Abstract

This study developed an electrochemical biosensor utilizing a polydopamine film for the highly selective, ultrasensitive, and efficient determination of E. coli. A nanocomposite containing a magnetic graphene oxide-ionic liquid-palladium (MGO-IL-Pd) was synthesized and used as a chemical modifier to create a modified glassy carbon electrode (MGCE). Subsequently, dopamine was deposited on the GCE as a monomer during the electropolymerization process to prepare a bacteria imprinted polymer (BIP). After removing the E. coli as a template, the MGCE was employed for detecting the bacteria. The electrochemical performance of the BIP-based sensor was studied through square wave voltammetry (SWV) and cyclic voltammetry (CV). When E. coli was introduced, a significant current shift was observed, indicating bacterial entry into the BIPs’ cavities. The biosensor successfully detected E. coli over a wide concentration range of 5.0 to 1.0 × 10⁷ CFU/mL, with a low detection limit of 1.5 CFU/mL. The biosensor’s performance was compared to a non-bacteria imprinted polymer (NBIP) control, revealing a significant synergistic enhancement in detection signal due to the selective BIP cavities. Under optimum conditions, the sensor can be effectively applied to determine E. coli in human urine and serum samples with high precision and excellent recovery percentages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Food safety issues arising from contamination by foodborne pathogens have become a major global concern. Annually, foodborne illnesses result in more than 400,000 deaths worldwide1. Prominent pathogens contributing to these illnesses comprise Escherichia coli (E. coli), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Salmonella, and Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes)2,3. Among the diarrheal pathogenic bacteria, contamination of food and water by E. coli is pervasive4. This bacterium naturally inhabits the intestines of warm-blooded animals and is a key indicator of fecal contamination in drinking and recreational water. Consequently, developing rapid detection methods for E. coli is vital for public health and safety5. Traditional E. coli detection methods like quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), mass microscopy, flow cytometry, and immunoassays require costly lab equipment, complex preparation, and trained professionals6,7. While culture-based methods remain the gold standard for pathogen detection, they are notoriously time-consuming, often requiring several days for conclusive results, which is a critical drawback during outbreak investigations8. Alternative techniques like qPCR and ELISA offer improved speed but rely on sophisticated instrumentation, specialized reagents, and skilled personnel, making them less suitable for rapid, on-site testing6,7. Consequently, there is a pressing need for the development of analytical platforms that combine rapidity, high sensitivity, and operational simplicity for effective food and water quality monitoring9. Electrochemical sensors are gaining attention for detecting foodborne pathogens due to their affordability, miniaturization, and simplicity10.

Electrochemical sensors use electrodes with biological receptors like aptamers, antibodies, and enzymes to selectively bind pathogens, causing detectable changes in electrical properties11.

The performance of electrochemical sensors is profoundly influenced by the modifier type used on the working electrode. Various modifiers, including imprinted polymers12,13,14, magnetic nanoparticles15, nanoclusters16, quantum dots17,18, and metal-organic frameworks19,20, are extensively employed to increase the active surface area, enhance conductivity, and facilitate electron transfer, thereby boosting sensitivity21,22. Among these, graphene oxide (GO) provides an excellent modifier due to its large specific surface area and conductivity. When functionalized with magnetic nanoparticles (e.g., Fe3O4), it enhances the surface area as well as electron transfer kinetic15,23. Moreover, as advanced modifiers, molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) were also used to enhance the electrode surfaces in sensors, improving selectivity for the analyte detection13,14,24. However, to achieve both high sensitivity and selectivity, the combination of nanocomposite modifiers with MIPs presents a promising strategy. On the other hands, various metal nanoparticles, including gold25, copper26, palladium27, and silver nanoparticles28, are also used to coat surfaces and enhance electrochemical signals, boosting sensor sensitivity. However, the incorporation of ionic liquids (ILs) can improve the dispersion of nanomaterials and create a favorable ionic microenvironment, while noble metal nanoparticles like palladium (Pd) significantly enhance electrocatalytic activity and signal amplification27,29. Therefore, designing a ternary nanocomposite that synergistically combines these components-such as magnetic graphene oxide, an ionic liquid, and palladium nanoparticles (MGO-IL-Pd)- presents a promising strategy for developing highly sensitive sensing platforms.

To effectively integrate such nanocomposite modifiers with a selective MIP recognition element on the electrode surface, a reliable and controllable deposition method is required30. Electropolymerization rapidly synthesizes uniform polymer films on electrodes, ideal for insulating monomers like dopamine, which oxidizes to form polydopamine (PDA)31,32. PDA’s adhesion, biocompatibility, and biomolecule attachment make it a versatile linker in sensing33. Researchers utilize electropolymerization to fabricate controllable PDA films for sensor applications. For example, Chen et al. developed a PDA-based biosensor for E. coli detection34, while Roushani et al. fabricated a new MIP for selective and sensitive asulam detection31.

In this study, a novel electrochemical biosensor was developed for the ultrasensitive and selective detection of E. coli by integrating a bacteria-imprinted polymer (BIP) film with a designed magnetic graphene oxide-ionic liquid-palladium (MGO-IL-Pd) nanocomposite. The MGO-IL-Pd nanocomposite was first synthesized and characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), vibrating sample magnetization (VSM), thermal analysis, and X-ray diffraction (XRD). Then, the polydopamine matrix was formed via electropolymerization in the presence of E. coli, creating highly selective recognition sites following template removal. It is hypothesized that the synergistic effect between the high-affinity BIP cavities and the enhanced electrocatalytic properties of the nanocomposite overcomes the sensitivity limitations of previous BIP sensors.

