Abstract

Bloom filters (BFs) are efficient probabilistic data structures widely used for set membership queries, but can suffer from false positives, particularly with large datasets. This study proposes a novel method to reduce false positives in BFs for image retrieval by incorporating content-based check bits derived from image captions and image intensity. The approach introduces check bits generated from image captions and image data, enabling more compact BFs without compromising performance. Experiments conducted on a dataset of 31,783 images from Flickr demonstrate that our method significantly reduces the false positive rate, even with smaller filter sizes. By leveraging auxiliary data, our technique enhances BF efficiency in terms of memory usage and processing power, making it more practical for large-scale image retrieval, database management, and network security applications. This work highlights the importance of optimizing BF performance by integrating additional data sources to achieve high efficiency with minimal computational overhead.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bloom filters (BFs) are widely recognized as a robust data structure for efficiently performing approximate set membership queries1. Their compact design and ability to quickly assess whether an element likely belongs to a set, though with a minor chance of false positives, have made them a widely favored tool across diverse applications2. While BFs have conventionally been used for managing textual and numerical data, their potential lies in image processing, where efficiently handling large volumes of visual data poses a significant challenge.

Building on this idea, Image-based Bloom Filters (IBFs) have gained traction as an effective tool for tasks such as image similarity searches and recognition3. Unlike conventional BFs that deal with text or numeric data, IBFs are tailored for visual content. By compressing images into concise representations, IBFs enable fast visual data comparison, making them ideal for large-scale image retrieval and similar applications. Essentially, IBFs apply the core principles of BFs to image processing by transforming features like color, texture, and structure into a form that works with BF operations.

The process starts with feature extraction, where key visual elements of an image are analyzed and converted into a digital format. These elements can include color histograms, texture patterns, or more sophisticated descriptors from deep learning models4. After extraction, the features are hashed into a bit array through multiple hash functions, resulting in a compact yet informative image representation. During a query, the IBF compares the hashed features to the bit array to determine if a match is probable. While this method significantly accelerates the search process, it still maintains the probabilistic characteristics of BFs, meaning false positives, though infrequent, can still occur.

IBFs offer several benefits, especially in situations that demand rapid filtering of irrelevant data while conserving computational power for more relevant options. In applications like large-scale image retrieval, content-based classification, or biometric recognition, IBFs’ ability to quickly focus on likely matches proves invaluable5. Their strength lies in efficient storage, processing, and scalability, making them highly effective for managing large datasets. However, this efficiency comes with tradeoffs, such as the possibility of false positives and the necessity of fine-tuning parameters like bit array size and the number of hash functions.

Thus, this paper investigates the design and application of IBF, emphasizing how they can be optimized for handling image-based data effectively. A primary focus is on addressing the issue of false positives, a common limitation of BFs, by leveraging the use of check bits6. These check bits, generated from image captions and visual content, provide an extra layer of verification, helping to lower the probability of false positives without significantly increasing the requirements for storage or computation. Our analysis and experiments show that this method offers a favorable tradeoff between efficiency and accuracy in image retrieval systems.

The key contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

Implementing check bits to minimize false positives in BF;

-

Leveraging caption-based check bits as a form of content-based verification to further reduce false positives;

-

Utilizing image intensity-derived check bits to enhance the efficiency of BF;

-

Augmenting the caption and image check bits derived from image captions and content. Thus, the combination reduces false positives and provides optimal BF efficiency using a smaller-sized BF.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: section “Related work” highlights the related work. Section “Proposed approach” sheds light on the proposed approach. Section “Experiments and Results” thoroughly discusses the experiments and results. Comparative evaluation is provided in section '‘Comparative Evaluation”. The paper concludes with a summary and future directions.

Related work

IBFs have emerged as a focal point of research due to their effectiveness in handling diverse data storage and retrieval tasks. Mitzenmacher and Upfal7 and Broder and Mitzenmacher8 laid the theoretical groundwork for BFs, which serves as the foundation for IBFs. Building upon this theoretical framework, Kirsch et al.9 proposed optimizations to traditional BFs, which can be extended to IBFs, enhancing their performance. The versatility of BF, demonstrated in applications like probabilistic verification by10, suggests promising integration opportunities for IBFs into probabilistic models within image-based systems. In addition to the conventional application of BFs, the work in11 has pioneered an extension of this concept into approximate state machines. This leap expands the utility of BFs, particularly in image data processing, presenting exciting new avenues for exploration.

