Abstract

This study investigates the impact of landscape patterns on ecosystem services in the Ruoergai Plateau from 1990 to 2020. Ecosystem services play a crucial role in maintaining the balance of natural ecosystems and facilitating socio-economic development. Using the InVEST model, it quantifies and assesses carbon storage, soil conservation, water yield, and habitat quality. Correlation analysis is employed to explore the interrelationships and constraints among different ecosystem services, while stepwise regression analysis and bivariate spatial autocorrelation are utilized to investigate the impact mechanisms of landscape patterns on ecosystem services. Results indicate that the Ruoergai Plateau has experienced changes and transitions in land use, with grasslands being the primary type showing a decreasing trend. Landscape patterns have significantly altered, with a mitigation of fragmentation observed. Overall, ecosystem services show a declining trend initially followed by an increase. Carbon stock showed a decreasing trend from 1990 to 2010, with a significant increase from 2010 to 2020 and an increase of 0.41 × 108 t. The average carbon density and stock in the study area in 2020 reached 78.48 t.hm− 2 and 3.64 × 108 t, which were mainly concentrated in the wetland and forested land, distributed in the eastern and southwestern parts of the study area. There exist varied trade-offs and coordination among ecosystem services across different regions and temporal scales, while demonstrating a certain correlation with landscape indices. These findings enhance our understanding of how landscape pattern dynamics shape ecosystem service functions, providing valuable insights for regional ecological management and sustainable development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human activities accelerate the evolution of landscape patterns, causing a series of serious socio-economic and ecological problems1,2, severely threatening regional sustainability. Rapid urbanization and land development expansion can alter land use and landscape patterns in specific areas, reducing ecosystem services and habitat quality, resulting in adverse ecological impacts3,4. With rapid population growth and excessive resource consumption, the stability of ecosystems and biodiversity in some regions is severely compromised5,6, and increasingly prominent environmental issues have seriously affected regional economic and social sustainability. Often, in the process of development and utilization, long-term ecological benefits are overlooked, prioritizing economic gains7, resulting in extensive land conversion, rapid landscape alterations, and diminished ecosystem services8. In the 21st century, research and conservation of landscape changes and ecosystem services have become a consensus among governments, the public, and the international academic community9,10.

Landscapes, as the spatial projection of ecosystems on a two-dimensional plane, are geographical entities or land use types with distinct spatial differentiation and functional connections11,12. They constitute a mosaic of diverse land use patterns and regions that differ in structure and function, reflecting the form, proportion, and spatial organization of ecosystems or land use types13. Ecosystem services, as the resources and environmental foundation for human production, life, and sustainable development, refer to the products and services obtained directly or indirectly from ecosystems14,15,16. Driven by economic growth, climate change, and human interference, these services are undergoing rapid changes worldwide. Early research primarily focused on valuing individual ecosystem types—such as forests, grasslands, and wetlands—to quantify their ecological and economic importance. As global awareness of ecosystem degradation increased, scholars began shifting from simple valuation toward integrated assessments of multiple ecosystem functions and their spatial dynamics. This trend has encouraged the development and application of a variety of analytical tools and frameworks. Among them, the Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Trade-offs (InVEST) model has become one of the most widely adopted for spatially explicit evaluation of ecosystem service functions. At the same time, advances in remote sensing, artificial intelligence, and socio-economic modeling have further broadened the analytical scope of ecosystem service studies, leading to the emergence of integrated frameworks that combine ecological, social, and economic perspectives17. However, despite methodological progress, the spatial heterogeneity and degradation of ecosystem services remain key challenges, as they disrupt land-use balance and threaten human well-being and sustainable development18,19. Understanding these spatial variations is therefore essential for effective landscape planning and management20. In this context, landscape patterns provide the spatial carrier of ecosystem services, while ecosystem services represent the functional essence of landscape structure21,22.

The intricate structure of ecosystems endows them with multiple ecological functions, including climate regulation, water conservation, pollutant degradation, maintenance of biodiversity, recreational and aesthetic value, as well as fulfilling religious and cultural needs23,24. Quantifying the dynamic changes in land use, landscape patterns, and ecosystem services in terms of quantity and space can elucidate their patterns of change, laying the groundwork for future forecasting25. Based on this, exploring the trade-offs and synergies among ecosystem services at multiple levels and scales, as well as understanding their interrelationships and mechanisms of action, enables a precise understanding of their spatiotemporal variations and spatial expressions in the study area. This is crucial for tailor-made utilization of ecosystem service functions according to local conditions26,27,28.

There exists spatial autocorrelation between landscape patterns and ecosystem services. While most studies focus on balancing and synergizing them, they overlook their relationships with other landscape patterns, failing to fully consider the spatial autocorrelation between them, which reduces the explanatory power of their relationship29. Clarifying the quantitative and spatial relationships between landscape patterns and ecosystem services is crucial for exploring effective approaches to sustainable ecosystem research30,31. Different landscape patterns correspond to different ecological processes, resulting in varying impacts on ecosystem services32,33. Specifically, changes in landscape patterns can affect the types, areas, and spatial distribution of ecosystems, thus influencing ecosystem structure and function, altering material, energy, and ecological flows within landscapes, and ultimately affecting the provision and maintenance of ecosystem services34. Studies on the effects of landscape pattern changes on ecosystem services often overlook the strong spatial spillover effects exhibited by ecosystem services as public goods35. That is, the ecosystem services of a local unit are influenced not only by its own supply capacity but also by the services of neighboring units. While extensive studies have explored the linkages between landscape patterns and ecosystem services, most have neglected these spatial spillover effects. These spillovers imply that local ecosystem service provision is shaped by both internal ecological capacity and interactions with surrounding landscapes36. Addressing this limitation requires expanding the analytical scope and integrating diverse land use types, which can help reveal cross-scale spatial dependencies more effectively.

The Ruoergai Plateau, located on the northeastern edge of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, lies within the Yellow River Source Region37. As a significant wetland conservation area in western China, it possesses unique plateau wetlands with considerable carbon storage and water conservation ecological functions38,39, playing a crucial role in safeguarding human well-being and societal development40. Identifying the impact of landscape patterns on ecosystem services provides a basis for formulating ecosystem protection decisions and landscape planning41. Therefore, this study aims to address the research gap by quantifying trade-offs and synergies among multiple ecosystem services in the Ruoergai Plateau, examining the influence of landscape patterns and spatial spillover effects, and providing scientific evidence for ecosystem management and policy-making in plateau wetland regions.

