Abstract

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common malignancy in women worldwide, with distant metastasis being the leading cause of BC-related mortality. The neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio (NPAR), reflecting systemic inflammation and nutritional status, has shown prognostic potential in other cancers, but its role in BC remains unclear. We conducted a single-center retrospective and prospective cohort study including 348 invasive BC patients admitted between 2016 and 2023. Baseline NPAR was calculated before treatment. Logistic regression and restricted cubic spline analyses were used to assess associations between NPAR and distant metastasis risk. For metastatic patients, overall survival (OS) was evaluated prospectively through outpatient visits, telephone contact, and review of medical records using Kaplan–Meier curves and Cox regression. NPAR was significantly higher in metastatic than non-metastatic patients [median 15.9 vs. 15.0, P < 0.001]. Each SD increase in NPAR was associated with 65% higher odds of distant metastasis (adjusted OR 1.647, 95% CI 1.275–2.162). Using the cutoff of 17.7, high NPAR predicted a fourfold higher metastasis risk (OR 4.136, 95% CI 2.231–7.961). Among metastatic patients, high NPAR was linked to shorter OS (45 vs. 63 months; log-rank P = 0.036) and doubled mortality risk (HR 2.064, 95% CI 1.022–4.169). Baseline NPAR is an independent predictor of metastasis risk and survival in BC. As a simple, inexpensive, and clinically available biomarker, NPAR may facilitate early risk stratification and guide personalized management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most prevalent malignancy among women worldwide, and distant metastasis remains the leading cause of BC-related mortality1,2. Epidemiological data indicate that approximately 20–30% of patients with early-stage BC will eventually develop distant metastases, with the 5-year survival rate of metastatic BC being markedly lower than that of localized disease3,4. Despite substantial advancements in early detection, surgical techniques, and adjuvant therapies, accurately predicting the risk of distant metastasis and assessing the prognosis of patients with metastatic BC remain significant clinical challenges5. These difficulties underscore the urgent need for novel prognostic biomarkers and predictive tools.

Emerging evidence suggests that BC metastasis involves intricate molecular mechanisms, including tumor microenvironment remodeling, immune evasion, and systemic inflammatory responses6. Among these, disruption of the inflammation–nutrition balance plays a pivotal role in tumor progression and metastatic spread, with aberrations in specific inflammation–nutrition biomarkers being closely linked to an increased risk of BC metastasis7. Nonetheless, most current prognostic models rely heavily on conventional clinicopathologic parameters, with limited systematic evaluation of novel composite biomarkers.

The neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio (NPAR) is defined as the ratio of neutrophil percentage to serum albumin concentration, representing a clinically practical composite index. In the context of BC metastasis, neutrophils can release neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) to capture circulating tumor cells, thereby facilitating the formation of a pre-metastatic niche and promoting metastatic progression8,9. Elevated circulating neutrophil levels have been strongly associated with an increased risk of metastasis and poor prognosis in BC10. Serum albumin, an essential transport protein, contributes to multiple physiological functions including maintenance of colloid osmotic pressure, antioxidant defense, immune regulation, and nutrient transport. Hypoalbuminemia often reflects malnutrition, systemic inflammation, or impaired hepatic function11. In malignancies, albumin levels may decline due to catabolic consumption as well as inflammatory cytokine-mediated suppression of synthesis and function12,13. Consequently, NPAR not only reflects systemic inflammation but also serves as an integrative measure of the host’s nutritional and immunologic status.

Recent work by Li et al. demonstrated that NPAR consistently predicts prognosis across multiple cancer types; both categorical and continuous NPAR measures were positively correlated with cancer-specific mortality14. The reproducibility of these associations across different cancers and study designs supports NPAR as a reliable prognostic biomarker. Previous studies have shown NPAR to be prognostically valuable in various diseases15,16,17, including oral cancer, bladder cancer, and gastric cancer14. Wang et al. reported that higher NPAR levels were independently associated with increased all-cause and cancer-specific mortality among cancer survivors, including those with BC18. Elevated neutrophils during tumor progression likely reflect systemic inflammatory activation, while the reduction in serum albumin due to tumor burden and nutritional depletion may further worsen outcomes19,20. These findings offer a mechanistic rationale for the strong association between high NPAR and increased mortality risk and support the concept that NPAR is not merely an inflammatory marker but also an important prognostic indicator in BC18.

However, evidence regarding the utility of NPAR in predicting distant metastasis in BC remains scarce. Elucidating the relationship between NPAR and the risk of BC metastasis may help identify high-risk patients and inform individualized monitoring and therapeutic strategies. In this study, combining a single-center retrospective cohort with prospective follow-up, we employed multivariable logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards models to assess the association of NPAR with distant metastasis risk and overall survival (OS) in metastatic BC. Through the analysis of a large clinical dataset, we aimed to determine whether NPAR could serve as a marker to identify patients at high risk of distant metastasis, provide prognostic stratification for those with metastatic BC, and ultimately improve metastatic risk prediction, optimize clinical decision-making, and guide personalized therapeutic management.

