Abstract

Much existing laboratory research has shown that both novelty and prior knowledge benefit episodic memory, however they do so through differing mechanisms. Critically, autobiographical experiences are rarely completely novel or congruent with prior experience, existing within a spectrum from ‘absolute’ novelty to ‘absolute’ congruency. A prospective real-world autobiographical event sampling study was conducted to investigate memory outcomes for events that varied along this spectrum. We found that events that participants labeled as ‘new’ were later recalled with greater vividness compared to events labeled ‘periodic’ and ‘routine’. Crucially, however, within the ‘new’ events, those that were more semantically similar (to all other events reported within participant during the 14-day diary period) were recalled with the greatest vividness and were associated with higher happiness and excitement ratings. We also found that relative emotional distinctiveness across all other events predicted greater vividness and recalled episodic detail. Our results suggest that a combination of novelty and relative semantic similarity, rather than ‘maximal’ novelty, may be more impactful for well-being and vivid recall, which we are calling the ‘something old, something new’ principle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

What we remember can shape who we are, who we become, and how we measure the life already lived. For this reason, understanding which experiences become memorable holds considerable weight. Prior, majorly lab-based work has demonstrated that unique experiences tend to be more accessible in memory1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. However, day-to-day life outside of the laboratory is complex. The novelty of a personal experience can stem from various sources, including both external (e.g., people, places, activities, etc.) as well as internal (e.g., emotion) sources and exist along a continuous scale of magnitude10. Further, congruency with prior knowledge, which is traditionally placed in opposition to novelty, has also been shown to benefit memory11,12,13,14,15,16. In order to better understand these interactions, it is important to tease apart how different types and degrees of novelty impact memory for autobiographical experiences.

Novel events are typically distinct, effectively ‘standing out’ in an overarching context. The ‘isolation effect’ demonstrates that such relative distinctiveness is more likely to be later recalled1. Novel events attract additional attention, increasing the likelihood of effective encoding and later memory for that information4,7. Novelty can also elevate arousal, triggering the release of neuromodulators such as dopamine and norepinephrine, which facilitate long-term potentiation, a key mechanism underlying long-term memory formation3,5,6,7,8,9. By contrast, information that conforms to our expectations can also endure in long-term memory. Animal work found that new paired associates were learned more rapidly when there was a pre-existing schema12. A wealth of behavioral data in humans has shown that encoding new information related to existing knowledge leads to rapid integration of such information into the current schema, thus making it more resistant to forgetting11,13,14,15,16. To accommodate for these disparate observations, a ‘U-shaped’ function of congruency has been proposed and further experiments were conducted to show that information that was surprising and information that conformed to expectations both had higher recognition and recall rates compared to unrelated information17,18.

With this foundational work in mind, a subsequent question is how this U-shaped congruency effect translates to memory for complex, personal events. Recent work on real-world autobiographical memory has shown that a metric of daily ‘uniqueness’, composed of different measures collected during each day as well as during the recall test, is associated with greater recalled episodic details for older adults19. In the current study, we conducted a prospective real-world autobiographical ‘daily diary’ study, where at the end of our two-week sampling period (and after an additional two-week delay) young adults were administered an autobiographical memory recall test. Based on these daily participant reports, we found a significant effect of event novelty on memory vividness20. Events labeled as ‘new’ during the sampling period were later remembered with greater vividness after a two-week delay compared to events labeled as ‘periodic’ and ‘routine’. Further, ‘routine’ events were remembered with the least episodic detail at recall. Thus, it is clear that there is a positive effect of novelty on the richness of autobiographical memory recall. However, most real-world events are neither purely novel nor purely congruent. For example, grocery shopping in a new country (i.e., a familiar event in a new context) or encountering a celebrity during a routine commute (i.e., a novel event in a familiar context) each involve schema-congruent and novel components. These ‘intermediate’ experiences (i.e., events that include both novel and schema-congruent elements) do not fit neatly at either end of the U-shaped congruency curve. Recent work10 proposes a gradient theory of schema and novelty, and suggests that the fate of a memory is influenced by the interplay between novel and congruent elements within that complex experience. There is much to be investigated regarding how the interplay between novelty and congruency, as well as the specific type or types of novelty present, impact autobiographical memory richness. Little is known about whether different types of novelty have differing impacts on later memory.

To address these open questions, we leveraged our event-dense sampling daily diary study in young adults20 to investigate the impact of novelty, congruency, and their interactions on later episodic recall of the reported autobiographical events. Importantly, we investigated whether different sources of novelty (based on event regularity, semantic content, and emotional content) produced differing effects on our episodic memory outcomes. Not only is it important to understand how varying degrees and types of novelty impact memory for personal experiences, but also how novelty impacts the emotions felt during such experiences. For example, previous studies found that greater spatial exploration21,22 and greater event-level composite uniqueness19 were associated with greater positive affect for that day. Thus, we additionally tested if novel events elicited more positive emotions using our participants’ event-level emotion ratings.

Methods

Participants

A total of 51 participants (ages 18–35) were recruited and enrolled in this study from the Columbia University community. All participants lived in the United States and indicated that they were not currently diagnosed with any neurological or psychiatric disorder. Ten participants were withdrawn from this study because they missed two or more daily diary entries during the two-week daily survey. Thus, our final sample size is 41 participants (Mage = 25.6; SDage = 4.2). We did not exclude anyone from participating based on their reported sex and, likely related to the distribution of female to male students across Columbia College and Barnard College (an all-girls school), our sample was predominantly female (82.9%). Participants were compensated $12/hour and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University and the study was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Procedure

Overview. Participants completed daily questionnaires via Qualtrics on their smartphones or computers spanning a 4-week period. The study consisted of four phases: the pre-survey questionnaire period, a two-week daily diary period, the post-study questionnaire period, and the long-term memory test (Fig. 1). The current study is focused on the daily diary collection and memory test phases. Thus, data from the pre- and post-study surveys are not reported here.

(a) Experimental Design. The two-week daily diary period was flanked by a pre-diary study questionnaire and a post-diary study questionnaire. Two weeks after the post-diary questionnaire, participants completed a memory test for the events that were reported during the daily diary period. (b) Overview of relevant variables collected with each daily diary report (see Methods for details). Importantly, participants reported three events each day and generated a unique title after each event description (the title and description pictured above do not represent a true example from the dataset to maintain participant privacy). (c) Illustration of the relevant memory test: event recall. Note that all events, whether they were part of the event recall test or the temporal memory test (see Methods for details), had corresponding subjective memory vividness ratings.

Daily diary period. During the daily diary period, participants completed an identical survey each day for two weeks (14 days). They were instructed to complete the survey at any point between receipt of the survey link (sent ~5 pm each day) and before they went to bed. The survey began with general questions regarding the participant’s thoughts, feelings, and actions during that day. Next, they were asked to report and describe three specific events that took place that day. The task instructions identified an event as being ‘a thing you have done (e.g., listening to music, working on a project, talking on the phone, etc.) either on your own or with others’. Participants typed detailed descriptions of each event and provided a brief, distinct title for each event. For each event they were also asked about its subjective duration, how long the event actually was (i.e., reported event duration), when during the day it took place, other people who were present (if applicable), how often the participant had experienced that type of event, how memorable and meaningful the event was, and what took place immediately before and after the event. Participants were also asked to rate the intensity of seven feelings (‘happy’, ‘positive’, ‘sad’, ‘negative’, ‘excited’, ‘calm’, and ‘afraid’) related to the experience of each event on a Likert scale23 of 1 to 5 (1 being ‘not at all’, and 5 being ‘a great deal’). In certain cases, participants missed one diary day (N = 11). One participant missed two diary days (the requirement that participants could not continue the study after missing two diary days had not yet been implemented). One participant reported only one event on a specific day, and one other participant reported only two events on a specific day (out of three). In one instance a participant completed one extra daily diary day (15 instead of 14 days). Therefore, a range of 36–45 events were reported across participants for a total of 1,673 events.

