Abstract

Biological sex affects cardiac tolerance to ischemia and reperfusion, but little is known about sex differences in heart transplantation with donation after circulatory death (DCD). Using a rat model, we characterized differences between sexes both in the donor, during simulated DCD, and in the procured heart, to evaluate recovery upon reperfusion. Adult male, female and ovariectomized Wistar rats underwent simulated DCD with 22 min of warm, in-situ ischemia. Hearts were then explanted and maintained in cold static storage for 30 min. Isolated hearts then underwent normothermic, oxygenated reperfusion for 60 min with left ventricular loading. In-situ characteristics, as well as ventricular function, coronary flows and metabolic post-ischemic recovery were assessed. Post-ischemic ventricular recovery was significantly higher in female compared to male and ovariectomized hearts. Furthermore, several in-situ circulating factors, including free fatty acids and potassium, were significantly lower in females compared with males. Greater post-ischemic ventricular function in female vs. male and ovariectomized hearts following DCD indicates that sex affects tolerance to DCD conditions and that female sex hormones contribute to cardioprotection. Greater understanding of sex-specific tolerance to DCD conditions may serve as a basis to better define precise mechanisms of cardiac injury and thereby contribute to optimizing clinical protocols.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heart donation after circulatory death (DCD) is used to overcome organ shortage, holding the potential to increase transplantation activity by 26–48%1,2, and provides recipient outcomes comparable to conventional brain-death donations3,4,5.

Despite the excellent clinical results with DCD in heart transplantation, room for optimization of clinical protocols remains6,7,8. Maastricht Type III donors are typical in DCD heart transplantation and, after withdrawal of life sustaining therapy, hearts are subjected to potentially damaging conditions, including hypoxia. In porcine models of DCD, increases in circulating lactate and potassium (K+) and a catecholamine surge have been reportef9,10,11. These conditions in the DCD donor, including a period of warm cardiac ischemia, lead to profound changes in cardiac metabolism and may influence graft quality12.

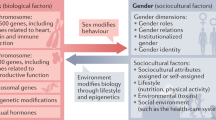

It is recognized that sex differences in cardiac ischemic resilience and metabolism exist. A recent report demonstrated the influence of sex on global myocardial ischemia tolerance and mitochondrial function in a rat model of circulatory death13. In fact, DCD hearts from female rats present relatively less damaged interfibrillar mitochondria13, recognized as the primary source of energy to the contractile apparatus14,15. Furthermore, it was shown that mitochondria from female hearts produce less reactive oxygen species compared to mitochondria from males, thereby contributing to improved mitochondrial calcium retention capacity13. Following myocardial infarction, reproductive-age female rats demonstrated smaller infarct sizes and higher ventricular function than age-matched males16, in line with higher ischemic tolerance in reproductive-age females compared to males16.

Female sex hormones play a key role in the improved ischemic tolerance of female hearts. Indeed, estrogen can provide cardioprotection by preserving the vasculature, improving excitation-contraction coupling and inhibiting mitochondrial death17. Correspondingly, in mouse models of ischemia/reperfusion injury, the administration of estrogen to males partially salvaged cardiac recovery, while ovariectomy in females led to worse cardiac recovery16. Less is known about the effects of progesterone in cardiac ischemic tolerance; however, its administration to female rats improved the recovery in terms of infarct size, oxidative stress, inflammation and arrhythmias, whereas it did not change recovery in hearts from males or ovariectomized (OVX) rats18.

In the context of conventional heart transplantation after brain death, female donor hearts were considered less favorable, especially when transplanted into male recipients, primarily due to presumed sex mismatch19,20. However, recent studies, including in DCD heart transplantation, have shown that sex mismatch per se does not impair graft recovery or survival21,22. Instead, worse outcomes are mainly explained by donor-recipient size mismatch21,22. When size matching is achieved, graft recovery and survival are comparable regardless of donor or recipient sex21,22. Overall, females are underrepresented in clinical studies and a better understanding of sex-dependent differences should permit optimization of clinical protocols and application of precision therapies at graft procurement, during ex-situ heart perfusion and potentially post-transplantation23.

Therefore, we aimed to investigate sex differences cardiac graft recovery following simulated DCD with a period of in-situ ischemia, measured as ventricular and metabolic function, as well as coronary flow profiles, using a rat model of DCD. Furthermore, we characterized the pathophysiological changes that occur in the donor and may affect the cardiac recovery after warm, in-situ ischemia and reperfusion in this model. To investigate the role of both sex and female sex hormones, male, female and OVX rats were included in the study.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 20 rats (6 males, 7 females and 7 OVX) were included in this study (exclusive of additional rats used for estrus stage evaluation). Sample size and baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Body weight, heart weight and systolic arterial pressure were lower in female and OVX rats than in males (body weight: both p < 0.001; heart weight: females p < 0.001, OVX p = 0.002; systolic pressure: females p = 0.009, OVX p < 0.001). In addition, female body weight was lower compared to OVX (p < 0.001). Heart rate was similar among groups. Progesterone and estradiol levels in the rats were significantly higher in females compared to both males and OVX (p < 0.001 for all).