Materials and methods

Study design and ethical approval

This retrospective study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Guangxi Medical University Cancer Hospital (Approval No.: KY2023868) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Baseline clinical and laboratory data were collected retrospectively, whereas the survival of metastatic patients was followed prospectively until June 1, 2025. The requirement for written informed consent was waived by the committee because the study analyzed previously collected and de-identified clinical data and involved minimal risk to participants in accordance with applicable national regulations. Patient confidentiality was strictly protected throughout the study.

Study population

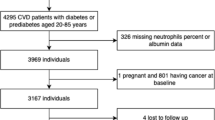

We included female patients with breast cancer who were admitted to our hospital between September 2016 and December 2023. The inclusion criteria were as follows:1 newly diagnosed breast cancer, pathologically confirmed as invasive breast carcinoma;2 complete baseline hematological examination (including leukocyte differential count and serum albumin measurement) performed prior to any anti-tumor treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, endocrine therapy, surgery, etc.);3 distant metastasis status clearly determined by clinical and imaging assessments; and4 complete demographic, pathological, and follow-up data.

Exclusion criteria were:1 co-existence of other primary malignancies;2 acute or chronic inflammatory diseases, significant hepatic or renal dysfunction, or other conditions that may affect hematological indices or albumin levels;3 prior receipt of systemic anti-tumor therapy; and4 incomplete clinical data or unavailable follow-up information.

The patient selection process is summarized in (Fig. 1).

Grouping and follow-up

Patients were classified into a metastasis group and a non-metastasis group according to the presence of distant metastases at initial diagnosis, for the purpose of diagnostic performance analysis. Distant metastasis was diagnosed based on imaging modalities (e.g., CT, MRI, PET-CT, bone scan) and/or pathological confirmation, with common metastatic sites including bone, lung, and liver.

Patients in the metastasis group were prospectively followed to record overall survival (OS). Follow-up was conducted via outpatient visits, telephone contact, and medical record system review, with the cutoff date of June 1, 2025. OS was defined as the interval from the diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer to the date of death from any cause or last follow-up. Ultimately, 163 patients in the metastasis group and 185 in the non-metastasis group had complete follow-up data. The baseline characteristics of the two groups are presented in (Table 1).

The sample size of this study was not based on a priori power analysis but included all consecutively eligible patients with complete baseline clinical and laboratory data during the study period (September 2016–December 2023). Therefore, the cohort size reflects the total available population rather than a predetermined calculation.

Data collection

Fasting venous blood samples were collected in the morning for all patients by trained nurses using standard collection tubes, with strict adherence to sampling protocols. Samples that were contaminated or insufficient in volume were discarded.

Complete blood counts were analyzed using the Mindray CAL8000plus automated hematology system (Shenzhen Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics Co., Ltd., China) with standardized reagent lots, and rigorous quality control was performed prior to each assay. Serum albumin levels were measured using the Siemens ADVIA Chemistry XPT automated analyzer (Siemens Healthineers, Germany). The laboratory complied with the quality control standards set by the National Center for Clinical Laboratories (NCCL), with daily calibration and internal quality control performed to ensure accuracy and consistency. All tests for patients in this cohort were conducted in the same laboratory using identical equipment and reagents to minimize batch-to-batch variability.The NPAR was calculated using the formula:

Additional clinical parameters collected included age, marital status, educational level, place of residence, body mass index (BMI), pathological type, histological grade, molecular subtype (HR/HER2 status), menstrual status, and comorbidities (such as hypertension and diabetes).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.5.1 and SPSS version 25.0. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range [M (Q1, Q3)], depending on their distribution. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage [n (%)]. Comparisons between groups were conducted using the independent-samples t-test for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variables were analyzed using the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test (for expected counts < 5).

NPAR was analyzed both as a categorical variable based on tertiles (Q1, Q2, Q3) and as a continuous variable after Z-score standardization. The tertile-based categorization of NPAR was selected to achieve balanced group sizes and to capture potential non-linear relationships between NPAR and clinical outcomes without relying on arbitrary cutoffs. Three logistic regression models were constructed to evaluate the association between NPAR and distant metastasis risk: Model 1, unadjusted; Model 2, adjusted for demographic characteristics and comorbidities (age, marital status, menstrual status, educational level, hypertension, diabetes, insurance type, residential area, and BMI); and Model 3, further adjusted for tumor characteristics (pathological type, histological type, and molecular subtype) in addition to Model 2 covariates. The results were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). A P for trend was calculated to assess dose–response relationships. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) functions with three knots were used to examine potential non-linear associations between NPAR and the risk of distant metastasis, with P-overall and P-nonlinear reported.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) and its 95% CI. The optimal cutoff value was determined using the Youden index (sensitivity + specificity − 1), and participants were categorized into high and low NPAR groups based on this threshold. The logistic regression models were then repeated to evaluate metastasis risk in these groups, with low NPAR as the reference. Fully adjusted logistic regression models were also performed within subgroups, and likelihood ratio tests were used to assess interaction effects.

