Abstract

The installation of steel casings in riprap-covered macro-tidal estuarine mudflats is governed by a complex interplay of soil, tidal and pore-water pressures, frequently causing the casing to refuse to penetrate or to deviate from its design alignment. Perforating steel casings can effectively mitigate the adverse pressure build-up described above, yet it simultaneously compromises casing strength and stability. Taking the steel casings of a typical Chinese seawall project as the reference, this study employs finite-element modelling to simulate the entire installation process and quantify how varying perforation patterns alter the internal forces and stress-concentration factors at the openings when the casing is driven through riprap-armoured macro-tidal estuarine mudflats. The results indicate that perforations lower the casing’s global shear and bending capacity, which in turn loosens the soil plug at the tip and markedly reduces penetration resistance. This reduction in resistance, however, amplifies both the horizontal and vertical displacements generated when the casing strikes riprap blocks. Under dynamic impact and riprap-reaction forces, the stress-concentration curves for openings situated closer to the load becomes flatter and the corresponding factor diminishes, signifying a more uniform stress distribution over the cross-section. Moving the perforation away from the casing head progressively raises the stress-concentration factor and intensifies the local peak. Star-shaped perforations yield markedly smoother stress-concentration curves than either single- or twin-directional patterns. These findings furnish a quantitative basis for selecting perforation geometry and placement when driving steel casings through riprap armour in macro-tidal estuarine mudflats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To mitigate scour at the dike toe induced by tidal currents and swell on the estuarine bank slope, extensive quantities of quarried stone have been placed on the nearshore mudflats along China’s coast to create a riprap armor layer. After prolonged cycles of scour, deposition and estuarine hydrodynamics, much of the riprap has settled into the mud, forming a near-continuous stone blanket beneath the present mudflat1,2. The soil at the casing end will be compacted (soil squeezing effect) during the construction of steel casings, reducing the gaps between soil particles and preventing the smooth discharge of pore water, resulting in an increase in pore water pressure in the soil inside the casings3. As the hydrostatic pressure within the casing rises, so does the buoyant force acting on the steel string. Should this buoyancy surpass the combined influence of the casing’s own weight and any applied surcharge, the string may either refuse to sink any further or even rise. In extreme cases, the outcome can be a costly engineering failure. Perforating the steel casing accelerates the dissipation of excess pore-water pressure, mitigates the adverse effects of soil displacement during installation, and reduces the hydrodynamic loads imposed by tides and surges, thereby minimizing their influence on casing lateral movement4. Drilling holes inevitably reduces the effective cross-section and disrupts the material continuity of the steel casing. Under axial load or impact from riprap, stress near the perforations rises sharply, producing pronounced stress concentrations. This non-uniform stress state compromises both the bearing capacity and the overall stability of the casing.

In recent years, researchers have intensively investigated the vibratory installation of steel casings (or piles) and the buckling and stress-concentration behaviour of perforated thin-shell structures, amassing a substantial body of valuable experience. On the experimental front, Staubach and Machacek5 performed model tests on vibratory pile driving in saturated sand and found that, under high-frequency excitation, the relative acceleration between the solid skeleton and the pore water is significant and cannot be neglected. Massarsch et al.6 investigated, through full-scale case studies, how vibration frequency influences the drivability and subsequent bearing capacity of sheet piles. Their model tests revealed that high-frequency driving generates an “arch-effect” zone along the pile shaft, reducing the effective normal stress and markedly diminishing shaft resistance. Zirka et al.7 examined stress concentrations around circular cut-outs in medium-thickness cylindrical shells and observed peak stresses at both the hole boundary and the inner shell surface; remarkably, the stress-concentration factor was found to be independent of hole diameter. Kamalarajah et al.8 later subjected cylindrical shells containing circular apertures of various sizes to axial compression and reported the development of membrane stresses along the hole perimeter, accompanied by perturbations that propagated well beyond the immediate edge of the opening. Ghazijahani et al.9 investigated the axial-compression stability of cylindrical shells containing portal-type cut-outs, quantified how different opening geometries alter the structural response, and demonstrated that locally reinforcing the perforated region can fully offset the capacity lost to the notch. Brunesi et al.10 combined testing with high-resolution simulations to quantify how the shape, size, position and number of cut-outs govern the buckling and post-buckling behaviour of axially compressed cylindrical steel shells. They found that the critical buckling mode is controlled primarily by the angular width of the opening and that the shell’s resistance drops sharply as this angle increases.

Zhang et al.11 performed external-hydrostatic-pressure tests on composite cylindrical shells, both intact and perforated, and tracked their strain histories. The recorded responses reveal three distinct phases: an initial linear-compression regime, followed by abrupt buckling, and a subsequent post-buckling stage characterised by pronounced deformation. On the numerical front, Bakroon et al.12 simulated the vibratory driving of steel casings and showed that any buckling event immediately reduces the achievable penetration rate. Sadamoto et al.13 developed a characteristic-buckling model for curved shells and demonstrated, through load and modal analyses of shallow, cylindrical and perforated cylindrical shells, that it delivers high-fidelity stability predictions for arbitrarily curved geometries. Storozhuk et al.14 used the finite-element method to examine how the geometric parameters of perforations in axially tensioned cylindrical shells affect the distributions of stress, strain and displacement around the opening. Their results show that, for the particular aperture geometry considered, peak deflection, strain and stress at the hole are lower than those induced by any of the alternative shapes studied. Gokyer and Sonmez15 determined the optimum stiffener dimensions for cylindrical shells containing square cut-outs with the goal of maximizing buckling capacity, and formulated a finite-element model to predict the critical load of the reinforced shell.

