Abstract

Considerable amounts of heavy metals can be released through mining activities, and different heavy metals, such as Cd, Cu and Mo exhibit varying release behaviors from tailings and ores under similar conditions; therefore, the insight to their release risk for tailings, waste rock, and ores is crucial for developing protection strategies for mines. In this study, samples of tailings, ores, and surface water were collected from a high-latitude polymetallic mine in China to investigate the risk of heavy metal release. Relatively high concentrations of heavy metals such as Cd, Cu and Mo were found in tailings and some ores. However, tailings were classified as nonacid generation indicating a low release risk of heavy metals, and only some ore samples (DBS2, DBS3 and DBS5) with high concentrations of Cd, Cu and Mo were classified as acid generation. At low leaching pH, more Cd, Cu, and Fe were leached from tailings and DBS5 because of the dissolution of chalcopyrite. In contrast, elevated Mo concentrations in the leachate were observed under neutral and alkaline conditions (pH = 7 and 9), which can be attributed to the high adsorption capacity of MoO42− on tailings and ores, as well as the easy dissolution of molybdenite under neutral to alkaline conditions. The results suggest that under acidic conditions and in environments with potential for acid generation, increased attention should be directed toward the release risks of cationic heavy metals such as Cd and Cu. In contrast, under neutral or alkaline conditions, the mobilization risks of anionic heavy metals such as Mo require more rigorous monitoring. The surface water samples near the mine contained relatively high concentrations of Cd, Cu, and SO42− with low pH, indicating that the surface water was affected by mining activities. These findings suggest that acid mine drainage (AMD) generated from waste rocks or ores, rather than tailings, is the primary cause of elevated heavy metal concentrations in surface water.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heavy metal pollution has been widely studied worldwide because of its high toxicity, bioaccumulation and nondegradability1,2,3,4. The exploitation of mineral resources provides indispensable material foundations; however, mining activities result in the release of substantial amounts of heavy metals into surface water, soil and groundwater, ultimately leading to severe heavy metal pollution5,6. The cadmium concentration in the soil or sediment near nonferrous metal mines can reach several to dozens of mg/kg, whereas the concentrations of Pb and Cu can range from several hundred to several thousand mg/kg7,8. Furthermore, heavy metals released from tailings and waste rocks can be transported over long distances as ions or particles because of hydrodynamic forces. Even tens of kilometers downstream from areas with intensive mining activities, the concentrations of heavy metals in surface water and sediments remain significantly elevated compared with background levels9,10,11. Ultimately, extremely high concentrations of heavy metals in terrestrial ecosystems and aquatic ecosystems severely threaten human health through the food chain.

Mining activities generate substantial tailings, waste rocks and ores, from which heavy metals are leached under long-term weathering. Especially for sulfide deposits, long-term exposure of sulfide minerals, such as pyrite (FeS2), chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), gelenite (PbS), sphalerite (ZnS), and molybdenite (MoS2), in tailings, waste rocks and ores to air, weathering and rainwater leaching may generate acid mine drainage (AMD) with low pH values and high concentrations of heavy metals and sulfate12. AMD can reduce the pH of surface water and soil around mining areas and further promote the accumulation of heavy metals in soils, tailings and ores, eventually leading to the dissolution and release of heavy metals13. The generation of AMD is not only dependent on the content of sulfide minerals but also on the components of alkaline minerals, such as dolomite (MgCO3) and calcite (CaCO3), which can naturalize AMD and reduce the environmental risk of heavy meal release14,15. Moreover, the leaching pH, dissolved oxygen content, mineral properties, ferric iron content, etc., control the release behaviors of heavy metals from tailings, waste rocks and ores16,17. Sulfide minerals tend to dissolve more readily under lower pH conditions, leading to the release of increased amounts of heavy metals from these minerals5,18,19,20. Moreover, the oxidation of Fe3+ promotes the accelerated release of Cu, Pb and Zn from waste rock, tailings and ores21. However, some heavy metals, such as molybdenum (Mo) and tungsten (W), which exist as anions in the environment, may present different release behaviors from those of cationic heavy metals, such as Cu, Pb and Zn2. With respect to polymetallic sulfide deposits, in which ores or tailings contain many kinds of heavy metals, such as Pb, Zn, Cu, Mo and W, the release patterns of these heavy metals are more complicated.

The Duobaoshan ore concentration area is the largest polymetallic ore concentration area in Northeast Asia and features high latitude and rich mineral resources, including porphyry copper (molybdenum) deposits, skarn iron‒copper deposits and hydrothermal gold deposits. The reserves of the Duobaoshan porphyry Cu-Au-Mo-Ag deposit rank first among copper deposits in China and 33rd among porphyry copper deposits worldwide22,23. Extensive mining activities may lead to the release of many heavy metals into surface water around the Duobaoshan ore concentration area. Therefore, the objectives of this systematic survey of the Duobaoshan ore concentration area are as follows: (i) evaluate the acid-producing potential of tailings and ores; (ii) investigate the release mechanisms of heavy metals, especiall for Mo from polymetallic sulfide tailings and ores; and (iii) assess the impact of mining activities on the heavy metal concentrations in surface water.

