Abstract

The objective of this study was to explore whether milk mid-infrared (MIR) spectral patterns could reflect physiological responses to improved housing conditions aimed at enhancing dairy cow comfort and ease of movement. Three controlled animal trials were conducted to test the effects of housing modifications related to tie chain length (TCL), stall width (SW), and a combination of manger wall and stall length (MW/SL). A hybrid analytical approach combining principal component analysis (PCA) and mixed models was applied to identify spectral differences across treatments. In all three trials, housing modifications were associated with significant differences in spectral patterns, even in the absence of major shifts in traditional milk composition metrics. For example, cows with longer chains (TCL trial) showed spectral trends suggestive of changes in components such as milk non-protein nitrogen (NPN), trans fatty acids, fat, and protein, which aligned with patterns reported in association with changes in rumen pH. These results were consistent with concurrent behavioral observations indicating improved comfort. This study provides preliminary evidence that milk MIR spectra may be sensitive to subtle physiological changes linked to housing design, with differences observed between the most and least restrictive treatments, translating into improved or reduced animal welfare status. While not intended as a predictive tool for welfare status, the approach offers a non-invasive framework for investigating animal–environment interactions. Limitations related to sample size and scope are acknowledged, and further work is needed to validate these findings across larger and more diverse populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Animal welfare is increasingly becoming a concern for dairy producers and society in general; hence, more research has been conducted to improve the different aspects of animal welfare1. According to the World Organization of Animal Health, an animal that experiences good welfare is one that is “healthy, comfortable, well nourished, safe, is not suffering from unpleasant states such as pain, fear and distress, and is able to express behaviours that are important for its physical and mental state.”2. Based on this definition, the tie stall housing system of dairy cows has been criticized for its restrictions that it imposes on the cows’ ability to move and to engage with social interactions with other cows3, and for higher prevalence of lameness and cow comfort issues, which negatively affects cow welfare, public perceptions, and producer profitability4. Nevertheless, the tie stall system remains a prevailing housing system for dairy cows in North America. For example, in Canada it accounts for 73.8% of dairy operations in farms3. The current study is part of a comprehensive study conducted over a 3-yr period aimed at investigating the individual effect of different stall design aspects on ease of movement and comfort of dairy cows housed in tie stalls. The studied elements of the stall design that were covered by this comprehensive study were the tie-rail height and forward position5, the chain length (TCL)3, the stall width (SW)6 and the combined effect of stall length and manger height (MW/SL)7. To assess the effects of modifying those elements on cow ability to move and comfort, multiple outcomes were measured during each trial including injury scores5,7, resting behaviour3,5,6,7, lying down and rising events3,5,6,7, tracking cow’s movement in the stall3 and postures and position in space of head, body and limbs during lying hours6. While these outcomes remain the accepted measures to evaluate animal comfort and welfare in dairy housing systems4, we hypothesize that cows’ comfort improvement, even if modest, might lead to physiological changes, which might be reflected in milk chemical composition. However, affected milk components might not necessarily be those that are currently reported in dairy herd improvement (DHI) programs; hence, we decided to mine milk midinfrared (MIR) spectra to study the changes in milk composition that can be attributed to changes in the housing environment.

Milk MIR spectra contain signals from all molecules present in milk that can absorb MIR energy; therefore, milk MIR spectra represent a comprehensive snapshot of the milk’s chemical composition and some of its physical attributes. In a previous publication8, we presented a novel hybrid approach for spectral analysis that combined mixed modeling and multivariate analysis of milk Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra in which we attributed changes in milk composition to modifications to the tie-rail of a tie stall described elsewhere5. Using this approach, we identified treatment-related patterns in FTIR spectra, independent of milk analyzer vendor-predicted analytes. In that study (focused on tie-rail design), a specific principal component was associated with changes in energy metabolism–related milk components (e.g., β-hydroxybutyrate, acetone, and citrate) suggesting that cows in a specific tie-rail configuration treatment were experiencing higher level of body fat mobilization. These finding matched concurrent increases in neck injuries, suggesting limited feed access5. We concluded that analyzing milk FTIR spectra directly, without relying on predicted values of any analyte of interest, was a viable option for capturing changes in milk composition attributable to modifications in housing conditions. This conclusion was based on our findings in the first trial of the current study8, which demonstrated that this hybrid approach could successfully detect physiologically meaningful differences in milk spectra linked to tie-rail design, a result supported by behavioral and injury data collected in that same trial. Considering that minor milk components such as BHB and urea are predicted from overlapping regions of the FTIR spectrum, and that vendor-provided prediction models for these components are known to have limited accuracy, we opted not to use those predicted values as inputs in our analysis. Instead, we used PCA to extract orthogonal components from the spectra for modeling treatment effects. This allowed us to avoid potential collinearity or redundancy in the analysis, while still enabling biological interpretation of the results.

The objective of this paper is to explore whether similar spectral patterns emerge across three other housing trials — TCL, SW, and MW/SL. More specifically, this approach will be evaluated for its potential to capture a milk spectral fingerprint associated with cow comfort, which could later be used to provide indications of specific welfare-related aspects — a direction for future investigation. Importantly, all housing modifications in these trials were designed to enhance, not impair, cow movement and comfort. Thus, any resulting changes in milk spectra are expected to be subtle, not dramatic. Routine animal welfare outcomes were used to categorize the level of animal comfort and ease of movement (i.e., improved or not) provided by each housing treatment (fully reported elsewhere6,7 and key findings will be used in this manuscript to support any trends detected by the hybrid analysis approach of spectral data.

This is an exploratory study, and no claims are made about developing predictive models of cow welfare. Instead, we aim to determine whether changes in housing design known to influence behavior correspond to detectable differences in milk spectra, using an approach that is biologically interpretable, non-invasive, and potentially scalable.

The current paper is, to our knowledge, the first to apply milk FTIR spectral analysis in a controlled, stall-design trial setting focused on cow comfort. It highlights how housing changes can be reflected in milk composition, contributing a novel angle to the growing body of welfare research. While limited in sample size and scope, this study represents an initial step toward integrating milk-based spectral information into broader efforts to monitor and understand animal–environment interactions.

