Abstract

Carbon quantum dots (CQDs) have emerged as eco-friendly nanomaterials with tunable optical properties and biomedical potential. This study aimed to synthesize and characterize phosphorus-doped CQDs from Saccharomyces cerevisiae β-glucan, providing a green, reproducible production route and assessing their physicochemical and biological properties. β-Glucan extracted from yeast cell wall (YCW) was hydrothermally carbonized at 250 °C to yield fluorescent CQDs. Structural, optical, and compositional analyses were conducted using FTIR, XRD, EDX-MAP, TEM, and DLS. The antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cytotoxic properties were systematically evaluated using standard in vitro assays. The synthesized CQDs exhibited strong π–π* absorption at 201 nm and pH-sensitive blue photoluminescence with a 24% quantum yield, and TEM confirmed core sizes below 10 nm. The CQDs displayed broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, exceeding ciprofloxacin against resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, with MIC and MBC values ranging from 0.93 to 3.75 mg mL⁻¹. They also showed high antioxidant activity under acidic conditions and reduced erythrocyte sedimentation rate from 12 mm h⁻¹ to 1 mm h⁻¹, indicating anti-inflammatory potential. Cell viability remained above 70% at ~ 47 µg mL⁻¹, confirming acceptable biocompatibility. β-Glucan-derived CQDs offer sustainable synthesis, strong optical properties, and multifunctional bioactivity, creating an eco-friendly nanomaterial for antimicrobial, antioxidant, and inflammation-responsive uses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid advancement of nanotechnology has indeed catalyzed the exploration of innovative materials, including quantum dots (QDs), which have emerged as significant candidates for applications in biomedicine, environmental remediation, and optoelectronics. QDs, typically semiconductor nanoparticles ranging from 1 to 10 nanometers, exhibit unique optical and electronic properties that are size-dependent, allowing for tunable light absorption and emission1,2,3. This tunability is crucial for their application in various fields, including bioimaging and drug delivery systems, where specific wavelengths of light are required for optimal performance4.

Among the various types of QDs, carbon quantum dots (CQDs) have gained considerable attention due to their biocompatibility and reduced toxicity compared to traditional heavy metal-based QDs, such as those containing cadmium or lead. The safety profile of CQDs is particularly important in biomedical contexts, where the potential toxicity of metal-based QDs poses significant concerns5,6. CQDs are derived from carbon-based precursors, often sourced from natural materials, which enhances their suitability for biological applications7,8. Their strong photoluminescence, tunable emission characteristics, and remarkable stability further position them as promising candidates for drug delivery, bioimaging, and biosensing applications6,9.

One of the standout advantages of CQDs lies in their biocompatible substrate, often derived from natural sources such as carbohydrates, proteins, or, as in our study, yeast-based β-glucan polymer. These natural origins not only minimize toxicity but also provide a scaffold for functionalization, allowing for the development of CQDs with specific targeting capabilities and enhanced biological interactions10,11,12. As a result, CQDs synthesized from biopolymers present a sustainable alternative in nanotechnology, enabling the creation of advanced materials that are both effective and environmentally friendly13. In addition to their biocompatibility, these CQDs can be engineered as theranostic nanoplatforms14. Their abundant surface functional groups allow for the loading of therapeutic agents through covalent attachment, electrostatic interaction, or hydrophobic encapsulation15,16. The high surface-to-volume ratio of CQDs facilitates substantial drug payloads, while their surface chemistry can be tuned for controlled and stimuli-responsive release, such as pH- or redox-sensitive release in specific tissues17,18. Furthermore, CQDs can be functionalized with targeting ligands, including peptides, antibodies, or carbohydrates, to promote selective delivery, enhance cellular uptake, and minimize off-target effects19,20. These combined properties enable CQDs to function as multifunctional nanocarriers capable of simultaneous drug delivery and real-time imaging, highlighting their potential in precision medicine and personalized theranostic applications.

β-Glucan is a polymeric polysaccharide composed of β-D-glucose units found in the cell walls of various organisms, including cereals, bacteria, fungi, and yeast. It features linear chains primarily linked by β-(1→3) glycosidic bonds, with some sources also containing β-(1→4) and β-(1→6) linkages, resulting in diverse molecular structures21,22. Yeast cell wall (YCW), a valuable by-product of the food and biotechnology industries, serves as an accessible source for extracting β-glucan23,24. This accessibility positions β-glucan as an appropriate substrate for synthesizing CQDs.

Compared to many other raw materials used in CQDs synthesis, extracted β-glucan offers a uniform composition that ensures consistency in batch-to-batch production25. Additionally, its inherent biocompatibility makes it suitable for biomedical applications, while its rich carbon content significantly contributes to the formation of CQDs with desirable properties. The presence of numerous functional groups (mainly hydroxyl groups) in β-glucan enhances the reactivity of the resulting CQDs, facilitating their interaction with other molecules and improving their performance in applications such as sensing and drug delivery26,27,28.

The integration of green synthesis methods with biocompatible substrates significantly enhances the applicability of CQDs in various fields. By employing environmentally friendly synthesis techniques such as hydrothermal carbonization, a bottom-up aqueous process involving controlled reactions under high pressure and in a sealed autoclave, researchers can produce CQDs without harmful solvents or toxic reagents, thereby minimizing environmental impact29,30. Coupling these sustainable practices with biocompatible materials ensures that the resulting CQDs are not only safe for use in biological applications but also exhibit desirable properties such as enhanced solubility and reactivity. This combination facilitates their integration into medical diagnostics, drug delivery systems, and biosensing technologies, where safety and efficacy are paramount31,32,33.

The primary aim of the present study is to synthesize CQDs from β-glucan, isolated from the cell wall of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, as a novel and sustainable precursor. In contrast to previous studies that used generic carbon sources9,34 or unprocessed YCW materials35, the use of purified β-glucan provides a more uniform and biocompatible substrate that enhances the reproducibility and safety of the synthesis process. Following extraction, the β-glucan is subjected to a green hydrothermal method to produce phosphorus-doped CQDs. The resulting CQDs are then characterized for their chemical and biological features. Ultimately, this research seeks to introduce a valuable biological product that can be further explored for various biological applications.

Materials and methods

Preparation of YCW

The YCW from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, was isolated using enzymatic hydrolysis as described previously35. Briefly, a 15% (w/v) suspension of baker’s yeast (supplied as a dried powder by Razi Yeast and Alcohol Company (Iran) was prepared in distilled water and adjusted to pH 7.0 in a glass vessel. Equal aliquots of Alcalase and Flavourzyme (Novozymes) were added at a 0.5% (v/v) concentration, and the mixture was incubated for 48 h at 55 °C with shaking (200 rpm). To terminate the enzymatic activity, the suspension was boiled for 5 min at 100 °C. The insoluble YCW was then separated from the soluble extract by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 15 min.

Extraction of β-glucan from YCW

The isolation of β-glucan from YCW was conducted using an optimized acid-base extraction method36 with slight modifications. A total of 5 g of YCW was immersed in 200 mL of 0.1 M NaOH (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) solution and boiled for 10 min. The mixture was then cooled to room temperature for 1 h and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting precipitate was washed twice with 200 mL of deionized water and subsequently resuspended in 200 mL of 0.1 M H3PO₄ (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) before being boiled for an additional 10 min. After this step, the precipitate was washed twice more with deionized water. Next, the precipitate was boiled in a stirring setup at 80 °C for 15 min in 200 mL of 96% ethanol (Dr. Mojallali Co., Iran). Following cooling to room temperature, the ethanol was removed by centrifugation at 7000 rpm for 10 min. The precipitate was then dissolved in 200 mL of ethanol and incubated at 4 °C overnight, after which the ethanol was removed through centrifugation at 7000 rpm for 10 min. The precipitate was again boiled in a stirring setup for 15 min at 80 °C in 200 mL of 96% ethanol. Finally, the precipitate was washed with 200 mL of deionized water and separated by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting precipitate was mixed with 10 mL of deionized water, frozen at −20 °C, and then powdered using a freeze dryer. The percentage yield of β-glucan extraction was calculated as follows:

Thermal analysis of β-Glucan, synthesis of CQDs, and quantum yield calculation

Thermo-gravimetric analysis (TGA) coupled with differential thermal analysis (DTA) was performed using an SDT Q600 apparatus (TA Instruments, Spain) to investigate the thermal behavior of the β-glucan. Approximately 20 mg of the sample was heated at a rate of 10 °C min⁻¹ under a helium atmosphere, with a flow rate of 40 mL min⁻¹, over a temperature range of 25 to 600 °C. The thermal data obtained provided the necessary temperature range for efficient CQDs synthesis.

