Abstract

Understanding the physiological and biochemical responses of Beta vulgaris to cadmium toxicity and iron supplementation is crucial for optimizing plant performance under heavy metal contamination scenarios. However, knowledge about how varying iron concentrations mediate cadmium-induced stress responses in sugar beet remains limited. We investigated morphological, physiological, and biochemical responses of B. vulgaris exposed to different cadmium concentrations (0, 1, and 2 mg L⁻¹) and iron levels (2.5, 5, and 7.5 mg L⁻¹) under hydroponic conditions through a factorial experiment using completely randomized design with three replications. Cadmium concentration and iron supplementation significantly influenced all measured parameters (p ≤ 0.01). Plants receiving 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe consistently demonstrated superior stress tolerance, maintaining higher growth performance, better mineral nutrition, stronger antioxidant defenses, and more effective metabolic regulation under 2 mg L⁻¹ Cd stress compared to control iron levels (2.5 mg L⁻¹). Specifically, higher iron supplementation restored leaf number, leaf area, chlorophyll content, and yield to near-control levels, while also reducing cadmium accumulation in both roots and shoots. Oxidative stress mitigation was also more pronounced with 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe treatment, with better restoration of H₂O₂ and malondialdehyde levels to control ranges, suggesting more efficient antioxidant defense mechanisms. Mineral nutrition patterns also differed markedly, with higher iron levels improving Fe, Zn, Cu, and Mn concentrations while simultaneously reducing cadmium uptake and translocation. We conclude that iron supplementation significantly influences B. vulgaris resilience to cadmium toxicity, with 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe emerging as the optimal concentration for cadmium stress mitigation. Relative differences in stress response mechanisms between iron treatments provide insights for phytoremediation strategies, while the quantitative stress response patterns identified offer valuable parameters for optimizing sugar beet cultivation in cadmium-contaminated environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heavy metal contamination of agricultural soils, particularly cadmium (Cd) pollution, has emerged as one of the most pressing environmental challenges threatening global food security and human health. The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) ranks Cd among the top ten hazardous substances due to its exceptional toxicity and environmental persistence1. This classification reflects the metal’s unique ability to bioaccumulate in living organisms and its propensity to enter the food chain without causing immediate visible symptoms in plants, making it particularly insidious in agricultural systems2. While natural geological formations contribute to soil Cd levels, anthropogenic activities have dramatically accelerated contamination rates. Industrial emissions, improper waste disposal, and particularly the extensive use of phosphate fertilizers have introduced substantial quantities of Cd into agricultural soils globally. Phosphate fertilizers alone can contribute up to 170 mg of Cd per kilogram of fertilizer3, and in regions with intensive agriculture such as Iran, decades of fertilizer application have resulted in the accumulation of 200–600 g of Cd per hectare4. Indeed, the biogeochemical behavior of Cd in soil-plant systems presents unique challenges for sustainable agriculture5,6. Unlike essential elements required for plant metabolism, Cd demonstrates exceptionally high bioaccumulation potential, often exceeding that of many nutrients3. The metal’s affinity for sulfate-containing biomolecules, particularly proteins and enzymes, leads to widespread disruption of cellular processes7. Cd toxicity manifests through multiple pathways, including chloroplast degradation, photosynthetic inhibition, enzyme deactivation in CO₂ fixation pathways, and disruption of nitrogen and sulfur metabolism⁷. These effects are compounded by Cd’s interference with essential element uptake, as the metal competes for transport systems designed for iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn)8. Even at relatively low soil concentrations9[,10 Cd exposure triggers a cascade of physiological disruptions, including chlorophyll degradation, metabolic dysfunction, and ultimately growth suppression and necrosis6,11,12,13,14.

The interaction between Cd toxicity and essential element nutrition, particularly Fe metabolism, represents a critical area of investigation for developing mitigation strategies15,16. Fe serves fundamental roles in plant physiology, particularly in electron transport systems, respiratory processes, and photosynthetic light reactions17. The competitive relationship between Cd and Fe at the cellular level suggests that Fe supplementation may provide a viable approach for alleviating Cd toxicity. Previous research by various investigators14[,15[,16 has documented the detrimental effects of Cd on photosynthetic pigments and protein synthesis, while studies on leguminous species have demonstrated the potential for Fe supplementation to mitigate Cd accumulation and restore physiological function18. However, the optimal Fe concentrations required for effective Cd stress amelioration remain poorly defined, particularly in hydroponic production systems. In this regard, Beta vulgaris (sugar beet) represents an ideal model system for investigating Fe-Cd interactions due to its unique physiological characteristics and commercial importance. As a member of the Chenopodiaceae family, this biennial species produces substantial fleshy storage roots and demonstrates remarkable adaptability to diverse growing conditions19[,20. Global sugar beet production encompasses 4.5 million hectares and generates approximately 269 million tons annually21, highlighting its economic significance. Beyond its industrial applications, red beetroot varieties are valued for their nutritional properties, including high Fe content, beneficial mineral profiles, and the presence of bioactive compounds such as betacyanins22[,23. Notably, B. vulgaris exhibits among the highest Cd translocation ratios (shoot/root) compared to other crop species24, making it particularly suitable for studying metal accumulation patterns and developing phytoremediation strategies.

Despite extensive research on Cd toxicity mechanisms and the documented potential for Fe supplementation to ameliorate heavy metal stress, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding optimal Fe concentrations for Cd mitigation in hydroponic systems. The precise physiological and biochemical mechanisms underlying Fe-mediated protection against Cd toxicity, particularly in root vegetable species, require further elucidation. Furthermore, the relationship between Fe supply levels and Cd uptake patterns in controlled environment agriculture has not been systematically characterized. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to: (I) evaluate the interactive effects of varying Cd and Fe concentrations on morphological and physiological parameters in hydroponically grown B. vulgaris; (II) quantify the influence of Fe supplementation on Cd accumulation patterns in root and shoot tissues; (III) assess oxidative stress responses and antioxidant defense mechanisms under different Fe-Cd treatment combinations; and (IV) identify optimal Fe concentrations for minimizing Cd toxicity and uptake in sugar beet cultivation systems. By addressing these objectives, this research aims to contribute essential knowledge for developing effective strategies to mitigate heavy metal contamination in vegetable production while optimizing mineral nutrition in hydroponic systems.

Results

Leaf number, leaf area index, leaf chlorophyll, and yield analysis under Fe and Cd treatments

To assess the interactive effects of cadmium and iron concentrations on morphological parameters, leaf number analysis was used. Changes in leaf number were identified using factorial analysis of variance. These tests revealed significant differences among treatments (p ≤ 0.01), as indicated by the letter groupings in Fig. 1. The most striking result to emerge from the data is that Cd stress at 2.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe led to a 24.1% decrease in leaf numbers compared to unstressed controls. Further analysis showed that the greatest reduction in leaf number (8.83 leaves per plant) was observed in plants treated with 2 mg L⁻¹ Cd supplemented with 2.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe. The leaf numbers of Cd-treated plants, particularly at 2 mg L⁻¹, were significantly lower than in plants that were adequately supplemented with 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe. Interestingly, this adverse effect of Cd was reversed after the addition of 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe to the plants, even in the presence of Cd treatment. Strong evidence of Fe-mediated protection was found, as plants treated with 7.5 and 5 mg L⁻¹ Fe, regardless of Cd presence, maintained the highest leaf numbers. No significant difference was found between these two Fe treatments.

