Abstract

The C-reactive protein-albumin-lymphocyte (CALLY) index represents a novel immune-nutritional scoring system. However, the relationship between the CALLY index and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, as well as its association with all-cause and CVD mortality, remains to be elucidated. The binary weighted logistic regression models, Cox proportional hazards model, and Kaplan–Meier survival analysis curves were respectively used to analyze the relationship between CALLY index and outcomes. ROC curve was adopted to compare the predictive abilities of CALLY index and other inflammatory-related indexes. Moreover, restricted cubic splines (RCS) were employed to assess the potential nonlinear relationship between CALLY index and outcomes. We revealed an inverse association between CALLY index and CVD in U.S. general population (OR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.63–0.87). Moreover, elevated CALLY index was significantly associated with reduced risks of both all-cause mortality (HR = 0.62, 95% CI 0.50–0.78) and CVD mortality in CVD participants (HR = 0.68, 95% CI 0.49–0.94). RCS analysis demonstrated a linear relationship between the CALLY index and CVD in the U.S. general population and a non-linear relationship between CALLY index and all-cause and CVD mortality in CVD patients. The ROC analysis indicated that the CALLY index had a better discriminatory ability than other inflammatory-related indexes. Elevated baseline CALLY index levels were independently associated with a decreased incidence of CVD in the U.S. general population, as well as reduced risks of both all-cause mortality and CVD mortality among patients with CVD. This study suggested that the CALLY index had potential utility for risk stratification in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) represent the predominant contributor to global morbidity and mortality, with the WHO projecting its continued dominance as the primary cause of mortality worldwide1. Extensive preclinical investigations have established a strong pathophysiological link between systemic inflammation and CVD progression. Furthermore, experimental studies utilizing well-established CVD animal models have provided compelling evidence that targeted modulation of specific immune-inflammatory pathways may offer potential therapeutic advantages2. Immune cells, including T cells and B cells, play crucial roles in the onset and progression of various CVDs, such as atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and stroke. Currently, several inflammation-related biomarkers have been employed for CVD prognosis prediction, including the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), lymphocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (LHR), monocyte-to-HDL-C ratio (MHR), and platelet-to-HDL-C ratio (PHR). However, these individual biomarkers demonstrate limited capacity to comprehensively reflect systemic pathophysiological abnormalities. Moreover, their clinical utility requires further validation through large-scale, multicenter studies to establish robust evidence for routine clinical implementation.

Hypoalbuminemia, characterized by reduced serum albumin levels, has been observed in individuals suffering from severe myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure (HF), stroke, hip fractures, cancer, and kidney disorders3,4,5. Discovered unexpectedly in 1989, serum albumin (SA) concentration has since been established as a reliable prognostic marker for CVD6. The relationship between reduced SA levels and poor clinical outcomes is considered multifactorial in nature, as evidenced by previous studies7,8. The observed hypoalbuminemia may stem from either systemic inflammatory responses or insufficient nutritional status, both of which have been demonstrated to significantly influence CVD progression and prognosis9,10.

The C-reactive protein-albumin-lymphocyte (CALLY) index is a novel composite biomarker that integrates the simultaneous assessment of systemic inflammation, immune response, and nutritional status11. It is calculated through a standardized formula: (albumin concentration [g/dL] × lymphocyte count [10^9/L])/(C-reactive protein level [mg/L]) × 10^4.12 Several investigations have been conducted to examine the relationship between the CALLY index and disease prognosis11,12,13. These studies consistently demonstrated an inverse association between CALLY index levels and both disease incidence and mortality rates. However, the prognostic significance of the CALLY index in CVD risk prediction and mortality outcomes remains to be fully elucidated. This study aims to investigate the association between CALLY index levels and CVD incidence in the U.S. general population, while also examining its predictive value for all-cause and CVD mortality among patients with established CVD.

