Abstract

Drought stress is one of the major abiotic factors that severely limits global cotton yield by disrupting essential morpho-physiological and biochemical functions. In this study, forty genetically diverse cotton genotypes were evaluated under three irrigation levels: control (100% field capacity), moderate (60% FC), and severe drought (40% FC), during the flowering stage in a controlled glasshouse environment. Increasing drought intensity led to a gradual decline in growth and physiological attributes. Severe stress reduced shoot and root lengths by 61% and 52%, respectively, compared with the control. Similarly, the photosynthetic rate and relative water content decreased by 60% and 32%. Conversely, stress-induced biochemical responses intensified, with proline content rising by 57% and superoxide dismutase activity increasing 2.3-fold under severe drought, reflecting enhanced osmotic adjustment and antioxidant defense. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) helps to identify the variability patterns among all the analyzed traits, while Pearson correlation analysis and heatmap analysis are useful for evaluating the positive and negative relationships between the studied attributes and for visualizing the clustering patterns of the cotton accessions. In addition, the multi-trait genotype–ideotype distance index (MGIDI) identified genotypes G2 (IR-14), G8 (N-221), G9 (N-444), G17 (FH-154), G20 (FH-492), and G25 (FH-540) as highly drought-tolerant. These genotypes maintained superior photosynthetic efficiency, antioxidant activity, and osmolyte accumulation under stress. The combined assessment of morpho-physiological and biochemical traits effectively distinguished drought-resilient genotypes, offering valuable guidance for breeding programs targeting enhanced cotton productivity in arid and water-deficient regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate-induced abiotic stresses, specifically drought, are increasingly recognized as critical threats to global agriculture, limiting crop productivity and compromising food security1. This challenge is exacerbated by erratic rainfall patterns, depleting groundwater resources, and rapid population expansion. Simultaneously, anthropogenic activities such as land degradation, urban encroachment, salinization, and desertification accelerate climate variability, with global temperatures projected to rise by approximately 2 °C by the century’s end2. Among various environmental constraints, drought stress exerts the most severe impact on crop yield, responsible for yield losses of up to 30–90% in key agricultural species3. Currently, around 24 million people are affected by acute water shortages, a figure expected to surge to nearly 700 million by 20304,5.

In Pakistan, cotton (Gossypium spp.) a vital contributor to both the national economy and international textile markets is particularly sensitive to water scarcity6. The crop cultivation area is over 2.42 million hectares with a production of 10.22 million bales in 2023. Cotton contributes approximately 8.2% to the country’s agricultural GDP, 3.2% to its total GDP, and nearly 60% of its foreign exchange earnings7. However, a projected 30–35% reduction in water availability, as reported by the Indus River System Authority (IRSA), poses significant risks to Pakistan’s cotton agroecosystems8.

Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), a moderately drought-tolerant glycophyte of the Malvaceae family, is cultivated for its high-value fiber, oil, and feed9. Nevertheless, prolonged drought significantly diminishes boll formation and fiber yield10. Previous studies have indicated that each 1 °C increase in maximum daily temperature could result in a 110 kg ha−1 decline in cotton yield11, with total drought-induced losses reaching as high as 34%, depending on the severity and timing of stress12. Water deficits, particularly during the reproductive phase, disrupt root development, limit cottonseed formation, and increase vulnerability to pest attacks. The flowering stage, being highly susceptible to moisture limitations, often suffers from pollen sterility and ovule abortion, leading to reduced boll retention and lower lint yield13.

The inherent genetic diversity in cotton provides a foundation for varied morpho-physiological and biochemical strategies to mitigate drought stress14. Physiological attributes such as stomatal conductance (gs), transpiration rate (E), and photosynthetic efficiency (Pn) are critical indicators of drought response, yet are often suppressed under severe moisture stress due to structural and metabolic changes15. Growth-related traits like shoot elongation, biomass accumulation, and leaf expansion are similarly compromised. Maintenance of cellular membrane stability and higher relative water content (RWC) under water deficit are indicative of superior drought tolerance16.

At the cellular level, drought stress triggers excessive accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide anions (O2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (OH•), resulting from disruptions in electron transport chains within chloroplasts, mitochondria, and peroxisomes17,18. The plant’s antioxidant defense system, comprising enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and peroxidases (POD), plays a key role in ROS detoxification, maintaining redox balance, and protecting cellular integrity under drought. Tolerant genotypes typically show superior regulation of antioxidant activity, effectively minimizing oxidative damage compared to susceptible cultivars19.

Osmoregulation represents another vital adaptive strategy, where the synthesis of compatible solutes such as proline, total soluble sugars (TSS), free amino acids (TFA), polyols, and phenolic compounds supports osmotic adjustment, cellular turgor maintenance, and stabilization of macromolecular structures under drought stress10,20. This biochemical adaptation often operates synergistically with antioxidant defenses to counteract both dehydration and oxidative damage21. Conversely, drought-sensitive genotypes typically exhibit inadequate osmolyte accumulation, leading to cellular dehydration and metabolic failure22. The ability to sustain osmotic balance, relative water content, and proline accumulation allows drought-tolerant genotypes to preserve physiological processes and biomass production under water deficit conditions23.

Despite extensive studies on cotton drought tolerance, previous research has predominantly concentrated on the seedling stage, neglecting the critical reproductive stage where yield-determining processes are most vulnerable to water deficit. Additionally, comprehensive integration of morpho-physiological and biochemical markers for genotype differentiation remains sparsely investigated. This study, therefore, provides a novel integrative assessment of drought tolerance in forty genetically diverse cotton genotypes, using advanced morpho-physiological and biochemical markers specifically evaluated during the early reproductive stage. By incorporating the multi-trait genotype–ideotype distance index (MGIDI), this research enhances the precision of genotype screening and elucidates coordinated physiological and biochemical mechanisms underpinning drought resilience. The findings offer valuable genetic resources for breeding climate-resilient cotton varieties, contributing innovative strategies for sustaining cotton production under increasing water scarcity.

Materials and methods

This study was designed to evaluate the impacts of drought stress on forty genetically diverse cotton genotypes procured from different research institutions across Pakistan, including the Nuclear Institute for Agriculture and Biology (NIAB), National Institute for Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering (NIBGE), Cotton Research Institute (CRI), Ayub Agriculture Research Institute (AARI), Central Cotton Research Institute (CCRI), and the University of Agriculture Faisalabad (Table 1). The experiment was conducted using a completely randomized design (CRD), where pots were randomly assigned to genotype-treatment combinations through a computer-generated sequence to eliminate bias in treatment allocation across the greenhouse. Environmental gradients, such as temperature, humidity, and light, were controlled to ensure uniform conditions throughout the experiment. Position effects were mitigated by evenly distributing pots across the greenhouse, with randomization preventing any systematic placement. CRD design was chosen over a randomized complete block design due to the limited number of experimental units and the absence of clear block effects, making CRD the most efficient method for unbiased treatment distribution. Three replications per genotype-treatment combination were used to ensure statistical robustness. Prior to sowing, soil analyses were performed to characterize the soil field capacity (FC) and physio-chemical characteristics. Parameters assessed included elemental composition, pH, electrical conductivity (EC), soil nutrient concentration, soil texture, and concentration of organic matter, which critically influence plant–soil–water interactions under different drought stress regimes. A complete summary of these soil characteristics is presented in Table 2.

Drought stress treatments

Irrigation regimes were meticulously regulated to establish three distinct drought stress treatments, including normal condition (100% FC), moderate drought stress (60% FC), and severe drought stress (40% FC). The study enabled precise monitoring of soil moisture dynamics and the corresponding physiological and biochemical responses of the plants. Additionally, the study primarily focused on the early flowering stage to comprehensively evaluate the effects of water deficits on key cotton growth parameters and their physio-biochemical attributes.

