Abstract

In Bangladesh, residents of multiunit housing (MUH) face a high risk of exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS). Although smoke-free policies are widely recognised as an effective intervention to protect MUH residents, they have received limited attention from policymakers in the country. This study aimed to determine stakeholders’ preferences for smoke-free policies and to explore their perspectives on the motivators and barriers to implementing the most preferred smoke-free policy- a common area policy—in MUH complexes in urban Bangladesh. A qualitative descriptive study was conducted among 50 participants, purposively selected from three diverse groups: housing management committees (HMCs), tobacco control civil society organisations (CSOs), and the Bangladesh Fire Service & Civil Defence (FSCD) across seven divisional cities in Bangladesh. Data were collected through key informant interviews (KIIs) and analysed using an inductive thematic analysis approach. The majority of participants were aged 40 to 59 years, held at least a bachelor’s degree, were job holders, had lived in MUH for 10 to 19 years, and were identified as non-smokers. All participants reported that no smoke-free policy currently existed in the multiunit housing where they resided. The majority expressed a preference for a smoke-free common area policy in housing complexes. The findings revealed four main motivators for introducing such a policy in MUH: protection of health, reduced maintenance costs, conflict mitigation, and a lower risk of fire accidents. Conversely, several barriers were identified, including smokers’ reluctance, limited understanding of the policy, difficulties in monitoring compliance, tenancy vacancies, and implementation costs. To ensure effective development and implementation of smoke-free common area policies, policymakers and housing authorities should consider both the perceived motivators and barriers. Further research involving a boarder range of stakeholders is recommended to gain a better understanding of the dynamics influencing successful policy implementation in MUH complexes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure is a serious public health problem. There is no safe level of SHS exposure1. A growing body of epidemiological research has studied the adverse health effects of SHS exposure and recognised it as a significant risk factor for disease, disability, and death2,3. Every year, tobacco kills more than 8 million people worldwide, of whom approximately 1.2 million die from SHS exposure4. The total economic cost of SHS exposure in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries was estimated at about purchasing power parity (PPP) $7.1 billion5. Currently, Bangladesh is home to 19.2 million adult (aged 15 years and older) smokers, constituting an overall smoking prevalence rate of 18%6. A 2020 study by Faruque et al. estimated that SHS exposure causes nearly 25,000 premature deaths annually in Bangladesh, with productivity losses amounting to around $463 million7.

Multiunit housing (MUH) constitutes a major source of SHS, as tobacco smoke can move from one place to another through air ducts, wall and floor cracks, stairwells, hallways, elevator shafts, electrical wiring routes, and ventilation systems8,9. MUH residents are at greater risk of SHS exposure compared with those living in detached houses10. Previous research in the USA showed that 28.3% to 48.0% of people living in multiunit housing that did not have any smoke-free policy experienced SHS exposure11,12. In Thailand, 46.8% of middle school students reported being exposed to tobacco smoke in residential settings13. Similarly, a recent study in Bangladesh revealed that 54.9% of urban MUH residents were exposed to SHS within housing complexes14. Evidence suggests that imposing smoking restrictions in housing complexes can significantly reduce the risk of involuntary SHS exposure among residents15.

Over the past few decades, many countries have adopted tobacco control regulations in public places and on public transport. These legislative smoking bans have resulted in significant reductions in smoking and SHS exposure in workplaces, educational institutions, healthcare facilities, and restaurants16,17. Following the spirit of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), the Government of Bangladesh passed the Smoking and Tobacco Products Usage (Control) Act in 2005 and amended it in 201318. Although this law protects non-smoking people from involuntary exposure to SHS through smoking bans in public places and on public transport, it does not have any provision to restrict smoking in private settings like multiunit housing. Bangladesh has a national housing policy to ensure accessible, sustainable, and quality housing for all citizens19, but it lacks provisions restricting smoking within housing complexes. Existing evidence indicates that some developed countries, including the United States, Canada, and Australia, have recently enacted legislative measures prohibiting smoking in and around MUH complexes20,21,22. In a similar way, Bangladesh could adopt specific regulations to protect residents from SHS exposure in MUH settings.

Globally, three types of smoke-free policies are commonly implemented in multiunit housing: common area policies, building-wide policies, and unit-specific policies23. Implementing such policies in residential settings can be complex, as it involves multiple stakeholders13. This study included participants from three stakeholder groups: housing management committees (HMCs), tobacco control civil society organisations (CSOs), and the Bangladesh Fire Service & Civil Defence (FSCD). Available literature shows that various enablers and barriers influence the enforcement of smoke-free policies in multiunit housing24,25. The authors hypothesised that the introduction of a smoke-free policy in residential settings in Bangladesh would trigger both motivators and barriers to its implementation. Therefore, this study aimed to determine stakeholders’ preferences for smoke-free policies and to explore their perspectives on the factors that could support or hinder the implementation of the most preferred smoke-free policy, a common area policy, in MUH complexes in Urban Bangladesh.

Methods

Study design, population, and setting

A qualitative descriptive study was conducted among HMC members, CSO representatives, and FSCD personnel. Qualitative descriptive designs offer a rich and straightforward description of an experience or event26. Key informant interviews (KIIs) were employed as a primary data collection method for this study. KIIs are a qualitative method in which researchers conduct in-depth conversations with individuals considered experts on a specific topic to obtain rich insights and valuable recommendations based on their knowledge and experience in the field27. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist (Appendix 3) was used to guide reporting, ensuring rigour and transparency across all stages of the study28.