Collectively, these studies have created a robust framework for understanding perforated casing walls and thin-shell behaviour, yet almost no data exist on how slotted steel casings perform when they are vibrated into riprap-rich silts beneath macro-tidal estuaries. In particular, the influence of hole-induced stress concentrations on casing safety and stability during installation, and the accompanying loss of bearing capacity when the shell strikes embedded stones, remain unquantified. Consequently, this study selects the steel casings used in typical seawall projects in Zhejiang Province, China, as the research object. By means of numerical simulation, and focusing on the construction design of steel casings in the riprap environment near the macro-tidal estuary mudflat, it investigates how the stress distribution in a perforated casing evolves and how the casing’s load-carrying capacity varies when it collides with riprap. By systematically examining the internal forces generated in the casing under different perforation patterns and the resulting stress-concentration distributions around the openings, an optimum hole-layout scheme is identified for steel casings driven through riprap-laden estuarine mudflats. The outcome furnishes a rational design basis for the safe installation of perforated casings in macro-tidal, stone-armoured shoreline environments.

Overview of projects

Located on the south bank of Jianshan River Bend of the Qiantang River and on the left bank of the Cao’e River estuary, the Keqiao seawall in Shaoxing City runs 5.85 km from the Dongjiang Sluice at the Xiaoshao boundary to the approach embankment on the left bank of the Cao’e estuary, forming a critical reach of the Qiantang River’s southern flood-defence line. Originally designed to withstand a 100-year flood, the seawall has seen its foreshore severely eroded and its stone-toe protection undermined; the protective apron is now cracked and the wave-wall facing partly detached. An upgrade programme is therefore under way to raise the defence standard to a 300-year return period, and fourteen spur dikes are being installed to check erosion and encourage accretion. The new spur-dike scheme uses a steel trestle working platform: bored piles are cast through steel casings installed from the deck. A crawler crane fitted with a vibratory hammer drives the casing to depth; after placing the reinforcement cage and concreting under water, the same hammer extracts the casing16. At the Aojiang River mouth, the Longgang Seawall project faces the same casing challenge while building a viewing platform offshore. A single 11 m-long, 1.2 m-diameter, 20 mm-thick steel casing is driven, the cage is lowered, underwater concrete is placed, and the casing is then extracted (Shown in Fig. 1). Project location and the proposed casing perforation pattern are given in Fig. 2.

Construction process of concrete cast-in-place pile. (a) Pile positioning and installation of steel casing; (b) Impact drilling, mud circulation wall protection and hole cleaning; (c) Placing steel cages, secondary hole cleaning and measuring slag formation; (d) Underwater concrete pouring; (e) Pulling out the concrete conduit and steel casing.

Geographical location and actual situation diagram of the project. (a) China map; (b) Map of Zhejiang Province; (c) Geographical location diagram of Keqiao Seawall Project; (d) Geographical location diagram of Longgang Seawall Project; (e) Steel casing sinking under the action of the vibration hammer; (e) Construction of steel casing under the action of vibration hammer; (f) Steel casings piled up on the construction site; (g) Rectangular openings in the steel casing body; (h) Partial enlarged view of rectangular opening in the steel casing. (a and b are sourced from http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn/; c and d was obtained from 91 Map Free Version, Version (19.4.0), available at https://mydown.yesky.com/pcsoft/37063219.html).

Materials and methods

Numerical model

Driving the steel casing generates large plastic strains in the surrounding soil and produces a pronounced soil-displacement (squeezing) effect17,18,19,20. Given the short construction period, the foundation soils are generally assumed to remain saturated and undrained21. Consequently, the saturated-undrained response of the soil is captured with the Mohr–Coulomb model, whose yield function is as follows22,23,24,25,26:

where q is Mises equivalent stress, kPa; p is static water pressure, kPa; \(\varphi\) is the internal friction angle, °; \(c\) is the cohesive force, kPa; \({R}_{mc}(\Theta ,\varphi )\) is the correction factor for generalized shear stress used to control the shape of the yield surface in the \(\uppi\) plane, expressed as follows:

where \(\Theta\) is the polar deviation angle, \(\text{cos}\left(3\Theta \right)=\frac{{r}^{3}}{{q}^{3}}\), of which,\(r\) is the third deviatoric stress invariant, kPa.

