Abstract

The permeability performance of the coal seam floor is an important basis for the assessment and prevention of water inundation disasters in the floor, and the water pressure test is an important means to obtain this parameter. The traditional water pressure test has limitations such as large construction volume, low testing accuracy and small data volume, and cannot meet the testing requirements of rock strata permeability performance under the condition of deep thick base plate impermeable layer. This paper presents an efficient and precise improved water pressure test method and applies it to the study of in-situ permeability performance changes of floor rock strata affected by mining activities. The improved water pressure test method of single borehole, movable double embolization and graded circulation was adopted to conduct tests on the unmined and mined affected areas of the No. 9 coal seam floor of Xipang Mine, Dongpang Well. The P-Q curves, permeability and other parameters of each rock layer of the floor were obtained. Combined with the Mann-Whitney U test, The variation laws of permeability performance of different rock strata affected by mining activities were systematically analyzed. Research shows that the improved water pressure test method is significantly superior to the traditional method in terms of test efficiency, borehole utilization rate, etc. The permeability performance of coal seam floor is significantly affected by mining activities. Mining activities reduce the permeability recovery capacity of rock strata, and the permeability performance of different strata shows differentiated responses to mining activities. The improved water pressure test method proposed in this paper provides a technical means for the refined testing of the permeability performance of the floor rock strata. The research results are helpful for accurately identifying the weak areas of the floor and assessing the risk of water hazards, which has important engineering guidance value for promoting the safe and efficient mining of deep coal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As an important basic energy source, the global coal consumption reached 8.77 billion tons in 2024, accounting for 35% of the global energy structure. As the largest energy consumer in the world, China accounts for 58% of the global coal consumption and 53.2% of the national total energy consumption, which shows that coal plays an important role in economic development1,2. However, coal mining is often accompanied by a series of disasters, among which floor water inrush is one of the major disasters that threaten mine safety production3,4. Due to increased attention from both government and industry on the prevention and control of floor water inrush hazards, coupled with the continuous development of advanced technologies and methodologies for disaster prediction and mitigation, the frequency and severity of water inrush incidents have steadily declined5 (Fig. 1). Since 2000, a total of 56 floor water inrush accidents have been recorded in Chinese coal mines, with a clear downward trend over time. After 2018, only one such incident occurred, located in Hebei Province, indicating a transition of floor water inrush events in China’s coal mines from frequent occurrences to rare, isolated cases. Notably, Hebei Province, as a major coal-producing region in China, accounts for 48.21% of the nation’s total floor water hazard incidents. Owing to its long history of intensive mining, shallow coal resources have been largely depleted, resulting in progressively deeper mining operations and an escalating risk of water inrush6,7,8,9. During coal seam extraction, the floor strata serve as critical barriers preventing the upward migration of underlying confined aquifers. The permeability characteristics of these floor rocks are essential parameters for establishing a scientifically sound risk assessment framework and form the foundation for designing effective prevention and control strategies, as well as evaluating their performance10,11,12,13. However, conventional laboratory-based permeability testing methods fail to accurately represent in-situ conditions due to disturbances in stress states and scale effects14,15,16. Furthermore, traditional in-situ water pressure testing techniques are constrained by low efficiency and limited capacity to test individual layers, making them inadequate for detailed characterization of stratified floor systems with thick impermeable layers in deep coal seams. Consequently, the development of more efficient and accurate in-situ testing technologies for assessing the permeability of coal seam floor strata has become a pressing scientific and engineering challenge in the field of deep mine water hazard prevention.

Currently, the evaluation of coal seam floor permeability under in-situ conditions is predominantly conducted using the water pressure test, hereinafter referred to as the “conventional water pressure test.” This method requires the construction of at least two boreholes for each testing section: one designated for water injection and the other for observation. The non-testing segments are isolated using casing, and the borehole openings are subsequently sealed with flanges. Upon initiation of the test, water is injected into the injection borehole, during which the injection pressure, injection flow rate, and observed water pressure in the monitoring borehole are recorded. The permeability characteristics of the target section are then analyzed based on the pressure differential between the two boreholes and the temporal relationship between flow rate and pressure17,18,19,20. Huang et al. drilled four boreholes into the tunnel floor and conducted conventional water pressure tests on three strata located at depths of 8 m, 10 m, and 16 m to investigate variations in hydraulic conductivity within deep rock formations21. Wu et al. performed conventional water pressure tests on three sections of the roadway floor, employing repeated water injection to evaluate the water-sealing capacity of intact floor rock masses22. Huang et al. carried out a conventional water pressure test on two test sections using three boreholes with repeated water injection to analyze the hydraulic behavior of fault zones23. Zhang et al. employed a double-packer system to conduct water injection tests on three intervals within a single borehole under relatively low hydraulic pressure (up to a maximum of 1.0 MPa) to assess the potential risk of water inrush in fault zones24.

In the field of water conservancy and hydropower engineering, the water pressure test is a well-established method for assessing the permeability of rock and soil formations. Although it shares the same fundamental principle as the tests used in mining, the specific methodology differs significantly. Originally developed for evaluating dam foundation rock masses, this technique has evolved over nearly a century into a comprehensive and standardized approach, supported by a mature theoretical framework and widely recognized technical specifications25,26. Typically, in borehole testing, a double-packer system is employed to isolate the target section, with the annular sealed interval serving as the test zone. Water is then injected into this isolated segment. Upon completion of the test for a given section, the packers are repositioned to isolate the next test segment, followed by initiation of water injection. This procedure is repeated sequentially until all designated sections have been evaluated. The standard water injection protocol comprises either a three-pressure-level, five-stage cycle or a five-pressure-level, eight-stage cycle. In the former, the pressure sequence includes pressurization stages at 0.3, 0.6, and 1.0 MPa, followed by two depressurization stages at 0.6 and 0.3 MPa. The latter includes additional intermediate pressure levels to achieve more refined hydraulic characterization27,28,29,30,31. During the testing process, the water injection pressure and flow rate at each stage were systematically recorded; subsequently, the pressure-flow (P-Q) curve was plotted and its type determined. The permeability rate of the test section was calculated, and a comprehensive analysis of the rock strata’s permeability performance was conducted.

A comparison between the traditional water pressure test and the water pressure testing methods employed in the field of water conservancy and hydropower engineering reveals that the conventional approach suffers from low testing accuracy and high drilling construction costs. These limitations become particularly pronounced in deep coal seams characterized by thick floor strata and impermeable layers. In traditional testing practices, each borehole is limited to assessing only one test section. Consequently, precise evaluation of the floor strata necessitates a significant number of boreholes, leading to increased construction expenses. To mitigate drilling costs, multiple rock layers with varying lithologies are typically grouped within a single test section, which compromises the accuracy of permeability measurements and fails to support a precise assessment of the floor strata’s hydraulic properties. In the deep coal seams of Hebei Province, the impermeable layer beneath the lowest minable coal seam averages 100 to 200 m in thickness and can withstand water pressures exceeding 10 MPa. Under such deep geological conditions, the use of traditional water pressure testing requires extensive drilling, with each borehole covering a relatively long test interval. Enhancing measurement accuracy would further escalate drilling efforts. While advanced water pressure testing techniques from water conservancy and hydropower engineering enable permeability evaluation at discrete depths within a single borehole, their application in deep coal seams is constrained by significantly lower injection pressures compared to the actual in-situ hydrostatic pressures. As a result, these methods cannot reliably reflect the true permeability behavior of rock strata under real hydrogeological conditions. Therefore, there is a critical need to develop a precise and efficient method for evaluating the permeability characteristics of deep coal seam floor strata.