Improved myocardial recovery in females

Post-ischemic myocardial recovery is presented in Fig. 1. Left ventricular (LV) work (Fig. 1a), maximum contraction rate (Fig. 1b) and maximum relaxation rate (Fig. 1c) were significantly greater in females compared to males and OVX (p < 0.001 for all). Cardiac output (Fig. 1d) was similar among groups.

Release of the cell death markers troponin I, heart-type fatty acid binding protein (H-FABP) and myoglobin was similar among groups (Figure S1); however, H-FABP (Fig. 1e, p = 0.035, Spearman’s rho = − 0.579) and myoglobin (Fig. 1f, p = 0.023, Spearman’s rho = − 0.632) showed negative correlations with cardiac output.

Ventricular function and markers of cell death during reperfusion with ex-situ heart perfusion. (a) Left ventricular work reported as mean ± SD, (b) maximum contraction rate reported as mean ± SD, (c) maximum relaxation rate reported as mean ± SD, (d) cardiac output reported as mean ± SD, (e) correlation between the release of heart-type fatty acid binding protein over 60 min of reperfusion with cardiac output, p = 0.035, Spearman’s rho = − 0.579, (f) correlation between the release of myoglobin over 60 min of reperfusion with cardiac output. p = 0.023, Spearman’s rho = − 0.632, *p < 0.001 females vs. males, $ p < 0.001 females vs. OVX. Symbols indicate statistical significance based on linear regression analysis over 20 to 60 min reperfusion. CO: cardiac output; dP/dtmax: maximum first derivative of left ventricular pressure; dP/dtmin: minimum first derivative of left ventricular pressure; HW: heart weight; H-FABP: heart-type fatty acid binding protein; n = 5–7/group.

Active hyperemia is higher in males

Coronary flows were evaluated as reactive hyperemia (coronary flow during the first minutes of aerobic reperfusion) or active hyperemia (change in coronary flow with increasing cardiac workload triggered by switching from unloaded to loaded perfusion modes). Reactive hyperemia (Fig. 2a) was not different between sexes, whereas active hyperemia (Fig. 2b) was significantly lower in females and OVX compared to males (p = 0.034, p = 0.033; respectively). No difference among experimental groups was observed for coronary flows (Fig. 2c) or tissue edema after 60 min reperfusion (Fig. 2d).

Coronary flow and edema during reperfusion with ex-situ heart perfusion. (a) Reactive hyperemia measured as the mean coronary flow during early unloaded reperfusion (3 min, 5 min and 10 min of reperfusion), (b) active hyperemia measured as increase in coronary flow between unloaded and loaded conditions, *p = 0.034 females vs. males, * p = 0.033 OVX vs. males, (c) coronary flow during loaded mode reported as mean ± SD, (d) edema formation. CF: coronary flow normalized by heart weight, n = 6–7/group.

Improved oxygen efficiency in females

Oxygen consumption was greater in males and females compared to OVX hearts (Fig. 3a; p = 0.002 for males, p = 0.043 for females). Oxygen efficiency was significantly higher in female hearts compared to male hearts (Fig. 3b, p = 0.002). Release of cytochrome c (Fig. 3c), an indicator of mitochondrial damage, release of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (Fig. 3d), an indicator of oxidative stress, and calcium content in cardiac tissue after reperfusion (Fig. 3e) were not different between groups. In addition, the net increase in perfusate lactate (Fig. 3f) was significantly lower in females than in OVX (p = 0.009).

Metabolic recovery and oxidative stress. (a) Oxygen consumption during the loaded reperfusion reported as mean ± SD, $ p = 0.043 females vs. OVX, $ p = 0.002 males vs. OVX, (b) oxygen efficiency (calculated as the quotient of LV work and oxygen consumption) reported as mean ± SD, * p = 0.002 females vs. males, (c) cytochrome c release over 60 min of reperfusion, (d) oxidative stress over 60 min of reperfusion, (e) calcium content in cardiac tissue after 60 min of reperfusion, (f) net increase in lactate over 60 min of reperfusion, $ p = 0.009 females vs. OVX, symbols on panels (a) and (b) indicate statistical significance based on linear regression analysis over 20 to 60min reperfusion. 8-oxo-dG: 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine, n = 6–7/group.

Estrus cycle stage correlates with myocardial recovery

The females were classified for estrus cycle stage according to vaginal swab findings (Figure S2). Although we have a small number of female rats in each stage, the females in estrus seemed to present the lowest ventricular function (Figure S3). In addition, estrus cycle stage correlated with cardiac output (Figure S3e, p = 0.017, Spearman’s rho = − 0.766) and oxygen efficiency (Figure S3f; p = 0.036, Spearman’s rho = − 0.715).

