Abstract

Asphalt recycling promotes sustainable pavement construction but is limited by binder aging, stiffness, and decreased durability. Recycling agents (RAs) can improve ductility and low-temperature cracking resistance but often lower rutting resistance, whereas most warm-mix additives (WMAs) improve workability, rutting resistance, and aging durability while decreasing low-temperature flexibility. Despite these opposing effects, the combined use of high reclaimed asphalt binder (RAB) contents and their properties under aging has received little attention. This work assessed the rheological and aging properties of hot- and warm-mix asphalt binders containing 30% and 50% RAB, respectively, modified by an aromatic extract RA and Sasobit® WMA additive. Binders were analyzed in unaged, RTFO-, and PAV-aged conditions by rotational viscosity (RV), flow activation energy (FAE), multiple stress creep recovery (MSCR), linear amplitude sweep (LAS), frequency sweep, and bending beam rheometer (BBR) tests. It was found that RAB increased viscosity and thermal stability but decreased fatigue life and low-temperature cracking resistance. WMA reduced viscosity by approximately 20% in the unaged state, improved aging resistance, decreased rutting susceptibility, and reduced Jnr from 9.50 in the control binder to 0.85 in 50% RAB binders without RA addition. RA reduced viscosity by 30–70% and restored PG grades by one to two levels, but it worsened rutting resistance, increasing Jnr by 30–190% and diminishing percent recovery ®). Their combination, however, exerted a synergistic effect: RA enhanced the fatigue life (Nf) of WMA–RAB binders by 70–270% (e.g., PAV-aged 50% RAB–WMA’s Nf rose from 100,000 cycles to 378,000 cycles as a result of adding RA) and outperformed even neat WMA binders, while WMA reversed the detrimental effect of RA on rutting performance. BBR testing confirmed that although RAB accelerated embrittlement (reducing grades to PG XX–16 or below), RA consistently restored one to two low-temperature PG grades even under PAV aging, mitigating cracking susceptibility and aligning with LAS improvements in fatigue life. Overall, the RA and WMA integration resulted in binders with a good balance of rheological performance, enhanced aging durability, and superior fatigue and low-temperature resistance, thus presenting a workable approach toward the production of high-quality, sustainable, and high-RAP pavements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Asphalt pavement, the most widely used road pavement type globally, is exposed to a variety of environmental conditions during its use, such as oxidative attack from reactive oxygen species (ROS), UV and visible light exposure, air access, and freeze-thaw processes that causes negative effects on the properties of the pavement, advanced evaporative oxidation and change in the chemical components lead to an aged asphalt binder1,2,3,4,5.

Fatigue cracking and thermal fracturing caused by accumulated loading cycles and climatic changes should be resisted by the asphalt pavements6. Therefore, asphalt pavements are in need of a restoration every few years. However, construction of asphalt concrete pavements with virgin materials is costly and harmful to the environment7. Recycled asphalt pavement (RAP) materials could address these issues8,9. Accordingly, both environmental and financial concerns can be eased to some extent8,10.

Application of RAP material to asphalt binders and mixtures has its pros as well as cons. The application of RAP materials in asphalt mixtures is reported to possess a number of beneficial impacts. Firstly, previous studies have demonstrated that utilization of RAP materials in asphalt binders/mixtures would improve their rutting resistance11,12,13. Secondly, RAP materials have been found to improve the asphalt’s resistance to moisture when incorporated into the mixture, as reported by many studies11. However, there exist certain disparities in the fatigue durability of asphalt binders or mixtures that incorporate RAP constituents. Multiple studies have demonstrated the superior fatigue performance of asphalt binders or mixtures that incorporate RAP materials10,14,15,16. Conversely, some scholars have reported a reduction in the fatigue endurance limit of asphalt binders or mixtures that incorporate RAP materials17,18.

There are different aging conditions for asphalt binders in dams during their serving period. The functional groups of asphalt binders undergo a chemical change with aging, and hence, modify causing their stiffening19,20. Accordingly, there have been researches proposed in connection with adding recycling agents to aged asphalt binders. The recycling agent is not used to restore the process of aging but to restore the effect of aging on the rheology of the asphalt binder19,21.

Several research works have been conducted to investigate the impact of RAP utilization on asphalt binder and mixture properties. The findings of Ziari et al.22, show that the addition of RAP to asphalt mixtures contributes to enhancing the resistance of fracture at low temperatures. On the other hand, an opposite situation was observed at medium temperatures.

In their studies, Roja et al. and Singh et al. (2018, 2020)23,24 observed a reduction in the fatigue life of asphalt binders when incorporating RAP binder into mixtures. Conversely, Sun et al. 10 demonstrated an enhancement in the fatigue properties of asphalt binders that contained reclaimed asphalt binder (RAB). Furthermore, the studies conducted by corresponding researchers25,26,27 showed that it is accompanied by increasing the asphalt binder’s resistance to rutting that use reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) binder.

In order to mitigate the effects of global warming through the reduction of carbon dioxide emissions and energy use, the implementation of warm-mix asphalt (WMA) mixes was initiated in Europe during the latter part of the 1990s10,28. The utilization of this technique has several benefits. The benefits of using warm mix asphalt technology include: (1) expedited pavement accessibility for traffic28; (2) enhanced workability and increased hauling distance28; and (3) a drastic drop of 20–60 °C in the temperatures required for mixing and compacting28.

However, the application of WMA technology also has many shortcomings. The addition of WMA additives in asphalt mixes may lead to an increase in the overall cost of pavement construction28. Furthermore, WMA mixtures with organic additives, designed by using Sasobit® and Asphaltan B®, also show less resistance to moisture as compared with HMA mixtures28. This could be one interesting aspect of the lower adhesiveness of the asphalt binder to aggregates as a result of the optimal low level of the binder content of the WMA mixtures28,29.

According to the findings of Ayazi et al.30, the introduction of a silane-based warm mix asphalt (WMA) addition increases asphalt’s resistance to moisture more noticeably compared to a wax-based WMA additive. Saleh and Nguyen31 noted that asphalt mixtures incorporating a Tall-Oil based recycling agent and a chemical WMA additive exhibited superior fatigue performance compared to other mixture types. According to the findings of Ziari et al.32, the aging resistance of mixtures containing 50% RAP and waste cooking oil (WCO) recycling agent was superior to those made with aromatic extract recycling agents. According to Farooq et al.33, the incorporation of a recycling agent into asphalt mixtures has the potential to increase the maximum allowable amount of RAP materials. According to Zhang et al.34, the binders prepared with bio-rejuvenators exhibited greater activation energy and thermal stress tolerance in comparison to the unmodified binder.

According to research, a balanced improvement in asphalt binder performance can be achieved by mixing a petroleum aromatic recycling oil with a wax-based WMA additive, such as Sasobit35,36. As a crystallizing modifier, Sasobit makes the binder more rigid at high service temperatures, enhancing the asphalt’s durability and resistance to rutting. Additionally, it improves flow by lowering mixing temperature and binder viscosity, which promotes improved compaction and workability in warm-mix applications4,35. However, this extra stiffness from Sasobit may come at the expense of low-temperature flexibility; too much wax can make the binder more brittle, which reduces its capacity to relax stresses and raises the possibility of fatigue damage and thermal cracking in cold climes35. Oil-based rejuvenators made from aromatic extracts, on the other hand, have the opposite effect: they restore ductility and lower the viscosity and glass transition range of the binder by replenishing depleted maltenes in aged asphalt37. Such aromatic extract additives markedly improve low-temperature cracking resistance and fatigue life by softening the binder and enhancing its ability to deform without fracturing35,37. Naturally, this softening comes at a minor cost to high-temperature performance; when employed alone, rejuvenated binders may show a lower rutting resistance and a lower high-temperature modulus38. Importantly, when combined, the two modifiers enhance one another. While the aromatic oil mitigates the brittleness caused by wax, the wax component provides the high-temperature stiffness required to prevent rutting and permanent deformation, resulting in a binder with increased elasticity and tensile strain capacity at low temperatures35,36.

