Abstract

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) for AKI patients using a flexible catheter and cycler was started in 2004 in Botucatu, São Paulo, Brazil. This study aimed to describe the main determinants of patient and technique survival, including PD treatment trends in AKI patients over time. This was a large Brazilian retrospective cohort study in which adult AKI patients with PD were studied from January/2004 to January/2024. For comparison purposes, patients were divided into two groups according to the year of treatment: 2004–2014 and 2015–2024. We included 487 patients. The mean age was 64.02 ± 15.01 years and 327 (67.1%) patients were male. Most patients needed vasoactive drugs and mechanical ventilation (66.1% and 73.1%, respectively). The mean ATN-index specific score (ISS) was 0.61 ± 0.2, and the median APACHE-II score was 27 (20–31). Sepsis was the primary diagnosis (33.7%), followed by cardiovascular etiologies (29.2%). Uremia or azotemia was the main indication for dialysis (46.4%). The delivered urea Kt/V was 0.55 ± 0.18/session and 3.22 ± 0.6/week. Over the years, the prevalence of catabolism increased from 7.6 to 26.5% (p < 0.0001), and PD has been used more in patients with liver cirrhosis (from 5.3 to 14.1%, p < 0.0001) and with nephrotoxic AKI (from 0 to 5.9%, p < 0.0001), and less in septic patients (40.1 vs. 23.2%). The groups were similar in terms of APACHE2. The indication for dialysis due to azotemia/uremia decreased from 64.9% to 16.2% (p < 0.0001) and increased by metabolic and fluid demand to capacity imbalance (from 4 to 68.1%, p < 0.0001). The prescribed dialysis PD dose decreased from 0.56 ± 0.09 to 0.44 ± 0.08 (p < 0.001), and there was no difference in metabolic and volume control. There was an increase in kidney function recovery from 24.8 to 35.7% (p < 0.0001) and a reduction in mortality over 30 days from 59.9% to 49.2% (p 0.02) and in technical failure (TF) from 15.6% to 5.9% (p < 0.0001). The main cause of TF was mechanical complication followed by peritonitis. Cox regression identified the period 2004–2014 as a risk factor for death and technique failure (OR 2.4, 95%CI 1.16–4.93, p = 0.018, and OR 12.58, 95%CI 2.74–57.69, p = 0.001, respectively). In the second period, PD was indicated earlier and prescribed at a lower dose, with no difference in the patient’s metabolic and volume control. There was an improvement in patient survival and technique over the years, suggesting better indication and management of this therapy. This is the largest cohort in the world to provide patient characteristics, clinical practice, and its relationship with clinical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a clinical syndrome associated with high mortality in critically ill patients. Peritoneal dialysis (PD) was the acute kidney replacement therapy (AKRT) modality widely used until the 1980s1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. It is one of the mainstays of treatment for pediatric AKI and a modality commonly used in low- and middle-income countries, but there has been a decline in its use to the detriment of hemodialysis in intensive care settings in developed countries due to advances in continuous renal replacement therapies (CRRT)10,11,12,13.

The studies performed by Ponce-Gabriel et al.14,15 showed that, with careful thought and planning, critically ill patients could be successfully treated by PD. To overcome some of the classic limitations of PD use in AKI, such as a high chance of infectious and mechanical complications and no metabolic control, they proposed the use of cycles, flexible catheter, and a high volume of PD.

The International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis has published updated guidelines for treating PD in AKI, stating that PD is an acceptable form of AKRT in patients with AKI16. Although PD is not inferior to extracorporeal modalities in terms of metabolic control and survival in AKI, as shown in recent meta-analyses and ISPD guidelines, it may not be the preferred method in certain clinical scenarios, such as in patients with severe hypercatabolism, recent cardiovascular surgery, or life-threatening conditions requiring rapid solute and fluid removal. In such cases, extracorporeal therapies may provide faster and more predictable control17,18.

A recent resurgence of interest in the use of PD to treat AKI in high-income countries has been related to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic due to the critical shortage of resources and personnel needed to provide hemodialysis (HD) and CRRT19.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, high-income countries were confronted with a sudden surge in the number of patients with severe AKI, putting tremendous strain on the healthcare system20. Many countries faced acute shortages of ICU beds, CRRT machines, and trained ICU staff. Some centers successfully developed acute PD programs, which proved to be lifesaving, and highlighted the need to review the current practices of managing AKI in critically ill patients, particularly in developed countries. The UK and the USA have published studies that have shown good results21,22,23,24,25,26.

