Abstract

With the rapid development of the automation industry, the performance and functional requirements of heavy-duty industrial robots (HDIRs) are rising. However, there are problems such as imitation and plagiarism, and neglect of aesthetic value in the current morphological design field of HDIRs, which restrict the coordinated development of visual and functional aspects. This study proposed an intelligent and innovative morphological optimization HDIR design method based on Kansei Engineering, curve blending algorithms, and artificial intelligence-generated content. This research aimed to integrate functionality with aesthetics for HDIRs, establishing a distinct brand identity through signature curved forms to create an eye-catching visual appeal and strong brand influence in the industrial environment. The design practice used a 210 kg welding HDIR as an example, which not only illustrates the application process and final results of the proposed design method in detail but also demonstrates the robot’s capabilities. Moreover, its effectiveness and feasibility were preliminarily verified through a perceptual questionnaire and the Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process. This intelligent innovative morphological optimization design method will help overcome the limitations of traditional industrial robot design. It meets the dual needs of modern industry for robot performance and morphology, and provides new perspectives and ideas for researchers in the field of industrial robot design. The research results enrich the theory and practice of industrial robot design, holding significant importance for enhancing the market competitiveness of products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heavy-duty industrial robots (HDIRs) possess a strong load capacity and can play a crucial role in high-intensity tasks, such as the assembly, handling, and welding of large objects, in high-end manufacturing fields such as automotive manufacturing, aerospace, and port logistics. They are the core, flexible, intelligent equipment in these scenarios1. Their forms are divided into two categories: heavy-load mobile robots (AGVs) and heavy-load fixed multi-joint robots2. HDIRs’ importance stems from the significant improvement in production efficiency. According to statistics from the International Federation of Robotics, China’s industrial robot installations accounted for 51% of the global total in 2023, with a stock of nearly 1.8 million units3. These statistics underscore its strategic position as a key indicator of the country’s advanced manufacturing capabilities. Because the manufacturing industry accelerates its transformation to intelligence, the global heavy-duty robot market is expected to continue to expand at a compound annual growth rate of 4.2%, driving academia and industry to focus on its performance optimization4. Given the increasing needs for HDIRs, the design of HDIRs becomes highly important and receives considerable research attention.

The design and research of HDIRs primarily focus on structural optimization, mission performance improvement, automation, and human-computer interaction5. Chinese companies have achieved remarkable results in localizing core components and innovating control systems. However, the R&D model oriented towards industrial applications has led to an obvious functional convergence in design. Most market products imitate the mechanical configuration of leading companies, resulting in a highly homogenized appearance and insufficient consideration of aesthetics6. This phenomenon stems from disciplinary barriers between structural engineers and industrial designers. While engineers typically prioritize functional realization, designers focus on incorporating aesthetic elements but often lack a deep understanding of manufacturing technology7. The morphological design of HDIRs is crucial because it impacts market competitiveness and shapes users’ first impression and acceptance of the product. A thoughtful and unique design helps a product stand out, enhances its added value, and strengthens its brand identity. Despite this importance, research in the field remains limited, with a notable lack of innovative design methodologies for HDIRs.

Artificial intelligence-generated content (AIGC) technology is reshaping the industrial design paradigm. The core value of AIGC technology is its ability to transform design intentions into diverse solutions using algorithms such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). This process greatly improves innovation efficiency8. In the fields of automobile styling and rail transportation equipment, AIGC technology has achieved multimodal generation applications. For example, it can automatically generate interior and exterior renderings based on keywords or integrate the features of different models to output customized design solutions9. Using functions such as automated line drawing and coloring, AIGC technology dramatically compresses the traditional design cycle from weeks to hours. At the same time, it serves as a powerful tool for inspiring breakthrough creativity10. NVIDIA GTC 2025 Global Technology Conference further verified the universality of this technology in industrial product design, covering a multi-level enabling path from general knowledge to customization11. However, the application of AIGC technology in the field of HDIRs remains underdeveloped. Existing cases primarily focus on the appearance generation of consumer-grade products, lacking coordinated optimization of engineering parameters and aesthetic attributes.

Given the above research gap, this study aimed to propose a novel robotic morphology design method focused on high-payload spot-welding robots in the automotive industry. The design method integrates Kansei Engineering (KE) and AIGC technology to meet users’ needs and increase the efficiency of morphological HDIR design. The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section "Related work", the research status of the performance and structural design of HDIRs is reviewed. Then, the application of KE to HDIR morphological design and the use of AIGC technology within industrial design are explained. In Section "Research method", a morphological optimization design method for industrial robots based on KE and AIGC technology is proposed to solve the above research gap. In Section "Process and results", the research results are presented through the morphological optimization design case of a 210 kg welding HDIR. In Section "Comprehensive practice of shape design of 210 kg welding HDIRs", the effectiveness and feasibility of the proposed method are verified. In Section "Discussion", the findings, advantages and limitations of the research method are discussed. Finally, in Section "Conclusions", the research conclusions are given.

Related work

Research status of the performance and structural design of HDIRs

The design of HDIRs is a highly specialized and technology-intensive field. It involves multiple disciplines, such as mechanical engineering, electronic engineering, control theory, and artificial intelligence12. There are different aspects of the design of HDIRs, which can be developed from two aspects: performance structure and morphology. In research on the performance structure of HDIRs, many scholars are committed to improving the working efficiency and stability of robots by enhancing components and conducting dynamic analysis13. For example, Chen et al.14 addressed the issues of large driving torque and high energy consumption in HDIRs by modifying the transmission mechanism design and eliminating the balancing cylinder. They also combined kinematics and dynamics analysis to verify the effectiveness of the structural optimization, significantly reducing redundant energy consumption. Sun et al.15 focused on the conceptual design of HDIRs and the improvement of overall performance, striving to improve the overall working efficiency of robots. In addition, Yin16 significantly improved the handling efficiency of stacking robots through a comprehensive research method.

The structural design of HDIRs is a key factor in ensuring that the robot can withstand and operate under high loads. Current research on the body of HDIRs mainly focuses on the optimization of structural performance analysis. Chen et al. conducted research on the body structure design of HDIRs for specific loading, handling, and stacking scenarios. For example, a multi-specification cargo loading robot with automatic detection was designed, and the ANSYS Workbench platform was used to ensure that its telescopic mechanism met the working requirements17. Wei et al. used the Denavit-Hartenberg method and MATLAB, combined with ADAMS and ANSYS Workbench, to conduct kinematic and transient dynamic simulations of heavy-duty palletizing robots. Wu et al.18 designed a material transfer robot that meets specific requirements and conducted structural and dynamic characteristic analysis19. Ko et al.20 introduced the design process for heavy-duty handling robots. In a related study, Chung et al.21 discussed the application of a specific analysis technology. Shang et al.22 proposed a new drive form and established a kinematic model of a heavy-duty mobile robot. Miao et al.23 completed a series of research from structural design to dynamic simulation for heavy-duty handling robots on production lines. These studies have achieved remarkable advancements in enhancing the structural performance of HDIRs, providing a strong guarantee for the stable operation of robots in complex industrial environments. However, they focus more on structural performance, while relatively less consideration is given to morphological design.

Research status of KE in the morphological design of HDIRs

The morphological design of HDIRs has a pivotal impact on the human-machine interaction experience and the product’s market competitiveness. KE is a discipline that integrates users’ emotions and aesthetic preferences into product design24. The morphological design of HDIRs directly affects the usability and safety of human-computer interaction and plays a key role in brand awareness and market competitiveness25. To bridge the gap between technological rationality and user sensibility, it is urgent to introduce a methodology that can quantify and translate emotions and aesthetic needs into design elements26. As an interdisciplinary field, KE systematically translates user emotions and preferences into design decisions by integrating perception evaluation and styling. The purpose of KE is to integrate a product’s functionality with its aesthetics, thereby enhancing its market value and user experience. While KE has been applied in robotics to areas such as service robots28, social robots29, and human-robot collaboration30,31, its application to the specific field of HDIRs remains a largely underexplored area of research.

