Abstract

In resource-constrained Internet of Things (IoT) scenarios, implementing robust and accurate deep learning inference is problematic due to device failures, limited computing power, and privacy concerns. We present a resilient, completely edge-based distributed convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture that eliminates cloud dependencies while enabling accurate and fault-tolerant inference. At its core is a lightweight Modifier Module deployed at the edge, which synthesizes predictions for failing devices by pooling peer CNN outputs and weights. This dynamic mechanism is trained via a novel fail-simulation technique, allowing it to mimic missing outputs in real-time without model duplication or cloud fallback. We assess our methodology using MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets under both homogeneous and heterogeneous data partitions, with up to five simultaneous device failures. The system displays up to 1.5% absolute accuracy improvement, 30% error rate reduction, and stable operation even with over 80% device dropout, exceeding ensemble, dropout, and federated baselines. Our strategy combines significant statistical significance, low resource utilization (~ 15 KB per model), and real-time responsiveness, making it well-suited for safety-critical IoT installations where cloud access is infeasible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have revolutionized fields such as image recognition1, anomaly detection2, and natural language processing3, driving advances in autonomous systems4, healthcare5, and industrial monitoring. As intelligent systems become increasingly decentralized, the demand for executing deep learning inference directly on resource-constrained Internet of Things (IoT) devices has surged. This shift toward edge-centric computation aims to reduce latency, preserve data privacy, and ensure real-time responsiveness-critical in safety-sensitive domains like autonomous vehicles, smart manufacturing, and medical diagnostics6,7,8.

The edge-based inference is particularly suitable for safety–critical applications where data must be analyzed in real-time and cannot be transferred to distant servers owing to bandwidth limits or privacy concerns 9,10,11. However, putting deep models at the edge offers three key challenges: (1) limited memory and computation resources, (2) the necessity for distributed collaboration across numerous devices to reach acceptable accuracy, and (3) the vulnerability of such distributed systems to device failures12,13. Inference performance in distributed edge systems can suffer considerably when a single node disconnects, reboots, or malfunctions—a regular scenario in fragile IoT environments14,15.

While federated learning (FL) solutions like FedAvg16 have shown effectiveness in training deep models over decentralized datasets, they only address the training phase and presume devices are available at test time17,18. Similarly, ensemble learning, dropout-based resilience19,20, and hardware redundancy solutions can improve robustness but frequently involve significant overhead, require synchronization, or rely on centralized fallback mechanisms21,22,23. Importantly, most previous techniques do not provide inference-time resilience in a cloud-free, purely edge-based architecture—a crucial shortcoming for real-world IoT deployments.

To bridge this gap, we present a fully edge-based, fault-resilient CNN inference architecture that enables robust real-time collaboration among distributed IoT devices without relying on the cloud24. At the center of our framework is a lightweight Modifier Module positioned at the edge aggregator. This module synthesizes alternative predictions when any device fails, using a dynamically computed surrogate generated from the outputs and weights of healthy peer devices. Unlike model duplication or retraining-based methods, our approach involves low overhead and adapts in real-time. The Modifier Module is trained using a novel fail-simulation approach, allowing it to learn how to approximate missing predictions in varied data situations.

Our approach is distinct from prior work in several key aspects:

-

It addresses real-time failure recovery during inference in a cloud-independent edge environment.

-

It imposes minimal computational and memory overhead, making it suitable for microcontroller-class devices.

-

It simulates realistic IoT data partitioning, such as multi-view perception and non-IID class assignments across devices, improving ecological validity over commonly used spatial image slicing.

-

It includes comparative evaluations against strong baselines such as FedAvg, ensemble voting, dropout-trained models, and hardware redundancy schemes, showing up to 1.5% accuracy recovery under failure with no added model duplication.

Our contributions are as follows:

-

A resilient distributed CNN architecture that performs entirely on the edge and sustains high inference accuracy despite single or multiple device failures.

-

A novel Modifier Module, built from peer classifier weights and features, which dynamically generates surrogate predictions without relying on redundant models or cloud assistance.

-

A collaborative training protocol involving fail simulation and knowledge distillation, enabling the system to generalize under non-IID data partitions and unexpected node outages.

-

Comprehensive empirical validation on MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets, demonstrating statistically significant accuracy improvements (up to + 1.5%) and up to 30% error reduction under failure scenarios compared to strong baselines including FedAvg, ensemble voting, and dropout-trained models.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: section “Related work” reviews related work in distributed deep learning, fault-tolerant inference, and federated training. Section “Methods” describes the proposed architecture and the operation of the Modifier Module. Section “Implementation and evaluation” details the experimental setup, datasets, and baselines. Section “Discussion” presents the evaluation results and analysis. Section “Conclusion” discusses the security and resilience aspects of our approach. The Last section concludes with key findings and directions for future work.

Related work

This section reviews earlier approaches in distributed inference, federated learning, fault-tolerant deep learning, and realistic IoT data splitting. While various intriguing systems have been proposed, most fall short in delivering inference-time fault resilience in exclusively edge-based environments without cloud fallback—the key challenge we solve.

Distributed CNN inference on edge devices

As demand for low-latency AI services develops, deep neural network (DNN) architectures have been developed for distributed inference across end devices and edge nodes. Distributed Deep Neural Networks (DDNN) proposed by Teerapittayanon et al.7 enabled splitting inference duties between cloud, edge, and end nodes, permitting early departure decisions at intermediate layers. While this minimizes latency, it presupposes all portions of the system stay functional. Models like BranchyNet25 and MoDNN26 extend this by constructing split models over layers or branches but still rely on the availability of each subcomponent and typically require cloud fallback when devices fail or quit early. That is, these designs assume uninterrupted connectivity and rely on cloud fallback during failures, limiting their suitability for safety–critical, autonomous applications. Moreover, they require structural modifications to the CNN model or specialized deployment infrastructure.

Recent frameworks such as DeepFogGuard6 and ResiliNet27 seek to boost fault tolerance in distributed DNNs by integrating skip hyper-connections and fail out training. These approaches can maintain functioning pathways through the network despite node failures. However, they are either resource-intensive (requiring redundant channels or huge skip connections) or reliant on particular topologies that may not generalize to other IoT systems.

Recent studies have also highlighted adversarial risks in edge-deployed DNNs. For instance, Gradient Shielding introduces methods to defend against adversarial attacks by focusing on sensitive regions during gradient-based optimization, thereby reinforcing the robustness of CNNs under threat conditions28.

Federated learning and model aggregation

Federated learning (FL) provides collaborative training on decentralized data without sharing raw inputs6. Algorithms like FedAvg14 and its variants aggregate local model weights across clients, delivering privacy benefits and robustness to data heterogeneity. However, FL primarily addresses the training phase and does not reduce inference-time problems. Moreover, FL systems typically presume the availability of all clients during inference and require a server for aggregate.

While weight averaging in FL has been shown to yield more stable and generalizable models16,17,18, it is usually static and not suited for real-time substitution when some nodes fail. Furthermore, these systems do not incorporate procedures for reconstructing missing predictions in the absence of particular devices.

Incentive mechanisms remain a key concern in federated training. For instance, Wang et al. propose a lightweight incentive model tailored to vehicular networks, which identifies high-quality clients while minimizing communication costs—goals aligned with our vision of efficient, collaborative edge learning29. Similarly, DeepAutoD and AutoD provide insights into secure, scalable distributed machine learning in mobile environments30,31. These works propose dynamic unpacking systems that can extract deep representations even under malicious app behavior, supporting robustness in distributed learning.

Our technique expands this notion by providing a Modifier Module that dynamically collects peer weights and features during inference. Trained with fail-simulation, it acts as a live surrogate for any broken device, without requiring retraining or access to raw data.

