Abstract

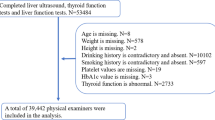

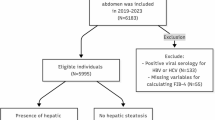

Metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is a common metabolic disorder intricately linked to diabetes and thyroid dysfunction. Hypothyroidism, characterized by elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), may disrupt lipid metabolism and exacerbate insulin resistance, contributing to MAFLD progression. Investigating the combined impact of diabetes and thyroid dysfunction on fibrosis and steatosis stages in MAFLD is essential for optimizing disease management. This prospective cross-sectional study was conducted at Suez General Hospital from March to September 2024 and included 400 patients with MAFLD . Participants were stratified into four groups: Group A: 100 diabetic patients without thyroid dysfunction; Group B: 100 non-diabetic patients without thyroid dysfunction; Group C: 100 diabetic patients with thyroid dysfunction; and Group D: 100 non-diabetic patients with thyroid dysfunction. Clinical assessment, laboratory investigations, fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores, and abdominal ultrasonography were performed for all participants, and transient elastography (FibroScan®) for those with FIB-4 scores > 3.25. Significant differences were observed in the distribution of body mass index (BMI), liver enzymes, and fibrosis stages across the groups (P < 0.001, for all). Group C exhibited the highest prevalence of advanced fibrosis (F2–F3), while severe steatosis (S3) was predominant in Group D. Hypothyroidism and subclinical hypothyroidism were associated with elevated FIB-4 scores and advanced steatosis (p = 0.033), highlighting the impact of thyroid dysfunction on MAFLD progression. Diabetes and thyroid dysfunction can exacerbate MAFLD severity, emphasizing the need for integrated management strategies targeting these comorbidities to mitigate fibrosis and steatosis progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) and thyroid disease are highly prevalent globally and are reported to be present as comorbid conditions in up to 22.4% of patients with MAFLD. Primary hypothyroidism, henceforth referred to as hypothyroidism, is a disease characterized by a TSH concentration above the reference range; it can either be overt or subclinical1.

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is the most frequent cause of chronic liver disease that affects millions of people worldwide. Genetics, obesity, unhealthy lifestyle, and other metabolic risk factors could be responsible for the burgeoning evolution, increased prevalence, and incidence of MAFLD2.

MAFLD encompasses a wide range of liver conditions from simple steatosis/ metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) to MASH (Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis), cirrhosis, and finally, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)3. Considering the common and possible evolution to MASH and cirrhosis, MAFLD has become one of the main causes of liver transplantation4.

Hypothyroidism continues to remain a global problem with increased incidence among the adult and newborn population, and illustrates decreased metabolic rate determined by hypo secretion of TSH from the thyroid gland5. Studies have shown that patients with over ten years of thyroid dysfunction have significantly higher chances of developing HCC6, and that in subjects with MASH and chronic hepatitis B infection, a higher thyroid dysfunction was found compared to that of the control group7. The hypothalamic pituitary thyroid axis plays an essential role in many metabolic pathways, especially those involving lipids and carbohydrates. MAFLD has been described as the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome. Therefore, a relationship between hypothyroidism and MAFLD has long been hypothesized and studied8.

Because of its importance in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, the involvement of thyroid dysfunction in the pathogenesis of MAFLD seems plausible. Many mechanisms have been implicated in this relationship9.

Hyperthyroidism seems to have a protective effect on the incidence of MAFLD. A retrospective case-control study included adult patients (≥ 18 years) with an initial diagnosis of NAFLD in 1262 general practices in Germany found that hyperthyroidism had a protective effect on the risk of incident MAFLD10.

Aim of the work

The study aims to explore the potential role of thyroid dysfunction in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease pathogenesis as a risk factor for each other.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

The study was carried out in Suez general hospital from march 2024 to September 2024. included 400 patients with thyroid dysfunction divided as follows:

Sample size calculation was based on mean difference of % connection between thyroid dysfunction and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as a risk factor for each other retrieved from previous research. Using G power program version 3.1.9.7 to calculate sample size based on expected difference of 32.6%, using 2-tailed test, α error = 0.05 and power = 80.0%, the total calculated sample size will be 50 in each group at least.