Large cohorts provide a potential advantage for analyzing large longitudinal cohort studies, which provides an overview of trends in patient and treatment characteristics. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to describe the changing epidemiology and prescription and their relationship to the clinical outcomes of acute kidney injury patients treated by PD in a large Brazilian cohort. In addition, we aimed to analyze temporal trends in technique survival and outcome of AKI patients treated with PD.

Methods

Study population

This study was a prospective cohort study approved by the ethics committee of the Botucatu School of Medicine, Sao Paulo, Brazil, and the researchers adhered to the confidentiality of patients’ data and the recommendations in the Declaration of Helsinki throughout the study. Data collection was prospective and protocol-driven, although the current analysis was conducted retrospectively. A standardized protocol for patient inclusion, treatment, and follow-up using high-volume peritoneal dialysis (HVPD) in AKI was established in our institution in 2004, and has been systematically applied since then. All patients were enrolled consecutively and followed prospectively according to predefined clinical, laboratory, and outcome variables. Data collection was prospective and protocol-driven. Patients who had been treated for high-volume HVPD between January 2004 and January 2024, consecutively, were included. Informed consent was obtained from study participants or their legal caregivers.

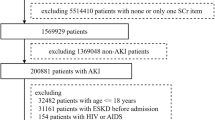

The inclusion criteria were AKI patients according to KDIGO 2012 criteria27 and the clinical diagnosis of AKI caused by ischemic, septic, and/or nephrotoxic injury. Indications for dialysis were uremia or azotemia [Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) > 100 mg/dL], fluid overload (after diuretics use), electrolyte imbalance (K + 6.5 mEq/L after clinical treatment), acid–base disturbances (pH 7.1 and bicarbonate 10 mEq/L after clinical treatment), and metabolic and fluid demand to capacity imbalance as defined by Macedo et al. in 2011 and revised by Ostermann et al. in 201628,29.

Patients who had chronic kidney disease (CKD) stages 4 and 5 based on CKD-EPI, kidney transplants or were under treatment with one of the renal replacement therapy (RRT) methods, pregnancy, and those younger than 18 years old were excluded from the study. In addition, functional azotemia (by clinical definition, the integrity of renal parenchyma tissue was maintained, and glomerular filtration rate was corrected rapidly, in less than 24 h on restoration of renal perfusion and glomerular ultrafiltration pressure, with normal urine sediment and fractional excretion of sodium < 1%), urinary tract obstruction, acute interstitial nephritis, and rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (clinical criteria, defined as, absence of criteria for acute tubular necrosis, relevant clinical history and blood test with granular casts in urine sediment: red and white blood cells cast, proteinuria, or eosinophiluria > 5%) were also excluded from the study.

Absolute contraindication for PD was defined as recent abdominal surgery (less than one month), multiple abdominal surgeries (more than three), life-threatening hyperkalemia, severe respiratory failure (Inspired Oxygen Fraction > 70%), and severe fluid overload (pulmonary edema)11,12,13. If patients presented any one of these contraindications, they were treated by intermittent conventional, prolonged, or continuous HD according to their hemodynamic instability.

Study protocol

A HV PD session was performed continuously (24 h, 7 days/week) using Dianeal PD solution (Na = 135 mEq/L, Ca = 3.5 mEq/L, K = 0 mEql/L, Mg = 1.5 mEq/L, lactate = 40 mEq/L, 1.5%–4.25% glucose) and cycler (automated PD). Peritoneal access was established by the blind percutaneous placement of a flexible catheter using a Trocath-introduced paramedian from 2004 to 2008 and the Seldinger technique from 2009 to 2024. Vancomycin was used as a prophylactic antibiotic to cover the PD catheter insertion.

The prescribed high volume PD dose was determined by Kt/V28, where K is the volume of dialysis solution prescribed in 24 h (in liters) × 0.6 (considering the relationship of urea nitrogen (UN) dialysate/ plasma = 0.6 in 1 h), t is treatment duration (1 day), and V is the volume (in liters) of body urea distribution by the formula by Watson et al29. The prescribed Kt/V value ranged from 0.5 to 0.8/session (mean was 0.59 ± 0.11) from 2004 to 2014 and from 0.3 to 0.5/ session (mean was 0.42 ± 0.08) from 2015 until 2024; 1.5–2.5 L exchanges were performed (20–30 ml/kg) with 35–75 min of dwell time (total of 18–44 L/d and 10–22 exchanges/d).

To evaluate the dialysis adequacy, delivered Kt/V, ultrafiltration (UF), and fluid balance (FB) were calculated.

