Abstract

In this paper, the effectiveness of various waste sorbents (coffee grounds, hazelnut shells, and compost) was compared with sorbents such as chitosan and bentonite for the removal of heavy metals: zinc, lead, cadmium, and copper (Zn, Pb, Cd, Cu, respectively) from aqueous solution. Their composition, ash content, and moisture content were characterized. The BET method was used to determine the surface area. The size and type of pores were determined using the BJH and DFT methods. The presence of functional groups was identified using FTIR. The sorbents differed significantly in terms of pore quantity and size, as well as specific surface area. The highest specific surface area of 40 m²/g was determined for bentonite, while for coffee it was below the detection limit, at 2 m²/g. FTIR analysis confirmed the presence of numerous and diverse functional groups characteristic of each sorbent, e.g., C = O, C-O-C, O-H. All materials effectively removed heavy metals. For the smallest mass of sorbents used (0.1 g), the following metal removal efficiencies were achieved: 95% Zn (chitosan), 99% Cu (compost), 95% Pb (hazelnut shell), and 72% Cd (hazelnut shell). Bentonite proved to be the least effective sorbent of all the materials analyzed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in utilizing waste materials as sorbents in water purification processes, particularly for the removal of heavy metals1,2. Water contamination with heavy metals, such as cadmium, lead, mercury, arsenic, and zinc poses a serious threat to the natural environment and human health3. Once released into aquatic ecosystems, these metals can accumulate in living organisms, causing several health problems, including neurological disorders, kidney disease and even cancer4,5. In addition, their presence in the aquatic environment can significantly affect the quality of drinking water, which poses an urgent task for scientists and engineers to develop effective, economical, and ecological methods for their removal6.

Traditional technologies used in water purification, such as coagulation, chemical precipitation, ion exchange, reverse osmosis or membrane separation processes, are effective, but often expensive and require the use of large amounts of chemical reagents7,8,9. In addition, they often generate enormous amounts of secondary waste, which burdens the environment10. Furthermore, many of these methods, such as reverse osmosis or advanced oxidation processes, incur significant operational costs11. In response to these challenges, there is growing interest in using cheap, widely available waste materials that can be transformed into effective heavy metal sorbents12. This approach not only reduces the costs associated with water treatment but also contributes to waste management, which is important in the context of a circular economy13.

Adsorption processes commonly utilize materials such as activated carbon, zeolites, and metal oxides as adsorbents. These adsorbents are characterized by high specific surface area and the ability to absorb various substances, including heavy metals. Bentonite and chitosan are also among adsorbents with high purification efficiency. Chitosan, due to the presence of amine and hydroxyl groups in its structure, exhibits high complexing and ion exchange properties, enabling effective binding of ions such as Cu(II), Pb(II), and Cr(VI)14,15. However, chitosan has broader applications in medicine due to its antihemorrhagic and antibacterial properties. Bentonite, a clay rich in montmorillonite, is characterized by a sorption mechanism based primarily on cation exchange and surface adsorption. Its advantages include widespread availability, low cost, and stability over a wide pH range, making it an attractive material for large-scale applications16.

Waste materials such as ash, rice husks, wood chips, sawdust, sewage sludge, as well as agricultural waste such as straw, nutshells or fruit waste, are characterized by high sorption potential17. Their ability to bind metal ions results from their porous structure and the presence of functional groups such as hydroxyl, carboxyl, or amine, which can interact with metals through adsorption processes18. Moreover, these materials can be chemically and physically modified, which allows for further enhancement of their sorption properties19. For example, chemical activation using acids, bases, or salts, as well as heat treatment, can significantly improve the material’s ability to absorb specific contaminants20.

One of the key advantages of using waste materials as sorbents is their wide availability and low acquisition costs. In contrast to commercial sorbents such as activated carbon, zeolites, or polymers, waste materials are typically by-products of other various industrial or agricultural processes21. Their application in water purification processes not only contributes to waste reduction but also decreases reliance on costly purification technologies22. For example, fly ash, a by-product of coal combustion in power plants, has good sorption properties for hevy metals. Thus, use in water purification can be an effective and cheap solution to the pollution problem23. Coffee grounds, the leftover residue obtained after brewing coffee, have potential applications as adsorbents for removing pollutants from water due to their porous structure24. Hazelnut shells or compost, due to their low ash and moisture content and the presence of oxygen functional groups derived from the lignocellulosic complex, can become effective sorbents of pollutants, such as heavy metals, dyes, or different toxic gases25.

Sorption processes involving waste materials can be conducted in several ways, depending on the type of pollutants and operating conditions. In this process, contaminated water flows through a sorption bed, and metal ions are retained on the sorbent surface. However, the key challenge is to optimize the process to maximize the efficiency and selectivity of the sorbent for specific metals. In this context, research on the modification of waste materials and understanding the mechanisms of sorption are crucial for developing more advanced technological solutions1.

In addition to chemical and physical modifications, the proper preparation of sorbents is also of significant importance. For example, drying, grinding and even granulation of waste materials can significantly affect their sorption efficiency. Moreover, laboratory and experimental studies are often necessary to determine the optimal process conditions, such as pH, temperature, metal concentration, or contact time between water and sorbent26. It is also worth noting that some waste materials may exhibit different sorption properties depending on their origin, which require an individual approach to each of them.

Despite the numerous advantages, there are also certain challenges to the wide implementation of such solutions on an industrial scale. One of them is the variability of the properties of waste materials, which may differ depending on the source of origin. Another challenge is the scalability of sorption processes involving waste materials, which requires further research on the optimization of the technology and understanding of sorption mechanisms on a macro scale. An important aspect is also the assessment of the impact of long-term use of waste sorbents on the environment, including the analysis of the possibilities of regenerating sorbents and their further use after the sorption process is complete.

The aim of the research presented in the article was to compare the effectiveness of removing selected heavy metals such as zinc, lead, cadmium, and copper (Zn, Pb, Cd, Cu) from solutions by sorbents of waste origin (coffee grounds, hazelnut shells, compost) and natural origin (chitosan, bentonite).

Materials and methods

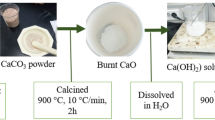

Sorbents

The five types of sorbents were used in the study: two sorbents: bentonite (CETCO, Poland) and chitosan (ChitoClear 43,000-HQG10, Poland), and three sorbents derived from waste: coffee grounds (Robusta and Arabica mix, NovoDia cafés), ground walnut shells (Corylus avellana, Poland), and compost (ZPHU UMEX, Poland). The comparative evaluation included determining the removal efficiency of heavy metals (Zn, Cu, Cd, and Pb) from aqueous solutions by sorbents derived from waste compared to bentonite (control), as a primary raw material used as a pollutant sorbent, and chitosan, as an organic sorbent with high adsorption efficiency.