Putze et al.12 introduce cache-hash and space-efficient variants of BF, specifically to alleviate resource constraints encountered in image processing environments utilizing Invertible BF. A detailed review by Broder and Mitzenmacher8 examines the diverse network applications of BF. Additionally, the study of data locality in algorithms by Acar et al.13 offers valuable perspectives for optimizing IBF performance in image processing. Compact and concurrent caching strategies proposed by Fan et al.14 promise to improve storage and retrieval efficiency operations within IBFs. Furthermore, alternate hashing methods, such as cuckoo hashing15, provide practical solutions for enhancing collision resolution within IBFs.

Similarly, Araujo et al.4 introduce a framework that applies BFs for large-scale video retrieval using image-based queries. Conventional methods involve indexing each video frame separately, which results in high latency and considerable memory usage. To address this, the researchers propose a system that employs BFs to index extended video segments (or scenes), facilitating faster and more scalable retrieval. This approach significantly enhances retrieval speed and accuracy compared to traditional frame or shot-level indexing. Using scene-based descriptors with Fisher embeddings in conjunction with BFs, the system achieves up to a 24% improvement in mean average precision.

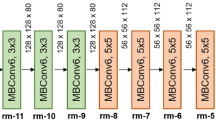

Chakrabarti16 proposes an image retrieval approach that utilizes neural hash codes and BFs to minimize false positives. The study explores how features extracted through Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can be used to match images, thereby simplifying the retrieval process. The method leverages high-level and low-level feature maps by incorporating multiple neural hash codes derived from various CNN layers. A hierarchical retrieval strategy is employed, beginning with semantically similar images at a broad level and then narrowing down to structural similarities managed through BFs.

In a different context, Breidenbach et al.3 introduce a privacy-enhanced image hashing technique that utilizes BFs. This research focuses on applying BFs to store robust image hashes, thereby improving privacy in applications such as forensic analysis and content filtering. The approach preserves privacy by embedding cryptographic hash functions into the BF structure while ensuring efficient identification of known illegal content. The authors evaluate the effectiveness of this method by analyzing error rates and the level of privacy protection it achieves. Furthermore, Li et al.17 explore secure image search in cloud-based Internet of Things (IoT) environments by developing the Merged and Repeated Indistinguishable Bloom Filter (MRIBF) structure. MRIBF reduces storage overhead and enhances security by achieving a lower false positive rate. Their proposed Bloom Filter-based Image Search (BFIS) approach enables faster and more precise searching. Both theoretical analysis and extensive experiments demonstrate the scheme’s accuracy, security, and practical efficiency.

Additionally, BFs have found applications in steganography and image security. Salim et al.18 introduce a steganography method that combines chaotic systems with BFs to improve security. By employing Lorenz’s chaotic system to generate pseudorandom image positions, the method overcomes weaknesses in the Least Significant Bit (LSB) approach used in steganography. Integrating BFs helps prevent data repetition and loss within the same pixel, making it more resistant to visual and analytical attacks. In another context, Jiang et al.19 propose enhancing the traditional BF algorithm, for barcode recognition and processing. The paper tackles the challenge of high false positive rates in large-scale applications. Their approach splits the BF’s bit vector into two sections and uses differential amplification to accentuate the differences between elements. This refinement reduces the false positive rate without significantly increasing processing costs.

Ng et al.20 propose a scalable image retrieval system utilizing a two-layer BF to enhance retrieval performance on mobile devices. The first layer leverages Asymmetric Cyclical Hashing (ACH) for initial verification, while the second layer applies secure hashing to further minimize false positives . This model increases retrieval accuracy, accelerates the process, and requires less space than other techniques. In a related development, Pontarelli et al.21 introduce the Fingerprint Counting Bloom Filter (FPCBF), which uses fingerprints to decrease false positives in Counting Bloom Filters (CBFs). In contrast to previous approaches like Variable Increment Counting Bloom Filter (VICBF), FPCBF provides superior performance, particularly in reducing false positives, with a more straightforward implementation. The theoretical analysis and simulations indicate that FPCB surpasses VICBF, mainly when larger bits per element are used. Yu et al.22 developed an image hashing technique using low-rank sparse matrix decomposition.