In existing industrial robot research, Zhou et al.32 improved the efficiency of industrial robot morphological design in meeting users’ sensory needs by constructing a sensory image space. Chen et al.33 introduced the KE theory and used the semantic difference method and the KAWAJI method to extract design elements from the three levels of sensation, perception, and association. Forming a semantic space provides a reference method for the design of industrial robot modeling. Based on KE, the design process and evaluation of industrial robots were further optimized34. Wang et al.35 used qualitative and quantitative methods to explore the relationship between perceptual imagery and robot modeling characteristics. Taking a 7-degree-of-freedom industrial robot as the object, the design perception experience was enhanced through questionnaire surveys and eye-tracking technology. Taking a glass substrate transfer robot as an example, a modular design method was proposed based on KE36,37. Xiao et al. not only conducted an in-depth study on the morphological design of a dual-arm industrial robot, but also proposed an intelligent perception design method based on virtual reality and physiological signals. They also integrated Chinese traditional culture into product design, providing a new perspective for the innovation of modern mechanical product design38,39,40. Cheng et al. innovatively proposed the concept of an industrial robot perception intention space construction model based on the demands of users and experts. It promoted the in-depth participation of users and experts in all stages of the research41. KE is difficult to apply in the design field because it needs to process complex data and cognitive processes, which makes coding and measurement difficult42. It is not easy to integrate user perception needs into kinematic design. Benaissa et al.43 found that user evaluation is affected by multiple factors. Integrating complex and ambiguous user needs into design is a challenge for designers. Previous studies on the morphological design of HDIRs have primarily focused on engineering and have rarely considered optimizing their form through KE. This results in the morphological design of robots often ignoring people’s subjective feelings and aesthetic needs while meeting industrial needs. It is challenging to stand out in the market competition, which is a significant shortcoming in current research.

In the field of morphological industrial robot design, the application of KE has gradually received attention. Through KE, the user’s emotional resonance and aesthetic value of the robot’s appearance can be fully considered, allowing for the design of products that better meet user expectations. Professor Nagamachi pointed out that with the correct application of KE, the quality and performance of the product can be ensured to reach a certain level, and emphasized that KE can guarantee a 100% product success rate44.

Research status of AIGC technology in the field of industrial design

AIGC technology refers to a new type of content production method that utilizes artificial intelligence technologies, such as deep learning, to automatically generate multimodal content, encompassing text, images, audio, and video through the learning of large-scale data45. AIGC technology has demonstrated significant potential in the field of industrial design. It is developing rapidly and is gradually becoming an important auxiliary tool for designers46. Currently, the representative software for AIGC-based image generation in the design field includes Stable Diffusion and Midjourney47. Stable Diffusion can quickly generate multiple high-quality design solutions based on the designer’s simple description or sketch, greatly improving design efficiency. At the same time, it can generate realistic product renderings in a short time, which helps designers intuitively display the design effect, facilitating communication with customers and solution optimization48. Midjourney can transform a sentence into a visually striking concept image at the lowest cost and the fastest speed, helping designers broaden their thinking, impress clients, and push creativity forward49. For example, Lu et al. developed a car design thinking model driven by AIGC technology. They thoroughly explored the significant role of this technology in the morphological design process of car products and the innovation and reformulation of the thinking model. Moreover, they verified the feasibility of the model through practical cases, effectively promoting the deep integration of artificial intelligence and the design field50. On this basis, Li et al. started from the perspective of manufacturing productivity transformation and, in combination with the actual situation of manufacturing in Guangdong Province of China, conducted a detailed analysis of the application potential of AIGC technology in product design51. Peng et al.52 used the semantic analysis and metaphor expression techniques in the process of human-computer dialogue, and through dialogues with AIGC technology, utilizes the text-to-image technology to optimize the design process of high-end audio equipment.

In the field of industrial robots, AIGC technology can assist designers in training large models through text prompts or design plan manuscripts, generating a variety of design samples that provide designers with new sources of inspiration and multiple alternative design plans53. However, the application of AIGC technology in industrial product design is not without challenges. While AIGC technology faces challenges such as data set limitations and high training costs54, it remains a tool with immense potential. Currently, its application to the morphological design of HDIRs is a largely unexplored area of research. If leveraged effectively, AIGC is poised to bring significant breakthroughs to this field of industrial design.

Based on the current research, the suggestions for the morphological design of industrial robots are largely general and lack specificity. In particular, there is an obvious research gap in the morphological design of HDIRs. Although some studies have begun to examine product design from the perspective of user emotions, they often ignore the importance of AIGC technology and corporate product genes in product design. In response to the above problems, this study took a six-axis 210 kg welding HDIR as an example to guide the morphological optimization design.

Research method

Related theories and methods

Shape grammar and CBA

Shape grammar (SG) is a design method based on shape change proposed by Stiny and Gips in 197255. The essence of SG is the technology of redesigning or modifying the initial shape with the help of rules56. Mature products, such as cars, mobile phones, and cameras, utilize SG to inherit family design genes57. For example, Michael et al. used Harley-Davidson motorcycles as an example to establish the connection between brand and shape design by encoding shape rules58. Mccormack et al.59 also proved the advantages of SG in maintaining product recognition and appearance innovation through the analysis of Buick front design. They realized the innovative design of the inner cover of vehicles through interactive rule application and used SG to generate structures that are both functional and aesthetically pleasing60. Zhu et al.61 used SG to conduct in-depth research on the design of BYD automobile derivatives. SG requires a rich understanding of professional knowledge when dealing with complex parameter encoding. Although some scholars use Rhino software to process the complex parameter encoding, computer and mathematical skills are still required.

Generally, in product design, morphological element curves are the key to achieving morphological blending and morphological synthesis62. Blending is the process of generating an intermediate contour sequence that combines the geometric features of source shapes. This process is achieved by establishing the correspondence of feature points and interpolating between the contour curves. Critically, the resulting sequence must be manufacturable and analyzable63. Unlike the image space deformation that focuses on visual effects, this geometric-level two-dimensional contour curve blending utilizes the morphological element curve as the basic unit, directly serving the morphological synthesis and shape grammar construction in industrial product design64. To achieve curve blending, Chen and Parent65 introduced three methods for establishing the corresponding feature points of two curves: middle area, ray shooting, and minimum distance. Subsequently, Sederberg and Greenwood66 proposed a simple and effective curve blending method based on the area middle method. Hsiao and Chuang proposed a curve blending method based on the ray shooting method, which can obtain morphological curves using different blending algorithms. In a recent study, Hsiao et al.67 proposed a hybrid method based on ray casting to demolish and reconstruct morphological curves to maintain morphological features. Based on the above research, when the corresponding characteristic points of the two morphological element curves are established, it can be concluded that there are four types of CBA available for selection50. This method places the two curves in a two-dimensional coordinate system and uses the coordinate values of the feature points corresponding to the two curves as calculation parameters. The optional formulas are as shown in equations (1) to (4).

-

1.1.1.1.1.

Weighted arithmetic mean method:

$${\text{C}=\text{w}}_{1}\times {\text{g}}_{1}+{\text{w}}_{2}\times {\text{g}}_{2}$$(1) -

2.2.2.2.2.

Weighted geometric mean method:

$$\text{C}=\sqrt{{{\text{g}}_{1}}^{{\text{w}}_{1}}+{{\text{g}}_{2}}^{{\text{w}}_{2}}}$$(2) -

3.3.3.3.3.

Weighted harmonic mean method:

$$\text{C}=\frac{1}{\frac{{\text{w}}_{1}}{{\text{g}}_{1}}+\frac{{\text{w}}_{2}}{{\text{g}}_{2}}}$$(3) -

4.4.4.4.4.

Generalized weighted mean method:

$$\text{C}= {\left[{\left({\text{w}}_{1}\times {\text{g}}_{1}\right)}^{\alpha }+{\left({\text{w}}_{2}+{\text{g}}_{2}\right)}^{\alpha }\right]}^{1/\alpha }$$(4)

In the formula, g1 and g2 are the feature point sets of the two curves, w1 and w2 are the weight values of the feature point sets, α is the attitude parameter value, and C is the new curve generated by the mixture.