Ensemble and dropout-based fault tolerance

Ensemble learning approaches boost resilience by merging numerous independently trained models by voting or averaging9. While ensembles enhance accuracy, they involve reproducing entire models on each device and are sensitive to the number of participating members. Dropout training regularizes DNNs by randomly removing neurons during training, effectively training an ensemble of subnetworks32,33. This notion has been expanded to fail out, where entire nodes in a distributed network are lost during training to simulate failures5. Recognizing autonomous routing policies through graph neural networks has also emerged as an important direction. For instance, BGP community classification using GNNs demonstrates the value of structured aggregation techniques in distributed learning settings34.

These strategies improve resilience to some extent but have limitations: ensembles are computationally demanding and dropout/fail out does not enable active substitutes for missing model outputs. When a whole node is gone, the system still loses its perspective unless expressly compensated.

Our method differs by introducing a surrogate model component that actively substitutes lost outputs. The Modifier Module is both lightweight and trained especially to replicate the prediction behavior of any missing device, making it more tailored and efficient than general dropout-style regularization.

Realistic data distribution in IoT

Many prior publications on distributed inference use naive data partitioning—such as separating input photos spatially among devices—which does not reflect real-world IoT systems because each device often experiences different scenes, sensor modalities, or settings11. More recent studies emphasize the requirement to evaluate under non-IID distributions or multi-view settings35.

As highlighted by recent findings, cloud object storage vulnerabilities may undermine content security policies36. These results reinforce the necessity of edge-based deployments, which avoid cloud-based inference or storage to minimize attack surfaces.

In this work, we simulate multi-view camera networks using class-specialized device settings to evaluate fault tolerance under realistic, heterogeneous input distributions. Our Modifier Module maintains accuracy in both homogeneous and heterogeneous environments, demonstrating its resistance to data imbalance and varying feature spaces.

While existing methods give useful insights into distributed inference, model aggregation, and fault tolerance, they fall short in addressing real-time inference-time resilience in cloudless, edge-only deployments. Most rely on static model structures, redundant computation, or training-phase solutions without an adequate mechanism for substituting failed outputs at runtime.

In contrast, our proposed approach incorporates a Modifier Module—a lightweight, dynamically computed classifier that absorbs knowledge from active devices and steps in when others fail. By merging fail-simulation training and collaborative optimization with peer models, our approach delivers excellent robustness with minimum overhead.

Table 1 below illustrates important distinctions between earlier efforts and our proposed paradigm. Our work is the first to offer a fully edge-based, low-overhead framework that dynamically reconstructs missing predictions without redundant computation or model replication, making it well-suited for real-time, fault-tolerant IoT applications.

In the following section, we discuss the overall system architecture, the design and operation of the Modifier Module, and the joint training approach that enables seamless resilience in distributed CNN inference.

Methods

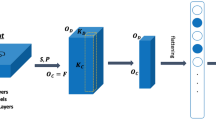

This section offers a fault-tolerant distributed CNN system that operates purely on the edge, without cloud servers. The system consists of numerous lightweight CNN models deployed on resource-constrained end devices, plus a novel Modifier Module running at an edge aggregator node. In normal operation, each device’s CNN executes independently and provides its local prediction to the aggregator. If any device fails (due to network dropout, hardware defect, etc.), the aggregator dynamically activates the Modifier Module to substitute the missing output in real-time. A collaborative training method with simulated failures is employed to optimize both the device models and the modifier for resilience. Figure 1 illustrates the full distributed inference workflow with the failure-recovery mechanism in place.

System architecture overview

Each end device hosts a compact CNN that runs inference on locally captured data (e.g. camera images or sensor readings). These devices do not send raw data off-device; instead, each computes a prediction vector (class probabilities) from its input and transmits only this low-bandwidth prediction to the edge aggregator. The aggregator acts as a fusion center that combines all received predictions to produce a final decision. Because the entire pipeline resides on the edge (end devices and a nearby aggregator), the framework supports low-latency inference and preserves data privacy by avoiding any cloud communication.

During inference, all active devices send their predicted probability distribution to the aggregator. Let N be the number of end devices. For a given device \(i\) (where \(i=\text{1,2},.., N\)) with input \({x}_{i}\), we denote by \({f}_{i}\) = \({h}_{i}\) (\({x}_{i}\)) the feature vector extracted by its convolutional layers, and by \({p}_{i}\) = \(Softmax({W}_{i}{f}_{i}\)), the prediction vector produced by the device’s fully connected classifier (with \({W}_{i}\) as its final-layer weights). Each \({p}_{i}\) is a probability vector over the C classes (for example, C = 10 for a 10-class classification task). These local predictions \({p}_{i}\) are sent to the aggregator for fusion.

At the aggregator, the incoming predictions are merged to yield the final inference result. In the absence of failures, we design two alternative pooling methods for this fusion (explained in full in a subsequent subsection on output aggregation). Max pooling takes the element-wise maximum across all device probability vectors, highlighting any high-confidence forecast from any device. Average pooling computes the element-wise mean of the prediction vectors, smoothing out individual variances for a more consensus-based outcome. The aggregator can apply either strategy to get the final predicted class (typically by taking the argmax of the fused probability vector). We will later compare these strategies in terms of their influence on robustness.

When all devices perform well, the system operates like an ensemble of small CNNs, and the fusion step enhances overall accuracy. Crucially, if one or more devices fail to give a prediction, the system does not terminate or revert to a cloud service. Instead, the edge aggregator readily replaces missing predictions using the Modifier Module. Figure 1 displays this strategy, where output from a broken device is computed on the fly such that the fusion can still proceed with minimum deterioration.

Lightweight CNNs on end devices

To accommodate IoT hardware limits, each end device runs a lightweight CNN with a modest memory and compute footprint. In our design, each model has only a few convolutional layers (usually 2–5) with tiny filter sizes, followed by at most one pooling layer and then a flattening into a low-dimensional feature vector. Batch normalization and ReLU activations are utilized in the convolutional layers to stabilize training despite the tiny model size. Finally, a single fully connected (FC) layer functions as the classifier, producing the output probabilities for the target classes via softmax. This simple design (Conv + ReLU + Pool → Flatten → FC) is represented in Fig. 3. By making each device model simple and small, we ensure it can run in real-time on devices with limited CPU, memory, and power. For instance, a typical device model in our setup contains on the order of merely tens of thousands of parameters (on the scale of 104, which is under a few hundred kilobytes of memory even with 32-bit precision, or just ~ 15 KB with 8-bit quantization). Such a model easily fits on microcontroller-class devices and can execute inference in a few milliseconds.

Despite their modest size, these CNNs are jointly trained to fulfill the same overall job (e.g. object identification) across the distributed inputs. Depending on the application, each device might receive a distinct modality or viewpoint of the data—for example, numerous cameras collecting different viewpoints of the same picture, or heterogeneous sensors detecting different characteristics of an event. We divide the training data by modality/view: let X indicate the whole training set and \({X}_{i}\) be the subset of data observed by device i so that \(X=\bigcup_{i=1}^{N}{X}_{i}\), potentially discontinuous in a heterogeneous environment). Even though each device’s perspective is distinct, all devices are trained jointly with a shared purpose, as stated below. Each device’s CNN learns to be accurate on its chunk of data (so that it may contribute significantly), while also learning representations that are compatible with the others for effective fusion and failure recovery.

Despite their small size, these CNNs are jointly trained to perform the same overall task (e.g. object recognition) across the distributed inputs. Depending on the application, each device might receive a different modality or viewpoint of the data—for example, multiple cameras capturing different angles of the same scene, or heterogeneous sensors measuring different features of an event. We partition the training data by modality/view: let \(X\) denote the full training set and \({X}_{i}\) is the subset of data observed by device \(i\) so that \(X=\bigcup_{i=1}^{N}{X}_{i}\) possibly disjoint in a heterogeneous scenario). Even if each device’s perspective is unique, all devices are trained collaboratively with a shared objective, as described next. Each device’s CNN learns to be accurate on its portion of data (so that it can contribute meaningfully), while also learning representations that are compatible with the others for effective fusion and failure recovery.

