Abstract

Arcobacter butzleri is a foodborne pathogen associated with gastrointestinal disorders in humans. Its antibiotic resistance is well documented, and in vitro studies have shown its ability to colonise and invade human cell lines. Murine models are essential for integrating host immune responses and gut microbiota dynamics in infection studies. This study aimed to evaluate the pathogenicity and infectivity of A. butzleri strains using a murine model, focusing on invasion mechanisms and impact on intestinal microbiota. Fifteen Mus musculus C57BL/6J mice were orally infected with 8.5 Log CFU/ml of two strains. Faecal samples were collected before infection and over 14 days, while organs were analysed post-mortem. Infection was assessed using culture-dependent and culture-independent methods to study microbiota alterations. Molecular analyses confirmed the presence of A. butzleri in faecal samples until day 4. Beta-diversity analyses revealed significant differences in colonic microbiota between mice infected with the two strains. The duodenal microbiota was dominated by Paramuribaculum, Duncaniella, Dubosiella, and Muribaculum, whereas Akkermansia, Duncaniella, and Paramuribaculum were most prevalent in colonic and faecal samples. A. butzleri persisted under gastrointestinal conditions, a key feature for foodborne pathogens. Alterations in host microbiota were strongly associated with infection, emphasizing the critical role of microbial dynamics in A. butzleri pathogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Arcobacter genus includes several bacterial species isolated from environmental matrices, animals, food, and clinical cases1. Among these species, Arcobacter butzleri is the most frequently isolated species from food and is associated with human infections. It is considered a foodborne pathogen1,2. It can cause gastrointestinal disorders in humans and has been isolated from several food matrices, including food processing plant surfaces3,4. The adaptive and persistent capacity of this bacterium extends beyond the human and animal host, as it has been isolated from slaughterhouse environments even after sanitation procedures3,4. Furthermore, its multi-antibiotic resistance is well-documented, representing a risk factor in the case of infections4,5,6,7. Genomic analysis of A. butzleri strains isolated from farm animals demonstrated the presence of putative virulence genes8 and the overexpression of some of these genes in vitro, in particular those related to acetate, lactate, and iron metabolism9. Moreover, its ability to overcome the intestinal mucus barrier has been demonstrated8,10.

Even though in vitro cell models represent an important instrument for obtaining information about pathogens, mice are pivotal for including the impact of the gut microbiome in the evaluation of infection and the host immune system11. Studies in mice revealed that different A. butzleri strains can induce different immune responses in mice12,13, and infections in pigs14 and has been recovered from poultry after infection15. The different host responses to various strains align with the open pangenome of A. butzleri, indicating genomic variability within this species7,8. However, information about the host gut microbiota is lacking, especially considering strains characterised for their different colonisation ability in vitro and genomic content. Considering the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and virulence of A. butzleri, in vivo assays are needed to assess the impact of different strains on the host. Moreover, the use of mice enables a better understanding of gut microbiome dynamics during infection and the colonisation with A. butzleri. This aspect can be explored using next-generation sequencing (NGS) methods, which allow for the analysis of the faecal and organ microbiota of infected and control mice. This is crucial, considering that infection by bacterial pathogens can lead to changes in the microbiome, which in turn can impact the host16. Moreover, despite previous in vivo studies employing gnotobiotic interleukin-10 (IL-10) deficient murine models, which have demonstrated A. butzleri colonisation and induction of intestinal immune responses12,20, comparisons between microbiota and histopathological findings due to different A. butzleri strains, focused on both the severity and type of inflammation, are quite limited.

Therefore, the present study aims to assess the pathogenicity of two A. butzleri strains isolated from a chicken slaughterhouse after sanitisation procedures3. These strains exhibited genomic variability and a proven ability to form biofilms and colonize host gut cells in vitro (HT29-MTX-E12), including the capability to penetrate the mucus layer4. They were therefore chosen to colonise murine models to study their invasion mechanism and to raise awareness of the risk associated with possible infection. Gut segments and faeces microbiota of this animal model were evaluated to highlight the potential pathological effects and the main taxa involved in the alteration of the animal’s health status. This aspect is of considerable importance, as mammals have many taxa in common in their microbiome17. The results reported below focus on microbiome variations in infected mice, including a comparison between strains. Moreover, the mice’s health status and histological evaluation of the colon and duodenum will be considered during the isolation and detection of A. butzleri during the infection.

Results

Mice health status and microbiological sampling

During the 17 days, the mice’s weight changes were not statistically different comparing controls and infected mice (ANOVA, p-value > 0.05).

In the cages of mice infected with BZe322 and BZe363 (Table S1), a change in stool consistency was observed during the first four days of infection, generally more liquid than in the control condition. Additionally, there was a tendency for the animals to isolate themselves and reduced mobility. No obvious clinical signs were manifested during the remaining days.