Ray-firing method

The ray-firing method was initially limited to morphological transitions between two unexpanded curve segments. This study extended this method to arbitrary closed curves and constructs an innovative framework for the morphological optimization of industrial robots. This study demonstrates that the Ray-firing method is a powerful tool for innovative design, capable of retaining a brand’s original visual characteristics to ensure brand consistency and preserve the value of brand assets in new industrial robot designs50,68.

Step 1: Use continuous cubic Bezier curves to draw two morphological curves (such as curve a and curve b). And obtain the feature point sets of the two curves, namely {a1, a2, a3,..., a10} and {b1, b2, b3,..., b12}. As shown in Figure 1(a), curve a has 10 feature points and curve b has 12 feature points.

Step 2: Before blending the two curves, the two curves must have the same number of feature points. First, substitute the coordinate values of the feature points into formula (5) to calculate the centroid coordinates of curve a and curve b based on the centroid and overlap, as shown in Figure 1(b). Second, curve b is the reference curve of curve a. And use the centroid as the origin to let the ray pass through the feature points of curve a. Finally, take the 12 intersection points (red points of curve a) and the ray as the new feature points of curve a, namely {a 1’, a 2’, a 3’,..., a 12’}.

where \(\overline{{x }_{c}}\) and \(\overline{{y }_{c}}\) are the centroid coordinates, n is the number of feature points, xi and yi are the feature point coordinates.

Step 3: When the base curve and the reference curve have the same number of feature points, the new curve can be constructed using any formula in equations (1) to (4). For example, in the xy coordinate system, the feature point coordinates of the base curve, the new feature point coordinates of the reference curve, and the weight ratios of the five feature point sets (i.e., 3:1, 2:1, 1:1, 1:2, 1:3) are substituted into formula (1), i.e., plan 1, plan 2, plan 3, plan 4, and plan 5, and five curves can be constructed, as shown in Figure 1(c).

DeepSeek

DeepSeek is a high-performance large language model built with an advanced distributed training architecture69. In KE, DeepSeek can automatically generate high-fidelity affective emotional imagery adjectives based on users’ written prompts, providing scalable corpora for product emotion computing and significantly enhancing the consistency of intelligent assistants in dialogue and task processing. Recently, with its outstanding capabilities in large language models, DeepSeek has become one of the rapidly developing important applications70. DeepSeek’s continued progress is driven by continuous optimization, adaptation to various application scenarios, and frequent updates, such as the release of DeepSeek-v3 in October 2024.

Similar to text-to-image generation tools, prompt engineering is crucial to DeepSeek. On the Internet, many researchers and enthusiasts are actively engaged in prompt engineering practice71. They focus on discussing and sharing effective techniques for accurately using DeepSeek and exploring its functional limits. The key elements of DeepSeek prompt words include context, instructions, output indicators, and input data. For example, “I am conceiving an industrial robot of a Chinese enterprise brand (context). Please give the design concept (description), within 200 adjectives (output indicators), covering functions, appearance, and materials (input data).” At the same time, there are practical tips, such as “Please analyze as an expert (role)”, “Please imitate the style of (person or brand)”, and “Organize the following information in the specified format”.

In the field of natural language processing, DeepSeek-v3 and GPT-4.1 are two highly representative advanced language models72. GPT originated in the United States, and DeepSeek originated in China. The following is an in-depth analysis of the two from multiple key dimensions. The similarities and differences between the two are shown in Table 1. DeepSeek-v3 and GPT-4.1 are powerful multimodal language models, each with its own advantages73. In the field of industrial design, DeepSeek has great potential and is suitable for brainstorming, conceptual design, and competitive product analysis. DeepSeek can generate the prompts required for image generation artificial intelligence74, so designers must master prompt engineering. Moreover, DeepSeek originated in China and excels at understanding descriptive vocabulary at various levels of abstraction, thanks to its excellent language processing capabilities. It aligns with the needs of Chinese companies, which makes it closely connected to KE theory and image generation tools such as Midjourney and Stable Diffusion.

KE

KE is the systematic way of turning consumers’ feelings and emotional needs into concrete product features and functions75. Within this framework, phone interviews with business users play six key roles. First, they act like an emotional radar, quickly and cheaply cutting through company layers to capture what decision-makers really feel about product performance and brand image. Second, they serve as a semantic anchor, translating vague feelings into clear, countable words through semi-structured calls, giving the first raw data for later semantic-difference matrices. Third, they work as a dimension probe: by transcribing, coding, and counting words, we uncover hidden emotional angles and enlarge the space for principal-component analysis76. Fourth, they are a weight checker: short follow-up calls test how strongly each keyword resonates, correcting any mismatch between what people say and what the numbers say. Fifth, they act as an iteration trigger, feeding fresh market trends, competitor notes, and usage scenes into a live update loop that keeps generative models retraining. Sixth, they build a trust bridge, using frequent, low-friction contact to keep key users engaged so later prototypes and data flow run smoothly77. Phone interviews are the doorway to measuring emotions in KE and the live tuning knob that runs through every stage of user-centred innovation.

The standard five-step workflow is as follows. Step 1: Zero in on product pain points and core decision-makers, design a semi-structured, scenario-based guide, and run small-sample, in-depth interviews to catch spoken feelings in real time. Step 2: Transcribe the calls, build a multidimensional Kansei rating matrix using the semantic-differential method, code the raw words, count frequencies, and check reliability. Step 3: Use principal-component analysis to pull out the hidden kansei dimensions, pick statistically strong and highly distinctive keywords across three levels of emotional needs, and link them to quantifiable design variables like colour, material, and form78. Step 4: Break down key elements with morphological grammar, compute how much each variable shapes the intended image, and let large models quickly output prototypes that match the target feelings79. Step 5: Validate the prototypes’ emotional impact with follow-up calls, fold user feedback and market data into a dynamic update loop for continuous model improvement. In this way, phone interviews transform abstract feelings into actionable design parameters, establishing a method that is both theoretically sound and practically workable for user-centered industrial innovation80. At the same time, the resulting labels and weight maps also supply high-quality, scalable prompts for AIGC-driven design.

FAHP

In 1987, Saaty proposed the analytic hierarchy process (AHP). It is a solution to decision problems involving multiple criteria81. Based on the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method and the analytic hierarchy process, scholars proposed the fuzzy analytic hierarchy process, namely FAHP82. This method can effectively address the error problem caused by the traditional AHP method’s susceptibility to individual extreme values and respondent subjectivity83. Currently, FAHP has been applied to decision problems related to product design. The operation steps of FAHP are roughly the same as those of AHP84. The implementation steps are described as follows85.

Step 1: Decompose the decision problem into the target layer, the guidance layer, and the indicator layer. Obtain user needs through questionnaire surveys and on-site interviews, filter and summarize them, and then build a model.

Step 2: Construct a fuzzy judgment matrix. Compare the indicators at the same level pairwise to determine the relative importance. The fuzzy judgment reference is shown in Table 2. Experts score the indicators according to the table and construct the fuzzy judgment matrix Q:

In the formula, rij represents the comparison between factor ri and factor rj, i, j = 1, 2, …, n.

Step 3: Calculate the indicator weight by the summation method and other methods. This method is simple and has high stability. The formula is as follows:

In the formula, Wi is the weight of indicator ri, and n is the order of the matrix.

Step 4: Calculate the consistency ratio (CR). If CR ≤ 0.1, the judgment matrix is considered to have good consistency. The calculation formula is as follows:

CR calculation formula is as follows:

The random index (RI) values corresponding to matrices of different orders can be obtained by looking up Table 3.

Step 5: Weight ranking of demand indicators. Through comprehensive weight calculation, determine the weight ranking of each indicator relative to the target layer, and perform a consistency check again.

Implementation process of the design method based on KE and AIGC technology

This study aimed to develop a morphological optimization design method for HDIRs based on KE, CBA, and AIGC technology and verify its effectiveness. This method optimizes the investigation, artificial generation, Curve blending, and visual output stages of the HDIRs design process. The complete implementation steps of the proposed design method are as follows.