Materials and methods

Study area and sampling

The Duobaoshan ore concentration area is located at the southwest slope of the northwestern section of the Lesser Khingan Mountains in Heilongjiang Province, China. In terms of its geotectonic position, this region lies in the superposed area of the Xingmeng orogenic belt and the circum-Western Pacific active continental margin tectonic belt (Fig. S1)23. Characterized by a high-latitude setting, this region is exceptionally rich in mineral resources, hosting porphyry copper (molybdenum) deposits, skarn-type iron-copper deposits, and hydrothermal gold deposits. It represents the largest polymetallic ore concentration zone in Northeast Asia . The strata exposed in known deposits and occurrences within the district are predominantly of Ordovician and Silurian age. The primary ore-hosting unit is the Middle Ordovician Duobaoshan Formation (O2d), which consists of a volcanic rock sequence dominated by andesite and intermediate to felsic tuff. The average copper content in the Duobaoshan Formation is 130 × 10–6, markedly higher than that observed in other strata within the ore district, indicating its critical role as the principal source of metallogenic materials22. It is the largest polymetallic ore concentration area in Northeast Asia and contains several large‒small porphyry copper‒molybdenum deposits, epithermal gold deposits and skarn iron‒copper deposits22. The Duobaoshan copper deposit is a typical sulfide deposit, and the main minerals include chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), bornite (Cu5FeS4), pyrite (FeS2), molybdenite (MoS2) and sphalerite (ZnS).

The study are features a cold temperate continental monsoon climate. The climatic conditions are characterized by a low annual average temperature and a prolonged winter season. The multi-year average temperature ranges from 0.8 to − 1.4 °C. The average annual precipitation varies between 480 and 512 mm. The prevailing wind direction is northerly, followed by southerly winds. Winters are long, severely cold, and dry, with minimum temperatures reaching − 47.3 to − 43.7 °C. Summers are marked by concurrent rainfall and high temperatures, with maximum temperatures ranging from 33.9 to 37.4 °C. Spring is characterized by strong winds and significant diurnal temperature variations, accompanied by abundant sunshine. The Duobaoshan stream, with a length of approximately 25 km, is located north of the copper mine and flows through the Heibaoshan coal mine before finally reaching the Niqiu River (Fig. 1).

The tailings pond, a valley-type facility, is situated 5 km south of the mining area, with a total storage capacity of 92 million m3. In 2018, approximately 50 million m3 of tailings were discharged into the pond. Fresh surface tailings were collected from multiple locations within the active pond and combined into a single composite sample (WK) to improve representativeness. A total of 7 ore samples (DBS1–DBS7) from the stope were collected from the Duobaoshan copper mine. The tailing sample (D50 = 0.058 mm) was air-dried and sealed in polyethylene bottles, and the waste rock and ore samples were crushed, ball-milled, screened with a 200-mesh sieve and then placed in a polyethylene bottle.

One mining drainage sample (W1) and 4 surface water samples (W2–W5) along the Duobaoshan stream were collected during the wet and ordinary seasons, respectively, in July 2018 and September 2018. A 5-L volume of surface water was sampled and filtered via preweighted glass fiber filters (0.45 μm) to separate suspended particulate matter (SPM) after natural sedimentation for 30 min. The surface water was acidified with 0.1 mol/L HNO3 to pH < 2 and stored in polyethylene containers at 4 °C to analyze dissolved heavy metals. The glass fiber filters containing SPM were freeze-dried.

Physical and chemical analysis

Tailings and ores

The paste pH and paste electrical conductivity (EC) (m:v = 1:2.5) of the tailings and ore powder samples were determined with a pH meter (ST3100, Ohaus, USA) and a conductivity meter (FE38-Standard, Mettler Toledo, Germany), respectively. The total sulfur content (TS) was determined via an elemental analyzer (EA1112, Thermo Flash, USA). The mineral compositions of samples were identified via X-ray diffraction (XRD; EMPYREAN, PANalytical, Netherlands) at 40 mA and 40 kV via Cu Kα radiation at 25 °C; the instrument was operated as a scanning range of 7–70°. a step width of 0.013°, a time constant of 4°/min, a slit DS (divergent slit) = 0.4354°, and an aperture RS (receiving slit) of 0.1 mm. Quantitative analyses of the minerals were performed using the Rietveld method, and the results were normalized to 100% based on the assumption that the mineral contents of the samples were entirely accounted for by the XRD patterns. The analysis was conducted using Xray Run (version 2019), developed by the China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), for qualitative and semi-quantitative analysis.

The total concentrations of Mn, Zn, Cu, As, Cr, Mo, Cd, Pb, Ni, Fe and S in the tailings and ores were measured via inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP‒AES; ICAP-9000, Jarrel-ASH, USA) after the sample was digested with a HNO3:HClO4:HF (V:V:V = 3:3:1) mixture. To ensure analytical quality, geochemical standard soil samples (GSS-1 and GSS-2) provided by the National Research Center for Geoanalysis of China were used to validate the analytical method. The recoveries of the standard samples ranged from 93 to 113%.

The tailing samples were extracted via the improved European Community Bureau of Reference (BCR) sequential extraction procedure24 to obtain the weak acid extractable fraction (F1), reducible fraction (F2) and oxidizable fraction (F3) of Cd, Cr, Pb, Zn, Mn, Ni and Cu. A sequential extraction of As from the tailing samples was also performed following the Wenzel procedure25. This procedure separates As into four fractions, i.e., the nonspecific adsorption fraction (F1), specific adsorption fraction (F2), amorphous Fe‒Al oxide-bound fraction (F3) and crystalline Fe‒Al oxide-bound fraction (F4). The concentrations of heavy metals in the extract were determined via ICP‒OES. To obtain the mass balance of heavy metals in the tailings, the residual fraction (F5 for As, F4 for other heavy metals) was measured after acid digestion via the procedure described above for total metal determination. The recoveries which were defined as the sum of various fractions divided by the total content, ranged from 96 to 116%.