Long-term memory test. A memory test was administered approximately two weeks after the conclusion of the last daily diary entry (range: 14–19 days) and consisted of both event recall and temporal memory tests. Before the memory test, event titles and descriptions were inspected. Some participants used the exact same title for two of their reported events (N = 4), and thus the events with duplicate titles were removed (N = 10 events). Exceptionally vague descriptions during the diary period were also excluded from analyses (N = 14 events), an example being: “I checked my email”. Fourteen event descriptions were excluded from the memory test due to a coding error. These 38 events make up about 2.22% of the total events collected from the 41 participants that completed the study. Next, one third of the events reported during the daily diary period (M = 13.8 events), one per day, was randomly selected to be included in the event recall test. The remaining two-thirds (M = 13.2 pairs) were included to create event pairs for the temporal memory test. For the event recall test, which took place first, participants were shown their own generated event titles to serve as memory cues. They were first asked to rate subjective vividness with which they could recall the corresponding event, and then to freely recall (via typing) the event in as much detail as possible. A recall description was required for each event included in the event recall test. Memory for other event details was then tested via separate, additional questions such as: the location and time of day, others who were present (if applicable), how long the event lasted, and what they were doing immediately before and after the event. For the temporal memory test, participants were presented with two of their self-generated event titles and were asked which event happened earlier in time, as well as how far apart in time the two events felt on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 being ‘very close’, and 5 being ‘very far’). Temporal memory performance was not analyzed in this study. Each event (N = 1,673) had a memory vividness rating regardless of whether it was part of the event recall or temporal memory test, but only one-third of the total events had a description at recall (N = 565). Therefore, it should be noted that analyses that include information about the event recall descriptions are based on that subset of events.

Measuring event novelty during the daily diary period

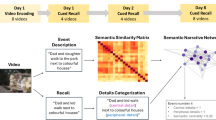

Event novelty was assessed using different measures. The first novelty-related variable of interest is event regularity. During the daily diary phase of the study, participants were asked to label each reported event as being ‘new’ (something they had never done before), ‘periodic’ (something they do occasionally), or ‘routine’ (something they do almost every day). This targets the participant’s own judgment regarding the novelty (or familiarity) of the reported event. For this reason, we also refer to this variable of event regularity as ‘participant-labeled novelty’. Event regularity was treated as a categorical variable in all analyses to avoid assuming linear relationships. Overall, participants reported 359 ‘new’ events (M = 8.76, SD = 5.48, range: 1–23), 1,050 ‘periodic’ events (M = 25.61, SD = 4.98, range: 16–35), and 264 ‘routine’ events (M = 6.44, SD = 5.44, range: 0–22). Second, we used a natural language processing (NLP) model to quantify the relative semantic similarity (RSS; M = 0.31, SD = 0.09) between all reported events within each participant. Specifically, we used a pre-trained Sentence Transformer (SBERT) model (‘all-mpnet-base-v2’) that analyzes paragraph-level documents24, in this case, diary entries reported during the two-week daily diary phase. This model outputs an embedding that can then be compared to the embeddings of other reported events. This embedding can be thought of as a coordinate (i.e., a vector) in a high-dimensional ‘map of meaning’, where each dimension captures a different linguistic or conceptual feature that the pre-trained model has learned (in the case of the ‘all-mpnet-base-v2’ model, there are 768 learned dimensions). Cosine similarity values, each value representing the angle distance between two vectors in this multidimensional semantic space, were extracted (see Fig. 2a). The pairwise cosine similarity values were then averaged across all events within each participant, creating an event-level variable that represents the RSS of an event relative to all other events reported by that participant, a higher RSS value suggesting greater semantic overlap.

Calculating relative semantic similarity and relative emotion similarity. (a) Illustration of how semantic embeddings were extracted and compared based on the reported daily diary events of one participant (‘Participant X’). (b) Illustration of how emotion vectors were extracted and compared based on the reported event-level emotion ratings of one participant (‘Participant X’).

We also developed a metric of event emotion distinctiveness as a potential source of novelty (Fig. 2b). As mentioned previously, participants were asked to rate the intensity of seven feelings (‘happy’, ‘positive’, ‘sad’, ‘negative’, ‘excited’, ‘calm’, and ‘afraid’) related to the experience of each event on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 being ‘not at all’, and 5 being ‘a great deal’). This series of ratings were treated as event-level emotion vectors. In order to capture the pattern and magnitude of differences between emotion vectors, Euclidean distances between an event’s emotion vector and every other event-level emotion vector from one participant was calculated. These pairwise distances were then averaged within participant, each averaged value representing the relative distinctiveness of the emotion ratings for that event compared to all other events reported by that participant. The inverse of this variable was then calculated to create a relative emotion similarity (RES) variable (M = 0.34, SD = 0.11), representing the relative similarity of an event’s emotion ratings relative to the emotion ratings of the remaining events reported by the participant. This was done so that both RSS and RES represent similarity (and novelty) with the same directionality. That is, both an increase in RSS and an increase in RES suggest greater relative event similarity, and less event novelty. Both RSS and RES were quantified using custom Python scripts, importing packages from the ‘sentence-transformers’24 and ‘scikit-learn’ libraries25.

Measuring memory vividness, detail, and stability for individual events

During the memory test, participants were presented with their self-generated event titles from the diary period and were first asked to rate the vividness of their memory (using a Likert scale23 from 1 to 5, 1 being ‘not at all’ and 5 being ‘highly vivid’). We measured memory for each event using two additional methods. First, we used a modified version of the Autobiographical Interview scoring approach26. Episodic detail counts consist of event (describing what happened, who was present, etc.), place (describing the event location), time (describing when the event took place or how long it lasted), thought/emotion (describing the feelings or thoughts of the self or others), and perceptual (describing sensory experience) details. In order to do this, we developed a novel method using large language models (LLMs). Specifically, we iteratively developed a GPT-4 prompt that outlined instructions to parse each event description into meaningful chunks, and then to subsequently categorize each chunk into episodic or non-episodic categories. For each description, we initiated a call to the OpenAI Chat Completions API27 with the model version “gpt-4–0613” and provided a naturalistic description of the task instructions (see Supplemental Material) followed by the description.

To validate this method of scoring, three independent human raters also segmented and categorized a subset of the event descriptions (N = 657 events; 30% of the full sample), following similar instructions that were inputted into GPT-4, guided by the autobiographical scoring methods mentioned previously26. We found a significant intraclass correlation when comparing episodic detail counts (based on the same subset of events) from human raters and GPT-4 (ICC = 0.663, p < 0.001), validating the assumption that GPT-4 would produce episodic detail counts that were comparable to manual, human-based scoring. To ensure rating consistency across events, the episodic detail counts that were included in our statistical analyses are based solely on GPT-4 ratings. Although episodic detail counts were extracted for both event descriptions during the daily diary period and subsequent event recalls during the memory test, only episodic detail counts at recall are included in these reported analyses. Figure 3 shows the distributions of the different types of episodic details that made up the recall descriptions: event: M = 3.47, SD = 2.16, range: 0–12; thought/emotion: M = 1.22, SD = 1.44, range: 0–12; time: M = 0.52, SD = 0.70, range: 0–3; perceptual: M = 0.37, SD = 0.73, range: 0–5; place: M = 0.34, SD = 0.58, range: 0–3. A total episodic detail count is used for analyses, but it should be noted that event details, followed by thought/emotion details, make the largest overall contributions to the total episodic recall detail counts.