Sorbents characterization

Moisture content

The moisture content in the analyzed samples of sorbents was determined by the PN-EN ISO 18,134–2:2017–03 standard. To determine this parameter, 1 ± 0.1 g of the analyzed material was weighed into a ceramic vessel dried to a constant mass, and placed in a laboratory dryer heated to 105 ± 5 °C for 90 min. After the sample had cooled, the mass was measured.

Ash content

The PN-ISO 1171 standard method determined the ash content. The test consisted of weighing 1 ± 0.1 g of the analyzed material in a ceramic vessel, which was then placed in a muffle furnace at room temperature. The furnace was heated to a temperature of 815 ± 10 °C and the set temperature was maintained for 90 min. After the sample had cooled, the mass was measured.

pHpzc

The determination of the surface neutralization point was performed using the method presented by27. Approximately 1 ± 0.01 g of the tested sorbent was weighed into polypropylene containers and 20 cm3 of previously prepared CO2-free distilled water was poured in and stirred for 24 h at 140 rpm. After 24 h, the pH of the solution was measured using a pH meter, thereby determining the pHpzc value.

Elemental analysis of C, H, N, S

The analysis of elemental elements in the form of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and sulfur of the sorbents was performed using a CHNS microanalyzer from Elementar Vario EL II, using the sample combustion method. Sorbent weights weighing 1.2–1.6 mg ± 0.001 mg were placed in tin capsules and analyzed by combustion in oxygen. In the case of determining the CHNS content level, sulfanilic acid was used as a standard. The content of the analyzed elements was determined after calculating the coefficients for the standard used. The analyses were performed twice for each sample, and below 0.3% of the content (detection limit of the device) the result was considered insignificant.

Physical adsorption

The porosity of the sorbents was assessed based on N2 adsorption isotherms (77 K) determined using the AUTOSORB IQ analyzer from Quantachrome. Before analysis, the samples were degassed under vacuum (10–7 bar) at 50 °C for 48 h. Based on the obtained data from the physisorption process, the specific surface area, volume, and average pore size, and the volume and surface area of pores were determined. The specific surface area was determined based on the multipoint Brunauer, Emmett, and Teller (MBET) method. The volume and average size of micropores were calculated based on the Quenched Solid Density Functional Theory (QSDFT). The Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) and Density Functional Theory (DFT) method was used to determine the size of micro- and mesopores and their capacity.

FTIR spectroscopy

A Jasco FTIR 6200 Fourier transform spectrometer was used to identify the type of functional groups that may be present in the analyzed sorbents. Infrared spectra were recorded by the ATR method with a diamond crystal using a Pike attachment. A TGS detector was used for spectral measurements in the spectral range of 4000–650 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1.

Sorption experiments

A specific mass of the selected sorbent (chitosan, bentonite, soil, coffee beans, hazelnut shells, only one at time) was introduced into a 200 ml conical flask. 50 ml of an aqueous solution containing a single selected heavy metal (Zn, Cd, Cu, Pb) of known concentration was introduced. The initial metal concentration in the solution was 10 mg/L, except for cadmium, which was 1 mg/L (pH about 5–6 from different metal ions solutions). Different sorbent masses were used: 5, 3, 1, 0.5, 0.25, and 0.1 g. The sample was shaken on a shaker at room temperature for 24 h at 100 rpm to establish sorption equilibrium. The sample was filtered through a filter to remove the remaining sorbent. Then the samples were subjected to determination of the heavy metal content in the filtrate. The experiments were conducted separately for each sorbent and each metal. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and the results are presented as the average value of three measurements.

Measurement of heavy metal content

Heavy metals (Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn) concentrations were measured in the filtered extracts after sorption using a flame atomic absorption spectrometry (FAAS PinAAcle 900F PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Detection limits were 0.01 mg/L for Cd; 0.03 mg/L for Cu and Pb; and 0.02 mg/L for Zn.

Results and discussion

Sorbents characterization

As part of the research, selected samples of natural sorbents were analyzed for moisture content, ash content, and elemental analysis (Table 1). In all analyzed samples, the moisture content did not exceed 10%. The highest ash content was observed in bentonite and compost—33.15% and 19.70%, respectively.

Elemental analysis includes the determination of basic elements present in sorbents. The content of individual elements was calculated considering moisture. The oxygen content in the tested samples, taking into account ash, was determined using the differential method. The lowest carbon content was found in bentonite, amounting to slightly over 1%. In the elemental composition of bentonite, compared to other sorbents, the presence of sulfur was identified at a level of approximately 4%. The high oxygen and ash content (58.34% and 33.15%, respectively) in bentonite is characteristic of this type of material28. The high carbon content in coffee (50.48%) and hazelnut shells (46.66%) is related to their structure and significant content of organic compounds, such as cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, polysaccharides, which is confirmed by other studies29,30. Similarly, in the case of chitosan, which is a derivative of chitin, consisting of β-(1- > 4) – D-glucosamine molecules,– the carbon content is 44.37%, hydrogen 13.43%, nitrogen 8.08%, and oxygen 33.59%15,31. Compost is characterized by high oxygen and carbon content (45.79% and 27.57%, respectively) and hydrogen and nitrogen content below 5%. Considering the ash content determined in the compost, it can be stated that this sorbent contains a significant amount of organic matter32.

A crucial factor influencing the rate and efficiency of adsorption is pH, which affects the nature of the adsorbent surface. It also affects the degree of ionization and speciation of metal ions in the solution (Kołodyńska et al., 2012). According to accepted assumptions, if the solution pH is lower than pHzpc, the adsorbent surface will be positively charged, while if the solution pH is higher than pHzpc, the surface will be negatively charged (Pennanen et al., 2020). The analyzed sorbents differ in their pHpzc value (Table 1). Natural sorbents, i.e., coffee, compost and hazelnut shells, show a pHzpc value in the range of 6–7, while chitosan above 8. For bentonite, its pHzpc was determined to be below 4.