For survival analysis in the metastasis group, Kaplan–Meier curves were plotted according to NPAR tertiles, with group differences assessed by the log-rank test and pairwise comparisons performed as appropriate. Cumulative survival rates, median survival time, and their corresponding 95% CIs were calculated. Three Cox proportional hazards regression models (using the same adjustment strategy as the logistic regression models) were applied to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for mortality risk. Additionally, Cox RCS models with three knots were constructed to explore potential non-linear relationships between NPAR and survival outcomes, with HR curves plotted alongside 95% CIs. All statistical tests were two-sided, and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients

A total of 348 breast cancer (BC) patients were enrolled, including 163 in the metastatic group and 185 in the non-metastatic group. Baseline characteristics are presented in (Table 1). Compared with the non-metastatic group, metastatic patients were significantly older (51 ± 11 vs. 47 ± 9 years, P = 0.003) and had a higher proportion without medical insurance (30.7% vs. 18.4%, P = 0.007). The prevalence of hypertension was higher in the metastatic group (17.2% vs. 7.6%, P = 0.006), whereas diabetes prevalence did not differ significantly (P = 0.671).

In terms of education level, metastatic patients were more likely to have completed only primary or secondary school and less likely to have attained a bachelor’s degree or higher (bachelor’s degree: 13.5% vs. 28.6%, P = 0.002). A higher proportion of metastatic patients resided in rural areas (54.0% vs. 37.3%, P = 0.002). Postmenopausal status was more common in the metastatic group (55.2% vs. 39.5%, P = 0.003). No significant differences were observed in pathological type or histological grade (all P > 0.05). Molecular subtype distribution differed significantly: HR+/HER2 − was the predominant subtype in metastatic patients (54.6% vs. 30.3%), whereas HR+/HER2 + and HR−/HER2 − were more common in the non-metastatic group (P < 0.001).

With respect to laboratory measures, metastatic patients had significantly lower serum albumin levels [38.9 (36.1–41.7) vs. 40.5 (38.6–43.3) g/L, P < 0.001] and lower BMI (22.9 ± 3.3 vs. 23.8 ± 3.2, P = 0.018) compared with the non-metastatic group. NPAR was markedly higher in the metastatic group [15.9 (14.1–18.6) vs. 15.0 (13.5–16.5), P < 0.001], and the proportion of patients in the highest tertile (Q3) was significantly greater (41.7% vs. 25.9%, P = 0.005) (Fig. 2).

Comparison of NPAR, neutrophil percentage (NEUT%), and serum albumin (ALB) levels between metastatic and non-metastatic breast cancer patients. (A) neutrophil percentage (NEUT%); (B) serum albumin (ALB); (C) NPAR (neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio) distributions in non-metastatic and metastatic breast cancer patients. Data are displayed as violin plots, with the median represented by the central horizontal line and the plot width denoting data density. Grey dots indicate individual patient values. Blue: non-metastatic group; purple: metastatic group. ns: not significant; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Association between NPAR and the risk of distant metastasis in BC

Logistic regression analysis (Table 2) demonstrated that, when analyzed as a continuous variable (Z-score standardized), each 1-standard deviation (SD) increase in NPAR was associated with a significantly higher risk of distant metastasis. This association was observed in both the unadjusted model (OR = 1.682, 95% CI: 1.330–2.162, P < 0.001) and the fully adjusted model controlling for demographic, comorbidity, and tumor-related factors (OR = 1.647, 95% CI: 1.275–2.162, P < 0.001).

When stratified by tertiles, patients in the highest NPAR tertile (Q3) had a significantly higher risk of distant metastasis compared with the lowest tertile (Q1) in the fully adjusted model (OR = 1.953, 95% CI: 1.091–3.523, P = 0.024), with a significant dose–response trend (P for trend = 0.024). The intermediate tertile (Q2) showed a slight increase in risk, but this did not reach statistical significance.

Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis further explored the dose–response relationship and revealed a significant overall association between NPAR and metastasis risk (P-overall = 0.001) that was primarily linear in form (P-nonlinear = 0.053) (Fig. 3).