Design and investigation stage

Step 1: Use the channel of telephone interviews with enterprise users to widely collect users’ adjective descriptions of products to form a perceptual vocabulary collection. Subsequently, the vocabulary was screened and analyzed to eliminate uncommon and difficult adjectives. The vocabulary structure was optimized by merging, splitting, and reorganizing to ensure that the vocabulary was concise and efficient. This structure enhances the accuracy and practicality of the vocabulary database, providing reliable language tool support for perceptual cognition research. First, through the traditional method of perceptual engineering, the emotional imagery adjectives of the HDIRs’ form were collected by enterprise telephone interviews. The user’s perceptual needs for the HDIRs form were identified, and then DeepSeek was used to generate the emotional imagery adjectives of the HDIRs form. Specifically, the latest version of DeepSeek-v3 was adopted to generate a set of emotional imagery adjectives suitable for describing the form of the target product. To obtain objective and emotional imagery adjectives when querying DeepSeek, practical tips and tricks (from the DeepSeek official website) can be used. For example, use Tip 1: Assign an industrial role to DeepSeek. Tip 2: Provide background information for the question. Tip 3: Ask questions precisely. Tip 4: Advance the question systematically. Tip 5: Guide DeepSeek to a reasonable and logical response. Tip 6: Provide feedback to DeepSeek. This step will generate many emotional imagery adjectives that describe the target product.

Step 2: Select typical adjectives from the emotional imagery adjectives generated in step 1. In view of the uncertainty of AI text generation, designers and consumers are invited to participate in the selection of typical emotional imagery adjectives. Enhance the objectivity and rigor of the screening, and finally determine the top-ranked adjectives as typical emotional imagery adjectives. The other subphrases generated usually cover the theme (target product), background settings, rendering effects, image quality, and various control parameters.

AIGC design stage

Step 3: Enter emotional imagery adjectives and prompt sub-phrases in Midjourney. To ensure that the generated form conforms to the typical emotional imagery adjectives, other subphrases must avoid showing image tendency. Regarding the generation of the product database, the “MJ version” in the Midjourney version should be selected. Subsequently, multiple reference prompt words containing the core elements of the product are constructed again through DeepSeek. Combined with the description skills of the general parameters of the product generated by uploading the image-generated text-describe attribute of the basic form of the product. And through systematic parameter optimization experiments, the optimal prompt word structure is finally determined. In Midjourney’s “/imagine” command, enter the typical emotional imagery adjectives followed by the other necessary sub-phrases in sequence to generate a set of target product forms corresponding to the typical emotional imagery adjectives.

Step 4: Use the images generated by Midjourney to establish a reference database for the target product. The reference database consists of first-generation images and second-generation images. Specifically, the first use of the “/imagine” command to generate the first-generation database of the target product produces four images. Based on each first-generation order, running the “/imagine” command again will produce four additional images. There are slight differences between them, and they are considered second-generation databases. Additionally, the image tendency of the second-generation form can be adjusted via the “Remix” mode and the “-chaos” parameter.

Curve mixing design stage

Step 5: Update the basic image. The target image is established based on the typical emotional imagery adjectives of the target product, and serves as the reference standard for updating the basic image. Subsequently, based on the set target image, select the corresponding image from the database as the reference image. Finally, the element curves of the basic image and the reference image are drawn using cubic Bezier curves, and the two form curves are normalized according to the overall width or height of the shape.

Step 6: Invite experts to use morphological analysis to deconstruct the product’s appearance, allowing several design features to be decomposed. The basic image and the reference image are decomposed into a combination of various element curves. The computer-aided design tool Rhino is used to display the number of feature points and coordinate values of each element curve. Subsequently, the coordinate values of the feature points are substituted into formula (5) to calculate the centroid of each form element curve.

Step 7: Generate Blended Curves. First, overlay the paired morphological element curves from the basic and reference images, aligning them by their centroids. Then, use the CBA and Ray-firing method to blend the curves. By adjusting the feature point weights (w1, w2) as defined in formulas (1) through (4), multiple new morphological element curves can be generated from each initial pair.

Step 8: Use equation (5) to calculate the centroid coordinates of the newly generated curves. Subsequently, using the reference form of the centroid as the reference, the newly generated element curves are combined to form multiple new complete forms. During the combination process, a morphology should be composed of element curves created with the same mixing ratio. Finally, several complete morphological curves are combined as new plans for the target product.

Visual output and verification stage

Step 9: Use the image generation Stable Diffusion graph generation module and controlnet to control the conversion of the morphological curve of the new plans into a three-dimensional rendering.

Step 10: Evaluate the new plans through expert discussions based on FAHP and consumer perception questionnaires. The purpose of the evaluation is to verify whether the new plans are consistent with the image of the reference form (i.e., the target image) and to determine which new plan best matches the target image. Additionally, it is essential to verify the consistency and statistical significance of the two evaluation results.

Methodological framework

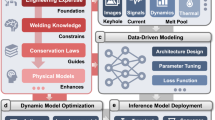

Based on the design method and implementation procedures outlined in Section "Implementation process of the design method based on KE and AIGC technology", the research framework is shown in Figure 2. The implementation process of the generative artificial intelligence-based method for the morphology optimization design of HDIRs is described. The specific implementation process is as follows.

Process and results

Collection of emotional imagery adjectives

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Beijing University of Technology (5 September 2024). First, we collected the emotional imagery adjectives of HDIRs morphology through traditional perceptual engineering enterprise user telephone interviews. Then, we used DeepSeek to generate the emotional imagery adjectives of HDIRs morphology.

Collect emotional imagery adjectives through telephone interviews with enterprise users

The study focused on 210 kg welding HDIRs in automotive spot-welding applications, and five enterprise users of the robots for telephone interviews. Because automotive spot welding is a core step in body manufacturing, high-payload robots are critical equipment on the production line; their bulky structures and large footprints directly affect production efficiency and cost. Enterprise users are highly sensitive to return on investment and brand image, so the demand for morphological optimization is urgent and its value is significant. Therefore, the researchers deeply explore the users’ perceptual cognition and emotional expectations toward the product. After the interview, the rich information collected was deeply analyzed to fully absorb the valuable suggestions put forward by the users. Based on this, the scientific and rigorous screening method was used to closely focus on the three levels of emotional needs of ordinary users. After repeated weighing and careful screening from nearly 80 groups of candidate emotional imagery adjectives, 8 most representative and key emotional imagery adjectives were finally selected. They are “Dry”, “Simple”, “Manageable”, “Stable”, “Safe”, “Delicate”, "Non-slip", and “Secure”. These adjectives accurately reflect the emotional expectations of users in different dimensions, and provide strong theoretical support and direction guidance for subsequent product design and optimization work.

Generate emotional imagery adjectives through DeepSeek

In order to accurately obtain emotional imagery adjectives that match the target product form, the latest version of the DeepSeek model as of April 2025 was used. Section 3.1.3 provides a systematic explanation of the core essence and practical technology of DeepSeek prompt engineering, offering a theoretical basis and operational guidelines for the rational use of the model. On this basis, this section innovatively adopts a segmented questioning strategy to ensure the effectiveness and accuracy of the generated emotional imagery adjectives, as shown in Figure 3. During the implementation process, the researchers initiated a total of 4 rounds of dialogues, and the detailed dialogue content is shown in Table 4.

In the first stage of dialogue, the researchers set a specific situation and set DeepSeek as a senior industrial product designer. As a result, DeepSeek has laid a solid professional foundation for subsequent discussions with its deep knowledge reserves in multiple professional fields such as user-centered design, manufacturing process, material selection, prototype design, and innovative product marketization. This solid professional foun-dation can strengthen the discussion about the emotional imagery adjectives. In dialogue 2, the researchers focused on a 210 kg welding HDIR. DeepSeek was asked to disassemble the detachable structure from the overall appearance to the specific components. It was clearly pointed out that these structures can be described by per-ceptual emotional imagery adjectives. DeepSeek’s response covered seven key aspects, providing a clear framework for the subsequent classification and screening of adjectives. Dialogue 3 went further and asked DeepSeek to recommend 35 emotional imagery adjectives that can accurately describe the side shape of a heavy industrial robot to enrich the adjective library. In Dialogue 4, based on the seven key aspects determined in Dialogue 2, the researchers asked DeepSeek to scientifically classify the 35 emotional imagery adjectives. In order to achieve accurate matching of adjectives and product structures, a more targeted and practical language tool is provided for subsequent product design and optimization.

