Abstract

The diagnosis rate of chronic endometritis (CE), closely associated with infertility, recurrent pregnancy loss, and recurrent implantation failure, remains low in clinical practice. The monocyte percentage (MP) has been identified as a biomarker predicting prognosis in various severe diseases. Although monocytes have been linked to clinical endometritis in animals, their associations with CE in infertile patients remains unclear. This cross-sectional study included patients pathologically diagnosed with CE at a single center in 2021. Demographic data, history of abortion, causes of infertility, Ureaplasma urealyticum infection history, laboratory findings, and histological information were recorded. The correlation between MP and CE was investigated using logistic regression analysis, and subgroup analyses were conducted based on age, gravidity, parity, and follicular phase. The cohort consisted of 631 individuals, including 494 patients with CE, corresponding to a CE prevalence of 78%. Univariate logistic regression analysis revealed an inverse correlation between MP and CE risk (odds ratio [OR] = 0.85; 95% confidence interval [CL], 0.76–0.96; P < 0.01). Multivariate regression after adjusting for all covariates yielded an OR of 0.82 (95% CI 0.71–0.95). Furthermore, the stratified and subgroup analyses yielded consistent results. Sensitivity analyses excluding participants with pathological endometrial changes (OR = 0.83; 95% CI 0.71–0.96), those in the non-follicular phase (OR = 0.78; 95% CI 0.66–0.92), and those with both endometrial abnormality and non-follicular phase status (OR = 0.82; 95% CI 0.7–0.95) further confirmed the correlation between MP and CE risk. MP was significantly associated with CE in infertile participants in models adjusted for all covariates, suggesting that MP may be a valuable parameter for early CE prediction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic endometritis (CE), a subtle pathological condition characterized by abnormal infiltration of plasma cells into the endometrial stroma, primarily manifests as chronic local inflammation. Although patients with CE may exhibit symptoms such as abnormal vaginal discharge, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, dyspareunia, or pelvic pain1, the disease is often underdiagnosed because it is asymptomatic or only mildly symptomatic. However, increasing evidence suggests that CE is closely associated with adverse perinatal and neonatal outcomes, as well as infertility.

It has been reported that approximately 2.8–56.8% of infertile patients2, 14.0–67.5% of recurrent implantation failure (RIF) patients3, and 9.3–67.6% of recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) patients4 are affected by CE. However, the need for an endometrial biopsy and histopathological evaluation limits the identification of patients in clinical practice. The detection of plasma cells primarily relies on laboratory methods such as hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemical (IHC) testing for the plasma cell-specific surface antigen CD138. Positive CD138 expression provides higher sensitivity for diagnosing CE, thereby reducing the risk of misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis and minimizing observer-related variability among pathologists5,6.

Under physiological conditions, the human endometrium is infiltrated by various immune cells types, including macrophages, T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and neutrophils. However, in patients with CE, plasma cells differentiated from B lymphocytes can infiltrate the endometrium. Matteo et al.7 reported reduced endometrial T-cell infiltration in infertile patients with CE compared to those with unexplained infertility. Wang et al.8 found that, in patients with CE, an increased proportion of endometrial Th17 cells and decreased expression of TGF-β and IL-10 disrupted the Th17/Treg balance. In addition, decreased expression of the chemokines CCL4 and MIP-1β, which recruit macrophages and NK cells, has been observed9.

Monocytes are crucial components of the innate immune system. Therefore, the monocyte percentage (MP) has been widely used as a key marker for predicting the prognosis of various pathological conditions associated with immune dysfunction, including malignancies10, chemotherapy response11, deep vein thrombosis in patients with ovarian cancer12, aseptic Lymphocytic-Dominated Vasculitis13, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease14. Monocytes have also been linked to CE in animal models such as dromedary camels15 and cows16. However, to our knowledge, whether MP is associated with CE in humans remains elusive until now. Therefore, we conducted this cross-sectional study to investigate the correlation between MP and CE risk in a cohort of infertile patients.