Materials and methods

Description of the ruoergai plateau

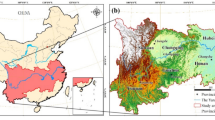

The Ruoergai Plateau is located at 100°40′-104°50′E and 31°50′-34°30′N, situated in the northeastern part of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and the upper reaches of the Yellow River basin. The administrative division of the study area includes Ruoergai, Hongyuan, Aba and Songpan counties in Sichuan Province and Maqu County in Gansu Province, where Sichuan, Gansu and Qingdao provinces meet (Fig. 1). It is an important area for water conservation and habitat quality protection, with a unique geographical location and climate environment that bestow a high ecological value upon the region. The Ruoergai Plateau features a plateau basin land-form, with elevations ranging from 1057 to 5550 m, sloping from southwest to north-east. The area experiences a typical sub-frigid humid and semi-humid monsoon cli-mate. The annual average precipitation is between 600 and 800 mm, with spatially uneven distribution, concentrating mainly from May to August. There is no absolute frost-free period in the region.

Data sources

Using Landsat series remote sensing images as the foundational data for land use type interpretation and research, accuracy validation was conducted. Taking into ac-count the actual characteristics of the study area, the land use classification was set to eight categories: cropland, forest, grassland, wetland, water bodies, glaciers, desert, and built-up land. Finally, the classification results were combined with the field survey results from 2020. Supervised classification and visual interpretation results were adjusted and verified. All data sources can be found in Table 1.

The land use maps were generated using Landsat TM/ETM+/OLI images obtained from the Geospatial Data Cloud (https://www.gscloud.cn/search), with a spatial resolution of 30 m. The images underwent standard preprocessing steps, including geometric correction, atmospheric correction, and cloud/shadow removal. Supervised classification combined with visual interpretation and field survey data from 2020 was applied to produce the final land use maps. Classification accuracy was assessed using overall accuracy and the Kappa coefficient, ensuring reliable input for subsequent ecosystem service modeling.

Methods

Land use is influenced by the interplay between human activities and the natural environment. It can objectively reflect the dynamic processes of the impact and transformation of Earth’s land surface resulting from human activities to a certain extent8. Clarifying the trends in land use and landscape patterns can reveal the changing processes of landscape elements in the study area. This has a certain reference value for understanding the landscape ecological evolution process in the research area. The accuracy of land use classification was evaluated using overall accuracy and Kappa coefficients, methods widely applied in land use studies42.The overall accuracy of land use interpretation in 1990, 2000, 2010 and 2020 was 87.3%, 92.1%, 90.3%, 89.8% and 95.3%, respectively, and the corresponding Kappa coefficients were 0.84, 0.86, 0.88 and 0.89, respectively. The results of the interpreted land use types have good accuracy and can be used for further analysis. To reveal the landscape pattern characteristics of the study area, this research selected a series of landscape pattern indicators at two levels: landscape and class. It describes the landscape pattern features of the study area in terms of landscape aggregation, fragmentation, shape complexity, diversity, and other aspects (Table 2). All calculations were conducted using the Fragstats platform.

For the assessment of ecosystem services, the Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Trade-offs (InVEST) model was adopted, which has been widely used in spatially explicit studies of ecosystem services43,44,45.This model can simulate the amount and spatial distribution of ecological services by constructing different land use scenarios, and was selected because it integrates land use patterns with ecological processes, making it well-suited for complex and ecologically sensitive regions such as the Ruoergai Plateau. The Ruoergai Plateau region is significant for water provision and habitat conservation, thus, four representative ecosystem services including carbon storage, soil conservation, water provision, and habitat quality are selected for discussion.

Carbon sequestration service

Terrestrial ecosystems play a vital role in regulating the global carbon cycle, with carbon storage reflecting the total amount of carbon retained within these systems. However, total carbon storage represents an intermediate ecological function rather than a final ecosystem service, as it does not directly provide human welfare or economic benefits. To better align with the ecosystem services framework, this study therefore focuses on carbon sequestration, defined as the temporal change in carbon storage, which constitutes a final ecosystem service by directly contributing to atmospheric carbon reduction, climate regulation, and human well-being.

To quantify carbon sequestration across the Ruoergai Plateau, we applied the InVEST carbon storage module, which integrates land-use data to calculate total carbon storage for each land-use type as follows:

\(\:i\) represents a specific land use type, \(\:{C}_{i}\) denotes the total carbon density for land use type \(\:i\); \(\:{C}_{i-above}\text{、}{C}_{i-below}\text{、}{C}_{i-soil}\text{、}{C}_{i-dead}\text{、}{C}_{total}\) represent the corresponding carbon densities for land use type \(\:i\), including aboveground vegetation carbon density, belowground live root carbon density, soil carbon density, dead vegetation carbon density, and total carbon storage, respectively; \(\:{S}_{i}\) represents the total area of land use type\(\:\:i\); \(\:n\) represents the total number of land use types. The carbon stock is obtained by multiplying the carbon density by the area of the region.Ctotal, t1 and Ctotal, t2 are the total carbon stocks at the beginning and end of the period, respectively, and Δt is the time interval in years. Positive values of CS indicate net carbon accumulation, while negative values indicate net carbon loss.

Carbon density data were obtained from National Data Center for Ecological Sciences (http://www.cnern.org.cn) and Soil Dataset of China Based on the World Soil Database Table 3.

Soil conservation function

The SDR module in the InVEST model primarily relies on the Universal Soil Loss Equation for its calculations. The specific principles are as follows:

SD represents the soil conservation amount, RKLS denotes the potential soil erosion amount, USLE represents the actual soil loss, The units for all three are t·hm− 2·a− 1; R represents the precipitation erosion force factor (MJ·mm·(hm− 2·h− 1·a− 1)); K represents the soil erodibility factor (t·hm− 2·h·(hm− 2·M, J− 1·mm− 1); LS represents the slope length-slope factor (dimensionless); C represents the cover management factor (dimensionless); P represents the support practice factor (dimensionless) in the context of soil conservation.

Water supply function

The InVEST Water Yield model utilizes algorithms based on the Budyko curve and principles of water balance to estimate water production. The model calculates water yield by subtracting evapotranspiration from precipitation for each pixel. The total water yield at the watershed or sub-watershed level is then aggregated and averaged. The principle is as follows:

\(\:{\text{Y}}_{\text{j}}\) represents the annual water supply of raster cell j ,while \(\:{\text{A}\text{E}\text{T}}_{\text{j}}\) represents its actual evapotranspiration, and Pj is the annual mean precipitation of raster cell j. \(\:PET\left(x\right)\) refers to the potential evapotranspiration of raster cell x, \(\:{K}_{c}\left({l}_{x}\right)\) is the crop coefficient for the reference crop, and \(\:\:\omega\:\left(x\right)\) is a non-physical parameter related to climate and soil properties. Z is the Zhang coefficient, which represents the soil water storage and release available for plant use and ranges from 1 to 10. When precipitation is mainly in winter, the value is around 10; when precipitation is mainly in summer or is relatively evenly distributed throughout the year, the value approaches 1.

