Abstract

Phosphorus (P) deficiency induced the formation and development of cluster roots in macadamia, thereby stimulating P acquisition by enhancing root surface area and carboxylate exudation. However, how P deficiency regulates the formation of cluster roots in macadamia remains unclear. Sand culture experiments were conducted to investigate the role of auxin in formation cluster roots induced by P deficiency. Our results demonstrated that P deficiency significantly triggered the formation of cluster roots in macadamia, as evidenced by an increase in the number, carboxylates exudation and acid phosphatase activity. These differences might be attributed to the accumulation and distribution of IAA in cluster roots induced by P deficiency, as demonstrated by the positive effect of IAA application and inhibitory effect of NPA. Our results provide valuable insights into the mechanisms of cluster roots formation stimulated by P deficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phosphorus (P) is an essential macronutrient for plant growth, development, and metabolism1,2. Low P availability in most soils, due to its high rate of chemical fixation by metal ions and extremely slows diffusion3,4, often limits plant growth and productivity in many agricultural ecosystems5,6. To cope with low soil P availability, plants have evolved diverse below-ground strategies to efficiently acquire P from soil7. One of the most important strategies for enhancing P acquisition includes root morphological modifications, involving higher root/shoot ratio, longer root length, more vigorous root branching, greater root hair length and others8,9.

Most Proteaceae members grow in soil environment with low P availability, such as in southwestern region of Australia and South Africa10 and have evolved specialized root structures-cluster roots11. Cluster roots, originally called “proteoid roots,” are a specialized lateral root structure in Proteaceae that enhance phosphorus acquisition in P-impoverished soils12. Previous studies have demonstrated that Proteaceae and white lupin formed a large number of cluster roots under low-P stress, which increases their root surface area13,14. Most importantly, cluster roots released a burst of carboxylates, primarily citrate and malate, which activated soil P sources3,15,16. Also, a substantial amount of acid phosphatases from cluster roots were released into the rhizosphere, where they hydrolyze soil organic P17. Cluster roots are ephemeral structures that generally live for about 20 d before senescing18. In white lupin, cluster roots released an exudative burst of citrate and malate at the mature stage, and then gradually decreased during the senescent period19.

Auxin, a class of the most important hormones primarily found as IAA in plants, affects root growth and development20, particularly the development of lateral roots21. IAA is also reportedly involved in regulating the formation and development of cluster roots22. Research on white lupin has revealed that the synthesis of endogenous auxin within the root system and its polar transport were crucial for the development of cluster roots under low-P stress22. Treatment with exogenous IAA significantly increased the number of cluster roots in white lupin, while the addition of auxin polar transport inhibitors (NPA or TIBA) inhibited their development23,24. Tang et al. added IAA to white lupin and also found that it could stimulate the development of lateral roots and the formation of cluster roots25. Consequently, the formation of cluster roots relied on auxin signal to a large extent.

Macadamia (Macadamia integrifolia), which belongs to Proteaceae, originated in Australia26, and is now widely distributed in southern China26. Macadamia exhibited a stronger adaptability in P-impoverished habitats by evolving cluster roots. The growth of macadamia cluster roots is bound up with the soil P concentration, depressing at high soil P levels27. Yue et al. conducted a hydroponics experiment and evaluated the status of cluster roots formation in macadamia seedlings under varying P concentration28. Moreover, excessive P supply inhibited the growth of macadamia trees29 and even caused leaf chlorosis30. Several studies have confirmed that overuse of P fertilizers triggered P-toxicity symptoms in Proteaceae, such as H. prostrate31 and Banksia ericifolia32.

The formation of cluster roots and their carboxylate exudation induced by P deficiency have been studied extensively in white lupin33,34, and many species of Proteaceae like Euplassa cantareirae35, Hakea prostrata36, and Grevillea crithmifolia37. Zhao et al. also observed this phenomenon in macadamia under P deficiency38. However, the mechanism underlying the effects of auxin (IAA) on P deficiency-induced cluster roots formation still needs to be determined. In this context, we conducted two sand culture experiments with varying P supplies and IAA/NPA application to test the hypothesis that P deficiency regulates the accumulation and distribution of auxin (IAA) in roots, and thus driving the formation of cluster roots in macadamia. This study aimed to offer new insights into the mechanism underlying cluster roots development and physiological functions for efficient P acquisition, thereby avoiding P overuse in macadamia cultivation.

Materials and methods

Test materials

The variety of Macadamia (Macadamia integrifolia L.) was ‘Guire No.1’, provided by the Guangxi South Subtropical Agricultural Science Research Institute. The tested sand was obtained from Nanning Baoshun Technology Co., Ltd.

