Abstract

Developing high-yielding cultivars requires understanding genetic variation in yield and its components. The study aimed to investigate the genetic structure and inheritance of key traits to identify suitable parents and promising hybrid combinations across F1–F4 generations, using a randomized complete block design with three replications (2019–2023). Data analysis included Griffing Method I, Model 1, general combining ability (GCA) and specific combining ability (SCA) analysis, full diallel variance analysis, Jinks-Hayman diallel hybrid analysis, and heterosis-heterobeltiosis ratios. The Arcanda cultivar showed strong general combining ability, while the Arcanda/Asparuh and Alena/Asparuh hybrid combinations exhibited significant specific combining ability. In the F1–F4 evaluations, Arcanda × Asparuh achieved the highest yields (30.43 g plant−1; 340.40 g 1 m⁻1; 8500.0 and 9151.0 kg ha⁻1), with mean heterosis and heterobeltiosis values of 37.32% and 23.07%, respectively. Alena × Asparuh also performed strongly, particularly in F3 (8459.0 kg ha⁻1), and exhibited high heterosis in F1. High heterosis and heterobeltiosis values, especially for grain yield and thousand kernel weight indicate substantial potential for genetic improvement. To assess the kinship of the parental lines, iPBS-retrotransposon primers were used. The Alena and Arcanda cultivars showed 78% similarity, while the Asparuh cultivar showed 71% similarity to the other parents. In conclusion, Arcanda × Asparuh and Alena × Asparuh consistently combined high yield with genetic stability, making them strong candidates for breeding high-performing barley cultivars. Delaying selection to the later F3–F4 generations increases the accuracy of identifying and stabilizing superior hybrids, thereby maximizing genetic potential and enhancing agricultural productivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) stands as one of the earliest domesticated and fundamental crops of the ancient world1. Barley’s significance in crop production, especially in non-irrigated regions, lies in its versatile role as both a crucial livestock feed and a primary raw material for malt production. Additionally, it is being investigated for its potential applications in human food products, broadening its agricultural and economic importance2. In 2023, barley was cultivated on 3.3 million ha in Türkiye, representing one-third of the total cereal production area (11.5 million ha). With a production of 9.2 million tons, barley is the second most produced cereal after wheat (22 million tons). Historical yields ranged from 2000–2250 kg ha−1 in the early 1990s to 2520 kg ha-1 on average over the past five years (2019–2023)3.

The successful utilization of hybrid cultivars relies on the presence of economically significant heterosis, adequate cross-pollination to ensure cost-effective hybrid seed production, and an efficient, reliable system for developing the female parent4. Furthermore, understanding gene action, inheritance patterns, magnitude of effects, and interactions is essential for designing effective breeding strategies to develop superior genotypes4. Heterosis is an important agricultural phenomenon in which hybrid genotypes exhibit enhanced growth, productivity, earliness, quality, and other traits compared to their parents and its application has expanded to an increasing number of crop species5. In contrast, heterobeltiosis refers to the superiority of hybrids specifically over the parent with the highest trait value.

Identifying genetically superior parents is a crucial prerequisite for developing promising lines6. To design an effective breeding program for developing superior genotypes, it is crucial to understand the mode of inheritance, the magnitude of gene effects, and their interactions7. This knowledge not only aids in selecting the most suitable breeding approach but also guides the development of appropriate varieties for specific conditions. The genetic mechanisms involved in the expression of yield and its components are consistent and reliable in the F1 generation8. Diallel analysis, a potent genetic tool, evaluates combining ability of parental lines’ combining ability and sheds light on complex trait interactions. Through a broad mating scheme with diverse parental lines, it estimates both general and specific combining abilities. This analysis unveils modes of inheritance, genetic architecture, and the significance of yield component traits. Consequently, it informs the selection of parental components for hybridization with scientific precision9,10. To analyze gene effects related to yield and its components, various genetic models have been proposed, particularly second-degree statistical models11. Diallel analysis may be performed out using Jinsk-Hayman and Griffing methods. The Jinks-Hayman method is used to determine heritability, genetic components, and gene effects, while the Griffing method estimates specific combining ability (SCA), general combining ability (GCA), and reciprocal effects. In addition, the methods can be utilized to estimate additive and non-additive effects. The Jinks-Hayman12 and Griffing13 methods are usually performed together for assessment of supporting data14. In combining ability tests, high SCA values indicate gene dominance, while elevated GCA levels suggest additive gene effects. If both GCA and SCA are insignificant, gene epistasis plays a significant role in trait control15. By evaluating their general combining ability (GCA) and specific combining ability (SCA) values across multiple traits, this approach helps identify the most promising candidates16,17.

For the effective identification of genes in barley breeding, crosses are performed between genetically distinct parents that exhibit contrasting phenotypic responses to the trait of interest18. DNA fingerprinting of parental lines and their hybrids, particularly when combined with molecular markers, has proven to be an efficient and powerful technique in breeding programs19. Considering the results of molecular analysis, high-performance hybrids can be obtained by increasing the genetic distance between parental lines20. Inter-primer binding site (iPBS) primers are retrotransposon-based molecular markers that amplify the region between two reverse-aligned retrotransposons, which are bound by the opposite transcriptase marker regions21. This marker system is suitable for any plant species due to the common presence of a tRNA addition as the binding region for the opposite transcriptase in long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons, and it does not require prior sequence information22.

