Abstract

Smooth cross-section and consistent stubble height are of importance for retained stalk quality of leek. The commonly-used cutting tools are prone to suffer from severe friction due to their high-speed rotation on the rough field ground. Surely, the high-speed rotation results in not only violent worn on the blade tip but also uneven cross-section and inconsistent stubble height. This study proposed to develop an innovative modular cutting tool based on the indexable mechanism in mechanical engineering for either improving the retained stalk quality or prolonging the tool life. Firstly, the discrete element model for the leek stalk was calibrated using shear tests, with a minimal relative error of 0.36% observed for the peak cutting force. The coupled DEM-MBD simulation method was employed to analyze interaction forces and failure forms of the leek stalks during the cutting process, optimizing blade angle of the modular cutting tool. The optimized modular cutting tool reduced peak force compared with the conventional rotary tool and unoptimized modular cutting tool (by 34% and 16%, respectively). Results of the bench test show that the optimized modular cutting tool reduced tip breakage rate and incomplete cutting rate of retained stalks by 75% and 50%, respectively, but increased the oblique cutting rate by 33% relative to the conventional rotary tool. Additionally, the corrected smoothness index (\(Ra_{c}\)) of cross-section was improved by 53.95%. These results highlight the potential of the modular cutting tool to improve harvesting efficiency and stalk quality in field applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leek is one of the most widely cultivated crops in China, accounting for 5–6% of the total vegetable field area annually1. As a perennial herbaceous plant, leek can be harvested 4–5 times per year2. At maturity, leek typically reaches a height of 20–50 cm and consists primarily of stalk, leaves, and root system. The stalk, measuring 3–6 cm in length and 3–5 mm in diameter, not only serves as the structural link between the leaves and root system3 but also functions as the primary cutting and load-bearing section during harvest. The standard harvesting method involves radial cutting of the stalk close to the base while preserving a stubble—referred to as the retained stalk—to facilitate regrowth in subsequent cycles. The quality of the retained stalk, including a smooth cross-section and consistent stubble height, is a prerequisite for the subsequent growth of leek4,5.

Manual sickle cutting is extensively applied in leek harvesting, particularly in small- to medium-sized vegetable farms6. Like harvesting many other vegetables manually, this method is labor-intensive and time-consuming, resulting in significant labor costs. Moreover, to promote the consistent subsequent growth, farmers opt for soil-level cutting, abandoning the retained stalks5,6. As a result, the growth cycle is significantly extended, leading to a decline in overall harvesting efficiency.

Development of a cutting tool for leeks has been occasionally reported. Chatopadhyay et al.7 developed a throwing-style cutting tool, Jian-Guo Ma et al.8 developed a scythe-style cutting tool, Ⅴadivel R et al.9 developed a reciprocating cutting tool, and Xin-Bing Xu et al.10 developed a disc-style cutting tool. However, a major technical challenge in these cutting tools for leeks is the violent interaction between soil and tool, which is due to the tool very close to the ground because of low properties of the leek. The violent interaction not only reduces leek quality but also shorten tool life. It is worth noting that the disc-style cutting tool shows more excellent performances than the other tools, but severe worn lands are often observed.

In the field of mechanical manufacturing, indexable inserts are widely used in metal removal applications due to their replaceable inserts, high wear resistance, and adaptability11. It has been reported that indexable tools offer enhanced productivity over solid tools, particularly in terms of improving workpiece quality, reducing burr formation, and better managing tool wear12. Koshy et al.13 noted that, in contrast, solid carbide drill bits tend to show higher tool wear and poorer surface finish under the same parameters. Okada et al.14 confirmed that, when cutting stainless steel, titanium alloys, nickel-based alloys, and carbon steel, indexable drill bits exhibit better wear resistance than solid drill bits without compromising cutting quality. Ehsan et al.15 found that, compared to solid carbide drill bits, using indexable tools for machining glass fiber reinforced plastics can improve machining accuracy, reduce cutting temperatures, and minimize tool wear. So far, the application of indexable inserts in harvesting leeks has not been reported. Therefore, this study proposes the design of innovative modular cutting tool based on indexable mechanism to improve the quality of retained stalks of leek and reduce tool wear.

