Abstract

Understanding the mechanical behavior of undisturbed loess under different hydraulic paths (wetting followed by loading(W-L) and loading followed by wetting(L-W)) is critical for geotechnical engineering in loess regions. This study investigates the macro–micro deformation characteristics of undisturbed loess using improved triaxial tests, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Grey Relational Analysis, and Pearson correlation analysis. This combined approach quantitatively links macroscopic mechanical responses with microstructural evolution. Grey Relational Analysis and Pearson correlation analysis were used to quantify the coupling between macroscopic mechanical properties and microscopic pore parameters. The results reveal distinct deformation behaviors: the L-W path induces significantly larger deviatoric strain than the W-L path, with strain increasing notably as deviatoric stress rises. Microstructurally,both paths promote the transformation of large and medium pores into small and micropores with increasing stress, accompanied by enhanced pore orientation and reduced morphological complexity. The L-W path intensifies these effects due to stress-induced particle rearrangement followed by wetting-induced effective stress redistribution. Grey Relational Analysis and Pearson correlation analysis confirms that pore orientation (distribution entropy) is the most sensitive to hydraulic paths, followed by pore roundness and abundance, while pore circumference and length exhibit minimal correlation. These findings highlight the critical role of the loading-wetting sequence and provide a quantitative macro–micro framework for assessing moisture-induced deformation risks in loess-region infrastructure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Loess, as an eolian sediment widely distributed in many regions of the world, has attracted much attention in the field of civil engineering because of its unique engineering properties. Especially in China, Central Asia, and parts of the United States1,2,3, Loess forms an important geological foundation and has a profound impact on local infrastructure construction,urban planning and environmental safety. The special properties of loess, such as its porous structure, high compressibility and water sensitivity4. It shows significant mechanical behavior changes when the moisture content changes, and these changes are directly related to the stability and safety of engineering structures5,6,7.

In the engineering practice of yellow land area, the change of water content is the key factor causing the evolution of loess properties. The traditional researches mainly focus on the collapsibility characteristics of loess8, That is,the drastic volume shrinkage and strength reduction of loess after immersion in water9. However, the research on the hydraulic characteristics of soil (such as the migration and distribution law of water in pores) is still insufficient. Hydraulic characteristics are regulated by regulating macroscopic mechanical responses such as the stress–strain relationship,strength parameters and deformation modulus, as well as microscopic mechanisms such as pore structure reconstruction and the evolution of interparticle forces10,11,12,13,14. It is worth noting that the failure mechanism of the internal structure of the soil caused by the wetting-loading sequence (wetting followed by loading (W-L) and loading followed by wetting (L-W)) is extremely complex,and existing studies lack quantitative analysis of hydraulic path effects, particularly in systematically macro–micro coupling mechanisms.

In recent years, research on unsaturated loess has gradually shifted to revealing the intrinsic correlation between macroscopic mechanical behavior and microstructural evolution under multi-field coupling conditions.The researchers controlled the suction by unsaturated triaxial test15,16,17 and scanning electron microscope (SEM) observation18,19,20,21. However, the quantitative coupling relationship between macro and micro parameters is still unclear. Furthermore, the failure mechanism of the internal soil structure induced by the hydraulic sequence is extremely complex, and existing studies lack a systematic quantitative analysis of hydraulic path effects, particularly in terms of integrated macro–micro coupling mechanisms. For this reason, this study introduced the dual methods of Gray correlation analysis and Pearson correlation analysis22,23,24: the former quantifies non-deterministic relationships through gray system theory and the latter reveals linear correlations based on statistical models, which complement each other to enhance the reliability of the coupled macro–micro analysis. The methodology system25,26,27,28,29 has demonstrated powerful multivariate analysis in fields such as materials30, finance31, heat transfer32, machinery33, energy34, water resources35, logistics36, etc.,but its application to loess mechanics is still a frontier exploration.

In this study, the macro and micro deformation characteristics of in situ loess under W-L and L-W paths are investigated systematically through triaxial tests, SEM microscopic observation and multi-scale correlation analysis. The study focuses on the influence of different hydraulic paths on the evolution of void ratio,the development of bias strain and microstructure orientation, and quantitatively depicts the coupling strength between macro-mechanical parameters (e.g.,bias stress and strain) and micro-porous parameters (e.g.,pore size distribution and morphology entropy) through the grey correlation coefficients and the Pearson’s correlation coefficients. The research results not only provide a scientific basis for the prediction of water-sensitive risk of tunnels, slopes and other infrastructures in loess areas,but also construct a framework of macro–micro-coupling analysis for porous media, which will provide a methodological reference for the study of water-sensitive soils in similar geological environments around the world.

Material and methods

Test material and specimen preparation

In order to fully understand the properties of loess in the test site,the soil sampling site is located in Xi 'an Metro Line 5. The depth of the test is about 3–5 m underground. In order to reduce the interference to the soil sample, manual static digging was used,and the soil sample was cut into square soil blocks using an iron saw on site. After the undisturbed loess sample is taken out, it is immediately wrapped in a sealed bag, and then fixed with light-proof tape. The particle composition is shown in Fig. 1.