To evaluate leaf area responses, the interaction between varying Fe and Cd concentrations was tested. These tests revealed that the interaction significantly (p ≤ 0.01) affected leaf area index of red beet (Fig. 2). The correlation between leaf area index and Fe concentration in nutrient solution was found to be particularly strong. No significant differences were detected between all treatments containing 5 or 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe in nutrient solution regardless of Cd stress, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Further analysis showed that all mentioned treated plants had the highest leaf area. The most striking observation to emerge from the data comparison was that plants under severe Cd stress (2 mg L⁻¹) fed with 2.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe had the least leaf area index (324.83 cm²), followed by mild Cd stress (1 mg L⁻¹) plants with the same feeding solution (427.26 cm²).

To assess chlorophyll content responses, statistical analysis was used to test treatment effects. These tests revealed significant differences between treatments (p ≤ 0.01), as shown in Fig. 3. Strong evidence of Cd-induced chlorophyll reduction was found. The single most conspicuous observation to emerge from the data was that plants under 2 mg L⁻¹ Cd and control level of Fe (2.5 mg L⁻¹) showed the least leaf chlorophyll content (45.63) compared to other treatments. Further analysis showed that increased levels of Fe in nutrient solution increased leaf chlorophyll up to 5.96% compared to the least amount of chlorophyll. The average score for maximum leaf chlorophyll was 58.6, which was found in control plants supplemented with 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe, as depicted in Fig. 3.

To evaluate yield responses, Cd stressed plants showed a significant decrease (p ≤ 0.01) in yield. These tests revealed that at 2.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe, plants treated with 2 mg L⁻¹ Cd showed a 70% decrease in yield compared to untreated plants (Fig. 4). Further analysis showed that the yield of Cd-treated plants, especially at 2 mg L⁻¹, was significantly lower than that of plants adequately supplemented with 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe in control plants without Cd treatment. The greatest reductions (24.5, 34.67, and 48 g plant⁻¹) were observed in plants treated with 2 mg L⁻¹ Cd supplemented with 2.5 and 5 mg L⁻¹ Fe, followed by plants under 1 mg L⁻¹ Cd and 2.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe. Interestingly, this adverse effect of Cd was reversed after the addition of 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe, even in the presence of Cd treatment. The average score for maximum yield was 153.67 g plant⁻¹, which was found in plants fed with 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe without Cd stress, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Different alterations of metal ions under Fe and Cd treatments

To investigate mineral concentrations, the concentrations of Zn, Fe, Cd, Cu, and Mn in red beet roots and leaves were analyzed under different nutritional solutions containing Fe and Cd. Additionally, Ca and Mg levels were assessed. These tests revealed that the interaction between varying Cd and Fe concentrations significantly (p ≤ 0.01) affected the adsorption of tested nutrients in leaves and roots of red beet. Strong evidence of decreasing Zn concentration was found with increasing levels of both Cd and Fe in nutrient solution, according to Fig. 5a. Further analysis showed that control plants, as well as Cd stressed plants at 1 and 2 mg L⁻¹ treated with 2.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe, accumulated the maximum level of Zn up to 82.36, 74.6, and 70.73 mg kg⁻¹ DW, respectively in leaves. The single most marked observation was that plants under 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe in combination with 2 mg L⁻¹ Cd had the least amount of Zn (34.16 mg kg⁻¹ DW). The same decreasing trend was observed in the roots. The average values for maximum and minimum level of Zn concentration in roots were 69.76 and 19.1 mg kg⁻¹ DW, which were found in plants treated with 2.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe under 0 and 2 mg L⁻¹ Cd, respectively (Fig. 5b). Comparison of the least amount of Zn in leaves and roots (31.16 against 19.1 mg kg⁻¹ DW) revealed that Zn uptake in roots was much lower than leaves under the same conditions.

To evaluate Fe concentration as a sensitive marker, the response of normal or Fe-supplemented plants to Cd exposure was tested. These tests revealed that Cd stress caused a decrease in Fe concentration in both leaves and roots under control Fe levels (2.5 mg L⁻¹), by 48.9% and 39.7%, respectively, compared to unstressed plants (Fig. 6a and b). Further analysis showed that plants responded to increased levels of Fe by displaying a 63.5% increase in leaf Fe concentration even at severe Cd stress (2 mg L⁻¹) (Fig. 6a). This increment was more pronounced in roots of Cd-treated plants (2 mg L⁻¹) supplemented with 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe (85.9%). The average values for maximum and minimum level of Fe in leaves were 377.5 and 124.63 mg kg⁻¹ DW, which were observed respectively in unstressed plants fed with 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe and Cd stressed plants fed with 2.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe (Fig. 6a). The results of the roots showed different patterns as unstressed plants and Cd stressed plants (1 mg L⁻¹) fed with 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe showed the highest amount of Fe (387.7 and 340.97 mg kg⁻¹ DW), while the least Fe concentration in roots (127.5 mg kg⁻¹ DW) was found in Cd stressed plants (2 mg L⁻¹) under control level (2.5 mg L⁻¹) of Fe (Fig. 6b). Comparison of Fe concentration in Cd stressed plants at 2 mg L⁻¹ level and treated with 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe revealed higher levels of Fe uptake in roots at the mentioned conditions.

Analysis of Cd concentration in the leaves and roots of red beet revealed an increasing trend in Cd content with rising levels of Cd in nutrient solution. However, supplementing solution with Fe, especially at 7.5 mg L⁻¹ was found to inhibit Cd uptake in both leaves (Fig. 7a) and roots (Fig. 7b). The most striking result to emerge from the data is that a high Cd concentration (59.66 mg kg⁻¹DW) was observed in the leaves of Cd-treated plants, particularly at 2 mg L⁻¹ Cd. Interestingly, the concentration decreased by up to 48.2% in plants supplemented with Fe (Fig. 7a). Similar to the leaves, plants treated with 2 mg L⁻¹ Cd stress and control level of Fe (2.5 mg L⁻¹) showed the highest (46.66 mg kg⁻¹DW) amount of Cd in their roots while it decreased up to 52.5% in mentioned plants treated with 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe (Fig. 7b). Furthermore, Cd uptake of the roots of red beet was found to be less than leaves at Cd stressed plants fed with 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe (22.19 mg kg⁻¹DW against 30.9 mg kg⁻¹DW) (Figs. 7a and b).

With regard to Figs. 8a and b, the analysis showed that increased levels of Cd decreased Cu content respectively in leaves and roots up to 26.8% and 8.6%. The control plants treated with 2.5 and 5 mg L⁻¹ Fe followed by Cd stressed (1 mg L⁻¹) plants treated with 2.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe, demonstrated the maximum Cu content in leaves (Fig. 8a). On the other hand, increased levels of Fe in nutrient solution were found to decrease Cu concentration in leaves as Cd stressed plants (2 mg L⁻¹) under both 5 and 7.5 mg L⁻¹ exhibited the minimum (20.63 and 19 mg kg⁻¹DW) Cu concentration compared to the other treatments (Fig. 8a). The same decreasing trend was also observed in Cu content of roots along with increased levels of Cd as well as Fe (Fig. 8b). The maximum (20.36 mg kg⁻¹DW) Cu content of roots was related to the control plants under 2.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe while plants under 2 mg L⁻¹ Cd in combination with 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe accumulated the least (16 mg kg⁻¹DW) amount of Cu in roots (Fig. 8b). It is noteworthy that Cu levels in leaves were more than that in roots (Figs. 8a and b).