Group A

will include 100 DM patients (50 male and 50 female) without thyroid dysfunction and with fatty liver. This group will be divided into 2 subgroups according to FIB-4scor less than 1.45 or more than 3.25.

Group B

include 100 non DM patients (50 male and 50 female) without thyroid dysfunction and with fatty liver.

Group C

include 100 DM patients (50 male and 50 female) with thyroid dysfunction and fatty liver.

Group D

include 100 non DM patients (50 male and 50 female) with thyroid dysfunction and fatty liver.

Methodology:

- This study adhered to all relevant ethical guidelines and regulations. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Suez University. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

-

(1)

Full history taking: from all patients and include

-

a.

Age, sex, smoking, consumption of alcohol and coffee and drug history.

-

b.

History of diabetes mellitus (including duration, symptoms, complications, medications such as oral hypoglycemic drugs and insulin).

-

c.

History of other medical conditions as hypertension, liver, autoimmune disease and renal disease.

-

a.

-

(2)

Clinical examinations: for all patient with emphasis on vital signs, waist circumference, body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) and abdominal examination.

-

(3)

Investigations:

The following laboratory investigations were done;

-

1.

Routine laboratory investigations including:

-

CBC. Hemoglobin concentration was measured with an ADVIA 120 automated hematology analyzer (Bayer, NY, USA).”

-

ESR.

-

Liver enzymes (ALT, AST) and kidney function (urea, creatinine).

-

Complete lipid profile.

-

Venous blood samples (10 mL) were obtained from subjects after an overnight fast (≥ 12 h). Blood was allowed to clot at room temperature for 15 min and subsequently centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 3 min. Total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglyceride, ALT, AST, blood urea and creatinine levels were determined enzymatically using an automated chemistry analyzer (Toshiba TBA-120 FR, Toshiba Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan).

-

2.

Glycemic profile including:

-

Fasting blood glucose after 8 h fasting, Three milliliters of venous blood were collected in a plain tube and allowed to clot at room temperature for 15 min. Subsequently, the samples were centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 3 min rpm then glucose level was measured in the separated serum using an automated chemistry analyzer (Toshiba TBA-120 FR, Toshiba Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan).

-

Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c). EDTA blood sample for HbA1c using high-performance liquid chromatography method for hemoglobin A1c.

-

Principle of HbA1c analyses

HbA1c levels were determined by cation-exchange chromatography after hemolysis and removal of interfering substances. The percentage of HbA1c was calculated by comparing the eluted HbA1c absorbance at 415 nm to the total hemoglobin absorbance.

Assay process

-

A.

Preparation of hemolysed solution:

Fifty µl of blood was pipetted into test tube and then 450 µ of potassium biphthalate was added, mixed gently and incubated at18 22 C0 for 10–15 min.

-

B.

Chromatographic separation :

-

1.

Fifty µl of hemolysed solution was added to the column and after 3 min any eventual eluate was discarded.

-

2.

Two ml buffer was pipetted into the column and the eluate was discarded.

-

3.

The column was positioned over a test tube, and 2 mL of buffer was added to elute the HbA1c fraction.

-

4.

The obtained eluate was mixed and the HbA1c fraction absorbance was read at 415 nm against distilled water (AHbA1c).

-

5.

Preparation of total Hb:

-

1.

One Handred µ of hemolysed solution was pipetted into a test tube and 12 ml distilled water was added, mixed and the total Hb (A Hb total) absorbance was read at 415 nm using distilled water as a blank.

Calculation: (AHbA1c) / (3×A Hb total) × 100 = %HbA1c.

-

(4)

FIB-4 score was calculated for all patients.

-

(5)

Abdominal ultrasonography and fibro-scan: Abdominal ultrasonography was done for all patients in the study and fibro-scan was done for patients with FIB-4scor more than 3.25.