Materials and methods

Experimental setup

A series of trials have been conducted to test different housing treatments intended to improve the level of comfort and welfare of individual cows by increasing the opportunity of movement given to the cow in her stall. The animal trials were conducted at the Macdonald Campus Dairy Complex of McGill University (Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, QC, Canada) using animals from the dairy herd. Details on the experimental setup and animal handling can be found elsewhere3,6,7. Use of animals and all procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee of McGill University and affiliated hospitals and research institutes (protocol #2016–7794), and all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

In this section, the experimental setups of the 3 trials are briefly described. An overview of the housing configuration treatments is shown in Table 1. From hereafter, T1 will be referring to the control configuration of the tie stall element and T2 will be referring to the suggested modification to that element.

Trial 1: chain length configuration

Twenty-four lactating Holstein cows were assigned to 2 tie chain length (TCL) treatments. T1 was the control, and T2 was a suggested treatment intended to increase the cow’s movement ability in her stall3 (Table 1). Cows were assigned to 12 different blocks of two cows to account for age of the cow (i.e., parity or number of lactations) and days in milk within current lactation (average DIM 129) and were placed evenly in two rows facing a wall within the barn. Five cows (4 long chain, 1 control) were removed at different points (1 in week 6, 1 in week 8, 2 in week 9, and 1 in week 10) during the trial for different reasons3. The trial lasted for 10 weeks from February 20, 2017, to May 1, 2017. Full experimental design is available elsewhere3.

Trial 2: stall width configuration

Sixteen lactating Holstein cows were assigned to 2 stall width (SW) treatments. T1 was the control and T2 was a suggested treatment intended to increase the cow’s comfort, and specifically cow’s rest, in her stall6 (Table 1). Cows were assigned to 8 blocks of 2 cows to account for age of the cow (i.e., parity or number of lactations) and days in milk within current lactation (average DIM: 157) and were placed evenly in two rows within the barn. The trial lasted for 6 weeks from June 5, 2017, to July 17, 2017. Full experimental design is available elsewhere6.

Trial 3: manger wall and stall length configuration

The lengths of two rows in the barn were modified as follows: row 1 was 178 cm (i.e., short or L1), which is the length commonly found on Quebec’s farms, and row 4 was 188 cm (i.e., long or L2), which was a suggested modification. Two manger wall heights were applied randomly to stalls within each row: T1, which was the upper limit of the recommendation, and T2 (Table 1). Twenty-four cows were randomly divided into 4 groups. Two groups were assigned to each row and subjected to both manger wall treatments in a crossover design (1 week for adaptation, 6 weeks of data collection per treatment). Cows were assigned to 6 different blocks to account for age of the cow (i.e., parity or number of lactations) and days in milk within current lactation. Increasing the stall length and reducing the manger wall increased the space available for the cow, which eased her movement and lying, thus reducing her susceptibility to injuries7. The trial lasted for 14 weeks from February 26, 2018, to June 4, 2018. All 24 cows enrolled in the study remained in the final data set for period 1, but 3 were removed from period 27. Full experimental design is available elsewhere7. This trial will be referred to as MW/SL in this paper.

Milk component analysis

One composite milk sample per week was collected from each cow participating in the trials. The sample consisted of equal volumes (i.e., a 50:50 mix) of milk collected during the evening milking and the morning milking of the next day. All collected milk samples were analyzed for milk composition by FTIR spectroscopy at the Lactanet laboratory (Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, QC, Canada) using the same CombiFoss FT + analyzer (FOSS, Hillerød, Denmark). The concentrations of fat, protein (i.e., crude protein), lactose, urea nitrogen, and BHB, the fat-to-protein ratio, and somatic cell count (SCC; log transformed) were determined (data not shown).

The milk component concentration data were analyzed to determine whether they differed among housing configurations within each trial. For the TCL trial, the treatment short-term effect was tested on milk components’ concentrations averages per cow that were calculated from samples collected in weeks 1,2 and 3. The treatment long-term effect was tested on milk components’ concentrations averages per cow that included samples collected in weeks 8, 9 and 10. For the SW and MW/SL trials, the treatment short-term and long-term effects were tested on samples that were collected from week 1 and from week 6, respectively. Data analysis was done in R (version 4.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the add-on package lmerTest9. Marginal means were estimated for treatment groups using the add-on package emmeans10.

Spectral analysis

Milk FTIR spectra, outliers check and spectral pre-treatments

For each milk sample, a full FTIR spectrum was collected, which contained 1060 spectral variables (i.e., wavenumbers) between 5008 and 925 cm− 1. Principal component analysis (PCA) in JMP Pro 13.2.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was applied to the collected spectra to detect outliers and none were observed in the PCA scores plot (PC1 vs. PC2). Only spectral regions containing information related to milk composition were retained for spectral analysis, namely, 1612 –925 cm− 1, 1797 –1681 cm− 1, and 3061 –2803 cm− 111,12,13. The total number of spectral variables that were retained for analysis was 278 wavenumbers. First derivative with a derivative window of 1 and vector normalization14 were applied, separately or combined, as pre-treatments to milk spectra using codes written in MATLAB R2018a (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). As a result, four sets of milk FTIR spectra were obtained for each trial: raw, vector normalized raw (VN raw), first derivative (FD), and vector normalized first derivative (VN-FD). For the TCL trial, short-term treatment application average spectra were calculated for each cow from spectra of samples collected in weeks 1,2 and 3. Long-term treatment application average spectra were calculated for each cow from spectra of samples collected in weeks 8,9,10. These averages were calculated for the raw, VN-raw, FD and VN-FD spectral data sets. For the SW and MW/SL trials, spectra of weeks 1 and 6 were used as short-term and long-term treatment application spectra, respectively, for data analysis.