Experimental layout

The experiment was conducted from 16th April 2023 to 5th June 2023, and the seeds from the selected cotton genotypes were sown in plastic pots (30 × 70 cm), each containing 11 kg of a standardized soil substrate composed of 9 kg of clay and 2 kg of sand. Before sowing, pots were irrigated with tap water to achieve field capacity. Seeds were pre-soaked in water for 12 h overnight to enhance imbibition, and subsequently sown at 6:30 a.m. the following morning, placing four to five seeds at a depth of 2 cm per pot. Upon successful germination, thinning was performed to retain a single vigorous seedling per pot. The glasshouse conditions were stringently maintained, with diurnal temperatures regulated between 33 °C and 37 °C and nocturnal temperatures between 27 °C and 30 °C, using an automated heating and cooling system. At 22 days after emergence, each pot received basal fertilization equivalent to 100 kg N ha−1 (as urea) and 70 kg P2O5 ha−1 (as DAP). Regular irrigation with tap water continued until the onset of flowering.

Drought stress treatments were imposed at the flowering stage (50 days after sowing) by establishing three distinct soil moisture regimes: 100% field capacity (FC) as the control, 60% FC for moderate drought stress, and 40% FC for severe drought stress. Soil moisture levels were precisely regulated through daily gravimetric assessments using a precision digital balance (WT10001GF, China), with water volumes adjusted accordingly to sustain the designated moisture levels over a 14-day stress period during flowering. After imposing controlled drought stress, comprehensive morpho-physiological and biochemical analyses were conducted to characterize genotype-specific responses under water-deficit conditions.

Soil moisture estimation

Soil field capacity (FC) represents the moisture content retained by soil after full saturation and subsequent gravitational drainage. To determine soil FC, a homogeneously mixed 200 g of oven-dried soil sample was placed in a perforated 1-liter container lined with filter paper. Water was gradually added until saturation was achieved, followed by an hour equilibration period to ensure uniform infiltration. The container was then positioned over a secondary vessel to allow free drainage for 48 h, facilitating the removal of gravitational water. Subsequently, the container was weighed to obtain the wet weight (Ww), and after accounting for the container and filter paper mass, FC was calculated using the following formula.

FC (%) = [(Ww - Wd)/Wd] × 100.

where Ww represents the weight of water-saturated soil (256 g) and Wd denotes the weight of oven-dried soil (200 g). This calculation yielded a 28% water-holding capacity for the experimental soil. Water requirements for different FC Levels were calculated as given below.

100% FC (T1): Required 280 g (or mL) of water per kg of soil, resulting in a total system weight of 1280 g (soil + water).

60% FC (T2): Required (28/100) × 60 = 168 g H2O kg−1 soil, with a total weight of 1168 g.

40% FC (T3): Required (28/100) × 40 = 112 g H2O kg−1 soil, totaling 1112 g.

These standardized values were rigorously applied to maintain precise moisture levels throughout the drought stress treatments, ensuring accurate simulation of 100% FC (control), 60% FC (moderate drought), and 40% FC (severe drought) conditions. To maintain the desired irrigation regimes, soil moisture levels were monitored regularly using a gravimetric method. The pots were weighed daily to determine water loss through evapotranspiration. The water lost was replenished to maintain the required field capacity for each treatment: 100% FC (well-watered), 60% FC (moderate drought stress), and 40% FC (severe drought stress).The methodology guaranteed reproducible water stress regimes for all experimental units.

Morphological parameters

After drought stress treatments imposition, several morphological traits were observed, including shoot length (SL), root length (RL), shoot and root fresh weight (SFW, RFW), shoot and root dry weight (SDW, RDW), flower retention (FR), and number of bolls per plant (NBP). To minimize root loss during uprooting, pots were prepared with a 3:1 clay-to-sand mixture to enhance porosity, and roots were gently recovered by flooding the pots with water, thereby reducing mechanical damage. Fine roots were meticulously collected through careful washing and sieving to ensure accurate biomass quantification. Subsequently, the root and shoot samples of all planted genotypes were oven-dried at 72 °C for four days (EB-4 A, China) to determine dry biomass. Additionally, flower retention (FR) was assessed as an indicator of reproductive stability under drought. Uniform, healthy plants were tagged at the onset of floral structures, and newly opened flowers were marked with colored badges for sequential tracking. FR was monitored every 8–10 days until boll development, and at 25 days post-anthesis, the number of retained flowers was recorded. Flower retention percentages were computed by using the protocol established by7. Despite this, the number of bolls per plant was quantified before harvest to evaluate reproductive success across treatments.

Physiological parameters

The physiological attributes of the evaluated cotton genotypes under normal and drought stress conditions, including stomatal conductance (gs), net photosynthetic rate (Pn), and transpiration rate (E), were measured using an InfraRed Gas Analyzer (IRGA, Ci-340, USA). Assessments were conducted after 14 days of sustained irrigation treatments corresponding to three distinct soil moisture conditions: control (100% field capacity, FC), moderate drought stress (60% FC), and severe drought stress (40% FC). Measurements were performed on clear days between 9:30 AM and 12:00 PM to capture peak photosynthetic activity, consistently sampling the topmost fully expanded, sun-exposed leaf to minimize intra-plant variability and ensure comparability across genotypes.

The relative water content (RWC) and excised leaf water loss (ELWL) were determined to assess the plant water status and dehydration tolerance under different irrigation regimes. For RWC measurement, fully expanded, healthy leaves were collected from each treatment at mid-day to minimize diurnal variation. The fresh weight (FW) of each leaf sample was immediately recorded using an electronic balance (Model EB-4 A, China). The leaves were then floated in distilled water for 24 hours at 25 °C under low light conditions to attain full turgidity. After removing surface moisture with blotting paper, the turgid weight (TW) was recorded. The samples were subsequently oven-dried at 70 °C for 48 h to obtain the dry weight (DW). The RWC was calculated using the formula described by Smart et al.24.

The excised leaf water loss was measured to evaluate the rate of water loss and the ability of cotton plants to retain moisture under drought conditions. Fully expanded, healthy leaves were collected from each accession during the mid-day period to minimize variation due to diurnal effects. Immediately after excision, the fresh weight (FW) of each leaf sample was recorded using a precision electronic balance (Model BA-E1004, China). The leaf samples were then placed on a laboratory bench at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) and relative humidity (60–65%) for 4 h to allow natural wilting and simulate dehydration. After this period, the wilted weight (WW) was recorded. The leaves were subsequently oven-dried at 70 °C for 24 h to obtain the dry weight (DW). ELWL was calculated according to the method described by25 using the following equation:

Collectively, these indicators, including ELWL, RWC, Pn, and E rate, offer an integrated perspective on the physiological resilience of cotton genotypes under water-limited conditions. These traits help in understanding genotype-specific abilities to maintain cellular hydration, regulate water balance, and sustain photosynthetic efficiency, all of which are critical determinants of drought tolerance and adaptive performance in arid environments.

Biochemical parameters

To appraise the antioxidant enzyme activity, leaf samples (0.2 g) were collected from growing cotton genotypes two weeks after the initiation of drought stress treatments. The samples were immediately immersed in cold phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) and homogenized using a mortar and pestle. The resulting mixture was then centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min to separate the cellular debris, yielding a clear supernatant. This supernatant was subsequently used to measure the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), catalase (CAT), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX). The SOD activity was quantified based on its capacity to restrict the nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) photo-reduction in the presence of superoxide ions, and absorbance was recorded at 560 nm following26. Peroxidase (POD) activity was determined via a guaiacol oxidation assay, measuring the increase in absorbance at 470 nm due to guaiacol oxidation catalyzed by the enzyme in the presence of H2O2. Catalase (CAT) activity was evaluated by monitoring the decomposition rate of H2O2 at 240 nm27. Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity was assayed by tracking the decrease in absorbance at 290 nm resulting from ascorbate oxidation in the presence of H2O228.

Malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration, indicative of lipid peroxidation, was delineated using the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) technique, and MDA–TBA complex absorbance was manifested at 532 nm29. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) concentrations were determined by coupling plant extracts with potassium iodide (KI) under acidic conditions, measuring the resulting absorption at 390 nm30. Total soluble proteins (TSP) were estimated using the Bradford method, in which plant extracts were agitated with Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye, and absorption was recorded at 595 nm31.

Total soluble sugars (TSS) were analyzed by following the anthrone reagent protocol, estimating the Absorption of the resulting green complex at 620 nm32. Proline (Pro) concentration was assessed through the acid ninhydrin assay, with absorbance measured at 520 nm33. Photosynthetic pigments, including chlorophyll a (Chl.a), chlorophyll b (Chl.b), and total chlorophyll (T.chl), were extracted in 80% acetone, with concentrations calculated from absorbance readings at 663, 645, and 470 nm, respectively, employing established equations for each pigment fraction34.