Sex differences in-situ

Overall, the progression of biochemical changes after the start of functional warm ischemic time (FWIT) in all groups followed a pattern similar to that previously reported in male rat models24 and in porcine models9,10,11 (Fig. 4). Blood glucose concentration (Fig. 4e), circulating free fatty acids (FFA, Fig. 4f) and blood potassium concentration (Fig. 4g) were significantly lower in females compared to males at baseline (p = 0.014, p < 0.001, p = 0.022; respectively) and FWIT (p = 0.002, p = 0.002; p = 0.032; respectively). Blood glucose and potassium were also significantly lower in females compared to OVX at baseline (p = 0.008, p = 0.003; respectively). Blood glucose concentration and FFA were significantly lower in OVX compared to males at FWIT (p = 0.049, p < 0.001; respectively) and FFA were also significantly lower in OVX compared to males at baseline (p < 0.001). Blood calcium concentration (Fig. 4h) was elevated at end-ischemia, but was not significantly different among experimental groups. It was significantly lower in female and OVX hearts at baseline and FWIT compared with end-ischemia (p < 0.001 for OVX and females at baseline, p = 0.036 for females at FWIT). Adrenalin levels (Fig. 4i) were not different between sexes; however, noradrenalin levels (Fig. 4j) were increased in females and OVX compared to males at end-ischemia (p = 0.023, p = 0.025; respectively).

In-situ blood measurements during the DCD protocol at baseline (BL), start of functional warm ischemia (FWIT) and at the end of ischemia (EI). (a) partial pressure of oxygen, Φ p < 0.001 vs. respective baseline, (b) partial pressure of carbon dioxide, Δ p < 0.001 vs. respective end ischemia, $ p = 0.025 females vs. OVX at baseline, * p = 0.011 OVX vs. males at baseline, (c) pH, Δ p < 0.001 vs. respective end ischemia, $ p = 0.041 females vs. OVX at baseline, * p < 0.001 OVX vs. males at baseline, $ p = 0.007 females vs. OVX at FWIT, * p = 0.036 OVX vs. males at FWIT, (d) lactate concentration, Δ p < 0.001 vs. respective end ischemia, (e) glucose concentration, Δ p < 0.001 vs. respective end ischemia, * p = 0.014 females vs. males at baseline, $ p = 0.008 females vs. OVX at baseline, * p = 0.002 females vs. males at FWIT, * p = 0.049 OVX vs. males at FWIT, (f) free fatty acid concentration, Δ p < 0.001 vs. respective end ischemia, * p < 0.001 females vs. males at baseline, * p < 0.001 OVX vs. males at baseline, * p = 0.002 females vs. males at FWIT, * p < 0.001 OVX vs. males at FWIT. (g) potassium concentration, Δ p < 0.001 vs. respective end ischemia, * p = 0.022 females vs. males at baseline, $ p = 0.003 females vs. OVX at baseline, * p = 0.032 females vs. males at FWIT, * p = 0.042 OVX vs. males at end ischemia. (h) calcium concentration, Δ p < 0.001 vs. respective end ischemia for OVX and females at baseline, Δ p = 0.036 for females at FWIT, (i) adrenalin concentration, Δ p < 0.001 vs. respective end ischemia, (j) noradrenalin concentration, Δ p < 0.001 vs. respective end ischemia, * p = 0.023 females vs. males at end ischemia, * p = 0.025 OVX vs. males at end ischemia, BL: baseline; FWIT: functional warm ischemic time; EI: end ischemia; n = 6–7/group.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to investigate sex differences in post-ischemic recovery of ventricular and metabolic function, as well as coronary flow profiles and to characterize the corresponding pathophysiological changes in the DCD donor that may affect cardiac graft quality. To investigate the role of female sex hormones, males, females and OVX rats were included. We report improved myocardial recovery in hearts from reproductive-age female rats compared with hearts from male and OVX rats, after simulation of DCD with in-situ warm ischemia, indicating a cardioprotective role for female sex hormones. Furthermore, metabolic recovery, determined by oxygen efficiency, was greater in females compared with males, supporting the concept of improved preservation of mitochondrial function. We also characterized sex-specific differences in-situ during simulation of the DCD protocol. In general, high, stable calcium levels in males with higher circulating FFA, glucose, and potassium in males versus females, may all contribute to the decreased myocardial recovery in male versus female hearts. Although the present model does not simulate extended-criteria donors, it provides valuable mechanistic insight into sex-related differences in the myocardial response to ischemia and reperfusion after circulatory death. These findings contribute to our understanding and shed light on potential mechanisms underlying sex differences in cardiac graft recovery following simulated DCD. These findings should also help with the advancement of precision medicine approaches towards optimizing current clinical protocols, especially with respect to therapies that could be applied during ex-vivo perfusion and post-transplantation These approaches are relevant not only for heart transplantation, but also for other DCD organs/ transplantation approaches.

