Abstract

To address the severe issue of subgrade frost heave in season-frozen soil highway engineering in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (QTP) region, this studied investigated the frost-heaving characteristics (FHC) of subgrade soil with different initial water content (IWC) and fine particle content (FPC) under unidirectional freezing (UDF) and surrounding freezing (SDF) conditions through laboratory experiments. Furthermore, based on the thermo-hydro-mechanical (THM) coupling theory, variations in the temperature, moisture, and stress fields were analyzed numerically. The findings aim to provide a reference for the development of preventive and control measures against subgrade frost heave. The results show that the frost-heaving deformation (FHD) of subgrade soil can be divided into four stages: frost-shrinkage deformation stage, FHD rapid increase stage, FHD slow increase stage, and FHD stabilization stage; A sensitivity analysis suggests that controlling the IWC and FPC at approximately 8% and 9%, respectively, in the subgrade gradation design can effectively inhibit frost heave. Compared to the SDF condition, the UDF condition resulted in a more significant temperature gradient and a distinct freezing front. However, stress concentration points were observed under both freezing conditions

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Seasonal frozen soil is widely distributed in China, covering more than half of the country’s land area. As the world’s largest high-altitude frozen soil region, the QTP also contains extensive areas of frozen soil, primarily distributed within the southeastern alpine meadow landscapes. This region is a vital corridor connecting the QTP with the hinterland1,2. Consequently, highway engineering on the QTP inevitably faces challenges related to subgrade soil frost heave and thaw settlement. Under the negative temperature in winter, the water-ice phase transition occurs in the upper portion of subgrade soil, and water in the lower unfrozen soil layer migrates upward, accumulates, freezes, and expands its volume, resulting in the FHD of the pavement. In spring, as temperatures rise, the upper layer of subgrade soil thaws, causing pavement settlement3,4,5. Under long-term freeze-thaw cycles, frost heaving and thaw settlement are the fundamental causes of subgrade distress in seasonally frozen regions. Specifically, frost heaving not only induces uneven subgrade deformation and reduces pavement smoothness, but also leads to cracking in the pavement structural layer. This not only impairs driving safety and increases maintenance costs6,7,8, but also seriously hinders economic development and infrastructure construction in Tibet—underscoring the crucial need to study the Frost Heaving Characteristics (FHC) of subgrade soils in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (QTP) region. As early as the 17th century, the phenomenon of soil frost-heaving aroused the attention of scholars. In the early 20th century, water migration was recognized as the main cause of soil frost-heaving9. From the 1960 s to the 1980 s, significant progress was made in understanding soil frost heave mechanisms. Notably, the view that frost heave is caused by soil bending deformation due to water migration was disproven. Everett10 and Miller11 respectively proposed the first and second frost-heaving theories based on thermodynamics, which believed that the frost-heaving phenomenon can be attributed to surface tension response. When the temperature of the soil drops to near the freezing point, the flow of water in its internal pores is hindered by formed ice particles and drives water to flow from the warmer side to the colder side, which further leads to the formation of ice lenses and causes soil frost-heaving12. Consequently, water migration is widely recognized as the primary driver of soil frost heave13,14, fundamentally through the formation of ice lenses15.After hundreds of years of exploration and development, scholars’ understanding of the frost-heaving mechanism has been deepened, and many achievements have also been made in the research on soil’s FHC. Through laboratory experiments, Li et al.16 conducted frost-heaving simulation experiments on saturated coarse-grained soil with different FPC and found that the FHD of soil increases linearly with the increase of FPC. Wu et al.17 analyzed the effects of FPC, IWC, and other factors on the freezing depth of soil and total water intake, the results showed that the freezing depth of soil decreases with the increase of FPC, the curve of total water withdrawal with time changes from S shape to arch. Wang et al.18 investigated the effect of FPC on the frost-heaving resistance of coarse-grained soil and found that the FHD of soil shows an increasing trend with the increase of FPC when FPC is lower than 25%.From the above research results, it can be seen that the FPC in the soil is the main factor affecting its FHC19,20, the frost-heaving sensitivity of soil increases with the increase of FPC. This is because the porosity of soil is negatively correlated with the fractionation potential, and the increase of FPC will lead to a decrease in fractionation potential21,22,and at the same time, the increase of FPC changes the particle size distribution and liquid-plastic limit of soil, which has a significant impact on its strength and microstructure as well23.In addition, the effect of the IWC in the soil on its FHC is also significant24,25.

The process of soil frost-heaving involves complex physical and chemical phenomena, which is the result of the changes of temperature field, moisture field, and stress field in the soil as well as the interactions between multiple physical fields, while the laboratory test is limited by the conditions, a single study on a certain physical field cannot accurately describe the relevant characteristics of soil frost-heaving process, so the THM coupling process of soil during freezing can be simulated by finite element method26. Harlan27 pioneered the modern coupling analysis theory by establishing a water-thermal coupling model based on the theory of water migration in unsaturated permafrost. Li et al.28 established a coupled mathematical model of THM interactions during soil freezing and gave the corresponding discrete equations and solutions. Sun et al.29 proposed a coupled modeling method to simulate low-temperature THM processes associated with frozen soil and implemented it in a combined finite-discrete element method code for multi-physical field simulations. Water-heat migration in the soil and its induced stress redistribution are the main factors causing frost-heaving damage, and considering the THM multi-field coupling in numerical modeling is essential for the study of soil’s FHC, and provides a means to further investigate frost-heaving damage in engineering structures30,31.

The above studies on the FHC of soil are mostly limited to UDF of remolded soil, and there are fewer studies on other conditions of freezing, which are different from the actual situation in the field to some extent. In addition, the temperature boundary conditions during the tests are often dominated by constant temperatures, and the simulation of nonlinear temperature variations in natural conditions is less, resulting in a lower fit of the test results to the field.

However, despite the fruitful achievements of existing studies, there are still two major limitations regarding the frost heave characteristics of subgrades in practical engineering: one is the simplified research conditions—most current studies are limited to unidirectional freezing (UDF) of remolded soil, with little attention paid to surrounding freezing (SDF) conditions that better reflect actual working conditions such as road shoulders and slopes, which leads to discrepancies between test results and on-site realities; the other is the idealized boundary conditions—the temperature boundary conditions in tests are mostly constant, making it difficult to truly simulate the nonlinear temperature variation environment with huge day-night temperature differences on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (QTP), resulting in low fitting degree between test results and on-site conditions.

Given this, based on the highway reconstruction and expansion project of Gonjo to Markam in the Qamdo region of QTP, this paper studied the FHC of subgrade soil under both UDF and SDF conditions respectively, taking into account the two main influencing factors of initial water content (IWC) and fine particle content (FPC) through laboratory tests. Then, based on the theory of porous flow and thermal conduction of unsaturated soil, a two-dimensional numerical calculation model of THM coupling of subgrade soil was established to analyze the distribution and variation rule of temperature, moisture, and stress fields in the subgrade soil during freezing, and to reveal the difference of the THM field in the subgrade soil under different freezing conditions.