To improve barley genotypes, manipulating genetic variability is essential to enhance adaptation, facilitate the introduction of new genes, and ultimately increase genetic gain in subsequent generations23. The primary goal of barley genetic improvement is to maximize the accumulation of desirable genes within a single genotype or variety24. Heritability in various agricultural crops is a key factor in the success of breeding programs. The investigation of heterosis significantly influences the breeding methodologies for varietal improvement and sheds light on the usefulness of parents in breeding programs25. The performance of hybrids is assessed by their improvement over the mid-parent (heterosis) and the better parent (heterobeltiosis). Taking these factors into account, this study was designed to develop high-yielding barley varieties from diallel progenies, aiming to enhance the understanding of the genetic mechanisms governing trait inheritance. Therefore, this present study was aimed to: 1) evaluate yield and its components across successive generations (F1 to F4), 2) discover genetic structures within progeny (F1, F2 and F3), 3) identification of superior parental combinations based on GCA and SCA for yield traits, 4) assessment of the heterosis, and heterobeltiosis of yield and yield components, and 5) determining genetic diversity between parental varieties with iPBS markers.

Materials and methods

Field trails and investigated traits

A field trial was carried out at the experimental site in the Gumusova District, Duzce Province, Türkiye (40°50′23.2" N, 30°58′24.3" E; elevation 160 m). The study was carried out from October 2019 to July 2023. In the study, three two-rowed barley varieties (Hordeum vulgare L.), namely Arcanda, Alena, and Asparuh, were used as parents and reciprocally hybridized based on a diallel cross using Griffing’s Method I, Model 1. The three parent varieties and their resulting six hybrids (Arcanda/Alena, Arcanda/Asparuh, Alena/Arcanda, Alena/Asparuh, Asparuh/Arcanda, Asparuh/Alena) were grown in a randomized complete block design with three replications. The seeds of F1 progenies and their parents were sown in 2 rows, each 1 m long, spaced 30 cm apart, with an intra-row spacing of 10 cm, in early November 2019. The seeds of F2 progenies and their parents were sown in 2 rows, 1 m long, spaced 20 cm apart early November 2020. The seeds of F3 progenies and their parents were sown in 3 rows, each 5 m long, spaced 20 cm apart in early November 2021, and F4 progenies and their parents were sown in 5 rows, each 5 m long, spaced 20 cm apart in early November 2022 (Fig. 1).

Agronomic practices from sowing to harvest including fertilization and weed control were applied for the experiment for each year (2019–2023). Ten main plants were selected randomly from each replication for parents and F1s to F4s progenies to take measure of the investigated traits: spike length (SL), number of grains per spike (NGS), and grain weight per spike (GWS). Thousand kernel weight (TKW) was calculated based on the average weight of 4 randomly selected samples of 100 kernels from each plot. Grain yield (GY) was calculated as grams (g) per plant in the F1 generation, grams (g) per 1 m row in the F2 generation, and as kilogram (kg) per hectare (ha) in the F3 and F4 generations.

Molecular analysis

In this study, genetic variation among the three barley varieties was assessed using iPBS markers. iPBS markers were chosen because they provide genome-wide coverage by targeting retrotransposon insertion sites, exhibit high levels of polymorphism in barley and other cereals, and do not require prior sequence information. These properties make them a reliable and representative tool for evaluating genetic diversity. Ten iPBS-retrotransposon primers were used to assess the genetic similarity among the parents. DNA isolation was carried out using the CTAB protocol26. The DNA concentration of the genotypes was measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and diluted to 5 ng/μL. The samples were stored at − 20 °C until polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. The details of the iPBS-retrotransposon primers are provided in Table 1. Genomic DNA extracted from the barley genotypes and the iPBS-retrotransposon primers were used for PCR analysis. The PCR reaction mixture consisted of 10 × PCR buffer (1 μL), MgCl2 (1 μL), dNTP (1 μL), primer (1.5 μL), Taq polymerase (0.15 μL), DNA (2.5 μL), and ddH2O (2.85 μL). The amplification protocol was as follows: 3 min at 95 °C, 15 s at 95 °C, 1 min at 50 °C, 1 min at 68 °C, followed by a final extension for 5 min at 72 °C with 30 cycles, and the reaction was then stored at 4 °C27. PCR products were analyzed by 1.5% (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis using 0.5 × Tris–Borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV light. To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the molecular data, the entire iPBS-retrotransposon marker analysis was conducted using two independent biological replicates for each parental genotype (Arcanda, Alena, and Asparuh). The resulting amplification profiles were highly consistent across these replicates. Furthermore, to minimize subjective bias in data interpretation, the DNA banding patterns on all agarose gels were scored independently by two of the authors (H.G. and M.F.C.). Any discrepancies in scoring between the two evaluators were resolved by a joint re-examination of the gel image until a consensus was reached. The representative gel images presented in this manuscript were selected from this verified dataset. The original, full-length, and uncropped gel images for all primers and replicates are provided in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Figure S1) to ensure full data transparency.

Statistical analysis

The mean data were compared using the least significant difference (LSD) test at significance level of P ≤ 0.05. The heterosis (Ht) and heterobeltiosis (Hb) were calculated according to the method suggested by Chang and Smith28 and Fonseca and Patterson29. Meanwhile, the estimates of combining ability variances and effects were calculated using Griffing’s Method I, Model I13. Estimating the components of variation and determining the nature of gene effects in the studied traits were performed using the diallel biometric approach as outlined by Jinks and Hayman12. The data obtained from the trials were analyzed using the TARPOPGEN statistical package30.

The resulting DNA banding patterns were analyzed using TotalLab TL120 software (TotalLab Ltd., Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK). For the iPBS amplification products, each locus was scored in a binary format, where “1” indicated the presence and “0” the absence of a band. After that using this matrix, a dendrogram was generated to illustrate the similarities among the barley genotypes by applying the Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Average (UPGMA) in NTSYSpc 2.21q software31. The polymorphism information content (PIC) for each iPBS-retrotransposon primer used in the study was calculated according to the formula PIC = 1 − ΣPi2, where Pi represents the frequency of the ith allele in the three barley genotypes investigated32.