This paper presents an enhanced water pressure testing method tailored for floor rock strata in deep coal seams and applies it to Xipangjing Mine, a representative deep confined mine within the North China Coalfield, to investigate the permeability characteristics of the No. 9 coal seam floor. Boreholes were systematically designed and constructed in both unmined and active mining areas, enabling in situ evaluation of seepage behavior and permeability across multiple strata through the improved testing approach. The results validate the feasibility and reliability of the proposed method and provide insights into the influence of mining activities on the permeability evolution of floor strata. The findings offer a scientific foundation and technical support for safety assessment, risk prediction, and preventive strategies in pressure mining operations.

Research background

General situation of the study area

The Xipang Well of Dongpang Mine is situated in Xingtai City, Hebei Province, China, with its geographical location depicted in Fig. 2. It is located in the middle of the eastern foot of Taihang Mountain, with high terrain in the west and low terrain in the east, and belongs to the northwest boundary of Baiquan hydrogeological unit in Hanxing. As shown in Fig. 3, the coal-bearing strata in the mine field are Carboniferous-Permian, which belong to Shanxi Formation of Lower Permian, Taiyuan Formation of Upper Carboniferous and benxi formation of Middle Carboniferous from top to bottom, with a total of 17 coal layers. No.2 coal seam in Shanxi Formation and No.9 coal seam in Taiyuan Formation are stable thick coal seams, among which No.9 coal seam is the main coal seam in Xipangjing, with a thickness of 0.86 ~ 12.53 m (average 6.55 m). The Permian overlying strata are directly Cenozoic Quaternary strata, and the Ordovician strata are coal-bearing strata base.

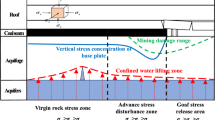

The aquifers influenced by the mining of the No. 9 coal seam include the Daqing limestone, Benxi limestone, and Ordovician limestone formations. Among these, the Daqing and Benxi limestones exhibit relatively low water richness and thus pose minimal threat to coal seam extraction. In contrast, the Ordovician limestone features well-developed karst fractures, demonstrating high water richness and favorable recharge conditions. The water head of the Ordovician limestone aquifer exceeds that of the No. 9 coal seam, representing a typical case of pressure mining in North China-type coalfields. As mining depth increases, the water pressure within the Ordovician limestone aquifer progressively rises. At depths exceeding − 300 m, the water inrush coefficient for the coal seam typically surpasses 0.1 MPa/m, indicating a complex hydrogeological environment.

Experimental procedures

Experimental method

The improved water pressure test process mainly refers to the water pressure test in the field of water conservancy and hydropower engineering, the pressure water test of three pressure and five stages is carried out to test the strata of coal seam floor affected by mining. Based on the ₁ water form test standards commonly used in hydraulic and hydropower projects, the two positions that were affected by exploitation were tested. In this ₄ form, the form was P₁, P₂, P₃, P₄ (= P₂), and P₅ (= P₁). The rates and pressure-flow (P-Q) curves for each layer of the base board were obtained. Analyze and judge the initial state and the permeability of the floor strata affected by mining.

The two-end sealing and measuring device is utilized for pressurized water injection in boreholes. The testing system primarily consists of two components: the packer (including the plug and its control mechanism) and the pressure-water measuring instrument (comprising a pressure gauge and flow meter). The packer is a device capable of expanding at both ends while enabling pressurization in the middle section. Prior to expansion, the packer allows for the attachment or detachment of the pressurized water extension rod at its end, enabling free movement within the borehole. Once the pressurized water section reaches the designated position, the packer control mechanism injects high-pressure water into the packer, causing it to expand. Subsequently, the test section can be sealed off and pressurized incrementally via the pressurized water control mechanism. Due to variations in pore, fracture, and filling conditions within rock strata, as well as the influence of water pressure on water injection volume in the isolated section, the pressure-water measuring instrument can obtain the stable flow rate of the test section under different pressure conditions. Figure 4 illustrates the schematic diagram of the pressurized water test principle, while Fig. 5 depicts the field setup for the pressurized water test.

Experimental scheme design

Optimization of drilling layout and trial section division

In order to investigate the impact of mining on the permeability of various strata in the coal floor, considering factors such as mining conditions, hydrogeological characteristics, and electrical conductivity, the location of Lane B1 in the northern wing track, far from the mining area, was selected as the region unaffected by mining, as illustrated in Fig. 6(a). The area near the stop-mining line of the belt lane of the 9301 working face was chosen as the region affected by mining, where a pressurized water test was conducted. This approach enabled the acquisition of the permeability properties of each rock stratum of the coal seam floor both without and under the influence of mining. The design and study focused on a horizon 10 m below the interface between Coal Seam No. 9 and the Ordovician limestone top.

The drilling field is located at the B1 position of the main lane of the north wing track, approximately 5 m outside the closed wall of the belt lane of the 9301 working face. The design specifies that the final hole level extends 10 m into the Ordovician limestone. Borehole Y1 was constructed at the B1 position of the main lane of the north wing track, as depicted in Fig. 6(a). The orientation of the main lane is 45°, the formation dip angle is −17°, the drilling orientation is 90°, the dip angle is −50°, and the hole depth is 99.09 m. Borehole Y2 was constructed approximately 5 m outside the closed wall of the belt lane in the 9301 working face, as shown in Fig. 6(b). The bearing of the belt lane is 27°, the formation inclination is 8.5°, the bearing of the borehole is 266°, the inclination is −27°, and the hole depth is 91.38 m. The entire borehole lies within the range of advance supporting pressure of the goaf, with only 24.98 m entering directly beneath the goaf. Refer to Fig. 6; Table 1 for the lithology, thickness, and test section division of each rock layer on the bottom floor of boreholes Y1 and Y2.

Three-stage water pressure configuration

The pressure settings at different stages are critical parameters that significantly influence the test results in pressurized water tests. Given that the water pressure at the bottom of the waterproof layer on the floor of Coal Seam No. 9 far exceeds 1 MPa, employing the conventional three-level pressure in water pressure testing fails to adequately reflect the true permeability characteristics of the rock strata. To scientifically and reasonably determine the three-level pressure, the actual seepage conditions were analyzed, and the bearing pressure capacity of the rock strata was considered. Consequently, the three-level pressures for the water pressure test were set at 4 MPa, 9 MPa, and 14 MPa.

The minimum pressure P₁ is determined based on the actual hydrostatic pressure exerted on the formation. In recent years, the groundwater level of the Ordovician limestone aquifer in the mining area has stabilized at approximately + 70 m, while the elevation of the top surface of the Ordovician limestone in the test area is around − 330 m. This results in a hydraulic pressure of approximately 4 MPa acting on the top surface of the formation, leading to the selection of P₁ = 4 MPa. The maximum pressure P₃ is established with reference to the formation’s fracture initiation pressure, fracture reopening pressure near the test site, and the upper limit of conventional water pressure testing. A directional hydraulic fracturing project was conducted in the strata between the No. 9 coal seam and the Great Blue Limestone in the vicinity of the test area. Statistical analysis of fracturing data from 115 out of 110 pressure injection boreholes revealed a minimum fracture initiation pressure of 20 MPa. Additionally, hydraulic fracturing performed near the top surface of the Ordovician limestone in borehole Y1 yielded an initial fracture pressure of 25.30 MPa and a fracture reopening pressure of 21.74 MPa. Conventional water pressure tests typically apply pressures in the range of 10–15 MPa. Based on data from the roof directional fracturing project and ash fracturing tests, the estimated fracture initiation pressure for the formation in the test section ranges from 20 to 26 MPa, with fracture reopening pressures between 18 and 22 MPa. To ensure that the formation remains intact and fractures do not propagate under the maximum test pressure, P₃ is conservatively set at 14 MPa—approximately 70% of the average fracture reopening pressure. Intermediate pressures P₂ and P₄ are set at 9 MPa, representing the midpoint between the selected minimum and maximum pressures. Furthermore, the test area is influenced by mining activities. Given that the test location lies within the advanced abutment pressure zone ahead of the goaf, and to facilitate direct comparison between data from boreholes Y1 and Y2, the third-level test pressure is maintained consistently across both locations.