Counts of recall details for different episodic detail types. Boxplots show the distribution of detail counts for each episodic detail category, with each box representing the interquartile range and the horizontal line indicating the median. Individual (jittered) data points are overlaid to display the full spread of the observations.

Finally, for the subset of events that had corresponding event recalls during the memory test phase (about one-third of events) the semantic similarity between the description reported at survey and the subsequent recall was analyzed using SBERT to create a memory stability variable, each value representing the cosine similarity of a description at survey compared to its corresponding recall.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using multilevel regression modeling with random intercepts and random slopes for each predictor (i.e., a full-random-effects structure). Each continuous predictor was centered within-participant, then scaled using Gelman scaling (M = 0, SD= 0.5 28). For models with an ordinal outcome variable (i.e., memory vividness and emotion ratings), frequentist cumulative link mixed models (CLMMs; a type of ordinal regression) with a full random effects structure and Gelman scaling were used. For each of these models, both the log-odds coefficient (β) and odds ratio (OR) are reported. For models predicting a continuous variable, a multilevel frequentist regression with a full random effects structure and Gelman scaling was tested first. The model failed to converge in the cases where either episodic detail at recall or memory stability was the outcome variable, which may be due to the reduced sample size. This motivated the use of Bayesian models (with non-informative priors) in these cases, keeping a full random effects structure and Gelman scaling. All R-hat values were less than 1.01 for all model parameters. The adapt_delta parameter was increased to resolve cases where the model produced divergent transitions. In one case, iterations were increased given the Effective Samples Size was too low. Effects from Bayesian models were considered meaningful when the credibility interval (CrI) did not include zero and the probability of direction (pd) exceeded 95%, meaning that more than 95% of posterior draws were in the same direction (i.e., positive or negative). In the cases where the probability of direction was greater than 95% and the credibility interval (CrI) included zero, the effects were considered marginal.

Analyses were conducted using custom analyses scripts in RStudio (ver 4.3.1). For data visualization, functions from the ggplot2 (ver 3.5.1) package29 were used. CLMMs were computed using the ordinal (ver 2023.12.4.1) package30. Frequentist regression models were computed using the lme4 (ver 1.1–35.1) and lmerTest (ver 3.1.3) packages31,32. The parameters (ver 0.22.2) package33 was used to calculate the confidence intervals from these models. The emmeans (ver 1.10.0) package34 was used when models included a three-level categorical predictor variable (i.e., event regularity), extracting estimated marginal means from each level, and then subsequently running pairwise contrasts between these estimates. The p-values from these estimated marginal means models were adjusted using Tukey’s method for comparing a family of estimates35. Bayesian models were run using the brms (ver 2.20.4) package36.

When analyzing the effects of event regularity, RSS, and RES on the memory measures, the predictors of interest were included together. Specifically, these multilevel models included the interaction between RSS and event regularity, and the additional predictor of RES. All novelty measures were included together in the same models predicting memory outcomes (i.e., memory vividness, episodic detail at recall, and memory stability) so that any significant effects of one type of novelty on memory were significant when also controlling for the other types of novelty. This robust model structure provides confidence that there is a unique contribution of that type of novelty on that memory outcome. Event regularity and RSS were included as an interaction while RES was an additional predictor given that event regularity and RSS represent familiarity (inversely, novelty) in content, while RES represents emotional familiarity (inversely, novelty). We expected that the two types of content-related novelty may diverge (e.g., an event may be labeled as ‘new’ but may also be highly semantically related to other events reported by that participant, such as going to a new restaurant while also reporting many food-related events). We expected that emotional novelty would have its own meaningful effect on memory that may co-occur with, but not depend on the novelty of the content. However, we did conduct subsequent analyses to test the effects of RES on our memory outcomes at each event regularity level.

We included survey day as a predictor to control for potential recency effects. When testing the relationship between RSS and word count, we found a significant but weak correlation (r = −0.080, p = 0.001). We next ran a one-way ANOVA to test word count across event regularity levels, and post-hoc pairwise comparisons using estimated marginal means with Tukey adjustment revealed significant differences (new–periodic: β = 18.6, SE = 3.16, CI = [11.0, 26.2], ptukey < 0.001; periodic–routine: β = 19.7, SE = 3.56, CI = [11.1, 28.2], ptukey < 0.001; new–routine: β = 38.3, SE = 4.19, CI = [28.2, 48.3], ptukey < 0.001). Therefore, the word counts of the event descriptions (provided during the diary period) were included in the models predicting memory outcomes to control for narrative length. We also included reported event duration (in minutes) to control for the length of the actual experienced event. As an example, to test recall vividness, the model structure was: recall vividness ~ event regularity*relative semantic similarity + relative emotion similarity + survey day + reported event duration + narrative length (1 + event regularity + relative semantic similarity + relative emotion similarity + survey day + reported event duration + narrative length | subject). Finally, outliers were not excluded in our models in order to capture natural variation in our sample.

Results

Participant-labeled novelty predicts greater episodic memory: vividness, recalled episodic detail, and stability

The main effects of event regularity (inversely, participant-labeled novelty) have been described in a separate manuscript20. These analyses showed that ‘memory vividness’ ratings during recall were significantly higher for ‘new’ compared to ‘periodic’ and ‘routine’ events. Further, ‘routine’ events were recalled with significantly less episodic detail compared to ‘new’ and ‘periodic’ events. These findings demonstrate the significant impact of novelty on autobiographical memory recall and inspired the focus of this current manuscript, which is to look for novelty effects across one’s own experiences with respect to semantic similarity (RSS) and emotional similarity (RES), while also including objective analyses of memory stability across time.

We first examined the relationship between event regularity and memory stability, memory stability being the semantic similarity between a participant’s description during the diary phase and the corresponding long-term memory recall (Fig. 4a). Posterior contrasts indicated that ‘new’ and ‘periodic’ events showed meaningfully greater memory stability compared to ‘routine’ events (new–routine: β = 0.08, CrI = [0.03, 0.13], pd = 99%; periodic–routine: β = 0.06, CrI = [0.004, 0.10], pd = 99%). There was no meaningful difference between ‘new’ and ‘periodic’ events (new–periodic: β = 0.02, CrI = [−0.007, 0.06], pd = 93%). A full-random-effects ordinal regression (CLMM) indicated significant effects of memory stability on memory vividness (Fig. 4b), with greater memory stability across time predicting significantly greater memory vividness during recall, both when collapsing across event regularity level (β = 1.29, SE = 0.18, CI = [0.93, 1.65], z = 6.97, p < 0.001, OR = 3.62), and when analyzing each event regularity level independently (new: β = 1.02, SE = 0.42, CI = [0.19, 1.85], z = 2.42, p = 0.015, OR = 2.78; periodic: β = 1.15, SE = 0.24, CI = [0.67, 1.63], z = 4.71, p < 0.001, OR = 3.17; and routine: β = 1.99, SE = 0.49, CI = [1.04, 2.95], z = 4.09, p < 0.001, OR = 7.33). Finally, greater memory stability predicted meaningfully more episodic details when averaging across event regularity level (β = 1.00, CrI = [0.54, 1.49], pd = 100%), and within each event regularity level (new: β = 1.09, CrI = [0.23, 1.98], pd = 99%; periodic: β = 1.02, CrI = [0.47, 1.53], pd = 99%; routine: β = 0.91, CrI = [0.06, 1.78], pd = 98%).