Experimental design

Sand culture experiment 1

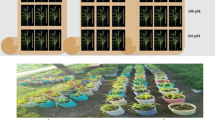

A sand culture experiment was conducted in a greenhouse at Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Guangxi (22°20′26″N, 106°47′31″E). Macadamia seeds of uniform size were selected and surface sterilized with 75% (vol/vol) alcohol for 10 min, and then soaked in distilled water for 24 h. The soaked seeds were planted in washed sand and watered with distilled water to encourage germination. Seedlings with six leaves were transplanted into pots filled with disinfected sand and watered with half-strength nutrient solution containing 50 µM P every other day for two weeks; after this, plants were watered with full-strength nutrient solution every other day for 10 d. There were six P application rates: 0, 5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 µM supplied as KH2PO4; the K concentration was the same in every treatment, because KH2PO4 was replaced by KCl. All other basal nutrients were provided as follows: 2000 µM Ca(NO3)2, 700 µM K2SO4, 600µM MgSO4, 100 µM KCl, 10 µM H3BO3, 1µM MnSO4, 1 µM ZnSO4, 0.1 µM CuSO4, 0.05µM (NH4)6Mo7O24 and 20 µM Fe-EDTA. The pot size was 7.8 L, and the initial pH of the nutrient solution was measured with a pH sensitive microelectrode and adjusted to 5.5 ~ 6.0 using diluted NaOH or HCl solution. The solution was renewed every 3 d. Each treatment was applied to six replicates and arranged in a completely randomized block design during the experimental period.

In the sand culture experiment, the temperature was maintained at 30 °C/25°C, with a 45% relative humidity, a 14 h/10 h photoperiod and a light intensity of 650 µmol∙m− 2∙s− 1. After four months of growth, plants were harvested and divided into roots and shoots. The number of cluster roots was recorded for each treatment. All plant samples were oven-dried at 75 °C to a constant weight for dry weight (DW) determination, and then the DW of shoot and root was weighed separately to calculate the root-to-shoot ratio. The dried materials were ground into a powder with a stainless-steel grinder to determine phosphorus concentration.

Sand culture experiment 2

In experiment 2, macadamia seedlings were treated with the exogenous auxin (naphthylacetic acid, NAA) and an inhibitor of polar transport of the hormone auxin (1-naphthylphthalamic acid, NPA) under conditions of P deficiency (5 μm) or P sufficiency (100 μm). It was determined that the most suitable concentration for adding exogenous NAA or NPA to the nutrient solution was 5 × 10− 6 mol/L through a series of concentration tests ranging from 10− 6~10− 8 mol/L, because the concentration could cause significant changes in cluster roots without affecting the plant growth.

Macadamia seeds were handled as in experiment 1. The seedlings with six leaves were watered with half-strength and full-strength nutrient solution for 14 d and 10 d respectively, as in experiment 1. 24 d after P treatment, macadamia seedlings showed a good growth and pre-dissolved NAA or NPA by dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added into the nutrient solution with the final concentration of 5 × 10− 6 mol/L, while other groups of plants had an equal volume of DMSO added. There were six treatments arranged in a complete randomized block design with 4 replicates of each treatment. Four months after growth, roots were harvested and the cluster roots of each plant were recorded.

Both experiments were conducted in a glasshouse at Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Guangxi (22°20′26″N, 106°47′31″E). Seedlings were grown in a same controlled environment with a light: dark regime of 14:10 h, a temperature of 30:25 °C and a light intensity of 650 µmol∙m− 2∙s− 1.

Measurements

Plant P concentration

Phosphorus concentration in shoots and roots were determined by the molybdovanadophosphate method39 at 440 nm by spectrophotometry (UV-2201, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) after digestion with a mixture of 5 mL concentrated H2SO4 and 2 mL 30% (v/v) H2O2.

Collection of root exudates and determination of carboxylates

For each treatment, 0.5 g of excised root segments was used to collect root exudates before harvesting the plants. We separately sampled the active white cluster roots segment (mature cluster roots) and root apices. Root samples were rinsed with deionized water four times to remove ions from their surface. Then roots were incubated in a centrifuge tube containing 3 mL of incubation medium for 2 h to collect exudates. The composition of the incubation medium was as follows (mM): MgCl2 (200), KCl (100), CaCl2 (600), and H3BO3 (5) and it was adjusted to the same pH as that of the nutrient solution with NaOH or HCl (5.5). After the collection of exudates, two drops of microbial inhibitor Micropur (Sicheres Trinkwasser, Munich, Germany) at 0.01 g L− 1 and two drops of concentrated H3PO4 were added to inhibit microbial degradation of root exudates.

Root exudates were filtered through sterile Millex® GS syringe filters (0.22 μm pore size) and stored at −20℃ until carboxylates analysis. Carboxylates in root exudates were analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system according to a previous report (modified from Zhang et al.40). The chromatographic separation was performed on a 250 × 4.6 mm reversed-phase column (Synergi 4u Hydro-RP 80 A). The mobile phase was 10 mmol L− 1 KH2PO4 (pH 2.45) with a flow rate of 1 mL min− 1 at 35 °C. Detection of carboxylates was performed at 214 nm.