In urban Bangladesh, many multiunit housing complexes are managed by voluntary HMCs consisting of flat owners serving as president, general secretary, treasurer, and ordinary members. These committees are elected for three-to five-year terms to ensure residents’ access to residential rights, including a healthy living environment, and to promote compliance with complex regulations. HMCs also mediate conflicts between residents over common practices, such as smoking in shared areas. As the local authority responsible for implementing smoke-free policies in MUH complexes, they have adequate knowledge of flat owners’ implementation capacity and residents’ expectations. Consequently, their perspectives are critical for identifying potential barriers and motivators for policy implementation. Certain local CSOs play a significant role in national tobacco control. Their activities include public education on the dangerous effects of smoking and SHS exposure, advocacy for enforcement of tobacco control regulations in public places and on public transport, promotion of alternative livelihoods to tobacco cultivation, and monitoring of tobacco industry practices. The inclusion of CSO representatives in this study was crucial, as their practical experience in implementing smoke-free policies in public places and on public transport and their understanding of political dynamics could facilitate a deeper exploration of potential barriers and motivators for policy acceptance and enforcement in multiunit housing. The FSCD, a government organisation with about 500 fire stations across the country29, is primarily responsible for extinguishing fires in residential, commercial, and other establishments, protecting lives and property from fires in affected areas, and implementing preventive measures to minimise fire risks. Notably, burning cigarette butts are the second most common cause of fire accidents in Bangladesh30. Fire service personnel were included in this study because their firsthand experience with smoking-related fires in residential settings and insights into residents’ smoking behaviour could provide a better understanding to inform effective policy design and implementation.

Participants were selected according to the following criteria: (a) HMC members, CSO representatives, and fire service personnel with at least 5 years of residence in multiunit housing, (b) current HMC members who had completed at least one full term on a previous committee, (c) CSO representatives involved in advocating for the enforcement of the tobacco control law in public places, (d) fire service personnel who had conducted a minimum of 20 residential fire rescue operations. Individuals unable to participate due to illness at the time of data collection were excluded. Bangladesh is currently divided into eight administrative divisions: Dhaka, Chattogram, Sylhet, Khulna, Barishal, Rajshahi, Rangpur, and Mymensingh. This study was planned to be conducted across all these divisional cities, however, due to budgetary constraints, Mymensingh city was excluded from the study.

Sampling and participant recruitment

A purposive sampling strategy was employed to recruit participants from each stakeholder group for this study31. Field enumerators prepared a list of at least 40 MUH complexes in each selected city using a snowball sampling technique32. Each housing complex had an active housing management committee (HMC), and the list included the names, designations, and contact details of HMC members. The purpose of this study, along with its inclusion and exclusion criteria, was explained individually to each HMC member via mobile phone. Only those who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate were recruited for interviews. To recruit CSO representatives, 10 tobacco control CSOs were first identified through snowball sampling with support from anti-tobacco professional networks. Following consultations with the executive directors of these CSOs through email and mobile phone, eligible representatives were selected. Similarly, seven fire stations, one per selected city, were chosen using convenience sampling33, and then fire service professionals were selected based on the inclusion criteria of the study. Although five HMC members and two fire service professionals refused to participate in the interviews, all CSO representatives who were approached agreed to take part. Interview appointments were fixed at the time of participant recruitment.

Although the initial plan was to recruit four HMC members, one CSO representative, and one fire service professional from each of the seven cities, data collection continued until data saturation was reached34. This indicates that interviews proceeded as long as new themes or information emerged. A total of 50 participants were finally interviewed: 30 HMC members, 10 CSO representatives, and 10 fire service professionals (Fig. 1). Participant distribution across cities was as follows: six HMC members from Dhaka city, and four HMC members from each of the other six cities; two CSO representatives from Dhaka, Khulna, and Rajshahi, and one from each of the remaining four cities; two fire service professionals from Dhaka, Chattogram, and Sylhet cities, and one from each of the other five cities.

Data collection

Four experienced qualitative interviewers, each holding a master’s degree in social sciences, were recruited for data collection. Before fieldwork, MGK, the principal investigator, provided them with two days of training on the interview guide, data collection procedures, and ethical issues. A semi-structured interview guide (Appendix 1) was developed to facilitate key informant interviews. The guide, originally prepared in English, was translated into Bengali and pretested among five participants, including at least one from each stakeholder group to verify its clarity, cultural appropriateness, and comprehensiveness. Interviews were conducted in person on scheduled dates. Before each interview, participants were briefed on the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of their participation, and the anonymity of their data. Subsequently, written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Interview sessions were audio-recorded upon participants’ permission, and field notes were taken as necessary. Interviews with CSO representatives and fire service personnel were held at their offices during office hours. On the other hand, HMC members were interviewed within housing complexes – either at their homes or in security guard rooms mainly in the evening. All interviews were conducted in a private and quiet environment, with only the interviewer and a single participant, to encourage open and candid discussion. Each interview lasted approximately 50 minutes, and data collection took place from 25 July to 16 September 2019. During data collection, the principal investigator visited the study sites and silently observed at least two interviews conducted by each interviewer and provided guidance on any areas identified for improvement to enhance the quality of data. No repeat interviews were conducted, and transcripts were not returned to participants for review or correction. Furthermore, participants had no pre-existing relationship with the interviewers.

Data management and analysis

All audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim by two master’s-level students. Field notes were consolidated to create a final set of interview data for each participant. The transcripts were randomly cross-checked by the first author against about 20% of the original audio recordings for accuracy. Due to budgetary and time constraints, the transcripts were not translated into English. Inductive thematic analysis was performed following a four-step process– immersion in the data, coding, creation of categories, and identification of key themes35. The analysis was conducted manually by MGK and TI. In the first step, these two authors familiarised themselves with the data by reading and re-reading the interview transcripts and field notes. In the second step, they identified key phrases and sentences within the data that were relevant to a specific context and generated codes for these chunks of data using an iterative process36. Any discrepancies in coding were resolved through discussions. A codebook (Appendix 2) was developed to facilitate the systematic coding of interview data. In the third step, categories were formed by grouping similar codes together. In the fourth step, recurring patterns and meaningful groupings within the categorised data were identified. These categories were then organised into boarder, more abstract themes by considering relationships, connections, and shared meanings. A final meeting was held between the authors to discuss and agree on the themes and sub-themes. However, the results of this study have been presented according to themes and sub-themes, supported by relevant participant quotes.

Results

Participant characteristics

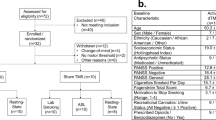

Table 1 describes the basic characteristics of 50 study participants. The majority (68.0%) of participants were housing management committee (HMC) members. Males made up an overwhelming majority of participants (96.0%). The majority of participants were in the 40 to 59 age group (54.0%), had completed a bachelor’s degree or higher education (76.0%), were job holders (62.0%), had lived in multiunit housing (MUH) for 10 to 19 years (52.0%), and were non-smokers (74.0%).