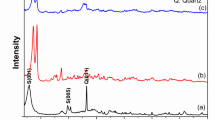

Structural properties

The porosity of the materials and the determination of their specific surface area were assessed based on N2 adsorption isotherms (77 K). The IUPAC classification was used to determine the type of isotherm (Fig. 1a.)., a. Bentonite samples exhibit a type IVa isotherm with visible H2 hysteresis, characteristic of adsorbents with narrow conical and cylindrical mesopores, which are closed at the conical end. Sorbents such as chitosan, compost, and hazelnut shells exhibit a type V isotherm, very similar to the type III isotherm, which can be attributed to relatively weak adsorbent-adsorbate interactions. Only at a higher p/p0 ratio does pore filling occur after molecular aggregation. For coffee, a type VI isotherm was obtained, representative of layer-by-layer adsorption on a very uniform, non-porous surface. All sorbents used are characterized by a predominance of mesopores in the range from 3 to 50 nm (Fig. 1b).

Table 2 presents a summary of the basic parameters, i.e., specific surface area (SBET), pore size (Dm), and pore capacity (Vt) for all five sorbents. For four of the five analyzed sorbents, the specific surface area value and pore distribution were determined. The highest specific surface area was obtained for bentonite (40.04 m2/g), which was characterized by a mesoporous structure with an average pore size of 3.427 nm and a capacity of 0.072 cm3/g. For coffee, the exact specific surface area could not be identified, as the obtained isotherms indicated a surface area below the detection limit of the apparatus.

Analysis of the literature indicates a variety of bentonite surface sizes, depending on the place of origin, and chemical composition. Materials with a surface area ranging from 30.35 to even 869 m2/g can be found using appropriate activation methods, with different porous structures and pore capacities33,34,35. For chitosan, the specific surface area was determined at the level of 12.27 m2/g, which, similarly to bentonite, was characterized by a predominance of mesopores with an average size of 3.848 nm and a capacity of 0.015 cm3/g. The obtained results of the analyses are confirmed by the other researchers, where the specific surface area was obtained in the range of 1.16 to 74.6 m2/g with a predominance of mesopores with a small capacity36. Hazelnut shells were characterized by a specific surface area of 11.05 m2/g, a mesoporous structure with an average pore size of 3.066 nm, and a capacity of 0.044 cm3/g. For compost, the specific surface area was determined at the level of 3.93 m2/g with larger mesopores than in the other sorbents, with an average pore size of over 4 nm and a capacity of 0.007 cm3/g. The obtained SBET surface area values and the distribution and pore capacity, both for hazelnut shells and compost, are comparable to the literature data37,38.

The adsorbents used in the study were characterized in terms of the presence of functional groups using FTIR spectroscopy (Fig. 2). For all the analyzed sorbents, the occurrence of peaks of stretching vibrations of –OH groups originating from inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bonds of polymer compounds and water in the range of 3200–3700 cm-1 with different intensity was determined. The occurrence of these vibrations in such a wide range indicates the presence of both free and bound -OH groups39,40,41.

For coffee, bands originating from the vibrations of the bonded N–H group of N-monosubstituted amides, as well as polypeptides and proteins (3069 cm−1), were identified (Table 3)42. The bands appearing at wavelengths of 2921 and 1737 cm−1 are derived from the stretching vibrations of the carbonyl group C = O and the asymmetric C–H stretching vibrations originating from the -CH2 group of lipid compounds43. Peaks attributed to caffeine were observed at 2856 and 1648 cm−1, corresponding to the vibrations of the C = O group and the deformation vibrations of -NH and C-N occurring in primary amides44,45. Bands associated with chlorogenic acid, formed as a result of esterification between quinic acid and caffeic acid, were visible at wavelengths in the range of 1154–1450 cm-1 and are related to the C-H deformation plane vibrations in the -C = C-H group42. The intense broad band at 1021 cm-1 and the band at 875 cm-1 are associated with the secondary and primary bonds of C = O, C–O–C, R-O-R, and R-OH groups present in polysaccharides and hemicellulose complex42.

The peaks corresponding to the vibrations of the methyl and methyl groups occurring in polysaccharides visible in the chitosan spectrum are observed at wavelengths of 2923 and 2864 cm-1 (Table 3)40. The peaks at 1645 and 1315 cm-1 correspond to the stretching vibrations of C = O and C-N, occurring in amides and OH groups from phenolic derivatives46,41. The peaks originating from the bending vibrations of the N–H bonds of the primary amine were located at 1585 cm-1. Additionally, the presence of C-H bonds resulting from the symmetric deformations of the CH2 and CH3 groups (1422 and 1372 cm-1) was identified47 and the stretching vibrations of the C-O bond of the C–O–C group (1146, 1061, and 1024 cm-1) were determined48.

Analysis of FTIR spectra for bentonite allows us the identification of characteristic bands for this type of material. The peaks appearing at wavelengths of 3447, 1631, 793, and 662 cm-1 are caused by vibrations of Si–O, Al-O, and Ca bonds33. The occurrence of these peaks indicates the presence of amorphous silica, and their appearance is due to the stretching and bending vibrations of the tetrahedra of SiO42-49. A very strong band in the region of 1100–1000 cm-1 is related to the vibrations of the Si–O bond33. The bands originating from the bending vibrations of the Al -Al -OH bonds were identified at a wavelength of 916 cm-150.

For compost, several bands were identified, indicating the diversity of possible functional groups. In addition to the peak’s characteristic of water, the band at a 3284 cm-1 indicates the occurrence of stretching vibrations from the bound N–H group of amides, present in N-monosubstituted amides, polypeptides, and proteins51. The presence of nitrogen compounds is also evidenced by the bands appearing in the range of 1610–1590 cm-1 and 809 and 713 cm-1 (amide band III from tertiary amides) (Baes and Bloom,1989,52,53. The peaks at 2963 and 2895 cm-1 are due to symmetric and asymmetric C-H stretching vibrations in the methyl and methylene groups51. The C = O stretching vibrations originating from the COOH group of carboxylic acids, ketones, aldehydes, and esters were identified at a wavelength of 1705 cm-154. A broad and intense band centered at 1027 cm-1 indicates the presence of polysaccharides and clay minerals (Si–O bond vibrations)55,56.