Methods

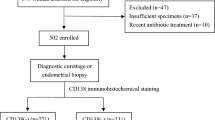

The study included 746 infertile individuals who underwent hysteroscopic endometrial tissue biopsy and CD138 immunohistochemistry(IHC) analysis at the Department of Gynecology, Guangdong Women and Children Hospital, in 2021 for infertility evaluation. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangdong Women and Children Hospital (approval number: 202401137) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.Since this was an anonymous retrospective analysis, the Ethics Committee of Guangdong Women and Children Hospital approved the waiver of informed consent. After excluding patients from the inpatient and gynecology outpatient departments and those with missing monocyte percentage data, 631 participants were finally included, comprising 137 CD138-negative and 494 CD138-positive cases. Figure 1 illustrates the overall participant enrollment process.

Clinical characteristics

General clinical information was collected, including age, gravidity, parity, mode of delivery (vaginal or cesarean section), history of abortion, ectopic pregnancy, causes of infertility, Ureaplasma urealyticum (UU) infection history, laboratory test results, and histological findings related to the endometrial phase, polyps, and hyperplasia.

MP was calculated as the ratio of monocytes to total white blood cells, derived from participants’ laboratory test records. Peripheral MP values were obtained from routine complete blood counts with five-part differential analyses (absolute and percentage counts of lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, and neutrophils) performed at diagnosis using a fully automated hematology analyzer (Mindray, China). Peripheral MP was expressed as a percentage, calculated by dividing the absolute monocyte count by the total leukocyte count and multiplying by 100.

All patients underwent hysteroscopy performed by an experienced surgeon. During the hysteroscopic endometrial biopsy, tissue specimens were collected using biopsy forceps and examined independently by two specialists to evaluate pathological changes in the endometrium. The specimens were immediately fixed in 10% neutral formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin wax, and sectioned into 4-μm-thick slices. These sections were used for H&E staining and IHC analysis. For IHC assays, a commercial kit (CELNOVTE, China) was used. The detection of plasma cells within the endometrial stroma, assessed using CD138 IHC staining, served as the histological diagnostic criterion. After initial low-magnification screening, the number of plasma cells per 400 × high-power field (HPF) (CD138/HPF) was quantified to determine the maximum plasma cell count. In this study, the diagnosis of CE was established by considering both pathological and histological findings from CD138 IHC staining. Specifically, the concurrent presence of plasma cells on H&E staining and ≥ 1 CD138-positive cell per 10 high-power fields in IHC assay was deemed indicative of a positive CE case17,18,19.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R version 3.3.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.R-project.org) and Free Statistics software version 1.7. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Independent t tests and χ2 tests were conducted to analyze differences in quantitative and qualitative variables, respectively. Data imputation was not performed because of the low proportion of missing data.

The correlation between MP and the incidence of CE was examined using six logistic regression models. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for age, gravidity, parity. Model 3 was adjusted for the variables in Model 2 plus endometrial phase (follicular, middle, and luteal). Model 4 was adjusted for the variables in Model 3 plus histological findings (polyp, hyperplastic polyp, and hyperplasia). Model 5 was adjusted for the variables in Model 4 plus reproductive and clinical factors, including induction of labor, medical abortion, artificial abortion, curettage, spontaneous abortion, inevitable abortion, habitual abortion, ectopic pregnancy, primary infertility, chromosomal abnormalities, ovarian factors, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), fallopian tube factors, endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, male factors, unfavorable pregnancy history, and UU infection history. Model 6 was adjusted for the variables in Model 5 plus neutrophil (NEUT), lymphocyte (LYMPH), and platelet (PLT) counts. The participants were also stratified based on age, gravidity, parity, and follicular phase, and the correlation between MP and CE incidence was further investigated within these subgroups. In addition, the following sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the findings: (1) excluding participants with endometrial abnormalities; (2) excluding participants in the non-follicular phase; (3) excluding participants with both endometrial abnormalities and non-follicular phase.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria shown in Fig. 1, this study ultimately included 631 participants, whose demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The cohort comprised infertile patients with a mean age of 32.5 years, and the age range peaked age between 22 and 47 years. CE was diagnosed based on the pathological and histological findings in 494 participants, corresponding to a prevalence of 78%. According to CD138 status, the cohort was divided CD138-positive and CD138-negative groups, with mean ages of 32.4 ± 5.0 and 32.6 ± 4.6 years, respectively. Significant differences in endometrial phase, endometrial hyperplastic polyp, and PLT levels (P < 0.05 for all parameters) were observed between the CD138-negative and CD138-positive groups. A higher proportion of the histological endometrial phase was noted in the CD138-positive group (P < 0.05). CD138-positive individuals exhibited a higher frequency of histological hyperplastic polyps (62 vs. 5, P = 0.003) and higher PLT levels (P = 0.005) compared with CD138-negative individuals.

