Abstract

Peatlands, ecosystems rich in organic matter, serve as substantial global carbon sinks and provide numerous ecosystem services. However, they face significant anthropogenic threats, including the construction and use of linear features such as roads, tracks, trails, and footpaths. This systematic review investigates the impacts of these linear features on temperate and boreal peatlands by analysing 81 primary research articles sourced from the Web of Science and Scopus databases, from an initial return of 831 articles. The findings reveal that 73 articles reported significant impacts, predominantly negative, on peatland features and processes in 5 broad categories: soil, vegetation, hydrology, wildlife, and fire dynamics. This includes soil compaction and erosion, plant community change through introduction of non-natives, altered preferential water flow, changes in predator-prey relationships and providing sources of ignition. Roads are the most studied linear feature, followed by tracks/trails and then footpaths, however linear feature type had no significant impact on the net direction of impact which was predominantly negative across feature type. This suggests that there may be a bias in research towards roads owing to their greater permanence and use, despite consistent negative impacts across feature types. Linear feature type also has no impact on the frequency of features/process impacted, which suggests that different types of linear feature impact broadly in similar ways, but it is the scale and severity of this impact that varies between feature types with different characteristics. Soil was negatively impacted significantly more than hydrology, wildlife and fire dynamics, but equal to vegetation, which was impacted significantly more than wildlife and fire dynamics. Impacts to soil and vegetation are easily observable at local and landscape scale, which again supports the premise that linear feature categories have similar impacts, but the scale and severity may vary. This work highlights that while substantial research has focused on the adverse effects of roads, there is a notable gap in understanding the specific impacts of other linear features, and future work should focus on evaluating impacts across linear feature categories and scales, to inform sustainable management practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally peatlands store 20% of all terrestrial carbon, over 30% of all soil carbon, despite covering only 2.8% of land surface1,2. Peatlands are habitats with soils containing significantly larger amounts of organic matter compared to conventional soils, up to 50% by weight3. This disparity is due to the accumulation of undecayed vegetation caused by typically waterlogged, anoxic conditions preventing microbial aerobic respiration and decay, forming peat4,5. In pristine conditions peatlands act as carbon syncs6, but when degraded peatlands can act as a carbon source7, significant in the era of anthropogenic climate change8.

Peatlands in temperate and boreal climatic zones face a number of anthropogenic threats, degrading habitat and leading to emission of the stored carbon. Large areas of lowland peatlands (e.g., in the UK) have previously been drained to produce highly productive agricultural land9. In upland peatlands, peat has been extracted for use as fuel or addition to compost for horticulture10, leading to the release of stored carbon and subsequent degradation of areas where extraction has occurred. Whilst in many areas of the world these practices have been phased out, contemporary threats include overgrazing from livestock11,12, petroleum/mining exploration and extraction13, logging activity14, windfarm construction15 and anthropogenic climate change16.

Not only are peatlands important carbon stores at the global scale, but they also provide a number of other ecosystem services at both global and local scales. Peat can be up to 90% water by mass17, which paired with the collection of rainwater, acts as a large natural reservoir, which can aid in the provision of drinking water18. Peatland plant biodiversity is characterised by specialised species adapted to thriving in a waterlogged, nutrient-poor environment, with particular abundance of bryophytes such as Sphagnum species when the peatland is in healthy condition19. Peatland bird assemblages are recognised as internationally important, with many species breeding on peatlands having conservation designations and legal protection20.

Along with water cycle regulation and habitat provision for diverse species, peatlands provide a number of direct services for human populations. For centuries, managed peatlands have been used for grouse shooting, which, despite requiring questionable management practices to facilitate such as rotational burning21 and culling of predators22,23, provides revenue to rural communities24. With the transition to renewable forms of energy, a number of onshore windfarm installations have been constructed across peatlands in Europe25,26, with particular prevalence on rare blanket bog habitats15. Peatlands are also important for people’s access and connection to nature, with a number of peatlands attracting large numbers of tourists such as the Peak District National Park, which saw 10.29 million visitors in 2019 many of whom utilised the 2459 km of footpaths, many of which cross the upland blanket bogs27. Human connection to nature is important for both physical and mental health, but also as a leverage point for promoting sustainability: fostering connections at specific places to aid in habitat conservation28.

Both industrial and recreational activities on peatlands require access by people and/or vehicles. This access requires the construction or formation of access infrastructure in the form of linear features to facilitate traversal, which similarly allow access through and around the peatland habitat for passing traffic. Linear features fragment landscapes29 to varying degrees and take many forms, but commonly for most human activities relating to peatlands these consist of anthropogenically formed features: roads, tracks, trails and footpaths. Roads referring to more permanently surfaced access routes utilised by vehicles, tracks/trails referring to lightly or temporarily used unsurfaced or temporarily surfaced routes utilised by vehicles, and footpaths referring to either surfaced or unsurfaced routes for use by foot.

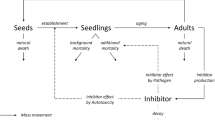

These features have been observed impacting several other landscape features or processes including wildlife, vegetation, soil and hydrology across a number of habitats. Threats to wildlife from linear features in peatlands include increased risk of vehicle collisions30 and habitat fragmentation which may restrict gene flow31. Vegetation is primarily affected across the width and at the edges of linear features, with vehicles or foot trampling as well as pollutants leading to vegetation degradation and potential community change32,33. Linear feature use, primarily those without permanent surfaces such as temporary track and footpaths, can cause high volumes of peat erosion, as well as causing high compaction of the soil that remains34,35,36. Soil modification impacts hydrology also, with compacted soil storing less water and increasing surface runoff water, which in turn furthers soil erosion37. Surfaced features such as roads can cause similar and more intense hydrological modifications38.

Estimates of coverage of linear features are difficult to produce owing to resources required to map features over such large areas. Where estimates have been made, coverage and therefore fragmentation have been extensive. In British uplands, 1.10 ± 0.15 km km− 2 of vehicular tracks were observed in a 5% total area sample39, while across the UK and EU, 235.4 km of linear features used to access wind turbine infrastructure in recognised blanket bogs was observed, with some densities exceeding 0.5 km km− 215. A recent report commissioned by Wicklow Upland Council assessed the state of an extensive network of 50 footpaths totalling 167 km of walking paths on peatland habitats in the Wicklow mountains34. The report identified over 3.2 km of pathways requiring major repair works due to the degradation of the footpath and surrounding area from tourism usage, which when combined with recommendations for minor repairs and intervention, would require at least 4000 days of labour to mitigate these impacts34.

Where there is a high population density, often much peatland nearby is degraded or lost10. With expanding populations, and increasing demands for resources and space, access to peatlands for industry, travel, and recreational use is likely to increase over the coming years. With this comes an increase in the development and use of linear features to facilitate this access. Extensive research needs to be conducted to investigate the impacts of these features on peatlands and their ecology, as these habitats will be ever more important both in climate change mitigation, but the wider ecosystem services they provide. Whilst research has been conducted already and specific components reviewed e.g., Williams-Mounsey et al. 202140, an extensive systematic review is required to examine this work at scale, to identify potentially key disciplines of research that have been overlooked and as well as geographic distribution of studies. Additionally, a review of this kind will allow analysis of peatland factors or processes most affected by linear features, and compare between different types of features. To this end, this review will systematically search primary, peer-reviewed journal articles that investigate the impacts of linear features and their use in temperate or boreal peatlands, extract data from these articles, and observe research trends and impacts to peatland habitats. This will highlight geographic gaps, identify research trends, and demonstrate knowledge gaps requiring future research. The focus here is on temperate and boreal peatlands, owing to 75% of the worlds peatlands being contained within northern high latitudes2, as well as the threats facing them from climate change and anthropogenic exploitation.