Surface water

For surface water, the pH, EC and dissolved oxygen (DO) content were measured in situ via a multisensor sonder (YSI 6600, USA) during sampling. Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in surface water was analyzed by a total organic carbon (TOC) analyzer (TOC-VCPH/CPN, Shimadzu, Japan) after filtration through 0.45 μm fiber filters. The SO42− concentration was measured via ion chromatography (ICS-1600, Diane, USA). The concentrations of dissolved As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Mn, Mo, Ni, Pb and Zn in the surface water were determined via an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS, X Series 2, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Weighted glass fiber filters containing SPM were dried to constant weight at 60 °C, weighed, and subsequently digested with HNO3:HClO4:HF (V:V:V = 3:1:1). The concentrations of As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Mn, Mo, Ni, Pb and Zn in SPM were determined via ICP‒OES after digestion. The blank concentrations of heavy metals in the clean glass fiber filters were also measured after acid digestion as described previously.

Acid–base accounting and NAG

The Sobek acid‒base counting test (ABA) was used to determine the acid potential (AP) and neutralization potential (NP) of tailings and ores26. The NP content was determined via acid‒base titration. The AP was calculated on the basis of the total sulfur content in the sample, considering all sulfide occurrences as pyrite, and on the basis of the stoichiometry of pyrite/calcite oxidation/neutralization:

where Total% S is the total sulfur content of the ore and 31.25 is the correction factor.

The net neutralization potential (NNP, NP-AP) and acid potential ratio (APR, NP/AP) were used to assess acid generation. Acid generation is uncertain for NNP values between − 20 and 20 kg CaCO3/t, likely for NNP values below − 20 kg CaCO3/t, and unlikely for NNP values above 20 kg CaCO3/t27. Three classes of APRs have been suggested: acid generation, APR < 1; uncertainty of acid generation, 1 < APR < 3; and nonacid generation, APR > 328.

Net acid production (NAG) and NAG-pH were also obtained to assess acid generation29,30. A 100-mL volume of 15% H2O2 was added to 1 g of each sample, and the resulting mixture was left to stand overnight. After heating until the end of bubbling, deionized water was added to 100 mL after cooling, and the pH was measured as NAG-pH. NAG (kg CaCO3/t) was obtained by titrating the solution with 0.1 mol/L NaOH to pH = 7.0. Three classes were suggested: potential acid production, NNP < 0 and NAG-pH < 4.5; uncertainty of acid production, NNP < 0 and NAG-pH > 4.5 or NNP > 0, and NAG-pH < 4.5; and nonacid production, NNP > 0, and NAG-pH > 4.5.

Leaching experiments

According to the heavy metal concentrations in the tailings and ores, samples of tailings and DBS5 ore were selected for leaching experiments. The samples of tailings or DBS5 (10 g) ore were weighed into a conical flask, and 300 mL of deionized water was added. The solution pH was adjusted to 4, 7 or 9 with 0.1 mol/L NaOH or 0.1 mol/L HNO3. The mixture was sealed with parafilm with small holes and then shaken at 25 °C. The pH values of this mixture were adjusted daily to the initial pH values by 0.1 mol/L NaOH and HNO3. The redox potential (ORP) and EC of the solutions were measured every 8 h. At incubation Days 4, 6, 8, 10, 14, 18, 22 and 26, approximately 5 mL of the mixture was collected and then centrifuged for 10 min at 4000 rpm. The Cd, Cu, Fe, Mo and S concentrations in the supernatant were determined via ICP‒OES.

Water quality assessment

The single factor pollution index method and Nemerow pollution index method were selected to assess the quality of surface water31,32. The single factor index (Pi) was calculated for each sample according to the following equation:

where Ci is the metal concentration (mg/L) and Si is the standard value of environmental quality (mg/L), which is the category III water standard in the Environmental Quality Standard for Surface Water (GB 3838—2002) of China. Water quality levels are classified into five categories (Table S1). The category of the worst single index among all the indicators involved in the evaluation is used to determine the comprehensive water quality category of the water31. The Nemerow comprehensive method (PN) is used to comprehensively evaluate water quality, considering the average and maximum values of a single factor index. The calculation formula is as follows31:

where \(\overline{P }\) is the average value obtained from the single factor index and PiMax is the maximum value among all single factor indices. PN can be classified into five grades, and the classification criteria is presented in Table S2.

Results and discussion

Physicochemical properties of tailings and ores

The values of paste pH and paste EC are shown in Table 1. The paste pH and paste EC reflect the current acidity status and the soluble salt concentrations in the samples, respectively. The paste pH of WK was alkaline at 8.33, and the paste pH values of the ore samples ranged from 6.65 to 7.84. The paste EC value of the tailings was 650 μs/cm, which is related to the dissolution of more ions caused by mineral processing activities. The paste EC values of the ore samples ranged from 253 to 1066 μs/cm. The high paste EC values of the ore samples may be attributed to the presence of a small amount of soluble minerals.