Association between NPAR and risk of distant metastasis in breast cancer patients (restricted cubic spline analysis). Based on a multivariable logistic regression model adjusted for demographic characteristics, comorbidities (age, marital status, menstrual status, education level, hypertension, diabetes, insurance type, residential area, and BMI), and tumor characteristics (pathological type, histological type, and molecular subtype), the relationship between NPAR and the odds of distant metastasis was modeled using a restricted cubic spline (RCS) function. The solid red line represents the fitted odds ratio (OR), with the shaded pink area indicating the 95% confidence interval, and the gray bars represent the distribution histogram of NPAR. The vertical dashed line (Ref = 15.4) marks the reference value. P-overall indicates the significance of the overall association, while P-nonlinear indicates the test for non-linearity.

Subgroup analyses

Fully adjusted logistic regression analyses in predefined subgroups—including insurance status, residence, menopausal status, histological grade, and molecular subtype—demonstrated that the association between higher NPAR and increased metastasis risk was consistent across all subgroups, with no evidence of significant interaction (P for interaction > 0.05 for all). In the overall cohort, elevated NPAR remained significantly associated with a higher metastasis risk (OR = 1.647, 95% CI: 1.275–2.162, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4).

Association between NPAR and risk of distant metastasis across clinical subgroups (multivariable logistic regression forest plot). The association between NPAR (Z-score standardized) and the odds of distant metastasis was analyzed within various clinical subgroups using multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for demographic characteristics (age, marital status, menstrual status, education level, hypertension, diabetes, insurance type, residential area, BMI) and tumor characteristics (pathological type, histological type, molecular subtype). Squares represent the adjusted odds ratios (OR) and horizontal lines denote 95% confidence intervals (CI). The vertical dashed line indicates the reference OR of 1 from the total population. P for interaction reflects the significance of interaction across subgroups.

Diagnostic performance of NPAR for distant metastasis

ROC curve analysis indicated that NPAR had moderate diagnostic value for distinguishing metastatic from non-metastatic BC, with an AUC of 0.619 (95% CI: 0.559–0.678) (Supplementary Fig. 1A). The optimal cutoff value determined by the Youden index was 17.7 (Supplementary Fig. 1B).

Using this threshold, patients were categorized into low (< 17.7) and high (≥ 17.7) NPAR groups. Logistic regression analysis showed that high NPAR was associated with a markedly increased risk of distant metastasis, which remained robust after full adjustment for demographic and tumor-related factors (OR = 4.136, 95% CI: 2.231–7.961, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 1C).

Baseline characteristics and survival of metastatic BC patients by NPAR levels

Among 163 metastatic BC patients, classification by NPAR tertiles (Q1, Q2, Q3) revealed no significant differences in demographics (age, marital status, educational level, residence), tumor characteristics (pathological type, molecular subtype, histological grade), or treatment modalities (surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy) (all P > 0.05).

However, survival outcomes differed significantly: the mortality rate was significantly higher in the high NPAR group (Q3: 52.7%) compared with Q1 (27.8%) and Q2 (31.5%) (P = 0.0153) (Supplementary Table 1). Survival status distribution analysis further illustrated that the number of deaths exceeded the number of survivors in the high NPAR group, whereas the opposite pattern was seen in the low NPAR group (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis

Kaplan–Meier curves revealed significant differences in OS across NPAR tertiles (Log-rank P = 0.036) (Fig. 5). Pairwise comparisons indicated that the high NPAR group had significantly worse survival compared with the low NPAR group (P = 0.036) and the medium NPAR group (P = 0.037), while there was no significant difference between the low and medium groups (P = 0.707).

Median OS was substantially shorter in the high NPAR group (45 months) compared with the low NPAR group (63 months), with the medium NPAR group OS similar to the low NPAR group. Longitudinal analysis of survival rates at key intervals (Supplementary Table 2) showed minimal differences among groups at 12 and 24 months; however, divergence became more pronounced over time. By 36 months, survival in the high NPAR group had fallen to 52.6%, compared with 79.5% and 59.8% in Q1 and Q2, respectively. At 60 months, survival was 27.7% in the high NPAR group, compared with 50.2% and 59.8% in Q1 and Q2.

Comparison of overall survival in metastatic breast cancer patients with different NPAR levels (Kaplan–Meier analysis). Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing overall survival (OS) among metastatic breast cancer patients in the low NPAR group (first tertile), medium NPAR group (second tertile), and high NPAR group (third tertile). Blue line: low NPAR group; yellow line: medium NPAR group; red line: high NPAR group. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. The table below the curves shows the number at risk at various time points.

Independent association between NPAR and patient prognosis

In Cox proportional hazards regression analysis (Table 3), NPAR treated as a continuous variable (Z-score) was significantly associated with poor prognosis. In the unadjusted model, each 1-SD increase in NPAR corresponded to a 60.1% increase in mortality risk (HR = 1.601, 95% CI: 1.225–2.094, P < 0.001). This association remained significant after full adjustment for potential confounders (HR = 1.482, 95% CI: 1.105–1.989, P = 0.009).