Results

Literature count and distribution

Following literature searches of both Web of Science and Scopus database using the PRISMA guidance outlined the methods section, a total of 1432 articles were returned, and with review articles (324) and duplicates (277) removed, this totalled 831 research articles (Fig. 1). Following sifting for article suitability, this resulted in the inclusion of 8113,15,31,32,38,39,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115 articles in the final review (Fig. 1). 59 of these articles focused solely on the impacts of roads, 14 solely on tracks/trails, 4 solely on footpaths and a final 4 that studied the impacts of various types of linear feature. Specific codings for each study can be seen in Supplementary A.

Publication dates span 1981–2023, with 2022 and 2023 being the years with the highest number of articles that were published (Fig. 2). Following log transformation of article count, there is a significant relationship between year of publication and number of articles published (F(1,27) = 33.44, R2 = 0.5367, P < 0.001) where more recent years are associated with a greater number of published articles (Number of articles = − 95.6181 + 0.0480 × Year). Where the intercept (β0) is −95.6181 (SE = 16.6756, t = − 5.734, p < 0.001) and the coefficient for Year (β1) is 0.0480 (SE = 0.0083, t = 5.782, p < 0.001), the exponential model for the impact of year on the number of articles researching linear features and temperate/boreal peatlands is:

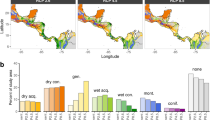

The country with the highest number of the published articles was Canada, with 30 of the 81 articles included in the final analysis investigating linear features over peatlands in Canada (Fig. 3). There is a significant difference in geographic location of the work conducted of the reviewed articles (χ2 = 128.44, df = 12, p < 0.01).

When the number of studies is considered in relation to the total peatland area per country (Fig. 4), Australia (7.41), the UK (6.84) and Norway (6.67) have the highest number of studies per 10,000 km2 of peatland area, where as Russia (0.034), Sweden (0.14) and the USA (0.19) have the lowest, with Canada (0.24) falling in the bottom 25%.

Linear feature impacts

A total of 73 of the articles had results with significant impacts on 1 or more landscape feature or process, 3 had results with no significant impacts, and 5 focused solely on the extent of linear features, not investigating any impact (Fig. 5a). Including only articles that investigated impacts from presence or use, linear features had a significant impact on temperate and boreal peatlands (χ2 = 64.474, df = 1, p < 0.01). 54 observed significant impacts of roads, 23 observed significant impacts of tracks/trails, and 7 observed significant impacts of footpaths (Fig. 5b). There was a significant difference in the number of studies of each linear feature type (χ2 = 74.574, df = 2, p < 0.01). Impacts of roads are investigated significantly more than tracks/trails and footpaths (p < 0.01, p < 0.01), with the impacts of tracks/trails investigated significantly more than footpaths (p = 0.014). 66 had net negative impacts, 4 had net positive impacts, and 3 had net neutral impacts (Fig. 5c), with a significant difference in the net direction of the impacts of linear features (positive, neutral, or negative) (χ2 = 189.93, df = 2, p < 0.01). The net direction of impact was predominantly negative (Fig. 5d), with significantly greater frequency of negative impacts compared to positive and neutral (p < 0.01, p < 0.01), and no significant difference in frequency between net positive and net neutral impacts (p = 1.00). Linear feature type had no significant effect on the impact direction (Fisher’s exact test for count data, p = 0.89).

(a) Number of articles that found significant or no significant impacts on temperate and boreal peatland features or processes from linear feature presence or use, with significant differences between categories marked by different number of ’*’. (b) Number of articles that investigated roads, tracks/trails or footpath extent or impacts on temperate and boreal peatlands, with significant differences between categories marked by different number of ’*’. (c) Net direction of impact for articles that found significant impacts from linear feature presence or use, either net negative, net positive or net neutral, with significant differences between categories marked by different number of ’*’. (d) Breakdown of net direction of impact for articles that found significant impacts by linear feature type.

5 broad categories of landscape features or processes were recording as having been impacted: vegetation, soil, hydrology, wildlife, and fire dynamics (Fig. 6a) across roads (Fig. 6b), tracks and trails (Fig. 6c), and footpaths (Fig. 6d). Many articles reported significant impacts on multiple features or processes, for a total of 115 observations, 108 of them negative (Fig. 6e). There was no significant effect of linear feature type on the type of landscape feature or processes impacted across articles (Fisher’s exact test for count data, p = 0.14). The frequency at which these features or processes were negatively impacted across all feature types significantly differed (χ2 = 74.13, df = 4, p < 0.01). Conducting pairwise fisher tests, soil and vegetation are similarly negatively impacted by linear features (p = 1.00). Soil is negatively impacted significantly greater than hydrology, wildlife and fire dynamics (p = 0.04, p < 0.01, p < 0.01). Vegetation is negatively impacted significantly greater than wildlife and fire dynamics (p < 0.01, p < 0.01) but not hydrology (p = 0.06). Hydrology is negatively impacted significantly greater than wildlife and fire dynamics (p < 0.01, p < 0.01), with wildlife and fire dynamics impacted equally (p = 1.00).

(a) Landscape features or processes impacted by all linear feature types, with the percent net direction of impact based on number of articles: net negative, net positive or net neutral for each feature or process. (b) Landscape features or processes impacted by roads, with the percent net direction of impact based on number of articles: net negative, net positive or net neutral for each feature or process. (c) Landscape features or processes impacted tracks/trails, with the percent net direction of impact based on number of articles: net negative, net positive or net neutral for each feature or process. (d) Landscape features or processes impacted by footpaths, with the percent net direction of impact based on number of articles: net negative, net positive or net neutral for each feature or process. (e) Peatland landscape features or processes negatively impacted by all linear feature types, with significant differences between features or processes marked by different numbers of ’*’.

Discussion

Trends in research

Resources have long been extracted from temperate and boreal peatlands, with peat harvesting and drainage for conversion to productive arable farmland common for centuries, and now petroleum extraction, animal grazing, logging, road construction, windfarms and recreational activity are commonplace across the range of these habitats15,116,117,118. This is despite peatland’s importance as a vast natural carbon store in the era of anthropogenic climate change. Exponentially increasing yearly publications on linear feature impact since 1981 reflects the increasing recognition of the importance of boreal and temperate peatlands (as carbon stores, in water management etc.) whilst also recognising the negative impacts that anthropogenic activity can have at a local and landscape scale. In terms of recognition in legislation, the 1970 s and 1980 s saw a number of environmental laws that recognised the importance of protecting nature, including peatlands, such as the Clean Water Act (USA 1972)119, Canada Wildlife Act (Canada 1973)120, Wildlife and Countryside Act (UK 1981)121. Following this a series of legislation with peatland specific interests increased protection such as the Wetlands Reserve Program (USA 1990)122, the Habitats Directive (EU 1992)123, the Ontario Wetland Evaluation System (Canada 2002)124, and the Peatland Code (UK 2015)125. This increase in protection of temperate and boreal peatlands likely led to an increase in research, to assess the impacts of different anthropogenic activities and infrastructure on the now-protected peatlands, including the linear features used to access them.