Analysis of the FTIR spectrum of the hazelnut shells sorbent indicates the presence of methylene group, confirmed by the band caused by vibrations of the C-H bond at 2879 cm-157. The vibrations of the C = O group of acetylene and esters in hemicellulose, and the ester bond of the -COOH group of hydroxycinnamic acid linking lignin to hemicellulose, were identified at a wavelength of 1728 cm-1. The stretching vibrations of C = O and C = C from the aromatic skeleton of hemicellulose and lignin were located at 1610, 1505 and 1450 cm-158,59,60. The peak at 1370 cm-1 is caused by the bending vibrations of the C-H bond in the plane of the methoxy groups of lignin37. The vibrations of the -C = O, C–O–C, and -O–H groups originating from esters, carboxylic acids, phenols, and their derivatives, were identified at 1239 and 1146 cm-159. The secondary and primary bonds characteristic of lignin, hemicellulose, and polysaccharides (-C = O, C–O–C, R-O-R, R-O–H) are evidenced by a broad band centered at 1034 cm-161. At a wavelength of 890 cm-1, stretching vibrations from the glycosidic bond of C–O–C appear57.

Characterization of the physicochemical and structural properties of sorbents of waste and natural origin showed significant differences that may affect the sorption properties of heavy metals. Analysis of the elemental composition and pHpzc values of the tested sorbents indicated differences resulting from their origin and chemical structure. Organic sorbents, i.e., coffee grounds, hazelnut shell, compost, and chitosan, are characterized by significant carbon and oxygen content, reflecting the presence of lignocellulosic fractions and other polysaccharides. Furthermore, these sorbents are rich in oxygen functional groups (-OH, -COO, -CO) and nitrogen (-NH2), which may significantly impact heavy metal binding efficiency despite their low specific surface areas. Bentonite, as an inorganic sorbent, contains a significant mineral fraction and is characterized by a low pHpzc, which in turn may negatively impact adsorption efficiency despite its high surface area.

Heavy metals removal

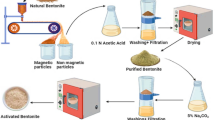

Adsorption processes are among of the most effective methods of removing pollutants from aqueous solutions; however, the high cost of producing adsorbents limits their use62. Recently, new sorbents in the form of so-called biosorbents have been sought. Various materials, such as fish scales, animal waste, plant waste, zeolites, clay, and bentonite with their modifications (e.g., thermochemical or magnetic), are analyzed in the context of the ability to sorb of various pollutants, including primarily heavy metals63,64,65.

All tested sorbents in our research demonstrated high efficiency in the removal of heavy metals from aqueous solutions. This trend was consistent across all types of sorbents used and for all analyzed metals. However, there was significant variation in the effectiveness of sorbents as well as in the removal efficiency of individual metals. Increasing the sorbent dosage significantly enhanced metal removal, reducing metal concentrations in residual aqueous phase to below the detection limit. Only when the lowest sorbent doses were applied did trace amounts of metals remain in the solution. These results indicate that sorbent dosage is a critical factor influencing the effectiveness of metal removal. Figure 3 shows the efficiency of various adsorbents in removing heavy metals.

The effectiveness of Zn removal, using all sorbents, except bentonite, was very high and similar. Even at the smallest dose, more than 90% reduction was achieved, while the fastest complete removal (at 0.5 g) was observed for hazelnut shells and coffee. Bentonite showed considerably lower performance. At the lowest dose, only 61% of zinc was removed, but efficiency improved with increasing sorbent amounts. Ultimately, a dose of 5 g enabled complete removal of the metal from the solution. The Cu removal efficiency was the highest among all tested metals (Fig. 3). In the case of all sorbents, except bentonite, even the minimum dose caused practically 100% removal. The most effective was chitosan, even the smallest dose caused complete elimination of Cu, and coffee and hazelnuts allowed for the removal of 99% of the metal. Bentonite was characterized by low removal efficiency, even lower than for Zn, amounting to 37%. Increasing the sorbent dose increased the removal efficiency. The largest 5 g dose allowed for complete removal of Cu.

The behavior of cadmium during the sorption process was different than in the case of the rest of the metals. Most sorbents at the smallest dose (0.1 g) allowed to remove 50–60% of the metals, except for the most effective hazelnuts, which removed 72%. Increasing the sorbent doses allowed for more effective removal. Finally, regardless of the sorbent, 3 g allowed to remove all cadmium each time.

In the case of lead, all sorbents allowed for similar metal removal efficiency. Even the smallest dose allowed for removal of over 95% of the metal each time, and increasing the dose allowed for increased removal efficiency.

Increasing the adsorbent dose increased the efficiency of sorption of the analyzed heavy metals. The higher the adsorbent dose, the greater the number of active binding sites for metals. In the study by66, bentonite was used for sorption of divalent ions (nickel and manganese) and the effect of the adsorbent dose on the efficiency of the process was determined. The researchers found that the level of metal removal increased with the increase in the bentonite dose. A similar observation was made by Bellache et al.67, who found that in the case of bentonite, increasing the dose caused an increase in the level of sorption of Zn(II) ions, due to the increase in the number of active sites, thus facilitating the penetration of metal ions into the sorption sites. In another study68, it was found that increasing the dose of biosorbent in the form of biochar from pig and cow manure caused an immediate increase in the sorption of Cu(II) ions.

The low capacity of bentonite, despite the largest specific surface area among the tested biosorbents and the presence of functional groups, may also result from the way the sorption process proceeds. For example, in the studies by Sen and Gomez69, it was found that the adsorption of Zn(II) ions on bentonite is a two-stage process: first of all a very fast adsorption of the metallic zinc ion on the external surface take placed, and then the process slows down and can occur by intramolecular diffusion inside the adsorbent, which was confirmed by the intramolecular diffusion model. In the case of the remaining ions (Cu, Cd, Pb) analyzed in this study, it was also observed that an increase in the adsorbent dose, regardless of its type, increases the efficiency of the sorption process. The calculated Pearson correlation coefficients (analysis performed using the function available in MS Excel) indicated that the correlation between the adsorbent mass and the adsorption of heavy metal ions is positively significant, especially in the case of compost (Pb p = 0.88, Zn p = 0.76, Cu p = 0.56, Cd p = 0.55), then bentonite (Cu p = 0.85,Zn p = 0.83; Pb p = 0.83, Cd p = 0.67), chitosan (Pb p = 0.85, Zn p = 0.71, Cd p = 0.58, Cu p = 0), coffee waste (Cu p = 0.84, Pb p = 0.83, Cd p = 0.71, Zn p = 0.51) and hazelnut shells (Pb p = 0.77, Cd p = 0.76, Zn p = 0.45, Cu p = 0.38). Analysis of the p -values also allows us to conclude that the mass of the adsorbent is significant primarily in relation to the type of metal being retained. For example, the mass of chitosan has no significant effect on the binding of Cu ions (p = 0), while the binding of the same ions by bentonite is determined by the mass of the adsorbent used (p = 0.85).