Results

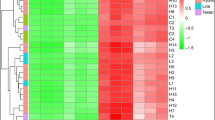

The variance analysis for all the investigated traits is given in Table 2, with agronomic traits presented in Fig. 2 and the high-performing barley crosses per generation for grain yield (GY) and yield components summarized in Table 3. Genetic parameters are given in Table 4, and the GCA effects of parents, SCA of hybrids, and Ht and Hb values are presented in Figs. 3, 4 and 5, respectively.

Agronomic traits

Significant differences among genotypes were found (Table 2). A comprehensive evaluation was conducted to assess various traits across four generations (F1–F4) of barley crosses involving the parental genotypes Arcanda, Alena, and Asparuh.

Arcanda demonstrated consistently superior performance across traits, reinforcing its value as a breeding parent, while Alena excelled in GWS and Asparuh contributed genetic diversity with progressive improvement over generations. Among parents, Arcanda generally outperformed Alena and Asparuh. In SL, Arcanda/Asparuh and Alena/Asparuh ranked highest in early generations and maintained competitive values in later ones. NGS improved in the early generations, with Asparuh/Alena and Alena emerging as top performers by F₄. For GWS, Arcanda/Asparuh and Alena/Asparuh consistently ranked among the best, while Arcanda/Alena achieved notable gains in the final generation. TKW was led by Arcanda/Asparuh and Asparuh/Arcanda in F₁, with Alena/Arcanda and Asparuh/Arcanda dominating in F₄. In terms of grain yield, Arcanda/Asparuh achieved 30.43 g plant⁻1 in F₁, 340.40 g 1 m⁻1 in F₂, 8500.0 kg ha⁻1 in F₃, and 9151.0 kg ha⁻1 in F₄, consistently ranking first. Alena/Asparuh also maintained strong performance, reaching 8459.0 kg ha⁻1 in F₃ (Fig. 2; Table 3).

SL: Spike length, NGS: Number of grains per spike, GWS: Grain weight per spike, TKW: Thousand kernel weight, GY: Grain yield.

Genetic parameters

In this study, the genetic parameters of SL, NGS, GWS, TKW, and GY were examined across F1, F2, and F3 generations in barley. The analysis provided comprehensive insights into the genetic control and variation of these traits across different generations (Table 4).

Environmental effects (E) on SL decreased markedly from F₁ to F₃, suggesting a diminishing environmental influence over successive generations. For NGS, environmental influence peaked in F₂ before declining in F₃. GWS showed minimal environmental influence across all generations. TKW experienced a temporary increase in environmental influence in F₂, followed by a slight reduction in F₃. In contrast, GY showed a substantial rise in environmental influence by F₃, indicating greater sensitivity to environmental conditions compared with other traits.

The additive genetic variance (D) reflects the proportion of total genetic variance attributable to the additive effects of alleles. For SL, additive variance increased from F₁ to F₂ before declining in F₃, indicating a reduced contribution of additive effects in later generations. NGS displayed high additive variance in F₁, which declined steadily by F₃. GWS exhibited consistently low additive variance across all generations. In TKW, additive variance fluctuated, with a marked increase in F₃. GY showed the most substantial rise in additive variance by F₃, suggesting that selection in later generations could effectively capture and exploit these additive effects for yield improvement.

Frequencies of dominant to recessive alleles in the parental population decreased for SL from F₁ to F₃, indicating a reduction in dominance influence across generations. NGS also showed a marked decline, while GWS remained relatively stable with minor changes. TKW displayed fluctuating values, alternating between negative and positive, suggesting shifts in dominant direction. In contrast, GY showed a substantial increase by F₃, reflecting the persistence of dominance effects in yield traits despite a general decline in heterosis for other characteristics. Dominance effects (H₁ and H₂) quantify the contribution of dominant genetic factors to trait expression. Both parameters indicated declined across generations for SL, NGS, GWS, and TKW, indicating a reduction in dominance influence as selection progressed. In early generations, dominance effects were more pronounced, particularly for yield-related traits, but diminished in later generations as additive effects became more influential. For GY, dominance effects remained relatively high compared with other traits, suggesting that heterotic potential persisted for yield even when it declined for spike-related traits.

The difference between additive and dominance variance (D − H₁) reflects the balance between these two genetic components. Across most traits, values indicated a decline in dominance influence over successive generations. For SL and NGS, early generations showed a stronger dominance component, which progressively diminished in later generations. GWS maintained a small but consistent dominance effect throughout. TKW exhibited marked dominance influence initially, which was substantially reduced by the final generation. Similarly, GY displayed strong dominance effects in the early generation, but these declined sharply over time, suggesting a shift toward additive genetic control in later cycles of selection. The average degree of dominance (H₁/D)1/2 describes the relative contribution of dominance compared with additive effects, where values greater than 1 indicate overdominance and values less than 1 indicate partial dominance. Across traits, SL and NGS exhibited strong overdominance in early generations, which declined by F₃. GWS fluctuated but maintained dominance influence across generations. TKW showed reduced dominance effects in later generations. GY displayed pronounced overdominance in F₁, which diminished substantially by F₃, indicating a shift toward additive genetic control as selection advanced.

Proportion of genes with positive and negative effects (H2/4H1) reflects the balance between dominant and recessive alleles in the parental population. Values for most traits remained relatively stable across generations, although SL and GY showed a gradual decline by F₃, indicating a shift in allele distribution. TKW displayed an increase over time, suggesting a growing contribution of dominant alleles. These patterns provide insights into population genetic structure, supporting informed selection to maintain favorable allele combinations.