Recent advancements in cross-modal retrieval and medical image analysis have been driven by deep learning techniques, leading to significant improvements in efficiency and accuracy. Wang et al.23 introduced an innovative approach to enhance the alignment and interaction between different data modalities, improving how information is retrieved in cross-modal tasks. By improving alignment mechanisms, the model enhances retrieval accuracy across modalities. This study directly supports the motivation for combining captions with image features, reinforcing the check-bit strategy employed in the current paper. In the medical field, Li et al.24 explored a method for visualizing 3D medical images emphasizing importance-aware retrieval, making it easier for professionals to access relevant medical content. Meanwhile, Cai et al.25 leveraged generative adversarial networks (GANs) to create multi-style cartoonization, utilizing multiple datasets to enhance image transformation quality. Similarly, deep learning has also been applied to remote sensing. Feng et al.26 developed a technique to improve road detection from satellite images by enhancing how road features are captured and analyzed.

In ophthalmic image analysis, researchers have made significant strides in automating disease detection and image quality assessment. One study27 introduced a fuzzy broad learning system to segment the optic disk and cup for glaucoma screening, providing a more efficient approach to early diagnosis. Another approach focused on ensuring the reliability of medical imaging by developing a domain-invariant, interpretable method for assessing fundus image quality28. Additionally, vessel extraction from non-fluorescein fundus images has been improved using an orientation-aware detector, which aids in accurately identifying blood vessels—an essential step in diagnosing retinal diseases29. These studies highlight how artificial intelligence is transforming fields such as medical imaging, remote sensing, and information retrieval, paving the way for more accurate, efficient, and automated analysis in healthcare and beyond.

Li et al.30 proposed the Merged and Repeated Indistinguishable Bloom Filter (MRIBF) to enable secure and efficient image retrieval in cloud-based IoT environments. Their approach reduces storage overhead and minimizes false positives, common limitations in traditional Bloom Filter implementations. This work demonstrates the potential of BF optimizations for scalable and secure retrieval, closely related to the present study’s focus on enhancing retrieval accuracy.

Salim et al.31 introduced a novel image steganography method that combines the Lorenz chaotic system with Bloom Filters to improve security and robustness. Integrating BFs strengthens resistance against visual and statistical attacks, offering improved data hiding capabilities. Although targeted at steganography, this study underscores how Bloom Filters can be extended to support security-critical multimedia applications, which complements the retrieval-oriented perspective of the current work.

Although there have been some attempts, as discussed in the aforementioned studies, to handle diverse data storage and retrieval tasks through different approaches, a content-based approach that utilizes image and caption data to generate bits has not yet been considered. Therefore, we propose this approach, and the details are discussed in the following section.

Proposed approach

We present a content-based approach that utilizes image and caption data to generate bits that help minimize false positives in BFs. These bits, referred to as check bits, enhance the accuracy of the filtering process.

One potential method for decreasing the occurrence of false positives in BFs is to increase the filter size. However, this technique requires large memory and computational resources, which may not be suitable for large datasets. On the other hand, our approach focuses on optimizing performance without requiring a larger BF. Our proposed approach thus aims to reduce the size of the BF while still achieving good overall performance by reducing the number of false positives in the filter. We keep the BF smaller and reduce the false positives by introducing content bits (check bits) from the caption of the image and the image (intensity content) components. Fig. 1 shows the flow of the image caption-based check bits generation, and Fig. 2 shows the image content-based check bits generation. These are evaluated in the experimental evaluation.

First, we explain the general approach to generating the check bits. This strategy is similar to that used in Figs. 1 and 2.

We can use numerical or textual data to generate check bits. The input data is then converted into binary form. Next, the generated binary bits are summed to create decimal equivalents. The obtained decimal number is converted to 1’s and 0’s. Since there will be a large number of 1’s and 0’s, we select only a representative few bits (at least three or more) from the large number of 1’s and 0’s. We refer to these representative bits as the check bits. The objective is to keep the number of check bits smaller. Increasing the number of check bits can reduce the false positives. However, it can also increase processing and memory requirements. Thus, the optimum number of check bits selection is crucial for balancing false positive reduction and computational power usage. Therefore, after binary equivalence, we have several possibilities for selecting the check bits to extract the optimal number of check bits. The check bits can be extracted from the beginning, middle, or end of the data. However, in the experimental evaluation, we found that the selection of check bits from the middle is optimal in most cases. For the proposed approach, the check bit offset is set to 1, meaning that the incremental offset for the next check bit is 1. The number of hash functions to generate check bits is set to three, which is found to be optimal in many scenarios.