We report that, during reperfusion, recovery of ventricular function was increased in reproductive-age females compared to males and OVX rats. The inclusion of OVX rats permits investigation of the influence of female sex hormones on myocardial recovery, which is of particular relevance as female sex hormones are reported to be cardioprotective16 and may help to preserve ventricular function in the context of DCD heart transplantation. In parallel with improved ventricular function, we also report significantly improved oxygen efficiency in female hearts compared to males. Improved oxygen efficiency in females compared to males is consistent with improved mitochondrial function. In line with our study, Chen et al. showed that myocardial recovery is higher in female compared to male rats following a DCD protocol and reported less damage in interfibrillar mitochondria from female compared with male DCD hearts13. Relatively less damaged interfibrillar mitochondria would be expected to improve energy supply in female DCD hearts during reperfusion which, in turn, should contribute to a better recovery of ventricular function in females compared with males after ischemia13. Previous studies also reported that post-ischemic recovery of isolated working hearts from female rats was lower compared to males when hearts were perfused with a solution containing glucose and fatty acids, a composition similar to what we used25,26. However, these studies were not performed in the context of DCD heart transplantation. Overall, we report higher post-ischemic cardiac and mitochondrial function in females compared to males and OVX, indicating metabolic differences between the groups, potentially mediated by sex hormones.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to study sex differences in coronary flows in DCD hearts. We did not see differences in reactive hyperemia. Given that reactive hyperemia is largely driven by rapid vasodilators such as nitric oxide (NO) and adenosine27,28 in response to ischemia29, comparable responses in males, females and OVX imply that neither sex, nor sex hormones, significantly enhance or impair this type of flow response under these experimental conditions. On the other hand, we demonstrate that, while female and OVX rats exhibited similar active hyperemia, male rats demonstrated a greater active hyperemia, in line with a previous report in humans30. The significantly elevated active hyperemia in males suggests a sex-dependent difference in vascular adaptation. Testosterone is reported to be a vasodilatory hormone31 and potentially mediates the increased hyperemic response observed in male rats compared to female and OVX. Similar rates of coronary flow per gram of tissue were generally measured across all groups throughout the reperfusion period, indicating similar rates of oxygen delivery. As oxygen efficiency was significantly higher in female vs. male hearts, which corresponds with a previous report of higher mitochondrial function in females13, these findings suggest that male hearts are less effective in adapting to meet the energy requirements under post-DCD loaded conditions compared to female hearts.

To our knowledge, we are the first to investigate sex differences in circulating FFA levels. Already at baseline, FFA concentrations were high in males and females compared to physiologic values32. We have previously reported that FFA levels increase in males in both rat24 and in pig models33 of DCD. Increases in circulating FFA are recognized under other conditions of acute myocardial ischemia, and are elevated in response to both heparin34 and increased circulating catecholamines35. It has been shown that females are less sensitive to lipolytic stimulation36 and our results of a limited increase in FFA in female and OVX rats compared with male rats support this concept. Lastly, in our study, catecholamines are low at BL and FWIT, which is an indication that the high FFA levels in our rats were initially due to heparin administration and not the catecholamine surge. Heparin is crucial in our model to prevent coagulation in the donor following circulatory arrest. Interestingly, we observed that ovariectomized animals did not always resemble males, as would be expected if ovarian hormones were the sole determinant of the observed differences. For example, noradrenaline levels did not follow this pattern. This suggests that additional mechanisms may be involved beyond circulating female sex hormones. It should be noted that ovariectomized rats remain biologically female, and sex-specific factors such as chromosomal influences, epigenetic regulation, or intrinsic differences in autonomic control and receptor expression may contribute to these findings. Therefore, our results highlight the importance of distinguishing between the effects of circulating sex hormones and those of biological sex per se, both of which may influence cardiac responses in the setting of ischemia–reperfusion injury.

Hormonal fluctuations in the estrus cycle have long been considered responsible for variability in female rat models. However, over the past 10 years, studies have begun to challenge this hypothesis. For example, similar to our study, a meta-analysis of 293 publications found no difference in variability between male and female rats37,38. Furthermore, variability between male and female rats across physiological phenotypes related to the heart, lungs, blood vessels, blood, and kidneys was not different39. However, it is important to note that some studies have reported estrous-cycle-specific effects on certain behaviors40. In fact, Ramíres-Hernàndez et al. have shown that infarct size is increased for rats in estrus stage after myocardial infarction41. Our study aligns with these findings, as estrus appears to correspond with lower recovery of ventricular function and estrus stage significantly correlates with myocardial recovery, despite a small number of females in each stage.

In the clinical setting, it has been described that cardiac grafts from females are often unfavorable, especially when implanted in male recipients19,20. However, in our study using a DCD protocol, we showed that female hearts retain higher ventricular function than males following DCD simulation, and OVX rats recovered similarly to the males. It has been shown that estrogen inhibits the opening of connexin43 in the mitochondria, and thereby preserves mitochondrial function after ischemia42. It has also been demonstrated that, if estrogen was given to male rats during reperfusion, LV function was increased and infarct size was decreased following ischemia42. Estrogen in female rats might be a key player in the observed improved recovery, as estrogen is reported to activate multiple salvaging pathways in the ischemia/reperfusion setting, such as ERK or MAPK which lead to increased mitochondrial gene expression and biogenesis, higher respiration rates and ATP production and the production of antioxidant enzymes. Furthermore, estrogen can also lead to a decrease in mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, cytochrome c release, reactive oxygen species production, calcium accumulation43 and an improved mitochondrial quality control44,45,46,47. In addition, progesterone receptors can act as transcription factors or activate PKC, Akt or MAPK pathways to stimulate cell survival or proliferation48. On the other hand, testosterone is recognized to decrease cardiac function49 which might be a relevant mechanism for the observed functional decrease observed in males compared to females and OVX.