Dominant alleles (KD) represent the frequency or proportion of dominant alleles in the population, while recessive alleles (KR) represent the frequency or proportion of recessive alleles. A KD/KR ratio greater than one indicates a predominance of dominant alleles, favoring the expression and selection of dominant traits. Across traits, SL and GY showed an increasing KD/KR ratio over generations, suggesting a shift toward greater dominance. NGS maintained consistently high ratios, whereas GWS exhibited moderate fluctuations. TKW displayed lower ratios, indicating a stronger influence of recessive alleles. These patterns highlight that while dominance effects remain important for certain traits, additive gene effects become increasingly relevant for sustainable genetic improvement.

The dominance effect (h2) represents the proportion of total phenotypic variance attributable to dominance variance. Across traits, dominance effects were generally strong in the early generation (F₁) but declined progressively in later generations, indicating a shift toward additive genetic control. SL showed moderate dominance influence, peaking in the intermediate generation before decreasing. NGS and GY exhibited particularly high dominance in F₁, followed by sharp reductions in subsequent generations. GWS maintained low dominance effects throughout, whereas TKW displayed high initial dominance that diminished over time. This overall trend highlights the decreasing role of dominance effects and the increasing relevance of additive genetic variance for sustained breeding progress.

Narrow-sense heritability (h2n) reflects the proportion of phenotypic variance attributable to additive gene effects, which are critical for effective selection in breeding programs. Across traits, h2n generally increased over successive generations, indicating a growing contribution of additive variance to trait expression. SL and NGS maintained moderate to high h2n values, while GWS, TKW, and GY showed strong additive genetic control, particularly in later generations. Broad-sense heritability (H2b), which accounts for additive, dominance, and epistatic effects, also increased for most traits over generations, suggesting an overall strengthening of genetic influence. While some traits, such as GWS and TKW, displayed fluctuations in H2b, GY exhibited a marked rise in later generations, highlighting the increasing stability of genetic control. These patterns suggest that, as breeding cycles progressed, additive effects became more prominent, supporting the potential for sustained genetic gains through selection.

General combining and specific combining

GCA reflects the average performance of a parent based on its additive genetic contribution to its offspring. High GCA values indicate that a parent consistently transmits favorable alleles, making it ideal for breeding programs focused on additive genetic improvement. For SL, GCA values were non-significant in F1 but significant in F2 and F3, indicating strong additive genetic control. NGS showed significant GCA values in F1 and F2, but non-significant in F3, suggesting reduced additive effects. For GWS, GCA values were non-significant in F1 and F3 but significant in F2, showing variability in genetic control. TKW had consistently high GCA values across generations, highlighting strong and consistent additive effects. GY had strong GCA values across all generations, indicating robust additive genetic control.

GCA values reflect the additive genetic contribution of parents to their offspring. Arcanda consistently showed positive GCA values, indicating strong additive contributions across multiple traits and generations. Significant GCA values were found for Arcanda in F2 and F3 for SL (Fig. 3a), in F1 and F2 for NGS (Fig. 3b), in F2 and F3 for GWS (Fig. 3c), in F1 and F2 for TKW (Fig. 3d), and in F2 and F3 for GY (Fig. 3e). Alena exhibited high positive GCA values, especially in early generations for NGS and SL. Significant GCA values for Alena were in F1 and F2 for SL (Fig. 3a), in F1 for NGS (Fig. 3b), in F2 for GWS (Fig. 3c), in F1 for TKW (Fig. 3d), and in F3 for GY (Fig. 3e). In contrast, Asparuh often had negative GCA values, indicating a less favorable additive genetic contribution. Negative GCA values for Asparuh were found in F1 and F2 for SL (Fig. 3a), in F1 and F2 for NGS (Fig. 3b), in F1 and F2 for GWS (Fig. 3c), in F2 for TKW (Fig. 3d), and in F2 and F3 for GY (Fig. 3e).

SCA reflects the performance of specific cross combinations based on non-additive gene effects, such as dominance and epistasis. High SCA values indicate that combinations of parents produce superior offspring due to these non-additive interactions. For SL, SCA values were significant across generations, indicating that specific parent combinations result in superior SL due to non-additive gene effects. NGS had high SCA values, suggesting the importance of non-additive effects. For GWS, SCA values were non-significant in the F1 but significant in the F2 and F3, showing the importance of non-additive effects in these generations. TKW exhibited high SCA values, particularly in the F1 generation, indicating the crucial role of non-additive effects. GY had significant SCA values across generations, highlighting the importance of non-additive effects in improving yield.

The specific combining ability (SCA) values for various traits highlight the significance of non-additive gene effects across different crosses. For SL, the Arcanda/Asparuh cross consistently showed positive SCA values in F2 and F3, indicating beneficial non-additive effects, while the Arcanda/Alena cross had negative SCA values (Fig. 4a). For NGS, the Arcanda/Asparuh cross had significant positive SCA values in F1, F2, and F3, reflecting the importance of non-additive effects (Fig. 4b). The Alena/Asparuh cross also showed strong positive SCA values in F1 and F2 (Fig. 4b). For GWS, the Arcanda/Asparuh cross had positive SCA values in F2 and F3, while the Alena/Asparuh cross showed a positive SCA value in F2 (Fig. 4c). For TKW, the Arcanda/Asparuh cross demonstrated strong positive SCA values in F1 and F2, and the Arcanda/Alena cross had a positive SCA value in F2 (Fig. 4d). Regarding GY, the Arcanda/Alena cross had high positive SCA values in F1, F2, and F3, emphasizing the critical role of non-additive effects in enhancing yield (Fig. 4e).

The analysis of GCA and SCA values provides insights into genetic control and breeding potential. High GCA values indicate strong additive effects, making certain parents, like Arcanda, ideal for breeding programs. High SCA values highlight the significance of non-additive effects, suggesting specific parent combinations, such as Arcanda/Alena and Arcanda/Asparuh, can produce superior offspring.