Experimental

Materials and reagents

All chemicals used in this study, iron (III) chloride (FeCl3.6H2O 99%), tetramethoxysilane (TMOS,99%), including iron (II) chloride (FeCl2.4H2O 99%), (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane(APTES, 98%), graphite powder, benzaldehydes (97–99%), palladium acetate (98%), dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), ethanol, and toluene, were sourced from Fluka, Merck, and Sigma-Aldrich Companies. Dopamine and [Fe (CN)6]3−/4− were utilized as received, without any additional purification, while all other reagents were sourced from Merck Company. Three bacterial strains, E. coli, S. aureus, and Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epidermidis), and one fungal strain, Candida albicans (C. albicans), were used in this study.

Instruments and measurements

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were obtained using an ISP-Korea microscope to analyze the surface morphology of all electrodes. The particle morphology was examined with a SIGMA VP field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) from Germany. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) was performed using a SAMX EDS instrument from France. Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy was conducted with a Bruker-Vector 22 spectrometer, also from Germany. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed using a Bruker D8 ADVANCE diffractometer. Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted with a Netzsch PC/PG apparatus from Germany. Lastly, the magnetic properties were evaluated using a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) manufactured by the Meghnatis Daghigh Kavir Company in Iran.

All electrochemical experiments were performed using a potentiostat/galvanostat Autolab/PGSTAT101 (Metrohm, Switzerland) coupled with the advanced NOVA software. A standard three-electrode system was employed, consisting of a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) with a diameter of 2 mm as the working electrode, a platinum electrode as the auxiliary electrode, and an Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference electrode. Measurements were performed using cyclic voltammetry (CV) and square wave voltammetry (SWV) techniques in a solution containing 5 mmol L⁻¹ [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− and 0.1 mol L− 1 KCl as the redox probe. The CV experiments were conducted over a potential range of − 0.3 to + 0.8 V at a scan rate of 0.1 V⋅s⁻¹. In the SWV techniques, the potential parameters ranged from 0.0 to + 0.8 V. Additionally, dopamine was electrochemically polymerized over a range of − 0.5 to + 0.5 V at a scan rate of 40 mV⋅s⁻¹. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were conducted using a Radstat 10 workstation (Kianshar Danesh, Iran), in a solution containing 5.0 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− and 0.1 M KCl, with a frequency range of 0.05 Hz to 80 kHz and an amplitude of 10 mV.

Methods

Bacteria preparation

First, each bacterium’s fresh colony was cultured on the culture medium. Then, it was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The culture concentration was adjusted to 107 CFU/mL. Then, serial concentrations of 101 to 107 bacteria were prepared and used for sensor studies35.

Synthesis of MGO–IL–Pd nanocomposite

Initially, 0.25 g of graphene oxide (GO) was dispersed in 10 mL of water for 20 min. Then, 0.5 g of Fe3O4@SiO236 was added, and the mixture was heated to 70 °C. During vigorous stirring for 3 h, 250 µL of (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES) was added dropwise. The product, Fe3O4@SiO2–NH/GO, was magnetically separated, washed with ethanol, and dried at 70 °C for 6 h.

Next, 0.5 g of Fe3O4@SiO2–NH/GO was mixed with 25 mL of toluene, and 0.25 mmol of 1-methyl-3-(3-trimethoxysilylpropyl) imidazolium chloride was added. The mixture was refluxed for 24 h and then magnetically separated, washed, and dried to yield Fe3O4@SiO2–NH/GO–IL. Finally, 0.5 g of Fe3O4@SiO2–NH/GO–IL was dispersed in 20 mL of DMSO, and 0.7 mmol of Pd(OAc)2 was added. After stirring for 24 h, the material was magnetically separated, washed, and dried to produce MGO–IL–Pd (Scheme 1).

Fabrication of the BIP-based biosensor

Initially, the GCE was polished using alumina powder and then sonicated in a water-ethanol mixture to achieve a clean surface. The bare GCE was prepared through the electropolymerization of dopamine monomer, as described in the referenced literature35. The electropolymerization conditions were optimized using a phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.4) containing 0.22 mM dopamine and E. coli at a concentration of 10⁴ CFU mL⁻¹. The mixture was degassed with nitrogen for 5 min to remove dissolved oxygen. Electropolymerization was performed via CV for 10 cycles, within a potential range of − 0.5 to 0.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl), at a scan rate of 0.04 V s⁻¹. After polymerization, the electrodes were thoroughly rinsed with triple-distilled water and immersed in a leaching solution (0.01 M SDS in triple-distilled water) for 15 min under stirring to remove the E. coli template. For comparative analysis, a non-bacteria imprinted polymer (NBIP) electrode was fabricated using the same procedure but without the E. coli template.

For the preparation of the BIP/MGCE, all conditions remained identical to those used for the BIP/MGCE, except for the addition of 0.001 g of the modifier (MGO–IL–Pd) to the solution containing the buffer and analyte. The modifier was fully dispersed before electropolymerization was carried out. This step ensured the incorporation of the MGO–IL–Pd nanocomposite into the polymer matrix, enhancing the sensor’s electrochemical properties and sensitivity. This detailed fabrication process underscores the precision and robustness of the biosensor design, ensuring high performance for E. coli detection. Notably, employing the MGO–IL–Pd nanocomposite as a chemical modifier can enhance dopamine electropolymerization through two primary mechanisms: (1) Pd nanoparticles dispersed on MGO sheets can provide catalytic sites that may lower the oxidation overpotential and increase reaction rates, while (2) the IL component may enhance ionic conductivity and charge transfer efficiency. Furthermore, the high surface area of MGO can promote dopamine monomer adsorption, potentially leading to higher local concentrations and faster polymerization initiation37,38.