Testing procedure

Upon the completion of drilling construction, hole washing and test preparation should be conducted as required, followed by the initiation of the pressure water test24,25. Initially, the embolization device is delivered to the designated position using a pressure water extension rod. The embolization expansion isolation test section is then pressurized into five stages at 4, 9, 14, 9, and 4 MPa, respectively. Subsequently, the embolization pressure is relieved, transitioning to the next test section, and this process of embolization expansion, pressure water application, and embolization pressure relief is repeated until the testing is complete. During the pressure water application, if the maximum power of the pump fails to achieve the preset pressure, the operational power of the pump should be slightly reduced to maintain a linear relationship between pressure and flow.

Data processing

The primary outcomes of the pressurized water test include the pressure-flow (P-Q) curve and water permeability. The test data were systematically organized to plot the P-Q curve and classify its type. During the plotting process. Test points were indicated with dotted lines, while the pressure-increasing stages (P₁, P₂, and P₃) were represented by solid lines. Conversely, the pressure-decreasing stages (P₃, P₄, and P₅) were depicted using dashed lines. Based on the shape of the P-Q curve, the curve type can be determined. These curves can generally be categorized into five fundamental types: A-type (laminar flow), B-type (turbulent flow), C-type (expansion), D-type (erosion), E-type (filling), as well as various compound types. The permeability of the test section q is calculated according to formula 1:

In Formula (1), q represents the water permeability of each test section, unit is Lu(Lugeon unit, 1 Lu = 1 L/min·m·MPa); L denotes the length of the trial section, which is 0.5 m. Qi is the calculated flow rate for phase i, expressed in liters per minute L/min; Pi indicates the pressure of the test section during stage i, measured in megapascals (MPa).

The permeability recovery coefficient k was employed to evaluate the permeability performance restoration capacity of the test section following high-pressure water injection. Typically, the value of k ranges between 0 and 1. A value of k closer to 1 indicates a more complete recovery of the rock layer’s permeability after high-pressure water injection, reflecting a stronger capacity for permeability performance restoration. Conversely, a value closer to 0 signifies a weaker restoration capacity. The permeability recovery coefficient k is calculated using Eq. 2.

In Eq. (2), k is the permeability recovery coefficient, a dimensionless quantity; \(\:{q}_{p1}\) represents the permeability at the third stage (P₁) of the water pressure test, with the unit of Lu. \(\:{q}_{p3}\) represents the permeability at the third stage (P₃) of the water pressure test, with the unit of Lu. \(\:{q}_{p5}\) represents the permeability at the third stage (P₅) of the water pressure test, with the unit of Lu.

Sources of error and countermeasures

Source of error

Test errors may arise from equipment limitations, geological complexities, and operational inaccuracies. Equipment-related factors include packer failure, measurement inaccuracies of instruments, and fluctuations in the water supply system. Packer degradation due to aging or wear can lead to water leakage, resulting in recorded flow rates exceeding the actual volume injected into the rock formation. According to Eq. (1), this discrepancy causes an overestimation of the calculated permeability, thereby inflating the assessed permeability of the rock layer. Pressure and flow sensors inherently possess measurement uncertainties, which may be exacerbated under high-pressure conditions. While such errors may influence the precision of fine-scale permeability assessments, they do not significantly alter the interpretation of overall trends. Fluctuations in the water supply system can induce variations in pressure and flow within the test section, interfering with the identification of the stable seepage phase. Insufficient water supply capacity may prevent the pressure pump from meeting required test pressures, thereby severely compromising test execution. Geologically induced errors stem from stratum heterogeneity and undetected subsurface structures. Significant spatial variability in lithology, porosity, and micro-fracture development within coal seam floor strata implies that data from a single test section reflect only localized permeability characteristics and cannot reliably represent the average properties of the entire formation. Operationally, inaccurate packer placement may result in the inclusion of non-target strata within the test interval, leading to biased data interpretation.

Countermeasures

First, conduct equipment reliability tests. Prior to testing, lower the packer into the designated section of the drilling casing. Expand the packer using a hydraulic pump and maintain the expanded state for 10 min. Monitor the connection between the embolization control unit and the pipeline, ensuring that the pressure drop does not exceed 0.2 MPa. Subsequently, perform water injection circulation in the casing section to evaluate the sealing performance of both the water injection control unit and the packer, with a stable flow rate required to be maintained at 0 L/min. High-pressure-resistant and high-precision flowmeters and pressure gauges shall be selected and calibrated prior to the experiment. Standardized operational procedures shall then be implemented, with test activities strictly conducted in accordance with established protocols. The position of the packer shall be recorded based on drilling construction data. An automated data acquisition system will be employed for continuous data recording, supplemented by a dual-person verification mechanism to minimize operational errors. Furthermore, prior to the experiment, a detailed test plan was developed in coordination with the mine dispatching department. Testing was scheduled during periods of low underground water consumption to mitigate potential interference from sudden fluctuations in water pressure and ensure measurement accuracy.

Evaluation of the experimental results

Analysis of permeability based on P-Q curve

There are substantial variations in the permeability characteristics across each layer and interval of the coal seam floor. Mining activities can alter the fracture development and permeability properties of rock strata. The P-Q curves of rock strata in regions unaffected by mining predominantly exhibit laminar flow and erosion types, with generally low permeability. In contrast, the P-Q curves of rock strata in mined regions are primarily characterized by erosion and turbulent types, indicating an overall improvement in permeability.

Carbonaceous mudstone

Two hydraulic tests were conducted in the carbonaceous mudstone of borehole Y1. During the third stage, the preset pressure was not achieved, and the P-Q curves (as shown in Fig. 7) exhibited characteristics of laminar flow. The permeability coefficients for the fifth stage were measured as 1.56 Lu and 1.77 Lu, respectively, indicating weakly permeable strata. Two water pressure tests were also attempted in the carbonaceous mudstone of borehole Y2; however, these tests failed due to friction between the sealing device and the rock blocks on the hole wall during the swelling sealing process.

Comparing the test results from two boreholes, it is evident that mining activities have significantly altered the integrity of the carbonaceous mudstone. In areas unaffected by mining, the rock exhibits a laminar flow structure with low permeability. Conversely, in mined areas, the advance supporting pressure has severely fractured the rock mass, rendering the testing process unfeasible. This clearly demonstrates that mining exerts a substantial destructive impact on the carbonaceous mudstone, leading to a marked reduction in the structural integrity of the rock layer.

Bauxite mudstone

Two water pressure tests were conducted in the bauxite mudstone of the Y1 borehole. During the third stage, the preset pressure was not achieved, and the P-Q curves (as shown in Fig. 7) exhibited laminar flow characteristics. The permeability values for the fifth stage were measured at 1.84 Lu and 2.21 Lu, respectively, indicating that these strata are classified as weakly permeable.

Two water pressure tests were conducted in the bauxite mudstone of the Y2 borehole. Only the first stage achieved the preset pressure, and the planned five-stage, three-pressure-level testing scheme could not be fully implemented. The first test section included two pressure levels across three stages, while the second test section added a pressure reduction stage to the same two pressure levels and three stages. By comparing the flow changes during both the pressure increase and decrease phases for the two test sections, it was observed that the flow during the pressure drop phase was significantly higher than during the pressure increase phase, indicating a washout pattern. Furthermore, the pressure drop phase in the second test section exhibited laminar flow characteristics. The permeability values of the final stage in each test section were measured at 19.64 Lu and 17.25 Lu, respectively, classifying the formation as moderately permeable.

Compared with the test results from two boreholes, mining activities substantially alter the permeability characteristics of bauxite mudstone. The region unaffected by mining exhibits weak permeability with a laminar flow pattern, whereas the mined area demonstrates enhanced water permeability due to erosion.