CE-associated factors

Factors correlated with CE incidence were initially examined in the participant cohort using univariate ordinal regression analysis. As shown in Table 2, the endometrial phase, endometrial hyperplastic polyp, and PLT levels were identified as factors positively associated with CE positivity (P < 0.05 for all parameters).

Correlation of MP with CE incidence

As shown in Table 3, a significant association was observed between MP and the CE incidence. Specifically, the risk of histologically confirmed CE increased as MP levels decreased, with a non-adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 0.85 (95% CI 0.76–0.96). After adjusting for all covariates, the OR was 0.82 (95% CI 0.7–0.95). The statistical results remained robust across all models (Table 3).

Subgroup analyses

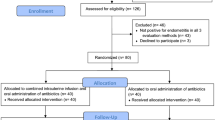

The infertile participants were then divided into subgroups stratified by age, gravidity, parity, and endometrial follicular phase (Fig. 2). The effect size of MP on the presence of CE remained stable across subgroups. Among CE-positive participants, the interactions between MP and age (P = 0.869), parity (P = 0.114), and endometrial follicular phase (P = 0.567) were not significant.

Association between MP and CE positive. Each stratification was adjusted for age, Gravidity, Parity, follicular, middle, luteal, polyp, hyperplasia polyp, hyperplasia, Induction of labor, Medical abortion, artificial, Curettage, Spontaneous abortion, Inevitable, Habitual, Ectopic, Primary, Chromosome, Ovarian, PCOS, Fallopian, Endometriosis, Pelvic inflammatory disease, Male, Disfavorable pregnancy, UU infection histroy, NEUT, LYMPH, PLT.

Sensitivity analyses

The sensitivity analysis findings are summarized in Table 4. When participants with endometrial abnormalities (n = 540) were excluded, MP remained associated with CE (OR = 0.83; 95% CI 0.7–0.96). When non-follicular phase participants (n = 547) were excluded, the OR was 0.78 (95% CI 0.66–0.92). In addition, after excluding participants with both endometrial abnormalities and non-follicular phase (n = 468), the association between MP and CE persisted (OR = 0.82; 95% CI 0.7–0.95).

Discussion

There is currently no early or simple marker of CE, particularly in infertile patients. In this cross-sectional study, the MP was found to be associated with CE in infertile patients for the first time. Specifically, MP levels were inversely correlated with CE incidence in the study population. This association remained significant in the adjusted models. These findings highlight the potential value of MP as a predictive marker for CE development.

Monocytes are crucial components of innate immunity and circulate in the bloodstream. Upon activation by various inflammatory stimuli, they are recruited to sites of inflammation, where they differentiate into dendritic cells and macrophages and secrete superoxide, myeloperoxidase, and cytokines the regulate both local and systemic inflammatory responses20,21. A previous study by Kitaya et al.22 demonstrated aberrant endometrial expression of several B-cell extravasation-associated proinflammatory proteins in patients with CE. The endometrium is infiltrated by various mononuclear immune cells, including macrophages, cytotoxic T (Tc) cells, and NK cells, whose proportions fluctuate during the menstrual cycle23. These immune cells also play essential roles in the physiological processes of reproductive organs, such as trophoblast invasion and mucosal angiogenesis24. According to Cicinelli et al.25, genes involved in cell proliferation, inflam¹mation, and apoptosis—such as those encoding epidermal growth factor (EGF), vascular endothelial growth factors A, B, and C (VEGF-A, -B, -C), cyclins B1 and D3, cell division control protein variants, interferon-γ, interleukin-12, tumor necrosis factor, transforming growth factor β1, BCL-2-associated X protein (BAX) transcript variant alpha—were differentially expressed in the endometrium of women with CE compared with their healthy counterparts.

We propose that this inverse correlation may be attributed to the reciprocal regulation between monocyte and plasma cell functions within the local immune microenvironment of CE. Monocytes, as key components of the innate immune system, are recruited to the endometrium during the early stages of inflammation, where they phagocytose pathogens and secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) to initiate immune responses. As CE progresses, monocytes differentiate into macrophages and further regulate B lymphocyte activation and differentiation through cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β. When B lymphocytes differentiate into plasma cells—the principal effector cells of humoral immunity— producing antibodies against persistent pathogens, the number of recruited monocytes and macrophages may gradually decrease, either due diminished pro-inflammatory signaling or clearance after completing the initial immune activation. This dynamic transition from innate to adaptive immune response may account for the inverse density correlation observed in this study.