The tests revealed that increased levels of Mn in red beet leaves decreased in parallel with increased levels of Cd by 26.1% compared to the control plants. On the other hand, increased levels of Fe were found to decrease leaf Mn concentration either in controls or Cd stressed plants as illustrated in Fig. 9a. The maximum (258.83 mg kg⁻¹ DW) and minimum (156.57 mg kg⁻¹ DW) levels of Mn in red beet leaves were recorded respectively in control plants fed with 2.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe and Cd stressed plants fed with 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe in nutrient solution (Fig. 9a). Regarding Fig. 9b, Mn concentration in roots was found to decrease also along with increased levels of Cd and Fe in nutrient solution. Control plants treated with 2.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe accumulated the highest (172.93 mg kg⁻¹ DW) amount of Mn in roots while plants treated with Cd (2 mg L⁻¹) and Fe (7.5 mg L⁻¹), recorded the least (81.63 mg kg⁻¹ DW) amount of Mn in roots (Fig. 9b). However, Mn concentration in roots was found to be less than that in leaves in both stress and unstress conditions (Figs. 9a and b).

Production of MDA and H2O2 in response to Cd toxicity and its alleviation by Fe supplementation

A significant difference (p ≤ 0.01) was observed in MDA and H₂O₂ accumulation in red beet leaves between different concentrations of Fe and Cd in the nutrient solution, as depicted in Figs. 10 and 11, respectively. The analysis revealed that Cd-treated red beet leaves exhibited oxidative damage, evident by increased MDA and H₂O₂ levels. The MDA concentration was found to increase by 19.5% in plants under 2 mg L⁻¹ Cd stress and fed with 2.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe (Fig. 10). The results showed that MDA levels recovered when Fe was supplied to Cd-treated plants at both 5 and 7.5 mg L⁻¹ Fe concentrations. However, the least (55.8 µmol g⁻¹ FW) MDA content was observed in control plants fed with 5 mg L⁻¹ Fe compared to the plants under severe Cd stress (2 mg L⁻¹) (Fig. 10). Similar to the MDA content, the amount of H₂O₂ increased significantly in Cd stressed plants at 2 mg L⁻¹ concentration combined with the control level of Fe (2.5 mg L⁻¹) as 2.43 mmol g⁻¹ FW (Fig. 11). However, the concentration of H₂O₂ decreased in all other treatments as much as control plants (unstressed conditions) as depicted in Fig. 11.

Pearson correlation and principal component analysis (PCA)

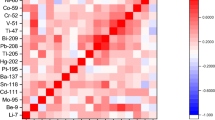

The analysis of the relationships among growth and biochemical characteristics (Fig. 12) indicated that yield exhibited strong positive correlations with chlorophyll content (r = 0.81), root Fe (r = 0.88), leaf Fe (r = 0.84), leaf number (r = 0.89), MDA (r = 0.64), and H₂O₂ (r = 0.60). Additionally, root Mn (r = 0.54), leaf Mn (r = 0.55), leaf Cu (r = 0.50), leaf Fe (r = 0.79), root Fe (r = 0.75), yield (r = 0.81), leaf number (r = 0.87), MDA (r = 0.54), and H₂O₂ (r = 0.57) all demonstrated significant positive correlations with chlorophyll content. Furthermore, a negative correlation was identified between leaf Cd with H₂O₂ (r = −0.53), MDA (r = −0.55), leaf number (r = −0.78), yield (r = −0.88), root Fe (r = −0.71), leaf Fe (r = −0.82), leaf Mn (r = −0.63), leaf Cu (r = −0.58), and chlorophyll content (r = −0.86). The leaf Fe was positively correlated with chlorophyll content (r = 0.79), root Fe (r = 0.81), yield (r = 0.84), and leaf number (r = 0.82), while exhibiting a negative correlation with root Cd (r = −0.84) and leaf Cd (r = −0.82). Given that yield is an economically important trait in red beet, any factor that leads to increased yield will also be economically important and valuable. Consequently, these traits warrant consideration by plant breeders in their selection processes. In this research, Fig. 12 illustrates the principal component analysis (PCA) of the studied traits of red beet. Different treatments with Cd and Fe, as well as various characteristics under study, are grouped accordingly. The first and second main components explain 78.07% of the total variance, with the first principal component representing 49.99% and the second principal component representing 28.08% of the total variance. The vectors of traits such as leaf area, leaf number, yield, leaf chlorophyll, and leaf Fe are oriented in the positive direction of PC1, indicating a positive correlation of these traits with treatments lacking cadmium and supplemented with higher levels of iron (e.g., Cd0Fe5 and Cd0Fe7.5). This suggests that iron application in the absence of cadmium enhances plant growth and productivity. In contrast, stress-related traits such as leaf H₂O₂ and MDA, which are indicators of oxidative stress, are located on the opposite side of the biplot (left side), particularly associated with treatments containing high cadmium and low iron levels (e.g., Cd2Fe2.5). This reflects an intensification of oxidative stress under these conditions. Cadmium accumulation in roots and leaves (Root Cd and Leaf Cd) is more aligned with the PC2 axis and is separated from the other positive performance traits, confirming the negative impact of Cd on plant growth. Traits like Root Zn, Root Cu, Leaf Mn, and Leaf Cu are positively associated with PC2 and are closely related to treatments containing iron and no cadmium, suggesting that iron may enhance the uptake of certain micronutrients, potentially due to competitive or synergistic interactions. Treatments such as Cd2Fe5 and Cd2Fe7.5 are positioned in the lower-left quadrant of the biplot, distant from the centroid, and are associated with more negative traits, indicating adverse combined effects of high Cd and Fe levels, which may be due to metal toxicity or interference in nutrient uptake. Overall, PCA clearly demonstrated that treatments without cadmium and with moderate to high levels of iron (especially Cd0Fe5 and Cd0Fe7.5) showed the highest correlation with positive growth and yield traits, whereas treatments containing cadmium and low iron (e.g., Cd2Fe2.5) were associated with stress and toxicity indicators. These findings underscore the importance of optimal iron supplementation in mitigating the negative effects of cadmium on B. vulgaris growth (Fig. 12).