The algorithm is provided next:

Experiments and results

The dataset selected for this study, proposed by32, comprises 31,783 photographs sourced from Flickr 3, depicting a wide range of everyday activities, events and scenes, along with 158,915 captions generated through crowdsourcing. A sample is shown in Fig 3 (Obtained from https://www.flickr.com/).

This extensive collection builds upon and extends the corpus initially created by33, which included 8,092 images. The size of the dataset offers a suitable balance, making it comprehensive enough for in-depth analysis yet manageable for computational processes, which is crucial for the efficacy of machine learning models. The methodology for gathering images and generating captions is similar to that established by33, incorporating similar annotation guidelines and quality controls to correct spelling errors and eliminate ungrammatical or non-descriptive sentences. This approach guarantees consistency and reliability in the dataset.

For each image, five independent annotators, unfamiliar with the specific details or entities in the images, provide captions. This approach reduces individual bias, resulting in more generalized descriptions like “A group of people cooking outdoors” instead of personal narratives such as “My family’s barbecue party.” This format proves valuable as it allows for exploring various computational techniques, including the use of BFs, which benefit from categorizing captions to improve semantic analysis.

The specificity range in captions provides a broad spectrum of data for analysis. This diversity is crucial for inducing denotational similarities between expressions that extend beyond straightforward syntactic rewrite rules, aligning perfectly with the goals of the BF implementation.

We conducted diverse experiments and tested how different setups affect the likelihood of false positives in a computer system dealing with a large dataset. More specifically, we looked at factors like the number of images, the size of the BF, and additional check bits.

Using captions only

In the first set of experiments, we rely solely on the captions to generate check bits. As shown in Table 1, 10,000 images are considered. The size of the BF is set to 500. Moreover, only three check bits are used. It is important to note that the size of the BF is much smaller than the number of images.

The results showed a big difference when check bits were employed compared to when they were not. Without check Bits, the system made false positive identifications about 99% of the time. However, the rate dropped to 90% when check bits were added. This improvement means adding check bits helped reduce false positives, but they still occurred. The reason for the extraordinary number of false positives is the vast difference between the BF size and the number of images.

This experiment highlights the complexity of designing computer systems to handle large amounts of data. It suggests adding extra features like check bits to improve accuracy, but there is still room for improvement. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for developing reliable systems for tasks such as searching through information, managing databases, and securing networks.

Usage of image hash only

In the updated analysis, we considered the image hash rather than the image captions. The number of images was reduced to 1000. However, the rest of the parameters remained the same, just like in the experiment involving captions only. Table 2 depicts the values of different parameters.

Without check bits, false positives occur about 73% of the time. While this represents an improvement from previous results, errors persist. The main reason is that the number of images is still twice as large as the BF. However, with the inclusion of check bits, the rate of false positives drops significantly to just 25%. This reduction is substantial compared to the prior scenario without check bits and the earlier one with check bits.

These results emphasize the importance of incorporating supplementary features like check bits to refine the accuracy of systems managing extensive datasets. They also underscore how even minor configuration adjustments can profoundly impact system performance. Such insights are pivotal for developing dependable computer systems for data retrieval and network security tasks.

Augmentation of the image hash with the image caption

In the last round of these experiments, we shifted the attention from simple parameters such as the BF and check bits to the positioning of captions in the hash construction. The headers were affixed in the following structures: only at the starting point of the hash, at both the starting and ending points of the hash, and only at the finishing point. This structure demonstrates the arrangement of data, so we changed the places of the captions to test how this affected the false positive rates. The overall parameters were kept similar to those of Experiment 2, with 1,000 images, a BF size of 500, and the use of 3 check bits.

Captions at the beginning of the hash: Initially, placing captions only at the start of the hash structure resulted in a high false positive rate of 82%. However, this rate significantly dropped to 31% with the addition of check bits, showing their effectiveness in reducing errors. This reduction suggests that using check bits improves the efficacy of the BF when captions are placed at the start of the hash.

At the beginning and end of the hash: When captions were placed at both the beginning and end, the false positive rate decreased to 74% without check bits and to 24% with their inclusion, showing a substantial improvement in accuracy.

At the end of the hash: On the other hand, placing captions only at the end resulted in a high false positive rate of 82% without check bits, which, however, decreased to 31% when check bits were used.

These findings emphasize how the placement of captions within the hash structure influences system accuracy, particularly when check bits are employed. The results suggest that positioning captions at both the beginning and end of the hash structure yields the most significant reduction in false positives, as illustrated in Fig 4. Furthermore, this shows the importance of considering implementation details alongside fundamental parameters to optimize computational systems for data analysis and management.