The XRD results for the tailings and ores are shown in Fig. S2 and Table S3. The main mineral components of the tailings and ore samples were gangue minerals such as quartz, muscovite, chamosite and albite, accounting for approximate 95%. Silicate minerals such as muscovite, albite and chamosite and calcite may account for the high pH values of the samples28,33. Notably, the DBS2, DBS3 and DBS5 ore samples contained chalcopyrite, ranging from 0.61 to 5.41%, and no obvious sulfide minerals were found in the other samples. High contents of chalcopyrite for the DBS2, DBS3 and DBS5 ore samples indicated high acid generation potentials. Moreover, other sulfide minerals, such as molybdenite (MoS2) and pyrite (FeS2) were also did not be found due to low contents. The concentrations of sulfide minerals were low for tailings indicated that oxidation occurred during mineral processing34,35.

Element occurrence in tailings and ores

The heavy metal concentrations in the WK samples decreased in the following order: Cu (491.60 mg/kg) > Mn (483.00 mg/kg) > Zn (189.10 mg/kg) > Cr (65.65 mg/kg) > Ni (19.35 mg/kg) > Mo (14.58 mg/kg) > Pb (9.07 mg/kg) > Cd (2.89 mg/kg) > As (2.84 mg/kg) (Table 1). The concentrations of Cd and Cu exceeded the risk screening values for paddy soil (GB 15618–2018), indicating high potential risk. The mean concentrations of heavy metals in the ore samples followed the order of Cu (9164.50 mg/kg) > Mn (428.16 mg/kg) > Zn (49.82 mg/kg) > Mo (35.54 mg/kg) > Cr (11.75 mg/kg) > Ni (8.06 mg/kg) > As (7.31 mg/kg) > Pb (7.29 mg/kg) > Cd (0.53 mg/kg). The Fe concentrations in the ore samples ranged from 13.17 to 88.59 g/kg and were comparable to those in the tailings (35.98 g/kg). The S concentrations in the ore samples were closely related to the generation of AMD and ranged from 0.83 to 43.87 g/kg. A high S concentration was detected in DBS2, which was consistent with the XRD results. In addition, the concentrations of associated elements such as Zn, Mo, Cd and Mn were also high in DBS2, indicating the potential generation of AMD. High concentrations of S, Zn, Mo and Mn were also observed for DBS5. The S concentration of the tailings was relatively low, at 0.54 g/kg.

The mobility and toxicity of heavy metals in tailings or soils depend not only on the total concentrations of heavy metals but also on their speciation36. Zn, Pb, Cr and Cd in the tailings constituted more than 70% of the residual fraction (Fig. S3), indicating that these heavy metals were not easily released from the tailings and posed a low environmental risk2,37. The weak acid extractable fractions of Mn and Ni accounted for 51.2% and 34.0%, respectively, indicating that the risk of Mn and Ni release from tailings was relatively high38. The Cu concentration was high, with a value of 491.60 mg/kg in the tailings, and the proportions of the weak acid extractable, reducible and oxidizable fractions were 4.2%, 11.8% and 66.3%, respectively. The results revealed that most of the Cu present in the tailings was in the oxidizable fraction. When redox conditions change, the Cu in the fraction may be released, resulting in a high environmental risk. The proportions of the nonspecific and specific adsorption fractions of As were relatively low, accounting for 1.1% and 13.0%, respectively. Moreover, the As concentration was low. The results indicated a low environmental risk of As for tailings.

Acid generation potential

The acid potential results of the tailings and ores are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2. The values of AP and NP ranged from 1.69 to 137.08 and 16.47 ~ 66.60 kg CaCO3/t, respectively. Notably, DBS2, DBS3 and DBS5 had high AP values and lower NP values, resulting in low NNP, which was consistent with the high contents of chalcopyrite, ranging from 0.61 to5.41%. The NNP results indicated that WK, DBS1, DBS6 and DBS7 could be classified as nonacid generation (NNP ≥ 20) and that DBS3 and DBS4 belonged to uncertain of acid generation (− 20 < NNP < 20). The acid generation of two ore samples, i.e., DBS2 and DBS5, was certain (NNP ≤ 20). The results of the ARP indicated that DBS2, DBS3 and DBS5 were certain acid generation (ARP > 3), and the other samples could be classified as nonacid generation (ARP < 1) (Fig. 2), which was almost consistent with the results of the NNP.

NAG is another indicator used to assess the acid generation potential and is a direct measure of the ability of a sample to produce acid through sulfide oxidation28,39. During NAG activity, SO42− does not participate in the reaction, and sulfides can be neutralized by OH- from other alkaline minerals in samples14,15. Therefore, NAG can actually reflect the capacity for acid production better than NNP can29. The NAG values of the tailings and ores ranged from 7.35 to 94.71 kg CaCO3/t. Notably, the NGA values of DBS2, DBS3 and DBS5 were relatively high, with values of 94.71, 33.08 and 34.16 kg CaCO3/t, respectively, indicating strong acid generation potential. The high acid generation potential of DBS2, DBS3 and DBS5 was also suggested by their NAG-pH results (Fig. 2). Generally, the results of various assessment methods for acid generation potential all indicated that DBS2, DBS3 and DBS5 could be classified as acid generation and that the others could be classified as nonacid generation or uncertainty of acid generation.

Release behaviors of key elements in tailings and ores

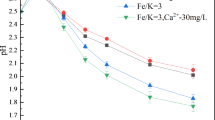

WK and DBS5, which have high heavy metal concentrations, were selected to study the release risk of key elements (S, Fe, Cd, Cu, and Mo). The changes in the ORP and EC of the leachate with leaching time are shown in Fig. 3. The ORP values of the WK and DBS5 samples decreased with increasing pH of the leaching solution. The ORP in the leaching solution gradually stabilized at approximately 320 mV after the eighth day at pH 4, and a drastic decrease with increasing leaching time was observed at pH 7 and 9. According to the pe–pH diagram of sulfur (Fig. S4), it can be inferred that sulfur existed as SO42− in the leachate40. The EC values of WK and DBS5 gradually increased with increasing leaching time at different pH values of the leaching solution. Notably, the EC of the leachate of DBS5 at pH 9 was considerably greater than that of the other samples and reached 3400 μS/cm at the end of the leaching experiment, indicating the dissolution of minerals during leaching.