Screening of emotional imagery adjectives

Given the uncertainty of AI text generation and telephone interview questionnaires, this study invited 9 subjects, including six industrial design experts and three consumers (four males and five females, aged between 35 and 48 years old). The 4 experts first examined the 43 emotional imagery adjectives (35 from DeepSeek and 8 from KE-based interview) to remove similar adjectives. The 9 subjects scored the emotional imagery adjectives. The subjects scored each adjective based on the evaluation criteria of "whether the emotional imagery adjectives is suitable for evaluating the side morphology of heavy-duty industrial robots", with a score range of 0 to 1. Finally, the top 4 adjectives with higher scores were selected as typical emotional imagery adjectives. They are impressive, streamlined, stable and powerful, as shown in Table 5.

Midjourney generates product image database

As described in Section 3.2.2, the prompt method based on the Midjourney platform is described. The study uses the "/imagine" command to construct a prompt word template. The template consists of multiple structured elements, including dimensions such as subject description, morphological characteristics, design style, environmental settings, rendering parameters, and quality control. In response to the design requirements of the side morphology of HDIRs, the researchers once again used DeepSeek to construct multiple reference prompt words including core elements such as "210kg heavy-duty industrial robot", "Side profile of industrial robot", "Welding industrial robot", "Impressive/Streamlined/Stable/Powerful", "white clean background", "product design sketch", “complex details”, “left view”, "metallic yellow texture", and “dynamic” Multiple reference prompt words of core elements such as “state illumination”, “3D”, “C4D”, “4K”, "-- v 6.1", "-- ar 1:1", etc. Combined with the basic morphology of Figure 7, the description skills of the general parameters of the product generated by uploading the image to generate text describe attributes. Through systematic parameter optimization experiments, the optimal prompt word structure was finally determined to be: "a/an [Emotional Imagery Adjectives] the 210 kg heavy-duty welding industrial robot arm is placed in isolation in front of a white background. The left view effect drawing of the industrial product design shows a clean appearance with complex details highlighting the mechanical structure. The metallic yellow texture makes it suitable for product marketing materials or advertisements. Dynamic lighting, Turei Hattori style, 3D, 4 K, C4D -- v 6.1 -- ar 1:1".

In the specific implementation process, this study selected four typical emotional imagery adjectives (Impressive/Streamlined/Stable/Powerful) from Section 4.1.3 as key variable parameters. All four initial schemes were selected to generate variants and ensure diversity in the results. By controlling the variable method, other prompt word elements were kept unchanged, and only the emotional imagery adjectives subitems were replaced for comparative experiments. At the operation level of the Midjourney platform, four initial morphological schemes can be generated after each emotional imagery adjective is input. The platform’s builtin “variation” function can be further expanded to generate four derivative schemes. As shown in Figure 4, users can implement iterative optimization of schemes through interface interaction. Click the function button in the lower right corner of the generated result to obtain new schemes of the same type. Select the "V" option with a specific number to generate similar schemes that evolve details while maintaining the core features (Fig. 5).

Based on the above method, the study established a systematic industrial robot morphological image database. In the first round of generation, 8 initial schemes were generated for each of the four emotional imagery adjectives (a total of 32). On this basis, four variants were generated for each initial scheme, and finally a reference database containing 160 schemes (32 original schemes + 128 derivative schemes) was constructed. As shown in Figure 6, taking the “streamline” image as an example, the eight basic solutions generated in the first round are numbered Int_f1 to Int_f8 (i.e., the first-generation morphological solutions). After selecting Int_f1 for variant generation, four optimized solutions with differences in morphological details, Int_f1_1 to Int_f1_4, can be obtained (i.e., the second-generation morphological solutions). This multi-level, iterative generation method effectively expands the diversity and selectivity of design solutions.

Clarify the basic form, target image and reference form

In order to clearly explain the proposed design method, this study uses a 210 kg Chinese-made welding HDIR that needs to optimize its appearance as the basic model. As shown in Figure 6, this model was selected as the basic form. Its forearm is bloated, the curves of the upper and lower arms do not match, and the overall uniformity is poor. The study aims to improve the overall consistency of its appearance through design improvements. The study selected the top two typical emotional imagery adjectives “Impressive” and “Streamlined” as the target image of the basic form. Further clarify the design goal: on the basis of retaining the core product gene characteristics of the basic form, create a new form that matches the specified target image.

Since the target imagery for the base form was defined as “Impressive” and “Streamlined,” the visual characteristics of the reference forms were also expected to exhibit qualities of being both “Impressive” and “Streamlined.” Based on this, six experts (two male, four female) were invited to participate in this study. As shown in Table 6, through open discussions, typical forms representing “Impressive” and “Streamlined” were selected from a reference database of 80 schemes (16 first-generation form schemes and 64 second-generation form schemes). Specifically, the six experts were divided into two groups. Each group independently selected four images from the first-generation database that exhibited both “Impressive” and “Streamlined” characteristics, resulting in a total of five images (with three duplicate selections). The first-phase selection was based on three explicit criteria: Semantic Match (50%), Form Integrity & Feasibility (structural coherence and engineering plausibility, 30%), and Innovation and Aesthetic Value (novelty in form language and silhouette, transcending existing designs, 20%). Subsequently, based on the first-round selection results from the two groups, all experts jointly evaluated 20 corresponding second-generation form schemes generated from the five selected images, ultimately identifying representative forms. Through this structured process, two typical forms that jointly represented “Impressive” and “Streamlined” were selected. This structured approach guided the six experts in using a weighted evaluation matrix based on four core criteria: Brand Identity & Aesthetics (30%), Kansei Consistency (30%), Engineering Coherence (25%), and Manufacturing & Cost Feasibility (15%). Each refined scheme was scored on a 1–5 Likert scale against these criteria, and the final reference forms were objectively selected based on the highest total weighted score. This rigorous two-phase screening of first- and second-generation schemes ensured that only the most standard, relevant, and representative conceptual forms were advanced to the subsequent variant generation stage. Finally, after collective deliberation, the experts unanimously selected Imp_f1_1 and Str_f1_4 (see Figure 5) as the typical representative forms of the target imagery, to be used as reference forms for subsequent design.

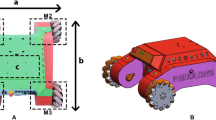

In order to fuse the basic morphology with the reference morphology, we use three consecutive Bezier curves to draw the morphological element curves, covering the Main Body, Upper Arm, Lower Arm, Base, End Effector, and Joints. This study uses Rhino to draw the morphological element curves. In addition, in order to ensure the effectiveness and usability of the morphological element curves in morphological fusion, we normalize the overall width, as shown in Figure 7.

Decomposition of shape element curves

Six experts were invited again to use the shape analysis method to deconstruct and analyze the appearance of the HDIRs. Its appearance was subdivided into six key design features: covering the main body, upper arm, lower arm, base, end effector and joint components. In the specific operation, the basic form, reference form 1 and reference form 2 were further divided. The five shape element curves under each form were extracted as shown in Figure 8. After completing the decomposition operation, with the help of the curve analysis function of the Rhino software, the number of feature points contained in each shape element curve and its corresponding coordinate values were accurately obtained. Next, these coordinate values were substituted into formula (5) to calculate the centroid position of each shape element curve.

Curve blending

In order to achieve the fusion of the morphological element curves between the basic shape and the reference shape, the study adopted a curve blending algorithm combined with a ray emission method. Taking the blending of the basic shape and the reference shape 1 or 2 as an example, Figure 9 reference form 1 shows the blending effect of curves a_0 and a’_0. The fusion steps are as follows: First, the position alignment is completed according to the centroid of curves a_0 and a’_0. Then, curve a_0 is selected as the reference curve and curve a’_0 is selected as the target curve. Starting from the centroid, 80 rays are emitted along the 80 feature points of curve a_0. Next, the 80 intersection points of curve a’_0 and the rays are captured and used as the new feature points of curve a’_0. Using formula (1), the feature point sets of the two curves are combined with different weights (3:1, 2:1, 1:1, 1:2, 1:3) to generate 5 new morphological curves, named a’_1 to a’_5 in sequence. The coordinates of the feature points of these 5 new curves are further substituted into formula (5) to calculate the centroid position of each curve. Although the newly generated curves take into account the morphological features of the basic shape and the reference form, some curves are not smooth. This may be because the new curves do not inherit enough feature points or lose some important feature points, which requires designers to repair and smooth them. Among the newly generated curves in either form 1 or 2, approximately 16% (8 curves) required manual correction due to insufficient smoothness. These have been marked with * in the table. This judgment is based on the dual criteria of visually detecting obvious discontinuities and the maximum deviation exceeding the 0.5 mm threshold during quantitative checks. This necessary manual step is not an algorithmic defect but a crucial part of our AI hybrid workflow to ensure that the final aesthetic surface achieves the highest quality. Through such mixed operations, the study derived 25 new curves in each morphological element, providing morphological materials for subsequent design.