In previous research, statistical and tracer methods were used to investigate interaction, cutting mechanisms and working condition optimization between plant and machinery16. These methods are not only time-consuming and laborious, but also difficult to observe the microscopic damage mechanism of plants. The discrete element method (DEM), a numerical technique that simulates the dynamic behavior of discrete particle17, has been extensively utilized to simulate the interaction between plants and machines. Guo et al.18 established a discrete element model for banana stems based on their mechanical parameters of shear, tension, compression and bending, and conducted an analysis of the microscopic visualization behavior of banana stems. Shi et al.19 conducted calibration of the discrete element model of wheat straw in both vertical and circumferential directions through stretching, compression, shearing and bending experiments. Li et al.20 established the damage model and movement model of Pennisetum stalk separately using cyclic contact separation tests to investigate cutting mechanism of Pennisetum stalk. However, few studies on vegetables like leek stalk have been conducted. In addition, unlike other types of stalks, the multilayer structure and the unique growth pattern of fibers in leek stalk introduce challenges in establishing its discrete element model.

The DEM-MBD coupling method is widely used in many fields, and particularly in the engineering field. So far there are few combined DEM and MBD studies in the cutting tool for the leeks, although the applications of this method in agriculture have been occasionally reported.

In summary, this study proposes a novel modular cutting tool designed to address the challenges of leek harvesting. A DEM-MBD coupled simulation is used to investigate the cutting mechanics of modular cutting tool under compound rotary–linear motion on leek stalks and optimize the blade structure. The reliability of the modular cutting tool cutting results was validated through bench experiments, and a comparative analysis was carried out against the conventional rotary tool21. The research objectives include:

-

1.

Develop a discrete element model of the leek stalk based on the Hertz-Mindlin with bonding theory and calibrate parameters and fracture characteristics through shear bench experiments.

-

2.

Use DEM-MBD coupled simulation to reveal the mechanics of tool–leek stalk interaction, and investigate cutting force distribution and fracture mode evolution under varying blade angles.

-

3.

Based on simulation results, the blade angle of the modular cutting tool was optimized to reduce cutting force and cross-section roughness. Bench tests were conducted to validate its effectiveness and to compare the retained stalks quality of the modular cutting tool with the conventional rotary tool21.

This study provides theoretical support and equipment reference for mechanized leek harvesting, while also contributing to the fundamental understanding of cutting mechanism in flexible crops.

Materials and methods

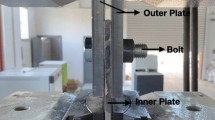

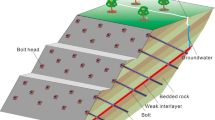

Original structure of the modular cutting tool

The modular cutting tool consists of a high-hardness replaceable blade, a wear-resistant U-shaped frame, and multiple fastening screws (Fig. 1a). The design basis for the cutting blade in Fig. 1 is inspired by the structure of the modular turning tool in mechanical engineering. During harvesting, the blade tip maintains a specified clearance above the ground to prevent direct soil-contact (Fig. 1b). As depicted in Fig. 1c, the modular cutting tool performs a compound rotary–linear motion, integrating rotation around the central axis with linear movement along the radial direction of the leek stalk. This combined motion enables the blade to cut the stalk at an oblique angle, generating simultaneous shearing and compressive stresses that reduce the peak cutting force relative to purely perpendicular cutting. The U-shaped frame serves as both a guide and a stabilizer, regulating the cutting depth and preserving the optimal attack angle of the blade throughout operation. The wear-resistant protrusion of the frame maintains a stable clearance between the blade tip and the soil, thereby minimizing abrasion and ensuring consistent cutting performance. Consequently, the frame is manufactured from highly wear-resistant material, while the blade material is selected for its high hardness to ensure tip sharpness and service life. The material properties and specifications of the modular cutting tool are listed in Table 1.

Test material

Fresh leek (JC791 variety) specimens were obtained from the Kunjian Leek Planting Base, Feidong County, Anhui Province, China (117.840741°E, 32.062738°N). A total of 200 healthy, pest-free plants with upright leaves were selected for the experiments. Immediately after harvest, adhering soil and surface debris were removed using distilled water. The cleaned samples were stored in a temperature-controlled incubator at 24 °C to minimize moisture loss. During transport, the samples were placed in an insulated container maintained at 24 °C and 50% relative humidity to preserve their structural integrity. All specimens underwent cutting and mechanical testing within 24h of harvest.