MP assay holds unique clinical significance for CE diagnosis in infertile patients and provides supplementary value to the gold-standard plasma cell assay (e.g., CD138 IHC).

Early screening advantage: Plasma cell infiltration typically indicates a relatively advanced stage of chronic inflammation, whereas monocyte elevation may occur earlier (as an initial innate immune response) in subclinical CE. This enables earlier identification of patients at risk of developing overt CE, particularly in asymptomatic infertile women.

Technical accessibility: Unlike plasma cell detection (which requires invasive endometrial biopsy and IHC staining), MP can be measured through routine peripheral blood tests (e.g., complete blood count with differential). It is noninvasive, low cost, and well accepted by patients, facilitating large-scale preliminary screening.

Prognostic implications: Beyond diagnosis, MP may reflect CE activity. Elevated monocyte levels may indicate ongoing inflammation—even when plasma cell density is low—potentially prompting more aggressive anti-inflammatory interventions. Conversely, normalized post-treatment monocyte levels could serve as a non-invasive indicator of therapeutic response, offering an advantage over plasma cell assays, which primarily confirm the presence of chronic inflammation.

Histological analysis for CD138 positivity can greatly facilitate the identification of CE cases. According to the literature, the incidence of CE generally ranges from 3 to 60%26, which can be attributed to the varied diagnostic criteria applied in histological examinations across studies. Higher CE incidences have also been reported. For instance, a single-center study reported a CE incidence of 72% among females with suspected pelvic inflammatory disease27. We observed herein an even higher CE incidence of 78% among infertile patients. This high incidence may result from the introduction of CD138 staining in disease diagnosis or may simply reflect characteristics of the study cohort. Therefore, we speculate that discrepancies in CE incidence among studies can be ascribed to differences in diagnostic criteria and cohort heterogeneity.

Our pathological analysis revealed that 547, 14, and 70 participants were in the follicular, late follicular/early luteal, and luteal phases, respectively, accounting for 86.7%, 2.2%, and 11.1% of the total cohort (P = 0.002). Additionally, the proportion of patients with CE among infertile individuals was higher in the follicular phase (80%) than in the luteal phase (67%). These results are consistent with two previous studies, which reported that 26%17 and 60%28 of participants were in the follicular phase, whereas 18% and 20% were in the luteal phase.

In our analysis, age, cesarean delivery, history of abortion, ectopic pregnancy history, and causes of infertility were not associated with the risk of CE, corroborating the conclusions of Kitaya et al.29,30. No relationship was observed between cervical UU infection before hysteroscopy and CE. Cicinelli et al.31 reported that in patients with CE, the microorganisms isolated from endometrial tissue cultures differed from those identified in endocervical or vaginal swab cultures.

The correlation between endometrial polyps and CE (OR = 2.85; 95% CI 0.66–12.34; P = 0.162) did not reach statistical significant in our study. Kitaya et al.30 failed to detect plasma cell infiltration within specimens from endometrial polyps (EPs). However, some investigations have demonstrated a correlation between CE and EPs32,33. For example, Cicinelli et al.34 reported a higher incidence of CE in females with CD138-positive EPs than in those with CD138-negative EPs (64.1% vs. 30.7%; P < 0.0001). This discrepancy may stem from the small sample size of females with EPs (n = 22) in our study. In our study, there was a high incidence of CE among participants with endometrial polypoid hyperplasia (OR = 3.79; 95% CI 1.49–9.62; P = 0.005). Cicinelli et al. have shown in several of their studies that the presence of endometrial micro-polyps at hysteroscopy may be a reliable feature for diagnosing CE32,33, with the severity of histological abnormalities correlating with hysteroscopic findings34. In a descriptive histological study using endometrial samples from 435 infertile patients, Carvalho et al.35 reported that 70% of vascular alterations in CE corresponded to vessel wall hyaline thickening, showing morphology similar to that of the thick-walled vessels along the vascular axis of EPs. Thus, one possible explanation for this result is that vascular alterations in CE may have influenced the pathologists.