To eliminate the numerical convergence difficulties caused by the abrupt change in plastic-flow direction at the Mohr–Coulomb yield-surface apex, an elliptical plastic potential function is adopted:

where \(\psi\) is the shear dilation angle, °; \(c{|}_{0}\) is the initial cohesive force, kPa; \(\varepsilon\) is the eccentricity on the meridian plane, usually taken as 0.1; \({R}_{mw}\) is the improved correction coefficient, calculated using the following formula:

where e is the eccentricity on the \(\uppi\) plane, calculated by the following equation:

Selection of element types

The fidelity with which numerical models can reproduce casing buckling depends as much on the choice of element type as on the steel’s constitutive parameters. Prior to building the full model, a benchmark case is set up to quantify how element formulation affects the predicted critical buckling stress of a Q235 steel casing under uniform axial compression. The same tube is discretised with both reduced-integration shell elements (S4R) and 8-node solid elements; the material data are given in Table 1.

The mesh consists of 0.01 m × 0.01 m quadrilateral elements; the base is fully fixed (translations and rotations restrained), while the top is pinned against horizontal translation and rotation. A uniform axial compressive load of 100 kN is applied vertically to the upper rim. The benchmark model is shown in Fig. 3.

The critical stress calculation formula for buckling failure of the steel casing is as follows27:

where \(E\) is the elastic modulus, GPa; \(t\) is the wall thickness, m; \(R\) is the radius of the casing, m; \(v\) is Poisson’s ratio.

From Eq. (6), the calculation formula for the buckling bearing capacity line load of cylindrical thin-walled structures is

The buckling load coefficient, defined as the proportional scaling factor of the applied load, is computed during the nonlinear buckling analysis step in ABAQUS. Consequently, the buckling load of thin-walled cylindrical structures can be determined from the following relationship:

where \(\lambda\) is the buckling load coefficient; \(P\) is the external load applied to the thin-walled cylindrical structure, kN.

Using the buckling load coefficient as the benchmark, the corresponding critical buckling stress is derived from Eqs. (6)–(8) and compared with the theoretical prediction. Table 2 lists the buckling load coefficients and critical buckling stresses obtained for the steel casing under both unit systems, while the associated buckling modes are displayed in Fig. 4.

Table 2 shows that the shell-element predictions are in markedly better agreement with the theoretical values: the critical buckling stress obtained with shell elements deviates by only 4% from theory, whereas the solid-element result exhibits a substantially larger error. Moreover, Fig. 4 reveals that shell elements capture the local buckling deformation of the casing far more faithfully. Consequently, shell elements are adopted for all subsequent simulations of the mechanical response and deformation behaviour of steel casings.

Excitation force model

The excitation force comprises two components: a static load, equal to the combined weight of the vibrating hammer, hook and ancillary parts, and a dynamic load produced by the exciter in the form of a sinusoidal vibration. The resultant force is calculated as follows28,29,30:

where \({F}_{d}\) is excitation force, kN; \({F}_{0}\) is static load force, kN; \({F}_{v}\) is the dynamic load force, kN; \({F}_{c}\) is the amplitude of dynamic load, kN; \({t}_{s}\) is time, s; \(\omega\) is pi, \(\omega =2\uppi f\), of which, f is the vibration frequency, Hz; \({\varphi }_{0}\) is the initial phase angle, °.

Construction of numerical models

According to Sun et al.31, when the soil mass extends to 10 times the diameter D of a solid pile, the influence of pile construction on the soil boundary is limited. The steel casing studied in this paper is a hollow thin-walled structure with a relatively small actual cross-sectional size; thus, during driving it disturbs the surrounding soil far less than a solid pile does. To improve computational efficiency, the geometric model of the soil around the steel casing is set as a casing with a diameter of 12 m (10 D) and a height of 13.2 m (11 D). An oversized mesh is employed to emulate a semi-infinite half-space, thereby excluding any boundary interference. A 1.2 m (1 D) void layer is introduced at the ground surface; the layer is assigned neither strength nor mass so that soil material can freely intrude into the domain once pile driving commences.

The soil domain is discretised into two regions: a refined mesh surrounding the steel casing and a coarser mesh for the far field. Radially, the zone adjacent to the casing is progressively condensed toward its centre; vertically, the penetration corridor is subdivided into uniform 0.1 m elements, whereas the remote soil is represented by elements ranging from 0.15 to 1.00 m in size. Boundary conditions fix all translational and rotational degrees of freedom at the base (x, y, z) and restrain lateral displacements and rotations on the vertical sides (x, y). Soil behaviour is governed by the Mohr–Coulomb constitutive model. Initial stresses are generated by the self-weight of the continuum and equilibrated through a predefined stress field in which the at-rest earth-pressure coefficient \({k}_{0}\) is defined as follows32:

