Abstract

The coloration of garnets is governed by transition metal ions and crystal structure. This study established a rapid variety identification method for orange-red garnets based shifts in infrared absorption peaks. We quantified color parameters under standardized illuminants (D65, A, and F2) using the CIE 1976 L*a*b* space. The results revealed that the Mn/Fe ratio and Fe content critically modulate the hue angle (h°) of orange and red garnets. Illuminant A maximises chroma for red varieties, while F2 light optimally displays orange-yellow garnets. D65 provides a versatile source for routine identification and evaluation. This integration of crystal chemistry and colorimetry offers actionable strategies for optimising orange-red gemstone presentation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Garnets have been prized since ancient times due to their unique colors. Excavated garnet bead ornaments serve as key evidence of ancient East–West trade, technological diffusion, and cultural exchanges during the "Maritime Silk Road" period. Today, garnets are valued for their abundant reserves and balanced aesthetic/economic appeal, symbolizing marital tolerance and understanding as the 18th wedding anniversary gemstone. Garnet is a member of the cubical system and the chemical formula is A3B2(SiO4)3, the A site can be occupied by divalent cations such as Ca2+, Mg2+, Fe2+, and Mn2+, while the B site is typically occupied by trivalent cations including Al3+, Fe3+, and Cr3+. Due to the frequent occurrence of continuous isomorphic substitution, garnets rarely exist as pure end-member components. Complex chemical compositions of Aluminous garnets give rise to diverse hues, forming a striking purple-red–orange gradient series1.

Garnets exhibit a rich color palette due to their composition of transition elements (Cr3+, Mn2+, Fe3+)2. Based on the crystal structure of garnets, the origin of their color formation is attributed to crystal field theory. In garnets, selective absorption of visible light occurs because d-electrons of transition metals (in the crystal structure) are excited by incident photons of matching energy. This excitation prompts the electrons to transition from ground states to higher-energy orbitals3. The resultant combination of reflected and transmitted light wavelengths generates the distinct color of the gemstone4. In pyrope and almandine, Mg2+ is insignificant for coloration and the special purple-red color is caused by Fe2+ and Mn2+. When the combined content of Fe2+ and Fe3+ exceeds that of Mg2+ in A-sites, crystal field parameters shift and pyrope gradually transitions to almandine5. In spessartine, the primary chromophore is Mn2+. Mn2+ in dodecahedral sites undergoes spin-forbidden d-d transitions, which produce broad blue-green absorption and generate orange tones. The presence of Fe2+ further influences the intensity and hue of this orange color6,7.

Garnets show extensive isomorphous substitution, making species differentiation by color impossible. Though distinct garnet species differ in refractive index and density, these parameters have excessive overlap and errors from internal inclusions, limiting their reliability8. Researchers have used electron microprobe analysis (EPMA) to determine the composition and species of garnets, and identified that isomorphous substitution occurs between calcium-series and aluminum-series garnets. Yet, EPMA is complex and time-consuming, while other compositional methods are destructive and costly9. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy is a simple, rapid, and non-destructive technique for garnet identification10. Prior studies used cluster analysis to predict infrared peak numbers in calcium-series garnets and confirmed a correlation between cation radius and peak position, but lacked data on aluminum-series garnets. To fill this gap, this study aims to establish a rapid, non-destructive method for identifying orange-red garnet species via systematic analysis of infrared absorption peak positions.

Concurrently, customers often go to the jewelry counter to try on garnet jewelry. Given the vivid saturation of aluminum garnets’ red hues, lighting conditions exert marked effects on purchaser perception. The CIE 1976 L*a*b* uniform color space can quickly, non-destructively, and accurately quantify the color of gems. Aluminous garnets remain under-investigated in terms of lighting-dependent color perception. Therefore, in this study, by analyzing the standard light sources commonly used in the jewelry industry for illuminating and observing colored gemstones, the effects of standard illuminants D65, A, and F2 on garnet samples were examined. Using the theory of the CIE 1976 L*a*b* uniform color space, the color temperature of the illumination sources was controlled as a variable to obtain the corresponding color parameters within the CIE colorimetry system. Additionally, by summarizing feedback from experimental observers’ visual evaluations, the optimal light source for the aluminous garnet series was finally determined.