Themes

The analysis revealed three major themes– (1) support for smoke-free policies, (2) perceived motivators for policy implementation, and (3) perceived barriers to policy implementation.

Support for smoke-free policies.

a. Levels of support for smoke-free policies.

Participants were asked whether any policies restricted smoking in the multiunit housing buildings where they currently lived. Although a small number of participants (n = 9) reported noticing ‘No Smoking’ signs in certain areas, such as entrances, waiting spaces, and parking areas, all confirmed that no formal smoke-free policy existed in their residential buildings. When asked why such policies had not been adopted, participants cited several major reasons, including lack of awareness of smoke-free policies, resistance from residents, the need to recruit additional housing staff, and inadequate enforcement mechanisms. One participant said:

Smokers may claim that their home is a private place. They have the right to smoke there. Nobody can interfere with smoking in private places. (KII 6: Housing management committee)

Furthermore, participants were asked if they would support smoke-free policies in multiunit housing, regardless of the policy type. In response, all participants showed a strong interest in smoke-free policies in housing complexes. One participant stated:

Definitely, a smoke-free policy will appear as a blessing for non-smokers. Because its implementation will make (housing) complexes smoke-free. (KII 9: Housing management committee)

However, the most common motivations for smoke-free housing voiced by participants were the protection of residents from the health risks of SHS exposure and the opportunity for smokers to quit smoking.

b. Policy type.

Participants were asked which type of smoke-free policy they would prefer for multiunit housing. The majority of participants (n = 31) favoured a smoke-free common area policy. One participant stated:

Suppose, none of your family members are smokers. Are you safe at home? Of course not. You may still be exposed to (cigarette) smoke in waiting spaces, parking areas, entrances, staircases, or on roofs. (KII 15: CSO representative)

Participants reported that common areas are the largest source of secondhand smoke in MUH complexes in Bangladesh. They indicated that implementing a common area policy would restrict smoking in these areas, thereby significantly reducing exposure to SHS in housing complexes.

More than one-quarter of participants (n = 13) favoured a smoke-free building-wide policy that restricts smoking within flats, in common areas, and in outdoor areas adjacent to the residential building. One participant said:

A smoke-free building-wide policy is the only way to fully protect residents from secondhand smoke. It gives them the opportunity to live in a smoke-free environment. (KII 7: CSO representative)

This group of participants described the smoke-free building-wide policy as a comprehensive measure and indicated that it alone has the potential to fully protect residents from SHS exposure. They further asserted that residents would not benefit from smoke-free housing unless this specific policy were implemented.

Furthermore, a small number of participants (n = 6) supported a smoke-free home policy for multiunit housing complexes. They indicated that family members, including children, are exposed to SHS in homes where people smoke. They argued that smokers would comply with home smoking restrictions because they would prioritise the health of their family members. One participant uttered:

It will be relatively easy to implement a home (unit-specific) policy. People are careful about their family members’ health, so they will be motivated to stop smoking at home. (KII 6: Housing management committee)

This study has highlighted participants’ perspectives on the perceived motivators and barriers to implementing a smoke-free common area policy in multiunit housing.

Perceived motivators for policy implementation.

a. Protection of health.

The majority of participants (n = 32) considered that implementing a smoke-free common area policy would protect residents’ health by reducing their exposure to SHS in multiunit housing. One participant stated:

Health is a top priority for non-smokers. They always want to keep themselves and their other family members away from secondhand smoke. …living in a building with a smoke-free policy will fulfill that desire. (KII 3: CSO representative)

While discussing the potential effects of policy implementation in multiunit housing, participants explained that exposure to secondhand smoke is a risk factor for many diseases. They argued that the implementation of a common area policy would eliminate exposure in common areas, thereby reducing the incidence of such diseases among non-smoking residents.

b. Reduced maintenance costs.

Over one-third of participants (n = 17) anticipated that implementing a smoke-free common area policy in multiunit housing would result in a significant reduction in cleaning costs. With less smoke residue in common spaces, buildings with such a policy would require less labour and fewer cleaning products. One participant said:

After the implementation of a common area policy, there will be no cigarette ashes, butts, packets, or burnt matchsticks in common areas. That’s why, flat owners will not need to spend extra money on cleaning. (KII 18: Housing management committee member)

Eight participants expressed the view that the implementation of a smoke-free common area policy would decrease building renovation costs. One participant stated:

Tobacco smoke damages the colour of walls and ceilings. Flat owners have to renovate those tainted walls and ceilings…. Only the implementation of a smoke-free policy can cut down such painting costs. (KII 13: Housing management committee member)

c. Conflict mitigation.

More than one quarter of participants (n = 13) viewed that implementing a smoke-free common area policy could reduce the occurrence of conflicts between residents over smoking in the common areas of multiunit housing. They explained that, due to the harmful effects of SHS exposure and the unpleasant smell of cigarette smoke, non-smoking residents might protest when they saw other residents smoking nearby in common areas. Such protests sometimes could lead to conflicts between residents. One participant expressed:

Quarrels over smoking in common areas are quite common. Sometimes such incidents become so serious that we (housing management committee) have to take steps to resolve them. I believe there will be no more quarrels after this policy comes into effect. (KII 17: Housing management committee member)

d. Lower risk of fire accidents.

More than one-fifth of participants (n = 11) were optimistic that the implementation of a smoke-free common area policy would reduce the risk of smoking-related fires in residential settings. They reasoned that, once such a policy is in place, people would no longer be allowed to smoke in common areas. Consequently, there would be no discarded burning cigarette butts in these areas, thereby contributing to the prevention of residential fires. One participant said:

…they (residents) often smoke cigarettes in common areas and throw burning butts and matchsticks indiscriminately. Sometimes these cause fires. If a common area policy is implemented, fire accidents in multiunit housing will be significantly decreased. (KII 22: Fire service professional)

Four participants stated that is the presence of fire detection systems in smoke-free housing complexes could decrease the incidence of residential fires. One participant opined:

Those who live in buildings that have a smoke-free policy are at lower risk of fire. When smoke originates from anywhere in those buildings, smoke detectors alert people to potential accidents through a fire alarm. (KII 42: Fire service professional)

Perceived barriers to policy implementation.

a. Smokers’ reluctance.