After the sealing bag was cut open, the soil sample was divided according to the size of the original loess, and at the same time, sawed from the middle according to the natural deposition surface of the soil sample. After the original loess soil sample was divided,the basic physical property indexes of the soil sample(GB/T 50,123–2019)37 were measured (Table 1), and the original loess soil sample was cut into Φ39.1 mm × H80mm specimens using a triaxial chipper, wrapped in cling film and labelled well, and then put into the wetting tank.

Testing procedures

Different hydraulic paths test

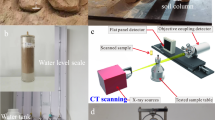

In order to explore the effect of different hydraulic paths on the change of void ratio of the original loess specimen, carries out W-L path as well as L-W path on the original loess. In this test, wetting is carried out by changing the matrix suction of the specimen, and the increase of the moisture content of the specimen is realised by decreasing the value of the matrix suction continuously. This test uses LFTD1808-3 automatic unsaturated soil triaxial instrument produced by Cubic Tongda Company. Since the vertical stresses of W-L and L-W of the current test need to be maintained constant, so it is not applicable to the shear module, and this test was chosen to be carried out in the consolidation stage.

In this experiment,an independent stress-path control module was developed using the instrument’s built-in compensation mechanism, enabling maintenance of specified stresses under varying matric suction conditions. Vertical displacement of the specimen during testing was monitored via a load controller, with the load frame’s displacement calibrated prior to each test to ensure measurement accuracy. To further validate data precision, a high-resolution displacement meter was installed above the pressure chamber, providing independent verification of specimen displacement through cross-referencing with load controller readings, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The tests were conducted along two distinct hydraulic paths: W-L and L-W,simulating real-world engineering scenarios of rainfall preceding construction and construction preceding rainfall, respectively.Under a constant confining pressure of 100 kPa and deviatoric stresses of 50, 100, and 200 kPa, specimens were wetted to saturation along each path. This experimental design replicated in-situ conditions where wetting and loading occur in different sequences. Test data were analyzed to establish relationships between deviatoric stress and deviatoric strain, deviatoric stress and volumetric strain (\({\varepsilon }_{v})\), and deviatoric stress and void ratio (e).

Microstructure test

To explore the deformation mechanisms of undisturbed specimens and those subjected to W-L and L-W paths, this study employs geometric visualization via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to characterize their microstructures. To ensure the accuracy of microscopic analysis, all SEM specimens were selected the central region of samples. Specifically, undisturbed specimens (control group) and specimens after W-L and L-W tests were prepared, with their core sections selected as the primary observation areas to minimize edge effects and ensure representative microstructural evaluation. This approach guarantees that microstructural features reflect true deformation responses under each hydraulic path, providing a reliable basis for correlating macro-deformation with micro-mechanisms. In order to obtain more detailed information as much as possible, the specimens with × 500, × 1000, and × 2000 magnification were selected for specimen observation. After acquiring the SEM images, microstructural parameters were quantified using the Particle (Pore) and Crack Analysis System (PCAS) through a sequential analytical procedure. The process began with image pre-processing, including cropping and contrast enhancement, to improve feature discernment. This was followed by segmentation via thresholding to generate binary images where pores were distinctly identified as white regions against a black particle background. PCAS then automatically measured key geometric parameters—including pore area, perimeter, diameter, roundness, abundance, and orientation. Finally, the data were visualized and statistically analyzed through histograms, scatter plots, and orientation rose diagrams, enabling quantitative comparison of pore characteristics across different hydraulic paths.

Grey relational analysis

This study introduces a statistical analysis model, the grey correlation model, to establish the link between macro and micro. Grey correlation is a measure that describes the correlation between multiple data and factors, and is usually used to analyse data that are complex and do not have a clear relationship. The undisturbed loess sample is taken as the parent sequence of this grey correlation degree model, and the samples with different stress under two hydraulic paths of W-L and L-W are taken as the sub-sequence. The selection of GRA is particularly suited for analyzing the macro–micro coupling in loess due to three key reasons: First, it effectively handles complex, non-linear relationships without requiring strict assumptions about data distribution. Second, it remains robust with limited experimental data points, which is common in detailed microstructural studies. Third, it enables simultaneous comparison of multiple microscopic parameters’ influence on macroscopic behavior, providing a direct sensitivity ranking. While traditional regression analysis requires predefined models and larger datasets, GRA complements Pearson correlation by capturing both linear and non-linear associations in our complex soil system. A1,A2 and A3 are samples under the conditions of W-L deviatoric stress q = 50, 100 and 150 kPa, respectively; B1,B2 and B3 are samples under the conditions of L-W deviatoric stress q = 50,100 and 150 kPa,respectively.X1 represents the average circumference, X2 represents the average length, X3 represents the average roundness, X4 represents the average abundance, and X5 represents the distribution entropy. For this method, the first thing is to determine the parent series and sub-series, which correspond to the reference series and the comparison series, determine the parameters of the two and then compare and analyse the relationship between the two, expressing the relationship between the parent series and the sub-series is shown below22:

The formula is as follows:

where \(\overline{{X_{i} }} = \frac{1}{n}\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{n} {X_{i} }\).In the formula,ρ is the resolution coefficient, ρ ≤ 0.5 under normal circumstances, and the value of ρ in this paper is determined to be 0.5 based on the previous analysis and experience39.

