Abstract

In high-pressure university settings characterized by goal conflict and time pressure, health behaviors are often deprioritized. Grounded in the Theory of Planned Behavior and Goal Conflict Theory, this study employed a 2 (goal conflict: high vs. low) × 2 (time pressure: high vs. low) × 4 (time: Week 1–4) mixed experimental design to examine the dynamic evolution of health behavior motivation under dual stress conditions. A total of 88 college students were tracked over four weeks, with repeated measures of their intention and attitude toward executing health behaviors. Results revealed a significant linear decline in implementation attitudes over time, while behavioral intention remained relatively stable. Both high goal conflict and high time pressure independently suppressed motivation, and group differences widened over time. Notably, a significant three-way interaction emerged, with the high-conflict/high-pressure group exhibiting the steepest motivational decline. These findings illuminate the dissipative dynamics of health behavior motivation under cognitive and temporal constraints, extend temporal models of behavioral motivation, and offer theoretical foundations for time management interventions and health promotion strategies in academic environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Among contemporary university students, health behaviors such as regular exercise, balanced nutrition, and adequate sleep are widely acknowledged as vital for both physical well-being and academic performance1. Yet, despite this recognition, many students struggle to maintain these behaviors in practice2. This persistent intention–behavior gap has sparked increasing scholarly interest in understanding the underlying mechanisms shaping students’ Intentions and attitudes toward engaging in health-promoting behaviors. In particular, goal conflict and time pressure are pervasive in student life and systematically bias self-regulation, which can push health behaviors down the priority list.

A growing body of research suggests that when individuals are confronted with multiple competing goals, health behaviors often fall to the bottom of their priority hierarchy3. According to Goal Conflict Theory4, the simultaneous pursuit of incompatible goals strains cognitive and temporal resources, ultimately compromising behavioral execution. For instance, when academic demands conflict with opportunities for physical activity, students are more likely to prioritize academic tasks at the expense of health-related behaviors. In addition, time pressure—a pervasive form of everyday stress—has been identified as another critical determinant of health behavior performance5. Under conditions of high time pressure, individuals tend to adopt time-saving strategies, often reducing or neglecting engagement in health-promoting activities6. In this study, goal conflict is understood as the concurrent activation of incompatible aims that split attention and self-regulatory resources, and time pressure is understood as perceived temporal scarcity that increases the opportunity cost of exercising. These conditions jointly intensify present-oriented choice, so immediately evaluated academic tasks tend to crowd out health behaviors with delayed benefits.

Grounded in the Theory of Planned Behavior together with goal-conflict and scarcity or opportunity-cost perspectives, a clear mechanism explains why an interaction among goal conflict, time pressure, and time should arise. Goal conflict divides attention and self-regulatory resources and thereby lowers the capacity available for health behavior. Time pressure increases the perceived opportunity cost of allocating time to health behavior and promotes present-focused selection of immediately evaluated tasks. Because both mechanisms point in the same direction for behaviors with delayed benefits, their joint presence is expected to suppress Intentions and attitude more than either factor alone. In this framework, time indexes cumulative exposure to these conditions rather than simple repetition of measurement. As exposure lengthens, resource strain and cost salience persist, so the adverse effect of goal conflict becomes stronger when time pressure is high and this difference grows over weeks, whereas low conflict combined with low time pressure should remain relatively stable. This theory-based account motivates the examination of the joint effects and their temporal evolution in the current design.

Accordingly, the purpose of this study is to clarify how university students’ Intentions and attitudes toward executing health behaviors evolve across four weeks when they repeatedly face goal conflict and perceived temporal scarcity. It asks whether goal conflict and time pressure each depress these motivational states, whether their conjoint presence suppresses motivation more than either factor alone, and whether such effects accumulate over time to produce increasingly divergent trajectories across the different contextual combinations.

Literature review

Intention and attitude toward health behavior: theoretical foundations and practical challenges

Health behaviors—such as regular exercise, balanced diet, and adequate sleep—have been consistently shown to play a vital role in preventing chronic diseases and enhancing psychological well-being. Despite increasing awareness and improved knowledge about these benefits, a robust intention–behavior gap persists among university students7. According to the Theory of Planned Behavior, intention and attitude are proximal antecedents of action shaped by belief structures, perceived norms, and perceived behavioral control8.

Within the TPB, both intentions and attitudes are belief-based states that can update with experience when individuals repeatedly sample outcomes and contextual cues across weeks9,10,11. Under recurring goal conflict and perceived time scarcity, weekly episodes foreground the immediate opportunity cost of exercise relative to delayed benefits, shifting evaluative beliefs toward less favorable attitudes12,13. Decision perspectives specify that time pressure narrows deliberation windows and biases choice toward immediately evaluated academic tasks through heightened opportunity costs14. Resource-conservation accounts argue that perceived threats to limited resources such as time, attention, and energy elicit protective allocation to focal obligations, which sustains lower motivation for exercise across repeated episodes15.

Intentions can be buffered by prior plans, subjective norms, and identity commitments, so their change is typically slower and smaller than change in attitudes over comparable periods16. Taken together, these perspectives are complementary rather than redundant: the TPB defines attitude and intention as proximal motivational drivers; decision perspectives explain how scarcity raises opportunity costs and tilts evaluations toward immediately assessed tasks; resource-conservation accounts explain why such shifts persist across weeks through protective allocation. Accordingly, across Weeks 1–4, attitudes toward exercise are expected to decline approximately linearly, whereas behavioral intentions are expected to show no systematic weekly trend (formalized as Hypothesis 1 in Sect. "Research hypotheses").

Goal conflict in university life: the psychological roots of resource competition

Goal conflict refers to the cognitive and behavioral interference that arises when individuals pursue multiple objectives simultaneously—a phenomenon that becomes particularly salient under conditions of limited resources17. Consistent with this definition, the construct analyzed here is time-based goal conflict: time allocated to one goal restricts enactment of another within the weekly schedule18. Goal conflict and multitasking are related insofar as both capture interference under limited cognitive and temporal resources and can coincide when competing goals are scheduled in the same time window19. They differ, however, in unit of analysis, time scale, and primary mechanisms: multitasking and task-switching paradigms examine simultaneous performance or rapid alternation over seconds or minutes and quantify switching costs at the level of task execution, whereas goal conflict is defined at the level of cross-goal scheduling over hours or days and centers on opportunity costs, scheduling constraints, and perceived behavioral control20. In the present design, goal conflict is operationalized as overlap versus separation of scheduled time windows for academic work and exercise; concurrent dual-tasking or rapid alternation is not required21. The theoretical development and hypotheses are grounded in the goal-conflict literature22. In university settings with intensive academic demands and layered personal responsibilities, sustaining health behaviors is especially challenging when goals compete for limited time and attention23. According to Goal Conflict Theory4, when individuals are faced with competing goals—such as maintaining health behaviors versus meeting academic deadlines—their finite cognitive and temporal resources must be allocated between these demands, often resulting in behavioral inhibition and weakened motivation. Consistent with this view, research on personal strivings shows that intergoal interference reduces persistence and well-being, indicating that competition among goals can suppress investment in lower-priority pursuits24.

Within the Theory of Planned Behavior, goal conflict primarily undermines perceived behavioral control: juggling concurrent goals elevates the perceived difficulty and opportunity cost of exercising, which, per TPB, reduces intention and can dampen evaluative beliefs (attitudes) toward exercise25. Within TPB, time and attention demanded by a competing academic goal reduce perceived control over exercise and increase its opportunity cost, which predicts lower intentions and less favorable attitudes26. Conservation of Resources theory likewise predicts protective allocation when resources are threatened, favoring externally evaluated, deadline-bound academic tasks over exercise and thereby sustaining underinvestment in health behavior27,28. Evidence on goal interference shows reduced persistence under competition, and meta-analytic work in health behavior links changes in attitudes and control beliefs to downstream intentions and action, implying that chronic conflict can erode both intention and attitude29,30.Motivated cognition and priority bias also contribute: when progress cues and external contingencies are salient, individuals prefer goals with immediate, evaluative outcomes, which implicitly devalues exercise even in the absence of explicit time pressure31. Repeated selection of academics over exercise can therefore produce attitude drift, even without explicit time pressure. TPB provides the proximal pathway via perceived control and evaluation; personal-goal research defines conflict as intergoal interference; COR explains persistent protective allocation under threat; and priority bias explains selection of immediately evaluated goals. Accordingly, holding time pressure constant, the high-conflict condition is expected to yield lower intentions and less favorable attitudes toward exercise than the low-conflict condition (formalized as Hypothesis 2 in Sect. "Research hypotheses").