Methods

Study population

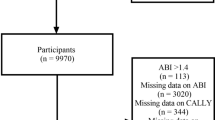

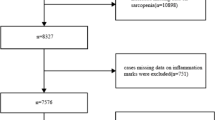

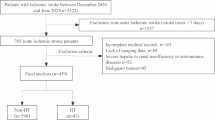

Our data originated from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a comprehensive survey designed to assess the nutritional status and health conditions of the U.S. population. And the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Research Ethics Review Board has approved the NHANES study. Our study examined the relationship between the CALLY index and CVD, along with all-cause and CVD mortality, using data from the NHANES spanning the years 2001 to 2018. The following groups were excluded from the study: (1) Individuals without the data of albumin, lymphocyte and C-reactive protein; (2) Individuals whose survival data were not been recorded; (3) individuals missing the data to calculate SII, NHR, LHR, MHR and PHR. Finally, 36,904 participants were enrolled into our study. The follow-up period began at each participant’s NHANES examination date and continued until the date of death or the end of follow-up on December 31, 2019, whichever occurred first. Participants who were alive at the end of follow-up were right-censored at this date (NCHS Linked Mortality File description). In this study, among 4,313 participants with cardiovascular disease, 1,860 deaths occurred during follow-up. The median survival times were 107, 135, 137, and 154 months for participants in the first to fourth quartiles of the CALLY index, respectively. Figure 1 presents an overview of the participants selection process.

Data collection

Our research included four primary categories of covariates. (1) Demographic and health-related factors was collected, which comprised sex, age, race (White, Black, Mexican and other), education (less than high school, high school diploma and more than high school), marital status (married/living with partner, widowed/divorced/separated and never married), income and poverty (PIR < 1, 1–3 or > 3), smoke (no, yes), alcohol (mild, moderate and heavy), BMI (< 18.5, 18.5–25, ≥ 25) and physical activity (no or less, moderate and heavy). (2) Complete blood count and blood biochemical indicators, including white blood cell (WBC), neutrophils (NEU), platelet (PLT), lymphocytes (LYM), monocyte (MON), C-reactive protein (CRP), albumin (Alb), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) were collected. (3) Comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD) were gathered.

Clinical outcomes

The primary outcomes in our study including incidence of CVD, all-cause mortality and CVD mortality. CVDs included congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease and angina pectoris. The participants was asked “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told [you/SP] that [you/s/he]…had congestive heart failure/coronary heart disease/angina pectoris/myocardial infarction/stroke?”. If the answer was “yes”, the individual was classified as a CVD patient. Since the diagnosis of CVD was based on self-reported data, there is a potential for misclassification.

Futhermore, we accessed the National Death Index (NDI) through the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) to determine the participants’ survival status. And based on the international Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) to identify disease-specific death.

Assessment of independent variable

The CALLY index was computed using the formula: (albumin concentration [g/dL] × lymphocyte count [10^9/L])/(CRP level [mg/L]) × 10^4, offering a comprehensive assessment of both inflammatory and nutritional conditions14.

Additionally, we explored the association of SII, NHR, LHR, MHR, and PHR with CVD, all-cause mortality, and CVD mortality.

SII: (PLT count [10^9/L] × NEU count [10^9/L])/LYM count [10^9/L].

NHR: NEU count [10^9/L]/HDL-C mg/dL)

LHR: LYM count [10^9/L]/HDL-C (mg/dL).

MHR: MON count [10^9/L]/HDL-C (mg/dL).

PHR: PLT count [10^9/L]/HDL-C (mg/dL).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses accounted for the complex, multistage, stratified probability sampling design of NHANES. Sampling weights, strata, and primary sampling units (PSUs) were incorporated into all models to ensure nationally representative estimates. For the combined 2001–2018 survey cycles, multi-cycle examination weights were calculated by dividing the 2-year sample weights (WTMEC2YR) by the number of included cycles (n = 9). To illustrate baseline data, categorical variables were expressed as survey-weighted percentages, while continuous variables were represented as survey-weighted means. Comparisons among these groups were conducted using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and the chi-square (χ²) test for categorical variables. A two-tailed P-value of 0.05 was considered the threshold for statistical significance.

To progressively eliminate the impact of confounding factors on the occurrence of outcomes, we constructed three models. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for sex, age, race, education, marital status and PIR. Model 3 was adjusted for sex, age, race, education, marital status, PIR, BMI, physical activity, smoke, alcohol, hypertension, diabetes and CKD. To explore the relationship between CALLY index and CVD in U.S. general population, the binary weighted logistic regression models was adopted. The Cox proportional hazards model and Kaplan–Meier survival analysis curves were used to assess the correlation of CALLY index with all-cause and CVD mortality. Stratified analysis was conducted for significant covariates, examining the impact of gender and age on the outcomes.