Hybrid spectral analysis approach

The effect of housing configuration treatments on milk FTIR spectra was evaluated by combining multivariate analysis with mixed modeling detailed in a previous publication8, 2021). In short, principal components (PC) were calculated by applying PCA in JMP Pro 13.2.1 to the four versions (i.e., raw, FD, VN-raw, VN-FD) of the short-term and long-term treatment application spectra or spectral averages. Only PC with eigenvalue equal to or greater than 1 and that explained at least 1% of the variance in the respective spectral dataset were retained for further analysis. This step retained informative PC and discarded noisy ones. Scores of the retained PC were used as an input15 to test for the treatment effect by PROC MIXED procedure in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) (see model description below). If a significant treatment effect is revealed at P ≤ 0.05, then the least-squares means of its scores were examined to determine the treatment levels that were significantly different from the other levels using a Scheffé adjustment. If PC was calculated from raw spectral dataset, then the influential spectral features could be directly interpreted from the PC’s loading spectrum. If a PC was obtained from the first derivative (FD) spectral datasets, we calculated the spectral integral of the PC’s loading spectrum before interpreting the influential spectral features. This step was necessary because applying a first derivative shifts the position of spectral maxima and minima, making it difficult to directly identify the original spectral band centers driving variability captured by a specific PC. By integrating the loading spectrum using the cumulative trapezoidal method in MATLAB R2018a (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA), we were able to restore a clearer representation of the original spectral features in the loading spectrum. This approach was previously tested using milk samples spiked with known compounds, and it provided a better estimation of the infrared band centers contributing to variation captured by a specific PC. A peak-fitting procedure in the Peak Resolve feature in OMNIC™ 7.3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was applied to regions in the integrated loading spectrum where no clear peaks were present. The Voigt function16 with low or high sensitivity was used, and the baseline correction was set to none. The noise and the full width at half height of the narrowest peak in the region of interest were determined by the software. The fitting process was repeated several times until an acceptable residual spectrum was obtained (i.e., nearly flat, indicating minimal unexplained variance). Although no standard deviation was calculated, this procedure was tested on spiked milk samples with known spectral features and consistently produced peak center estimates in agreement with expected values, supporting the robustness of the approach for identifying spectral band locations.

Statistical analysis

PC scores calculated from milk spectra were analyzed separately to test for the treatment effect in each trial using the models outlined below using the PROC MIXED procedure in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

For the TCL trial.

\({Y_{ijk}}=\mu +tr{t_i}+ro{w_j}+bloc{k_k}+{e_{ijk}}\)

where \(\:{Y}_{ijk}\) is the dependent variable, the PC scores isolated from spectra of milk samples from the \(\:{k}^{th}\) block (parity and lactation stage) in the \(\:{j}^{th}\) row on the \(\:{i}^{th}\) chain length, \(\:{trt}_{i}\) was the fixed effect of the \(\:{i}^{th}\) TCL treatment, \(\:{block}_{k}\) was the fixed effect of the \(\:{k}^{th}\) parity and lactation stage combination, \(\:{row}_{j}\) was the random effect of the \(\:{j}^{th}\) row in the barn and \(\:{e}_{ijk}\) was the random residual error.

For the SW trial.

\({Y_{ijk}}=\mu +tr{t_i}+ro{w_j}+bloc{k_k}+{e_{ijk}}\)

where \(\:{Y}_{ijk}\) is the dependent variable, the PC scores isolated from spectra of milk samples from the \(\:{k}^{th}\) block (parity and lactation stage) in the \(\:{j}^{th}\) row on the \(\:{i}^{th}\) stall width, \(\:{trt}_{i}\) was the fixed effect of the \(\:{i}^{th}\) SW treatment, \(\:{block}_{k}\) was the fixed effect of the \(\:{k}^{th}\) parity and lactation stage combination, \(\:{row}_{j}\) was the random effect of the \(\:{j}^{th}\) row in the barn and \(\:{e}_{ijk}\) was the random residual error.

For the MW/SL trial.

where \(\:{Y}_{ijkmnq}\) is the dependent variable, the PC scores isolated from spectra of milk samples from the \(\:{m}^{th}\) cow of the \(\:{k}^{th}\) block in the \(\:{j}^{th}\) sequence of the \(\:{i}^{th}\) length, the \(\:{q}^{th}\) treatment of the \(\:{i}^{th}\) length, and the \(\:{n}^{th}\) period, \(\:{length}_{i}\) was the fixed effect of the \(\:{i}^{th}\) stall bed length, \(\:{seq}_{ij}\) was the fixed effect of the \(\:{j}^{th}\) sequence on the \(\:{i}^{th}\) stall bed length, \(\:{block}_{k}\) was the fixed effect of the \(\:{k}^{th}\) parity and stage of lactation combination, \(\:{cow}_{ijkm}\) was the random effect of the cow from the \(\:{k}^{th}\) block on the \(\:{j}^{th}\) sequence of the \(\:{i}^{th}\) stall bed length, \(\:{period}_{n}\) was the fixed effect of the \(\:{n}^{th}\) period, \(\:{trt}_{iq}\) was the fixed effect of the \(\:{q}^{th}\) manger wall height treatment on the \(\:{i}^{th}\) stall bed length treatment and \(\:{e}_{ijkmnq}\) was the random residual error. The significance level was defined at P ≤ 0.05 for all trials.

Results and discussion

A first analysis of milk component concentrations predicted through FTIR spectroscopic analysis of milk samples did not reveal any significant difference between housing configurations within each trial (data not shown). These findings suggest that analysis of major milk components (i.e., fat, protein, and lactose) individually may not be sufficient to reflect an impact of cow comfort and ease of movement on milk composition through changing housing configurations.

In contrast, when a more comprehensive analysis of the spectra was conducted by employing PCA, significant housing treatment effects for the TCL (P = 0.032) and SW (P = 0.042) trials were revealed in PC6 and 5, respectively (Table 2). For the TCL trial, PC6 was extracted from the VN-FD long-term treatment application spectral averages datasets, and it described 1.70% of the variation. This PC did not reveal significant effects for the other studied factors that were included in the statistical model. This observation suggests that the TCL might have influenced milk composition during the trial. For the SW trial, PC5 was extracted from the VN-raw long-term treatment application spectral dataset, and it described 1.13% of the variation in that dataset. In addition to the treatment effect, this PC revealed a strong block effect (P < 0.001); for this reason, the interpretation of the loading spectrum for this PC will take into consideration all factors accounted for by blocking, which were cow parity (i.e., number of lactations) and days in milk in the current lactation (DIM). It is important to note that, due to the exclusion of one cow’s sample, a slight imbalance in parity across treatment groups may have influenced this PC, a possibility further discussed in the relevant section. For the MW/SL trial, the manger wall height treatment and its combined effect with the stall length did not reveal any significant treatment effect, which means that the manger wall treatment did not affect milk composition during the trial. However, PC6 extracted from the long-term treatment application FD spectral dataset revealed significant length effect (P = 0.036), which means that the stall length might have had a significant effect on milk composition during the trial. This PC described 1.77% of the variation in its respective dataset. In the following sections, we will refer to the short and long stalls as L1 and L2, respectively, to distinguish them from the two treatments (i.e., T1 and T2), which represent the combined effect of the stall length and manger wall height.