The stalk of leek represents the cutting region during the harvesting process. Physical properties were measured including stalk diameter, height, density, and moisture content.

Moisture content was determined prior to mechanical testing using the constant-temperature oven-drying method in accordance with ASABE Standard S358.2 (2008) (Fig. 2). Other physical parameters were measured using a high-precision electronic balance (accuracy: 0.01 g) and a digital vernier caliper (accuracy: 0.01 mm).

Mechanical properties—tensile strength, shear strength, elastic modulus, and Poisson’s ratio—were determined using a STD-100 electronic universal testing machine (Lugong Precision Instruments Co., Ltd., China), equipped with a mechanical sensor (capacity: 100 N, accuracy: 0.01 N), as shown in Fig. 2. Microscopic examination revealed that the stalk of leek consists of a double-layered epidermal layer (EL) enclosing symmetrical inner parenchyma (IP) on both sides. To accurately determine the mechanical parameters, both the EL and IP were subjected to tensile and compressive tests. The measured values are presented in Table 2.

Theoretical cutting model

Cutting force is a critical mechanical parameter for evaluating the quality and efficiency of stalk-severing operations. Lower and more stable cutting forces generally correspond to improved cross-sectional integrity, reduced blade wear, and lower energy consumption during harvesting22,23. Currently, most leek harvesters adopt a clamping-based cutting mechanism, in which the upper portion of the stalk (i.e., the leaves) is held by a flexible clamping conveyor system. This system synchronously performs pre-cut clamping, the cutting operation, and post-cut conveying8,10,22.

Clamping-assisted cutting stabilizes the stalk, reducing cutting force and energy use while improving precision and minimizing crop damage2. Therefore, in this study, the cutting process is specifically investigated under clamped conditions to reflect the actual operational configuration of leek harvesters.

Within this mechanical context, the leek stalk can be modeled as a flexible slender cylindrical beam with both ends constrained. Figure 3 illustrates the relative spatial relationship between the leek stalk and the cutting blade under a cartesian coordinate system during clamping-assisted cutting. The cutting blade rotates around its own axis (Z-axis) with an angular velocity of w and advances along the X-axis with a linear velocity v. The blade has a diameter of \(D_{0}\). For simplification, the blade center is set as the coordinate system origin. Because the Z-directional force component has negligible influence on cutting performance, it is excluded from the dominant force analysis22.

During the severing process, the total cutting force \(F_{cut}\) is composed primarily of two components: the compressive deformation force along the X-axis (\(F_{n}\)) and the shear force along the Y-axis (\(F_{t}\)). \(F_{cut}\) can be expressed as:

The compressive deformation force \(F_{n}\) (N) originates from the axial feeding pressure and blade impact, and is defined as:

where p denotes the compressive stress (N/mm2), and \(A_{c}\) is the blade–stalk contact area (mm2). The contact area is estimated as:

Here, k is a proportional coefficient, \(D_{0}\) is the blade diameter (mm), and d is the cutting depth (mm).

The shear force \(F_{t}\) (N) arises from frictional interaction between the blade and the base of the leek stalk. It is given by:

where \(\tau\) is the material shear strength (N/mm2), and \(A_{s}\) represents the shear area (mm2). Depending on the blade–stalk geometric relationship, \(A_{s}\) can be defined as:

Equations (1)–(5) indicate that \(F_{n}\) increases linearly with \(D_{0}\), while \(F_{t}\) exhibits nonlinear growth due to variations in shear area geometry. Theoretically, the diameter of the modular cutting tool should be reduced to decrease the cutting force. However, excessively small blade diameters may increase uncut stalks rates, especially when the inter-row spacing is 25–30 cm and the row width is approximately 5 cm1,5. The initial geometric parameters of the modular cutting tool are.

summarized in Table 3.

DEM model

Based on the physical parameters listed in Table 2 and the structural growth characteristics of leek stalks, a particle-based solid model was constructed using SolidWorks software (Dassault Systèmes, France). The coordinates of each particle’s center were calculated and imported into EDEM software (Altair, USA) via Microsoft Excel. The EL and IP were modeled using spherical particles with diameters of 0.5 mm and 0.45 mm, respectively. The model consisted of 4,500 spherical particles: 2,700 particles (\(\varphi_{p}\) = 0.5 mm) forming two concentric EL layers (EL1 and EL2), and 1,800 particles (\(\varphi_{p}\) = 0.45 mm) forming two symmetrical IP structures. The resulting assembly formed a cylindrical DEM structure with a diameter of 5.5 mm and a length of 26 mm, as illustrated in Fig. 4a.