Goal conflict was operationalized by the temporal relation between the two goals: when academic work and exercise were scheduled within the same time window, the condition was defined as high conflict; when they were allocated to nonoverlapping time windows, the condition was defined as low conflict. This operationalization accords with the classic definition of time-based role or goal conflict, in which time invested in one goal constrains the enactment of another and reflects cross-goal temporal competition and opportunity costs32. At the measurement level, the Multidimensional Work–Family Conflict Scale conceptualizes time-based conflict as mutual interference arising from time demands, which supports treating schedule overlap and separation as contextual instantiations of this dimension33. Research on personal goals conceptualizes conflict as intergoal interference, not as a requirement to perform two tasks simultaneously; thus it is construct-consistent with an operationalization based on schedule overlap34. In the health-behavior literature, both goal conflict and the temporal arrangement of goals are linked to the intention–behavior relation and predict clinicians’ adherence to guidelines, supporting the contextual validity of representing goal conflict as time-structured competition in health settings35. Across conditions, both goals remained present; only the overlap of their time windows was manipulated, with no prespecified task order and no requirement for concurrent dual-tasking or rapid task switching36.

The behavioral impact of time pressure: cognitive shifts toward immediate rewards

Time pressure is one of the most pervasive environmental stressors faced by university students. According to decision perspectives on scarcity and opportunity cost as well as Conservation of Resources theory, high time pressure induces present-biased decision making, leading individuals to favor goals that offer immediate returns or are perceived as more urgent37. Within this cognitive framework, health behaviors—characterized by delayed and cumulative benefits—are more likely to be neglected or abandoned13. Empirical evidence is consistent with this pattern, showing that when time feels tight, adherence to health-related plans drops and willingness to engage in physical activity declines38.

Within the Theory of Planned Behavior, time pressure primarily undermines perceived behavioral control: compressed schedules raise the perceived difficulty and opportunity cost of exercising, which, per TPB, depresses intention and can shift evaluative beliefs (attitudes) toward less favorable assessments of exercise4. Conservation of Resources theory further predicts that perceived temporal scarcity triggers defensive allocation, prioritizing externally evaluated and urgent academic tasks while withholding time and effort from exercise39. Decision perspectives on present bias and progress salience indicate that when time feels tight, individuals overweight immediate outcomes and visible progress, thereby systematically deprioritizing behaviors with delayed and cumulative payoffs such as exercise40.

Taken together, reduced perceived control, resource reallocation, and the overweighting of immediacy provide a theory-driven account for a main effect of time pressure on both intention and attitude toward physical activity, independent of goal conflict. Accordingly, holding goal conflict constant, high time pressure is expected to yield lower behavioral intentions and less favorable attitudes toward exercise than low time pressure (formalized as Hypothesis 3 in Sect. "Research hypotheses").

Research gap and theoretical contribution: a triple-interaction perspective

Although prior studies have independently demonstrated adverse effects of goal conflict and time pressure on health behavior, theory suggests that the two constraints should interact and that their effects should accumulate over time. First, within the Theory of Planned Behavior, the two stressors jointly constrain perceived behavioral control: conflict raises perceived difficulty and opportunity cost, and time pressure compresses decision windows and narrows feasible action sets; together they reduce perceived control more than either factor alone41. Second, Conservation of Resources theory predicts resource loss spirals when threats co-occur; conflict and temporal scarcity both draw on limited time and attention, and their combination amplifies defensive allocation to externally evaluated tasks, persistently withholding resources from exercise42. Third, decision perspectives on scarcity, opportunity cost, and present bias imply attentional tunneling under time scarcity; when competing goals are active, immediacy weighting strengthens the preference for evaluatively salient tasks and accelerates the devaluation of delayed-benefit behaviors such as exercise43. Fourth, because these mechanisms recur each week, their joint impact should yield trajectory divergence rather than a single level shift, with the high-conflict × high-pressure condition showing the steepest decline. Together, these theories are complementary rather than redundant: TPB specifies the proximal pathway via perceived control and evaluation; Conservation of Resources explains why reallocation persists and can escalate; decision perspectives explain how scarcity elevates opportunity costs and induces present bias. This study contributes to research on health-behavior motivation under joint constraints by integrating TPB, Conservation of Resources, and decision perspectives to derive and test a conflict×pressure interaction and a time-divergent Week × Conflict × Pressure three-way interaction in a 2 × 2 × 4 longitudinal design.

Accordingly, averaged across Weeks 1–4, goal conflict and time pressure will interact such that motivation (behavioral intentions and attitudes) is lowest under high conflict × high pressure and highest under low conflict × low pressure, with the mixed conditions intermediate (formalized as Hypothesis 4 in Sect. "Research hypotheses"). Extending this logic across weeks, goal conflict and time pressure will interact with time: the high-conflict/high-pressure condition will show the steepest linear decline in behavioral intentions and attitudes, whereas the low-conflict/low-pressure condition will remain highest and comparatively stable (formalized as Hypothesis 5 in Sect. "Research hypotheses").

Research hypotheses

Taken together, goal conflict and time pressure represent two critical contextual variables that intensify competition for behavioral resources and impair decision-making efficiency, thereby posing significant psychological barriers and behavioral deviations in the execution of health-related actions. Under conditions of goal conflict and high time pressure, university students are particularly vulnerable to diminished motivation and disrupted engagement in health behaviors. While existing research has explored the individual effects of goal conflict and time pressure, their interactive mechanisms—especially how these effects evolve over time—remain insufficiently addressed by empirical studies.

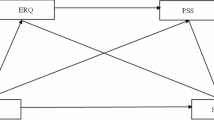

To fill this gap, the present study adopts a 2 (goal conflict: high vs. low) × 2 (time pressure: high vs. low) × 4 (time: Weeks 1–4) longitudinal experimental design and proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (Time Effect). On average across conditions, students’ motivational states will change systematically over Weeks 1–4: attitudes toward executing health behaviors will decline approximately linearly, whereas behavioral Intentions will show no systematic change (i.e., no main effect of time).

Hypothesis 2 (Main Effect of Goal Conflict). On average across Weeks 1–4, students in the high goal-conflict condition will report lower behavioral Intentions and less favorable attitudes toward executing health behaviors than students in the low goal-conflict condition (where both goals are active but scheduled in non-overlapping windows).

Hypothesis 3 (Main Effect of Time Pressure). On average across Weeks 1–4, students under high time pressure will report lower behavioral Intentions and less favorable attitudes toward executing health behaviors than students under low time pressure (ample time / flexible schedule).

Hypothesis 4 (Goal Conflict × Time Pressure Interaction). Averaged across Weeks 1–4, goal conflict and time pressure will interact such that motivation (behavioral intention and attitude) is lowest under high conflict × high pressure and highest under low conflict × low pressure, with the mixed conditions intermediate.

Hypothesis 5 (Longitudinal Interaction). Across Weeks 1–4, goal conflict and time pressure will interact over time (Week × Conflict × Pressure): the High-Conflict × High-Pressure condition will show the steepest linear decline in behavioral intention and attitude, whereas the Low-Conflict × Low-Pressure condition will remain highest and comparatively stable.