By integrating spectroscopic subspecies identification, colorimetric quantification and psychological experimentation, this research aims to achieve three interconnected objectives: 1) rapid and non-destructive identification of garnet subspecies by spectroscopic analysis (infrared spectroscopy, UV–Vis spectroscopy); 2) investigation on the influence of composition on the color of red–orange garnets under different light sources; 3) determine optimal lighting for aluminum-series garnets by identifying subspecies via quantifying color parameters and evaluating observer preferences under D65, A, and F2 illuminants. This research innovatively integrates colorimetry with color psychology, offering a robust theoretical foundation for enhancing display methodologies and commercial strategies in the garnet market.

Results and discussion

Infrared spectral characteristics

As a nesosilicate mineral, the infrared spectral characteristics of garnet are collectively governed by the vibrations of [SiO4]4− groups and cation lattice vibrations. In the high-frequency region above 500 cm−1, absorption peaks primarily originate from the internal vibrations of silicate ([SiO4]4−) groups: three absorption peaks in the 800–1100 cm−1 range arise from the triply degenerate splitting of asymmetric stretching vibrations (ν3) of [SiO4]4− groups, while three peaks in the 500–700 cm−1 interval result from the doubly degenerate symmetric bending vibrations (ν2) or triply degenerate out-of-plane bending vibrations (ν4) of [SiO4]4− groups. Considering the large sample size and diverse color profiles, all garnet specimens were classified into two color-based groups for infrared spectroscopy analysis. The first group comprises the wine-red to red pyrope-almandine series, whereas the second group encompasses the red–orange grossular and spessartine samples.

Analysis was first performed on the wine-red to red specimens (Fig. 1). Three characteristic garnet samples (M1: pyrope, T1: almandine, R1: pyrope-almandine solid solution) were selected from the red-series samples for infrared spectroscopy analysis, following comprehensive spectral testing of all specimens in the dataset. For pyrope, three characteristic peaks (A, B, C) appear at approximately 996 cm−1, 909 cm−1, and 878 cm−1, respectively, with Peak D consistently absent. Peaks E and F are located near 583 cm−1 and 531 cm−1. In the almandine group, Peaks A, B and C are centered at 988 cm−1, 908 cm−1, and 877 cm−1. A dichotomy is observed for Peak D: partial samples exhibit a distinct peak at about 638 cm−1, while others show complete absence of this feature. Peaks E and F in almandine occur at 575 cm−1 and 530 cm−1.

In red-series garnets, the ionic radii of Mg2+ and Fe2+ progressively increase, leading to corresponding expansions in the unit cell parameters of pyrope and almandine. This structural modification weakens Si–O bond strength, consequently shifting vibrational frequencies toward shorter wavelengths. Consequently, as cationic radius increases in garnets, the wavenumber positions of infrared absorption peaks show a downward trend—one especially pronounced for the A peak. The emergence of the D peak demonstrates correlation with the end-member ratio between pyrope and almandine components. Higher pyrope/almandine ratios correspond to reduced probability of D peak detection, with complete absence observed beyond a critical compositional threshold during the almandine-to-pyrope transition. Therefore, a key diagnostic criterion for distinguishing between almandine and pyrope varieties lies in the characteristic wavenumber position of the A peak observed in their infrared spectra. Additionally, the absence/presence status of the D peak can serve as supplementary discriminative indicators. This spectroscopic approach enables precise identification of garnet compositional variations within the pyrope-almandine solid solution series.

Subsequently, our study focuses on using infrared spectroscopy for the rapid non-destructive identification of different orange garnet varieties (Fig. 2). Two characteristic garnet samples (G1: grossular, S1: spessartine) were selected from the orange-series samples for infrared spectroscopy analysis, following comprehensive spectral testing of all specimens in the dataset. In the infrared spectrum range of 800–1100 cm−1, the species can be identified by the position of peak A. The A peak of grossular is around 948 cm−1, while that of spessartine is near 972 cm−1. Additionally, the average band spacing between peaks B and C in spessartine is slightly wider than that in grossular. In grossular, the large Ca2+ ion occupies the divalent cation site, increasing the distance between Si4+ and Ca2+. This expanded separation weakens the coupling effect when [SiO4]4− tetrahedra and A2+ dodecahedra share edges. A weaker coupling results in a smaller splitting distance between the two bands.

