Abstract

Frailty is a multidimensional syndrome of aging increasingly studied in companion dogs. Two main operational models have been developed: the frailty phenotype, based on five clinical criteria, and the frailty index, derived from the accumulation of health deficits. Despite their frequent use in human aging research, no comparative analysis of these models has been conducted in canine populations. Baseline data from 566 dogs aged six years and older in the CaniAge cohort were used to assess frailty using both Frailty Phenotype and Frailty Index. Prevalence of frailty was 6.36% according to the Frailty Index binarised (EARS-FI ≥ 0.49) and 8.48% according to the Frailty Phenotype, with limited overlap between the two classifications. Both measures were positively associated with chronological age and with some adverse health indicators including comorbidity or sleep quality, and reduced quality of life. Multivariable analyses, independently of age and cofounding factors showed that polypharmacy and a lower extraversion were independently associated with frailty index. Engaging in daily activity higher than 15 min per day was negatively associated with frailty phenotype and specific personality traits (low extraversion and motivation) were independently associated with Frailty Phenotype-defined frailty. Findings indicate that the Frailty Index and Frailty Phenotype identify related but distinct domains. The frailty index captures a broader spectrum of physiological decline, whereas the Frailty Phenotype is more closely aligned with observable physical and behavioral characteristics. Use of both instruments provides complementary insights into aging trajectories in dogs and supports their combined application in translational geroscience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Across species, including companion animals, advancing age is closely associated with an increased risk of chronic disease, functional decline, and mortality1,2. Aging is considered as the unintended continuation of developmental processes3, leading to a progressive loss of cellular and tissue integrity. This gradual dysregulation affects multiple physiological systems, reducing resilience and performance. However, chronological age alone fails to capture the complexity and variability of aging4. In human gerontology, the concept of frailty has emerged as a more sensitive and integrative measure to assess biological aging and to predict adverse health outcomes5.

Frailty is defined as a multisystem aging syndrome characterized by decreased physiological and functional reserves and a loss of resilience to stressors6. These biological changes affect most tissues and organs and are further modulated by individual-specific and environmental factors. Although the underlying mechanisms of frailty are not yet fully elucidated, key contributors such as sarcopenia7 and low-grade inflammation8 are central to its pathogenesis9.

In humans, practical applications of the frailty concept have been proposed. The frailty phenotype (FP), as described by Fried and colleagues10, identifies at-risk individuals based on the presence of at least three out of five clinical criteria: unintentional weight loss, weakness, exhaustion, slowness, and low physical activity. Individuals meeting these criteria are approximately six times more likely to die within three years, independently of chronological age. On the other hand, the frailty index (FI), developed by Rockwood and his team11, is based on the accumulation of health deficits, encompassing clinical signs, symptoms, diagnoses, impairments, and laboratory abnormalities.

While these two instruments have often been mistakenly considered as interchangeable, they are fundamentally distinct and should be viewed as complementary approaches12. The FP is regarded as a pre-disability syndrome, making it potentially more relevant for non-disabled older individuals. In contrast, the FI includes diseases and clinical evaluations, focusing more on the accumulation of deficits. and seems particularly interesting to assess individuals independently of functional status12. Some reviews have suggested that FI may outperform the FP in predicting all-cause mortality; however, more recent analyses indicate that the predictive abilities of both tools for mortality may be comparable13. FI may offer finer discrimination at the lower to middle ranges of the frailty spectrum14, and the populations identified by each tool may differ, with stronger associations between frailty, comorbidities, and disability particularly observed among HIV-infected individuals15. Moreover, the FI as a continuous variable may be more sensitive to modification than the FP and may help avoid the risk of misclassification12.

In companion animals, particularly dogs, frailty research is emerging as a promising translational field. With more than 8 million companion dogs in France alone as of 2024, these animals provide a unique opportunity to study aging biology16. Living in shared environments with humans and exhibiting substantial intraspecies phenotypic diversity, dogs represent an ideal model for investigating the interplay between environmental factors and frailty status. Their relatively shorter lifespans and the willingness of owners to share data have conduct to the development of large-scale cohorts, such as the Dog Aging Project17 and the Golden Retriever Lifetime Study18.

Frailty has recently garnered attention in veterinary research, coinciding with the growing population of senior and super-senior dogs, which now account for over 40% of dogs in the United Kingdom19. Frailty indexes and phenotypic models have been adapted for use in dogs20,21,22,23; however, no direct comparison of the populations identified by these two approaches has been published to date. This gap poses a practical challenge for researchers in selecting the most appropriate frailty model for use in canine studies.