Experimental design

Experimental type and design structure

This study employed a 2 (goal conflict: high vs. low) × 2 (time pressure: high vs. low) × 4 (time: Weeks 1 to 4) mixed experimental design. Goal conflict and time pressure were treated as between-subjects independent variables, while time served as a within-subjects repeated-measures variable to examine dynamic changes in the dependent variables across four measurement points.

Based on the combination of independent variables, participants were assigned to one of four experimental groups: Group A (high goal conflict × high time pressure), Group B (high goal conflict × low time pressure), Group C (low goal conflict × high time pressure), and Group D (low goal conflict × low time pressure).

Participants (N = 88) were recruited using a convenience sampling method and were assigned to one of the four experimental groups (n = 22 per group) based on gender-stratified allocation. To ensure randomization, cross-tabulation and chi-square tests were conducted on pretest data prior to the experiment. The results indicated no significant gender distribution differences across the four groups (all ps > .05), confirming the initial group equivalence and supporting the assumptions of random assignment and baseline homogeneity. Prior to participation, all students were informed that the study aimed to investigate behavioral responses under conditions of goal conflict and time pressure, and they provided written informed consent.

Participants

A total of 88 university students were recruited via convenience sampling and equally assigned to four experimental groups (n = 22 per group) using gender-stratified allocation. Inclusion criteria were as follows: participants were full-time university students aged between 19 and 24, ensuring a consistent developmental stage and comparable levels of academic and life stress; all participants had a basic understanding of and prior engagement in health-related behaviors, thereby indicating sufficient cognitive familiarity with physical activity; none reported any serious physical illnesses or psychological disorders, and all were capable of independently completing online tasks without impairments that could interfere with participation; in addition, participants had reliable access to internet-enabled devices to complete online questionnaires according to the study timeline; and all voluntarily consented to participate after being fully informed of the study’s purpose, procedures, and ethical safeguards. Exclusion criteria included current engagement in psychological or physical rehabilitation, plans for prolonged leave or academic suspension during the study period, or the presence of severe social or cognitive impairments that could prevent timely task completion.

Situational manipulations and variable measurement

To manipulate goal conflict and time pressure, the experiment employed situational priming materials designed to simulate real-life goal-conflict and time-pressure conditions. The intervention lasted for four consecutive weeks. Each week, participants received written scenario materials corresponding to their assigned experimental group, which they read before completing the relevant questionnaires.

In the high goal conflict condition, participants were instructed to complete both an academic task and a physical exercise task within the same time frame, thereby activating perceived goal competition. In contrast, in the low goal conflict condition, both goals were present but scheduled in non-overlapping time windows, without invoking competing behavioral goals. For time pressure manipulation, the high time pressure condition specified strict time limits and emphasized task urgency, whereas the low time pressure condition removed time constraints and emphasized task flexibility and sufficiency of time.

Two customized items were developed to assess goal conflict, drawing on the conceptual framework of Goldstein’s conflict communication scale44. These items were designed to capture participants’ perceived tension between academic responsibilities and exercise goals. Specifically, they asked: “In this scenario, did you feel a conflict between your academic tasks and exercise goals?” and “To what extent did you perceive a strong conflict in prioritizing between academic and exercise-related demands?” In addition, following Goldstein’s conceptualization of intergoal interference and trade offs44, we included two manipulation check items: “At this moment, my academic and exercise goals interfered with each other” and “Pursuing both goals simultaneously requires sacrificing one goal to achieve the other.”

Time pressure was assessed using two context-specific items adapted from Van Der Lippe’s framework for measuring subjective time strain45. These items captured participants’ perceived temporal constraints in completing concurrent tasks. Specifically, participants responded to: “In this scenario, did you feel time was too tight to complete all required tasks?” and “Do you believe there was sufficient time to accomplish both academic and exercise-related tasks in this situation?” In line with Van Der Lippe’s notion of time scarcity and strain45, two manipulation check items were also included: “In this scenario, I felt under strong time pressure” and “There was enough time to complete both academic and exercise tasks” which was reverse coded.

Exercise Intentions was measured using two items adapted from the intention construct within Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior46. These items were designed to assess participants’ Intentions to engage in physical activity under varying cognitive demands. Specifically, the items stated: “In the current scenario, I am willing to make time for physical exercise,” and “Even when faced with heavy workload, I still intend to follow through with my exercise plan.”

Exercise attitude was measured following the evaluative structure outlined in Ajzen’s guidelines for constructing Theory of Planned Behavior questionnaires47. Two items were designed to assess the perceived value of maintaining physical activity under time constraints: “In the current scenario, I believe that maintaining regular exercise is valuable,” and “Given the current time schedule, I still consider sticking to my exercise routine a worthwhile choice.”

All manipulation and outcome items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree). Reverse-scored items were appropriately recoded prior to analysis. It should be emphasized that the above item selection adhered to the correspondence principle: each item pair originated from the same theoretical domain and was aligned on the same target behavior, action wording, context, and weekly temporal referent, serving as complementary indicators of a single latent construct. Each pair was designed to be complementary rather than redundant. For goal conflict, the two items respectively capture intergoal competition and conflict in time and resources; for time pressure, they capture subjective urgency and the objective scarcity of time or task load; for exercise intention, they capture planning or commitment and the perceived likelihood of enactment; for exercise attitude, they capture instrumental and affective evaluations. To reduce methodological redundancy and enhance sensitivity to week-level variability, while keeping both items aligned with the same latent construct, near-synonymous wording was intentionally avoided.

Intervention procedure

We implemented a four-week online protocol administered at a fixed time each Monday. Before randomization, participants were explicitly instructed to anchor the provided vignettes to their actual weekly timetables and tasks and to refrain from pre-committing to a priority between the two goals. No prioritization decision or task execution was required; the manipulation concerned goal conflict, operationalized via the goals’ time-window relation such that overlap defined high conflict and non-overlap defined low conflict, and time pressure at two levels, high and low. Participants were then randomly assigned to a 2 × 2 between-subjects manipulation of goal conflict (high vs. low) and time pressure (high vs. low), which remained constant across the four weeks. At each session, participants logged into the platform, reviewed the week’s procedures, condition-specific prompts, and scenario materials, and then completed scenario-based reflections and questionnaires anchored to that week’s real obligations. For example, in the high-pressure × high-conflict condition, the prompt stated: “You are operating under limited available time while pursuing two goals in parallel. This week, reflect under the frame that ‘a course paper is due at midnight and you have only just begun writing, yet you are also strongly inclined to exercise; the two goals directly compete within the same time window,’ and answer the subsequent items accordingly.” Prompts emphasized this time-window operationalization of goal conflict, with overlap defined as high conflict and non-overlap defined as low conflict, and they framed time pressure as high or low to elicit appraisals of conflict and pressure; they did not ask participants to resolve the situation by choosing one goal over the other. After viewing the scenario demonstration, participants completed an online survey battery including demographic items and additional psychometric scales.

We did not require participants to execute any academic or exercise tasks. At no point were participants asked to select or implement a goal priority. Instead, effects were elicited under each week’s real constraints by anchoring the vignettes to participants’ actual schedules, thereby inducing subjective goal conflict and perceived time scarcity and capturing responses on proximal motivational indicators (intention, attitude). In the participating institutions, students concurrently take physical education and lecture-based courses with clear weekly coursework and exercise routines; the anchoring step thus mapped abstract scenarios onto participants’ operative goal systems, enhancing ecological validity and the replicability of measurement. Study links were delivered at the same weekly time point with a single reminder within 12 hours; each session lasted approximately 5–10 minutes, and the four-week protocol was identical across waves.

Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4 illustrate the intervention materials used in Week 1 for each experimental condition. All character illustrations were adapted from the OpenDoodles repository under a permissive license.

Week 1 intervention illustration for Group A: High goal conflict × High time pressure. Note (applies to Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4). The figures depict the time window operationalization of goal conflict, with overlap defining high conflict and separation in time defining low conflict, and they show time pressure at two levels, high and low. Participants were not asked to execute tasks, to make any prioritization decision, or to choose between goals; the materials served only to provide context for the subsequent reflections and questionnaires.