Furthermore, restricted cubic splines (RCS) were employed to assess the potential non-linear relationship between CALLY index and CVD, all-cause mortality, and CVD mortality. Receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC) were generated to compare the predictive abilities of the CALLY index and inflammatory-related indexes, including SII, MHR, NHR, PHR, and LHR for CVD, all-cause and CVD mortality. A subgroup analysis was performed on significant covariates, considering potential effect modifiers, including sex, age, race, education, marital status, PIR, BMI, physical activity, smoke, alcohol, hypertension, diabetes and CKD. Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.2).

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

Table 1 showed the baseline characteristics of 36,904 participants with or without CVD. Compared to non-CVD participants, CVD patients tended to be male, older, Mexican, married/living with partner, individuals with more than high school education and moderate income. Moreover, CVD patients was more likely to be higher BMI, smoker and mild drinker. The biochemical indicator revealed higher WBC, PLT, LYM, MON, CRP, TG, and lower HDL-C, TC, LDL-C in these patients. Unsurprisingly, CVD patients frequently presented with comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, and CKD. The weighted baseline characteristics are summarized in Table S1.

To further explore the association between CALLY and CVD, we selected CVD patients from all participants. These patients were then categorized into four quartiles based on CALLY index values to examine their baseline characteristics (Table 2). Compared to lower CALLY indexes, CVD patients with higher CALLY are likely to be male, Mexican, middle-income population, and individuals who were married or living with partners. Additionally, higher PLT, LYM, HDL-C, Alb are associated with higher CALLY index in CVD patients.

The association of CALLY (log-transformed) with cardiovascular disease in all participants

When treated as a continuous variable, the CALLY index exhibited a significant inverse association with CVD in the U.S. general population (p < 0.001 in all models). Similarly, when analyzed as a categorical variable, participants in the highest quartile (Q4) showed a significantly reduced risk of CVD compared to those in the lowest quartile (Q1) in all adjusted models (p < 0.001). Moreover, in all models, a significant downward trend was observed between the CALLY index and the risk of CVD (p for trend < 0.001) (Table 3). To validate the robustness of our findings, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding participants who died within the first 2 years of follow-up or had baseline CRP levels > 10 mg/L. The results demonstrated consistent effect estimates, confirming the stability of our primary model (Table S2). Furthermore, In the confounders-only sensitivity analysis (excluding mediators including CKD, BMI, and diabetes), the protective association of the CALLY index was more pronounced (OR = 0.62) than in the fully adjusted model (OR = 0.74) (Table S3).

Additionally, RCS analysis demonstrated a linear association between the CALLY index and CVD in the U.S. general population (P-overall < 0.001; P-nonlinear = 0.513) (Fig. 2). Compared with other inflammation-related indicators (SII, NHR, LHR, MHR, and PHR), the CALLY index achieved the highest AUC value (0.595) for CVD prediction (Fig. 3).

Comparing the predictive ability of CALLY, SII, NHR, LHR, MHR, and PHR for cardiovascular disease in the U.S. general population using ROC curves and AUC values. Adjusted for sex, age, race, education, marital status, PIR, BMI, physical activity, smoke, alcohol, hypertension, diabetes and CKD, except the subgroup factors themselves.

The association of log (CALLY) with cardiovascular disease in all participants stratified by sex and age

Furthermore, we stratified all participants by sex and age. Interestingly, after adjusted for sex, age, race, education, marital status, PIR, BMI, physical activity, smoke, alcohol, hypertension, diabetes and CKD, sex-stratified logistic regression analysis revealed a significant association between the CALLY index and the incidence of CVD in both male and female groups (Table 4). RCS analysis indicated that a CALLY index > 7.62 appeared to confer greater protective effects against CVD in females (Fig. 4A).

The dose–response relationship between CALLY index with cardiovascular disease in U.S. general population stratified by sex (A) and age (B). Adjusted for race, education, marital status, PIR, BMI, physical activity, smoke, alcohol, hypertension, diabetes and CKD, except the subgroup factors themselves.

Furthermore, the CALLY index demonstrated an inverse association with CVD among younger participants (Table 4). RCS analysis further revealed that in this subgroup, a CALLY value exceeding 8.08 was associated with a reduced risk of CVD (Fig. 4B).

Subgroup analysis of the association between CALLY index and cardiovascular disease in all participants

To further assess the impact of CALLY index on CVD, subgroup analysis was conducted according to sex, age, race, education, marital status, PIR, BMI, physical activity, smoke, alcohol, hypertension, diabetes and CKD (Fig. 5, Table S4). The CALLY index was more closely related to CVD in participants who were female, younger, White, never married participants, smoker, heavy drinker and who did not have hypertension, diabetes and CKD.