Discussion

Growth parameters and performance

The morphological responses observed in B. vulgaris under cadmium stress conditions represent significant findings in understanding plant adaptability to increasing heavy metal contamination challenges. Due to a variety of anthropogenic factors, including the use of agricultural inputs (pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers, especially phosphate fertilizers), industrial processes, and natural sources, elevated levels of heavy metals have been extensively recorded in agricultural soils3,25. The cadmium treatments produced severe adverse effects across all measured parameters, with seeds of B. vulgaris treated with varying amounts of Cd showing an overall decrease in leaf number, leaf area, leaf chlorophyll, as well as overall plant performance, when compared to control conditions. A key physiological mechanism underlying these results involves impaired cellular metabolism and resource allocation. The substantial reductions in chlorophyll-related traits reflect compromised photosynthetic capacity, aligning with findings by Pandey and Sharma26, who demonstrated that high concentrations of Ni2+, Cd2+, and Co2+ led to a significant reduction in the chlorophyll concentration of cabbage. The toxicity of Cd fundamentally disrupted plant mineral uptake by limiting the adsorption of essential nutrients27, consequently leading to decreased plant growth and development. However, our findings demonstrate that iron supplementation significantly ameliorated these adverse effects through multiple antagonistic mechanisms. The application of elevated Fe concentrations (5 and 7.5 mg L⁻¹) markedly improved growth parameters, suggesting that Fe plays a crucial role in mitigating Cd toxicity by competing for common binding sites on root cell membranes and reducing Cd uptake28,29,30,31,32. This competitive interaction at the physiological level has been well-documented in various plant species, where Fe supplementation has been shown to reduce Cd translocation from roots to shoots by occupying metal transporter proteins30,31,32. Furthermore, Cd stress reduced photo assimilation and subsequent growth, with these negative effects being generally more pronounced in upper parts of the plant rather than underground parts28. Iron’s protective role extends beyond simple competition, as it is essential for maintaining photosynthetic efficiency and chlorophyll biosynthesis. Our results indicate that Fe supplementation restored chlorophyll content in Cd-stressed plants, likely through its involvement as a cofactor in key enzymes of chlorophyll synthesis and its role in maintaining the structural integrity of photosynthetic membranes29,30,31. Additionally, Fe participates in antioxidant defense mechanisms, with Fe-containing enzymes such as catalase and peroxidases playing vital roles in scavenging reactive oxygen species generated under Cd stress29,30,31. The observed chlorophyll degradation represents a critical aspect of cadmium toxicity mechanisms. The most important reasons for the decrease in chlorophyll concentration include its degradation by reactive oxygen species, which is demonstrated in our experiment by elevated H₂O₂ (Fig. 10) and MDA (Fig. 11) production, and the inhibition of chlorophyll biosynthesis under heavy metals through the suppression of two key enzymes: gamma-aminolaevulinic acid dehydrogenase and protochlorophyllide reductase29. The significant reduction in H₂O₂ and MDA levels observed with Fe supplementation (Figs. 10 and 11) provides direct evidence of Fe’s role in enhancing oxidative stress tolerance. This ameliorative effect can be attributed to Fe-dependent antioxidant enzyme activation and the maintenance of cellular redox homeostasis10,31,32. Additionally, the displacement of Mg in the chlorophyll structure by heavy metals represents one of the main destructive effects of these elements on chlorophyll integrity, fundamentally compromising the photosynthetic apparatus functionality. Iron may indirectly protect against this displacement by maintaining proper mineral balance and supporting the uptake and utilization of essential nutrients like Mg, thereby preserving chlorophyll structure and function8,10. The dramatic impact on chlorophyll index provides a reliable indicator of B. vulgaris’ ability to handle abiotic stress. Chlorophyll concentration rapidly decreased with increasing Cd levels, consistent with observations reported in various vegetables, including Spinacia oleracea30, Lactuca sativa31, Zea mays32, and Brassica juncea10 subjected to Cd stress. This widespread response across different plant species suggests that chlorophyll degradation represents a fundamental response to heavy metal toxicity rather than a species-specific adaptation. Nevertheless, the protective effects of Fe supplementation observed in our study align with previous reports in Beta vulgaris and other crop species28,29,30,31,32, where increased Fe availability effectively counteracted Cd-induced growth inhibition and physiological damage through enhanced nutrient acquisition, improved antioxidant capacity, and reduced oxidative stress.

Minerals value

Mineral value and nutrient interactions

Under cadmium stress conditions, the mineral composition responses observed in B. vulgaris revealed significant disruptions in essential nutrient homeostasis, with several notable patterns emerging from our analysis. The negative impact of Cd stress on Fe concentration has been extensively reported in leaves, causing impairment of chlorophyll metabolism33. Furthermore, chlorophyll degradation and/or inhibition of its biosynthesis has been documented to contribute to impaired photosynthesis in Cd-stressed plants34. Therefore, we speculated that increasing Cd stress negatively affected the photosynthetic capacity of B. vulgaris, leading to reduced growth as depicted in Fig. 4. The cellular-level disruptions caused by heavy metals fundamentally compromise plant metabolic processes. Heavy metals reduce cell division and inhibit cell growth by lowering cell turgor pressure; they subsequently accumulate in the cell wall and enter the cytoplasm, disrupting normal cellular metabolism35, which ultimately leads to reduced growth and can be a major cause of reduced yield. The decrease in biomass due to Cd can be attributed to the sensitivity of carbon reduction cycle enzymes involved in the photosynthesis process, which has been previously demonstrated by other researchers36. Mineral analysis in leaves and roots of red beet revealed that the presence of Cd drastically reduced the concentration of Zn, Cu, and Mn (Figs. 5 and 8, and 9). Remarkably, increasing Fe concentration in the nutrient solution not only failed to mitigate the adverse effects of Cd, but also further decreased the uptake of these minerals. For instance, leaf Zn concentration in Cd-stressed plants (2 mg L− 1 concentration) combined with 2.5 mg L− 1 Fe was reduced by 14.1%, whereas in plants fed with 7.5 mg L− 1 Fe, this value reached 58.5% compared to control plants (unstressed plants fed with 2.5 mg L− 1 Fe), as demonstrated in Fig. 5a. These percentages for Cu content were 26.8% and 39.8% (Fig. 8a) and for Mn were 26.1% and 39.5% (Fig. 9a). The same trend was observed in roots, with the notable difference that the total accumulated amounts of Zn, Cu, and Mn were lower in roots than in leaves (Figs. 5 and 8, and 9). Critically, the inhibitory effect of Fe on Zn, Cu, and Mn uptake was greater than the toxicity effect of Cd alone. The antagonism effect between Fe and the elements Zn, Cu, and Mn, preventing their absorption, is clearly evident at higher Fe concentrations (7.5 mg L− 1), which are much more considerable in leaves than in roots. This phenomenon has been observed in the interaction between Cu and Cd by Qian et al.37 and Wang et al.38, supporting the concept of antagonistic interactions in heavy metal toxicity. Mechanistic explanations for these mineral interactions reveal complex competition processes at the cellular level. The antagonistic effect of Cd with microelements is likely responsible for this phenomenon39. Cu functions as an electron carrier in photosynthetic organisms and serves as a cofactor in the structure of various enzymes40. Cd competes with Cu for these sites due to its strong affinity for compounds containing sulfhydryl (−SH) functional groups37. Other possible mechanisms include the occupation of enzyme cofactor sites involved in photosynthesis by Cd, reduced glucose production, and diminished active adsorption of Cu37,40.

The chemical similarity between Cd and Cu creates particularly severe competitive interactions. Cd and Cu exhibit a negative interaction, primarily due to the chemical similarity and equivalence of these two elements, which results in similar chemical behavior in nature41. This similarity leads to competition for binding sites on the plasma membrane and for transport across the membrane, fundamentally disrupting normal nutrient acquisition processes. Iron-cadmium interactions present additional complexity in heavy metal toxicity mechanisms. Although Biyani et al.18 reported that very high Cd accumulation occurred in plants grown under Fe deficiency in the presence of Cd toxicity, and that Fe supplementation decreased Cd accumulation, this was not observed in our results. In our experiment, Fe concentration in both leaves and roots decreased with increasing Cd levels in nutrient solution. However, supplementing Fe in nutrient solution increased Fe concentration in leaves and roots even under Cd stress conditions (Fig. 6a and b). The increase in Fe concentration can be attributed to the competition of Fe with Cu and Mn elements for absorption42. Additionally, siderophore secretion increases in the presence of Cd43. Cd interferes with the uptake of micronutrients, including Fe, by affecting the root plasma membrane, causing disruption in the absorption and distribution of Cu and Mn in various plant organs44. Studies examining the effects of Fe deficiency on Cd absorption in rice observed that Fe deficiency increased the concentration of Cd, which can be related to the increase in the activity of the plasma membrane hydrogen (H+) pump in response to the accumulation of heavy metals45. Transporter-mediated mechanisms provide molecular explanations for the observed mineral interactions. Fe and Cd are both divalent cations whose transportation is facilitated by similar transporters in plants46. The expression level of the Fe2 transporter cloned from Arabidopsis, IRT1, demonstrated that low levels of Fe caused up-regulation, which is responsible for facilitating the transport of heavy-metal divalent cations such as Cd2+ and Zn2+, in addition to Fe2+, as documented by biotechnological studies47. Conversely, Fe can reduce Cd toxicity in root vegetables by competing with Cd for uptake by the plant and by promoting the formation of iron plaque on root surfaces, which can bind and immobilize Cd48.