The primary objective of this study was to assess the level of concordance between two operational definitions of frailty in dogs: the Frailty Phenotype and the Frailty Index. In case of limited agreement between these approaches, a secondary objective was to characterize the physical, behavioral, and medical profiles of dogs identified as frail by each model, in order to highlight the specific dimensions of aging captured by each.

In line with findings from human geriatric research, it was hypothesized that both the Frailty Index and the FP would be positively associated with age and markers of medicalization (number of drugs per days, …) in dogs. We also expected the two models to identify overlapping but distinct groups of frail dogs, with the FI encompassing a greater number of individuals and showing stronger links to comorbidities, reflecting its broader multidimensional nature relative to the more physically focused FP.

Material and methods

Population and survey

The CaniAge cohort is an online, prospective project of French dog owners with dogs of all breeds aged six years or older, a threshold commonly considered as the onset of senior age in dogs24. The project aims to follow individuals enrolled for a two-year period. Dogs were recruited via the internet and social media platforms. According to EU regulations, ethical approval was not required in this context. At the start of the survey, owners were informed that the study focused on canine aging, that their responses would be stored and analyzed anonymously, and that they could request data withdrawal at any time. Informed consent was obtained electronically. At the end of the survey, owners could choose whether or not to be recontacted for follow-up.

The baseline questionnaire included three sections: New sections will be added for the follow-up of the dogs during the project. The first section gathered preliminary information on both the dog and the owner, including the dog’s and owner’s ages, household composition, feeding practices, play and activity levels, medication use, chronic health conditions, and use of dietary supplements. In the second section, frailty was evaluated using two validated methods in dogs: a phenotypic approach and a frailty index.

The FI used in this study was the Exceptional Aging in Rottweilers Study-Frailty Index (EARS-FI, named FI in the rest of the paper), originally developed to assess aging in Rottweilers23. This index is based on clinical variables collected through a structured telephone interview. The selected health deficits met the following criteria: they reflected adverse health conditions, their prevalence typically increased with chronological age, and collectively, they captured dysfunction across multiple physiological systems. Each variable was scored as 0 if the deficit was absent and 1 if present. For some variables—such as impaired vision or hearing, urinary incontinence, or deficits managed with medication—a score of 0.5 was assigned to reflect mild or controlled conditions. Some items were assessed relative to the dog’s abilities during young adulthood. The FI score was calculated by dividing the total number of health deficits present by the total number of deficits assessed. This index has been previously associated with all-cause mortality. The selection of this instrument over the frailty index developed by Banzato was driven by considerations of practical implementation21. The EARS-FI designed for use in telephone interviews, aligned more closely with the remote, questionnaire-based format employed in the CaniAge cohort.

The FP was assessed based on the method proposed by Russell et al.25 with small adjustments due to the owners’ abilities to answers. Unintentional weight loss was defined either by a body condition score other than 5/9 according the scale of Laflamme26 (with indication of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association body score grid -WSAVA), or by a reported change in eating behavior reported by the owner. Physical activity was evaluated using a 7-point Likert scale response to the question 'Over the past week, how many days has your dog been playful?'. This component was considered impaired if the response was between 0, and 2. Fatigue was assessed through the question 'How often does your dog rest during exercise?', with answers such as 'occasionally', 'frequently', or 'very frequently’ classified as abnormal. The question referred to exercise or play to capture general physical activity rather than formal training. Mobility was evaluated using three items of the questionnaire similar to the methods of Russel et al.25: the frequency of limping while walking, the occurrence of coordination errors during walking, and the frequency of joint stiffness while walking. These criteria were combined into a score ranging from 0 to 7, with 7 indicating abnormal mobility. Muscle condition was assessed by identifying visible muscle mass loss (with indication of the WSAVA muscular grid—Stage 3: severe muscular mass loss). A dog was classified as frail if three or more components were impaired, and as pre-frail if one or two components were affected. In the present study, frailty phenotype was binarized and pre-frail dogs considered non-frail dogs.