Despite the use of the selective medium, it was not possible to detect the presence of A. butzleri by the culture-dependent method in faeces. A. butzleri load recorded was therefore < 100 CFU/mL. The total aerobic count of the faeces collected from each cage was measured during 14 days of the experiment (Table S2). Pairwise comparisons of the samples showed that the faeces of mice inoculated with strain BZe322 varied over time, with day 1 significantly differing from day 14 (Dunn’s test, p-value = 0.012) (Table S2). In addition, the load of faeces at day 1 inoculated with strain BZe322 (8.07 Log CFU/mL) was statistically higher than the load of faeces at day 1 inoculated with strain BZe363 (6.71 Log CFU/mL) (Kruskal–Wallis test = KW, Dunn’s Test, p-value = 0.048) (Table S2). The results highlight that in cages in which mice were subjected to infection with strain BZe322, the total microbial load decreased compared to the initial load. Comparing the total aerobic load of faecal samples 14 days after infection, the control mice had a higher load than the treated mice (8.20 Log CFU/mL; KW, Dunn’s Test, p-value = 0.003) (Table S2). The total faecal count of mice infected with the BZe363 strain was 7.83 Log CFU/mL, while the faeces of mice infected with the BZe322 strain had a load of 4.46 Log CFU/mL after 14 days (KW, Dunn’s Test, p-value = 0.040).

In colon and duodenum samples, the total aerobic count was evaluated (Fig. S1). Total aerobic loads did not differ significantly between mice infected and controls (KW p-value > 0.05). Despite the use of the selective medium, the presence of A. butzleri could not be detected by the culture-dependent method in this case either. The bacterial load recorded was therefore below 100 CFU/ml. After culture enrichment, two colon samples from mice infected with BZe322 (mice 566 and 562) tested positive for A. butzleri.

Histopathological analysis

Histopathological analysis revealed marginally significant differences across groups in duodenal inflammation severity (KW H = 5.833, p = 0.046) and colonic inflammation type (H = 5.333, p = 0.041). However, post hoc Dunn’s tests with Bonferroni correction did not detect any significant pairwise differences (p-value > 0.05), indicating that none of the individual group comparisons were statistically significant. No significant differences were observed for duodenal inflammation type (H = 1.386, p-value = 0.504) or colonic inflammation severity (H = 1.200, p-value = 0.189) (Fig. S2).

PCR and amplicon sequencing analysis of faecal samples

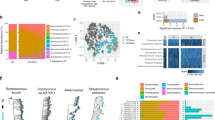

Genus- and species-specific PCR performed on genomic DNA from faeces detected and confirmed the presence of A. butzleri 4 days after infection. The samples that generated positive amplicons were faeces pulled from cages 363-A and B on day one, and cages 322-A and B on day one and day four. The alpha diversity performed on faeces of infected mice and controls didn’t show statistically significant differences (Dunn’s test p-value > 0.05), while the alpha diversity results performed with Shannon’s and Pielou’s indices resulted higher in faecal samples from mice infected with strain BZe322, highlighting significant differences between groups considering only strains as groups, excluding the sampling time (KW, Dunn’s test p-value < 0.05) (Fig. 1). Beta-diversity demonstrates similarities between groups considering strains and sampling time (PERMANOVA > 0.05). Bray-Curtis distances revealed differences between faeces from mice infected with BZe322 and BZe363 (ANOSIM, p-value adjusted = 0.02) (Fig. 2A).

There are no differences in the taxonomic units present during the 14 days of sampling (Table S3). The bacterial genera (Fig. 2B-C and Fig. S3) most commonly present in the faeces were Akkermansia, Paramuribaculum, Duncaniella, Bacteroides, Alloprevotella, and Muribaculum. Akkermansia spp. relative abundance corresponds to 26.8% in BZe322 samples, 30.2% in BZe363 samples and 39.1% in control (phosphate-Buffered Saline; PBS) samples. Paramuribaculum sp. relative abundance corresponds to 19.0% in BZe322 samples, 21.3% in BZe363 samples and 19.0% in control samples. Duncaniella sp. relative abundance corresponds to 9.0% of BZe322 samples, 7.1% of BZe363 samples and 6.0% of control samples. Considering the bacterial taxa composition, the separation between faeces from mice infected and controls has been observed (Fig. 2B and Figure S3). Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) and edgeR analysis demonstrated that some of the taxa were differentially abundant. A higher abundance of Bacteroides spp. characterized the mice faeces related to the BZe322 strain (log2 fold change = FC, -14.479, p-value [FDR] < 0.05) when compared to the faeces belonging to cage 363. The Lachnospiraceae family was more abundant in faeces from mice infected with BZe363 (log2 FC 2.14, p-value [FDR] < 0.05). The Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) confirmed the higher abundance of Lachnospiraceae in faeces from mice infected with BZe363 (score 3.82). LDA demonstrated higher abundances of genera Lactobacillus (LDA = 3.77) in faeces from mice infected with BZe363, while Angelakisella (LDA = 3.47), Eubacterium (LDA = 3.53) and Luxibacter (3.41) were more abundant in BZe322 group (Fig. 2C). Among these differentially abundant taxa, Eubacterium was positively associated with Pseudobutyricicoccus (Spearman’s correlation = 0.71) (Fig. 2D and Table S4).