In the conducted experiment, the sorption efficiency series according to the sorbent used is as follows: hazelnut shells > chitosan > compost > coffee > bentonite. Organic sorbents showed a greater adsorption capacity of the analyzed ions than bentonite. This can probably be attributed to a greater share of oxygen functional groups in these materials. All analyzed sorbents, except bentonite, are characterized by the presence of groups such as C = O, COO-, C–O–C, O–H, N–H2. Many studies by other authors have confirmed that organic sorbents in the form of coffee husk, hazel nut shell, chitosan are characterized by high adsorption capacity of heavy metals, i.e. Pb, Cd, Cu or Zn due to diverse negatively charged functional groups70,71,72,73. In the study by Xiao and Huang74, the ability of organic sorbents (camellia leaves, pine sawdust, primary sludge from a municipal sewage treatment plant) and inorganic sorbents (Na-montmorillonite, goethite powders and fly ash) on the sorption capacity of Cu(II) ions was compared. Furthermore, the effective removal of Cu by chitosan is likely due to the presence of numerous amine groups, which are easily protonated and can form strong coordination bonds with metal ions75. The waste sorbents (coffee, shells, compost) act more like physicochemical sorbents with a limited number of weaker active sites, therefore their effectiveness towards Cu ions is much lower15,25,76. Other research has shown that the presence of functional groups derived from cellulose and proteins contained in plant cells contributes to the increase in the sorption capacity of organic sorbents in relation to inorganic sorbents. The presence of carboxyl, phenolic or amine groups on the surfaces of sorbents supports the binding of metal ions, especially those that have a greater affinity for a given functional group. In the case of organic sorbents rich in the above-mentioned functional groups, the sorption process usually has the character of cation exchange or the formation of relatively stable and durable complexes77,78.

For comparative purposes, a series of metal affinities for the surfaces of organic and inorganic sorbents for the lowest dose used (Table 4) was presented. Sorbents such as hazelnut shell, coffee and compost have the strongest affinity for copper, then lead, zinc and cadmium. In the case of bentonite, the series of sorbent surface affinities for the retained metal is different and is as follows: the strongest for lead, then zinc, cadmium, and copper. Such a course of the sorption process can probably be attributed to stronger interactions of carboxyl, amine, or phenolic groups. The sorption of copper ions, which are prone to form strong bonds with electron pair donor groups, resulting in complex formation, is distinctive in this case79. In addition, the copper ion is smaller than, for example, the zinc ion, which can also have a more beneficial effect on the retention efficiency80.

Adsorption of heavy metals on the surface of the analyzed natural sorbents was much more effective than natural ones (chitosan and bentonite). A significant parameter that influences sorption efficiency is the pH of the solution containing heavy metals. Lower ion sorption efficiency is also observed at lower pH values of the solutions in which they are present. This is due to the predominance of H+ ions, which in turn compete with positively charged metal ions for available binding sites on the adsorbent surface81. Metals such as Zn, Cu, Cd and Pb dissolve at low pH, while at high pH they form hydroxides and begin to precipitate. Precipitation of Cu occurs at pH > 6, Pb at pH > 9.6, and Zn and Cd at pH > 982,83,84. As shown earlier, when the pH of the ion solution is higher than the pHpzc of the sorbent surface, its surface is negatively charged, and therefore, the cation adsorption process should occur faster via ion exchange. Figure 4 shows the pH value for each sorbent used after sorption of individual ions. Adsorption on bentonite, despite the lower pHpzc (3.74) than the pH of the metal ion solution, is much less effective than the other analyzed sorbents. This is probably because that sorption on bentonites takes place in two stages, which has been shown, among others, in studies85,86. As can be observed (Fig. 4), for such sorbents as coffee, chitosan, compost and nuts, the ΔpH value (ΔpH = pHe—pHinit) determines that the sorption of metals on the surface of these adsorbents probably proceeded based on ion exchange and complexation87,88.

Economical aspects

Using waste materials as sorbents contributes to the implementation of circular economy principles by valorizing waste streams generated by industry and agriculture. Sorbents such as coffee grounds, hazelnut shells, or compost, which are the subject of this article, have a high potential for large-scale water treatment. This is both from an environmental and economic perspective. This stems from the fact that these waste materials are inexpensive (or even free), do not compete with food, and are widely available89. Large-scale implementation of waste-based sorbents requires extensive research, including long-term studies, to confirm their effectiveness. Mukherjee et al.24 conducted techno-economic analyses of using nutshells to produce activated carbon in three different scenarios. The authors estimated that processing 31.25 tons of nutshells per day could yield 6.6 tons of activated carbon, and annual production could represent a net present value (NPV) of USD 2.8 billion with an internal rate of return of 21%. Furthermore, regardless of the chosen scenario, the price per kg of the resulting adsorbent from nutshells was lower than for activated carbon obtained traditionally24. However, the success of this project depends on the appropriate scale and stable raw material supplies.

Research conducted on the use of coffee grounds primarily involves analyses focused on the physicochemical properties of this raw material. As is well known, coffee beans are rich in various compounds with antioxidants and anti-inflammatory properties and can be a rich source of fiber in forage90. According to literature data, over 500 billion cups of coffee are consumed worldwide, and 1 ton of coffee produces approximately 650 kg of coffee grounds91. In a study by Silva et al.92, the economic viability of using biosorbents, including coffee grounds with commercially available zeolites, was analyzed to remove fluoxetine from water. The researchers found that commercial adsorbents were characterized by higher costs per gram of substance removed (up to €6.85/g) than coffee grounds (€0.16/g). These results demonstrate that waste alone, without prior mechanical or chemical treatment, can be an economically viable adsorbent on a large scale92.

This is also confirmed by the results presented in this paper, but also in other studies, that waste sorbents such as coffee grounds, hazelnut shells or compost can be effective adsorbents of heavy metals from water, without the need for additional heat treatment or the use of chemical agents. However, the transition from laboratory-scale feasibility to industrial applications is fraught with challenges, including the heterogeneity of waste feedstocks, supply chain logistics, pre-processing requirements (drying, grinding, chemical activation), and limited operational cost data. These challenges are significant, making it difficult to assess the feasibility of large-scale sorbent use93.