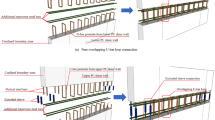

The steel casing is modelled with S4R shell elements. A uniform 0.15 m mesh is used over the majority of the surface; around every opening this is refined to 0.05 m quadrilaterals. The as-built casing contains holes on a 3 m grid: square openings 0.20 m × 0.20 m, diamond-shaped openings with major and minor axes of 0.34 m and 0.20 m, and elliptical openings whose major and minor axes are 0.32 m and 0.16 m, respectively. Figure 5 illustrates the numerical model for steel-casing installation in a riprap-armoured nearshore mudflat. The aperture area is approximately 0.04 m2 (Fig. 5a) and the drilling sequence is shown in Fig. 5b. A dynamic, explicit analysis step is employed with a 5-s penetration time. Penalty contact is prescribed between casing and soil and between rock and soil, with a Coulomb friction coefficient of 0.3. Riprap blocks are represented by 1.2 m × 0.6 m (major × minor axes) C3D8R elements; the casing is driven to a final embedment of 2.4 m. Given that the geometric parameters, including the long and short axes of the riprap clasts, the diameter of the steel casing, and its embedment depth, are integer multiples of 0.06 m, and considering the high degree of geometric regularity of the computational domain, a structured uniform quadrilateral mesh with an element size of 0.06 m was adopted to enhance both the convergence behaviour and the numerical accuracy of the simulation, as shown in Fig. 5c. To enhance computational efficiency and reduce costs, this study only simulates the scenario where the steel casing buckles at its toe after striking a single riprap block at mid-span of the long axis during installation; the riprap is treated as a rigid body. Through previous research, the accuracy of the numerical model and the rationality of parameter selection have been verified by Zhao et al.33 Due to space constraints, these aspects will not be elaborated further.

Three dimensional and planar schematic diagrams of numerical models. (a) Position and spacing of steel casing openings; (b) Schematic diagram of steel casing drilling scheme; (c) Shape, size and position of the stone; (d) Schematic diagram of the overall 3D numerical model; (e) Top and side views of soil.

Calculation of stress-concentration factor

The abrupt change in cross-section caused by an opening interrupts the smooth transfer of stress through the steel casing, producing severe stress concentration at the hole’s rim. This effect is conventionally quantified by the stress-concentration factor. In engineering practice, the stress-concentration factor is the standard measure of the severity of stress concentration. It is calculated as follows34,35,36:

where \({\alpha }_{\sigma }\) is the stress-concentration factor; \({\sigma }_{max}\) is the maximum stress value at the edge of the opening, MPa; \({\sigma }_{n}\) is the reference stress, MPa.

The reference stress is taken at the center-point between two adjacent holes on the outer circumference of the cross-section that passes through the stress-concentration zone, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

Figure 6 presents the steel casing after longitudinal cutting and circumferential unrolling. The horizontal axis denotes the angular position around the casing’s circumference, while the vertical labels A, B and C mark the hole rows that correspond to the A-, B- and C-sections shown in Fig. 5b. The maximum stress observation point around the opening in the figure is named \(i\times j\) (\(i\) = 1, 2, 3; \(j\) = 1, 2, 3, 4…), \(i\) represents the measurement point on sections A, B and C, while the value of \(j\) depends on the number of openings on each section of different casing shapes. The reference observation point for the reference stress is named \(ik\) (\(i\) = 1, 2, 3; \(k\) = a, b, c, d…), and the value of \(k\) is determined based on the number of reference measurement points on the respective cross-sections of different perforated casing shapes.

Physical and mechanical parameters

The physical and mechanical parameters of the main rock and soil layers obtained from the engineering site investigation and indoor test data are shown in Table 3.

The physical and mechanical parameters of the steel casing model are shown in Table 4.

The vibration machine model is APE200-6, with a static load \({F}_{0}\) of 100kN, a dynamic load amplitude of 2700 kN and a vibration frequency of 27.5 Hz. Therefore, the excitation force is \({F}_{d}=100+2700\text{sin}(172.8{t}_{s})\). The sine function curve of the excitation force shows a maximum excitation force of 2799.8 kN, as shown in Fig. 7.

Results and discussions

Impact of collision between steel casing and riprap on the openings

Stress analyses of steel casings

Figure 8 presents the Mises equivalent-stress distributions in the steel casings during jacking under unidirectional, bidirectional and star-pattern hole layouts. The corresponding time histories of the average stress at the openings of sections A–A, B–B and C–C are plotted in Fig. 9.

Figure 8 reveal pronounced stress concentration around the openings during construction, with peak stresses appearing on both lateral sides of each hole. For the A–A section, the high-stress zones measured along the Y-axis are 14.4 cm, 14.0 cm and 13.2 cm long for the unidirectional, bidirectional and star-perforated casings, respectively. This shows that the star-pattern perforation produces a more uniform stress field in the section. At the instant of rock impact (1.1 s) the Mises plots reveal a smooth, U-shaped transition between the high- and low-stress bands in the star-perforated casing, whereas the other layouts exhibit sharper gradients. Such gradual stress decay lessens fatigue damage under cyclic loading, enhances structural stability and improves the casing’s capacity to resist external forces. Figure 9 shows that the average hoop stress at the hole rises as the load is applied to the casing head. For the A–A section the mean values are 226.5 MPa, 225.0 MPa and 230.3 MPa for the unidirectional, bidirectional and star-pattern perforations, respectively; at B–B they drop to 185.3 MPa, 179.2 MPa and 175.3 MPa, and at C–C to 138.9 MPa, 116.9 MPa and 145.2 MPa. Because the hoop stresses in all three layouts at A–A are close to the steel’s yield strength, reinforcement is required at this level.

Stress concentration analyses at the opening of steel casings

The time-history of the stress-concentration factor at the openings of each perforated casing is shown in Fig. 10.