When compared to using either additive alone, researchers have found that a Sasobit–rejuvenator blend may successfully balance the rheological performance by increasing the binder’s high-temperature grade and low-temperature grade recovery at the same time36. According to Zhao et al., for instance, adding Sasobit by alone to an SBR-modified binder increased the softening point by more than 30 °C but significantly decreased ductility at 5 °C. In contrast, adding a waste-oil rejuvenator in addition to Sasobit resulted in a modified binder that had a higher softening point and more than doubled the base binder’s low-temperature ductility36. Better resistance to rutting and cracking in asphalt mixtures is the result of this synergistic enhancement. Additionally, by replenishing lighter fractions, the aromatic extract rejuvenator reduces oxidative aging; at the same time, Sasobit’s lower mixing temperatures prevent age-hardening during manufacturing, resulting in a slower aging of the binder over time35,37. The ability to control possible moisture durability issues is another significant advantage of the combined modification. It has been demonstrated that adding appropriate WMA additives or anti-stripping agents in addition to Sasobit counteracts stripping and maintains moisture resistance, whereas adding a rejuvenating oil alone can make the mix more susceptible to moisture (by decreasing binder cohesion and adhesive bond with aggregates)38.

Understanding the behavior of asphalt binders after long-term aging can give a thorough insight into selecting the appropriate additives, which are less vulnerable to changes occurring due to aging. Moreover, according to existing literature, it has been shown that recycling agent incorporation negatively affect the high-temperature performance of asphalt binders. However, available literature show that the presence of wax-based WMA additives increases the thermal resistance of binders at high temperatures. Nevertheless, it is important to note that although these high-temperature properties are improved, the strength of the binder at low temperatures is reduced. Therefore, as supplement materials of the research, the WMA additive containing a recycling agent is employed. From available literature, it can be inferred that very little research has been done on the rheological and aging characteristics of non-rejuvenated and rejuvenated hot- and warm-mix RABs. Hence, this study aimed to evaluate the rheological properties of non-rejuvenated and rejuvenated hot and warm-mix binders, namely those containing 30% and 50% RAB. In addition to this, an investigation was conducted in order to evaluate how well these binders resist against the aging mechanism by analyzing the outcomes of numerous tests conducted at different stages of aging.

Materials

Base binder

The type of asphalt binder adopted in this investigation was PG 58-28 widely used in many districts. Reclaimed asphalt binder (RAB) was also extracted from reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) collected from a highway surface, aged 8 years. The RAP binder was recovered with Trichloroethylene according to ASTM D2172M-17 and recovered in a rotary evaporator according to ASTM D5404M-12. Fischer-Tropsch wax-based warm -mix additive (with a melting point of 100 °C). Furthermore, an aromatic extract recycling agent, obtained from refined crude oil, was used to mutate and regain the chemical equilibrium of the aged binder due to the reduction of viscosity. Details of the base binder, RAB, warm-mix additive, and recycling agent are given in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Experimental program

Preparation of asphalt binder samples

In this research, each asphalt binder is denoted by a specific code according to its aging status and mix configuration, which are presented in Table 4. The first step in blending asphalt materials is to determine the appropriate mixing temperature. According to the MS-2 asphalt mix design methods39, the mixing temperature for asphalt mixtures is defined as the temperature at which the rotational viscosity reaches 0.17 ± 0.02 Pa s. Accordingly, in this study, the mixing temperatures were determined and are presented in Table 5. As all samples were mixed and prepared in their original (unaged) state, only the mixing temperatures of the unaged samples are reported.

To prepare the HMA samples, 500 g of neat asphalt binder and the required amount of RAB (according to the target content) were first heated separately to the specified mixing temperature. The RAB was then incorporated at 30% and 50% contents along with the optimum recycling agent content (determined in subsequent sections), and the components were blended with a low-shear mixer at 400 rpm for 15 min.

For the WMA samples, 3% WMA additive was initially mixed with the 500 g base binder at the mixing temperature using a low-shear mixer at 400 rpm for 15 min40,41. A 3% dosage was selected based on literature review42,43, manufacturer recommendations, and its potential beneficial effects on asphalt properties. Higher dosages (> 4%) were avoided due to adverse effects on low-temperature cracking performance. Subsequently, 30% and 50% RAB and the recycling agent were incorporated into the mixture at the mixing temperature and stirred for an additional 15 min at 400 rpm.

Short-term and long-term aging methods

The Rolling Thin Film Oven (RTFO) aging procedure, according to ASTM D2872-19, is used to simulate the short-term aging of asphalt binders that occurs during hot mix asphalt production and placement. In this study, approximately 35 g of binder are poured into each thin-walled glass bottle, which is then placed horizontally on a rotating carriage inside a forced-draft oven maintained at 163 °C. As the carriage rotates at 15 revolutions per minute, a constant air flow of about 4000 ml/min is directed into each bottle, exposing the binder to heat and oxidation. The samples remain under these conditions for 85 min, after which the bottles are removed and the aged binder residue is collected for further testing of properties.

The Pressure Aging Vessel (PAV) procedure, according to ASTM D6521-19a, is designed to simulate the long-term oxidative aging of asphalt binders that occurs during in-service pavement life. In this test, residue from the RTFO-aged binder is placed in shallow pans and arranged inside a sealed stainless-steel pressure vessel. The vessel is then pressurized to approximately 2.07 MPa with compressed air and maintained at a temperature of 100 °C. Under these conditions, the binder samples are exposed for 20 h, during which the combination of elevated temperature and high air pressure accelerates oxidation, producing an aged binder. After completion, the samples are cooled and recovered for further testing of rheological and physical properties to evaluate their long-term performance characteristics.

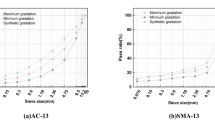

Optimum content of the recycling agent (RA)

To determine the optimum dosage of the recycling agent, the performance grade (PG) grading framework was adopted as a practical criterion for evaluating binder restoration. Several previous studies17,44,45,46 have employed the approach of selecting the recycling agent content at which the PG grade of the rejuvenated binder matches that of the corresponding neat binder. This methodology has been shown to effectively ensure that the restored binder regains the target rheological characteristics of the virgin binder.

In the present study, the recycling agent dosage was systematically varied to restore the low-temperature continuous PG of the reclaimed asphalt binder blends (30% and 50% RAB) to a level comparable with that of the neat binder. The high-temperature PG grade was subsequently verified to ensure equivalent or superior PG performance than that of the neat binder. The dosage added to the RAB-contained binders is varied from 2 to 10% with the interval of 2%. This was based on preliminary trials indicating that this step size produced distinct and measurable variations in rheological parameters, facilitating the establishment of a linear relationship between recycling agent dosage and the low-temperature continuous PG value.

Figure 1a and b illustrate the relationship between recycling agent dosage and the low-temperature continuous PG. The continuous low-temperature PG values of the unaged HMA (OB) and WMA (WB) binders were − 30.2 °C and − 26.8 °C, respectively. The dosage at which the continuous low-temperature PG of the rejuvenated binder reached that of the neat binder was considered a candidate for the optimum content, provided that the corresponding high-temperature PG grade also equaled or exceeded that of the neat binder. At these identified dosages, the rejuvenated binders exhibited comparable or improved high-temperature PG grades relative to their unaged counterparts, which is shown in Table 6. Accordingly, the optimum recycling agent contents were determined as follows:

-

O30: 4.9% O50: 7.3%.

-

W30: 4.3% W50: 6.5%.

Table 6 summarizes the PG grades of the original HMA and WMA binders alongside their counterparts incorporating 30% and 50% RAB, as well as the grade changes resulting from the addition of the optimum recycling agent content. These grades align with the performance trends discussed later in the MSCR and BBR results. As shown in Table 6, adding the optimum content of recycling agent to HMA and WMA binders with 30% and 50% RAB effectively restores the low-temperature grade to that of their original counterparts (OB and WB). At the same time, their high-temperature grades reach, or in some cases exceed, those of the original binders.