For the synthesis of CQDs, a solution of 1.5% (w/v) β-glucan in a 0.7 M phosphoric acid (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) solution was prepared and stirred for 60 min at 60 °C to achieve homogeneity. This solution was then transferred to a hydrothermal reactor, where it was subjected to thermal treatment at 250 °C for approximately three hours. After the reaction, the reactor was allowed to cool down to ambient temperature, and the resulting solution was decanted. Filtration through a 0.22 μm filter removed undissolved impurities, yielding a purified CQDs suspension with clear transparency and bright blue emission under UV illumination (Supplementary Fig. 1), confirming the successful synthesis of luminescent CQDs.

The fluorescent quantum yield of CQDs was quantified as described previously35. Quinine sulfate (quantum yield 54%, refractive index 1.63) was used as the reference standard. Five concentrations of CQDs in aqueous solution (refractive index 1.33) were prepared and analyzed alongside quinine sulfate to assess their fluorescence properties. Emission spectra of all solutions were recorded upon excitation at 360 nm to assess fluorescence properties. The CQDs’ quantum yield was calculated using the following equation:

ΦCQDs = ΦST(mCQDs/mST)(ηCQDs/ηST).

Where Φ is the quantum yield, m is the slope, η is the refractive index of solvents (H2SO4 for quinine sulfate, and H2O for CQDs), and ST refers to the standard (quinine sulfate).

Purification, UV-visible, and pH-dependent optical characterization of CQDs

To purify the CQDs and eliminate residual small molecules and phosphoric acid, dialysis was carried out based on the diffusion principle. In this process, small molecules such as phosphoric acid and reaction by-products pass through a semi-permeable membrane driven by a concentration gradient, while larger nanomaterials (here CQDs) are retained37. For this purpose, MEMBRA-CEL® membranes (USA) with a 3.5 kDa molecular weight cutoff were used. The dialysis membrane was pretreated by soaking for 10 min in a 2% sodium bicarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 1 mM EDTA (Dr. Mojallali Co., Iran) solution, followed by boiling for 10 min, cooled, and rinsed with deionized water. This process was repeated with 1 mM EDTA. The CQDs solution (10 mL) was placed in the dialysis membrane, sealed, and immersed in 500 mL of deionized water. The setup was stirred for 24 h to ensure thorough purification.

Following dialysis, the purified CQDs solution was subjected to UV–visible absorption spectroscopy using a UV-visible spectrometer (Thermo/Biomate 5, USA) to characterize its optical absorption properties across a wavelength range of 190–800 nm. To understand the quantum confinement of CQDs, the UV-vis results were used to calculate the band gap using the Tauc plot method38. First, the absorbance (A) at each wavelength was used to calculate the absorption coefficient (α) with the formula:

where d is the path length of the cuvette, usually 1 cm. Next, α was multiplied by the photon energy (hν), which was calculated using:

\(\:h\nu\:=\frac{hc}{\lambda\:}\)Here, h is Planck’s constant and c is the speed of light. The product hc is treated as a constant, approximately 1240 eV·nm, and λ is the wavelength in nanometers. A plot of \(\:({\upalpha\:}\text{h}{\upnu\:}{)}^{2}\) versus hν was then made. By extending the straight (linear) portion of this plot to intersect the x-axis, the band gap energy (Eg) was estimated39. Subsequently, the pH of the purified CQDs solution was adjusted to a series of values (1, 2, 3, and 4) to investigate the influence of acidity on the CQDs’ emission behavior. Photoluminescence spectroscopy (PL) was then performed, with the CQDs excited at wavelengths ranging from 310 to 330 nm. Emission spectra were recorded between 340 and 600 nm using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Thermo, Biomate 5, USA) to analyze the CQDs’ fluorescence characteristics under varying pH conditions.

Compositional characterization

Compositional characterization of β-glucan and synthesized CQDs involved several techniques. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) using an FTIR Spectrometer (Nexus 470, USA) analyzed chemical bonds within the 4000–400 cm⁻¹ range. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) analysis, performed with a Philips PW1730 Diffractometer (Poland), examined crystallinity within a 2θ range of 20° to 100°. Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy Mapping (EDX-MAP) on an MIRA II system (France) provided elemental distribution data. These methods collectively enhanced the understanding of the materials’ composition and structure.

Morphological characterization

Dynamic light scattering (DLS), using a zeta potential and particle size analyzer (Horiba SZ100, Japan), was employed to measure the particle size and surface charge. These measurements were performed at 25 °C, with a scattering angle of 90° and an electrode voltage of −3.3 V. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (CM120, Netherlands) was utilized to further investigate the structure and morphology of the CQDs. TEM analysis was conducted at a magnification of 180,000× and an accelerating voltage of 100 kV, yielding both qualitative and quantitative information regarding the size, shape, and internal structure of the CQDs.

Biological properties of CQDs

Disc diffusion analysis

The antimicrobial activity of CQDs was assessed using a disk diffusion assay against a panel of Gram-positive bacteria (Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923) and Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli ATCC 35218, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 14028, Salmonella enteritidis ATCC 13076), all supplied by the Microbiology and Immunology Group of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine (University of Tehran, Iran). The Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain used in this study was isolated from a clinical urine sample and demonstrated antibiotic resistance. Sterile disks impregnated with 30 µl of CQDs suspension (5 µg µL⁻¹) were placed on agar plates. Commercial ciprofloxacin disc (5 µg/disc) served as a control antibiotic. Following a 16-hour incubation at 37 °C, zones of inhibition were measured to determine the effectiveness of CQDs in preventing bacterial growth.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) analysis

The antimicrobial activity of CQDs against Gram-positive (Bacillus cereus, Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus) and Gram-negative (Salmonella typhimurium, Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) bacteria was assessed via a 96-well microtiter plate assay. Bacterial suspensions were standardized to a 0.5 McFarland standard. Serial two-fold dilutions of CQDs (initial concentration: 5 µg µL⁻¹) were performed in the microtiter plate. The MIC was visually determined as the lowest CQDs concentration with no visible turbidity. The MBC was determined by subculturing aliquots from wells following the MIC well onto Mueller-Hinton agar plates and identifying the lowest CQDs concentration with no bacterial colony formation40.

Antioxidant activity

The total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of the CQDs was quantitatively evaluated using the ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay, utilizing a commercial kit (Naxifer®, Navand Salamat, Iran). This assay evaluates antioxidant capacity by reducing ferric ions (Fe³⁺) to ferrous ions (Fe²⁺), which then form a blue ferrous–tripyridyltriazine complex measurable at 593 nm; the intensity of this color change is proportional to the antioxidant level The antioxidant capacity was expressed as mmol Fe²⁺ equivalents and calculated using the following supplier-provided equation:

where ΔOD593 = OD593 4 min − OD593 0 min41.

To investigate the influence of pH on antioxidant activity, CQD samples were pre-adjusted to the desired pH values (0.6, 2, 3, 4, and 7) and incubated at room temperature for 15 min to allow surface functional groups (hydroxyl and carboxyl) to reach equilibrium protonation states. All measurements were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility and statistical validity.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) analysis

To investigate the anti-inflammatory potential of CQDs, an in vitro study was conducted using a blood sample that was voluntarily provided and self-collected by one of the co-authors (minimal-risk self-experimentation). All procedures were carried out in accordance with relevant institutional and international guidelines and regulations. Prior to collection, informed consent was obtained from the participating co-author (self). The ESR, a quantitative indicator of inflammation, was assessed by measuring the rate of red blood cell settling42. Serial concentrations of CQDs (50, 100, 150, and 200 µl of a 5 µg µL⁻¹ solution) were introduced to 10 mL aliquots of anticoagulated blood, using sodium citrate as the anticoagulant. A control group was established with the addition of physiological saline. Following identical processing conditions for both CQD-treated and control samples, ESR values were determined. The impact of CQDs on the sedimentation rate was evaluated by comparing ESR values between treated and control groups.