When analyzed by tertiles, no significant difference in mortality risk was observed for Q2 compared with Q1, whereas Q3 was associated with more than twice the mortality risk of Q1 in the fully adjusted model (HR = 2.064, 95% CI: 1.022–4.169, P = 0.043). Trend analysis confirmed a significant positive association between NPAR levels and mortality risk (P for trend = 0.036).

RCS analysis showed a significant overall non-linear association between NPAR and mortality risk (P-overall < 0.001; P-nonlinear < 0.001) (Fig. 6).

Association between NPAR and all-cause mortality risk in metastatic breast cancer patients (Cox regression restricted cubic spline analysis). Based on a multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model (Model 3) adjusting for the following variables: demographic characteristics and comorbidities (age, marital status, menstrual status, education level, hypertension, diabetes, insurance type, residential area, BMI), treatment modalities (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy), and tumor characteristics (pathological type, histological type, molecular subtype), the relationship between NPAR and all-cause mortality risk in metastatic breast cancer patients was modeled using a restricted cubic spline (RCS) function. The solid red line represents the fitted hazard ratio (HR), with the light red shaded area indicating the 95% confidence interval, and the gray bars representing the distribution histogram of NPAR. The vertical dashed line (Ref = 15.9) marks the reference NPAR value, while the horizontal dashed line (HR = 1) denotes the null value. P-overall indicates the significance of the overall association, and P-nonlinear indicates the test for non-linearity.

Discussion

This study is the first to systematically establish the clinical value of the neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio (NPAR) as a prognostic factor for both distant metastasis and survival in breast cancer (BC). Our key findings indicate that NPAR is an independent risk factor for distant metastasis in BC (fully adjusted model: OR = 1.647, 95% CI: 1.275–2.162, P < 0.001) and an important predictor of overall survival (OS) in patients with metastatic BC (fully adjusted model: HR = 1.482, 95% CI: 1.105–1.989, P = 0.009). A linear relationship was observed between NPAR and the risk of distant metastasis, whereas NPAR and OS in metastatic BC demonstrated a non-linear association. Patients were stratified using an optimal NPAR cutoff of 17.7, and those with higher NPAR had a 4.136-fold greater risk of distant metastasis compared with those with lower values. Subgroup analyses confirmed that the predictive value of NPAR was consistent across different patient strata.

Our results are consistent with previous large-scale epidemiological studies. Liang et al., based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data, reported a significant association between elevated NPAR and increased BC prevalence21. Similarly, Su et al. not only investigated the association between NPAR and BC prevalence but also examined its relationship with all-cause mortality in BC patients22. They found that higher NPAR was linked to increased BC prevalence (OR = 1.70, 95% CI: 1.12–2.57, P < 0.05) and elevated all-cause mortality (HR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.07–1.12, P < 0.001), with a linear association between NPAR and BC risk (non-linear P = 0.15) and a non-linear relationship with mortality risk (non-linear P < 0.01). In a related study using inflammatory markers to predict BC distant metastases23, a linear relationship between NPAR and metastasis risk was observed. Similar to these reports, our findings highlight that NPAR is associated with both risk of metastasis and differential mortality risk across tertiles, reinforcing its potential applicability in BC prognostication.

Importantly, unlike traditional single inflammatory markers, NPAR integrates information on inflammatory activation (neutrophil percentage) and nutritional–immune status (serum albumin), embodying a systems biology approach to tumor prognosis assessment. Beyond BC, NPAR has shown prognostic relevance in other conditions. For example, Liu et al. identified a positive association between high NPAR and increased risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)24. Ko et al. demonstrated that NPAR ≥ 16.93 in oral cavity cancer patients predicted significantly worse OS and disease-free survival (DFS) and was an independent adverse prognostic factor in multivariate models25. Wang et al. reported that higher NPAR was associated with greater risk of depression26, and studies in colorectal cancer have similarly implicated high NPAR in increased disease incidence27. These findings corroborate our results and suggest that NPAR has broad clinical value across systemic diseases, further reinforcing the biological plausibility of our conclusions.

The observed association between neutrophils and BC metastasis is supported by mechanistic insights from recent neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) research. NETs, web-like DNA–protein complexes released by neutrophils, have been shown to play critical roles in metastatic progression28. In a landmark study published in Cancer Cell (2023), Mousset et al. demonstrated that chemotherapy-induced NETs promote epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) via activation of the TGF-β pathway, fostering therapeutic resistance29. Park et al. further showed that BC cells can directly induce the formation of metastasis-supportive NETs independently of infection8. Using intravital imaging, they visualized NET-like structures surrounding metastatic 4T1 BC cells that had reached the lung, and NETs were also found in clinical samples from patients with triple-negative BC. NETs have been implicated in metastasis promotion through multiple mechanisms: 1.Trapping circulating tumor cells (CTCs): Cools-Lartigue et al. demonstrated that NETs can sequester CTCs30; more recently, Lee et al. reported that NETs recruit innate-like B cells and induce IL-10 production, expanding regulatory T cells and facilitating pre-metastatic niche formation31. 2. Increasing vascular permeability: NETs may degrade endothelial tight junction proteins, thereby enhancing vascular permeability and facilitating tumor cell extravasation32. 3. Activating dormant cancer cells: Albrengues et al. showed that inflammation-induced NETs can awaken dormant cancer cells, potentially explaining late recurrences in BC33. Yang et al. found that aged neutrophils can generate mitochondria-dependent vital NETs that selectively promote BC lung metastases9, potentially explaining the higher metastatic risk seen in elderly BC patients and offering a mechanistic basis for our observed association between age and metastasis.