The relationship between log (CALLY) and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in CVD patients

To investigate the association between the CALLY index and all-cause mortality as well as CVD mortality among patients with CVD, we conducted further analysis on this specific population. Kaplan-Meier curves demonstrated a graded reduction in the risk of all-cause and CVD mortality across increasing quartiles of the CALLY index (P for log-rank test < 0.05) (Fig. 6). Furthermore, we construed three Cox proportional hazards regression models to verified the relationship of CALLY index with all-cause and CVD mortality. As a continuous variable, CALLY index was inversely associated with all-cause and CVD mortality in CVD patients. Meanwhile, when the CALLY index was treated as a categorical variable, a significant inverse correlation was consistently observed with both all-cause and CVD mortality among CVD patients across all three models (Table 5). The sensitivity analysis demonstrated stable effect estimates for the associations between the CALLY index and both all-cause and CVD mortality after excluding participants who died during the initial 2-year follow-up period or had baseline CRP levels > 10 mg/L (Table S5-6). In the confounders-only sensitivity analysis (excluding mediators including CKD, BMI, and diabetes), the protective association of the CALLY index was more pronounced (For all-casue mortality: HR = 0.52; For CVD mortality: HR = 0.61) than in the fully adjusted model For all-casue mortality: HR = 0.54; For CVD mortality: HR = 0.68)) (Table S7-8).

RCS analysis showed a non-linear correlation between CALLY index and all-cause and CVD mortality in patients with CVD (For all-cause mortality, p-overall < 0.001, p-nonlinear = 0.002; For CVD mortality, p-overall < 0.001, p-nonlinear = 0.038) (Fig. 7). Additionally, among the indices compared, the CALLY index showed the highest AUC values for predicting all-cause mortality (AUC = 0.598) and CVD mortality (AUC = 0.605) in CVD patients. (Fig. 8).

RCS analysis of the association between the CALLY index and all-cause (A) and cardiovascular mortality (B) in the U.S. general population. Adjusted for sex, age, race, education, marital status, PIR, BMI, physical activity, smoke, alcohol, hypertension, diabetes and CKD, except the subgroup factors themselves.

Comparing the predictive ability of CALLY, SII, NHR, LHR, MHR, and PHR for all-cause (A) and cardiovascular mortality (B) in the U.S. general population using ROC curves and AUC values. Adjusted for sex, age, race, education, marital status, PIR, BMI, physical activity, smoke, alcohol, hypertension, diabetes and CKD, except the subgroup factors themselves.

Subgroup analysis of the association between CALLY index and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease

We stratified CVD patients into different subgroups by sex, age, race, education, marital status, PIR, BMI, physical activity, smoke, alcohol, hypertension, diabetes and CKD. Except for the PIR subgroup (For all-cause mortality: P for interaction = 0.007; For cardiovascular mortality: P for interaction = 0.003), there was no significant interaction in most subgroups. The CALLY index was closely related to all-cause and CVD mortality in PIR < 1 subgroup (Fig. 9, Table S9-S10).

Discussion

In this study, we identified a significant inverse association between the CALLY index and the risk of CVD, along with all-cause and CVD-specific mortality. Specifically, a higher CALLY index was linked to a reduced risk of CVD in the U.S. general population. Similarly, among CVD patients, elevated CALLY index levels were associated with decreased risks of both all-cause and CVD-specific mortality. These findings suggest that the CALLY index serves as a protective indicator, correlating with a lower incidence of CVD in the U.S. general population and improved survival outcomes in CVD patients. Since the diagnosis of CVD was based on self-report, there is a risk of misclassification. We acknowledge that this misclassification is likely to be non-differential, meaning that patients may either underreport or overreport their condition. Such non-differential misclassification would generally tend to attenuate the observed association strengths toward the null, rather than overestimate them.

CALLY index is an immune-inflammatory-nutritional biomarker, which reflects inflammation and immune system, and nutrition statues simultaneously. There have been several inflammatory-related indexes was associated with CVD and mortality, including SII, NHR, LHR, MHR, PHR15,16,17,18. However, our findings demonstrated that the CALLY index exhibited superior predictive capability compared to these inflammation-related indices. This enhanced performance may be attributed to the inclusion of albumin in the CALLY index, which offered a more comprehensive evaluation of the body’s overall health status.