The Hertz-Mindlin (no-slip) model and the Hertz-Mindlin with Bonding model were employed to simulate the contact and bonding forces between particles, respectively. To obtain a discrete element model that accurately represents cutting behavior, the shear failure force was identified as a key parameter for evaluating shear performance18. Simulated cutting force tests were conducted using the same geometry, with a cutting speed of 500 mm/min (Fig. 4d), in alignment with the bench-scale experimental tests (Fig. 4c). The bonding parameters were iteratively adjusted until the simulated shear failure force achieved a discrepancy of less than 5% compared to the experimental results. The model’s bonding parameters are summarized in Table 4.

From the deformation perspective during the cutting process, both the leek sample (Fig. 4e) and the leek model (Fig. 4f) underwent compression, tension, bending, and rupture. Initially, compression deformation occurred at the point of contact with the cutter tip. As the cutter tip moved downward, both ends of the sample began to lift, and the bottom experienced tension due to compression at the ends. The stress in the tensile region continued to increase until it exceeded the material’s allowable stress, finally leading to rupture. Based on the force–displacement curve during the cutting process, as shown in Fig. 4b, the curve initially exhibited a slow rise, followed by a rapid increase, and then a sharp decline after the stalk ruptured. The experimental shear failure force was 27.82 N, while the simulated shear failure force was 27.72 N, with an error of 0.36%. These results confirm that the DEM model accurately simulates the shear characteristics of the leek stalk.

MBD model

The cutting motion of the modular cutting tool combines self-rotation with forward translation. A simplified model was built in SolidWorks, retaining the frame, blade, fixing screws, and central bolt, and imported into Adams (MSC Software, USA). A rotary joint was added between the frame and central bolt, and a translational joint between the central bolt and ground. Fixed joints were used to connect the frame, blade and fixing screws. Motion drivers were applied to the rotary and translational joints, and GForce drives were assigned to each part. The model was exported as an .adm file and co-simulated with EDEM via the Adams Co-Simulation Plugin. The MBD model of the modular cutting tool is shown in Fig. 5.

DEM-MBD based simulation parameter settings

In the EDEM software, the centroid of the leek stalk DEM model was placed at the origin, with the axial direction aligned along the Z-axis. To simulate field clamping and cutting conditions, particles at both cross-sections of the DEM model along the Z-axis were fixed. Based on typical field operating conditions for agricultural machinery, the cutting tool’s rotational speed was set to 300 rpm, and the forward velocity was set to 0.3 m/s24. With all other parameters held constant, MBD models of the modular cutting tool were constructed for blade edge angles of 10°, 15°, 20°, 25°, 30°, 35°, 40°, 45°, 50°, 55°, 60°, 65°, 70°, and 75°. The ranges of the simulation parameters were determined by the combination of the low properties of the leek and the geometry of the disc-style cutting tool in this study. Co-simulation of single stalk clamping and cutting was then performed for each configuration. Additionally, a conventional rotary tool model21 was established to compare the cutting force and the cross-section quality.

Bench testing

To verify the reliability of the blade, a bench test was conducted (Fig. 6). The tool is mounted on parallel slides, with the forward movement synchronized by a motor connection and the rotational movement achieved by a motor connection to the center of the tool. Both the rotational speed (300rpm) and the forward speed (0.3m/s) are controlled by an STM32 microcontroller, matching the simulation parameters outlined previously.

A stereo microscope (SZ810, CNOPTEC, China) was employed to observe the cross-section morphology of retained stalks, as shown in Fig. 7a. To evaluate the macroscopic cutting performance, three failure probabilities were defined as key metrics: tip breakage rate (H₁), incomplete cutting rate (H₂), and oblique cutting rate (H₃). These failure modes represent common defects observed at the stalk cross-section and are illustrated in Fig. 7b.