This study possesses some limitations. One limitation is that, due to the small blood volume in rats, the hearts were not perfused with blood but with a crystalloid solution. This condition may not fully replicate the clinical situation, thereby limiting the direct translatability of our findings to human transplantation. With the model used, only short-term myocardial recovery was assessed, transplantation studies with longer term recovery are now warranted. The model used is a controlled DCD donor model without prior brain injury. While this approach does not mimic extended-criteria or clinically marginal donors, it was chosen to minimize biological variability and to ensure reproducible ischemia-reperfusion conditions. The reperfusion period was not designed to reproduce the entire clinical setting (e.g., ex-vivo perfusion using Organ Care System technology), but to allow precise control of reperfusion conditions. This strategy enabled the investigation of intrinsic sex-related differences in tolerance to DCD-induced conditions including a clinically relevant period of in-situ ischemia, while limiting variability and the number of animals required, in accordance with 3R principles. Future studies including aged or comorbid donors and clinically relevant graft preservation approaches will be essential to translate these findings to the clinical context. In order to investigate the influence of sex hormones on myocardial recovery, OVX rats were included with age-matched males and females; however, it is important to acknowledge that sex differences are not solely driven by circulating sex hormones.

In conclusion, we have investigated sex-specific differences in post-ischemic ventricular function, coronary flows and metabolism, and have characterized in-situ pathophysiologic changes in the donor using a rat model of DCD. The post-DCD recovery of myocardial function was higher in hearts from females compared to males and OVX. As OVX rats showed a pattern of ventricular function recovery that was more similar to males than females, our findings support the concept that female sex hormones contribute to improved tolerance to ischemia/reperfusion injury in the context of DCD heart transplantation. Importantly, we also demonstrate greater post-DCD oxygen efficiency in females vs. males, consistent with a previous report of better preserved mitochondrial function in female hearts. Furthermore, pathophysiological changes in the donor, that are present even before heart procurement in the context of DCD - such as elevated circulating FFA, glucose and potassium, as well as a tendency for increased calcium levels in males vs. females - may contribute to the reduced myocardial recovery subsequently observed following reperfusion and ventricular loading. In addition to helping identify precision cardiac therapies to be applied during ex-situ heart perfusion or post-transplantation that could optimize clinical DCD protocols, this study also describes a rat model of DCD and provides a basis for future studies that further investigate sex as a biological variable in DCD transplantation.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All experiments were reviewed and approved by the Swiss animal welfare authorities and the ethics committee for Animal Experimentation, Bern, Switzerland (BE13/2022). All procedures involving animals were performed in accordance with relevant national guidelines and institutional regulations for animal welfare, and are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Animals

Male, female and OVX Wistar rats (Janvier Labs, Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France) were housed in groups with a 12 h light-dark cycle at a controlled room temperature and with unlimited access to food and water. Rats underwent ovariectomy or sham surgery at approximately 6 weeks of age and were used for experiments at 10 to 11 weeks of age, representing young-adult human DCD heart donors with a mature cardiac metabolism50,51.

Experimental protocol

Rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (78 mg/kg for males; 65 mg/kg for females and OVX; Narkatan, Vetoquinol AG, Bern, Switzerland), acepromazine (1.2 mg/kg for males; 1.0 mg/kg for females and OVX; Prequillan, Bologna, Italy) and xylazine (7.2 mg/kg for males; 6.0 mg/kg for females and OVX; Xylapan, Vetoquinol AG, Bern, Switzerland). Simulation of DCD was performed as previously reported24 and is represented in Fig. 5. Briefly, following loss of the pedal withdrawal reflex, the right carotid artery was cannulated to monitor blood pressure and 320U of heparin were injected in order to avoid blood coagulation. Withdrawal of life sustaining therapy was simulated by transecting the diaphragm. FWIT was considered to start when the systolic arterial pressure reached 50mmHg. Circulatory arrest was declared when the pulse pressure was 3mmHg. Temperature was monitored during the entire protocol and rats were maintained at 37 °C with a heat lamp. Once 22 min of ischemia had elapsed, hearts were quickly explanted, mounted on an ex-situ perfusion system and flushed with a cold preservation solution (St. Thomas II cardioplegia supplemented with glyceryl trinitrate and erythropoietin) for 3 min at a constant pressure of 60 mmHg. No fixed volume was predetermined; the total perfusate volume ranged from 16.5 mL to 28 mL, depending on the pressure-driven flow during this period. The cardioplegia flush was followed by 27 min of cold static storage at 4 °C. 22 min of in-situ, warm ischemia52 was chosen based on a previous study to generate an intermediate myocardial recovery and 30 min of cold ischemia3,4 was chosen to simulate the time needed in a clinical setting to prepare the heart for perfusion. Isolated hearts were then aerobically perfused and warmed to 30 °C for 1 min in a non-recirculating unloaded mode and 9 min in a recirculating unloaded mode at 37 °C. LV loading was then performed for 50 min. Hearts were perfused with modified Krebs-Henseleit buffer supplemented with 0,45 mM bovine serum albumin, 0.5 mM lactate and 0.4 mM palmitate. Preload (left atrial) pressure was set to 11.5 mmHg and afterload (aortic) pressure was set to 60 mmHg.