Bacterial taxa analysis in faeces samples. The plot (A) shows Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) about beta-diversity displaying Bray-Curtis Index distance methods of faeces pull samples. The PBS group represents control samples. The panels (B) and (C) show species relative abundance grouped by controls and strains about the top 25 bacterial taxa in terms of abundance. The correlation between taxa in faecal samples is shown in the chord diagram (D).

PCR and amplicon sequencing analysis of duodenum and caecum

The results obtained from the molecular analysis (PCR) of the enriched broths of the duodenum and colon confirmed the same result obtained with the microbiological analysis. Samples positive for the presence of A. butzleri were 566 colon and 562 colon and duodenum. Both mice contaminated by A. butzleri were infected with strain BZe322 and came from cages A and B (Table S1).

The alpha diversity results didn’t demonstrate differences between duodenum groups (KW, p-value > 0.05) (Fig. S4). Colon of mice infected with BZe322 demonstrated lower Pielou’s and Shannon’s alpha diversities when compared with controls and BZe363 (Fig. 3). Also, Simpson and inverted Simpson demonstrated a lower alpha diversity of BZe322 colon samples compared with the colon of mice infected with BZe363 (KW, Dunn’s test, p-value < 0.05) (Fig. 3). Beta-diversity demonstrates differences in terms of bacterial microbiota between colon of mice infected with BZe322 and BZe363 (ANOSIM p-value adjusted < 0.05). As duodenum main genera resulted Paramuribaculum (29.0% for BZe322, 23.5% for BZe363 and 27.8% in controls), Duncaniella (16.7% for BZe322, 12.7% for BZe363 and 14.2% in controls), Dubosiella (11.9% for BZe322, 9.0% for BZe363 and 14.4% in controls) and Muribaculum (7.5% for BZe322, 10.3% for BZe363 and 12.7% in controls) (Fig. 4AB and S5A, Table S5). Paramuribaculum represents the most abundant bacterial genus in control (22.0%) and BZe363 (24.1%) colon samples, while 17% and 10.9% of the taxa were related to Akkermansia spp. respectively in controls and BZe363 (Fig. 4CD and S5B). Duncaniella spp. represents the 8.1 and 9.6% of the controls and BZe363 colon samples, respectively (Fig. 4CD and S5B). The most abundant taxa of colons from the colon of mice infected with BZe322 were Akkermansia spp. (41.1%), Paramuribaculum spp. (15.8%) and Duncaniella spp. (8.3%) (Fig. 4CD and S5B). Colon samples demonstrated differences in terms of taxa abundance between groups (KW, Dunn’s test p-value [Holm] < 0.05) (Fig. 5).Table S6Lachnospiraceae (log2 FC 27.831, p-value [FDR] < 0.05) increased in the colon of mice infected with BZe363 compared to colon samples of strain BZe322. Compared to the BZe322-infected mice colon, the genera Eubacterium, Odoribacter, Muribaculum, and Nanosyncococcus were more abundant in the colon of mice infected with BZe363.

Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the pathogenicity of two A. butzleri strains with distinct genomic content4, in a mice model, analysing the microbiota of the faeces and gut segments, including a comparison with health status and histopathological features. The preliminary in vitro colonisation capacities of BZe322 and BZe363, results from an earlier study4, were identical. The present in vivo results confirmed the pathogenicity of the A. butzleri strains, with differences between strains not previously detected in the in vitro study4. The higher severity of inflammation (SOI) of strain BZe322 demonstrated the importance of in vivo test and the use of genomic analysis to evaluate the bacterial pathogenicity and virulence.

A. butzleri, detected in colon samples after culture enrichment, demonstrated the ability to survive in gastrointestinal tract conditions, although a reduction in load was observed, likely due to the high microbial load of the host’s microbiome. This aspect is fundamental for a foodborne pathogen that is primarily associated with gastrointestinal disorders and requires adaptive abilities to various host factors, including gastric and gut conditions18. However, the low number of amplicon-sequence variants (ASVs) demonstrates a reduction in its load after passing through the gastrointestinal tract, with a consequent masking effect by host microbiota taxa. Furthermore, it is important to recognize that the amplicon sequencing approach does not allow discrimination between viable and non-viable bacterial cells. The variations in host-microbiome have been associated with bacterial infection19. The lower microbial load in the faeces of infected mice demonstrated the influence of A. butzleri on the health status of the mice. In fact, also in humans, a lower microbial load has been observed in patients affected by diseases including Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, liver cirrhosis, Clostridium difficile and HIV infection that are frequently associated with diarrhoea20. Nevertheless, future studies about A. butzleri infections should consider including anaerobic conditions to capture obligate anaerobic populations, which play critical roles in gut microbiota composition and function21. The lower microbiota richness observed in the colon of mice infected with the strain BZe322 demonstrates that A. butzleri infection can also lead to host microbiome perturbation. The higher alpha diversity in BZe322 faeces can be attributed to the lower microbial load in faecal samples, which allows for the detection of more microbial taxa due to the lower number of dominant ASVs.