The delivered HVPD dose was determined by urea Kt/V, where K was the mean dialysate UN in milligrams per 100 ml/plasma UN pre- and post-dialysis in milligrams per 100 ml/drained volume in 24 h in milliliters/volume of body urea distribution in milliliters30. Blood samples were collected at the beginning and end of each high-volume PD dialysis session and analyzed for creatinine, potassium, bicarbonate, glucose, and sodium levels. One alíquota of 3 ml of all the spent dialysate was collected every three days to measure UN and calculate Kt/V. Dialysate white blood cell count and cultures were also determined every three days.

Before dialysis, anthropometric measurements (weight, height, and body surface area) were obtained. Body surface area was calculated from the Du Bois formula31. Mobile patients were weighed on a digital scale, and the weight of immobilized patients was obtained by a bed scale or calculated from two variables formula32.

Other variables, including the etiology of AKI, urine output, number of dialysis sessions, need for mechanical ventilation, presence of hemodynamic instability, prognostic index of AKI evaluated by Acute Tubular Necrosis Individual Severity Score (ATN-ISS)33, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation 2 (APACHE2) score, catabolism patients based on Schrier criteria34 and patient outcome were analyzed. The ATN-ISS is a linear discriminant model producing a percent likelihood of mortality based on demographic data, causes of ATN, urine output, need for dialysis, and clinical conditions.

The protocol was interrupted when there was a partial recovery in kidney function (urine output.above 1 ml/kg/day) and a progressive decrease in creatinine and BUN levels for 48 h without PD; the need to change the dialysis method because of infectious and mechanical complications, or inefficacy of PD in achieving metabolic and fluid control after 3 sessions; PD treatment for more than 30 days or death.

For the analysis of technique survival, the primary event was defined as transfer to HD for any reason, which means the patient did not return to PD until the end of the follow-up. Dropout data were stratified as death, recovery of renal function, and transfer to HD. For the description of trends in population characteristics, and patient and technique survival, the population was divided into two groups according to the year of PD treatment: 2004 to 2014 and 2015 to 2024.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and range according to normality characteristics for each variable with a 5% significance level; t-test was used to compare parametric variables between two groups, and ANOVA followed by the Newman–Keuls test for multiple comparisons between groups. For nonparametric variables, Wilcoxon and Kruskal–Wallis tests followed by Dunn’s method were used to compare two groups and multiple groups, respectively. For analysis of repeated measures, the Proc mixed program was used.

Categorical variables were expressed as proportions and compared with the chi-squared test. Variables with significant univariate associations were candidates for multivariable analysis. A multivariate analysis was conducted using logistic regression models, calculating Odds Ratios (OR). All independent variables associated with the outcomes with p ≤ 0.20, were included in the model.

Survival curves using Cox regression were performed for patients and technique survival, after adjusting for variables: age, prognostic scores, main diagnosis, mechanical ventilation, hemodynamic instability and peritonitis.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical descriptive analyses were performed with SPSS 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, USA).

Results

During the study period (20 years), a total of 2,880 patients were treated by dialysis: 487 by HVPD (16.9%) and 2,393 HD (83.1%), of which 1024 were treated by conventional (42.7%), 1,071 were treated by prolonged (44.8%), and 298 were treated by CRRT (12.5%).

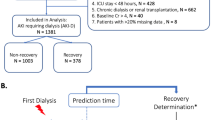

Figure 1 summarizes the main outcomes related to patients with AKI treated with PD.

In Table 1, we present the main characteristics of the general study population. The mean age was 64.02 ± 15.01 years, 327 (67.1%) patients were male, and the mean patient weight was 67.3 ± 12.9 kg.

Most patients needed vasoactive drugs and mechanical ventilation (66.1% and 73.1%, respectively). The mean ATN-index specific score (ISS) was 0.61 ± 0.20, and the APACHE2 score was 2720,31.

The main diagnosis was sepsis (33.7%), followed by cardiovascular etiology (29.2%), including patients with acute decompensated heart failure, cardiorenal syndrome, acute myocardial infarction, and ischemic cerebrovascular events associated with AKI. Uremia/azotemia was the main indication for dialysis (46.4%), and the Kt/V prescribed was 0.55 ± 0.18/session.

Patients characteristics

Table 1 also shows the characteristics of the study population divided into two different periods of PD treatment. In the first period, we evaluated 302 patients (62%); in the second period, we evaluated 185 patients (38%).