Reciprocal effects

Reciprocal effects significantly influenced various traits across generations. For SL, the effects increased over time, indicating a growing influence. NGS showed significant effects initially but diminished in later generations. GWS had significant effects in early and late generations, but not in the middle generation. TKW showed strong effects across all generations, while GY had highly significant effects throughout. These results suggest that the direction of crossing significantly impacts trait expression, highlighting the importance of maternal and paternal contributions.

Heterosis (Ht) and heterobeltiosis (Hb)

The data analysis across all generations (F1–F4) highlights significant trends in Ht and Hb for various barley crosses and traits. For SL, the Alena/Asparuh cross showed strong performance throughout, particularly F2 with Ht of 20.30% and Hb of 16.22%, and in F4 with Ht of 7.49% and Hb of %4.09, while Arcanda/Asparuh exhibited notable results in F4 with Ht of 14.02% and Hb of 6.41% (Fig. 5a). In terms of NGS, Alena/Asparuh excelled across generations, with peak performance in F3 (Ht: 39.60%, Hb: 32.43%) and consistent results in F4 (Ht: 9.53%, Hb: 4.83%), while Asparuh/Alena showed robust performance in F4 with Ht of 11.64% and Hb of 6.72% (Fig. 5b). For GWS, Arcanda/Asparuh demonstrated high Ht in F4 (28.16%) and Hb (18.34%), and Asparuh/Alena also showed significant Ht (52.24%) and Hb (27.32%) in F4, indicating strong hybrid vigor (Fig. 5c). TKW showed Arcanda/Asparuh achieved high values in F1 with Ht of 19.80% and Hb of 13.45%, although TKW results are more variable across generations (Fig. 5d). For GY, Arcanda/Asparuh stands out in F1 with exceptional Ht (168.96%) and Hb (131.30%), while Asparuh/Alena consistently performs well, particularly in F4 with Ht of 46.10% and Hb of 31.44%, and Alena/Asparuh shows significant results in F3 (Ht: 33.20%, Hb: 15.30%) (Fig. 5e).

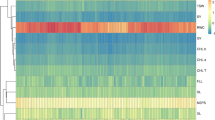

Molecular analysis

iPBS-retrotransposon markers were used to determine genetic diversity of the barley genotypes used as parents in current study. Ten iPBS-retrotransposon were produced 70 polymorphic alleles with 7 alleles average, and the most polymorphic one was primer 2257 with 0.543 PIC value and 14 allele numbers. The average PIC value was 0.39, while the polymorphism rate of the primers was 59.93% (Table 5). The gel pictures of the primers iPBS 2246 and iPBS 2257 are shown in Fig. 6.

Representative Gel pictures of the primers iPBS 2246 and iPBS 2257. Lane 1: DNA ladder (100 bp). Lanes 2–4: PCR products of Asparuh, Alena, and Arcanda genotypes, respectively. The genotype names are indicated above each lane. These images are representative examples selected from two independent biological replicates, which showed consistent banding patterns. The full, uncropped gel images are available in Supplementary Figure S1.

A dendrogram was also produced using alleles obtained from iPBS-retrotransposon primers (Fig. 7). According to the dendrogram, Arcanda and Alena were found more like each other (78%) than Asparuh (71%).

Discussion

This research investigated agronomic traits, genetic parameters, heterosis and heterobeltiosis across F1–F4 generations using 3 × 3 full-diallel analysis. This approach evaluated genetic variation and inheritance patterns, providing insights into genetic architecture and improvement potential in barley cultivars. Differences among the genotypes (F1–F4) for the traits examined were statistically significant, consistent with the findings of Eshghi and Akhundova33, Madić et al.34, Metwali35, and Bouchetat and Aissat23. The mean values for all traits measured in the hybrids (F1–F4 generations) were greater than the average values recorded in their parents, except for the TKW in the F3 generation. This aligns with findings by Eshghi and Akhundova33 for GY, and Bouchetat and Aissat23 for PH and GY. The variation between hybrid and parental performance can be attributed to the combined effects of genetic factors and environmental influences, which together influence phenotypic performance, leading to either the enhancement or reduction of the trait.

The average trait values across generations (F1–F4) were analyzed to understand the progression and stability of these traits in the hybrids. For SL, the averages were 12.11 cm in F1, 9.41 cm in F2, 9.19 cm in F3, and 10.58 cm in F4, indicating an initial decline followed by an increase. NGS showed an initial decrease from 32.02 in F1 to 26.06 in F3, followed by an increase to 31.59 in F4. GWS averaged 1.981 g in F1, 1.364 g in F2, 1.206 g in F3, and 1.874 g in F4, demonstrating improvement after F3. TKW values were 44.94 g in F1, 40.84 g in F2, 37.49 g in F3, and 43.52 g in F4, highlighting a decrease in F2 and F3 before increasing in F4. GY showed substantial improvement, increasing from 19.18 g plant−1 in F1 to 7833.10 kg ha−1 in F3, and stabilizing at 8112.00 kg ha−1 in F4. These genetic differences align with findings from related agronomic studies36,37.

The analysis of gene effects using the Griffing method13 revealed significant contributions from both GCA and SCA effects across the majority of evaluated traits. The GCA effects were significant for all traits, except for SL in the F1 generation, NGS in the F3 generation, and GWS in the F1 and F3 generations. Similarly, the SCA effects were significant for all traits and generations, except for GWS in the F1 generation. In agreement with these findings, Madić et al.34 and Zhang et al.38 reported that the analysis of variance of combining abilities in barley revealed significant GCA and SCA variances for all traits. Furthermore, Panwar and Sharma (2019) found that GCA was significant for all traits in barley, while SCA effects were significant for all traits except for days to 75% maturity. These findings indicate that both additive and non-additive gene effects should be considered in breeding programs, and that exploiting high SCA effects to develop superior hybrids can be particularly effective when non-additive variance predominates.