Experimental design of asphalt binders

The mix design and test methods of asphalt binders used in this study are shown in Fig. 2.

Test methods

Rotational viscosity (RV) test

In this article, the rotational viscosity of the asphalt binder was determined with a Brookfield viscometer. Measurements were done at different temperatures (110 °C, 135 °C, 150 °C and 165 °C), using the testing protocol detailed in AASHTO T316-19. This experiment was conducted with three replicates tested and average values reported.

Flow activation energy approach

Asphalt binders at high temperatures possess non-linear viscoelastic behavior, and they have viscous flow in which a thermal activation occurs47. In order to measure the workability of asphalt binders as well as their resistance to flowing, researchers have proposed the flow activation energy method34. The method in the present work recommended to measure the temperature dependence of viscosity and inserting it into Eq. (1)34,48:

The above equation is the formula to calculate rotational viscosity (η) of a binder in terms of flow activation energy (Ef), universal gas constant (R), temperature (T) and a constant (A). Rotational viscosity is given in Pascal-second (Pa s) and flow activation energy Ef in kJ mol−1). The value of the universal gas constant (R) is 8.314 × 10− 3 kJ mol−1 K−1, and T is in Kelvin (K). The (A) constant is as well put into the equation.

Frequency sweep test

A dynamic shear rheometer (DSR) was used to evaluate various binder combinations over a frequency range of 0.1–60 Hz at temperatures of 52 °C, 58 °C, and 64 °C, with a constant shear strain of 1% to maintain linear viscoelastic behavior49. Master curves were obtained for the complex modulus from the Christensen-Anderson-Marasteanu (CAM) model (Eq. (2)50. Because plateau regions in phase angle—frequency relationships exist, the Double Logistic (DL) of phase angle master curves, which exhibit plateau regions in phase angles, was employed to model the phase angle–frequency behavior more accurately than traditional models51. he DL model, shown in Eq. (3)51 was used with the reference temperature of 58 °C, with horizontal shifting applied accordingly. This experiment was conducted with three replicates tested and average values reported.

In the Eq. (2), \(\left| {GM} \right|\) = 109 Pa, that is, the glassy shear modulus. The constants k and m are fitting parameters, \({f_{red.~frequency}}\) is the reduced frequency in Hz and \({f_{crossover}}\) is the cross-over frequency in Hz.

Where \({\delta _p}=\) phase angle plateau, \({f_p}=\) the frequency at which the phase angle plateau occurs (Hz), H(u)= Heaviside step function, \({f_{red}}=\) reduced frequency (Hz), \({\delta _L}=\) parameter that stands for the left side of the plateau zone, SR = correction factor for the right of the plateau zone, and SL = correction factor for the left side of the plateau zone.

Multiple stress creep recovery (MSCR) test

The test was conducted on a Dynamic Shear Rheometer (DSR) equipment equipped with a 25 mm diameter plate and gap of 1 mm. The test was conducted at three predetermined temperatures, i.e., 52 °C, 58 °C, and 64 °C in accordance with the provisions recommended by AASHTO T350-19. The rheological measurements on binders were performed at two stress levels of 100 and 3200 Pa without relaxation applied in between. According the given specification, a total of 10 cycles were conducted for each stress levels. Cycles consisted of a 1 s loading period followed by a 9 s rest period. This experiment was conducted with three replicates tested and average values reported.

Linear amplitude sweep (LAS) test

This test is proposed to assess the fatigue behavior of binders using DSR machine. The characterization test was performed in two steps at a temperature of 20 °C according to the procedure described in AASHTO TP101: Firstly, the pristine asphalt binders were subject to a frequency sweep test in which the property was evaluated at frequencies (ω) ranging from 0.2 to 30 Hz, while subjected to a strain amplitude of 0.1%. In Addition, an amplitude sweep experiment with increasing the amplitude by steps from 0.1 up to 30% while keeping the 10 Hz frequency was performed. Afterwards, a check to assess the fatigue life according to the given criterion was performed. This experiment was conducted with three replicates tested and average values reported.

Bending beam rheometer (BBR) test

Recycled asphalt binder (RAB) contained in asphalt binders has a substantial impact on the low-temperature performance of asphalt binders. Therefore, it is important to test their performance against low temperature cracking. An experiment was carried out at various temperatures (− 6 °C, − 12 °C, and − 18 °C), resulting in the estimation of two essential parameters of the model, the creep rate (m-value) and the creep stiffness (S), during 60 s period. The experiment followed AASHTO T313-19, with three replicates tested and average values reported.

Results and discussions

Rotational viscosity (RV) test results

Figure 3 presents the rotational viscosity results for the studied binders at different temperatures and aging conditions. In general, both short-term and long-term aging increased the viscosity of all binder types. This well-known effect is associated with the transformation of small molecular fractions such as resins into larger asphaltenes, which increases binder stiffness52. By comparing Fig. 3a–c, it is inferred that the addition of RAB further elevated viscosities due to the inherently aged, asphaltene-rich nature of reclaimed binder.

Effect of WMA additive

As expected, adding the wax-based warm-mix additive lowered the viscosity compared to the control binder. On average (across all tested temperatures), the unaged WMA binder (WB) showed about a 21% reduction in viscosity relative to the base binder (OB). This reduction was more noticeable at higher temperatures (≥ 135 °C). This behavior reflects the long-chain hydrocarbon composition of Sasobit®, whose melting point exceeds 100 °C53,54, enabling melting and liquefaction at mixing and compaction temperatures52. By extending the plastic range, Sasobit® improves flowability and facilitates mixing. Importantly, WMA binders also exhibited lower relative viscosity increases upon RTFO and PAV aging (35% and 197%, respectively) compared with the base binder (45% and 247%). The crystalline structure formed by Sasobit develops into a three-dimensional network that traps the lighter oil fractions of the asphalt binder. As the crystal lattice grows, these lighter molecules become confined within it, which limits their tendency to evaporate. At the same time, the dense and interconnected crystal framework reduces direct contact between oxygen and asphalt molecules, thereby slowing down the oxidation process55.

WMA with RAB: effects of RA

Direct comparisons demonstrate that RA substantially counteracts the stiffening from RAB incorporation at both 30% and 50% contents. For example, under unaged conditions at 135 °C, the viscosity of W30 was reduced from 0.35 to 0.22 Pa.s (− 37%) with RA (Fig. 3d), while W50 (Fig. 3e) dropped from 0.42 to 0.26 Pa.s (− 38%). Similar reductions persisted under RTFO aging (RW30: 0.43→0.28 Pa.s, − 35%; RW50: 0.57→0.36 Pa.s, − 37%) and after PAV aging (PW30: 0.85→0.57 Pa.s, − 33%; PW50: 1.11→0.65 Pa.s, − 41%). At compaction temperatures (135–150 °C), RA lowered viscosities by 30–70%, often reducing them below the level of the corresponding WMA base binder. These findings indicate that RA and the WMA additive act synergistically to improve workability.

The softening effect of RA arises from its high resin content, which replenishes maltenes lost during aging and restores the colloidal balance of the binder. Although rejuvenated binders showed somewhat higher susceptibility to volatility-related stiffening upon long-term aging, they consistently maintained lower viscosities than non-rejuvenated RAB–WMA blends. This means that even if RA accelerates some oxidative processes, the net effect remains beneficial: rejuvenated WMA binders are always less stiff than their no-RA counterparts.

Influence of RAB content

The RA effect was stronger in 30% RAB mixes than in 50% RAB mixes. At 30% RAB, viscosity reductions of approximately 55–60% were observed at 150–165 °C, effectively restoring workability to or below that of the base WMA binder. At 50% RAB, reductions were still substantial (40–45%) but less than 30% RAB; for instance, at 165 °C after RTFO, RW50R remained somewhat stiffer than the aged base WMA binder. This suggests that while RA extends the workable limit of RAB usage, its efficiency diminishes at higher reclaimed contents and under severe oxidative conditions.