Habitat quality function

The Habitat Quality module in the InVEST model assesses the level and degradation of habitat quality in the study area. It calculates the threat level of surface environments to biodiversity by analyzing current land cover types and future land use scenarios. The evaluation of habitat quality is based on the intensity of external threats and the sensitivity of the ecosystem itself to those threats. The principles are as follows:

\(\:{Q}_{xy}\) represents the habitat quality index for grid cell x in land use type j; \(\:{H}_{j}\) represents the habitat suitability for land use; \(\:{D}_{xy}\) represents the habitat stress level for grid cell x in land use type j. \(\:{w}_{r}\) is the weight of the stress factor; \(\:{\beta\:}_{x}\) is the accessibility level for grid cell x where 1 indicates extremely easy accessibility; \(\:{S}_{jr}\) represents the sensitivity of land use type j to stress factor r; K is the half-saturation constant; \(\:{i}_{rxy}\) represents the impact of stress factor; \(\:\:{d}_{xy}\) represents the Euclidean distance between grid cells x and y; \(\:{d}_{rmax}\) is the maximum impact distance of stress factor r.

Based on the basic overview of the study area and considering the environmental characteristics of the Ruoergai Plateau, cropland and built-up land are selected as the main stressors. Referring to the InVEST user guide and relevant research findings, cropland and built-up land are assigned values. The threat distance for cropland and built-up land is set to 3 km and 8 km, respectively, with weights of 0.7 and 1, decay functions of linear and exponential, and values of 0 for other land types. Grid data are obtained separately with cropland and built-up land as threat sources, with a spatial resolution of 30 m Table 4.

For the tradeoff and collaborative analysis among ecosystem services, we use correlation analysis, Pearson correlation coefficient is used to describe the relationship between ecosystem services, SPSS software is used to calculate the correlation, and GeoDA software is used to conduct the tradeoff collaborative analysis.

Correlation analysis and local Spatial autocorrelation

SPSS software is used to calculate the correlation, and the calculation formula is as follows:

R is the correlation coefficient between variables, and the value range is [-1,1]; \(\:{x}_{i}\) and \(\:{y}_{i}\)represent the values of the variables x and y in year \(\:i\), respectively; \(\:x\) and\(\:\text{y}\) represent the average values.

Tradeoff collaborative analysis based on grid cells using GeoDA software. The calculation formula is as follows:

\(\:{w}_{ij}\) is the spatial weight value, n is the total number of all regions in the study area, and \(\:{I}_{i}\) represents the local Moran index of the \(\:i\) region.

For the analysis of the impact of landscape index on ecosystem services, we first conducted multiple stepwise regression analysis, taking ecosystem service function as the dependent variable and landscape index of landscape and type level as the independent variable, and assigned the data to the created 1 km×1 km fishing net data after normalization, and then conducted stepwise regression analysis to determine the impact of landscape pattern on ecosystem services.

In order to explore the spatial agglomeration and dispersion characteristics between ecosystem services and landscape pattern index, bivariate global spatial autocorrelation method was adopted to analyze the spatial relationship between landscape pattern and ecosystem service function. Global bivariate Moran’s I could be used to study whether there was spatial correlation between ecosystem services and landscape pattern index.

To ensure the robustness of the correlation and spatial autocorrelation analysis results, the potential influence of spatial data aggregation was further examined. Since the original datasets were collected at a 30 m spatial resolution and aggregated to a 1 km × 1 km grid, such rescaling may cause a loss of spatial detail or alter the sensitivity of spatial associations. Therefore, the impacts of data aggregation were carefully assessed by comparing spatial statistics and correlation results across multiple resolutions. This approach helped ensure that the aggregated data preserved the essential spatial patterns and statistical relationships observed at finer scales, thereby maintaining the validity and reliability of the analysis.

Multiple stepwise regression analysis and global autocorrelation analysis

The formula of multiple stepwise regression analysis is as follows:

Y is the explanatory variable; \(\:{\beta\:}_{0}\) is the regression constant. \(\:{\beta\:}_{1}\) is the partial regression coefficient of the independent variable \(\:{X}_{1}\). \(\:{\beta\:}_{2}\) is the partial regression coefficient of independent variable \(\:{X}_{2}\). \(\:{\beta\:}_{k}\) is the partial regression coefficient of the independent variable \(\:{X}_{k}\). k is the number of independent variables.

The global autocorrelation formula is as follows:

I is the global bivariate spatial autocorrelation index, N is the number of research units, \(\:{W}_{ij}\) is the adjacent spatial weight matrix, \(\:{z}_{i}^{e}\) is the ecosystem service of unit i, and \(\:{z}_{j}^{u}\) is the landscape pattern index of unit j. The global Moran’s I value is generally between − 1 and 1. If the value is greater than 0, it indicates that there is a positive autocorrelation and the elements tend to cluster. If the value is < 0, it indicates that there is a negative autocorrelation and the elements tend to be dispersed. If the value is close to 0, it indicates that there is a random distribution. In addition, the P-value is often used as a significance test.

To ensure the robustness and reliability of our results, we conducted a comprehensive validation of the ecosystem services estimated using the InVEST model. This validation process included cross-referencing model outputs with multiple high-quality data sources, such as satellite imagery and field observations. Furthermore, the results were compared with findings from previous studies conducted in ecologically comparable regions to assess their consistency and credibility. This multidimensional validation strategy reinforces confidence in the accuracy of our assessments of carbon storage, soil conservation, water yield, and habitat quality.

Results

Land use service

The study area is located in a remote area of western China, where economic development is relatively slow and land use adjustment and transformation lags behind.

Between 1990 and 2020, grassland dominated the study area, accounting for over 80% of the total area, followed by forest land at 15%. Overall, there was an increase in forest, water, glacier, and barren, while cropland and wetland decreased. Grassland remained stable, and although construction land had the smallest proportion, it showed a gradual increase. Since the 20th century, rapid economic development has led to significant changes in land use, such as extensive expansion of buildings and reduction of cropland. The study area located in a remote area of western China, has experienced relatively slow economic development, resulting in lagging adjustments and transitions in land use. In recent years, continuous decrease in cropland, gradual increase in forest land, the trend of wetland restoration, and a reduced rate of increase in construction land reflect ecological recovery and the influence of national policies on local land use changes (Fig 2).

From the spatial distribution of land use (Fig. 3), grassland exhibited extensive distribution, occupying the largest area and maintaining a stable landscape structure. Forest was mainly located in the eastern and southwestern parts of the study area, showing clustered distribution patterns. Wetland and water were primarily distributed in the central-northern part of the study area, mostly concentrated within the boundaries of Ruoergai County, characterized by large-scale aggregation and small-scale dispersion.