Evaluation of multi-trait genotype-ideotype distance index (MGIDI) calculation

The Multi-Trait Genotype-Ideotype Distance Index (MGIDI) was used to rank genotypes based on their alignment with an ideal drought-resistant ideotype. The ideal genotype was defined using expert knowledge and a review of relevant literature to identify optimal trait values associated with drought tolerance. Factor analysis was conducted to group traits based on their physiological relevance to drought resistance. Traits were grouped into factors based on their underlying biological mechanisms, such as water-use efficiency, root architecture, and leaf physiology. Factor rotation (varimax) was applied to achieve a clearer interpretation by maximizing the variance of trait loadings across factors. The factor structure was validated by retaining factors with eigenvalues greater than unity, which indicated that the most meaningful factors were retained. The Euclidean distance between each genotype’s traits and the ideal ideotype was calculated as follows:

where xijk represents the normalized value of trait j for genotype i under k stress level, and xideotype, j denotes the ideotype value for trait j. The MGIDI score for each genotype was calculated for index computation by aggregating the weighted distances across all attributes and stress levels, demonstrating its overall compliance with the ideotype.

Where wj denotes the weight attributed to trait j, indicating its perceived significance in drought tolerance, and j represents the total number of attributes. Genotypes were prioritized according to their MGIDI scores, where lower scores signify features more congruent with the drought-tolerant ideotype, indicating superior performance under drought conditions.

Statistical analysis

To determine the impact of treatments and genotypes, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and descriptive statistics were performed using the R environment (version 4.5.1). Prior to multivariate analyses, the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were assessed. Visual inspection of histograms for each trait across treatments indicated that the data were approximately normally distributed with relatively consistent variances, supporting the use of parametric methods. To mitigate potential Type I error inflation from multiple trait comparisons, a False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction was applied to p-values obtained from the two-way ANOVA across all traits. The FDR adjustment was performed using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure at a 5% significance level, which effectively controls false positives while maintaining statistical power. Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test was used for post hoc pairwise comparisons. Data were analyzed under a completely randomized design (CRD) with irrigation and genotype as fixed factors. Means were compared using LSD at p ≤ 0.05. A post hoc power analysis (R pwr package) confirmed adequate power (> 0.85) to detect medium-to-large effects (f = 0.25–0.40). Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for significant comparisons to assess the strength and precision of observed effects.

Histogram analyses were performed in Python (version 3.12.8) to visualize the frequency distribution of all cotton accessions for each trait under water-stress treatments. The peaks of the kernel density estimation (KDE) curves represented mean values, while overlaid bars depicted the frequency distribution of replicated data, typically centered around the means. To evaluate variability among genotypes and traits under different irrigation regimes, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed using the Factoextra and FactoMineR packages in R. Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to examine relationships among traits, and a heatmap generated with the pheatmap package illustrated clustering patterns among genotypes. Additionally, the multi-trait genotype–ideotype distance index (MGIDI) was computed using the metan package in R35 to identify drought-tolerant genotypes under each irrigation treatment.

Results

Descriptive statistics for morphological traits

In this study, forty genetically diverse cotton genotypes were evaluated under three irrigation regimes: control (100% field capacity), moderate drought stress (60% FC), and severe drought stress (40% FC). The three drought stress treatments significantly influenced plant growth and development. Compared with the control (100% FC), both moderate (60% FC) and severe drought stress (40% FC) caused noticeable reductions in plant height, leaf expansion, and overall vigor. The severity of stress was directly proportional to the decline in growth attributes, with the most pronounced effects observed under severe drought conditions. These findings collectively highlight the adaptive responses of cotton genotypes to drought stress, with varying degrees of resilience depending on the genotype and stress level (Table 3).

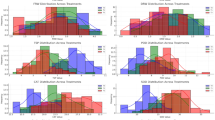

Under control conditions (T1), the mean shoot length (SL) was 46.28 ± 5.69 cm, ranging from 35.20 to 56.50 cm. This decreased to 29.47 ± 6.83 cm under moderate drought stress (T2), ranging from 17.50 to 56.50 cm, and further declined to 18.22 ± 4.76 cm under severe drought stress (T3), ranging from 10.50 to 36.80 cm, clearly indicating the deleterious impact of drought stress. Similarly, shoot fresh weight (SFW) under T1 was 31.54 ± 8.00 g, which dropped to 20.11 ± 5.72 g under T2 and further to 13.01 ± 3.90 g under T3. Root length (RL) decreased from 16.96 ± 4.10 cm under T1 to 12.31 ± 2.98 cm under T2 and further to 8.17 ± 2.43 cm under T3. Likewise, root fresh weight (RFW) decreased from 12.12 ± 2.93 g (ranging from 5.20 to 20.50 g) under T1 to 8.38 ± 2.32 g (range: 4.00 to 16.80 g) under T2, and further declined to 5.18 ± 1.79 g (range: 2.00 to 11.20 g) under T3. Shoot dry weight (SDW) decreased from 17.27 ± 2.24 g under T1 to 12.28 ± 2.75 g under T2 and further to 7.27 ± 2.00 g under T3. Root dry weight (RDW) declined from 3.31 ± 0.50 g under T1 to 2.56 ± 0.48 g under T2 and further to 1.59 ± 0.40 g under T3 (Fig. 1; Table 3). Flower retention (FR) dropped from 8.47 ± 2.63 under T1 to 6.77 ± 2.62 under T2 and further to 5.24 ± 2.61 under T3. The number of bolls per plant (NBP) decreased from 9.30 ± 2.09 under T1 to 7.14 ± 1.96 under T2 and further to 5.07 ± 2.03 under T3 (Fig. 2; Table 3).

Histogram displaying the frequency distribution of various morphological traits across 40 cotton genotypes under three treatments: T1 (green), the control condition (100% field capacity); T2 (orange), moderate drought stress (60% field capacity); and T3 (purple), severe drought stress (40% field capacity). The traits include (A) shoot length (SL); (B) shoot fresh weight (SFW); (C) root length (RL); (D) root fresh weight (RFW); (E) shoot dry weight (SDW); and (F) root dry weight (RDW). Overlaid smooth lines represent kernel density estimations (KDE), offering a clear visualization of the probability distribution of each trait under the three treatments, highlighting the variations and central tendencies across the genotypes.

Histogram visualization depicts the frequency distribution of reproductive traits across 40 cotton genotypes under three treatments: T1 (green), the control condition (100% field capacity); T2 (orange), moderate drought stress (60% field capacity); and T3 (purple), severe drought stress (40% field capacity). The traits include (A) flower retention per plant (FR), and (B) number of bolls per plant (NBP). Overlaid smooth lines represent kernel density estimations (KDE), providing a clear visualization of the probability distribution of each trait under the three treatments, highlighting the variations and central tendencies across the genotypes.

Descriptive statistics for physiological traits

Among the physiological attributes, the photosynthetic rate (Pn) of cotton plants showed a clear decline under increasing drought stress. The net photosynthesis rate decreased from 17.17 ± 3.23 under T1 to 11.92 ± 2.99 under T2 and further to 6.94 ± 2.41 under T3, reflecting reduced photosynthetic efficiency with increasing drought stress. Similarly, transpiration rate (E) dropped from 10.23 ± 1.73 under T1 to 7.04 ± 1.89 under T2 and 4.19 ± 1.73 under T3, indicating reduced stomatal conductance due to water deficit. Stomatal conductance (gs) also decreased from 0.84 ± 0.15 under T1 to 0.58 ± 0.16 under T2 and 0.34 ± 0.13 under T3, suggesting diminished stomatal activity under drought stress. Chlorophyll content, including chlorophyll a (Chl.a), chlorophyll b (Chl.b), and total chlorophyll (T.chl), progressively decreased, from 0.66 ± 0.12, 0.53 ± 0.10, and 1.18 ± 0.23 under T1 to 0.46 ± 0.14, 0.34 ± 0.10, and 0.80 ± 0.24 under T2, and further to 0.31 ± 0.14, 0.20 ± 0.08, and 0.50 ± 0.20 under T3 respectively. This decline reflects a reduction in the plant’s photosynthetic potential as drought stress intensified (Fig. 3; Table 3).