Main takeaways

Together, these results confirm that the warm-mix additive alone lowers viscosity and improves aging resistance, while the recycling agent is essential to offset the stiffening from RAB, particularly at high reclaimed contents. Most importantly, the combined use of RA and WMA additive provides a synergistic effect, ensuring that recycled WMA binders remain workable during mixing and compaction and retain this benefit even after aging.

Flow activation energy (FAE) results

General effects of aging and WMA additive

Flow activation energy (FAE) reflects the temperature sensitivity of binder viscosity. A higher FAE value indicates lower temperature susceptibility at mixing and compaction temperatures since RV test is conducted at temperatures above 110 °C. This suggests that lower temperature susceptibility is aligned with lower workability and higher mixing and compaction challenges. As shown in Fig. 4a, long-term aging increased FAE across all binder types, suggesting that oxidative hardening makes the binders less sensitive to temperature fluctuations at mixing and compaction temperatures and thus enhances thermal stability.

The presence of the WMA additive further elevated FAE in the virgin binders. This effect can be attributed to the wax component of Sasobit®, which melts and mixes into the binder above 110 °C. By forming a crystalline network at lower temperatures and liquefying at higher temperatures, the additive lowers the temperature susceptibility of binders. Although WMA additive lowered the temperature susceptibility, its role in reducing the viscosities at higher temperatures (compaction temperature) is beneficial to cutting down the energy consumption due to bringing the favorable compaction viscosity at lower temperatures.

Influence of RAB and aging

Interestingly, the FAE values slightly decreased after RTFO aging, particularly in binders containing RAB. This observation does not necessarily contradict the expected increase in stiffness upon oxidation, as FAE primarily represents the temperature sensitivity of viscous flow rather than absolute viscosity. The volatilization of light fractions and the development of asphaltene networks during RTFO may induce deviations from Arrhenius-type behavior, leading to reduced apparent activation energies. Moreover, partial blending between aged and virgin binder phases in RAB blends can create compositional heterogeneity, wherein the softer fraction dominates the high-temperature flow response. Therefore, the reduction in FAE likely reflects a transition from thermally activated molecular flow to deformation governed by microstructural rearrangement, rather than a true softening effect.

Effect of recycling agent in WMA binders

In contrast to the stabilizing effect of WMA additive and RAB, the recycling agent consistently reduced FAE across all binder types, as illustrated in Fig. 4b. For both 30% and 50% RAB blends, and under unaged, RTFO, and PAV conditions, the addition of RA led to a drop of approximately 10–25% in FAE relative to the corresponding no-RA blends. This means that binders with RA are more temperature susceptible, with viscosity responding more strongly to changes in high temperatures, bringing about some compaction benefits.

Mechanistically, this decrease in FAE can be ascribed to the aromatic and resin-rich nature of the recycling agent, which disrupts polar interactions and weakens intermolecular associations, thereby enhancing molecular mobility. Notably, WMA binders with RA often exhibited FAE values comparable to or below those of the base WMA binder, underscoring their improved constructability.

Effect of RAB content, aging, and RA

The degree of RA benefit depended on RAB content and aging state. At 30% RAB, RA lowered FAE substantially, providing a favorable balance between workability during construction and acceptable long-term performance after aging. At 50% RAB, RA again reduced FAE, with PW50R and RW50R showing marked improvements in compaction. However, the relative effect was smaller than at 30% RAB, and long-term aging still left these binders with relatively high FAE compared to RA-contained 30% RAB mixes. Thus, RA helps extend the practical limit of RAB incorporation in WMA, but its rejuvenating capacity is somewhat constrained at higher reclaimed contents under severe oxidative conditions.

Main takeaways

Overall, the combination of WMA additive and recycling agent provides complementary benefits. The WMA additive increases FAE, while the RA reduces FAE, improving workability and compaction. In practice, these opposing effects act synergistically: the WMA wax moderates baseline viscosity and provides durability benefits, while the RA ensures that mixtures containing reclaimed binder remain workable at production and compaction temperatures. Among the tested binders, the 50% RAB WMA with RA provided the most favorable workability.

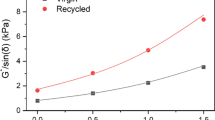

Frequency sweep test results

Interpretation of the master curve data

Figures 5 and 6 present the master curves for the complex modulus and phase angle, respectively, pertaining to various combinations of binders. The corresponding figures illustrate that the measured values are those that comprise the corresponding values at the reference temperature (58 °C), and also values shifted from the temperatures of 52 °C and 64 °C. Higher complex modulus is indicating the greater resistance of binders against shear stresses, and only this value is unable to accurately describe the binders’ elasticity. For this, phase angle is the representative of the binders’ elasticity, and lower phase angles are attributed to the higher storage modulus and lower loss modulus of binders. The energy held in binders following the loading process is commonly referred to as the storage modulus, which is associated with the reversible deformations. However, some energy is lost by non-recoverable deformations, which is associated with the loss modulus; as a result, lower phase angles show that the binders have a better elasticity. In addition, higher frequencies in master curves are correspond to the behavior of binders similar to low temperatures, and lower frequencies are attributed to that of higher temperatures.

General effect of aging and RAB addition

The results depicted in Figs. 5 and 6 indicate that the complex modulus of aged binders is elevated while the phase angle values are reduced in comparison to unaged binders. The cause of this occurrence lies in the conversion of small molecules into asphaltenes during the process of ageing. Moreover, according to Figs. 5a and b and 6a, and b, the inclusion of RAB in binders yields a similar outcome, given that RAB possesses a high level of ageing and enhances the rigidity of binders. It is important to acknowledge that the inclusion of RAB has a greater impact on the complex modulus when low frequencies are taken into account. This is due to the fact that the behaviour of binders becomes more identical as they get closer to the glassy modulus at high frequencies, but the differences in the behavior and also the role of additives is more evident at lower frequencies. This suggests that the incorporation of RAP materials into pavements designed for high-speed vehicles does not have a substantial impact on enhancing stiffness.

Effect of WMA additive

The study’s findings indicate that the incorporation of WMA additive with RAB leads to increased complex modulus (G*) values and decreased phase angle values when compared to unmodified binders (Figs. 5c, 6c). This shows that these binders have a better resistance against shear stresses, and also they have a higher elasticity. This can be due to the fact that apart from the rigidifying influence of RAB, the WMA additive addition also elevates the binders’ stiffness at the temperatures below its melting point56. This occurrence can be explained by the following: the crystalline structure of WMA additive maintains active at the temperatures below its melting point, contributing to restraining the activity of molecules56. Another point that should be mentioned is that the complex modulus values of aged WMA-modified binders are closer to those of unaged binders than they are to those of unmodified binders, suggesting that the aging resistance of modified binders is more desirable.

Effect of RA in unaged and aged WMA binders

By comparing Figs. 5d and e and 6d, and e, it is inferred that WMA-additive modified binders incorporating RAB and the recycling agent exhibit reduced G* values and increased phase angle values in comparison to the binders that do not include the recycling agent. This finding demonstrates that the incorporation of the recycling agent into binders results in a reduction in their stress tolerance, suggesting that the addition of the recycling agent has a negative impact on the binders’ ability to resist permanent deformation. It is further noted that the addition of the recycling agent into the 50% RAB-contained binder aggravates its high-temperature performance more significantly than the 30% RAB-contained binder. The observed phenomenon can be explained by the increased concentration of the recycling agent in the 50% RAB binder compared to the 30% RAB binder. Additionally, WMA binders containing RAB and the recycling agent (PW30R and PW50R) are less affected by the PAV aging as compared to their no-RA counterparts (PW30 and PW50). It can be concluded that although the addition of the recycling agent worsens the high-temperature performance of binders, its adverse influence is less considerable regarding the long-term high-temperature performance of binders.

MSCR test results

General effects of RAB and WMA

Figure 7 presents the non-recoverable creep compliance (Jnr) and percent recovery (R) values for the studied binders at 3.2 kPa Compared to the base binder (OB). Binders containing RAB consistently showed lower Jnr values and higher R values, confirming the expected improvement in rutting resistance due to the greater stiffness contributed by the reclaimed binder. For instance, at 64 °C, Jnr decreased from 9.50 kPa−1 in OB to 2.30 in O50 (Fig. 7a).