Landscape pattern changes and urbanization impacts

The landscape spatial pattern comprises hierarchical systems, exhibiting different structures and functions across various spatial scales. From Fig. 4, AREA_MN gradually increased from 1990 to 2010 but significantly decreased after 2010, suggesting an increase in landscape fragmentation. The urbanization process in some areas of the Ruoergai Plateau led to a substantial increase in construction land, intensifying landscape fragmentation, with grassland fragmentation being a predominant factor affecting the overall landscape. Some landscape pattern indices fluctuated over time, indicating the instability of landscape pattern changes. From 1990 to 2020, PD, NP, and LPI decreased, indicating a reduction in patch density and fragmentation, with a decrease in dominant patch area. ED and TE decreased, indicating a trend toward regularity at the edges. LSI and DIVISION decreased, indicating a more clustered distribution. SHDI decreased, suggesting a simplification of landscape pattern. LJI decreased, indicating a transition from dispersed and fragmented distribution of landscape types to contiguous distribution, with increased cohesion among patches of the same type.

Carbon storage service

According to statistical analysis, the average carbon density of Ruoergai Plateau in 1990, 2000, 2010 and 2020 is 78.24 t·hm− 2, 78.14 t·hm− 2, 78.07 t·hm− 2 and 78.48 t·hm− 2 respectively. The corresponding total carbon storage is 3.64 × 108 t, 3.63 × 108 t, 3.62 × 108 t, and 3.64 × 108 t. The distribution of carbon storage services has strong concentration, with high values distributed in the eastern and southwestern parts of the study area, and low values in some areas of the northwestern and southern parts of the study area. From 1990 to2010(Fig. 5 ), the carbon storage in study area exhibited a decreasing trend followed by an increase, mainly due to the degradation and reduction of forest resources, which serve as the primary carbon sinks. In the past decade, the continued implementation of policies promoting afforestation and grassland restoration has been one of the reasons for the increase in carbon sequestration46.

To better capture spatial heterogeneity, the Ruoergai Plateau was classified into three types of carbon stock change: significant decrease, little change, and significant increase, as shown in Fig. 6. Raster subtraction was used to calculate carbon stock changes for the periods 1990–2000, 2000–2010, 2010–2020, and 1990–2020. The analysis shows that carbon loss and gain coexist across the study area, with an overall increasing trend of total carbon stocks by 0.24 × 10⁸ t. From 1990 to 2010, carbon decreases were concentrated near wetlands, whereas 2010–2020 saw significant carbon stock increases within wetland areas. Grassland-dominated regions remained relatively stable. These patterns indicate that the observed carbon sequestration changes are closely linked to wetland restoration, protection, and sustainable land management practices, enhancing the carbon retention capacity of the landscape.

Soil conservation service

The soil conservation capacity in the study area follows the order from highest to lowest: 2020 (4.52 × 1010 t), 1990 (3.09 × 1010 t), 2010 (2.79 × 1010 t), and 2000 (2.43 × 1010 t). The lowest soil conservation occurred in 2000, attributed to extensive deforestation and increased construction land in the early 21st century. Subsequently, with the implementation of various environmental protection policies and the initiation of afforestation and grassland restoration policies, soil conservation gradually increased, and soil conservation capacity began to recover. Overall, the soil conservation in most regions is at a moderate or high level, but there is heterogeneity in spatial distribution. The regions with better soil conservation function were mainly distributed in the surrounding areas of the study area. These regions were mainly forests with rich vegetation types and stronger soil conservation ability. In contrast, the central parts of the study area are predominantly low-value areas, comprising grasslands, water, and wetlands, with flat terrain and high summer precipitation, leading to significant soil erosion and weaker soil conservation capacity Fig 7.

Water yield service

The overall water supply capacity in the study area has increased. The total water supply amounts in 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020 were 168.21 × 108 mm, 146.56 × 108 mm, 169.82 × 108 mm, and 247.40 × 108 mm respectively. From 1990 to 2020, the water supply in the study area increased by 79.20 × 108 mm, with the most significant increase observed from 2010 to 2020, totaling 77.58 × 108 mm. The spatial distribution pattern of water yield in the study area has undergone significant changes over the past 30 years, showing a trend of decreasing and then increasing water supply capacity. In 1990, the water yield in the study area was unevenly distributed, with lower supply in the western and northern parts and higher supply in the southwest and south, ranging from 0 to 921.662 mm. From 2000 to 2010, the annual water yield in the Ruoergai Plateau region showed a southwest-high, northeast-low distribution trend, ranging from 0 to 785.55 mm and 0 to 839.50 mm respectively. In 2020, the water supply exhibited a north-south high, central low trend, with a range of 0 to 932.50 mm.Between 1990 and 2000, the loss of some ecological land due to economic development and construction led to a weakening of water supply47.

The subsequent increase in water yield, particularly from 2010 to 2020, may be influenced not only by land use and landscape pattern changes such as wetland restoration, afforestation, and grassland management but also by climatic factors including precipitation and evapotranspiration. Previous studies have shown that these climatic variables can significantly alter water yield patterns and should be considered alongside land use changes when interpreting temporal trends48 Fig 8.

Habitat quality

The habitat quality index in the study area for the years 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020 were 0.727, 0.731, 0.732, and 0.731, respectively. The overall habitat quality gradually improved, demonstrating a stable trend. According to the spatial and temporal distribution of habitat quality in the study area from 1990 to 2020 (Fig. 9), the habitat quality in the central region increased; The habitat quality was high in most areas, especially in the southern and western parts of the study area, mainly because there were abundant vegetation in these areas and the forest coverage rate was relatively high. The second is the large area of central and northwest areas, mainly related to the large area of grassland coverage. From 1990 to 2020, the habitat quality of wetland distribution area in the middle of the study area increased significantly, mainly due to the implementation of large-scale wetland protection policies and measures in the study area around 2000, and the area of wetland resources increased. Due to the extensive construction land coverage in the southeastern edge of the study area, the quality of habitat is low and there are spatial aggregation phenomena, mainly in the form of agglomeration and radiation distribution. The increase of construction land is one of the threatening factors of habitat quality degradation in the study area.

Using the InVEST model for habitat quality analysis reveals the degradation trends in the study area from 1990 to 2020 (Fig. 10). Over the past 30 years, most regions in the study area exhibited no significant changes in habitat quality, while certain areas displayed clustering characteristics. From 1990 to 2020, the southwestern part of the study area experienced continuous degradation, with a narrow north-south distribution. The central wetland distribution area showed noticeable habitat degradation from 1990 to 2000, but experienced substantial improvement from 2000 to 2020, leading to a reduction in the level of habitat degradation. Additionally, the southwestern and northeastern parts of the study area witnessed habitat degradation due to urban development.