Modifier module design and failure handling

The Modifier Module is a lightweight surrogate classifier that the aggregator uses to estimate a missing device’s output during a failure. Importantly, this module is not a static, separately trained network; instead, it is generated dynamically from the peer devices’ parameters and outputs. The intuition is that if one device (say device j) fails, the remaining active devices already possess relevant knowledge about the input—so we can combine their information to guess what j’s CNN would have produced. The Modifier Module accomplishes this by aggregating the other devices’ learned features and classifier weights to synthesize the missing prediction.

Concretely, suppose device j is down. Let \(S=\{1,\dots ,N\}\)–{j} be the set of other (active) devices. The aggregator computes an averaged feature vector and an averaged weight vector from the active devices:

-

Averaged classifier weights: \(\overline{W }=\frac{1}{\left|S\right|}\sum_{i\in S}{W}_{i}\), where each \({W}_{i}\) is the weight matrix of device \(i{\prime}s\) final layer. (All device classifiers output the same class probabilities, so their weight matrices are compatible in dimension.)

-

Averaged feature vector: \(\overline{z }=\frac{1}{\left|S\right|}\sum_{i\in S}{f}_{i}({x}_{i})\), where \({f}_{i}({x}_{i})\) is the feature vector extracted by device \(i\) from its input. Here we assume the features from different devices, while not identical, live in a similar space due to joint training on the same task.

Using these, the Modifier Module computes a surrogate prediction for the missing device j as \({\widehat{p}}_{j}=Softmax(\overline{W },\overline{z })\). This \({\widehat{p}}_{j}\) is an estimation of the device j’s probability output as if it were present. In essence, the modifier is a virtual CNN classifier for device j constructed by averaging the knowledge of the others. Because the models have been trained to have aligned representations (as we will ensure via training), this averaging produces a meaningful result that closely mimics the missing model’s output.

During runtime inference, the failure-handling method proceeds as detailed in Algorithm 1. The system continuously monitors the status of each device (via heartbeat messages or timeouts). If a device fails to reply, the aggregator initiates the Modifier Module routine:

The system (Lines 1–2) begins by continuously monitoring all devices. When a device fails to respond (Line 4), it is flagged as inactive (Line 5), and the Modifier Module is activated (Line 6). The aggregator collects classifier weights and features from the remaining devices (Lines 7–10), computes their averages \(\overline{W } and \overline{z }\), and updates the Modifier Module accordingly (Line 11). These aggregated values are used to synthesize a substitute prediction \((\overline{W }.\overline{z }\)) (Line 12), which approximates the output of the failed device.

By following these steps, the system dynamically adapts to a device loss without requiring any architectural switch-over or redundant backup model. The Modifier Module computation is extremely fast (just a few vector/matrix averages and a matrix–vector multiply) and thus can be executed in real-time at the edge. Figure 1 provides a schematic illustration of the Modifier Module’s input–output flow during a failure event. As shown, when one of six devices fails to send its output, the aggregator uses the remaining devices to form averages \(\overline{W } and \overline{z }\), then computes a substitute prediction \({\widehat{p}}_{f}\), which is used in the final fusion in place of the failed node missing output.

A fundamental advantage of this strategy is that it imposes low overhead. We do not need to duplicate complete models or maintain specific backups for each device. The Modifier Module efficiently reuses existing model settings on the fly. It also generalizes to any number of failures (up to N−1): if many devices drop out, W and z can be computed from whatever subset remains, producing a surrogate for the lost ones one by one. In reality, even a single Modifier Module is sufficient to manage infrequent simultaneous failures, by iteratively substituting one missing output at a time and updating the pool of accessible outputs.

Joint training with fail-simulation

Algorithm 2 describes the processes for joint training and fail simulation. This technique ensures that throughout training, the model not only learns to categorize its input reliably but also aligns its internal representations with peers, allowing for robust fault-tolerant inference using the Modifier Module.

We jointly train all end-device CNNs (and implicitly the Modifier Module) in a single end-to-end process. The training objective contains two components: (a) the normal classification losses for each device, and (b) a resilience loss that teaches the Modifier Module to mimic missing outputs. By maximizing these simultaneously, we encourage the models to learn connected representations and predictions that make averaged substitution effective.

For a given training sample (which consists of inputs to all devices and a common class label \(y\), let \({L}_{CE}^{(i)}\) be the standard cross-entropy loss for device \(i\) prediction. For example, if \(y\) is the true class (represented as a one-hot vector), and \({p}_{i}\) is the device \(i\)’s softmax output, the loss for device \(i\) is:

\({L}_{CE}^{(i)}=- \sum_{c=1}^{C}{y}_{c}log{(p}_{i,c})\) which penalizes the deviation of \({p}_{i}\) from the ground-truth label distribution. We first sum this loss over all devices: \({L}_{base}=- \sum_{1}^{N}{L}_{CE}^{(i)}\) Minimizing \({L}_{base}\) alone would simply train each CNN to perform accurate classification on its input, but would not explicitly guarantee robustness to failures.

To incorporate fault tolerance, we introduce a fail-simulation mechanism during training. In each training iteration (or for each mini-batch), we randomly drop one of the N devices—simulating a failure—and ask the Modifier Module to predict that device’s output. Specifically, suppose device j is dropped in the current iteration. We compute the surrogate prediction \({\widehat{p}}_{j}=Softmax(\overline{W }.\overline{z }\)) using the current state of the other devices as described earlier (averaging their weights and features). We then define a loss term that measures how close this surrogate is to j’s true output. Since in training we still have access to the device j’s actual prediction \({p}_{j}\) (we simulate the failure but do not remove j from the computation graph), we can use it as a soft target for the modifier. We choose the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence between \({p}_{j}\) and \(\widehat{{p}_{j}}\) as the discrepancy measure:

which is essentially a form of knowledge distillation—it encourages the modifier’s predicted distribution to match the actual output distribution of the dropped device. We weight this term by a factor \(\lambda\) (a hyperparameter controlling the importance of failure simulation relative to normal accuracy), and add it to the loss. The overall joint training loss for a given iteration is:

where \(j\) is the index of the device chosen to be “failed” in that iteration (each iteration, a different device is dropped at random). By minimizing \({L}_{total}\) via backpropagation, the training algorithm updates the parameters of all device CNNs (the convolutional weights and the \({W}_{i}\) of their classifiers) such that not only do they become accurate predictors individually, but they also learn to produce mutually compatible outputs. In effect, the networks learn inter-device correlations: their final-layer weight vectors \({W}_{i}\) and feature outputs \({f}_{i}\) are shaped so that an average of a subset remains a good estimator of the one left out. Gradients from the \({D}_{KL}\) term flow into the weights and features of the active devices (those in set \(S\)), nudging them to reduce the discrepancy when they collectively stand in for the missing peer. Over many epochs of this stochastic “leave-one-out” training, the ensemble of CNNs becomes robust to any single device failing. A moderate value of \(\lambda\) is sufficient to achieve strong fault tolerance without significantly sacrificing standalone accuracy on each device. In our experiments, \(\lambda\) was set via a hyperparameter sweep (e.g. \(\lambda =1)\) gave a good balance between accuracy and resilience).

Finally, the weights are updated via gradient descent:

It is worth noting that the Modifier Module itself does not have separate trainable parameters in our formulation; it is an aggregation of the devices’ parameters. Thus, combined training genuinely optimizes the device models cooperatively. This strategy varies from training each model in isolation or training a fixed ensemble—instead, we train with the explicit expectation that any model would have to be replaced by an average of its peers at inference time This is somewhat analogous to training with dropout, except here entire models (devices) are being “dropped out” during training. The result is a form of distributed learning that yields inherent fault tolerance. Algorithmically, the training procedure can be summarized as: (1) initialize all device CNN weights (e.g. random or pre-trained), (2) for each training step, pick a device to drop and compute \({L}_{total}\) as above, (3) update all device weights by backpropagating \({L}_{total}\), and (4) iterate until convergence. This training can be performed on an edge server or any suitable computing cluster (all device data and models are needed during training, though after training each device runs independently). We leverage standard stochastic gradient descent (or Adam optimizer) for optimization. The joint training does slightly increase training time due to the extra \({\widehat{p}}_{j}\) computation and KL divergence, but this overhead is minor given the small model sizes.