The significant difference observed in the number of studies per country can be attributed in part to the peatland land area and the intensity of their utilisation. By far the highest number of countries with studies investigating the impacts of linear features is Canada, followed by the UK and the USA. Canada accounts for approximately 42.5% of all the peatlands globally, around 1,235,000 km2126. Although large parts remain unutilised, large swathes act as petroleum extraction fields as well as logging areas, which all require construction of roads, tracks and trails to move equipment and extracted resources. Similarly in the USA, large parts of the total peatland area (625,000 km2)126, predominantly in Alaska, are utilised for petroleum extraction and logging, requiring similar infrastructure development. Despite the UK’s significantly lower total peatland area (19,000 km2)126 the significant density of linear features (up to 1.10 ± 0.15 km km− 2 density of vehicle tracks)39 can be attributed to the intense use of peatlands in terms of area for agriculture, traversal requirements and recreational use in particular. The Peak District National Park attracts up to 30 million visitors a year many of whom visit to hike on peat-covered upland plateaux127, and all requiring access infrastructure in the form of roads, tracks, trails and footpaths. Peatland in the Peak District National Park is some of the most degraded in the UK127,128. This suggests that countries and regions with large areas of peatland and/or high rates of utilisation (and therefore high density of linear features) have concerns about the impacts of linear features on peatlands, leading to research interest.

However, when the number of studies is normalised by peatland area, calculated as number of studies per 10,000 km2 of peatland area, a different pattern becomes evident. Countries with some of the largest total peatland areas, including Russia (1,420,000 km2), Canada (1,235,000 km2), and United States (625,000 km2) and Sweden (70,000 km2)126, have a low number of studies in relation to the size of their peatland coverage. This suggests that while these countries contribute a significant number of studies overall, research effort does not scale proportionally with land area, and substantial regions may remain underexamined. Conversely, several countries with comparatively smaller peatland areas, such as Australia (1350 km2), the United Kingdom (19,000 km2), France (2,000 km2), Ireland (12,000 km2), and Germany (16,250 km2)126, all have more than one study per 10,000 km2, indicating more intensive research effort. There are also notable gaps such as Belarus (29,390 km2), Denmark (10,000 km2), Estonia (11,000 km2), and the Falkland Islands (11,510 km2)126 each contain at least 10,000 km2 of peatland but had no eligible studies identified in this review. This highlights important absences in the global evidence base on linear feature impacts in peatlands. The specific ecological and management contexts of peatlands in these countries may not be represented elsewhere, and this highlights important absences in the global evidence base on linear feature impacts in peatlands. Low ratios in large peatland countries may be partly explained by the logistical difficulties of accessing remote and sparsely populated landscapes, or the sheer scale of ecosystems that makes comprehensive coverage challenging. In addition, limited research infrastructure, language barriers, and underfunding in some regions likely constrain local academic output or restrict international dissemination of findings. It is also possible that some relevant studies were not captured due to methodological limitations of the systematic review process.

Impact of different linear feature type

Despite a significantly greater focus on the impacts of roads on peatlands compared to tracks/trails and footpaths, and tracks/trails compared to footpaths, there is no significant difference in the net direction of impact between different types of feature. The majority of studies reported significant negative impacts across linear feature types. Although this suggests that linear feature presence and use has a predominantly negative impact on peatlands, this may be due to positive publication bias, leading to research being biased towards significant impacts129. In the case of linear features and peatlands, this bias would be towards publishing results that demonstrate negative impacts to peatlands, with results with no impact and net neutral (and to a lesser extent positive) remaining unpublished by the investigators. This publication bias can create a distorted view of the true effects of linear features on peatlands. As a result, the prevailing scientific narrative may overemphasise the negative impacts while underreporting instances where linear features have minimal or no detrimental effects. This discrepancy can influence conservation policies and management practices. Although the methodology used in this study conforms to PRISMA guidelines, restricting the likelihood for bias in selecting literature for inclusion, PRISMA does not prevent selecting from an already biased pool of literature, which may be being represented here. However, with different linear feature types having significant impact on a variety of habitats130,131,132 and the large amounts of negative impact studies selected for inclusion here, suggests that all type of linear feature impact temperate and boreal peatlands negatively.

The disparity between research focussed on roads, tracks/trails and footpaths despite all having significant negative impacts may be due to a research preference towards roads, owing to their greater permanence, ability to support higher volume of traffic, and use by large industry. Mapping and subsequent investigation of roads is simpler also compared to many tracks/trails and footpath, as they may be ephemeral in nature and difficult to study. For example, logging trails may only be used for a single season while that specific area of forest is logged, before falling into disuse as activity moves to new areas80. The results presented here, however, suggest that any sort of access structure will negatively impact peatlands regardless of its type or use. We have not considered the spread or severity of this impact. Roads may have a more severe and widespread impact due to their spread, maintenance, and continuous use while tracks, trails and footpaths might cause more localised damage, as demonstrated in mountainous tundra133. Despite these variations, the results presented here suggest that any sort of linear feature access structure will negatively impact peatlands regardless of its type or use, and so a larger focus is needed on the impacts of track/trials and footpaths to better understand their impacts.

Soil, vegetation, hydrology, wildlife and fire dynamics were the broad categories all negatively impacted by linear features. Linear features can lead to soil compaction, erosion, and loss of organic matter68,72,81. Compaction reduces the ability of soil to absorb water, increasing runoff and erosion. Erosion can strip the soil of nutrients and reduce its fertility, and lead to structural degradation and loss of stored carbon54. Vegetation is directly affected through changes in microclimate and soil conditions as well as direct damage caused by traversing vehicles or people32,98. Disturbed areas may be colonised by invasive species, which can outcompete native plants53. Additionally, fragmented habitats make it difficult for plant species to disperse104. The hydrological impacts of linear features include alterations in surface and groundwater flow patterns. Roads can change the natural flow of water, leading to increased runoff, altered stream channels, and reduced groundwater recharge38,61,96. These changes can cause flooding in some areas and drought in others57,105. Wildlife in peatlands is affected both directly and indirectly by linear features, including habitat loss and change89, increased mortality due to collisions with vehicles134, and alteration of predator-prey dynamics84. Linear features can act as firebreaks135, altering the natural spread of wildfires. Conversely, they can also facilitate the spread of fires by providing access to ignition sources such as vehicles and machinery107.