Table 3 summarizes the differences in the least-squares means produced by the PROC MIXED procedure for the scores of PC6, 5 and 6, which revealed a significant treatment effect in the respective trial. For the TCL, SW and MW/SL trials, there were significant differences in milk samples’ scores for T1 vs. T2 (P = 0.032), T1 vs. T2 (P = 0.042) and L1 vs. L2 (P = 0.036), respectively.

Interpretation of loading spectra of principal components that revealed significant housing configuration treatment effect on milk composition

Trial 1: chain length configuration

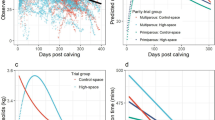

Inspection of the integral of the PC6 loading spectrum (Fig. 1) revealed peaks at the following wavenumbers: 2919, 2851, 1715, 1576, 1541, 1461, 1419 and 968 cm− 1. These peaks were identified based on standard IR band assignments reported in spectroscopy reference literature17 and validated through controlled tests in which milk was spiked with known compounds. In regions where visual identification of distinct peaks was challenging (e.g., overlapping features in region 2), the peak-fitting procedure was applied, as described in the Materials and methods section. The peaks at 2919, 2851, 1715, 1541, 1419 and 968 cm− 1 could be associated with the following molecular vibrations: the asymmetrical stretching vibration (\(\:{\nu\:}_{as}{CH}_{2}\)) of methylene groups in fatty acids17, the symmetrical stretching vibration (\(\:{\nu\:}_{s}{CH}_{2}\)) of methylene groups in fatty acids17 and histamine18, the \(\:C=O\) stretching vibration of the carboxyl functional group in free fatty acids17, the deformation vibration \(\:\left(\delta\:{NH}_{2}\right)\) of the amidine functional group in creatine19, the symmetrical \(\:C-O\) stretching vibration of the carboxylate ion in acetate, and the \(\:C-H\) bending vibration of the trans double bond in trans fatty acids17, respectively. The peak at 1576 cm−1 could be associated to: the ring stretching vibration of the imidazole ring in histamine18, the \(\:N-H\) bending vibration (\(\:\delta\:NH\)) of hippuric acid20 or the symmetrical \(\:C-O\) stretching vibration of the carboxylate ion in citrate and deprotonated fatty acids17. The peak at 1461 cm− 1 could be associated to: the \(\:C-N\) stretching vibration of urea17, the \(\:N-H\) bending vibration of the \(\:{NH}_{4}^{+}\) ion or the \(\:{NH}_{3}^{+}\) symmetrical bending vibration \(\:\left({\delta\:}_{s}{NH}_{3}^{+}\right)\) of histamine18. In addition, negative loadings were observed at 1748 cm− 1, which can be assigned to the \(\:C=O\) stretching vibration of the ester linkages in milk fat17.

The spectral integral of principal component 6 loading spectrum extracted from long-term treatment application vector normalized first derivative spectral average dataset for the tie chain length trial. Shaded regions can be assigned to: (1) trans fatty acids 968 cm−1, (2) citrate, hippuric acid and acetate 1365 –1160 cm−1, (3) acetate 1419 cm−1, fatty acids and NPN (i.e., urea, ammonium and histamine)1461 cm−1, (4) creatine 1541 cm−1, histamine, hippuric acid, citrate and fatty acids 1576 cm−1, (5) Carboxylic group of free fatty acids ~ 1715 cm−1, (6) C = O stretching vibration of ester linkages of triglycerides ~ 1748 cm−1, (7) CH stretching of fatty acids 3000 –2800 cm−1.

The peak fitting process for the region 1365 –1160 cm− 1 revealed peaks at 1347, 1299 and 1249 cm− 1, which may correspond to the \(\:{CH}_{3}\) deformation vibration21, which appears in the FTIR spectrum of an aqueous solution of acetate, the bending vibration (\(\:\delta\:{CH}_{2}\)) of the methylene group in hippuric acid20 and the \(\:C-O\) stretching vibration in citrate17, respectively. These assignments are consistent with the results of the spiking experiments reported elsewhere8.

The result of the spectral analysis suggests that the average FTIR spectra of milk samples collected from cows enrolled in both TCL treatments had significant differences in the last 3 weeks of the trial (i.e., long-term effect of chain length configuration treatment application). The loading spectrum of the principal component that revealed the significant treatment effect showed positive loadings for spectral features that might be assigned to trans fatty acids, acetate, citrate, and non-protein nitrogen (NPN) compounds, including histamine. The similar directionality of these spectral loadings (i.e., all positive) suggests that the associated spectral features may reflect molecular components that co-vary in response to the TCL treatment — increasing or decreasing together across the dataset. Accounting for 35–48% of milk NPN22, milk urea averages as determined by the FTIR milk analyzer were 12.28 mg/dL and 12.14 mg/dL for T1 and T2, respectively, during the last 3 weeks of the trial. While these values are numerically close and not intended to imply a statistically significant difference, they are used here to suggest a trend. Given that spectral features related to urea and other minor milk components (e.g., other milk NPN and trans fatty acids) showed loadings in the same direction, it is plausible that these components followed similar trends in response to the treatment. This interpretation illustrates how spectral analysis may provide insight into molecular-level changes that might not be captured by traditional prediction models. Increased trans fatty acids and NPN in milk, and histamine specifically, have previously been reported as markers of decreased pH in the rumen23,24,25. In addition, negative loadings were observed at a spectral feature that may correspond to milk fat, which suggests a possible inverse relationship between milk fat and the aforementioned minor milk components. Decreased milk fat24, decreased milk protein and increased milk NPN23 were reported in cases of reduced ruminal pH. In our study, we observed small numerical decreases in average milk protein and fat concentrations for cows in T1 compared to T2 during the last 3 weeks of the trial. The average protein content was 3.28% for T1 and 3.34% for T2, while the average fat content was 3.86% and 3.90% for T1 and T2, respectively. While these differences are not statistically significant, they are consistent with the trends suggested by the spectral analysis and previously reported physiological responses to reduced rumen pH. The observed trend in multiple milk components (e.g., milk NPN, trans fatty acids, fat, and protein) during this trial is consistent with patterns reported in the literature in cases of altered ruminal pH. These results suggest that cows housed with longer chains (T2) may have experienced more stable ruminal pH — although this was not directly measured in our study — during the last three weeks of the trial.