A third component of the study involved canine personality with the use of the Monash Canine Personality Questionnaire (MCPQ), which evaluates five personality dimensions: Extraversion, Motivation, Training Focus, Amicability, and Neuroticism. A fourth section assessed sleep quality through the validated SNoRE 3.0 (Sleep and Nighttime Restlessness Evaluation) questionnaire27 and overall quality of life using the Canine Owner-Reported Quality of life (CORQ) instrument28. Finally, the last part of the survey focused on the quality of the dog–owner relationship, with particular attention to the concept of caregiver burden, assessed via the Dog Owner Quality Of Life (DOQOL) questionnaire29. Owners were asked to indicate their age range rather than their exact age. A cutoff of 45 years was used to approximate the third quartile, grouping 21% of owners aged 45 years and older, in order to explore potential generational differences in owner–pet relationships.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed in R (R version 4.4.1). Descriptive statistics were computed to summarize demographic, clinical, and behavioral characteristics of dogs and their owners. Continuous variables were reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), while categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages.

The FI was log-transformed for regression analyses to improve linearity of the association with age and compare with results of the previous study of Waters et al.23. Association between age and frailty index score in continue was explored using Pearson correlation The FI was dichotomized to facilitate its application in clinical settings, as continuous variables are less practical and intuitive for routine use. The cut-off value was determined based on the original EARS-FI study, in which dogs with an index ≥ 0.49 were found to have a twofold higher risk of mortality23.

Concordance between the frailty phenotype and the frailty index classifications was assessed using Cohen’s Kappa coefficient, providing a measure of concordance beyond chance for binary categorical variables. To better characterize the profiles of dogs classified as frail, four subgroups were compared: dogs identified as frail by both the binary Frailty Index and the Frailty Phenotype, dogs classified as frail only by the Frailty Index, dogs classified as frail only by the Frailty Phenotype, and dogs not considered frail by either method. Age and quality of life of dogs within these subgroups were analyzed using Wilcoxon tests with Holm correction.

Group differences in frailty status (frail vs non-frail) were evaluated using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables, these univariates analyses were fit to explore variables suitable for inclusion in multivariate analysis. Multivariable logistic regression models were then constructed to identify factors independently associated with frailty status (based on either FI or FP). Models were adjusted for age, sex, sterilization status, body size (small or miniature breeds), and pain reported by the owner (extracted from the CORQ). These variables are generally considered confounding factors in studies on frailty (age10, pain30) and other species like dogs (age, sterilization status, body size21,22,31).

Variables of interest, based on human bibliography32,33, included health indicators (comorbidity as the presence of two chronical diseases and more, and medication use), behavioral traits (e.g., personality scores from the MCPQ), sleep quality (SNORE). Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. To avoid collinearity, which was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF), a VIF > 5 considered indicative of collinearity and all finals models had VIFs below 2. A significance threshold was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Population and frailty classification

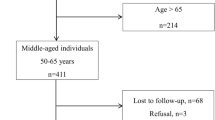

A total of 566 dogs aged 6 years and older were included in the CaniAge cohort. The median age was 9.84 years (IQR: 8.09–11.98). Most dogs were female (n = 288, 50.9%) and sterilized (n = 458, 80.9%). Regarding body size, most were medium (42.8%) or large (35.5%), while small and miniature dogs represented respectively 17.5% and 2.3% of the sample. Giant breeds accounted for only 1.9% of the population. The majority (62%) were purebred.

According to the physical frailty phenotype, 48 dogs (8.48%) were classified as frail. Regarding FI, 35 dogs (6.18%) met the threshold for frailty (FI ≥ 0.49), highlighting some divergence in classification between the two approaches.

Among dogs classified as robust by phenotype, the vast majority (96.33%) were also robust according to the frailty index. Conversely, among dogs phenotypically frail, 35.41% were also classified as frail by the index, leading to a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.36 (p < 0.01; Table 1).

Dogs were classified as frail by both tools (Both FI and FP), by the Frailty Index only (FI only), by the Frailty Phenotype only (FP only), or by neither tool.

Chronological age varied significantly between groups. Dogs in the “Both FI and FP”, were older than those in the “FP only” (p < 0.01). Individuals in the “FI only” tend to be older than “FP only” (p = 0.09). All frailty groups were significantly older than the “None” group (p < 0.01). Quality-of-life scores decreased progressively with frailty severity. The lowest CORQ values were observed in the “Both FI & FP” group, followed by the “FI only” group, whereas “FP only” and “None” dogs showed higher scores. Pairwise Wilcoxon tests confirmed significant differences between the “Both FI and FP” group and the two other frail group (“FI only” and “FP only” others (p < 0.05), and between all frail groups and the non-frail group (p < 0.01). Dogs in the “FI only” groups had a significantly lower quality of life compared dogs in the “FP only” groups (p = 0.02) (Fig. 1).