Histopathological analysis revealed only subtle differences in inflammatory scores across gut segments. In the duodenum, strain BZe322 showed a numerically higher inflammation severity (mean score: 1.5 vs. 0.667 for control), although pairwise comparisons did not reach statistical significance after correction. BZe363 did not markedly alter duodenal inflammation. Across all groups, the predominant type of duodenal inflammation was lymphoplasmacellular, suggesting a consistent adaptive immune response. In the colon, neither strain significantly affected inflammation severity, and only minor variations in inflammation type were observed. These results indicate that, under the present experimental conditions, A. butzleri strains may exert limited and subtle, segment-dependent effects on intestinal immune responses4,8. These findings align with previous research using gnotobiotic or IL-10-deficient mouse models, where strain-specific differences in A. butzleri pathogenic potential were reported22. The consistent lymphoplasmacellular infiltration observed here supports the notion that A. butzleri can induce adaptive immune activation, albeit without overt pathological severity in immunocompetent mice12. The minor changes in colonic inflammation may reflect a contained or qualitatively different immune interaction in the distal gut, potentially influenced by the local microbiota and associated metabolites.

The differences between sample groups were related to specific taxa and microbiome composition as demonstrated by the beta-diversity. Mice infected with BZe363 demonstrated a higher abundance of taxa that are normally related to competition with pathogens and can interact with gut mucins, for these reasons, Lactobacillus23 and Lachnospiraceae24 are considered beneficial taxa. The importance of mucus in A. butzleri colonisation8 and the increase of taxa that can interact with mucins can be related to the lower SOI of the strain BZe363. The strain BZe322 caused an increase of bacteria that are related to short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) metabolism, specifically the genera Angelakisella25 and Eubacterium26. Eubacterium spp., which showed a positive correlation with Pseudobutyricicoccus spp., includes species that can induce mucin secretion27. These species, which can modulate inflammatory response in host gut28, demonstrated variations in taxa abundance in case of infection related to BZe322, which was linked to higher SOI. The differential abundance of taxa related to SCFAs and, in consequence, with mucins, can be related again to the Arcobacter spp. mucus colonisation abilities8. Colon microbiota of BZe363-infected mice in comparison with those infected with BZe322 demonstrated again a higher abundance of the beneficial taxa. These include Lachnospiraceae24 together with Muribaculum spp. that is considered a potential probiotic29, Eubacterium spp. that is linked to SCFAs metabolism26, while Odoribacter spp. is considered related to SCFAs production and has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)30. The observed differences between BZe322 and BZe363 indicate strain-specific interaction between A. butzleri and host microbiome. Furthermore, it would be valuable for future research to explore the differential abundance of taxa linked to mucins and SCFAs, to elucidate their possible contribution to A. butzleri colonization in the gut. It is therefore possible to hypothesise mechanisms of commensalism between Arcobacter and host microbiota species, particularly for A. butzleri strain BZe322, although this hypothesis requires further elucidation. It should be noted that, since no heat-killed bacterial control group was included, we cannot fully exclude that part of the observed microbiota and inflammatory changes resulted from exposure to bacterial components rather than from active colonization.

Conclusion

Genetically distinct A. butzleri strains4, demonstrated different ability to survive the natural barriers present in mammals (stomach and intestines) and to transit through the entire gastrointestinal tract. The in vivo test showed that strain BZe322 induced a more severe infection in the duodenal tract. Moreover, the two strains demonstrated different influences on microbiota composition and reduction in microbial diversity. Strain BZe363, compared to strain BZe322, induced an increase in taxa involved in immune defence, such as Lachnospiraceae, Muribaculum and Lactobacillus. The high persistence associated with the high level of antibiotic resistance, the ability to survive in the gastrointestinal tract, and the confirmed in vivo pathogenicity of A. butzleri suggest the necessity of surveillance focused on this microorganism. Future studies incorporating heat-killed bacterial controls would help to better distinguish infection-driven effects from host responses to nonviable bacterial material. Moreover, in vivo studies including additional Arcobacter species and strains and considering host/bacteria gene expression, will allow further evaluation of its virulence mechanism.