Our study demonstrated a significant inverse correlation between peripheral blood monocyte percentage and endometrial plasma cell density. Although the precise immunological mechanisms within the endometrium require further investigation, several plausible explanations can be proposed based on established immunological principles and observations of chronic inflammation. Future research should include in-depth mechanistic studies using flow cytometry and functional assays, prospective multicenter validation of diagnostic performance, and the establishment of clinical cutoff values. Additionally, exploration of multi-marker panels that combine MP with other biomarkers may further enhance diagnostic and prognostic utility. Critical assessment of the biomarker’s ability to predict treatment response and, crucially, fertility outcomes; investigation of links to specific endometrial pathogens or microbiome profiles; and research into standardization and automation for clinical implementation. We believe these proposed directions provide a clear roadmap for building upon the foundations laid by this retrospective study and ultimately translating the findings into improved clinical management of chronic endometritis in infertile patients.

Limitations

Our study has certain limitations. First, the single-center and cross-sectional nature of this research may limit the generalizability of our findings. Although MP has been correlated with CE incidence, the temporal association between the two remains to be determined and warrants further subtly-designed cohort investigations. Second, the endometrial biopsy specimens we obtained for downstream analyses may not faithfully reflect the actual status of the whole endometrium, although we tried to collect as many first biopsy samples as possible within the defined time frame. Lastly and most importantly, the implications of our findings for pregnancy outcomes warrant further investigation to better clarify their clinical significance and application value.

Conclusions

The results of our study indicate that MP is inversely correlated with CE incidence among infertile patients. Because MP can be readily obtained from routine complete blood count tests, it has potential as an early predictive marker for CE. Future studies ae warranted to elucidate the underlying the mechanisms linking MP and CE.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Greenwood, S. M. & Moran, J. J. Chronic endometritis: morphologic and clinical observations. Obstet Gynecol 58, 176–184 (1981).

Cicinelli, E. et al. Prevalence of chronic endometritis in repeated unexplained implantation failure and the IVF success rate after antibiotic therapy. Human Reprod 30, 323–330 (2015).

McQueen, D. B., Bernardi, L. A. & Stephenson, M. D. Chronic endometritis in women with recurrent early pregnancy loss and/or fetal demise. Fertil Steril 101, 1026–1030 (2014).

Johnson-MacAnanny, E. B. et al. Chronic endometritis is a frequent finding in women with recurrent implantation failure after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril 93, 437–441 (2010).

Ziegler, D. et al. Optimal uterine anatomy and physiology necessary for normal implantation and placentation. Fertil Steril 105, 844–854 (2016).

Park, H. J. et al. Chronic endometritis and infertility. Clin Exp Reprod Med 43, 185–192 (2016).

Matteo, M. et al. Abnormal pattern of lymphocyte subpopulations in the endometrium of infertile women with chronic endometritia. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 61, 322–329 (2009).

Wang, W. J. et al. Endometrial TGF-beta, IL-10, IL-17 and autophagy are dysregulated in women with recurrent implantation failure with chronic endometritis. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol 17, 2 (2019).

Di Pietro, C. et al. Altered transcriptional regulation of cytokines,growth factors, and apoptotic in the endometrium of infertile women with chronic endometritis. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 69, 509–517 (2013).

Zheng, B. et al. Predictive value of monocytes and lymphocytes for short-term neutrophil changes in chemotherapy-induced severe neutropenia in solid tumors. Supportive Care Cancer 28, 1289–1294 (2019).

Wen Ouyang, Yu., Liu, D. D., Zhou, F. & Xie, C. The change in peripheral blood monocyte count: A predictor to make the management of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. J Can Res Ther 14, 565–570 (2018).

Shim, H., Lee, Y. J., Kim, J. H et al. Preoperative laboratory parameters associated with deep vein thrombosis in patients with ovarian cancer: retrospective analysis of 3147 patients in a single institute. J Gynecol Oncol. 35 (2024).

Plummer, D. R. et al. Aseptic lymphocytic-dominated vasculitis-associated lesions scores do not correlate with metal ion levels or unreadable synovial fluid white blood cell counts. J. Arthroplasty 32(4), 1340–1343 (2017).

Lin, C., Li, Y., Lin, P. R et al. Blood monocyte levels predict the risk of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a retrospective case–control study. Sci Rep-Uk. 12(1) (2022).