Frailty index population

Among the 566 dogs included in the study, 36 (6.36%) were classified as frail based on the FI score (Frailty Index ≥ 0.49). In univariate analysis, frail dogs were significantly older (median age 14.18 11.58–15.55]vs. 9.67 [7.97–11.66-], p < 0.01; Table 2) and had lower quality of life scores (CORQ: 3.53 [2.85–4.19] vs. 5.82 [4.88–6,47], p < 0.01; Table 2). Sleep disturbances, as reflected by the SNORE score, were also more pronounced in frail dogs (19.00 [12.75–28.2] vs. 9 [7–13], p < 0.01; Table 2).

Behaviorally, frail dogs showed significantly lower extraversion scores (median 38.89 [31.64–53.47] vs. 55.56 [41.67–69.44], p < 0.01; Table 2), while other personality dimensions did not differ significantly. Frail dogs were less likely to engage in physical activity beyond 15 min (p < 0.01). They received more frequently two or more daily medications (p < 0.01) and had more frequently comorbidity (more than two concurrent disease) (p < 0.01), which is concordant with the methods of calculation of the frailty index. Their quality of life of the owner was also lower (p = 0.02).

In multivariable analysis adjusted for age, sex, neuter status, and pain (according a question of the CORQ) extraversion (0.98 [0.95–0.99] p = 0.05), SNORE (1.11 [1.05–1.16] p < 0.01), comorbidities (5.13[2.12–12.52] p < 0.01) and having more than 2 drugs (5.31 [2.27–12.59] p < 0.01) remained independently associated with frailty (Table 2). Quality of life of the owner tend to be lower in frail dogs (0.81 [0.64–1.01] p = 0.06).

Frailty phenotype

Out of the 566 dogs assessed, 48 (8.48%) were classified as frail according to the physical frailty phenotype. Compared to non-frail dogs, frail individuals were significantly older (median 13.29 vs. 9.70 years, p < 0.01) and had lower quality of life scores (CORQ: 4.1 vs. 5.9, p < 0.01; Table 3). They also had higher SNORE scores, indicating poorer sleep quality (12.5 vs. 10, p < 0.01; Table 3). In addition, frail dogs were less likely to engage in play sessions longer than 15 min with the owner (12.50% vs. 38.61%, p < 0.01; Table 3) or regular physical activity exceeding 15 min (75.00% vs. 94.59%, p < 0.01; Table 3) and were more frequently treated with two or more medications per day (33.33% vs. 10.23%, p < 0.01; Table 3).

In multivariable logistic regression adjusted for age, sex, neuter status, being a dog from a small/miniature breed and pain (according to a question in the CORQ questionnaire), several variables remained independently associated with frailty. Dogs whose owners were aged ≥ 45 years were more likely to be classified as frail (OR = 3.21 [1.54–6.70] p < 0.01; Table 3). Daily activity over 15 min was associated with lower odds of frailty (OR = 0.30 [0.13–0.72] p < 0.01; Table 3) and playing more than 15 min per day (OR = 0.34 [0.12–0.80] p = 0.02; Table 3), whereas receiving two or more medications per day increased the odds of frailty (OR = 2.82, 95% CI [1.23–6.32], p = 0.01; Table 3).

Regarding behavioral dimensions, lower extraversion (OR = 0.95 [0.92–0.97] p < 0.01; Table 3), lower motivation (OR = 0.97 [0.95–0.98] p < 0.01;Table 3) were all independently associated with an increased risk of being classified as frail according to the phenotype.

The Venn diagram (Fig. 2) illustrates the overlap between the five components of the physical frailty phenotype: malnutrition, exhaustion, low physical activity, mobility impairment, and weakness. Malnutrition was the most frequently observed individual component (n = 160), followed by exhaustion (n = 51) and reduced physical activity (n = 25).

The most common overlaps included malnutrition combined with physical inactivity (n = 44), and a triad of malnutrition, mobility impairment, and exhaustion (n = 27). In contrast, weakness and mobility deficits occurred less frequently and rarely in isolation.