Throughout the four-week experimental period, each participant completed the assigned tasks weekly. Data collection followed a repeated-measures format, enabling the tracking of dynamic changes in health behavior intention and attitude over time.

Sensitivity analysis of interaction effects

To delineate the detection thresholds for interaction effects under the fixed sample size and measurement structure, we conducted a parametric sensitivity analysis. Using the same fixed-effects specification as in the primary models (week, goal conflict, time pressure, and their interactions), we obtained coefficient standard errors and Satterthwaite degrees of freedom. At a two-sided significance level of α = 0.05, the minimum detectable effect (MDE) at 80% power was derived from the noncentral t distribution, defined by Pr(|Tdf(λ)| > t{1−α/2, df}) = 0.80, which yields MDE = λ × SE. Week was coded 0–3; accordingly, the three-way interaction coefficient represents the incremental difference per additional week across combinations of conflict and pressure. This analysis characterizes detection sensitivity and does not alter the primary conclusions.

Multiple-testing control

To control the family-wise error rate (two-sided α = .05), Holm–Bonferroni adjustments were applied within pre-specified families for each outcome (Intention, Attitude), covering tests of Week and its interactions with Goal Conflict and Time Pressure (including the three-way) and their planned within-subjects linear contrasts; when sphericity was violated, inferences followed the multivariate tests and those p values entered the adjustment. A separate Holm–Bonferroni adjustment was applied to the between-subjects main effects of Goal Conflict and Time Pressure and their interaction. Adjusted p values are reported as p₍Holm₎ (otherwise p denotes the unadjusted value). Scheffé post hoc comparisons among the four groups already control the family-wise error rate and were not further adjusted. Manipulation checks were treated as validity assessments and excluded from multiplicity control. Effect sizes are reported as partial η2 with 95% confidence intervals.

Result

For two-item scales, internal consistency was indexed by the inter-item Pearson correlation (r) with 95% confidence intervals derived via Fisher’s z transformation. We additionally report the Spearman–Brown reliability coefficient α (equivalent to Cronbach’s α for two-item scales), with 95% confidence intervals obtained by transforming r using α = 2r/(1 + r). The manipulation-check scales showed high consistency: goal conflict r = .785, 95% CI [.689, .854], α = .880, 95% CI [.816, .921]; time pressure r = .743, 95% CI [.632, .824], α = .853, 95% CI [.775, .904] (both n = 88). By contrast, the two-item indices (i.e., for each construct, the mean of its two items after any necessary reverse coding) used in the primary analyses exhibited low-to-moderate inter-item correlations in the full sample: goal conflict r = .151, 95% CI [.031, .267], α = .262, 95% CI [.060, .421]; time pressure r = .261, 95% CI [.145, .370], α = .414, 95% CI [.253, .540]; behavioral intention r = .163, 95% CI [.043, .278], α = .280, 95% CI [.082, .435]; attitude toward the behavior r = .197, 95% CI [.078, .310], α = .329, 95% CI [.145, .473] (all n = 352). In this two item design, each pair targets complementary facets of the same construct under a common weekly frame. Accordingly, lower interitem correlations, particularly in early weeks, are typical for complementary rather than redundant items and mainly attenuate effect sizes toward zero instead of creating spurious associations. Convergence is supported by complementary checks, and the inferences match the index based analyses (see Supplementary Tables 1, 2, 3, 4). Because the attainable upper bound of α in a two-item instrument is jointly constrained by item count and inter-item correlation—and broad constructs typically yield modest r—the reported α values fall within the expected range for short two-item forms. The strong consistency of the manipulation-check scales indicates stable identification of the experimental manipulations.

Before hypothesis testing, manipulation checks were conducted to verify that the experimental inductions operated as intended. Internal consistency of the two-item composites assessing perceived goal conflict and perceived time pressure was high (Cronbach’s α = .879, 95% CI [.816, .921]; and α = .853, 95% CI [.775, .904], respectively). Perceived goal conflict was higher in the high-conflict than in the low-conflict condition, t(86) = 26.94, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 5.74, 95% CI [4.79, 6.70]. Perceived time pressure was higher in the high-pressure than in the low-pressure condition, t(86) = 25.79, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 5.50, 95% CI [4.58, 6.42]. Condition means (M ± SD) were as follows: goal conflict, low conflict × low pressure 2.54 ± 0.41; low conflict × high pressure 2.87 ± 0.37; high conflict × low pressure 5.04 ± 0.38; high conflict × high pressure 5.02 ± 0.40; time pressure, low conflict × low pressure 2.81 ± 0.34; low conflict × high pressure 5.08 ± 0.44; high conflict × low pressure 2.84 ± 0.40; high conflict × high pressure 4.93 ± 0.41. Additionally, to further substantiate the manipulation checks, two 2 × 2 between-subjects ANOVAs were conducted (all ANOVA p-values Holm–Bonferroni–adjusted). Perceived goal conflict showed a large main effect of Goal Conflict, F(1,84) = 774.19, p < .001, ηp2 = .902, whereas Time Pressure and the Goal Conflict×Time Pressure interaction were nonsignificant (p = .192 and .172). Conversely, perceived time pressure showed a large main effect of Time Pressure, F(1,84) = 663.19, p < .001, ηp2 = .888, whereas Goal Conflict and the interaction were nonsignificant (p = .556 and .556). Taken together, the two situational manipulations were successful, producing the intended perceptual changes with selective effects confined to their respective checks; no cross-factor main effects or interactions emerged, indicating that the manipulations were effective and orthogonal.

Verification of the main effect of time

To examine the main effect of time on health behavior intention and attitude, Mauchly’s test of sphericity was first conducted (see Table 1). The results indicated that the assumption of sphericity was violated for both behavioral intention (p = .012) and behavioral attitude (p < .001). Accordingly, multivariate tests were employed to further analyze the effect of time, based on the outcomes of the sphericity test.

In terms of behavioral intention, multivariate tests revealed that the effect of time was not statistically significant, F(3, 85) = 1.775, p = .158, ηp2 = .059, 95% CI [0.000, 0.156]. However, a significant main effect of time was observed for behavioral attitude, F(3, 85) = 3.966, p = .011, ηp2 = .123, 95% CI [0.008, 0.244].

However, a significant main effect of time was observed for behavioral attitude, F(3, 85) = 3.966, p = .011, ηp2 = .123, 95% CI [0.008, 0.244], suggesting that students’ attitudes toward executing health behaviors changed meaningfully throughout the study. Specifically, the data revealed a linear trend, F(1, 87) = 4.887, p = .030, ηp2 = .053, indicating a significant linear decline in attitudes over Weeks 1–4. Detailed results are presented in Table 2.

To further examine the temporal trend in university students’ attitudes toward health behavior during the experimental period, a within-subjects contrast analysis was conducted. As shown in Table 3, the linear trend for behavioral attitude across time was statistically significant, F(1, 87) = 4.887, p = .030, partial η2 = .053, 95% CI [0, .141], indicating a significant linear change in students’ attitudes toward health behavior execution over the course of the study.

In contrast, neither the quadratic trend (F(1, 87) = 0.038, p = .845, partial η2 < .001) nor the cubic trend (F(1, 87) = 0.004, p = .952, partial η2 < .001) reached statistical significance, indicating that the change in behavioral attitude did not follow a nonlinear pattern. Therefore, students’ attitudes toward health behavior during the four-week experimental period can be interpreted as displaying a consistent and stable linear progression.

This finding further reinforces the results of the earlier multivariate analysis, which identified a significant main effect of time on behavioral attitude. It suggests that the experimental context or repeated exposure to the intervention may have contributed to a significant linear decline in students’ attitudes toward engaging in health-promoting behaviors, rather than producing fluctuating or nonlinear responses.