The correlation coefficient ri between Xi and X0 can be calculated by substituting the correlation coefficients of each characteristic into the following formula:

Pearson correlation analysis

The Pearson correlation analysis is widely used to measure the degree of correlation between two variables,with values ranging from 1 to 138. The formula is as follows:

where, X and Y are samples of two variables. The specific method and process are shown in Fig. 3.

Results and discussion

Different hydraulic paths behavior

Figure 4 illustrates the stress–strain responses of undisturbed loess under W-L and L-W paths under a constant confining pressure of 100 kPa. Both paths exhibit a gradual increase in deviatoric strain with rising deviatoric stress, indicating progressive structural disruption within the loess matrix. Notably, the L-W path yields significantly larger deviatoric strain than the W-L path at equivalent stress levels; for example, at q = 150 kPa, the strain under L-W is approximately 25% higher than that under W-L, highlighting the pronounced influence of hydraulic paths on deformation magnitude.

In the W-L path (Fig. 4a), pre-wetting saturates the specimen,filling pores with water before deviatoric loading. While water reduces inter-particle friction and facilitates initial particle movement, the pre-occupied pore space restricts the soil skeleton’s compressibility, limiting the extent of strain development. By contrast, the L-W path (Fig. 4b) involves initial loading in a relatively dry state, during which the soil undergoes stress-induced compression without water lubrication. Subsequent wetting alters inter-particle interactions through two key mechanisms: dissolution of soluble salts weakens particle cementation, and matric suction reduction redistributes effective stress, triggering substantial particle rearrangement. These processes lead to a more pronounced deviatoric strain in the L-W path, as the combination of dry-state structural compression and wetting-induced particle fluidization results in greater deviatoric deformation. The observed disparity in strain behavior between the two paths is consistent with microstructural observations (Section "Microstructure characteristics"), where L-W specimens exhibit more intensive pore refinement and particle contact densification, corroborating the macro-mechanical responses and underscoring the critical role of hydraulic path order in governing loess deformation.

Figure 5(a) demonstrates that under the two different hydraulic paths—W-L and L-W—the volume strain tends to increase with the increase of deviatoric stress.The volume strain under the L-W path experiences a more notable change. Correspondingly, Fig. 5(b), which shows the variation of the void ratio with the deviatoric stress, presents a similar tendency. Even though both paths involve the application of the same deviatoric stress and wetting to the saturation state, the differences and similarities in volume change (void ratio) highlight the effect of hydraulic paths.

For the W-L path, the specimen is pre-saturated,and its pores are completely filled with water. When the deviatoric stress is applied, although the effective stress in the pores changes, the saturation state restricts the change in the void ratio compared with the L-W path. On the contrary, for the L-W path, the specimen is subjected to the deviatoric stress in a relatively dry state. Subsequent wetting causes water to enter these compressed pores, which further alter the distribution and size of the pores,thus causing a more significant change in the void ratio.

The distinct macro-responses under different hydraulic paths are fundamentally controlled by their unique micro-mechanisms. The significantly larger deviatoric strain observed in the L-W path is a direct macroscopic manifestation of more intensive microstructural rearrangement. As quantified in Section "Microstructure characteristics", this path induces greater pore refinement (Figs. 7, 8), a more pronounced development of pore orientation (Fig. 9, Table 2), and a greater reduction in pore roundness and abundance (Fig. 10). These microstructural changes,driven by initial dry compression followed by wetting-induced particle erosion and cementation dissolution,collectively explain the enhanced macroscopic deformation. Conversely, the pre-occupied pore space in the W-L path restricts such extensive particle rearrangement at the micro-scale, leading to the observed limitation of macroscopic strain.

Microstructure characteristics

Microstructure morphology

Figure 6 shows the SEM images of the undisturbed sample in Xi 'an and the samples of W-L, and the samples of L-W at multiples of 500, 1000, and 2000. Under the magnification of 500 times, the whole picture of Xi 'an undisturbed loess samples can be clearly observed, and the pores of the samples are large, which is because the pores of the samples themselves are relatively large, but it is difficult to observe the details of the connection mode and contact form. Under the condition of 2000 times, the pore distribution on the sample surface can be clearly observed, such as the contact mode between particles and the size of pores. These features are exactly in line with the size range of the study, so this paper selects images with a magnification of 2000 times for research.