Effects of event regularity on memory stability and memory stability on memory vividness. (a) The half-violin plots represent the overall distributions of memory stability values (on a scale of 0–1) at each event regularity level. The boxplots within the half-violin plots span from the first to the third quartiles of the data, the horizontal lines representing the within-event regularity level median values. Probability of direction (pd) values are provided, values greater than 95% representing meaningful effects. (b) Relationships between memory stability (on a scale of 0–1) and memory vividness at each event regularity level. The lines and shaded bands represent linear regression lines and 95% confidence intervals. The line representing the effect of memory stability on memory vividness for routine events extends beyond the shaded region where predictions are extrapolated *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

In sum, the content of memory recall was a better match to the original event description during the daily diary phase when the event was ‘new’ or ‘periodic’, compared to a ‘routine’ event. Further, memory stability was associated with other aspects of the memory recall, greater memory stability predicting greater memory vividness ratings and more episodic details. The relationship between memory stability and memory vividness is particularly insightful, linking the participant-reported, subjective sense of memorability (i.e., vividness) to a more objective measure of memory reproducibility (i.e., memory stability).

Relative semantic distinctiveness modulates the effect of event regularity on memory vividness

We next asked if and how semantic similarity varied across reported events. Using a full-random-effects frequentist regression model, we found that ‘new’ events were significantly more semantically distinct compared to ‘periodic’ (new–periodic: β = −0.02, SE = 0.006, CI = [−0.03, −0.003], ptukey = 0.01) and ‘routine’ (new–routine: β = −0.03, SE = 0.007, CI = [−0.05, −0.02], ptukey < 0.001) events, with ‘periodic’ events being significantly more semantically distinct compared to ‘routine’ (periodic–routine: β = −0.01, SE = 0.006, CI = [−0.03, −0.0003], ptukey = 0.04) events (Fig. 5a). This measure validates the participant’s report of those events being ‘routine’ or ‘periodic’ because this RSS measure computes the semantic overlap across the dense sampling of experiences for each individual over a two-week period. However, although ‘new’ events were associated with the least amount of semantic overlap across experiences (had the lowest RSS overall), there were still ‘new’ events that had higher RSS compared to ‘routine’ events. Further, although ‘routine’ events had the highest RSS overall, there were ‘routine’ events that had lower RSS compared to ‘new’ events. Thus, in our next analyses we wanted to leverage this variability to examine the interaction between RSS and memory vividness across event regularity, while controlling for RES, survey day, reported event duration, and narrative length as additional predictors in the model.

Effects of event regularity on relative semantic similarity and relative semantic similarity on memory vividness. (a) The half-violin plots represent the overall distributions of relative semantic similarity values at each event regularity level. The boxplots within the half-violin plots span from the first to the third quartiles of the data, the horizontal lines representing the within-event regularity level median values. *ptukey<0.05, **ptukey<0.01, ***ptukey<0.001. (b) Relationships between relative semantic similarity and memory vividness at each event regularity level. The lines and shaded bands represent linear regression lines and 95% confidence intervals. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

There was a significant main effect of event regularity level on memory vividness in our model (new–periodic: β = 1.25, SE = 0.17, CI = [0.86, 1.64], z = 7.48, ptukey < 0.001, OR = 3.49; new–routine: β = 2.67, SE = 0.26, CI = [2.07, 3.72], z = 10.46, ptukey < 0.001, OR = 14.40; periodic–routine: β = 1.42, SE = 0.19, CI = [0.97, 1.86], z = 7.50, ptukey < 0.001, OR = 4.13), but no significant main effect of RSS on memory vividness (β = 0.02, SE = 0.10, CI = [−0.18, 0.23], z = 0.22, p = 0.826, OR = 1.02). Critically, significant effects of RSS on memory vividness were present at independent levels of event regularity, and the directionality of that effect varied (Fig. 5b). With increasing RSS, ‘routine’ events were reported as being recalled with significantly lower vividness (β = −0.65, SE = 0.29, CI = [−1.21, −0.09], z = −2.26, p = 0.024, OR = 0.52). By contrast, with increasing RSS, ‘new’ events were reported as being recalled with significantly higher vividness (β = 0.47, SE = 0.22, CI = [0.03, 0.91], z = 2.10, p = 0.036, OR = 1.60). The interaction between the effect of RSS on memory vividness for ‘new’ compared to ‘routine’ events was significant (β = 1.12, SE = 0.36, CI = [0.41, 1.82], z = 3.10, p = 0.002, OR = 3.06). There was no significant main effect of RSS on memory vividness for ‘periodic’ events (β = 0.01, SE = 0.12, CI = [−0.23, 0.25], z = 0.09, p = 0.927, OR = 1.01). However, the effect of RSS on memory vividness for ‘periodic’ events was significantly different from the effect of RSS on memory vividness for ‘routine’ events (β = 0.66, SE = 0.31, CI = [0.06, 1.26], z = 2.15, p = 0.031, OR = 1.94) and was marginally different from the effect of RSS on memory vividness for ‘new’ events (β = −0.46, SE = 0.25, CI = [−0.94, 0.03], z = −1.86, p = 0.063, OR = 0.63). This suggests that, although event regularity and RSS are significantly related measures (i.e., ‘new’ events tended to be the most semantically distinct, followed by ‘periodic’ and then ‘routine’ events), they do not produce additive effects on memory vividness. Specifically, new events that were more semantically distinct did not lead to the greatest vividness, but quite the opposite, new events with higher RSS being associated with the greatest recall vividness.

Regarding the other predictor variables that were controlled for in this model, RES was one of our measures of interest, and the results are reported later (see Relative emotional distinctiveness predicts greater episodic memory: vividness and episodic detail). There was a significant effect of survey day on memory vividness (β = 0.22, SE = 0.11, CI = [0.01, 0.43], z = 2.05, p = 0.04, OR = 1.25), events that were reported on a later diary day (and therefore closer in time to the memory test) being recalled with greater vividness. There was a significant effect of reported event duration (β = 0.56, SE = 0.14, CI = [0.28, 0.83], z = 3.97, p < 0.001, OR = 1.75), longer events being recalled with greater vividness. Finally, there was no significant effect of narrative length on memory vividness (β = 0.08, SE = 0.12, CI = [−0.14, 0.31], z = 0.72, p = 0.47, OR = 1.08).

A full-random-effects Bayesian model was run next to test the effects of RSS on recalled episodic details. Diverging from the significant effects of RSS on memory vividness, we did not see that RSS had meaningful effects on recalled episodic details, both when collapsing across event regularity level (β = 0.06, CrI = [−0.41, 0.51], pd = 60%), and within event regularity level (new: β = −0.22, CrI = [−1.03, 0.61], pd = 70%; periodic: β = 0.20, CrI = [−0.29, 0.66], pd = 80%; routine: β = 0.21, CrI = [−0.76, 1.11], pd = 67%). However, it should be noted again that all analyses involving recalled episodic details (and memory stability) are based on the subset of total events that were included in the event recall memory test (N = 565), while analyses including memory vividness include all events (N = 1,673), given that vividness ratings were asked for all events during the memory test. Therefore, any discrepancies between effects that involve vividness ratings compared to recalled episodic details are interpreted cautiously. As for the variables we controlled for in the model (i.e., survey day, reported event duration, and narrative length), there was a marginal effect of survey day on recalled episodic details (β = 0.320, CrI = [−0.06, 0.72], pd = 95%), no effect of reported event duration on recalled episodic details (β = 0.35, CrI = [−0.10, 0.77], pd = 94%), and a meaningful, positive effect of narrative length on recalled episodic details (β = 0.85, CrI = [0.15, 1.60], pd = 99%).