In this study, digital image processing (DIP) was used to quantitatively evaluate the smooth cross section shown in Fig. 7b. The focal length of the stereo microscope was fixed to ensure that all captured images were clear and had consistent pixel resolution. The retained stalk was placed horizontally on a flat stage plate, with its axial direction aligned parallel to the Y-axis. The extraction steps for the cross-section contour are shown in Fig. 8. First, the original RGB image was cropped using Adobe Photoshop 2025 (Adobe Systems, USA) to obtain a clear cross-sectional image. Then, Gaussian filtering (σ = 5) was applied in PyCharm 2022.1 (JetBrains, Czech Republic) to reduce high-frequency noise while preserving edge features. The image was then processed by color space conversion, region segmentation, and morphological enhancement. Finally, a column-wise scanline method was used to extract the topmost non-zero edge pixel in each column, forming the cross-section contour. The cross-section roughness was calculated based on the arithmetic mean deviation, following GB/T 3505–2000, as shown in Eq. (6):

where Ra denotes the arithmetic average roughness (µm), L is the evaluation length (µm), and y(x) represents the height deviation at position x.

To maintain consistent pixel ratio during imaging, this study used microscopic images of the leek cross-section captured from the lateral view of the cutting interface. By extracting the pixel coordinates of the upper profile curve, cross-section roughness could be quantified. Accordingly, Eq. (7) was adapted to the following discrete form:

where \(Ra_{c}\) is the modified roughness used in this study (µm), X is the total number of pixels along the cross-sectional profile, yi is the height value at the ith pixel, and a is the mean profile height, calculated as:

Randomly select 30 stalks samples from the sets of smooth cutting end face results for both the conventional rotary tool and the modular cutting tool models for analysis. The calculated \(Ra_{c}\) values were used for the quantitative comparison between the conventional rotary tool and the modular cutting tool.

Results and discussion

MBD–DEM based simulations

Flexible plant cutting by rigid blades represents a typical rigid–flexible impact scenario involving multi-modal coupled deformation25. As shown in Fig. 9a, the DEM-based flexible stalk model undergoes bending-compression-cutting-torsion synergistic deformation under combined rotational and translational loads. To all appearances, the dynamic response of the stalk is evidently nonlinear. Stress waves initiated by the cutting disturbance propagate from the contact zone along the stalk, and the resulting deformation aligns closely with findings by Qiu et al.22.

A key finding from the simulation was the stark contrast between the conventional rotary tool and the modular cutting tool in terms of stalk deformation and fracture behaviors (Fig. 9a). Under the modular cutting tool, the stalk experiences bending and Z-axis torsion as the blade penetrates. Compressive stress concentrates around the blade–stalk interface and both constrained ends (green regions in Fig. 9a), while tensile stress occurs on the opposing side. Fracture typically initiates at the blade contact zone. In contrast, the conventional rotary tool induces greater impact loading, resulting in more severe bending. At the two constrained ends, the part subjected to greater tensile stress fractures first. This is because the tensile stress reaches the material’s yield limit more quickly. Therefore, a more precise cutting position and better quality of the cutting end face require that cutting deformation should dominate the failure mode.

As shown in Fig. 9b, cutting processes exhibit a three-phase force–time profile: gradual increase, peak force, and sharp decline, corresponding to blade engagement, maximum resistance, and fracture. Notably, the conventional rotary tool generates a higher peak radial force but a lower tangential force than the modular cutting tool, indicating that impact energy dominates over shear cutting energy in the conventional rotary tool. Consequently, the conventional rotary tool relies more on compressive fracture, whereas the modular cutting tool facilitates more efficient shear-based cutting. These results indicate that in the process of achieving high-quality separation of flexible plant tissues, the shear cutting force seems to be more effective than the impact force.

The Adams postprocessor displayed the force–time curves obtained from the MBD-DEM coupled simulation under different blade angles of the modular cutting tool, as shown in Fig. 10. The force–time curves under different blade angles exhibited similar variation trends, reflecting the characteristic mechanical response of the leek stalk during high-speed rotational cutting. Specifically, all the curves displayed a consistent overall trend: the force gradually increased during the initial phase, followed by a rapid rise until reaching a peak at the moment of stalk fracture, after which the force decreased sharply once cutting was completed. Due to the complete constraint of both ends of the leek stalk, residual frictional contact between the retained stalk and the rotating cutter persisted, resulting in a residual force at the tail of the force–time curve. It can be clearly seen that significant differences were observed in the peak values and the time required to reach the peak, depending on the blade angle.