Discussion

Our objective was not to determine whether the FI or the FP is superior, but to evaluate the extent to which these instruments capture overlapping versus distinct aspects of canine frailty. The two measures were statistically associated, but the level of agreement remained consistent with previous findings in humans with a partial concordance between the two tools34. This results suggests that the FP and the FI, while related, reflect different dimensions of frailty and support the view that the deficit accumulation model and the physical frailty approach are not interchangeable but rather provide complementary perspectives on the multidimensional nature of frailty15. The comparison of frailty classifications based on the FI and the FP highlights both their complementarity and their potential clinical relevance in aging dogs. The two tools showed partial overlap: dogs identified as frail by both measures were the oldest and had the lowest quality-of-life scores.

This convergence suggests that both approaches capture advanced and clinically evident stages of frailty, in which multiple physiological, behavioral, and functional systems are simultaneously affected. However, the analysis also revealed meaningful discrepancies between the two tools. Dogs categorized as frail by FP only were significantly younger and had intermediate CORQ values, while their FI scores remained relatively low. This pattern indicates that the phenotype-based assessment may detect earlier or more transient manifestations of frailty—driven by observable signs such as fatigue, reduced activity, or mobility issues—before the broader accumulation of health and behavioral deficits measured by the FI becomes evident. In contrast, dogs classified as frail only by FI were older and showed slightly reduced CORQ scores, supporting the idea that the index identifies a subclinical stage of frailty that precedes overt functional decline.

It is also noteworthy that only the FP was associated with owners aged 45 years and older, whereas no comparable association was observed with the FI. This finding warrants further investigation; however, it may be explained by the fact that the FP primarily reflects functional changes, which might be more readily recognized by aged owners who themselves experience similar limitations in their daily lives. Moreover, dogs classified as frail according to the physical frailty phenotype appear to exhibit specific personality traits as characteristics as lower extraversion level and motivation, unlike those classified as frail based on FI. This may be explained by the fact that the index incorporates behavioral information, such as the motivation to play.

In addition, the frailty phenotype and frailty index may tend to classify more introverted dogs as frail independently of age and pain. This finding is consistent with studies in humans showing that higher levels of extraversion are linked to a reduced risk of frailty. In a recent study in dogs, a mismatch in extraversion between the owner and the dog was positively associated with frailty35, suggesting that further investigation into owner personality and their communication style may be warranted in future work. Reduced motivation was also associated with frailty phenotype regardless of the dog’s quality of life (including pain), aligning with human findings where higher agreeableness and openness have been linked to slower onset of frailty36.

In line with human studies, higher extraversion may protect against frailty progression; however, as extraversion encompasses more than playfulness, and given that playfulness can also be influenced by pain, future research should assess this trait through standardized behavioral testing rather than questionnaire-based evaluation. In this preliminary study, our focus was to explore the relationship between extraversion and frailty.

Engaging in more than 15 min of daily activity with the owner was negatively associated with frailty phenotype, independently of the dog’s reported pain levels and overall quality of life. This finding aligns with data from the Dog Aging Project37, and with recent evidence linking increased physical activity to reduced risk of canine cognitive dysfunction38. Although the physical frailty phenotype does not directly assess cognitive function, maintaining regular activity may benefit both physical and cognitive health, as suggested by studies on canine cognitive dysfunction. In the context of human medicine, regular physical activity has been identified as both a protective factor and a potential modifier of frailty trajectories39, raising the question of whether a similar mechanism may exist in dogs. Given that the frailty phenotype is based largely on sarcopenia-related markers—including mobility limitations and reduced muscle mass10—dogs with impaired endurance or muscular function may be less able to maintain regular owner-directed activities. Therefore, reduced physical engagement may represent an early symptom of frailty, while also acting as a contributing factor in the progression of the phenotypic frailty process.. Interestingly, this variable was not associated with the FI, which showed stronger associations with medical history variables such as polypharmacy and comorbidities. This divergence further supports the hypothesis that the index captures cumulative physiological burden, whereas the phenotype reflects more functional and behavioral expressions of aging.

Further investigation is needed to explore the relationship between frailty status, mortality, and health decline over time. The continuation of the CaniAge cohort will allow for longitudinal assessment of these associations, distinguishing between all-cause mortality, cancer-related deaths, and accidental deaths, as well as tracking the evolution of the dog’s quality of life and its relationship with the owner.