In-situ blood samples were taken after cannulation of the carotid artery (baseline), at the start of FWIT and after explanting the heart (end-ischemia). Preload and coronary effluent perfusate samples were taken at 0, 10, 20, 40 and 60 min of ex-situ perfusion. After 60 min reperfusion, hearts were snap frozen and stored at − 80 °C for further analysis.

Myocardial recovery evaluation

LV pressure was measured using a micro-tip pressure catheter (Millar; Houston, USA) placed via the mitral valve. Perfusate flow was measured using flow probes (Transonic Systems Inc.; Ithaca, USA) placed in pre- and after- load lines. Cardiac output and coronary flow were normalized by heart weight. Reactive hyperemia was measured as the mean absolute value of coronary flow normalized by heart weight during early unloaded reperfusion (1, 3 and 5 min of reperfusion). Active hyperemia was measured as the difference in absolute values of coronary flow normalized by heart weight between unloaded and loaded conditions (respectively 10 and 40 min of reperfusion). Data were continuously recorded using a PowerLab data acquisition system and analyzed with LabChart 7 software (ADInstruments; Oxford, UK).

Blood gas analysis (in-situ blood and perfusate samples)

Partial oxygen and carbon dioxide pressure, electrolytes, pH, glucose and lactate were measured using a Cobas b 123 blood gas analyzer (Roche; Basel, Switzerland). For glucose measurements, values that exceeded the 30 mM maximal measurement threshold were set to 30 mM for analysis.

Biochemical measurements

Biochemical measurements are described in Supplemental Material.

Estrus cycle determination

The estrus cycle was determined by vaginal lavage, the detailed methods are described in Supplementary Material. An additional series of female rats that underwent the same experimental protocol was included in order to increase the number of female rats for the determination of estrus cycle and investigation of its effects on myocardial recovery.

Statistics

All results are expressed as median and interquartile range. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism version 9 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). To limit variability, we applied a predefined set of exclusion criteria (technical issues, coronary flow cut-off above 13 mL/min/g, warm ischemic temperature cut-offs below 35 °C or above 37 °C, and cannulation time exceeding 2 min). The Tukey test was used to identify outliers, which were then removed from the study. For variables with repeated measures, a linear regression analysis was used to evaluate differences between groups. One-way ANOVAs were to determine differences among variables measured at one timepoint only, while two-way ANOVAs were used to determine differences among sex groups for variables measured at different timepoints in-situ. Following ANOVA tests, a Fishers Least Significant Difference test was used to determine differences between experimental groups. Correlations were analyzed using the Spearman’s rank correlation test.

To control for type I error, all reported p-values were subsequently adjusted for multiple comparisons using a modified Bonferroni procedure53. Corrected p-values were reported, and statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

Experimental protocol. Anesthetized males, females and ovariectomized females underwent circulatory arrest and 22 min of functional warm ischemia. Afterwards, hearts were procured and mounted on an ex-situ heart perfusion system, flushed for 3 min with a cold preservation solution and stored for another 27 min at 4 °C. Hearts were then perfused for 10 min in the unloaded mode, followed by 50 min with left ventricular loading. In-situ blood samples (red arrows) were taken after cannulation of the carotid artery (baseline-BL), at start of functional warm ischemia time (FWIT) and after excising the heart (end ischemia-EI). Perfusate samples (blue arrows) were taken at 0, 10, 20, 40 and 60 min of ex-situ perfusion. Coronary flow, ventricular and metabolic recovery (orange arrow) were evaluated throughout the loaded perfusion. BL: baseline; FWIT: functional warm ischemic time; EI: end ischemia; SAP: systolic arterial pressure; PP: pulse pressure.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DCD:

-

Donation after circulatory death

- FFA:

-

Free fatty acids

- FWIT:

-

Functional warm ischemic time

- H-FABP:

-

Heart-type fatty acid binding protein

- LV:

-

Left ventricular

- OVX:

-

Ovariectomized rats

References

Joshi, Y. et al. Donation after circulatory death: A new frontier. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 24(12), 1973–1981. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-022-01798-y (2022).

Messer, S. et al. A 5-year single-center early experience of heart transplantation from donation after circulatory-determined death donors. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 39(12), 1463–1475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2020.10.001 (2020).

Dhital, K., Ludhani, P., Scheuer, S., Connellan, M. & Macdonald, P. DCD donations and outcomes of heart transplantation: The Australian experience. Indian J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 36(S2), 224–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12055-020-00998-x (2020).

Chew, H. C. et al. Outcomes of donation after circulatory death heart transplantation in Australia. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73(12), 1447–1459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.067 (2019).

Schroder, J. N. et al. Transplantation outcomes with donor hearts after circulatory death. N Engl. J. Med. 388(23), 2121–2131. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2212438 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Warm-ischemia and cold storage induced modulation of ferroptosis observed in human hearts donated after circulatory death and brain death. Am. J. Physiol-Heart Circ. Physiol. 328(4), H923–H936. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00806.2024 (2025).