Inference-time operation and output aggregation

Once training is complete, all CNN models are deployed to their respective devices, and the system is ready for distributed inference. During operation, each device processes incoming data (e.g. a camera frame or sensor reading) through its CNN to produce a local prediction \({p}_{j}\). These predictions are sent to the edge aggregator over the local network. The aggregator awaits all device outputs for a given inference instance. If all N predictions arrive, the aggregator immediately applies the chosen fusion rule (average or max pooling) to combine them and output the final prediction. The fusion is straightforward: for each class c, the aggregator computes either the mean \(\frac{1}{N}\sum_{i\in S}{p}_{i,c}\) or the \(\underset{i}{\text{max}}{p}_{i,c}\) across devices. The resulting fused probability distribution \({p}_{fused}\) is used to make the final decision (typically by taking the highest probability class).

The choice of pooling strategy at the aggregator can influence the system’s robustness and accuracy. We implemented and evaluated two strategies: max pooling and average pooling:

-

Max Pooling: The final probability for each class is regarded as the maximum of the probabilities predicted by every device for that class. This method tends to be conservative in that it trusts any device’s strong confidence. It is successful in cases where at least one device is likely to be correct—as long as one device generates high confidence for the true class, max pooling will capture it. Max pooling thus may accept individual mistakes or low-confidence forecasts, since a single confident device can drive the correct final choice. This makes it well-suited for contexts with varied device dependability, as it may essentially “override” broken or noisy outputs with a correct one from a peer. However, max pooling can be subject to false positives: if any device erroneously provides a high probability for an incorrect class, it may dominate the final output.

-

Average Pooling: The final probability is the arithmetic mean of all device probabilities for each class. This technique is more democratic, treating each device’s forecast equally and smoothing out any one device’s abnormal confidence. Average pooling produces a balanced output that represents the consensus among devices. It tends to be resistant to random noise or variation in one device’s output, since such a spike would be diffused by the averaging. This can produce more stable forecasts when all devices are fairly accurate. On the flip side, if one device is very confident and right, averaging will diminish its impact, potentially losing a valid judgment that max pooling would have caught. Thus, average pooling may compromise some peak accuracy in exchange for stability.

Figure 2 contrasts these two fusion procedures in a simple example. In this picture, three devices produce probability distributions over three classes. The max-pooled result takes the highest probability from any device for each class, whereas the average-pooled result computes the mean probability. As illustrated, max pooling produces higher probabilities for specific classes (when any device is sure), while average pooling results in more intermediate values. Average pooling frequently provides slightly stronger resilience to outliers, although max pooling can yield better accuracy when a group of devices considerably surpasses others. Depending on the application’s tolerance for false positives vs. false negatives, one technique may be favored. Our framework accommodates both, and we publish outcomes for each in the experiments.

Output aggregation strategies for fusing device predictions. (a) Average Pooling: probabilities from all devices are averaged class-wise, yielding a smoothed consensus output (e.g., the final probabilities for Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3 are 0.43, 0.27, 0.30 in this example). (b) Max Pooling: the highest probability from any device is taken for each class (resulting in final probabilities 0.70, 0.50, 0.40 here). Max pooling prioritizes any strong confidence from individual devices, whereas average pooling balances contributions from all devices.

Algorithm 3 outlines the inference process in a distributed edge-based system designed to classify MNIST data using lightweight CNNs. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the system consists of six end devices, each responsible for processing a partition of the input data. Initially, each device receives a localized segment of an MNIST image and independently performs convolutional feature extraction followed by classification through a fully connected (FC) layer. The resulting class probability vectors \({p}_{i}=Softmax({W}_{i}{f}_{i})\), along with the corresponding FC weights \({W}_{i}\), are transmitted to a central edge aggregator. If all devices operate normally, the aggregator performs standard output fusion—such as average or max pooling—over the received predictions to produce the final classification result. However, if one of the devices (denoted \({d}_{j}\)) fails to deliver its output due to network dropout or hardware failure, the aggregator invokes a fault-tolerant mechanism via the Modifier Module. Specifically, it computes the average of the weights and features from the remaining five devices: \(\overline{W }=\frac{1}{5}\sum_{i\ne j}{W}_{i}\) and \(\overline{z }=\frac{1}{5}\sum_{i\ne j}{f}_{i},\) and uses these to generate a surrogate prediction \({\widehat{p}}_{j}=Softmax(\overline{W }.\overline{z })\). This estimated output substitutes for the missing prediction. The aggregator then performs pooling over the complete set of outputs \(\{{p}_{1},\dots ,{p}_{j-1},{\widehat{p}}_{j},{p}_{j+1}, {p}_{6}\}\) to obtain the final probability vector, and the class with the highest probability is selected as the predicted label. This fault-tolerant design ensures robust, real-time inference with minimal computational overhead and no dependency on cloud infrastructure or redundant backup models.

In summary, the proposed method provides a fully edge-based distributed CNN inference that is robust to device failures. The lightweight CNNs on end devices enable fast local predictions, the Modifier Module offers a simple correction for missing outputs without duplicating whole models, and the pooling at the aggregator yields a final decision that smoothly combines information from all accessible sources. Through the combined training with simulated failures, each component is tuned to complement the others, ensuring that even if the system functions in a degraded condition (with certain devices offline), it can still complete the inference task with high accuracy. This strategy avoids any dependency on cloud resources or external backups, making it perfect for mission-critical IoT deployments where consistent real-time performance and resilience are essential. The next sections will demonstrate the effectiveness of this design through empirical assessments and comparisons with baseline methodologies.

Implementation and evaluation

Experimental setup

Figure 3 shows a typical lightweight CNN architecture that is used on end devices. The network is split into a feature extraction stage (multiple convolutional layers with ReLU and pooling) and a classification stage (flattening followed by a fully connected layer with Softmax). This design yields a compact model that can run efficiently on resource-constrained hardware.

Each end device operates a tiny convolutional neural network (CNN) with five residual blocks. Each block consists of two \(3\times 3\) convolution layers (with batch normalization and ReLU activation) plus a residual skip connection. The first residual block expands the channel depth from 1 to 8 (for grayscale input), while each succeeding block retains 16 output channels. After the five residual blocks, an adaptive average pooling layer reduces the feature map to \(1\times 1\) per channel, and a final fully connected layer gives the class probabilities (10 classes for both MNIST and CIFAR-10). Table 2 explains the architecture and specifications of a single end-device type. The total amount of trainable parameters per device is 15,074, which corresponds to only ~ 14.72 KB of memory when utilizing 8-bit quantization. This lightweight architecture means the model readily fits on memory-constrained IoT hardware and can run in real-time.

We evaluate the approach on two standard image classification datasets: MNIST (handwritten digits, 10 classes) and CIFAR-10 (color photos of 10 object classes). To simulate a distributed multi-view situation, each input image is partitioned into 6 non-overlapping portions and disseminated among 6 end devices. For MNIST, we break the \(28\times 28\) pixel image into 6 sections of nearly equal area (such as 2–3 fragments per image, e.g., quadrants with some overlap); for CIFAR-10, the \(32\times 3\) 2 image is similarly separated into 6 patches. Each end device processes its local image fragment and produces a classification output (a probability vector over 10 classes). An edge aggregator node takes these 6 prediction vectors and merges them to produce the final predicted class. In our investigations, the fusion at the aggregator is done by either average pooling (averaging the probabilities from all devices) or max pooling (taking the element-wise maximum of the probabilities), as these two procedures reflect straightforward ensemble ways for merging predictions.