Histogram visualization showing the frequency distribution of physiological traits across 40 cotton genotypes under three treatments: T1 (green) control condition (100% field capacity), T2 (orange) moderate drought stress (60% field capacity), and T3 (purple) severe drought stress (40% field capacity). The traits include (A) photosynthesis rate (Pn), (B) transpiration rate (E), (C) stomatal conductance (gs), (D) chlorophyll a (Chl.a) content, (E) chlorophyll b (Chl.b) content, and (F) total chlorophyll (T.chl) content. Overlaid smooth lines represent kernel density estimations (KDE), providing a clearer view of the probability distribution of each trait under different drought stress levels, highlighting variations and central tendencies across the genotypes.

Descriptive statistics for biochemical traits

Under increasing drought stress, several biochemical markers showed significant changes. TSP decreased from 13.11 ± 2.36 under T1 to 9.75 ± 1.84 under T2, and further to 3.67 ± 0.99 under T3, indicating a reduction in overall protein content with more severe stress. TSS increased from 5.97 ± 1.08 under T1 to 10.81 ± 2.23 under T2 and further to 17.94 ± 3.51 under T3, suggesting an accumulation of sugars as an adaptive response to water deficit. TFA also showed an upward trend, rising from 9.87 ± 1.84 under T1 to 15.36 ± 2.97 under T2 and 21.45 ± 3.91 under T3, reflecting enhanced energy reserves to cope with stress. Proline (Pro) content increased from 227.70 ± 31.36 under T1 to 314.13 ± 32.48 under T2 and 357.96 ± 31.94 under T3, suggesting an accumulation of this stress marker in response to increasing water deficit. Relative water content decreased from 63.72 ± 10.11 under T1 to 53.11 ± 10.31 under T2 and 43.29 ± 10.51 under T3, highlighting a reduction in plant hydration under drought conditions. Excised leaf water loss also increased from 0.53 ± 0.37 under T1 to 0.70 ± 0.42 under T2 and 0.86 ± 0.52 under T3, reflecting higher membrane damage owing to an increase in stress intensity (Fig. 4; Table 3).

Histogram visualization illustrates the frequency distribution of various biochemical and physiological traits across 40 cotton genotypes under three treatments: T1 (green) control condition (100% field capacity), T2 (orange) moderate drought stress (60% field capacity), and T3 (purple) severe drought stress (40% field capacity). The traits analyzed include (A) total soluble protein (TSP), (B) total soluble sugars (TSS), (C) total free amino acids (TFA), (D) proline (Pro) content, (E) relative water content (RWC), and (F) excised leaf water loss (ELWL). Overlaid smooth lines represent kernel density estimations (KDE), providing a clear visualization of the probability distribution of each trait under the different treatments, highlighting variations and central tendencies across the genotypes.

Among the antioxidant enzymes, SOD significantly rose from 193.98 ± 39.68 under T1 to 318.69 ± 59.95 under T2 and 443.72 ± 78.37 under T3, indicating a heightened oxidative stress response. POD activity also increased from 317.07 ± 56.06 under T1 to 491.50 ± 84.40 under T2 and 607.28 ± 107.8 under T3, further supporting this response. Similarly, CAT activity rose from 306.33 ± 54.70 under T1 to 485.53 ± 86.54 under T2 and 608.24 ± 109.27 under T3, reflecting a greater effort to mitigate oxidative damage. APX activity also increased from 178.24 ± 30.82 under T1 to 278.90 ± 51.57 under T2 and 385.08 ± 70.70 under T3, indicating an enhanced antioxidant defense system under drought stress. In addition, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) levels rose from 2.48 ± 0.37 under T1 to 4.11 ± 0.60 under T2 and 4.81 ± 0.65 under T3, reflecting heightened oxidative stress. Similarly, malondialdehyde (MDA), an indicator of lipid peroxidation, increased from 0.70 ± 0.10 under T1 to 1.06 ± 0.19 under T2 and 1.29 ± 0.21 under T3, further indicating cellular damage due to oxidative stress (Fig. 5; Table 3).

Histogram visualization illustrates the frequency distribution of antioxidant enzyme activities and stress markers across 40 cotton genotypes under three treatments: T1 (green) control condition (100% field capacity), T2 (orange) moderate drought stress (60% field capacity), and T3 (purple) severe drought stress (40% field capacity). The traits include (A) Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) activity, (B) Peroxidase (POD) activity, (C) Catalase (CAT) activity, (D) Ascorbate Peroxidase (APX) activity, (E) Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) content, and (F) Malondialdehyde (MDA) content. Overlaid smooth lines represent kernel density estimations (KDE), providing a clear view of the probability distribution of each trait under the different drought conditions, highlighting variations and central tendencies across the genotypes.

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) was meticulously performed separately for each treatment to reduce dimensionality across morpho-physiological, biochemical, and genotype data. Under control conditions, PC1 and PC2 explained 62.9% and 13.5% of the variance (76.4% cumulative and retained eigenvalues greater than unity (Fig. 6a). The biplot (Fig. 7a) showed G8 (N-221) and G9 (N-444) aligned with higher NBP, RWC, FR, and SL, depicting superior lint productivity potential. In contrast, G1 (IR-11), G7 (Cyto-124), G10 (N-812), G11 (N-1942), and G13 (N-9614) loaded with elevated ELWL, suggesting lower drought adaptability.

Under moderate (PC1 = 75.7%, PC2 = 9.4%) and severe drought PC1 = 76.2%, PC2 = 12.1%), scree plots again supported using the first two PCs (Fig. 6b,c). The biplot analysis across both stress levels, G2 (IR-14), G8 (N-221), G9 (N-444), G17 (FH-154), G20 (FH-492), and G25 (FH-540) associated positively with key traits (SFW, RL, SL, NBP, FR, T.chl, RWC, Pro, SOD, E, Pn, TSS) indicating superior performance (Fig. 7b,c). Conversely, G1 (IR-11), G3 (IR-16), G7 (Cyto-124), G10 (N-812), G11 (N-1942), G13 (N-9614), and G35 (MNH-1050) showed higher oxidative damage owing to escalated levels of MDA, H2O2, and ELWL, reflecting poorer performance under drought stress (Fig. 7b,c).

PCA biplot illustrates the relationships among various physiological and biochemical traits across 40 diverse cotton genotypes under (A) control, (B) moderate drought stress, and (C) severe drought stress. The vector length indicates the strength of the relationship between each trait and the principal components. Genotypes are marked with different codes along with treatment labels to indicate their drought tolerance. The biplot highlights the variation in physio-morphic and biochemical responses to stress across 40 diverse cotton genotypes.

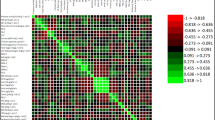

Pearsons correlation analyses

Pearson’s correlation analysis aids in ascertaining the positive and negative correlation among analyzed traits under all applied treatments. Under control conditions, T.chl shows strong positive correlations with pro (r = 0.91***), APX (r = 0.93***), and TSS (r = 0.88***), and strong negative correlations with RL (r = − 0.63***) and ELWL (r = − 0.57***). In addition, FR correlates positively with pro (r = 0.53***), gs (r = 0.51***), and TSS (r = 0.53***), while it was negatively correlated with ELWL (r = − 0.84***) (Fig. 8a).

Under moderate drought, SFW depicts a strong positive interplay with NBP (r = 0.77***), FR (r = 0.66***), and RL (r = 0.84***), and negatively with MDA (r = −0.84***), ELWL (r = −0.76***), and H2O2 (r = −0.81***). ELWL was negatively correlated with Pro (r = −0.76***), APX (r = −0.81***), and NBP (r = −0.86***) but positively linked with MDA and H2O2 (r = 0.77–0.85***). Proline is strongly and positively correlated with APX (r = 0.95***), T.chl (r = 0.94***), TSS (r = 0.97***), and negatively associated with ELWL (r = − 0.76***) and MDA (r = − 0.63***) (Fig. 8b).