Morphological curve combination

The morphological element curves generated by the basic shape and the reference morphology are combined into 10 new morphologies based on the centroid of the reference morphology, as shown in Figure 10. Based on the centroids of the 6 morphological element curves (i.e., from C0 to C6) of reference morphologies 1 and 2, 5 groups of morphological element curves are combined into 10 plans, namely, plan_1- plan_10. Taking plan_1 as an example, it includes curves a’_1, b’_1, c’_1, d’_1, e’_1 and f’_1.

3D-styled visualizations conversion

In order to present the design scheme more quickly and realistically, Stable Diffusion and controlnet are used to control the generation of 10 schemes’ 2D line drawings into 3D-styled visualizations. As shown in Figure 11, the visualizations of the ten schemes present realistic visual effects with a high degree of restoration. In addition, the image generation process needs to pay close attention to the effect, flexibly adjust the redrawing amplitude, control weight and other parameters, and continuously optimize the prompt words. Through repeated trials and iterations, the quality of the generated image is gradually improved, and finally a 3D-styled visualizations that meets the expected specific contour line is obtained.

Evaluation of plans

Two evaluation methods were used for the evaluation of the 10 Plans (Figure 11): expert evaluation based on FAHP (Evaluation 1) and consumer perception evaluation (Evaluation 2). In Evaluation 1, 6 experts were invited to evaluate the 10 morphological Plans generated by morphological fusion using FAHP. The evaluation criteria were "How impressive/streamlined is Plan_1 compared with Plan_2? ". The corresponding pairwise comparison matrices of Evaluation 1 are shown in Table 7. For the impressive Plan_1-5, ranked from the highest to the lowest in terms of the comprehensive weight, they are Plan_5, Plan_4, Plan_3, Plan_2, and Plan_1; for the streamlined Plan_6-10, ranked from the highest to the lowest in terms of the comprehensive weight, they are Plan_9, Plan_8, Plan_7, Plan_6, and Plan_10. The results of the first assessment show that the most ideal solutions are Plan_5 and Plan_9, and the C.R. values for both assessments are less than 0.1, indicating that the assessment results are acceptable.

In evaluation 2, 5 enterprise users who participated in the KE-based interview and 40 relevant colleagues were invited to conduct telephone interviews to evaluate the 10 so-lutions based on the standard of “To what extent does this plan represent your emotional feelings about the side profile of a 210 kg impressive/streamlined heavy-duty welding industrial robot? ” The score ranged from 0 to 1. A total of 43 valid data sets were collected, including 35 males and 8 females, aged between 28 and 55 years old. After statistical analysis, Cronbach’s α coefficient exceeded 0.8, indicating that the results were acceptable. The results are listed in Table 8. The experts and enterprise users have the same ranking for the impressive Plan_1-5; and they also have the same ranking for the streamlined Plan_ 6–10. In addition, the Pearson correlation coefficient was used to test the correlation between the two groups of evaluation results. The analysis showed that the correlation coefficient exceeded 0.9 and the p value was less than 0.01, indicating that there was a significant and statistically robust correlation between the two evaluation results. In the two evaluations, the ranking of the schemes remained consistent and was proportional to the curve fusion weight value of the reference form. This means that the higher the blending weight value of the reference curve, the more the scheme can be consistent with the image target feeling of the reference form.

Comprehensive practice of shape design of 210 kg welding HDIRs

In the comprehensive practice of conceptual morphological design for a 210 kg welding HDIR, an in-depth analysis was conducted on the streamlined scheme, ultimately selecting the genetic curve from the Plan_9 scheme with the highest weight proportion as a key reference for product conceptual morphological optimization. Based on this, the designers optimized the robot’s morphology by incorporating engineering practice elements, ensuring a perfect integration of form and function. The final product conceptual morphological design rendering and its conceptual application scenario renderings are shown in Fig. 12, showcasing the robot’s smooth lines and robust structure.

Discussion

Summary and interpretation of results

Integrating KE, CBA, and AIGC, this study conducted an in-depth optimization of the morphology of HDIRs, successfully preserving the visual identity inherent in existing product curves. Furthermore, the proposed morphological optimization design method offers designers a novel and streamlined workflow experience.

Moving beyond the limitations of traditional design approaches, which often rely heavily on designers’ subjective judgment86, this research employed a ray emission method to blend existing product curves with functional requirement curves, generating a variety of innovative design schemes. This methodology enables the simultaneous consideration of product curve genetics and the precise matching of functional demands, thereby producing morphological solutions that integrate brand identity with practicality. This innovative design approach effectively resolves the traditional conflict between heritage, requirements, and utility. It provides new perspectives and methodologies for the field of HDIRs design, promoting the comprehensive advancement of design philosophy.

By leveraging advanced AIGC technologies such as Deepseek-v3, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion, significant efficiency improvements were achieved within the morphological design process of the 210 kg welding HDIRs. Compared to traditional design processes, the design cycle can be shortened while the number of design iterations increases substantially88, These powerful AI tools rapidly generate a large number of creative morphological design proposals for HDIRs89. This facilitates the exploration of a wider range of design possibilities within a shorter timeframe, establishing a more efficient paradigm for the morphological optimization of HDIRs.

Practical implications

The research integrates the KE-CBA fusion strategy and the ray shooting method into the morphological optimization design process of HDIRs and applies it to a 210 kg welding HDIR. This method has a simple process and has the potential to be implemented in small and medium-sized industrial robot enterprises. However, its effective execution still relies on professional AIGC tools, modeling skills, and corresponding design knowledge. During the promotion process, enterprises need to recognize potential implementation obstacles, including the compliance requirements for using AIGC tools and the training requirements for new skills such as prompt engineering. Additionally, the industry association can incorporate this method into the design guidelines for HDIRs, promoting and publicizing it through case libraries and training materials, thereby reducing iteration costs and shortening the market launch cycle of domestic HDIRs models, providing a replicable design path for batch customization and brand differentiation.

Limitations and further research needs

This study has yielded preliminary findings while acknowledging several limitations that must be addressed in subsequent research. First, the current investigation was confined to 210 kg welding HDIRs, whose working load and motion trajectories are specific. While this single case provides a critical preliminary validation, we acknowledge that the generalizability of the approach requires further verification across a broader spectrum of robotic types. Future research should extend to applications with substantially different performance requirements, including palletizing and ultra-heavy-load (≥ 3 tons) scenarios, to systematically evaluate the framework’s adaptability and robustness under varied working conditions. Second, the AIGC training dataset exhibited deficiencies in specialized industrial image modeling, lacking comprehensive representation of complex and diverse structural features inherent in real industrial environments. This shortcoming may introduce discrepancies between generated solutions and engineering practicalities, potentially compromising the precision and reliability of design outcomes. Consequently, developing a high-quality, specialized industrial image dataset represents a critical objective for future work. Last, this research currently mainly focuses on the conceptual morphological design stage and has not fully incorporated production and manufacturing constraints such as casting processes. It is planned to conduct manufacturing verification in subsequent work. Furthermore, AIGC-generated structures frequently conflict with manufacturability imperatives. The crucial future direction involves deeply integrating AIGC structural optimization with mass production guidelines, establishing a design optimization workflow that incorporates manufacturing process constraints. This approach will ensure innovative designs achieve morphological excellence and industrial feasibility, thereby facilitating effective translation from theoretical design to engineering application.