Determination of Root-Released acid phosphatase activity (APase)

APase were extracted from root exudates by using enzymic reagents according to the manufacturers’ recommendations (www.geruisi-bio.com, China). Then, the absorbance of the resulting color was measured spectrophotometrically (UV-2201, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) at 405 nm. APase activity was defined as the amount of p-nitrophenol (PNP) produced by hydrolyzing 1 µg of p-nitrophenyl phosphate (PNPP) per hour per gram of fresh sample at 37 °C.

Determination of IAA concentration in cluster roots

To examine the effect of P deficiency on IAA production during cluster roots development, the cluster roots were divided into different developmental stage. We separately sampled 0.5 g of cluster roots segment at juvenile, mature and senescent stages, and the cluster roots at different developmental stages were differentiated as shown in Section “Results Fig. 5C”. IAA concentration in cluster roots was quantified using a UPLC-MS/MS system with electrospray ionization (ESI) in positive ion detection mode according to previous papers41,42. The chromatographic separation was conducted on a Acquity UPLC® HSS T3 C18 column (1.8 μm, 100 mm×2.1 mm i.d; Waters) with a gradient mobile phase system of ultrapure water with 0.04% acetic acid (A phase) and acetonitrile with 0.04% acetic acid (B phase). The flow rate of 0.35 mL min− 1 at 40 °C and the injection volume was 2 µL. Quantification was performed using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM).

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed statistically using SPSS statistical software (SPSS version 19.0, IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD were used to test the significance of differences among different P treatments (P < 0.05). The analysis results were expressed as the mean and standard deviation (SD). Data were analyzed by least squares fitting method and determined as nonlinear regression functions in Microsoft Excel 2016 (United States). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Plant growth and biomass allocation (Exp 1)

Macadamia plants produced more shoot biomass than root biomass in all treatments. Both shoot and root dry matter (DM) increased with increasing P supply, with no further increase from 0 to 5µM P or 50 to 100 µM P, and then growth was significantly inhibited at 200 µM P (Fig. 1 A). The highest root-to-shoot ratio was found at 0 µM P, with no obvious decline up to 25 µM P. However, this ratio significantly decreased at 50, 100 and 200 µM P treatments compared to low P supply (0–25 µM P), with no further decline from 25 to 100 µM P (Fig. 1B).

Partitioning of dry matter (A) and root/shoot ratio (B) of Macadamia integrifolia grown with different rates of phosphorus (P) supply. Plants were grown for four months at 0, 5, 25, 50, 100 and 200 μM P. Different lowercase or uppercase letters mean a significant difference among plants growth under different P supplies (P<0.05).

Plant P concentration and content (Exp 1)

As shown in Fig. 2A, phosphorus concentrations in shoots (ranging from 0.51 to 2.51 mg P g− 1 DW) and roots (ranging from 0.71 to 3.06 mg P g− 1 DW) increased with increasing P supply. The P content in shoots and roots also increased with increasing P supply from 0 to 100 µM P, but showed no further increase at 50 and 100 µM P, and then appeared a significant drop at 200 µM P (Fig. 2B). Additionally, there were no significant changes in P concentration and content in the shoots and roots from 0 to 5 µM P (Fig. 2 A, B).

Phosphorus supply affected cluster roots formation (Exp 1)

As shown in Fig. 3, macadamia plants developed the greatest number of cluster roots (produced 83 cluster roots per plant) at 5 µM P, while 79 per plant at 0 µM P, and there was no sharp change between 0 and 5 µM P. Subsequently, there was a downward trend in the number of cluster roots with increasing P supply from 25 to 200 µM P. At 25 µM P, the number of cluster roots was significantly decreased by 22.79% compared to 5 µM P treatment, and by 26.51% when compared to 0 µM P. The number of cluster roots at 50 and 100 µM P also was significantly lower than that in 0, 5 and 25 µM P, with no further decline from 50 to 100 µM P. Then, the number decreased to four per plant on average when phosphorus supply was 200 µM, which was significantly lowered than all other treatments.

Phosphorus supply changed cluster roots exudation (Exp 1)

We detected six carboxylates including malate, citrate, oxalate, tartrate, succinate and lactase using HPLC measurements. Malate and citrate were the major exudates in every treatment, and oxalate was only found in cluster roots at 0 µM P. As shown in Figs. 4A and B, cluster roots of plants grown without P supply exuded more citrate and malate compared to those in treatments with increasing P supply, although there was no significant difference from 0 to 5 µM P. The release of citrate and malate declined with increasing P supply, but showed a gradually-increasing trend with increasing IAA concentration in cluster roots (Figs. 4D, E). There was no significant difference in the both exudations between 50 and 100 µM P treatments, and then both exudations were significantly inhibited at 200 µM P. Similar to cluster roots, the most amounts of citrate and malate exuded by root apices was found at 0 µM P, significantly higher than those in treatments with P added, and decreased with increasing P supply. Moreover, the cluster roots of plants exuded more citrate than malate at all P supplies, and their exudation rates were faster than those of root apices (Figs. 4A, B).