The results if this review demonstrate soil and vegetation are reported to be impacted negatively the most, significantly more than all other features or processes for soil, and wildlife and fire processes for vegetation. This is likely due to observations of degradation being easily possible at localised and landscape scales. Peat erosion can be localised to the edge of the linear feature, such as erosion caused by footpath use which spreads as the path widens. Conversely, it can be in the form of large peat gullies that spread across the landscape, formed initially from localised compaction, erosion, and vibrations from vehicles136. This type of degradation can be fast and is easily observed, whereas changes in hydrology may be more difficult to observe, as changes can be subtle and gradual, often requiring detailed and long-term studies to quantify their impacts. Similarly for the significantly lower observations of negative impacts on wildlife, the effects of habitat fragmentation and changes in predator-prey dynamics might require long-term studies to fully understand137. Additionally, wildlife responses can be highly variable depending on species, season, and habitat type, making consistent observations challenging137. In the case of fire dynamics, the impact of linear features might be less immediately apparent because fire regimes are influenced by a combination of factors including weather, fuel availability, and landscape configuration138.

What is particularly interesting from the results of this work is that despite the significantly different reported incidents of feature/process type impacted, the type of linear feature did not affect this. This consistency in what is impacted between roads, tracks/trails and footpath suggests that different linear feature types may impact temperate and boreal peatlands in similar ways, but the scale or severity of this impact may vary depending on the specific characteristics such as use, width, construction materials, traffic intensity, and maintenance practices associated with each type of linear feature. Consequently, the cumulative effects on peatlands may be more pronounced along major transportation corridors. Understanding that all linear features may detrimentally impact peatlands but at varied scales suggests a need for comprehensive management strategies. Conservation efforts could prioritise minimising new linear infrastructure in sensitive peatland areas, implementing sustainable design and construction practices such as raised boardwalks, and regularly monitoring and mitigating impacts of existing linear features. Additionally, adaptive management approaches that consider the specific characteristics and context of each linear feature type could help mitigate and minimize environmental degradation in peatland landscapes, with a broad consideration of the wider impacts of fragmentation at the local and landscape scales caused by linear feature networks. Future research should build towards this, comparing between linear features of the same and different types with varied characteristics, considering impacts across scale. Future data led research should focus on consideration of linear feature effect size, using a meta-analysis methodology.

When considered alongside the wider research and conservation agendas such as the UNEP Global Peatlands Assessment (2022)139, these findings presented here reinforce the broader picture that infrastructure development, including linear features, is a key driver of peatland degradation worldwide, but despite a growing research agenda, significant gaps still exist. The significant increase in research publications over recent decades reflects growing awareness the ecological importance of peatlands, and the detrimental effects of anthropogenic activities, with a large proportion of research conducted in Canada which contains vast swathes of the world’s peatlands. However, when considered per area of peatland, large peatland area containing countries such as Canada have a relative low research effort, and along with geographic gaps in the literature, highlight the need for further work across all geographic regions. The findings indicate that all types of linear features negatively impact peatlands, with soil and vegetation being the most affected components. Roads, as the most studied linear feature, often lead to soil compaction, altered hydrology, and disrupted vegetation patterns. Despite the greater focus on roads, there is a clear necessity for future research to address gaps in knowledge, particularly concerning the impacts of tracks, trails, and footpaths. This work highlights the consistency in negative impact to peatlands across linear feature type, and the similarity in landscape factors/processes impacted also, and that type of impact is generally consistent. The UNEP report emphasises that such features not only cause direct physical and hydrological disturbance, but also fragment habitats, which while reflected on in this review, was not an explicit category, making it a key research area for future work. This review emphasises the importance of continued research on linear feature impacts across types and scales in temperate and boreal peatlands to inform sustainable management practices.

Methods

Literature search process

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)140 was used to establish a systematic literature review (SLR) of research and research trends investigating the impacts of linear feature presence and use on temperate and boreal peatlands. The Web of Science and Scopus databases were chosen for the literature search component of this study, and the PRISMA procedure was applied: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion. The PRISMA approach benefits an SLR study because it utilises systematic steps to achieve the objective of the study. Moreover, there are few systematic literature reviews investigating this issue, demonstrating the need for a comprehensive study of the existing body of work.

Identification and screening

Articles focused on linear feature impact and use (post construction) on peatlands were sourced and identified via the Web of Science and Scopus databases. For the purposes of this study, articles that focused on investigations of the impacts of linear feature presence and/or linear feature use on temperate and/or boreal peatlands were qualified for inclusion. The linear features of interest were those classified as transport routes through, around or over peatlands: roads, track/trails, or footpaths. To this end, the search terms used to identify studies from the Web of Science database were “(Peatland OR peat) AND (tracks OR trails OR footpaths OR roads) NOT tropical”. Similarly, the search terms used to identify studies from the Scopus database were “(Peatland OR peat) AND (tracks OR trails OR footpaths OR roads) AND NOT tropical”. Searches were conducted on 03/08/2023 and 08/08/2023 respectively. No year restrictions were placed on the search criteria, although the authors recognise bias in databases towards recent publications owing to non-digitisation or poor records of older articles.

Only primary research articles were targeted for inclusion in the synthesis of this review, in order to avoid potential bias in any existing reviews. Grey literature such as studies conducted as part of tenders for local/national government assessments of linear feature condition (e.g. York 202228) were also not included. This is because part of the focus of this review is the trends in research, and so government-funded reports that may be produced to meet policy requirements are not suitable for inclusion. Any review articles returned from searches of either database were removed from the combined article list, as were duplicates of the articles returned in both databases.

Eligibility and inclusion

Articles were deemed suitable for inclusion in the final synthesis if the context of the study was investigating the potential impacts or the extent of linear feature presence or impacts on temperate or boreal peatlands. Articles focusing on peatlands that occur outside these climatic zones were not eligible. Articles focused on linear features that the authors categorised as roads, tracks, trails and footpaths were the only features eligible for conclusion. Articles where only the potential linear feature impacts to peatland features or processes were as a result of the construction process, rather than as a result of completed feature presence or use were also not eligible for inclusion. Articles that specifically investigated impacts of different vehicle types in a controlled setting, or the development of new technologies for peatland traversal were likewise not eligible for inclusion.

Literature storage and coding

All collected literature was exported from the Web of Science and Scopus databases as Microsoft Excel files, and subsequently combined and managed in the same software. Articles were colour coded based on suitability and transferred to a separate data sheet that combined articles sourced from both the Web of Science and Scopus databases, with duplicates removed using the “remove duplicates function”. Alongside article reference data, articles were coded based on the: article study location, linear feature type (road, track/trail, footpath, various), significant impact or extent (yes, no, extent), net direction of significant impact (negative, positive, neutral) and peatland feature or process impacted.

For linear feature type, tracks and trails were merged into a single category as they share many of the same physical characteristics and uses. Articles with various types of linear feature although initially coded as various, each feature type results separated out and coded. Significant impact (yes or no) was determined if the article stated results that significantly impacted a peatland feature or characteristic, which was also then recorded. The net direction of this impact was determined to be negative, positive or neutral based on the interpretation of the results by the article authors and wider implications of the impacts. For articles with multiple impacts, the net direction is a combination of all impact directions. Neutral is where there were no obvious wider positive or negative implications from article results, or negative and positive results are broadly balanced.

Map production.

