments. This automation enhances efficiency by rapidly processing large volumes of images, thereby aiding in resource allocation and decision-making processes. It can also help curate datasets for machine learning purposes when these labels are missing2. From a forensic standpoint, sex estimation from radiographs can also be crucial in identifying unidentified remains, providing essential leads in forensic investigations. Recent literature already shows that CNNs can extract more information from X-ray images than human experts, who typically cannot determine sex from such images without additional context3. This raises intriguing questions about the future potential of AI in medical imaging and its broader implications for diagnostic practices. However, the deployment of CNNs for sex estimation is not without challenges.

The risk of perpetuating or introducing biases through the training data is a significant concern, with potential repercussions on the accuracy and fairness of medical services provided to diverse populations4. Additionally, ethical considerations regarding patient privacy and the implications of automated decision-making in healthcare necessitate rigorous scrutiny.

The main hypothesis of this study was that AI could surpass the ability of human experts in sex recognition on X-rays of pediatric patients. It was also of interest whether, in addition to logical body regions such as pelvis or thorax images, other body regions could be used for sex prediction. We trained and tested a CNN with a large dataset of over 500,000 pediatric X-ray images to compare sex estimation with that of human experts.

Materials and methods

The Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Graz, Neue Stiftingtalstraße 6 - West, P 08, 8010 Graz (No. 31–108 ex 18/19) gave an affirmative vote for the retrospective data analyses. Informed patient or legal representative consent was waived due to the retrospective study design. All experiments were performed in accordance with the local legal regulations and the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participating raters prior to their involvement in the study.

We used the local de-identified pediatric trauma X-ray dataset for machine learning.

The images in the data set were acquired between 2008 and 2018, whereby the image annotations are continuously expanded and improved iteratively over time. It contains 541,864 images of 285,485 skeleton X-rays in 113,636 unique patients. A flowchart is depicted in Fig. 1. The biological sex labels used for model training and evaluation were based on entries in the hospital’s electronic medical records, based on personal information recorded at birth or during clinical care. No chromosomal or genital verification was available. The presence of intersex individuals was not documented in the dataset and could not be systematically identified.

Image acquisition

Radiographs had been obtained using various computed radiography (CR) or digital radiography (DR) systems by radiological technologists from our local Division of Pediatric Radiology. The images were stored as Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) files within the local Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS).

Image processing

The DICOM studies were retrieved from the PACS and subsequently converted to Portable Network Graphics (PNG) format. The original DICOM images were in 12-bit or 16-bit grayscale with varying image dimensions. These DICOM files were converted to 16-bit PNGs using the ”pydicom” and ”cv2” Python libraries6. The grayscale values were normalized to a 16-bit range while preserving the original pixel dimensions. The images then underwent post-processing with the ”exposure” module from the Python ”scikit-image” package8. Specifically, the 16-bit inputs were converted to float64 by dividing their grayscale values by 65,535. Intensity rescaling was performed by cropping the lower and upper 0.05th percentiles of the image histograms. Additionally, local contrast enhancement was applied using the ”exposure.adapthist” function with default settings. The processed image data, now in float64 format, was converted to 8-bit and saved to disk for subsequent analysis. Throughout these steps, the images retained their original height and width. During model training, the processed images were dynamically re-scaled to the required input sizes of the EfficientNet variants (B0 = 224 × 224 px, B1 = 240 × 240 px, B2 = 260 × 260 px, B3 = 300 × 300 px, B4 = 380 × 380 px, B5 = 456 × 456 px, B6 = 528 × 528 px, B7 = 600 × 600 px). Non-square images were padded with black pixels upon rescaling to the neural network input sizes.

CNN model, variants and training

For the binary classification task, the EfficientNet neural network9 was selected due to its proven performance in various medical imaging applications10,11,12 and due to past experiences. To ensure the robustness of the experiment, all variants of EfficientNet (B0 to B7) were trained and tested, reducing potential bias associated with image resolution. Model training was conducted on a Linux workstation equipped with two Nvidia RTX 4090 graphics cards, each with 24 GB of video memory. The system featured an Intel Core i7-13700K processor and 64 GB of RAM. The experiments were implemented using Python 3.10 on an Ubuntu 22.04 LTS platform. EfficientNet models were trained using the FastAI Python library (v2.7.15)13.