Preparation of real samples

Bacteria can be contagious within the human body, so blood serum and urine samples were analyzed to evaluate the performance of a biosensor for detecting E. coli. The human blood and urine samples utilized in this study were obtained as residual diagnostic specimens from Dr. Doustimotlagh Pathology Laboratory (Yasouj, Iran). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was approved by the Dr. Doustimotlagh Pathology Laboratory (Yasouj, Iran). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardians prior to participation in the study. All samples were fully anonymized and contained no personally identifiable information.

To prepare a healthy human serum sample, we added 2% methanol (v/v) to precipitate and separate the proteins. The mixture was shaken for 30 s and then centrifuged for 10 min at 5000 rpm. The clear supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.22 μm filter to obtain protein-free serum39.

For the urine sample, we collected 10 mL and centrifuged it for 15 min at 2500 rpm. The supernatant was then passed through a 0.22 μm filter to remove suspended particles and other interfering substances. Finally, each filtered sample was diluted with phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 and 0.1 M. The pH was adjusted, and the samples were spiked with various concentrations of E. coli for the biosensor improvement experiments40.

Results and discussion

Characterization of MGO–IL–Pd

It is worth noting that the comparative characterization of Fe3O4, graphene oxide, and MGO–IL–Pd using different techniques, including FT-IR, SEM/EDS, simultaneous thermal analysis (TGA and DTA), XRD, and VSM of Fe3O4@SiO2 and MGO–IL–Pd nanocomposite, was provided in our previous report46. However, the characterization results of MGO–IL–Pd as the final chemical modifier used in this research are presented in Fig. S1.

The crystalline structures analysis of the MGO–IL–Pd nanocomposite using XRD technique (Fig. S1e), exhibited eight well-defined peaks at 2θ values of 18.3°, 30.3°, 35.6°, 43.3°, 53.7°, 57.4°, 63°, and 74.3°, which corresponded to the (1 1 1), (2 2 0), (3 1 1), (4 0 0), (4 2 2), (5 1 1), (4 4 0), and (5 3 3) crystallographic planes, respectively. The pattern closely matches the Fe3O4 standard reference (JCPDS card, file no. 19–0629)41,42,43, indicating that the Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles maintained their crystalline structure during the modification process44,45.

The FT-IR spectrum of MGO–IL–Pd nanocomposite was provided in Fig. S1. As can be seen, a broad peak is observed at 3420 cm− 1, which is due to the O–H bonds present on the surface of the materials. The signals located at 2830 and 2955 cm− 1 in the MGO–IL–Pd spectrum correspond to the C–H bonds in the IL-propyl groups. Additionally, peaks at 1750, 1635, and 1100 cm− 1 are associated with the carboxyl C = O, aromatic C = C, and C–O bonds in GO, respectively. Furthermore, the peaks observed at 1100 and 540 cm− 1 can be attributed to the Si–O–Si and Fe–O bonds in the MGO–IL–Pd nanocomposite.

The FE-SEM analysis of MGO–IL–Pd nanocomposite (Fig. S1b) revealed nanoparticles with sizes on the nanometer scale. The particle size of the nanocomposite is estimated to be in the range of 20–100 nm. The particles exhibited a uniform or irregular shape, suggesting a spherical or polygonal morphology, respectively. The overall morphology of the nanocomposite indicated that the nanoparticles were aggregated or clustered, forming larger structures. The presence of nitrogen (N), oxygen (O), carbon (C), silicon (Si), iron (Fe), and palladium (Pd) in the synthesized MGO–IL–Pd nanocomposite was confirmed by EDS analysis in our previous work46.

The thermal stability of the MGO–IL–Pd nanocomposite was assessed through TGA analysis (Fig. S1). The TGA findings revealed three distinct weight loss stages occurring at 10–150 °C, 152–225 °C, and 230–580 °C. The initial loss of weight, occurring between 10 and 150 °C, corresponds to the evaporation of solvent from the nanocomposite’s surface. The subsequent loss of weight, observed from 151 to 225 °C, is due to the release of bound organic components (ionic liquid and propyl amine) from the structure of the nanocomposite. Lastly, the third loss of weight noted at temperatures exceeding 230 °C is linked to the expulsion of residual ionic liquids and the breakdown of GO components. Besides, the magnetic properties of the synthesized MGO–IL–Pd nanocomposites were studied via VSM analysis, which indicated the saturation magnetization values of 37 emu g−1 (Fig. S1d).

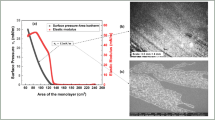

MGO–IL–Pd/MGCE characterization

The morphological features of the modified electrodes were examined sequentially using SEM. In Fig. 1a, it is evident that the electrode’s surface is clear of any substances. Figure 1b illustrates the presence of a uniformly distributed BIP film covering the electrode. Figure 1c depicts the binding of the target bacteria to the polymeric surface. After rinsing the modified electrode, Fig. 1d reveals the emergence of pores on its surface. Additionally, Fig. 1e highlights the strong adhesion of bacteria to the modified electrode’s surface.