Global maps were produced to visualise the geographic distribution of relevant studies in RStudio (R version 4.3.1) using the R programming language, employing the ggplot2 and maps packages. Choropleth maps were produced with a continuous colour gradient to indicate both the study density of country-level counts of relevant publications, and the number of studies per 10,000 km2 of peatland, allowing for comparison between countries with differing peatland extents. Peatland area data were obtained from Joosten 2003126.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was conducted in RStudio (R version 4.3.1) using the R programming language. Spearman’s rank correlation was performed for number of articles published and year. To analyse the relationship between time (Year) and publications (Count), a log-linear regression approach was utilised. Given that the initial inspection of the data suggested an exponential growth pattern, a natural logarithm transformation was applied to the article count, to linearise the exponential trend. Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was fitted to the transformed data (log(Count) ~ Year), where year serves as the independent variable and the log-transformed count as the dependent variable. Model assumptions, including normality of residuals, homoscedasticity, and linearity, were assessed through graphs, model coefficients and t tests. Output log linear regression equation (y = β0 + β1 × X + ϵ) was reinterpreted in exponential form (y = e(β0 + β1 × X)) to fit the data distribution, and plotted.

Chi-squared distribution tests were performed for: study country distribution; linear feature significant impact (yes, no, extent); net direction of impact (negative, positive, neutral), number of articles for each linear feature type; frequency of peatland factors or feature impacted. For tests where some categories had expected values below the minimum threshold, Fisher’s exact test for count data was used. These fisher tests included linear feature type on frequency of peatland factors or feature impacted; linear feature type impact on not direction of impact. Where significant differences were found, pairwise fishers tests with Bonferroni corrections producing adjusted p-value were conducted to determine differences between each category.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Limpens, J. et al. Schaepman-Strub. Peatlands and the carbon cycle: from local processes to global implications – a synthesis. Biogeosciences 5, 1475–1491 (2008).

Xu, J., Morris, P. J., Liu, J., Holden, J. & Peatmap Refining estimates of global peatland distribution based on a meta-analysis. Catena 160, 134–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2017.09.010 (2018).

Kechavarzi, C., Dawson, Q., Bartlett, M. & Leeds-Harrison, P. B. The role of soil moisture, temperature and nutrient amendment on CO2 efflux from agricultural peat soil microcosms. Geoderma 154, 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2009.02.018 (2010).

Hopple, A. M. et al. S.D. Does dissolved organic matter or solid peat fuel anaerobic respiration in peatlands? Geoderma 349, 79–87 (2019).

Bridgham, S. D., Megonigal, J. P., Keller, J. K., Bliss, N. B. & Trettin, C. The carbon balance of North American wetlands. Wetlands 26 (4), 889–916 (2006).

Nugent, K. A., Strachan, I. B., Strack, M., Roulet, N. T. & Rochefort, L. Multi-year net ecosystem carbon balance of a restored peatland reveals a return to carbon sink. Glob Chang. Biol. 24, 5751–5768. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14449 (2018).

Joosten, H. Multi-year Net Ecosystem Carbon Balance of a Restored Peatland Reveals a Return To Carbon Sink’ (Wetlands international., 2009).

Allan, R. P. et al. In Climate Change 2021: the Physical Science basis. Contribution of Working Group I To the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 3–32 (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

Dawson, Q., Kechavarzi, C., Leeds-Harrison, P. B. & Burton, R. G. O. Subsidence and degradation of agricultural peatlands in the Fenlands of Norfolk, UK. Geoderma 154 (3-4), 181–187 (2010).

Joosten, H. Peatland Restoration and Ecosystem Services: science, policy, and Practice (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Haigh, M. Environmental Change in Headwater Peat Wetlands, UK Vol. 63 (Springer, 2006).

Bardgett, R. D., Marsden, J. H. & Howard, D. C. The extent and condition of Heather on moorland in the uplands of England and Wales. Biol. Conserv. 71, 155–161 (1995).

Wood, M. M., Strack, M. L., Price, M., Osko, J. S. & Petrone, T. J. Spatial variation in nutrient dynamics among five different peatland types in the Alberta oil sands region. Ecohydrology 9 (4), 688–699 (2015).

Locky, D. A. & Bayley, S. E. Effects of logging in the Southern boreal peatlands of Manitoba, Canada. Can. J. For. Res. 37, 3. https://doi.org/10.1139/X06-249 (2007).

Chico, G. et al. The extent of windfarm infrastructures on recognised European blanket bogs. Sci. Rep. 13, 3919. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30752-3 (2023).

Antala, M., van der Juszczak, R. & Rastogi, A. Impact of climate change-induced alterations in peatland vegetation phenology and composition on carbon balance. Sci. Total Environ. 827, 154294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154294 (2022).

Hobbs, N. B. Mire morphology and the properties and behavior of some British and foreign peats. Q. J. Eng. Geol. 19, 7–80 (1986).

Ferreto, A. B., Matthews, R. & Smith, R. Climate change and drinking water from Scottish peatlands: where increasing DOC is an issue? J. Environ. Manage. 300, 113688 (2021).

Littlewood, N. et al. Peatland Biodiversity (IUCN UK Peatland Programme, 2010).

Stroud, D. A., Reed, T. M., Pienkowski, M. W., Lindsay, R. A. & Birds Bogs and Forestry. The Peatlands of Caithness and Sutherland (Nature Conservancy Council, 1987).

Ramchunder, S. J., Brown, L. E. & Holden, J. Rotational vegetation burning effects on peatland stream ecosystems. J. Appl. Ecol. 50, 636–648. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12082 (2013).

Thompson, P. S., Amar, A., Hoccom, D. G., Knott, J. & Wilson, J. D. Resolving the conflict between driven-grouse shooting and conservation of Hen harriers. J. Appl. Ecol. 46, 950–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01687.x (2009).

Ewing, S. R. et al. Illegal killing associated with Gamebird management accounts for up to three-quarters of annual mortality in Hen harriers circus cyaneus. Biol. Conserv. 283, 110072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2023.110072 (2023).

Robertson, G. S., Newborn, D., Richardson, M. & Baines, D. Does rotational heather burning increase red grouse abundance and breeding success on moors in northern England? Wildlife Biology 2017(wlb.00227), 1–10 (2017).

Bright, J. A. et al. Spatial overlap of wind farms on peatland with sensitive areas for birds. Mires Peat. 4, 07 (2008).

Renou-Wilson, F. & Farrell, C. A. Peatland vulnerability to energy-related developments from climate change policy in ireland: the case of wind farms. Mires Peat. 4, 08 (2009).

Park, P. D. N. State of the Park. (2021).

Beery, T. et al. Disconnection from nature: expanding our Understanding of human–nature relations. People Nat. 5, 470–488 (2023).

Keller, I. & Largiader, C. R. Recent habitat fragmentation caused by majorroads leads to reduction of gene flow and lossof genetic variability in ground beetles. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 240, 417–423 (2003).

Kirkland, H. et al. Successful deer management in Scotland requires less conflict not more. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2 https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2021.770303 (2021).

Dyer, S. O. N., Wasel, J. P. & Boutin, S. M. Avoidance of industrial development by woodland caribou. J. Wildl. Manage. 65 (3), 531–542 (2001).

Arnesen, T. Vegetation dynamics following trampling in rich Fen at Solendet, central Norway; a 15 year study of recovery. Nord. J. Bot. 19, 257–384 (1999).