Trial 2: stall width configuration

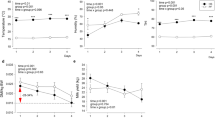

Inspection of the PC5 loading spectrum (Fig. 2) revealed positive loadings at 1721 cm− 1 and in the region ~ 1250 –1140 cm− 1 centered at ~ 1205 cm− 1. Positive loadings were also observed around 2920 and 2855 cm− 1 and within the region ~ 1565 –1520 cm− 1. Milk fat is predominantly composed of triglycerides, which are tri-esters derived from glycerol and three fatty acids, and the bands at 2920, 2855 and 1721 cm− 1 can be assigned to the asymmetrical stretching vibration (\(\:{\nu\:}_{as}{CH}_{2}\)) of the methylene groups in fatty acids of milk fat17, the symmetrical stretching vibration (\(\:{\nu\:}_{s}{CH}_{2}\)) of the methylene groups in fatty acids of milk fat17 and the \(\:C=O\) stretching vibration of the ester linkages in milk fat17, respectively. The methylene twisting and wagging vibrations of fatty acids and esters occur in the region between ~ 1250 and ~ 1140 cm−117, and the \(\:C-O\) stretching vibration of esters shows strong absorption in the 1210 –1163 cm− 1 region17. In addition, bands in the spectral region between 1565 cm− 1 and 1520 cm− 1 can be assigned to the Amide II band of milk proteins26.

PC5 scores of milk samples collected during the last week of the trial (i.e., week 6, long-term effect of stall width configuration treatment application), differed mainly in spectral features related to fat and protein. This trend is in line with the numerical values reported by the FTIR milk analyzer, where average fat concentrations were 3.96% and 3.76%, and average protein concentrations were 3.34% and 3.28%, for T1 and T2, respectively. While these differences are not statistically significant, they are consistent with the variation observed in the spectral data and may suggest that cows in T1 produced slightly more milk fat and protein during that period.

Principal component 5 loading spectrum extracted from long-term treatment application vector normalized raw spectral dataset for the stall width trial. Shaded regions can be assigned as follows: (1) 1250 –1140 cm−1 to the methylene twisting and wagging vibrations of fatty acids, esters and BHB, and to the C-O stretching vibration of esters, (2) 1565 –1520 cm−1 to the Amide II band of milk proteins, (3) 1721 cm−1 to the C = O stretching vibration of ester linkages in milk fat, (4) 3000 –2840 cm−1 to the asymmetrical stretching (ν_as [CH]_2) and the symmetrical stretching (ν_s [CH]_2) of the methylene group in fatty acids of milk fat.

Trial 3: manger wall and stall length configuration

Inspection of the spectral integral of the PC6 loading spectrum (Fig. 3) revealed positive loadings at the following wavenumbers: 1575, 1460, 1408, 1033, 980 and 946 cm− 1. The peak at ~ 1575 cm− 1 is observed in the FTIR spectrum of histamine in aqueous solution8 and could be associated with the stretching vibration of the imidazole ring18. The peak at ~ 1460 cm− 1 is observed in the FTIR spectra of milk samples spiked with urea and ammonium chloride8; hence, it may correspond to the \(\:C-N\) stretching vibration in urea17 or to the \(\:N-H\) bending vibration in the ammonium ion17. The peak at ~ 1408 cm− 1 is observed in milk samples spiked with BHB8 and may correspond to the \(\:C-O-H\) bending vibration or the symmetrical \(\:C-O\) stretching vibration of the carboxylate ion17. The peaks at ~ 1033 and 980 cm− 1 are observed in the FTIR spectra of milk samples spiked with histamine8. The peak at ~ 946 cm− 1 is observed in FTIR spectra of aqueous solutions of histamine and BHB8; all of which may be indicative of functional groups present in these compounds, though spectral overlaps in milk must be considered.

Principal component 6 loading spectrum extracted from long-term treatment application first derivative spectral dataset for the stall length and manger wall trial. Shaded regions can be assigned as follows: 1–3) peaks at ~ 1033, 980 and 946 cm−1 are found in FTIR spectra of milk samples spiked with histamine and BHB and their aqueous solutions, 4) peak at ~ 1408 cm−1 is observed in FTIR spectra of milk samples spiked with BHB, 5) peak at ~ 1460 cm−1 is observed in FTIR spectra of milk samples spiked with urea and ammonium, 6) peak at ~ 1575 cm−1 is observed in FTIR spectrum of histamine in aqueous solution.

The spectral analysis suggested that the stall length might have had an effect on BHB, urea and other milk NPN including histamine during the last week of the trial (i.e., long-term effect of manger wall and stall length configuration treatment application). During week 6, the averages of milk urea concentrations for period 1 were 13.02 mg/dL and 11.79 mg/dL for L1 and L2, respectively, and 14.01 mg/dL and 12.43 mg/dL for L1 and L2, respectively, for period 2. While these differences are small and not statistically significant, they are consistent with the directionality of spectral features related to urea in the corresponding PC loading spectra. These observations may support the association between the identified spectral patterns and changes in urea content across treatments. Since spectral features that can be assigned to histamine are showing positive loadings, similar to features related to urea, we could assume that milk samples collected from cows assigned to L1 had higher levels of histamine too.