Kwon, Y. I. C. et al. Early outcomes of primary graft dysfunction comparing donation after circulatory and brain death heart transplantation: An analysis of the UNOS registry. Clin. Transpl. 39(7), e70222. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.70222 (2025).

Cho, P. D. et al. Severe primary graft dysfunction in heart transplant recipients using donor hearts after circulatory death: United States experience. J. Heart Lung Transpl. Off Publ Int. Soc. Heart Transpl. 44(5), 760–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2024.11.027 (2025).

Iyer, A. et al. Pathophysiological trends during withdrawal of life support: implications for organ donation after circulatory death. Transplantation 100(12), 2621–2629. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000001396 (2016).

White, C. W. et al. Physiologic changes in the heart following cessation of mechanical ventilation in a porcine model of donation after circulatory death: Implications for cardiac transplantation. Am. J. Transpl. 16(3), 783–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.13543 (2016).

Hubacher, V. et al. Open- vs. closed-chest pig models of donation after circulatory death. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1325160. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1325160 (2024).

Arnold, M. et al. Metabolic considerations in direct procurement and perfusion protocols with DCD heart transplantation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (8), 4153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25084153 (2024).

Chen, Q., Akande, O., Lesnefsky, E. J. & Quader, M. Influence of sex on global myocardial ischemia tolerance and mitochondrial function in circulatory death donor hearts. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 324 (1), H57–H66. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00478.2022 (2023).

Lesnefsky, E. J., Chen, Q. & Hoppel, C. L. Mitochondrial metabolism in aging heart. Circ. Res. 118(10), 1593–1611. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307505 (2016).

Lesnefsky, E. J., Chen, Q., Tandler, B. & Hoppel, C. L. Mitochondrial dysfunction and myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion: Implications for novel therapies. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 57, 535–565. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010715-103335 (2017).

Ostadal, B. & Ostadal, P. Sex-based differences in cardiac ischaemic injury and protection: Therapeutic implications. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171(3), 541–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.12270 (2014).

Murphy, E. & Steenbergen, C. Gender-based differences in mechanisms of protection in myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 75 (3), 478–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.025 (2007).

Dhote, V. V. & Balaraman, R. Gender specific effect of progesterone on myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Life Sci. 81(3), 188–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2007.05.010 (2007).

Khush, K. K., Kubo, J. T. & Desai, M. Influence of donor and recipient sex mismatch on heart transplant outcomes: Analysis of the international society for heart and lung transplantation registry. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 31(5), 459–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2012.02.005 (2012).

Peled, Y. et al. The impact of gender mismatching on early and late outcomes following heart transplantation. ESC Heart Fail. 4(1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.12107 (2017).

Rajesh, K. et al. Impact of donor and recipient sex-mismatch in donation after circulatory death heart transplant. Clin. Transpl. 39(9), e70285. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.70285 (2025).

Doulamis, I. P. et al. Sex mismatch following heart transplantation in the United States: Characteristics and impact on outcomes. Clin. Transpl. 36(12), e14804. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.14804 (2022).

Ayesta, A. et al. The role of sex in heart failure and transplantation, II. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1141032. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1141032 (2023).

Arnold, M. et al. Comparison of experimental rat models in donation after circulatory death (DCD): In-situ vs. ex-situ ischemia. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 7, 596883. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2020.596883 (2021).

Glick, B., Nguyen, Q. & Broderick, T. L. Depression in mechanical function following ischemia in the female rat heart: Role of fatty acids and altered mitochondrial respiration. J. Gend-Specif Med. JGSM Off J. Partnersh. Womens Health Columbia. 6(2), 22–26 (2003).

Saeedi, R. et al. Gender and post-ischemic recovery of hypertrophied rat hearts. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 6, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-6-8 (2006).

Ralevic, V. & Burnstock, G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol. Rev. 50(3), 413–492 (1998).

Guieu, R. et al. Adenosine and the cardiovascular system: the good and the bad. J. Clin. Med. 9 (5), 1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9051366 (2020).

Joyner, M. J. & Dietz, N. M. Nitric oxide and vasodilation in human limbs. J. Appl. Physiol. Bethesda Md. 1985. 83(6), 1785–1796. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1997.83.6.1785 (1997).

Hunter, S. K. et al. Active hyperemia and vascular conductance differ between men and women for an isometric fatiguing contraction. J. Appl. Physiol. 101 (1), 140–150. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01567.2005 (2006).

Kelly, D. M. & Jones, T. H. Testosterone: a vascular hormone in health and disease. 1 https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-12-0582 (2013).

Kalderon, B., Mayorek, N., Berry, E., Zevit, N. & Bar-Tana, J. Fatty acid cycling in the fasting rat. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 279(1), E221–E227. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.1.E221 (2000).

Graf, S. et al. Circulating factors, in both donor and ex-situ heart perfusion, correlate with heart recovery in a pig model of DCD. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 44(1), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2024.08.016 (2025).