The same trend was found between the acid phosphatases activity and carboxylates exudation (Fig. 4C). The activity of acid phosphatases in cluster roots and root apices showed a gradually- decreasing trend with increasing P supply, and the cluster roots released more acid phosphatases than that in root apices in all P treatments. Also, there was a significant positive correlation between the acid phosphatases activity and IAA concentration in cluster roots (Fig. 4F).

Effects of phosphorus (P) supply on root carboxylate exudation (A, B), and the activity of acid phosphatase (C) of Macadamia integrifolia. Relationships between carboxylates (D, E), acid phosphatase activity (F) and IAA concentration in cluster roots. Plants were grown for four months at 0, 5, 25, 50, 100 and 200 µM P. Different lowercase or uppercase letters denote a significant difference among P supplies (P < 0.05).

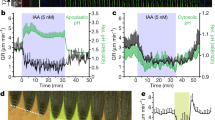

Phosphorus supply altered IAA concentrations in roots (Exp 1)

Root samples, including root apices and different developmental stages of cluster roots with increasing P supply (Fig. 5 C), were used for HPLC analysis of IAA. As shown in Figs. 5 A, the IAA concentration in juvenile cluster roots decreased with increasing P supply, and there were no significant changes between the 0 and 5 µM P treatments and between the 50 and 100 µM P treatments, but it sharply decreased at 200 µM P. In the mature cluster roots, the highest IAA concentration was found at 5 µM P, but there was no significant change between 0 and 5 µM P treatments, and then the concentration decreased from 25 to 200 µM P, with no significant decrease between 50 and 100 µM P. In the senescent cluster roots, the IAA concentrations did not significantly differ from 0 to 25 µM P, but they were significantly higher than those in 50, 100 and 200 µM P treatments; there was no significant difference in the concentration between 50 and 100 µM P treatments, but it was significantly depressed at 200 µM P. Meanwhile, the IAA concentration in root apices significantly decreased with increasing P supply, except for no significant decrease between 50 and 100 µM P. Furthermore, IAA exhibited a tissue-specific accumulation pattern in different root segments; the highest concentration was observed in mature cluster roots under P treatments of 0, 25, 50 and 100 µM P, while the highest concentration was found in root apices at 200 µM P. A significant positive correlation was observed between IAA concentration and the number of cluster roots (Fig. 5B).

Concentrations of IAA (A) at different developmental stages (B) of cluster roots at six P supplies, and relationship between cluster roots number and IAA concentration (C). Plants were grown for four months at 0, 5, 25, 50, 100 and 200 µM P. Different lowercase letters mean a significant difference among P supplies at the same stage(P < 0.05); Different uppercase letters denote a significant difference among three stages and root apices at the same P supply(P < 0.05).

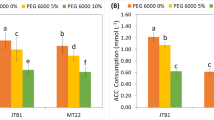

Effect of exogenous IAA on cluster roots growth (Exp 2)

The addition of exogenous auxin (NAA) or an inhibitor of polar auxin transport (NPA) also had a significant effect on the cluster roots development of macadamia (Fig. 3C). At 5 µM P, the number of cluster roots in macadamia treated with NAA significantly increased by 16.19%, while those treated with NPA significantly decreased by 26.32%. Also, P100 + NAA treatment significantly increased the number of cluster roots by 23.24% compared to 100 µM P (P100), whereas P100 + NPA treatment led to a significant decrease of 26.76%.

Discussion

Effects of external P supply on shoot P concentration and plant growth

This study exhibited that external P supply influenced biomass and growth of macadamia plants. Interestingly, we found that biomass of macadamia increased with increasing P supply, with no further increase from 50 to 100 µM P, and then showed a drop when P supply surpassed 100 µM P (Fig. 1 A), indicating a low P supply was better situated to the growth of macadamia plants. These findings of macadamia plant growth were supported by previous studies on Proteaceae, where the biomass enhanced with increasing P supply in a low P range, while it declined with further P supply due to P toxicity that damaged plants growth32,43. In this experiment, a supply of 200 µM P was not enough to cause obvious P-toxicity symptoms in macadamia plants, such as brown-gray necrosis on young leaves, but it did lead to a reduction in biomass.

Root to shoot ratio is an important strategy for plants to adapt P-impoverished environment7. In the present study, the root-to-shoot ratio of macadamia at a low P range of 0 to 25 µM was significantly greater than those in treatments with adequate P supply (surpassed 50 µM P) (Fig. 1B). Our findings were agreed with the results of previous studies on maize44, alfalfa45, and wheat46, where root/shoot ratio was elevated under P deficiency. These results suggested that macadamia plants also prioritized aboveground photosynthetic products to roots for their growth under low P deficiency, thereby increasing the root to shoot ratio to meet the nutrient needs47.