As shown in Fig. 11, in the radial direction, the force curve is more sensitive to the change in angle. As the blade angle increases from 10° to 75°, the radial peak force shows an upward trend. The radial peak force value gradually increases from 3.58N to 10.68N. During this process, the peak force in the tangential direction experienced a process of first decreasing and then stabilizing. When the blade angle is 10°, the peak force in the tangential direction is the maximum, with a value of 9.86N. Then, as the angle increases, the peak force in the tangential direction begins to decrease. When the blade angle is in the range of 25° to 55°, the peak force in the tangential direction stabilizes at around 8N. After 55°, the peak force in the tangential direction begins to fluctuate.

Overall, two force components exhibit nonlinear trends with increasing blade angle, indicating strong angle-dependent mechanical behavior. In the lower angle range (10°–15°), the radial force remained relatively low (less than 4 N), while the tangential force was elevated. This suggests that blades with smaller edge angles exhibit stronger cutting characteristics, accompanied by lower normal resistance. This condition implies a shear-dominated failure mechanism at the blade-stalk interface. As the blade angle increased from 20° to 55°, the radial force sharply increased, while the tangential force remained low and stable. During this phase, the failure mechanism transitioned from shear-dominated to compression-dominated. When the blade angle continued to increase, both radial and tangential forces showed unstable fluctuations, with the radial force exceeding the tangential force. This indicates a significant increase in the impact load on the stalk, which may exacerbate the retained stalk vibrations and cross-section uneven.

Figure 12 shows the images of the leek stalk discrete element model at the moment of fracture under each blade angle. In the 10°–20° angle range, some floating particles appear at the cross-section (highlighted in yellow box, accounting for 17.65% of the total sample). Corresponding to the results in Fig. 11, the tangential force is relatively high in this angle range. As the blade angle increases, the floating particles at the cross-section gradually disappear. At blade angles of 25° and 30°, the cross-sectional quality is optimal (shown in green box, accounting for 14.29% of the total sample). As the angle continues to increase, the radial force begins to rise steadily, while the tangential force stabilizes. At this point, the quality of the cross-section declines again, with the appearance of floating particles, particle detachment, and stress concentration (shown in blue box, accounting for 29.41% of the total sample). When the blade angle reaches 60° or higher, the cutting load exhibits noticeable fluctuations. From the cross-sectional view, significant burr formation is observed at the ends at 60° and 65° (indicated in red box, accounting for 14.29% of the total sample). At blade angles of 70° and 75° (indicated in red pointer, accounting for 14.29% of the total sample), cutting could not be completed, resulting in a performance similar to that of the conventional rotary tool, with the ends of the stalk reaching the material yield limit first. The fracture results from the discrete element model are highly consistent with the force–time curves. Furthermore, when the tangential force is excessive (as seen at 10°, 15°, and 20° in Fig. 11), the cutting performance is not optimal. The cross-section quality is best when the blade angle is between 25° and 30°. Therefore, the cutting performance is most effective when the tangential force is minimized and stabilizing, with the radial force at its lowest.

Comparative experiments

Based on the simulation results, the blade angle of 25° yielded the lowest resultant cutting force and the highest cross-section quality. A bench-top cutting comparison was conducted between the modular cutting tool with the optimized blade parameter and the conventional rotary tool. Both tools were tested at a feed velocity of 0.3 m/s and a rotational speed of 300 rpm. The relevant experimental setup is schematically illustrated in Fig. 6. The corresponding measurements are briefly depicted below: firstly, the leek is clamped into a holder; next, the cutting edge of the tool is adjusted as close to the leek stalk as possible (Fig. 6b); next, the tool is operated, by the STM32 microcontroller (Fig. 6d,f) to cut the aforementioned leek stalk, at the specified working conditions (such as feed speed and rotary speed); finally, the leek quality at the cross-section of the stalk is observed and evaluated with a stereo microscope (SZ810, CNOPTEC, China). Note that the same cutting tool is required cutting fifty leek stalks in order to evaluate either leek quality or tool validity.