Discussion

Ecosystem service trade-off and synergy analysis

Correlation analysis of ecosystem services

Pearson parameter tests and correlation analyses for carbon storage (CS), soil conservation (SDR), water yield (WY), and habitat quality (HQ) at different time periods are presented in Table 5; Fig. 11. There are significant synergistic relationships between the four ecosystem services, although some changes occur over the 30 years. Specifically, there is a strong synergistic relationship between CS and SDR from 1990 to 2020, as indicated by significant tests at the 0.01 level, suggesting that stronger soil conservation leads to less erosion and more biomass, thus richer carbon storage49. Similarly, high vegetation coverage contributes to increased soil conservation50. The correlation between CS and WY transitions from significant positive correlation to significant negative correlation, indicating a shift from synergy to trade-off. During 2010, the synergy between HQ and WY weakens, and by 2020, it transforms into a negative correlation, suggesting other influencing factors. Over 1990–2020, the correlation between SDR and WY gradually decreases, with the coefficient dropping from 0.259 to 0.002, indicating a weakening synergy due to increased urbanization, population density, human activities, and decreased vegetation coverage, which result in reduced soil conservation and weaker correlation with water yield.

This shift from synergistic to trade-off relationships likely reflects intensified land-use changes and hydrological modifications, which altered the balance between water supply and ecosystem functions. Increased impervious surfaces and vegetation degradation can disrupt infiltration and evapotranspiration processes, thereby reducing the ability of carbon-rich or vegetated areas to enhance both carbon storage and water yield simultaneously. Similarly, the weakening of HQ–WY synergy after 2010 may have been influenced by both human activities and climatic variability, such as changes in precipitation and evapotranspiration patterns.

These results are consistent with previous studies emphasizing the role of land-use intensity and climate drivers in reshaping ecosystem service relationships, suggesting that trade-offs tend to emerge under conditions of ecological stress or rapid urbanization51,52,53.

Spatiotemporal distribution of ecosystem services relationships

In order to further explore the spatial balance and synergy of different ecosystem services, spatial weight matrices were constructed in the spatial statistical analysis software GeoDA, and local spatial autocorrelation analysis was conducted. As depicted in Fig. 12, from 1990 to 2000, there was an overall pattern of synergy among various ecosystem services. However, from 2000 to 2020, he relationships and clustering patterns between some ecosystem services changed.

Between 1990 and 2000, CS-SDR showed a clustered and intersecting distribution with a concentrated balance relationship. From 2000 to 2020, there was a low-low clustering in the central and northern regions, dominated by forest landscapes. In the southwest and southern parts, sporadic high-high synergy and low-high balance distributions emerged, mainly due to developed and agricultural land. This demonstrates that an increase or decrease in one ecosystem service leads to corresponding changes in another.These patterns suggest that land-use intensification weakened synergies in developed areas, whereas ecological restoration and afforestation efforts enhanced carbon–soil interactions in forest-dominated regions, consistent with the findings of regional studies on ecosystem service coordination51. The overall change in spatial correlation of HQ-CS is minimal, with most areas showing insignificance. In the central wetland region of the study area, HQ-CS transitions from low-high balance to low-low synergy, reflecting an increasingly evident mutual influence between the two services in the wetland area. In the eastern and southwestern high-altitude areas, as well as some developed land, the balancing relationship of HQ-SDR gradually weakens while the synergistic relationship strengthens, partly due to afforestation projects in the 21st century, leading to a significant improvement in ecological quality. By 2020, the synergistic relationship between the two in wetland distinctly differs from other regions, indicating the crucial role of wetland development. Spatial correlation of WY-CS shows more pronounced changes in the western and southern regions, predominantly characterized by balance relationships, with insignificant distribution of synergy relationships. And the land use types are mainly grassland and forest.

The spatial correlation of WY-HQ exhibits significant changes, initially marked by insignificance and low-low synergy in most areas. Subsequently, there’s an increase in the proportion of areas with low-high balance and high-low balance. By 2020, insignificance predominates again. Wetlands, however, show minimal change, maintaining a stable distribution of low-low synergy.The spatial relationship of WY-SDR can be divided into two stages: from 1990 to 2000, it was primarily characterized by insignificance and synergy, while from 2000 to 2020, it mainly exhibited low-low clustering synergy.

The impact of landscape patterns on ecosystem services

Correlation analysis of landscape index and ecosystem services

Based on the landscape indices and data of the four ecosystem services from 1990 to 2020, stepwise regression analysis was conducted with the landscape pattern indices for each phase as independent variables and the four ecosystem services as dependent variables. The optimal fit results are shown in Table 6. Regression results (Landscape Pattern Index and Ecosystem Service)., including regression outcomes and equation validation.

For CS, it’s mainly positively correlated with ED and AI, and negatively correlated with LPI, indicating that more active landscape edge elements and higher aggregation favor CS effectiveness. From 1990 to 2020, the landscape pattern indices affecting carbon storage function decreased. In 2020, carbon storage function was only related to AI and LPI, reflecting a certain degree of stability in CS.

The influencing factors of SDR have significantly changed. In 1990 and 2020, AREA_MN was the main factor, while in 2000 and 2010, it was LPI. This indicates that higher shape variability and landscape fragmentation, with more complex patch shapes, are conducive to improving soil conservation. This contrasts with the findings of Wei54 in Chengdu, where patch area was positively correlated with soil conservation. This difference is because urban green spaces are limited by built-up areas, resulting in weaker stormwater retention. In contrast, the study area has more forest and grassland cover, enhancing its ability to resist erosion, making the complexity of the landscape more significant for soil conservation than just its area.

For WY, in 2000 and 2010, the correlation with landscape indices did not pass significance tests, indicating a minor influence of landscape pattern factors. However, in 1990 and 2020, it showed a positive correlation with PD and LPI, and a negative correlation with IJI. This is because as the largest patches increase, vegetation canopy effectively reduces rainfall energy loss, gradually strengthening natural retention of precipitation, and enhancing water supply capacity54. Zhou55 also noted that lower regional landscape fragmentation corresponds to lower ecosystem services. Chen56 found that in landscapes, the more complex the patch composition, the higher the landscape diversity, which benefits WY.

For HQ, from 2010 onwards, it remains stable under the influence of AREA_MN, indicating that smaller patch sizes and higher complexity are beneficial for HQ improvement. However, from 1990 to 2000, this function was influenced by ED and DIVISION, with higher HQ associated with more fragmented patch edges and a more complex landscape. Liu57 also noted that in the Qinling Mountains, as aggregation increases and landscape differentiation decreases, contributions to the ecosystem also increase. High habitat quality in the study area is mainly distributed around forested areas, consistent with the aforementioned research findings.

The results above indicate that enhancing landscape aggregation and diversity in the study area can have positive effects on various ecosystem services, promoting the improvement of ecosystem service structure and function.