SEM images and corresponding PCAS binary processing results of specimens under different conditions. Notes:The labels in the images are defined as follows: A1 and A2 indicate typical soil aggregates; P1, P2, and P3 mark representative pores of varying sizes; The blue arrows at C1and C2 highlight characteristic particle-to-particle contact points.

Figure 6(a) shows that the undisturbed samples are characterized by many pores, large pores, and wide and uneven distribution of pore ranges. Figure 6(b)(c) shows the changes of samples subjected to two different hydraulic paths. It can be observed from the Fig.that the pores of the two soils become smaller and the contact points between particles increase. This phenomenon indicates that hydraulic paths does affect the arrangement of soil particles inside the sample, and substances such as easily dissolved rocks in the soil are dissolved. Under the action of external forces, large particles are squeezed and crushed into smaller particles to fill the soil skeleton,making the soil skeleton more dense.

In the Fig. 6, the yellow parts of A1 and A2 indicate the aggregate existing in the soil, and the red parts of P1, P2 and P3 indicate the size of pores in the soil. It can be observed that the aggregate and pores in the soil gradually decrease with the increase of stress. The blue arrows of C1 and C2 indicate the contact position between soil particle surface and surface, which presents a different state with the change of hydraulic paths. The W-L path leads to reduced friction between soil particles, easy to slide and less contact on all sides, while the L-W path leads to closer contact with particles and more contact on all sides due to the loading first.

Pore area distribution

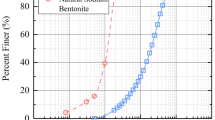

In this study, PCAS software is used to process SEM images. Firstly, the image is preprocessed and segmented. The second is the measurement of the parameters, which can obtain the diameter, area, perimeter and fractal dimension of the pore. Finally, the image is visualized, and the distribution of particles and pores is visually displayed by histogram, scatter plot, three-dimensional map and other forms. At the same time, the pore distribution method of Lei was used in this study, and the pores were divided into four categories40. (1) The pores with a diameter greater than 32 \(\mu {\text{m}}\) were macropores; (2) Medium pores with diameters between 8 and 32 \(\mu {\text{m}}\); (3) Small pores with diameters between 2 and 8 \(\mu {\text{m}}\); (4) Those with a diameter less than 2 \(\mu {\text{m}}\) are micropores.

Figure 7 presents the statistical calculation results of each pore area proportion. The histogram represents the proportion of each pore area to the total image area; the line chart shows the total pore area, and the pie chart illustrates the proportion of each pore area in the total pore area. Figure 7 quantitatively describes the pore changes under different hydraulic paths. It can be observed that in undisturbed loess samples, the proportion of medium pores is relatively large, while that of small and micro pores is relatively small. Through different hydraulic paths, large and medium pores transform into small and micro pores. Notably, the medium pore proportion decreases most typically, from 22.91 to 10.94% (W-L path) and 7.74% (L-W path). This phenomenon fully demonstrates that with the evolution of the stress path, large and medium pores in the soil gradually break into small and micro pores, making the arrangement of soil particles denser41.

By comparing Fig. 7(a) and (b), under different hydraulic paths (W-L and L-W), the pore area occupied in the bipolar diagram shows distinct differences, and this discrepancy becomes more pronounced with the increase of deviatoric stress. Additionally, the void ratio varies more significantly in the L-W path, indicating that the differences between the W-L and L-W hydraulic paths have a notable impact on the void ratio changes of the samples. For the W-L path, the sample is first saturated with water, where fine particles and suspended matter in the soil are wrapped by water and soluble salts are dissolved. Subsequently, under the action of deviatoric stress, large and medium pores are compressed, and some suspended matter is trapped in the pores before it can escape. In contrast, for the L-W path, the sample first undergoes external force, causing large and medium pores to break into small and micro pores, and then is saturated with water. Fine particles in the soil are washed away under long-term water erosion,and soluble salts are fully dissolved, leading to significant changes in pores after loading and wetting.

Pore diameter distribution

Figure 8 depicts the pore-distribution changes under the W-L and L-W paths. From the images,it is evident that with the increase of deviatoric stress, the pore size of specimens under both paths decreases, and the Average Pore Diameter (APD) follows the same trend38. For the W-L path,the pore diameter distributes in the ranges of 0 ~ 77.8, 0 ~ 39.6, 0 ~ 36.5 and 0 ~ 35.1 \(\mu {\text{m}}\), with APD values of 30.96, 13.98, 12.46 and 11.16 \(\mu {\text{m}}\).For the L-W path, the pore-diameter distributions are 0 ~ 77.8, 0 ~ 38.6, 0 ~ 35.9 and 0 ~ 33.9 \(\mu {\text{m}}\), with APD values of 30.96, 13.57, 11.43 and 8.86 \(\mu {\text{m}}\).