We next examined how semantic similarity influenced the stability of memory recall over time, again using a full random effects Bayesian model. We found that RSS had a marginal, negative effect on memory stability when averaging across event regularity level (β = −0.03, CrI = [−0.06, 0.001], pd = 97%). When analyzing this relationship at each event regularity level, there was a meaningful effect of RSS on memory stability for ‘routine’ (β = −0.07, CrI = [−0.13, −0.001], pd = 97%) events, but not for ‘periodic’ (β = −0.02, CrI = [−0.05, 0.02], pd = 83%) or ‘new’ (β = −0.01, CrI = [−0.06, −0.04], pd = 64%) events. This suggests that ‘routine’ events that were highly semantically similar to the rest of the participant’s reported events showed significantly less memory stability (i.e., the description during the diary and recall phases diverged in their semantic content). As for the variables we controlled for in the model (i.e., survey day, reported event duration, and narrative length), we found a marginal, positive effect of survey day on memory stability (β = 0.02, CrI = [−0.004, 0.05], pd = 95%), no effect of reported event duration on memory stability (β = 0.01, CrI = [−0.02, 0.04], pd = 82%), and no effect of narrative length on memory stability (β = 0.0008, CrI = [−0.02, 0.03], pd = 52%).

Taken together, event regularity and RSS demonstrated differing relationships with autobiographical memory outcomes. While event regularity was significantly associated with memory vividness (‘new’ events being the most vivid), RSS modulated this effect, decreasing vividness for ‘routine’ events, but increasing vividness for ‘new’ events. Although event regularity was significantly related to episodic detail (‘new’ events having the greatest number of episodic details at recall)20, RSS showed no significant relationships to recalled episodic detail. Finally, ‘new’ and ‘periodic’ events showed significantly greater memory stability compared to ‘routine’ events, and RSS demonstrated a significant (negative) impact on memory stability for ‘routine’ events. These comparisons provide further evidence that these two sources of novelty in our everyday experiences, namely, participant-labeled novelty (inversely, event regularity) and relative semantic distinctiveness (inversely, RSS), have differing impacts on autobiographical memory outcomes.

Relative emotional distinctiveness predicts greater episodic memory: vividness and episodic detail

Critically, not only can the content of autobiographical experiences be relatively novel, but the feelings elicited by those experiences. Therefore, multivariate emotion signatures were calculated using the participants’ own event-level emotion ratings (RES; see Methods) to test whether the relative peaks and valleys in their ‘emotional landscapes’ were remembered more vividly. First, we tested the relationship between relative emotion similarity (RES) and event regularity, and additionally, RES and RSS. Based on a full-random-effects frequentist regression model (which converged when setting the correlation between random intercept and slope to zero), ‘new’ events were associated with more distinct emotional patterns (had significantly lower RES) compared to ‘periodic’ (new–periodic: β = −0.02, SE = 0.004, CI = [−0.03, −0.006], ptukey = 0.001) and ‘routine’ (new–routine: β = −0.02, SE = 0.008, CI = [−0.04, −0.004], ptukey = 0.01) events (Fig. 6a). ‘Periodic’ and ‘routine’ events were not significantly different (periodic–routine: β = −0.007, SE = 0.007, CI = [−0.02, 0.01], ptukey = 0.56). Further, greater relative emotional distinctiveness significantly predicted greater relative semantic distinctiveness when collapsing across event regularity level (β = 0.02, SE = 0.004, CI = [0.01, 0.03], p < 0.001). At each event regularity level, there was a significant effect of RES on RSS for ‘new’ events (β = 0.02, SE = 0.007, CI = [0.00, 0.03], p = 0.04), a significant effect of RES on ‘periodic’ events (β = 0.02, SE = 0.005, CI = [0.01, 0.03], p < 0.001), and no significant effect of RES on ‘routine’ events (β = 0.009, SE = 0.009, CI = [−0.01, 0.03], p = 0.33).

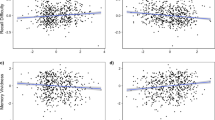

Effect of event regularity on relative emotion similarity, and relative emotion similarity on memory vividness. (a) The half-violin plots represent the overall distributions of relative emotion similarity values at each event regularity level. The boxplots within the half-violin plots span from the first to the third quartiles of the data, the horizontal lines representing the within-event regularity median values. *ptukey<0.05, **ptukey<0.01, ***ptukey<0.001. (b) Relationships between relative emotion similarity and memory vividness at each event regularity level. The lines and shaded bands represent the linear regression lines and 95% confidence intervals. The line representing the effect of relative emotion similarity on memory vividness for routine events extends beyond the shaded region where predictions are extrapolated. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Knowing that RES was positively related to event regularity and RSS, the impact of RES on the memory measures was analyzed next. There was a significant main effect of RES on memory vividness (Fig. 6b): events that were experienced with greater emotional distinctiveness were given higher vividness ratings at recall (β = −0.34, SE = 0.10, CI = [−0.54, −0.14], z = −3.30, p < 0.001, OR = 0.71). When analyzing this relationship at each event regularity level, there was no significant effect of RES on memory vividness for ‘new’ (β = −0.30, SE = 0.20, CI = [−0.69, 0.08], z = −1.53, p = 0.126, OR = 0.74) events, a marginal, negative effect for ‘routine’ events (β = −0.45, SE = 0.26, CI = [−0.97, 0.07], z = −1.69, p = 0.091, OR = 0.64), and a significant, negative effect for ‘periodic’ events (β = −0.33, SE = 0.12, CI = [−0.57, −0.08], z = −2.63, p = 0.009, OR = 0.72). Full-random-effects Bayesian models were used next to test how RES predicted episodic details at recall and memory stability. We found that greater emotional distinctiveness meaningfully predicted greater recalled episodic details when collapsing across event regularity level (β = −0.42, CrI = [−0.85, −0.01], pd = 98%). Within event regularity level, this relationship remained meaningful for ‘new’ (β = −0.88, CrI = [−1.72, −0.10], pd = 98%) and ‘periodic’ (β = −0.52, CrI = [−1.00, −0.05], pd = 98%) events, but not for ‘routine’ (β = 0.09, CrI = [−0.73, 0.90], pd = 59%) events. RES did not meaningfully predict memory stability when collapsing across event regularity level (β = −0.02, CrI = [−0.05, 0.007], pd = 93%), or within each event regularity level for ‘new’ (β = −0.002, CrI = [−0.06, 0.05], pd = 52%) and ‘periodic’ (β = −0.01, CrI = [−0.05, 0.02], pd = 79%) events. There was, however, a marginal, positive effect of emotional distinctiveness on memory stability for ‘routine’ events (β = −0.05, CrI = [−0.10, 0.01], pd = 95%). These results suggest that emotional distinctiveness positively impacts memory vividness and episodic details at recall, and may have a marginal, positive effect on the memory stability for ‘routine’ events.

Participant-labeled novelty and relative semantic distinctiveness have differing relationships with the emotions elicited by an event

Our next analyses examined how event regularity related to emotions felt during the event. For each reported event, participants rated several feelings using a Likert scale23. All ratings were analyzed: happy, positive, sad, negative, excited, calm, and afraid. However, given that happy and positive ratings (r(1,671) = 0.85, p < 0.001) and sad and negative ratings (r(1,671) = 0.66, p < 0.001) showed significant correlations and demonstrated similar effects, only happy and sad ratings are reported here (along with excited, calm, and afraid ratings) to avoid redundancy.