As shown in Fig. 7a and b, the incorporation of WMA additive further enhanced these effects, especially when combined with RAB. At 64 °C, W50 exhibited Jnr = 0.85 and R = 4.8%, significantly outperforming OB. These findings confirm that WMA and RAB act synergistically to improve rutting resistance and elastic recovery, as also evidenced in the viscosity and FAE results. Lower production temperatures of WMA reduce thermal aging in the binder construction stage, which helps preserve binder performance during mixing and compaction.

Short- and long-term aging effect

By comparing the results of Fig. 7a, b with those of Fig. 7c–f, it is induced that the positive effect of WMA and RAB goes into aging. Binders with RAB showed better short-term (RTFO) aging resistance than the base binder, largely due to the inherent aged character of the reclaimed material. After long-term PAV aging, the differences narrowed, with RAB-modified binders showing Jnr and R values approaching those of the unmodified binder. Still, WMA binders retained advantages such that they outperformed unmodified binders by approximately 20% in short-term and 10% in long-term rutting resistance, consistent with reduced thermal oxidative hardening at lower production temperatures. Overall, WMA without RAB offered the best short-term aging resistance, while WMA with 50% RAB provided the highest long-term rutting resistance due to the stiffening effect of the high RAB fraction.

Effect of recycling agent in WMA binders

A central point of interest for this study is the comparison of WMA binders with and without RA. The results clearly demonstrate that RA addition increases Jnr and decreases R across all binder types, indicating reduced rutting resistance and elastic recovery. This confirms that RA softens the binder and reduces its elastic recovery, thereby undermining the rutting benefits provided by RAB and WMA.

The magnitude of this negative effect depends on RAB content. At 30% RAB, the increase in Jnr from adding RA was about 29% (W30 → W30R), while at 50% RAB the increase was nearly 193% (W50 → W50R). This pattern reflects the greater proportion of RA required in high-RAB mixes, which exerts a stronger softening effect. For PAV-aged binders, PW50R showed Jnr = 0.54 and R = 24.82%, nearly double the Jnr and half the recovery of PW50 (Jnr = 0.21, R = 48.51%). These outcomes confirm that RA significantly compromises rutting resistance, particularly in 50% RAB binders.

Balancing workability and rutting resistance

Although RA diminishes rutting resistance, its role must be viewed in the broader context of workability. As demonstrated in the viscosity and FAE analyses, RA is essential to reduce mixing viscosity and flatten thermal sensitivity, enabling the incorporation of high levels of RAB in WMA combinations. From a practical standpoint, RA makes these binders workable in the field, even if some rutting resistance is sacrificed. Therefore, the combined use of RA and WMA additive represents a performance trade-off such that RA restores constructability, while WMA contributes to rutting resistance and aging durability.

Main takeaways

The overall MSCR findings highlight that:

-

WMA + RAB (without RA): best combination for rutting resistance and elastic recovery.

-

RA addition: necessary for workability but increases Jnr and reduces R, especially at 50% RAB.

-

Practical balance: at 30% RAB, RA-contained WMA binders have acceptable rutting resistance with major gains in workability. At 50% RAB, rutting performance is compromised, suggesting a need for RA.

Together, these results reinforce one of the main objectives of the study: RA and WMA act synergistically to enable sustainable high-RAB asphalt mixes, but careful balancing is needed to avoid sacrificing rutting performance.

Traffic loading grading of binders

According to AASHTO M332-21, high-temperature performance grading of asphalt binders requires that the stress sensitivity (Jnr−diff) not exceed 75%. Additionally, specific Jnr₃.₂ (kPa⁻¹) thresholds correspond to different traffic levels: Standard (S: 2 < Jnr ≤ 4.5), High (H: 1 < Jnr ≤ 2), Very High (V: 0.5 < Jnr ≤ 1), and Extremely High (E: Jnr ≤ 0.5). In this study, high-temperature traffic grading was evaluated across binder types, from unaged to PAV-aged, to assess the effects of aging. The grading results are presented in Fig. 7, with designations “S,” “H,” “V,” and “E” indicating each binder’s traffic level classification.

The findings indicated that the incorporation of RAB increases the traffic grading category. For example, incorporation of 50% RAB increases the base binder’s performance grade from “S” to “V” at 58°C, while the WMA additive increases the grading further, especially in binders with 50% RAB, indicating a combined effect that enhances resistance to rutting. On the other hand, the recycling agent tends to lower traffic grading, but is usually only by one grade at most. The importance to traffic grade is less for the recycling agent with 10% RAB, while traffic grade is not influenced for WMA binders with 30% and 50% RAB at 52 °C. This indicates that WMA-RAP mixes with recycling agents do not distinctly reduce rutting performance for moderate climates. Also, there are minimum changes in the performance grades of RTFO aged binders, providing the feasibility of using WMA additives with recycling agents in RAP mixtures.

LAS test results

Damage evolution assessment

The Damage Evolution curves of different binder compounds are shown in Fig. 8. This integrity versus degree of damage are material dependent plots which correlates the material’s integrity with the amount of damage (or factor of growth of the damage) in the material, subjected with the repetitively loading. As demonstrated in Fig. 8a and d, the Df in binders with WMA additives is higher than in the unmodified binder. It shows that when WMA additive is incorporated in binder, the fatigue life is increased. This is because the asphalt binders with larger Df can sustain higher amount of damage accumulations for the point of failure and thus provide more energy by the extension of the strain amplitude; consequently, the binders tend to have better fatigue performance. It is also indicated that the decreasing rate of integrity values (C) in binders containing RAB is higher, and is therefore associated with a lower ability to store energy before the breaking point. Furthermore, by comparing the results of Fig. 8e and f with those of Fig. 8a, the application of aging causes the damage evolution curves of WMA-additive modified binders with RAB to get closer to the base binder, but they still tend to have lower Df values compared to the base binder. In addition, as shown in Fig. 8a and b, and 8c, the application of aging in HMA binders causes their decreasing rate of integrity values to become escalated.

As can be seen in Fig. 8, the addition of the recycling agent leads to higher Df values, demonstrating that the recycling agent makes the fatigue life longer. In particular, the addition of recycling agent to binders with 50% RAB makes the Df value greater than that of the base binder, representing that the recycling agent is highly influential in improving the fatigue properties when it is combined with high RAP materials. In addition, aging has the most impact on binders containing 30% RAB with the recycling agent in such a way that as the aging progresses, the rate of the decline in the C parameter decreases. However, aging does not affect the norm of damage evolution in binders containing 50% RAB and the recycling agent (O50R), yet it causes the fatigue life to become shorter than that of the unaged binders.

Predicted fatigue life

Effects of RAB and aging

The fatigue life (Nf) obtained from the LAS test provides an assessment of the damage tolerance of binders under cyclic loading. As shown in Fig. 9a, the neat base binder (OB) achieved an Nf of approximately 274,000 cycles. The incorporation of RAB significantly reduced fatigue life, particularly at higher RAB contents such that O30 = 164,180 and O50 = 115,955. This decline reflects the brittle nature of aged reclaimed binder, which accelerates crack initiation.

Aging exacerbates this reduction. For instance, R30 decreased to 139,408 cycles after RTFO and to 113,222 cycles after PAV, while R50 fell to 93,453 (RTFO) and 62,688 (PAV). These results highlight the greater aging sensitivity of RAB-modified binders compared to neat binders, where fatigue losses were more significant.

Effects of WMA additive without RA

In contrast, WMA-modified binders demonstrated enhanced fatigue resistance across all conditions. As shown in Fig. 9b, WB reached 329,307 cycles, exceeding OB, and retained higher fatigue life even after RTFO (RWB = 306,255) and PAV (PWB = 275,789). This improvement is attributed to the crystalline layer formed by the waxy WMA additive, which acts as a barrier against oxygen diffusion and limits oxidative aging57. As a result, WMA binders deteriorated less severely with time than conventional HMA binders.