Materials and methods

Preparation of strains for mice infection

A single colony of the A. butzleri strains BZe322 and BZe363 respectively deposited as TUCC00000927 and TUCC00000930 at the Turin University Culture Collection – TUCC (https://www.tucc.unito.it/it) was inoculated into 3 ml of Arcobacter broth (CM0965; Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) and incubated at 30 °C for 48 h in a microaerobic condition without agitation (CN0035A; Thermo Fischer, Waltham, MA, USA). One hundred microliters of broth culture were then inoculated into 8 mL of fresh Arcobacter broth and incubated at 30 °C overnight under microaerobic conditions without agitation. Five hundred microliters of broth culture were inoculated onto Arcobacter agar plates using the spread plate technique and incubated at 30 °C for 48 h in a microaerobic condition without agitation. The resulting cell layer was collected with 1 mL of Ringer’s solution (115525; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and centrifuged for 10 min at 17,000 x g. The pellets were resuspended in 8 mL of PBS 1X (P3813; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Concentrations were determined with decimal serial dilutions on Arcobacter agar plates.

Mice infection and experimental plan design

Infections were carried out with strains BZe322 and BZe363 separately, and a control test using PBS 1X was included. Experiments were conducted using the non-genetically modified Mus musculus C57BL/6J. The study involved 15 mice housed in 5 separate cages (PBS, BZe363-A, BZe363-B, BZe322-A, BZe322-B) (Table S1). One cage served as the negative control (PBS 1X), while the remaining four cages were used for infection with the two different A. butzleri strains. Two cages were assigned to each strain (BZe322 and BZe363) to provide biological replicates (322-A/B and 363-A/B). Mice were inoculated for two consecutive days with 0.3 mL of solution (bacterial suspension in PBS 1X or PBS 1X). The gavage method was used for the administration. During the two consecutive days of administration, mice were infected with a microbiological load of 8.5 Log CFU/mL. To assess the presence and microbial load of A. butzleri, faecal samples were collected from each cage at the following time points: before infection (T0), and at 1 (D1), 4 (D4), 8 (D8), 11 (D11), and 14 (D14) days post-infection. Clinical signs and animal weights were assessed at each sampling time. After 17 days post-infection (D17), with an average weight of 26.4 g ± 1.9 (Table S1), mice were euthanised by cervical dislocation under isoflurane anaesthesia (Abbott, Germany), and tissue samples from the intestinal tract (duodenum and colon) were removed under sterile conditions. Intestinal tissues from each mouse were simultaneously processed for histopathological analysis and microbiological analyses. No additional anaesthesia was required during the experimental procedures, since animals were only monitored for clinical signs and body weight without undergoing invasive manipulations prior to euthanasia.

Microbiological analysis of faeces and organs

A faecal sample was collected from all 5 cages, 2 g of sample was weighed and diluted 1:10 Ringer’s solution, and homogenised for two minutes (Interscience, Saint-Nom-la-Bretèche, France). One millilitre of the homogenised samples was taken and centrifuged at 17,000 x g for 10 min. The supernatants were discarded, and the pellets were stored at -20 °C for further molecular analysis. The other part of the homogenised samples was used to perform microbiological analyses within two hours of sample collection. The total aerobic count was evaluated on Plate Count Agar (PCA) (84608; VWR, Radnor, PA, USA), and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h under aerobic conditions without agitation31. For the detection of A. butzleri, the selective medium Arcobacter agar supplemented with cefoperazone (16 mg/L) (C4292), amphotericin B (10 mg/L) (A2411), 5-fluorouracil (100 mg/L) (F6627), novobiocin (32 mg/L) (74675) and trimethoprim (64 mg/L) (T7883) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, (St. Louis, MO, USA) and with 10% (v/v) of defibrinated horse blood (17.0159; Microbiol, Italy)4,32 was used. The plates were incubated at 30 °C for 48 h under microaerophilic conditions without agitation. The microbiological analysis on the faeces was performed at: T0, D1, D4, D8, D11, and D14.

After 17 days, the duodenum and colon were dissected, and a part was preserved at -20 °C for molecular analysis. Microbiological analyses were conducted on the organs and intestinal tracts of the mice examined. At each sample, 400 µl of Ringer solution was added, and the organs were homogenised to perform serial decimal dilutions. The microbiological assessment was carried out using the same media procedure as that for faeces, as described above.

Molecular analysis of faeces and organs for the identification of A. butzleri

The DNA extraction from faeces and organs was performed using the QIAamp® Kit PowerFecal® Pro DNA Kit (51804; QIAGEN, Hilden, GER) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA was quantified and qualitatively assessed with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ND1000; Thermo Fischer, Waltham, MA, USA) and electrophoretic run-in agarose gel at 1% v/w in Tris-Acetate-EDTA (TAE) 1X for 30 min at 100 V. Qbit 2.0 (Thermo Fischer, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for DNA quantification. The DNA was brought to a final concentration of 100 ng/µl.