The role of serum albumin extends far beyond serving as a proxy for nutritional status. Tang et al., in a large prospective cohort study based on NHANES 1999–2018, reported a significant non-linear inverse association between serum albumin levels and cancer mortality34, with the low-albumin group having a 2.03-fold higher risk of cancer-related death after adjustment for confounders (HR = 2.03, 95% CI: 1.73–2.37). Potential anti-tumor mechanisms of albumin include: 1.Antioxidant defense: Albumin has strong antioxidant capacity, removing reactive oxygen species and limiting oxidative stress, which may help preserve normal cell function and inhibit tumor progression35. 2.Immune modulation: A systematic review by Gupta and Lis linked hypoalbuminemia to impaired T-cell function and reduced natural killer cell activity12. 3.Vascular endothelial protection: Albumin maintains endothelial barrier integrity36, reducing vascular permeability and thereby limiting tumor cell extravasation. Additionally, albumin can bind and neutralize various pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6), modulating systemic inflammation20. Arroyo et al. noted that albumin’s anti-inflammatory effects extend to complement system regulation and suppression of endothelial adhesion molecule expression11.

Over the past decade, systemic inflammation markers derived from blood tests have gained wide application in oncologic prognostication. For example, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) predicts short- and long-term outcomes in gastric cancer37; elevated platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) is associated with poor lung cancer prognosis38; and the systemic immune–inflammation index (SII) demonstrates moderate prognostic value for OS and PFS in colorectal cancer39. Compared with established inflammatory or nutritional biomarkers such as NLR, PLR, albumin, and CRP, NPAR integrates both components into a single metric, providing a more comprehensive reflection of systemic inflammation and nutritional depletion and complementing existing indices in breast cancer risk stratification. Biologically, NPAR1 captures inflammatory activation through neutrophil percentage2, reflects nutritional–immune status via serum albumin, and3 represents the homeostatic balance between inflammation and repair through their ratio. Li et al. further confirmed in Cancer Medicine (2025) that the association between NPAR and cancer mortality is independent of traditional prognostic factors14, highlighting its unique biological relevance. Notably, our subgroup analyses revealed that the relationship between NPAR and metastasis risk was consistent across molecular subtypes (all interaction P > 0.05), suggesting that the impact of inflammation–nutrition balance is mechanistically generalizable rather than subtype-specific.

From a translational perspective, NPAR could be incorporated into multivariable prognostic models or risk calculators—alone or in combination with clinicopathologic variables and established biomarkers—to refine individualized risk prediction and guide decision-making. Prospective, multicenter studies with prespecified model-building and external validation, alongside calibration assessment and decision-curve analysis, are warranted before clinical implementation.

Clinically, the optimal cutoff value of 17.7 identified in this study allows stratification of patients into high- and low-risk groups, aiding individualized management. Patients with NPAR ≥ 17.7 had a 4.14-fold higher risk of distant metastasis (OR = 4.136, 95% CI: 2.231–7.961). Stratifying patients by NPAR tertiles may assist clinicians in recognizing progressive increases in metastatic risk and tailoring individualized monitoring or early intervention strategies. We used tertiles to achieve balanced group sizes and to explore potential non-linear risk gradients without imposing arbitrary dichotomous thresholds. In practice, high-NPAR patients could be prioritized for more frequent surveillance visits and imaging reassessments, and considered for early nutritional assessment/support and anti-inflammatory optimization alongside standard oncologic care. At initial diagnosis, high-risk patients should undergo comprehensive imaging, such as whole-body CT, ECT (bone scintigraphy), or PET-CT, to minimize missed diagnoses. In settings with limited diagnostic resources, NPAR can support timely referrals to higher-level centers. In metastatic BC management, NPAR demonstrated strong prognostic stratification: high-NPAR patients had substantially shorter median survival (45 vs. 63 months), warranting consideration of more intensive therapeutic approaches, including combination chemotherapy and earlier use of second-line agents. Given that NPAR reflects the inflammation–nutrition state, nutritional support and anti-inflammatory interventions should be considered in patients with elevated NPAR, along with closer follow-up to detect progression. Our use of RCS modeling to explore non-linear associations between NPAR and outcomes represents a methodological innovation, enabling flexible modeling of complex relationships beyond traditional linear assumptions40. We sequentially adjusted for demographic, comorbidity, treatment, and tumor factors, which strengthens causal inference and highlights the independence of NPAR as a prognostic factor, given the consistent predictive value across all models.