Cytotoxicity assessment

The cytotoxicity of CQDs was assessed via MTT assay using an in vitro human foreskin fibroblast (HFF) cell line, kindly provided by Dr. Neda Soleimani (Shaid Beheshti University, Iran), serving as a model for normal connective tissue. HFF cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM Gibco, USA) supplemented with streptomycin and 10% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) under aseptic conditions at 37 °C in a humidified, 0.5% CO2 atmosphere. Following trypsinization and quantification using a Neubauer hemocytometer with trypan blue exclusion to confirm viability, 5 × 103 cells/well were seeded into 96-well plates and exposed to varying CQDs concentrations (starting at 15 mg mL⁻¹ with five successive two-fold dilutions) for 24 h. MTT reagent 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was then added, and following a 4-hour incubation, the resulting formazan precipitate was quantified by measuring absorbance at 570 nm, with a reference measurement at 630 nm for background correction. Cell viability was determined by normalizing absorbance values against untreated controls, according to the following equation:

Results

β-glucan extracted yield

YCW-derived β-glucan, extracted and purified, was visually assessed throughout the extraction process. The YCW initially appeared as a milky, viscous paste. After extraction and prior to lyophilization, the β-glucan took the form of an off-white, pelletized, water-insoluble material. Upon lyophilization, the β-glucan converted into a fine, white powder that remained insoluble in water (Fig. 1). The overall extraction yield was determined to be 20%.

Prepared CQDs and quantum yield

The hydrothermal treatment of β-glucan at 250 °C for 3 h resulted in the formation of fluorescent CQDs. This temperature was selected based on TGA/DTA of the β-glucan, which indicated the onset of thermal decomposition at approximately 250 °C (Fig. 2a). During the hydrothermal reaction, the initially clear solution progressively darkened, developing a dark brown hue, indicative of CQDs formation. The resulting solution exhibited fluorescence under UV irradiation. The quantum yield of the synthesized CQDs under these optimized conditions was determined to be 24%, using quinine sulfate as a reference standard. The fluorescence spectra of both quinine sulfate and the synthesized CQDs are presented in Fig. 2b.

Optical characterization

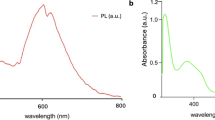

The UV/Vis absorption spectrum of the CQDs, measured from 190 to 800 nm, shows a distinct peak at 201 nm (Fig. 3a), which serves as a fingerprint for their carbon core. This peak arises from π–π* electronic transitions within the sp²-hybridized aromatic domains formed during carbonization, where localized conjugated π-electron systems absorb high-energy UV photons. Such transitions are characteristic of small sp² clusters or graphitic microdomains embedded in an amorphous carbon matrix, confirming the presence of a conjugated graphitic framework that governs the CQDs’ electronic properties43,44. The band gap of the CQDs was calculated to be 5.19 eV from the Tauc plot analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2), affirming the quantum confinement phenomenon in the CQDs due to their sub-10-nm size.

The PL emission spectra of the CQDs, measured across a pH range of 1–4, exhibited a pH-dependent fluorescence response. Under 320 nm excitation, the maximum emission intensity occurred at 380 nm (corresponding to blue light), with the highest intensity observed at pH 2 (Fig. 3b). This pH-dependent behavior suggests that the protonation state of surface functional groups modulates the radiative recombination pathways of excitons, likely through alterations in surface charge or defect states.

Compositional profiling

The FTIR analysis of β-glucan and its derived CQDs reveals significant chemical and structural transformations occurring during the synthesis process (Fig. 4a). Comparative spectral evaluation indicates progressive transformations primarily associated with carbonization and oxidation. The β-glucan spectrum shows a broad O-H stretching band between 3000 and 3600 cm⁻¹, indicative of abundant hydroxyl groups typical of polysaccharides. C-H stretching vibrations around 2900 cm⁻¹ and C-H bending vibrations in the 1300–1450 cm⁻¹ range correspond to the sugar ring hydrogens. The peak near 1640 cm⁻¹ is attributed to absorbed water, commonly found in hydrated polysaccharides. Crucially, the presence of strong C-O-C stretching vibrations between 1000 and 1200 cm⁻¹ provides definitive evidence of glycosidic linkages, which are the hallmark of β-glucan’s β-(1→3) and β-(1→4) or β-(1→6) glycosidic bonds. Together, these spectral features confirm the polysaccharide nature and the specific β-glucan structure of the sample. In contrast, the CQDs spectrum exhibits a significant reduction in the O-H stretching band’s intensity, suggesting fewer hydroxyl groups due to dehydration during the hydrothermal carbonization process. A new peak around 1700 cm- 1 indicates carbonyl (C = O) group formation from β-glucan oxidation, and broadened, less intense peaks in the 1000–1200 cm- 1 region, suggesting disrupted glycosidic linkages and smaller carbon structures. Additionally, Changes observed in the 500–700 cm⁻¹ region suggest that the hydrothermal process disrupts β-glucan’s pyranose rings and alters hydroxyl groups, leading to the formation of smaller, more amorphous carbon structures in the CQDs. These spectral changes collectively confirm the transformation of β-glucan into CQDs, with carbonization and oxidation indicated by the reduced O-H intensity and the presence of C = O bonds, along with the breakdown of the polysaccharide structure.

Compared to the broad XRD peak of β-glucan, the CQDs exhibit a significantly broadened and less intense peak at approximately the same 2θ angle. This indicates a transformation from the short-range order of the β-glucan polysaccharide into smaller, more disordered amorphous carbon nanostructures in the CQDs (Fig. 4b). The absence of any discernible (002) peak shift or lattice distortion further suggests that phosphorus is predominantly present as surface-bound phosphate or phosphonate groups rather than being incorporated into the carbon lattice.

The EDX-MAP revealed significant compositional changes following hydrothermal carbonization of β-glucan into CQDs (Fig. 4c). The EDX spectrum of β-glucan shows prominent carbon (C, ~ 0.2 keV) and oxygen (O, ~ 0.5 keV) peaks, consistent with its polysaccharide structure. A smaller sodium (Na) peak is also present (~ 1 keV), potentially indicating residual counterions. The CQDs’ spectrum exhibits a markedly reduced carbon peak intensity and a lower relative oxygen signal, reflecting a shift in surface elemental composition rather than a true decrease in bulk content. A strong phosphorus (P, ~ 2 keV) peak confirms the successful incorporation of phosphoric acid during hydrothermal treatment. The presence of potassium (K, ~ 3.3 keV) is also noted, likely originating from the K₂HPO₄/KH₂PO₄ buffer used during dialysis. The decrease in carbon and oxygen, coupled with phosphorus doping, suggests dehydration and the surface of the carbon nanodots. These changes confirm the transformation of β-glucan into phosphorus-doped CQDs. Since EDX primarily probes surface elements45, the detected phosphorus is likely concentrated at the CQDs’ surface, possibly as phosphate or phosphonate groups. This surface enrichment accounts for the reduced relative carbon peak and the apparent increase in oxygen, reflecting dehydration and surface oxidation during carbonization.