The manganese-cadmium interaction follows similar competitive patterns. Cd competes with Mn for transport through transport proteins in the cell membrane, with Mn concentrations being reduced in the presence of Cd in white lupin49. The function of transport proteins in the plasma membrane may be impaired under Cd stress, affecting membrane permeability50. In cadmium-treated plants, during the process of homogenization, free Cd within the cell in vacuoles, cytoplasm, or apoplast is likely replaced by Mn through cation exchange; however, most of the Cd is stored in the cytosol by binding with biomolecules51. Zinc-cadmium interactions represent one of the most extensively studied but controversial aspects of heavy metal toxicity. The interaction between Zn and Cd has been extensively investigated, but remains a controversial topic, as it depends greatly on plant species, growing conditions (soil vs. hydroponic systems), experimental settings (field vs. greenhouse), and the levels of Cd applied52,53. This complexity was evident in our experiment, where the absorption of Cu, Zn, and Mn was more strongly inhibited by Fe supplementation than by Cd stress alone. Numerous reports document both antagonistic and synergistic interactions between Cd and Zn. The effects of Cd are more pronounced when plants are exposed to Zn deficiency. In such cases, the secretion of siderophores from Zn-deficient roots increases, leading to greater uptake and translocation of Cd from roots to shoots, thereby exacerbating Cd toxicity symptoms8. Excess Cd supply has been reported to increase macronutrient concentrations while decreasing micronutrient concentrations in Aeluropus littoralis54, consistent with our results.

Cadmium accumulation patterns revealed interesting distribution differences between plant organs. Regarding Cd concentration in leaves and roots of red beet, roots accumulated lower concentrations of Cd compared to leaves. Under 2 mg L− 1 Cd and 2.5 mg L− 1 Fe conditions, Cd content reached 46.55 mg kg− 1 DW in the roots (Fig. 7b), while Cd concentrations in leaves were estimated as 9.13 and 22.31 mg kg− 1 DW in plants treated with 1 mg L− 1 Cd and 2 mg L− 1 Cd combined with 7.5 mg L− 1 Fe, respectively (Fig. 7b). However, Cd concentrations measured in roots remained within toxic ranges, considering that mean Cd concentration ranges from 0.013 to 0.22 mg kg− 1 DW for cereal grains, 0.07 to 0.27 mg kg− 1 DW for grasses, and 0.08 to 0.28 mg kg− 1 DW for legumes3. The toxicity potential of heavy metals in the environment depends on their concentration in the soil solution, as higher metal concentrations in the soil solution led to greater uptake by plants55. Iron deficiency implications extend beyond direct nutritional effects to influence multiple physiological processes. Most literature suggests that Fe deficiency in plants leads to alterations in several physiological parameters including photosynthesis, respiration, nitrogen fixation, DNA synthesis, and chlorophyll formation56,57. Conversely, under conditions of low Fe absorption, plants often accumulate toxic metals in their roots58. Fe, Mn, and Cu concentrations in rice shoot are reduced in the presence of Cd59, likely due to similarities in the physical and chemical properties of Cd and other bidentate cations60. These elements have adverse effects on plant growth traits such as plant height, fresh weight, dry weight, and leaf area61, which is consistent with our observed results.

Oxidative damage

In our findings, the oxidative stress responses observed in B. vulgaris under cadmium exposure reveal critical insights into cellular defense mechanisms and their limitations under heavy metal toxicity. Cd induces oxidative stress by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS)62 in the form of various oxygen free radicals. ROS are considered an unavoidable by-product of normal aerobic metabolism that can disrupt cellular homeostasis63. The assessment of oxidative stress through the overproduction of H₂O₂ and MDA in control B. vulgaris plants (Figs. 10 and 11) provides clear evidence of Cd-induced cellular damage. Biomarker analysis demonstrated significant oxidative damage under cadmium stress conditions. To evaluate oxidative damage in B. vulgaris under Cd stress, we measured relevant biomarkers, specifically H₂O₂ and MDA, as illustrated in Figs. 10 and 11. Results indicated that elevated amounts of H₂O₂ and MDA, especially at 2 mg L− 1 Cd, were recovered by Fe supply in nutrient solution, indicating that Fe can counteract the negative effects of Cd stress. The iron-mediated amelioration of oxidative damage represents a particularly significant finding. In our present study, we observed that red beet leaves produced ROS in the form of MDA and H₂O₂ under Fe deprivation in the presence or absence of Cd treatment, particularly evident in MDA results (Fig. 11), consistent with observations in many other plant species under various stress conditions64,65. In our previous work on Cd toxicity in lettuce, we similarly found increased levels of MDA and H₂O₂ without any ameliorative effect of microelements66. However, in the presence of Fe in Cd-treated B. vulgaris plants, MDA and H₂O₂ levels were lower than in control plants, indicating the ameliorative effect of Fe. Previous literature has demonstrated that increased MDA content in Cd-treated plants leads to disruption of cellular water and nutrient balance, which ultimately reduces fresh weight. The adverse effects of heavy metals can be mitigated by microelements such as Zn66 and Fe, as confirmed by our current findings. The mechanistic basis for iron’s protective role involves multiple cellular processes. Iron supplementation appears to enhance antioxidant defense systems, potentially through improved enzyme function and cellular repair mechanisms. This protective effect demonstrates the complex interplay between essential minerals and heavy metal toxicity, where adequate nutrition can provide some degree of protection against oxidative damage. The observation that Fe supplementation not only prevented additional oxidative damage but actually reduced stress markers below control levels suggests that iron may enhance the plant’s natural antioxidant capacity beyond baseline conditions. These findings collectively demonstrate that while cadmium toxicity severely compromises plant growth and cellular integrity through multiple mechanisms including chlorophyll degradation, mineral nutrient disruption, and oxidative stress induction, strategic mineral supplementation, particularly with iron, may offer potential mitigation strategies. However, the complexity of mineral interactions suggests that such approaches require careful consideration of antagonistic effects between different nutrients under heavy metal stress conditions.

Conclusion

This investigation demonstrated that iron supplementation can partially mitigate cadmium toxicity in Beta vulgaris, though the protective mechanisms exhibit inherent limitations. Cadmium stress significantly compromised plant physiological processes, including photosynthetic capacity, morphological development, and micronutrient homeostasis. While elevated iron levels provided ameliorative effects against cadmium toxicity, particularly under severe stress conditions, the protection remained incomplete due to persistent competitive interactions between iron and other essential micronutrients. The observed differential tissue distribution patterns, with roots maintaining higher iron concentrations and lower cadmium accumulation compared to aerial tissues, suggest active physiological mechanisms that limit heavy metal translocation to photosynthetic organs. Under non-stressed conditions, moderate iron supplementation enhanced overall plant performance, indicating potential suboptimal iron nutrition in conventional hydroponic systems for B. vulgaris cultivation. These findings have practical implications for agricultural production in cadmium-contaminated environments. Iron amendment represents a viable mitigation strategy for reducing cadmium toxicity symptoms; however, the persistent accumulation of harmful cadmium concentrations in plant tissues presents ongoing food safety concerns. Therefore, iron supplementation should be considered as part of an integrated approach that includes comprehensive soil remediation and continuous monitoring protocols. Future research should elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying iron-mediated cadmium tolerance, particularly focusing on metal transporter regulation and subcellular sequestration processes. Field validation studies across diverse environmental conditions are essential to confirm these controlled environment findings and establish practical application guidelines for commercial production systems. Additionally, investigating long-term effects of iron-cadmium interactions on soil-plant systems would provide valuable insights for sustainable agricultural practices in contaminated environments.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and hydroponic experiment design