Testset selection

Great attention was given to the composition of the test set with the aim of avoiding possible external influencing factors as far as possible. Due to the whole dataset being related to trauma imaging, we decided to evenly balance the test set in terms of visible fractures. The idea behind this was that the neural networks could possibly learn the fracture types or injury patterns instead of the differences in the sexes. As some patients had received several different examinations, only one body region of each patient was transferred to the test set. All other images of the patient were excluded from the data set. The test set was then created using a self-written Python script in such a way that 5 slots were provided for.

-

each age group (0 to 18 years),

-

each projection (e.g. wrist a.p.), and

-

each normal finding and each fracture.

These slots were filled up to the maximum number of n = 5 if images with corresponding criteria were available. The theoretically possible number of images in the test set was 12,160 (= 2 sexes * 32 X-ray projections * 19 age groups * 2 fracture states * 5 images per slot). The 32 X-ray projections were part of 17 body regions (compare Table 1). 10,902 images could be fitted into the slots by the software, collected from 7,732 examinations of 6,392 unique pediatric patients. In the younger and older age groups in particular, there were sometimes too few or no samples available. These were therefore not filled, leaving a total of 1,258 image slots unoccupied. Table 1 gives a visual representation of the test set distributions. Note that there was only 1 X-ray projection (a.p.) in the clavicle and pelvis regions.

Human test set

Due to the large number of samples in the test set (n = 10,902), we were required to subsample data from the test set to determine whether human raters could correctly predict the biological sex from digital radiographs in children and adolescents. 1,000 images were randomly sampled from the test set for each of the 7 raters separately. Rater 1 MJ was a radiologist with 8 years, Rater 2 MS with 2 years, Rater 3 MZ with 9 years, Rater 4 NS with 4 years, and Rater 5 ST with 11 years of experience in interpreting trauma radiographs. Rater 6 HE was a pediatric surgeon with 6 years, and Rater 7 HT with 33 years of experience in pediatric trauma imaging.

The image data was provided on a private Linux server instance running the CVAT Labeling Platform v2.19.114 for binary annotation (female, male). The generated labels were then linked to the ground truth. The same test metrics (see below) as for the AI neural networks were applied.

Test metrics

We calculated widely recognized and commonly utilized AI performance metrics based on the rate of true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN), in total as well as split into various subgroups. We defined female = 0 and male = 1 for our analyses. Due to the nearly balanced data, we did not average the classes in regular and flipped order, like it would be appropriate in macro-averaged metrics for imbalanced data15.

\({\rm Recall:} \quad \quad \quad \:R=\frac{TP}{TP+FN}\)

\({\rm Precision:} \quad \quad \quad \:P=\frac{TN}{TN+FP}\)

\({\rm Accuracy:} \quad \quad \quad \:ACC=\frac{TN+TP}{TN+TP+FN+FP}\)

\({\rm F1 Score:} \quad \quad \quad \:F1=\frac{2TP}{2TP+FP+FN}\)

Apart from these metrics, we calculated precision-recall area under the curves (PR AUC) based on the ground truth values and the prediction probabilities in total and split for different parameters like age or presence of fractures. The scikit-learn package version 1.5.28 and matplotlib 3.9.216 were used to calculate PR AUC values and to plot the curves in Python 3.11.9.