Hussen, J. et al. Leukocyte populations in peripheral blood of dromedary camels with clinical endometritis. Anim Reprod Sci. 222, 106602 (2020).

Düvel, A. et al. Peripheral blood leukocytes of cows with subclinical endometritis show an altered cellular composition and gene expression. Theriogenology 81(7), 906–917 (2014).

Song, D. et al. Prevalence and confounders of chronic endometritis in premenopausal women with abnormal bleeding or reproductive failure. Reprod. Biomed. Online 36, 78–83 (2018).

Marinaccio, M. et al. Chronic endometritis, a common disease hidden behind endometrial polyps in premenopausal women: First 19 evidence from a case-control study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 26, 1346–1350 (2019).

Volodarsky-Perel, A., Badeghiesh, A., Shrem, G., Steiner, N. & Tulandi, T. Chronic endometritis in fertile and infertile women who underwent hysteroscopic polypectomy. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 27, 1112–1118 (2020).

Yasaka, T., Mantich, N. M., Boxer, L. A. & Baehner, R. L. Functions of human monocyte and lymphocyte subsets obtained by countercurrent centrifugal elutriation: differing functional capacities of human monocyte subsets. J Immunol 127, 1515–1518 (1981).

Kurihara, T., Warr, G., Loy, J. & Bravo, R. Defects in macrophage recruitment and host defense in mice lacking the CCR2 chemokine receptor. J Exp Med 186, 1757–1762 (1997).

Kitaya, K. & Yasuo, T. Aberrant expression of selectin E, CXCL1, and CXCL13 in chronic endometritis. Mod Pathol 23, 1136–1146 (2010).

Kitaya, K., Yamaguchi, T., Yasuo, T., Okubo, T. & Honjo, H. Post-ovulatory rise of endometrial CD16(2) natural killer cells: in situ proliferation of residual cells or selective recruitment from circulating peripheral blood?. J Reprod Immunol 76, 45–53 (2007).

Bulmer, J. N., Williams, P. J. & Lash, G. E. Immune cells in the placental bed. Int J Dev Biol 54, 281–294 (2010).

Cicinelli, E. et al. Altered gene expression encoding cytochines, grow factors and cell cycle regulators in the endometrium of women with chronic endometritis. Diagnostics 11, 471 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Comparison of chronic endometritis as determined by means of diffrernt diagnostic methods in women with and without reproductive failure. Fertil Steril 109, 832–839 (2018).

Paavonen, J. et al. Chlamydial endometritis. J Clin Pathol. 38, 726–732 (1985).

Ryan, E. et al. The menstrual cycle phase impacts the detection of plasma cells and the diagnosis of chronic endometritis in endometrial biopsy specimens. Fertil Steril. 118(4), 787–794 (2022).

Kitaya, K. et al. Local mononuclear cell infiltrates in infertile patients with endometrial macropolyps versus micropolyps. Hum. Reprod. 27, 3474–3480 (2012).

Kuroda, K. et al. Analysis of the therapeutic effects of hysteroscopic polypectomy with and without doxycycline treatment on chronic endometritis with endometrial polyps. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 85, e13392 (2021).

Cicinelli, E. et al. Chronic endometritis, a common disease hidden behind endometrial polyps in premenopausal women: first evidence from a case-control study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 26, 1346–1350 (2019).

Cicinelli, E. et al. Endometrial micropolyps at fluid hysteroscopy suggest the existence of chronic endometritis. Hum Reprod 20, 1386–1389 (2005).

Cicinelli, E. et al. Detection of chronic endometritis at fluid hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 12, 514–518 (2005).

Cicinelli, E. et al. Correspondence between hysteroscopic and histologic findings in women with chronic endometritis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 89, 1061–1065 (2010).

Carvalho, F. M. et al. Functional endometrial polyps in infertile asymptomatic patients: A possible evolution of vascular changes secondary to endometritis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 170, 152–156 (2013).

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L. and X. S. designed the project and wrote the manuscript. M.L. took part in statistical analysis.M.L. and X. S. collected the clinical data. All authors have reviewed and edited the manuscript and have read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, M., Sun, X. Association between monocyte percentage and chronic endometritis among infertile patients: a retrospective study. Sci Rep 15, 44856 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28660-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28660-9