Project overview

The highway reconstruction and expansion project from Gonjo to Markam, located in Qamdo City, Tibet Autonomous Region of China, is an important highway construction project connecting Gonjo and Markam Counties, with a total length of 240 km, as shown in Figure.1. The project is located in the plateau planation meadow area between 4500 ~ 5000 m above sea level, which belongs to the typical high mountain meadow area highway project. The region has the lowest temperature in January, with an average temperature of −4 °C, and the highest temperature in July, with an average temperature of 15 °C, throughout the year, the highest temperature is 30 °C and the lowest is −25 °C. The average annual precipitation is 500 mm, with the rainy season from May to September and the dry season from October to April of the next year.

The Seasonal frozen soil is distributed along the route of the dependent project, especially in sections with high Fine Particle Content (FPC). These areas experience significant frost heaving in autumn and winter and thaw settling in spring and summer. This phenomenon severely degrades the physico-mechanical properties of the subgrade soil, leading to a decline in bearing capacity. During the operation stage of the completed Qingnidong to Gonjo reconstruction and expansion highway in this area, typical frost-heaving and thaw-settling diseases occurred (see Figure. 1), which seriously affected the normal use of the highway. Specifically, the frost heave distress is mainly manifested as uneven heaving of the pavement and longitudinal cracks caused by the freezing of subgrade moisture in winter. In contrast, the thaw settlement distress refers to local pavement depressions, reticulate cracks and ruts triggered by the insufficient bearing capacity of the soil subgrade after the melting of ice layers in spring. Figure 1 shows a typical road section where these two types of distresses coexist. In this case, studying the FHC of subgrade soil in the Gonjo to Markam highway reconstruction and extension project can provide theoretical reference for the prevention and control of FHD of subgrade soil in the QTP region while ensuring the safety of project operation, which has important research significance.

Test material and methodology

Physical properties of test soil sample

The test soil samples were obtained from the subgrade fill material of the aforementioned highway project (see Fig. 1). In accordance with the “Test Methods of Soils for Highway Engineering"32, a sieve analysis was performed; the results are presented in Fig. 2. As can be seen from the figure, the gradation composition of subgrade soil on site contains 11.0% of the fine particles group, 71.83% of the sand group, and 17.17% of the gravel group. According to the gradation composition, the type of soil taken on site is sand containing fine particles soil. The coefficient of nonuniformity \({C_u}\) of soil is 11.9(≥ 5), and the coefficient of curvature \({C_c}\) is 1.6(∈1 ~ 3), so the gradation of subgrade soil is good and meets the basic requirements of subgrade filler.

Qualitative analysis of the mineral composition of the soil samples was conducted using the X-ray diffraction (XRD) method. The results show that the mineral composition of the soil samples is dominated by quartz, with clay minerals mainly including kaolinite and illite, and trace amounts of hematite and rutile—these are the main reasons for the dark red color of the soil samples. No montmorillonite was detected in the analysis, and this result indicates that the soil has no expansibility and good water stability, providing a basis for the fact that its frost heave characteristics are mainly dominated by moisture migration and freezing conditions.

The composition and content of soluble salts in the test soil samples were tested by the chemical titration method and showed that the soluble salts in the soil are mainly calcium and magnesium compounds, in addition to bicarbonates, chlorides, and sulfates. The soluble salt content is 352.9 mg/kg, accounting for 0.035% of the total mass. According to the “Specifications for Design of Highway Subgrades”33, the threshold salt content for classifying a soil as weakly saline is 0.3%. This indicates that the salt content of the test samples is extremely low and insufficient to induce salt expansion during freezing.

Furthermore, in accordance with the “Specifications for Design of Highway Subgrades”33, the selection of subgrade filler shall comprehensively consider its mechanical properties and water stability. For subgrades in seasonal frozen soil regions, the content of fine particles group is a key indicator for evaluating frost heave sensitivity. Although the Specification does not specify a unified limit for the content of fine particles group (used to assess frost heave sensitivity) applicable to all soil types, it generally recommends the use of materials with good water permeability and low content of fine particles group. The “sand containing fine particles soil” (the soil sample used in this study) meets all the basic requirements for subgrade filler specified in the Specification in terms of mechanical indices.

To fully characterize the basic physical properties of the tested soil samples, key indicators such as particle density, liquid limit, and plastic limit were determined in accordance with “Specifications for Design of Highway Subgrades”33 The basic physical property indicators of the soil samples are summarized in Table 1.

Mechanical properties of test soil sample

Considering the limitations of the soil taken from the site, the gradation composition of the soil was proportionally designed to change the content of the fine particles group, and the content of other particle groups was adjusted according to the original proportion. The gradation composition is shown in Table 2. Maximum dry density, resilient modulus, and bearing ratio are important indicators of the mechanical properties of subgrade soil, which will significantly affect the FHC of soil. The mechanical indicators were tested by compaction test, resilience modulus test, and bearing ratio test, and the results are shown in Table 3.

Test apparatus

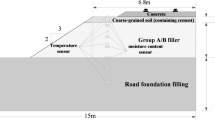

To simulate the large diurnal temperature fluctuations and significant climatic influences observed at the project site, two freezing conditions—UDF and SDF—were designed to study the FHC of subgrade soil during freezing, respectively corresponding to unidirectional cooling and surrounding cooling. UDF is used to simulate the unidirectional freezing caused by the cooling of road surface layers during winter. The test results can be utilized to optimize the design parameters of the lane section to reduce the risk of vertical frost heave. SDF is used to simulate the circumferential freezing of slopes due to surrounding frozen soil, which can help reveal the sensitivity of slope frost heave and guide the design of slope drainage and insulation measures. The test system is shown in Figure. 3.

The test system consists of three parts:

(1) The temperature control part mainly includes a low-temperature thermostatic bath and cooling copper tubes. The model of the low-temperature thermostatic bath is DC-1006, with a volume of 6 L and a temperature control range of −30 °C ~ 100 °C, industrial alcohol is used as the refrigerant, and it adopts the PID intelligent temperature control algorithm to realize programmed cooling by adjusting the refrigerant flow and compressor power. The outer diameter of the cooling copper tube is 8 mm, the inner diameter is 6 mm, and the thermal conductivity of copper is 401w/mk. The cooling copper tube is in close contact with the soil, and its high thermal conductivity ensures the efficient transfer of cold energy. During the test, the soil temperature is monitored in real time, and the output temperature of the thermostatic bath is dynamically calibrated, so that the error between the actual cooling rate of the soil and the set value (2 °C/2 h) is controlled within ± 0.3 °C/h.