In the 500–800 cm−1 range, the vibration amplitude of peak D is strongly influenced by the divalent cation content. This is due to two main factors. First, as a calcium-group garnet, grossular contains Ca2+ with a large ionic radius, which requires high pressure for incorporation into the crystal lattice. Second, the limited miscibility between grossular and spessartine leads to negligible Mg2+ content and favors the substitution of Fe3+ into the lattice. This substitution enhances the vibrational intensity of peak D.

Comprehensive analysis was performed on a set of infrared spectral data selected from each garnet species (Fig. 3). A remarkably strong negative correlation (r = − 0.993) was observed between the position of the Si–O vibrational band and the lattice parameter a0 of garnet. As the cation radius increases, the lattice parameter of the crystal correspondingly enlarges: the a0 value of grossular is 11.851, and that of pyrope is 11.45911. This increase in lattice parameter also causes the Si–O vibration frequency to shift toward shorter wavelengths. Specifically, the shift of the Si–O stretching vibration peak is more pronounced than that of the bending vibration peak, with peak A exhibiting the most significant positional movement. Therefore, the position of peak A in the infrared spectrum enables non-destructive and rapid identification of garnet species.

Colouration mechanism

The hypothesized mechanisms of color formation can be categorized into three fundamental theories: crystal field theory, band theory and molecular orbital theory12,13,14. These theories share a common core: they postulate that electron movement leads to the selective absorption of light, thereby giving rise to different colors. Moreover, these colors are contingent upon the spatial extent of electron motion. In the garnet lattice, the [AO8] distorted cubic coordination polyhedra and [BO6] octahedra are each connected to isolated [SiO4] tetrahedra. At the A-site (eight-coordinated cubic site), Fe2+ and Mn2+ ions are surrounded by eight oxygen atoms, forming a hexagonal bipyramidal coordination field. Primarily transition metal ions (Cr3+, Mn2+, Fe3+) occupy the eight-coordinated A-sites ([AO8] distorted cubes) and six-coordinated B-sites ([BO6] octahedra). Their color-generating mechanisms are primarily attributed to d-d electron transitions within these ions. The resultant mixed spectrum of reflected and transmitted light during this process gives rise to the gemstone’s characteristic color. Due to isomorphic substitution, transition metal ions occupy both octahedral (B-site) and eight-coordinated cubic (A-site) positions in the garnet lattice. The electronic transitions from these different coordination environments overlap, resulting in complex ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) absorption spectra.

In the octahedral field, the 3d6 electrons of Fe2+ undergo a spin-allowed transition from the ground state 5T2g to the excited state 5Eg. This transition forms strong absorption peaks at 421 nm in the violet region and 523 nm in the green region. The excited state 5Eg further undergoes spin-forbidden transitions to 3E1g(3H) and 3T1g(3H) states, giving rise to weak absorption peaks at 616 nm and 687 nm in the red region. The absorption near 459 nm results from charge transfer between iron ions (Fe2+ + Fe3+ → Fe3+ + Fe2+)15. The absorption peaks of Mn2+ mainly occur near 407 nm and 480 nm, where d-d electron transitions in the outermost orbitals lead to broad absorption in the blue-violet region, and the complementary color of blue-violet absorption appears as orange16,17. In almandine garnet, the absorption area at 687 nm in the visible-region absorption spectrum is very large, which has a direct correlation with the high iron ion content in almandine. Notably, in pyrope garnet with lower iron content, the absorption area at 687 nm shows a strong correlation with color. As the color of the pyropes ranges from pale purplish-red to deep red, the absorption of the 687 nm peak becomes stronger (inset in the upper-left corner of Fig. 4).

Chroma, also known as purity or saturation, denotes the vividness and purity of a color18,19. It is typically determined by the proportion of the primary pure color in a mixed color to distinguish the level of chroma. As the height of the 687 nm peak increases, the chroma of the pyrope gemstones decreases and tends toward a purplish-red hue. Meanwhile, the FeO content increases with the greater height of the 687 nm peak. Therefore, as the FeO content increases, the absorption of the 687 nm peak intensifies, and the pyrope’s color transitions from light red to deep purplish-red. This conclusion establishes a correlation among the composition, color parameters, and UV–Vis spectroscopy of pyrope. The color and composition of pyrope can be inferred from UV–Vis spectral observations.