Under severe drought, ELWL correlates positively with H2O2 (r = 0.74***) and MDA (r = 0.76***), and negatively with RWC (r = − 0.76***), SOD (r = − 0.77***), and T.chl (r = − 0.90***). Proline shows strong positive correlations with T.chl (r = 0.96***), Pn (r = 0.93***), and CAT (r = 0.81***), and strong negative interaction with ELWL (r = − 0.92***), MDA (r = − 0.63***) (Fig. 8c).

Pearson’s correlation matrix showing the relationships between various physiological, biochemical, and morphological traits across cotton genotypes under three treatments: (A) control, (B) moderate drought stress, and (C) severe drought stress. The color scale represents the strength of the correlation, with blue indicating positive correlations and red indicating negative interactions. Asterisks depict statistical significance levels (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

Heatmap analysis

The heatmap visually represents the relative performance of various cotton genotypes under normal, moderate, and severe drought stress conditions (Fig. 9). The genotypes were clustered based on the mean values of the studied attributes, resulting in distinct groups. Under control conditions, the forty genotypes were classified into three clusters, reflecting their varying performance across the evaluated traits (Fig. 9A).

Heatmap for cotton genotypes grown under moderate (Fig. 9B) and severe (Fig. 9C) drought stress reveals three distinct performance clusters. Cluster 1, represented in blue, includes genotypes such as G25 (FH-540), G8 (N-221), G9 (N-444), G2 (IR-14), G17 (FH-154), and G20 (FH-492) which exhibit strong positive interplay across most traits, including TFA, SOD, APX, T.chl, Pn and RWC whereas their negative interaction was evident with ELWL, H2O2, and MDA. These interactions showcased their tolerant response to moderate and severe water deficits. Cluster 2, marked in red, consists of genotypes like G13 (N-9614), G7 (Cyto-124), G35 (MNH-1050), and G10 (N-812), G1 (IR-11), G3 (IR-16), G11 (N-1942) showing a strong negative relationship with NBP, FR, RWC, RL, and RFW, which clearly indicate their poor performance under drought stress. In addition, cluster 3 (green in color), includes genotypes like G32 (FH-941), G24 (FH-530), and G27 (FH-571), G16 (FH-118), G30 (FH-631), and several other genotypes exhibit moderate alterations in values for traits such as NBP, FR, RL, and RWC, SFW, suggesting intermediate drought resistance to moderate and severe water scarcity (Fig. 9). This clustering analysis highlights the varying levels of drought tolerance among the genotypes and helps identify those best suited for breeding programs aimed at improving drought resilience. In addition, heatmap analysis also aids in discerning the most susceptible genotypes owing to their strong negative interaction with most of the studied traits except ELWL, MDA, and H2O2 under moderate and severe water deficits.

Hierarchical cluster heatmaps displaying the clustering patterns of cotton genotypes under (A) control (T1), (B) moderate drought stress (T2), and (C) severe drought stress (T3). The heatmaps represent scaled values of morpho-physiological and biochemical traits, with green indicating positive responses and blue representing negative interactions. Clusters differentiate the genotypes based on their trait performance under the control, moderate, and severe drought stress, with distinct groups highlighting differential responses to drought stress. These results emphasize the genotypic variation and stress adaptation mechanisms under varying drought conditions.

Multi-trait genotype–ideotype distance index (MGIDI)

The Multi-trait Genotype–Ideotype Distance Index (MGIDI) was utilized to delineate the superior-performing cotton genotypes under divergent water availability scenarios. A detailed MGIDI analysis, encompassing genotype ranking and an assessment of their respective strengths and weaknesses, was carried out independently for control (Fig. 10), moderate (Fig. 11), and severe (Fig. 12) drought stress at the flowering stage. This methodological approach facilitated an intricate evaluation of each genotype’s adaptive performance across the experimental conditions, thereby elucidating their relative advantages and limitations under variable water stress regimes. Under control conditions, the strengths and weaknesses view plot (Fig. 9A) delineates the contributions of FA1 (red), FA2 (green), and FA3 (blue) to the genotypic performance. Notably, genotypes such as G2 (IR-14), G8 (N-221), G9 (N-444), G20 (FH-492), G21 (FH-513), and G25 (FH-540) exhibit superior performance, particularly in physiological and antioxidant traits (Supplementary Table S1). The genotype ranking plot (Fig. 10B) selected the drought-tolerant genotypes based on analyzed attributes, highlighted in red, including G2 (IR-14), G8 (N-221), G9 (N-444), G20 (FH-492), G21 (FH-513), and G25 (FH-540), which exhibit minimal deviation from the ideal genotype. This signifies their exceptional adaptive capacity and reinforces their suitability as elite candidates for breeding programs under optimal control conditions, showcasing their potential for enhanced performance across multiple traits.

(A) The strengths and weaknesses view under control (100% FC) conditions depicts the individual factor contributions to the MGIDI. The proximity of a factor’s contribution to the centroid signifies a closer alignment of its traits with the ideotype (ideal genotype), indicating superior performance. In contrast, greater deviations of the factor vectors from the centroid signify a suboptimal expression of the associated trait profile in the genotype. The dashed line represents the theoretical equilibrium where all factors contribute equally, serving as a reference for evaluating deviations from the ideal genetic configuration. (B) displayed genotypes that were nearly identical to the ideal genotype, based on heritability (h2), selection differential percentage (SD%), and a 15% selection pressure, using the MGIDI index. The cotton genotypes that were selected are highlighted in red, with the central red circle representing the cut-off point determined by the selection pressure.

(A) The strengths and weaknesses view under moderate drought stress (60% FC) depicts the individual factor contributions to the MGIDI. The proximity of a factor’s contribution to the centroid signifies a closer alignment of its traits with the ideotype (ideal genotype), indicating superior performance. In contrast, greater deviations of the factor vectors from the centroid signify a suboptimal expression of the associated trait profile in the genotype. The dashed line represents the theoretical equilibrium where all factors contribute equally, serving as a reference for evaluating deviations from the ideal genetic configuration. (B) displayed genotypes that were nearly identical to the ideal genotype, based on heritability (h2), selection differential percentage (SD%), and a 15% selection pressure, using the MGIDI index. The cotton genotypes that were selected are highlighted in red, with the central red circle representing the cut-off point determined by the selection pressure.

(A) The strengths and weaknesses view under severe drought stress (40% FC) depicts the individual factor contributions to the MGIDI. The proximity of a factor’s contribution to the centroid signifies a closer alignment of its traits with the ideotype (ideal genotype), indicating superior performance. In contrast, greater deviations of the factor vectors from the centroid signify a suboptimal expression of the associated trait profile in the genotype. The dashed line represents the theoretical equilibrium where all factors contribute equally, serving as a reference for evaluating deviations from the ideal genetic configuration. (B) displayed genotypes that were nearly identical to the ideal genotype, based on heritability (h2), selection differential percentage (SD%), and a 15% selection pressure, using the MGIDI index. The cotton genotypes that were selected are highlighted in red, with the central red circle representing the cut-off point determined by the selection pressure.

Under moderate drought stress, the strengths and weaknesses view plot shows the contributions of FA1 (red), FA2 (green), and FA3 (blue) to the genotypic performance (Fig. 11A). Genotypes such as G2 (IR-14), G8 (N-221), G9 (N-444), G17 (FH-154), G20 (FH-492), and G25 (FH-540) exhibit superior physiological and antioxidant traits (FA2 and FA3), demonstrating enhanced stress resilience. The genotype ranking plot identifies these drought-tolerant genotypes (in red), including G2 (IR-14), G8 (N-221), G9 (N-444), G17 (FH-154), G20 (FH-492), and G25 (FH-540), which display minimal deviation from the ideotype (Fig. 11B). This alignment signifies their optimal adaptation and performance under moderate drought conditions, marking them as prime candidates for drought tolerance breeding programs.

In addition, under severe drought stress, the strengths and weaknesses view plot depicts the contributions of FA1 (red) and FA2 (cyan) to the MGIDI of each genotype (Fig. 12A). The plot highlights elevated contributions with peaks and reduced performance with dips, with the dashed circle denoting the ideal contribution levels (Supplementary Table S1). This analysis aids in evaluating the strengths and vulnerabilities of genotypes under conditions of extreme water scarcity. The Genotype Ranking plot ranks genotypes according to their MGIDI values, with drought-tolerant genotypes (in red) such as G2 (IR-14), G8 (N-221), G9 (N-444), G17 (FH-154), G20 (FH-492), and G25 (FH-540), demonstrating closer alignment with the ideotype, signifying their superior performance and resilience under severe drought conditions (Fig. 12B).