Results

The study was conducted in Suez General Hospital from March 2024 to September 2024 and included 400 patients with fatty liver disease, The study population consisted of 200 females (50%) and 200 males (50%) with a median age of 40 (18–59) years. Half of the participants had diabetes mellitus, while the other half did not. About (46.3%) had thyroid dysfunction, and 3.8% had subclinical hypothyroidism. The majority of patients (88%) had hypertension. The distribution of body mass index (BMI) categories was as follows: 28% were underweight, 37.7% were normal weight, 23.3% were overweight, and 11% were obese. All patients had evidence of fatty liver on ultrasound. Regarding glycemic control, 50% of diabetic patients had normal HbA1c levels, 28% were on target, and 22% had elevated levels. A significant proportion of patients had elevated triglycerides (75%) and cholesterol levels (75%). The distribution of FIB-4 scores was as follows: 30.5% low risk, 47.8% intermediate risk, and 21.8% high risk. Fibro-scan revealed varying degrees of steatosis and fibrosis, with S2 being the most common stage of steatosis (67.8%) and F2 being the most common stage of fibrosis (46.1%) (Table 1). The mean AST level was 42 ± 5 U/L, the mean ALT level was 33 ± 8 U/L. The mean platelet count was 190 ± 95 × 10^9/L. The mean hemoglobin level was 13 ± 2 g/dL (Table 2).

Comparison between the four groups regarding different variables

Metabolic dysregulation and glycemic profiles

Ultrasound findings confirmed a 100% prevalence of fatty liver among the study population, aligning with the diagnosis of (MAFLD). Laboratory assessments revealed that 75% of patients had elevated triglyceride and cholesterol levels, indicating a high prevalence of dyslipidemia. Among diabetic patients, glycemic control was variable, with 50% having normal HbA1c levels, 28% achieving target levels, and 22% showing elevated HbA1c levels. A statistically significant difference in diabetes prevalence was observed between the study groups (P < 0.001). Groups A and C (diabetic patients) exhibited significantly higher proportions of elevated HbA1c levels compared to Groups B and D (non-diabetic patients), highlighting the metabolic burden in diabetic cohorts.

Fibrosis and steatosis

Significant differences were observed in the distribution of fibrosis and steatosis stages between the four groups. Group C had a higher proportion of patients with advanced fibrosis (F2 and F3) compared to the other groups. Group D had a higher proportion of patients with severe steatosis (S3) compared to the other groups.

Body mass index

A significant difference was observed in the distribution of body mass index (BMI) categories between the four groups (P value < 0.001). Group B had a higher proportion of patients with BMI < 20 and BMI 20–25 compared to the other groups.

Hypertension

No significant difference was observed in the prevalence of hypertension between the four groups (P value = 0.723) (Table 3).

Age and Laboratory Parameter Comparisons Across Groups.

No significant difference in mean age was observed among the four groups (P = 0.918). However, notable variations were identified in several laboratory parameters. Liver function tests revealed significant differences in mean AST and ALT levels between the groups (P < 0.001), with Group C (diabetic patients with thyroid dysfunction) exhibiting the highest levels. Platelet counts also varied significantly across the groups (P < 0.001), with Group C showing significantly lower mean platelet counts compared to the other groups, indicating potential platelet-related abnormalities in this group. Conversely, no significant difference was observed in mean hemoglobin levels between the groups (P = 1.000) (Table 4).

By investigating the relation between gender and different image studies, we found the following: FIB-4 Score: No significant difference was observed in the distribution of FIB-4 scores between males and females (p = 0.428). Fibro-scan Steatosis: No significant difference was observed in the distribution of steatosis stages between males and females (p = 0.664). Fibro-scan Fibrosis: No significant difference was observed in the distribution of fibrosis stages between males and females (p = 0.754) (Table 5).

Regarding the relation between hypothyroidism and different image studies: 1- FIB-4 Score: A significant difference was observed in the distribution of FIB-4 scores between patients with and without hypothyroidism (p < 0.001). Patients with hypothyroidism had a higher proportion of intermediate and high-risk FIB-4 scores. 2- Fibro-scan Steatosis: A significant difference was observed in the distribution of steatosis stages between patients with and without hypothyroidism. Patients with hypothyroidism had a higher proportion of advanced steatosis (S2 and S3). 3- Fibro-scan Fibrosis: No significant difference was observed in the distribution of fibrosis stages between patients with and without hypothyroidism (p = 0.352) (Table 6).