More than half of the participants (n = 27) expressed concern that smokers’ reluctance to stop smoking in common spaces would pose a major barrier to implementing a smoke-free common area policy in multiunit housing. They stated that many smokers- both flat owners and tenants- prefer to smoke in the common spaces of housing complexes. There was a fear that some of them would continue smoking in these spaces even after the common area policy had been implemented in multiunit housing. One participant said:

When a housing complex adopts a common area policy, residents can’t smoke in the common areas. But some people will still smoke there, and they will behave as if nothing has changed! (KII 24: Housing management committee)

A good number of participants (n = 15) suggested that housing authorities should introduce smoking cessation counselling in housing complexes to help residents quit smoking more quickly. They explained that once smokers become non-smokers, they would be more likely to comply with the smoke-free policy in multiunit housing. One participant shared:

Smoking is a habit that people develop over many years. Even if they (smokers) want to quit, they can’t do it overnight. The best thing flat owners can do is to offer counselling to help smokers quit. (KII 2: CSO representative)

b. Limited understanding of the policy.

More than one-third of participants (n = 19) stated that a lack of knowledge and understanding of a smoke-free policy among flat owners, tenants, housing managers, and security guards could significantly hinder its implementation. They explained that when these stakeholders did not have clear information about the intent, benefits, rules, and enforcement mechanisms of the policy, this would cause confusion and reduce motivation among them, potentially leading to non-compliance. One participant expressed:

A policy is a set of actions. If people don’t know about these actions and their roles in implementing the policy, they can’t contribute properly to its implementation. (KII 42: CSO representative)

c. Difficulties in monitoring compliance.

Over one-third of participants (n = 17) viewed that monitoring smoking incidents in the common areas of multiunit housing, such as roofs, doorways, and staircases would be difficult. They explained that the number of security guards in a housing complex is often too small to consistently monitor whether residents are smoking in these spaces. One participant stated:

If someone smokes on the roofs or staircases, how can they (guards) detect it? (KII 20: Housing management committee member)

Three participants highlighted the challenges of identifying strangers who smoke in areas, such as entrances and windows and subsequently leave the building premises. They explained that the departure of these individuals complicates the enforcement of smoke-free policies and reduces the likelihood of consistent compliance. One participant said:

Suppose, a guard sees an outsider smoking near the main entrance and asks him to stop. If he (smoker) doesn’t pay attention to the guard’s words, there is nothing we can do to enforce the rule. (KII 8: CSO representative)

Some participants (n = 9) recommended recruiting and training additional security guards and surveillance staff to strengthen the monitoring of smoking incidents within MUH complexes. In addition, several participants (n = 5) suggested that housing authorities should install closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras in various common areas to enable constant monitoring of smoking incidents. One participant stated:

It wouldn’t be wise to depend solely on security guards to monitor smoking in a (housing) complex. What would you do if a smoker denied the guard’s complaint? I’m sure you would have trouble proving them wrong. But if you install a CCTV camera in the complex, they can’t cheat you. (KII 15: CSO representative)

d. Tenant vacancy.

Over one-quarter of participants (n = 14) anticipated that the implementation of a smoke-free common area policy would increase tenant vacancies. They explained that residents would no longer be permitted to smoke in the common areas of a residential building where such a policy was in place. This restriction could lead those unwilling to stop smoking in common areas to seek alternative housing. One participant shared:

There are many tenants who smoke in the common areas but not in their homes. Many of them might leave those housing complexes where a smoke-free common area policy is executed. (KII 48: Ordinary Member, Housing Management Committee)

e. Implementation costs.

More than one-fifth of participants (n = 11) viewed that implementing a smoke-free common area policy in MUH complexes countrywide would involve huge implementation costs related to manpower, logistics, and mass awareness campaigns. Such costs could discourage the government from pursuing its implementation. One participant stated:

There are thousands of multiunit housing complexes in the country. The government would have to recruit and train a large workforce to implement the policy. How would the government bear these costs? (KII 45: CSO representative)

Seven participants anticipated that flat owners would need to spend a large amount of money to implement a smoke-free policy in MUH complexes, as this would require hiring additional staff and installing surveillance devices like CCTV cameras. One participant stated:

Flat owners may need to hire extra staff to track and document smoking incidents in (housing) complexes. That would be a great burden for them. (KII 5: Housing management committee member)

Four participants felt that the government should provide flat owners with seed money to introduce a smoke-free policy in multiunit housing buildings. They added that this seed money could cover the costs of basic activities, such as developing smoke-free signage and posters, installing CCTV cameras, and training staff.

Discussion

All participants in the present study were in favour of smoke-free policies for multiunit housing. Another previous study conducted in Bangladesh reported that 94.8% of MUH residents supported smoke-free housing policies for multiunit housing, which is consistent with this finding23. One possible explanation for the high level of support for smoke-free policies in the present study is the relatively low prevalence of smoking among participants. Additionally, participants’ greater awareness about the health risks of SHS exposure may have motivated them to advocate for smoke-free environments in residential settings.

Another important finding of this study was that the majority of participants preferred a smoke-free common area policy for multiunit housing over other options, such as a smoke-free building-wide policy or a smoke-free unit-specific policy. Although this finding is contradicted by a Bangladeshi quantitative study, in which most participants supported a smoke-free building-wide policy for multiunit housing23, it is supported by several previous studies conducted in the United States37,38,39. This higher level of support for a common area policy may be explained by the fact that implementing this policy would prohibit smoking in common areas, which are the largest source of SHS exposure in multiunit housing. Furthermore, implementing a common area policy may be more straightforward than a unit-specific or building-wide policy, as housing authorities usually oversee the maintenance and management of these shared areas. On the other hand, implementing a smoke-free unit-specific or building-wide policy can be more challenging because some people consider prohibiting smoking in private homes an infringement of personal autonomy40,41. Given their higher acceptability and feasibility, smoke-free common area policies should be prioritised by both housing authorities and policymakers to reduce SHS exposure in multiunit housing.