Fine sandstone

Five water pressure tests were conducted in the fine sandstone of Y1 borehole. Only the third stage of the fifth test section reached the preset pressure, and the P-Q curves of each test section (Fig. 7) exhibited significant differences. The pressure increase phase generally demonstrated characteristics of expansion. Based on the flow difference between the fourth stage and the second stage, the primary features of filling or erosion were observed in each test section. The flow in the first and fifth stages was essentially identical. In conjunction with the observation of a substantial amount of rock powder being carried in the water after depressurization, it is inferred that the filling or erosion characteristics of the P-Q curve type are attributed to variations in the filling state of rock powder within fractures during the depressurization phase. This indicates that the rock layer possesses evident erosion characteristics. The fifth stage of the first four test sections exhibited water permeability values ranging from 1.31 to 1.99 Lu, which categorizes them as weakly permeable formations. Conversely, the fifth stage of the fifth test section displayed a water permeability value of 0.93 Lu, classifying it as a micro-permeable formation.

Six water pressure tests were conducted in the fine sandstone of the Y2 borehole. In the first test section, only the third stage failed to reach the preset pressure. The P-Q curves of each test section exhibited significant differences. The pressure increase phase generally demonstrated characteristics of turbulent flow and expansion. In the fifth test section, the flow rate during the fifth stage was notably higher than that of the first stage. The backflow phenomenon observed during the pressure relief process was consistent with that of the Y1 borehole at the same stratigraphic level, indicating that the rock layer belongs to an erosion type. The water permeability of the first four test sections during the fifth stage ranged from 0.00 to 0.15 Lu, classifying these sections as very slightly permeable formations. Conversely, the water permeability of the last two test sections was measured at 3.04 Lu and 2.31 Lu, respectively, categorizing them as weakly permeable formations.

Compared with the test results of two boreholes, the influence of mining on the permeability of fine sandstone formations is more complex. In areas unaffected by mining, the permeability exhibits an extended flow pattern with overall weak permeability. In contrast, in areas affected by mining, the permeability follows a turbulent flow pattern. Specifically, the permeability of the upper formation is weakened, while that of the lower formation is enhanced.

Benxi limestone

Two pressure water tests were conducted in the Benxi Limestone of the Y1 borehole. The P-Q curve of the first test section (Fig. 7) exhibits an extended type. In the second test section, the pressure increase stage demonstrates expansion characteristics, while the pressure decrease stage shows laminar flow characteristics. Notably, the flow rate during the pressure decrease stage is lower than that during the pressure increase stage, indicating filling characteristics. The permeability values of the fifth stage are 0.27Lu and 1.35Lu, respectively, classifying this formation as weakly to slightly permeable.

Two water pressure tests were performed in the Benxi Limestone of the Y2 borehole. The P-Q curve of the first test section exhibited turbulent flow characteristics during the pressure increase stage and laminar flow characteristics during the pressure decrease stage. Notably, the flow rate in the fifth stage was significantly higher than that in the first stage, indicating evident erosion characteristics. In contrast, the second test section demonstrated purely turbulent flow behavior. The permeability coefficients of the fifth stage for the two sections were measured as 2.72 Lu and 0.00 Lu, respectively, classifying the formation as very slightly to weakly permeable.

Compared with the test results from two boreholes, mining activities have a minimal impact on the Benxi limestone. The regions unaffected by mining exhibit expansive and filling characteristics, with weak permeability. In contrast, the region influenced by mining shows turbulent flow; however, the change in water permeability is not significant. These findings suggest that the Benxi limestone demonstrates a low sensitivity to mining activities.

Coal seam No. 10

A water pressure test was conducted on the No. 10 coal seam in borehole Y1. In the third stage, the preset pressure was not achieved, and the P-Q curve (Fig. 7) exhibited laminar flow characteristics. The water permeability of the fifth stage was measured at 2.01 Lu, indicating a weakly permeable stratum. A similar water pressure test was performed on the No. 10 coal seam in borehole Y2. The P-Q curve displayed filling-type behavior, with zero flow rates recorded in both the first and fifth stages. The water permeability of the fifth stage was determined to be 0.00 Lu, classifying it as a very slightly permeable formation.

By comparing the test results from the two boreholes, it is evident that mining activities have significantly altered the permeability characteristics of the No. 10 coal seam. The unmined area exhibits laminar flow with weak permeability, whereas the mined area demonstrates filling-type behavior and a substantial reduction in water permeability.

Bauxite formation

Five water pressure tests were conducted in the bauxite of the Y1 borehole. The third stage of the first and second test sections failed to reach the preset pressure. With the exception of the P-Q curve for the first test section (Fig. 7), which exhibits laminar flow characteristics, the other four sections demonstrate erosion-type behavior. Erosion characteristics are primarily reflected in the difference in flow rates between the second and fourth stages of the pressure water test, where the flow rate in the fourth stage is significantly higher than that in the second stage. There was no substantial difference observed between the first and fifth stages. The permeability of the fifth stage ranges from 0.00 to 1.52 Lu, indicating a weakly to micro-permeable formation.

Four water pressure tests were conducted in the bauxite rock of the Y2 borehole. Only the third stage of the fourth test section achieved the preset pressure. The P-Q curves exhibited an erosive type, with the flow rate during the depressurization phase being significantly higher than that during the pressurization phase. The permeability of the fifth stage ranged from 4.44 to 6.83 Lu, indicating a weakly permeable formation.

Compared with the test results of two boreholes, mining activities have substantially increased the permeability of bauxite rock formations. Rock formations unaffected by mining exhibit primarily erosive characteristics, and their seepage rates can recover to baseline levels following high-pressure water erosion, albeit with relatively weak permeability. In contrast, rock formations affected by mining demonstrate a significant increase in seepage rate and water permeability after high-pressure water erosion.

Ordovician limestone

Four water pressure tests were conducted in the Ordovician limestone of the Y1 borehole. The P-Q curves (Fig. 7) were all classified as erosive types. The erosive characteristics were evident in the differences in flow rates between the second and fourth stages; specifically, the flow rate in the fourth stage was significantly higher than that in the second stage. In contrast, the flow rates in the first and fifth stages were zero. Notably, the permeability of the fifth stage was measured at 0Lu, indicating that it belongs to a stratum with extremely low permeability.

The four-pressure water injection test was conducted in the Ordovician limestone of the Y2 borehole. In the third stage, the pre-set pressure was not achieved, and all P-Q curves exhibited erosion-type characteristics. During the pressure increase phase, only the second testing section demonstrated laminar flow characteristics, whereas the remaining sections showed extended flow characteristics. Notably, the flow rate during the pressure relief phase was significantly higher than that during the pressure increase phase, indicating pronounced erosion-type behavior. The permeability of the fifth stage ranged from 5.82 to 11.44 Lu, classifying it as a weakly to moderately permeable formation.

Compared with the test results of two boreholes, mining activities have substantially altered the permeability characteristics of Ordovician limestone. Both rock formations unaffected and affected by mining exhibit an erosion-type behavior. However, after high-pressure water erosion, the seepage rate of the rock formations unaffected by mining returns to its original level, indicating very weak permeability. In contrast, the rock formations affected by mining demonstrate a significant increase in seepage rate and permeability following high-pressure water erosion.

Permeability analysis utilizing the Mann-Whitney U test

In order to further investigate the impact of mining on the permeability of each rock layer in the coal seam floor, the permeability values for the first, third, and fifth stages of the hydraulic pressure tests in each test section were calculated, as presented in Fig. 8. Subsequently, the permeability variation curves for each layer of boreholes Y1 and Y2 were plotted, and a multi-dimensional longitudinal and transverse analysis of boreholes Y1 and Y2 was conducted, as detailed in Tables 2 and 3. Specifically, the analysis proceeded as follows: First, a longitudinal comparison of the permeability values for the first (\(\:{q}_{p1}\)) and fifth (\(\:{q}_{p5}\)) stages in boreholes Y1 and Y2 was performed. Second, the longitudinal differences in permeability between the third and first stages (\(\:{q}_{p3}-{q}_{p1}\)) and between the third and fifth stages (\(\:{q}_{p3}-{q}_{p5}\)) were analyzed. Finally, a transverse analysis was carried out to evaluate the permeability of formations at the first (\(\:{q}_{p1}\)), third \(\:\left({q}_{p3}\right)\), and fifth (\(\:{q}_{p5}\)) stages for boreholes Y1 and Y2, including the absolute difference in permeability between the first and fifth stages ((\(\:\left|{q}_{p1}-{q}_{p5}\right|\)).