Effects of external P supply on cluster roots development and exudation

The formation and development of cluster roots is stimulated by P deficiency, and inhibited at a high P supply48. In our study, macadamia developed a large number of cluster roots at a low P range of 0–25 µM P, although some cluster roots were also observed in the treatment of P-sufficient plants (surpassed 50 µM P) (Fig. 3), indicating P deficiency stimulated the formation of cluster roots in macadamia. Our results were in reasonable agreement with results of Zhao et al.38on the formation of cluster roots, who also found that low P concentration (0–2.5.5 µM P) strongly stimulated formation and development of cluster roots in macadamia; however, the primary difference from this experiment was a lower supply of P, which was possibly due to the differences in cultivation substrate, variety and climate etc. Also, similar responses have been evidenced on the model plant such as white lupin, where low P supply significantly promoted cluster roots formatiom49,50. So, enhanced cluster roots formation is an important adaptive strategy for macadamia to cope with low-P stress environments, as it increases plants phosphorus acquisition by expanding the root surface area in the soils.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that cluster-root plants such as white lupin50,51 and most Proteaceae15, they could activate and utilize soil insoluble phosphorus by releasing a large amount of organic acids and acid phosphatases via cluster roots under low-P-stress. We observed that the exudation of citrate and malate by the cluster roots of macadamia was strongly enhanced under low-P supply (0–25 µM P), this in line with the results of Zhao et al., who have found that malate and citrate were the two dominant carboxylates in cluster roots exudates of macadamia38. Other studies on E. coccineum52 and H. prostrata53 also observed the same phenomenon. Nevertheless, high P levels (over 50 µM P) suppressed these exudations (Figs. 4A, B). These findings indicated that P deficiency probably enhanced many enzymes activity in processes of carbon metabolism and carboxylates biosynthesis in macadamia, thereby affecting the release of carboxylates in the cluster roots. Also, low P supply dramatically enhanced the activities of acid phosphatases released by cluster roots compared to treatments of adequate P addition (Figs. 4C), which in agreement with findings on white lupin19 and other species such as maize54 and soybean55, where P deficiency could strongly stimulate the activities of acid phosphatases in cluster roots or roots compared to adequate P supply. Interestingly, we also found that the exudation of carboxylates by cluster roots was approximately 2.1 ~ 3.6 times higher than that of root apices from 0 to 200 µM P, and 3.0 ~ 5.2 times higher in the activity of acid phosphatases (Figs. 4A, B and C). These above findings suggested that macadamia plants under low-P stress also released a substantial amount of carboxylates and acid phosphatases mainly through cluster roots to enhance P acquisition, as a typical cluster-root plant.

Effects of IAA distribution on cluster roots development

Root auxin is now recognized as a key signaling factor that drives plants to alter their root architecture in response to low-P stress56. Previous studies have confirmed that the formation of lateral roots is significantly dependent on the concentration and distribution of auxin within the roots57,58. Li et al. found that P deficiency enhanced the biosynthesis of IAA within the roots, thus inducing the development of lateral roots in maize59. Talboys et al. also observed that low-P stress caused the distribution of auxin in wheat roots, thus promoting the production of lateral roots60. Through a HPLC assays, we also observed that the higher concentration of IAA in root apices and different developmental stages of cluster roots in macadamia under low P supply (0–25 µM P) than that in P-sufficient treatments (50–200 µM P) (Fig. 5 A), suggesting that the accumulation of auxin in root parts of macadamia as upregulated by P deficiency. Localized distribution of IAA was also developmentally regulated and mainly located in mature and juvenile cluster roots, as well as root apices, suggesting that macadamia plants adjusted IAA distribution in roots in response to P deficiency. Therefore, IAA also played a positive role in regulating the development of cluster roots, a specialized type of lateral roots, in macadamia.

The development of lateral roots was also affected by the polar transport of IAA, as it determined the concentration and distribution of auxin within the roots61. For example, the synthesis of endogenous auxin and its polar transport were pivotal for P deficiency-induced cluster roots formation on white lupin22. This was supported by studies on white lupin, where cluster roots formation is promoted by auxin application (NAA) and suppressed by auxin transport inhibitors (NPA)24. Further studies showed that cluster roots development in white lupin involved a specific expression profile of auxin-related genes associated with synthesis, transport and signaling; these genes, including LaTIR1b (transport inhibitor response 1b), LaARF5 (auxin response factor 5) and LaIAA14 (auxin/indole-3-acetic acid repressors), were regulated by P deficiency62,63. In our experiment, application of exogenous NPA also strongly inhibited the formation of cluster roots in macadamia plants, regardless of P supply levels; conversely, the addition of exogenous IAA significantly increased the number of cluster roots (Fig. 6), suggesting a certain concentration of IAA was required for cluster roots development in macadamia, which might be linked to local accumulation of IAA during cluster roots development under P deficiency. Additionally, we observed a significant positive correlation between IAA concentration and the number of cluster roots (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these findings implied that the accumulation and distribution of IAA in roots as affected by P deficiency regulated the formation of cluster roots in macadamia. However, the roles of these genes related to auxin synthesis, transport and signalling in P-deficiency-induced cluster-root formation in macadamia remains unclear and further studies are needed.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that P deficiency significantly enhanced the cluster roots formation and its exudation of carboxylates and acid phosphatases in macadamia. The accumulation and distribution of IAA in different stages of cluster roots regulated by P deficiency was involved in the formation of cluster roots in macadamia. The IAA concentration was positively associated with the number of cluster roots. Our results would provide valuable insights into the mechanisms of P-deficiency-induced cluster-root formation.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed in this study are within the manuscript.