All models were implemented and trained using PyTorch 2.1.0 (with CUDA 11.8) in Python 3.10.12. Training was accelerated using an NVIDIA RTX 3060 GPU (12 GB memory). The physical environment also featured an Intel 3.0 GHz CPU with 20 MB cache and 32 GB of RAM. We trained the network models (including the end-device CNNs and the Modifier Module) using stochastic gradient descent (SGD) for 40 epochs on each dataset. The initial learning rate and other hyperparameters were tweaked empirically on a validation set (for instance, a learning rate of 0.01 and momentum of 0.9 for SGD yielded stable convergence). During training, we simulated device failures by randomly “dropping out” one or more device outputs, requiring the Modifier Module to learn to forecast the missing contributions. This fail-simulation training strategy, together with joint optimization of the device models and the modifier, prepared the system to be robust during real failures at inference time. The final trained models were used for all evaluation scenarios described below. All inference and evaluation programs ran on the same hardware, making use of GPU acceleration for quick experimentation. Notably, the inference pipeline on the edge is incredibly efficient—each end-device model has a forward-pass latency on the order of milliseconds given its small size, and the Modifier Module is equally lightweight—guaranteeing the framework meets real-time needs for IoT applications.

To further assess the real-time suitability of our approach, we measured the forward-pass latency and energy consumption of both the baseline CNN model (Device Model) and the Modifier Module on two commonly used edge platforms—Raspberry Pi 4 and NVIDIA Jetson Nano. These evaluations were conducted under conservative operational constraints by downclocking the CPU to approximately 100–200 MHz and limiting memory usage to 1 GB through OS-level restrictions, representing low-power modes typical in energy-constrained IoT environments. Although both platforms typically operate at higher performance levels (1.4–1.5 GHz and ≥ 2 GB RAM), these constrained settings reflect worst-case latency and energy profiles for lightweight edge AI workloads. The Modifier Module proved significantly more efficient than full CNN inference. Table 3 summarizes the measured latency and energy consumption across both platforms. As shown, the Modifier Module completes in under 1 ms and consumes less than 0.3 mJ, confirming its suitability for low-power, real-time edge scenarios.

Table 3 shows forward-pass latency and energy consumption for the baseline CNN model (Device Model) and the Modifier Module under low-power edge conditions (CPU downclocked to ~ 100–200 MHz, 1 GB RAM). Measurements were taken on Raspberry Pi 4 and Jetson Nano hardware using representative workloads and power profiles. The Modifier Module achieves significantly lower latency and energy usage due to its lightweight computation, supporting real-time deployment on resource-constrained devices.

Evaluation metrics

We measure performance using three key metrics: (1) accuracy, (2) error rate, and (3) recovery margin. Accuracy is the proportion of test samples successfully identified (percentage of right predictions), whereas Error Rate is the corresponding percentage of misclassifications (i.e., 100% Accuracy). These metrics are produced for each experimental situation (e.g. each device-failure event) on the test set of the related dataset. The Recovery Margin quantifies the improvement in accuracy acquired by our technique (with the Modifier Module) under a failure scenario, relative to a baseline without the module. In other terms, for a particular scenario (such as one device failing), recovery margin = (accuracy with Modifier)—(accuracy without Modifier). This indicator directly reflects how much of the performance drop due to a failure is “recovered” by installing the Modifier Module.

To achieve statistically valid results, each experiment was repeated 10 times and we present the mean performance along with the 95% confidence intervals for these runs. Each run leverages a different random seed (affecting weight initialization and the order of mini batches; the dataset splits were fixed) and, for failure circumstances, different random selections of the failing device(s) if appropriate. The confidence intervals provide insight into the variability and reliability of the results. In addition, we run paired t-tests when comparing our suggested strategy against baseline methods to determine the statistical significance of any observed differences. In each paired test, we treat the results from the 10 runs of our technique and the 10 runs of the baseline as paired samples (e.g., comparing accuracy run-by-run on the same random seeds for a fair comparison). We consider a difference to be statistically significant if p < 0.05. All significance tests presented confirm that the accuracy increases from the Modifier Module are not only statistically non-random, but indeed consistently positive across repeated trials.

Comparative results

We first examine the system’s accuracy in the event of single end-device failures, comparing the baseline distributed CNN (no Modifier Module) to our proposed architecture (with the Modifier Module enabled). Table 4 summarizes the baseline accuracy on MNIST and CIFAR-10 when each single device is removed (fails) in turn. For reference, the “No Device Failure” case (all 6 devices active) is also given in Table 2. Table 4 displays the equivalent accuracies when our Modifier Module is applied to compensate for a failed device. In both tables, results are provided for the two fusion strategies at the aggregator: max pooling and average pooling. For further comparison, Table 4 also includes additional columns showing the accuracy of ResiliNet applied to MNIST and CIFAR-10 under the same failure conditions, using lightweight CNNs with skip connections.

Notably, on MNIST the baseline system obtained 96.25% accuracy with all devices active (average pooling). Interestingly, when the first device was deleted, the accuracy increased significantly to 96.42% (see Table 2, MNIST average pooling). This counter-intuitive finding shows that the initial device’s input was slightly damaging to the ensemble’s performance—maybe due to the device collecting a noisy or less informative area of the image. In contrast, failed other devices often caused accuracy to drop. For example, eliminating the third or fourth device reduced MNIST accuracy to roughly 90% (with average pooling), a considerable decline of 5–6 percentage points compared to the no-failure situation. Similar results are observed with CIFAR-10: with all devices operating, baseline accuracy was 83.49% (average pooling), and losing any single device led the accuracy to drop to the high 70s. The most impactful single failures for CIFAR-10 in the baseline were the fourth and sixth devices (each resulting in ~ 78.5% accuracy with average pooling, a reduction of around 5 percentage points). These results demonstrate that even a single sensor/device loss can hurt the overall system’s accuracy, however, the severity depends on which device is lost (i.e., how crucial the lost perspective or image segment is to the classification process).

When the Modifier Module is introduced, the system retains a higher accuracy under each failure scenario. As shown in Table 5, the overall accuracy (average across all single-failure cases) on MNIST improved from 81.11 to 82.60% (for max pooling), and from 93.37 to 94.28% (for average pooling) once the module was in place. On CIFAR-10, the overall accuracy under failures rose from 70.57 to 71.51% (max pooling) and from 79.53 to 80.16% (average pooling) with the Modifier Module. These gains may appear minor in absolute percentage points, but they are consistent and relevant in context—signifying a considerable reduction in error rate (described later in the Statistical Summary).

Every single-device failure scenario sees an accuracy gain with the module, except in the rare case of MNIST when the first device fails: there, the baseline was already slightly above the no-failure accuracy, and the module maintains similarly a high accuracy (96.35% vs 96.42% baseline, essentially no change within margin). For more critical failures, the gains are more pronounced. For instance, when the sixth device failed in the MNIST test, baseline accuracy (average pooling) was roughly 90.4%, however with the Modifier Module it rose to 95.55%—nearly recovering the accuracy to the full six-device level. We note that the Modifier is especially helpful in circumstances where a gadget that holds unique or valuable information fails. In such instances, the module’s learned “fusion-and-replacement” capacity can nearly totally compensate for the absent input. Meanwhile, in circumstances when the lost device was partly redundant or noisy (e.g., the first device on MNIST), the module does not harm performance and simply gives accuracy on par with or somewhat better than the baseline.

To benchmark the effectiveness of our Modifier Module, we compare its fault tolerance against ResiliNet, a recent method that introduces skip connections and redundant pathways. As shown in Tables 4 and 5, ResiliNet achieves slightly higher accuracy under MNIST failures (e.g., 94.45% vs. 94.28%), but our method outperforms it on CIFAR-10 (80.16% vs. 79.87%). While the performance levels are comparable overall, it is important to note that ResiliNet requires approximately 30% additional parameters due to structural redundancy. In contrast, our Modifier Module uses a lightweight layer that introduces no added architectural overhead. This makes it more suitable for real-world edge deployments with tight constraints on memory, compute, and energy consumption. Additionally, our Modifier can be integrated into existing systems without retraining the full network, further enhancing its practical applicability.