Conclusions

This study took a 210 kg welding HDIR as its specific example, proposing and validating a morphological optimization design method based on KE, CBA, and AIGC. It assists design teams in more effectively understanding and applying CBA and AIGC technologies, while simultaneously promoting the inheritance and innovation of corporate product optimization design workflows. The primary value of this research lies in providing a systematic procedural framework and structural reference for the morphological optimization design of HDIRs. It offers methodological support for enterprises in achieving product family design and sustainable iteration. Future research should deepen the systematic application of corporate curve-based design genes in HDIRs, further exploring specific implementation strategies for the serialization of enterprise product design elements and the construction of brand gene identity. This will provide morphological design support for enhancing the brand recognition of industrial robotics enterprises.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, F. Review of the Application Status and Development Trend of Industrial Robots. SHS Web Conf. 144, 03005 (2022).

Srinivasulu, R., Rao, Y. S., Vempati, S. & Haribabu, U. Designing Arc Welding Application Using Yaskawa Robot. Int. J. Mech. Eng. 7(2), 2493–2510 (2022).

Guo, Q. & Su, Z. The Application of Industrial Robot and the High-Quality Development of Manufacturing Industry: From a Sustainability Perspective. Sustainability 15, 12621 (2023).

Sun, W. Mechanism design and performance guarantee of heavy-duty industrial robot (Shantou University, 2021).

Khan, A. U., Huang, L., Onstein, E. & Liu, Y. Overview of Emerging Technologies for Improving the Performance of Heavy-Duty Construction Machines. IEEE Access 10, 103315–103336 (2022).

Burnap, A., Hauser, J. R. & Timoshenko, A. Product aesthetic design: A machine learning augmentation. Mark. Sci. 42(6), 1029–1056 (2023).

Koch, C. The Future of Industrial Design and Its Role in Industry 4.0 phd (Swinburne University of Technology: Melbourne, 2022).

Wu, J., Cai, Y., Sun, T., Ma, K. & Lu, C. Integrating AIGC with Design: Dependence, Application, and Evolution - a Systematic Literature Review. J. Eng. Des. 36(5–6), 758–796 (2025).

Yue, Q. & Zhang, C. K. Survey on Applications of AIGC in Multimodal Scenarios. J. Front. Comput. Sci. Technol, 19, 79–96 (2025).

Jin, J. et al. Empowering Design Innovation Using AI-Generated Content. J. Eng. Des. 36(1), 1–18 (2025).

Fu, R. J. C. Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and Robotics: The Core of Tomorrow’s Industries. Artif. Intell. Mach. Learn. Robot. Bus. 1, 6–9 (2025).

Kuka, A.G. KR FORTEC ultra: A 500 kg-class heavy-duty robot with triple stiffness and precision. KUKA White Paper, May (2025).

Chen et al. Leapfrogging stiffness and accuracy of heavy-duty robots: Practice in Midea Blue-Orange Lab[C]//The 1st National Heavy-Duty Robot Forum. Foshan, China, Mar. (2025).

Chen, L. Structural Design and Dynamic Analysis of Heavy Duty Industrial Robot Based on High Torque Drive (Yantai University, 2023).

Sun, W., Zhang, Y.H., Zhao, Y.J. Research status of heavy-duty industrial robots. J.Shantou.Univers. 35, 3–15+2. (2020).

Yin, S. Q. Design and mechanical characteristics of high speed and heavy load stacking robot (China University of Mining and Technology, 2022).

Chen, C.Z., Xiao, Z.M., Wu, W.Q., Qin, G.X., Ren, Z.Y., Wang, Y.T. Design and analysis of a long arm heavy duty fully automatic loading robot. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Robotics, Artificial Intelligence and Intelligent Control (RAIIC 2023). Mianyang, China, 11–13, pp. 115–120. (2023).

Wei, Y. J., Qiu, G. L., Ding, G. H., Yang, L. & Liu, H. A structural optimization design method for heavy-duty palletizing robot. J. eng. design. 27, 332–339 (2020).

Wu, G. P. Mechanism design and anlysis of heavy-duty blank transfer robot (Harbin Institute of Technology: Harbin, 2020).

Ko, C.M.; Chung, G.J.; Kim, D.H. Designing of heavy duty handling robot (HEDURI-I robot design). International Conference on Mechatronics. IEEE, pp. 1–6. (2009).

Analysis and design of heavy duty handling robot. Conference on Robotics, Automation and Mechatronics. IEEE, pp. 774–778. (2008).

Shang, X.Y., Guo, Y., Dai, X.B., Zhang, Y.W., Liu, Y., Gao, Y., Luo, Y. Wheel design and motion analysis of a heavy-duty material handling robot. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Robotics, Intelligent Control and Artificial Intelligence (RICAI 2023). Hangzhou, China, 1–2 December, pp. 131–134. (2023).

Miao, D. Y. Structure design and dynamic performance analysis and optimization of heavy-load transfer robot (Hefei University of Technology, 2014).

Xu, F. Q. et al. A Research on Modeling Design of Medical Assistant Robot Based on Kansei Engineering. J. Anhui Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci.) 40(04), 28–32 (2023).

Zhang, S. T., Sun, J. N. & Zhou, A. M. Intelligent Design of Product Image Modeling (Tsinghua University Press, 2022).

Yang, X., Zhang, N. & Lv, J. Design of Chinese traditional Jiaoyi (Folding chair) based on Kansei Engineering and CNN-GRU-attention. Front. Neurosci 19, 1591410 (2023).

Coronado, E., Venture, G. & Yamanobe, N. Applying Kansei/Affective Engineering Methodologies in the Design of Social and Service Robots: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 13, 1161–1171 (2021).

Liu, J.W., Zhu, Z.J. Product appearance design guide for innovative products based on Kansei engineering. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. Copenhagen, Denmark, 23–28. pp. 588–599. (2023).

Wang, Z. Y., Dai, M. Z., Sun, X. & Zhou, M. Y. A higher satisfaction product customization method for different customer groups. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 36571–36601 (2024).

Fu, R. & Zhang, Y. Modeling Design of Six-Freedom-Degree Collaboration Robot. In HCI International 2018 – Posters’ Extended Abstracts Vol. 852 (ed. Stephanidis, C.) 448–454 (Springer International Publishing, 2018).

Zafar, M. H., Langås, E. F. & Sanfilippo, F. Exploring the Synergies between Collaborative Robotics, Digital Twins, Augmentation, and Industry 5.0 for Smart Manufacturing: A State-of-the-Art Review. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 89, 102769 (2024).

Zhou, X. Research on design elements of industrial robot based on kansei image (Anhui University of Technology, 2018).

Chen, L. & Xiao, W. Q. Design of industrial robot based on Kansei enginering. J. Anhui. Univers. Technol. 34, 53–55 (2017).

Wang, X. J. & Xiao, W. Q. Research on modeling design of industrial robot based on perceptual image. Mech. Des. 33, 117–120 (2016).

Wang, X. J. & Zhang, L. A. Modeling design research of 7-DOFs industrial robot based on perceptual demand. Mech. Des. 34, 114–118 (2017).

Wu, Y., Zhou, D. T., Cheng, H. L. & Yuan, X. F. A new configuration method for glass substrate transfer robot modules based on Kansei engineering. Appl. Sci. 12, 10091 (2022).

Cheng, H. L. Research on configuration of industrial robot morphology module based on perceptual image (Wuhan University of Technology, 2021).

Xiao, W.Q., Wang, X.J., Lou, M., Chen, L., Li, W.B., Jin, X. Modeling design method for intelligent industrial robot based on perceptual image. For. Chem. Rev., 2242–2264. (2022).

Xiao, W. Q., Cheng, J. X., Zhou, X. & Wang, X. J. Research on perceptual image space of industrial robot modeling design based on eye movement experiment. Mech. Des. 34, 124–128 (2017).

Xiao, W. & Cheng, J. Perceptual Design Method for Smart Industrial Robots Based on Virtual Reality and Synchronous Quantitative Physiological Signals. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 16, 155014772091764 (2020).

Cheng, J.X., Xiao, W.Q. Wang X.J.,Ye, J.N., Le, X. Study on the perceptual intention space construction model of industrial robots based on ‘user+expert’. In Proceedings of the Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics, (EPCE 2016), Toronto, ON, Canada, 21. pp. 280–289. (2016).