References

Gutiérrez-Alanís, C. et al. Adaptation to phosphate scarcity: tips from Arabidopsis roots. Trends Plant. Sci. 23, 721–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2018.04.006 (2018).

Cong, W. F., Suriyagoda, L. & Lambers, H. Tightening the phosphorus cycle through phosphorus- efficient crop genotypes. Trends Plant. Sci. 25, 967–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2020.04.013 (2020).

Shen, J. B. et al. Phosphorus dynamics: from soil to plant. Plant. Physiol. 156, 997–1005. https:// (2011).

Carstensen, A. et al. The impacts of phosphorus deficiency on the photosynthetic electron transport chain. Plant. Physiol. 177, 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.17.01624 (2018).

Johnston, A. E., Poulton, P. R., Fixen, P. E. & Curtin, D. Phosphorus: its efficient use in agriculture. Adv. Agron. 123, 177–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-420225-2.00005-4 (2014).

Su, M. et al. Phosphorus deficiency in soils with red color: Insights from the interactions between minerals and microorganisms. Geoderma 404, 115311. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GEODERMA.2021 (2021).

Wen, Z. H. et al. Tradeoffs among root morphology, exudation and mycorrhizal symbioses for phosphorus-acquisition strategies of 16 crop species. New Phytol. 223, 882–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15833 (2019).

Wen, Z. H., Li, H. G., Shen, J. B. & Rengel, Z. Maize responds to low shoot P concentration by altering root morphology rather than increasing root exudation. Plant. Soil. 416, 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-017-3214-0 (2017).

Haling, R. E. et al. Differences in nutrient foraging among Trifolium subterraneum cultivars deliver improved P-acquisition efficiency. Plant. Soil. 424, 539–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-017-3511-7 (2018).

Tian, T. L. et al. Effect of glomus intraradices on root morphology, biomass production and phosphorous use efficiency of Chinese Fir seedlings under low phosphorus stress. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 1095772. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPLS.2022.1095772 (2023).

Gomes, C. A. et al. Genome-wide association study for root morphology and phosphorus acquisition efficiency in diverse maize panels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 6233. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJMS240762 (2023).

Lambers, H., Brundrett, M. C., Raven, J. A. & Hopper, S. D. Plant mineral nutrition in ancient landscapes: high plant species diversity on infertile soils is linked to functional diversity for nutritional strategies. Plant. Soil. 348, 7–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-010-0444-9 (2010).

Muller, K. et al. Proteaceae species show different strategies for phosphorus acquisition and utilization in P poor soils in the Mediterranean-type fynbos ecosystem. Flora 306, 152362. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FLORA.2023.152362 (2023).

Gallardo, C. et al. Anatomical and hormonal description of rootlet primordium development along white lupin cluster root. Physiol. Plant. 165, 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppl.12714 (2019).

Lambers, H., Raven, J. A., Shaver, G. R. & Smith, S. E. Plant nutrient acquisition strategies change with soil age. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2007.10.008 (2008).

Wang, Z., Shen, J., Ludewig, U. & Günter, N. A re-assessment of sucrose signaling involved in cluster-root formation and function in phosphate-deficient white lupin (Lupinus albus). Physiol. Plant. 154, 407–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppl.12311 (2015).

Lambers, H. et al. The pattern of carboxylate exudation in Banksia grandis (Proteaceae) is affected by the form of phosphate added to the soil. Plant. Soil. 238, 111–122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A (2002).

Krishnapriya, V. & Pandey, R. Root exudation index: screening organic acid exudation and phosphorus acquisition efficiency in soybean genotypes. Crop Pasture Sci. 67, 1096–1109. https://doi.org/10.1071/CP15329 (2016).

Delgado, M. et al. Cluster roots of Embothrium coccineum (Proteaceae) affect enzyme activities and phosphorus ability in rhizosphere soil. Plant. Soil. 395, 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s 11104-015-2547-9 (2015).

Shane, M. W. & Lambers, H. Cluster roots: a curiosity in context. Plant. Soil. 274, 101–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-015-2547-9 (2005).

Neumann, G. et al. Physiological aspects of cluster root function and development in phosphorus- deficient white lupin (Lupinus albus L). Ann Bot 85, 909–919. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.2000.1135 (2000).

Meng, F. et al. Molecular mechanisms of root development in rice. Rice 12, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-018-0262-x (2019).

Teixeira, J. A. S. & Tusscher, K. H. The systems biology of lateral root formation: connecting the Dots. Mol. Plant. 12, 784–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2019.03.015 (2019).

Gilbert, G. A., Knight, J. D., Vance, C. P. & Allan, D. L. Proteoid root development of phosphorus deficient lupin is mimicked by auxin and phosphonate. Ann. Bot. 85, 921–928. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.2000.1133 (2000).