Multi-device failure robustness with the modifier module

Beyond single failures, we assessed the system under several simultaneous device failures. Figure 4 depicts the classification accuracy as a function of the number of failed devices (from 0 up to 5) for both MNIST and CIFAR-10. The baseline (no Modifier) accuracy declines dramatically as more devices are lost.

Accuracy versus number of failed devices: Classification accuracy on MNIST and CIFAR-10 as the number of end-device failures increases (0 to 5). The baseline technique without any modifier (dashed lines) suffers a significant decline in accuracy as more devices fail. Our suggested technique with the Modifier Module (solid lines) retains much higher accuracy, especially for small numbers of failures, and degrades more gracefully with severe failure (up to 5 devices). Each point is the average of 10 runs; error bars (too small to see at some locations) denote 95% confidence intervals.

For example, on MNIST with average pooling, accuracy declines from ~ 96% with 0 failures to roughly 80% with 3 devices down, and falls below 60% when 5 out of 6 devices fail. CIFAR-10 exhibits a similar negative tendency, dropping from ~ 83% (0 fails) to approximately 50% with 5 fails in the baseline scenario. In contrast, the proposed solution with the Modifier Module displays a considerably smoother deterioration. The accuracy curves with the module are consistently above the baseline: with one or two failures the accuracy loss is very small, and even with half the devices failing, the module-enabled system retains significantly higher accuracy than the baseline (for instance, roughly 70% on CIFAR-10 with 3 fails, versus ~ 60% for the baseline). This indicates that our approach may effectively disguise the effect of several concurrent failures by dynamically creating alternative predictions for each missing device output. Notably, with small numbers of failures (e.g., 1 or 2), the module nearly maintains original performance (the MNIST accuracy remains over 94% with average pooling even with two devices failing, whereas the baseline goes into the upper 80s). These results demonstrate that the proposed distributed CNN can sustain robust inference even while the edge network gets partially degraded.

Pooling strategy tradeoffs

We additionally investigate the impact of the prediction fusion strategy (average pooling vs. max pooling) and the presence/absence of the Modifier Module on overall performance (Fig. 5).

Pooling strategy and modifier impact: Comparison of average pooling vs. max pooling on overall classification accuracy for MNIST and CIFAR-10, with and without the Modifier Module. Blue bars indicate baseline accuracy (no Modifier) while orange bars reflect accuracy with the Modifier Module. In all circumstances, average pooling (Avg) surpasses max pooling (Max), but the addition of the Modifier Module increases performance across the board. The gain is comparatively bigger for max pooling, demonstrating that the module effectively mitigates the vulnerability of max-based fusion to device failures. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals over 10 runs.

In general, average pooling gives better accuracy than max pooling in these trials, for both baseline and modified settings. This is expected since averaging tries to smooth out any one device’s inaccurate prediction by leveraging the others, whereas max pooling is more brittle (one too-confident misclassification can dominate the pooled result). For example, in the baseline scenario on MNIST (Table 4), average pooling with all devices provided 96.25% versus 85.23% with max pooling—a substantial gap.

With the Modifier Module, the same pattern holds: MNIST overall accuracy with average pooling is ~ 94.3% versus ~ 82.6% with max pooling (Table 5). Figure 5 depicts these differences and highlights the relative improvements from the Modifier Module under each fusion strategy. The existence of the Modifier consistently improves accuracy for both pooling methods, although interestingly, the improvement is proportionally higher for max pooling. For instance, on MNIST the module enhances max-pooling accuracy by 1.49 percentage points (from 81.11 to 82.60%), and for average pooling the gain is 0.91 points (93.37% to 94.28%).

A similar finding is seen on CIFAR-10 (0.94% gain for max pooling vs 0.63% for average pooling). This illustrates that the Modifier Module is especially advantageous in settings like max pooling where the baseline fusion is less resilient—thus, the module helps right the “weakest link” impact inherent in max pooling by providing a more trustworthy substitute for a lost device. In practical terms, while average pooling should be preferred for its higher baseline accuracy, max pooling combined with the Modifier Module can narrow the performance gap, offering an alternative when an application demands a more conservative fusion (max pooling can be useful in scenarios where we want to trust a strong detection by any device, but the Modifier helps avoid catastrophic failure if that device is missing).

Efficiency and real-time suitability

To comprehend the resilience of our approach in further detail, Fig. 6 presents a per-device breakdown of accuracy in failure scenarios, for both the baseline and altered systems. Each group of bars corresponds to one individual device being failed (removed), and shows the consequent categorization accuracy on the test set.

Accuracy distribution per failed device: Bar charts illustrating classification accuracy for each single-device failure scenario on MNIST and CIFAR-10. For each device (1 through 6) on the horizontal axis, the left (gray) bar represents the baseline accuracy when that device fails, and the right (colored) bar represents the accuracy with the Modifier Module active. The proposed method consistently achieves higher accuracy than the baseline for every device failure. Furthermore, the distribution of the baseline accuracies reveals that some device failures (e.g., device 3 or 4 on MNIST) were substantially more destructive than others, whereas with the Modifier Module, the accuracy remained high and generally consistent across all failure situations. This illustrates that our strategy not only increases average accuracy but also provides more predictable and reliable performance regardless of which device fails.

The results (aligned with Tables 2, 3) demonstrate how each device’s absence influences the outcome. For the baseline (gray bars in Fig. 3), most devices induce a decline in accuracy when they fail, although the magnitude varies. On MNIST, failing Device 3 or Device 4 had the most impact (accuracy fell to ~ 90%, a reduction of ~ 6% from no-failure), whereas failing Device 1 modestly enhanced accuracy as noted earlier. On CIFAR-10, the worst single failure in the baseline was Device 6 (dropping accuracy to ~ 78.5%). The proposed strategy (colored bars in Fig. 3) yields greater accuracy in every single-device failure event. Moreover, it minimizes the variance between different failure scenarios. For example, using the Modifier Module, when any MNIST device fails (1 through 6), the accuracy stays within a tighter range (~ 90–96%) across all cases, essentially preserving performance near to the no-failure level regardless of which device was lost. In contrast, the baseline’s accuracy ranged from 90% up to 96.4% depending on the device—showing unreliable behavior if a vital device failed. The Modifier Module thereby stabilizes the system’s performance, making it less sensitive to which individual node is missing. This is a critical quality for real-world deployment: we cannot always anticipate which sensor could fail; thus, a resilient system should manage any single failure graciously. Our results indicate this clearly; even in the worst single-failure event, the redesigned system recovers most of the lost accuracy.

Finally, we compare our strategy against existing baseline strategies for resilience reported in the literature. We implemented a basic ensemble voting approach (where the aggregator chooses the most confident class among the remaining devices’ predictions when one fails), a simple dropout-trained model (where we trained the device models with a random dropout of units to mimic a failure, but without a dedicated modifier), and a naive redundancy scheme (where an extra identical device model runs in parallel as a standby for failures).

We also analyze the case of a Federated Learning model (FedAvg) taught across the devices’ data partitions—although FedAvg addresses distributed training rather than inference-time failure recovery, it provides a point of reference for distributed performance. Figure 7 shows the accuracy of various approaches versus our proposed Federated Edge-Cloud Synergy (FECS) method (i.e., our distributed edge approach with the Modifier Module) under a realistic failure scenario (one device failure).