The symbols H1, H2, and H3 denote tip breakage, incomplete cutting rate, and oblique cutting rate, respectively. The values in them are calculated by the observation and evaluation with a stereo microscope (SZ810, CNOPTEC, China) after fifty leak stalks are finished cutting by the same tool (see the test procedures of Section Comparative experiments). The cutting failure rates of the modular cutting tool and the conventional rotary tool are (6%, 24%) H1, (2%, 4%) H2, (8%, 6%) H2, respectively. The comparison of cutting failure rates between the conventional rotary tool and the modular cutting tool is presented on Fig. 13. The modular cutting tool significantly reduced H1 by 75% and H2 by 50% relative to the conventional rotary tool. This improvement can be attributed to the optimized blade angle (25°), which minimized excessive compressive stress and shear-induced tearing at the stalk tip, thereby enhancing cross-section integrity. While the H3 value of the modular cutting tool was 33% higher than that of the conventional rotary tool, which was mainly attributed to post-fracture stalk rebound and blade–stalk interaction. These findings suggest that modular cutting tool effectively mitigates structural damage and improves cross-section quality, meeting the operational requirements for high-efficiency harvesting of flexible crops such as leek. Furthermore, the reduction in tip breakage implies less mechanical stress concentration at the cutting edge, which may also prolong tool life and reduce maintenance frequency.

The results of the Micro metric are shown in Table 5. The calculation of the relative cross-section roughness indicates that the average \(Ra_{c}\) value for modular cutting tool is 2.78, representing a 53.9% improvement over the conventional rotary tool value of 6.03. Additionally, the standard deviation of \(Ra_{c}\) is smaller when using modular cutting tool, suggesting less variation in roughness. Therefore, the modular cutting tool not only performs better in terms of average roughness but also exhibits superior consistency in cutting quality compared to the conventional rotary tool.

Conclusions

Leek is very popular around China due to its highly nutrition. However, the existing cutting tools for leeks are prone to either result in poor quality or shorten the tool life. Therefore, it is essential to investigate an alternative tool for improving the leek quality and prolonging tool life. Inspired by the modular turning tool in mechanical manufacturing, we have proposed to investigate an innovative modular tool for cutting the leeks. This design methodology is the novel character of this study, as stated in the Introduction section.

Validation of the developed cutting tool has been implemented by comparing with the commonly-used tools and the past experimental measurements, respectively. The comparisons of this study have shown that the obtained modular tool is able to reduce both 75% of the tip breakage rate and 50% of the incomplete cutting rate of the tool, respectively. Meanwhile, the smoothness index (Rac) of the cross-section of the leek can be improved by 53.95%. The demonstration case studies indicate the validity of the modular cutting tool for the leeks. To enhance the overall tool validity, the future work will attempt to implement as many field trials as possible to refine the tool geometry.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request from Prof. Lin Zhu at zl009@mail.ustc.edu.cn.

References

Gao, L., Yuan, Y. W., Yi, J. G. & Kong, D. G. Revised design and experiment on small leek harvester. Food Mach. 32, 117–119. https://doi.org/10.13652/j.issn.1003-5788.2016.04.028 (2016).

Gong, Y. J. et al. Research status and development trends of Chinese chive harvesting machinery. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 40, 262–268. https://doi.org/10.13427/j.cnki.njyi.2018.10.051 (2018).

Xun, G. S., Wang, J. S. & Zhang, J. X. Experimental study on geometric and mechanical properties of Allium tuberosum at harvesting maturity. Agric. Eng. 10, 94–97. https://doi.org/10.13427/j.cnki.njyi.2018.10.051 (2020).

Chen, T. L. The Development of the Leek Harvester. (Master’s thesis) Hebei Agricultural University, China (In Chinese) (2016).

Cui, L. Y. Brief analysis of full-process mechanized technology for Chinese chive cultivation. Agric. Henan 15, 68–69. https://doi.org/10.15904/j.cnki.hnny.2024.15.043 (2024).

Sun, P. P. & Cai, D. L. Exploration and promotion of full-process mechanized production technology for Chinese chives in greenhouses. Anhui Agric. Sci. Bull. 20, 47–48. https://doi.org/10.16377/j.cnki.issn1007-7731.2014.10.014 (2014).

Chatopadhyay, P. S. & Pandey, K. P. Impact cutting behavior of sorghum stalk model and its experimental verification. Agric. Eng. Res. 04, 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1006/jaer.2000.0623 (2011).