Given the increasing interest in the clinical application of frailty assessment in veterinary medicine, it was considered timely to present the key differences between the frailty phenotype and the frailty index. This is especially relevant to prevent the misconception—frequently encountered in human geriatric research—that both approaches are interchangeable. As interest in the concept of frailty continues to grow, it is critical to establish standardized guidelines regarding the use of frailty tools to avoid the proliferation of divergent or redundant questionnaire or methodology, which may ultimately lead to confusion among veterinary professionals.

This study opted to compare the frailty phenotype and the frailty index using binary classifications rather than continuous measures, with the aim of promoting clinical applicability and ease of use. However, future research should assess the predictive value of the frailty index in its continuous form versus its categorical version, particularly with respect to mortality outcomes. Based on previous findings in human cohorts13, it can be hypothesized that the continuous frailty index may offer greater discriminatory power for predicting death.

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study. First, recruitment was conducted entirely online, without clinical validation of the owner-reported medical conditions by a veterinarian. In this context, underreporting of chronic diseases is likely, which may have led to an underestimation of the association between comorbidities and frailty. Nevertheless, a significant relationship was observed between the frailty index and the use of two or more medications, a finding consistent with previous work, including studies in murine models40. Medication count appears to be a reliable and easily reportable proxy for health status from the owner’s perspective, and its positive association with frailty was confirmed. While the FP provides a valuable perspective, its application in owner-reported contexts inevitably introduces a certain degree of subjectivity. To minimize this bias, illustrated guides for Body Condition Score and Muscle Condition Score were provided to all participants, allowing more standardized assessments. Nevertheless, even in veterinary settings, these measures remain partially subjective and may vary across observers. The present study aimed to explore the feasibility of using such indicators under real-life conditions, reflecting how frailty screening could be implemented at a population level. Further validation of these tools in clinical settings, including inter-rater reliability assessments, would be beneficial to strengthen their applicability and precision. Moreover, playfulness was used as a validated but indirect proxy for activity25, which may underestimate activity levels in less playful dogs. Another limitation of this study is that the proposed frailty instruments did not include clinical or laboratory parameters, which are commonly integrated into frailty indices in human and experimental research. This omission was intentional, as the present work relied on a remotely monitored cohort to allow inclusion of a larger number of individuals in this preliminary phase. The choice to prioritize non-invasive, owner-reported data ensured feasibility but may have influenced the instruments’ sensitivity and the type of dogs classified as frail. Nevertheless, the next phases of the CaniAge cohort plan a longitudinal follow-up of selected dog, along with the collection of fecal samples by owners for microbiome analysis. This will provide an opportunity to explore the relationship between gut microbiota and frailty, a growing area of interest in human geroscience. With over 250 dogs expected this expansion will allow for multivariate modeling and the identification of microbiome profiles potentially associated with frailty status41.

Lastly, this study intentionally excluded the concept of cognitive frailty—defined as the co-occurrence of physical frailty and mild cognitive impairment42—which will be explored in future work through combined physical and cognitive assessments of dog owners. This will help determine whether this construction, widely used in human geriatric medicine, holds relevance in the context of veterinary care for aging dogs.

These findings offer valuable perspectives for both clinicians and researchers regarding future protocols related to frailty assessment and the broader application of these tools. The fact that malnutrition emerged as the most frequently observed component of the frailty phenotype highlights the importance of including nutritional assessment in the geriatric evaluation of aging dogs. The results are consistent with prior observations in murine and human models, reinforcing the importance of using both the FP and the FI in a complementary rather than substitutive manner. Differential applicability of the two frailty measures may support their use in distinct contexts. The FP offers a practical advantage for use by dog owners, particularly in non-clinical settings, as it does not require access to veterinary records or clinical expertise. In contrast, the FI relies on comprehensive health information and is therefore more appropriate for use by veterinary professionals. This functional distinction highlights a potential complementarity: the phenotype may serve as a screening tool for owners engaged in monitoring aging-related decline, whereas the index may be better suited for clinical assessment and decision-making. Moreover, combining deficit-based and phenotype-based tools may provide a more comprehensive evaluation of aging dogs, improve early identification of at-risk individuals, and facilitate the development of targeted strategies to maintain functional capacity and well-being in senior and geriatric animals.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M. & Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 153, 1194–1217 (2013).

Pitt, J. N. & Kaeberlein, M. Why is aging conserved and what can we do about it?. PLOS Biol. 13, e1002131 (2015).