Over the years, the prevalence of hypercatabolic patients increased (7.6 vs. 26.5%, p < 0.001), and PD was used more in patients with liver cirrhosis (5.3 vs. 14.1%, p < 0.0001) and nephrotoxic ARF (0 vs. 5.9%, p < 0.001) and less in septic patients (40.1 vs. 23.2%). The groups were similar in terms of APACHE2. The indication for dialysis due to azotemia/uremia decreased (64.9 vs. 16.2%, p < 0.0001) and increased due to an imbalance between metabolic demand/fluids and renal capacity (4 vs. 68.1%, p < 0.001).

Prescription and achieved metabolic and fluid control

The median number of sessions was 5 3,4,5,6,7,8. The prescribed dialysis dose decreased (0.56 ± 0.09 vs 0.44 ± 0.08, p < 0.001), and there was no difference between the groups in metabolic/volumic control.

Table 2 shows the general metabolic control and fluid balance after high-volume PD initiation. BUN and creatinine levels stabilized after four sessions, and bicarbonate, pH, and potassium levels stabilized after three sessions. The mean UF increased steadily from one to three sessions and stabilized at around 2000 ml/d after four sessions.

The study population’s achieved metabolic control and fluid balance differed between two different periods of PD treatment, as shown in Table 2.

Technique survival

Table 3 summarizes the infectious and mechanical complications related to PD, and Table 4 shows the causes of dropout. Mechanical and infectious complications related to high volume peritoneal dialysis occurred in 77 patients, with peritonitis being the most prevalent (42.9%), followed by low ultrafiltration (35.1%) and leakage (19.5%). The dropout rate was 19.9%, with the most prevalent cause being catheter dysfunction (40.2%), followed by peritonitis (36.1%) and no fluid control (16.5%).

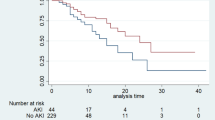

Over the periods, there was a reduction in technique failure, from 15.6 to 5.9% (p < 0.0001). After adjusting for variables, including catheter insertion technique, Cox regression found an odds ratio of 12.58 for technique failure for 2004–2014 compared to 2015–2024 (CI 2.74–57.68), as shown in the Fig. 2.

Technique survival of AKI patients treated with peritoneal dialysis according to treatment period (2004–2014 vs. 2015–2024), after adjusting for variables (age, prognostic scores, main diagnosis, peritonitis, catheter insertion technique). Numbers of patients at risk at each time point are shown below the plot.

Patient survival

Concerning patient outcome, 29% of patients recovered renal function, whereas 8.6% were on dialysis after 30 days of therapy. Change of the dialysis method occurred in 11.9% of patients because of refractory peritonitis or mechanical complications (leakage or UF failure). There were 272 deaths (55.9%) during the study.

Over the periods, there was a reduction in mortality, from 59.9% to 49.2% (p 0.02), and an increase in the prevalence of recovery of kidney function, from 24.8% to 35.7% (p < 0.0001). After adjusting for variables, Cox regression found an odds ratio of 2.39 for death for 2004–2014 compared to 2015–2024 (CI 1.16–4.93), as shown in the Fig. 3.

Discussion

PD for AKI therapy can provide several advantages over intermittent HD and extracorporeal CCRT. In addition to the technical simplicity that requires less infrastructure, PD is likely less costly and better tolerated than intermittent HD in hemodynamically unstable patients. During natural or human-made disasters, abrupt loss of infrastructure and resources may result in more rapid mobilization of PD as an AKI treatment than HD if expertise in PD delivery exists. PD is a simple, safe, and efficient way to correct metabolic, electrolytic, acid–base, and volume disturbances generated by AKI; it can be used as an AKRT modality to treat AKI, either in or out of the intensive care unit setting35,36.

The present study is the largest cohort of PD in AKI that showed improved AKI patient survival treated with PD and in its TF. The demographic characteristics of our PD patients changed over time. PD has been used more in cirrhotic patients, nephrotoxic AKI, and COVID-19, and less in the immediate postoperative period and in septic patients. The groups were similar in terms of APACHE2. Ponce et al.’s cohort37 evaluated 53 patients with chronic liver disease, with a mean age was 64.8 ± 13.4 years, model of end-stage liver disease (MELD) was 31 ± 6 and treated by PD (prescribed Kt/V = 0.40/session), with a flexible catheter, tidal modality, using a cycler and lactate as a buffer with adequate metabolic and volume control after four PD sessions. During the COVID-19 pandemic, some centers in developed countries have developed protocols for performing PD in patients with AKI20,21,22,23,24,25,26. Preliminary data from the IRA– Latin American Society of Nephrology and Hypertension registry of AKI in COVID-19 patients show that HD was used in 48.8% of cases, PIRRT was used in 25.1% of cases, CRRT was used in 18.3% of cases, and PD was used in 2.3% of cases38.