Comparative evaluation

The comparative evaluation is based on the approximate Neural Bloom Filter (NBF) of 34 and 35. For the comparative evaluation, the proposed approach is termed the Check-bits-based Bloom Filter (CBF), whereas the Neural Bloom Filter will be represented as the NBF. For the CBF, we selected the approach with the best performance, which uses the caption in the middle of the hash in the caption location column of the previous section. In this specific setting, we achieved the highest reduction of false positives with a total FP of 23%. We thus use these evaluation settings in all comparative evaluations with the NBF. Table 3 depicts the settings for the evaluation of CBF and NBF.

False positive rate

In the first set of comparative experiments, we evaluate the total number of FP when the bloom filter size is kept constant at a 500-sized array.

In the first comparative evaluation experiment, we compared two approaches for handling false positives: CBF and NBF. As depicted in Fig 5, the results showed that CBF had a lower FP rate of 23%, while NBF had a considerably higher FP rate of 35%. The CBF combines the image and caption data, providing a richer and more detailed understanding of the content. Therefore, when the CBF checks if an image is a match, it has more unique features to consider, which reduces the chances of mistakenly identifying something as a match. In NBF, while captions provide some context, they do not capture as much detail as images. As a result, the system may struggle to distinguish between similar captions, leading to an increase in false positives. The CBF simple checkbits approach here has a simpler feature space to work with, which helps in reducing FP.

Fixed false positives

In the second set of comparative evaluation experiment, we experiment with fixing the total FP rate, and check how much memory space (size of array) is required to achieve the desired FP perfectly. One approach to decreasing the FP in bloom filter approaches is to keep increasing the memory size of the filter array. We take this as an evaluation measure and compare the NBF and CBF with 1% and 5% fixed FP rates. The performance of the two algorithms is shown in Table 4 and Fig 6.

The results show that CBF, which uses images and captions, requires considerably more memory. In order to keep the FP rate at 5%, it needs 300 kb of memory, and for 1%, it needs 500 kb. On the other hand, NBF, which only employs captions, is much more memory-efficient, requiring just 500 b for a 5% FP rate and 1 kb for a 1% rate. This shows that while CBF can reduce false positives more effectively by using image and text data, it comes with a tradeoff of higher memory usage. NBF, although more efficient in memory use, does not capture additional information from images, which means it requires less memory and offers less detailed results.

Computational tradeoffs

We also evaluate the computational costs of querying for CBF and NBF. However, regarding computational costs, we only consider the captions of images for both CBF and NBF. We measure latency as the time to complete a single insertion/query of a row and key string having a certain fixed length. We also consider the average computational cost of 1000 queries plus insertions. We found that the combined query and insert latency of the NBF amounts to 4.9 ms on the CPU. For the CBF, it is around 2.5 ms as depicted in Fig 7. Therefore, the CBF is approximately 50% faster in this evaluation. We argue that for lower latency of the NBF, the Learned Index incurs a much larger latency due to the sequential application of gradients, a common and standard issue with neural models.

Conclusion and future works

This paper introduced a novel method for enhancing Bloom Filters (BFs) in image retrieval applications. We added small pieces of verification data, called check bits, which are created from both image captions and the images themselves. This approach significantly reduces the number of false positives—a well-known limitation of BFs—while maintaining a small filter size . Experiments on a large dataset showed that using these check bits significantly reduces false positive rates. We also found that the placement of caption data (e.g., at the start, middle, or end of the hash) affects performance, with the best results achieved when caption data is placed at both the beginning and the end of the hash. In a comparison with a modern Neural Bloom Filter (NBF), our method—called the Check-bits-based BF (CBF)—achieved a lower false positive rate (23% vs. 35%) under the same memory constraints. Although the NBF requires less memory for stringent error rates, our CBF is approximately 50% faster, making it more suitable for applications where speed is a priority. In a nutshell, this work demonstrates that incorporating both text and image content enhances the accuracy and efficiency of BFs. This improvement is useful for real-world tasks such as image search, database management, and network security.

Several interesting directions for future research exist. First, we plan to test this idea on other types of data, such as audio and video. Another perspective for further research is the development of intelligent algorithms that can adaptively determine the number of check bits to use and their placement, based on the input data. We also aim to test the method on more diverse and challenging datasets to ensure it works well in different situations. Ultimately, employing more advanced feature extraction techniques, such as newer deep learning models, may further enhance performance . These refinements would enable significant cost savings while improving BF performance across various applications and supporting the increased diversity and complexity of data.