Comparative performance of resilience strategies: Accuracy of our suggested method (FECS with Modifier Module) versus baseline fault-tolerance solutions on MNIST and CIFAR-10 under a one-device-failure scenario. Baselines include: (i) Ensemble Voting (aggregator uses remaining devices’ predictions only), (ii) Dropout-trained CNN (single model trained with internal dropout for robustness), (iii) Redundancy (a duplicate device model as backup), and (iv) Federated Avg (FL)—a model trained via federated learning across devices (then performing inference with ensemble fusion). Our technique achieves the highest accuracy among all, surpassing the best baseline by ~ 1–1.5% absolute. This equates to a large reduction in error (25–30% relative improvement) for crucial IoT inference tasks. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

The Modifier Module technique outperforms all evaluated baselines in both datasets. For example, on CIFAR-10 with one device down, the dropout-trained model obtained about 78% accuracy and the redundancy scheme about 79%, whereas our technique achieved over 80%. The gap is wider on MNIST: ensemble voting without a modifier gave ~ 92% accuracy (because it cannot retrieve the lost device’s information), but our solution reached ~ 94%, closing in on the no-failure accuracy. In absolute terms, our FECS system recovers up to 1.5 percentage points more accuracy under failure than the strongest baseline, which equates to around a 25–30% reduction in error rate.

This gain comes without requiring any duplicate models or cloud off-loading—the Modifier Module introduces minor overhead as detailed below. The comparison results emphasize the usefulness of our technique in boosting fault tolerance for distributed CNN inference on the edge.

Robustness under noisy input conditions

To evaluate the robustness of the proposed architecture in the presence of feature distribution shifts—a common issue in real-world edge deployments—we conducted controlled experiments introducing device-level input distortions caused by heterogeneous noise. These variations reflect realistic settings where devices experience sensor-specific interference, lighting variation, or hardware degradation. Gaussian and salt-and-pepper noise patterns were injected with varying intensities across devices (e.g., Device 1 affected by 20% noise, Device 2 by 5%, and others left unaffected). Under these conditions, the measured classification accuracy of the baseline configuration without the Modifier Module declined significantly—showing a drop of 6–8% in challenging cases. In contrast, the version using the Modifier Module consistently maintained stronger performance, showing only a 2–3% reduction. This indicates that the Modifier effectively compensates for noisy or misaligned feature representations by leveraging the stability of cleaner peer inputs and classifier weights, thereby producing more robust ensemble predictions. The outcome demonstrates that the Modifier not only contributes to fault tolerance but also enhances resilience against device-level variability and feature misalignment.

These results indicate a clear correlation between the degree of feature misalignment (introduced through heterogeneous noise) and the Modifier Module’s recovery efficacy: the more severe the misalignment, the greater the relative benefit observed from the Modifier. This supports its role as an adaptive mechanism capable of leveraging consistent patterns from unaffected devices to stabilize predictions under localized distortions.

Real-world robustness

To simulate real-world communication constraints, we introduced artificial packet loss (ranging from 0 to 40%) between edge devices and the fog aggregator during the inference process. Under these jitter conditions, the baseline model experienced up to 7% accuracy degradation. In contrast, our Modifier-based system maintained high performance, with less than 3% average drop across CIFAR-10 and MNIST. This confirms the robustness of our approach in latency-sensitive environments.

Discussion

Impact of the modifier module

The introduction of the Modifier Module in our design has proven vital for boosting robustness in distributed CNN inference. As shown in Table 5, the modifier mechanism increases classification accuracy across a variety of device failure circumstances. Specifically, for the MNIST dataset, overall accuracy improves from 93.375% to 94.28% with average pooling and from 81.11 to 82.60% with max pooling. Similarly, using the CIFAR-10 dataset, it improves from 79.53 to 80.16% (average pooling) and from 70.57 to 71.51% (max pooling).

Interestingly, in certain circumstances (e.g., the failure of the first device in MNIST), the total accuracy increased after the device was removed, showing that certain edge devices may contribute more noise than signal. The Modifier Module compensates for such shortcomings by synthesizing predictions using peer outputs and weights. Its architecture depends on averaging classifier weights and retrieved feature vectors from operational devices, producing a substitute prediction without any additional model duplication. This lightweight method makes the modifier particularly useful in restricted contexts.

Pooling strategy tradeoffs

The choice between max pooling and average pooling considerably influences inference robustness. As demonstrated in Fig. 2, average pooling regularly gives stronger resilience to outliers and device irregularities, delivering more balanced accuracy across failure scenarios. Max pooling, on the other hand, emphasizes high-confidence predictions and can outperform average pooling when at least one device gives a very accurate forecast.

Without the Modifier Module, max pooling occasionally underperforms because of its susceptibility to noisy outputs. However, once the modifier is implemented, the performance disparity between the two techniques narrows. The module boosts both fusion approaches, guaranteeing that high-confidence forecasts are tempered with consensus-based estimates. These findings show that average pooling is preferred for safety–critical applications needing stability, whereas max pooling may be utilized when devices are expected to give confident and clean forecasts.

Efficiency and real-time suitability

One of the main strengths of the proposed system is its appropriateness for real-time deployment on edge devices. The whole CNN architecture has just 15,074 parameters, costing around 14.72 KB of memory when utilizing 8-bit quantization. This design supports execution on lightweight IoT hardware with limited RAM and storage, such as Jetson Nano or Raspberry Pi.

The Modifier Module itself does not require independent training or storage, as it is generated on the fly using peer device weights and feature vectors. Its runtime algorithm incorporates a simple averaging operation and matrix–vector multiplication followed by a softmax activation. As a result, it incurs negligible latency.

The studies were conducted using PyTorch (v2.1.0 + cu118) and Python 3.10.12, using CUDA-based GPU acceleration. The training employed stochastic gradient descent over 40 epochs, and the inference was confirmed in settings with up to one broken device. The architecture’s minimal memory footprint and fast response time make it particularly ideal for time-sensitive, bandwidth-limited, and privacy-aware applications in IoT contexts.

To fully confirm the gains observed, we evaluated the statistical significance of the accuracy differences between the baseline and our proposed strategy. Across 10 independent runs for each scenario, the variation in accuracy was tiny (standard deviations were in the range of 0.2–0.5% for MNIST and ~ 0.5–1.0% for CIFAR-10, depending on the scenario), resulting in tight 95% confidence intervals (typically ± 0.3% or less for accuracy). We did pair t-tests comparing the baseline and Modifier Module outcomes for each dataset and pooling strategy. All comparisons indicated statistically significant improvements using the Modifier Module at the p < 0.05 level. In reality, for most cases p-values were significantly lower; for example, the boost in MNIST accuracy with max pooling (about + 1.49%) remained significant with \(p\approx 0.002\), and the smaller gain on CIFAR-10 with average pooling (+ 0.63%) was still significant with \(p\approx 0.03\). Table 6 shows the accuracy improvements (“recovery margins”) and their significance. We also offer the relative reduction in error rate for a more intuitive sense of impact. As observed, even a 0.63% accuracy improvement on CIFAR-10 (avg pooling) translates to nearly a 3% reduction in error (bringing error down from 20.47 to 19.84%), while the 1.49% gain on MNIST (max pooling) equates to roughly a 7.9% error reduction (from 18.89% down to 17.40% error). Such reductions are particularly important in high-accuracy environments.

Overall, the statistical analysis demonstrates that our Modifier Module produces persistent and considerable improvements. The possibility that our observed accuracy increases are due to random chance is quite low (in all cases, p substantially below 0.05). Hence, we can conclude with strong confidence that the module enhances the resilience and accuracy of the distributed CNN, rather than the findings being an artifact of noise. These statistical findings underline the practicality of the approach: it will dependably improve performance under failure scenarios, not just on average but in a repeatable and statistically verified manner.

In conclusion, the Implementation and Evaluation of our distributed CNN with the Modifier Module verify that the strategy is effective, efficient, and statistically robust. The system delivers excellent accuracy on hard vision tasks without reliance on any cloud resources, and it displays strong resistance to edge device failures—all with low computing expense. These qualities make it a promising choice for next-generation IoT applications requiring dependable on-site AI inference. The next section will address other elements such as security concerns and how our method might be modified or implemented in other scenarios.