Discussion

Drought stress remains one of the most critical abiotic constraints limiting cotton productivity worldwide, especially in arid and semi-arid regions36. Enhancing drought tolerance in cotton is therefore essential for sustaining yield and fiber quality under reduced water availability. The present study evaluated forty genetically diverse cotton genotypes under three moisture regimes (100%, 60%, and 40% field capacity) to characterize their drought responses through a comprehensive assessment of morpho-physiological and biochemical attributes.

Significant genotypic variability was observed in response to moisture stress across genetically diverse cotton accessions (Table 1). Genotypes G2 (IR-14), G8 (N-221), G9 (N-444), G17 (FH-154), G20 (FH-492), and G25 (FH-540) consistently exhibited greater tolerance, characterized by higher shoot and root biomass, sustained higher number of bolls per plant, and flower retention rate (Figs. 1 and 2). The drought-tolerant cotton genotypes demonstrated synergistic congruent variability patterns with vital growth, physiological, and antioxidant enzymes, showed drought-tolerant responses. Moreover, to discern the most drought-susceptible cotton accessions, various multivariate analyses, including PCA and heatmap analysis, were performed separately for each imposed stress. Our PCA analysis findings clearly showcased the escalated variability interplay with MDA, H2O2 and ELWL in several cotton genotypes including G1 (IR-11), G3 (IR-16), G7 (Cyto-124), G10 (N-812), and G11 (N-1942), G13 (N-9614), and G35 (MNH-1050) which depicts their susceptible nature under moderate and severe water scarcity (Figs. 5 and 6).

The drought-tolerant genotypes identified using Heatmap analysis corroborates that G2 (IR-14), G8 (N-221), G9 (N-444), G17 (FH-154), G20 (FH-492), and G25 (FH-540) were distinctly clustered in a separate group (Cluster 2, blue in color), demonstrating a pronounced positive association with a wide array of morphological, physiological, and biochemical attributes. These genotypes exhibited a marked negative correlation with excised leaf water loss (ELWL), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and malondialdehyde (MDA) concentrations, which collectively highlight their adaptive drought-resilient phenotype under both moderate and severe water deficit conditions (Fig. 9). In contrast, drought-susceptible cotton genotypes G1 (IR-11), G3 (IR-16), G7 (Cyto-124), G10 (N-812), and G11 (N-1942), G13 (N-9614), and G35 (MNH-1050) were aggregated into a separate cluster (red in color), displaying predominantly negative interactions with key growth-related parameters, as well as physiological and biochemical processes. Intriguingly, these genotypes showed a significant positive correlation with ELWL, MDA, and H2O2, reflecting their susceptibility to oxidative stress and cellular damage under water deficits. These genotype-dependent variations are consistent with prior reports in cotton and other crops exposed to water-limited environments, reinforcing the complex genetic and physiological networks that regulate drought susceptibility and tolerance mechanisms37,38.

Drought-tolerant genotypes maintained superior flower retention and a higher number of bolls per plant, compared with drought-susceptible accessions, likely due to their ability to regulate carbohydrate metabolism and hormonal balance by reducing ethylene biosynthesis10,39. The drought-induced decline in boll number, fresh and dry biomass observed in sensitive genotypes is consistent with reduced carbohydrate availability and hormonal imbalance that divert assimilates toward survival rather than reproduction40,41. These findings highlight the practical significance of preserving assimilate allocation to reproductive organs for sustaining lint yield under water-limited conditions.

Physiological indicators such as photosynthetic rate (Pn), stomatal conductance (gs), transpiration (E), and relative water content (RWC) declined sharply under water deficit, but the magnitude of reduction varied across genotypes (Fig. 3). Drought-tolerant accessions maintained relatively higher RWC, Pn, and gs, indicating effective osmotic adjustment and stomatal regulation42,43. These results emphasize that physiological plasticity and efficient water use, rather than absolute values alone, determine real-world drought performance44.

Osmotic adjustment played a pivotal role in sustaining cellular turgor under drought stress. Enhanced accumulation of osmolytes, including proline, total soluble sugars, and total free amino acids and proteins, was observed in drought-tolerant genotypes compared to drought-susceptible cotton genotypes45. However, as recent studies suggest, elevated proline levels can serve dual functions, acting both as a protective osmoprotectant and as a stress marker, contingent on the specific physiological context46,47. In the current study, proline accumulation, in conjunction with augmented soluble sugar, soluble proteins, and amino acid concentrations, facilitated osmotic regulation, enzymatic stability, and ionic homeostasis. Previous studies on cereals and cotton crops have consistently demonstrated that the synergistic accumulation of compatible solutes is crucial for sustaining cellular metabolic processes under water deficit scenarios48,49. This coordinated osmolyte accumulation actively stabilizes cellular macromolecules, safeguards enzymatic function, and sustains ion homeostasis, ensuring cellular integrity and metabolic continuity. The other importance of molecular chaperones in stress tolerance is identified in wheat studies, wherein overexpression of small heat shock protein TaHSP17.4 and its co-chaperone TaHOP enhanced tolerance to drought and salinity stress and heat stress by modulating proline and malondialdehyde levels and upregulation of stress-responsive pathways50. These mechanisms are crucial for enhancing plant resilience and optimizing physiological performance under severe water stress, highlighting the vital role of osmotic adjustment in drought stress tolerance.

Antioxidative defense systems also varied markedly among genotypes under water deficit conditions. Drought-tolerant cotton accessions demonstrated upregulation of enzymatic antioxidants such as SOD, POD, CAT, and APX, along with increased non-enzymatic antioxidants (flavonoids, phenolics, and soluble proteins)51. These components act synergistically to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) and maintain cellular membrane integrity52. Importantly, the magnitude and consistency of antioxidant responses rather than their mere statistical significance distinguished tolerant genotypes from susceptible ones53,54. The tolerant genotypes G2 (IR-14), G8 (N-221), G9 (N-444), G17 (FH-154), G20 (FH-492), and G25 (FH-540) maintained lower levels of H2O2 and MDA, reflecting reduced lipid peroxidation, whereas susceptible genotypes showed escalated levels of oxidative damage owing to inadequate ROS detoxification capacity55,56. These findings highlight the critical role of robust antioxidative defense systems in mitigating oxidative stress and maintaining cellular homeostasis under water stress. This adaptational approach of plants under stress is regulated mainly through the activation of a family of stress-responsive transcription factors, such as MYB family members. One such example is the MYB2 protein identified in Panax ginseng that positively regulates genes involved in secondary metabolite synthesis under jasmonate signaling57. Although catalase (CAT) activity generally increases to detoxify excess H2O2 by converting it into water and oxygen, under severe drought stress, the rate of ROS generation may exceed the scavenging capacity of antioxidant enzymes, leading to an accumulation of H2O2 despite elevated CAT activity58,59. This phenomenon has been reported in several crop species, where excessive oxidative bursts under prolonged or extreme stress conditions surpass the enzymatic detoxification threshold60,61. Such an imbalance between ROS production and elimination reflects a physiological limitation of antioxidant systems rather than a failure of enzyme activation. These findings highlight the critical role of a balanced and efficient antioxidative defense network in mitigating oxidative stress and maintaining cellular homeostasis under water deficit conditions.