Fe and Cu had similar release patterns for WK and DBS5. For the leaching experiment at pH 4, the Fe and Cu concentrations were relatively high and gradually increased with increasing leaching time (Fig. 4). High concentrations of Fe and Cu at pH 9 were not observed. With respect to Cd, only Cd was detected in some leachate samples at pH 4, and the Cd concentrations in the leachate at high pH values (7 and 9) were lower than the detection limit (0.0001 mg/L, Table S4). The low pH of leachate can increase the release of heavy metals such as Fe, Cu, Mn, Ni, Zn and Pb5,18,19,20. Notably, the concentrations of Fe, Cu, and Cd in the leachate were apparently lower than those reported in other studies18,19,20. This difference may have resulted from the low proportion of the weak acid extractable fraction of Cd and Cu (Fig. S2) and the low ratio of tailings/leaching solution (S/L) in the present study.

Notably, more Mo was detected with increasing solution pH, which was inconsistent with the results for Fe, Cu and Cd. Mo exists mainly in the natural environment as molybdate (MoO42−) (Fig. S5), which is more easily adsorbed by minerals at lower pH values (3 ~ 4)41,42. A high solution pH resulted in more adsorption of MoO42− on tailings and ore samples during leaching experiments. In addition, Mo-containing minerals such as molybdenite (MoS2) are stable in acidic environments, but they undergo oxidative dissolution under atmospheric conditions and natural to alkaline conditions (Eq. 4)42:

The concentrations of S in the tailings were low and fluctuated slightly during the leaching experiments, and obvious differences in S concentrations were not observed during leaching at various pH values, indicating less oxidation of sulfide minerals (Fig. 4). Notably, the S concentration in the leachate increased gradually at pH 7 and 9 for DBS5, which was consistent with the results for EC and Mo and contrary to the results for Cd and Cu. More S, Fe, Cu and other relevant elements are released from tailings when the initial pH of the leaching solution is low because of the dissolution of pyrite and chalcopyrite2,37,43. This paradoxical result may be ascribed to the dissolution of other S-bearing minerals, such as MoS2, at natural to alkaline pH values42. The release patterns of S shown the codissolution of some minerals, such as pyrite, chalcopyrite and molybdenite, and the dissolution of some sulfate also contributed to increasing the S concentration in the leachate.

Heavy metals in surface water

Physicochemical properties of surface water

The physicochemical properties of the surface water are shown in Table 3. The pH of the surface water in the wet season and ordinary season ranged from 4.8 to 7.6 and from 6.8 to 7.6, respectively. W2 downstream of the mine was acidic in the wet season, which indicated that this point was strongly affected by mining activities. The more intensive influence in the wet season was further proven by the results of EC and SO42−. The EC (811.0–1347.0 μS/cm) and SO42− (40–110 mg/L) concentrations in the wet season were greater than the EC (102.6–856.0 μS/cm) and SO42− (10–100 mg/L) concentrations in the ordinary season. Moreover, significant linear negative correlations existed between pH and EC and between pH and SO42− (R2 = 0.961 and 0.704, respectively; Fig. S6). This result is obtained likely because more rainfall in the wet season leads to more acid drainage from the mine area entering the Duobaoshan stream with surface runoff. The DOC concentrations of surface water in the wet season (3.54–4.59 mg/L) were significantly lower than those in the ordinary season (7.61–11.57 mg/kg). This difference can be attributed to the higher temperature during the wet season, as elevated temperatures promote enhanced degradation of organic matter11. The concentrations of SPM in the wet season ranged from 2.1 to 66.2 mg/L, slightly exceeding those in the ordinary season (1.4–57.9 mg/L). During the wet season, intense rainfall can cause soil erosion and increase SPM levels in rivers44. The DO of surface water changed slightly in the wet season and ordinary season.

Heavy metal distribution and pollution assessment

The results of the element occurrence, acid-producing potential and heavy metal release risk of tailings and ores revealed that some heavy metals may be released into surface water because of the mining activities of the Duobaoshan copper mine. The concentrations of heavy metals in the surface water are shown in Fig. 5. In July, the total concentrations of Cd and Cu in W2 were 0.0079 and 2.711 mg/L, respectively, which exceeded their Class III limits. The results revealed that the concentrations of heavy metals in surface water 5 km downstream from the tailings pond can be considerably affected by mining activities during the wet season. The Zn concentration in W1 was also higher than the limit value of Class III, with a value of 1.135 mg/L. The Cr, Ni, Mo and Mn concentrations, which are not specified in the Chinese Standard (GB3838-2002), ranged from 0.0231–0.0277, 0.0036–0.0589, 0.0052–0.0111 and 0.5533–9.6361 mg/L, respectively, in July. Notably, almost all the heavy metals had lower concentrations in September than in July, indicating the good quality of the surface water. This result was due to the large amount of rainfall in the wet season, which caused more heavy metals to be discharged into the Duobaoshan stream because of the erosion of mining areas, waste rocks, tailings, slag and so on. With the exceptions of Zn, Cd and Cu, the pollutants in W1 and W2 were mainly dissolved during the wet season, and the surface waters in W1 and W2 were acidic, with pH values of 6.3 and 4.8, respectively. The total Zn concentration was not very high, and most of the Zn (83%) existed as a residual form in the tailings, which is considered stable. Thus, it is unsurprising that more Zn was particulate in the surface water.