In the present study, the potential of a smoke-free common area policy to protect the health of residents, especially non-smokers from the harmful effects of SHS exposure was perceived as a significant motivator for its implementation in multiunit housing. A recent US longitudinal cohort study showed that participants living in areas with smoke-free policies in restaurants, bars, or workplaces had a lower risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and congestive heart failure compared to those in areas without such policies42. A systematic review and meta-analysis reported that hospitalisations for acute coronary events decreased by 14% in locations that implemented comprehensive legislations compared with an 8% reduction in hospitalisations in locations with only partial restrictions43. These findings indicate that smoke-free policies in housing complexes can improve health outcomes and reduce healthcare costs. From a policy perspective, it is therefore crucial that the health benefits of smoke-free policies are clearly communicated during the design and implementation stages.

According to participants in the present study, buildings with a smoke-free common area policy would incur lower cleaning and renovation costs compared with those without such policies. These potential cost savings were perceived as a key incentive for policy adoption in multiunit housing. This finding aligns with previous research conducted in the United States, which demonstrated substantial cost savings associated with smoking regulations in multiunit housing44,45. However, a common misconception persists that the implementation of smoke-free policies increases building maintenance costs. At the same time, a lack of information on smoking-related costs at the property level may discourage owners from adopting smoke-free policies in residential buildings46. To address this gap, further research can be conducted to compare smoking-related property costs in MUH complexes with and without smoke-free policies. Disseminating this information through research reports, policy briefs, and stakeholder engagement forums could facilitate informed decision-making and promote the wider adoption of smoke-free housing initiatives.

The present study revealed that implementing a smoke-free common area policy could mitigate conflicts between smoking and non-smoking residents over smoking in the common areas of housing complexes. This finding is supported by the results of other previous studies on smoke-free housing policies47,48. As explored in the present study, such conflicts often arise from concerns about the negative health consequences of SHS exposure and the unpleasant smell of tobacco smoke. These conflicts can damage personal relationships and, in extreme cases, lead to tenant evictions. Smoking cessation counselling can facilitate successful quitting49, thereby reducing SHS exposure and the likelihood of smoking-related conflicts. Therefore, housing authorities should offer cessation counselling within residential complexes and consider establishing designated smoking areas (DSAs) located at least 25 feet from building entries, operable windows, and ventilation intakes50.

In the present study, a lower risk of smoking-related fire accidents was found to be a potential motivator for implementing smoke-free common area policies in multiunit housing. Available evidence suggests that smoke-free policies, irrespective of their type, can reduce the occurrence of fire accidents in such housing settings, thereby supporting the present finding48,51. The major benefit of smoking bans in common areas could be a perceived reduction in fire risk, as the removal of ignition sources, such as burning cigarette butts and matchsticks minimises the likelihood of fire outbreaks following the implementation of common area policies. Moreover, as reported by participants in this study, the installation of fire detection systems in smoke-free buildings may further contribute to the reduced risk of fire accidents. These findings underscore the necessity of integrating smoke-free policies into broader housing safety frameworks. Policymakers and housing authorities should consider incorporating mandatory smoke-free provisions into the design and management of MUH developments, alongside ensuring routine inspection, maintenance, and functionality testing of fire detection systems. Public awareness campaigns emphasising the dual benefits of smoke-free housing—enhanced health outcomes and improved fire safety—may also promote greater acceptance and compliance among residents.

The present study identified that smoking residents’ reluctance to refrain from smoking in the common areas of residential buildings with common area policies may hinder the effective implementation of such policies. This observation is similar to the results of other previous studies that investigated barriers to the implementation of smoke-free policies52,53. One major reason for such reluctance could be residents’ limited awareness about the harmful effects of secondhand smoke. This reluctance could also be explained by the fact that some residents do not want to give up the personal comfort and habitual practices to which they have long been accustomed. Housing authorities can help reduce smokers’ reluctance by raising awareness about the negative effects of smoking and SHS exposure through extensive awareness campaigns and workshops. Furthermore, as suggested by participants in the present study, the provision of smoking cessation counselling and related support services for smoking residents could facilitate greater compliance and more effective implementation of smoke-free policies in multiunit housing. This recommendation is supported by an earlier study, demonstrating a positive association between the availability of cessation services and the successful implementation of smoke-free policies in clinical settings54.

In this study, a lack of knowledge and understanding among residents and housing staff regarding the contents and enforcement procedures of a smoke-free common area policy was identified as a perceived challenge to its implementation. This finding is supported by the results of other previous studies that investigated barriers to policy implementation55,56. The success of a policy depends not only on its design and intent but also on the effectiveness of its implementation process. Stakeholders’ comprehensive understanding of a policy plays an important role in its successful implementation. Balane et al. similarly reported that when stakeholders have low levels of knowledge about a policy, they show low levels of interest in its implementation57.To address this challenge, residents, housing staff, and other relevant stakeholders should be thoroughly educated about the smoke-free common area policy prior to its implementation in MUH complexes. Structured training programmes and mass awareness campaigns can be conducted to familiarise them with the contents, rules, responsibilities, implementation procedures, and associated benefits of the policy. Such initiatives would not only enhance compliance but also foster shared ownership, accountability, and sustainability in the implementation of smoke-free policies in residential settings.

The present study identified difficulties in monitoring smoking incidents in common areas as a potential barrier to implementing a smoke-free common area policy in multiunit housing. Participants attributed these difficulties primarily to a shortage of security personnel in multiunit housing, which is in line with an earlier study58. Another factor contributing to these challenges, as identified in the present study, was the difficulty of identifying individuals who smoke in common areas, particularly when they are outsiders. This anonymity may limit the ability of housing authorities to enforce smoke-free regulations effectively as offenders cannot be warned or penalised. Additionally, the size of housing complexes was also considered to exacerbate monitoring difficulties. A study conducted in the United States reported that monitoring smoking incidents was challenging in large buildings or those lacking shared interior hallways59. To enhance the monitoring of smoking incidents in multiunit housing, participants in the present study recommended: (a) recruiting an adequate number of security guards and surveillance personnel, (b) providing them with appropriate training on monitoring procedures, and (c) installing CCTV cameras in common areas. Furthermore, the use of real-time airborne nicotine detectors equipped with Wi-Fi connectivity could assist surveillance personnel in more consistently identifying policy violations in multiunit housing60.