Based on full-random-effects ordinal regressions (CLMMs) with RSS as an additional predictor, event regularity had significant effects on happy, excited, calm, and afraid ratings, while no significant relationships were found for sad ratings (Fig. 7). Importantly, new events were given significantly higher happy ratings compared to routine events (new–routine: β = 0.48, SE = 0.20, CI = [0.01, 0.95], z = 2.40, ptukey = 0.04, OR = 1.62). There was a marginal difference in happy ratings between new and periodic events (new–periodic: β = 0.33, SE = 0.14, CI = [−0.0001, 0.66], z = 2.34, ptukey = 0.05, OR = 1.39) and no significant difference between periodic and routine events (periodic–routine: β = 0.15, SE = 0.16, CI = [−0.22, 0.54], z = 0.93, ptukey = 0.62, OR = 1.16). Further, ‘new’ events were rated significantly higher in excitement than ‘periodic’ (new–periodic: β = 0.47, SE = 0.15, CI = [0.12, 0.81], z = 3.19, ptukey = 0.004, OR = 1.60) and ‘routine’ (new–routine: β = 0.94, SE = 0.23, CI = [0.41, 1.47], z = 4.17, ptukey < 0.001, OR = 2.57) events. ‘Periodic’ events were rated significantly higher in excitement than ‘routine’ (periodic–routine: β = 0.48, SE = 0.19, CI = [0.04, 0.91], z = 2.55, ptukey = 0.03, OR = 1.61) events. ‘New’ events were also reported with significantly higher afraid ratings compared to ‘periodic’ (new–periodic: β = 0.41, SE = 0.17, CI = [0.006, 0.81], z = 2.38, ptukey = 0.045, OR = 1.51) and ‘routine’ (new–routine: β = 0.85, SE = 0.27, CI = [0.23, 1.48], z = 3.18, ptukey = 0.004, OR = 2.35) events. There was no significant difference in afraid ratings when comparing ‘periodic’ to ‘routine’ events (periodic–routine: β = 0.44, SE = 0.25, CI = [−0.15, 1.04], z = 1.75, ptukey = 0.19, OR = 1.56). Inversely, ‘new’ events were given significantly lower calm ratings compared to ‘periodic’ (new–periodic: β = −0.32, SE = 0.13, CI = [−0.62, −0.03], z = −2.57, ptukey = 0.03, OR = 0.72) and ‘routine’ (new–routine: β = −0.65, SE = 0.19, CI = [−1.10, −0.20], z = −3.41, ptukey = 0.002, OR = 0.52) events. There was no significant difference in calm ratings between ‘periodic’ and ‘routine’ events (periodic–routine: β = −0.33, SE = 0.18, CI = [−0.75, 0.09], z = 1.83, ptukey = 0.16, OR = 0.72). The effect of event regularity on sad ratings produced no significant or marginal differences (new–periodic: β = 0.14, SE = 0.18, CI = [−0.29, 0.57], z = 0.79, ptukey = 0.71, OR = 1.15; new–routine: β = 0.46, SE = 0.31, CI = [−0.25, 1.18], z = 1.51, ptukey = 0.28, OR = 1.59; periodic–routine: β = 0.32, SE = 0.25, CI = [−0.28, 0.90], z = 1.28, ptukey = 0.41, OR = 1.37). Thus, we found that individual emotion ratings, for the most part, varied as a function of event regularity. Overall, ‘new’ events were associated with greater happiness, excitement, and fear. Inversely, ‘new’ events elicited less calmness, and had no significant effect on sadness.

We next asked how RSS was related to reported emotions experienced during each event (Fig. 8). We found that RSS predicted significantly higher happy (β = 0.87, SE = 0.11, CI = [0.65, 1.10], z = 7.58, p < 0.001, OR = 2.39), excited (β = 0.35, SE = 0.11, CI = [0.13, 0.57], z = 3.07, p = 0.002, OR = 1.42), and calm (β = 0.76, SE = 0.12, CI = [0.54, 0.99], z = 6.62, p < 0.001, OR = 2.14) ratings when collapsing across event regularity level. Further, greater RSS predicted significantly lower sad (β = −0.56, SE = 0.13, CI = [−0.82, −0.31], z = 04.34, p < 0.001, OR = 0.57) and afraid (β = −0.62, SE = 0.13, CI = [−0.87, −0.37], z = −4.88, p < 0.001, OR = 0.54) ratings when collapsing across event regularity level. When analyzing these relationships within event regularity level, effects remained significant except for the effect of RSS on afraid and excited ratings for routine events, which were not significant, and the effect of RSS on sad ratings for routine events, which was marginal (see Supplemental Material).

Effect of relative semantic similarity on event-level emotion ratings. The lines and shaded bands represent linear regression lines and 95% confidence intervals. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Significance level is based on main effects (i.e., collapsing across event regularity level). Within-event regularity regression lines are shown for visual interpretation.

In sum, similar to the impacts found on memory, event regularity and RSS were differentially related to the emotions experienced during the event. New events were associated with the greatest happiness, excitement, and fear, as well as less calmness, but did not elicit significantly greater sadness compared to periodic and routine events. RSS generally supported positive emotions (i.e., happiness, excitement, and calmness), while minimizing negative emotions (i.e., sadness and fear). Taken together, our results suggest that ‘new’ events that are more semantically similar to the other within-participant reported events not only lead to the greatest memory vividness later on, but also are associated with the greatest happiness and excitement in the moment.

Discussion

In the current study, we explored how variation in event novelty impacted emotional states and long-term measures of memory recall. We found that the participant-labeled novelty (i.e., a ‘new’ event) and emotional distinctiveness of experiences increased memory vividness and episodic detail at recall. Participant-labeled novelty was uniquely associated with greater memory stability across time. A second major finding, however, was that memory vividness for ‘new’ events benefitted from greater relative semantic similarity (i.e., a semantic ‘scaffold’), rather than more ‘maximal’ novelty.

The ‘Predictive Interactive Multiple Memory Signals’ (PIMMS)37,38 model outlines why the presence of both novelty and semantic similarity may benefit memory more than maximal novelty. According to this PIMMS model, ‘maximal’ novelty, a scenario in which an individual encounters unknown objects in an unknown environment, may produce minimal learning given the lack of prior experience to reference. Critically, our results test this model using participant’s day-to-day real-world experiences and include important variance, given that we utilize continuous measures and different types of novelty. This approach afforded the opportunity to examine specific compositions of novelty and congruency and their impact on episodic recall. In line with the PIMMS model, our results show that ‘new’ experiences with a stronger semantic scaffold (higher RSS), which may serve as an informative prior, are later remembered with greater vividness than ‘new’ events that have less of a semantic scaffold (lower RSS), suggesting a weak or flat prior (and therefore a small or nonexistent prediction error, which leads to minimal learning).

However, it should be emphasized that, in our study, new events that were low in relative semantic similarity (more ‘maximally’ novel) were still remembered more vividly than ‘periodic’ and ‘routine’ events, showing that there is still some memory benefit related to more maximal, or additive, novelty. Prior work has suggested that memory for absolute novelty and contextual novelty rely on distinct hippocampal-related processes39,40. There is also evidence showing a gradual decline in hippocampal activity during continued novelty exposure41,42,43, suggesting that the relationship between novelty and hippocampal engagement changes as a function of contextual stability, or familiarity. Bein and colleagues44 have outlined various neural mechanisms that may be recruited depending on how incoming information relates to prior knowledge. Future neuroimaging work should be conducted to investigate how the relative semantic similarity of novel autobiographical events impacts these underlying neural substrates, and how that in turn is related to different episodic memory outcomes.