These changes in our patient profile likely reflect a change in clinical practice based on data pointing to worse outcomes of septic and severe hypercatabolic patients treated with PD. According to Chitalia et al.39, hemodialysis should be the first option of treatment for severe hypercatabolic septic patients because PD clearance is limited by dialysate flow, membrane permeability, and area and cannot be enough to keep adequate metabolic and fluid control of these patients.

The indication for dialysis due to azotemia/uremia decreased and increased due to an imbalance between metabolic demand/fluids and renal capacity. Brazilian cohort40 included 5428 AKI patients, 50.6% with maximum AKI stage 3, dialysis treatment was indicated in 928 patients (17.1%), and patient survival improved along the study periods, with a relative risk death reduction of 0.89 (95% CI 0.81–0.98, p = 0.02). The increase in metabolic and fluid demand to capacity imbalance as the main indication for dialysis raises the possibility that dialysis is increasingly being performed earlier, thereby reducing observed mortality rates. The concept of demand capacity balance in AKI was initially described by Macedo and Mehta41 and recommended in a consensus ADQI meeting42. The demand is determined by the severity of the acute illness and the solute and fluid burdens. The demand capacity balance is dynamic and varies with the course of critical illness. When renal capacity decreases and fails to cope with the demands, initiation of AKRT should be considered43.

PD dose adequacy in AKI is a subject of controversy, and a common cause of hesitancy amongst clinicians to use PD is based on the misconception that PD is unable to achieve the same clearance seen with extracorporeal therapies. There are many case series and randomized trials of PD in AKI that demonstrate rapid correction of hyperkalemia, acidosis, and fluid overload. There was a significant reduction in BUN and creatinine levels, with stabilization of BUN values (around 55 mg/dl) and bicarbonate (around 23 mEq/l) after four sessions in both study periods. Ponce et al.44 have compared prescribed Kt/V = 0.8 with Kt/V = 0.5 and have shown no benefit from aiming for the higher target; the lower-dose group achieved a Kt/V urea of 3.43 and did as well as the higher-dose group, which achieved a Kt/V of 4.13. However, some studies have shown excellent outcomes with much lower doses than those used in Ponce-Gabriel’s study39,46. Parapiboon et al.47 compared the intensive versus standard dose protocols using more than 30 L and less than 20 L of PD fluids, respectively. The delivered weekly Kt/V was 3.3 and 2.2 in intensive and standard-dose groups. Both groups were similar in baseline characteristics. There was no significant difference in 30-day in-hospital mortality, metabolic control, renal function recovery, and duration of PD between the two groups. Regarding PD doses, there was a decrease in prescribed and delivered Kt/V in the second period, without changes in metabolic control.

Mechanical and infectious PD complications are significant concerns. Peritonitis occurring in patients with AKI using PD as a modality of RRT can lead to very poor outcomes. Older studies have reported a frequency as high as 40%, but most recent studies have related peritonitis levels to be from 12 to 15%36. In our study, there was a reduction in the incidence of peritonitis. There was an increase in no metabolic and fluid control and catheter dysfunction. There is no data in the literature that is comparable to our study. There was a reduction in technical failure in the second period. The study period had an impact because the team gained more experience in catheter insertion with Seldinger technique, and cycler preparation. Starting in the second period (2015–2024), catheters were inserted exclusively by trained interventional nephrologists using the Seldinger technique, which improved catheter positioning and reduced early mechanical complications. Additionally, there was significant investment in training ICU nursing staff, who were initially supported by nephrology nurses specialized in peritoneal dialysis. Over time, ICU nurses became increasingly autonomous in managing the cycler, troubleshooting alarms, and monitoring ultrafiltration and catheter function. During the first sessions of PD or in case of complications, the nephrology team (physicians and PD nurses) provided bedside support, especially in the first 24–48 h. This structure ensured early detection and correction of technical issues, including inflow/outflow problems, leakage, and cloudy effluent.

There was greater dependence on dialysis within 30 days in the second period, in which the most frequent indication for dialysis was for demand versus renal capacity imbalance, i.e. earlier. This is corroborated by the findings of the STARRT-AKI clinical trial48, which assessed 2927 patients (1465 in the accelerated-strategy group and 1462 in the standard-strategy group) and found no difference in 90-day mortality. However, among survivors at 90 days, continued dependence on dialysis was most frequent in the accelerated strategy group (relative risk, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.24 to 2.43).