Following the normality test and variance homogeneity test, the water permeability data of each rock layer did not conform to a normal distribution (P < 0.05), and the overall variance was found to be unequal (P < 0.01). Consequently, the Mann-Whitney U test was employed32,33, with P < 0.05 indicating a statistically significant difference. The detailed results are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

Longitudinal analysis

The vertical analysis of each borehole indicates that there is no statistically significant difference in permeability among formations unaffected by mining (Y1 borehole) (Z = −0.1020, P = 0.9189), between \(\:{q}_{p3}-{q}_{p1}\) and \(\:{q}_{p3}-{q}_{p5}\) (Z = −0.1380, P = 0.8899), and no significant difference exists for \(\:{q}_{p3}-{q}_{p5}\). This suggests that the rock strata are largely unaffected by high-pressure water and exhibit low sensitivity to such conditions. In contrast, the permeability of strata affected by mining (Y2 borehole) shows a statistically significant difference (Z = −2.7850, P = 0.0053), with a marked difference observed in the comparison of \(\:{q}_{p3}-{q}_{p1}\) versus \(\:{q}_{p3}-{q}_{p5}\) (Z = 3.6360, P = 0.0003). These findings indicate that the strata are significantly influenced by high-pressure water. Notably, bauxite rock and Ordovician limestone demonstrate pronounced susceptibility to high-pressure water.

Horizontal analysis

In the initial stage, statistical differences in permeability (\(\:{q}_{p1}\)) were observed for fine sandstone (Z = 2.6810, P = 0.0073), bauxite rock (Z = −1.9680, P = 0.0491), and Ordovician limestone (Z = −1.9840, P = 0.0472). This suggests that these rock strata are substantially influenced by mining activities. In the third stage, a statistically significant difference in permeability (\(\:{q}_{p3}\)) was noted between fine sandstone (Z = 2.1910, P = 0.0285) and Ordovician limestone (Z = −2.3090, P = 0.0209), further indicating a marked impact of mining on the rock strata. By the fifth stage, permeability (\(\:{q}_{p5}\)) was significantly affected by mining (Z = −2.5860, P = 0.0097), with both bauxite rock (Z = −2.4600, P = 0.0139) and Ordovician limestone (Z = −2.4600, P = 0.0139) showing substantial changes due to mining. The recoverability of permeability (\(\:\left|{q}_{p1}-{q}_{p5}\right|\)) following high-pressure water injection induced by mining is limited (Z = −2.4430, P = 0.0146). Notably, the permeability recovery capacity of bauxite rock (Z = −2.3090, P = 0.0139) and Ordovician limestone (Z = −2.4600, P = 0.0139) decreased considerably.

To summarize, this study concludes that mining activities exert a substantial influence on the permeability of coal seam floor strata, notably altering the permeability of fine sandstone, bauxite, and Ordovician limestone. This effect is particularly pronounced during the third and fifth stages, leading to diminished recovery of rock permeability and inadequate restoration of permeability. It is recommended to implement targeted measures to mitigate the risk of water inrush.

Fault analysis

In boreholes Y1 and Y2, a total of 42 hydraulic testing intervals were designated across seven rock formations. During the testing process, due to severe degradation of carbonaceous mudstone in borehole Y2, two intervals were compromised during packer installation, rendering hydraulic testing unfeasible for these sections. The remaining 40 intervals successfully underwent hydraulic testing. Of these, 19 intervals failed to achieve the target pressure of 14 MPa during the third stage, while two intervals achieved the target pressure only in the first stage. Consequently, the proportion of test intervals that did not reach the preset pressure was 47.5%.

The primary reason for failure to attain the target pressure lies in the underestimation of permeability in certain rock formations under high water pressure conditions—an inherent limitation arising from the interaction between formation response and equipment capacity. Prior fracturing tests conducted in the Ordovician limestone layer in borehole Y1 confirmed the feasibility of using 14 MPa as the maximum test pressure. However, during actual testing, the permeability of certain formations significantly increased under elevated pressure, causing the flow rate to reach the operational limit of the fracturing pump (rated maximum flow rate: 60 L/min) before the pressure could rise to 14 MPa, thereby preventing further pressure escalation. Additionally, factors such as mining-induced disturbances and regional heterogeneity within the same lithological unit may contribute to the inability to achieve target pressures. For example, bauxitic mudstone in borehole Y2 was heavily affected by mining activities, with test pressures failing to reach even the second-stage target of 9 MPa. Four hydraulic tests were conducted in the Ordovician limestone in both boreholes Y1 and Y2. All four tests in borehole Y1 met the required criteria, whereas the third-stage pressure in borehole Y2 failed to meet the standard, likely due to the influence of mining activities or spatial variability within the formation.

Discussion

The influence of coal seam mining on the permeability of floor strata

As a significant geological disturbance, coal mining engineering will have a complex and far-reaching impact on the permeability of floor strata. In this study, the changes of permeability types, permeability and permeability recovery ability of floor strata caused by coal seam mining are revealed through the graded high-pressure water pressure test of double plug sealing test section, and the differences of response of different strata to mining are discussed (Table 4).

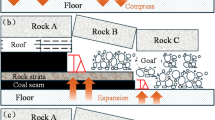

(1) Coal seam mining can change the permeability type of floor strata (P-Q curve).

The test results show that the permeability types of strata in the areas not affected by mining are mainly erosive (47.62%) and laminar (28.57%), while those in the areas affected by mining are mainly erosive (63.16%), and the degree of erosion is obviously improved. The change of permeability type of rock stratum shows that before coal mining, the rock stratum is complete and the fracture filler is stable, and the mining action induces the fracture expansion of rock stratum and increases the erodibility of fracture filler, thus changing the seepage mechanism of rock stratum.

In general, the erosion characteristics of bauxite mudstone, bauxite and Ordovician limestone are obviously enhanced after mining. The permeability type of bauxite mudstone changed from the original laminar flow type to the erosion type after mining. This may be due to the plastic deformation of mudstone rocks and the increase of seepage cracks under the action of mining stress, thus changing their permeability characteristics34. Except that the first test section of borehole Y1 is laminar flow type, the other test sections are erosion type. It is worth noting that the flow difference of each test section of borehole Y1 (ΔQ = Q5-Q1) is significantly lower than that of borehole Y2. The flow difference ranges of each test section of borehole Y1 and Y2 are − 0.48 ~ 0.20 and 8.78 ~ 12.70 L/min, respectively. It can be seen that the erosion characteristics are significantly enhanced after mining. All test sections of Ordovician limestone show erosion type. The first and fifth stage flows of Y1 borehole are 0, and the flow difference of each test section of Y2 borehole is significantly increased (the flow difference is 11.85 ~ 25.00 L/min), which further confirms the change of rock permeability type caused by mining. These phenomena are consistent with the conclusion in previous studies that mining stress leads to the expansion of rock fractures and the enhancement of connectivity35.

(2) Coal mining can change the water permeability of coal floor strata.

The test results show that the water permeability of coal seam floor strata is improved by mining action as a whole. Mann-Whitney U test was used to test the difference, and the significant influence of mining action on rock permeability was verified statistically. The permeability of Y1 borehole (\(\:{q}_{p5}\)) is 0 ~ 2.21Lu (X̅=1.03Lu), and that of Y2 borehole (\(\:{q}_{p5}\)) is 0 ~ 19.64Lu (X̅=5.39Lu), which improves the permeability. It is proved by statistical test that there is a significant difference (Z=−2.5860, P = 0.0097) in the water permeability (\(\:{q}_{p5}\)) between the two groups on the whole, which proves the significant influence of mining action on the water permeability of rock stratum. The transformation of rock permeability shows that the loading and unloading action of mining on floor rock leads to rock damage and crack expansion, which improves rock permeability, while the advance support pressure can lead to the closure of rock cracks and reduce rock permeability.