Two PCR reactions were performed to determine the presence of A. butzleri in the sample. The first PCR used the genus-specific primers to detect Arcobacter spp33. PCR amplification was performed in a reaction mixture (25 µl) containing buffer 5X, 2U/µl Taq Polymerase (PB10.11; Biosystems, UK), and 100 ng/µl of DNA. The Arcobacter genus-specific 16S rRNA fragment was amplified using the forward primer (10 µM) Arco I (5’-AGAGATTAGCCTGTATTGTAT-3’) and the reverse primer (10 µM) Arco II (5’- TAGCATCCCCGCTTCGAATGA-3’) yielding an amplicon of 1223 bp33. The thermocycling program was 94 °C for 4 min, 94 °C for 1 min, 56 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 1 min (25 cycles), and 72 °C for 7 min. Analysis of PCR products was done by electrophoresis (60 V, 1.5 h) in 1.5% agarose gels (wt/vol)33.

The PCR for the species-specific detection of A. butzleri34 was performed using the forward primer (10 µM) ArcoF (5′-GCYAGAGGAAGAGAAATCAA-3′) and the reverse primer (10 µM) But R (5′-TCCTGATACAAGATAATTGTACG-3), which amplifies the 23 S rRNA gene with a 2061 bp amplicon. The same concentrations and volumes as described above were used for the other Mix PCR reagents. The thermocycling program was 94 °C for 3 min, 94 °C for 45 s, 58 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 2 min (30 cycles), and 72 °C for 5 min. Analysis of PCR products was done by electrophoresis (100 V, 1 h) in 1.5% agarose gels (wt/vol).

Amplicon-based sequencing for metataxonomic analysis

Metataxonomic analysis was performed on faeces, duodenum, and colon DNA samples. Library of the V3-V4 region was constructed from the 16S rDNA gene region35 using the primer pair (1 mM) forward (5’-TACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3’)36 and reverse (5’-CCAGGGTATCTAATCC-3’)37 yielding an amplicon of 460 bp. The PCR products were prepared for Illumina sequencing using the Illumina MiSeq System protocol for library preparation with the Hamilton automatic machine (Hamilton, Reno, Nevada, USA). Briefly, the PCR amplicons were purified using the Agencourt AMPure kit (Beckman Coulter, Milan, Italy) and tagged with sequencing adapters using the Nextera XT library preparation kit (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The bioinformatics analysis was performed using QIIME 2 vr. 2022.2.0 (https://docs.qiime2.org/). Raw reads were imported into QIIME2 for the quality and chimera filtering step by the dada2 denoise-paired script. The sampling depth used was 10.000. The ASVs obtained were used for taxonomic assignment against the Greengenes2 2022.10 database obtaining bacterial taxa abundances. The raw sequence reads are available on National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/) at the bioproject accession number PRJNA1167237.

Histopathological analysis

After 17 days of infection (D17), samples from the intestinal tract (duodenum and colon) were collected and routinely processed for histopathological analysis. Briefly, samples were immediately fixed in 5% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Section (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Histopathological evaluations were conducted using a semi-quantitative scoring system (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe), assessing the severity of inflammation in mucosa, submucosa, and muscle layers38,39. Additionally, the type of inflammatory cells (lymphoplasmacellular = 1, mixed or with neutrophils = 2, and eosinophilic = 3) was also evaluated. The scores were considered as continuous numerical variables, resulting from the sum of the partial inflammation scores of the three wall portions (mucosa-Muc, submucosa-Subm and muscle layer-Musc). All the slides were independently assessed by two observers, and discordant cases were reviewed using a multi-head microscope until a unanimous consensus was reached.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of taxa was performed using RStudio software version 4.2.2 (2022-10-31 ucrt). using the R package microeco (v1.13.0)40 and Microbiome Analyst 2.0 (https://www.microbiomeanalyst.ca/) software for taxa analysis. For the alpha diversity analysis, the Shannon and Chao1 metrics were used. For beta-diversity analysis, a Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) graph was generated showing the distance metric Bray-Curtis Index. The analyses of the 16S rDNA Illumina amplicon sequencing were conducted considering the taxonomic level of genus as the highest reliable classification41. Regarding histopathology, data were analysed using SPSS software (IBM 2.9.0.0.0). First, the normality of the data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, a widely recognised method for evaluating normality. Following this, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis’ test was employed for ranking analysis due to its robustness in handling non-normally distributed data and its suitability for comparing multiple groups simultaneously. In the event of statistically significant differences observed in mean rankings among the groups, Dunn’s post hoc test, a method recommended for pairwise comparisons following non-parametric tests, was applied to further examine the specific mean ranking differences among the various treated groups.

Data availability

Raw sequence reads are available on Sequence Read Archive (National Center for Biotechnology Information; NCBI) at the bioproject accession number PRJNA1167237 (NCBI; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/).