Zhang, X. X., Li, Y. Y., Pei, H. N. & Ding, M. Research on chaos of product color image system driven by brand image. Multimed. Tools Appl. 82, 24425–24444 (2023).

Benaissa, B. & Kobayashi, M. The Consumers’ Response to Product Design: A Narrative Review. Ergonomics 66, 791–820 (2023).

Shigemoto, Y. Beyond IDEO’s design thinking: Combining KJ method and Kansei Engineering for the creation of creativity. In Proceedings of the AHFE 2021 Virtual Conferences on Creativity, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, and Human Factors in Communication of Design, Online, 25–29, pp.16–23. (2021).

Cao, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Dai, Y.; Yu, P.S.; Sun, L. A Comprehensive Survey of AI-Generated Content (AIGC): A History of Generative AI from GAN to ChatGPT (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Charting the Path of Technology-Integrated Competence in Industrial Design during the Era of Industry 4.0. Sustainability 16, 751 (2024).

Jie, P., Shan, X. & Chung, J. Comparative Analysis of AI Painting Using [Midjourney] and [Stable Diffusion] - A Case Study on Character Drawing. Int. J. Adv. Cult. Technol. 11, 403–408 (2023).

Liu M, Hu Y. Application Potential of Stable Diffusion in Different Stages of Industrial Design. In Degen H, Ntoa S (Eds) Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence in HCI. Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 590–609. (2023).

Chai, C. L. et al. The evolution path and Prospect Outlook of generative artificial intelligence-driven intelligent Product design. Furnit. Interior Des. 31(4), 9–18 (2024).

Lu, P., Hsiao, S.-W., Tang, J. & Wu, F. A Generative-AI-Based Design Methodology for Car Frontal Forms Design. Adv. Eng. Inform. 62, 102835 (2024).

Li, Z. & Hu, H. Mechanisms and pathways of generative artificial intelligence-driven productivity transformation in manufacturing: an empirical analysis of guangdong province. Ind. Eng. J. 28(2), 1–11 (2025).

Peng, Y. N. & Yang, H. Z. Research on the organic integration and application of AIGC and industrial design. Art and Design (Theory) 3, 29–32 (2024).

Zhu, Z., Yu, T., Wang, Y et al. Revolutionizing Design Content with AIGC: User-Centered Challenges, Opportunities, and Workflow Evolution. IEEE Access (2025).

Qi, Y., Wei, P., Wang, Z. & Zhang, J. Exploring the Relationship Between Product Design and User Emotions within Artificial Intelligence Generated Content Environments. Asia-pacific J. Converg. Res. Interchang. 10(6), 561–574 (2024).

Stiny, G. Introduction to Shape and Shape Grammars. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 7, 343–351 (1980).

Wang, C., Zhang, J., Liu, D., Cai, Y. & Gu, Q. An AI-Powered Product Identity Form Design Method Based on Shape Grammar and Kansei Engineering: Integrating Midjourney and Grey-AHP-QFD. Appl. Sci. 14, 7444 (2024).

Kang, X. Biologically Inspired Product Design Combining Kansei Engineering and Association Creative Thinking Method. Adv. Eng. Inform. 62, 102615 (2024).

Cagan, P. J. Capturing a rebel: modeling the Harley-Davidson brand through a motorcycle shape grammar. Res. Eng. Des. 13(3), 139–156 (2002).

Mccormack, J. P., Cagan, J. & Vogel, C. M. Speaking the Buick language: capturing, understanding, and exploring brand identity with shape grammars. Des. Stud. 25(1), 1–29 (2004).

Mccormack, J. P. & Cagan, J. Designing inner hood panels through a shape grammar based framework. Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. 16(4), 273–290 (2002).

Zhu, H. Y. & Gao, Z. Research on the design of BYD automobile derivatives based on morphological Analysis-Shape Grammar. Design 9(2), 5 (2024).

Yuan, H. et al. Product Innovative Design Based on Local Shape Integration. Pack. Eng. 32(20), 30–33 (2011).

Ji, C. N. & Yang, X. N. Bézier Triangle-Based Interpolatory √3 -Subdivision. J. Comput. Aided Des. Comput. Graph. 37(5), 790–796 (2025).

Shi, J., Sun, J. N. & Li, X. Coupling Optimization Design Research of Product Image Prototype Form. Pack. Eng. 40(08), 47–53 (2019).

Chen, S. E. & Parent, R. E. Shape averaging and it’s applications to industrial design. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 9(1), 47–54 (1989).

Sederberg, T. W. & Greenwood, E. A physically based approach to 2-d shape blending. ACM SIGGRAPH Comput. Graph. 26(2), 225–234 (1992).

Hsiao, S. W. & Chuang, J. C. A Reverse Engineering Based Approach for Product Form Design. Des. Stud. 24, 155–171 (2003).

Hsiao, S. W., Lee, C. H., Chen, R. Q. & Lin, C. Y. A Methodology for Brand Feature Establishment Based on the Decomposition and Reconstruction of a Feature Curve. Adv. Eng. Inform. 38, 14–26 (2018).

Guo, D., Yang, D., Zhang, H., et al. DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. arXiv:2501.12948, (2025).

Xiong, L. et al. DeepSeek: Paradigm Shifts and Technical Evolution in Large AI Models. IEEE/CAA J. Automatica Sinica 12(5), 841–858 (2025).

DeepSeek-AI. DeepSeek-V3 Technical Report. arXiv:2412.19437, (2024).

IRJMETS. Beyond ChatGPT: Evaluating the Performance and Capabilities of DeepSeek. International Research Journal of Modern Engineering and Technology & Sciences, 3(3), 1–10. (2025).

Zhang, Y., Li, P., Wang, M. DeepSeek vs. GPT-4: A Technical Comparison and Performance Evaluation. CSDN Technical Report, (2025).

Liu, J., Chen, Y., Tong, F. Comparative Analysis Based on DeepSeek, ChatGPT, and Google Gemini. arXiv:2503.04783, (2025).

Lai, X. et al. Kansei Engineering for the Intelligent Connected Vehicle Functions: An Online and Offline Data Mining Approach. Adv. Eng. Inform. 61, 102467 (2024).

Jiao, Y. & Qu, Q.-X. A Proposal for Kansei Knowledge Extraction Method Based on Natural Language Processing Technology and Online Product Reviews. Comput. Ind. 108, 1–11 (2019).

Jia, D., Jin, J., Geng, Q. & Deng, S. Research on user requirement mining from the perspective of kansei engineering. J. China Soc. Sci. Tech. Inform. 39(3), 308–316 (2020).

Hu, S.M., Li, C.F., Zhang, H. Actual morphing: a physical-based approach for blending two 2d/3d shapes. (2004).

Nagamachi, M. Kansei/Affective Engineering and Its Application to Food Design. In Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics Methods 1–15 (Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2024).

Kansei Engineering in Industrial Design [M]. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, 3, 12. (2023).

Saaty, T. L. Rank generation, preservation, and reversal in the analytic hierarchy decision process. Decis. Sci. 18(2), 157–177 (2010).

Zhu, G. N., Jie, H., Qi, J., Gu, C. C. & Peng, Y. H. An integrated AHP and VIKOR for design concept evaluation based on rough number. Adv. Eng. Inform. 29(3), 408–418 (2015).

Ahmed, F. & Kilic, K. I. A Basic Algorithm for Generating An Individualized Numerical Scale. Expert Syst. Appl. 233, 120915 (2023).

The SPSSAU project. SPSSAU. (Version 25.0) [Online Application Software]. Retrieved from https://www.spssau.com. (2025).

Guo, H. Research on Ecological Design of Intelligent Manhole Covers Based on Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process. Sustainability 16, 5310 (2024).

Jieshi, M., Xiaoming, J., Zheng, L. Analysis of the artistic characteristics of lotus patterns and digital innovative design methods. Frontiers in Art Research (2023).

Xu, Z., Lin, H., Zhou, X, et al. AI-Driven Product Form Innovation: A Case Study of CNC Machine Tool Styling Design[C]//International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction.Springer, Cham, (2025).