It will also be important to investigate whether different types of novelty (participant-labeled novelty, semantic novelty, and emotional novelty) modulate memory at distinct stages in the life of a memory. It is known that incoming novel information benefits from hippocampal engagement during encoding, supporting the formation of an episodic memory trace45,46,47. Research has shown that when this novel information aligns with pre-existing schemas, it is more readily integrated into neocortical memory networks, such as the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), which facilitates rapid consolidation12,13 and stabilizes memory traces48. Work has also demonstrated that the magnitude of post-encoding connectivity between the hippocampus and mPFC is related to the long-term structured representation of schematic knowledge in the mPFC49,50. Finally, based on prior work that utilized a variety of approaches (i.e., imaging, mouse genetics, pharmacological and anatomical lesions, testing both humans and animals with mPFC damage) a model has been proposed suggesting that, during successful delayed recall, the hippocampus and the mPFC interact. More specifically, the mPFC supports the retrieval of goal-relevant information and the hippocampus reconstructs episodic content51,52,53. Our findings suggest that ‘new’ events may enhance hippocampal encoding allowing for the formation of distinct, episodic memory traces, while semantic similarity (RSS) may reflect mPFC engagement and schema-based consolidation. Another non-mutually exclusive possibility is that post-encoding hippocampal reactivation will prioritize novel events while cortical reactivation will be enhanced for novel experiences that contain more of a semantic scaffold (high RSS). Recent empirical work has shown that cortical, but not hippocampal, reactivation is increased for events that are repeated54. Focusing on emotional distinctiveness (RES), this type of novelty may primarily engage the arousal system at encoding, triggering neuromodulatory responses that prioritize memory55 and initiate ‘tag-and-capture’ processes9. Emotional distinctiveness may recruit the amygdala, which has been shown to support durable emotion–item associations, thus making them more resistant to forgetting56. Although difficult to gather neural data during naturalistic experience, future work can aim to scan participants during the recall of these distinct events to test these hypotheses above which are based on a wealth of controlled laboratory studies.

Although memory vividness, episodic detail at recall, and memory stability were significantly related memory outcomes, some of our results demonstrated apparent divergences between the effects of novelty on these memory outcomes. However, this should be interpreted cautiously at this time, given that we had reduced power for episodic details and memory stability (due to about one-third of the events having corresponding recalls). Future work will need to investigate whether the effects regarding episodic detail and memory stability found in this study persist with a greater sample of event recalls, or the effects change due to our sample size being underpowered.

Shifting from memory outcomes to event-level emotion outcomes, participant-labeled novelty was associated with greater happiness, excitement, and fear, as well as less calmness. This increase in happiness ratings for ‘new’ events is in line with emerging evidence on real-world novelty and emotion. As mentioned previously, prior work found that greater spatial exploration21,22 and greater event-level composite uniqueness19 were associated with greater positive affect (positive affect in these cases representing an averaged value that did not represent one specific emotion). While those studies investigated day-level positive mood, the current data show that specific emotions such as happiness and excitement that were elicited by distinct events are related to event-level novelty. Furthermore, our findings extend prior work by showing that relative semantic similarity supported positive emotions and minimized negative emotions. This suggests that ‘new’ events with a scaffolding of semantic similarity provided the greatest benefit to emotional well-being, specifically supporting happiness and excitement. This benefit of relative semantic similarity in the context of emotion is reminiscent of the ‘mere-exposure effect’, which demonstrates that repeated exposure to a stimulus (i.e., familiarity) can increase positive affect or ‘liking’ of that stimulus57,58. This ‘liking’ of familiarity relates to prior animal behavior work59, rats having demonstrated a preference for a familiar over a novel stimulus when first exposed to a novel environment, then preferred the novel stimulus once they were habituated to the environment. These rats additionally changed their preference back to the familiar stimulus after just being exposed to a different novel environment. This suggests that rats prefer a degree of relative familiarity in novel contexts, rather than ‘maximal’ novelty. Our results demonstrate the impact of differing magnitudes of novelty in humans, showing that ‘maximal’ novelty is not ideal for episodic remembering and emotional well-being. Instead, it was the cooperation of novelty and relative semantic similarity that led to the greatest long-term memory vividness, and the greatest happiness and excitement during the event itself.

Conclusion

Collectively, the current findings highlight the interplay between everyday novelty and congruency in modulating participants’ emotional states in the moment and the richness of their later autobiographical memory. We refer to this interplay as the ‘something old, something new’ principle. Further, our finding that a semantic scaffold further boosts memory vividness for new events supports the consideration of ‘absolute novelty’ and ‘absolute congruency’ as two ends of a continuous spectrum, rather than separate, binary factors, especially when analyzing autobiographical data. Our work also highlights how the operationalization of novelty can impact its relationship to memory and emotion, which may assist in disentangling potential conflicting findings in novelty and memory research. Additionally, collecting and subsequently testing memory for autobiographical events using a daily diary paradigm (i.e., utilizing a prospective memory design) provides an exemplar of each participant’s day-to-day experiences, and in our case, the emotions associated with those experiences. Such data are well-suited for NLP techniques, which have only become a recent possibility with much to be explored60. Our results, as well as other recent work61,62,63, provide confidence that combining dense-sampling paradigms with NLP-driven analyses are valuable trails worth trekking, all in pursuit of better understanding the complex, multidimensional stories that provide measurement and depth to our lives.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author (ld24@columbia.edu) on reasonable request.

References

von Restorff, H. Über die wirkung von bereichsbildungen Im Spurenfeld. Psychol. Forsch. 18, 299–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02409636 (1933).

Tulving, E. & Kroll, N. Novelty assessment in the brain and long-term memory encoding. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2 (3), 387–390. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03210977 (1995).

Li, S., Cullen, W. K., Anwyl, R. & Rowan, M. J. Dopamine-dependent facilitation of LTP induction in hippocampal CA1 by exposure to Spatial novelty. Nat. Neurosci. 6 (5), 526–531. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1049 (2003).

Ranganath, C. & Rainer, G. Neural mechanisms for detecting and remembering novel events. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1052 (2003).

Lisman, J. E. & Grace, A. A. The Hippocampal-VTA loop: controlling the entry of information into Long-Term memory. Neuron 46 (5), 703–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.002 (2005).

Lisman, J., Grace, A. A. & Düzel, E. A neohebbian framework for episodic memory; role of dopamine-dependent late LTP. Trends Neurosci. 34 (10), 536–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2011.07.006 (2011).

Schomaker, J. & Meeter, M. Short- and long-lasting consequences of novelty, deviance and surprise on brain and cognition. Neurosci. Biobehavioral Reviews. 55, 268–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.05.002 (2015).

Mather, M., Clewett, D., Sakaki, M. & Harley, C. W. Norepinephrine ignites local hotspots of neuronal excitation: how arousal amplifies selectivity in perception and memory. Behav. Brain Sci. 39, e200. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X15000667 (2016).

Dunsmoor, J. E., Murty, V. P., Clewett, D., Phelps, E. A. & Davachi, L. Tag and capture: how salient experiences target and rescue nearby events in memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 26 (9), 782–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2022.06.009 (2022).

Sekeres, M. J., Schomaker, J., Nadel, L. & Tse, D. To update or to create? The influence of novelty and prior knowledge on memory networks. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 379 20230238. (1906). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2023.0238 (2024).

Craik, F. I. M. & Tulving, E. Depth of processing and retention of words in episodic memory. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 104 (3), 268–294. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.104.3.268 (1975).

Tse, D. et al. Schemas and memory consolidation. Science 316 (5821), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1135935 (2007).

van Kesteren, M. T., Ruiter, D. J., Fernández, G. & Henson, R. N. How schema and novelty augment memory formation. Trends Neurosci. 35 (4), 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2012.02.001 (2012).

Ghosh, V. E. & Gilboa, A. What is a memory schema? A historical perspective on current neuroscience literature. Neuropsychologia 53, 104–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.11.010 (2014).

Bein, O. et al. Delineating the effect of semantic congruency on episodic memory: the role of integration and relatedness. PLOS ONE. 10 (2), e0115624. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115624 (2015).

van Kesteren, M. T. R., Rignanese, P., Gianferrara, P. G., Krabbendam, L. & Meeter, M. Congruency and reactivation aid memory integration through reinstatement of prior knowledge. Sci. Rep. 10, 4776. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61737-1 (2020).

Greve, A., Cooper, E., Tibon, R. & Henson, R. N. Knowledge is power: prior knowledge aids memory for both congruent and incongruent events, but in different ways. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 148 (2), 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000498 (2019).

Quent, J. A., Greve, A. & Henson, R. N. Shape of U: the nonmonotonic relationship between Object–Location memory and expectedness. Psychol. Sci. 33 (12), 2084–2097. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976221109134 (2022).