(2) The main part includes a test specimen tube and a fixing device. To ensure the consistency of the initial test conditions, all specimens are placed in a constant - temperature environment of (15 ± 1) °C and left to stand for more than 12 h after preparation, so as to ensure that the internal temperature of the specimens is uniform and reaches the preset initial temperature. The test specimen tube is made of acrylic plexiglass, with a thickness of 15 mm, an inner diameter of 0.27 m, and an outer diameter of 0.3 m. According to the compaction standard(95%) of field subgrade, the soil samples are prepared by the layered compaction method, and to ensure the effect of compaction, the fixing device is designed to fix the test specimen tube, and a wooden solid pad is placed at the lower part of the tube. Under the UDF condition, a height-to-diameter ratio of 1.8:1 was adopted, with the soil sample having a height of 0.45 m and a diameter of 0.25 m. This design ensures the full development of a vertical temperature gradient, thereby simulating the freezing process of the main subgrade; Under the SDF condition, equal-dimension samples were used, where both the height and diameter of the soil sample are 0.25 m. This configuration guarantees the symmetrical distribution of the cold source, enabling the simulation of radial freezing in the subgrade shoulder slope.

(3) The data acquisition part includes displacement sensors, displacement collectors, and a laptop. The displacement sensor model is a KTR-150 mm self-recovering displacement sensor (accuracy ± 1%, sensitivity 1), with a measuring range of 150 mm. The displacement collector includes a USB2.0–4−20AD data collector and a SQL 2000 PERSONAL data collection library, which are connected to the displacement sensor to collect the FHD of the subgrade soil during freezing in real-time.

Test scheme

The main influencing factors considered in this paper for the frost-heaving tests include FPC, IWC, freezing condition, and cooling rate. The gradients of these variables were determined based on the following considerations: For FPC in the subgrade soil, adjustments were made with a 2% interval centered on the natural gradation (11.0%) of the on-site soil samples, so as to cover the common range in engineering practice and ensure the significance of its influence on frost heave. As for IWC, it was varied with a 2% gradient based on the results of the laboratory compaction test, aiming to represent typical working conditions where the water content is lower than, close to, and higher than the optimal water content. Meanwhile, the cooling rate and its corresponding scheme were designed with reference to the diurnal temperature difference characteristics of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, which helps to simulate the real environment and ensure the sufficient occurrence of water-ice phase transition. In the specific frost-heaving tests, a closed system was adopted without considering external water recharge, and the initial temperature of all specimens was uniformly controlled at (15 ± 1) °C before the tests started. The freezing condition included UDF and SDF, respectively corresponding to the subgrade lane part and the shoulder slope part. Referring to the “Test Methods of Soils of Highway Engineering”32, the test adopted an intermittent cooling scheme, including three constant temperature stages and two cooling stages, with the lowest temperature of −20°C and the duration of 60 hours, as shown in Figure. 4. Specifically, the scheme started with a constant temperature of 0 °C, lasting for 14 hours; then, it cooled down to −10°C at a rate of 2 °C per 2 hours and maintained the constant temperature for 14 hours; after that, it cooled down again to the final temperature of −20°C at a rate of 2 °C per 2 hours and maintained the constant temperature at this temperature until the total duration reached 60 hours. The constant temperature stage allowed sufficient time for the formation of a temperature gradient in the soil, and the water-ice phase transition occurred fully. In the cooling stage, the cooling rate was 2°C/2 h to avoid temperature control errors in the low-temperature thermostatic bath and to ensure sufficient heat exchange between the soil and the outside world. The specific test scheme is shown in Table 4.

Test results and analysis

Analysis of FHD

Effect of IWC

Under the condition of the same FPC and different IWC, the variation curves of FHD of subgrade soil with time during UDF and SDF are shown in Figs. 5 and 6.

As can be seen from Figs. 5 and 6:

(1) Whether it is UDF or SDF, when the FPC in the soil is the same, the IWC determines the FHD of the soil. An increase in IWC resulted in greater final FHD and more pronounced frost-shrinkage deformation. The reason is that the higher the IWC in the soil, the greater the volume expansion when water freezing, the greater the displacement of particles in the soil, and the more significant the FHD of the soil. In addition, when the IWC in the soil exceeds the optimal water content, the degree of compaction of the soil gradually decreases, and the pores in the soil become large so that the frost-shrinkage deformation of soil is more significant in the early stage of freezing.

(2) During the UDF and SDF processes, the FHD of soil can be divided into four stages: frost-shrinkage deformation stage, FHD rapid increase stage, FHD slow increase stage, and FHD stabilization stage. Specifically, as the temperature decreases, relative sliding occurs between soil particles. At this point, the temperature has not yet reached the critical temperature for phase transition, so no phase transition takes place in the pore water. Moreover, the sliding particles fill the air voids inside the soil, which in turn leads to a decrease in soil volume and the occurrence of frost-shrinkage deformation, and the deformation slope is negative at this stage. It is worth noting that this frost-shrinkage deformation only occurs under specific working conditions — its deformation magnitude is small, its duration is short, and it is not obvious under most working conditions. As the temperature inside the soil continues to decrease and reaches the critical temperature of phase transition, the water-ice phase transition occurs, and the pore ice gradually fills the pores inside the soil, causing displacement between soil particles that is opposite to shrinkage, which is macroscopically manifested as a rapid increase in FHD, and the deformation slope shows the maximum positive value at this stage; As time goes on, the soil freezes more fully and the FHD increases lowly, and the slope of the deformation curve decreases significantly but remains positive at this stage; when the pores in the soil are completely filled with ice, the soil particles gradually do not shift and the FHD tends to stabilize, and the slope of the deformation curve approaches zero at this stage. Comparing the FHD curves of soil under both freezing conditions, the FHD increase of the soil at SDF is earlier than that at UDF. The reason is that the contact area between the cooling source and the soil is larger during the SDF process, and the heat released from the water phase transition in the soil is rapidly transferred, which is conducive to the formation of pore ice.

(3) The IWC of soil affects the increase of its FHD. FHD is a process of changing the soil volume due to the phase transition of water in the soil. The water-ice phase transition releases heat, which inhibits the further occurrence of phase transition, so the higher the IWC in the soil, the more heat is released, and the more significant the inhibitory effect. But when the IWC is less than the optimal water content range (8.4% − 9.0%, see Table 2), the adsorption effect of soil particles on water is enhanced, the water-ice phase transition needs to overcome the adsorption effect between soil particles, and the energy is derived from the temperature potential. When the temperature potential reaches a certain value, the water will undergo the phase transition, manifested as delayed FHD time and a smaller deformation amount. Therefore, when the FPC in the soil is the same, the time sequence of soil FHD is: IWC 10%, IWC 12%, IWC 8%.