Data availability

The data is freely available from https://shannon.cs.illinois.edu/DenotationGraph/data/index.html.

Code availability

Link to the source code: https://github.com/rehanmarwat1/bloomf.

References

Luo, L., Guo, D., Ma, R. T., Rottenstreich, O. & Luo, X. Optimizing bloom filter: Challenges, solutions, and comparisons. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 21(2), 1912–1949. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2018.2889329 (2018).

Tarkoma, S., Rothenberg, C. E. & Lagerspetz, E. Theory and practice of bloom filters for distributed systems. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 14(1), 131–155. https://doi.org/10.1109/SURV.2011.031611.00024 (2011).

Breidenbach, U., Steinebach, M. & Liu, H. Privacy-enhanced robust image hashing with bloom filters. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1145/3407023.3409212 (2020).

Araujo, A., Chaves, J., Lakshman, H., Angst, R. & Girod, B. Large-scale query-by-image video retrieval using bloom filters. arXiv preprint arXiv:1604.07939. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1604.07939 (2016).

Rae, J., Bartunov, S. & Lillicrap, T. Meta-learning neural bloom filters. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 5271–5280 (PMLR, 2019).

Alsuhaibani, M., Khan, R., Qamar, A. & Alsuhibany, S. Content-based approach for improving bloom filter efficiency. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427951.2004.10129096 (2023).

Mitzenmacher, M. & Upfal, E. Probability and Computing: Randomized Algorithms and Probabilistic Analysis (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511813603.

Broder, A. & Mitzenmacher, M. Network applications of bloom filters: A survey. Internet Math. 1(4), 485–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427951.2004.10129096 (2004).

Kirsch, A. & Mitzenmacher, M. Less hashing, same performance: Building a better bloom filter. In Algorithms—ESA 2006 (eds Azar, Y. & Erlebach, T.) 456–467 (Springer, Berlin, 2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/11841036_42.

Dillinger, P. C. & Manolios, P. Bloom filters in probabilistic verification. In Formal Methods in Computer-Aided Design (eds Hu, A. J. & Martin, A. K.) 367–381 (Berlin, Springer, 2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-30494-4_26.

Bonomi, F., Mitzenmacher, M., Panigrah, R., Singh, S. & Varghese, G. Beyond bloom filters: from approximate membership checks to approximate state machines. SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev. 36(4), 315–326. https://doi.org/10.1145/1151659.1159950 (2006).

Putze, F., Sanders, P. & Singler, J. Cache-, hash-, and space-efficient bloom filters. ACM J. Exp. Algorithm. https://doi.org/10.1145/1498698.1594230 (2010).

Acar, U., Blelloch, G. & Blumofe, R. The data locality of work stealing. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual ACM Symposium on Parallel Algorithms and Architectures. SPAA ’00, 1–12 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2000). https://doi.org/10.1145/341800.341801.

Fan, B., Andersen, D. & Kaminsky, M. MemC3: Compact and concurrent MemCache with dumber caching and smarter hashing. In Proceedings of the 10th USENIX Conference on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI’13), 371–384 (USENIX Association, USA, 2013). https://doi.org/10.5555/2482626.2482662.

Pagh, R. & Rodler, F. Cuckoo hashing. J. Algorithms 51(2), 122–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalgor.2003.12.002 (2004).

Chakrabarti, S. Efficient image retrieval using multi neural hash codes and bloom filters. In 2020 IEEE International Conference for Innovation in Technology (INOCON), 1–6 (IEEE, 2020). https://doi.org/10.33130/AJCT.2020v06i03.004.

Li, Y. et al. Secure and efficient bloom-filter-based image search in cloud-based internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 11(3), 5024–5035. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2023.3301969 (2024).

Salim, A., Abdulbasit, M. K., Maath, J. F. & Makki, S. A. Image steganography technique based on Lorenz chaotic system and bloom filter. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 16(1), 851–859. https://doi.org/10.12785/ijcds/160161 (2024).

Jiang, M., Zhao, C., Mo, Z. & Wen, J. An improved algorithm based on Bloom filter and its application in bar code recognition and processing. EURASIP J. Image Video Process. 2018, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13640-018-0375-6 (2018).