Albumin play a crucial role in maintaining internal homeostasis. Firstly, albumin deficiency reduces the deformability of red blood cells, subsequently increasing blood viscosity19. In clinical practice, SA is used to maintain the permeability of capillary membranes20. Secondly, hypoalbuminemia impairs the vasodilatory response to nitric oxide (NO)21. Thirdly, hypoalbuminemia impairs toxin clearance, reduces cholesterol transport capacity, and weakens the body’s anticoagulant and antioxidant defenses22,23,24,25.

Furthermore, immune cells play an indispensable role in cardiac injury and repair processes26. However, the immune response to cardiac injury is highly complex and remains incompletely understood. The immune response is intricately regulated by variations in injury type, host-specific factors, and environmental conditions. The robust sterile inflammation observed in the injured heart is mediated through multiple interconnected signaling pathways27,28. Furthermore, diverse cell types within the immune system engage in complex interactions with each other and with resident cardiac fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and cardiomyocytes throughout the processes of cardiac injury and repair29.

Inflammation promotes endothelial cell damage and the progression of atherosclerotic plaques, playing a critical role in the development and pathogenesis of CVD30. In the case of myocardial infarction, inflammation can be both beneficial and harmful. It is involved in infarct resolution, repair, and remodeling, but persistent inflammation can enlarge the infarct area and hinder cardiac recovery31,32. A Mendelian analysis revealed that elevated CRP levels are associated with a higher risk of hypertension and hypertensive heart disease33.

The CALLY index has demonstrated an inverse association with the risk of several diseases. In a cross-sectional study, the CALLY index was inversely associated with the risk of cardiorenal syndrome34. And its predictive ability was more effectively than other inflammatory markers. Another study suggests that a higher CALLY index is associated with better prognosis in colorectal cancer patients, which is similar with our findings35. Ji et al. indicated that the CALLY index exhibited a protective effect against both short- and long-term major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)11. Müller et al. identified the CALLY index as an independent prognostic factor for overall survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma receiving transarterial chemoembolization36. In our study, after stratifying all participants by sex and age, the high CALLY index (CALLY index > 7.62 or 8.08) seemed to be more protective in female and younger population. It could be attributed to the higher estrogen and progesterone levels in female. And older adults tend to have more comorbidities, which could potentially obscure the benefits associated with a higher CALLY index. Furthermore, the patients with CVD form the U.S. general population was selected to explore the CALLY index with all-cause and CVD mortality. Kaplan-Meier curves also demonstrated a progressive reduction in the risk of all-cause and CVD mortality across higher quartiles of the CALLY index. The RCS analysis showed a non-linear relationship between CALLY index and both all-cause and CVD mortality. And Xu et al. also revealed a non-linear association of CALLY index with cardiorenal syndrome34. Before the CALLY index proposed in this study can be applied in clinical practice, several key issues must be addressed. Furthermore, although the ROC curve confirms that the CALLY index has better predictive performance for CVD compared to other inflammation-related indicators, its predictive capability remains limited. Therefore, this readily available composite index could be integrated with other clinically important variables in future studies to develop a multivariate predictive model. Such an approach would significantly enhance the clinical utility of the CALLY index. Future research should focus on establishing clinically applicable cut-off values for different populations, verifying its reproducibility across various laboratory platforms and reagents, and conducting comprehensive health economic evaluations to demonstrate its cost-effectiveness. Clarifying these issues is crucial for translating the CALLY index from an epidemiological tool into an effective clinical decision-support tool.

Overall, our study was the first to propose the negative association between CALLY index and both CVD and all-cause and CVD mortality in U.S. general population or patients with CVD. However, there are still several limitations in our study. Firstly, the diagnosis of CVD was from self-report of patients, which is subject to potential recall bias and misclassification. Participants may underreport or be unaware of a prior diagnosis, leading to non-differential misclassification that could attenuate the observed associations. While self-report of major cardiovascular conditions has been used and validated in large surveys, future studies with adjudicated clinical endpoints would be valuable to confirm our findings. Secondly, the evidentiary strength of cross-sectional studies is inferior to that of prospective studies and randomized controlled trials. Thirdly, Although we adjusted for numerous covariates, residual confounding is likely to persist. Key factors such as medication use, dietary habits, and comorbidity severity are not fully captured in the NHANES database, and these unmeasured confounders may influence our findings. Fourthly, some visualization and ROC plotting functions in R do not fully support complex survey weights, the graphical representations of ROC curves and survival plots were based on model-predicted probabilities, which may slightly underestimate the true sampling variability.Therefore, our findings require further validation through large-scale prospective studies in the future to enhance their robustness.