As illustrated in Fig. 5, students’ attitudes toward executing health behaviors exhibited a steady decline over the four-week experimental period. The estimated marginal mean in Week 1 was approximately 3.8, which decreased progressively each week, reaching around 3.1 by Week 4. This downward trend closely approximates a linear pattern, aligning with the aforementioned statistical results and further confirming the significant linear change in behavioral attitude over time.

No inflection points or substantial fluctuations were observed in the graph, further supporting the results of the within-subjects contrast analysis, in which neither the quadratic nor cubic trends reached statistical significance. This indicates that the change in behavioral attitude followed a stable, linear trajectory. The findings suggest that under the experimental conditions involving goal conflict and time pressure, students’ positive attitudes toward health behaviors gradually diminished—potentially as these behaviors were increasingly deprioritized in favor of academic tasks or in response to perceived time constraints.

In summary, these results partially support Hypothesis 1: students’ attitudes toward health behavior execution changed significantly over time, while their behavioral Intentions did not exhibit a significant time effect.

Verification of the main effect of goal conflict

To examine the effects of time and goal conflict on students’ Intentions and attitudes toward health behavior execution, Mauchly’s test of sphericity was first conducted. The results indicated that the assumption of sphericity was violated for both behavioral intention (W = 0.868, p = .035) and behavioral attitude (W = 0.738, p < .001). Therefore, subsequent analyses were interpreted based on multivariate test results (see Table 4).

The multivariate analysis of variance (Table 5) revealed that the interaction between goal conflict and time was statistically significant for both behavioral intention, F(3, 84) = 3.468, p = .020, ηp2 = .110, 95% CI [0.010, 0.228], and behavioral attitude, F(3, 84) = 7.610, p < .001, ηp2 = .214, 95% CI [0.106, 0.330]. These findings indicate that goal conflict significantly moderated students’ Intentions and attitudes toward health behavior execution, and that this effect varied dynamically over time.

To further examine the temporal dynamics of students’ behavioral intention and attitude toward health behaviors during the experimental period, within-subjects contrast analyses were conducted to assess the interaction effects of time and goal conflict. As shown in Table 6, a significant linear interaction was observed for behavioral intention across time and goal conflict grouping (F(1, 86) = 10.569, p = .002, partial η2 = .109, 95% CI [0.017, 0.255]). In contrast, neither the quadratic (F = 0.152, p = .697, ηp2 = .002, 95% CI [0.000, 0.062]) nor the cubic (F = 0.026, p = .873, ηp2 < .001, 95% CI [0.000, 0.051]) interaction trends were statistically significant.

These results suggest that the variation in behavioral intention over time differed systematically between goal conflict conditions, following a predominantly linear trajectory. Specifically, students in different conflict-level groups demonstrated increasingly divergent patterns of intention across the four-week period.

For behavioral attitude, the linear interaction between time and goal conflict was also significant (F(1, 86) = 18.700, p < .001, partial η2 = .179, 95% CI [0.055, 0.337]), while both the quadratic (F = 0.133, p = .716, ηp2 = .002, 95% CI [0.000, 0.061]) and cubic trends (F = 0.003, p = .957, ηp2 < .001, 95% CI [0.000, 0.046]) were non-significant. This indicates that students’ attitudes toward health behavior execution also followed a predominantly linear divergence across goal conflict conditions.

In other words, the impact of goal conflict on behavioral attitude unfolded in a consistent linear pattern, with attitude differences between high and low conflict groups widening progressively over time.

To provide a more intuitive illustration of the changes in students’ health behavior intention and attitude under different goal conflict conditions throughout the experiment, estimated marginal means (EMMs) were plotted to visualize the interaction effects (see Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9).

Figures 6 and 8 display the estimated marginal means of behavioral intention and attitude, respectively, across four time points for both high and low goal conflict groups. As shown, the low goal conflict group consistently scored higher than the high conflict group across all weeks, with the gap widening over time. Notably, by Week 4, both intention and attitude scores in the high goal conflict group had dropped to their lowest levels, whereas the low goal conflict group maintained relatively stable scores, with a slight increase observed in attitude.

Figures 7 and 9 further depict the longitudinal trajectories of each goal conflict group over the four-week experimental period. In Fig. 7, the high goal conflict group shows a steady decline in behavioral intention from Week 1 to Week 4, while the low conflict group maintains a consistently higher level of intention with minimal fluctuations. The trend for behavioral attitude in Fig. 9 is even more pronounced: participants in the high goal conflict group exhibit a sharp decline in attitude across the four weeks, reaching nearly a score of 2 by Week 4. In contrast, the low goal conflict group remains relatively stable throughout the experiment, with a slight increase observed in Week 4.

These graphical patterns align with the significant interaction effects reported in Table 6, offering a visual confirmation of the divergent trajectories in students’ behavioral intention and attitude under different levels of goal conflict.

To examine the overall impact of goal conflict on students’ Intentions and attitudes toward health behavior execution, a between-subjects main effect analysis was conducted (see Table 7). The results revealed a significant main effect of goal conflict on behavioral intention, F(1, 86) = 31.846, p < .001, ηp2 = .270, 95% CI [0.121, 0.433], as well as on behavioral attitude, F(1, 86) = 36.586, p < .001, ηp2 = .298, 95% CI [0.145, 0.460].

Estimated marginal means indicated that participants in the high goal conflict condition reported significantly lower behavioral intention scores (M = 3.014, SE = 0.145, 95% CI [2.727, 3.302]) compared to those in the low conflict condition (M = 4.168, SE = 0.145, 95% CI [3.880, 4.455]). Similarly, behavioral attitude scores were significantly lower in the high conflict group (M = 2.864, SE = 0.126, 95% CI [2.614, 3.113]) than in the low conflict group (M = 3.938, SE = 0.126, 95% CI [3.688, 4.187]).

These findings suggest that under high goal conflict conditions, students’ motivation and attitudes toward engaging in health behaviors are significantly constrained. This provides further support for Hypothesis 2, which posits that high levels of goal conflict significantly weaken both behavioral intention and attitude toward health behavior execution among university students.

Verification of the main effect of time pressure (hypothesis 3)

To examine the effect of time pressure on students’ behavioral intention and attitude toward health behavior execution, Mauchly’s test of sphericity was conducted prior to the repeated-measures multivariate analysis of variance (see Table 8). The results indicated a violation of the sphericity assumption for both behavioral intention (W = 0.861, p = .026) and behavioral attitude (W = 0.739, p < .001). Accordingly, subsequent analyses were based on multivariate test results.

The multivariate test results (see Table 9) revealed a significant interaction between time pressure and experimental week for behavioral intention, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.729, F(3, 84) = 10.419, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.271, 95% CI [0.109, 0.405]. This indicates that the trajectory of behavioral intention across the four-week period differed significantly depending on the level of time pressure. In other words, time pressure, as a situational variable, exerted a cumulative effect on students’ execution of health behaviors over time.

Similarly, a significant interaction effect was observed for behavioral attitude, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.847, F(3, 84) = 5.067, p = .003, partial η2 = 0.153, 95% CI [0.023, 0.281], suggesting that students’ attitudes toward health behavior were also moderated by varying levels of time pressure and evolved differently throughout the experimental period.

To further clarify the nature of the time effect and its interaction with time pressure, within-subjects contrast analyses were conducted (see Table 10). For behavioral intention, the linear interaction between time and time pressure was significant, F(1, 86) = 28.469, p < .001, partial η2 = .249, 95% CI [0.104, 0.411], while the quadratic (F = 0.055, p = .816) and cubic (F = 0.014, p = .904) trends were not significant. This indicates that changes in behavioral intention followed a primarily linear downward trajectory, and that this pattern diverged significantly between the high and low time pressure groups.