Notably, under the same deviatoric stress, the APD in the L-W path is consistently smaller than that in the W-L path. This reveals the distinct influence of hydraulic paths: In the W-L path, pre-wetting fills some pores with water, limiting the extent of pore compression during subsequent loading. In contrast, the L-W path involves initial loading that compresses pores in a relatively dry state, and subsequent wetting promotes water erosion and dissolution of soluble substances. This dual action in the L-W path further refines and reduces pore sizes, making the pore structure denser.

Pore orientation distribution

Figure 9 presents the pore-orientation diagrams under different deviatoric stresses for the two hydraulic paths (W-L and L-W). From the pore rose diagrams, it can be observed that under both hydraulic paths, the directional distribution of pores in loess becomes more pronounced with the increase of deviatoric stress. For instance, in Fig. 9, as the deviatoric stress increases, the proportion of pore distribution in certain directions (such as 150° ~ 160°) grows, indicating that under the combined action of wetting and loading,pores develop directionally, evolving from a widespread distribution at the beginning to concentration in several directions, with gradually strengthened orientation38.

Pore orientation distribution under different deviatoric stresses for (a) W-L and (b) L-W paths. The rose diagrams illustrate the directional preference of pores. The radial distance from the center in each angular segment (10° intervals) represents the percentage of the total number of pores oriented within that directional range.

In order to further quantify the orientation distribution of loess pores, probabilistic entropy Hm is chosen in this paper42:

where Pi is the probability of pores appearing in a certain region, and n represents the number of regions. In this paper, n is divided into 18 parts, each of which is 10 degrees, and the direction of pores is described from 180°. Hm is the value between 0 and 1. The larger the value, the more disordered the pore arrangement and the worse the pore orientation.

Table 2 lists the directional entropy calculated for the two paths, with Hm ranging from 0.9235 to 0.9913. In the L-W path, the Hm value gradually decreases with the increase of deviatoric stress, suggesting that initial loading arranges particles preliminarily, and subsequent wetting promotes more orderly directional development of pores. In contrast, the Hm value of the W-L path is relatively higher, indicating that pre-wetting disperses the initial pore distribution. Although subsequent loading enhances the directionality, the overall orderliness is less than that of the L-W path. This highlights the significant impact of hydraulic paths on the orderliness of pore structures: in the L-W path, the process of loading first and then humidifying makes pores more orderly under the compression of stress and the action of water; in the W-L path, pre-wetting fills pores,restricting particle movement during loading and resulting in a different degree of pore-order development. The specific data in Table2 further confirm this: for the W-L path, Hm decreases from 0.9913 to 0.9425 as deviatoric stress increases from 50 to 150 kPa; for the L-W path, Hm decreases from 0.9511 to 0.9235 in the same stress range, clearly showing the distinct evolution of pore orderliness under different hydraulic paths.

Pore morphology distribution

In this paper,roundness and abundance were introduced to quantitatively evaluate the pore shape distribution. The formula is as follows43,44:

where, Ap is the hole area, Pp is the hole perimeter, Wp and Lp are the short and long axes of the hole. The values of both parameters are in the 0–1 range. The closer the roundness and abundance are to 1, the rounder the pore shape.

Figure 10 illustrates the distribution of pore morphology parameters—roundness and abundance—for the W-L and L-W paths. Under both paths, abundance values range from 0.15 to 0.90, with the average abundance exhibiting a decreasing trend. Roundness values span from 0.05 to 0.90, and the average roundness also shows a downward trend. This indicates that as deviatoric stress increases, pores tend to break,reflecting the significant influence of hydraulic paths on pore-structure evolution. For the W-L path, pre-wetting saturates the soil, filling pores with water. When deviatoric stress is applied, water reduces inter-particle friction, but pre-occupied pores limit extensive particle rearrangement, resulting in a specific pattern of pore breakage. In contrast, the L-W path involves initial loading in a relatively dry state, compressing pores. Subsequent wetting promotes particle erosion and salt dissolution, intensifying pore breakage. Notably, the average abundance and roundness decrease more markedly in the L-W path. This reveals that the sequence of hydraulic paths profoundly shapes pore morphology. The W-L path, with pre-wetting, constrains pore breakage due to water-filled pores, while the L-W path, with post-loading wetting, enhances pore breakage through erosion and stress-water interaction. This analysis underscores how hydraulic-path sequence uniquely governs pore-structure changes, highlighting its critical role in soil-deformation mechanisms.

Grey relational analysis

Figure 11 shows the grey correlation degree between the microstructure parameters of loess (circumference,length,roundness,abundance,Hm) and the macroscopic mechanical response under the W-L and L-W paths. The correlation degree of particle orientation Hm is the highest (W-L:0.807,L-W:0.845), indicating that the particle orientation in the direction of the principal stress is the core of macro-microscopic coupling. In the L-W path, loading first induces orientation, and wetting strengthens the anisotropy of the composition, making Hm more closely related to the macroscopic response. The abundance of aggregates in the W-L path (0.779) was higher than that in the L-W (0.681), because the wetting first disrupted the cementation of aggregates, and the dispersed particles were reconstructed during loading. The roundness of the particles in the L-W path (0.689) was higher than that in the W-L (0.632), reflecting that when L-W, the stress wear and water hydration jointly accelerate the roundness of the particles, which is greatly affected by the macroscopic strength.