Conclusion

The consistent performance across different sorbents (bentonite, chitosan, hazelnut shells, coffee grounds, compost) suggests their broad applicability in treating water contaminated with heavy metals. The selected sorbents were thoroughly characterized, including elemental composition, identification of functional groups, determination of BET surface area, and pore distribution. It has been demonstrated that sorbents such as. Hazelnut shells, coffee grounds, compost or chitosan, exhibit a large diversity of functional groups, mainly including oxygen groups (COO, OH, CO). The study showed that waste-derived sorbents such as coffee grounds, hazelnut shells, and compost can effectively remove heavy metals (Zn, Pb, Cd, Cu) from aqueous solutions, often showing comparable or even superior performance to natural origin sorbents like chitosan and bentonite. The best sorption efficiency for three of the four analyzed metals was achieved by hazelnut shell, which, at a mass of 0.1 g, removed over 90% of Zn, Cu and Pb. Furthermore, this sorbent also removed over 70% of Cd for a mass of 0.1 g. Despite bentonite exhibiting the highest specific surface area, it was the least effective sorbent, while copper proved to be the most challenging metal to remove using this material (only 37% for 0.1 g mass of used sorbent). Bentonite showed the highest degree of metal removal from aqueous solutions only in relation to Pb (95%) at the lowest sorbent dose (0.1 g). The high removal efficiency of heavy metals highlights the potential of the tested materials for practical environmental remediation. Waste-derived sorbents, due to their availability, low cost, and effectiveness, represent a promising and sustainable solution for water purification and environmental protection.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mathew, S. et al. Green technology approach for heavy metal adsorption by agricultural and food industry solid wastes as bio-adsorbents: a review. J Food Sci Technol. 60(7), 1923–1932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-022-05486-1 (2023).

Raji, et al. Adsorption of heavy metals: Mechanisms, kinetics, and applications of various adsorbents in wastewater remediation—a review. Waste. 1(3), 775–805. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste1030046 (2023).

Singh, A. & Kostova, I. Health effects of heavy metal contaminants Vis-à-Vis microbial response in their bioremediation. Inorg. Chim. Acta 568, 122068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ica.2024.122068 (2024).

Balali-Mood, M. et al. Toxic mechanisms of five heavy metals: mercury, lead, chromium, cadmium, and arsenic. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 643972. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.643972 (2021).

Mitra, S. et al. Impact of heavy metals on the environment and human health: Novel therapeutic insights to counter the toxicity. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 34(3), 101865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.101865 (2022).

Alsulaili, A., Elsayed, K. & Refaie, A. Utilization of agriculture waste materials as sustainable adsorbents for heavy metal removal: A comprehensive review. J. Eng. Res. 12(4), 691–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jer.2023.09.018 (2023).

Aigbe, U. O. & Osibote, O. A. Carbon derived nanomaterials for the sorption of heavy metals from aqueous solution: A review. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 16, 100578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enmm.2021.100578 (2021).

Qasem, N. A. A. et al. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater: a comprehensive and critical review. Clean Water. 4, 36. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-021-00127-0 (2021).

Gahrouei, A. E. et al. From classic to cutting-edge solutions: A comprehensive review of materials and methods for heavy metal removal from water environments. Desalin. Water Treat. 319, 100446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dwt.2024.100446 (2024).

Wei, H. et al. Coagulation/flocculation in dewatering of sludge: A review. Water Res. 2018(143), 608–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2018.07.029 (2018).

Amusat, S. O. et al. Ball-milling synthesis of biochar and biochar–based nanocomposites and prospects for removal of emerging contaminants: A review. J. Water Process Eng 41, 101993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2021.101993 (2021).

Kumar, A. et al. A review on conventional and novel adsorbents to boost the sorption capacity of heavy metals: current status, challenges, and future outlook. Environ. Technol. Rev. 13(1), 521–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622515.2024.2377801 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Green adsorbents for environmental remediation: synthesis methods, Ecotoxicity, and reusability prospects. Processes. 12(6), 1195. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12061195 (2024).

Vakili, M. et al. Application of chitosan and its derivatives as adsorbents for dye removal from water and wastewater: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 113, 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.07.007 (2014).

Aranaz, I. et al. Chitosan: An overview of its properties and applications. Polymers 13, 3256. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13193256 (2021).

Bhattacharyya, K. G. & Gupta, S. S. Adsorption of a few heavy metals on natural and modified kaolinite and montmorillonite: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 140(2), 114–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cis.2007.12.008 (2008).

Kainth, S. et al. Green sorbents from agricultural wastes: A review of sustainable adsorption materials. Appl. Surf. Sci. 19, 100562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsadv.2023.100562 (2024).

Miretzky, P. & Cirelli, A. F. Cr(VI) and Cr(III) removal from aqueous solution by raw and modified lignocellulosic materials: a review. J. Hazard. Mater. 180, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.04.060 (2010).

Satyam, S. & Patra, S. Innovations and challenges in adsorption-based wastewater remediation: A comprehensive review. Heliyon 10(9), e29573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29573 (2024).

Vialkova, E. et al. Phytosorbents in Wastewater Treatment Technologies: Review. Water 16(18), 2626. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16182626 (2024).

Ali, K., Zeidan, H. & Amar, R. B. Evaluation of the use of agricultural waste materials as low-cost and ecofriendly sorbents to remove dyes from water: a review. Desalin. Water Treat. 302, 231–252. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2023.29725 (2023).

Ighalo, J. O. et al. Cost of adsorbent preparation and usage in wastewater treatment: A review. Cleaner Chem. Eng. 3, 100042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clce.2022.100042 (2022).

Khalil, A. K. A. et al. Fly ash as zero cost material for water treatment applications: A state of the art review. Sep. Purif. 354(5), 129104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.129104 (2025).

Mukherjee, et al. Techno – Economic analysis of activated carbon production from spent coffee grounds: Comparative evaluation of different production routes. Energy Conver. Manag. X. 14, 100218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecmx.2022.100218 (2022).

Peng, X. X. et al. Roles of humic substances redox activity on environmental remediation. J. Hazard. Mater. 435, 129070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129070 (2022).

Moukadiri, H. et al. Impact and toxicity of heavy metals on human health and latest trends in removal process from aquatic media. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 21, 3407–3444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-023-05275-z (2024).

Moreno-Castilla, C. et al. Changes in surface chemistry of activated carbons by wet oxidation. Carbon N. Y. 38, 1995–2001. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-6223(00)00048-8 (2000).