In the F1, F2, and F3 generations, the GCA/SCA variance ratio was found to be less than one for all the characters studied, except SL in the F2 generation and TKW in the F2 and F3 generations. The GCA/SCA ratio provides insight into the relative importance of additive versus non-additive effects. Similar results were obtained by Amer et al.39, Madić et al.34, Rohman et al.24. In previous barley gene action studies, trait transmission has been demonstrated that non-additive effects are more essential than additive effects, notably for one trait, showing predominance of dominance-type gene action17,40. These results imply that breeding programs should focus on exploiting heterosis and selecting superior hybrid combinations in early generations for traits under strong non-additive control, while applying additive-based selection for traits such as TKW where GCA effects are more prominent.

Arcanda demonstrated positive and significant GCA effects for SL, GWS, and TKW in F₂ and F₃, as well as for NGS and GY in F₁ and F₂, underscoring its value as an effective general combiner for these traits. Alena exhibited negative GCA effects in F₂ for SL, TKW, and GY, but displayed positive effects in F₃ for TKW and GY. Asparuh consistently demonstrated negative GCA effects for NGS, GY, and TKW, as well as for SL and GWS except in F₁. Arcanda is the best genotype for breeding these traits. Alena/Asparuh had positive SCA for SL and NGS in all generations, while Arcanda/Asparuh was positive for these traits in F2 and F3. Both crosses showed positive SCA for GWS in F2 and F3. For TKW, Arcanda/Asparuh and Asparuh/Alena were positive in F1, and Arcanda/Alena, Arcanda/Asparuh, and Asparuh/Alena in F3. For GY, Arcanda/Asparuh and Alena/Asparuh had positive SCA in all generations. Negative SCA values were noted for Asparuh/Arcanda in multiple traits. Arcanda/Asparuh and Alena/Asparuh hybrids consistently showed positive SCA across traits and generations. Considering all traits and generations, Arcanda/Asparuh and Alena/Asparuh consistently expressed positive SCA effects, reinforcing their potential as elite parental combinations in hybrid-oriented breeding programs.

These results are validated by the Jinks-Hayman model12, which applies to all evaluated parameters. The analysis of genetic parameters across the F1, F2, and F3 generations revealed that the additive effect (D) was not significant for any of the traits studied. In contrast, the dominance components (H1 and H2) were positive and non-significant for all traits. Notably, the value of H1 was consistently higher than D, indicating a greater influence of over-dominance effects compared to additive effects. This observation was further confirmed by the net dominance component (h2), which was positive and non-significant for all traits except for GWS in the F1 generation. Additionally, the average degree of dominance (H1/D)1/2 was higher than unity for all traits, suggesting the presence of over-dominance gene effects. These findings highlight the significance of non-additive gene effects, particularly over-dominance, in the inheritance of the traits studied.

Heritability analysis across F1, F2, and F3 generations showed higher H2b than h2n for all traits. For SL, H2b was higher compared to h2n. The NGS also had higher H2b heritability. GWS showed moderate heritability with H2b values higher than h2n. TKW had the highest heritability among the traits, with H2b values significantly higher than h2n. GY demonstrated high H2b heritability but lower h2n values. The results indicate a strong genetic influence but suggest limited effectiveness for selective breeding due to the relatively low additive genetic variance.

Heterosis analysis revealed consistently positive mid-parent heterosis (Ht) for most traits across generations, with variable heterobeltiosis (Hb) responses depending on the trait and cross. Grain yield (GY) exhibited the most pronounced heterotic advantage, particularly in Arcanda/Asparuh (Ht = 168.96%, Hb = 131.30% in F₁) and Alena/Asparuh (Ht = 198.39%, Hb = 181.97% in F₁), sustaining high heterosis through later generations. GWS also showed strong positive heterotic expression, notably in Arcanda/Asparuh and Alena/Asparuh, with Ht values exceeding 20% in multiple generations. In contrast, TKW displayed lower and sometimes negative Hb in F₃, indicating a reduced potential for hybrid superiority in certain cycles. For SL and NGS, heterosis was moderate, with Alena/Asparuh and Arcanda/Asparuh frequently achieving above-average performance. These results highlight Arcanda/Asparuh and Alena/Asparuh as elite combinations capable of exploiting non-additive gene action to achieve superior hybrid performance, particularly for GY and GWS. The sustained heterotic performance across generations underscores their potential for integration into long-term breeding programs aimed at maximizing yield gains. Previous studies by Pesaraklu et al.17 and Moustafa et al.41 reported high heterotic responses for grain yield in barley. The genetic diversity of the barley genotypes used in the current study was revealed by iPBS-retrotransposon primers. Ten primers generated 70 polymorphic alleles and similarity of the barley genotypes were determined which is crucial to cross diverse genotypes to expand genetic base. Arcanda and Alena were more similar to each other with a 78% similarity and 22% dissimilarity which is still well enough to obtain variation via crossing each other. Asparuh was relatively more distinct to Arcanda and Alena with 29% dissimilarity percentage. Our results provide direct evidence for the principle that parental genetic distance can drive heterotic performance. The iPBS marker analysis revealed that the Asparuh cultivar was the most genetically distinct parent, sharing only 71% similarity with Arcanda and Alena (Fig. 7). Correspondingly, the two most superior hybrid combinations for grain yield heterosis were Arcanda × Asparuh and Alena × Asparuh (Fig. 5e). This strong correlation between the molecular diversity data and the agronomic performance data underscores the utility of marker-assisted parental selection for maximizing heterosis in barley breeding programs. Previous studies by Ahmed et al.42, Güngör et al.43, and Yeken et al.44 reported the recognition of substantial genetic variability among the genotypes underscores the tactical benefit of crossing genetically diverse individuals to improve segregation and selection methods. Moreover, underscore the potential of iPBS and SCoT markers as a cost-effective and time-efficient instrument for accelerating the development of novel hybrid combinations in plant breeding.