Comparison between behavioural data and spectral analysis results

Trial 1: chain length configuration

The analysis of the animal behavior and other animal-based outcome measures revealed that increasing the chain length improved the cows’ ease of movement and transitions3. Results indicate that the time spent outside of the stall by the withers of the cows (i.e., the ridge between the shoulder blades of an animal) assigned to the longer chain treatment (T2) was significantly greater in comparison to cows assigned to the recommended length (T1) (11 ± 1.1 vs. 7 ± 1.1% of daily time; P = 0.05)3, and it significantly increased across the trial (+ 3% of daily time; P ≤ 0.05)3. This measurement indicates that cows assigned to longer chains were spending more time outside the stall perimeter in the manger area. In addition, the distance outside of the stall perimeter for the withers, which represents the average distance outside of the stall in the manger area, increased significantly from the beginning and the end of the trial (+ 0.9 cm; P ≤ 0.05) for both treatments3; however, this measurement did not differ between treatments. From these results, we can conclude that cows assigned to the longer chain treatment (T2) were spending more time in the manger and were capable of stretching further in the manger area during the last three weeks of the trial. One possible behaviour of dairy cows at the manager is feeding; however, the combined “eating/rumination time” measurement did not reveal significant differences between the two treatments27 and the device that was used for this measurement was not capable of reliably differentiate the two behaviours separately and therefore were combined28. Another possible behaviour for dairy cows at the manager is feed sorting. Cows tend to sort their ration initially in favour of the smaller particles and against longer forage particles29,30. This behaviour results in greater intake of highly-fermentable carbohydrates and lesser intake of effective fiber than intended and is associated with reduced rumen pH and altered milk composition. However, when dairy cows are given the opportunity through management and feeding environment that affect time available to manipulate feed, dairy cows could possibly adjust their sorting pattern in favor of physically effective fiber to attenuate low rumen pH. Feed sorting behaviour also affects milk composition30. Milk fat can increase by 0.1% points for every 10% selection in favor of long ration particles and milk protein can decrease by 0.05% for every 10% refusal of long ration particles30. During the last three weeks of the trial, milk samples from cows with longer chains (T2) showed slightly higher average fat and protein concentrations — by 0.04% and 0.06%, respectively — though these differences were not statistically significant. According to these results, we can hypothesize that cows with longer chains (T2) were given the opportunity to manipulate feed for longer time, since they spent more time in the manger, and they were at ease to access the manger a bit further, which gave them the chance to sort for effective fiber when ruminal pH was low. This hypothesis is inline with the trend that was revealed by the spectral analysis in which we observed changes of spectral features that are assigned to milk NPN, trans fatty acids and milk fat, which were consistent with changes that have been reported in the literature in cases of changing ruminal pH23,24,25. However, it must be mentioned that feed sorting behaviour and ruminal pH were not measured in this trial; therefore, this interpretation should be viewed as exploratory and requiring confirmation in future work.

Trial 2: stall width configuration

The spectral analysis suggested that cows assigned to the single stall width (T1) were synthesizing more milk fat and proteins during the last week of the trial. PC5, the principal component that revealed a significant treatment effect (P = 0.042), also revealed a strong block effect (P < 0.001). This observation suggests that the treatment effect might have been confounded by factors accounted for by blocking. In addition to nutrition and herd management practices, several factors affect milk composition. These factors are region, season, breed, individuality, age, disease, diurnal rhythm, stage of lactation and parity31. The trial was conducted on the same premises during one season, all cows were of the same breed (Holstein), and milk samples combined portions from morning and evening milkings to eliminate the variations in milk composition related to diurnal rhythm. Blocking was implemented in the experimental design of the trial to account for variations related to the remaining factors, which are stage of lactation and parity. However, a cow’s milk sample from block 8 in the double width treatment (T2) was missing in week 6 of the trial. This cow was the only primiparous animal in T2. In addition, T2 had a cow in its seventh parity while the greatest parity in T1 was the fifth. Owing to the missing milk sample, the median parity of the cows assigned to T2 became greater than that of the cows assigned to T1, namely, 3 and 2, respectively. Hence, cows of T2 were older and one lactation higher than those of T1. Milk fat and protein decline as the animal becomes older32. Milk fat falls about 0.2% each year from the first to fifth lactation because of higher production and more udder infections, while protein decreases 0.02 to 0.05% each lactation as animals age32. This observation might explain the strong block effect (P < 0.001) and the treatment effect (P = 0.042) on PC5. In this case, the treatment effect might have originated from the imbalance of cow age (parity) in blocks of T1 and T2 that resulted from the exclusion of cow 2057 owing to the missing milk sample in week 6. The effect of a greater age (parity) in T2 might have overshadowed possible effect on milk composition related to the stall width treatment. When the spectral analysis was applied to the spectral datasets of week 5, none of the extracted PC revealed a significant treatment effect. In this trial, the spectral analysis possibly detected effects of multiple factors on the FTIR spectra of milk samples. The results of the spectral analysis were consistent with specific experimental details of the trial, which limits our capacity to corroborate improved comfort status shown by the behavioral data (i.e., larger width equals better resting postures6.

Trial 3: manger wall – stall length configuration

Histamine was the most interesting candidate among the molecular species that could have accounted for features with positive loadings in the loading spectrum of the PC that revealed a significant stall length effect. Histamine in milk originates from the blood serum22, and elevated concentrations of histamine can be attributed to the corium tissue breakdown (i.e., resulting in skin lesions or injuries) or stress23. The results of the trial show that injury severity decreased at several different locations on the cows over time, regardless of treatment. It has been found that cows had 4–8 times fewer contacts with the tie-rail while they were rising in long stalls (L2) regardless of the manger height but only in comparison to short stalls with low manger, which may have led to possible reduction of injuries on the cow’s neck7. However, reduction in injuries on the cow’s neck was greater for cows in short stalls with high manger as compared to low manger. The key finding on the outcome measures of comfort comparing long stalls to short stalls is the increase of 1 h per day in lying time7. Increased lying time of 1 h per day for cows assigned to longer stalls (L2) indicates a more comfortable environment (i.e., less contact with stall elements) and thus may explain the reduced histamine concentrations23. It must be noted that no physiological indicator related to stress was measured in this trial.