This study was carried out under greenhouse conditions at the Pardis Arasbaran greenhouse, Ahar, East Azerbaijan province, Iran (38°28′39″ north latitude and 47°04′12″ east longitude with an altitude of 1360 m). A factorial experiment based on a Completely Randomized Design (CRD) was performed in three replications. Fourteen-liter pots were used as planting containers and filled with sand as the growing medium, which was washed for three days to remove possible salts. To investigate the effects of different concentrations of Cd and Fe in nutrient solution on yield, nutrient quality, and oxidative damage in Beta vulgaris cv. Detroit Dark Red, five seeds (99% purity and 85% germination rate) obtained from ROSSEN SEEDS – Netherlands were sterilized with sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl, 1% (v/v), 5 min), washed with distilled water three times, and finally soaked in distilled water for 15 min before being planted in each pot at a depth of 2.5 cm. For each replication, there were two pots with five seeds in each pot. A total of 54 pots representing nine treatments with three replications (two pots for each replication) were used for the experiment, with five seeds planted in each pot. After planting the seeds, the first irrigation was conducted. The plants were initially irrigated with half-strength Hoagland nutrient solution (pH: 6.6, EC: 1.55 dS m⁻¹; Coolang et al.67) (Table 1). After one week, coinciding with the emergence of the first leaf, 200 mL of Hoagland solution was applied to each pot. Plants were fed and irrigated such that after six days of nutrient solution application per week, the culture medium was washed once weekly. After two weeks and with increased plant growth, plants were fed with complete Hoagland solution (100% concentration). After another two weeks of continued growth, the amount of solution provided to the plants was increased to 300 mL. Overall, the plant growing phase and treatment application lasted for two months.

Nutrient solution and treatments

Subsequently, the plants were subjected to Hoagland nutrient solution supplemented with varying concentrations of Fe (FeSO₄) at three levels (Fe1 (control): 2.5, Fe2: 5, and Fe3: 7.5 mg L⁻¹) and Cd (CdSO₄) at three concentrations (Cd1 (control): 0, Cd2: 1, and Cd3: 2 mg L⁻¹) in the nutrient solution. The pH of the nutrient solution was adjusted to 6.6, and the electrical conductivity (EC) was monitored using an Aqualytic AL10con conductivity sensor, maintaining it at 1.55 dS m⁻¹. For the control group, only Hoagland solution without any additional supplements was used. Each plant received approximately one liter of the respective treatment solution three times per week. The temperature was maintained at 20 ± 2 °C during the day and 18 ± 2 °C during the night, with a relative humidity of approximately 65–70%. Weekly rinsing of the plant substrate was conducted to prevent the accumulation of excess elements. At the end of the experiment, following root formation, leaf and root samples were collected for morphological trait and mineral analyses, while other samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent physicochemical and mineral analyses.

Leaf number and leaf area index (LAI). Leaf numbers were recorded by counting the number of leaves from the beginning of growth until root formation. At the same time, the leaf area index (LAI) of each growth stage was calculated. The formula was as follows: LAI = Sum of all leaf length × width × 0.75/corresponding land area. Leaf Chlorophyll index. The chlorophyll index was determined from five expanded leaves from each pot using a chlorophyll meter (Minolta, SPAD-504, Japan). The chlorophyll index of leaves was measured at 10-day intervals68.

Yield. The yield was determined by weighing the roots of all plants from each treatment.

Leaf and root Zn, Fe, Cu, Cd, and Mn content

Mineral concentration was measured by wet digestion69. The leaf and root samples were washed with deionized water and air-dried. Then, the samples were dried in an oven at 550 °C for 6 h. After cooling to room temperature, 10 mL of 65% HNO₃ was added to the inorganic residue in the crucibles, and they were placed in the digester without heating for 1 day. The next day, the samples were heated at 65 °C for 3 h and then at 110 °C for 3 h. The final clear solutions were filtered with Whatman paper No. 42 and were transferred to a 100 mL volumetric flask and the volume was made up with deionized water. Fe, Zn, Mn, and Cu were determined directly in final digests using atomic absorption spectrophotometry (UV-1800, Shimadzu, Japan). For measuring Cd, after washing leaf and root samples with deionized water, they were placed in an oven (65 °C, 48 h), powdered, digested with HNO₃/HClO₄ at 100 °C and finally kept in a furnace (550 °C, 5 h) to obtain their ash. After cooling down and dissolving the ashes with HCl (10 mL, 2 N), Whatman filter paper (No. 42) was used for filtering them into a volumetric flask (50 mL). Distilled water was added to achieve the final 50 mL volume. Cd content was determined using an atomic absorption spectrometer (Model CTA 3000, ChemTech, UK)70.

H₂O₂ and MDA content of the leaves

For MDA determination, leaf samples (0.1 g) were homogenized in acetic acid (2.5 mL; 10% w/v), and then thiobarbituric acid (0.5% w/v) in trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (20%) was added to the obtained supernatants. The mixture was then incubated at 96 °C for 30 min. After incubation, the mixtures were cooled at 0 °C for 5 min, followed by centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 5 min). The absorbance of the resulting solution was recorded at 532 nm and 600 nm using a spectrophotometer and converted to MDA content71. For H₂O₂ measurement, the supernatant (0.5 mL), obtained from leaf samples (0.5 g) digested with trichloroacetic acid (5 mL, 0.1% w/v) in an ice bath, was mixed with potassium phosphate buffer (0.5 mL, pH 6.8, 10 mM) and potassium iodide (2 mL, 1 M). This mixture was then incubated in the dark for 30 min, and the absorbance was recorded at 390 nm. A standard calibration curve, previously prepared using various H₂O₂ concentrations, was used to calculate the H₂O₂ content72.

Statistics

The factorial experiment was carried out according to a completely randomized design with 3 replications. Data for all parameters were statistically analyzed using MSTAT-C ver 2.1 software**,** and the least significant difference (LSD) method was also used for mean comparison at 5% and 1% probability levels. Pearson correlation and cluster dendrogram heat maps were performed using R foundation for statistical computing (version 4.1.2).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author H.S.H. on reasonable request.

References

Kişi, Ö. River flow modeling using artificial neural networks. J. Hydrol. Eng. 9 (1), 60–63 (2004).

Acharya, S. Heavy metal contamination in food: Sources, Impact, and remedy. In Food Safety and Quality in the Global South (Ogwu, M. C. et al.) 233–261 (Springer Nature Singapore, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-2428-4_8

Kabata-Pendias, A. & Pendias, H. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants (CRC, 2001). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420039900

Li, Y. et al. Effects of different phosphorus fertilizers on cadmium absorption and accumulation in rice under low-phosphorus and rich-cadmium soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31 (8), 11898–11911 (2024).

Yang, J. M. et al. Toward safe rice production in As-Cd co-contaminated paddy soils: biogeochemical mechanisms and remediation strategies. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55 (1), 1–24 (2025).

Zhao, H. et al. Effects of cadmium stress on growth and physiological characteristics of Sassafras seedlings. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 9913. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89322-0 (2021).

Jomova, K., Alomar, S. Y., Nepovimova, E., Kuca, K. & Valko, M. Heavy metals: toxicity and human health effects. Arch. Toxicol. 99 (1), 153–209 (2025).

Sun, X. et al. Nutrient-Element-Mediated alleviation of cadmium stress in plants: mechanistic insights and practical implications. Plants 14 (19), 3081 (2025).

Tsibart, A. S. et al. Scenarios for precision nitrogen management in potato: impact on yield, tuber quality and post-harvest nitrate residues in the soil. Field Crops Res. 319, 109648 (2024).

Peng, H. & Shahidi, F. Cannabis and cannabis edibles: A review. JAFC 69 (6), 1751–1774. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.0c07472 (2021).