The permeability of bauxite mudstone, bauxite rock and Ordovician limestone changed significantly after mining. The permeability (\(\:{q}_{p5}\)) of borehole Y1 in bauxite mudstone is 1.84 and 2.21Lu, respectively, and that of borehole Y2 is 19.64 and 17.25Lu, respectively, and the permeability of rock stratum has changed from weak permeability to medium permeability. This is consistent with the view in rock mechanics that low-strength rocks are more prone to failure under stress disturbance16. The water permeability of Y1 and Y2 drilling sections of fine sandstone ranges from 0.93 to 1.99 Lu (X̅=1.50 Lu) and 0.00 to 3.04 Lu (X̅=0.92 Lu), respectively. The water permeability of some strata is enhanced, but the overall water permeability is reduced. The water permeability of borehole Y1 and Y2 of bauxite rock ranges from 0.00 to 1.52 Lu (X̅=0.62 Lu) and 4.44 to 6.83 Lu (X̅=5.41 Lu), respectively, and the water permeability of rock stratum changes from extremely micro-micro water permeability to weak water permeability. The permeability of borehole Y1 of Ordovician limestone is 0, and that of borehole Y2 is 5.85 ~ 11.44 Lu, and the permeability of rock stratum is changed from minimal permeability to weak permeability.

(3) The deterioration effect of coal seam mining on the recovery ability of rock permeability.

The test results show that the recovery ability of water permeability of coal seam floor strata is weakened by mining action as a whole. The permeability recovery coefficient k of the test sections was calculated using Eq. (2) to evaluate the degradation effect of coal seam mining on the permeability recovery capacity of surrounding rock strata. This assessment was conducted by comparing the extent of decline in permeability recovery before and after mining. For borehole Y1, the permeability recovery coefficient k ranged from 85.79% to 113.45%, with a mean value of 99.55%. The maximum recorded value of 594.74% from the 11th test section—located in the Benxi Limestone—was excluded as an outlier. This data point corresponds to a P-Q curve of the filling type, where the permeability at stage P₅ was significantly lower than at stage P₁, resulting in an anomalously high k value. In borehole Y2, the k values varied between 4.37% and 118.64%, with an average of 58.36%. The minimum value of − 17.83% from the second test section, situated within bauxite mudstone, was also excluded. Although the stable flow rate at stage P₅ was lower than at stage P₃, the calculated permeability at P₅ exceeded that at P₃ due to an inaccurately recorded quasi-stable seepage state during P₃, leading to an underestimated permeability and a negative k value. The degree of deterioration in permeability recovery capacity induced by mining activities is quantified by the decline multiple, defined as the ratio of the k value in borehole Y1 (pre-mining reference) to that in borehole Y2 (post-mining condition). Overall, the average permeability recovery capacity of the overlying strata decreased by a factor of 1.71 (calculated as 99.55%/58.36%). Individual rock layers exhibited decline multiples ranging from 1.05 to 8.52. Specifically, for bauxite mudstone, the initial calculated decline multiple was − 29.59; however, upon removal of the anomalous − 17.83% value from Y2, the corrected decline multiple was determined to be 8.52. Similarly, for the Benxi Limestone, the decline multiple was adjusted to 1.27 after excluding the outlier value of 594.74% from Y1. These results, derived from systematic analysis of the permeability recovery coefficient and corresponding decline multiples, demonstrate a significant reduction in the permeability performance of floor strata following mining activities.

The nonparametric statistical method is used to test the difference, and the significant influence of mining action on the recovery ability of rock permeability is verified from the statistical point of view. The difference of water permeability (\(\:\left|{q}_{p1}-{q}_{p1}\right|\)) between Y1 and Y2 boreholes is 0.00 ~ 5.64Lu (X̅=0.67 Lu) and 0.00 ~ 17.25Lu (X̅=4.42 Lu), respectively, and the recovery ability of rock permeability is significantly reduced. Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze the difference of permeability recovery index (\(\:\left|{q}_{p1}-{q}_{p1}\right|\)), and there was a significant difference between the two groups of drilling data (Z=−2.4430, P = 0.0146), which confirmed the deterioration effect of mining action on the permeability recovery ability of rock strata.

Analysis indicates that high-pressure water injection diminishes the fracture closure capacity of the rock mass, resulting in permanent alterations to the fracture network. This is consistent with the conclusion about the irreversibility of mining damage in some studies36.

(4) The response of rock permeability to mining is different.

The test results show that different strata and intervals have different effects on the permeability type, permeability and permeability recovery ability of mining disturbance. Mining action intensifies the hydraulic erosion effect of floor strata and enhances the water permeability of strata, but some strata and intervals show abnormal phenomena of filling and decreasing water permeability. This difference may be related to the mineral composition, structural characteristics and stress state of rocks37.

The permeability of Y1 and Y2 boreholes in fine sandstone is 0.93 ~ 1.99 Lu (X̅=1.50Lu, CV (coefficient of variation) = 0.2781) and 0.00 ~ 3.04 Lu (X̅=0.92 Lu, CV = 1.5083), respectively. The permeability characteristics of rock stratum change from homogeneous weak permeability to differential permeability, and the permeability of upper rock stratum in Y2 borehole is obviously reduced, while that of lower rock stratum is improved. This difference may be related to the heterogeneity of fine sandstone, and the development degree and filling condition of fractures in different intervals are different, which leads to the different response to mining. No.10 coal was affected by mining, and the P-Q curve changed from laminar flow type to filling type, and the water permeability at all stages decreased, which may be due to the compaction of coal seam by advanced supporting stress, which led to the closure of cracks.

Comparative analysis

Comparative analysis of method innovation

This paper proposes an improved water injection test method, which can efficiently and rapidly obtain the in-situ permeability of the formation. Compared with the traditional water pressure test, this method has the following advantages:

In the in-situ evaluation of permeability characteristics of rock strata beneath the coal seam floor, the improved water pressure testing method demonstrates significant advantages over the conventional approach in terms of drilling workload, borehole utilization efficiency, testing efficiency, and data acquisition capacity (Table 5). When applying the traditional water pressure test to assess floor strata in areas unaffected by mining activities, detailed stratigraphic investigations are often limited due to economic constraints. In the conventional method, the floor strata are divided into three distinct testing intervals, each comprising one to three layers with differing lithologies. Each interval requires a separate borehole (Fig. 9). The first interval consists of carbonaceous mudstone, bauxitic mudstone, and fine sandstone, with a total borehole depth of 37.71 m, casing length of 3.51 m, and test section length of 34.20 m, yielding a borehole utilization rate (defined as the ratio of test section length to total borehole length) of 90.69%. The second interval includes Benxi limestone, Coal Seam No. 10, and bauxite, with a borehole depth of 78.62 m, casing length of 37.71 m, test section length of 40.91 m, and a utilization rate of 52.04%. The third interval comprises Ordovician limestone, with a borehole depth of 99.09 m, casing length of 78.62 m, test section length of 20.47 m, resulting in a utilization rate of 20.66%.

Furthermore, in the conventional water pressure test, assessing the permeability behavior of a test section following high-pressure water injection typically requires a waiting period exceeding 24 h to achieve stable conditions. In contrast, the improved method enables parameter determination during the depressurization phase of continuous water injection, eliminating the need for prolonged waiting times. The improved test employs a cyclic injection process involving an initial pressurization stage followed by a controlled pressure reduction phase, differing fundamentally from the constant pressurized injection used in traditional tests. This approach allows for the derivation of the P-Q curve (pressure-flow relationship), which provides insights into fracture sealing capacity and yields a comprehensive assessment of the rock mass’s permeability characteristics.