Nevertheless, introducing RAB into WMA without RA still lowered fatigue life. W30 and W50 recorded 205,225 and 150,742 cycles, respectively, which are higher than the equivalent HMA binders (O30 and O50), but below the WMA base binder. This shows that while the WMA additive can partially offset the reduction effect RAB on fatigue life, it does not fully eliminate it.

Effect of recycling agent in WMA binders

The most striking effect arises from RA addition. In all aging levels, RA substantially improved fatigue life in WMA binders. For example, W30 increased by 68% after RA addition (W30 → W30R: 205,225 → 344,820), while W50 nearly tripled (150,742 → 436,375). Similar gains were seen under RTFO (RW30 → RW30R: +76%; RW50 → RW50R: +217%) and PAV (PW30 → PW30R: +76%; PW50 → PW50R: +270%). The binders with 50% RAB and RA (W50R, RW50R, PW50R) consistently indicated the highest fatigue lives in the dataset, surpassing even the WMA base binders. This rejuvenating effect can be mechanistically explained by the resin-rich aromatic fractions in RA, which restore maltenes lost during aging and disrupt rigid asphaltene networks.

The LAS results reinforce and extend the findings from viscosity, FAE, and MSCR analyses. Viscosity and FAE showed that RA lowers viscosity and reduces flow activation energy, improving molecular mobility. While MSCR confirmed that this softening reduces rutting resistance, the LAS results reveal the compensating advantage of markedly improved fatigue durability.

For example, PW50 (no RA) had outstanding rutting resistance (Jnr = 0.21, R = 48.5%) but poor fatigue life (102,269 cycles). With RA addition, PW50R exhibited weaker rutting resistance (Jnr = 0.54, R = 24.8%) but a nearly fourfold increase in fatigue life (377,768 cycles). Thus, RA creates a deliberate trade-off such that it reduces rutting resistance but restores fatigue resistance, especially critical in high-RAB WMA binders.

Main takeaways

From a design perspective, the balance between rutting and fatigue must be tuned based on RAB content and service conditions. At 30% RAB, WMA binders with RAB achieve balanced performance: moderate improvements in fatigue with manageable losses in rutting. At 50% RAB, RA becomes indispensable, elevating fatigue life by more than 200% while keeping rutting resistance above neat HMA binders.

BBR test results

Effects of RAB and aging

The BBR results (Figs. 10a, 11a) show that the base binder (OB) satisfies the critical thresholds of stiffness (S ≤ 300 MPa) and m-value (m ≥ 0.3) at − 18 °C, with S = 196 MPa and m = 0.37. According to PG grading rules, this performance corresponds to a low-temperature grade of PG XX–28. In contrast, binders modified with RAB exhibited higher stiffness and lower m-values, especially at elevated RAB contents. For example, O30 and O50 recorded S = 262 and 300 MPa at − 18 °C, with m-values of 0.27 and 0.24, respectively. These results indicate that O30 fails by the m-value criterion, while O50 fails by both stiffness and m-value, reducing their effective PG low-temperature grades to PG XX–22, and PG XX-16, respectively. Aging further increases these effects, as seen with P30 (m = 0.24) and P50 (m = 0.22) at -6 °C, both of which failed at − 6 °C. This confirms that RAB accelerates low-temperature embrittlement and reduces resistance to thermal cracking, consistent with its effect on viscosity and LAS fatigue life.

WMA effects

In contrast to its beneficial role in reducing viscosity and improving mixing workability, the WMA additive deteriorated the low-temperature performance of the binders. As shown in Figs. 10b and 11b, the WMA base binder (WB) failed the m-value criterion at − 18 °C (S = 245 MPa, m = 0.28), reducing its PG low-temperature grade to PG XX–22 compared to OB at PG XX–28. This deterioration is attributed to the crystallization of long-chain hydrocarbons in Sasobit®, which stiffen the binder matrix at cold temperatures and limit relaxation capacity. Thus, while WMA is advantageous for rutting resistance and workability, it comes at the expense of low-temperature flexibility. The detrimental effect of Sasobit® was lower in high-RAB blends: W30 graded to PG XX–16, one grade drop over O30 at PG XX–22. Similarly, W50 graded at PG XX–16, offering no grade drop over O50.

Recycling agent in WMA binders

The addition of a recycling agent (RA) was highly effective in restoring the low-temperature performance of WMA–RAB binders. For example, W30R achieved S = 85 MPa and m = 0.42 at − 12 °C, passing both thresholds and recovering the PG grade to XX–22, compared to W30 at XX–16. Similarly, W50R improved the low-temperature cracking resistance from PG XX-16 (W50) to PG XX-22.

The trend persisted under aging. RW30R and RW50R both outperformed their non-rejuvenated counterparts, with RW30R maintaining a PG XX–22 classification compared to RW30 failing at XX–16. Even after PAV, PW50R performed substantially better (S = 432 MPa, m = 0.18) than PW50 (S = 525, m = 0.10), shifting its grade from effectively PG XX–10 to PG XX–16. These results confirm that RA is critical for maintaining acceptable cracking resistance in WMA–RAB binders.

PG Low-Temperature grading

Summarizing the PG grading outcomes:

-

OB = PG XX–28; WB = PG XX–22.

-

O30 = PG XX–22; W30 = PG XX–16; O30R = PG XX-28 and W30R = PG XX–22.

-

O50 and W50 = PG XX–16; O50R = PG XX–28; W50R = PG XX–22.

-

After PAV, RAB blends without RA dropped to PG XX–10, whereas RA improved them by at least one grade.

These classifications illustrate two clear conclusions: WMA alone deteriorates low-temperature grading, while RA consistently restores grades, particularly in high-RAB binders.

Cross-comparison with other properties

The BBR results provide a low-temperature complement to the earlier viscosity, FAE, MSCR, and LAS findings. Viscosity and MSCR showed that RA softens binders and reduces rutting resistance; BBR confirms that this same softening enhances low-temperature flexibility. LAS fatigue results also demonstrated extended fatigue life with RA, consistent with the lower stiffness and higher m-values observed here. Meanwhile, the increased FAE in WMA binders explained their thermal stability but aligns with the reduced relaxation capacity that underperforms their BBR performance. Overall, the results demonstrate a performance balance: WMA favors rutting resistance but compromises cracking resistance, while RA mitigates this trade-off by restoring flexibility and extending fatigue durability.

Conclusions

In this study, a number of questions based on the research hypothesis were answered: (a) How the adverse impacts of the aromatic extract recycling agent’s addition on the high-temperature performance of binders used in this study are compensated by Sasobit® WMA additive? (b) can recycling agent and WMA additive used in this study be utilized as supplementary materials to eliminate the negative effects of Sasobit® and RAB addition on the low-temperature performance? (c) How is the aging performance of different binders?

Hot and warm-mix asphalt binders with 30% and 50% RAB were prepared with an optimum recycling agent content, determined using the base binder’s low-temperature grade as a benchmark and high-temperature grade as a verification threshold. Binders were classified as unaged, RTFO-aged, or PAV-aged for testing. Performance was assessed across various temperatures: BBR (below 0 °C), LAS (20 °C), MSCR and frequency sweep (52–64 °C), and RV (110–165 °C). The results are summed up as follows:

-

Aging and RAB addition significantly increased binder viscosity, reflecting oxidative hardening and reduced workability, while the WMA additive alone decreased viscosity by approximately 20% and improved aging resistance. Incorporation of RAB reduced FAE values, especially at 50% contents, indicating lower thermal stability but lower compaction difficulty. The recycling agent (RA) proved critical such that it reduced viscosity by 30–70% across temperatures and aging states, particularly in WMA–RAB blends, and lowered FAE by 10–25%, thereby restoring workability and compaction feasibility without fully sacrificing thermal stability. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that while WMA enhances long-term stability and RA improves constructability, their combined use provides a synergistic effect that offsets the stiffening of high-RAB binders and ensures workable yet durable asphalt mixtures.