Morphological characterization

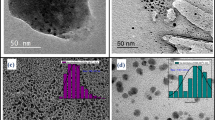

DLS analysis showed that the synthesized CQDs have a broad size distribution, with most particles below 100 nm and a sharp peak at 41.9 nm (Fig. 5a). The DLS original report is provided as Supplementary File 1. The average hydrodynamic diameter measured by DLS is much larger than the expected core size (< 10 nm) because DLS accounts for the nanoparticle core, surface functional groups, adsorbed solvent, and possible aggregation. Surface functionalities such as carboxyl and hydroxyl groups, along with minor aggregation, further increase the measured size. Zeta potential measurements revealed a narrow distribution centered at −2.9 mV (Fig. 5b), indicating low surface charge and limited electrostatic stabilization, which promotes aggregation and contributes to the larger hydrodynamic size. TEM imaging at two different magnifications (Fig. 5c) shows that the particles are nearly spherical, well-dispersed, and have an average core size of 3–7 nm. Although the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern was not recorded in this session, the absence of clear lattice fringes in the high-magnification image suggests an amorphous or weakly crystalline structure. This structural feature is consistent with the observed blue emission, as quantum confinement in small or disordered particles often leads to higher-energy emission. The discrepancy between the particle sizes obtained from DLS and TEM is typical for CQDs, as DLS measures the hydrodynamic diameter, which reflects not only the core size but also the influence of surface functional groups and solvent interactions. In contrast, TEM provides the true physical core size. The relatively low zeta potential further indicates a moderate tendency toward particle association in dispersion, contributing to the larger apparent hydrodynamic size observed in the DLS analysis.

Structural and Physicochemical Characterization of CQDs. (a) Hydrodynamic diameter distribution of CQDs nanoparticles via DLS. (b) Zeta potential measurement indicating surface charge stability of CQDs nanoparticles. (c) High-resolution TEM micrograph visualizing CQDs morphology and nanoscale dimensions.

Bioactive properties of CQDs

Antibacterial characterization

The disk diffusion assay demonstrated that CQDs possess antibacterial activity against all tested bacterial strains. When compared to ciprofloxacin, which served as the positive control, CQDs produced measurable zones of growth inhibition, indicating their potential as antimicrobial agents. The diameters of the inhibition zones are presented in Fig. 6. Notably, for the antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate, CQDs exhibited greater antibacterial efficacy than ciprofloxacin at the tested concentration.

Antibacterial activity of CQDs evaluated by disk diffusion assay. The inhibition zones produced by CQDs against the tested bacterial strains demonstrate their broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties. The diameters of these zones are shown in the spike plot alongside those of the positive control, ciprofloxacin.

The MIC and MBC values of the CQDs against the tested bacterial strains are presented in Table 1. The data demonstrate that CQDs possess considerable antibacterial activity, showing greater efficacy against Gram-positive bacteria compared to Gram-negative bacteria.

The plates showing bacterial colony formation are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Antioxidant analysis

The TAC of CQDs at different pH values is presented in Table 2. The results indicate that TAC is highest under strongly acidic conditions, with a gradual decrease observed as the pH increases. This trend is likely due to the deprotonation of surface –COOH and –OH functional groups at higher pH, which diminishes the electron-donating ability of CQDs, to reduce Fe³⁺ → Fe²⁺ in the FRAP assay, and consequently reduces their apparent antioxidant activity.

ESR assay

The in vitro ESR assay demonstrated a significant, concentration-dependent reduction in red blood cell sedimentation upon the introduction of CQDs to the blood sample. Specifically, adding 200 µl of CQDs (5 µg µL⁻¹) decreased ESR from 12 mm h⁻¹ to 1 mm h⁻¹ (Fig. 7), indicating CQDs’ potential to modulate erythrocyte aggregation and inflammatory processes in vitro.

Cytotoxicity assessment

The MTT assay revealed a dose-dependent cytotoxicity of CQDs. At 15 mg mL⁻¹, cell viability decreased to approximately 20%, based on formazan absorbance at 570 nm. Conversely, at ~ 47 µg mL⁻¹, viability exceeded 70%, indicating low cytotoxicity at lower concentrations. Progressive dilution of CQDs corresponded with increased cell viability. Absorbance readings at 630 nm showed a consistent trend, supporting live cell quantification (Fig. 8a). Figure 8b illustrates the reduction of formazan crystals across three increasing CQDs concentrations.

Discussion

CQDs synthesized from carbohydrate-based polymers such as cellulose, chitosan, starch, and yeast wall glucans have emerged as promising nanomaterials due to their sustainable origins and favorable physicochemical properties. The intrinsic features of these natural precursors—rich in hydroxyl groups, heteroatoms, and biocompatible structures—not only facilitate environmentally friendly “one-pot” hydrothermal or solvothermal synthesis methods but also significantly influence the functional attributes of the resulting CQDs46,47,48. Notably, the precursor material plays a critical role in determining the elemental makeup, surface chemistry, and bioactivity of CQDs, which in turn affect their optical, electronic, and biomedical performance33,49,50. CQDs derived from these green sources often exhibit desirable traits such as low toxicity and enhanced solubility, making them especially suitable for biological applications50,51,52. Therefore, careful selection of the precursor material is essential, as it allows the retention and amplification of specific beneficial characteristics during synthesis, aligning the final product with targeted application needs49,50.

The novelty of this work lies in the introduction of Saccharomyces cerevisiae β-glucan as a previously unexplored, sustainable precursor for the synthesis of multifunctional CQDs. While numerous studies have reported the preparation of CQDs from common carbon sources such as citric acid, glucose, or plant-based polysaccharides53,54, the use of yeast-derived β-glucan offers distinct structural and biological advantages. In our previous study, we utilized the whole YCW as a carbon source for CQDs synthesis and demonstrated its strong biological activity35; however, the YCW is a complex, multilayered structure composed primarily of β-glucans, mannoproteins, chitin, and minor amounts of lipids55. Because the composition and cross-linking density of these components vary depending on growth phase, nutrient availability, and fermentation conditions, the chemical makeup of YCW can fluctuate significantly between batches56, leading to heterogeneity in the resulting CQDs’ properties and limiting scalability.

In contrast, the present study isolates and purifies β-glucan as a single, well-defined polysaccharide precursor with a homogeneous and reproducible molecular structure. The well-characterized architecture and high β-glucan content of the YCW57 not only facilitate efficient extraction but also ensure consistency in the molecular composition between batches. This uniformity provides greater control over the carbonization process and the resulting nanomaterial characteristics. Consequently, the use of purified β-glucan minimizes batch-to-batch variability, enabling the production of uniform CQDs suitable for upscale manufacturing while preserving the biocompatibility and eco-friendly nature of the synthesis.

Yeast-derived β-glucan from Saccharomyces cerevisiae possesses a highly branched architecture with a β-(1→3)-linked backbone and β-(1→6)-linked side chains, contributing to its high molecular weight and structural complexity58. The branching introduces a dense network of hydroxyl groups and reactive sites, which participate in dehydration reactions and facilitate the formation of intermediates that promote nucleation during hydrothermal carbonization59. It is plausible that the rigid β-(1→3) backbone supports more orderly carbonization60. These structural characteristics suggest yeast β-glucan could be an effective and sustainable precursor for CQD synthesis, though further research is needed to fully elucidate these effects. Notably, β-Glucan is known for its biocompatibility, immunomodulatory, and antioxidant properties61,62. If these beneficial characteristics are retained—or potentially enhanced—in CQDs synthesized from β-glucan, the resulting nanomaterials could offer significant advantages for biomedical and therapeutic applications. In support of this, Ashraf and co-authors demonstrated that nanoreduction of β-glucan from cereal and fungal sources enhanced its nutraceutical properties, likely due to nanoscale transformation achieved through green technology63.

For the extraction of β-glucan, the cell wall of Saccharomyces cerevisiae was selected as the source. The YCW is an abundant and sustainable source of high-purity β-glucan, providing consistent quality and yield57,64. Saccharomyces cerevisiae is classified as Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS), ensuring the safety and biocompatibility of the derived β-glucan for use in biological systems65.