While this study provides valuable insights into the genetic control of yield components in barley, its limitations must be acknowledged to contextualize the findings. First, as suggested by the reviewer, the research was conducted at a single experimental site in Duzce, Türkiye. This approach, while allowing for detailed generational analysis, restricts the assessment of genotype × environment (G × E) interactions, which are known to significantly influence quantitative traits like grain yield. Second, the parental pool was limited to three two-rowed barley cultivars. Although these parents were selected to provide genetic contrast, a broader set of germplasms would be necessary to generalize our conclusions about combining ability and heterosis across a wider range of barley genetic backgrounds. Consequently, the performance of the identified superior crosses, such as Arcanda/Asparuh, should be validated in multi-environment and multi-year trials before their widespread recommendation. Future research should therefore focus on evaluating these promising hybrid combinations across diverse agro-ecological zones and expanding the diallel analysis to include a larger, more diverse panel of parental lines. Such studies, potentially integrated with genomic selection tools, would further refine the identification of loci underlying key agronomic traits and accelerate the development of broadly adapted, high-yielding barley cultivars. Despite the limitations noted, this study advances understanding of the genetic architecture underlying key agronomic traits in barley, clarifying the contrasting contributions of additive and non-additive gene action across generations. The identification of high-potential parental combinations, particularly Arcanda/Asparuh and Alena/Asparuh, provides a strong foundation for developing hybrid-focused breeding strategies aimed at improving grain yield and associated traits. These outcomes offer practical guidance for future breeding programs by promoting the targeted exploitation of heterosis for traits governed by non-additive effects, while applying additive-based selection for traits where additive variance predominates.

Conclusions

Crossbreeding in barley led to significant variation in agronomic traits, highlighting the importance of genetic studies. Among the crosses, Arcanda/Asparuh proved to be the most promising, exhibiting superior grain yield along with consistently high values for spike length, grain weight per spike, and thousand-kernel weight across generations. Arcanda proved to be an excellent general combiner, while both Arcanda/Asparuh and Alena/Asparuh exhibited superior specific combining ability for multiple traits. Selection is recommended in later generations (F₃–F₄) to stabilize desirable characteristics. Significant heterosis and heterobeltiosis for grain yield and thousand kernel weight confirm the potential for genetic improvement through hybrid breeding. Genetic diversity revealed by iPBS-retrotransposon markers highlights the importance of crossing genetically distinct parents to broaden the genetic base and accelerate the development of high-yielding, well-adapted cultivars. The findings of this study enhance the understanding of the genetic determinants of key agronomic traits in barley and provide a practical framework for breeding programs that integrate heterosis exploitation with targeted selection.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zohary, D., Hopf, M. & Weiss, E. Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The origin and spread of domesticated plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Taşci, R. & Bayramoğlu, Z. Evaluation of barley production processing and marketing structure. (2020).

TUIK. Crop Production Statistics; Turkish Statistical Institute: Ankara, Turkey. (2024).

Madakemohekar, A., Prasad, L., Lal, J., Bornare, S. & Prasad, R. Study of heterosis and combining ability in exotic and indigenous crosses of barley (Hordeum vulgar L.) under rainfed environment. Bioscan 10, 751–756 (2015).

Shrestha, S. L., Luitel, B. P. & Kang, W. H. Heterosis and heterobeltiosis studies in sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 52, 278–283 (2011).

Potla, K., Bornare, S., Prasad, L., Prasad, R. & Madakemohekar, A. Study of heterosis and combining ability for yield and yield contributing traits in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Bioscan 8, 1231–1235 (2013).

Farshadfar, E., Ghanadha, Sutka, J. & Zahravi, M. Generation mean analysis of drought tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Acta Agron. Hung. 49, 59–66 (2001).

Mather, K. & Jinks, J. L. Introduction to biometrical genetics (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Ahmed, Z. & Mekbib, B. Assessing parent combining ability and gene interactions via diallel analysis for scald resistance in barley. Am. J. Hortic. Floric. Res. 6, 01–09 (2024).

Chukwu, S. et al. Application of diallel analyses in crop improvement. Agric. Biol. J. N. Am. 7, 95–106 (2016).

Singh, S., Prasad, L., Madhukar, K., Chandra, K. & Prasad, R. Heterosis and combining ability of indigenous and exotic crosses of barley. Plant Arch. 17, 813–820 (2017).

Jinks, J. Analysis of diallel crosses. Maize Genet. Coop. Newslett. 27, 48–54 (1953).

Griffing, B. Concept of general and specific combining ability in relation to diallel crossing systems. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 9, 463–493 (1956).

Riyanto, A., Hidayat, P., Suprayogi, Y. & Haryanto, T. A. D. Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method. Open Agric. 8, 20220169 (2023).

Fehr, W. (Macmillan, New York, USA, 1987).

Masood, M. S. & Kronstad, W. Combining ability analysis over various generations in a diallel cross of bread wheat. (2000).

Pesaraklu, S., Soltanloo, H., Ramezanpour, S., KalateArabi, M. & NasrollahNejadGhomi, A. An estimation of the combining ability of barley genotypes and heterosis for some quantitative traits. Iran Agric. Res. 35, 73–80 (2016).

Sannemann, W., Huang, B. E., Mathew, B. & Léon, J. Multi-parent advanced generation inter-cross in barley: High-resolution quantitative trait locus mapping for flowering time as a proof of concept. Mol. Breeding 35, 1–16 (2015).