Multi-device failure robustness

Beyond single-device failures, we tested the system’s resilience under many simultaneous device failures. Figure 4 displays classification accuracy as a function of the number of failed devices (varying from 0 to 5) on both the MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets. The baseline setup (without the Modifier Module) demonstrates a significant fall in accuracy as more devices go down. On MNIST, for instance, average pooling accuracy reduces from roughly 96% with no failure to about 80% with three failures, and further to below 60% with five failed devices. A similar trend is observed with CIFAR-10, where accuracy reduces from ~ 83 to ~ 50% as the number of defective devices grows.

In comparison, the proposed technique using the Modifier Module demonstrates substantially smoother deterioration. The accuracy is consistently higher than the baseline throughout all failure levels. With one or two failures, the accuracy reduction is negligible—MNIST accuracy remains around 94% even with two devices down, whereas the baseline drops into the upper 80s. On CIFAR-10, the Modifier maintains roughly 70% accuracy after three failures, exceeding the baseline by a margin of ~ 10%. These findings show the Modifier Module’s ability to construct surrogate predictions that sustain decision quality even in highly degraded settings.

Overall, our results demonstrate that the proposed system can continue reliable inference despite several concurrent failures, making it highly suitable to real-world edge contexts prone to intermittent connectivity, energy outages, or hardware disturbances.

Conclusion

This research provided a fault-tolerant distributed CNN architecture suited for edge-based IoT systems, stressing robustness to device failures and independence from cloud infrastructure. By introducing the Modifier Module—an adaptable, lightweight classifier generated from active peer devices—the proposed system dynamically adjusts for missing outputs without requiring model replication or cloud assistance. The Modifier is trained using a cooperative optimization approach incorporating simulated failures, which enforces inter-device compatibility and robust feature alignment.

Beyond single-failure recovery, our system displays remarkable resilience to numerous simultaneous device failures, retaining good accuracy even when up to five of six devices are idle. This capacity, proven by empirical evaluation on MNIST and CIFAR-10, shows the Modifier Module’s ability to synthesize useful surrogates from partial data, enabling gentle deterioration and sustained inference under stress. With only a small memory footprint (~ 14.72 KB) and low latency, the system delivers up to 1.5% greater accuracy and statistically significant reductions in error over dropout, ensemble, and federated averaging baselines.

Furthermore, our investigation found that average pooling delivers more robust fusion than max pooling in most circumstances, while the Modifier greatly mitigates flaws even in max-pooled systems. The suggested framework is scalable, efficient, and deployable in real-time situations, giving a viable option for robust AI in decentralized IoT infrastructures. Future work will explore generalizing this strategy to multimodal sensor data, supporting asynchronous device operation, and integrating federated retraining to respond to long-term device drift or deployment shifts.

Future work will focus on extending the Modifier Module to support asynchronous inference with irregular device reporting, incorporating multimodal sensor input (e.g., vision, audio, environmental), and enabling continuous adaptation through federated re-training under ideal drift. Additional possibilities include uncertainty-aware surrogate prediction to improve confidence calibration and studying energy-aware fault recovery where device dropout may be useful. While our approach simulates distributed data by partitioning images spatially, we acknowledge this does not fully replicate the non-IID nature of real-world IoT data (e.g., from multiple sensors or viewpoints). Future experiments will incorporate multi-sensor datasets to better evaluate system performance under heterogeneous conditions. Future work will also explore deployment in more realistic, heterogeneous environments using multi-view and multi-modal datasets to evaluate model generalization under non-IID input distributions commonly found in IoT systems. These enhancements aim to strengthen robustness and adaptability in real-world, dynamic IoT deployments.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study, MNIST, and CIFAR-10, are publicly available. The MNIST dataset can be accessed at http://yann.lecun.com/exdb/mnist/, and the CIFAR-10 dataset is available at https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html. These datasets were used for training and evaluating the models described in the manuscript.

References

Qin, J., Xiong, J. & Liang, Z. CNN–transformer gated fusion network for medical image super-resolution. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 15338 (2025).

Shah, A. A. et al. Deep learning ensemble 2D CNN approach towards the detection of lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 2987 (2023).

Esposito, M. et al. Bridging auditory perception and natural language processing with semantically informed deep neural networks. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 20994 (2024).

Pandian, J. A., Thirunavukarasu, R. & Mariappan, L. T. Enhancing lane detection in autonomous vehicles with multi-armed bandit ensemble learning. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 3198 (2025).

El-Assy, A. et al. A novel CNN architecture for accurate early detection and classification of Alzheimer’s disease using MRI data. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 3463 (2024).

Yousefpour, A. et al. Guardians of the deep fog: Failure-resilient DNN inference from edge to cloud. In Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Challenges in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Internet of Things (2019).

Teerapittayanon, S., B. McDanel, and H.-T. Kung. Distributed deep neural networks over the cloud, the edge and end devices. in 2017 IEEE 37th international conference on distributed computing systems (ICDCS). 2017. IEEE.

Mustafa, Z. et al., Intrusion detection systems for software-defined networks: a comprehensive study on machine learning-based techniques. In Cluster Computing, 1–27–1–27 (2024).

Ayyat, M., Nadeem, T. & Krawczyk, B. ClassyNet: Class-aware early-exit neural networks for edge devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 11(9), 15113–15127 (2023).

Verbraeken, J. et al. A survey on distributed machine learning. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 53(2), 1–33 (2020).

Tu, J., Yang, L. & Cao, J. Distributed machine learning in edge computing: challenges, solutions and future directions. ACM Comput. Surv. 57(5), 1–37 (2025).

Anwar, T. et al. Robust fault detection and classification in power transmission lines via ensemble machine learning models. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 2549 (2025).

Tan, J. et al. Innovative framework for fault detection and system resilience in hydropower operations using digital twins and deep learning. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 15669 (2025).

McMahan, B. et al. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (PMLR, 2017).

Mao, J. et al. Mednn: A distributed mobile system with enhanced partition and deployment for large-scale dnns. In 2017 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design (ICCAD) (IEEE, 2017).

Li, X. et al. On the convergence of fedavg on non-iid data. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.02189 (2019).

Li, L. et al. A review of applications in federated learning. Comput. Ind. Eng. 149, 106854 (2020).

Albshaier, L., Almarri, S. & Albuali, A. Federated learning for cloud and edge security: A systematic review of challenges and AI opportunities. Electronics 14 (5), 1019 (2025).

Hou, Z. & Ohtsuki, T. Loss-adapter: Addressing network packet loss in distributed inference for lossy IoT environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 12 (15), 22048–22057 (2025).

Lee, S. et al. Cyber-physical AI: Systematic research domain for integrating AI and cyber-physical systems. ACM Trans. Cyber Phys. Syst. 9(2), 1–33 (2025).

Li, T. et al. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. In Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems, Vol. 2 429–450 (2020).

Zhu, J. et al., Unlocking the value of decentralized data: A federated dual learning approach for model aggregation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.20138 (2025).

Lynch, J. et al. The case for decentralized fallback networks. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM Workshop on Hot Topics in Networks (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Edgeci: Distributed workload assignment and model partitioning for cnn inference on edge clusters. ACM Trans. Internet Technol. 24(2), 1–24 (2024).

Teerapittayanon, S., McDanel, B. & Kung, H.-T. Branchynet: Fast inference via early exiting from deep neural networks. In 2016 23rd International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR) (IEEE, 2016).

Mao, J. et al. Modnn: Local distributed mobile computing system for deep neural network. In Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), 2017 (IEEE, 2017).

Yousefpour, A. et al. Resilinet: Failure-resilient inference in distributed neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.07386 (2020).

Gu, Z. et al. Gradient shielding: Towards understanding vulnerability of deep neural networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 8(2), 921–932 (2020).

Qiao, C. et al. An efficient incentive mechanism for federated learning in vehicular networks. IEEE Netw. 38(5), 189–195 (2023).

Lu, H. et al. DeepAutoD: Research on distributed machine learning oriented scalable mobile communication security unpacking system. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 9(4), 2052–2065 (2021).