As shown in Fig. 10, the stress-concentration factor at the C–C cut-out of the steel casing fluctuates sharply, whereas the variations at the A–A and B–B cut-outs are comparatively gentle. This implies that, under the combined action of dynamic excitation and riprap reaction, the stress field around the C–C opening is highly non-uniform, rendering it the weakest region of the casing. Consequently, local reinforcement is imperative at this section to pre-empt fatigue damage. After the external excitation is removed at 5 s, the casing reaches a steady-state stress regime. The stress-concentration factor ranges measured at the edges of the unidirectional, bidirectional and star-shaped cut-outs are 1.14–1.78, 1.07–1.79 and 1.51–1.98, respectively. Although the star-shaped opening exhibits the narrowest band of stress-concentration factor, indicating superior structural stability and a more favourable overall stress pattern, it also registers the highest absolute values, and therefore the most pronounced stress concentration.

Under the condition A × 1, the elastic stress-concentration factor at the perforation edge of the unidirectional, bidirectional and star-shaped configurations ranges from 1.58–1.83, 1.43–1.61 and 1.60–1.96, respectively. For the bidirectional arrangement, the temporal evolution of stress-concentration factor along the A–A cross-section exhibits a plateau-like behaviour with the lowest ensemble average, implying a more homogeneous circumferential stress field. When the loading scenario is switched to B × 1, the corresponding stress-concentration factor intervals increase to 1.76–2.01, 1.68–1.79 and 1.66–2.04. A monotonic upward trend is observed as the perforation centroid migrates away from the casing crown, evidencing an aggravation of stress concentration. On the B–B section, both unidirectional and star-shaped schemes register peak stress-concentration factors approaching 2.0, signifying a pronounced biaxial stress-raising effect. Under C × 1, the stress-concentration factor envelopes expand further to 1.10–3.83, 1.04–3.67 and 1.34–3.47, respectively. Notably, the star-shaped pattern along the C–C plane demonstrates the most stable temporal trajectory and the narrowest confidence band, corroborating its superior capacity to redistribute stress fluctuations and thus offering a mechanically preferable perforation strategy.

Internal force analyses of steel casings after collision

The shear-force and bending-moment histories of unperforated, unidirectionally perforated, bidirectionally perforated and star-perforated steel casings subject to riprap impact are presented in Figs. 11 and 12.

As illustrated in Fig. 11, the shear force in the perforated steel casing decreases progressively from the top to approximately mid-height (about 4 m), thereafter reversing direction and increasing towards the base. At section A–A, the intact casing exhibits a shear force of 92.8 kN, whereas the unidirectional, bidirectional and star-perforated casings register 122.5 kN, 114.1 kN and 98.2 kN, corresponding to increases of 32.0%, 23.0% and 5.8%, respectively. At section B–B, the intact casing shear force is 12.7 kN; the three perforated configurations yield 26.4 kN, 26.5 kN and 22.7 kN, representing increments of 107.9%, 108.6% and 78.7%. At section C–C, the intact casing sustains 35.7 kN, while the perforated variants attain 39.8 kN, 52.3 kN and 39.5 kN, equivalent to rises of 11.5%, 46.5% and 10.6%.

Figure 12 indicates that the bending moments of the perforated steel casings progressively increase from the top to the mid-height (approximately 4 m), where the peak value occurs, and then diminish towards the base. At section A–A, the intact casing exhibits a bending moment of 140.2 kN·m; the unidirectional, bidirectional and star-perforated casings register 175.3 kN m, 160.3 kN·m and 163.9 kN·m, corresponding to increments of 25.0%, 14.3% and 16.9%, respectively. At section B–B, the intact casing sustains 311.8 kN·m, whereas the three perforated configurations attain 354.8 kN·m, 380.3 kN·m and 322.4 kN·m, equivalent to rises of 13.8%, 22.0% and 3.4%. At section C–C, the intact casing value is 198.1 kN·m; the perforated variants reach 249.3 kN·m, 257.6 kN·m and 240.0 kN·m, representing increases of 25.8%, 30.0% and 21.2%.

The foregoing results demonstrate that, under both vibratory excitation and riprap impact, perforated casings sustain substantially higher shear forces and bending moments than their unperforated counterparts. This deterioration is primarily attributed to the loss of material continuity introduced by the perforations, which reduces the effective cross-sectional area and, consequently, the global shear and flexural capacity. Moreover, the hole edges act as potent stress raisers, generating local stress intensities that markedly exceed the nominal values observed in the remainder of the section. This unfavorable stress distribution further leads to an increase in shear force and bending moment. Among the three types of openings, the star-shaped opening has the smallest increase in shear force and bending moment on the steel casing body. This is because on the star-shaped perforated section, there are three unperforated parts that are evenly distributed at equal angles around the circumference, forming a triangular support structure. This structure allows the force to be evenly distributed among the three parts, even if one part has a relatively weak bearing capacity, the area carried by the other two parts can still reach 2/3 of the total bearing area of the section, ensuring the stability of the overall structure.

The distribution law of axial forces on the steel casing body is shown in Fig. 13.