The study details the successful extraction of β-glucan from YCW with a 20% yield and its subsequent transformation into fluorescent CQDs via hydrothermal treatment at 250 °C for 3 h. This temperature was carefully selected based on TGA/DTA analysis, coinciding with the onset of β-glucan’s thermal decomposition. The formation of CQDs was visually confirmed by the darkening of the solution and fluorescence under UV light. The hydrothermal protocol afforded a photoluminescence quantum yield of 24%, surpassing the 19% recently reported for yeast-wall CQDs prepared at comparable temperature but shorter dwell times35. The quantum yield of 24% achieved for our CQDs aligns well with typical values reported in the literature for cellulose-derived dots without post-passivation66. Higher quantum yields exceeding 50% have been reported through strategies such as surface passivation and nitrogen doping67, which represent promising avenues for future improvement in this study. Additionally, the use of small molecule precursors like citric acid combined with (NH₄)₂HPO₄ has also yielded high quantum efficiencies68. However, these approaches often rely on pure chemical reagents and generate considerable salt waste, raising environmental concerns. In contrast, our synthesis utilizes an industrial by-product and only food-grade acid, offering a greener and more sustainable alternative that balances optical performance with eco-friendly principles. The moderate quantum yield of our CQDs is likely limited by non-radiative quenching pathways such as surface defect states from carbonyl and phosphate groups that act as non-radiative centers and phosphorus doping that can introduce trap states competing with radiative recombination69,70.

The strong π–π* absorption at 201 nm fingerprints an sp²-rich carbon core, and this is further supported by the XRD pattern, where a characteristic peak around 2θ ≈ 24° is observed, indicative of sp² hybridized carbon structures71. The fluorescence emission maximum at 380 nm intensifies twofold as the pH decreases from 4 to 2, providing further evidence for proton-controlled surface states. This pH-dependent fluorescence behavior suggests that the surface chemistry of the CQDs, particularly the protonation of functional groups, plays a significant role in modulating their electronic properties and fluorescence efficiency72. The calculated band gap of 5.19 eV supports these findings, as it suggests that the CQDs are in the quantum confinement regime, where the electronic structure is highly sensitive to surface interactions. The high band gap indicates a strong confinement effect, which could be responsible for the enhanced fluorescence under acidic conditions. Such tunability is attractive for ratiometric fluorescence sensing in acidic micro-environments (e.g., lysosomes or tumour interstitium), validating the synthesized CQDs as a tunable optical platform. However, certain challenges remain for in vivo translation, including the relatively narrow cytocompatibility window observed in vitro, limited colloidal stability resulting from low surface charge, and the possibility of defect-related signal variability in complex biological matrices. Thus, further optimization through surface passivation or targeted delivery will be required to achieve safe and stable performance in biological systems.

Morphological characterization using DLS revealed a broad size distribution with a peak at 41.8 nm, while TEM imaging showed much smaller core sizes below 10 nm. This discrepancy arises because DLS measures the hydrodynamic diameter in solution, which includes the contributions of surface functional groups and particle aggregation, while the TEM images reflect the isolated, dehydrated particle cores. The low zeta potential of − 2.9 mV indicates weak electrostatic repulsion, leading to mild aggregation and poor colloidal stability, as supported by broad size distribution in DLS. For future studies, exploring mild passivation of CQDs with natural polymers like chitosan or dextran could enhance colloidal stability while preserving green synthesis. Additionally, functionalizing surface hydroxyl and carbonyl groups or introducing benign dopants during synthesis may improve dispersion without compromising eco-friendliness73. Notably, the observed blue fluorescence aligns with the small core size seen in TEM, which is consistent with quantum confinement effects typically responsible for blue-shifted emission in smaller CQDs. The amorphous nature of the CQDs further contributes to their broad emission spectra and enables easy tuning of their optical properties74,75.

During hydrothermal carbonization, carbohydrate polymers break down into smaller monomers through a series of reactions, including hydrolysis, dehydration, decarboxylation, condensation, polymerization, and aromatization76. FTIR analysis reveals a marked reduction in hydroxyl (O-H) groups, indicating dehydration reactions, while the emergence of carbonyl (C = O) groups reflects oxidation processes. Concurrently, the characteristic vibrations of glycosidic linkages in the 1000–1200 cm^−1 region decrease in intensity, indicating cleavage of these bonds and partial breakdown of the polysaccharide structure. XRD data show peak broadening and intensity reduction associated with the semi-crystalline nature of β-glucan, consistent with conversion into smaller, amorphous carbon-based nanostructures through ring-opening and fragmentation of sugar units. Meanwhile, phosphorus incorporation occurs through doping by phosphoric acid during hydrothermal carbonization, likely bonding with carbonyl and hydroxyl functional groups formed during these processes.

Disk diffusion, MIC, and MBC assays demonstrated broad-spectrum antibacterial activity of the synthesized CQDs, with inhibition zones surpassing those of ciprofloxacin against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The pronounced antibacterial activity of β-glucan–derived CQDs, particularly against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, is likely the result of multiple, synergistic mechanisms rather than a single pathway. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation is considered the dominant factor, as CQDs can catalyze electron transfer processes that induce oxidative stress, leading to lipid peroxidation, protein denaturation, and DNA damage50,77. At the same time, phosphorus doping in our CQDs may enhance electron density and introduce defect sites that facilitate ROS production, thereby amplifying oxidative damage78. In agreement with this, Chai et al. (2022) showed that increasing phosphorus doping in CQDs enhanced ROS generation, particularly singlet oxygen (¹O₂), which significantly improved antibacterial activity79. Additionally, the near-neutral zeta potential may facilitate adhesion to negatively charged Gram-positive bacterial surfaces, potentially explaining the lower MICs observed for Bacillus and Staphylococcus species80.

FRAP assays confirmed the high total TAC of the CQDs, with the strongest activity observed under highly acidic conditions (pH ≤ 2). This behavior is consistent with proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) processes, where protonation of surface carbonyl and hydroxyl groups facilitates electron donation and promotes redox cycling between CQD surface states81,82, thereby accelerating Fe³⁺ → Fe²⁺ reduction. Acidic environments may also increase the density of protonated defect sites, which act as active centers for redox reactions, further enhancing antioxidant performance83. Such proton-enhanced electron transfer explains why CQDs display dual redox behavior—acting as both electron donors and acceptors—depending on pH and surface chemistry84. This redox and optical duality, particularly under acidic conditions, highlights the potential of β-glucan–derived CQDs as smart nanomaterials for applications such as drug delivery and bioimaging in acidic microenvironments, including tumors and inflamed tissues85,86.

The ESR assay showed a strong, dose-dependent anti-inflammatory effect: adding 200 µl of CQDs (5 µg µL⁻¹) suppressed the patient’s mildly elevated ESR from 12 mm h⁻¹ to just 1 mm h⁻¹. Because accelerated sedimentation in inflammation is driven by fibrinogen-mediated rouleaux formation, such a 12-fold reduction implies that the CQDs either minimize protein bridging —by adsorbing fibrinogen, sterically hindering its interaction with RBCs, or altering RBC membranes—or help preserve the electrostatic repulsion between erythrocytes87,88,89. ISO 10993-5 flags < 70% viability as cytotoxic90. Our dots preserved > 70% viability at ~ 47 µg mL⁻¹ in HFF cells. Above 1 mg mL⁻¹, viability collapsed; thus, therapeutic windows in the 10–100 µg mL⁻¹ regime appear safe for imaging or topical antimicrobial use. The observed cytotoxicity at higher concentrations is likely due to the high surface reactivity and functional groups of phosphorus-doped CQDs, which may induce oxidative stress or membrane disruption even in normal cells. These findings suggest that although systemic administration may be limited by cytotoxicity at higher doses, the concentrations required to elicit anti-inflammatory effects fall within a range that could be safely achieved through localized or topical applications. Moreover, future optimization strategies such as surface passivation or encapsulation may further expand the therapeutic window, enabling the safe use of these CQDs in biomedical contexts91.

To our knowledge, this is the first report employing yeast β-glucan as a precursor for phosphorus-doped CQDs synthesized under green conditions, yielding diverse biological and optical functionalities. Our eco-friendly and scalable synthesis uses food-grade phosphoric acid and a simple hydrothermal process without hazardous solvents, making it suitable for industrial production. The resulting CQDs show strong antibacterial activity surpassing ciprofloxacin against resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, along with notable antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and pH-responsive optical properties for biomedical sensing. Further work is needed to enhance colloidal stability and clarify ROS-related mechanisms. This establishes a sustainable nanomaterial platform with promising theranostic and biomedical applications.