Relationship between content and colour under different light sources

Energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (ED-XRF) enables rapid, non-destructive identification of elements in garnets by correlating spectral wavelengths with elemental types and intensities with concentrations. Analysis of samples confirmed that manganese oxide (MnO) and iron oxide (FeO) are the primary chromophores. For orange-series garnets, spessartine contains manganese oxide in the range of 28.00–36.50 wt% and iron oxide between 0.80 and 4.00 wt%, while grossular has a lower manganese oxide content spanning 0.11–0.36 wt% and iron oxide concentrations ranging from 1.89 to 4.67 wt%. In red-series garnets (e.g., almandine and pyrope), manganese oxide content ranges from 0.26 to 1.94 wt%, and iron oxide concentrations vary from 9.98 to 28.59 wt%, showing a distinct trend where iron content exceeds manganese content.

CIE 1976 L*a*b* color space enables precise analysis of gemstone color characteristics through three key parameters20,21,22. The L* value quantifies the light–dark degree of color (0 for pure black, 100 for pure white), directly correlating with the visual brightness performance of gemstones; the a* coordinate measures the red-green spectral shift, and the b* coordinate depicts the yellow-blue tone change4,23,24. These two together form the basic tonal framework of gemstones. The higher the chroma (C*) value, the more vivid and intense the gemstone color becomes, which is decisive for gemstone value assessment. Additionally, the hue angle (h◦) presents the color gradient trend through a continuous angular sequence, further completing the full-dimensional description of gemstone colors25,26. Based on the CIE 1976 L*a*b* color space, the effects of standard illuminants D65, A, and F2 on the color of garnet samples can be explored. The spectral power distribution curve of illuminant D65 is relatively uniform in the green, yellow, and red regions. Its highest peak appears in the blue-green region at approximately 480 nm27,28. The spectral power distribution of illuminant F2 exhibits sharp peaks at multiple wavelengths, such as 440 nm and 540–580 nm, and its excessively tortuous spectral power distribution curve makes it unsuitable for illumination. The spectral power distribution of illuminant A approximates a tilted straight line, with the strongest spectral radiation in the red region. By analyzing the standard light sources commonly used in the jewelry industry for illuminating and observing colored gemstones, D65, A were mostly selected as the light sources for studying garnet samples in this work.The color temperature of the illumination source was controlled as a variable to obtain the color parameters of garnets in the CIE colorimetric system.

Correlation analysis measures the strength and direction of relationships between quantitative variables. Through ED-XRF and UV–Vis analyses, it has been found that the color of garnet is typically induced by transition metal ions. To explore the relationship between the chemical composition of garnet and its color parameters, bivariate correlation analysis was used to investigate the associations among color parameters. It is worth noting that previous studies were all conducted under a single light source. This study selects two standard light sources, D65 and A light sources, to make the research more comprehensive.

The results show that the Fe content in red-series garnets (almandine, pyrope, and their solid solutions) exhibits a negative correlation with the hue angle (Fig. 5). Higher Fe content corresponds to a smaller hue angle, causing the gemstone color to transition from brick red to purplish red, which is consistent with the conclusions discussed in the previous UV–Vis spectroscopy analysis. Further investigation reveals differences in the correlation between Fe content and the hue angle of red-series garnets under D65 and A light sources. Specifically, the correlation under the A light source (R2 = 0.91) is stronger than that under the D65 light source (R2 = 0.80). The mechanism is as follows: Illuminant A has high spectral power at 600–700 nm (red) and low power at 500–550 nm (green). Iron ions show strong d-d transition absorption in green and weak absorption in red. A standard light’s high red power compensates for iron ions’s weak red absorption, stabilizing the base color; its low green baseline power means slight iron ions increases trigger significant green absorption, causing obvious hue shifts. When A light source illuminate red-series garnet samples, it causes the samples’ colors to lean more toward the red tone. Consequently, their color performance under the A light source is closer to the effect of iron ions than that under the D65 light source.