To enhance interpretability and verify the relevance of learned features, we applied the GradCAM++ technique to visualize activation regions within the CNNs. Saliency maps were generated for test set images using the final convolutional layer of each EfficientNet variant. These maps were qualitatively analyzed to assess whether model decisions were based on anatomical structures rather than non-biological artifacts such as side markers or shielding17.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed to compare the performance of CNN models with that of seven human experts. Classification metrics as described above were calculated for the AI model as well as each expert. Additionally, precision-recall area under the curve (PR AUC) analyses including 95% confidence intervals (CI) were performed to evaluate the discriminative ability of the model. All data were checked for consistency and missing values to ensure the validity of the analyses. Body regions were sub-analyzed by grouping them into axial and appendicular skeleton, as well as long tubular bones and other regions. To assess classification performance variations with age, patients were additionally grouped into three categories: (1) 0–6 years, (2) 7–12 years, and (3) 13–18 years. Group comparisons were also conducted between unremarkable images and images featuring fractures. Humans and AI were compared side-by-side using the mentioned metrics. We used paired and independent samples t-tests to demonstrate differences in the described groups. A level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were computed using SPSS version 27.0.1.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

In total a dataset consisting of 541,864 images of 285,485 skeleton X-rays in 113,636 unique patients was trained. EfficientNet achieved a mean precision of 0.731 ± 0.035, a mean recall of 0.718 ± 0.110, a mean accuracy of 0.722 ± 0.032, and a mean F1 score of 0.724 ± 0.050 separating female and male sex when averaged across its eight neural network variants (B0 to B7). Mean precision was highest for EfficientNet-B4 with 0.780 ± 0.075, mean recall was highest in EfficientNet-B7 with 0.863 ± 0.070, the mean accuracy and F1 scores were highest for EfficientNet-B5 with 0.764 ± 0.074 and 0.784 ± 0.059, respectively. Comprehensive information on the performance of the EfficientNet variants in the different X-ray projections is available in the supplement Tables A2, A3, A4, and A5.

EfficientNet variant metrics

The best performing EfficientNet variant was B6 with a PR AUC of 0.839 (CI: 0.802–0.872), on par with the B4 variant 0.837 (CI: 0.800–0.871) and B5 variant 0.836 (CI: 0.799–0.870). The lowest performing variant was B0 with a PR AUC of 0.740 (CI: 0.695–0.785). The single best combination of body region and projection was achieved by EfficientNet-B5 in the pelvis with a PR AUC of 0.991 (CI: 0.983–0.998). The single worst combination of body region and projection was found for EfficientNet-B0 in the upper arm lateral projection with a PR AUC of 0.561 (CI: 0.505–0.618). The PR AUCs are supplemented in Figure A1 and Figure A2.

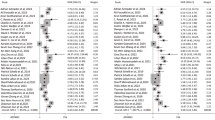

Body regions and X-ray projections

Among all separate body regions and X-ray projections, the pelvis exhibited the highest overall performance metrics with a mean precision of 0.948 ± 0.064, a mean recall of 0.960 ± 0.016, a mean accuracy of 0.948 ± 0.038, and a mean F1 score of 0.952 ± 0.032. The PR AUC was 0.972 (CI: 0.965–0.978) in the pelvis. On the other hand, the upper arm X-rays showed the lowest overall performance, with a precision of 0.741, a recall of 0.512, an accuracy of 0.669, and an F1 score of 0.606 across the EfficientNet variants. The upper arm PR AUC was 0.657 (CI: 0.638–0.678). Figures 2 and 3 give a detailed graphical representation of PR AUC for all 32 X-ray projections, split into three curves for the age groups from 0 to 6 years, from 7 to 12 years, and from 13 to 18 years. PR AUC increased with age in the majority of the X-ray projections.

Matrix 2 of PR AUCs for the remaining upper extremity body regions, pelvis and lower extremity regions, featuring the 3 age groups as separate lines. AUC values are given for each of the age groups. Note that AUC values were commonly lower in younger patients. Baseline is depicted at 0.5 on the y-axis.

Axial skeleton performance metrics recall (p < 0.001), accuracy (p = 0.001), and F1 score (p < 0.001) were statistically significantly superior to those in the appendicular skeleton. Notably, the performance in the long bone regions (clavicle, upper arm, forearm, thigh, lower leg) was markedly lower than in the axial skeleton and joint regions, with a mean PR AUC of 0.711 ± 0.036 compared to 0.833 ± 0.052 (p < 0.001, independent samples t-test). The cause could be asymmetrical aspect ratios in the long bone regions.