Electrochemical study of the designed sensor

The CV technique was employed to analyze the electrochemical characteristics of BIP/GCE, NBIP/GCE, and BIP/MGCE in solutions comprising 5 mM [Fe (CN)6]3−/4−and 0.1 M KCl (Fig. 2). In this context, the unmodified GCE is represented (curve 2a). After the electropolymerization process, a notable decrease in peak current was observed (curve 2b), indicating successful polymerization. When the polymerized electrode was treated with a leaching solution (0.01 M SDS in triple distilled water) for 15 min, enhancement in the peaks for [Fe (CN)6]3−/4− was noted, as cavities formed on the electrode surface due to the removal of the template (curve 2c). After exposing the BIP/GCE to a solution of E. coli at a concentration of 104 CFU mL− 1, E. coli molecules were rebounded to the copolymer matrix, leading to a subsequent reduction in peak current (curve 2d). The electrochemical activity of [Fe (CN)6]3−/4− after template removal on the NBIP/GCE was also studied. As illustrated in (curve 2e), the NBIP/GCE profiles exhibited no significant changes. To demonstrate that the leached BIP/MGCE effectively captures E. coli, a comparison was made between the imprinted and un-imprinted groups while maintaining consistent experimental conditions. The result showed no significant difference in the electrochemical behavior of the non-imprinted group, which was attributed to the lack of template bacteria and the absence of imprinting sites in the non-imprinted sensor35. Finally, the electrical conductivity of MGO–IL–Pd nanocomposite was assessed. As illustrated in (curve 2f), the redox current recorded for BIP/MGCE exhibited a notable increase compared to the bare electrode, suggesting that MGO–IL–Pd nanocomposite enhances electron transfer on the electrode surface, thereby strengthening the electrochemical response.

Cyclic voltammograms of (a) bare GCE, (b) dopamine electropolymerization on GCE, (c) after E. coli removal, (d) BIP/GCE after E. coli rebinding, (e) NBIP/GCE after elution, and (f) BIP/MGCE after removing 10⁴ CFU/mL E. coli. All measurements were performed in 0.1 M KCl containing 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ at a scan rate of 0.1 V/s.

The present of trimethoxysilylpropyl group in the IL structure may be enable the covalent anchoring to the magnetic graphene oxide surface, ensuring film stability during electropolymerization and washing. Besides, the chloride counter ion provides high ionic conductivity and compatibility in aqueous media, facilitating dopamine oxidation and polymer growth.

However, when MGO–IL–Pd was applied in conjunction with E. coli bacteria on the electrode surface, a reduction in the current of BIP/MGCE was observed. This reduction may be due to the interactions between the negatively charged E. coli bacteria and the functionalized surface.

Figure 3 presents the EIS pattern bare GCE, dopamine-electropolymerized GCE, after E. coli removal, BIP/GCE after E. coli rebinding, and BIP/MGCE post E. coli removal. All measurements were conducted in 0.1 M KCl containing 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− solution. For the bare GCE (curve a), the impedance spectrum shows the initial baseline response. After electropolymerization, a pronounced high-frequency semicircle appears (curve b), suggesting the formation of a non-conductive layer on the electrode surface (BIP/GCE). When E. coli was removed from the electrode using a washing solution, the semicircle size decreased (curve c), indicating easier electron transfer due to the creation of pores roughly matching the bacterial dimensions. Upon rebinding the bacterial template in the BIP, the semicircle size increased again (curve d), confirming successful formation of the BIP film. The electrical conductivity of the MGO-IL-Pd nanocomposite was also assessed. As shown in curve 2e, the re-removal of E. coli with the washing solution resulted in a sharp decrease in the semicircle size, confirming the significant increase in the redox current for the BIP/MGCE compared to the bare GCE. These findings indicate that the MGO-IL-Pd nanocomposite promotes electron transport at the electrode interface, thereby improving the electrochemical signal. This behavior aligns with the CV results and supports the conclusion that cavity structures are generated during electropolymerization in the presence of the bacterial template.

Nyquist plots of (a) bare GCE, (b) dopamine-electropolymerized GCE, (c) after template (E. coli) removal, (d) BIP/GCE after E. coli rebinding, and (e) BIP/MGCE post-template elution. All measurements were performed in 0.1 M KCl containing 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆] 3−/4−, with a frequency range of 0.05 Hz to 80 kHz and an amplitude of 10 mV.

Optimization of experimental conditions

Accumulation time, polymerization cycles, and leaching time

Several parameters and conditions, including accumulation time, polymerization cycles, and leaching time, were optimized to improve the sensor’s analytical capabilities. Various accumulation times (from 5 to 30 min) were evaluated for E. coli saturation. As shown in Fig. 4a, the ΔI was computed using the formula ΔI = I − I0, where I represents the current assayed in the presence of E. coli, and I0 represents the current in the absence of E. coli in the sensor, progressively increased with longer accumulation times, peaking at 15 min, indicating that the E. coli detection process had reached saturation; thus, 15 min was chosen as the optimum accumulation time. The thickness of the printed polymer layer was analyzed to assess how varying polymerization cycles impacted sensor performance.

As depicted in Fig. 4b, the ΔI value significantly increased as the number of polymerization cycles increased from 5 to 15 cycles, stabilizing at 15 cycles. Consequently, 10 cycles were chosen for subsequent experiments. A lower number of scanning cycles results in a thinner polymer layer that is unstable and prone to damage, while excessive cycles lead to an overly thick polymer layer that hinders the removal of template molecules, resulting in insufficient site pores. The optimal leaching time is illustrated in Fig. 4c. The ΔI value increased with longer leaching times, indicating that more site pores were formed on the electrode surface as template molecules were removed. The ΔI value reached its maximum at a leaching time of 25 min. However, with further prolongation of the leaching time, the ΔI value began to decrease, likely due to the extended leaching time adversely affecting the polymer structure and reducing the detection capability of the bacterial site pores. Therefore, 15 min was chosen as the optimal leaching time.