Similarly, for behavioral attitude, a significant linear interaction was observed between time and time pressure, F(1, 86) = 12.652, p = .001, partial η2 = .128, 95% CI [0.026, 0.279], whereas both the quadratic (p = .716) and cubic (p = .957) trends were non-significant. This suggests that the trajectory of attitude change was also predominantly linear and moderated by the level of time pressure.

To further illustrate the dynamic effects of time pressure on university students’ behavioral intention and attitude toward health behavior execution, a series of estimated marginal means plots were generated (see Figs. 10, 11, 12, 13). Figures 10 and 12 display the distribution of behavioral intention and attitude, respectively, across four weekly time points for high and low time pressure groups. Figures 11 and 13 present the longitudinal trajectories of behavioral intention and attitude within each time pressure condition over the course of the experimental period.

As shown in Figs. 10 and 11, students in the low time pressure group exhibited consistently higher levels of behavioral intention, with a slight upward trend over time. In contrast, the high time pressure group demonstrated a clear downward trajectory, with intention scores steadily decreasing and reaching the lowest point by Week 4. This pattern reflects a sustained negative trend in behavioral intention under conditions of high time pressure.

Figures 12 and 13 illustrate the changes in behavioral attitude under different time pressure conditions. In the low time pressure group, attitude scores remained stable or slightly increased throughout the experimental period. In contrast, the high time pressure group exhibited a continuous and pronounced decline in attitude over the four weeks. By Week 4, the average attitude score in the high pressure group had dropped to approximately 2, significantly lower than that of the low pressure group. This pattern further confirms the detrimental impact of time pressure on students’ attitudes toward engaging in health behaviors.

These trend graphs clearly visualize the moderating role of time pressure in students’ health behavior responses. The observed patterns are consistent with the multivariate analysis results and provide intuitive and compelling graphical support for Hypothesis 3.

Further analysis revealed that participants in the high time pressure group scored significantly lower than those in the low pressure group on both behavioral intention and attitude. Specifically, the estimated marginal mean for behavioral intention was M = 2.946 (SE = 0.138, 95% CI [2.672, 3.220]) in the high pressure group, compared to M = 4.236 (SE = 0.138, 95% CI [3.962, 4.509]) in the low pressure group. For behavioral attitude, the high pressure group also reported a lower mean score (M = 2.966, SE = 0.134, 95% CI [2.699, 3.233]) than the low pressure group (M = 3.835, SE = 0.134, 95% CI [3.568, 4.102]).

Consistent with the significant main effects reported in Table 11—behavioral intention: F(1, 86) = 43.892, p < .001, η2 = .338, 95% CI [0.179, 0.497]; behavioral attitude: F(1, 86) = 20.910, p < .001, η2 = .196, 95% CI [0.066, 0.356]—time pressure exerted a robust negative influence on both outcome variables. In other words, high time pressure significantly undermined students’ motivation and evaluative attitudes toward engaging in health behaviors, thereby supporting the central proposition of Hypothesis 3.

Verification of the interaction effect

To examine the interactive effects of goal conflict and time pressure on students’ behavioral intention and attitude toward health behavior execution, Mauchly’s test of sphericity was conducted first (see Table 12). The results indicated that the assumption of sphericity was violated for both behavioral intention (W = .844, p = .015) and behavioral attitude (W = .643, p < .001). Therefore, subsequent analyses were based on multivariate test results.

The results of the repeated-measures multivariate analysis of variance (see Table 13) revealed significant three-way interaction effects of goal conflict × time pressure × time on both behavioral intention (Wilks’ Lambda = .834, F(3, 82) = 5.427, p = .002, partial η2 = .166, 95% CI [0.031, 0.295]) and behavioral attitude (Wilks’ Lambda = .747, F(3, 82) = 9.247, p < .001, partial η2 = .253, 95% CI [0.095, 0.392]). These findings indicate that the joint effect of goal conflict and time pressure on students’ health behavior responses—both in terms of intention and attitude—varies significantly over time.

To further clarify the temporal dynamics of the interaction between goal conflict and time pressure, within-subjects contrast analyses were conducted on the three-way interaction of goal conflict × time pressure × week. The results are presented in Table 14.

For behavioral intention, the three-way interaction showed a significant linear trend, F(1, 84) = 15.862, p < .001, partial η2 = .159 , 95% CI [0.042, 0.316], while both the quadratic (F = 0.037, p = .848, partial η2 = .000[, 95% CI [0.000, 0.055]) and cubic trends (F = 0.114, p = .737, partial η2 = .001[, 95% CI [0.000, 0.060]) were non-significant. This indicates that changes in behavioral intention followed a predominantly linear pattern over time, with sustained divergence across the different contextual combinations of goal conflict and time pressure.

Similarly, for behavioral attitude, the linear component of the three-way interaction also reached statistical significance, F(1, 84) = 14.284, p < .001, partial η2 = .145, 95% CI [0.034, 0.300], whereas the quadratic (F = 0.972, p = .327, partial η2 = .011[, 95% CI [0.000, 0.115]) and cubic (F = 0.265, p = .608, partial η2 = .003[, 95% CI [0.000, 0.070]) trends were not significant. These findings further suggest that attitude changes were primarily linear and significantly shaped by the interaction between goal conflict and time pressure over the course of the experiment.

To further visualize the interactive effects of goal conflict and time pressure on health behavior execution throughout the experimental period, estimated marginal means plots were generated to illustrate the interaction trends over time (see Figs. 14, 15, 16, 17).

Figure 14 illustrates the interaction effect of time and experimental condition on behavioral intention. The results show a continuous decline in intention over time for the high goal conflict + high time pressure group, reaching its lowest point by Week 4. In contrast, the low goal conflict + low time pressure group maintained consistently high intention scores with minimal variation.

Figure 15 further clarifies these patterns from a condition-by-time perspective, depicting how behavioral intention scores evolved across weeks within each group. The graph clearly reveals a growing divergence between groups over time, with increasingly differentiated intention levels across experimental conditions.

Similarly, Figs. 16 and 17 depict the temporal trajectories of behavioral attitude throughout the experimental period. Figure 16 shows a marked linear decline in attitude among participants exposed to high goal conflict and high time pressure, whereas those in the low goal conflict + low time pressure group exhibited relatively stable attitude levels with minimal fluctuation.

Figure 17 further illustrates the group-wise comparisons of attitude scores at each time point, providing a visual representation of the three-way interaction effect and its influence on attitude change over time.

The overall trend patterns closely align with the multivariate analysis results, further reinforcing the significant three-way interaction effect of goal conflict × time pressure × time on both behavioral intention and attitude toward health behavior execution.

The between-subjects analysis revealed a significant interaction between goal conflict and time pressure for both behavioral intention (F(1, 84) = 44.642, p < .001, partial η2 = .347, 95% CI [0.186, 0.507]) and behavioral attitude (F(1, 84) = 31.830, p < .001, partial η2 = .275, 95% CI [0.123,0.439]). These findings indicate that different combinations of goal conflict and time pressure exert distinct effects on students’ health behavior responses. The results provide empirical support for Hypothesis 4, confirming the presence of an interaction effect between goal conflict and time pressure in shaping health behavior outcomes. Detailed statistical results are presented in Table 15.

Verification of the tracking hypothesis

For behavioral intention, descriptive statistics revealed that Group D (Low Goal Conflict + Low Time Pressure) had the highest average score (M = 5.222, SD = 0.532), followed by Group B (M = 3.250, SD = 0.628) and Group C (M = 3.114, SD = 0.564), while Group A (High Goal Conflict + High Time Pressure) showed the lowest score (M = 2.778, SD = 0.569). Levene’s test indicated that the assumption of homogeneity of variances was met, F = 0.446, p = .721.