Qu, F. & Zheng, W. Cadmium exposure: mechanisms and pathways of toxicity and implications for human health. Toxics 12 (6), 388 (2024).

Vijiyakumar, N. & Prince, S. E. A comprehensive review of cadmium-induced toxicity, signalling pathways, and potential mitigation strategies. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 17, 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13530-024-00243-7 (2025).

Yuan, Z. et al. Research progress on the physiological mechanism by which selenium alleviates heavy metal stress in plants: A review. Agronomy 14 (8), 1787 (2024).

Vitelli, V., Giamborino, A., Bertolini, A., Saba, A. & Andreucci, A. Cadmium stress signaling pathways in plants: molecular responses and mechanisms. Curr. Issues. Mol. Biol. 46 (6), 6052–6068 (2024).

Yağcı, A., Daler, S. & Kaya, O. An innovative approach: alleviating cadmium toxicity in grapevine seedlings using smoke solution derived from the burning of vineyard pruning waste. Physiol. Plant., 176(6), 1–16, e14624. (2024).

Dogan, M. et al. Remediation of cadmium stress in strawberry plants using humic acid and silicon applications. Life, 12(12), 1962. (2022).

Biyani, K., Tripathi, D. K., Lee, J. H. & Muneer, S. Dynamic role of iron supply in amelioration of cadmium stress by modulating antioxidative pathways and peroxidase enzymes in Mungbean. AoB Plants. 11 (2), plz005. https://doi.org/10.1093/aobpla/plz005 (2019).

Kale, R., Sawate, A., Kshirsagar, R., Patil, B. & Mane, R. Studies on evaluation of physical and chemical composition of beetroot (Beta vulgaris L). Int. J. Chem. Stud. 6, 2977–2979 (2018).

Sood, S. & Gupta, N. Beetroot. In Vegetable Crop Science (247–260). CRC Press. (2017).

FAOSTAT. Available online: (2022). https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/qcl (accessed on 2 February 2024).

Ceclu, L. & Nistor, O. V. Red beetroot: composition and health effects—A review. J. Nutr. Med. Diet. Care. 6 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.23937/2572-3278.1510043 (2020).

Ben, H. et al. Betalain and phenolic compositions, antioxidant activity of Tunisian red beet (Beta vulgaris L. conditiva) roots and stems extracts. Int. J. Food Prop. 17 (9), 1934–1945. https://doi.org/10.1080/10942912.2013.772196 (2014).

Sekara, A., Poniedzialeek, M., Ciura, J. & Jedrszczyk, E. Cadmium and lead accumulation and distribution in the organs of nine crops: implications for phytoremediation. J. Environ. Sci. Stud. 14 (4), 509–516 (2005).

Irshad, M. S., Arshad, N., Wang, X., Li, H. R., Javed, M. Q., Xu, Y., … Li, J. Intensifying solar interfacial heat accumulation for clean water generation excluding heavy metal ions and oil emulsions. Solar Rrl. 5(11), 2100427. https://doi.org/10.1002/solr.202100427 (2021).

Pandey, N. & Sharma, C. P. Effect of heavy metals Co2+, Ni2+ and Cd2+ on growth and metabolism of cabbage. Plant. Sci. 163 (4), 753–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9452(02)00210-8 (2002).

Kaya, C., Akram, N. A., Ashraf, M., Alyemeni, M. N. & Ahmad, P. Exogenously supplied silicon (Si) improves cadmium tolerance in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) by up-regulating the synthesis of nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide. J. Biotechnol. 316, 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2020.04.008 (2020).

Wang, H., Zhao, S. C. & Xia, W. J. Effects of cadmium stress at different concentrations on photosynthesis, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzyme activities in maize seedlings. J. Plant. Nutr. Fertil. 14, 36–42 (2008).

Duan, X. et al. Mechanism for Fe (III) to decrease cadmium uptake of wheat plant: rhizosphere passivation, competitive absorption and physiological regulation. Sci. Total Environ. 931, 172907 (2024).

Rydzyński, D., Piotrowicz-Cieślak, A. I., Grajek, H. & Michalczyk, D. J. Chlorophyll degradation by Tetracycline and cadmium in spinach (Spinacia Oleracea L.) leaves. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 16, 6301–6314 (2019).

Zorrig, W. et al. Lettuce (Lactuca sativa): a species with a high capacity for cadmium (Cd) accumulation and growth stimulation in the presence of low cd concentrations. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 88 (6), 783–789. https://doi.org/10.1080/14620316.2013.11513039 (2013).

Ekmekçi, Y., Tanyolac, D. & Ayhan, B. Effects of cadmium on antioxidant enzyme and photosynthetic activities in leaves of two maize cultivars. J. Plant. Physiol. 165 (6), 600–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2007.01.017 (2008).

Chaffei, C. et al. Cadmium toxicity induced changes in nitrogen management in Lycopersicon esculentum leading to a metabolic safeguard through an amino acid storage strategy. Plant. Cell. Physiol. 45 (11), 1681–1693. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pch192 (2004).

Sandalio, L. M., Dalurzo, H. C., Gomez, M. & Romero-Puertas, M. C. Del Rio, L. A. Cadmium‐induced changes in the growth and oxidative metabolism of pea plants. J. Exp. Bot. 52 (364), 2115–2126. https://doi.org/10.1093/jexbot/52.364.2115 (2001).

Hamim, H., Miftahudin, M. & Setyaningsih, L. Cellular and ultrastructure alteration of plant roots in response to metal stress. In Plant growth and regulation-alterations to sustain unfavorable conditions. IntechOpen. (2018). https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.79110

Jorjani, S. & Karakaş, F. P. Physiological and biochemical responses to heavy metals stress in plants. Int. J. Secondary Metabolite. 11 (1), 169–190 (2024).

Qian, H. et al. Combined effect of copper and cadmium on chlorella vulgaris growth and photosynthesis-related gene transcription. Aquat. Toxicol. 94 (1), 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.05.014 (2009).

Wu, F., Wu, H., Zhang, G. & Bachir, D. M. Differences in growth and yield in response to cadmium toxicity in cotton genotypes. J. Plant. Nutr. Soil. Sci. 167 (1), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.200320320 (2004).

Wang, J., Chen, X., Chu, S., Hayat, K., Chi, Y., Liao, X., … Zhang, D. (2024). Conjoint analysis of physio-biochemical, transcriptomic, and metabolomic reveals the response characteristics of solanum nigrum L. to cadmium stress. BMC Plant Biology, 24(1),567.

Andrade, L. R., Farina, M. & Amado Filho, G. M. Effects of copper on Enteromorpha flexuosa (Chlorophyta) in vitro. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 58 (1), 117–125 (2004).

Gonçalves, J. F., Antes, F. G., Maldaner, J., Pereira, L. B., Tabaldi, L. A., Rauber,R., … Nicoloso, F. T. Cadmium and mineral nutrient accumulation in potato plantlets grown under cadmium stress in two different experimental culture conditions. Plant Physiol Biochem. 47(9), 814–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.04.002 (2009).

Sharma, R. K., Agrawal, M. & Agrawal, S. B. Interactive effects of cadmium and zinc on carrots: growth and biomass accumulation. J. Plant. Nutr. 31 (1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904160701741727 (2007).

Złoch, M., Thiem, D., Gadzała-Kopciuch, R. & Hrynkiewicz, K. Synthesis of siderophores by plant-associated metallotolerant bacteria under exposure to Cd2+. Chemosphere 156, 312–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j (2016).

Wang, C., Sun, Q. & Wang, L. Cadmium toxicity and phytochelatin production in a rooted-submerged macrophyte Vallisneria spiralis exposed to low concentrations of cadmium. Environ. Toxicol. 24 (3), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/tox.20429 (2009).