Nevertheless, this study has certain limitations. First, the cohort mainly included Chinese women from southern China, whose genetic background, anthropometric profiles, and disease phenotypes may differ from other populations. Second, unmeasured confounders such as diet, physical activity, and smoking status may influence inflammation–nutrition indices, but relevant data were incomplete. Third, comorbidities and treatment heterogeneity may also have influenced systemic inflammation and nutritional status but were not fully accounted for in the present analysis. Fourth, NPAR was assessed only at baseline; thus, dynamic changes during treatment and their prognostic implications were not captured. In addition, this study did not include a formal power analysis, which may limit the ability to precisely assess statistical power. However, given the observed effect sizes and narrow confidence intervals, the sample size was likely adequate to detect clinically meaningful differences in NPAR. Future research should evaluate the applicability of our findings across multiple centers and diverse populations, control for comorbidities and treatment-related factors, incorporate additional confounders, and explore longitudinal monitoring of NPAR to elucidate the prognostic relevance of temporal changes and its potential value in predicting treatment response.

Conclusion

Using a rigorous epidemiologic design and comprehensive statistical approach, this study is the first to confirm the clinical utility of NPAR as a predictor of both distant metastasis and prognosis in breast cancer. Higher NPAR was associated with increased risk of distant metastasis, with a linear relationship; in metastatic BC, elevated NPAR predicted poorer survival outcomes and exhibited a non-linear relationship with mortality risk. These findings expand our understanding of the role of inflammation–nutrition balance in cancer progression and provide clinicians with an inexpensive, practical, and effective tool for prognostic assessment in BC.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy restrictions, but de-identified data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with approval from the Ethics Committee of Guangxi Medical University Cancer Hospital.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J. Clin. 74 (3), 229–263 (2024).

Siegel, R. L., Giaquinto, A. N., Jemal, A. & Cancer statistics CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 74 (1). (2024).

Cardoso, F. et al. 5th ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 5). Ann. Oncol. 31 (12), 1623–1649 (2020).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2019. Cancer J. Clin. 69 (1), 7–34 (2019).

Gouri, A., Benarba, B., Dekaken, A., Aoures, H. & Benharkat, S. Prediction of late recurrence and distant metastasis in early-stage breast cancer: overview of current and emerging biomarkers. Curr. Drug Targets. 21 (10), 1008–1025 (2020).

Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144 (5), 646–674 (2011).

Grivennikov, S. I., Greten, F. R. & Karin, M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140 (6), 883–899 (2010).

Park, J. et al. Cancer cells induce metastasis-supporting neutrophil extracellular DNA traps. Sci. Transl. Med. 8 (361), 361ra138–361ra138 (2016).

Yang, C. et al. Aged neutrophils form mitochondria-dependent vital NETs to promote breast cancer lung metastasis. J. Immunother. Cancer. 9 (10), e002875 (2021).

Szczerba, B. M. et al. Neutrophils escort Circulating tumour cells to enable cell cycle progression. Nature 566 (7745), 553–557 (2019).

Arroyo, V., García-Martinez, R. & Salvatella, X. Human serum albumin, systemic inflammation, and cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 61 (2), 396–407 (2014).

Gupta, D. & Lis, C. G. Pretreatment serum albumin as a predictor of cancer survival: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr. J. 9 (1), 69 (2010).

McMillan, D. C. The systemic inflammation-based Glasgow prognostic score: a decade of experience in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 39 (5), 534–540 (2013).

Li, X. et al. The association between Neutrophil-Percentage‐to‐Albumin ratio (NPAR) and mortality among individuals with cancer: insights from National health and nutrition examination survey. Cancer Med. 14 (2), e70527 (2025).

Yu, Y. et al. The neutrophil percentage-to‐albumin ratio as a new predictor of all‐cause mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020 (1), 7458451 (2020).

Dong, K., Zheng, Y., Wang, Y. & Guo, Q. Predictive role of neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, and systemic immune-inflammation index for mortality in patients with MASLD. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 30403 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. High neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio can predict occurrence of stroke-associated infection. Front. Neurol. 12, 705790 (2021).

Wang, M. et al. Associations between neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio with all-cause and cause-specific mortality among US cancer survivors: evidence from NHANES 2005–2018. Front. Nutr. 12, 1541609 (2025).

Denk, D. & Greten, F. R. Inflammation: the incubator of the tumor microenvironment. Trends Cancer. 8 (11), 901–914 (2022).