Scan rate effect

To investigate the effect of scan rate (Ʋ) on the response of the BIP/MGCE-based sensor, several voltammograms were recorded for a typical standard solution of E. coli (10⁴ CFU mL⁻¹) at scan rates ranging from 10 to 100 mV s⁻¹. As depicted in Fig. 5, the voltammograms illustrate the change in current response across the applied potential range, providing insights into the electrochemical behavior of the BIP/MGCE-based sensor in the presence of E. coli. The results indicated a linear relationship between both the forward and backward peak currents and the Ʋ within the tested range (10 to 100 mV s⁻¹). The strong linear correlation, evidenced by a regression coefficient (R²>0.99), indicates that the electrochemical process is predominantly adsorption-controlled40. In adsorption-controlled electrochemical processes, the peak current typically increases linearly with the scan rate, which is consistent with the observed results.

Selectivity of the designed sensor

The BIP/MGCE sensor was investigated for the selective detection of E. coli in the presence of other microorganisms such as S. epidermidis, S. aureus, and C. albicans. As shown in Fig. 6a, the recorded current changes (ΔI) for the PDA-based BIP/MGCE sensor were significantly higher for E. coli than the other tested microorganisms. These current variations indicate that the BIP/MGCE sensor selectively detects E. coli, confirming the high selectivity of the electrochemical sensor. The minimal responses to S. epidermidis, S. aureus, and C. albicans further demonstrate the sensor’s ability to distinguish E. coli from other microorganisms, making it suitable for use in complex biological samples. This high selectivity is due to the use of the BIP, which is highly selective and designed to detect E. coli, making the sensor a practical and reliable tool for detecting this bacterium.

In the other experiments, the selectivity of the designed sensor toward E. coli compared to other microorganisms was evaluated by analyzing the effect of structurally related compounds and biologically relevant molecules, such as S. epidermidis, S. aureus, and C. albicans, which could potentially interfere with the detection of E. coli. Using the proposed technique, the sensor’s response to E. coli was examined in the presence of these interfering species at varying concentrations (103 to 106 CFU/mL) under optimum conditions, as shown in Fig. 6b.

The results in Table 1 indicate that the sensor maintains high selectivity for E. coli despite the presence of these interferences. The relative error percentage (RE%) and tolerance ratio (TR) were calculated to quantify the sensor’s performance. For S. aureus, the RE% ranged from 1.16% to 11.92%, while for S. epidermidis, it ranged from 2.07% to 13.88%, and for C. albicans, it ranged from 1.85% to 12.73%. These low RE% values, along with the TR values, confirm that the sensor’s detection of E. coli remains largely unaffected by the presence of these interfering species up to 1000-fold. This demonstrates the sensor’s ability for selective detection of E. coli even in complex biological environments where structurally similar microorganisms may be present.

Figures of merit of the designed sensor

The applicability of the leached BIP/MGCE electrochemical biosensor for E. coli sensing was evaluated using various concentrations of E. coli solutions under optimum conditions. A series of E. coli concentrations (5.0 to 1.0 × 107 CFU/mL) were independently incubated with the prepared leached BIP/MGCE and analyzed using the SWV technique. As shown in Fig. 7a, the SWV response decreased as the concentration of E. coli increased, which was attributed to the selective recognition of E. coli by the BIP, hindering electron transfer to the electrode surface. The changes in current exhibited a strong linear relationship with the E. coli concentration across the range of 5.0 to 1.0 × 107 CFU/mL. The calibration curve relating the SWV response to the logarithm of concentration (Fig. 7b) yielded the linear regression equation I = 122.58–24.96 logC (R2 = 0.992). The limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) were calculated using 3-fold and 10-fold of the standard deviation of the blank solution divided by the slope of the calibration curve, respectively, resulting in very low LOD (1.50 CFU/mL) and LOQ (4.95 CFU/mL) values for the present sensor.

The intra-day and inter-day repeatability of the biosensor was evaluated using the CV technique in a solution containing 0.1 mol/L KCl and 5.0 mmol/L of the redox probe [Fe(CN)6]3−/4−. For intra-day and inter-day tests, the response of a typical sensor to a standard solution of E. coli (104 CFU mL−1) was recorded in order during 8 h and six days, and the RSD% of the recorded currents was calculated. The low RSD% values (1.50% and 2.69%) confirm the excellent stability and repeatability of the fabricated biosensor, as illustrated in Figure S3.

Additionally, to assess the reproducibility of the biosensor, five similar sensors were fabricated and tested in a solution containing 104 CFU mL− 1 E. coli. The RSD of the recorded currents across the five electrodes was calculated, demonstrating high reproducibility with a very low RSD of 2.83%, as shown in Fig. S3. The results demonstrate the reliability and consistency of the biosensor in precisely detecting E. coli.

The reusability of the developed BIP/MGCE electrochemical biosensor for E. coli detection was evaluated through multiple binding/elution cycles using an aqueous solution of SDS as leaching solution (0.01 M SDS in triple-distilled water) for 15 min. SWV analysis demonstrated excellent sensor reusability at two concentration levels (102 and 106 CFU mL−1), with RSD of 2.20% and 1.03%, respectively, across five replicate measurements.