Due to the weak red tone of orange garnet, color evaluation under illuminant A is prone to deviations. Therefore, this experiment was conducted under the D65 standard light source. In orange garnet, both manganese (Mn) and iron (Fe) are trace elements with subtle differences in content, and they jointly influence the gemstone’s color. Systematic analysis revealed a negative correlation between the Fe/Mn ratio and the hue angle in spessartines. When the ratio increases, the hue angle (Hue h°) decreases accordingly (R2 = 0.96), and the sample color transitions from light orange to dark orange (inset in Fig. 6). This study further focuses on the effect of the Fe/Mn ratio on the hue angle in grossular garnet (Fig. 6). Correlation analysis indicates that when the Fe/Mn ratio is below 20, Mn has a greater influence on color than Fe. In this case, the hue angle increases, shifting the color toward an orange-yellow tone. When the Fe/Mn ratio exceeds 20, Fe dominates the color influence, the hue angle of the sample decreases accordingly, and the color gradually transitions to orange-red.

Influence of standard light source on garnet’s color appearance

In today’s jewelry market, orange-red garnets have gained increasing popularity among consumers due to their fancy colors and affordable prices. When sold in the market, merchants often set up lights above these garnets. Which standard light source can best showcase the beauty of red–orange garnets, and which lighting condition do consumers tend to choose, are the focuses of this study.

The human retina employs three types of cone photoreceptors—S (short-wavelength), M (medium-wavelength), and L (long-wavelength) to mediate color vision. These cones exhibit overlapping but distinct spectral sensitivity profiles, with S cones preferentially responding to blue light, M cones to green, and L cones to red. The differential activation of S, M, and L cones serves as the foundation for trichromatic color discrimination, as the visual system interprets color through the relative excitation ratios among the three cone types. However, the accuracy depends on factors such as illumination spectra, retinal adaptation, and inter-individual variability in cone pigment sensitivity. The CIE 1976 L*a*b* color space can quickly, non-destructively, and accurately quantify the color of gems29,30,31. Lightness (L*) characterizes the brightness of a gemstone’s color, where a higher L* value indicates a more luminous color. Chroma (C*) denotes the saturation level of a single color in the gemstone, such that a higher C* value corresponds to a more vivid and intense color. The chromaticity coordinate a* governs the color transition between green and red, while the chromaticity coordinate b* regulates the shift between blue and yellow. The a* and b* values determine the chroma value C* and hue angle h° of a gem. This color space has been widely applied to study the color mechanisms of various gemstones, including agate, beryl, sapphire, turquoise, chrysoprase, and Xiuyan jade. A Munsell N8 color card served as the background, and measurements were taken under D65, F2, and A illuminants. We used single-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) to evaluate the impact of different standard light sources on garnet color appearance. A difference was considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Different light sources exhibit distinct spectral energy distributions, which determine their color rendering properties by influencing the Color Rendering Index (CRI). Consequently, they produce varying visual colors when illuminating the same gemstone32,33. The P-value was < < 0.01, indicating that the light source had a significant effect on the hue angle (h°) of garnets. Similarly, F represents the between-group variance, and a large F value demonstrates that the light source has an extremely significant influence on the hue angle (h°) of garnets. As shown in Fig. 7, the hue angle of red-to-orange garnets under F2 light source is higher than that under D65 and A light sources. The F2 light source, which is used in commercial and daily office areas, has a correlated color temperature (CCT) of 4150 K. Its spectral energy distribution is higher in the wavelength range λ ∈ (550, 620) nm, causing the F2 light source to lean toward yellow-green tones. Therefore, when the yellow-green-toned F2 light illuminates orange to red garnet samples, it interferes with the display of the samples’ inherent warm tones (such as red and orange), thereby increasing the hue angle of the garnets.