Another source of elevated histamine in the blood is protein degradation that is associated with necrotic diseases such as mastitis and metritis23. In week 6 of the trial, the averages of SCC for short stall (L1) and long stall (L2), regardless of the manger wall height, were 281,435 and 133,136 cells/mL (data not shown), respectively. If these numbers are broken down by period, the averages of SCC for L1 and L2 for week 6 become 528,273 cells/mL and 203,700 cells/mL, respectively, for period 2. In Canadian Holstein cows, SCC greater than 200,000 cells/mL is considered a sign of mastitis for cows that are more than 30 DIM33. This observation suggests that cows assigned to shorter stalls might have been releasing more histamine into their blood than those assigned to longer stalls due to udder inflammation. It must be noted that all cows enrolled in the trial were screened to ensure healthy udder status at baseline; cows with abnormally high SCC or clinical mastitis were excluded. However, no solid conclusion can be made regarding the relationship between the stall length, milk composition and susceptibility to mastitis in this trial. In fact, due to a strict maintenance of stall and bedding, no differences in stall cleanliness or dryness or in udder health were found between treatments and over time7. While the literature reports a few epidemiological studies that find that longer stalls increase udder dirtiness34,35, the link between stall length, stall cleanliness and udder cleanliness is not clearly demonstrated36,37,38,39. The dynamics of infectious microorganisms’ proliferation on dairy farms is complex and the stall length and manger wall trial was not designed to consider factors that have significant effect on the proliferation of mastitis, such as management stall cleaning practices34.

Conclusion

In this paper, we studied changes in milk composition that can be attributed to modifications in the housing environment by altering specific elements in the tie-stall. None of the proposed modifications to the chain length, stall width, stall length and manger wall height were designed to stress the cows or inflect pain on them. On the contrary, all these modifications were proposed to increase cows’ comfort and ease of movement in their stalls. When major and minor milk components were considered individually, they did not reveal consistent differences between the control and modified housing configurations. However, principal component scores calculated from milk FTIR spectra, a multivariate measurement, revealed significant differences between treatments. These scores captured subtle and simultaneous changes in multiple milk components and related them to housing modifications.

The alignment between behavioral observations and spectral changes is a promising finding and suggests the potential for using milk spectral features as indirect indicators of cow comfort or behavioral state. Further studies with larger datasets and direct behavioral metrics are warranted to explore this relationship more deeply. Milk FTIR spectra contain rich information and hold promise for assessing cow comfort and welfare through routine milk samples collected in dairy herd improvement programs. However, more research is needed to strengthen this potential, for example, by including additional physiological and behavioral welfare markers (e.g., oxytocin), or by integrating milk FTIR spectroscopy with other analytical approaches such as metabolomics. Future work should also extend the focus to other dimensions of animal welfare, including affective states.

Data availability

Data can be obtained upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Von Keyserlingk, M., Rushen, J., de Passillé, A. M. & Weary, D. M. Invited review: the welfare of dairy cattle – Key concepts and the role of science. J. Dairy. Sci. 92 (9), 4101–4111 (2009).

World Organization for Animal Health. Terrestrial Animal Health Code, Vol. 1 (31st ed.). 333. World Organization for Animal Health, (2023).

Boyer, V., de Passillé, A. M., Adam, S. & Vasseur, E. Making tiestalls more comfortable: II. Increasing chain length to improve the ease of movement of dairy cows. J. Dairy. Sci. 104 (3), 3316–3326 (2021).

Shepley, E., Vasseur, E. & Graduate Student Literature Review. The effect of housing systems on movement opportunity of dairy cows and the implications on cow health and comfort. J. Dairy. Sci. 104 (6), 7315–7322 (2021).

St John, J., Rushen, J., Adam, S. & Vasseur, E. Making tiestalls more comfortable: I. Adjusting tie-rail height and forward position to improve dairy cows’ ability to rise and lie down. J. Dairy. Sci. 104 (3), 3304–3315 (2021).

Boyer, V. et al. Making tiestalls more comfortable: III. Providing additional lateral space to improve the resting capacity and comfort of dairy cows. J. Dairy. Sci. 104 (3), 3327–3338 (2021).

McPherson, S. & Vasseur, E. Making tiestalls more comfortable: IV. Increasing stall bed length and decreasing manger wall height to heal injuries and increase lying time in dairy cows housed in deep-bedded tiestalls. J. Dairy. Sci. 104 (3), 3339–3352 (2021).

Bahadi, M., Ismail, A. A. & Vasseur, E. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy as a Tool to Study Milk Composition Changes in Dairy Cows Attributed to Housing Modifications to Improve Animal Welfare. Foods 10(2), 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods.10020450 (2021).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. LmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82 (1), 1–26 (2017).

Lenth, R. V. & emmeans Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means (ed. 1.6.1). R package (2021).

Soyeurt, H. et al. Mid-infrared prediction of bovine milk fatty acids across multiple breeds, production systems, and countries. J. Dairy. Sci. 94 (4), 1657–1667 (2011).

Eskildsen, C. E. et al. Quantification of individual fatty acids in bovine milk by infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics: Understanding predictions of highly collinear reference variables. J. Dairy. Sci. 97 (12), 7940–7951 (2014).

Visentin, G., Penasa, M., Gottardo, P., Cassandro, M. & De Marchi, M. Predictive ability of mid-infrared spectroscopy for major mineral composition and coagulation traits of bovine milk by using the uninformative variable selection algorithm. J. Dairy. Sci. 99 (10), 8137–8145 (2016).

Esbensen, K. et al. Multivariate Data Analysis: An Introduction to Multivariate Analysis, Process Analytical Technology and Quality by Design (6th edition). CAMO, Oslo, Norway (2018).

Lehman, A., O’Rourke, N., Hatcher, L. & Stepanski, E. JMP for Basic Univariate and Multivariate Statistics: Methods for Researchers and Social Scientists (2nd edition). 471–511Sas Institute, (2013).