Blagosklonny, M. V. Aging is not programmed: Genetic pseudo-program is a shadow of developmental growth. Cell Cycle Georget. Tex 12, 3736–3742 (2013).

Zhang, S. et al. A metabolomic profile of biological aging in 250,341 individuals from the UK Biobank. Nat. Commun. 15, 8081 (2024).

Clegg, A., Young, J., Iliffe, S., Rikkert, M. O. & Rockwood, K. Frailty in elderly people. The Lancet 381, 752–762 (2013).

Thillainadesan, J., Scott, I. A. & Le Couteur, D. G. Frailty, a multisystem ageing syndrome. Age Ageing 49, 758–763 (2020).

Keevil, V. L. & Romero-Ortuno, R. Ageing well: A review of sarcopenia and frailty. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 74, 337–347 (2015).

Vatic, M., von Haehling, S. & Ebner, N. Inflammatory biomarkers of frailty. Exp. Gerontol. 133, 110858 (2020).

Fried, L. P. et al. The physical frailty syndrome as a transition from homeostatic symphony to cacophony. Nat. Aging 1, 36–46 (2021).

Fried, L. P. et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56, M146-156 (2001).

Rockwood, K. & Mitnitski, A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 62, 722–727 (2007).

Cesari, M., Gambassi, G., Abellan van Kan, G. & Vellas, B. The frailty phenotype and the frailty index: Different instruments for different purposes. Age Ageing 43, 10–12 (2014).

Kim, D. J., Massa, M. S., Potter, C. M., Clarke, R. & Bennett, D. A. Systematic review of the utility of the frailty index and frailty phenotype to predict all-cause mortality in older people. Syst. Rev. 11, 187 (2022).

Blodgett, J., Theou, O., Kirkland, S., Andreou, P. & Rockwood, K. Frailty in NHANES: Comparing the frailty index and phenotype. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 60, 464–470 (2015).

Guaraldi, G. et al. Correlates of frailty phenotype and frailty index and their associations with clinical outcomes. HIV Med. 18, 764–771 (2017).

Frye, C., Carr, B. J., Lenfest, M. & Miller, A. Canine geriatric rehabilitation: considerations and strategies for assessment, functional scoring, and follow up. Front. Vet. Sci. 9 (2022).

Kaeberlein, M., Creevy, K. E. & Promislow, D. E. L. The dog aging project: Translational geroscience in companion animals. Mamm. Genome 27, 279–288 (2016).

Guy, M. K. et al. The Golden Retriever Lifetime Study: establishing an observational cohort study with translational relevance for human health. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20140230 (2015).

McMillan, K. M. et al. Estimation of the size, density, and demographic distribution of the UK pet dog population in 2019. Sci. Rep. 14, 31746 (2024).

Hua, J. et al. Assessment of frailty in aged dogs. Am. Vet. Res. J. in press (2016).

Banzato, T. et al. A Frailty Index based on clinical data to quantify mortality risk in dogs. Sci. Rep. 9, 16749 (2019).

Lemaréchal, R. et al. Canine model of human frailty: adaptation of a frailty phenotype in older dogs. J. Gerontol. Ser. A glad006 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glad006.

Waters, D. J. et al. Frailty and mortality risk among dogs with extreme longevity: Development and predictive validity of a clinical frailty index in the exceptional aging in Rottweilers study. Animals 14, 3651 (2024).

Salt, C., Saito, E. K., O’Flynn, C. & Allaway, D. Stratification of companion animal life stages from electronic medical record diagnosis data. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 78, 579–586 (2023).

Russell, K. J. et al. Establishing a clinically applicable frailty phenotype screening tool for aging dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 11 (2024).

Mawby, D. I. et al. Comparison of various methods for estimating body fat in dogs. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 40, 109–114 (2004).

Mondino, A. et al. Development and validation of a sleep questionnaire, SNoRE 3.0, to evaluate sleep in companion dogs. Sci. Rep. 13, 13340 (2023).

Giuffrida, M. A., Brown, D. C., Ellenberg, S. S. & Farrar, J. T. Development and psychometric testing of the Canine Owner-Reported Quality of Life questionnaire, an instrument designed to measure quality of life in dogs with cancer. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 252, 1073–1083 (2018).

Oyama, M. A. et al. Measuring quality of life in owners of companion dogs: Development and validation of a dog owner-specific Quality of Life Questionnaire. Anthrozoös 30, 61–75 (2017).