Angold, P. G. The impact of a road upon adjacent heathland vegetation: effects on plant species composition. J. Appl. Ecol. 34, 409–417 (1997).

York, C. Wicklow Mountains Path Survey (Wicklow Uplands Council & Walking the Talk, 2022).

Alakukku, L. Persistence of soil compaction due to high axle load traffic. I. Short-term effects on the properties of clay and organic soils. Soil and Tillage Research 37, 211–222 (Persistence of soil compaction due to high axle load traffic. I. Short-term effects on the properties of clay and organic soils.).

Alakukku, L. Persistence of soil compaction due to high axle load traffic. II. Short-term effects on the properties of clay and organic soils. Soil and Tillage Research 37, 211–222 (Persistence of soil compaction due to high axle load traffic. I. Short-term effects on the properties of clay and organic soils.).

Fullen, M. A. Compaction, hydrological processes and soil erosion on loamy sands in East Shropshire, England. Soil Tillage. Res. 6, 17–29 (1985).

Plach, J. W., Macrae, M. E., Osko, M. L. & Petrone, T. J. Effect of a semi-permanent road on N, P, and CO2 dynamics in a poor Fen on the Western boreal Plain, Canada. Ecohydrology 10 (7), e1874 (2017).

Clutterbuck, B., Burton, W., Smith, C. & Yarnell, R. W. Vehicular tracks and the influence of land use and habitat protection in the British uplands. Sci. Total Environ. 737, 140243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140243 (2020).

Williams-Mounsey, J., Grayson, R., Crowle, A. & Holden, J. A review of the effects of vehicular access roads on peatland ecohydrological processes. Earth Sci. Rev. 214 (7), 103528 (2021).

Arp, C. D. & Simmons, T. Analyzing the impacts of off-road vehicle (ORV) trails on watershed processes in Wrangell-St. Elias National park and Preserve, Alaska. Environ. Manage. 49, 751–766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-012-9811-z (2012).

Bacon, J. R. Isotopic characterisation of lead deposited 1989–2001 at two upland Scottish locations. J. Environ. Monit. 4, 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1039/b109731h (2002).

Brumbaugh, W. G., Morman, S. A. & May, T. W. Concentrations and bioaccessibility of metals in vegetation and dust near a mining haul road, cape Krusenstern National Monument, Alaska. Environ. Monit. Assess. 182, 325–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-011-1879-z (2011).

Diaz-de-Quijano, M. et al. Modelling and mapping trace element accumulation in sphagnum peatlands at the European scale using a geomatic model of pollutant emissions dispersion. Environ. Pollut. 214, 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2016.03.036 (2016).

Dykes, A. P. Landslide investigations during pandemic restrictions: initial assessment of recent peat landslides in Ireland. Landslides 19, 515–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-021-01797-0 (2022).

Mäyrä, J., Kivinen, S., Keski-Saari, S., Poikolainen, L. & Kumpula, T. Utilizing historical maps in identification of long-term land use and land cover changes. Ambio 52, 1777–1792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-023-01838-z (2023).

Rauch, S., Hemond, H. F. & Peucker-Ehrenbrink, B. Source characterisation of atmospheric platinum group element deposition into an ombrotrophic peat bog. J. Environ. Monit. 6, 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1039/b316547g (2004).

Rhodes, A. L. & Guswa, A. J. Storage and release of road-salt contamination from a calcareous lake-basin fen, Western Massachusetts, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 545–546, 525–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.12.060 (2016).

Robroek, B. J., Smart, R. P. & Holden, J. Sensitivity of blanket peat vegetation and hydrochemistry to local disturbances. Sci. Total Environ. 408, 5028–5034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.07.027 (2010).

Saraswati, S., Parsons, C. T. & Strack, M. Access roads impact enzyme activities in boreal forested peatlands. Sci. Total Environ. 651, 1405–1415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.280 (2019).

Strack, M. et al. Petroleum exploration increases methane emissions from Northern peatlands. Nat. Commun. 10, 2804. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10762-4 (2019).

Strack, M., Softa, D., Bird, M. & Xu, B. Impact of winter roads on boreal peatland carbon exchange. Glob Chang. Biol. 24, e201–e212. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13844 (2018).

Williams-Mounsey, J., Crowle, A., Grayson, R. & Holden, J. Removal of mesh track on an upland blanket peatland leads to changes in vegetation composition and structure. J. Environ. Manage. 339, 117935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117935 (2023).

Williams-Mounsey, J., Crowle, A., Grayson, R., Lindsay, R. & Holden, J. Surface structure on abandoned upland blanket peatland tracks. J. Environ. Manage. 325, 116561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116561 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Impact of the 2016 fort McMurray wildfires on atmospheric deposition of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and trace elements to surrounding ombrotrophic bogs. Environ. Int. 158, 106910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106910 (2022).

Aubert, D. L. R. et al. Origin and fluxes of atmospheric REE entering an ombrotrophic peat bog in black forest (SW Germany): evidence from snow, lichens and mosses. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 70, 2815–2826 (2006).

Bocking, E. C. & Price, D. J. Using tree ring analysis to determine impacts of a road on a boreal peatland. For. Ecol. Manag. 404, 24–30 (2017).

Cameron, E. L. Persistent changes to ecosystems following winter road construction and abandonment in an area of discontinuous permafrost, Nahanni National park Reserve, Northwest Territories, Canada. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 49, 259–276 (2018).

Campbell, D. B. Natural revegetation of winter roads on peat lands in the Hudson Bay Lowland, Canada. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 44, 155–163 (2012).

Carpenter, T. M., Bayne, C. L., Keim, E. & Nielsen, J. L. Influence of in situ oilsands development on occurrence of an avian peatland generalist and specialist. Avian Conserv. Ecol. 17 (2), 23 (2022).

Chimner, R. L. & Cooper, J. M. Mountain Fen Distribution, types and restoration Priorities, San Juan mountains. Colo. USA Wetlands. 30, 763–771 (2010).

Comte, S. T. et al. Seasonal and daily activity of non-native Sambar deer in and around high-elevation peatlands, south-eastern Australia. Wildl. Res. 49 (7), 659–672 (2022).

Cruickshank, M. T., Bond, D. R. W., Devine, P. M. & Edwards, C. J. W. Peat extraction, conservation and the rural economy in Northern-Ireland. Appl. Geogr. 15 (4), 365–383 (1985).

D’Angelo, B. L. et al. Carbon balance and Spatial variability of CO2 and CH4 fluxes in a Sphagnum-Dominated peatland in a temperate climate. Wetlands 41, 5 (2021).

DeMars, C. A. & Boutin, A. Nowhere to hide: effects of linear features on predator–prey dynamics in a large mammal system. J. Anim. Ecol. 87 (1), 274–284 (2017).

Elmes, M. K. et al. Evaluating the hydrological response of a boreal Fen following the removal of a temporary access road. J. Hydrol. 594, 125928 (2021).

Elmes, M. P., Volik, R. M. & Price, O. Changes to the hydrology of a boreal Fen following the placement of an access road and below ground pipeline. J. Hydrology-Regional Stud. 40, 101031 (2022).

Ewald, J. E. Forest vegetation of Sassau in lake Walchensee (Bavaria): comparison of natural and managed forest, Island and penninsula. Tuexenia 35, 131–153 (2015).