Figure 13 indicates that the axial force in all casings decays monotonically from the top to the toe. At any given elevation, the unperforated section exhibits the highest value, followed in descending order by the unidirectional, bidirectional and star-perforated configurations. Consequently, when the axial-force distribution is adopted as the performance metric, the star-shaped perforation scheme introduces the smallest reduction in axial capacity and is therefore the most favourable layout among the three opening patterns investigated.

Displacement analyses of steel casings

The computed vertical and horizontal displacement histories of the steel casings within a 5 s excitation window are depicted in Fig. 14.

Figure 14 reveals that, after 4 s, the rate of vertical displacement of the unperforated casing becomes lower than that of the perforated specimens. This reversal is ascribed to the inferior soil-discharging capacity of the intact wall, which generates a pronounced soil-plugging effect at the toe and raises the resultant shaft friction; the plug height is approximately one diameter (1 D). The perforation density also influences the vertical penetration: the unidirectionally perforated casing exhibits the largest settlement, followed by the bidirectionally perforated and star-perforated configurations. The maximum vertical displacements are − 5.69 m, − 5.65 m and − 5.66 m, respectively, a trend that accords with the experimental observations reported by Yue et al.37. At the Keqiao Seawall project and Longgang Seawall project sites, the peak vertical displacements of the unidirectionally perforated steel casing measured at 5 s were − 5.83 m and − 5.57 m, respectively, which agree closely with the finite-element predictions. However, under varying geological conditions, significant discrepancies in vertical displacement may occur among individual steel casings within the initial 5 s of penetration. Perforations act as drainage conduits, allowing pore water to dissipate from the surrounding soil and producing a measurable reduction in moisture content. The attendant increase in matric suction and effective stress translates directly into higher soil shear strength, which stiffens the lateral reaction along the casing and curtails vertical displacement. Owing to its lowest open-area ratio, the unidirectional configuration offers the most restricted drainage path. Consequently, it induces the smallest gain in shear strength and exhibits the largest settlement among the three perforation patterns.

The computed lateral friction distributions along the casing wall located on the side opposite to the riprap impact are shown in Fig. 15.

The Elastic Viscoelastic Fraction (EVF), defined as the volume fraction of a given constituent within an element and bounded between 0 and 1, is employed to quantify soil mass transport. The corresponding EVF contour plot for the soil–flow field is displayed in Fig. 16.

Figure 16 evidences a monotonic increase in horizontal displacement with perforation density after riprap impact in the mudflat environment. The intact casing registers 88.2 mm, whereas the unidirectional, bidirectional and star-perforated configurations reach 116.7 mm, 138.2 mm and 132 mm, respectively, at 5 s. Inspection of Fig. 16a reveals that the soil plug adjacent to the unperforated casing exhibits an extensive red zone (EVF = 1, i.e. pure soil) at the toe, while the bidirectionally perforated case displays a markedly reduced red region. The higher open-area ratio enhances soil discharge, diminishes the plug volume and, consequently, lowers the lateral reaction mobilised against casing movement.

Lateral friction traces extracted from the riprap-adjacent side (Fig. 15) show a monotonic increase with embedment depth for all configurations. Across the entire profile, the intact casing exhibits the highest resistance, whereas perforated variants mobilise progressively lower values. Averaged over the depth interval investigated, the side friction on the surface facing away from the impact amounts to 3.32 kPa for the unperforated reference; the corresponding means for the unidirectional, bidirectional and star-shaped schemes are 2.40 kPa, 0.72 kPa and 1.64 kPa, respectively, representing reductions of 27.7%, 78.3% and 50.6% relative to the intact condition.

Internal energy analyses of steel casings

The variation of internal energy over time during the sinking of steel casings under excitation force and collision with riprap under different opening methods is shown in Fig. 17.

The evolution of internal energy directly mirrors the spatiotemporal development of stresses within the casing wall; localized stress concentrations precipitate sharp rises in internal energy, providing the energetic driver for plastic flow and eventual fracture. Figure 17 shows an abrupt rise in internal energy at 1.1 s, coinciding with riprap impact. Across the entire penetration phase, perforated casings consistently exhibit higher internal energy than the intact reference, and the magnitude increases monotonically with perforation density. At 1.1 s, the unperforated casing stores 74.4 kJ, whereas the unidirectional, bidirectional and star-shaped schemes register 100.5 kJ, 103.8 kJ and 101.0 kJ, corresponding to increments of 35.1%, 39.5% and 35.8%, respectively. By 5.0 s, the intact casing reaches 215.2 kJ; the same three perforated configurations attain 306.2 kJ, 327.5 kJ and 345.9 kJ, representing further increases of 42.3%, 52.1% and 60.7% relative to the unperforated baseline. The progressive amplification of internal energy with hole density underscores the elevated propensity for plastic energy dissipation in perforated shells. Stress concentrations intensify at perforation edges as the number of apertures increases, expanding the high-gradient zone and amplifying the local energy density. The attendant reduction in effective cross-sectional area further distorts the global stress field, producing steep spatial gradients that drive internal energy accumulation. Consequently, the star-perforated casing surpasses the bidirectional configuration in internal energy at 3.9 s, corroborating the dominant role of perforation density in governing energy storage. In conjunction with Fig. 8c, the pronounced stress concentration at the toe of the star-perforated casing is directly responsible for its elevated internal energy relative to the other configurations.