Conclusion

This study confirms a significant negative correlation between the CALLY index and cardiovascular disease risk in the U.S. general population. Furthermore, among individuals with established cardiovascular disease, the CALLY index also shows significant inverse associations with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease-specific mortality. Compared to traditional inflammation-related indicators such as SII, NHR, LHR, MHR, and PHR, the CALLY index demonstrates stronger associations with mortality risk and better predictive performance in both the U.S. general population and patients with CVD. These findings provide compelling evidence supporting the potential clinical value of the CALLY index.

Data availability

The raw data can be obtained from the official NHANES website: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

Abbreviations

- CALLY:

-

The C-reactive protein-Albumin-Lymphocyte

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic splines

- SII:

-

Systemic immune-inflammation index

- NHR:

-

Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio

- LHR:

-

Lymphocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein ratio

- MHR:

-

Monocyte to HDL-C Ratio

- PHR:

-

Platelet to HDL-C Ratio

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- HF:

-

heart failure

- SA:

-

Serum albumin

- NCHS:

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- PIR:

-

Poverty-Income Ratio

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

- NEU:

-

Neutrophils

- PLT:

-

Platelet

- LYM:

-

Lymphocytes

- MON:

-

Monocyte

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- Alb:

-

Albumin

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic curves

References

Maffia, P. & Cirino, G. Targeting inflammation to reduce cardiovascular disease risk. Br. J. Pharmacol. 174, 3895–3897 (2017).

Welsh, P., Grassia, G., Botha, S., Sattar, N. & Maffia, P. Targeting inflammation to reduce cardiovascular disease risk: a realistic clinical prospect? Br. J. Pharmacol. 174, 3898–3913 (2017).

Rabbani, G., Ahn, S. N. & Review Roles of human serum albumin in prediction, diagnoses and treatment of COVID-19. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 193, 948–955 (2021).

Akirov, A., Masri-Iraqi, H., Atamna, A. & Shimon, I. Low albumin levels are associated with mortality risk in hospitalized patients. Am. J. Med. 130, 1465e11–1465e19 (2017).

Chien, S. C., Chen, C. Y., Lin, C. F. & Yeh, H. I. Critical appraisal of the role of serum albumin in cardiovascular disease. Biomark. Res. 5, 31 (2017).

Phillips, A., Shaper, A. G. & Whincup, P. H. Association between serum albumin and mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other causes. Lancet 2, 1434–1436 (1989).

Lan, C. C., Su, W. L., Yang, M. C., Chen, S. Y. & Wu, Y. K. Predictive role of neutrophil-percentage-to-albumin, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratios for mortality in patients with COPD: evidence from NHANES 2011–2018. Respirology 28, 1136–1146 (2023).

Zhou, J. et al. Albumin-corrected Fructosamine predicts all-cause and non-CVD mortality among the very elderly aged 80 years or older without diabetes. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 77, 1673–1682 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. The associations of plant-based protein intake with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients on peritoneal Dialysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 30, 967–976 (2020).

Lee, Y. T. et al. Artificial intelligence-enabled electrocardiography detects hypoalbuminemia and identifies the mechanism of hepatorenal and cardiovascular events. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 895201 (2022).

Ji, H. et al. Prognostic significance of C-reactive protein-albumin-lymphocyte (CALLY) index after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Int. Immunopharmacol. 141, 112860 (2024).

Feng, J., Wang, L., Yang, X. & Chen, Q. Clinical significance of preoperative CALLY index for prognostication in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma undergoing surgery. Sci. Rep. 14, 713 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Superiority of CRP-albumin-lymphocyte index as a prognostic biomarker for patients with gastric cancer. Nutrition 116, 112191 (2023).

Iida, H. et al. Superiority of CRP-albumin-lymphocyte index (CALLY index) as a non-invasive prognostic biomarker after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 24, 101–115 (2022).

Cao, Y. et al. Association of systemic immune inflammatory index with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in hypertensive individuals: results from NHANES. Front. Immunol. 14, 1087345 (2023).

Chuang, S. M. et al. Neutrophil-to-high-density lipoprotein ratio (NHR) and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as prognostic biomarkers for incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: A comparison study. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 20, 100869 (2024).