-

The incorporation of RAB and WMA reduced Jnr and increased recovery (R), confirming synergistic improvements in rutting resistance, with WMA–RAB binders (e.g., W50, Jnr=0.85) markedly outperforming the base binder (Jnr=9.50). Short-term aging amplified these benefits, while long-term aging narrowed differences, though WMA binders consistently retained approximately 10–20% better resistance than conventional binders. The recycling agent (RA), however, softened the binders, raising Jnr by 30–190% and lowering recovery, particularly in 50% RAB blends (PW50R Jnr=0.54, R = 24.8% vs. PW50 Jnr=0.21, R = 48.5%). These results highlight a clear trade-off such that RA compromises rutting resistance but remains essential for workability (as shown by viscosity and FAE), while WMA strengthens aging durability.

-

LAS test showed that RAB significantly reduced fatigue life, and aging further accelerated this decline. The WMA additive improved fatigue durability and slowed aging effects, though RAB still reduced performance in WMA blends. The recycling agent (RA) provided the strongest benefit such that in WMA–RAB binders, RA increased fatigue life by 70–270%, with 50% RAB + RA binders (e.g., Nf of PW50R = 378,000) surpassing even the neat WMA binder. These results confirm that RA restores ductility and molecular mobility, offsetting RAB brittleness, and while MSCR results showed this comes at the expense of rutting resistance, the LAS test highlights its critical role in extending binder fatigue life, particularly in high-RAB WMA mixtures.

-

BBR test results showed that the base binder graded PG XX–28, but RAB incorporation accelerated embrittlement, lowering grades to PG XX–22 (O30) and PG XX–16 (O50), with aging further reducing performance to PG XX–10. The WMA additive alone also deteriorated low-temperature flexibility (WB = PG XX–22), though its negative effect was less pronounced in high-RAB blends. The recycling agent (RA) proved essential: it consistently restored PG grades by one to two levels (e.g., W30 = PG XX–16 vs. W30R = PG XX–22; O50 = PG XX–16 vs. O50R = PG XX–28), and even under PAV aging, RA-treated binders outperformed their counterparts by at least one grade. These results confirm that while WMA enhances workability and rutting resistance at the expense of cracking resistance, RA mitigates this drawback, restoring flexibility and aligning with the fatigue durability improvements observed in LAS test results.

Overall, the benefits regarding the use of recycling agent in combination with WMA additive outweigh their disadvantages; so, the utilization of the recycling agent in warm-mix asphalt pavements containing RAP materials is recommended, especially their great resistance against aging highlights the incentive toward its utilization.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- BBR:

-

Bending beam rheometer

- CAM:

-

Christensen–Anderson–Marasteanu

- DL:

-

Double logistic

- DSR:

-

Dynamic shear rheometer

- FAE:

-

Flow activation energy

- FS:

-

Frequency sweep

- HMA:

-

Hot mix asphalt

- LAS:

-

Linear amplitude sweep

- MSCR:

-

Multiple stress creep recovery

- PAV:

-

Pressure aging vessel

- RA:

-

Recycling agent

- RAB:

-

Reclaimed asphalt binder

- RAP:

-

Recycled asphalt pavement

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- RTFO:

-

Rolling thin film oven

- RV:

-

Rotational viscosity

- SBR:

-

Styrene-butadiene rubber

- UV:

-

Ultraviolet

- WCO:

-

Waste cooking oil

- WMA:

-

Warm mix asphalt/additive

References

Kamboozia, N., Saed, S. A. & Rad, S. M. Rheological behavior of asphalt binders and fatigue resistance of SMA mixtures modified with nano-silica containing RAP materials under the effect of mixture conditioning. Constr. Build. Mater. 303, 124433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124433 (2021).

Mirwald, J., Nura, D., Eberhardsteiner, L. & Hofko, B. Impact of UV–Vis light on the oxidation of bitumen in correlation to solar spectral irradiance data. Constr. Build. Mater. 316 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125816 (2022).

Kamboozia, N., Rad, S. M. & Saed, S. A. Laboratory investigation of the effect of Nano-ZnO on the fracture and rutting resistance of porous asphalt mixture under the aging condition and Freeze–Thaw cycle. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 34, 04022052. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0004187 (2022).

Saed, S. A., Kamboozia, N., Ziari, H. & Hofko, B. Experimental assessment and modeling of fracture and fatigue resistance of aged stone matrix asphalt (SMA) mixtures containing RAP materials and warm-mix additive using ANFIS method. Mater. Struct. 54, 225. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-021-01812-9 (2021).

Dehaghi, E. A., Saed, S. A., Tahami, S. A., Solatifar, N. & Taghipoor, M. Using waste cigarette butt fibers as asphalt binder stabilizer in stone matrix asphalt: mechanical and environmental characterization. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 36 https://doi.org/10.1061/JMCEE7.MTENG-17251 (2024).

Karimi, M. M., Dehaghi, E. A. & Behnood, A. Cracking features of asphalt mixtures under induced heating-healing. Constr. Build. Mater. 324 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126625 (2022).

Kamali, Z., Karimi, M. M., Dehaghi, E. A. & Jahanbakhsh, H. Using electromagnetic radiation for producing reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) mixtures: Mechanical, induced heating, and sustainability assessments. Constr. Build. Mater. 321 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126315 (2022).

Saed, S. A., Kamboozia, N. & Mousavi Rad, S. Performance evaluation of stone matrix asphalt mixtures and low-temperature properties of asphalt binders containing reclaimed asphalt pavement materials modified with Nanosilica. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 34, 04021380. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0004016 (2022).

Mousavi Rad, S., Kamboozia, N., Anupam, K. & Saed, S. A. Experimental evaluation of the fatigue performance and self-healing behavior of nanomodified porous asphalt mixtures containing RAP materials under the aging condition and freeze–thaw cycle. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 34, 04022323. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0004488 (2022).

Sun, Y., Wang, W. & Chen, J. Investigating impacts of warm-mix asphalt technologies and high reclaimed asphalt pavement binder content on rutting and fatigue performance of asphalt binder through MSCR and LAS tests. J. Clean. Prod. 219, 879–893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.131 (2019).

Zhang, Y. & Bahia, H. U. Effects of recycling agents (RAs) on rutting resistance and moisture susceptibility of mixtures with high RAP/RAS content. Constr. Build. Mater. 121369 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121369 (2020).

Sabouri, M. Evaluation of performance-based mix design for asphalt mixtures containing reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP). Constr. Build. Mater. 235 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117545 (2020).

Zhou, Z., Gu, X., Dong, Q., Ni, F. & Jiang, Y. Rutting and fatigue cracking performance of SBS-RAP blended binders with a rejuvenator. Constr. Build. Mater. 203, 294–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.01.119 (2019).

Mullapudi, R. S., Noojilla, A., Reddy, K. S. & S. L. & Fatigue and healing characteristics of RAP mixtures. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 32 https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0003484 (2020).

Hajj, E. Y., Sebaaly, P. E. & Shrestha, R. Laboratory evaluation of mixes containing recycled asphalt pavement (RAP). Road. Mater. Pavement Des. 10, 495–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680629.2009.9690211 (2009).

Pasetto, M. & Baldo, N. Fatigue performance of recycled hot mix asphalt: a laboratory study. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 4397957 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4397957 (2017).

Daryaee, D., Ameri, M. & Mansourkhaki, A. Utilizing of waste polymer modified bitumen in combination with rejuvenator in high reclaimed asphalt pavement mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 235 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117516 (2020).

Kie Badroodi, S., Reza Keymanesh, M. & Shafabakhsh, G. Experimental investigation of the fatigue phenomenon in nano silica-modified warm mix asphalt containing recycled asphalt considering self-healing behavior. Constr. Build. Mater. 246 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117558 (2020).

Behnood, A. Application of rejuvenators to improve the rheological and mechanical properties of asphalt binders and mixtures: a review. J. Clean. Prod. 231, 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.209 (2019).