Ben Romdhane, M., Riahi, L., Jardak, R., Ghorbel, A. & Zoghlami, N. Fingerprinting and genetic purity assessment of F1 barley hybrids and their salt-tolerant parental lines using nSSR molecular markers. 3 Biotech 8, 57 (2018).

Gao, H. et al. Analysis of parental genetic diversity and its impact on grain yield and quality of japonica hybrid rice in northern China. Crop J. 10, 904–910 (2022).

Kalendar, R., Antonius, K., Smýkal, P. & Schulman, A. H. iPBS: a universal method for DNA fingerprinting and retrotransposon isolation. Theor. Appl. Genet. 121, 1419–1430 (2010).

Yildiz, M. et al. Genetic diversity analysis in the Turkish pepper germplasm using iPBS retrotransposonbasedmarkers. Turk. J. Agric. For. 44, 1–14 (2020).

Bouchetat, F. & Aissat, A. Evaluation of the genetic determinism of an F1 generation of barley resulting from a complete diallel cross between autochthones and introduced cultivars. Heliyon 5 (2019).

Rohman, M. M., Begum, S. & Mohi-Ud-Din, M. A 7× 7 diallel cross for developing high-yielding and saline-tolerant barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Heliyon 10 (2024).

Singh, V., Krishna, R., Singh, S. & Vikram, P. Combining ability and heterosis analysis for yield traits in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum). Indian J. Agric. Sci. 82, 916 (2012).

Doyle, J. J. & Doyle, J. L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochemical bulletin (1987).

Haliloğlu, K. et al. Genetic diversity and population structure in bread wheat germplasm from Türkiye using iPBS-retrotransposons-based markers. Agronomy 13, 255 (2023).

Chiang, M. S. & Smith, J. Diallel analysis of the inheritance of quantitative characters in grain sorghum. I. Heterosis and Inbreeding depression. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 9, 44–51 (1967).

Fonseca, S. & Patterson, F. L. Hybrid vigor in a seven-parent diallel cross in common winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) 1. Crop Sci. 8, 85–88 (1968).

Ozcan, K. Development of a Statistical Package for Population Genetics. Ege University Institute of Science and Technology. PhD Thesis, IZMIR. (1999).

Rohlf, F. J. NTSYS-pc: numerical taxonomy and multivariate analysis system. (Applied Biostatistics, 1992).

Anderson, J. A., Churchill, G., Autrique, J., Tanksley, S. & Sorrells, M. Optimizing parental selection for genetic linkage maps. Genome 36, 181–186 (1993).

Eshghi, R. & Akhundova, E. Genetic analysis of grain yield and some agronomic traits in hulless barley. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 4, 1464–1474 (2009).

Madić, M., Djurović, D., Knezevic, D., Paunović, A. & Tanasković, S. Combining abilities for spike traits in a diallel cross of barley. Journal of Central European Agriculture 15, 0–0 (2014).

Metwali, E. M., Abd-El-Haleem, S. H. & EL-Saeid, R. & Kadasa, N. M.,. An investigation of gene action on different traits of barley (Hordeum Vulgare L.) using partial diallel crosses system. Life Sci. J. 11, 64–71 (2014).

Popova, T. & Valcheva, D. Analysis of two-row barley accessions by commercial traits for selection purposes. (2021).

Tofiq, S., Amin, T., Abdulla, S. & Abdulkhaleq, D. Genetic analysis in some barley varieties and their hybrids in F2 generation. Int. J. Plant, Anim. Environ. Sci. 5, 208–217 (2015).

Zhang, X., Lv, L., Lv, C., Guo, B. & Xu, R. Combining ability of different agronomic traits and yield components in hybrid barley. PLoS ONE 10, e0126828 (2015).

Amer, K. A., Eid, A., Elakhdar, A. & El-Shawy, E. Combining ability and heterosis in five barley genotypes for some economic traits. Egypt. J. Agric. Res. 90, 105–116 (2012).

Patial, M., Pal, D. & Kumar, J. Combining ability and gene action studies for grain yield and its component traits in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). SABRAO J. Breed. Genet. 48 (2016).

Moustafa, E., Nassar, S., Farag, H. & Megahed, K. Performance and grain yield stability of some barley genotypes under varying environments. Egypt. J. Plant Breed. 23, 1683–1712 (2019).

Ahmed, D. A., Tahir, N.A.-R., Salih, S. H. & Talebi, R. Genome diversity and population structure analysis of Iranian landrace and improved barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) genotypes using arbitrary functional gene-based molecular markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 68, 1045–1060 (2021).

Güngör, H. et al. Genetic diversity and population structure of Barley cultivars released in Turkey and Bulgaria using iPBS-retrotransposon and SCoT markers. J. Agric. Sci. 14–14 (2022).

Yeken, M. Z. et al. Genetic diversity and population structure in Turkish barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) cultivars using start codon targeted (SCoT) markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 1–12 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for their constructive comments on this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.G, A.T. and J.B.; methodology, H.G., M.F.C., K.H., Z.D., İ.Y., A.T. and J.B.; software, H.G., A.T., M.F.C., K.H., Z.D. and J.B.; validation, H.G., A.T., Z.D. and J.B.; formal analysis, H.G., A.T., M.F.C., K.H., Z.D. and J.B.; investigation, H.G., A.T. and J.B; resources, H.G.; data curation, H.G., A.T., M.F.C., K.H., Z.D. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, H.G., A.T., M.F.C., K.H., Z.D., H.A. and J.B.; writing—review and editing, H.G., A.T., H.A. and J.B.; visualization, H.G. and A.T.; supervision, H.G.; project administration, H.G.; funding acquisition, H.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Güngör, H., Türkoğlu, A., Çakır, M.F. et al. Enhancing and comparison of yield components through diallel analysis in F1, F2, F3 and F4 barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) populations. Sci Rep 15, 45796 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28712-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28712-0