Comparison study

Table 2 provides a comparison of this sensor’s performance with other methods for E. coli detection47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54. The BIP/MGCE electrochemical biosensor demonstrates superior performance for E. coli detection, offering an exceptionally wide linear range (5.0 to 1.0 × 107 CFU/mL) and an ultra-low LOD (1.5 CFU/mL), outperforming methods like graphitized mesoporous carbon-modified electrodes (LOD: 50.4 CFU/mL)47 and C60-based immunosensors (LOD: 15.0 CFU/mL)50. The use of a BIP and MGO-IL-Pd nanocomposite enhances selectivity and applicability, making it a highly sensitive, cost-effective, and practical tool for E. coli detection in clinical and environmental applications.

Real sample analysis

The biosensor’s performance was evaluated for detecting E. coli in real samples, including human urine and serum, under optimized conditions using the SWV technique. Measurements were conducted in triplicate (n = 3), and the results demonstrated high accuracy and precision. According to the results presented in Table 3, in urine samples, recovery values ranged from 98% to 103%, with relative standard deviation (RSD) values between 0.52% and 1.06%. Similarly, in serum samples, recovery values ranged from 97% to 102%, with RSD values lower than 2%. These findings highlight the biosensor’s reliability and precision in a complex biological matrix.

Conclusions

In this research, a novel electrochemical biosensor utilizing polydopamine (PDA) and modification with a newly developed nanocomposite (i.e., MGO–IL–Pd) was designed and successfully developed for the rapid and direct determination of E. coli. The biosensor demonstrates remarkable selectivity for the recognition of E. coli in the presence of other microorganisms. The incorporation of MGO–IL–Pd as a chemical modifier significantly enhanced the electrochemical response of the sensor. Additionally, PDA’s excellent biological compatibility and strong adhesion to the electrode contributed to achieving highly sensitive electrochemical detection of E. coli. Compared to previously reported BIP-based electrochemical sensors, this biosensor offers distinct advantages, including an extremely low detection limit of 1.5 CFU mL⁻¹ and a remarkably short detection time. Meanwhile, the designed biosensor was applied for determination of E. coli content in some biological real samples, successfully with high precision and recovery percentages. Furthermore, this method can be developed as a simple detection strategy for various bacterial species.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Gado, D. A., Ehizibolo, D. O., Meseko, C. A., Anderson, N. E. & Lurz, P. W. Review of emerging and re-emerging zoonotic pathogens of dogs in nigeria: missing link in one health approach. JZD 3, 134–161. https://doi.org/10.3390/zoonoticdis3020012 (2023).

Khan, I. et al. Foodborne pathogens: Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria monocytogenes an unsolved problem of the food industry. PJN 15, 505–514. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjn.2016.505.514 (2016).

He, Y. et al. Research progress of aptasensor technology in the detection of foodborne pathogens. Food Control. 153, 109891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2023.109891 (2023).

Oluwarinde, B. O. et al. Safety properties of Escherichia coli O157:H7 specific bacteriophages: recent advances for food safety. Foods 12, 3989. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12213989 (2023).

Martinson, J. N. & Walk, S. T. Escherichia coli residency in the gut of healthy human adults. EcoSal Plus. 9, 10–1128. https://doi.org/10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0003-2020 (2020).

Ho, J. Y. et al. Multidrug-resistant bacteria and microbial communities in a river estuary with fragmented suburban waste management. J. Hazard. Mater. 405, 124687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124687 (2021).

Rodriguez, R. S. et al. Sensing food contaminants: advances in analytical methods and techniques. J. Anal. Chem. 93, 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.0c04357 (2020).

Podolsky, I. A., Seppälä, S., Lankiewicz, T. S., Brown, J. L. & Swift, C. L. O’Malley, M. A. Harnessing nature’s anaerobes for biotechnology and bioprocessing. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 10, 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-060718-030340 (2019).

Xia, Q. et al. Innovative processing techniques for altering the physicochemical properties of wholegrain brown rice (Oryza sativa L.) – Opportunities for enhancing food quality and health attributes. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 59, 3349–3370. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2018.1488277 (2019).

Franco-Duarte, R. et al. Advances in chemical and biological methods to identify microorganisms – from past to present. Microorganisms 7 https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7050130 (2019).

Sheydaei, O., Khajehsharifi, H. & Rajabi, H. R. Rapid and selective diagnose of sarcosine in urine samples as prostate cancer biomarker by mesoporous imprinted polymeric nanobeads modified electrode. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 309, 127559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2019.127559 (2020).

Aryan, Z., Rajabi, H. R., Khajehsharifi, H. & Sheydaei, O. Highly selective determination of Alanine in urine sample using a modified electrochemical sensor based on silica nanoparticles-imprinted polymer. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 19, 4139–4148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13738-022-02589-6 (2022).

Zarezadeh, A., Rajabi, H. R., Sheydaei, O. & Khajehsharifi, H. Application of a nano-structured molecularly imprinted polymer as an efficient modifier for the design of Captopril drug selective sensor: mechanism study and quantitative determination. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 94, 879–885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2018.10.042 (2019).

Rajabi, H. R., Roushani, M. & Shamsipur, M. Development of a highly selective voltammetric sensor for nanomolar detection of mercury ions using glassy carbon electrode modified with a novel ion-imprinted polymeric nanobeads and multi-wall carbon nanotubes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 693, 16–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2013.01.003 (2013).