The L-W path has a higher correlation for all parameters except abundance Hm difference 0.038, roundness difference 0.057). The W-L path has higher correlation of abundance, because wetting first disperses the agglomerates and weakens the stress skeleton, the particles are more likely to slide when loading, and the orientation of the particles is weaker due to water lubrication, which is characterized by preferential infiltration of water and then destroying the initial structure.

Pearson correlation analysis

Figure 12 Pearson correlation analysis of macro–micro parameters in W-L and L-W paths reveals that deviatoric stress strongly correlates with deviatoric strain \({\varepsilon }_{d}\)(W-L:\(\rho\) = 1.00,L-W:\(\rho\) = 0.99), reflecting direct stress–strain coupling, while void ratio and total pore area \(P_{{{\text{total}}}}\) show strong negative correlations with deviatoric stress(W-L:\(\rho\) = − 0.96/ − 1.00,L-W:\(\rho\) = − 0.98/ − 1.00), indicating stress-induced pore volume reduction. \(P_{{{\text{total}}}}\) is negatively related to the deviatoric stress (\(\rho\) = − 1.00), and highlights the absolute control of stress over the total pore; \(P_{{{\text{mac}}}}\)/\(P_{{{\text{mes}}}}\) is negatively related to the deviatoric stress(W-L:\(\rho\) = − 0.96/-0.99,L-W:\(\rho\) = − 0.99/ − 1.00), \(P_{{{\text{sma}}}}\) was strongly positively correlated with deviatoric stress(\(\rho\) = 1.00), revealing the reconstruction mechanism of compression of macropore and proliferation of small pores during loading, recombination preferred to fill the microscopic pores under the hydraulic path. Hm is negatively related to the deviatoric stress (W-L:\(\rho\) = − 0.95,L-W:\(\rho\) = − 0.94), W-L to wetting slippery make particles are more likely to slip, orientation degradation is more prominent; Abundance is negatively related to the deviatoric stress (W-L:\(\rho\) = − 0.98,L-W:\(\rho\) = − 0.98), L-W hydraulic coupling dispersion strengthening disintegration of aggregate and orientation. Roundness is negatively related to the deviatoric stress (W-L:\(\rho\) = − 0.98,L-W:\(\rho\) = − 0.94), W-L hydraulic action accelerate grinding roundness reduce together. The abundance is negatively correlated with deviatoric stress (\(\rho\) = -0.98), and the coupling of the two paths is similar, reflecting the universality of stress-damaged aggregates.

The increase of W-L \(P_{{{\text{sma}}}}\) is positively correlated with deviatoric stress (\(\rho\) = 1.00) and the deterioration of roundness (\(\rho\) = -0.98) are more significant, reflecting the weakening of cementation by wetting and the particle evolution dominated by fine particles and rounded surfaces produced by loading. L-W \(P_{{{\text{mac}}}}\)/\(P_{{{\text{mes}}}}\) compression negative correlation is more obvious, and deviatoric stress (\(\rho\) = − 0.99/ − 1.00), orientation degree of belong stronger. It reflects the mechanism that the oriented aggregates loaded are more prone to disintegration after wetting, with more severe macroscopic pore compression and anisotropic deterioration of the composition, and the stress-oriented composition is more sensitive to water erosion.

Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the macro–micro deformation mechanisms of undisturbed loess under W-L and L-W hydraulic paths. The key findings are:

-

1)

The L-W path induces significantly larger deviatoric strain than the W-L path, resulting from stress-induced compression followed by wetting-induced particle rearrangement.

-

2)

Void ratio evolution is more pronounced under the L-W path, highlighting the critical role of wetting-loading sequence.

-

3)

Microstructurally, both paths promote the transformation of large and medium pores into small and micropores, with the L-W path intensifying pore refinement and directional alignment.

-

4)

Grey relational and Pearson correlation analyses consistently identified pore orientation (distribution entropy) as the most sensitive micro-parameter to hydraulic paths. These findings underscore the importance of hydraulic path sequence in assessing loess deformation risks and provide a quantitative macro–micro coupling framework for porous media.

While this study elucidates the hydro-mechanical behavior of loess under fundamental hydraulic paths, its limitations,including simplified laboratory conditions, static microstructural snapshots, and limited chemical analysis,suggest the need for future work. Research should advance toward simulating complex field cycles, developing real-time microstructural monitoring, and incorporating chemical–mineralogical effects to establish a more comprehensive framework applicable across diverse loess regions.