Manolis, A. A., Manolis, T. A., Melita, H., Mikhailidis, D. P. & Manolis, A. S. Low serum albumin: A neglected predictor in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 102, 24–39 (2022).

Liang, H., Pan, K., Wang, J. & Lin, J. Association between neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio and breast cancer in adult women in the US: findings from the NHANES. Front. Nutr. 12. (2025).

Su, Y. et al. Associations of the NPAR index with breast cancer incidence and mortality based on the National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 2001–2018: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Surg. 111 (8), 4972–4985 (2025).

Chen, Z., Gao, H., Cheng, M. & Song, C. A prognostic nutritional Index-Based nomogram to predict breast cancer metastasis: A retrospective cohort validation. Breast Cancer: Targets Therapy 497–510. (2025).

Liu, C-F. & Chien, L-W. Predictive role of Neutrophil-Percentage-to-Albumin ratio (NPAR) in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and advanced liver fibrosis in nondiabetic US adults: evidence from NHANES 2017–2018. Nutrients 15 (8), 1892 (2023).

Ko, C-A. et al. Prognostic value of neutrophil Percentage-to-Albumin ratio in patients with oral cavity cancer. Cancers 14 (19), 4892 (2022).

Wang, L., Liu, L., Liu, X. & Yang, L. The association between neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio (NPAR) and depression among US adults: a cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 21880 (2024).

Qu, C. et al. Exploring the influence of anemia and inflammation indices on colorectal cancer: analysis of the National health and nutrition examination survey from 2011 to 2018. Front. Oncol. 14, 1457886 (2024).

Xu, X. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in breast cancer: roles in metastasis and beyond. J. Cancer. 15 (11), 3272 (2024).

Mousset, A. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps formed during chemotherapy confer treatment resistance via TGF-β activation. Cancer Cell. 41 (4), 757–775 (2023). e10.

Cools-Lartigue, J. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps sequester Circulating tumor cells and promote metastasis. J. Clin. Investig. 123 (8), 3446–3458 (2013).

Lee, W. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote pre-metastatic niche formation in the omentum by expanding innate-like B cells that express IL-10. Cancer cell. 43 (1), 69–85 (2025). e11.

Demers, M. et al. Cancers predispose neutrophils to release extracellular DNA traps that contribute to cancer-associated thrombosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109 (32), 13076–13081 (2012).

Albrengues, J. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps produced during inflammation awaken dormant cancer cells in mice. Science 361 (6409), eaao4227 (2018).

Tang, Q., Li, X. & Sun, C-R. Predictive value of serum albumin levels on cancer survival: a prospective cohort study. Front. Oncol. 14, 1323192 (2024).

Zoanni, B. et al. Novel insights about albumin in cardiovascular diseases: focus on heart failure. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 42 (4), 1113–1128 (2023).

Aldecoa, C., Llau, J. V., Nuvials, X. & Artigas, A. Role of albumin in the preservation of endothelial glycocalyx integrity and the microcirculation: a review. Ann. Intensiv. Care. 10 (1), 85 (2020).

Miyamoto, R. et al. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) predicts short-term and long-term outcomes in gastric cancer patients. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 44 (5), 607–612 (2018).

Ding, N. et al. The prognostic value of PLR in lung cancer, a meta-analysis based on results from a large consecutive cohort. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 34823 (2016).

Chen, J-H. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index for predicting prognosis of colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 23 (34), 6261 (2017).

ANKERST DP. Regression modeling strategies: with Applications, to linear Models, logistic and ordinal Regression, and survival analysis. Biometrics 72, 1006–1009 (2016).

Funding

This work was supported by the WU JIEPING MEDICAL FOUNDATION (WJPMF) under Grant No. 320.6750.2023-18-21, and the Hubei Chen Xiaoping Science and Technology Development Foundation under Grant No. CXPJJH122011-011.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. contributed to the conceptualization, formal analysis, visualization, and drafting of the original manuscript; R.L. contributed to data curation, validation, and methodology development; Z.W. contributed to patient enrollment, data acquisition, and resources management; W.Z. contributed to patient investigation, acquisition of resources, and software utilization; C.L. and Z.L. contributed to data curation, statistical analysis, and validation; H.Z. (corresponding author) played a key role in funding acquisition, project administration, methodology development, supervision of the study, and in the critical review and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval statement

This retrospective study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Guangxi Medical University Cancer Hospital (Approval No.: KY2023868) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for written informed consent was waived by the committee because the study analyzed previously collected and de-identified clinical data and involved minimal risk to participants in accordance with applicable national regulations. Patient confidentiality was strictly protected throughout the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Luo, R., Wu, Z. et al. Association of neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio with distant metastasis and survival outcomes in breast cancer patients: a retrospective and prospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 45456 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28659-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28659-2