McKeever, C., Callan, S., Warren, S. & Dempsey, E. Magnetic nanoparticle modified electrodes for voltammetric determination of propellant stabiliser diphenylamine. Talanta 238, 123039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2021.123039 (2022).

Sheydaei, O., Khajehsharifi, H. & Rajabi, H. R. The design of a copper nanoclusters-modified electrode for electrochemical determination of glutathione in some real samples. Anal. Bioanal Chem. Res. 12, 407–419. https://doi.org/10.22036/abcr.2025.479289.2181 (2025).

Nazari, Z., Hadi Nematollahi, M., Zareh, F., Pouramiri, B. & Mehrabani, M. An electrochemical sensor based on carbon quantum dots and ionic liquids for selective detection of dopamine. ChemistrySelect 8, e202203630. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202203630

Zahed, F. M., Hatamluyi, B. & Bojdi, M. K. A sensitive electrochemical sensor based on graphene quantum dots/hierarchical flower-like gold nanostructures for determination of cytostatic drug Flutamide. Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 300, 117109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mseb.2023.117109 (2024).

Yuan, R. et al. Electrochemistry sensing of ascorbic acid based on conductive metal-organic framework (Cu3 (benzenehexathiol)) nanosheets modified electrode. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1353, 343980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2025.343980 (2025).

da Silva, D. M. Carneiro Da Cunha Areias, M. Voltammetric detection of Captopril in a commercial drug using a gold-copper metal‐organic framework nanocomposite modified electrode. Electroanalysis 33, 1255–1263. https://doi.org/10.1002/elan.202060271 (2021).

Gañán, J., Martínez-García, G., Morante-Zarcero, S., Pérez-Quintanilla, D. & Sierra, I. Nanomaterials-modified electrochemical sensors for sensitive determination of alkaloids: recent trends in the application to biological, pharmaceutical and agri-food samples. Microchem J. 184, 108136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2022.108136 (2023).

Singh, D., Verma, N., Bhari, R. & Kumar, K. Fabrication of electrochemical sensor based on molecularly imprinted polymers for monitoring Chlorpyrifos in real samples. Bull. Mater. Sci. 47, 84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12034-024-03142-2 (2024).

Zabardasti, A., Afrouzi, H. & Talemi, R. P. A simple and sensitive methodology for voltammetric determination of valproic acid in human blood plasma samples using 3-aminopropyletriethoxy silane coated magnetic nanoparticles modified pencil graphite electrode. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 76, 425–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2017.02.140 (2017).

Bagheri, H., Shirzadmehr, A. & Rezaei, M. Designing and fabrication of new molecularly imprinted polymer-based potentiometric nano-graphene/ionic liquid/carbon paste electrode for the determination of Losartan. J. Mol. Liq. 212, 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2015.08.055 (2015).

Li, Y., Zhang, M., Shi, X. & Wu, Z. Bacteria imprinted electrochemical sensor based on bimetallic silver-gold sea urchin-like Hollow nanoparticles for ultrasensitive detection of Listeria monocytogenes. Microchem J. 205, 111206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2024.111206 (2024).

Setznagl, S. & Cesarino, I. Copper nanoparticles and reduced graphene oxide modified a glassy carbon electrode for the determination of glyphosate in water samples. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 102, 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/03067319.2020.1720667 (2022).

Hui, Y. et al. Rapid and label-free electrochemical aptasensor based on a palladium nanoparticles/titanium carbide/polyethyleneimine functionalized nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes composite for amplified detection of streptomycin. Food Chem. 432, 137271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.137271 (2024).

Abbas, A. & Amin, H. M. A. Silver nanoparticles modified electrodes for electroanalysis: an updated review and a perspective. Microchem J. 175, 107166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2021.107166 (2022).

Absalan, G., Akhond, M., Soleimani, M. & Ershadifar, H. Efficient electrocatalytic oxidation and determination of Isoniazid on carbon ionic liquid electrode modified with electrodeposited palladium nanoparticles. J. Electroanal. Chem. 761, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2015.11.041 (2016).

Aryan, Z., Khajehsharifi, H. & Shahrokhian, S. A sensitive platform based on molecularly imprinted polymer modified with AuNPs-ultrathin/graphitic-C3N4 for voltammetric determination of Hippuric acid. Diam. Relat. Mater. 154, 112083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diamond.2025.112083 (2025).

Roushani, M. & Zalpour, N. Selective detection of Asulam with in-situ dopamine electropolymerization based electrochemical MIP sensor. React. Funct. Polym. 169, 105069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2021.105069 (2021).

Verma, D. et al. Electrochemical sensor based on polydopamine-molecularly imprinted polymer for detection of 4-ethylphenyl sulfate a novel gut metabolite: fabrication, characterization, and performance evaluation in human urine. Microchem J. 193, 108964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2023.108964 (2023).

Menichetti, A., Mavridi-Printezi, A., Mordini, D. & Montalti, M. Polydopamine-based nanoprobes application in optical biosensing. Biosensors 13, 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios13110956 (2023).

Chen, S., Chen, X., Zhang, L., Gao, J. & Ma, Q. Electrochemiluminescence detection of Escherichia coli O157: H7 based on a novel polydopamine surface imprinted polymer biosensor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 9, 5430–5436. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b12455 (2017).

Roushani, M., Sarabaegi, M. & Rostamzad, A. Novel electrochemical sensor based on polydopamine molecularly imprinted polymer for sensitive and selective detection of acinetobacter baumannii. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 17, 2407–2413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13738-020-01936-9 (2020).