Effect of FPC

Under the condition of the same IWC and different FPC, the variation curves of FHD of subgrade soil with time during UDF and SDF are shown in Figs. 7 and 8.

As can be seen from Figs. 7 and 8:

(1) Under both freezing conditions, when the IWC of the soil is the same, the more FPC, the more significant the FHD of the soil. The reason is that with the increase of FPC in the soil, the soil porosity decreases, and the displacement of soil particles caused by the freezing of soil with the same IWC increases, resulting in a more significant FHD of soil.

(2) Under both freezing conditions, when the IWC of the soil is the same, the FPC affects the initial FHD time of the soil, and the initial FHD time of the soil with a FPC of 7% is significantly later than that of the soil with other FPC. The reason is that under the same conditions of IWC when the FPC in the soil is low, the specific surface area is small, the bound water content is relatively reduced, and the free water content is relatively increased. The effect of free water phase transition heat release on inhibiting freezing is enhanced, resulting in the initial FHD time of the soil being delayed.

Analysis of FHDR

Due to the different freezing depths of the soil, only the amount of FHD cannot describe the differences in soil FHD under different experimental conditions, and the FHDR is usually used to describe the strength of soil FHD, which is an important parameter indicator for studying the changes of physical phenomenon in the soil during the frost-heaving process. The calculation formula is:

Where \(\eta\) is the frost-heaving deformation rate (%), \(\Delta h\) is the frost-heaving deformation (mm), \({H_f}\) is the freezing depth (mm).

According to the results of laboratory tests, the characteristic values of subgrade soil frost-heaving under both UDF and SDF conditions are shown in Table 5.

According to Table 4, the relationship between IWC and FHDR, the relationship between FPC and FHDR, and the relationship between IWC, FPC, and FHDR under both UDF and SDF conditions respectively can be obtained, which are shown in Figs. 9 and 10.

As can be seen from Figures.9 and 10:

(1) Under both freezing conditions, the FHDR of the soil is positively correlated with the FPC and IWC in the soil, when the single variable is changed, the FHDR changes obviously.

(2) Under both freezing conditions, the slope of the trend line between IWC and FHDR is significantly greater than that of the trend line between FPC and FHDR. Therefore, the influence of water content (IWC) on the FHDR is more significant than that of fine particle content (FPC).

Evaluation of FHC of subgrade soil

According to the “Technical Specifications for Construction of Highway Subgrades”34, the evaluation standards for frost-heaving of sandy soil are shown in Table 6.

Combined with Table 5 and the above test results and analysis, it can be seen that whether it is UDF or SDF, when the IWC of the soil is 8%, the FHDR of the soil with different FPC is less than 1%, which is the no frost-heaving soil; When the IWC is 10% and 12%, the FHDR of soil with different FPC is basically between 1% and 3.5%, which is the weak frost-heaving soil of grade II. However, under the SDF condition, when the FPC in the soil is 13% and the IWC is 12%, the FHDR is 6.11%, which is the strong frost-heaving soil of grade IV. In addition, the FHDR of the soil increases with the increase of FPC in the soil under the UDF condition, while the FHDR of the soil is the smallest when the FPC is 9% under the SDF condition.

In summary, the IWC and FPC are important parameters affecting the frost-heaving strength of subgrade soil in the QTP region. Therefore, during subgrade construction in this area, under the condition of ensuring compactness, the IWC in the soil should be controlled near the optimal water content of 8%, which can be achieved through mature construction techniques such as on - site stewing and airing of materials. The FPC in the soil should be controlled at about 9%, and drainage precautions should be taken, which can effectively reduce the influence of IWC and FPC on the frost-heaving of subgrade soil. However, during road operation, the water content of subgrade soil will change due to the influence of factors such as groundwater, precipitation, and snowmelt. Therefore, in order to ensure its long - term frost - heaving resistance, in addition to strictly controlling the initial state during filling, it is also necessary to combine with perfect waterproof and drainage measures (such as waterproof geotextiles and drainage blind ditches) to isolate external water supply as much as possible and maintain the subgrade in a relatively dry state, thereby ensuring the long - term effectiveness of the control indicators mentioned in this paper.

Numerical analysis

Model assumptions and governing equations

In this paper, COMSOL Multiphysics numerical simulation software was used to establish two-dimensional calculation models of UDF and SDF, respectively, and to study the characteristics of temperature, moisture, and stress fields in the subgrade soil during freezing based on the coupling of THM fields. The numerical model was established based on the following assumptions for the THM coupling: (1) Soil is a homogeneous isotropic body; (2) Water migration in the soil is carried out in liquid form; (3) Soil particles, ice, and water are incompressible; (4) The frozen and unfrozen parts of the soil are porous elastomers; (5) The hydraulic conductivity of unfrozen water in the soil is constant, and the hydrodynamic properties are isotropic; (6) The migration of unfrozen water in the soil conforms to Darcy’s law; (7) The heat transfer in the soil is by thermal conduction, ignoring other methods of heat transfer.

During the freezing process, considering the heat conduction of soil particle skeleton and water and the role of ice-water phase transition, ignoring the role of water vapor evaporation and chemical reaction, the basic Eq35. of the temperature field is expressed as follows:

Where\(C\) is the soil heat capacity,\(\lambda\) is the soil thermal conductivity, \(L\) is the latent heat of water-ice phase transition, \(\rho\) is the density of soil, \({\rho _i}\) is the density of ice, \(T\) is temperature, \({\theta _i}\) is the volumetric ice content, \(t\) is time.

Hydrodynamics theory is used to describe the water migration in the soil during the freezing process, it is considered that the freezing process of the soil is a process of the interaction of three physical fields of heat, water, and force, namely, heat exchange, water migration and water-ice phase transition, and the three physical changes constrain and influence each other, with the Eq. 35 form as:

Where \({\theta _u}\) is the volumetric unfrozen water content, \(D({\theta _u})\) is the diffusivity of unfrozen water, \(k({\theta _u})\) is the hydraulic conductivity of soil, \({\rho _w}\) is the density of water.

In addition, the frost-heaving stress is generated in the soil during the freezing process, which can reflect the coupling relationship of THM fields in the soil. The frost-heaving stress includes in-situ water frost-heaving stress and migrated water frost-heaving stress, generated by the original part of the water in the pore and the migrating water freezing expansion, respectively. Therefore, the calculation of frost-heaving stress in the soil during the freezing process is a problem of calculating the stress with the known initial strain. The volume strain of soil caused by the water-ice phase transition is expressed35 as:

Where \(n\) is the initial porosity of soil, \({\theta _i}=1.09({\theta _0} - {\theta _u})+1.09\Delta \theta\).

Therefore, the soil volumetric strain caused by water-ice phase transition is expressed35 as:

Where \({\theta _0}\) is the initial volumetric water content, \(\Delta \theta\) is the volumetric migrating water content.