Engineering verification

In order to study the influence of coal seam mining on the permeability of floor strata, taking the mining under pressure of No.9 coal seam in Xipangjing, Dongpang Mine as the engineering background, one drilling hole was constructed in the area not affected by mining and one drilling hole was constructed in the area affected by mining, and 42 times of water pressure tests were carried out on 7 strata of No.9 coal seam floor by using the hierarchical high-pressure circulating water pressure test method with double plug sealing test section, which verified the effectiveness of the proposed test method. In addition to obtaining the conventional parameter water permeability, the P-Q curve of hydropower engineering was introduced into the research on the permeability of coal seam floor in mining engineering.

Limitations

Although the improved water pressure test method has obvious advantages in permeability test, its application still has the following limitations.

(1) High water pressure setting. The determination of water injection pressure should take into account multiple factors, including the permeability of individual test sections, the capacity of water injection equipment, and the in-situ stress conditions within the test area. In this study, the maximum water pressure was established without fully considering the variations in permeability across different rock strata. As a result, 47.5% of the test sections exceeded the operational limits of the pressure pump (60 L/min) and failed to achieve the target maximum pressure of 14 MPa, thereby compromising the accuracy and comparability of the test results.

(2) Interpretation of results. At present, the interpretation of P-Q curve depends on the existing five types of permeability, and the interpretation of laminar, spreading and erosive strata is relatively unified, but the interpretation of turbulent, filling and P-Q curve types other than the five types of permeability is inconsistent, lacking reliable theoretical standards, and the interpretation of complex fracture network is poor.

(3) Equipment requirements and costs. High water pressure water pressure test requires not only that the pressure pump can provide high water pressure, but also that the pressure gauge, flow meter, plug, valve and connecting pipeline can withstand high water pressure. In addition, when the plug is used to seal the broken rock stratum, the sealing failure is easy to occur and it is easy to be damaged.

Engineering significance

In the permeability test of floor, the improved water pressure test can not only obtain the conventional permeability and permeability coefficient, but also obtain the P-Q curve of rock strata, which can reflect the ability of floor strata to block confined water and can be used as an index to evaluate the risk of floor water inrush. The research results show that mining can significantly change the permeability of coal seam floor strata. For bauxite and Ordovician limestone, mining not only improves the permeability of strata, but also reduces its permeability recovery ability, which greatly increases the risk of water inrush. Therefore, in the process of coal seam mining under pressure, the dynamic monitoring of permeability of coal seam floor strata can be strengthened, and the risk of water inrush from floor can be evaluated and warned. In addition, the improved water pressure test method and the analysis index of permeability type and permeability recovery ability are of guiding significance to grouting effect evaluation, dam geological evaluation, coalbed methane development and other projects38,39,40.

Future work

In light of the limitations associated with the improved water pressure testing method in evaluating the permeability characteristics of floor rock strata, future research will be systematically conducted across three integrated dimensions: the integration of multiple testing techniques, in-depth analysis of internal mechanisms, and the development of numerical models, thereby establishing a closed-loop research framework encompassing “testing–theory–application.” The specific research directions are as follows:

(1) A multi-modal and multi-scale collaborative testing approach will be adopted to overcome the bias inherent in single testing methods, enabling a comprehensive assessment of rock mass permeability. Water injection tests will be integrated with microseismic monitoring and porous seepage field measurements to capture the initiation and propagation of micro-fractures and associated seepage field dynamics during fluid injection. Furthermore, laboratory-based analyses—including rock mechanical testing, X-ray diffraction, mercury intrusion porosimetry, and CT scanning—will be employed to establish a multi-scale permeability relationship linking mechanical properties, mineral composition, pore structure, microstructural features, and macroscopic behavior.

(2) Internal mechanism analysis will focus on quantifying the correlation between fracture initiation and propagation and permeability evolution under varying stress paths. Building upon the multi-scale permeability relationships derived from integrated testing, the theory of damage mechanics will be incorporated to develop a permeability evolution model that accounts for fracture growth and rock mass degradation. This model will facilitate the investigation of cross-scale permeability responses across micro- and macro-fracture networks, providing a theoretical basis for understanding the attenuation and recovery mechanisms of rock mass permeability in response to mining-induced disturbances.

(3) A numerical model incorporating heterogeneous fracture networks will be developed to enable permeability prediction and engineering risk assessment. By integrating field and laboratory test data with advanced numerical simulation techniques, inverse modeling of in-situ water pressure tests will be performed to construct a heterogeneous seepage model. This model will elucidate the nonlinear relationships between formation physical parameters and permeability behavior. When applied under realistic mining conditions, it will support predictive evaluation of floor permeability performance and quantitative risk assessment of water inrush hazards during coal seam extraction.

Conclusion

Based on water pressure testing technologies applied in water conservancy and hydropower engineering as well as mining engineering, this study proposes an improved water pressure testing method tailored for thick floor conditions in deep coal seams. The proposed method was implemented in field tests conducted on the floor of the No. 9 coal seam at Xipangjing, Dongpang Mine. Through comprehensive analysis and discussion, the following conclusions are drawn:

-

1.

The improved water pressure testing method enables the determination of seepage parameters across any test section of a borehole through a three-pressure-level, five-stage pressurization and depressurization water injection process. Compared to conventional water pressure testing methods, this approach offers significant advantages in terms of reduced borehole engineering volume, enhanced borehole utilization efficiency, shortened testing duration, and increased data acquisition capacity.

-

2.

Coal seam mining alters the seepage behavior and permeability characteristics of underlying strata. In the virgin stress zone (Y1 borehole test area), P-Q curves predominantly exhibited laminar flow (28.57%) and erosion-type responses (47.62%). In contrast, within the mining-affected zone (Y2 borehole test area), erosion-type responses became dominant (63.16%), with turbulent flow characteristics emerging in certain test sections. This indicates that mining activities have significantly modified the hydraulic properties of the rock mass. At stage P₅, the permeability of the Y1 borehole ranged from 0 to 2.21 Lu (X̅ = 1.03 Lu), whereas the Y2 borehole showed a wider range of 0–19.64 Lu (X̅ = 5.39 Lu). Mann-Whitney U test results confirmed a statistically significant difference between the two datasets (Z = −2.586, p = 0.0097). These findings demonstrate that coal seam mining significantly increases the permeability of the floor strata, with the observed difference being statistically significant.

-

3.

Mining activities diminish the permeability recovery capacity of rock strata. The permeability recovery coefficient (k) in borehole Y1 varied between 85.79% and 113.45% (X̅ = 99.55%), while in borehole Y2 it ranged from 4.37% to 118.64% (X̅ = 58.36%), indicating a 1.71-fold reduction in average recovery capacity due to mining influence. Furthermore, the permeability difference (\(\:{q}_{p5}\_{q}_{p1}\)) was − 5.64 to 1.43 Lu (X̅ = −0.19 Lu) for Y1, compared to −0.11 to 17.25 Lu (X̅ = 4.40 Lu) for Y2. The Mann-Whitney U test revealed a statistically significant difference between the two groups (Z = −2.443, P = 0.0146). These results indicate that coal seam mining significantly impairs the permeability recovery capacity of the floor strata, and this effect is statistically significant.

-

4.

Different lithological layers exhibit heterogeneous responses to mining-induced disturbances. In terms of seepage patterns, there is a notable shift from laminar flow and erosion toward predominant erosion behavior, with increased erosion intensity. However, some test sections in the Y2 borehole display filling-type responses; for example, the No. 10 coal seam transitioned from laminar to filling-type flow. Regarding permeability, mining has generally increased the permeability of the floor strata, but the degree of response varies among lithologies. For instance, the average permeability of bauxitic mudstone at stage P₅ increased from 2.03 Lu to 18.45 Lu, whereas that of fine sandstone decreased from 2.03 Lu to 0.92 Lu. With respect to permeability recovery capacity, although mining overall reduces this capacity, the extent of reduction differs across rock types. Specifically, the reduction factors for bauxitic mudstone and fine sandstone were 8.50 and 1.20.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

International energy agency. Global Energy Review [R].(2025). (2025).