Despite improvements in intensive care and dialysis, some experts have concluded that mortality rates remain extremely high in dialysis AKI patients (1–3). Not surprisingly, death was responsible for more than 55.9% of the study dropout. In line with previous reports, the mortality of AKI patients undergoing different methods of dialysis ranged from 40 to 80%, according to AKI etiology and severity of patients. In this study, mortality rates decresead in the second period, probably related to an improving clinical practice, including better fluid. Another possibility is related to a better management of PD-related infections that medical societies have massively tackled through campaigns and the development and diffusion of clinical guidelines. Importantly, our results are in line with previous data in AKI patients from large cohorts that looked into secular trends: Waikar et al.49, in a large study with AKI patients in dialysis, reported a significant improvement ranging from 3 to 5% in 2 to 5 years patient survival.

This study presents several limitations. First, this is a retrospective observational study, so all significant associations found should be interpreted with caution. Second, residual renal function data were unavailable for most patients and not included in our analysis. Nevertheless, our study has some important strengths: it was a big cohort with outcomes adjusted for several clinical covariates and reflects 20 years of expertise of a teaching hospital in a developing country. Its characteristics share several similarities with other cohorts from different parts of the world, supporting the quality of our data.

Conclusion

We described the world’s largest PD cohort in AKI patients, that provided patient characteristics, clinical practice and its relationship with clinical outcomes. In the second period, PD was indicated earlier and prescribed at a lower dose, with no difference in the patients’ metabolic and volume control. There was an improvement in patient survival and in the technique over the years, which suggests better indication and management of this therapy.

PD is a reliable and effective AKRT for selected patients with AKI, particularly in the following clinical scenarios: cirrhosis or advanced liver disease, in whom extracorporeal methods may worsen hemodynamic instability or coagulopathy; patients with nephrotoxic AKI or drug-induced renal injury, who are often hemodynamically stable and respond well to PD; cardiorrenal syndrome, with volume overload or metabolic disturbances without life-threatening emergencies; settings of limited resources, such as during pandemics, disasters, or in low- and middle-income countries, where extracorporeal therapies may not be promptly available. On the other hand, PD may be less suitable for patients with: septic shock and severe hypercatabolism; recent major abdominal surgery, adhesions, or peritoneal membrane dysfunction; critical life-threatening emergencies requiring rapid solute clearance (e.g., severe acidosis, hyperkalemia with ECG changes).

In summary, our findings support the notion that PD is a dependable modality of AKRT when appropriately indicated and managed, and should be part of the therapeutic arsenal in both high- and low-resource settings.

Data availability

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the privacy of individuals who participated in the study. The data will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Uchino, S. et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: A multinational, multicenter study. JAMA 294(7), 813–818. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.7.813 (2005).

Andonovic, M. et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of intensive care patients with acute kidney disease. EClinicalMedicine 44, 101291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101291 (2022).

Melo, Fd. A. F. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of acute kidney injury in the intensive care units of developed and developing countries. PLoS ONE 15(1), e0226325. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226325 (2020).

Strijack, B. et al. Outcomes of chronic dialysis patients admitted to the intensive care unit. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20(11), 2441–2447. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2009040366 (2009).

Manhes, G. et al. Clinical features and outcome of chronic dialysis patients admitted to an intensive care unit. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 20(6), 1127–1133. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfh762 (2005).

Rao, P., Passadakis, P. & Oreopoulos, D. G. Peritoneal dialysis in acute renal failure. Perit. Dial. Int. 23(4), 320–322 (2003).

Gabriel, D. P. et al. Peritoneal dialysis in acute renal failure. Ren. Fail. 28(6), 451–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/08860220600781245 (2006).

Gaião, S. et al. Acute kidney injury: Are we biased against peritoneal dialysis?. Perit. Dialysis Int. 32, 351–355. https://doi.org/10.3747/pdi.2010.00227 (2012).

Nkoy, A. B. et al. A promising pediatric peritoneal dialysis experience in a resource-limited setting with the support of saving young lives program. Perit. Dial. Int. 40, 504–508. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896860819887286 (2020).

Ansari, N. Peritoneal dialysis in renal replacement therapy for patients with acute kidney injury. Int. J. Nephrol. 2011, 739794. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/739794 (2011).

Cullis, B. Peritoneal dialysis for acute kidney injury: back on the front-line. Clin. Kidney J. 16(2), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfac201 (2022).