Regarding \({\varepsilon _y}\) as the initial strain, the stress-strain relationship of the soil element is expressed as:

Where [D] is the elastic matrix, \(\{ \sigma \} =\{ {\sigma _x},{\sigma _z},{\tau _{xz}}\}\),\(\{ \varepsilon \} =\{ {\varepsilon _x},{\varepsilon _z},{\gamma _{xz}}\}\),\(\{ {\varepsilon _0}\} =\{ {\varepsilon _v},{\varepsilon _v},0\}\).

To solve the partial differential equation, it is necessary to determine the relationship between the volumetric pore ice content and volumetric unfrozen water content in the soil, introducing the solid-liquid ratio as the coupling Eqs. 33,36 expressed as follows:

where \({B_I}\) is the solid-liquid ratio, \({T_{trans}}\) is the critical phase transition temperature.

Therefore the linkage equation between volumetric pore ice content, volumetric unfrozen water content, and temperature during soil freezing is:

At the same time, a two-dimensional step function H was established to characterize the water-ice phase transition process during freezing, and H was expressed by the Heaviside function as:

The function expression is:

Where \(dT\) is the transition gap.

Note: Equation (6) is applicable to the scenario where \({T_{trans}}\) < 0 °C, and its parameters are derived from the calibration of test results. This formula characterizes the trend that the proportion of the solid phase increases with decreasing temperature within the freezing temperature interval (T < \({T_{trans}}\)).

Calculation parameters

Based on the results of the laboratory tests and field investigations, and referring to the relevant research results in the QTP region37,38,39,40, the parameters involved in the numerical model calculations are shown in Table 7.

Among the aforementioned model parameters, the thermal conductivity, density, and porosity of the soil are directly determined through laboratory tests. The initial temperature and initial volumetric water content are the initial conditions set for the experiment. The density of water, density of ice, and latent heat of phase transition are well-recognized physical constants. Parameters such as elastic modulus, Poisson’s ratio, hydraulic conductivity, diffusivity of unfrozen water, and solid-liquid ratio are referenced from empirical values in relevant research literature on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. This ensures that the model parameters can reflect the characteristics of the local soil.

Numerical models and boundary conditions

The dimensions of the numerical model were consistent with the test soil samples. Under the UDF condition, the model was a rectangle with a height of 0.45 m and a width of 0.25 m. Under the SDF condition, the model was a rectangle with a height and width of 0.25 m. The numerical model was meshed with free-section triangles under both freezing conditions, as shown in Figure. 11. Local refinement was applied to the model boundaries, especially the corner areas prone to stress concentration, to capture physical field gradients more accurately. Finally, the unidirectional freezing (UDF) model and surrounding pressure freezing (SDF) model generated approximately 1800 and 1300 computational elements, respectively. This mesh density was determined based on a comprehensive trade-off between the model’s geometric scale, expected physical field gradients, and computational efficiency. The displacement field obtained from calculations using the current mesh was highly consistent with the experimental measured values, indicating that the current mesh scheme can effectively reproduce the macroscopic frost heave mechanical behaviors of interest in this study.

The temperature of the cooling source under both freezing conditions was carried out according to the temperature change of the laboratory test, which could be expressed as a piecewise function:

Where \(t\) is the time(h).

Under both freezing conditions, the initial temperature in the model was 15 °C, and the initial volumetric water content was 25%. Except for the cooling source boundary, the other directions were considered zero flux boundaries with no heat loss, and no water supply in all directions. The bottom of the model was subjected to the full constraints and limited to a displacement of 0 on both sides. In the UDF numerical model, 6 measurement points were arranged along the vertical center line. In the SDF numerical model, 4 measurement points were arranged along the horizontal center line due to the symmetry of cooling sources on both sides. The boundary conditions and measurement points of the numerical model are shown in Figure. 12.

Model validation

To verify the validity of the numerical model, the measured and simulated values of the upper boundary displacement on the soil layer under both freezing conditions were compared, as shown in Figure.13.

As can be seen from Figure.13, the trends of the measured and simulated displacements of the upper boundary on the soil layer under both freezing conditions are the same basically, and the differences between the two mainly occur in the frost-shrinkage deformation stage and the FHD increase stage. At the initial freezing stage, the soil in the numerical model does not undergo frost-shrinkage deformation, which is caused by the model assumption that the soil particles are incompressible. In the FHD increase stage, the measured values are always larger than the simulation values and the initial FHD time is earlier, because the numerical model assumes that the hydraulic conductivity of unfrozen water in the soil is a constant and does not take into account the heat transfer mode other than thermal conduction, there are differences with the actual freezing process of the soil. When the freezing is complete, the simulated displacement value is 2.89 mm and the measured displacement value is 2.85 mm under the UDF condition, and the simulated displacement value is 4.79 mm and the measured displacement value is 4.98 mm under the SDF condition. The errors under both freezing conditions are less than 4%, which falls within the acceptable range for numerical analysis in geotechnical engineering. Therefore, this numerical model exhibits high computational accuracy and reliability, and fully meets the requirements for studying the variation laws of the THM fields in subgrade soil.

It should be noted that, due to the limitations of experimental conditions, this study failed to directly measure the spatiotemporal distribution of volumetric water content and unfrozen water content inside the sample, and thus cannot provide direct verification for the calculation results of these two parameters. Nevertheless, this study supports the rationality of the moisture field calculation results through the following indirect evidence:

(1) The model’s accurate prediction of macroscopically observable quantities (final frost heave displacement) indicates that the internal hydro-thermal-mechanical (THM) coupling process driving this phenomenon is reliable on the whole;

(2) The model’s accurate reproduction of the temperature field provides a solid foundation for the calculation of unfrozen water content based on temperature functions;

(3) The calculation results exhibit distribution characteristics consistent with physical laws (e.g., the sharp gradient at the freezing front), which are highly consistent with theoretical expectations.

In summary, despite its limitations, this model still holds important reference value in revealing the core laws of moisture field distribution.

Analysis of results

Analysis of temperature field

During the UDF and SDF processes, the results of the temperature field in the subgrade soil are shown in Figures.14 and 15.

As can be seen from Figures.14 and 15:

(1) Under both freezing conditions, the initial temperature in the soil is evenly distributed without significant temperature difference. With the increase of freezing time, the temperature in the soil decreases gradually, and the closer the distance from the cooling source, the greater the temperature drop. During the UDF process, a temperature gradient is formed in the soil that increases from top to bottom along the vertical direction, and the 0 °C temperature line gradually drops, indicating that the freezing depth is gradually increasing and reaches the maximum value of 0.23 m when the freezing is completed. During the SDF process, the temperature difference between the inside and outside of the soil is gradually smaller. When the freezing is complete, the temperature difference along the horizontal direction is less than 0.5 °C, and there is no significant temperature gradient.