Based on the characteristics of land use structure and the dynamic changes in ecosystem services, it is noted that the four types of ecosystem services are mainly concentrated in forests, grasslands, and wetlands. Therefore, this section specifically explores the impact of landscape patterns on ecosystem services for these three types (Table 7).

For forests, only the 1990 CS and the 2010 and 2020 WY passed significance tests, indicating that forests are relatively stable and less influenced by landscape pattern indices. Regression results show a negative correlation between CS and AREA_MN, a positive correlation between WY in 2010 and ED, and a positive correlation between WY in 2020 and LPI. Combining ecosystem services of forests with previous research suggests that richer landscape types enhance regional carbon sequestration capacity56. The proportion of the largest patches in forests is significantly positively correlated with flood regulation functions, as forests strengthen interactions between water, soil, and plants, enhancing water infiltration and maintaining a stable water yield58.

Various landscape patterns in grasslands affect ecosystem services, reflecting the instability of this land cover class’s ecosystem services, but the correlation’s landscape pattern indices are decreasing, indicating a trend towards stability. ED and PD are positive factors affecting grassland water yield. Su59 and Yu60 studies indicate that intensified landscape fragmentation will affect ecosystem composition, structure, ecological processes, and biodiversity, with a promoting effect on WY. SDR shows a positive correlation with PD in 1990, 2000, and 2010, implying that a higher number of patches and active ecological processes are conducive to soil conservation.

In wetlands, CS is negatively correlated with AREA_MN and positively correlated with LPI, indicating that larger dominant patches lead to stronger CS. In 2020, LPI promotes the enhancement of both WY and CS, fostering better connectivity among dominant patch types. As the number of dominant patches in wetlands increases, there’s an increase in runoff interception, landscape activity, which benefits CS enhancement61.

Comparative results among three land uses indicate that wetlands’ ecosystem services are more constrained by landscape pattern indices, reflecting the wetlands’ significant yet unstable role in ecosystems. The impact of landscape patterns on ecosystem services is ranked as wetlands > grasslands > forests, primarily influenced by LPI, ED, and AREA_MN. Between 1990 and 2020, landscape pattern indices of wetlands and grasslands significantly influenced ecosystem services. This is attributed to substantial changes in the areas of wetlands and grasslands due to economic development and evolving industrial structures. The increased fragmentation of landscapes in the Ruoergai Plateau region is a result of inappropriate usage patterns.

The spatial lag terms of each ecosystem service regression model are significant at the 0.001 level, with positive coefficients, indicating that optimizing ecosystem services in neighboring units leads to improvements in the focal unit’s ecosystem services. Additionally, spatial error terms in all models are significant, suggesting that besides landscape pattern indices, other factors influence ecosystem services.

Spatial autocorrelation analysis between landscape and ecosystem services

According to the stepwise regression results of landscape pattern indices and ecosystem services, six key landscape pattern indices (AI, AREA_MN, ED, LPI, LSI, and PD) were selected for global spatial autocorrelation analysis (Table 8) and local spatial autocorrelation analysis of landscape pattern indices and the four ecosystem services from 1990 to 2020.

The results indicate varying degrees of correlation between ecosystem services and six landscape pattern indices from 1990 to 2020, with Moran’s I showing little inter-annual variations, all less than 0.1. The correlation between landscape pattern indices and WY is weak. Ecosystem services exhibit weak negative correlations with AI, AREA_MN, and LPI. Overall, they show a strong positive correlation with ED, LSI, and PD, implying higher ecosystem service values in regions with good landscape connectivity, high diversity, and regular shapes. Based on the global spatial autocorrelation analysis, there exists a significant spatial dependency between ecosystem services and landscape pattern indices.

In geographic space, local spatial autocorrelation analysis of ecosystem services reflects the distribution characteristics, patterns, and clustering tendencies or interdependencies4. Analyzing with GeoDA software, there are noticeable differences in the spatial distribution of LISA cluster maps between various landscape indices and four ecosystem services.

From Fig. 13 CS, CS exhibits high-low and low-high clustering distributions with AI, AREA_MN, and LPI in the central and northern regions of the study area, indicating that higher landscape indices correspond to lower landscape fragmentation and higher carbon storage capacity. However, the correlation between CS and ED, LSI, and PD is not significant in most parts of the study area.

From Fig. 13 SDR, Except for some grasslands and wetlands in the central part of the study area, all landscape indices show no significant clustering with SDR. Large and complex forest patches contribute significantly to soil conservation. Additionally, the distribution of various land uses also plays a significant role in this service62. Compared to flat terrain, the landscape types in the low-altitude central area are less conducive to soil conservation, such as seasonal variations in grasslands and wetlands, affecting soil conservation ability58. Moreover, the region’s high elevation and extensive vegetation cover greatly mitigate soil erosion63.

From Fig. 13 WY, WY exhibits highly similar spatial distributions with various landscape indices. WY show high-high clustering strip-like distributions in the western region with AI, AREA_MN, and LPI; for ED, LSI, and PD, they exhibit low-low clustering point-like distributions in the northeast. The study area’s surface runoff is primarily supplied by atmospheric precipitation and snowmelt64. The region has high terrain edges and low central areas, influenced by summer southwest monsoons, making high-altitude and edge areas susceptible to warm, humid air currents65. Surface runoff, rainfall, and other factors influence the spatial distribution patterns of different landscape types, affecting evaporation, transpiration, and infiltration in the water cycle, making water conservation services more significant.

From Fig. 13 HQ, HQ shows an insignificant relationship with most landscape indices. AI, AREA_MN, and LPI exhibit low-high clustering, primarily distributed in the eastern and southwestern regions with higher altitudes; a small portion shows low-low clustering, scattered in the central part. ED, LSI, and PD display high-high clustering, mainly distributed in the eastern and southwestern parts.

Conclusions

Despite the comprehensive assessment, some limitations exist. Data scarcity in the study area and the use of global or regional datasets may introduce uncertainties. In addition, the InVEST models simplify complex ecological processes and may not fully capture dynamic interactions. Future research could focus on incorporating higher-resolution data and scenario-based simulations to improve model accuracy and better inform land management strategies.

During the period from 1990 to 2020, grassland area maintained an absolute advantage, with reduced fluctuations; wetland area showed a trend of first decreasing and then increasing, with 2010 as the turning point; forest and water area generally increased. There have been significant changes in the landscape pattern of the study area, with a trend towards simplification and a shift from dispersed and fragmented distribution of landscape types to contiguous distribution. The level of ecosystem services first decreased and then increased. Carbon storage functions are mainly concentrated in grasslands and forests. Grasslands and forests play important roles in water supply. Forests have the highest habitat quality index, followed by water bodies, grasslands, and wetlands. There are significant trade-offs and synergies between the four ecosystem service functions, with some degree of change over the 30-year period.