Data availability

The raw datasets for Grey Relational Analysis and Pearson correlation analysis, all derived from macro experiments, are available in the Mendeley Data repository: Fu, Weiye (2025), “Macro and micro deformation characteristics analysis under different hydraulic paths”, Mendeley Data, V2, https://doi.org/10.17632/dttzrf9wch.2.

References

Ding, Z. L. et al. Wind-blown origin of the Pliocene red clay formation in the central Loess Plateau. China. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 161(1–4), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(98)00145-9 (1998).

Maher, B. A. Palaeoclimatic records of the loess/palaeosol sequences of the Chinese Loess Plateau. Quatern. Sci. Rev. 154, 23–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.08.004 (2016).

Pye, K. The nature, origin and accumulation of loess. Quatern. Sci. Rev. 14(7–8), 653–667 (1995).

Leng, Y., Peng, J., Wang, S. & Lu, F. Development of water sensitivity index of loess from its mechanical properties. Eng. Geol. 280, 105918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2020.105918 (2021).

Zuo, L., Xu, L., Baudet, B. A., Gao, C. & Huang, C. The structure degradation of a silty loess induced by long-term water seepage. Eng. Geol. 272, 105634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2020.105634 (2020).

Qiu, J. et al. Influence of fissure-induced linear infiltration on the evolution characteristics of the loess tunnel seepage field. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 162, 106640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2025.106640 (2025).

Tang, K. et al. Experimental investigation on deformation-failure mechanisms of a shallow-bias large-section loess tunnel induced by rainfall. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 157, 106253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2024.106253 (2025).

Francisca, F. M., Giomi, I. & Rocca, R. J. Inverse analysis of shallow foundation settlements on collapsible loess: Understanding the impact of varied soil mechanical properties during Wetting. Comput. Geotech. 167, 106090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2024.106090 (2024).

Rodrigues, R. A., Prado Soares, F. V. & Sanchez, M. Settlement of footings on compacted and natural collapsible soils upon loading and soaking. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 147(4), 04021010. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0002479 (2021).

Assadi-Langroudi, A., Ng’ambi, S. & Smalley, I. Loess as a collapsible soil: Some basic particle packing aspects. Quatern. Int. 469, 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2016.09.058 (2018).

Cai, G. et al. Wetting-induced deformation characteristics of unsaturated compacted sandy loess. Acta Geotech. 19(1), 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-023-01891-8 (2024).

Wu, H., Shao, S., Shao, S., Wang, Z. & Yan, G. Cyclic loading deformation response and microstructure evolution of undisturbed loess subjected to pre-wetting process. Eng. Geol. 337, 107573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2024.107573 (2024).

Wang, J., Zhang, D., Wang, N. & Gu, T. Mechanisms of wetting-induced loess slope failures. Landslides 16(5), 937–953. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-019-01144-4 (2019).

Zhang, D., Wang, J., Chen, C. & Wang, S. The compression and collapse behaviour of intact loess in suction-monitored triaxial apparatus. Acta Geotech. 15(2), 529–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-019-00829-3 (2020).

Jiang, M., Hu, H. & Liu, F. Summary of collapsible behaviour of artificially structured loess in oedometer and triaxial wetting tests. Can. Geotech. J. 49(10), 1147–1157. https://doi.org/10.1139/t2012-075 (2012).

Zhang, F. & Wang, G. Effect of irrigation-induced densification on the post-failure behavior of loess flowslides occurring on the Heifangtai area, Gansu, China. Eng. Geol. 236, 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2017.07.010 (2018).

Zhou, Y. F., Tham, L. G., Yan, W. M., Dai, F. C. & Xu, L. Laboratory study on soil behavior in loess slope subjected to infiltration. Eng. Geol. 183, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2014.09.010 (2014).

Garakani, A. A., Haeri, S. M., Khosravi, A. & Habibagahi, G. Hydro-mechanical behavior of undisturbed collapsible loessial soils under different stress state conditions. Eng. Geol. 195, 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2015.05.026 (2015).

Liu, Z. et al. Collapsibility, composition, and microstructure of loess in China. Can. Geotech. J. 53(4), 673–686. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2015-0285 (2016).

Luo, H., Wu, F., Chang, J. & Xu, J. Microstructural constraints on geotechnical properties of malan loess: A case study from Zhaojiaan landslide in Shaanxi province, China. Eng. Geol. 236, 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2017.11.002 (2018).

Mu, Q. Y., Zhou, C. & Ng, C. W. W. Compression and wetting induced volumetric behavior of loess: Macro- and micro-investigations. Trans. Geotechn. 23, 100345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2020.100345 (2020).

Julong, D. Introduction to grey system theory. J. Grey Syst. 1(1), 1–24 (1989).

Li, G.-D., Yamaguchi, D. & Nagai, M. A grey-based decision-making approach to the supplier selection problem. Math. Comput. Model. 46(3–4), 573–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcm.2006.11.021 (2007).

Olson, D. L. & Wu, D. Simulation of fuzzy multiattribute models for grey relationships. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 175(1), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2005.05.002 (2006).