Curve of Temperature Change in Soil: (a) Temperature Distribution in the Vertical Direction under the UDF Condition, (b) Temperature Changes with Time under the UDF Condition, (c) Temperature Distribution in the Horizontal Direction under the SDF condition, (d) Temperature Changes with Time under the SDF Condition.

(2) The variation form of the cooling source temperature determines the variation form of temperature in the soil. During the freezing process, the temperature of measuring points in the soil decreases periodically, and the variation period is the same as that of the cooling source temperature, which is 24 h. As the distance from the cooling source increases, the cooling rate at the measurement points decreases gradually and the periodicity diminishes. During the UDF process, the temperature variation of the lower measuring point lags behind that of the upper measuring point. During the SDF process, the temperature variation of the measuring points in the middle position lags behind that of the measuring points on both sides. This is due to the freezing process of soil is a heat exchange process with the outside world, and the closer the distance from the cooling source is, the shorter the heat transfer path is, and the faster the temperature drop is.

Analysis of moisture field

During the UDF and SDF processes, the results of the volumetric unfrozen water content in the subgrade soil are shown in Figures.16 and 17.

As can be seen from Figs. 16 and 17:

(1) Under both freezing conditions, the volumetric unfrozen water content in the soil decreases significantly with the increase in freezing time. The closer the distance to the cooling source, the lower the temperature, and the more obviously the volumetric unfrozen water content decreases. During the UDF process, the distribution of volumetric unfrozen water content in the soil has a significant interface, with a gradient distribution of the volumetric unfrozen water content above the interface and no significant difference in the distribution of the volumetric unfrozen water content below the interface, which is known as the freezing front. Furthermore, the position of the volumetric unfrozen water content of 0 dropped gradually, indicating that the freezing front dropped gradually along the vertical direction and the freezing depth increased gradually. During the SDF process, the volumetric unfrozen water content changes obviously along the distribution of horizontal direction. At 24 h of freezing, the temperature in the soil is distributed with a trend of high in the middle and low on both sides, and the water-ice phase transition is intense, resulting in the volumetric unfrozen water content in the middle position being significantly higher than that on both sides. In the subsequent freezing process, the temperature difference in the soil gradually reduces, and there is no obvious gradient change, so the volumetric unfrozen water content in the soil is uniformly distributed.

(2) Under both freezing conditions, there is a critical point in the change of the volumetric unfrozen water content with time. Before the critical point, the volumetric unfrozen water content has no significant change, but after the critical point, the volumetric unfrozen water content decreases rapidly. During the UDF process, the cooling source is located in the upper boundary of the soil, the farther the measurement point is from the cooling source, the slower the temperature change and the slower the freezing of pore water. During the SDF process, the cooling source is located at the boundary of both sides of the soil, and since there is no significant temperature gradient in the soil, the volumetric unfrozen water content decreases rapidly during 12 h ~ 24 h of freezing, and the water-ice phase transition occurs violently.

It should be noted that the staged rapid decline and plateau exhibited by the volumetric unfrozen water content curve in Fig. 17 are the numerical manifestation of the water-ice phase change process, reflecting the inhibitory effect of latent heat release during phase change on temperature decrease, rather than instability in model calculation. This calculation result is obtained based on the verified numerical model with sufficient accuracy in the “Model Validation” section (with a displacement simulation error < 4%), and can reliably reflect the overall variation trend and distribution law of unfrozen water content.

Curve of Volumetric Unfrozen Water Content Change in Soil: (a) Unfrozen Water Distribution in the Vertical Direction under the UDF Condition, (b) Unfrozen Water Changes with Time under the UDF Condition, (c) Unfrozen Water Distribution in the Horizontal Direction under the SDF condition, (d) Unfrozen Water Changes with Time under the SDF Condition.

Analysis of stress field

During the UDF and SDF processes, the results of the displacement and stress fields in the subgrade soil are shown in Figures.18 and 19.

As can be seen from Figures.18 and 19:

(1) During the UDF process, the FHD of soil increases gradually and the deformation range also gradually expands. When the freezing is completed, two relatively obvious deformation zones are formed in the soil, the height of the upper deformation zone ranges from 0.35 to 0.45 m, and the height of the lower deformation zone ranges from 0.15 to 0.25 m, and the value of maximum deformation occurs at the upper boundary, which is 2.89 mm. During the SDF process, the displacements occur throughout the soil, but due to the constraints of boundary conditions on both sides, the displacement of the upper layer of soil is more significant, and also the maximum FHD occurs at the upper boundary, which is 4.79 mm when the freezing is completed.

(2) Under both freezing conditions, there are stress concentration points exist in the soil, which located at the left and right corner points of the upper boundary of the soil, this is because the process of soil freezing is a process of volumetric expansion and deformation, and the numerical model restricts the lateral displacement of soil, which is only manifested as a unidirectional deformation so that there is a stress concentration phenomenon in the soil. Although geometric corner points exhibit the numerical characteristic of stress singularity, considering that their formation mechanism is clear (caused by strong boundary constraints) and consistent with the potential cracking patterns observed in experiments, while the model mesh has been refined and verified by displacement (error < 4%), it is thus considered that this stress concentration is mainly a true mechanical response induced by physical constraints. With the increase of freezing time, the deformation of the upper boundary increases gradually, and the stress at the concentration point also increases gradually, reaching the maximum value when the freezing is completed. During the UDF process, the range of stress distribution in the soil increases gradually along the vertical direction. When the freezing is completed, there exists a more significant stress effect within 0.3 m of the vertical direction of the soil. During the SDF process, the stress effect is generated throughout the soil as there is no significant temperature gradient.

This stress concentration phenomenon is of great engineering significance and is a potential cause of transverse cracks on the subgrade surface. Under the action of frost heave, the subgrade surface bears tensile stress, and the stress concentration at the corner points makes the tensile stress in this area easily exceed the tensile strength limit of the material first, leading to the initiation and propagation of cracks.

The results of this study show that higher initial water content (IWC) and fine particle content (FPC) will increase this risk. As shown in the Analysis of FHDR section, the increase of IWC and FPC will significantly increase the frost heave deformation rate (FHDR), which means stronger frost heave stress, thus worsening the stress concentration state at the corner points.

Therefore, in the highway engineering on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, the anti-cracking design of the subgrade section needs to be focused on. To mitigate this risk, the following engineering measures can be considered:

(1) Material control: Strictly control the IWC and FPC of subgrade fillers (such as controlling them at about 8% and 9% respectively) to suppress frost heave stress from the source.

(2) Structural design: Optimize the cross-sectional geometry (such as setting arc-shaped road shoulders) to reduce the acute angle effect, or lay geogrids and other reinforced materials to disperse stress.