Multivariate analyses, including PCA, heatmap clustering, and Pearson’s correlation analysis, provided deeper insights into drought adaptation patterns. Under moderate and severe stress, PCA positioned the tolerant genotypes along vectors associated with growth and physio-biochemical traits (Fig. 7), whereas susceptible genotypes aligned with oxidative-damage markers such as ELWL, H2O2, and MDA. Heatmap clustering likewise grouped the tolerant set (Cluster 2, blue) with higher RWC, Pn, and secondary metabolite accumulation, while the susceptible set (Cluster 1, red) was characterized by elevated oxidative markers and reduced physiological vigor (Fig. 9); a third cluster (green) displayed intermediate behavior under both stress levels. These patterns collectively validate the distinct morphological, physiological, and biochemical resilience of the tolerant genotypes, emphasizing their breeding potential62. Minor discrepancies in genotype rankings across PCA, correlation, and MGIDI analyses likely reflect their methodological differences. PCA captures total variance, correlation emphasizes inter-trait associations, and MGIDI quantifies the distance from an ideal ideotype, underscoring the need for an integrated consensus ranking system that combines multiple analytical approaches for a more comprehensive assessment of drought tolerance. The inclusion of effect size and confidence interval analyses further strengthens these findings. Large effects for proline accumulation and antioxidant enzymes (d > 0.9) indicate strong biochemical adjustments supporting osmotic balance and oxidative stress defense under severe drought. Meanwhile, moderate-to-large effects for shoot length, relative water content, and photosynthetic rate (d ≈ 0.6–0.8) reveal partial physiological stability under stress. The narrow 95% confidence intervals affirms the consistency and reliability of these results, depicting that the observed differences are both statistically and biologically significant. Collectively, these findings validate G2 (IR-14), G8 (N-221), G9 (N-444), G17 (FH-154), G20 (FH-492), and G25 (FH-540) as genuinely drought-resilient genotypes, which show substantial potential for developing climate-resilient cotton varieties. Although the drought period was limited to two weeks, this duration effectively captured physiological and biochemical responses at the critical reproductive stage. However, a longer exposure to stress could provide further insights into late-stage acclimation mechanisms, which were beyond the scope of this study but could be explored in future research. These statistical measures, alongside the observed practical significance, offer readers a clearer understanding of the real-world relevance of the differences between genotypes, further strengthening the importance of these findings for cotton breeding under drought conditions.

The application of the multi-trait genotype–ideotype distance index (MGIDI) further enhanced selection accuracy by integrating diverse morphological, physiological, and biochemical traits into a single selection metric63. MGIDI effectively identified the same tolerant set, including G2 (IR-14), G8 (N-221), G9 (N-444), G17 (FH-154), G20 (FH-492), and G25 (FH-540), as resilient, stable performers with favorable selection differentials and heritabilities (Figs. 10, 11 and 12). Recent studies support the effective utility of MGIDI for the simultaneous improvement of complex traits under normal and stressful environments, underscoring its application in breeding for drought tolerance64. While this present study targeted established physiological and biochemical markers, future research could be conducted to investigate the role of transcriptional regulators, which, in other crops like ramie, are known to be commanded by WUSCHEL-related homeobox gene families, with the objective of deciphering the genetic basis for the superior root phenotype observed in our drought-tolerant cotton genotypes65. This integrative approach provides crucial insights into the physiological and biochemical mechanisms showcasing drought adaptation in cotton, offering a valuable framework for practical application in breeding endeavors. Identifying drought-tolerant genotypes with consistent performance across traits and stress levels is a significant step toward developing drought-tolerant cotton cultivars that can maintain higher lint productivity under water-limited conditions.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive framework for understanding drought tolerance mechanisms in cotton by integrating morpho-physiological and biochemical indicators with advanced multivariate analyses. Rather than merely identifying tolerant genotypes, the findings highlight the underlying physiological resilience strategies, such as enhanced water retention, efficient antioxidant defense, and osmolyte accumulation, that enable cotton plants to sustain productivity under limited water availability. The incorporation of the multi-trait genotype–ideotype distance index (MGIDI) alongside biplot analysis proved instrumental in distinguishing high-performing genotypes with consistent adaptability across varying drought intensities. This integrated analytical approach offers a reliable and replicable model for screening and selecting drought-resilient germplasm, thereby strengthening breeding precision and selection efficiency. Importantly, the drought-tolerant genotypes identified in this study, G2 (IR-14), G8 (N-221), G9 (N-444), G17 (FH-154), G20 (FH-492), and G25 (FH-540), represent valuable genetic resources for developing next-generation cotton cultivars with enhanced water-use efficiency and stress tolerance. Their deployment in breeding programs can accelerate the development of climate-smart cotton varieties capable of sustaining fiber yield and quality under erratic rainfall and prolonged dry spells. Beyond regional implications, these findings hold global significance. They provide actionable insights for strengthening cotton production systems in both developing and industrialized countries facing increasing hostile climatic fluctuations. By contributing to yield stability, resource-use efficiency, and resilience in global cotton value chains, this research supports broader goals of sustainable agriculture, climate adaptation, and global food and fiber security.

Data availability

Data used during the preparation of this manuscript is available within the article.

References

Batool, A. et al. Root-to-shoot signaling positively mediates source-sink relation in late growth stages in diploid and tetraploid wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 24, 492 (2024).

Bolan, S. et al. Impacts of climate change on the fate of contaminants through extreme weather events. Sci. Total Environ. 909, 168388 (2024).

Dietz, K. J., Zörb, C. & Geilfus, C. M. Drought and crop yield. Plant Biol. 23, 881–893 (2021).

Abu-Zeid, M. A., Abu-Zeid, K. M. & Halim, M. K. Impact of Climate Change on Water Resources. in Climate Changes Impacts on Aquatic Environment: Assessment, Adaptation, Mitigation, and Road Map for Sustainable Development 121–157 (Springer, 2025).

Kanaoujiya, R. et al. Agricultural water scarcity: an emerging threat to global water security. in Sustainable Agriculture under Drought Stress 15–22 (Elsevier, 2025).

Ali, M. A. et al. Cotton production in Pakistan. Cotton Production, 249–276 (2019).

Shani, M. Y. et al. Unveiling drought tolerant cotton genotypes: insights from Morpho-Physiological and biochemical markers at flowering. Plants 14, 616 (2025).

Ahmed, M., Ahmad, S., Abbas, G., Hussain, S. & Hoogenboom, G. Cotton-Wheat System. in Cropping Systems Modeling Under Changing Climate 143–171 (Springer, 2024).

Pankaj Kumari, G., Monika, Arya, S. S. & Devi, S. Potential of halophytes in greening the barren land and making use of waste lands. in Cutting Edge Technologies for Developing Future Crop Plants 437–455 (Springer, 2025).

Meshram, J. H., Singh, S. B., Raghavendra, K. P. & Waghmare, V. N. Drought stress tolerance in cotton: progress and perspectives. Clim. Change Crop Stress, 135–169 (2022).

Hu, W. et al. Combined effect of elevated temperature and drought stress on carbohydrate metabolism of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) subtending leaves. Physiol. Plant. 175, e13866 (2023).

Riedesel, L. et al. Timing and intensity of heat and drought stress determine wheat yield losses in Germany. PLoS One. 18, e0288202 (2023).

Naeem-Ullah, U. et al. Insect pests of cotton crop and management under climate change scenarios. Environment, climate, plant and vegetation growth, 367–396 (2020).

Wahab, A. et al. Plants’ physio-biochemical and phyto-hormonal responses to alleviate the adverse effects of drought stress: A comprehensive review. Plants 11, 1620 (2022).

Zahedi, S. M. et al. Plant adaptation to drought stress: the role of anatomical and morphological characteristics in maintaining the water status. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 25, 409–427 (2025).

Hasanuzzaman, M., Nahar, K., Gill, S. S. & Fujita, M. Drought stress responses in plants, oxidative stress, and antioxidant defense. Clim. Change plant. Abiotic Stress Tolerance, 209–250 (2013).

Qamer, Z., Chaudhary, M. T., Du, X., Hinze, L. & Azhar, M. T. Review of oxidative stress and antioxidative defense mechanisms in Gossypium hirsutum L. in response to extreme abiotic conditions. J. Cotton Res. 4, 9 (2021).

Zhao, R. Z., Jiang, S., Zhang, L. & Yu, Z. B. Mitochondrial electron transport chain, ROS generation and uncoupling. Int. J. Mol. Med. 44, 3–15 (2019).

Gómez, R., Vicino, P., Carrillo, N. & Lodeyro, A. F. Manipulation of oxidative stress responses as a strategy to generate stress-tolerant crops. From damage to signaling to tolerance. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 39, 693–708 (2019).

Saud, S. & Wang, L. Mechanism of cotton resistance to abiotic stress, and recent research advances in the osmoregulation related genes. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 972635 (2022).

Abro, A. A. et al. Integrating physiological and molecular insights in cotton under cold stress conditions. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 72, 2561–2591 (2025).