Ma, J. G., Cheng, J. W. & Yao, Y. P. Design of scythe-type leek harvester. Mech. Manuf. 53, 10–12 (2015).

Vadivel, R. et al. Hypaponics - Monitoring and controlling using Internet of Things and machine learning. 1st Int. Conf. Innov. Inf. Commun. Technol. (ICIICT), Chennai, India, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIICT1.2019.8741487 (2019).

Xu, B. X., Chen, Y. S., Guan, C. S., Yu, F. & Chen, H. Design and experiment of disc cutting device for leek harvester. China Agric. Mech. Eng. 45, 79–83. https://doi.org/10.13733/j.jcam.issn.2095-5553.2024.02.012 (2024).

Lian, Y. S. et al. Cutting performance optimization and experimental research of indexable insert drill. Adv. Manuf. 13, 303–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40436-024-00507-y (2025).

Zahoor, S. et al. Investigating drilling efficiency: a study on indexable centerless drilling of Ti-6Al-4 V alloy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 133, 2157–2169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-024-13760-z (2024).

Koshy, P., Dewes, R. C. & Aspinwall, D. K. High speed end milling of hardened AISI D2 tool steel (~58 HRC). J. Mater. Process. Technol. 127, 266–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-0136(02)00155-3 (2002).

Okada, M., Asakawa, N., Sentoku, E., M’Saoubi, R. & Ueda, T. Cutting performance of an indexable insert drill for difficult-to-cut materials under supplied oil mist. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 72, 475–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-014-5691-0 (2014).

Ehsan, S. et al. Evaluating tool wear mechanisms, hole integrity and drilling performance of indexable and solid carbide tools on GFRP-Steel stacked composite. Wear 576–577, 206096. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.WEAR.2025.206096 (2025).

Mathanker, S. K., Grift, T. E. & Hansen, A. C. Effect of blade oblique angle and cutting speed on cutting energy for energycane stems. Biosyst. Eng. 133, 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2015.03.003 (2015).

Tijskens, E., Ramon, H. & De Baerdemaeker, J. Discrete element modelling for process simulation in agriculture. J. Sound Vib. 266, 493–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-460X(03)00581-9 (2003).

Guo, J. et al. Discrete element modeling and physical experiment research on the biomechanical properties of banana bunch stalk for postharvest machine development. Comput. Electron. Agric. 188, 106308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2021.106308 (2021).

Shi, Y. et al. A mechanical model of single wheat straw with failure characteristics based on discrete element method. Biosyst. Eng. 230, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2023.03.017 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Biomechanical properties and discrete element modeling of PSR stalks during silage harvest. Comput. Electron. Agric. 217, 108644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2024.108644 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Design of a hand-held leek harvester. Forest. Mach. Woodwork. Equip. 52, 64–70. https://doi.org/10.13279/j.cnki.fmwe.20240025.004 (2024).

Qiu, M., Meng, Y., Li, Y. & Shen, X. Sugarcane stem cut quality investigated by finite element simulation and experiment. Biosyst. Eng. 206, 135–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2021.03.013 (2021).

Meng, Y. M. et al. An ANSYS/LS-DYNA simulation and experimental study of circular saw blade cutting system of mulberry cutting machine. Comput. Electron. Agric. 157, 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2018.12.034 (2019).

Feng, Y. L. Design and Test of Key Components of Leek harvesters machine. (Master’s thesis) Shenyang Agricultural University, China (In Chinese) (2019).

Wu, K. & Song, Y. P. Research progress on the theory and methods of crop stalk cutting. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 53, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2022.06.001 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the reviewers for their hard work and valuable input. We acknowledge financial support for this work from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51575003, 52175211) and Key Project of Anhui Education Committee (Grant No. 2024AH050448).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51575003, 52175211) and Key Project of Anhui Education Committee (Grant No. 2024AH050448).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X. Y. X wrote the manuscript. X. R. Z did the test. Y. C. L and X. R. W implemented the DEM-MBD simulations. H. R. W and J. H checked the data. Y. J. T conducted the experiment. L. Z performed the investigations. And M. H. X gave the supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, XY., Zou, XR., Zhu, L. et al. Towards an innovative modular cutter of leeks for improving retained stalk quality and prolonging tool life. Sci Rep 15, 43117 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28370-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28370-2