In conclusion, the numerical simulation clearly reveals the law of stress concentration generated at the boundary constraints of subgrade soil during the freezing process. This law is consistent with the frost heave behavior observed in laboratory tests and provides a key basis for understanding the mechanism of subgrade frost heave cracking and formulating prevention and control measures.

Conclusions

This study comprehensively investigated the FHC of subgrade soil in the QTP region through laboratory freezing tests, and combined with the numerical method to analyze the variation rules of the temperature field, moisture field, and stress field in the subgrade soil during the freezing process. The following conclusions are drawn:

(1) Under both UDF and SDF conditions, the FHD of subgrade soil can be divided into four stages: frost-shrinkage deformation stage, FHD rapid increase stage, FHD slow increase stage, and FHD stabilization stage, which reveals the similar phase transition and deformation evolution mechanism under different freezing modes; The FPC and IWC in the subgrade soil affect its FHC such as maximum FHD, maximum frost-shrinkage deformation, and initial FHD time of soil, the essence of which is regulating the water migration capacity and total latent heat of phase transition.

(2) Under both freezing conditions, the FHDR of subgrade soil is positively correlated with the FPC and IWC in the soil, and water is the primary factor governing frost heave sensitivity. Under the same conditions of FPC and IWC, the FHDR of subgrade soil during the SDF process is greater than that during the UDF process. This is attributed to the larger cold source contact area in the SDF process, which facilitates more sufficient water migration and phase transition.

(3) FPC and IWC are important parameters affecting the strength of subgrade soil frost-heaving, and their mechanism of action lies in controlling the pore structure of the soil and the content of freezable water. When designing the gradation of subgrade soil in the QTP region, the IWC in the soil should be controlled at around the optimal water content of 8%, and the FPC should be controlled at around 9%. This dual-control index can effectively inhibit water migration and the growth of ice lenses. Theoretically, the frost-heaving hazard of subgrade soil in this area can be minimized.

(4) The variation form of the external temperature determines the variation form of temperature in the subgrade soil, and both decrease with the same periodic rule. Under the UDF condition, the temperature in the subgrade soil is distributed along the gradient increasing vertically from top to bottom, and there is an obvious freezing front in the soil. This temperature gradient is the fundamental reason driving the directional migration of water. The volumetric unfrozen water content above the freezing front increases from top to bottom along the vertical direction, with little change in volumetric unfrozen water content below the freezing front. Under the SDF condition, the temperature in the subgrade soil is distributed along the horizontal direction with a pattern of high in the middle and low on both sides, no freezing fronts exist in the soil, and the volumetric unfrozen water content on both sides are slightly higher than that in the middle position when the freezing is completed.

(5) The freezing condition determines the distribution rules of the physical field and stress field in the subgrade soil. During the UDF process, the distribution rules of the physical field in the subgrade soil are obvious along the vertical direction, and there are two obvious deformation zones. During the SDF process, the distribution rules of the physical field in the subgrade soil are obvious along the horizontal direction, and deformation occurs throughout the soil. Influenced by the boundary conditions, the stress concentration phenomenon exists at the left and right corners of the upper boundary of subgrade soil under two freezing conditions. This reveals that the frost-heaving volume expansion under rigid constraints is the internal mechanism causing cracking in engineering structures.

(6) It is important to note that the conclusions of this study are based on laboratory tests using remolded soil and numerical models assuming homogeneous, isotropic conditions. Consequently, their applicability to in-situ undisturbed soils and more complex boundary conditions necessitates further verification.

Data Availability

The raw data related to this study will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- B:

-

Empirical parameter

- \({B_I}\) :

-

Solid-liquid ratio

- C:

-

Soil heat capacity

- \({H_f}\) :

-

Freezing depth (mm)

- L:

-

Latent heat of water-ice phase transition

- T:

-

Temperature

- \({T_{trans}}\) :

-

Critical phase transition temperature

- \(dT\) :

-

Transition gap

- \(\Delta h\) :

-

Frost-heaving deformation (mm)

- n:

-

Initial porosity of soil

- t:

-

Time

- \(\eta\) :

-

Frost-heaving deformation rate (%)

- \(\lambda\) :

-

Soil thermal conductivity

- \(\rho\) :

-

Density of soil

- \({\rho _i}\) :

-

Density of ice

- \({\rho _w}\) :

-

Density of water

- \({\theta _i}\) :

-

Volumetric ice content

- \({\theta _u}\) :

-

Volumetric unfrozen water content

- \({\theta _0}\) :

-

Initial volumetric water content

- \(\Delta \theta\) :

-

Volumetric migrating water content

- \(D({\theta _u})\) :

-

Diffusivity of unfrozen water

- \(k({\theta _u})\) :

-

Hydraulic conductivity of soil

References

Liu, L. et al. Hydrological impacts of near-surface soil warming on the Tibetan plateau. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 31 (2), 324–336. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp.2049 (2020).

Wu, G., Xie, Y., Wei, J. & Yue, X. Freeze-thaw erosion mechanism and preventive actions of highway subgrade soil in an alpine meadow on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Eng. Fail. Anal. 143, 106933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106933 (2023).

Tai, B., Yue, Z., Qi, S. & Wang, P. Experimental and numerical investigation on thermal-moisture-mechanical behaviors on a new anti-frost cutting bed of high-speed railway in deep seasonally frozen ground regions under extreme climate. Comput. Geotech. 136, 104251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2021.104251 (2021).

Wu, G., Xie, Y., Wei, J. & Yue, X. Water migration in subgrade soil under seasonal freeze-thaw cycles in an alpine meadow on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. J. Mt. Sci. 19 (6), 1767–1781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-021-7270-9 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Experimental study on heating performance of a solar Circulating heated embankment system for the treatment of Frost heave disease in seasonally frozen regions. Sol. Energy. 248, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2022.10.053 (2022).

Huber, S., Henzinger, C. & Heyer, D. Influence of water and Frost on the performance of natural and recycled materials used in unpaved roads and road shoulders. Transp. Geotechnics. 22, 100305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2019.100305 (2020).

Miao, Q., Niu, F., Lin, Z., Luo, J. & Liu, M. Comparing Frost heave characteristics in cut and embankment sections along a high-speed railway in seasonally frozen ground of Northeast China. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 170, 102921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2019.102921 (2020).

Ji, Y. et al. Effect of anionic polyacrylamide polymer on frost heave mitigation and its implication for frost-susceptible soil. Polymers 15(9), 2096. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15092096 (2096).

Taber, S. The mechanics of Frost heaving. J. Geol. 38 (4), 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1086/623720 (1930).

Everett, D. H. The thermodynamics of Frost damage to porous solids. Trans. Faraday Soc. 57, 1541–1551. https://doi.org/10.1039/TF9615701541 (1961).