Regarding the relation between Subclinical Hypothyroidism and different image studies: 1- FIB-4 Score: A significant difference was observed in the distribution of FIB-4 scores between patients with and without subclinical hypothyroidism (p = 0.033). Patients with subclinical hypothyroidism had a higher proportion of intermediate and high-risk FIB-4 scores. 2- Fibro-scan Steatosis: No significant difference was observed in the distribution of steatosis stages between patients with and without subclinical hypothyroidism (p = 0.615). However, it’s worth noting that the sample size for patients with subclinical hypothyroidism is small, which may limit the statistical power to detect significant differences. 3- Fibro-scan Fibrosis: A significant difference was observed in the distribution of fibrosis stages between patients with and without subclinical hypothyroidism (p = 0.085). Patients with subclinical hypothyroidism had a higher proportion of advanced fibrosis (F2 and F3) (Table 7).

Regarding the relation between BMI and different image studies: 1- FIB-4 Score: A significant difference was observed in the distribution of FIB-4 scores across different BMI categories (p < 0.001). As BMI increased, the proportion of patients with higher FIB-4 scores (intermediate and high-risk) also increased. 2- Fibro-scan Steatosis: A significant difference was observed in the distribution of steatosis stages across different BMI categories (p = 0.078). As BMI increased, the proportion of patients with advanced steatosis (S2 and S3) also increased. 3- Fibro-scan Fibrosis: A significant difference was observed in the distribution of fibrosis stages across different BMI categories (p = 0.179). As BMI increased, the proportion of patients with advanced fibrosis (F2, F3, and F4) also increased (Table 8).

Discussion

Metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is the leading cause of chronic liver diseases worldwide and a nomenclature that captures fatty liver disease (FLD) with metabolic dysfunctions11.

Thyroid function has been proposed as one of the most important risk factors for its prominent effects on hepatic fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis. Normal thyroid function is essential for maintaining liver metabolism, while thyroid disorders affect the clinical progression of liver disease12.

In our study, about (46.3%) had thyroid dysfunction, and 3.8% had subclinical hypothyroidism. Similar to our findings, Fan et al.13 study included 14,789 patients were strict-normal thyroid function, among them 29.3% had low-normal thyroid function, and 5.6% had subclinical hypothyroidism.

The distribution of BMI categories was as follows: 28% were underweight, 37.7% were normal weight, 23.3% were overweight, and 11% were obese. All patients had evidence of fatty liver on ultrasound.

Regarding glycemic control, 50% of diabetic patients had normal HbA1c levels, 28% were on target, and 22% had elevated levels. A significant proportion of patients had elevated triglycerides (75%) and cholesterol levels (75%). The distribution of FIB-4 scores was as follows: 30.5% low risk, 47.8% intermediate risk, and 21.8% high risk. Fibro-scan revealed varying degrees of steatosis and fibrosis, with S2 being the most common stage of steatosis (67.8%) and F2 being the most common stage of fibrosis (46.1%).

However, Zambrano-Huailla et al.14 found that the distribution of fibrosis stages among the sample population was as follows: F0 (45%), F1 (27%), F2 (8%), F3 (16%) and F4 (4%).

A significant difference was observed in the distribution of BMI categories between the four groups. Group B had a higher proportion of patients with BMI < 20 and BMI 20–25 compared to the other groups.

A significant difference was observed in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus between the four groups. Groups A and C, consisting of diabetic patients, had significantly higher proportions of elevated HbA1c levels and higher triglyceride and cholesterol levels compared to Groups B and D.

In alignment with our data, Zhang and colleagues15 estimated the prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) and noted that the prevalence of MAFLD was significantly higher in patients with T2DM than in subjects without diabetes.

All patients in all groups had evidence of fatty liver on ultrasound. Significant differences were observed in the distribution of fibrosis and steatosis stages between the four groups. Group C had a higher proportion of patients with advanced fibrosis (F2 and F3) compared to the other groups. Group D had a higher proportion of patients with severe steatosis (S3) compared to the other groups.

Significant differences were observed in the mean AST and ALT levels between the four groups; group C had significantly higher mean AST and ALT levels compared to the other groups. Also, significant differences were observed in the mean platelet count between the four groups; group C had significantly lower mean platelet count compared to the other groups.