Megale, R. Z. et al. Association between pain and the frailty phenotype in older men: longitudinal results from the Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project (CHAMP). Age Ageing 47, 381–387 (2018).

Waters, D. J. et al. Applying a life course approach to elucidate the biology of sex differences in frailty: Early-life gonadectomy diminishes late-life robustness in male and female dogs in the Exceptional Aging in Rottweilers Study. Biol. Sex Differ. 16, 52 (2025).

Wang, X., Hu, J. & Wu, D. Risk factors for frailty in older adults. Medicine (Baltimore) 101, e30169 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Factors associated with frailty in older adults in community and nursing home settings: A systematic review with a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 13, 2382 (2024).

Zhu, Y. et al. Agreement between the frailty index and phenotype and their associations with falls and overnight hospitalizations. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 66, 161–165 (2016).

Blanchard, T., Mugnier, A., Déjean, S., Priymenko, N. & Meynadier, A. Exploring frailty in apparently healthy senior dogs: A cross-sectional study. BMC Vet. Res. 20, 436 (2024).

Bos, E. G. T. et al. The impact of personality traits on the course of frailty. Clin. Gerontol. 48, 141–148 (2025).

Lee, H., Collins, D., Creevy, K. E., Promislow, D. E. L., & Dog Aging Project Consortium. Age and physical activity levels in companion dogs: results from the dog aging project. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 77, 1986–1993 (2022).

Bray, E. E. et al. Associations between physical activity and cognitive dysfunction in older companion dogs: results from the Dog Aging Project. GeroScience 45, 645–661 (2023).

Corral-Pérez, J. et al. Risk and protective factors for frailty in pre-frail and frail older adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 20, 3123 (2023).

Mach, J. et al. Preclinical frailty assessments: Phenotype and frailty index identify frailty in different mice and are variably affected by chronic medications. Exp. Gerontol. 161, 111700 (2022).

Jiao, X. et al. Progressive gut microbiota shifts and functional alterations across aging stages and frailty in mice. iScience 28 (2025).

Facal, D., Burgo, C., Spuch, C., Gaspar, P. & Campos-Magdaleno, M. Cognitive frailty: An update. Front. Psychol. 12 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Audrey Birkus-Dujardin for her careful proofreading of the manuscript and her valuable contributions to enhancing the quality of the American English language throughout the text.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors. The work was supported by shelter AVA through a CIFRE contract via ANRT funding A. Besegher ’s salary, and by UniLaSalle for the salary of N. Rebout, P. Anton, Y. Stephan and Hoummady. The funding bodies have no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. Data acquisition was primarily conducted by S.H. A.B., N.R., and P.A. were additionally involved in drafting the manuscript. N.R. also contributed to the statistical analysis. All authors participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data and provided critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A. Besegher is currently undertaking a university doctoral research project, including the present study, which is financially supported by the association Agir pour la Vie Animale (AVA, France). T. Bedossa is the founding president of the association Agir pour la Vie Animale (AVA), which financially supports the doctoral project associated with this study. S. Hoummady performs occasional consulting work for various companies in the field of animal health. N. Rebout, P. Anton, M. Robles, and Y. Stephan have no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of the paper. None of these affiliations or sources of support had any influence on the design, analysis, interpretation, or reporting of the study.

Ethics approval

All procedures complied with relevant national and European regulations. Ethical approval was not required, as the study consisted solely of non-invasive, voluntary questionnaires completed online by dog owners. No clinical or experimental procedures were performed on animals or humans. In accordance with French legislation and European Union law, such non-interventional research does not require approval from an ethics committee (Article L.1121-1 of the French Public Health Code). Participation was entirely voluntary, and respondents provided informed consent by self-enrolling and submitting the completed questionnaire. They were clearly informed that their responses would be used for research purposes. All data were fully anonymized at the time of collection and processed in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained electronically from all participants during the survey. Participation was entirely voluntary, and respondents were clearly informed about the anonymous nature of the data, the purpose of the research, and their right to withdraw at any time. Participants who wished to be contacted for follow-up explicitly agreed by ticking an optional checkbox at the end of the questionnaire, in accordance with national reglementation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoummady, S., Besegher, A., Jeannin, S. et al. Comparison of the frailty phenotype and frailty index for identifying vulnerable companion dogs. Sci Rep 15, 44608 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28382-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28382-y