As the final point, the hydrothermal synthesis of CQDs from YCW β-glucan demonstrates notable potential for industrial scale-up, supported by several advantageous factors. The YCW, being an abundant and low-cost industrial byproduct, provides a sustainable and economical carbon source. The hydrothermal synthesis process itself is straightforward and environmentally benign, functioning without the need for hazardous or complex reagents. Additionally, the well-defined chemical composition of yeast β-glucan allows for consistent CQDs quality across production batches, an essential factor for scalability. Importantly, synthesis parameters such as temperature, reaction time, and precursor concentration can be effectively optimized and controlled in larger reactors or continuous flow setups, which could enhance yield, uniformity, and overall cost-efficiency. Future pilot-scale experiments and further process optimization will be crucial steps to facilitate the transition from laboratory research to commercial-scale manufacturing.

Conclusion

This study addressed the growing need for sustainable and biocompatible nanomaterials by developing phosphorus-doped CQDs from yeast-derived β-glucan through a simple and eco-friendly hydrothermal synthesis. The use of purified β-glucan enabled a reproducible and green route for producing CQDs with strong blue photoluminescence (24% quantum yield), pH-dependent emission, and core sizes below 10 nm. These CQDs exhibited broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, surpassing ciprofloxacin against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, along with notable antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and acceptable biocompatibility at lower concentrations. Collectively, these features highlight their potential as multifunctional nanomaterials for biomedical, diagnostic, and therapeutic applications. However, the moderate quantum yield, limited colloidal stability due to low surface charge, and cytotoxicity at higher doses remain challenges to be addressed. Future studies should therefore focus on surface passivation, polymer coating, and in vivo assessments to enhance stability, safety, and functional performance. Overall, this work presents a scalable, sustainable, and biologically compatible platform for next-generation carbon-based nanomaterials that bridge green synthesis with biomedical innovation.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Huang, C., Dong, H., Su, Y., Wu, Y., Narron, R., & Yong, Q. Synthesis of carbon quantum Dot nanoparticles derived from byproducts in bio-refinery process for cell imaging and in vivo bioimaging. Nanomaterials 9, 387 (2019).

Gomase, A., Sangale, S., Mundhe, A., Gadakh, P. & Nikam, V. Quantum dots: method of Preparation and biological application. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 9, 670–672 (2019).

Kalifathullah, S. K. & Sundaramurthy, D. Exploration of biological activities of green N-Carbon quantum Dots and photocatalytic studies of ZnO@ N-CQDs. Emergent Mater. 7, 2755–2766 (2024).

Sharma, A. & Das, J. Small molecules derived carbon dots: synthesis and applications in sensing, catalysis, imaging, and biomedicine. J. Nanobiotechnol. 17, 92 (2019).

Du, Y. & Guo, S. Chemically doped fluorescent carbon and graphene quantum Dots for bioimaging, sensor, catalytic and photoelectronic applications. Nanoscale 8, 2532–2543 (2016).

Hoan, B. T., Tam, P. D. & Pham, V. H. Green synthesis of highly luminescent carbon quantum dots from lemon juice. J. Nanotechnol. 2019, 2852816 (2019).

Yadav, P. K., Chandra, S., Kumar, V., Kumar, D. & Hasan, S. H. Carbon quantum dots: synthesis, structure, properties, and catalytic applications for organic synthesis. Catalysts 13, 422 (2023).

Nair, A., Haponiuk, J. T., Thomas, S. & Gopi, S. Natural carbon-based quantum Dots and their applications in drug delivery: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 132, 110834 (2020).

Dhanush, C., Aravindh, S., Jesreena, J. S., Nagadharshini, R., Jano, N., Almeer, R., & KP Velu, S. Biomimetic synthesis of carbon Dots from mimosa pudica leaves for enhanced bioimaging. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 16, 713–721 (2025).

Pandiyan, S., Arumugam, L., Srirengan, S.P., Pitchan, R., Sevugan, P., Kannan, K., Pitchan, G., Hegde, T.A. & Gandhirajan, V. Biocompatible carbon quantum Dots derived from sugarcane industrial wastes for effective nonlinear optical behavior and antimicrobial activity applications. ACS Omega. 5, 30363–30372 (2020).

Wang, X., Wu, T., Yang, Y., Zhou, L., Wang, S., Liu, J., Zhao, Y., Zhang, M., Zhao, Y., Qu, H. & Kong, H. Ultrasmall and highly biocompatible carbon Dots derived from natural plant with amelioration against acute kidney injury. J. Nanobiotechnol. 21, 63 (2023).

Tian, X., Zeng, A., Liu, Z., Zheng, C., Wei, Y., Yang, P., Zhang, M., Yang, F. & Xie, F.Carbon quantum dots: in vitro and in vivo studies on biocompatibility and biointeractions for optical imaging. Int. J. Nanomedicine 15, 6519–6529 (2020).

Latif, Z., Shahid, K., Anwer, H., Shahid, R., Ali, M., Lee, K. H., & Alshareef, M. Carbon quantum Dots (CQDs) modified polymers: a mini review of non-optical applications. Nanoscale 16, 2265–2285 (2024).

Gowtham, P., Girigoswami, K., Prabhu, A. D., Pallavi, P., Thirumalai, A., Harini, K., & Girigoswami, A. Hydrogels of alginate derivative‐encased nanodots featuring carbon‐coated manganese ferrite cores with gold shells to offer antiangiogenesis with multimodal imaging‐based theranostics. Adv. Therapeut. 7, 2400054 (2024).

González, M. & Romero, M. P. Surface-Modified carbon Dots for cancer therapy: integrating diagnostic and therapeutic applications. Int. J. Nanomedicine 20, 7715–7741 (2025).

Molaei, M. J. Carbon quantum Dots and their biomedical and therapeutic applications: a review. RSC Adv. 9, 6460–6481 (2019).

Noel, K. J., Umashankar, M. S. & Narayanasamy, D. & Umashankar Sr, M. S. Exploring research on the drug loading capacity of quantum Dots. Cureus 16, e67869 (2024).

Kirubanithy, K. & Santhanam, A. A pH-responsive nanocarrier of peanut shell carbon quantum Dots as a promising delivery of doxorubicin for cancer therapy. Sci. Rep. 15, 33885 (2025).

Fatima, I., Rahdar, A., Sargazi, S., Barani, M., Hassanisaadi, M., & Thakur, V. K. Quantum dots: synthesis, antibody conjugation, and HER2-receptor targeting for breast cancer therapy. J. Funct. Biomater. 12, 75 (2021).

Kazemi, K., Amini, A., Omidifar, N., Aghabdollahian, S., Raee, M. J., & Gholami, A. Empowering rapid diagnosis and treatment of glioblastoma with biofunctionalized carbon quantum dots: a review. Cancer Nanotechnol. 16, 13 (2025).

Lee, C., Verma, R., Byun, S., Jeun, E.J., Kim, G.C., Lee, S., Kang, H.J., Kim, C.J., Sharma, G., Lahiri, A. & Paul, S. Structural specificities of cell surface β-glucan polysaccharides determine commensal yeast mediated immuno-modulatory activities. Nat. Commun. 12, 3611 (2021).

Liu, Y., Wu, Q., Wu, X., Algharib, S.A., Gong, F., Hu, J., Luo, W., Zhou, M., Pan, Y., Yan, Y. & Wang, Y. Structure, preparation, modification, and bioactivities of β-glucan and Mannan from yeast cell wall: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 173, 445–456 (2021).

Jofre, F. M., Queiroz, S. D. S., Sanchez, D. A., Arruda, P. V., Santos, J. C. D., & Felipe, M. D. G. D. A. Biotechnological potential of yeast cell wall: an overview. Biotechnol. Progr. 40, e3491 (2024).

Yousefi, L. Yeast mannan: Structure, extraction and bioactivity. Appl. Food Biotechnol. 10, 155–164 (2023).

Gan, J., Chen, L., Chen, Z., Zhang, J., Yu, W., Huang, C., Wu, Y. & Zhang, K. Lignocellulosic biomass-based carbon dots: synthesis processes, properties, and applications. Small 19, 2304066 (2023).