Wei, G. Grey relational analysis model for dynamic hybrid multiple attribute decision making. Knowl.-Based Syst. 24(5), 672–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2011.02.007 (2011).

Wei, G.-W. GRA method for multiple attribute decision making with incomplete weight information in intuitionistic fuzzy setting. Knowl.-Based Syst. 23(3), 243–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2010.01.003 (2010).

Wu, D. D. Supplier selection in a fuzzy group setting: A method using grey related analysis and Dempster-Shafer theory. Expert Syst. Appl. 36(5), 8892–8899 (2009).

Xu, Z. On multi-period multi-attribute decision making. Knowl.-Based Syst. 21(2), 164–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2007.05.007 (2008).

Zhang, J., Wu, D. & Olson, D. L. The method of grey related analysis to multiple attribute decision making problems with interval numbers. Math. Comput. Model. 42(9–10), 991–998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcm.2005.03.003 (2005).

Vignesh, R. & Abdul Rahim, A. Emerging eco-friendly fiber-reinforced concrete with shaped synthetic aggregates using Taguchi grey relational analysis and utility concept. Constr. Build. Mater. 447, 138039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.138039 (2024).

Gu, Y. et al. Analysis of factors influencing hospitalization expenses of patients with gastric cancer in Shanghai, 2014–2021: based on grey relational analysis and structural equation modeling. Value in Health Reg. Issues 44, 101029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vhri.2024.101029 (2024).

Liu, H. & Chang, Z. Multi-objective optimization of temperature uniformity in the immersion liquid cooling cabinet with Taguchi-based grey relational analysis. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer 154, 107395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2024.107395 (2024).

Ahmad, A. et al. Achieving sustainable machining of titanium grade 3 alloy through optimization using grey relational analysis (GRA). Res. Eng. 23, 102355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102355 (2024).

Yang, C. et al. Multi-objective optimization and influence degree analysis of the thermally integrated HP-ORC carnot battery based on the orthogonal design method and grey relational analysis. Energy 311, 133360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2024.133360 (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. Groundwater dynamics clustering and prediction based on grey relational analysis and LSTM model: A case study in Beijing Plain China. J. Hydrol: Reg. Stud. 56, 102011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2024.102011 (2024).

Wu, G., Hu, Y.-C., Chiu, Y., Jiang, P. & Chi, R. Forecast combination using grey relational analysis and Choquet fuzzy integral for container throughput forecasting. Expert Syst. Appl. 252, 124170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124170 (2024).

Mohurd, P. (2019). Standard for geotechnical testing method GB/T. China Planning Press, Beijing, pp.50123–52019. (GB/T 50123–2019)

Nie, Y., Ni, W., Lü, X., Tuo, W. & Yuan, K. Macroscopic mechanical behavior and microstructural evolution of compacted loess in the Chinese Loess Plateau. Soil and Tillage Research 232, 105767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2023.105767 (2023).

Zhang, S., Lövdahl, L., Grip, H. & Tong, Y. Soil hydraulic properties of two loess soils in China measured by various field-scale and laboratory methods. CATENA 69(3), 264–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2006.06.005 (2007).

Lei, X. The types of loess pores in China and their relationship with collapsibility. Sci. China Ser. B 17(12), 1309–1318 (1987).

Zhu, H. et al. Diagenetic controls on the reservoir quality of fine-grained “tight” sandstones: a case study based on NMR analysis. Energy Fuels 32(2), 1612–1623. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b03734 (2018).

Zhou, C., Cui, G., Liang, W., Liu, Z. & Zhang, L. A coupled macroscopic and mesoscopic creep model of soft marine soil using a directional probability entropy approach. J. Marine Sci. Eng. 9(2), 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse9020224 (2021).

Kong, D. et al. Study on coupling effect of soil structure and overconsolidation on mechanical properties of loess. PLoS ONE 19(3), e0298653. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298653 (2024).

McGlynn, I.O., Fedo, C.M., & McSween, H.Y. (2011). Origin of basaltic soils at Gusev crater, Mars, by aeolian modification of impact-generated sediment. Journal of Geophysical Research. 116: E00F22. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JE003712

Funding

Fund Name: 1.Guizhou Provincial Natural Science Foundation Project. 2.National Natural Science Foundation of China. Project Number: 1.Qiankehe Foundation -ZK[2024] General 600. 2.Grant Nos. U24432122.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.F. designed and performed the experiments (triaxial tests, SEM observations) and analyzed the primary data. S.S. supervised the experimental design and provided technical guidance on geotechnical testing. F.S. contributed to the microstructural analysis using PCAS software and interpreted pore evolution characteristics. A.L. conceived the study, led the research framework, and drafted the manuscript. Z.Z. assisted with data processing for grey relational and Pearson correlation analyses. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, W., Shao, S., She, F. et al. Macro–micro deformation characteristics of undisturbed loess under different hydraulic paths. Sci Rep 15, 44739 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28544-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28544-y