Conclusion

The impact of openings on the mechanical behaviour of steel casings, including stress-concentration factors and their variation patterns during collisions with riprap, is investigated using the finite element method. Additionally, optimization strategies for the design of these openings are explored. The key findings are summarized as follows.

-

(1)

Perforations in steel casing reduce its effective load-bearing area, diminishing shear and bending resistance. Under vibration and riprap impact, perforated sections experience significantly higher shear and bending moments than intact casing. Star-shaped perforations have less adverse effect on shear, moment, and axial force than unidirectional or bidirectional patterns.

-

(2)

The stress-concentration factors of openings closer to the load application point exhibit a smoother and lower trend in their variation curves under dynamic loading and riprap reaction forces, indicating a more uniform stress distribution across the section. As the opening is positioned farther from the top of the casing, the stress-concentration factors at the openings progressively increase, making the stress concentration more pronounced. Compared with unidirectional and bidirectional perforated steel casings, the star-shaped perforated steel casing demonstrates a more stable variation trend in stress-concentration factors and more reasonable cross-sectional stress performance.

-

(3)

The soil-discharging capacity of a steel casing improves as the number of openings increases. These openings help curb soil intrusion at the toe of the casing and reduce penetration resistance, thus both horizontal and vertical displacements grow when the casing strikes riprap. However, the perforations introduce a non-uniform stress field, steep stress gradients and a marked build-up of internal strain energy within the casing. The findings provide a theoretical framework for optimizing the perforation pattern and construction procedure of steel casings driven through riprap in the macro-tidal flats of estuarine mudflats.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tabarestani, M. K. et al. Extent of riprap layer with different stone sizes around rectangular bridge piers with or without an attached collar. Sci. Iran. 22, 709–716. https://doi.org/10.24200/sci.2016.1897 (2015).

Huang, Z. Y. et al. Coupled computational fluid dynamics-discrete element method for simulating the interactions between ship-induced waves and riprap on restricted waterway banks. Phys. Fluids 36, 107140. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0230654 (2024).

Wang, Y. H. et al. Distribution and dissipation laws of excess pore water pressure based on pile-soil interface during pile-sinking in saturated clay. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 167, 107807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2023.107807 (2023).

Wang, H. Y. et al. Hydraulic fracture initiation for perforated wellbore coupled with the effect of fluid seepage. Energy Rep. 8, 10290–10298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2022.08.011 (2022).

Staubach, P. & Machacek, J. Influence of relative acceleration in saturated sand: Analytical approach and simulation of vibratory pile driving tests. Comput. Geotech. 112, 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2019.03.027 (2019).

Massarsch, K. R., Wersäll, C. & Fellenius, B. H. Vibratory driving of piles and sheet piles-state of practice. P. I. Civil Eng-Geotec. 175, 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1680/jgeen.20.00127 (2022).

Zirka, A. I., Osaulenko, L. L. & Savchenko, V. I. Stress concentrations close to circular holes in a cylindrical shell of medium thickness. Strength Mater. 4, 923–925. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01529687 (1972).

Kamalarajah, R., Stoffberg, W., Bull, J. W., et al. An investigation of stress factors for a circular hole in a cylindrical shell. In International Conference on Civil, Structural and Environmental Engineering Computing, Civil-Comp Press, Stirlingshire, UK 108, 43. https://doi.org/10.4203/ccp.108.43 (2015)

Ghazijahani, T. G., Jiao, H. & Holloway, D. Structural behavior of shells with different cutouts under compression: An experimental study. J. Constr. Steel Res. 105, 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcsr.2014.10.020 (2015).

Brunesi, E. & Nascimbene, R. Effects of structural openings on the buckling strength of cylindrical shells. Adv. Struct. Eng. 21, 2466–2482. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369433218764625 (2018).

Zhang, X. H. et al. Experimental and numerical analyses on buckling and strength failure of composite cylindrical shells under hydrostatic pressure. Ocean. Eng. 249, 110871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.110871 (2022).

Bakroon, M. et al. Numerical evaluation of buckling in steel pipe piles during vibratory installation. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 122, 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2018.08.003 (2019).

Sadamoto, S. et al. An effective meshfree reproducing kernel method for buckling analysis of cylindrical shells with and without cutouts. Comput. Mech. 59, 919–932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-017-1384-5 (2017).

Storozhuk, E. A., Chernyshenko, I. S. & Yatsura, A. V. Stress-strain state near a hole in a shear-compliant composite cylindrical shell with elliptical cross-section. Int. Appl. Mech. 54, 559–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10778-018-0909-8 (2018).

Gokyer, Y. & Sonmez, F. O. Topology optimization of cylindrical shells with cutouts for maximum buckling strength. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. 45, 13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40430-022-03941-w (2023).

Salahshour, S., Ong, M. C. & Nematzadeh, A. Numerical study on vibratory extraction of offshore wind turbine monopile foundations under sandy seabed condition. Ocean. Eng. 289, 116229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.116229 (2023).

Gao, L. et al. Vertical impedance of tapered piles considering the vertical reaction of surrounding soil and construction disturbance. Mar. Georesour. Geotec. 35, 1068–1076. https://doi.org/10.1080/1064119X.2017.1285379 (2017).