Khan, S. F. Peritoneal dialysis as a renal replacement therapy modality for patients with acute kidney injury. J. Clin. Med. 11(12), 3270. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11123270 (2022).

Ponce, D., Balbi, A. & Cullis, B. Acute PD: Evidence, guidelines, and controversies. Semin. Nephrol. 37(1), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2016.10.011 (2017).

Gabriel, D. P. et al. High volume peritoneal dialysis for acute renal failure. Perit. Dial. Int. 27(3), 277–282 (2007).

Ponce, D., Berbel, M. N., Regina de Goes, C., Almeida, C. T. P. & Balbi, A. L. High-volume peritoneal dialysis in acute kidney injury: Indications and limitations. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 7(6), 887–894. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.11131111 (2012).

Cullis, B. et al. ISPD guidelines for peritoneal dialysis in acute kidney injury: 2020 update (adults). Perit. Dial. Int. 41(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896860820970834 (2021).

Liu, L., Zhang, L., Liu, G. J. & Fu, P. Peritoneal dialysis for acute kidney injury. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 12(12), CD011457. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011457.pub2 (2017).

Chionh, C. Y., Soni, S. S., Finkelstein, F. O., Ronco, C. & Cruz, D. N. Use of peritoneal dialysis in AKI: A systematic review. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 8(10), 1649–1660. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.01540213 (2013).

Goldfarb, D. S. et al. Impending shortages of kidney replacement therapy for COVID-19 patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 15(6), 880–882. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.05180420 (2020).

Chen, W. et al. Use of peritoneal dialysis for acute kidney injury during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City: A multicenter observational study. Kidney Int. 100, 2–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2021.04.017 (2021).

Al-Hwiesh, A. K. et al. Successfully treating three patients with acute kidney injury secondary to COVID-19 by peritoneal dialysis: Case report and literature review. Perit. Dial. Int. 40, 496–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896860820953050 (2020).

Bowes, E. et al. Acute peritoneal dialysis with percutaneous catheter insertion for COVID-19-Associated acute kidney injury in intensive care: Experience from a UK tertiary center. Kidney Int. Rep. 6, 265–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2020.11.038 (2021).

Caplin, N. J. et al. Acute peritoneal dialysis during the COVID-19 pandemic at Bellevue Hospital in New York City. Kidney 1, 1345–1352. https://doi.org/10.34067/KID.0005192020 (2020).

Fisher, R. et al. Provision of acute renal replacement therapy, using three separate modalities, in critically ill patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. An after action review from a UK tertiary critical care centre. J. Crit. Care 62, 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.12.023 (2021).

Shankaranarayanan, D. et al. Peritoneal dialysis for acute kidney injury during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. Kidney Int. Rep. 5, 1532–1534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2020.07.017 (2020).

Sourial, M. Y. et al. Urgent peritoneal dialysis in patients with COVID-19 and acute kidney injury: A single-center experience in a time of crisis in the United States. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 76, 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.06.001 (2020).

Kellum, J. A. et al. Kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) acute kidney injury work group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2, 1–138. https://doi.org/10.1038/kisup.2012.1 (2012).

Nolph, K. D. & Sorkin, M. I. Peritoneal dialysis in acute renal failure. In Acute Renal Failure 2nd edn (eds Brenner, B. M. & Lazarus, M. J.) 809–838 (Churchill Livingstone, 1988).

Watson, P. E., Watson, I. D. & Batt, R. D. Total body water volumes for adult males and females estimated from simple anthropometric measurements. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 33(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/33.1.27 (1980).

Daugirdas, J. T., Blake, P. G., Ing, T. S. Acute Peritoneal Dialysis Prescription. Handbook of Dialysis, LW&W, 333–342, (2001).

Du Bois, D. & Du Bois, E. F. The measurement of surface area of man. Arch. Int. Med. 15, 868–881 (1925).

ChumleaWC, R. A. F. & Steinbaugh, M. L. Estimating stature from knee height for persons 60–90 years of age. JamGeriatr. Soc. 33(2), 116–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1985.tb02276.x (1985).

Liaño, F. et al. Prognosis of acute tubular necrosis: An extended prospectively contrasted study. Nephron 63(1), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1159/000187139 (1993).

Schrier, R. W., Wang, W., Poole, B. & Mitra, A. Acute renal failure: definitions, diagnosis, pathogenesis, and therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 114(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI22353 (2004).

Al Sahlawi, M., Ponce, D., Charytan, D. M., Cullis, B. & Perl, J. Peritoneal dialysis in critically Ill patients: Time for a critical reevaluation?. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18(4), 512–520. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.0000000000000059 (2023).