Song, Y. et al. Combination model of neutrophil to high-density lipoprotein ratio and system inflammation response index is more valuable for predicting peripheral arterial disease in type 2 diabetic patients: A cross-sectional study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1100453 (2023).

Ye, H. et al. Non-linear association of the platelet/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio with bone mineral density a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 23, 300 (2024).

McGinley, E., Lowe, G. D., Boulton-Jones, M., Forbes, C. D. & Prentice, C. R. Blood viscosity and haemostasis in the nephrotic syndrome. Thromb. Haemost. 49, 155–157 (1983).

Demling, R. H. Effect of plasma and interstitial protein content on tissue edema formation. Curr. Stud. Hematol. Blood Transfus. 5336–52. (1986).

Keaney, J. F. et al. NO forms an adduct with serum albumin that has endothelium-derived relaxing factor-like properties. J. Clin. Invest. 91, 1582–1589 (1993).

Quinlan, G. J., Martin, G. S. & Evans, T. W. Albumin: biochemical properties and therapeutic potential. Hepatology 41, 1211–1219 (2005).

Stocker, R. et al. Antioxidant activity of albumin. -bound bilirubin - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 30]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3475708/Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 84, 5918–5922 (1987).

Sankaranarayanan, S. et al. Serum albumin acts as a shuttle to enhance cholesterol efflux from cells. J. Lipid Res. 54, 671–676 (2013).

Mikhailidis, D. P., Mikhailidis, A. M. & Dandona, P. Effect of human plasma proteins on stabilisation of platelet anti-aggregatory activity of Prostacyclin. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 19 (Pt 4), 241–244 (1982).

Rurik, J. G., Aghajanian, H. & Epstein, J. A. Immune cells and immunotherapy for cardiac injury and repair. Circ. Res. 128, 1766–1779 (2021).

Suetomi, T. et al. Inflammation and NLRP3 inflammasome activation initiated in response to pressure overload by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II δ signaling in cardiomyocytes are essential for adverse cardiac remodeling. Circulation 138, 2530–2544 (2018).

Jaén, R. I. et al. Innate immune receptors, key actors in cardiovascular diseases. JACC Basic. Transl Sci. 5, 735–749 (2020).

Epelman, S. et al. Embryonic and adult-derived resident cardiac macrophages are maintained through distinct mechanisms at steady state and during inflammation. Immunity 40, 91–104 (2014).

Zhuang, Q. et al. Association of high sensitive C-reactive protein with coronary heart disease: a Mendelian randomization study. BMC Med. Genet. 20, 170 (2019).

Lambertsen, K. L., Finsen, B. & Clausen, B. H. Post-stroke inflammation-target or tool for therapy? Acta Neuropathol. 137, 693–714 (2019).

Tripathi, H. et al. Myeloid-specific deletion of lipid Plpp3 (phosphate phosphatase 3) increases cardiac inflammation after myocardial infarction. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 43, 379–381 (2023).

Kuppa, A., Tripathi, H., Al-Darraji, A., Tarhuni, W. M. & Abdel-Latif, A. C-reactive protein levels and risk of cardiovascular diseases: a two-sample bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 9129 (2023).

Xu, Z. et al. Associations of C-reactive protein-albumin-lymphocyte (CALLY) index with cardiorenal syndrome: insights from a population-based study. Heliyon 10, e37197 (2024).

Yang, M. et al. Association between C-reactive protein-albumin-lymphocyte (CALLY) index and overall survival in patients with colorectal cancer: from the investigation on nutrition status and clinical outcome of common cancers study. Front. Immunol. 14, 1131496 (2023).

Zhang, J., Zhao, Q., Liu, S., Yuan, N. & Hu, Z. Clinical predictive value of the CRP-albumin-lymphocyte index for prognosis of critically ill patients with sepsis in intensive care unit: a retrospective single-center observational study. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1395134 (2024).

Funding

This work was supported by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2025JJ50643).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YW and YZ: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, validation, visualization and writing–original. YT: conceptualization, project administration and writing–review & editing. YC: funding acquisition, software and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the NHANES Institutional Review Board, and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with all NHANES participants providing signed informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wen, Y., Zhang, Y., Tang, Y. et al. Protective role of the C-reactive protein-albumin-lymphocyte (CALLY) index for cardiovascular risk and mortality. Sci Rep 15, 44946 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28808-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28808-7