Bradley, M. Curve fitting in Raman and IR spectroscopy: basic theory of line shapes and applications (Thermo fisher scientific. Application Note 50733). (2007). https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/CAD/Application-Notes/AN50733_E.pdf.

Silverstein, R. M., Webster, F. X. & Kiemle, D. J. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds (8th edition). 78–107 (John Wiley & Sons, (2015).

Collado, J. A. & Ramírez, F. J. Infrared and Raman spectra of histamine-Nh4 and histamine‐Nd4 monohydrochlorides. J. Raman Spectrosc. 30 (5), 391–397 (1999).

Socrates, G. Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies: Tables and Charts (Wiley, 2004).

Karabacak, M., Cinar, M. & Kurt, M. Molecular structure and vibrational assignments of Hippuric acid: A detailed density functional theoretical study. Spectrochim Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 74 (5), 1197–1203 (2009).

Ito, K. & Bernstein, H. J. The vibrational spectra of the formate, acetate, and oxalate ions. Can. JChem. 34 (2), 170–178 (1956).

Alston-Mills, B. Nitrogenous components of milk: G. Nonprotein nitrogen compounds in Bovine Milk in Handbook of Milk Composition (ed Jensen, R. G.) 468–472. (Academic, (1995).

Nocek, J. E. Bovine acidosis: implications on laminitis. J. Dairy. Sci. 80 (5), 1005–1028 (1997).

Abdela, N. Sub-acute ruminal acidosis (SARA) and its consequence in dairy cattle: A review of past and recent research at global prospective. Achiev. Life Sci. 10 (2), 187–196 (2016).

Humer, E. et al. Invited review: practical feeding management recommendations to mitigate the risk of subacute ruminal acidosis in dairy cattle. J. Dairy. Sci. 101 (2), 872–888 (2018).

van de Voort, F. R. Ismai. A. A. Proximate analysis of foods by mid-FTIR spectroscopy. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2, 13–17 (1991).

Boyer, V., de Passillé, A. M., Adam, S. & Vasseur, E. Making tiestalls more comfortable: II. Increasing chain length to improve the ease of movement of dairy cows. J Dairy. Sci 104(3), Supplemental Table S1, https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/articles/p5547x13z?locale=en.

Zambelis, A., Wolfe, T. & Vasseur, E. Validation of an ear-tag accelerometer to identify feeding and activity behaviors of tiestall-housed dairy cattle. J. Dairy. Sci. 102 (5), 4536–4540 (2019).

DeVries, T., Dohme, F. & Beauchemin, K. Repeated ruminal acidosis challenges in lactating dairy cows at high and low risk for developing acidosis: feed sorting. J. Dairy. Sci. 91 (10), 3958–3967 (2008).

Miller-Cushon, E. & DeVries, T. Feed sorting in dairy cattle: Causes, consequences, and management. J. Dairy. Sci. 100 (5), 4172–4183 (2017).

Jensen, R. G. Miscellaneous Factors Affecting Composition and Volume of Human and Bovine Milks. In Handbook of Milk Composition 237–271 (Academic, 1995).

Heinrichs, J., Jones, C. & Bailey, K. Milk components: Understanding the causes and importance of milk fat and protein variation in your dairy herd. Dairy. Anim. Sci. 5, 1e–8e (1997).

Arnould, V. M. R., Reding, R., Bormann, J., Gengler, N. & Soyeurt, H. Review: milk composition as management tool of sustainability. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 17 (4), 613–621 (2013).

Plesch, G. & Knierim U.Effects of housing and management conditions on teat cleanliness of dairy cows in cubicle systems taking into account body dimensions of the cows. Animal 6 (8), 1360–1368 (2012).

Bouffard, V. et al. Effect of following recommendations for tiestall configuration on neck and leg lesions, lameness, cleanliness, and lying time in dairy cows. J. Dairy. Sci. 100 (4), 2935–2943 (2017).

Veissier, I., Capdeville, J. & Delval, E. Cubicle housing systems for cattle: comfort of dairy cows depends on cubicle adjustment. J. Anim. Sci. 82 (11), 3321–3337 (2004).

Martiskainen, P., Koistinen, T. & Mononen, J. Cubicle dimensions affect resting-related behaviour, injuries and dirtiness of loose-housed dairy cows. in Proceedings of the XIII (13th) International Congress in Animal Hygiene (ed. Aland, A.). 175International Society for Animal Hygiene, (2007).

Lombard, J. E., Tucker, C. B., von Keyserlingk, M. A. G., Kopral, C. A. & Weary, D. M. Associations between cow hygiene, Hock injuries, and free stall usage on US dairy farms. J. Dairy. Sci. 93 (10), 4668–4676 (2010).

McPherson, S., Vasseur, E. & Graduate Student Literature Review. The effects of bedding, stall length, and manger wall height on common outcome measures of dairy cow welfare in stall-based housing systems. J. Dairy. Sci. 103 (11), 10940–10950 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the funding support provided by NSERC, Novalait, Dairy Farmers of Canada, and Valacta (now Lactanet) as a part of the NSERC Industrial Research Chair in the Sustainable Life of Dairy Cattle. The authors would also like to acknowledge thefunding contribution of FRQNT, CRIBIQ and Novalait- (project No 2017-LG-202046) as part of the Programme de recherche en partenariat pour l'innovation en production et en transformation laitières - VII 2e concours, as well as Valacta (now Lactanet) for providing the milk component and infrareddata used in this study. We thank and acknowledge Dr. Jacqueline Sedman (McGill University) for reviewing the manuscript, Tania Wolfe (McGill University) for providing guidance on the statistical models used in this study, and former graduate students Véronique Boyer and Sarah McPherson (McGill University) for providing understanding in their animal trial designs and results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MB has contributed to the design of the work, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, and to the writing and revision of the written draft. DW, AAI and EV have contributed to the design of the work, the analysis and interpretation of the data, and to the writing and revision of the written draft. DES, DML and RD have contributed to the design of the work, the analysis and interpretation of the data, and to the writing and revision of the written draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bahadi, M., Warner, D., Ismail, A.A. et al. Evaluating the impact of housing modifications on milk infrared spectra as indicators of dairy cow welfare status. Sci Rep 15, 45791 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28557-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28557-7