Yuan, H., Lan, P., He, Y., Li, C. & Ma, X. Effect of the modifications on the physicochemical and biological properties of β-glucan—A critical review. Molecules 25, 57 (2019).

Chioru, A. & Chirsanova, A. β-Glucans: Characterization, extraction Methods, and valorization. Food Nutr. Sci. 14, 963–983 (2023).

Su, Y., Chen, L., Yang, F. & Cheung, P. C. Beta-d-glucan-based drug delivery system and its potential application in targeting tumor associated macrophages. Carbohydr. Polym. 253, 117258 (2021).

Yadav, R., Lahariya, V. & Bansal, V. Evaluation of thermal behavior and properties of carbon Dots prepared by green synthesis. ECS Trans. 107, 14445 (2022).

Dhanush, C. & Sethuraman, M. Independent hydrothermal synthesis of the undoped, nitrogen, Boron and sulphur doped biogenic carbon nanodots and their potential application in the catalytic chemo-reduction of Alizarine yellow R Azo dye. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 260, 119920 (2021).

Dua, S., Kumar, P., Pani, B., Kaur, A., Khanna, M., & Bhatt, G. Stability of carbon quantum dots: a critical review. RSC Adv. 13, 13845–13861 (2023).

Kumar, A., Kumar, I. & Gathania, A. K. Synthesis, characterization and potential sensing application of carbon Dots synthesized via the hydrothermal treatment of cow milk. Sci. Rep. 12, 22495 (2022).

Azam, N., Ali, N., Javaid Khan, T. & M. & Carbon quantum Dots for biomedical applications: review and analysis. Front. Mater. 8, 700403 (2021).

Dhanush, C., Aravind, M. K., Ashokkumar, B. & Sethuraman, M. G. Synthesis of blue emissive fluorescent nitrogen doped carbon Dots from Annona squamosa fruit extract and their diverse applications in the field of catalysis and bio-imaging. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 432, 114097 (2022).

Mirseyed, P. S., Arjmand, S., Rahmandoust, M., Kheirabadi, S. & Anbarteh, R. Green synthesis of yeast cell wall-derived carbon quantum Dots with multiple biological activities. Heliyon 10, e29440 (2024).

Asare, S. O. Optimized Acid/base Extraction and Structural Characterization of β-glucan from Saccharomyces Cerevisiae (East Tennessee State University, 2015).

Bian, Z., Gomez, E., Gruebele, M., Levine, B. G., Link, S., Mehmood, A., & Nie, S. Bottom-up carbon dots: purification, single-particle dynamics, and electronic structure. Chem. Sci. 16, 4195–4212 (2025).

Tauc, J., Grigorovici, R. & Vancu, A. Optical properties and electronic structure of amorphous germanium. Phys. Status Solidi (b). 15, 627–637 (1966).

Jumardin, J., Maddu, A., Santoso, K. & Isnaeni, I. Synthesis of carbon dots (CDS) and determination of optical gap energy with Tauc plot method. Jambura Phys. J. 3, 73–86 (2021).

Swebocki, T., Barras, A. & Kocot, A. M. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) Assays Using Broth Microdilution Method. (2023).

Benzie, I. F. & Strain, J. J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of antioxidant power: the FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 239, 70–76 (1996).

Alharthi, A.H., Al-Shehri, S.H.A., Albarqi, M.A.A., Alshehri, M.S., Alshehri, A.M., Amer, A.M., Alshehri, M.H., Alshehri, A.H.S., Alshehri, S.H.S. & Alassiry, A.M.A. Laboratory markers of inflammation: CRP and ESR in clinical practice. J. Int. Crisis Risk Communication Res. 7, 2376 (2024).

Boruah, A. & Saikia, B. K. Chemical Fabrication of Efficient Blue-luminescent Carbon Quantum Dots from Coal Washery Rejects (Waste) for Detection of Hg2 + and Cr6 + Ions in Water. ChemistrySelect 7, e202104567 (2022).

Dhanush, C. & Sethuraman, M. Influence of phyto-derived nitrogen doped carbon Dots from the seeds of Azadirachta indica on the NaBH4 reduction of Safranin-O dye. Diam. Relat. Mater. 108, 107984 (2020).

Shukla, G., Gaurav, S. S., Rani, V., Singh, A., Rani, P., Verma, P., & Kumar, B. Evaluation of larvicidal effect of mycogenic silver nanoparticles against white Grubs (Holotrichia sp). J. Adv. Sci. Res. 11, 296–304 (2020).

Wang, J., Zhang, X., & Li, Y. Recent advances in carbon quantum dots derived from natural polymers: Synthesis, properties, and applications. J. Carbon Res. 10, 45–67 (2024).

Emam, H. E. Clustering of photoluminescent carbon quantum Dots using biopolymers for biomedical applications. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 42, 102382 (2022).

Thodikayil, A. T., Sharma, S. & Saha, S. Engineering carbohydrate-based particles for biomedical applications: strategies to construct and modify. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 4, 2907–2940 (2021).

Mozdbar, A., Nouralishahi, A., Fatemi, S. & Mirakhori, G. in AIP Conference Proceedings. (AIP Publishing).

Wu, Y., Li, C., van der Mei, H. C., Busscher, H. J. & Ren, Y. Carbon quantum Dots derived from different carbon sources for antibacterial applications. Antibiotics 10, 623 (2021).

Kong, J., Wei, Y., Zhou, F., Shi, L., Zhao, S., Wan, M., & Zhang, X. Carbon quantum dots: properties, preparation, and applications. Molecules 29, 2002 (2024)

Kalifathullah, S. K., Alaguvel, S. & Sundaramurthy, D. Efficient synthesis of green nitrogen-doped carbon Dots as a versatile nanoprobe for antibacterial, cytotoxic, in-vitro imaging, and anti-counterfeit applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 178, 114473 (2025).

Hill, S. & Galan, M. C. Fluorescent carbon Dots from mono-and polysaccharides: synthesis, properties and applications. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 13, 675–693 (2017).

Xu, X., Wang, X., Du, W., Liu, S., Qiao, Z., & Zhou, Y. Hydrothermal synthesis of biomass-derived cqds: advances and applications. Nanatechnol. Reviews 14, 20250184 (2025).

Lesage, G. & Bussey, H. Cell wall assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 317–343 (2006).

Sadeghi, A., Purabdolah, H., Hajinia, F., Shahryari, S., Taheri, F., Ebrahimi, M., Assadpour, E. & Jafari, S.M. Emerging functionalities of yeast cell-wall components; the value-added food-grade pre-and post-biotics. Appl. Food Res. 5, 101072 (2025).

Shokri, H., Asadi, F. & Khosravi, A. R. Isolation of β-glucan from the cell wall of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Prod. Res. 22, 414–421 (2008).

Aimanianda, V., Clavaud, C., Simenel, C., Fontaine, T., Delepierre, M., & Latge, J. P. Cell wall β-(1, 6)-glucan of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: structural characterization and in situ synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 13401–13412 (2009).

Bhagat, P., Patil, K., Bodas, D. & Paknikar, K. Hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of carbon nanospheres: a mechanistic insight. RSC Adv. 5, 59491–59494 (2015).

Huang, J., Chen, Y., Leng, K., Liu, S., Chen, Z., Chen, L., Wu, D. & Fu, R. Morphology-persistent carbonization of self-assembled block copolymers for multifunctional coupled two-dimensional porous carbon hybrids. Chem. Mater. 32, 8971–8980 (2020).

Singh, R. P. & Bhardwaj, A. β-glucans: A potential source for maintaining gut microbiota and the immune system. Front. Nutr. 10, 1143682 (2023).

Zhong, X., Wang, G., Li, F., Fang, S., Zhou, S., Ishiwata, A., Tonevitsky, A.G., Shkurnikov, M., Cai, H. & Ding, F. Immunomodulatory effect and biological significance of β-glucans. Pharmaceutics 15, 1615 (2023)

Ul Ashraf, Z., Shah, A., Gani, A., Gani, A., Masoodi, F. A., & Noor, N. Nanoreduction as a technology to exploit β-Glucan from cereal and fungal sources for enhancing its nutraceutical potential. Carbohydr. Polym. 258, 117664 (2021).