Ponce, D., Zamoner, W., Dias, D. B., Banin, V. & Balbi, A. L. Advances in peritoneal dialysis in acute kidney injury. Rev Invest. Clin. 75(6), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.24875/RIC.23000205 (2023).

Ponce, D. et al. The role of peritoneal dialysis in the treatment of acute kidney injury in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure: A prospective Brazilian study. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 8, 713160. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.713160 (2021).

Rizo-Topete, L. M., Claure-Del Granado, R., Ponce, D. & Lombardi, R. Acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: What are our options for treating it in Latin America?. Kidney Int. 99(3), 524–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.12.021 (2021).

Chitalia, V. C. et al. Is peritoneal dialysis adequate for hypercatabolic acute renal failure in developing countries?. Kidney Int. 61(2), 747–757. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00177.x (2002).

Ponce, D., Zamoner, W., Batistoco, M. M. & Balbi, A. Changing epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury in Brazilian patients: A retrospective study from a teaching hospital. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 52(10), 1915–1922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-020-02512-z (2020).

Macedo, E. & Mehta, R. L. When should renal replacement therapy be initiated for acute kidney injury?. Semin. Dial. 24(2), 132–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-139X.2011.00838.x (2011).

Ostermann, M. et al. 17th acute disease quality initiative (ADQI). Consensus group patient selection and timing of continuous renal replacement therapy. Blood Purif. 42(3), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.1159/000448506 (2016).

Annigeri, R. A. et al. Renal support for acute kidney injury in the developing world. Kidney Int. Rep. 2(4), 559–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2017.04.006 (2017).

Ponce, D., Brito, G. A., Abrão, J. G. & Balb, A. L. Different prescribed doses of high-volume peritoneal dialysis and outcome of patients with acute kidney injury. Adv. Perit. Dial. 27, 118–124 (2011).

Gabriel, D. P., Caramori, J. T., Martim, L. C., Barretti, P. & Balbi, A. L. High volume peritoneal dialysis vs daily hemodialysis: A randomized, controlled trial in patients with acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. Suppl. 108, S87-93. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ki.5002608 (2008).

Kilonzo, K. G. et al. Outcome of acute peritoneal dialysis in Northern Tanzania. Perit. Dial. Int. 32(3), 261–266. https://doi.org/10.3747/pdi.2012.00083 (2012).

Parapiboon, W. & Jamratpan, T. Intensive versus minimal standard dosage for peritoneal dialysis in acute kidney injury: A randomized pilot study. Perit. Dial. Int. 37(5), 523–528. https://doi.org/10.3747/pdi.2016.00260 (2017).

STARRT-AKI Investigators; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group; Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group; United Kingdom Critical Care Research Group; Canadian Nephrology Trials Network; Irish Critical Care Trials Group; Bagshaw SM, Wald R, Adhikari NKJ, Bellomo R, da Costa BR, Dreyfuss D, Du B, Gallagher MP, Gaudry S, Hoste EA, Lamontagne F, Joannidis M, Landoni G, Liu KD, McAuley DF, McGuinness SP, Neyra JA, Nichol AD, Ostermann M, Palevsky PM, Pettilä V, Quenot JP, Qiu H, Rochwerg B, Schneider AG, Smith OM, Thomé F, Thorpe KE, Vaara S, Weir M, Wang AY, Young P, Zarbock A. Timing of Initiation of Renal-Replacement Therapy in Acute Kidney Injury. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jul 16;383(3):240–251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000741. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2020 Jul 30;383(5):502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMx200016.

Waikar, S. S., Curhan, G. C., Wald, R., McCarthy, E. P. & Chertow, G. M. Declining mortality in patients with acute renal failure, 1988–2002. J Am Soc Nephrol. 17(4), 1143–1150. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2005091017 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients, AKI team members and investigators who participated in the study.

Funding

This article was not supported by any source and represents an original effort by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in study design and concept. W.Z, A.L.B and D.P. analyzed the data. W.Z. drafted the manuscript; W.Z, D.B.D, J.V.B and M.Z.C.S collected the data; all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors disclose that they do not have any financial or other relationships, which might lead to a conflict of interest regarding this paper.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Botucatu School of Medicine, CAAE: 28325020.5.0000.5411. The patient/participant provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zamoner, W., Dias, D.B., Bannwart, J.V. et al. Changing epidemiology, prescription and outcomes of acute kidney injury patients treated by peritoneal dialysis during 20 years: a cohort study. Sci Rep 16, 145 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29050-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29050-x