Age and age groups

Classification metrics for distinguishing females from males were majorly increased with increasing age, and therefore with increasing age group. Mean precision substantially increased from 0.682 ± 0.033 from 0 to 6 years, over 0.727 ± 0.037 in patients between 7 and 12 years, to 0.800 ± 0.037 in patients aged 13 to 18 years. Mean recall decreased from 0.743 ± 0.088 in 0- to 6-year-olds, over 0.706 ± 0.126 in 7- to 12-year-olds, to 0.703 ± 0.119 in 13- to 18-year-olds. Accuracy showed increases with age group, from 0.694 ± 0.025 in the first group, over 0.720 ± 0.032 in the second group, to 0.756 ± 0.044 in the third group. F1 score also showed increasing performance from 0.711 ± 0.034 in patients aged 0 to 6 years, over 0.717 ± 0.056 in patients between 7 and 12, to 0.749 ± 0.064 in patients from 13 to 18. The corresponding findings are depicted in Figs. 2 and 3, as well as Table 2,which shows performance scores with age, compared between the axial and appendicular skeleton.

Presence of fractures

The sex classification metrics were consistently lower in the presence of fractures in the test set images (compare Fig. 4), on average overall, specifically for precision (normal 0.754 ± 0.086 vs. fracture 0.707 ± 0.073), for recall (normal 0.730 ± 0.108 vs. fracture 0.705 ± 0.104), for accuracy (normal 0.744 ± 0.072 vs. fracture 0.699 ± 0.065), and for F1 score (normal 0.742 ± 0.076 vs. fracture 0.706 ± 0.071). Table 3 depicts further information on the respective metrics. One exception was the pelvis, where no visual and measurable differences were noted in the PR AUCs. Across all 32 X- ray projections, PR AUC values were significantly higher in normal X-rays (p < 0.001, paired samples t-test).

Human ratings and comparison to AI

A total of 7,000 images were randomly assigned from the test set pool with 1,000 samples for each rater. Due to the random selection process and the consecutive presence of duplicates, 5,344 unique test set images were rated by the human experts. The level of AI performance metrics could not be reproduced by the human raters (compare Table 4). Only the pelvis was regularly assigned to the correct biological sex, on average (precision 0.905 ± 0.119, recall 0.809 ± 0.148, accuracy 0.856 ± 0.124, and F1 score 0.854 ± 0.119).

Discussion

We conducted this work to find out whether AI could predict the biological sex in digital X-ray images of various body regions during childhood and adolescence. We used a large dataset of trauma X-rays from a single institution and sampled a representative test set. Prediction results varied in different body regions and age groups. Human raters were not able to reproduce the AI results. Notably, human raters were not trained to estimate sex from pediatric X-rays in advance, as this task is not part of routine radiological practice. Their performance serves as a reference point to illustrate the ability of AI to detect subtle anatomical patterns not typically discernible to experts.

The novelty of our study lies in the systematic processing of an extensive data set of different pediatric X-ray images of the entire body with regard to the correct prediction of biological sex using AI in children and adolescents. Some approaches have been published, e.g. using dental panoramic X-rays, femur, wrist, or chest X-rays18,19,20,21. Unlike previous studies that mainly concentrate on adult patients, we aim to evaluate sex prediction methods applicable to a younger demographic where skeletal sexual dimorphism is less pronounced and more challenging to detect. In addition to utilizing a larger dataset of pediatric radiographs, our study offers a more systematic analysis encompassing detailed considerations of age structure and body regions, as well as inclusion of equal amounts of unremarkable and pathological images featuring fractures. This comprehensive approach allows for a nuanced understanding of how sex estimation accuracy varies across different developmental stages and anatomical regions. We carefully generated the training set as well as the test set in order to minimize potential systematic bias as much as possible.