Nemati, R., Elhamifar, D., Zarnegaryan, A. & Shaker, M. Magnetic silica nanocomposite supported W6O19/amine: A powerful catalyst for the synthesis of biologically active spirooxindole-pyrans. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 145, 109934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2022.109934 (2022).

Lin, J., Daboss, S., Blaimer, D. & Kranz, C. Micro-structured polydopamine films via pulsed electrochemical deposition. Nanomaterials 9, 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9020242 (2019).

Almeida, L. C., Correia, R. D., Correia, J. P. & Viana, A. S. Combined electrochemical, ellipsometric and microgravimetric study of ion permeable polydopamine films. J. Electrochem. Soc. 169, 046503. https://doi.10.1149/-7111/ac60f0 (2022) (1945).

Sohouli, E. et al. A new electrochemical aptasensor based on gold/nitrogen-doped carbon nano-onions for the detection of Staphylococcus aureus. Electrochim. Acta. 403, 139633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2021.139633 (2022).

Roushani, M., Jalilian, Z. & Nezhadali, A. A novel electrochemical sensor based on electrode modified with gold nanoparticles and molecularly imprinted polymer for rapid determination of Trazosin. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 172, 594–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.09.015 (2018).

Antarnusa, G., Jayanti, P. D., Denny, Y. R. & Suherman, A. Utilization of co-precipitation method on synthesis of Fe3O4/PEG with different concentrations of PEG for biosensor applications. Acta Mater. 25, 101525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtla.2022.101525 (2022).

Suharyadi, E., Alfansuri, T., Handriani, L. S., Wibowo, N. A. & Sabarman, H. Detection of Fe3O4/PEG nanoparticles using one and two spin-valve GMR sensing elements in Wheatstone Bridge circuit. J. Mater. Sci. : Mater. Electron. 32, 23958–23967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-021-06859-6 (2021).

He, H. et al. Natural magnetite: an efficient catalyst for the degradation of organic contaminant. J. Sci. Rep. 5, 10139. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10139 (2015).

Vahidian, M., Elhamifar, D. & Shaker, M. Core–shell structured magnetic mesoporous silica-titania: a novel, powerful and recoverable nanocatalyst. Polyhedron 178, 114326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poly.2019.114326 (2020).

Shaker, M. & Elhamifar, D. Magnetic Ti-containing phenylene-based mesoporous organosilica: A powerful nanocatalyst with high recoverability. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem Eng. 608, 125603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125603 (2021).

Dadvar, F. & Elhamifar, D. A. Pd-containing ionic liquid modified magnetic graphene oxide nanocomposite (Fe3O4/GO–IL–Pd) as a powerful catalyst for the reduction of nitrobenzenes. Nanoscale Adv. 6, 5398–5408. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4NA00475B (2024).

Rishi, M. et al. Rapid, sensitive and specific electrochemical detection of E. coli using graphitized mesoporous carbon modified electrodes. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 338, 113483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2022.113483 (2022).

Viswanathan, S., Rani, C. & Ho, J. A. A. Electrochemical immunosensor for multiplexed detection of food-borne pathogens using nanocrystal bioconjugates and MWCNT screen-printed electrode. Talanta 94, 315–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2012.03.049 (2012).

Li, Y. et al. Amperometric immunosensor for the detection of Escherichia coli O157: H7 in food specimens. Anal. Biochem. 421, 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2011.10.049 (2012).

Li, Y. et al. An electrochemical immunosensor for sensitive detection of Escherichia coli O157: H7 using C60 based biocompatible platform and enzyme functionalized Pt nanochains tracing Tag. Biosens. Bioelectron. 49, 485–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2013.06.008 (2013).

Idil, N., Hedström, M., Denizli, A. & Mattiasson, B. Whole cell based microcontact imprinted capacitive biosensor for the detection of Escherichia coli. Biosens. Bioelectron. 87, 807–815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2016.08.096 (2017).

Wang, R. F. & Wang, R. Modification of polyacrylonitrile-derived carbon nanofibers and bacteriophages on screen-printed electrodes: A portable electrochemical biosensor for rapid detection of Escherichia coli. Bioelectrochemistry 148, 108229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioelechem.2022.108229 (2022).

Zhang, J., Wang, J., Zhang, X. & He, F. Rapid detection of Escherichia coli based on 16S rDNA nanogap network electrochemical biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 118, 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2018.07.041 (2018).

Arreguin-Campos, R. et al. Biomimetic sensing of Escherichia coli at the solid-liquid interface: from surface-imprinted polymer synthesis toward real sample sensing in food safety. Microchem J. 169, 106554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2021.106554 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Central Laboratory of Yasouj University for providing the facilities and technical support essential for this research.

Funding

There is no any funding source for this publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first draft of the manuscript was written and the data were interpreted by Ali Gorjizadeh Kohvade. Prof. Hamid Reza Rajabi and Prof. Mahmoud Roushani were responsible for revising the manuscript and for checking all technical and grammatical aspects. Prof. Dawood Elhamifar and Ms. Farkhondeh Dadvar assisted with the synthesis and characterization of the nanomaterials used in this study. All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gorjizadeh Kohvade, A., Rajabi, H.R., Roushani, M. et al. An ultrasensitive and selective electrochemical biosensor for Escherichia coli based on bacteria-imprinted polydopamine and a magnetic nanocomposite modifier. Sci Rep 15, 45229 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28920-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28920-8