Elkhalifah, A. E. I. et al. Effects of exchanged ammonium cations on structure characteristics and CO2 adsorption capacities of bentonite clay. Appl. Clay Sci. 83–84, 391–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2013.07.016 (2013).

Gonçalves, M. et al. Micro mesoporous activated carbon from coffee husk as biomass waste for environmental applications. Waste Biomass. Valor. 4, 395–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-012-9163-1 (2013).

Li, Y. et al. Preparation and characterization of magnetic hazelnut shell adsorbents. Water, Air Soil Pollution. 235(5), 7096. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-024-07096-3 (2024).

Furlani, F. et al. Characterization of chitosan/hyaluronan complex coacervates assembled by varying polymers weight ratio and chitosan physical-chemical composition. Colloids Interf. 4, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids4010012 (2020).

Verma, D. K. et al. Soil physiochemical properties, stability, aggregate fractions, associated carbon and nitrogen ratio in tropical dry deciduous forest. J. Jilin Univ. 42, 5 (2023).

Zaitan, H. et al. A comparative study of the adsorption and desorption of o-xylene onto bentonite clay and alumina. J. Hazard. Mater. 153, 852–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.09.070 (2008).

Karimi, L. & Salem, A. Analysis of bentonite specific surface area by the kinetic model during activation process in presence of sodium carbonate. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 141(1–3), 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2010.10.031 (2011).

Widjaya, R. R. et al. Bentonite modification with pillarization method using metal stannum. AIP Conf. Proc. 1904, 020010. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5011867 (2017).

Benamer-Oudih, S. et al. Sorption behavior of chitosan nanoparticles for single and binary removal of cationic and anionic dyes from aqueous solution. Environ. Sci Pollut Res Int. 31(28), 39976–39993. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-27907-0 (2024).

Tang, R. et al. Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution using agricultural residue hazelnut shell: Equilibrium, kinetic, and thermodynamic studies. J. Chem. 155, 8404965. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8404965 (2017).

Sarti, O. et al. Assessing the effect of intensive agriculture and sandy soil properties on groundwater contamination by nitrate and potential improvement using olive pomace. Biomass Slag (OPBS). 9, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/c9010001 (2023).

Chou, W. L. et al. Investigation of indium ions removal from aqueous solutions using spent coffee grounds. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 7(16), 2445–2454. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJPS12.192 (2012).

Queiroz, M. F. et al. Sassaki and hugo alexandre oliveira rocha, does the use of chitosan contribute to oxalate kidney stone formation?. Mar. Drugs. 13, 141–158. https://doi.org/10.3390/md13010141 (2015).

Barszcz, W. et al. Impact of pyrolysis process conditions on the structure of biochar obtained from apple waste. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 10501. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61394-8 (2024).

Sahachairungrueng, W. et al. Assessing the levels of Robusta and Arabica in roasted ground coffee using NIR hyperspectral imaging and FTIR spectroscopy. Foods 11, 3122. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11193122 (2022).

Craig, A. P. et al. Application of elastic net and infrared spectroscopy in the discrimination between defective and non-defective roasted coffees. Talanta. 128, 393–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2014.05.001 (2014).

Wang, J. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy for Kona Coffee Authentication. J. Food Sci. 74, C385–C391. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01173.x (2009).

Reis, N. et al. Performance of diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy and chemometrics for detection of multiple adulterants in roasted and ground coffee. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 53, 395–401 (2013).

Melo-Silveira, R. F. et al. In vitro antioxidant, anticoagulant and antimicrobial activity and in inhibition of cancer cell proliferation by Xylan extracted from corn cobs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13, 409–426. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13010409 (2012).

Vino, A. B. Extraction, characterization and in vitro antioxidative potential of chitosan and sulfated chitosan from Cuttlebone of Sepia aculeata Orbigny. Asian. Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2, 334-S341. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60184-1 (2012).

Song, C. et al. Physicochemical properties and antioxidant activity of chitosan from the blowfly Chrysomya megacephala larvae. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 60, 347–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.05.039 (2013).

Farmer, V. C. The layer silicates. In The infrared spectra of minerals (ed. Farmer, V. C.) 331–363 (Mineralogical Society, 1974).

Madejova, J. et al. Infrared spectra of some Czech and Slovak smectites and their correlation with structural formulas Geologica Carpathica. Series Clays 1, 9–12 (1992).

Nuzzo, A. et al. Infrared spectra of soil organic matter under a primary vegetation sequence. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 7, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-019-0172-1 (2020).

Bellamy. LJ. 1975. The infrared spectra of complex molecules. London: Chapman & Hall; 1975. p. 1–433.

Niemeyer, J. et al. Characterization of humic acids. Composts, and peat by diffuse reflectance fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 56, 135–140. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1992.03615995005600010021x (1992).

Williams, DJI., Fleming, I. 1995 Spectroscopic methods in organic chemistry. London: McGraw-Hill; 1995. p. 28–62.

Günzler, H. & Böck, H. IR-Spektroskopie: eine Einführung (IR Spectroscopy: An Introduction) 403 (Verlag Chemie, 1990).

Smidt, E. et al. Characterization of waste organic matter by FTIR spectroscopy: application in waste science. Appl. Spectrosc. 56, 1170–1175. https://doi.org/10.1366/000370202760295412 (2002).

Enache, A. C. An eco-friendly modification of a hazelnut shell biosorbent for increased efficiency in wastewater treatment. Sustainability. 15, 2704. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032704 (2023).

Cao, J. S. et al. A new absorbent by modifying hazelnut shell for the removal of anionic dye: Kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Bioresour. Technol. 163, 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.04.046 (2014).

Tripathi, A. et al. Morphological and thermochemical changes upon autohydrolysis and microemulsion treatments of coir and empty fruit bunch residual biomass to isolate lignin-rich micro- and nanofibrillar cellulose. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 5, 2483–2492. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b01288 (2017).

Zheng, D., et al., 2019. Isolation and Characterization of Nanocellulose with a Novel Shape from Hazelnut (Juglans Regia L.) Shell Agricultural Waste. Polymers.11, 1130. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11071130.

Li, X. et al. Characterization and comparison of hazelnut shells-based activated carbons and their adsorptive properties. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2020, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263617420946524 (2020).

Osman, A. I. et al. Methods to prepare biosorbents and magnetic sorbents for water treatment: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 21, 2337–2398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-023-01603-4.n (2023).