Our results demonstrated the best classification performance in the adolescent group (13–18 years), likely due to increasing skeletal sex dimorphism with age. Although the overall performance was lower compared to studies on adult populations, the accuracy in individual distinct regions such as the pelvis was equally good. For example, Ulubaba et al. reported classification accuracies of approximately 93% using hand radiographs from adults and a ResNet-50 model22. Similarly, Li et al. (2022) achieved 94.6% accuracy using a fully automated deep learning pipeline on adult proximal femur X-rays20. While both studies used projection radiographs, the comparison remains limited due to the narrower anatomical focus and the mature skeletal features present in adult populations, which likely contribute to higher classification performance. Another comparative study by Cao et al. achieved over 90% accuracy for sex prediction in adults using virtual pelvic CT reconstructions3. However, our performance metrics were calculated across a diverse range of body regions and not limited to high-performing anatomical sites like the pelvis or hand. This difference in methodology and dataset heterogeneity underscores the challenge of applying AI sex classification models to pediatric populations, where skeletal dimorphism is not yet fully developed. Moreover, comparisons to studies based on CT imaging, such as the one by Cao et al.3, should be interpreted with caution, as radiographic projection images (like X-rays) differ fundamentally from 3D volumetric data in terms of both anatomical detail and feature representation.

The compilation of the test set was crucial, especially in the setting of this particular study. Despite the fact that we were able to rely on a large data set, it was not always possible to assign each of the image slots to a sample of the individual age group and criteria (compare Fig. 1). One example of this was the skull scans, which are rarely performed on older children and adolescents. It should also be considered that a transition to adult medicine took place beginning at 16 years. This could be observed consistently across all body regions and led to suitable cases becoming rarer at this age, leading to slots remaining empty. In view of the fact that cases in the first (and in some cases second) year of life were rare, the validity of the study results should be greatest for the age between 2 and 16 years. AI repeatedly produces extraordinary results, but it often remains unclear which properties have been learned by the algorithms. This applies in particular to image classification. Thus, visual explanation is an important aspect when assessing computer vision classification systems like the EfficientNet variants used for this study. In recent years, several methods have been developed and presented to make computer vision results explainable to humans. In this work, we made use of GradCAM++, which can visualize AI activations using saliency maps. We assessed the GradCAM++ outputs of the test set images in terms of special features and patterns. We evaluated and visually assessed the last layer activation, which is crucial for determining the results, on the test set. It is particularly important that the actual image features, such as bones and soft tissue, were assessed, and not labels or side designations. The latter could indicate a systematic error. Figure 5 shows examples of GradCAM++ heat maps of the skull.

Saliency maps of a.p. and lateral head radiographs, (a) in a 2-year-old female, (b) in a 4-year-old female, (c) in an 8-year-old male, (d) in a 10-year-old female, (e) in a 16-years-old male, and (f) in a 17-year-old female. AI activation was more diffuse in a.p. skull projections, whereas it was commonly focused on the occipital region, presumably to check for long head hair. Teeth were blurred due to deidentification.

One counterintuitive finding of our study is the fact that the presence of fractures impaired the performance of sex detection instead of increasing it. We expected that fracture patterns would be recognized by the classification algorithms, because there are known sex differences23,24,25.

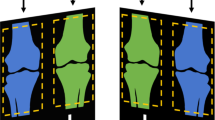

Instead, the presence of fractures significantly reduced the performance of sex detection. We can only speculate about the reasons for this decrease in metrics, potentially caused by soft tissue characteristics being masked after injuries. Another point of interest is the decrease in performance indicators in long tubular bone examinations like clavicle, upper arm, forearm, thigh, or lower leg, which was not readily expected. This could be explained by the fact that these regions’ images feature asymmetrical aspect ratios, which conversely means that a relatively large amount of image information is lost when shrinking the images during network training. EfficientNet input sizes range from 224 × 224 to 600 × 600 px, both substantially lower than the original image sizes. We would also like to note that we would have expected to see a large influence of gonadal protection in pelvic images. Excitingly, the saliency maps showed no signs that the partially present gonadal protectors showed any form of activation. Representative examples are given in Fig. 6. Since the overlays are displayed very bright or almost homogeneously white by the shielding, it is possible that they are ignored by the neural networks, similar to an artificial masking of parts of the image.