Farrell, C. C. et al. Developing peatland ecosystem accounts to guide targets for restoration. One Ecosyst. 6, e76838 (2021).

Fenton, N. B. Sphagnum community change after partial harvest in of black Spruce boreal forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 242 (1), 24–33 (2007).

Grieve, I. D. & Gordon, D. A. Nature, extent and severity of soil-erosion in upland Scotland. Land Degrad. Rehabil. 6, 41–55 (1995).

Harrison, A. H. & Entwisle, M. Increasing road network resilience to the impacts of ground movement due to climate change: a case study from Lincolnshire, UK. Q. J. Eng. Geol.Hydrogeol. 56 (3), qjegh2023–qjegh2002 (2023).

Holynska, B. O., Samek, J., Streli, L., Wachniew, C. & Wobrauschek, P. Time dependence characterization of Pb and Br concentrations in samples from ombrotrophic peat bogs in Austria and Poland by energy-dispersive x-ray fluorescence spectrometry. X-Ray Spectrom. 31, 12–15 (2002).

Huntley, M. M. & Shotyk, R. W. High-resolution palynology, climate change and human impact on a late holocene peat bog on Haida Gwaii, British Columbia, Canada. Holocene 23 (11), 1572–1583 (2013).

Johansen, M. A., Klanderud, P., Olsen, K. & Skrindo, S. L. Restoration of peatland by spontaneous revegetation after road construction. Appl. Veg. Sci. 20 (4), 631–640 (2017).

Johnstone, R. D., Slattery, M. E. & Fedy, S. M. Multi-level habitat selection of boreal breeding mallards. J. Wildl. Manage. 87 (5), e22403 (2023).

Korkiakoski, M. O. et al. Impact of partial harvest on CH4 and N2O balances of a drained boreal peatland forest. Agric. For. Meteorol. 265, 108168 (2020).

Lanvers, J. S. & Fartmann, B. Impacts of cross-country ski trails on bog and Fen vegetation. Tuexenia 32 (1), 87–103 (2012).

Lepilin, D. L. et al. Response of vegetation and soil biological properties to soil deformation in logging trails of drained boreal peatland forests. Can. J. For. Res. 52, 4 (2022).

Lepilin, D. L., Uusitalo, A. & Tuittila, J. Soil deformation and its recovery in logging trails of drained boreal peatlands. Can. J. For. Res. 49, 7 (2019).

McHugh, M. Short-term changes in upland soil erosion in England and wales: 1999 to 2002. Geomorphology 86 (1–2), 204–213 (2007).

Miller, C. B. & Turetsky, B. W. The effect of long-term drying associated with experimental drainage and road construction on vegetation composition and productivity in boreal Fens. Wetlands Ecol. Manage. 23, 845–854 (2015).

Morozova, A. N. & Kuklina, K. E. Taiga landscape degradation evidenced by Indigenous observations and remote sensing. Sustainability 15 (3), 1751 (2023).

Mumma, M.A., Gillingham, M.P., Johnson, C.J. & Parker, K. Functional responses to anthropogenic linear features in a complex predator-multi-prey system. Landscape Ecol. 34, 2575–2597 (2019).

Nichol, D. Environmental changes within kettle holes at Borras bog triggered by construction of the A5156 Llanypwll link Road, North Wales. Eng. Geol. 59 (1–2), 73–82 (2001).

Opekunova, M. O., Kukushkin, A. Y., Lisenkov, S. Y., Vlasov, S. A. & Somov, S. V. Soil pollution with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and petroleum hydrocarbons in the North of Western siberia: Spatial pattern and ecological risk assessment. Eurasian Soil. Sci. 55, 1647–1664 (2022).

Panno, S.V., Nuzzo, V.A., Cartwright, K. et al. Impact of urban development on the chemical composition of ground water in a fen-wetland complex. Wetlands 19, 236–245 (1999).

Patterson, L. C. The use of hydrologic and ecological indicators for the restoration of drainage ditches and water diversions in a mountain fen, cascade range. Calif. Wetlands. 27, 290–304 (2007).

Pearce-Higgins, J. Y. Habitat selection, diet, arthropod availability and growth of a moorland wader: the ecology of European golden plover pluvialis apricaria chicks. Ibis 146 (2), 335–346 (2004).

Pugh, A. N. et al. Interactions between peat and salt-contaminated runoff in Alton Bog, Maine, USA. J. Hydrol. 182 (1–4), 83–104 (1996).

Racine, C. W. & Jorgenson, J. C. Airboat use and disturbance of floating mat Fen wetlands in interior Alaska, USA. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 51 (4), 371–377 (1998).

Y. T., M. S. S. B. & A. J. Roads impact tree and shrub productivity in adjacent boreal peatlands. Forests 11 (5), 594 (2020).

Saraswati, S., Bhusal, Y., Trant, A. J., & Strack, M. Presence of access roads results in reduced growing season carbon uptake in adjacent boreal peatlands. J. Geophys. Research: Biogeosciences. 128 (1), E2022jg007206 (2023).

Saraswati, S. P., Rahman, R. M., McDermid, M. M., Xu, G. J. & Strack, B. Hydrological effects of resource-access road crossings on boreal forested peatlands. J. Hydrol. 584, 124748 (2020).

Saraswati, S. S. Road crossings increase methane emissions from adjacent peatland. J. Geophys. Research-Biogeosciences. 124 (11), 3588–3599 (2019).

Schauffler, M. J., Pugh, G. L. & Norton, A. L. Influence of vegetational structure on capture of salt and nutrient aerosols in a Maine peatland. Ecol. Appl. 6 (1), 263–268 (1996).

Selyanina, S. T., Zubov, V. G., Kutakova, I. N. & Ponomareva, N. A. Pigment composition of sphagnum fuscum of wetlands under anthropogenic impact. Lesnoy Zhurnal-Forestry J. https://doi.org/10.37482/0536-1036-2020-6-120-131 (2020).

Taylor, B. R. Correlation between Atv tracks and density of a rare plant (drosera filiformis) in a Nova Scotia bog. Rhodora 115 (962), 158–169 (2013).

Tremblauy-Auger, F. L., Leroueil, A., Demers, S. & Levasseur, D. A rare case of downward progressive failure in Eastern canada: the 1976 Saint-Fabien landslide. Can. Geotech. J. 59, 9 (2022).

Turunen, J. Development of Finnish peatland area and carbon storage 1950–2000. Boreal Environ. Res. 13, 319–334 (2008).

n der Linden, M. G. & va Late holocene climate change and human impact recorded in a South Swedish ombrotrophic peat bog. Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecology. 240 (3–4), 649–667 (2006).

Van Seters, T. P. The impact of peat harvesting and natural regeneration on the water balance of an abandoned cutover bog, Quebec. Hydrol. Process. 15, 233–248 (2001).

Vandermolen, P. S. & SMIT, M. R. Vegetation and ecology of hummock-hollow complexes on an irish raised bog. Biology and Environment-Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 94(2), 145–175 (1994).