Another key finding of the present study was that implementing a smoke-free common area policy would lead to higher rental vacancy rates in multiunit housing. This finding remains consistent with those of earlier studies carried out in different US states44,61,62. One possible explanation for these higher vacancy rates is that some smokers are highly nicotine-dependent and are unable to quit63, prompting them to relocate to residential buildings where smoking is permitted. To attract potential tenants to smoke-free housing, housing authorities should promote the positive aspects of a smoke-free environment. On the other hand, some studies suggest that adopting smoke-free policies does not affect vacancy rates in MUH complexes45,61. Therefore, further research is warranted to examine the relationship between tenant vacancies and the implementation of smoke-free policies in multiunit housing.

In the present study, a lack of government funding was identified as a potential barrier to implementing a smoke-free policy in MUH complexes. This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies conducted in Kenya and Thailand, which explored the facilitators and barriers to policy imlementation56,64. Financial resources are essential for implementing any policy, as they are required to support activities such as staffing, programme development, infrastructure improvements, and other operational expenses. Therefore, it is recommended that the Government of Bangladesh allocate adequate financial resources to ensure the effective implementation of smoke-free policies in multiunit housing across the country. Another important from this study was that implementing a smoke-free common area policy would increase the financial burden of flat owners due to the need to recruit additional staff and install surveillance devices, such as CCTV cameras, to monitor and track smoking incidents in the common areas of MUH complexes. This is consistent with the results of an earlier study conducted among apartment owners, renters, and managers in the USA44. These findings indicate that financial constraints may discourage many flat owners from adopting a smoke-free policy in residential buildings. Recognising this challenge, participants in the present study recommended that the government provide seed money to flat owners to cover the basic costs associated with implementing smoke-free policies, including the training of security personnel and the installation of CCTV cameras and fire detectors in housing complexes.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of the present study is the inclusion of diverse participant groups, which allowed for the exploration of a wide range of perspectives on the motivators and barriers to implementing a smoke-free policy in MUH settings. Another strength is that data were collected by social science graduates with substantial experience in qualitative data collection, which likely enhanced the accuracy and reliability of the results. Despite these strengths certain limitations must be noted. First, this study did not include officials from tobacco control law enforcement agencies, tenants, or housing staff such as property managers and security guards. Enforcement agencies in Bangladesh have practical experience in implementing the tobacco control law in public places and on public transport, while tenants and housing staff have unique insights into smoking practices within MUH complexes. Including these groups may have provided a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges and incentives related to policy implementation. Future research should therefore consider incorporating a boarder range of participants. Second, due to financial constraints, data collection was restricted to divisional cities. Expanding data collection to district-level contexts could reveal whether the dynamics of policy implementation differ across administrative levels. Finally, the use of face-to-face interviews may have introduced social desirability bias65, potentially influencing participants’ responses. Efforts should be made in future studies to mitigate this bias by ensuring anonymity and encouraging open, honest communication during data collection.

Conclusions

This study revealed several perceived motivators for implementing a smoke-free policy in the common areas of multiunit housing, including protection of health, reduced maintenance costs, conflict mitigation, and a lower risk of fire accidents. It also highlighted potential barriers, such as smokers’ reluctance, limited understanding of the policy, difficulties in monitoring compliance, tenant vacancy, and implementation costs. Policymakers and housing authorities should capitalise on these motivators and address the barriers to facilitate the effective implementation of smoke-free policies in MUH. Tailored awareness campaigns and financial support mechanisms may further facilitate policy adoption and compliance. Further research should involve additional stakeholders, including residents, security personnel, tobacco control law enforcement agencies, and healthcare professionals to gain a better understanding of the factors influencing the successful implementation of a smoke-free common area policy in MUH complexes.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure To Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General (US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2006).

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US). Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), 2014).

Zhai, C. et al. Global, regional, and National deaths, disability-adjusted life years, years lived with disability, and years of life lost for the global disease burden attributable to second-hand smoke, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. Sci. Total Environ. 862, 160677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160677 (2023).

Fact sheet: Tobacco [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization. May 24. (2022). Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco

Koronaiou, K. et al. Economic cost of smoking and secondhand smoke exposure in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Tob. Control. 30 (6), 680–686. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055715 (2021).

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics and National Tobacco Control Cell. Global Adult Tobacco Survey Bangladesh 2017 (BBS and NTCC, 2019).

Faruque, G. M. et al. The economic cost of tobacco use in Bangladesh: A health cost approach [Internet]. Dhaka: Bangladesh Cancer Society; (cited 2024 Feb 22). (2020). Available from: http://bnttp.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Bangladesh-Health-Cost-Full-Report-2020.pdf

Wilson, K. M. et al. Tobacco smoke incursions in multiunit housing. Am. J. Public. Health. 104 (8), 1445–1453. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.301878 (2014).

King, B. A., Travers, M. J., Cummings, K. M., Mahoney, M. C. & Hyland, A. J. Secondhand smoke transfer in multiunit housing. Nicotine Tob. Res. 12 (11), 1133–1141. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntq162 (2010).

Wilson, K. M., Klein, J. D., Blumkin, A. K., Gottlieb, M. & Winickoff, J. P. Tobacco-smoke exposure in children who live in multiunit housing. Pediatrics 127 (1), 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-2046 (2011).

King, B. A., Travers, M. J., Cummings, K. M., Mahoney, M. C. & Hyland, A. J. Prevalence and predictors of smoke-free policy implementation and support among owners and managers of multiunit housing. Nicotine Tob. Res. 12 (2), 159–163. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntp175 (2009).

Licht, A. S., King, B. A., Travers, M. J., Rivard, C. & Hyland, A. J. Attitudes, experiences, and acceptance of smoke-free policies among US multiunit housing residents. Am. J. Public. Health. 102 (10), 1868–1871. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300717 (2012).