Miller, R. D. Freezing and heaving of saturated and unsaturated soils. Highway Res. Rec. 393 (1), 1–11 (1972). https://doi.org/Onlinepubs/hrr/1972/393/393-001.pdf

Liu, L., Wang, X., Chen, H. & Wan, C. Microstructure-based modelling of drying shrinkage and microcracking of cement paste at high relative humidity. Constr. Build. Mater. 126, 410–425. https://doi.org/1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.09.066 (2016).

Cao, W., Sheng, Y., Wu, J. & Li, J. Spatial variability and its main controlling factors of the permafrost soil-moisture on the north-ern-slope of Bayan Har mountains in Qinghai-Tibet plateau. J. Mt. Sci. 14 (12), 2406–2419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-017-4467-z (2017).

Kraatz, S. et al. Improving SMAP freeze-thaw retrievals for pavements using effective soil temperature from GEOS-5: evaluation against in situ road temperature data over the US. Remote Sens. Environ. 237, 111545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111545 (2020).

O’Neill, K. & Miller, R. D. Exploration of a rigid ice model of Frost heave. Water Resour. Res. 21 (3), 281–296. https://doi.org/10.1029/WR021i003p00281 (1985).

Li, A. et al. Experimental measurement and numerical simulation of Frost heave in satu-rated coarse-grained soil. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 137, 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2017.02.008 (2017).

Wu, Q., Mao, X., Zhao, Y., Zhou, H. & Huang, W. Model experiments to study the hydrothermal variation and resilient modulus of soil subgrade subjected to freeze-thaw conditions. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16, e01145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01145 (2022).

Wang, M. et al. Experimental study on the effect of fines content on the Frost swelling charac-teristics of coarse-grained soil in Canal base under open system. Journal Offshore Mech. Arct. Engineering. 146 (2), 022101. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4062931 (2024).

Ling, X. Z., Zhang, F., Li, Q. L., An, L. S. & Wang, J. H. Dynamic shear modulus and damping ratio of frozen compacted sand subjected to freeze–thaw cycle under multi-stage Cyclic loading. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 76, 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2015.02.007 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Laboratory observation and analysis of Frost heave progression in clay from the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Appl. Therm. Eng. 131, 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.11.052 (2018).

Bilodeau, J. P., Dore, G. & Pierre, P. Gradation influence on Frost susceptibility of base granular materials. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 9 (6), 397–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/10298430802279819 (2008).

Gao, J., Lai, Y., Zhang, M. & Feng, Z. Experimental study on the water-heat-vapor behavior in a freezing coarse-grained soil. Appl. Therm. Eng. 128, 956–965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.09.080 (2018).

Liu, Y., Liu, Z., Oh, E. & Ong, D. E. L. Strength and microstructural assessment of reconstituted and stabilised soft soils with varying silt contents. Geosciences 11 (8), 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences11080302 (2021).

Wang, T., Yue, Z., Ma, C. & Wu, Z. An experimental study on the Frost heave properties of coarse grained soils. Transp. Geotechnics. 1 (3), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2014.06.007 (2014).

Lai, Y., Wu, D. & Zhang, M. Crystallization deformation of Asaline soil during freezing and thawing processes. Appl. Therm. Eng. 120, 467–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.04.011 (2017).

Hu, G. et al. Water and heat coupling processes and its simulation in frozen soils: current status and future research directions. Catena 222, 106844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2022.106844 (2023).

Harlan, R. L. Analysis of coupled heat-fluid transport in partially frozen soil. Water Resour. Res. 9 (5), 1314–1323. https://doi.org/10.1029/WR009i005p01314 (1973).

Li, H., Liu, Z. & Liang, C. Mathematical model for coupled moisture, heat and stress field and numerical simulation of frozen soil. Chin. J. Theoretical Appl. Mech. 33 (5), 621–628. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:0459-1879.2001.05.005 (2001).

Sun, L. et al. A coupled cryogenic thermo-hydro-mechanical model for frozen medium: theory and implementation in FDEM. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 16 (11), 4335–4353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2023.09.007 (2023).

Qin, Z., Lai, Y., Tian, Y. & Yu, F. Frost-heaving mechanical model for concrete face slabs of earthen dams in cold regions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 161, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2019.03.009 (2019).

Gao, J. et al. A novel assembled channel lining for reducing Frost heave in seasonally frozen regions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 213, 103931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2023.103931 (2023).

Research Institute of Highway Ministry of Transport JTG 3430 – 2020. In Test Methods of Soils for Highway Engineering (China Communications, 2020).

CCCC Second Highway Consultants Co. Ltd, JTG D30- Specifications for Design of Highway Subgrades. (China Com-munications Press, Beijing, 2015). (2015).

CCCC Third Highway Engineering Bureau Co & 3610 – 2019, L. T. D. J. T. G. T. Technical Specifications for Construction of Highway Subgrades (China Communications, 2019).

Wu, J. & Han, T. Numerical research on the coupled process of the Moisture-heat-stress fields in saturated soil during freezing. Eng. Mech. 26 (04), 246–251. https://doi.org/CNKI:SUN:GCLX.0.2009-04-042 (2009).

Bai, Q., Li, X., Tian, Y. & Fang, J. Equations and numerical simulation for coupled water and heat transfer in frozen soil. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 37(zk2), 131–136. https://doi.org/10.11779/CJGE2015S2026 (2015).

Xu, X., Wang, J. & Zhang, L. Frozen Soil Physics (China Science Publishing & Media Ltd. (CSPM), 2001).

Yang, S. & Tao, W. Heat Transfer (Higher Education Press, 2006).

Zhang, H., Zhang, J., Zhang, K. & Zheng, B. Long-term plate load tests in permafrost region on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 143, 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2017.08.015 (2017).

Pan, Y. et al. Simulating the role of gravel in freeze–thaw process on the Qinghai–Tibet plateau. Theoret. Appl. Climatol. 127, 1011–1022. https://doi.org/1007/s00704-015-1684-7 (2017).

Funding

This research was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 310821173701), the Science and Technology Project of the Department of Transport of Shaanxi Province (Grant No. 22–24 K), the Science and Technology Plan Project of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction in Shaanxi Province(Grant No.2022-K53), and Shandong Qinbin Expressway Construction Co., LTD. Technology research and development project (QB-2023-SG-03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Funding acquisition H.L.: Visualization, Investigation N.N: Investigation, Methodology, Writing- Original draft preparation J.L.: Supervision W.S.: Investigation, Methodology, J.W.: Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the manuscript and have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Consent to participate

All authors agree to participate in the published version of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, Y., Li, H., Nan, N. et al. Experimental and numerical study on the Frost-Heaving characteristics of subgrade soil in the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Sci Rep 15, 44974 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28778-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28778-w