The Pi results are presented in Table S5 and Fig. S7. In July, the water quality levels of Cd in W2, Cu in W2 and Zn in W1 were Class II, Class III and Class II, respectively. The other sites had good water quality (Class I). The concentrations of Cd and Cu in W1 and W2 were obviously lower in September than in July. The water quality of all the sites for heavy metals reached Class I. The Nemerow comprehensive indices of W1 and W2 were 0.876 and 2.038, respectively, in July, indicating Class III and Class IV. The pollution level at the other sites was Class I. Moreover, in September, the water quality reached Class I, indicating no pollution.

During the wet season, the negative correlations between most elements and pH reached a significant level (pH vs. Cd, Cu, Ni, Mn and SO42−, p < 0.05) (Fig. S8). The leaching experiments proved that a low pH caused more release of Cu and Cd ions from tailings and ores. Tailings are classified as nonacid generating, and only a limited number of heavy metals are released under various leaching pH conditions. The positive correlation between pH and heavy metals further revealed that waste rocks and ores, instead of tailings, can generate AMD and lead to the release of heavy metals into the environment as ions in the wet season. Even so, tailings can migrate into surface water as fine particles via water hydrodynamic forces and increase heavy metal concentrations in SPM11,45. During the ordinary season, the correlations between pH and As, as well as pH and Mo, were significantly positive (p < 0.05). Similarly, during the wet season, the correlations between pH and these two elements remained positive. These findings are consistent with the leaching results, indicating that higher pH levels can promote the release of these elements in anionic forms.

Environmental impications

The release of heavy metals from polymetallic mines is complex due to the heterogeneous composition of ores, waste rocks, and tailings. However, most studies have not thoroughly explored the underlying causes of heavy metal pollution in areas near the mine46,47,48. In this study, although tailings exhibited high concentrations of heavy metals, significant environmental risk was not observed owing to the absence of acid generation and relatively low sulfide content. A strong correlation among Cd, Cu, pH, and SO42− in surface water suggests that acid generation from ores may be the primary driver of metal release. Therefore, understanding the underlying mechanisms of heavy metal release is crucial for mitigating environmental risks associated with mining activities. Moreover, certain heavy metals such as Mo, As, and W, which exist predominantly as oxyanions in aqueous environments, may exhibit distinct release patterns compared to cationic metals like Cu, Pb, and Zn. Particular attention should be paid to the release of Mo, W, and As from ores, waste rocks, and tailings under high-pH conditions. A limitation of the presented study is the absence of direct evidence for the dissolution of Mo-bearing minerals due to low contents of Mo-bearing minerals, as well as the lack of thermodynamic modeling. In-situ analytical techniques, such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and the Advanced Mineral Identification and Characterization System (AMICS), could provide critical insights into the behaviors of these minerals in natural systems. Their potential dissolution under varying environmental conditions, such as low temperature and freeze–thaw cycling should be further investigated as well.

Conclusion

Tailings from the Duobaoshan polymetallic ore concentration area contained relatively high concentrations of Cd (2.89 mg/kg) and Cu (491.6 mg/kg) but were classified as nonacid generating. In contrast, ores DBS2, DBS3, and DBS5, which had relatively high concentrations of Cu, Cd, and Mo, respectively, were classified as acid-generating. Leaching experiments on tailings and DBS5 indicated that Cd, Cu, and Fe concentrations in the leachate were higher at pH 4. Conversely, the Mo concentrations were greater at pH values of 7 and 9. This phenomenon can be attributed to the high adsorption capacity of MoO42− on tailings and ores, as well as the easy dissolution of molybdenite (MoS2) under neutral to alkaline conditions. A similar tendency of Mo and S in the leachate further suggests the codissolution of minerals such as pyrite, chalcopyrite, and molybdenite. Additionally, surface water analyses revealed negative correlations between pH and Cd, Cu, Ni, Mn, and SO42−, while positive correlations were observed between pH and Mo and As. These findings are consistent with the results of the leaching experiments. Near the mining area, surface water presented high concentrations of Cd, Cu, and SO42− along with relatively low pH values. It can be concluded that waste rocks and ores, rather than tailings, are more likely to generate acid mine drainage (AMD) and contribute to the release of heavy metals into the environment.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Dong, Q.-Y. et al. Health risk assessment of heavy metals in soils and crops in a mining area (Au-Ag-Cu-trona-oil et al.) of the Nanyang Basin, Henan Province, China. China Geol. 6, 567–579. https://doi.org/10.31035/cg2022078 (2023).

Zheng, X., Qiu, S., Zhou, B., Li, Q. & Chen, M. Leaching of heavy metals from tungsten mining tailings: A case study based on static and kinetic leaching tests. Environ. Pollut. 342, 123055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.123055 (2024).

Ippolito, J. A. et al. Soil health as a proxy for long-term reclamation success of metal-contaminated mine tailings using lime and biosolids. Soil & Environ. Health https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seh.2024.100096 (2024).

Khosravi, R., Nemati Mansour, S., Ekrami, J. & Mosaferi, M. Health and ecological risks assessment of heavy metals and metalloids in surface sediments of Urmia Salt Lake, Northwest of Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess 195, 403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-023-10946-y (2023).