Phetphum, C. & Noosorn, N. Prevalence of secondhand smoke exposure at home and associated factors among middle school students in Northern Thailand. Tob. Induc. Dis. 18, 11. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/117733 (2020).

Kibria, M. G. et al. Secondhand smoke exposure and associated factors among City residents living in multiunit housing in Bangladesh. PLoS One. 18 (9), e0291746. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291746 (2023).

Pizacani, B. A., Maher, J. E., Rohde, K., Drach, L. & Stark, M. J. Implementation of a smoke-free policy in subsidized multiunit housing: effects on smoking cessation and secondhand smoke exposure. Nicotine Tob. Res. 14 (9), 1027–1034. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr334 (2012).

Callinan, J. E., Clarke, A., Doherty, K. & Kelleher, C. Legislative smoking bans for reducing secondhand smoke exposure, smoking prevalence and tobacco consumption. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005992.pub2 (2010).

Fernández, E. et al. Changes in secondhand smoke exposure after smoke-Free legislation (Spain, 2006–2011). Nicotine Tob. Res. 19 (11), 1390–1394. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntx040 (2017).

Smoking and Tobacco Products Usage (Control) Act. 2005 Mar 15 (cited 2024 Mar 07) (Bangladesh). (2005). [Internet] Available from: https://www.banglajol.info/index.php/SSR/article/view/56516/39441

National housing authority. In National housing policy 2016 (NHA, 2017).

US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Instituting smoke-free public housing: a rule by the Housing and Urban Development Department [Internet]. (cited 2023 Feb 10). (2016). Available from: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/12/05/2016-28986/instituting-smoke-freepublic-housing

Kaufman, P., Kang, J., Kennedy, R. D., Beck, P. & Ferrence, R. Impact of smoke-free housing policy lease exemptions on compliance, enforcement and smoking behavior: A qualitative study. Prev. Med. Rep. 10, 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.01.01 (2018).

Grace, C., Greenhalgh, E. M. & Tumini, V. 15.6 Smoking bans in the home and car. In: Greenhalgh EM, Scollo MM, Winstanley MH, editors. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; (cited 2023 Feb 10). (2022). Available from: http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-15-smokefree-environment/15-6- domesticenvironments.

Kibria, M. G. et al. Assessing the choice of smoke-free policies for multiunit housing and its associated determinants in bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open. 14 (4), e074928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-074928 (2024).

Passey, M. E., Longman, J. M., Robinson, J., Wiggers, J. & Jones, L. L. Smoke-free homes: what are the barriers, motivators and enablers? A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open. 6 (3), e010260. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010260 (2016).

Berg, C. J., Zheng, P. & Kegler, M. C. Perceived benefits of smoke-free homes, the process of Establishing them, and enforcement challenges in Shanghai, china: a qualitative study. BMC Public. Health. 15, 89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1428-8 (2015).

Neergaard, M. A., Olesen, F., Andersen, R. S. & Sondergaard, J. Qualitative description - the poor cousin of health research? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 9, 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-52 (2009).

Ahmed, F. et al. Palliative care in turkey: insights from experts through key informant interviews. J. Cancer Policy. 42, 100506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpo.2024.100506 (2024).

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P. & Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 19, 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 (2007).

Tuhin, A. K. Strengthening the fire service. The Financial Express [Internet]. Feb 1 [cited 2025 Oct 26]. (2025). Available from: https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/views/opinions/strengthening-the-fire-service [cited 2025 Oct 26].

Short-circuits lit cigarettes leading causes of fire in Bangladesh: Fire service. The Business Standard [Internet]. Feb 4 (cited 2024 Oct 26). (2024). Available from: https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/electrical-short-circuits-cigarettes-butts-leading-causes-fire-across-bangladesh-2023

Robinson, R. S. Purposive sampling. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and well-being Research (ed. Michalos, A. C.) 5645–5647 (Springer International Publishing, 2024).

Parker, C., Scott, S. & Geddes, A. in Snowball Sampling. (eds Atkinson, P., Delamont, S., Cernat, A., Sakshaug, J. W. & Williams, R. A.) (SAGE Research Methods Foundations, 2019).

Stratton, S. J. Population research: convenience sampling strategies. Prehosp Disaster Med. 36 (4), 373–374. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X21000649 (2021).

Guest, G., Bunce, A. & Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods. 18 (1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822x05279903 (2006).

Green, J. et al. Generating best evidence from qualitative research: the role of data analysis. Aust NZ J. Public. Health. 31 (6), 545–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2007.00141.x (2007).

Miles, M. B. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook 2nd edn. (SAGE, 1994).

Ballor, D. L., Henson, H. & MacGuire, K. Support for no-smoking policies among residents of public multiunit housing differs by smoking status. J. Community Health. 38 (6), 1074–1080. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-013-9716-7 (2013).

Hood, N. E., Ferketich, A. K., Klein, E. G., Wewers, M. E. & Pirie, P. Individual, social, and environmental factors associated with support for smoke-free housing policies among subsidized multiunit housing tenants. Nicotine Tob. Res. 15 (6), 1075–1083. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nts246 (2013).

Cook, N. J. et al. Support for smoke-free multi-unit housing policies among Racially and ethnically diverse, low-income seniors in South Florida. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 29 (4), 405–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-014-9247-4 (2014).

Ritchie, D., Amos, A., Phillips, R., Cunningham-Burley, S. & Martin, C. Action to achieve smoke-free homes: an exploration of experts’ views. BMC Public. Health. 9, 112. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-112 (2009).

Fagundes, D. & Roberts, J. L. Housing, healthism, and the HUD smoke-free policy. Northwest. Univ. Law Rev. 113 (4), 917–940 (2019).

Mayne, S. L. et al. Longitudinal associations of smoke-free policies and incident cardiovascular disease: CARDIA study. Circulation 138 (6), 557–566. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032302 (2018).

Jones, M. R., Barnoya, J., Stranges, S., Losonczy, L. & Navas-Acien, A. Cardiovascular events following smoke-free legislations: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Envir Health Rep. 1 (3), 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-014-0020-1 (2014).