When the gemstone’s hue angle h° falls within (18°, 51°), the hue angle under A light source is higher than that under D65; when h° is in (51°, 62°), the hue angle under D65 exceeds that under A. D65 illuminant simulates the average measurement of daylight on overcast days in any season and at any time of the year in the Northern Hemisphere. With a CCT of 6500 K, D65 light has a uniform distribution across all color spectrums from red to purple. Consequently, the color of red to orange garnet samples under D65 illumination closely resembles their appearance under normal natural light, presenting an objective color display. The standard A illuminant, a typical incandescent light, is often used as lighting in shopping malls. As the visible light spectrum ranges from purple to red, the spectral power of A light increases, making the color of garnets under A light extremely close to their appearance under direct sunlight. When the orange-red A light overlays red garnet samples, the samples appear more orange-toned than under D65, with an increased hue angle. When applied to orange-to-yellow garnets, A light makes the samples lean more toward red tones than under D65, resulting in a decreased hue angle. The stronger the gemstone’s inherent red tone, the less it is affected by light source variations (Fig. 7). Thus, D65 standard light source is suitable for evaluating red to orange garnets; A light source better showcases the vivid colors of red garnets, while F2 light source is optimal for displaying the vibrant hues of orange to yellow garnets.

Owing to the considerable color variation in garnets, customers frequently examine them under different lighting at jewelry counters to assess their quality. Previous studies have shown that standard light sources affect the visual attributes of gemstones34,35,36. However, research on how standard light sources influence observers’ and consumers’ perception and evaluation of garnets remains scarce. Thirty members of FGA (Fellowship of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain) participated in the experiment. They were divided into five groups, each containing three males and three females. Garnets were categorized into yellow-orange and deep red hues and displayed separately. During the experiment, ambient room lighting was turned off, with only three experimental light sources used for illumination. When switching light sources, observers closed their eyes to eliminate short-term memory of the prior light source, followed by a 30-s visual adaptation period while viewing a gray background under the new light source. Participants were prohibited from wearing brightly colored clothing. For color evaluation, a categorical judgment method with a 7-point scale (1–7) was employed, where scores corresponded to "strongly inconsistent," "moderately inconsistent," "slightly inconsistent," "neutral," "slightly enhancing quality," "moderately enhancing quality," and "strongly enhancing quality," respectively. Regarding the influence of light sources on observers’ evaluations, the D65 light source yielded relatively stable evaluation parameters. For garnets of different color systems, significant differences in evaluations were observed between the A and F2 light sources: the A light source received the highest ratings for displaying red garnets, whereas the F2 light source achieved the highest ratings for orange-to-yellow garnets. These results are highly consistent with conclusions from previous experiments. Additionally, female observers exhibited a stronger perception of changes in light sources, with greater variability in their ratings compared to male observers. This may be attributed to women’s greater familiarity with jewelry, as existing studies have indicated that the familiarity of subjects affects the range of preference ratings. It could also stem from physiological differences in color vision between males and females.

Conclusion

-

1.

Rapid FTIR Identification: A non-destructive method identifies pyrope-almandine, spessartine, and grossular garnets using characteristic infrared peak shifts. Key indicators are the position of Peak A (Si–O stretch, 800–1100 cm−1) and the presence/absence of Peak D (Si–O bend, 628 cm−1). The strong inverse correlation between the Si–O band position and lattice parameter a0 validates this approach.

-

2.

Color-Controlling Factors: The manganese (Mn) and iron (Fe) content controls the hue angle (h°) of orange-red garnets. Higher Fe shifts red-series garnets to purplish-red (R2 = 0.91, Illuminant A). Under Illuminant D65, Fe/Mn governs spessartine’s orange-to-yellow transition (R2 = 0.96). Fe/Mn = 20 is grossular’s orange-red transformation threshold: below it, Mn dominates (higher hue angle, orange-yellow); above it, Fe dominates (lower hue angle, orange-red).

-

3.

Optimal Commercial Lighting: Specific lighting maximizes visual appeal: Illuminant A enhances chroma and consumer preference for red garnets. F2 light best accentuates orange-yellow garnets. D65 illumination provides a versatile standard for objective color evaluation.

-

4.

Integration: Spectroscopy, colorimetry and visual preference integration delivers practical strategies for optimizing orange-red gemstone identification and commercial presentation.

Material and methods

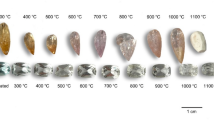

Samples

A total of 40 natural garnet samples were collected, of which 20 were orange-red, the other 20. were dark red. Internal features of the garnet samples were observed using an OLYMPUS SZX16 gemological microscope. No traces of dyeing or heat treatment were detected in the samples. Moreover, some garnets exhibit typical inclusions characteristic of natural garnets, such as rounded crystalline inclusions and syrupy inclusions.

Energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy

The analytical instrument employed for this test is the EDX-7000, an energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometer manufactured by Shimadzu Corporation of Japan. The testing parameters were set as follows: oxidizing atmosphere, 3 mm test aperture diameter, an applied voltage of 50 kV, an operating current of 883 μA and an elemental analysis range spanning from sodium (11Na) to uranium (92U). This analysis was conducted at the Gemmological Institute of China University of Geosciences (Beijing).

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

FTIR spectra were tested by Bruker Tensor 27 spectrometer with 32 scans, 4000–400 cm⁻1 wavelength range in transmission mode via KBr pellet method.

UV–vis spectroscopy

UV–vis spectra were measured by UV-3600 spectrophotometer at 300–900 nm, 1.0 nm interval, single high-speed scan mode.

Colourimetric analysis

Using a Color i5 colorimeter based on the CIE 1976 L*a*b* uniform color space, samples were tested under standard D65, A, and F2 light sources to obtain corresponding color parameters. Prior to testing, the Hunt method was employed to analyze the stability of the instrument.

Data analysis methods

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to explore the influence of light source changes on the color appearance of red–orange garnets, and analyze the impact of chemical composition on garnet color.

Data availability

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Y.G.

References

Sibi, N. & Subodh, G. Structural and microstructural correlations of physical properties in natural almandine-pyrope solid solution: Al70Py29. J. Electron. Mater. 46(12), 6947–6956 (2017).

Krzemnicki, M. S., Hänni, H. A. & Reusser, E. Colour-change garnets from Madagascar: Comparison of colorimetric with chemical data. J. Gemmol. 27, 200–207 (2001).

Gao, Y. et al. Jedi Spinel from Man Sin, Myanmar: Color, inclusion, and chemical features. Crystals 13, 103 (2023).

Wang, X. D. & Guo, Y. The impact of trace metal cations and absorbed water on colour transition of turquoise. R. Soc. Open Sci. 8, 201110 (2021).

Manning, P. G. The optical absorption spectra of the garnets almandine-pyrope, Pyrope and spessartine and some structural interpretations of mineralogical significance. Can. Mineral. 9, 237–251 (1967).

Sun, Z., Palke, A. C. & Renfro, N. Vanadium-and chromium-bearing pink pyrope garnet: Characterization and quantitative colorimetric analysis. Gems Gemol. 51, 348–369 (2015).

Sun, Z. et al. Discovery of color-change chrome grossular garnets from Ethiopia. Gems Gemol. 54, 233–236 (2018).

Tisdall, F. S. H. Spessartites from Madagascar. Gemmologist 31(372), 124–125 (1962).

Williams, C. & Williams, B. New garnets from Africa. J. Gemmol. 35(3), 192–194 (2016).

Adamo, I., Pavese, A., Prosperi, L., Diella, V. & Ajò, D. Gem-quality garnets: Correlations between gemmological properties, chemical composition and infrared spectroscopy. J. Gemmol. 30, 307–319 (2007).

Hoover, D. B. Determining garnet composition from magnetic susceptibility and other properties. Gems Gemol. 47, 28–31 (2011).

Bin, Y., Ying, G. & Ziyuan, L. The influence of light path length on the color of synthetic ruby. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 5943–5943 (2022).

Yujie, G. et al. Jedi spinel from man sin, myanmar: Color, inclusion, and chemical features. Crystals 13(1), 103–103 (2023).

Sun, Z. Y., Palke, A. C., Muyal, J. & McMurtry, R. How to facet gem-quality chrysoberyl: Clues from the relationship between color and pleochroism, with spectroscopic analysis and colorimetric parameters. Am. Miner. 8, 1747–1758 (2017).

Taran, M. N., Dyar, M. D. & Matsyuk, S. S. Optical absorption study of natural garnets of almandine-skiagite composition showing intervalence Fe2+ + Fe3+ → Fe3+ + Fe2+ charge-transfer transition. Am. Mineral. 92, 753–760 (2007).

Manson, D. V. & Stockton, C. M. Pyrope-spessartine garnets with unusual color behavior. Gems Gemol. 20, 200–207 (1984).