Li, W., Deng, Y., Wang, H., Hu, Y. & Cheng, H. Potential risk, leaching behavior and mechanism of heavy metals from mine tailings under acid rain. Chemosphere 350, 140995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140995 (2024).

Chilikwazi, B., Onyari, J. M. & Wanjohi, J. M. Determination of heavy metals concentrations in coal and coal gangue obtained from a mine in Zambia. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Te 20, 2053–2062. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-022-04107-w (2023).

Li, Z., Ma, Z., van der Kuijp, T. J., Yuan, Z. & Huang, L. A review of soil heavy metal pollution from mines in China: Pollution and health risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 468–469, 843–853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.08.090 (2014).

Tao, L. et al. Trace metal pollution in a Le’an River tributary affected by non-ferrous metal mining activities in Jiangxi Province, China. Chem. Ecol. 30, 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/02757540.2013.861824 (2014).

Bai, H. et al. Heavy metal pollution in sediments of the Yu River in a polymetallic ore concentration area: Temporal-spatial variation, risk assessment, and sources apportionment. Sustainability 16, 1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031154 (2024).

Elvine Paternie, E. D. et al. Geochemistry and geostatistics for the assessment of trace elements contamination in soil and stream sediments in abandoned artisanal small-scale gold mining (Bétaré-Oya, Cameroon). Appl. Geochem. 150, 105592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2023.105592 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Temporal-spatial variation and partitioning of dissolved and particulate heavy metal(loid)s in a river affected by mining activities in Southern China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 25, 9828–9839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-1322-x (2018).

Guerrero, J. L., Suárez-Vaz, N., Paz-Gómez, D. C., Pérez-Moreno, S. M. & Bolívar, J. P. Spatiotemporal evolution of U and Th isotopes in a mine effluent highly polluted by Acid Mine Drainage (AMD). J. Hazard Mater. 447, 130782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.130782 (2023).

Zheng, Y. et al. Temporal and spatial evolution of different heavy metal fractions and correlation with environmental factors after prolonged acid mine drainage irrigation: A column experiment. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173136 (2024).

Chotpantarat, S. A review of static tests and recent studies. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 8, 400–406. https://doi.org/10.3844/ajassp.2011.400.406 (2011).

Sahoo, P. K., Tripathy, S., Panigrahi, M. K. & Equeenuddin, S. M. Geochemical characterization of coal and waste rocks from a high sulfur bearing coalfield, India: Implication for acid and metal generation. J. Geochem. Explor. 145, 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gexplo.2014.05.024 (2014).

Tian, S. et al. Leaching characteristics and environmental impact of heavy metals in tailings under rainfall conditions: A case study of an ion-adsorption rare earth mining area. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.116642 (2024).

Khoeurn, K., Sakaguchi, A., Tomiyama, S. & Igarashi, T. Long-term acid generation and heavy metal leaching from the tailings of Shimokawa mine, Hokkaido, Japan: Column study under natural condition. J. Geochem. Explor. 201, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gexplo.2019.03.003 (2019).

Fan, L. et al. Release of heavy metals from the pyrite tailings of huangjiagou pyrite mine: Batch experiments. Sustainability 8, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010096 (2016).

Liu, B., Sun, H., Peng, T. & Duan, T. Transport and transformation of uranium and heavy metals from uranium tailings under simulated rain at different pH. Environ. Chem. Lett. 18, 495–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-019-00951-4 (2020).

Geng, H. et al. Leaching behavior of metals from iron tailings under varying pH and low-molecular-weight organic acids. J. Hazard Mater. 383, 121136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121136 (2020).

Dong, Y., Chen, D. & Lin, H. Heavy metal release and acid generation during the oxidation of sulfide waste rock induced by ferric iron. Miner. Eng. 188, 107829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2022.107829 (2022).

Zhao, Y., Wang, P., Zhao, G. & Cui, Y. Metallogenic regularity and prospecting direction of Duobaoshan ore field, Heilongjiang Province, China. J. Jinlin Univ. (Earth Sci. Ed.) 41, 1676–1688 (2011).

Zhang, S. et al. Geology and mineralization of the Duobaoshan supergiant porphyry Cu-Au-Mo-Ag deposit (2.36 Mt) in Heilongjiang Province, China: A review. China Geol. 6, 100–136. https://doi.org/10.31035/cg2023006 (2023).

Rauret, G. et al. Improvement of the BCR three step sequential extraction procedure prior to the certification of new sediment and soil reference materials. J. Environ. Monitor. 1, 57–61 (1999).

Wenzel, W. W. et al. Arsenic fractionation in soils using an improved sequential extraction procedure. Anal. Chim. Acta 436, 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-2670(01)00924-2 (2001).

Sobek, A. A., Schuller, W. A., Freeman, J. R. & Smith, R. M. Field and laboratory methods applicable to overburden and mine soils. EPA 600/2-78-054 (1978), 203 (1978).

Plante, B., Bussière, B. & Benzaazoua, M. Static tests response on 5 Canadian hard rock mine tailings with low net acid-generating potentials. J. Geochem. Explor. 114, 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gexplo.2011.12.003 (2012).

Moon, Y., Song, Y. & Moon, H.-S. The potential acid-producing capacity and factors controlling oxidation tailings in the Guryong mine, Korea. Environ. Geol. 53, 1787–1797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-007-0784-9 (2008).