Grossman, M. I. et al. Moeller effect of lipemia and heparin on free fatty acid content of rat plasma. Accessed December 11, 2023. (1954). https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.3181/00379727-87-21366?icid=int.sj-abstract.similar-articles.2.

Reilly, S. M. et al. Catecholamines suppress fatty acid re-esterification and increase oxidation in white adipocytes via STAT3. Nat. Metab. 2(7), 620–634. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-020-0217-6 (2020).

Williams, C. M. Lipid metabolism in women. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 63(1), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS2003314 (2004).

Prendergast, B. J., Onishi, K. G. & Zucker, I. Female mice liberated for inclusion in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 40, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.01.001 (2014).

Becker, J. B., Prendergast, B. J. & Liang, J. W. Female rats are not more variable than male rats: A meta-analysis of neuroscience studies. Biol. Sex. Differ. 7, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-016-0087-5 (2016).

Dayton, A. et al. Breaking the cycle: Estrous variation does not require increased sample size in the study of female rats. Hypertens. Dallas Tex. 1979 68(5), 1139–1144. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08207 (2016).

Miller, C. K., Halbing, A. A., Patisaul, H. B. & Meitzen, J. Interactions of the estrous cycle, novelty, and light on female and male rat open field locomotor and anxiety-related behaviors. Physiol. Behav. 228, 113203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113203 (2021).

Ramírez-Hernández, D., López-Sanchez, P., Rosales-Hernández, M. C., Fonseca-Coronado, S. & Flores-Monroy, J. Estrous cycle phase affects myocardial infarction through reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide. Front. Biosci-Landmark. 26 (12), 1434–1443. https://doi.org/10.52586/5037 (2021).

Wang, M. et al. Mitochondrial connexin 43 in sex–dependent myocardial responses and estrogen–mediated cardiac protection following acute ischemia/reperfusion injury. Basic. Res. Cardiol. 115 (1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00395-019-0759-5 (2019).

Ventura-Clapier, R., Piquereau, J., Veksler, V., Garnier, A. Estrogens, estrogen receptors effects on cardiac and skeletal muscle mitochondria. Front. Endocrinol. 10, 557. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00557 (2019).

Louwagie, E. J. et al. Age and sex influence mitochondria and cardiac health in offspring exposed to maternal glucolipotoxicity. iScience 23 (11), 101746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101746 (2020).

Cook, S. J., Stuart, K., Gilley, R. & Sale, M. J. Control of cell death and mitochondrial fission by ERK1/2 MAP kinase signalling. Febs J. 284(24), 4177–4195. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.14122 (2017).

Yu, W., Xu, M., Zhang, T., Zhang, Q. & Zou, C. Mst1 promotes cardiac ischemia–reperfusion injury by inhibiting the ERK-CREB pathway and repressing FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy. J. Physiol. Sci. 69(1), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-018-0627-3 (2019).

Zhu, J. H. et al. Impaired mitochondrial biogenesis contributes to depletion of functional mitochondria in chronic MPP + toxicity: Dual roles for ERK1/2. Cell. Death Dis. 3(5), e312. https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2012.46 (2012).

Pedroza, D. A., Subramani, R. & Lakshmanaswamy, R. Classical and non-classical progesterone signaling in breast cancers. Cancers 12(9), 2440. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12092440 (2020).

Cavasin, M. A., Sankey, S. S., Yu, A. L., Menon, S. & Yang, X. P. Estrogen and testosterone have opposing effects on chronic cardiac remodeling and function in mice with myocardial infarction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 284(5), H1560–1569. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.01087.2002 (2003).

Fischer, A. et al. Changes in creatine transporter function during cardiac maturation in the rat. BMC Dev. Biol. 10(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-10-70 (2010).

Anmann, T. et al. Formation of highly organized intracellular structure and energy metabolism in cardiac muscle cells during postnatal development of rat heart. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1837(8), 1350–1361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.03.015 (2014).

Méndez-Carmona, N. et al. Differential effects of ischemia/reperfusion on endothelial function and contractility in donation after circulatory death. J. Heart Lung Transpl. Off Publ Int. Soc. Heart Transpl. 38(7), 767–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2019.03.004 (2019).

Holland, B. S. & Copenhaver, M. D. An improved sequentially rejective bonferroni test procedure. Biometrics 43(2), 417–423. https://doi.org/10.2307/2531823 (1987).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Ivana Jaric, the Neuroendocrinology group leader from the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science, University of Zurich, for her help with the estrus cycle determination.

Funding

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. We would like to thank the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant numbers: 310030_205073 and 323530_207033) and the Stiftung zur Förderung der herzchirurgischen Forschung am Inselspital for their financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the work and agreed with the content of this manuscript. MA, MS and SL obtained funding. AC, SG, DL, AH, MA, ME and AS performed experiments and collected data. AC, SG, MS, MA and SL performed the data analysis and interpretation. AC, SG wrote the manuscript; all authors revised it and gave feedback.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Clavier, A., Graf, S., Helmer, A. et al. Sex differences in cardiac graft recovery and pathophysiologic changes in a rat model of donation after circulatory death. Sci Rep 15, 45774 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28644-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28644-9