No significant difference was observed in the distribution of FIB-4 scores, the distribution of steatosis stages, and the distribution of fibrosis stages between males and females.

However, Halaoui et al.16 assessed the gender impact on liver status in NAFLD patients younger than 50 years and stated that fibrosis score could predict liver status in males but not in females.

On the contrary, Balakrishnan et al.17 noted that the risk of advanced fibrosis (RR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.36–1.80; I2 = 0) was substantially higher in women in study populations with average ages of 50 years and older; sex differences in MASH and advanced fibrosis were attenuated in younger populations. They concluded that once MAFLD is established, women have a higher risk of advanced fibrosis than men, especially after age 50 years.

A significant difference was observed in the distribution of FIB-4 scores and the distribution of steatosis stages, between patients with and without hypothyroidism; patients with hypothyroidism had a higher proportion of intermediate and high-risk FIB-4 scores and advanced steatosis (S2 and S3), but no significant difference was observed in the distribution of fibrosis stages.

Our findings can be explained by the fact that thyroid hormones regulate many metabolic activities in the liver by promoting the export and oxidation of lipids, as well as de novo lipogenesis. They also control hepatic insulin sensitivity and suppress hepatic gluconeogenesis. Because of its importance in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, the involvement of thyroid dysfunction in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and MAFLD seems plausible18.

Similarly, the findings from a previous review by Lugari et al.19 support a significant association between primary hypothyroidism and risk of development and progression of fatty liver disease.

In difference, a previous study by D’Ambrosio et al.20 demonstrated that rates of hypothyroidism were similar independently of significant fibrosis (p = 0.21) or steatosis (p = 0.75), this difference may be due to that investigated the association between hypothyroidism and NAFLD histological features potentially associated with progressive liver disease, while our study focused into MAFLD.

A significant difference was observed in the distribution of FIB-4 scores and the distribution of fibrosis stages between patients with and without subclinical hypothyroidism. Patients with subclinical hypothyroidism had a higher proportion of intermediate and high-risk FIB-4 scores and advanced fibrosis (F2 and F3), but no significant difference was observed in the distribution of steatosis stages.

A previous article by Fan et al.13 supported our results as they conducted a multivariable regression model adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension showed low-normal thyroid function increased the risk of advanced fibrosis in patients with MAFLD (FIB-4 > 2.67: OR = 1.41, 95% CI 1.02–1.93; NFS > 0.676: OR = 1.72, 95% CI 1.08–2.72).

A significant difference was observed in the distribution of FIB-4 scores across different BMI categories, as BMI increased, the proportion of patients with higher FIB-4 scores (intermediate and high-risk) also increased.

A significant difference was observed in the distribution of steatosis stages across different BMI categories. As BMI increased, the proportion of patients with advanced steatosis (S2 and S3) also increased. A significant difference was observed in the distribution of fibrosis stages across different BMI categories. As BMI increased, the proportion of patients with advanced fibrosis (F2, F3, and F4) also increased.

This results were in agreement with Gopalakrishna et al.21 who stated that, compared to patients with BMI < 25 kg/m2, the adjusted OR (95% CI) of having a higher fibrosis stage was 1.82 (0.61–5.44), 5.93 (2.05–17.13), and 8.56 (2.51–29.17) for patients with BMI of 25 to < 30, 30 to < 40, and ≥ 40 respectively; so, increasing BMI increases the odds of having a higher fibrosis stage.

Additionally, a meta-analysis by Lu et al.22 indicated that, obesity (according to ethnic-specific BMI cut-off points to define obesity) could predict a worse long-term prognosis, but they included NAFLD patients.

Conclusion

This study highlights the high prevalence and progression of MAFLD in patients with underlying metabolic risk factors. The strong associations observed between diabetes, thyroid dysfunction, and elevated BMI with advanced liver fibrosis and steatosis underscore the need for a comprehensive and integrated approach to patient care. Early identification and management of these metabolic risk factors are crucial to preventing the progression of liver disease and improving long-term patient outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Tanase, D. M. et al. Hypothyroidism-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (Hin): Mechanisms and emerging therapeutic options. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(16),1–29. MDPI AG. (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21165927(

Janota, B., Szczepańska, E., Adamek, B. & Janczewska, E. Hypothyroidism and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A coincidence or a causal relationship? World J. Hepatol. 15 (5), 641–648. https://doi.org/10.4254/WJH.V15.I5.641 (2023).