Saed, S. A. et al. Full range I/II fracture behavior of asphalt mixtures containing RAP and rejuvenating agent using two different 3-point Bend type configurations. Constr. Build. Mater. 314 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125590 (2022).

Ahmed, R. B. & Hossain, K. Waste cooking oil as an asphalt rejuvenator: a state-of-the-art review. Constr. Build. Mater. 230 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.116985 (2020).

Ziari, H., Aliha, M., Moniri, A. & Saghafi, Y. Crack resistance of hot mix asphalt containing different percentages of reclaimed asphalt pavement and glass fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 230 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117015 (2020).

Singh, D., Girimath, S. & Ashish, P. K. Performance evaluation of polymer-modified binder containing reclaimed asphalt pavement using multiple stress creep recovery and linear amplitude sweep tests. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 30 https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0002176 (2018).

Roja, K. L., Masad, E. & Mogawer, W. Performance and blending evaluation of asphalt mixtures containing reclaimed asphalt pavement. Road. Mater. Pavement Des. 1–17 https://doi.org/10.1080/14680629.2020.1764858 (2020).

Gungat, L., Yusoff, N. I. M. & Hamzah, M. O. Effects of RH-WMA additive on rheological properties of high amount reclaimed asphalt binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 114, 665–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.03.182 (2016).

Zhou, Z., Gu, X., Jiang, J., Ni, F. & Jiang, Y. Nonrecoverable behavior of polymer modified and reclaimed asphalt pavement modified binder under different multiple stress creep recovery tests. Transp. Res. Rec. 2672, 324–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361198118782029 (2018).

Yu, S., Shen, S., Zhang, C., Zhang, W. & Jia, X. Evaluation of the blending effectiveness of reclaimed asphalt pavement binder. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 29 https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0002095 (2017).

Behnood, A. A review of the warm mix asphalt (WMA) technologies: effects on thermo-mechanical and rheological properties. J. Clean. Prod. 120817 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120817 (2020).

Guo, M. et al. Effect of WMA-RAP technology on pavement performance of asphalt mixture: a state-of-the-art review. J. Clean. Prod. 121704 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121704 (2020).

Ayazi, M. J., Moniri, A. & Barghabany, P. Moisture susceptibility of warm mixed-reclaimed asphalt pavement containing Sasobit and zycotherm additives. Pet. Sci. Technol. 35, 890–895. https://doi.org/10.1080/10916466.2017.1290655 (2017).

Saleh, M. & Nguyen, N. H. Effect of rejuvenator and mixing methods on behaviour of warm mix asphalt containing high RAP content. Constr. Build. Mater. 197, 792–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.205 (2019).

Ziari, H., Moniri, A., Bahri, P. & Saghafi, Y. The effect of rejuvenators on the aging resistance of recycled asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 224, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.06.181 (2019).

Farooq, M. A., Mir, M. S. & Sharma, A. Laboratory study on use of RAP in WMA pavements using rejuvenator. Constr. Build. Mater. 168, 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.02.079 (2018).

Zhang, R. et al. The impact of bio-oil as rejuvenator for aged asphalt binder. Constr. Build. Mater. 196, 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.10.168 (2019).

Afridi, H. F. et al. Utilizing waste engine oil and Sasobit to improve the rheological and physiochemical properties of RAP. Discov. Civil Eng. 1, 131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44290-024-00114-7 (2024).

Zhao, X. et al. Effect of Sasobit/Waste cooking oil composite on the Physical, Rheological, and aging properties of Styrene–Butadiene rubber (SBR)-Modified bitumen binders. Materials 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16237368 (2023).

Al-Saffar, Z. H. et al. A review on the durability of recycled asphalt mixtures embraced with rejuvenators. Sustainability 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168970 (2021).

Eltwati, A. et al. Effect of warm mix asphalt (WMA) antistripping agent on performance of waste engine Oil-Rejuvenated asphalt binders and mixtures. Sustainability 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043807 (2023).

Institute, A. MS-2 Asphalt Mix Design Methods 7th edition (Asphalt Institute, 2015).

Sedaghat, B., Taherrian, R., Hosseini, S. A. & Mousavi, S. M. Rheological properties of bitumen containing nanoclay and organic warm-mix asphalt additives. Constr. Build. Mater. 243 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118092 (2020).

Pirmohammad, S. & Khanpour, M. Fracture strength of warm mix asphalt concretes modified with crumb rubber subjected to variable temperatures. Road. Mater. Pavement Des. 1–19 https://doi.org/10.1080/14680629.2020.1724819 (2020).

Behnood, A., Karimi, M. M. & Cheraghian, G. Coupled effects of warm mix asphalt (WMA) additives and rheological modifiers on the properties of asphalt binders. Clean. Eng. Technol. 100028 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clet.2020.100028 (2020).

Xu, J., Yang, E., Luo, H. & Ding, H. Effects of warm mix additives on the thermal stress and ductile resistance of asphalt binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 238 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117746 (2020).

Shen, J., Amirkhanian, S. & Tang, B. Effects of rejuvenator on performance-based properties of rejuvenated asphalt binder and mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 21, 958–964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2006.03.006 (2007).

Zaumanis, M., Mallick, R. B. & Frank, R. Determining optimum rejuvenator dose for asphalt recycling based on superpave performance grade specifications. Constr. Build. Mater. 69, 159–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.07.035 (2014).

Arámbula-Mercado, E., Kaseer, F., Martin, E., Yin, A. & Garcia Cucalon, L. Evaluation of recycling agent dosage selection and incorporation methods for asphalt mixtures with high RAP and RAS contents. Constr. Build. Mater. 158, 432–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.10.024 (2018).

Gao, J. et al. High-temperature rheological behavior and fatigue performance of lignin modified asphalt binder. Constr. Build. Mater. 230 https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings14081038 (2020).

Arrhenius, S. Über die reaktionsgeschwindigkeit Bei der inversion von Rohrzucker durch Säuren. Z. für Phys. Chem. 4, 226–248. https://doi.org/10.1515/zpch-1889-0416 (1889).

Zhang, H., Chen, Z., Xu, G. & Shi, C. Evaluation of aging behaviors of asphalt binders through different rheological indices. Fuel 221, 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2018.02.087 (2018).

Yusoff, N. I. M., Shaw, M. T. & Airey, G. D. Modelling the linear viscoelastic rheological properties of bituminous binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 25, 2171–2189 (2011).

Asgharzadeh, S. M., Tabatabaee, N., Naderi, K. & Partl, M. N. Evaluation of rheological master curve models for bituminous binders. Mater. Struct. 48, 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-013-0191-5 (2015).

Jamshidi, A., Hamzah, M. O. & You, Z. Performance of warm mix asphalt containing Sasobit®: State-of-the-art. Constr. Build. Mater. 38, 530–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.08.015 (2013).

Rubio, M. C., Martínez, G., Baena, L. & Moreno, F. Warm mix asphalt: an overview. J. Clean. Prod. 24, 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.11.053 (2012).

Zhao, G. & Guo, P. Workability of Sasobit warm mixture asphalt. Energy Procedia. 16, 1230–1236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2012.01.196 (2012).

Li, Z., Lu, Z., Liu, X. & Wang, J. Investigating the synergistic anti-aging effects of Sasobit and recycled engine oil in styrene-butadiene rubber modified asphalt. Front. Mater. 11–2024 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2024.1412094 (2024).

Harooni Jamaloei, M., Aboutalebi Esfahani, M. & Filvan Torkaman, M. Rheological and mechanical properties of bitumen modified with Sasobit, polyethylene, paraffin, and their mixture. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 31, 04019119. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0002664 (2019).

Liu, H. et al. Analysis of OMMT strengthened UV aging-resistance of Sasobit/SBS modified asphalt: its preparation, characterization and mechanism. J. Clean. Prod. 315 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128139 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed equally to the writing of this research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saed, S.A., Ziari, H., Kamboozia, N. et al. Rheological and aging performance of reclaimed asphalt binders modified by warm mix additive and recycling agent. Sci Rep 15, 44697 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28339-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28339-1