One-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of condition on behavioral intention, F(3, 84) = 81.431, p < .001, η2 = .744, 95% CI [0.646, 0.811], indicating that the combination of goal conflict and time pressure had a substantial impact on intention. Further post hoc comparisons using Scheffé’s test showed that Group D reported significantly higher behavioral intention than Group A (M difference = 2.443, p < .001), Group B (M difference = 1.972, p < .001), and Group C (M difference = 2.108, p < .001), with all differences reaching statistical significance. The difference between Group A and Group B approached marginal significance (M difference = − 0.472, p = .067), while no significant difference was observed between Group A and Group C (M difference = − 0.335, p = .297).

Following the analysis of group differences in behavioral intention, a one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine whether the four combinations of goal conflict and time pressure also significantly affected behavioral attitude. Descriptive statistics showed that Group A (High Goal Conflict + High Time Pressure) had the lowest average attitude score (M = 2.796, SD = 0.630), followed by Group B (M = 2.932, SD = 0.613) and Group C (M = 3.136, SD = 0.678), while Group D (Low Goal Conflict + Low Time Pressure) reported the highest score (M = 4.739, SD = 0.503). Levene’s test confirmed the assumption of homogeneity of variances, F = 1.131, p = .341, indicating that the data met the prerequisite for conducting ANOVA.

One-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of condition on behavioral attitude, F(3, 84) = 48.310, p < .001, η2 = .633, 95% CI [0.494, 0.737], indicating that the combination of goal conflict and time pressure had a substantial impact on students’ attitudes toward health behavior execution. Subsequent Scheffé post hoc comparisons showed that Group D exhibited significantly higher attitude scores than Group A (M difference = 1.943, p < .001), Group B (M difference = 1.807, p < .001), and Group C (M difference = 1.602, p < .001), with all differences reaching statistical significance. However, no significant differences were found among the other group pairs (i.e., A vs. B, A vs. C, and B vs. C), as all p-values exceeded .05.

Sensitivity and power analysis

Under a fixed sample size of N=88 and two-sided α=.05, the sensitivity analysis indicated the minimal detectable effects at 80% power were 1.03 points on a 1–7 scale for Intentions and attitude when testing the two-way interaction on four-week individual means, and 1.98 and 1.88 points per week for the three-way interaction expressed as individual weekly slopes (Intentions slope and attitude slope, respectively). The MDE is the smallest true effect that would be detected with 80% power given N=88 and a two-sided α = .05; it describes the long-run sensitivity of the design rather than a per-sample decision boundary. Consequently, when the true effect is smaller than the MDE, statistical significance can still occur in a given sample because the test’s power for such effects is nonzero even though it is below 80%; conversely, an effect at or above the MDE can be nonsignificant with probability up to 20%. These outcomes reflect sampling variability and do not alter the interpretation of the point estimates or their 95% confidence intervals.

To enable a clear comparison between the MDE and the observed results, all key effects are reported in the same units as the thresholds. For four-week mean scores, the difference for Intentions is 1.15 (95% CI [0.42, 1.87]) with a corresponding threshold of 1.03; for Attitude, the difference is 1.18 (95% CI [0.46, 1.90]) with a threshold of 1.03. For weekly rates of change, the difference for Intentions is 1.70 points per week (95% CI [0.32, 3.09]) with a threshold of 1.98; for Attitude, the difference is 1.68 points per week (95% CI [0.37, 3.00]) with a threshold of 1.88. Overall, the four-week mean estimates exceed the threshold and are approximately one scale point in magnitude, whereas the weekly change estimates are close to but below the threshold. These findings indicate that the effect on four-week mean levels exceeds the sensitivity threshold with relatively robust evidence, whereas the effect on weekly rates of change is close to but does not reach the threshold, and the evidence is suggestive and comparatively limited.

Relative to these detection thresholds, all interaction tests remained significant after the Holm–Bonferroni correction. For the two-way interaction (four-week means), Intentions: b = 1.148, 95% CI [0.423, 1.873], p(Holm) = .007, partial η2 = .106; attitude: b = 1.182, 95% CI [0.461, 1.902], p(Holm) = .006, partial η2 = .112. For the three-way interaction (weekly slopes), Intentions slope: b = 1.705 points per week, 95% CI [0.318, 3.091], p(Holm) = .026, partial η2 = .066; attitude slope: b = 1.682 points per week, 95% CI [0.366, 2.997], p(Holm) = .026, partial η2 = .071. Overall, the design provides adequate sensitivity to medium-sized two-way interactions, whereas power is comparatively limited for small three-way interactions.

Multiple-testing correction

All focal tests were evaluated under Holm–Bonferroni control within their respective analysis families. After adjustment, effects reported as significant remained significant, and non-significant effects remained non-significant. Tables present adjusted p values (and partial η2 with 95% CIs); Scheffé post hoc comparisons required no further adjustment because they already control the family-wise error rate.

Discussion and conclusion

Cognitive dynamics across time: attitudinal change in motivational constructs

The study first confirmed the main effect of time on health behavior responses. Results indicated a significant linear decline in students’ attitudes toward health behavior execution as the experiment progressed, while behavioral intention remained relatively stable. We characterize this pattern as a gradual attitudinal decline across weeks alongside comparatively stable intention.

According to the Theory of Planned Behavior, discrepancies between attitude and intention can emerge from the interplay of perceived behavioral control and external situational demands. Within this framework, the observed temporal divergence at the motivational level is consistent with repeated exposure to goal conflict and time pressure, which shifts perceived control and evaluative priorities. We therefore interpret the decline as a motivational shift under dual demands rather than an index of behavior change. Given the self-report measures, single-university sample, and four-week duration, the generalizability and durability of this pattern should be viewed cautiously; longer follow-ups with objective activity indicators would strengthen inferences. In practical terms, intervention approaches that target time management, action planning, and goal shielding may help stabilize attitudes when goal conflict and time pressure co-occur.

Allocative strain under goal conflict: a resource-limited perspective on cognitive priority

Across the four-week period, higher goal conflict was associated with lower motivational indices (Intentions and attitudes). At multiple assessments, participants in the high-conflict condition reported lower Intentions and attitudes than those in the low-conflict condition, with between-group differences widening over time. This pattern is consistent with accounts of goal-resource competition and aligns with a cognitive-priority view under resource constraints48. Within such accounts, individuals may reallocate cognitive and motivational resources by prioritizing goals according to immediacy, outcome certainty, and evaluative pressure, which can place health behaviors at a relative disadvantage. In academic contexts, externally evaluated performance demands (e.g., grades, deadlines) may receive preferential prioritization relative to physical activity goals, reflecting a context-contingent bias in goal selection rather than a definitive inhibition of behavior. Interpretations are confined to motivational constructs; behavioral outcomes were not measured, and generalizability beyond a single-university, four-week design warrants caution.

Cognitive shortcuts under time pressure: present-bias–consistent patterns in motivational constructs

Across the four-week period, higher time pressure was associated with lower Intentions and attitudes, with the high-pressure condition showing a more negative trajectory over time. This pattern is consistent with accounts in which time pressure increases reliance on immediacy-oriented, heuristic decision processes and aligns with present-bias/delay-discounting interpretations at the motivational level49. Within this perspective, immediacy, feedback salience, and external evaluation may receive priority relative to health-related goals under tight temporal constraints. Interpretations are confined to motivational constructs; behavioral outcomes were not assessed, and we therefore refrain from claims about behavioral depletion. Given the self-report measures, single-university sample, and four-week duration, the generalizability and durability of these time-pressure effects warrant caution and should be examined in longer designs that incorporate objective activity indicators or intervention tests.

Temporal dynamics of the three-way interaction: divergent motivational trajectories under dual demands

One of the theoretical contributions of this study lies in its first systematic examination of the three-way interaction—goal conflict × time pressure × time—on health behavior. Across four weeks, the high-conflict + high-pressure condition showed a steeper decline in Intentions and attitudes than other conditions, whereas the low-conflict + low-pressure condition remained comparatively stable.