Vidal-Cevallos, P., Murúa-Beltrán Gall, S., Uribe, M. & Chávez-Tapia, N. C. Understanding the relationship between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and thyroid disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(19) https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241914605( (2023). InMultidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI).

Fan, H. et al. Low thyroid function is associated with an increased risk of advanced fibrosis in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02612-3(2023).

Almomani, A. et al. Prevalence of hypothyroidism and effect of thyroid hormone replacement therapy in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A population-based study. World J. Hepatol. 14 (3), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v14.i3.551 (2022).

Lonardo, A. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Evolving paradigms. World J. Gastroenterol. 23(36), 6571–6592. Baishideng Publishing Group Co. (2017). https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i36.6571

Liu, L. et al. Thyroid-stimulating hormone is associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Medicine 98 (46), e17945. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000017945 (2019).

Gor, R. et al. Unraveling the role of hypothyroidism in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease pathogenesis: Correlations, conflicts, and the current stand. Cureus https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.14858 (2021).

Krashin, E., Piekiełko-Witkowska, A., Ellis, M. & Ashur-Fabian, O. Thyroid hormones and cancer: A comprehensive review of preclinical and clinical studies. Front. Endocrinol. 10(FEB) (2019). https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00059

Labenz, C., Kostev, K., Armandi, A., Galle, P. R. & Schattenberg, J. M. Impact of thyroid disorders on the incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Germany. United European Gastroenterol. J. 9(7), 829–836 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/ueg2.12124. Epub 2021 Jul 20. PMID: 34288580; PMCID: PMC8435260.(2021).

Le, M. et al. NAFLD Prevalence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20, 2809–2017 (2019).

Ritter, M. J., Amano, I. & Hollenberg, A. Thyroid hormone signaling and the liver. Hepatology 72, 742–752 (2020).

Fan, H. et al. Low thyroid function is associated with an increased risk of advanced fibrosis in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 23, 30–40 (2023).

Zambrano, R. et al. Diagnostic performance of three non-invasive fibrosis scores (Hepamet, FIB-4, NAFLD fibrosis score) in NAFLD patients from a mixed Latin American population. Ann Hepatol. 19, 622–626 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Correlation between thyroid function, sensitivity to thyroid hormones and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in euthyroid subjects with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Endocrine 80, 366–379 (2023). 2023.

Halaoui, A., Ali, A., Habib, S., Kanso, M. & Daniel, F. Mukher,j. Gender differences in liver fibrosis among patients younger than 50 years: A retrospective cohort study. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 44, 733–738 (2020).

Balakrishnan, M. et al. Women have a lower risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease but a higher risk of progression vs men: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 19, 61–71 (2021).

Vidal, P., Murúa, G., Uribe, M. & Chávez, N. Understanding the relationship between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and thyroid disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 24–36 (2023). (2023).

Lugari, S., Mantovani, A., Nascimbeni, F. & Lonardo, A. Hypothyroidism and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease - a chance association? Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 41, 25–30 (2018).

D’Ambrosio, R. et al. The relationship between liver histology and thyroid function tests in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). PLoS ONE. 16, 14–20 (2021).

Gopalakrishna, H., Fashanu, O., Nair, G. & Ravendhran, N. Association between body mass index and liver stiffness measurement using transient elastography in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a hepatology clinic: A cross sectional study. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8, 10–20(2023).

Lu, F. B. et al. The relationship between obesity and the severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 491–502 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all the authors for their great contribution to this work to be done perfectly.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). We declare that this study did not have any source of funding from any institution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mohamed, W. and maysa, I. wrote the main manuscript text and Eman almnakhly and nessren mohamed prepared tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saleh, M.W., Farghly, M.I., Elsebaie, E. et al. Impact of thyroid dysfunction and diabetes on fibrosis and steatosis stages in metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease. Sci Rep 15, 43840 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28232-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28232-x