Ng, W. W. Y., Xu, Y., Tian, X., Yang, Y., Wu, H. & Gao, Y. Improved bloom filter for efficient image retrieval on mobile device. In 2022 12th International Conference on Information Science and Technology (ICIST), 265–270. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIST55546.2022.9926800 (2022).

Pontarelli, S., Reviriego, P. & Maestro, J. A. Improving counting bloom filter performance with fingerprints. Inf. Process. Lett. 116(4), 304–309 (2016).

Yu, Z. et al. A novel image hashing with low-rank sparse matrix decomposition and feature distance. Vis Comput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00371-024-03517-w (2024).

Wang, M., Meng, M., Liu, J. & Wu, J. Adequate alignment and interaction for cross-modal retrieval. Virtual Real. Intell. Hardw. 5(6), 509–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vrih.2023.06.003 (2023).

Li, M., Jung, Y., Fulham, M. & Kim, J. Importance-aware 3D volume visualization for medical content-based image retrieval—a preliminary study. Virtual Real. Intell. Hardw. 6(1), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vrih.2023.08.005 (2024).

Cai, J., Li, F. W. B., Nan, F. & Yang, B. Multi-style cartoonization: Leveraging multiple datasets with generative adversarial networks. Comput. Anim. Virtual Worlds 35(3), e2269. https://doi.org/10.1002/cav.2269 (2024).

Feng, S., Hou, F., Chen, J. & Wang, W. Extracting roads from satellite images via enhancing road feature investigation in learning. Comput. Anim. Virtual Worlds 35(3), e2275. https://doi.org/10.1002/cav.2275 (2024).

Ali, R. et al. Optic disk and cup segmentation through fuzzy broad learning system for glaucoma screening. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 17(4), 2476–2487. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2020.3000204 (2021).

Shen, Y. et al. Domain-invariant interpretable fundus image quality assessment. Med. Image Anal. 61, 101654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2020.101654 (2020).

Yin, B. et al. Jia W Vessel extraction from non-fluorescein fundus images using orientation-aware detector. Med. Image Anal. 26(1), 232–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2015.09.002 (2015).

Li, Y. et al. Secure and efficient Bloom-filter-based image search in cloud-based IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 11(3), 5024–5035. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2023.3301969 (2024).

Salim, A., Mohammed, K. A., Jasem, F. M. & Sagheer, A. M. Image steganography technique based on Lorenz chaotic system and bloom filter. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 16(1), 851–859. https://doi.org/10.12785/ijcds/160161 (2024).

Young, P., Lai, A., Hodosh, M. & Hockenmaier, J. From image descriptions to visual denotations: New similarity metrics for semantic inference over event descriptions. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2, 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1162/tacl_a_00166 (2014).

Hodosh, M., Young, P. & Hockenmaier, J. Framing image description as a ranking task: Data, models and evaluation metrics. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 47, 853–899. https://doi.org/10.1613/jair.3994 (2013).

Chen, H. et al. Deep learning-based bloom filter for efficient multi-key membership testing. Data Sci. Eng. 8, 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41019-023-00224-9 (2023).

Liu, Y., Li, X., Si, X., Zhang, M., Yuan, K. & Li, P. A neural network and bloom filter-based name search method in named data networking. In 4th International Conference on Neural Networks, Information and Communication Engineering (NNICE), 110–113 (IEEE, Guangzhou, China, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/NNICE61279.2024.10499124.

Acknowledgements

The Researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Rehan Ullah Khan; Data collection: Ali Mustafa Qamar; Methodology: Rehan Ullah Khan; Formal Analysis: Rehan Ullah Khan, Mohammed Alsuhaibani; Software: Rehan Ullah Khan; Visualization: Mohammed Alsuhaibani, Suliman Alsuhibany; Writing-Original draft: Ali Mustafa Qamar, Rehan Ullah Khan, Mohammed Alsuhaibani, Suliman Alsuhaibany; Project Administration: Rehan Ullah Khan, Mohammed Alsuhaibani, Suliman Alsuhibany; Funding acquisition: Suliman Alsuhaibany; Writing-review & editing: Ali Mustafa Qamar, Rehan Ullah Khan, Mohammed Alsuhaibani, Suliman Alsuhaibany. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qamar, A.M., Khan, R.U., Alsuhaibani, M. et al. Integrating semantic and content features into bloom filters for efficient image retrieval. Sci Rep 15, 44582 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28392-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28392-w