Vermaat, J. G. & Omtzigt, H. Do biodiversity patterns in Dutch wetland complexes relate to variation in urbanisation, intensity of agricultural land use or fragmentation? Biodivers. Conserv. 16, 3585–3595 (2006).

von Sengbusch, P. Enhanced sensitivity of a mountain bog to climate change as a delayed effect of road construction. Mires Peat. 15 (6), 1–18 (2015).

van der Molen, P. C., Schalkoort, M., & Smit, R. The role of sphagnum fimbriatum in secondary succession in a road salt impacted bog. Can. J. Bot. 65, 2270–2275 (1987).

Wilkinson, S. F., Wotton, A. K. & Waddington, B. M. Mapping smouldering fire potential in boreal peatlands and assessing interactions with the wildland-human interface in Alberta, Canada. Int. J. Wildland Fire. 30 (7), 552–563 (2021).

Williams, T. Q. & Baltzer, W. L. Linear disturbances on discontinuous permafrost: implications for thaw-induced changes to land cover and drainage patterns. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 025006 (2013).

Willier, C. D., Devito, J. M., Bater, K. J. & Nielsen, C. W. The extent and magnitude of edge effects on Woody vegetation in road-bisected treed peatlands in boreal Alberta, Canada. Ecohydrology 15 (7), e2455 (2022).

Wood, M. C. & Moffat, P. A. AJ. Reduced ground disturbance during mechanized forest harvesting on sensitive forest soils in the UK. Forestry. 76 (3), 345–361 (2003).

Campbell, D. C. Can mulch and fertilizer alone rehabilitate surface-disturbed Subarctic peatlands? Ecol. Restor. 32 (2), 153–160 (2014).

Pickett, A. Cadmium dispersal on a Raised heathland in the peak district National park adjacent to a major trunk road. Bioscience Horizons. 4 (2), 149–157 (2011).

Kaverin, D. A. P. & Novakovsky, A. V. The impact of transformation in vegetation and soil cover on the soil temperature regime under winter road operation in Bolshezemelskaya tundra. Earth’s Cryosphere. 23 (1), 16–25 (2019).

Kaverin, D. A., K., A. V. & Pastukhov, A. V. Application of high-frequency ground penetrating radar to investigations of permafrost-affected soils of peat plateaus (European Northeast of Russia). Earth’s Cryosphere. 22 (4), 86–95 (2018).

Zacheis, A. D. Resistance and resilience of floating mat Fens in interior Alaska following airboat disturbance. Wetlands 29, 236–247 (2009).

Richardson, C. J. & Pocosins An ecological perspective. Wetlands 11, 335–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03160755 (1991).

Foote, L. & Krogman, N. Wetlands in canada’s Western boreal forest: agents of change. Forestry Chron. 82, 825–833. https://doi.org/10.5558/tfc82825-6 (2006).

Chimner, R. A., Cooper, D. J., Wurster, F. C. & Rochefort, L. An overview of peatland restoration in North america: where are we after 25 years? Restor. Ecol. 25, 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.12434 (2017).

United States Congress. Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972 (Clean Water Act), Pub. L. No. 92–500, 86 Stat. 816. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/statute-86/pdf/statute-86-Pg816.pdf (1972).

Government of Canada. Canada Wildlife & Act, R. S. C. c. W-9 (originally enacted 1973). Available at: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/w-9/ (1985).

Parliament of the United Kingdom & Wildlife, C. A. c. 69. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1981/69 (1981).

United States Department of Agriculture. Wetlands reserve Program, Food, Agriculture, Conservation, and trade act of 1990. Pub L No. 101–624, 104 Stat. 3359.

Council of the European Communities. Council Directive 92/43/EEC on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora (Habitats Directive). Off. J. Eur. Communities L206, 7–50. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A31992L0043 (1992).

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Ontario Wetland Evaluation System: Southern Manual. Later edition. Available at: https://www.ontario.ca/files/2023-02/mnrf-pd-rpdpb-ontario-wetlands-evaluation-system-southern-manual-2022-en-2023-02-02.pdf (2002).

IUCN UK Peatland Programme. The UK Peatland Code, Version 1.0. Updated Version 2.0 (2023). Available at: https://www.iucn-uk-peatlandprogramme.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/Peatland%20Code%20V2%20-%20FINAL%20-%20WEB_0.pdf (2015).

Joosten, H. Wise Use of Mires and Peatlands (International Mire Conservation Group and International Peat Society, 2003).

Mcevoy, D. et al. Climate Change and the Visitor Economy: Challenges and opportunities for England’s Northwest. (Defra, Northwest Regional Development Agency, Environment Agency, UK Climate Impacts Programme). Sustainability Northwest and UKCIP (2006).

Millin-Chalabi, G., McMorrow, J. & Agnew, C. Detecting a moorland wildfire Scar in the peak District, UK, using synthetic aperture radar from ERS-2 and envisat ASAR. Int. J. Remote Sens. 35, 54–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2013.860658 (2014).

Thornton, A. & Lee, P. Publication bias in meta-analysis: its causes and consequences. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 53, 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00161-4 (2000).

Alamgir, M. et al. Economic, socio-political and environmental risks of road development in the tropics. Curr. Biol. 27, R1130-R1140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.067 (2017).

Turton, S. M. Managing environmental impacts of recreation and tourism in rainforests of the wet tropics of Queensland world heritage area. Geographical Res. 43, 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-5871.2005.00309.x (2005).

Kennett, S., Rintoul-Hynes, N. L. J., Sanders, C. H. & Biodiversity The effects of recreational footpaths on terrestrial invertebrate communities in a UK ancient woodland: a case study from Blean Woods, Kent, UK. 25, 107–119 https://doi.org/10.1080/14888386.2024.2333305 (2024).

Müllerová, J., Vítková, M. & Vítek, O. The impacts of road and walking trails upon adjacent vegetation: effects of road Building materials on species composition in a nutrient poor environment. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 3839–3849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.06.056 (2011).

Kociolek, A. V., Clevenger, A. P., Clair, S., Proppe, D. S. & C. C. & Effects of road networks on bird populations. Conserv. Biol. 25, 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01635.x (2011).

Zong, X., Tian, X. & Wang, X. An optimal firebreak design for the boreal forest of China. Sci. Total Environ. 781, 146822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146822 (2021).

Williams-Mounsey, J., Grayson, R., Crowle, A. & Holden, J. A review of the effects of vehicular access roads on peatland ecohydrological processes. Earth Sci. Rev. 214, 103528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103528 (2021).

Trombulak, S. C. & Frissell, C. A. Review of ecological effects of roads on terrestrial and aquatic communities. Conserv. Biol. 14, 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99084.x (2000).

Forman, R. T. T. & Alexander, L. E. Roads and their major ecological effects. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 29, 207–231. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.29.1.207 (1998).

UNEP. Global Peatlands assessment – the State of the World’s Peatlands: Evidence for Action Toward the conservation, restoration, and Sustainable Management of Peatlands https://doi.org/10.59117/20.500.11822/41222 (United Nations Environment Programme, 2022).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B conducted literature searching, screening and categorisation as well as data analysis and figure preparation. All authors contributed to production of the main manuscript text, editing and review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Booth, S.W., Midgley, N.G., Clewer, T. et al. The impacts of access infrastructure on temperate and boreal peatlands. Sci Rep 15, 44595 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28323-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28323-9