In contrast, the low-conflict + low-pressure group maintained a relatively high and stable level of motivation, reflecting strong behavioral self-regulation. These divergent trajectories highlight the differentiated mechanisms of behavioral system regulation in dynamic task environments, suggesting that behavioral responses are not static outcomes of decision-making, but rather evolving processes shaped by the interplay of cognitive resources, contextual stress, and psychological resilience. Interpretations are confined to motivational constructs; behavioral outcomes were not assessed. Generalizability and durability warrant caution given the single-university sample, self-report measures, and four-week duration. Future work should test whether these trajectories translate into behavioral differences and whether targeted supports (e.g., time-management or goal-shielding interventions) can attenuate the observed decline.

Sensitivity-calibrated inference and evidential scope

Sensitivity delineates the scope of claims this study can make. Short two-item forms prioritize content coverage, which tends to attenuate estimates toward zero and yields conservative rather than inflated effect sizes. Within this measurement context, internal consistency indices alone are insufficient to establish construct validity; interpretation rests on content validity together with convergent and discriminant evidence. Convergent checks documented in Supplementary Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4 indicate that the joint effects of goal conflict and time pressure are robust in direction and statistically reliable across analytic views. Accordingly, directional claims fall within the study’s evidential scope. Effect magnitudes should be interpreted conservatively, and higher-order time-dependent patterns approached cautiously. Replication with extended follow-up and expanded item sets is warranted. Within this scope, the main effects of goal conflict and time pressure and their interaction lie within the design’s detectable range and survive multiple testing correction and robustness analyses; therefore, goal conflict and time pressure can be treated as reliable constraints on motivation for health behavior. Higher-order patterns involving change across weeks lie at the edge of the design’s resolution. The current evidence is better treated as a working hypothesis of week-to-week accumulation rather than a settled conclusion, avoiding the mistake of reading random fluctuation in a single sample as a necessary trend. On this basis, a tiered interpretation is appropriate: offer clear but restrained theoretical statements about the two-factor constraints, and remain cautious about time-dependent accumulation. Practically, priority should be given to reducing goal conflict and easing time pressure to support sustained motivation; theoretically, tests of accumulation require larger samples, longer follow-up, and finer weekly measurement to establish the existence, magnitude, and conditions of the pathway and to further explicate mechanisms of resource competition and attentional allocation.

Intervention implications under goal conflict and time pressure

Evidence from campus based programs indicates that structured planning, time management training, and self regulation supports can improve physical activity participation and related motivational indicators among students49. These approaches act through mechanisms specified by the Theory of Planned Behavior, including increases in perceived behavioral control and intention strength, and through action control processes that narrow the intention–behavior gap52. Future trials conducted under conditions of goal conflict and time pressure would directly test whether strengthening planning and perceived control stabilizes attitudes across weeks.

Limitations and directions for future research

Although this study systematically revealed the dynamic influence of goal conflict and time pressure on behavioral intention and attitude toward health behaviors—contributing both theoretical insights and practical value—it also has several limitations.First, this study indexed motivational constructs (intention, attitude) rather than objectively verified physical activity; thus, inferences should be restricted to proximal motivation rather than behavioral enactment. Future work should include behavioral endpoints to test whether the observed trajectories translate into actual behavior change. Second, participants were drawn from a single university, which limits generalizability; multi-site, cross-major, and cross-cultural replications with probability or stratified sampling would strengthen external validity. Third, outcomes and manipulation checks relied on self-report, which is vulnerable to social desirability and common-method variance under repeated measurement; integrating objective behavioral endpoints (e.g., accelerometry, app-logged activity, time-use diaries), physiological indicators (e.g., HR/HRV, sleep), and brief EMA/peer reports—while expanding two-item indices and establishing longitudinal measurement invariance—would improve validity and precision. Then, the four-week window enabled dynamic observation but may be insufficient to capture longer-term formation, erosion, and recovery of health-behavior motivation; extending follow-up (adding waves) and applying growth-curve or discontinuous-change models around natural stressors (e.g., midterms/finals) would clarify durability and phase-specific effects. Finally, although the sensitivity analysis makes the detection threshold explicit, with N = 88 the design retains limited power for small higher-order (three-way) effects. Non-significant results are therefore inconclusive and should not be interpreted as evidence of absence or of effects undetected by this design. Future work can improve the detection of small interactions by increasing sample size, extending the observation window, strengthening manipulations, and minimizing measurement error; estimates near the detection boundary should be interpreted cautiously even when statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Plotnikoff, R. C. et al. Effectiveness of interventions targeting physical activity, nutrition and healthy weight for university and college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Activ. 12, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-015-0203-7 (2015).

Gillen, P. A., Sinclair, M., Kernohan, W. G., Begley, C. M. & Luyben, A. G. Interventions for prevention of bullying in the workplace. Cochrane Database Systemat. Rev., (1) (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009778.pub2

Vallerand, R. J. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in sport and physical activity: A review and a look at the future. Handbook of sport psychology, 59–83 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118270011

Emmons, R. A. Personal strivings: An approach to personality and subjective well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 51(5), 1058 (1986).

Keller, A. et al. Does the perception that stress affects health matter? The association with health and mortality. Health Psychol. 31(5), 677. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026743 (2012).

Zuzanek, J. Work, leisure, time-pressure and stress. In Work and leisure (pp. 123–144). Routledge (2004). https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880412331335902

Sheeran, P. et al. The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related Intentions and behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 35(11), 1178. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000387 (2016).

Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Human Decis. Process. 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T (1991).

Mead, M. P. & Irish, L. A. The theory of planned behaviour and sleep opportunity: An ecological momentary assessment. J. Sleep Res. 31(1), e13420. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13420 (2022).

Hagger, M. S. & Hamilton, K. Longitudinal tests of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 35(1), 198–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2023.2225897 (2024).

Bosnjak, M., Ajzen, I. & Schmidt, P. The theory of planned behavior: Selected recent advances and applications. Eur. J. Psychol. 16(3), 352–356. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v16i3.3107 (2020).

Kurzban, R., Duckworth, A., Kable, J. W. & Myers, J. An opportunity cost model of subjective effort and task performance. Behav. Brain Sci. 36(6), 661–679. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X12003196 (2013).

Mullainathan, S. & Shafir, E. Decision making and policy in contexts of poverty. Behav. Found. Pub. Policy 16, 281–300 (2013).

Rieskamp, J. & Hoffrage, U. Inferences under time pressure: How opportunity costs affect strategy selection. Acta Psychol. 127(2), 258–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2007.05.004 (2008).

Stults-Kolehmainen, M. A. & Sinha, R. The effects of stress on physical activity and exercise. Sports Med. 44(1), 81–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0090-5 (2014).

Sheeran, P. Intention—behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 12(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792772143000003 (2002).

Riediger, M. & Freund, A. M. Interference and facilitation among personal goals: Differential associations with subjective well-being and persistent goal pursuit. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 30(12), 1511–1523. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271184 (2004).

Fishbach, A., Friedman, R. S. & Kruglanski, A. W. Leading us not into temptation: Momentary allurements elicit overriding goal activation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 84(2), 296. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.296 (2003).

Wickens, C. D. Multiple resources and mental workload. Human Fact. 50(3), 449–455. https://doi.org/10.1518/001872008X288394 (2008).

Demanet, J., Verbruggen, F., Liefooghe, B. & Vandierendonck, A. Voluntary task switching under load: Contribution of top-down and bottom-up factors in goal-directed behavior. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 17(3), 387–393. https://doi.org/10.3758/PBR.17.3.387 (2010).

Little, C. The flipped classroom in further education: literature review and case study. Res. Post-compuls. Educ. 20(3), 265–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2015.1063260 (2015).

Kruglanski, A. W., Shah, J. Y., Pierro, A. & Mannetti, L. When similarity breeds content: need for closure and the allure of homogeneous and self-resembling groups. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 83(3), 648. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.3.648 (2002).

Boudreaux, M. J. & Ozer, D. J. Goal conflict, goal striving, and psychological well-being. Motiv. Emot. 37(3), 433–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-012-9333-2 (2013).