Kirillova, N. P., Vodyanitskii, Y. N. & Sileva, T. M. Conversion of soil color parameters from the munsell system to the cie-l*a*b* system. Eurasian Soil Sci. 48, 468–475 (2015).

Guo, Y. Quality evaluation of tourmaline red based on uniform color space. Cluster Comput. 20, 3393–3408 (2017).

Guo, Y., Zhang, X. Y., Li, X. & Zhang, Y. Quantitative characterization appreciation of golden citrine golden by the irradiation of [FeO4]4−. Arab. J. Chem. 11, 918–923 (2018).

Tang, J., Guo, Y. & Xu, C. Color effect of light sources on peridot based on CIE1976 L*a*b* color system and round RGB diagram system. Color Res. Appl. 44, 932–940 (2019).

Tang, J., Guo, Y. & Xu, C. Metameric effects on peridot by changing background color. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A-Opt. Image Sci. Vis. 36, 2030–2039 (2019).

Tang, J., Guo, Y. & Xu, C. Light pollution effects of illuminance on yellowish green forsterite color under CIE standard light source D65. Ekoloji 27, 1181–1190 (2018).

Cheng, R. P. & Guo, Y. Study on the effect of heat treatment on amethyst color and the cause of coloration. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–12 (2020).

Guo, Y. Quality grading system of Jadeite-Jade green based on three colorimetric parameters under CIE standard light sources D-65. CWF and A. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 4, 961–968 (2017).

Jiang, Y. S. & Guo, Y. Genesis and influencing factors of the colour of chrysoprase. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–11 (2021).

Jiang, Y. S., Guo, Y., Zhou, Y. F., Li, X. & Liu, S. M. The effects of Munsell neutral grey backgrounds on the colour of chrysoprase and the application of AP clustering to chrysoprase colour grading. Minerals. 11, 1092 (2021).

Guo, Y., Zong, X. & Qi, M. Feasibility study on quality evaluation of Jadeite-jade color green based on GemDialogue color chip. Multimed. Tools Appl. 1, 841–856 (2019).

Zhang, S. F. & Guo, Y. Measurement of gem colour using a computer vision system: A case study with jadeite-jade. Minerals. 11, 791 (2021).

Liu, W., Qiu, Y. & Guo, Y. Mineralogical characteristics of color-Changing Garnet and the effect of light path length on color. Sci. Adv. Mater. 16, 807–816 (2024).

Qiu, Y. & Guo, Y. Explaining colour change in Pyrope-Spessartine garnets. Minerals 11, 865 (2021).

Zhu, M. & Guo, Y. New insights into the coloration mechanism in spessartines and the impact of Munsell neutral grey backgrounds. Crystals 13, 1529 (2023).

Cui, L., Guo, Y., Tang, J. & Yang, Y. Spectroscopy characteristics and Color-Influencing factors of green Iron-Bearing Elbaite. Crystals 13, 1461 (2023).

Liu, Z., Guo, Y., Shang, Y. & Yuan, B. Research on parameters optimization of digital imaging system in red–yellow jadeite color measurement. Sci. Rep. 12, 3619 (2022).

Bodrogi, P., Lin, Y., Xiao, X., Stojanovic, D. & Khanh, T. Q. Intercultural observer preference for perceived illumination chromaticity for different coloured object scenes. Light. Res. Technol. 49, 305–315 (2015).

Chen, W., Huang, Z., Rao, L., Hou, Z. & Liu, Q. Research on colour visual preference of light source for black and white objects. in Printing and Packaging Technology (Singapore: Springer Singapore), 43–50 (2020).

Deng, X. et al. Experimental setting and protocol impact human colour preference assessment under multiple white light sources. Front. Neurosci. 16, 1029764 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The experiments in this research were completed in the Lab of Gemological Research at School of Gemmology, China University of Geosciences (Beijing).

Funding

This work was supported by the Graduate Innovation Fund Project of China University of Geosciences, Beijing (Project Number: CX2025YC241).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Z. and Y.G. chose raw materials as samples and conducted experiments and data analysis together, M.Z. wrote the main manuscript texts and prepared figures, Y.G. and P.W. revised and corrected the manuscript texts.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, M., Wang, P. & Guo, Y. Light source dependent colour perception in orange red garnets via spectroscopy and colorimetry. Sci Rep 15, 44619 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28580-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28580-8