References

Buzzanca, D., Kerkhof, P. J., Alessandria, V., Rantsiou, K. & Houf, K. Arcobacteraceae comparative genome analysis demonstrates genome heterogeneity and reduction in species isolated from animals and associated with human illness. Heliyon 9, (2023).

Ramees, T. P. et al. Arcobacter: an emerging food-borne zoonotic pathogen, its public health concerns and advances in diagnosis and control – a comprehensive review. Vet. Q. 37, 136–161 (2017).

Botta, C. et al. Microbial contamination pathways in a poultry abattoir provided clues on the distribution and persistance of Arcobacter spp. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 90, (2024).

Chiarini, E. et al. Exploring multi-antibiotic resistance in Arcobacter Butzleri isolates from a poultry processing plant in Northern italy: an in-depth inquiry. Food Control 163, (2024).

Buzzanca, D., Chiarini, E. & Alessandria, V. Arcobacteraceae: an exploration of antibiotic resistance featuring the latest research updates. Antibiotics 13, 669 (2024).

Müller, E., Abdel-Glil, M. Y., Hotzel, H., Hänel, I. & Tomaso, H. Aliarcobacter Butzleri from water poultry: insights into antimicrobial resistance, virulence and heavy metal resistance. Genes (Basel). 11, 1–16 (2020).

Isidro, J. et al. Virulence and antibiotic resistance plasticity of Arcobacter butzleri: insights on the genomic diversity of an emerging human pathogen. Infect. Genet. Evol. 80, 104213 (2020).

Buzzanca, D. et al. Functional pangenome analysis reveals high virulence plasticity of Aliarcobacter Butzleri and affinity to human mucus. Genomics 113, 2065–2076 (2021).

Buzzanca, D. et al. Transcriptome analysis of Arcobacter Butzleri infection in a mucus-producing human intestinal in vitro model. Microbiol. Spectr 11, (2023).

Baztarrika, I., Wösten, M. M. S. M., Alonso, R. & Martínez-Ballesteros, I. Martinez-Malaxetxebarria, I. Genes involved in the adhesion and invasion of Arcobacter Butzleri. Microb. Pathog. 193, 106752 (2024).

Herzog, M. K. M. et al. Mouse models for bacterial enteropathogen infections: insights into the role of colonization resistance. Gut Microbes. 15, 1–36 (2023).

Gölz, G., Alter, T., Bereswill, S. & Heimesaat, M. M. The immunopathogenic potential of Arcobacter butzleri - Lessons from a meta-analysis of murine infection studies. PLoS One 11, (2016).

Heimesaat, M. M., Alter, T., Bereswill, S. & Gölz, G. Intestinal expression of genes encoding inflammatory mediators and gelatinases during Arcobacter Butzleri infection of gnotobiotic IL-10 deficient mice. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 6, 56–66 (2016).

Wesley, I. V., Baetz, A. L. & Larson, D. J. Infection of cesarean-derived colostrum-deprived 1-day-old piglets with Arcobacter butzleri, Arcobacter cryaerophilus, and Arcobacter Skirrowii. Infect. Immun. 64, 2295–2299 (1996).

Wesley, I. V. & Baetz, A. Natural and experimental infections of Arcobacter in poultry. Poult. Sci. 78, 536–545 (1999).

Ferreira, S. C. M., Jarquín-Díaz, V. H. & Heitlinger, E. Amplicon sequencing allows differential quantification of closely related parasite species: an example from rodent coccidia (Eimeria). Parasit. Vectors. 16, 204 (2023).

Nguyen, T. L. A., Vieira-Silva, S., Liston, A. & Raes, J. How informative is the mouse for human gut microbiota research? DMM Dis. Model. Mech. 8, 1–16 (2015).

Sistrunk, J. R., Nickerson, K. P., Chanin, R. B., Rasko, D. A. & Faherty, C. S. Survival of the fittest: how bacterial pathogens utilize bile to enhance infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 29, 819–836 (2016).

Iljazovic, A. et al. Perturbation of the gut Microbiome by Prevotella spp. Enhances host susceptibility to mucosal inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 14, 113–124 (2021).

Nishijima, S. et al. Fecal microbial load is a major determinant of gut Microbiome variation and a confounder for disease associations. Cell 188, 222–236e15 (2025).

Sadaghian Sadabad, M. et al. A simple coculture system shows mutualism between anaerobic faecalibacteria and epithelial Caco-2 cells. Sci. Rep. 5, 17906 (2015).

Gölz, G. et al. Arcobacter Butzleri induce colonic, extra-intestinal and systemic inflammatory responses in gnotobiotic il-10 deficient mice in a strain-dependent manner. PLoS One 10, (2015).

Nishiyama, K., Sugiyama, M. & Mukai, T. Adhesion properties of lactic acid bacteria on intestinal mucin. Microorganisms 4, 34 (2016).