Meng, Z. B. et al. Root-derived auxin contributes to the phosphorus-deficiency-induced cluster-root formation in white lupin (Lupinus albus). Physiol Plantarum. 148, 481–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01715.x (2013).

Zhu, Y. Y. et al. Relationships between auxin, miR164 and development of proteoid roots of white lupin under P deficiency. Acta Bot. Boreal -Occident Sin. 30, 317–322 (2010). https://doi.org/CNKI:SU N:DNYX.0.2010-02-015.

Wang, Z. et al. Hormonal interactions during cluster-root development in phosphate-deficient white lupin (Lupinus albus L). J. Plant. Physiol. 177, 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2014.10.022 (2015).

Tang, H. L., Shen, J. B., Zhang, F. S. & Zed, R. Interactive effects of phosphorus deficiency and exogenous auxin on root morphological and physiological traits in white lupin (Lupinus albus L). Sci. China Life Sci. 43, 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-013-4461-9 (2013).

Hue, N. V. Iron and phosphorus fertilizations and the development of proteoid roots in macadamia (Macadamia integrifolia). Plant. Soil. 318, 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-008-9820-0 (2009).

Zhao, X. et al. Rhizosphere processes and nutrient management for improving nutrient-use efficiency in macadamia production. HortScience 54, 603–608. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI13643-18 (2019).

Xiao, X. M. et al. Difference of root exudates from macadamia seedlings under different phosphorus supply. Chin. J. Trop. Crops. 35, 261–265. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-2561.2014.02.00 (2014).

Yue, H. et al. Cluster root production and P utilization of macadamia seedling under different P treatments. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 18, 753–757. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1011.2010.00753 (2010). (2010).

Aitken, R. L. et al. Phosphorus Fertilizer Requirements for Macadamia. Final Report To the Australian Macadamia Society and Horticultural Research and Development Corporation (Dept. of Primary Industries, 1993).

Gallagher, E. et al. Macadamia Problem Solver and Bug Identifier pp41–55 (Department of Primary Industries, 2003).

Parks, S. E., Haigh, A. M. & Cresswell, G. C. Stem tissue phosphorus as an index of the phosphorus status of Banksia ericifolia L. Plant. Soil. 227, 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026563926187 (2000).

Shane, M. W., McCully, M. E. & Lambers, H. Tissue and cellular phosphorus storage during development of phosphorus toxicity in Hakea prostrate (Proteaceae). J. Exp. Bot. 55, 1033–1044. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erh111 (2004).

Li, H. G. et al. Is there a critical level of shoot phosphorus concentration for cluster-root formation in Lupinus albus? Funct. Plant. Biol. 35, 328–336. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP07222 (2008).

Cheng, L. Y. et al. Interactions between light intensity and phosphorus nutrition affect the phosphate-mining capacity of white lupin (Lupinus albus L). J. Exp. Bot. 65, 2995–3003. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/eru135 (2014).

Costa, P. B. et al. Cluster-root formation and carboxylate release in Euplassa Cantareirae (Proteaceae) from a Neotropical biodiversity hotspot. Plant. Soil. 2, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-015-2630-2 (2016).

Shane, M. W. et al. Effects of external phosphorus supply on internal phosphorus concentration and the initiation, growth and exudation of cluster roots in Hakea prostrata. Plant. Soil. 248, 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022320416038 (2003).

Shane, M. W. & Lambers, H. Systemic suppression of cluster-root formation and net P-uptake rates in Grevillea crithmifolia at elevated P supply: a proteacean with resistance for developing symptoms of ‘P toxicity’. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 413–423. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erj004 (2006).

Zhao, X. et al. Leaf phosphorus concentration regulates the development of cluster roots and exudation of carboxylates in macadamia integrifolia. Front. Plant. Sci. 11, 610591. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.610591 (2021).

Zhang, D. S. et al. Neighbouring plants modify maize root foraging for phosphorus: coupling nutrients and neighbours for improved nutrient-use efficiency. New. Phytol. 226, 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16206 (2020).

Zhang, D. S. et al. Increased soil phosphorus availability induced by Faba bean root exudation stimulates root growth and phosphorus uptake in neighbouring maize. New. Phytol. 209, 823–831. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13613 (2016).

Niu, K. et al. Simultaneous quantitative determination of major plant hormones in Pear flowers and fruit by UPLC/ESI-MS/MS. Anal. Methods. 6, 1766. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3ay41885e (2014).

Floková, K. et al. UHPLC-MS/MS based target profiling of stress-induced phytohormones. Phytochemistry 105, 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.05.015 (2014).

Hopper, M., Pearse, S. J., Oliveira, R. S. & Lambers, H. Downregulation of net phosphorus-uptake capacity is inversely related to leaf phosphorus-resorption proficiency in four species from phosphorus impoverished environment. Ann. Bot. 111, 445–454. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcs299 (2013).

Zhou, T. et al. Light intensity influence maize adaptation to low P stress by altering root morphology. Plant. Soil. 447, 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-019-04259-8 (2020).