Wu, W. B. et al. Vertical dynamic impedance of tapered pile considering compacting effect. Math. Probl. Eng. 2013, 304856. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/304856 (2013).

Osthoff, D. & Grabe, J. Deformational behaviour of steel sheet piles during jacking. Comput. Geotech. 101, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2018.04.014 (2018).

Wang, D. et al. Large deformationfinite element analyses in geotechnical engineering. Comput. Geotech. 65, 104–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2014.12.005 (2015).

Qin, Z. P., Lai, Y. M. & Tian, Y. Study on failure mechanism of a plain irrigation reservoir soil bank slope under wind wave erosion. Nat. Hazards. 109, 567–592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-04849-9 (2021).

Qin, Z. P. et al. Stability behavior of a reservoir soil bank slope under freeze-thaw cycles in cold regions. Cold Reg Sci Technol https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2020.103181 (2020).

Yu, L. et al. Three-dimensional upper bound limit analysis of a deep soil-tunnel subjected to pore pressure based on the nonlinear Mohr-Coulomb criterion. Comput. Geotech. 41, 1023–1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2019.04.025 (2019).

Li, S. Q., Xia, J. H. & Zhang, P. Y. The initial stress line and modified Mohr-Coulomb criterions for undisturbed soil. Eng. Mech. 33, 116–122. https://doi.org/10.6052/j.issn.1000-4750.2014.06.0521 (2016).

Robert, D. J. A modified mohr-coulomb model to simulate the behavior of pipelines in unsaturated soils. Comput. Geotech. 91, 146–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2017.07.004 (2017).

Tang, J. B. et al. Strain localization of Mohr-Coulomb soils with non-associated plasticity based on micropolar continuum theory. J. Rock Mech. Geotechn. Eng. 15, 3316–3327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2023.02.029 (2023).

Ashmarin, Y. Theory of elastic stability of a cylindrical shell weakened by a circular hole. Soviet Appl. Mech. 8, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00885908 (1972).

Whenham, V. & Holeyman, A. Load transfers during vibratory driving. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 30, 1119–1135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-012-9527-0 (2012).

Staubach, P. et al. Long-term response of piles to cyclic lateral loading following vibratory and impact driving in water-saturated sand. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. 148, 04022097. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0002906 (2022).

Daryaei, R. et al. Numerical evaluation of the soil behavior during pipe-pile installation using impact and vibratory driving in sand. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 134, 106177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2020.106177 (2020).

Sun, Z. et al. Ground and pile vibrations induced by pile driving. Buildings 13, 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13081884 (2023).

Mesri, G. & Hayat, T. M. The coefficient of earth pressure at rest. Can. Geotech. J. 30, 647–666. https://doi.org/10.1139/t93-056 (1993).

Zhao, W. S. et al. Numerical investigation on the penetration process of steel casings in riprap environment of estuarine mudflats. Sci. Rep.-UK 15, 7921. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92668-4 (2025).

Yang, Y. F. et al. Experimental and numerical investigation on stress concentration factor of large-scale welded tubular T-joints. Ocean. Eng. 320, 120337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2025.120337 (2025).

Lagoda, T., Kurek, M. & Malecka, J. Fatigue strength under combined bending and torsion proportional loading of bronze specimens with and without geometric notch. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mec. 133, 104605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2024.104605 (2024).

Hu, C. et al. Experimental and Numerical Investigation on Stress Concentration Factors of Offshore Steel Tubular Column-to-Steel Beam Connections. Buildings 14, 2004. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14072004 (2024).

Yue, T. S. et al. Test and analysis of bearing capacity of perforated pipe pile. Rock Soil Mech. 37, 415–420. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2016.S2.054 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by Longgang City Water Resources Management Department, Shaoxing Keqiao District Water Resources Management Department, Huzhou Nanxun District Government and related engineering participating enterprises. The authors thank their supporting for providing the necessary guidance, financial support and basic data.

Funding

This research was supported by the Nanxun Scholars Program of ZJWEU (RC2024011063).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology was contributed by Zipeng Qin, Weishun Zhao and Yan Tian; Formal analysis, investigation and data collection were contributed by Huiqiong Wang, Erjin Xu, Zhongzhu Lin, Ping Shen, Junfa Hu, Lingling Ji, Xiaowei Yang and Kaifang Wang; Writing—original draft preparation, was contributed by Zipeng Qin, Weishun Zhao and Yan Tian; Writing —review and editing, was contributed by all the authors; Funding acquisition was contributed by Zipeng Qin and Yan Tian; Resources were contributed by Huiqiong Wang, Erjin Xu, Zhongzhu Lin, Ping Shen, Junfa Hu, Lingling Ji, Xiaowei Yang and Kaifang Wang; Supervision was contributed by Huiqiong Wang, Erjin Xu, Zhongzhu Lin and Yan Tian.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, Z., Zhao, W., Wang, H. et al. Numerical investigation of steel-casing opening design for penetration through riprap in a macro-tidal estuarine mudflat. Sci Rep 15, 43258 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28974-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28974-8