Kumar, M., Kumar Patel, M., Kumar, N., Bajpai, A. B. & Siddique, K. H. M. Metabolomics and molecular approaches reveal drought stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 9108 (2021).

Qiao, M., Hong, C., Jiao, Y., Hou, S. & Gao, H. Impacts of drought on photosynthesis in major food crops and the related mechanisms of plant responses to drought. Plants 13, 1808 (2024).

Smart, R. E. & Bingham, G. E. Rapid estimates of relative water content. Plant Physiol. 53, 258–260 (1974).

Clarke, J. M., DePauw, R. M. & Townley-Smith, T. F. Evaluation of methods for quantification of drought tolerance in wheat. Crop Sci. 32, 723–728 (1992).

Giannopolitis, C. N. & Ries, S. K. Superoxide dismutases: I. Occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 59, 309–314 (1977).

Chance, B. & Maehly, A. C. [136] Assay of catalases and peroxidases. (1955).

Erel, O. A novel automated method to measure total antioxidant response against potent free radical reactions. Clin. Biochem. 37, 112–119 (2004).

Cakmak, I. & Horst, W. J. Effect of aluminium on lipid peroxidation, superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase activities in root tips of soybean (Glycine max). Physiol. Plant. 83, 463–468 (1991).

Velikova, V., Yordanov, I. & Edreva, A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants: protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 151, 59–66 (2000).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

Riazi, A., Matsuda, K. & Arslan, A. Water-stress induced changes in concentrations of proline and other solutes in growing regions of young barley leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 36, 1716–1725 (1985).

Bates, L. S., Waldren, R. P. A. & Teare, I. D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant. soil. 39, 205–207 (1973).

Arnon, D. I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 24, 1 (1949).

Debnath, P. et al. A novel multi trait genotype ideotype distance index (MGIDI) for genotype selection in plant breeding: Application, prospects, and limitations. Crop Des. 85, 100074 (2024).

Chaffai, R., Ganesan, M. & Cherif, A. Global drought threat: impact on food security. In Plant adaptation to abiotic stress: from signaling pathways and microbiomes to molecular mechanisms 61–82 (Springer, 2024).

Singh, A. et al. Drought stress in maize: stress perception to molecular response and strategies for its improvement. Funct. Integr. Genom. 23, 296 (2023).

Mahmood, T. et al. Insights into drought stress signaling in plants and the molecular genetic basis of cotton drought tolerance. Cells 9, 105 (2019).

Majeed, S. et al. Heat stress in cotton: a review on predicted and unpredicted growth-yield anomalies and mitigating breeding strategies. Agronomy 11, 1825 (2021).

Lee, J. M. The effect of plant growth management on cotton susceptibility to drought during the flowering and boll filling stages. (2023).

Bhattacharya, A. Effect of soil water deficit on growth and development of plants: a review. Soil Water Deficit Physiological Issues Plants, 393–488 (2021).

Franco-Navarro, J. D. et al. Advancements in Water‐Saving strategies and crop adaptation to drought: A comprehensive review. Physiol. Plant. 177, e70332 (2025).

Ilyas, M. et al. Drought tolerance strategies in plants: a mechanistic approach. J. Plant Growth Regul. 40, 926–944 (2021).

Kan, Y. et al. TT2 controls rice thermotolerance through SCT1-dependent alteration of wax biosynthesis. Nat. Plants. 8, 53–67 (2022).

Wang, D., Hou, L., Zhang, L. & Liu, P. The mechanisms of silicon on maintaining water balance under water deficit stress. Physiol. Plant. 173, 1253–1262 (2021).

Szabados, L. & Savouré, A. Proline: a multifunctional amino acid. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 89–97 (2010).

Hayat, S. et al. Role of proline under changing environments: a review. Plant Signal. Behav. 7, 1456–1466 (2012).

Havrlentová, M., Kraic, J., Gregusová, V. & Kovácsová, B. Drought stress in cereals–a review. Agriculture 67, 47–60 (2021).

Das, A. K. et al. Salicylic acid priming improves cotton seedling heat tolerance through photosynthetic pigment preservation, enhanced antioxidant activity, and osmoprotectant levels. Plants 13, 1639 (2024).

Wang, Y. X. et al. Heat shock protein TaHSP17. 4, a TaHOP interactor in wheat, improves plant stress tolerance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 246, e125694 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Effects of acute salinity stress on osmoregulation, antioxidant capacity and physiological metabolism of female Chinese mitten crabs (Eriocheir sinensis). Aquaculture 552, 737989 (2022).

Mazhar, S. A. et al. Integrative evaluation of silicon application methods for drought tolerance in wheat using Morpho-Physiological and biochemical markers. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 72, 1–19 (2025).

Alamri, A. Role of Rieske FeS and SBPase in stomatal behaviour. (2022).

Shakya, R. Markers of oxidative stress in plants. in Ecophysiology of tropical plants 298–310 (CRC Press, 2023).

Deng, F. et al. Critical review on the mechanisms of Fe2 + regeneration in the electro-Fenton process: fundamentals and boosting strategies. Chem. Rev. 123, 4635–4662 (2023).

Gul, N. et al. Identification of salt-resilient cotton genotypes using integrated morpho-physiological and biochemical markers at the seedling stage. Sci. Rep. 15, 5276 (2025).

Liu, T. et al. PgMYB2, a MeJA-responsive transcription factor, positively regulates the Dammarenediol synthase gene expression in Panax ginseng. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, e2219 (2019).

Ahmad, Z. et al. Foliage applied silicon ameliorates drought stress through physio-morphological traits, osmoprotectants and antioxidant metabolism of camelina (Camelina sativa L.) genotypes. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Hortorum Cultus. 20, 43–57 (2021).

Jia, J. et al. Drought-mediated oxidative stress and its scavenging differ between citrus hybrids with medium and late fruit maturation. Plant. Stress. 14, 100670 (2024).

Nazar, Z. et al. Glycinebetaine-induced alteration in gaseous exchange capacity and osmoprotective phenomena in safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) under water deficit conditions. Sustainability 12, 10649 (2020).

Hasanuzzaman, M. et al. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under abiotic stress: revisiting the crucial role of a universal defense regulator. Antioxidants 9, 681 (2020).

Farooq, M., Wahid, A., Zahra, N., Hafeez, M. B. & Siddique, K. H. M. Recent advances in plant drought tolerance. J. Plant. Growth Regul. 96, 1–33 (2024).

Mohi-Ud-Din, M. et al. Multi-trait index-based selection of drought tolerant wheat: physiological and biochemical profiling. Plants 14, 35 (2024).

Olivoto, T. & Nardino, M. M. G. I. D. I. Toward an effective multivariate selection in biological experiments. Bioinformatics 37, 1383–1389 (2021).

Abubakar, A. S. et al. Comprehensive analysis of WUSCEL-related homeobox gene family in Ramie (Boehmeria nivea) indicates its potential role in adventitious root development. Biology 12, e1475 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to NIAB-C and PIEAS for providing us with a suitable environment for research activities and supporting us at several crucial stages during the research. Additionally, we thank skilled colleagues who aided in research completion and their unwavering support, encouragement, and confidence-boosting throughout this research journey. The author(s) are grateful for financial support to conduct research activities from different funding institutions including Pakistan Science Foundation, PSF/CRP/18th Protocol (07), National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171994, 32072023, 32272090), Public Sector Development Program under the Ministry of Planning, Development & Special Initiatives (PSDP Project No. 829) and International Foundation for Science, Sweden, and COMSTECH, Islamabad (IFS-C-6500-1) for provision of funds.

Funding

This work has received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MYS and MKRK, conceived and designed the project; MYS, AD and MR analysis, wrote and revised the MS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study adhered to all relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation in Pakistan. Plant materials (cotton seeds) were collected from Nuclear Institute for Agriculture and Biology (NIAB), Faisalabad (38000), Pakistan. No special permissions were required for sample collection. All plant materials used in the study were in compliance with Pakistani regulations and legislation.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Clinical trial

Not applicable.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shani, M.Y., Ditta, A., Khan, M.K.R. et al. Deciphering drought tolerance in cotton genotypes through integrated morpho-physiological and biochemical markers at flowering stage. Sci Rep 15, 44123 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28237-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28237-6