National bureau of statistics. Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China 2024[R]. (2025).

Yuan, L. et al. Scientific problems and key technologies for safe and efficient mining of deep coal resources[J]. J. China Coal Soc. 50 (1), 1–12 (2025).

Liu, H. et al. Rule study on the risk of floor water inrush based on the plate model theory [J]. Sustainability 15 (10), 7844 (2023).

Zeng, Y. F. et al. Disaster-causing mechanism and prevention and control vision orientation of different types of coal seam floor water disasters in china[J]. J. China Coal Soc. 50 (2), 1073–1099 (2025).

Gai, Q. et al. A New Method for Evaluating Floor Spatial Failure Characteristics and Water Inrush Risk Based on Microseismic monitoring[J] 57, 2847–2875 (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2024). 4.

Zhou, S. et al. A New Type of Ordovician Limestone Karst Water Inrush from the Floor of Old Goaf: Formation Mechanism and the Prevention and Control technology[J] 51, 103–112 (Coal Geology & Exploration, 2023). 7.

Zuo, J. et al. Rock Strata Failure Behavior of Deep Ordovician Limestone Aquifer and multi-level Control Technology of Water Inrush Based on Microseismic Monitoring and Numerical methods[J] 55, 4591–4614 (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2022). 8.

Yin, H. et al. Prevention of water inrushes in deep coal mining over the ordovician aquifer: A case study in the wutongzhuang coal mine of China[J]. Geofluids, 2021: 1–13. (2021).

Yang, T-H. et al. State of the Art and trends of water-inrush mechanism of nonlinear flow in fractured rock mass[J]. Meitan Xuebao/Journal China Coal Soc. 41 (Compendex), 1598–1609 (2016).

Sui, W. H. Catastrophic mechanism and its prevention and control of seepage deformation and failure of mining rock mass II: A review of water inrush from seam floor[J]. J. Eng. Geol. 30 (6), 1849–1866 (2022).

Miao, K. et al. Utilization of broken rock in shallow gobs for mitigating mining-induced water inrush disaster risks and environmental damage: experimental study and permeability model.[J]. Sci. Total Environ. 903, 166812 (2023).

Qu, X. et al. Gray evaluation of water inrush risk in deep mining floor.[J]. ACS Omega. 6 (22), 13970–13986 (2021).

Louis, C. & Maini, Y. Determination of in-situ hydraulic parameters in jointed rock[J/OL]. International Society of Rock Mechanics Proceedings, 1970[2025-05-17].

Atkinson, J. H. Fundamentals of rock mechanics[J]. Eng. Geol. 11, 241–241 (1977).

Hsieh, P. A. Fundamentals of rock mechanics[J]. Geofluids 9 (3), 251–252 (2009).

Yang, Z. B. & Dong, S. N. Study on quantitative evaluation of grouting effect by water pressure test[J]. J. China Coal Soc. 43 (7), 2021–2028 (2018).

Fu, J. J. et al. Research on the water blocking capacity of bottom mudstone based on pressure water test [J]. Metal Mine, (6): 160–163. (2014).

Sun, X. Q. et al. Study on permeability barrier performance of deep coal seam floor based on Packer permeability test[J]. China Coal. 40 (11), 93–97 (2014).

Huang, Z. et al. Study of impermeability of rock stratum based on water injectiion test[J]. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 33 (S2), 3573–3580 (2014).

Huang, Z. et al. Characterizing the hydraulic conductivity of rock formations between deep coal and aquifers using injection tests[J]. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 71, 12–18 (2014).

Zhu, Y. W. S. & Zhang, T. Permeability of the coal seam floor rock mass in a deep mine based on in-situ water injection tests[J]. Mine Water Environ. 37 (4), 724–733 (2018).

Huang, Z., Zeng, W. & Zhao, K. Experimental investigation of the variations in hydraulic properties of a fault zone in Western shandong, China[J]. J. Hydrol. 574, 822–835 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Water-inrush risk through fault zones with multiple karst aquifers underlying the coal floor: A case study in the Liuzhuang coal mine, Southern China[J]. Mine Water Environ. 40 (4), 1037–1047 (2021).

Army corps of engineers U.S. Rock Testing Handbook (Test Standards 1993)[Z]([日期不详]).

佚名. Geotechnical investigation and testing - geohydraulic testing - part 3: water pressure tests in rock (ISO 22282-3:2012)[Z/OL](2014-07-29)[2025-05-17]. Geotechnical investigation and testing - Geohydraulic testing - Part 3.

Liu, M. M. et al. An analytical model for nonlinear flow parameters of fractured rock masses based on high pressure Packer tests[J]. J. Hydraul. Eng. 47 (6), 752–762 (2016).

Wu, Y. T. et al. Grouting effect evaluation of dam foundation rock mass based on fracture filling characteristics[J]. Rock. Soil. Mech. 38 (S2), 311–316 (2017).

Foyo, A., Sánchez, M. A. & Tomillo, C. A proposal for a secondary permeability index obtained from water pressure tests in dam foundations[J]. Eng. Geol. 77 (1–2), 69–82 (2005).

Zlotnik, V. A. & Mcguire, V. L. Multi-level slug tests in highly permeable formations: 1. Modification of the springer-gelhar (SG) model[J]. J. Hydrol. 204 (1), 271–282 (1998).

Pickens, J. F. et al. Analysis and interpretation of borehole hydraulic tests in deep boreholes: Principles, model development, and applications[J]. Water Resour. Res. 23 (7), 1341–1375 (1987).

Sundjaja, J. H., Shrestha, R. & Krishan, K. McNemar and mann-whitney U tests[M/OL]//StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025[2025-05-17].

Dexter, F. Wilcoxon-mann-whitney test used for data that are not normally distributed.[J]. Anesth. Analgesia, 117(3): 537–538. (2013).

Pang, M. et al. Re-crushing process and non-darcian seepage characteristics of broken coal medium in coal mine water inrush[J]. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 11380 (2021).

Lei, G., Wu, D. & Zhu, S. Spatio-temporal evolution of acoustic emission events and initiation of stress fields in the fracturing of rock mass around a roadway under Cyclic high-stress loading[J]. PloS One. 18 (9), e0286005 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Experimental study on the porosity and permeability change of high-rank coal under Cyclic loading and unloading[J]. ACS Omega. 7 (34), 30197–30207 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Prevention and control of coal and gas outburst by directional hydraulic fracturing through seams and its application[J]. ACS Omega. 8 (41), 38359–38372 (2023).

Zhengzheng, C. et al. Migration mechanism of grouting slurry and permeability reduction in mining fractured rock mass[J]. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 3446 (2024).

Fekadu, A. et al. Engineering geological evaluation of Bowa dayole dam site, North Shewa zone, oromia, ethiopia[J]. Heliyon 11 (1), e41385 (2025).

Zhu, Q. et al. Investigation into the variation characteristics and influencing factors of coalbed methane gas content in deep coal seams[J]. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 18813 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the National Key R&D program of China (No. 2024YFC3013802), the Hebei Province Youth Science Foundation Project (D2025508011) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 3142025007) are gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

Funding: The National Key R&D program of China (No. 2024YFC3013802); Hebei Province Youth Science Foundation Project (D2025508011); The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 3142025007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. M. and M. C. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures and tables. S. Y. and E. H. contributed to the development of writing concepts and experimental methodologies. H. Y. was in charge of summarizing the key conclusions of the manuscript. All authors participated in reviewing and approving the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meng, H., Yin, S., Hou, E. et al. Investigation of change coal seam floor permeability based on pressurized water testing. Sci Rep 15, 44970 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29006-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29006-1