Despite the presence of gonadal protection shieldings in parts of the pelvic X-rays, AI did not consider them in saliency maps but routinely focused on the pelvic skeletal configuration to determine sex. (a) 3-year-old female patient, (b) 12-year-old male, (c) 15-year-old female with fracture of the pubic bone on the left side.

One limitation of our study is that the dataset was derived from a single institution, which restricts our ability to directly assess the generalizability of the trained models to external populations or imaging protocols. However, we are confident that the results are likely reproducible across other datasets, particularly because the performance observed in pelvic radiographs aligns with expected outcomes based on known anatomical differences – in some cases also including the presence of testicular shielding. This congruence suggests that the AI models are learning meaningful and generalizable features. Nonetheless, external validation using independent datasets remains essential and should be a key focus of future research to confirm the robustness and applicability of our findings. It should also be noted that model calibration of the different EfficientNet variants could lead to improved performance of some of the classifiers. However, model optimization was not a key aim of this work.

We tried to consider confounding factors, such as the presence of fractures in the images, and balanced the test set as much as possible. We also removed additional studies for training, validation, and testing, in patients sampled to the test set. As our deidentification procedure relied on patient IDs, there could be a potential bias caused by individual samples that got revisions of the patient ID during the years. This scenario is not very likely but cannot be excluded entirely. We therefore cannot rule out the possibility that some individuals in the test set and training set may overlap. This factor would lead to overestimated performance metrics in the test set. Another cause of bias could be the presence of identical twins, which could potentially be sampled in both training (+ validation) and test sets separately. At a rate of monozygotic twins of approximately 4 per 1000 births in the literature26, an influence on the study results is possible, although the impact can hardly be estimated. Due to the testicular shielding, a bias was introduced in the pelvic examinations. We analyzed the GradCAM++ activation maps to see whether this influenced the AI decision more than the bony landmarks but could not visually confirm substantial influence on the network activations.

Conclusion

We demonstrated that AI can predict biological sex in X-rays of various body regions in childhood and adolescence with more than random odds and more reliably than human experts. An age-dependent progression of the classification results was noted, with better results in the axial compared to the appendicular skeleton. Prediction performance was best in the pelvis and worst in long tubular bone regions like the forearm.

Data availability

In our commitment to transparency and reproducibility, we have updated our data availability statement to note that the code used for analysis is made available in the Github repository https://github.com/tschauner-s/pediatric_gender_classification. Please note that we have legit concern for publicly releasing the model weights. There have been issues like model inversion attacks and possible other yet unknown attack vectors and we cannot reliably ascertain patient anonymity in this large dataset. We released large image datasets in the past https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-022-01328-z, but only after anonymity was granted by enormous human effort. We cannot offer that amount of human effort in the huge dataset this work is based upon.

References

Salehi, A. W. et al. A study of CNN and transfer learning in medical imaging: Advantages, challenges, future scope. Sustainability. 15, 5930 (2023). https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/15/7/5930.

Thomas, L. B., Mastorides, S. M., Viswanadhan, N. A., Jakey, C. E. & Borkowski, A. A. Artificial intelligence: review of current and future applications in medicine. Fed. Pract. 38, 527–538 (2021).

Cao, Y. et al. Use of deep learning in forensic sex estimation of virtual pelvic models from the Han population. Forensic Sci. Res. 7, 540–549 (2022).

Larrazabal, A. J., Nieto, N., Peterson, V., Milone, D. H. & Ferrante, E. Gender imbalance in medical imaging datasets produces biased classifiers for computer-aided diagnosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 117, 12592–12594 (2020).

Yang, C. Y. et al. Using deep neural networks for predicting age and sex in healthy adult chest radiographs. J. Clin. Med. 10 (2021).

Bradski, G. The OpenCV Library (Dr Dobb’s Journal of Software Tools, 2000).