Ćesić, D. et al. Association of gut Lachnospiraceae and chronic spontaneous urticaria. Life 13, 1280 (2023).

Qiu, X. et al. Identification of gut microbiota and microbial metabolites regulated by an antimicrobial peptide Lipocalin 2 in high fat diet-induced obesity. Int. J. Obes. 45, 143–154 (2021).

Mukherjee, A., Lordan, C., Ross, R. P. & Cotter, P. D. Gut microbes from the phylogenetically diverse genus Eubacterium and their various contributions to gut health. Gut Microbes. 12, 1802866 (2020).

Bai, D. et al. Eubacterium coprostanoligenes alleviates chemotherapy-induced intestinal mucositis by enhancing intestinal mucus barrier. Acta Pharm. Sin B. 14, 1677–1692 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Regulation of short-chain fatty acids in the immune system. Front. Immunol. 14, 1–14 (2023).

Zhu, Y. et al. Exploration of the Muribaculaceae family in the gut microbiota: diversity, metabolism, and function. Nutrients 16, 2660 (2024).

Bosch, B. et al. Development of a time-dependent oral colon delivery system of anaerobic Odoribacter splanchnicus for bacteriotherapy. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 190, 73–80 (2023).

Rodriguez-Palacios, A. et al. Cyclical bias’ in Microbiome research revealed by a portable germ-free housing system using nested isolation. Sci. Rep. 8, 3801 (2018).

Houf, K. & Stephan, R. Isolation and characterization of the emerging foodborn pathogen Arcobacter from human stool. J. Microbiol. Methods. 68, 408–413 (2007).

Harmon, K. M. & Wesley, I. V. Identification of Arcobacter isolates by PCR. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 23, 241–244 (1996).

Douidah, L., De Zutter, L., Vandamme, P. & Houf, K. Identification of five human and mammal associated Arcobacter species by a novel multiplex-PCR assay. J. Microbiol. Methods. 80, 281–286 (2010).

Hautefeuille, S. et al. Extensive multivariate dataset characterizing bacterial community diversity and Campylobacter contamination level in a large number of conventional broilers carcasses after air chilling and refrigerated storage. Data Br. 56, 110858 (2024).

Turner, S., Pryer, K. M., Miao, V. P. W. & Palmer, J. D. Investigating deep phylogenetic relationships among cyanobacteria and plastids by small subunit rRNA sequence analysis. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 46, 327–338 (1999).

Kisand, V., Cuadros, R. & Wikner, J. Phylogeny of culturable estuarine bacteria catabolizing riverine organic matter in the Northern Baltic sea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 379–388 (2002).

Guantario, B. et al. A comprehensive evaluation of the impact of bovine milk containing different beta-casein profiles on gut health of ageing mice. Nutrients 12, 1–19 (2020).

Iacobucci, D., Popovich, D. L., Moon, S. & Román, S. How to calculate, use, and report variance explained effect size indices and not die trying. J. Consum. Psychol. 33, 45–61 (2023).

Liu, C., Cui, Y., Li, X. & Yao, M. Microeco: an R package for data mining in microbial community ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 97, 1–9 (2021).

Curry, K. D. et al. Emu: species-level microbial community profiling of full-length 16S rRNA Oxford nanopore sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 19, 845–853 (2022).

Funding

This research was funded by Cassa di Risparmio di Torino (https://www.fondazionecrt.it/, accessed on February 28, 2025), grant number ALEV_CRT_20_01-Fondazione CRT 2019: Diffusion of Arcobacter spp. in Piedmont poultry meats and study of its pathogenic potential.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Elisabetta Chiarini and Angela Della Sala: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Davide Buzzanca: Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision. Francesco Chiesa, Maria Teresa Capucchio and Talal Hassan: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Kurt Houf: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Alessandra Ghigo and Valentina Alessandria: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Alessandra Ghigo is cofounder and shareholder of Kither Biotech Srl, a pharmaceutical company focused on the development of PI3K inhibitors for airway diseases, not in conflict with the content of this paper. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical statement

Non-genetically modified Mus musculus C57BL/6J were used to assess the pathogenicity of two A. butzleri strains isolated from a chicken slaughterhouse3. Mice used in all experiments were 8 to 12 weeks of age. Mice were group-housed, provided free access to standard chow and water in a controlled facility providing a 12-hour light/dark cycle. All animal procedures were approved by the local Animal Ethics Committee and conducted in full compliance with institutional and national animal welfare regulations, following the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org) and were approved by the animal ethical committee of the University of Torino and by the Italian Ministry of Health (Authorization n° 353/2022-PR).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chiarini, E., Della Sala, A., Buzzanca, D. et al. Gut and faecal microbiota alterations in mice following infection with Arcobacter butzleri strains from a food processing plant. Sci Rep 15, 44801 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28655-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28655-6