Gautério, G. V., Silvério, S. I. D. C., Egea, M. B. & Lemes, A. C. β-glucan from brewer’s spent yeast as a techno-functional food ingredient. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 2, 1074505 (2022).

Schauss, A. G., Glavits, R., Endres, J., Jensen, G. S. & Clewell, A. Safety evaluation of a proprietary food-grade, dried fermentate Preparation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Int. J. Toxicol. 31, 34–45 (2012).

Sheshmani, S., Mardali, M., Shokrollahzadeh, S., Bide, Y. & Tarlani, R. Synthesis, optical, and photocatalytic properties of cellulose-derived carbon quantum Dots. Sci. Rep. 15, 19027 (2025).

Liang, S., Wang, M., Gao, W. & Zhao, X. Effects of elemental doping, acid treatment, and passivation on the fluorescence intensity and emission behavior of yellow fluorescence carbon Dots. Opt. Mater. 128, 112471 (2022).

Chandra, S., Laha, D., Pramanik, A., Ray Chowdhuri, A., Karmakar, P., & Sahu, S. K. Synthesis of highly fluorescent nitrogen and phosphorus doped carbon Dots for the detection of Fe3 + ions in cancer cells. Luminescence 31, 81–87 (2016).

Ding, H., Li, X. H., Chen, X. B., Wei, J. S., Li, X. B., & Xiong, H. M. Surface States of carbon Dots and their influences on luminescence. Journal Appl. Physics. 127, 231101 (2020).

Li, X., Zhang, S., Kulinich, S. A., Liu, Y. & Zeng, H. Engineering surface States of carbon Dots to achieve controllable luminescence for solid-luminescent composites and sensitive Be2 + detection. Sci. Rep. 4, 4976 (2014).

Rahmandoust, M., Sharifikolouei, E., Lassnig, A. & Zoghi, S. Study of the durability and sustainability of fluorescent nanosensors based on cellulose nanocomposites incorporated with various carbon Dots. Cellulose 30, 1031–1044 (2023).

Taheri, Z., Mirjalili, M. H., Shahsavarani, H., Ghassempour, A. & Rahmandoust, M. Single-step synthesized carbon quantum Dots from centella Asiatica hairy roots: Photoluminescent, biocompatibility, antibacterial and anticancer activity. Ind. Crops Prod. 229, 120999 (2025).

Kumar, P., Dua, S., Kaur, R., Kumar, M. & Bhatt, G. A review on advancements in carbon quantum Dots and their application in photovoltaics. RSC Adv. 12, 4714–4759 (2022).

Yan, F., Sun, Z., Zhang, H., Sun, X., Jiang, Y., & Bai, Z. The fluorescence mechanism of carbon dots, and methods for tuning their emission color: a review. Microchim. Acta. 186, 583 (2019).

Siddique, A. B., Pramanick, A. K., Chatterjee, S. & Ray, M. Amorphous carbon Dots and their remarkable ability to detect 2, 4, 6-trinitrophenol. Sci. Rep. 8, 9770 (2018).

Thangaraj, B., Solomon, P. R., Chuangchote, S., Wongyao, N. & Surareungchai, W. Biomass-derived carbon quantum dots–A review. Part 1: Preparation and characterization. ChemBioEng Rev. 8, 265–301 (2021).

Selvaraju, N., Ganesh, P. S., Palrasu, V., Venugopal, G. & Mariappan, V. Evaluation of antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity of citrus medica fruit juice based carbon Dots against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ACS Omega7, 36227–36234 (2022).

Chai, S., Zhou, L., Pei, S., Zhu, Z. & Chen, B. P-doped carbon quantum Dots with antibacterial activity. Micromachines 12, 1116 (2021).

Chai, S., Zhou, L., Chi, Y., Chen, L., Pei, S., & Chen, B. Enhanced antibacterial activity with increasing P doping ratio in CQDs. RSC Adv. 12, 27709–27715 (2022).

Li, P., Sun, L., Xue, S., Qu, D., An, L., Wang, X., & Sun, Z. Recent advances of carbon dots as new antimicrobial agents. SmartMat. 3, 226–248 (2022).

Sayyad, U. S., Waghmare, S. & Mondal, S. A proton-coupled electron transfer process from functionalized carbon Dots to molecular substrates: the role of pH. Nanoscale 16, 18468–18476 (2024).

Syamantak, K., Navneet, C. V., Prashant, G., Sanjhal, J., Souvik, G., & Nandi, C. K. Mechanistic insight into the carbon dots: protonation induced photoluminescence. J Mater. Sci. Eng. 7, 1000448 (2018).

Šafranko, S., Stanković, A., Hajra, S., Kim, H.J., Strelec, I., Dutour-Sikirić, M., Weber, I., Bosnar, M.H., Grbčić, P., Pavelić, S.K. & Széchenyi, A. Preparation of multifunctional N-doped carbon quantum Dots from citrus Clementina peel: investigating targeted Pharmacological activities and the potential application for Fe3 + sensing. Pharmaceuticals 14, 857 (2021).

Olia, F., Fiori, F. & Innocenzi, P. Antioxidant-oxidant dual action of carbon Dots obtained through thermal processing of citric acid. Next Mater. 8, 100756 (2025).

Bao, W., Ma, H., Wang, N. & He, Z. pH-sensitive carbon quantum dots – doxorubicin nanoparticles for tumor cellular targeted drug delivery. Polym. Adv. Technol. 30, 2664–2673 (2019).

Ahamed, A., Samaranayake, P., Silva, V. D., Kooh, M. R. R., Wickramage, N., Rajapaksha, I. G., & Thotagamuge, R. Unveiling the pH-Responsive mechanisms of the carbon Dot–Proximicin-A peptide conjugate for targeted cancer therapy using density functional theory. Molecules 30, 896 (2025).

Pleskova, S., Pudovkina, E., Mikheeva, E. & Gorshkova, E. Interactions of quantum Dots with donor blood erythrocytes in vitro. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 156, 384–388 (2014).

Wang, J., Zheng, X. & Zhang, H. Exploring the conformational changes in fibrinogen by forming protein Corona with CdTe quantum Dots and the related cytotoxicity. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 220, 117143 (2019).

Kotańska, M., Wojtaszek, K., Kubacka, M., Bednarski, M., Nicosia, N., & Wojnicki, M. The influence of caramel carbon quantum Dots and caramel on platelet aggregation, protein glycation and lipid peroxidation. Antioxidants 13, 13 (2023).

Ozdemir, N., Tan, G., Tevlek, A., Arslan, G., Zengin, G., & Sargin, I. Dead cell discrimination with red emissive carbon quantum Dots from the medicinal and edible herb echinophora tenuifolia. J Fluoresc. 1–18 (2025).

Hashempour, S., Ghanbarzadeh, S., Maibach, H. I., Ghorbani, M. & Hamishehkar, H. Skin toxicity of topically applied nanoparticles. Therapeut. Del. 10, 383–396 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fatemeh Sharifi Adel: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Pardis Sadat Mirseyed: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis. Sareh Arjmand: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Conceptualization. Moones Rahmandoust: Formal Analysis. Iraj Ashrafi Tamai : Formal Analysis. Manochehr Sadeghi: Formal Analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study did not involve patients, volunteers, or identifiable human data. The ESR assay was conducted solely using a blood sample voluntarily provided and self-collected by one of the co-authors as part of a minimal-risk, in vitro experiment. Informed consent was obtained from the researcher (self) prior to sample collection and documented for inclusion in the article’s records.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Declaration of generative AI in scientific writing

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT and Perplexity AIs in order to improve the language and readability of the manuscript. After using these tools, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adel, F.S., Mirseyed, P.S., Arjmand, S. et al. Sustainable carbon quantum dots synthesized from yeast β-glucan as a promising nanomaterial for biological applications. Sci Rep 16, 146 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28896-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28896-5