Some landscape indices significantly influence ecosystem services. Carbon storage generally benefits from higher AI values; soil conservation favors lower LPI values; water yield benefits from higher patch aggregation and more dominant landscape types between 1990 and 2020; for habitat quality, fragmented patch composition and complex landscapes correlate with higher quality. The impact of landscape indices on ecosystem services is wetlands > grasslands > forests.

The spatial heterogeneity of landscape indices’ correlation with ecosystem services is significant. Carbon storage correlates with AI, AREA_MN, and LPI, showing high-low and low-high clustering distributed in the central and northern regions. Different landscape indices show similar clustering with soil conservation, while water yield exhibits highly similar spatial distribution characteristics with various landscape indices. Habitat quality shows insignificant relationships with most areas of the study region. Based on the research findings, strategies are proposed to improve land resource allocation, enhance ecosystem services in nature reserves, strengthen comprehensive restoration and protection of wetlands, and implement regional integrated management of forests and grasslands to optimize landscape patterns and promote enhancement of ecosystem services.

Data availability

The required data and their sources are detailed in **Schedule 1** Due to confidentiality agreements, and other data are not publicly available due to the constraint in the consent.

References

Pan, K. L. et al. Research progress of agroforestry ecosystem service function. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 38 (12), 1535–1544 (2022).

Chen, H. P., Lee, M. & Chiueh, P. T. Creating ecosystem services assessment models incorporating land use impacts based on soil quality. Sci. Total Environ. 773, 145018 (2021).

Qian, Y. et al. Ecological risk assessment models for simulating impacts of land use and landscape pattern on ecosystem services. Sci. Total Environ. 833, 155218 (2022).

He, S. Y. & Zhang, L. Evaluation and tradeoff/synergy of ecosystem service function in Wangkuai reservoir basin based on invest model. Water Resour. Power. 40 (11), 60–63 (2022).

Huang, Y. W. & Zhang, X. P. Temporal and Spatial Changes of Ecosystem Service Value in National Key Ecological Functional Zones: A Case Study of Dayu County, Jiangxi Province . 43, 99–104 (Shanghai Land & Resources, 2022). 03.

McInnes, R. J. & Everard, M. Rapid assessment of wetland ecosystem services (RAWES): an example from Colombo, Sri Lanka. Ecosyst. Serv. 25, 89–105 (2017).

Spencer, C., Robertson, A. I. & Curtis, A. Development and testing of a rapid appraisal wetland condition index in south-eastern Australia. J. Environ. Manage. 54, 143–159 (1998).

Mooney, H. A., Duraiappah, A. & Larigauderie, A. Evolution of natural and social science interactions in global change research programs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 110 (Suppl 1), 3665–3672 (2013).

Schirpke, U., Tscholl, S. & Tasser, E. Spatio-temporal changes in ecosystem service values: effects of Land-Use changes from past to future (1860–2100). J. Environ. Manage. 272, 111068–111068 (2020).

Yohannes, H. et al. Impact of landscape pattern changes on hydrological ecosystem services in the Beressa watershed of the blue nile basin in Ethiopia. Sci. Total Environ. 793, 148559–148559 (2021).

Wang, Z. Q. et al. Research progress on evaluation of ecosystem service function of rice field in middle reaches of Yangtze river. J. Huazhong Agricultural Universit. 41 (06), 89–100 (2022).

Peng, J. et al. Promoting sustainable landscape pattern for landscape sustainability. Landscape Ecol. 36 (7), 1839–1844 (2021).

Wei, H. U. W., Xu, W. G. & Wei, D. Advance in research of the relationship between landscape patterns and ecological processes. Progress Geogr. 27 (1), 18–24 (2008).

Ma, S. et al. Distinguishing the relative contributions of climate and land use/cover changes to ecosystem services from a Geospatial perspective. Ecol. Ind., 136. (2022).

Du, S. X. et al. Assessment of ecosystem service function in water-conserving National key ecological functional areas. Acta Ecol. Sin. 42 (11), 4349–4361 (2022).

Boyd, J. & Banzhaf, S. What are ecosystem services? The need for standardized environmental accounting units. Ecol. Econ. 63 (2–3), 616–626 (2007).

Weiskopf, S. R. et al. A conceptual framework to integrate Biodiversity, ecosystem Function, and ecosystem service models. BioScience 72 (11), 1062–1073 (2022).

Li, Y. Y. et al. Landscape pattern and functional dynamic analysis of Medika wetland at the headwater of Lhasa river. Acta Ecol. Sin. 38 (24), 8700–8707 (2018).

Zang, Z. et al. Impact of landscape patterns on ecological vulnerability and ecosystem service values: an empirical analysis of Yancheng nature reserve in China. Ecol. Ind. 72, 142–152 (2017).

Ma, S. et al. Terrain gradient variations in ecosystem services of different vegetation types in mountainous regions: vegetation resource conservation and sustainable development. For. Ecol. Manag., 482. (2021).

Dong, J. Q. et al. Sustainable landscape pattern: a landscape approach to serving Spatial planning. Landscape Ecol. 37 (1), 31–42 (2022).

Fu, B. J. et al. The Global-DEP conceptual framework — research on dryland ecosystems to promote sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 48, 17–28 (2021).

Zhang, Y. R. et al. Study on the relationship between vegetation cover change and Climatic factors in ruoergai wetland in recent 20 years. Plateau Meteorol. 41 (02), 317–327 (2022).

Yu, K. & Hu, C. M. Changes in vegetative coverage of the Hongze lake National wetland nature reserve: a decade-long assessment using MODIS medium-resolution data. J. Appl. Remote Sens., 7 (1). (2013).

Peng, J. et al. Mapping spatial non-stationarity of human-natural factors associated with agricultural landscape multifunctionality in Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, China . 246, 221–233 (Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2017).

Xiao, J. S. et al. Land use change and evolution of ecosystem service value in Maduo County of source region of the yellow river. Acta Ecol. Sin. 40 (2), 510–521 (2020).

Li, G. M. et al. Changes and fractal characteristics of ruoergai wetland in recent 25 years. Geomatics Spat. Inform. Technol. 40 (07), 34–36 (2017).

Lin, T. et al. Urban Spatial expansion and its impacts on Island ecosystem services and landscape pattern: A case study of the Island City of Xiamen, Southeast China. Ocean. Coastal. Manage. 81, 90–96 (2013).

Maes, M. J. A. et al. Mapping synergies and trade-offs between urban ecosystems and the sustainable development goals. 93, 181–188 (Environmental Science & Policy, 2019).

Cao, Q. W. et al. Multi-scenario simulation of landscape ecological risk probability to facilitate different decision-making preferences. J. Clean. Prod. 227, 325–335 (2019).

Liu, Y. X. et al. Assessing landscape eco-risk associated with hilly construction land exploitation in the Southwest of china: Trade-off and adaptation. Ecol. Ind. 62, 289–297 (2016).