Pan, X. Y. et al. Response of root morphology and anatomical structure of six Alfalfa cultivars to phosphorus deficiency. Acta Agrestia Sin 29, 2494–2504. https://doi.org/10.11733/j.issn.1007-0435.2021.11.015 (2021).

Wang, S. P. et al. Morphological characteristics and apase activity of wheat roots under low phosphorus stress. J. Gansu Agric. Univ. 56, 69–76. https://doi.org/10.13432/j.cnki.jgsau.2021.05.010 (2021).

Tang, R. L. et al. Effects of low phosphorus stress on growth and physiological characteristics of pepper at seedling stage. SW China J. Agr Sci. 33, 1933–1942. https://doi.org/10.16213/j.cnki.scjas.2020.9.009 (2020).

Lambers, H. et al. Phosphorus nutrition in proteaceae and beyond. Nat. Plants. 1, 15109. https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2015.109 (2015).

Neumann, G., Massonneau, A., Martinoia, E. & Rmheld, V. Physiological adaptations to phosphorus deficiency during proteoid root development in white lupin. Planta 208, 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004250050572 (1999).

Olt, P., Ding, W. & Ludewig, S. U. The LaCLE35 peptide modifies rootlet density and length in cluster roots of white lupin. Plant. Cell. Environ. 47, 1416–1431. https://doi.org/10.1111/PCE (2024).

Tomasi, N. et al. Plasma membrane H+-ATPase dependent citrate exudation from cluster roots of phosphate-deficient white lupin. Plant Cell Environ. 32, 465–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01938.x (2009).

O’Sullivan, J. B. et al. Elevated CO2 and phosphorus deficiency interactively enhance root exudation in Lupinus albus L. Plant. Soil. 465, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-021-04991-0 (2021).

Delgado, M. et al. Divergent functioning of proteaceae species: the South American Embothrium coccineum displays a combination of adaptive traits to survive in high-phosphorus soils. Funct. Ecol. 28, 1356–1366. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12303 (2014).

Shane, M. W. et al. Developmental physiology of cluster root carboxylate synthesis and exudation in harsh hakea. Expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase and the alternative oxidase. Plant. Physiol. 135, 549–560. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.103.035659 (2004).

Lucas, L. E. S., Andrade, J. A. D. C., Maltoni, K. L. & Lannes, L. S. Potential of root acid phosphatase activity to reduce phosphorus fertilization in maize cultivated in Brazil. PloS One. 18, 0292542. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0292542 (2023).

Tantriani., Cheng, W., Oikawa, A. & Tawaraya, K. Phosphorus deficiency alters root length, acid phosphatase activity, organic acids, and metabolites in root exudates of soybean cultivars. Physiol. Plant. 175, 14107–14107. https://doi.org/10.1111/PPL.14107 (2023).

Yuan, H. & Liu, D. Signaling components involved in plan responses to phosphate starvation. J. Integr. Plant. Biol. 50, 849–859. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00709.x (2008).

Himanen, K. et al. Auxin-mediated cell cycle activation during early lateral root initiation. Plant. Cell. 14, 2339–2351. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.004960 (2002).

Song, Y. J. et al. Dose-dependent sensitivity of Arabidopsis Thaliana seedling root to copper is regulated by auxin homeostasis. Environ. Exp. Bot. 139, 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.04.003 (2017).

Li, Z. X. et al. Phosphate starvation of maize inhibits lateral root formation and alters gene expression in the lateral root primordium zone. BMC Plant. Biol. 12, 89–105. http://dx.doi.org/10.11 86/1471-2229-12-89 (2014).

Talboys, P. J., Healey, J. R., Withers, P. J. & Jones, D. L. Phosphate depletion modulates auxin transport in Triticum aestivum leading to altered root branching. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 5023–5032. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/eru284 (2014).

Lopez-Bucio, J. et al. Phosphate availability alters architecture and causes changes in hormone sensitivity in the Arabidopsis root system. Plant. Physiol. 129, 244–256. https://doi.org/10.110 4/pp.010934 (2002).

Hufnagel, B. et al. High-quality genome sequence of white lupin provides insight into soil exploration and seed quality. Nat. Commun. 11, 492. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019- (2020).

Xu, W. et al. The genome evolution and low phosphorus adaptation in white lupin. Nat. Commun. 11, 1069. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14891-z (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences Basic Scientific Research Business Special Project (Gui Nong Ke 2023YM08, Gui Nong Ke 2025YP113), Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (2025GXNSFBA069115), Guangxi Science and Technology Base and Talent Special Project (Gui Ke AD22036008) and Technological Vanguard of Featured Fruits Industry (Gui Nong Ke Meng 202504).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.M.Q. and S.F.Z. conceived and conducted the experiments, as corresponding authors, contribute equally to this work. H.N.P. and X.J.H. performed the data analyses and wrote the manuscript. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, H., Huan, X., Wang, W. et al. IAA was involved in phosphorus deficiency-induced cluster roots formation in Macadamia integrifolia. Sci Rep 15, 45311 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28906-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28906-6