Meade, M. E. et al. Unique events improve episodic richness, enhance mood, and alter the perception of time during isolation. Sci. Rep. 14, 29439. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80591-z (2024).

Schelkun, V., Gasser, C., Lockwood, K., Welch, E., & Davachi, L. (PsyArXiv). Novel experiences create a penumbra of enhanced autobiographical memory: evidence from a daily diary study. Retrieved from osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/vkq6a_v1.

Heller, A. S. et al. Association between real-world experiential diversity and positive affect relates to hippocampal–striatal functional connectivity. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 800–804. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-0636-4 (2020).

Saragosa-Harris, N. M. et al. Real-World exploration increases across adolescence and relates to Affect, risk Taking, and social connectivity. Psychol. Sci. 33 (10), 1664–1679. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976221102070 (2022).

Likert, R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives Psychol. 140, 55 (1932).

Reimers, N. & Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: sentence embeddings using Siamese BERT-networks. Proc. Conf. Empir. Methods Nat. Lang. Process. 3982-3992 https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/d19-1410 (2019).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Levine, B., Svoboda, E., Hay, J. F., Winocur, G. & Moscovitch, M. Aging and autobiographical memory: dissociating episodic from semantic retrieval. Psychol. Aging. 17 (4), 677–689. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.17.4.677 (2002).

Auger, T. & Saroyan, E. Overview of the openai APIs. In: generative AI for web development. Apress https://doi.org/10.1007/979-8-8688-0885-2_6 (2024).

Gelman, A. Scaling regression inputs by dividing by two standard deviations. Stat. Med. 27 (15), 2865–2873. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3107 (2008).

H. Wickham. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. (Springer-Verlag New York, 2016).

Christensen, R. ordinal-Regression Models for Ordinal Data. R package version 2023.12–4.1, (2023). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ordinal

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear Mixed-Effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67 (1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01 (2015).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. LmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82 (13), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13 (2017).

Lüdecke, D., Ben-Shachar, M., Patil, I. & Makowski, D. Extracting, Computing and Exploring the Parameters of Statistical Models using R. Journal of Open Source Software, 5(53), 2445. (2020). https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.02445 (2020).

Lenth, R. & emmeans Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. (2024).

Tukey, J. W. Comparing individual means in the analysis of variance. Biometrics 5 (2), 99–114 (1949).

Bürkner, P-C. Brms: an R package for bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 80 (1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v080.i01 (2017).

Henson, R. N. & Gagnepain, P. Predictive, interactive multiple memory systems. Hippocampus 20 (11), 1315–1326. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.20857 (2010).

Quent, J. A., Henson, R. N. & Greve, A. A predictive account of how novelty influences declarative memory. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 179, 107382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2021.107382 (2021).

Kafkas, A. & Montaldi, D. How do memory systems detect and respond to novelty? Neurosci. Lett. 680, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2018.01.053 (2018).

Duszkiewicz, A. J., McNamara, C. G., Takeuchi, T. & Genzel, L. Novelty and dopaminergic modulation of memory persistence: A Tale of two systems. Trends Neurosci. 42 (2), 102–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2018.10.002 (2019).

Strange, B. A. & Dolan, R. J. Adaptive anterior hippocampal responses to oddball stimuli. Hippocampus 11 (6), 690–698. https://doi.org/10.1002/hip.1084 (2001).

Bunzeck, N. & Düzel, E. Absolute coding of stimulus novelty in the human substantia nigra/VTA. Neuron 51, 369–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.021 (2006).

Murty, V. P., Ballard, I. C., Macduffie, K. E., Krebs, R. M. & Adcock, R. A. Hippocampal networks habituate as novelty accumulates. Learn. Memory (Cold Spring Harbor N Y). 20 (4), 229–235. https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.029728.112 (2013).

Bein, O., Gasser, C., Amer, T., Maril, A. & Davachi, L. Predictions transform memories: how expected versus unexpected events are integrated or separated in memory. Neurosci. Behav. Reviews. 153 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105368 (2023).

Paller, K. A. & Wagner, A. D. Observing the transformation of experience into memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 6 (2), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01845-3 (2002).

Davachi, L., Mitchell, J. P. & Wagner, A. D. Multiple routes to memory: Distinct medial temporal lobe processes build item and source memories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100(4) 2157–2162. (2003). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0337195100

Moscovitch, M., Cabeza, R., Winocur, G. & Nadel, L. Episodic memory and beyond: the hippocampus and neocortex in transformation. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 67, 105–134. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143733 (2016).

Euston, D. R., Gruber, A. J. & McNaughton, B. L. The role of medial prefrontal cortex in memory and decision making. Neuron 76 (6), 1057–1070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.002 (2012).

Tompary, A. & Davachi, L. Consolidation promotes the emergence of representational overlap in the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex. Neuron 96 (1), 228–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.005 (2017). .e5.

Tompary, A. & Davachi, L. Integration of overlapping sequences emerges with consolidation through medial prefrontal cortex neural ensembles and hippocampal–cortical connectivity. eLife 13, e84359. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.84359 (2024).

Frankland, P. & Bontempi, B. The organization of recent and remote memories. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1607 (2005).

Preston, A. R. & Eichenbaum, H. Interplay of hippocampus and prefrontal cortex in memory. Curr. Biol. 23 (17), R764–R773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.041 (2013).

Eichenbaum, H. Prefrontal–hippocampal interactions in episodic memory. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2017.74 (2017).

Yu, W., Zadbood, A., Chanales, A. J. H. & Davachi, L. Repetition dynamically and rapidly increases cortical, but not hippocampal, offline reactivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 121(40): e2405929121. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2405929121

Mather, M., Clewett, D., Sakaki, M. & Harley, C. W. Norepinephrine ignites local hotspots of neuronal excitation: how arousal amplifies selectivity in perception and memory. Behav. Brain Sci. 39, e200. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X15000667 (2016).

Yonelinas, A. P. & Ritchey, M. The slow forgetting of emotional episodic memories: an emotional binding account. Trends Cogn. Sci. 19 (5), 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2015.02.009 (2015).

Zajonc, R. B. Attitudinal effects of Mere exposure. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 9 (2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025848 (1968).

Zajonc, R. B. Mere exposure: A gateway to the subliminal. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 10 (6), 224–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00154 (2001).

Sheldon, A. B. Preference for familiar versus novel stimuli as a function of the familiarity of the environment. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 67, 516–521. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0027305 (1969).

Fenerci, C., Cheng, Z., Addis, D. R., Bellana, B. & Sheldon, S. Studying memory narratives with natural Language processing. Trends Cogn. Sci. 29 (6), 516–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2025.02.003 (2025).

Sheldon, S. et al. Differences in the content and coherence of autobiographical memories between younger and older adults: insights from text analysis. Psychol. Aging. 39 (1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000769 (2024).

van Genugten, R. D. & Schacter, D. L. Automated scoring of the autobiographical interview with natural Language processing. Behav. Res. 56, 2243–2259. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-023-02145-x (2024).

Beech, A. et al. Using natural Language processing to identify patterns associated with depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 367, 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2025.01.139 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Sophia Faisal and Mia Soviero for their assistance with data scoring.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (7RO1MH074692-13).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.W. was involved in methodology, formal analysis, visualization, and writing. V.S., C.G., and K.L. were involved in conceptualization, methodology, investigation, and data curation. L.D. was involved in conceptualization, methodology, supervision, funding acquisition, and writing. All authors provided feedback and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Welch, E., Schelkun, V., Gasser, C. et al. Rich autobiographical memory benefits from both novelty and similarity to other daily experiences. Sci Rep 15, 45237 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29036-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29036-9