Finkelman, R. B. & Giffin, D. E. Hydrogen peroxide oxidation: an improved method for rapidly assessing acid-generated potential of sediments and sedimentary rock. Env & Coal Ass, Box 771785, Houston, TX 77215, USA. Vol.5, 521 (1986).

Nugraha, C. et al. Waste rock characteristics at tropical coal mine area: A case study of PT. Kaltim Prima Coal, Indonesia. Int. J. JCRM 5, 77–82. https://doi.org/10.11187/ijjcrm.5.77 (2009).

Su, K., Wang, Q., Li, L., Cao, R. & Xi, Y. Water quality assessment of Lugu Lake based on Nemerow pollution index method. Sci. Rep. 12, 13613. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17874-w (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Assessment of heavy metal pollution and water quality characteristics of the reservoir control reaches in the middle Han River, China. Sci Total Environ. 799, 149472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149472 (2021).

Lawrence, R. W. & Scheske, M. A method to calculate the neutralization potential of mining wastes. Environ. Geol. 32, 100–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002540050198 (1997).

Rodríguez, L., Gómez, R., Sánchez, V., Villaseñor, J. & Alonso-Azcárate, J. Performance of waste-based amendments to reduce metal release from mine tailings: One-year leaching behaviour. J. Environ. Manage. 209, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.12.031 (2018).

Al-Abed, S. R., Jegadeesan, G., Purandare, J. & Allen, D. Arsenic release from iron rich mineral processing waste: Influence of pH and redox potential. Chemosphere 66, 775–782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.07.045 (2007).

Rodríguez, L., Ruiz, E., Alonso-Azcárate, J. & Rincón, J. Heavy metal distribution and chemical speciation in tailings and soils around a Pb-Zn mine in Spain. J. Environ. Manage. 90, 1106–1116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.04.007 (2009).

Zhao, R. et al. Revealing the release and migration mechanism of heavy metals in typical carbonate tailings, East China. J. Hazard Mater. 464, 132978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.132978 (2024).

Nemati, K., Bakar, N. K. A., Abas, M. R. & Sobhanzadeh, E. Speciation of heavy metals by modified BCR sequential extraction procedure in different depths of sediments from Sungai Buloh, Selangor, Malaysia. J. Hazard Mater. 192, 402–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.05.039 (2011).

Zhou, Y., Short, M. D., Li, J., Fan, R. & Qian, G. Non-carbonate geochemical options for long-term sustainable acid and metalliferous drainage control at-source. Environ. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-019-8169-4 (2019).

Papadas, I. T., Katerinopoulos, L., Gianni, A., Zacharias, I. & Deligiannakis, Y. A theoretical and experimental physicochemical study of sulfur species in the anoxic lagoon of Aitoliko-Greece. Chemosphere 74, 1011–1017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.11.009 (2009).

Xu, N., Braida, W., Christodoulatos, C. & Chen, J. A Review of Molybdenum Adsorption in Soils/Bed Sediments: Speciation, Mechanism, and Model Applications. Soil Sediment Contam.: Int. J. 22, 912–929. https://doi.org/10.1080/15320383.2013.770438 (2013).

Frascoli, F. & Hudson-Edwards, K. A. Geochemistry, mineralogy and microbiology of molybdenum in mining-affected environments. Minerals 8, 42 (2018).

Sun, H., Chen, M., Zou, L., Shu, R. & Ruan, R. Study of the kinetics of pyrite oxidation under controlled redox potential. Hydrometallurgy 155, 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2015.04.003 (2015).

Strady, E. et al. Spatial variation and risk assessment of trace metals in water and sediment of the Mekong Delta. Chemosphere 179, 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.03.105 (2017).

Lu, C., Wu, Y., Hu, S., Raza, M. A. & Fu, Y. Mobilization and transport of metal-rich colloidal particles from mine tailings into soil under transient chemical and physical conditions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23, 8021–8034. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-016-6042-5 (2016).

El Azhari, A., Rhoujjati, A. & El Hachimi, M. L. Assessment of heavy metals and arsenic contamination in the sediments of the Moulouya River and the Hassan II Dam downstream of the abandoned mine Zeïda (High Moulouya, Morocco). J. Afr. Earth Sc. 119, 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2016.04.011 (2016).

Mahato, M. K., Singh, G., Singh, P. K., Singh, A. K. & Tiwari, A. K. Assessment of mine water quality using heavy metal pollution index in a coal mining area of Damodar River Basin, India. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 99, 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-017-2097-3 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Song, B. & Zhou, Z. Pollution assessment and source apportionment of heavy metals in soil from lead – Zinc mining areas of south China. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 109320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2023.109320 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Mr. Bo Yang from the Mining Research Institute of Baotou Steel (Group) Corp., China, for helping with the analysis of the mineralogical characterization of the samples.

Funding

This is work was financially supported by the Project of the China Geological Survey “Mineral Geological Survey for Strategic Emerging Industries” (DD20230034) and Institute of Mineral Resources, CAGS Research Fund (KK2416, JYYWF20181502).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guannan Liu and Zihui Ma wrote the main manuscript text; Rouxing Pan and Guannan Liu carried out the experiments; Guannan Liu, Dexian Li, Xiaosai Li, Ruiping Li and Yuanyi Zhao investigated and collected samples; Zunzhuang Ke prepared some figures; Huan Liu and Liming Dong are supervisor; Dexian Li revised and reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, G., Ma, Z., Li, D. et al. Insight into acid generation and the release risk of Cd, Cu and Mo from a high-latitude polymetallic mine in China. Sci Rep 15, 43841 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28724-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28724-w