Salleh, M. A. M. et al. Cationic and anionic dye adsorption by agricultural solid wastes: A comprehensive review. Desalination 280(1–3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2011.07.019 (2011).

Hosny, M. et al. Phytofabrication of bimetallic silver-copper/biochar nanocomposite for environmental and medical applications. J. Environ. Manag. 316, 115238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115238 (2022).

Tee, G. T. et al. Adsorption of pollutants in wastewater via biosorbents, nanoparticles and magnetic biosorbents: A review. Environ. Res. 212, 113248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.113248 (2022).

Akpomie, K. G. & Dawodu, F. A. Potential of a low-cost bentonite for heavy metal abstraction from binary component system. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 4(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjbas.2015.02.002 (2015).

Bellache, D. et al. Adsorption of Zn (II) ions from refinery wastewater by sulfuric acid-modified bentonite: Kinetic and isotherm studies. Nova Biotechnol. Et Chimica 21(2), e1267. https://doi.org/10.36547/nbc.1267 (2022).

Kolodynska, D. et al. Kinetic and adsorptive characterization of biochar in metal ions removal. J. Chem. Eng. 197, 295–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2012.05.025 (2012).

Sen, T. K. & Gomez, D. Adsorption of zinc (Zn2+) from aqueous solution on natural bentonite. Desalination 267, 286–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2010.09.041 (2011).

Quyen, T. et al. Biosorbent derived from coffee husk for efficient removal of toxic heavy metals from wastewater. Chemosphere 284, 131312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131312 (2021).

Dutta, A. et al. Adsorption of cadmium from aqueous solutions onto coffee grounds and wheat straw: Equilibrium and kinetic study. J. Environ. Eng. 142, C4015014. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EE.1943-7870.0001015 (2016).

Bulut, Y. & Tez, Z. Adsorption studies on ground shells of hazelnut and almond. J. Hazard. Mater. 149, 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.03.044 (2007).

Liu, S. et al. Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid–thiourea-modified magnetic chitosan for adsorption of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solutions. Carbohydr. Polym. 274, 118555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118555 (2021).

Xiao, F. & Huang, J. C. H. Comparison of biosorbents with inorganic sorbents for removing copper(II) from aqueous solutions. J. Environ. Manag. 90(10), 3105–3109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.05.018 (2009).

Wan Ngah, W. S. & Fatinathan, S. Adsorption characterization of Pb(II) and Cu(II) ions onto chitosan-tripolyphosphate beads: Kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies. J. Environ. Manage. 91(4), 958–969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.12.003 (2010).

Davila-Guzman, N. E. et al. Studies of adsorption of heavy metals onto spent coffee ground: equilibrium, regeneration, and dynamic performance in a fixed-bed column. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 413879. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9413879 (2016).

Leng, L. et al. Nitrogen containing functional groups of biochar: An overview. Bioresour. Technol. 298, 122286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122286 (2020).

Yang, X. et al. Surface functional groups of carbon-based adsorbents and their roles in the removal of heavy metals from aqueous solutions: A critical review. Chem. Eng. J. 366, 608–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.02.119 (2019).

Bejan, A. & Marin, L. Outstanding sorption of copper (II) ions on porous phenothiazine-imine-chitosan materials. Gels. 9, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels9020134 (2023).

Selim, K. A. et al. Kinetics and thermodynamics of some heavy metals removal from industrial effluents through electro-flotation process. Colloid Surf. Sci. 2(2), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.css.20170202.11 (2017).

Amusat, S. O. et al. Facile solvent-free modified biochar for removal of mixed steroid hormones and heavy metals: isotherm and kinetic studies. BMC Chemistry 17, 158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13065-023-01071-5 (2023).

Karimi, H. Effect of pH and initial Pb(II) concentration on the lead removal efficiency from industrial wastewater using Ca(OH)2. Int. J. Water Wastewater Treat. 3, 139. https://doi.org/10.16966/2381-5299.139 (2017).

Albrecht, TWJ., et.sl., 2011. Effect of pH, concentration and temperature on copper and zinc hydroxide formation/precipitation in solution, in: Chemeca 2011: Engineering a Better World: Sydney Hilton Hotel, NSW, Australia, 18–21 September 2011. Barton, A.C.T.: Engineers Australia, p. 2100–2110.

Charerntanyarak, L. Heavy metals removal by chemical coagulation and precipitation. Water Sci. Technol. 39, 135–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0273-1223(99)00304-2 (1999).

Visa, A. et al. New efficient adsorbent materials for the removal of Cd(II) from aqueous solutions. Nanomaterials 10, 899. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10050899 (2020).

Yous, R. et al. Simultaneous sorption of heavy metals on Algerian Bentonite: mechanism study. Water Sci. Technol. 84(12), 3676–3688. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2021.474 (2021).

Liu, Z. & Zhang, F. S. Removal of lead from water using biochars prepared from hydrothermal liquefaction of biomass. J. Hazard. Mater. 167, 933–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.01.085 (2009).

Chen, X. C. et al. Adsorption of copper and zinc by biochars produced from pyrolysis of hardwood and corn straw in aqueous solution. Bioresour. Technol. 102, 8877–8884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2011.06.078 (2011).

Gil-Gómez, J. A. et al. Valorization of coffee by-products in the industry, a vision towards circular economy. Discov Appl Sci 6, 480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-024-06085-9 (2024).

Lee, Y.-G. et al. Value-added products from coffee waste: A review. Molecules 28, 3562. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28083562 (2023).

Cobo-Ceacero, C. J. et al. Effect of the addition of organic wastes (cork powder, nutshell, coffee grounds and paper sludge) in clays to obtain expanded lightweight aggregates. Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. Vidr. 62, 88–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bsecv.2022.02.007 (2023).

Silva, B. et al. Waste-based biosorbents as cost-effective alternatives to commercial adsorbents for the retention of fluoxetine from water. Sep. Purif. Technol. 235, 116139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2019.116139 (2020).

Sidło, W. & Latosińska, J. Reuse of spent coffee grounds: alternative applications, challenges, and prospects—a review. Appl. Sci. 15, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15010137 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.W. - conceptualization, M.W. and J.B - methodology, W.B. and J.B. - carrying out research, W.B. and J.B - validation, W.B. and J.B. - wrote the main manuscript text, W.B. prepared all figures and tabbles. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wojtkowska, M., Barszcz, W. & Bogacki, J. Comparative study of Waste-Derived and conventional sorbents for heavy metal removal from water. Sci Rep 15, 45188 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29040-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29040-z