Xiao, J. J. et al. Spatial differentiation of ecosystem service importance in karst area of Yunnan-Guizhou plateau. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 42 (06), 332–342 (2022).

Chen, W. X. et al. Spatial heterogeneity and formation mechanism of ecoenvironmental effect of land use change in China. Geographical Res. 38 (9), 2173–2187 (2019).

Hao, R. F. et al. Impacts of changes in climate and landscape pattern on ecosystem services. Sci. Total Environ. 579, 718–728 (2017).

Chen, W. X., Chi, G. Q. & Li, J. F. The Spatial aspect of ecosystem services balance and its determinants. Land. Use Policy, 90. (2020).

Zhang, K. et al. Spatial optimisation based on ecosystem service spillover effect and cross-scale knowledge integration: A case study of the yellow river basin. J. Geog. Sci. 35 (5), 1080–1114 (2025).

Meng, Y. J. & Qin, P. Water quality evolution and its indicative effect on vegetation diversity in ruoergai wetland. J. Shandong Agricultural University(Natural Sci. Edition). 53 (02), 278–284 (2022).

Wang, W. B. et al. Distribution characteristics of soil organic carbon content and density in ruoergai wetland. Chin. J. Ecol. 40 (11), 3523–3530 (2021).

Dong, Z. L. & Zhang, T. S. General situation of ruoergai wetland resources and protection and utilization measures. J. Grassland Forage Sci., 2012 (07). 37–39.

Odgaard, M. V. et al. A multi-criteria, ecosystem-service value method used to assess catchment suitability for potential wetland reconstruction in Denmark. Ecol. Ind. 77, 151–165 (2017).

Fang, C. L. et al. Modeling regional sustainable development scenarios using the urbanization and Eco-environment coupler: case study of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration, China. Sci. Total Environ. 689, 820–830 (2019).

Wang, X., Blanchet, F. G. & Koper, N. Measuring habitat fragmentation: an evaluation of landscape pattern metrics. Methods Ecol. Evol. 5 (7), 634–646 (2014).

Nelson, E. et al. Modeling multiple ecosystem services, biodiversity conservation, commodity production, and tradeoffs at landscape scales. Front. Ecol. Environ. 7 (1), 4–11 (2009).

Hamel, P. et al. Mapping the benefits of nature in cities with the invest software. Npj Urban Sustain. 1 (1), 25 (2021).

Bouguerra, S. et al. Modeling ecosystem regulation services and performing Cost–Benefit analysis for climate change mitigation through Nature-Based solutions using invest models. Sustainability 16 (16), 7201 (2024).

Chen, A. et al. Study on ecosystem service changes, tradeoffs and synergies in the one river and two rivers basin of Tibet. Res. Soil. Water Conserv. 29 (02), 313–319 (2022).

Mu, W. B. et al. Evolution characteristics and influencing factors of potential evapotranspiration in ruoergai wetland. Plateau Meteorol. 38 (04), 716–724 (2019).

Veisi Nabikandi, B. et al. An integrated scenario-based approach for evaluating water yield responses to land use and climate change. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 28, 100919 (2025).

He, S. S. Study on soil and water loss in Qihe River Basin of Taihang Mountain Based on InVEST model (Henan University, 2019).

Dong, R. et al. Soil conservation function analysis of typical forest ecosystems based on the Chinese ecosystem research network. Acta Ecol. Sin. 40 (07), 2310–2320 (2020).

Qiu, J. et al. Land-use intensity mediates ecosystem service tradeoffs across regional social-ecological systems. Ecosyst. People. 17 (1), 264–278 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Distinguishing the impacts of rapid urbanization on ecosystem service trade-offs and synergies: a case study of shenzhen, China. Remote Sens. 14 (18), 4604 (2022).

Yang, Y., Zhang, J. & Hu, Y. Land use intensity alters ecosystem service supply and demand as well as their interaction: A Spatial zoning perspective. Sustainability 16 (16), 7224 (2024).

Wei, J. X. et al. The relationship between urban green landscape and ecosystem services in Chengdu. J. Northwest. Forestry Univ. 37 (06), 232–241 (2022).

Zhou, T. et al. Study on the Impact of Landscape Pattern on Ecosystem Services: A Case Study of Hanjiang River Ecological Economic Belt 32,152–165 (World Regional Studies, 2023). 08.

Chen, J. C. et al. Tradeoffs of multi-scale ecosystem services and their responses to landscape allocation: a case study of Hubei Province. Acta Ecol. Sin. 43 (12), 4835–4846 (2023).

Liu, Y. X., Ren, Z. Y. & Li, C. Y. Response of ecological service value to landscape pattern evolution in Qinling mountains: A case study of Shangluo City. J. Arid Land. Resour. Environ. 27 (03), 109–114 (2013).

Wang, F. et al. Effects of landscape pattern changes on water ecosystem services in rapidly urbanized areas. J. Soil Water Conserv. 37 (01), 159–167 (2023).

Su, S. L. et al. Characterizing landscape pattern and ecosystem service value changes for urbanization impacts at an eco-regional scale. Appl. Geogr. 34, 295–305 (2012).

Yushanjiang, A. et al. Quantifying the Spatial correlations between landscape pattern and ecosystem service value: A case study in ebinur lake Basin, Xinjiang, China. Ecol. Eng. 113, 94–104 (2018).

Ma, G. Q. et al. Spatial and Temporal evolution of landscape pattern and its response to ecosystem service value in Qilu lake basin from 1990 to 2018. J. West. China Forestry Sci. 52 (01), 34–42 (2023).

Liu, H. J. et al. Construction of ecological space network of ecological barrier belt in loess plateau based on importance, sensitivity and landscape characteristics. Bull. Soil. Water Conservatio. 42 (03), 103–111 (2022).

Luo, J. et al. Effects of landscape structure changes on ecosystem services in Hunshandake sandy land. J. Desert Res. 42 (04), 99–109 (2022).

Zheng, K. L. & Deng, D. Z. Soil infiltration performance and its influencing factors in ruoergai wetland. Res. Soil. Water Conserv. 26 (03), 179–184 (2019).

Sun, R. Q. et al. Hydrogen and oxygen isotopes and hydrochemical characteristics of water in ruoergai wetland National nature Reserve, Sichuan Province. J. Nanjing Forestry University(Natural Sci. Edition). 46 (02), 169–178 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, W.C. and Y.W.; methodology, Y.C.; software, Y.M.; validation, Q.L. and S.L.; formal analysis, Y.M.; investigation, W.C. and J.P.; data curation, W.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.M.; visualization, Y.M.; supervision, W.C. and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, J., Chen, W., Cai, Y. et al. Effects of landscape pattern changes on ecosystem services: a case study of Ruoergai Plateau. Sci Rep 15, 45753 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28635-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28635-w