Shao, G., Chen, M., Wang, W., Mou, R. & Zhang, G. Iron nutrition affects cadmium accumulation and toxicity in rice plants. Plant. Growth Regul. 53, 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-007-9201-3 (2007).

Wang, J. et al. Cadmium contamination in Asian rice (Oryza sativa L.): mechanistic insights from soil sources to grain accumulation and mitigation strategies. Plants 14 (18), 2844 (2025).

Komorowska-Trepner, M. & Głowacka, K. The role of silicon compounds in plant responses to cadmium stress: A review. Plants 14 (18), 2911 (2025).

Siddique, A. B. et al. Root iron plaque formation and cadmium accumulation in paddy rice: A Literature-Based study. Cadmium Toxic. Water: Challenges Solutions. 265–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-54005-9_11 (2024).

He, D., Kaleem, Z., Ali, S., Shahbaz, H., Zhang, K., Li, J., … Zhou, W. (2025). Impact of iron oxide nanoparticles on cadmium toxicity mitigation in Brassica napus. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 220, 109500.

Janicka-Russak, M., Kabała, K. & Burzyński, M. Different effect of cadmium and copper on H+-ATPase activity in plasma membrane vesicles from Cucumis sativus roots. J. Exp. Bot. 63 (11), 4133–4142. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ers097 (2012).

Sterckeman, T. & Thomine, S. Mechanisms of cadmium accumulation in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant. Sci. 39 (4), 322–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352689.2020.1792179 (2020).

Reichman, S. M. The Responses of Plants To Metal Toxicity: A Review Forusing on copper, Manganese & Zinc Vol. 7 (Australian Minerals & Energy Environment Foundation, 2002).

Evangelou, M. W., Ebel, M. & Schaeffer, A. Chelate assisted phytoextraction of heavy metals from soil. Effect, mechanism, toxicity, and fate of chelating agents. Chemosphere 68 (6), 989–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.01.062 (2007).

Rezvani, M., Zaefarian, F., Miransari, M. & Nematzadeh, G. A. Uptake and translocation of cadmium and nutrients by Aeluropus littoralis. Arch. Agron. Soil. Sci. 58 (12), 1413–1425. https://doi.org/10.1080/03650340.2011.591385 (2012).

Alengebawy, A., Abdelkhalek, S. T., Qureshi, S. R. & Wang, M. Q. Heavy metals and pesticides toxicity in agricultural soil and plants: Ecological risks and human health implications. Toxics 9(3), https://doi.org/42.10.3390/toxics9030042 (2021).

Vasconcelos, M. et al. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of Transgenic soybean expressing the Arabidopsis ferric chelate reductase gene, FRO2. Planta 224, 1116–1128 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-006-0293-1(2006).

Muneer, S., Kim, T. H. & Qureshi, M. I. Fe modulates Cd-induced oxidative stress and the expression of stress responsive proteins in the nodules of Vigna radiata. Plant Growth Regul 68, 421–433 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-012-9731-1(2012).

Kobayashi, T., Suzuki, M., Inoue, H., Itai, R. N., Takahashi, M., Nakanishi, H., …Nishizawa, N. K. Expression of iron-acquisition-related genes in iron-deficient rice is co-ordinately induced by partially conserved iron-deficiency-responsive elements.J. Exp. Bot. 56(415), 1305–1316. (2005).

Shar, A. G., Zhang, L., Lu, A., Ahmad, M., Saqib, M., Hussain, S., … Rahimi, M. (2025).Unlocking biochar’s potential: innovative strategies for sustainable remediation of heavy metal stress in tobacco plants. Scientifica, 2025(1), 6302968.

Aravind, P. & Prasad, M. N. V. Cadmium-Zinc interactions in a hydroponic system using Ceratophyllum demersum L.: adaptive ecophysiology, biochemistry and molecular toxicology. Braz J. Plant. Physiol. 17, 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1677-04202005000100002( (2005).

Mahmood, Q., Hassan, M. J., Zhu, Z. & Ahmad, B. Influence of cadmium toxicity on rice genotypes as affected by zinc, sulfur and nitrogen fertilizers. Casp. J. Environ. Sci. 4 (1), 1–8 (2006).

Romero-Puertas, M. C. et al. Differential expression and regulation of antioxidative enzymes by cadmium in pea plants. J. Plant. Physiol. 164 (10), 1346–1357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2006.06.018 (2007).

Mittler, R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant. Sci. 7 (9), 405–410 (2002).

Lee, B. R. et al. Peroxidases and lignification in relation to the intensity of water-deficit stress in white clover (Trifolium repens L). J. Exp. Bot. 58 (6), 1271–1279. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erl280 (2007).

Muneer, S., Kim, T. H., Choi, B. C., Lee, B. S. & Lee, J. H. Effect of CO, NOx and SO2 on ROS production, photosynthesis and ascorbate–glutathione pathway to induce Fragaria× annasa as a hyperaccumulator. Redox Biol 2, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2013.12.006(2014.

Behtash, F., Amini, T., Mousavi, S. B., Hajizadeh, S. & Kaya, O. H., Efficiency of zinc in alleviating cadmium toxicity in hydroponically grown lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. cv. Ferdos). BMC Plant. Biol 24(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-024-05325-9(2024).

Coolong, T. W., Randle, W. M., Toler, H. D. & Sams, C. E. Zinc availability in hydroponic culture influences glucosinolate concentrations in Brassica Rapa. Hortic. Sci. 39 (1), 84–86 (2004).

Ling, Q., Huang, W. & Jarvis, P. Use of a SPAD-502 meter to measure leaf chlorophyll concentration in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Photosynth Res. 107, 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-010-9606-0( (2011).

Dong, J., Wu, F. & Zhang, G. Influence of cadmium on antioxidant capacity and four microelement concentrations in tomato seedlings (Lycopersicon esculentum). Chemosphere 64 (10), 1659–1666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.01.030 (2006).

Azimi, F., Oraei, M., Gohari, G., Panahirad, S. & Farmarzi, A. Chitosan-selenium nanoparticles (Cs–Se NPs) modulate the photosynthesis parameters, antioxidant enzymes activities and essential oils in Dracocephalum Moldavica L. under cadmium toxicity stress. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 167, 257–268 (2021).

Kaya, O. Defoliation alleviates cold-induced oxidative damage in dormant buds of grapevine by up-regulating soluble carbohydrates and decreasing ROS. Acta Physiol. Plant. 42 (7), 106 (2020).

Stewart, R. R., & Bewley, J. D. Lipid peroxidation associated with accelerated aging of soybean axes. Plant physiol. 65 (2), 245–248 (1980).

Sinha, S. & Gupta, A. K. Translocation of metals from fly Ash amended soil in the plant of Sesbania Cannabina L. Ritz: effect on antioxidants. Chemosphere 61 (8), 1204–1214 (2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Research Council of the University of Maragheh for financial support of this MS.c research. Also, the authors gave special thanks to staffs of Dept. of Horticultural Science and Central Laboratory of the University of Maragheh for their cooperation and technical assistance.

Funding

The current research has received no funding from agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.B. and H.S.H. conceived and designed the experiments; Z. M. performed the experiments; G.E. Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Software. H.S.H. G.E. and O.K. wrote the first draft of manuscript and proof the final paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Behtash, F., Maghsoudifar, Z., Seyed Hajizadeh, H. et al. Study of cadmium toxicity in iron-supplemented hydroponic solutions on growth parameters, nutritional value and oxidative damage of Beta vulgaris. Sci Rep 15, 44857 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28478-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28478-5