Ong, M. K., Diamant, A. L., Zhou, Q., Park, H. Y. & Kaplan, R. M. Estimates of smoking-related property costs in California multiunit housing. Am. J. Public. Health. 102 (3), 490–493. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300170 (2012).

King, B. A., Peck, R. M. & Babb, S. D. Cost savings associated with prohibiting smoking in U.S. Subsidized housing. Am. J. Prev. Med. 44 (6), 631–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.024 (2013).

Hewett, M. J., Sandell, S. D., Anderson, J. & Niebuhr, M. Secondhand smoke in apartment buildings: renter and owner or manager perspectives. Nicotine Tob. Res. 9 (Suppl 1), S39–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/14622200601083442 (2007).

Ezra, D. B. Get your ashes out of my living room: controlling tobacco smoke in multi-unit residential housing. Rutgers L Rev. 54, 135 (2001).

Jackson, S. L. & Bonnie, R. J. A systematic examination of smoke-free policies in multiunit dwellings in Virginia as reported by property managers: implications for prevention. Am. J. Health Promot. 26 (1), 37–44. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.091005-QUAN-329 (2011).

Chen, J. et al. Effectiveness of individual counseling for smoking cessation in smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asymptomatic smokers. Exp. Ther. Med. 7 (3), 716–720. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2013.1463 (2014).

lunk, A. D., Rees, V. W., Jeng, A., Wray, J. A. & Grucza, R. A. Increases in secondhand smoke after going smoke-free: an assessment of the impact of a mandated smoke-free housing policy. Nicotine Tob. Res. 22 (12), 2254–2256. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntaa040 (2020).

ChangeLab Solutions. Implementing & enforcing a smokefree multi-unit housing ordinance [Internet]. Oakland (CA): ChangeLab Solutions; 2014 [cited 2025 Oct 25]. Available from: https://www.changelabsolutions.org/product/smokefree-muh-ordinance

Satterlund, T. D., Treiber, J., Kipke, R. & Cassady, D. A qualitative evaluation of 40 voluntary, smoke-free, multiunit, housing policy campaigns in California. Tob. Control. 23 (6), 491–495. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050923 (2014).

Al-Jayyousi, G. F. et al. Students’ perceptions of a university ‘No smoking’ policy and barriers to implementation: a cross- sectional study. BMJ Open. 11 (6), e043691. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043691 (2021).

Shi, Y. & Cummins, S. E. Smoking cessation services and smoke-free policies at substance abuse treatment facilities: National survey results. Psychiatr Serv. 66 (6), 610–616. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400328 (2015).

Howes, M. et al. Environmental sustainability: a case of policy implementation failure? Sustainability 9 (2), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9020165 (2017).

Phulkerd, S., Sacks, G., Vandevijvere, S., Worsley, A. & Lawrence, M. Barriers and potential facilitators to the implementation of government policies on front-of-pack food labeling and restriction of unhealthy food advertising in Thailand. Food Policy. 71, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.07.014 (2017).

Balane, M. A., Palafox, B., Palileo-Villanueva, L. M., McKee, M. & Balabanova, D. Enhancing the use of stakeholder analysis for policy implementation research: towards a novel framing and operationalised measures. BMJ Glob Health. 5 (11), e002661. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002661 (2020).

Mwendera, C. A. et al. Challenges to the implementation of malaria policies in Malawi. BMC Health Serv. Res. 19 (1), 194. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4032-2 (2019).

Kegler, M. C. et al. Implementation and enforcement of smoke-free policies in public housing. Health Educ. Res. 34 (2), 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyy053 (2019).

Levy, D. E., Adams, I. F. & Adamkiewicz, G. Delivering on the promise of smoke-free public housing. Am. J. Public. Health. 107 (3), 380–383. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303606 (2017).

Cramer, M. E., Roberts, S. & Stevens, E. Landlord attitudes and behaviors regarding smoke-free policies: implications for voluntary policy change. Public. Health Nurs. 28 (1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00904.x (2011).

King, B. A., Mahoney, M. C., Cummings, K. M. & Hyland, A. J. Intervention to promote smoke-free policies among multiunit housing operators. J. Public. Health Manag Pract. 17 (3), E1–E8. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181ffd8e3 (2011).

Hughes, J. R. Smokers’ beliefs about the inability to stop smoking. Addict. Behav. 34 (12), 1005–1009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.013 (2009).

Mohamed, S. F., Juma, P., Asiki, G. & Kyobutungi, C. Facilitators and barriers in the formulation and implementation of tobacco control policies in kenya: a qualitative study. BMC Public. Health. 18 (Suppl 1), 960. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5830-x (2018).

Teh, W. L., Abdin, E., Siva Kumar, P. V. A., Roystonn, F. D. & Wang, K. Measuring social desirability bias in a multi-ethnic cohort sample: its relationship with self-reported physical activity, dietary habits, and factor structure. BMC Public. Health. 23 (1), 415. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15309-3 (2023).

Acknowledgements

First, the authors extend their sincere gratitude to the Bangladesh Center for Communication Programs (BCCP) for its invaluable technical support in undertaking this study. They also would like to thank all participants for generously sharing their opinions and insights. Finally, the authors acknowledge the dedication and hard work of the interviewers involved in data collection.

Funding

This study was supported with funding from the Institute for Global Tobacco Control (IGTC), Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, USA, and the grant contract was locally made through the Bangladesh Center for Communication Programs (BCCP) (Ref: GC#BCCP/Tobacco/2019-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MGK was involved in the conceptualisation and design of the study. MGK, MSI, and MDHH developed the tools of data collection. MGK and MSI trained the interviewers on data collection and transcription and led field work. MGK and TI coded, analysed, and interpreted the data. MGK drafted the manuscript. SMA, MSI, and MDHH substantially edited and refined the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the National Research Ethics Committee under the Bangladesh Medical Research Council (Ethical clearance number: 25003092019). The present study was carried out with strict adherence to the ethical standards and regulations of the ethics committee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kibria, M.G., Islam, T., Alif, S.M. et al. Perceived motivators and barriers to implementation of a smoke-free common area policy in multiunit housing in urban Bangladesh. Sci Rep 15, 45219 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28789-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28789-7