Mason, D. SU-E-T-33: Pydicom: an open source DICOM library. Med. Phys. 38, 3493–3493 (2011).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–28301532 (2011).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. PMLR 6105–6114%@ 2640–3498 (2019).

Ali, K., Shaikh, Z. A., Khan, A. A. & Laghari, A. A. Multiclass skin cancer classification using EfficientNets–a first step towards preventing skin cancer. Neurosci. Inf. 2, 100034102772–100034105286 (2022).

Latha, M. et al. Revolutionizing breast ultrasound diagnostics with EfficientNet-B7 and explainable AI. BMC Med. Imaging. 24, 2301471–2302342 (2024).

Raza, R. et al. Lung-EffNet: Lung cancer classification using EfficientNet from CT-scan images. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 126, 106902%@ 100952–101976 (2023).

Howard, J. & Gugger, S. Fastai: a layered API for deep learning. Information 11, 2078–2489 (2020).

Sekachev, B. et al. Chenuet, a andre, telenachos, A. Melnikov, J Kim, L Ilouz, N Glazov, Priya4607, S Yonekura, vugia truong, zliang7, lizhming, and T Truong,opencv/cvat: v1 1 (2020).

Krawczyk, B. Learning from imbalanced data: open challenges and future directions. Progress Artif. Intell. 5, 221–2322192 (2016).

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90–951521 (2007).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-cam: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. 618–626 (2017).

Ciconelle, A. C. M. et al. Deep learning for sex determination: analyzing over 200,000 panoramic radiographs. J. Forensic Sci. 68, 2057–20640022 (2023).

Li, D., Lin, C. T., Sulam, J. & Yi, P. H. Deep learning prediction of sex on chest radiographs: a potential contributor to biased algorithms. Emerg. Radiol. 29, 365–3701070 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. A fully automated sex estimation for proximal femur X-ray images through deep learning detection and classification. Leg. Med. 57, 102056101344–102056106223 (2022).

Yune, S. et al. Beyond human perception: sexual dimorphism in hand and wrist radiographs is discernible by a deep learning model. J. Digit. Imaging. 32, 665–6710897 (2019).

Ulubaba, H. E., Atik, I., Ciftci, R., Eken, O. & Aldhahi, M. I. Deep learning for gender estimation using hand radiographs: a comparative evaluation of CNN models. BMC Med. Imaging. 25, 260 (2025).

Curtis, E. M. et al. Epidemiology of fractures in the United Kingdom 1988–2012: variation with age, sex, geography, ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Bone 87, 19–26 (2016). 8756 – 3282.

Hedström, E. M., Svensson, O., Bergström, U. & Michno, P. Epidemiology of fractures in children and adolescents: increased incidence over the past decade: a population-based study from Northern Sweden. Acta Orthop. 81, 148–1531745 (2010).

Koga, H. et al. Increasing incidence of fracture and its sex difference in school children: 20 year longitudinal study based on school health statistic in Japan. J. Orthop. Sci. 23, 151–1550949 (2018).

Vitthala, S., Gelbaya, T. A., Brison, D. R., Fitzgerald, C. T. & Nardo, L. G. The risk of monozygotic twins after assisted reproductive technology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 15, 45–551460 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank the numerous annotators who worked on parts of the used dataset over the last few years.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.J. - Investigation, Data curation, Writing - Original Draft, Formal analysis; M. S. -Data curation, Investigation; N. S. – Investigation; Writing – review and editingH. E. – Supervision, ResourcesG. S. – Supervision, InvestigationH. T. - SupervisionM. Z. - ValidationF. H. - Software, Visualization, Data curationS. T. - Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing, Funding acquisition –All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Graz, Neue Stiftingtalstraße 6 - West, P 08, 8010 Graz (No. 31–108 ex 18/19). Informed patient or legal representative consent was waived. Informed consent was obtained from all participating raters prior to their involvement in the study.

All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Janisch, M., Scherkl, M., Stranger, N. et al. Predicting biological sex in pediatric skeleton X-rays using artificial intelligence. Sci Rep 15, 44366 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28197-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28197-x