Abstract

This paper presents the design, implementation, and experimental evaluation of a visible light communication (VLC) system using a small solar panel with a custom signal-conditioning circuit as an optical receiver in a greenhouse environment. In this context, VLC can enables simultaneous lighting and data transmission, while solar panels can serve dual roles as energy harvesters and receivers. The work focuses on using mini solar panels, coupled with tailored circuitry, to address practical challenges in greenhouse communication. Theoretical modeling includes Lambertian emission and Beer–Lambert attenuation to characterize the optical channel, while accounting for the solar panel’s inherent low-pass filtering, which limits frequency response. Key performance metrics, including received optical power, bit error ratio (BER), and communication range, were evaluated under varying humidity conditions and at different transmitter-receiver distances. Experimental results using a modulated LED source showed that under high-humidity greenhouse conditions, the system achieves BER \(\approx 10^{-3}\) only at short ranges (\(\approx\) 0.3-0.4 m), increasing to \(10^{-2}\)-\(10^{-1}\) for 0.55-0.70 m. Beyond this range, link performance degrades due to receiver sensitivity limits. For reference, comparisons with reported photodetector results under similar greenhouse conditions highlighted that solar panels, while less sensitive at long distances, remain a viable option for robust, low-data-rate VLC applications. These findings offer insights into the design of photovoltaic-based VLC systems, highlighting opportunities to enhance receiver sensitivity and optimize dual-purpose operation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Greenhouses are a fundamental tool in modern agriculture, enabling the controlled cultivation of various crops under adverse climatic conditions1. By regulating internal temperature, humidity, light, and levels of \(CO_{2}\), farmers can achieve significant gains in productivity and quality regardless of outdoor weather2.

However, despite their advantages, greenhouses also pose challenges, as they require near-real-time monitoring compared to open-field farming. Thus, one way to continuously monitor the greenhouse’s internal conditions is through wireless communication systems based on radio frequency (RF)3. Some of these systems have provided solutions that reduce costs and energy consumption compared to a wired sensor network4. Within the internet of things (IoT) paradigm, hybrid wired–wireless architectures have simplified sensor deployment and localization, enhancing scalability5. Furthermore, plant and vegetable care in agriculture is often a delicate task, highly susceptible to external factors, and studies have shown that RF electromagnetism can degrade crop growth and quality6,7.

To overcome these limitations and reduce interference with delicate agricultural processes, visible light communication (VLC) emerged as a viable solution in greenhouse environments. This LED-based technology enables information transmission through the visible-light spectrum, leveraging the unlicensed visible-light band to avoid RF interference and integrates seamlessly with greenhouse lighting8. Furthermore, these systems deliver lower energy consumption and lower infrastructure costs, particularly in hybrid deployments9.

Although greenhouses offer a naturally enclosed lighting-controlled environment ideal for VLC deployment, recent advances have extended VLC use to broader precision agriculture applications. For instance, VLC has been successfully demonstrated in outdoor farming scenarios using LED-based grow lights mounted on unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), enabling simultaneous support for photosynthetic lighting and data transmission in areas with limited sunlight7.

Building on this, the use of solar panels as receivers in VLC systems represents a promising integration. Although traditional photodetectors are more common in these systems due to their high sensitivity and efficiency in detecting visible-light signals, solar panels offer a unique advantage: the ability to combine energy harvesting with data reception. This is particularly relevant in greenhouse environments, where optimizing key resources – such as energy availability, infrastructure costs, and hardware footprint – is crucial. Recent advances further support this perspective: for example, organic photovoltaic (PV) cells have demonstrated record-breaking speeds and simultaneous energy harvesting10, while studies with commercial silicon and amorphous-silicon panels have confirmed their robustness under direct sunlight and adverse conditions11,12. Consequently, solar panels exhibit dual functionality by simultaneously generating electrical energy and receiving optical signals, thereby improving system sustainability and reducing operational costs13.

Although VLC systems that employ solar panels as receivers have yet to be experimentally demonstrated in greenhouse settings, several studies have highlighted their feasibility in other contexts. For example, Malik and Zhang14 demonstrated simultaneous energy harvesting and data transmission using solar panels, while Shin et al.13 proposed a self-biased architecture that achieves higher data rates in indoor conditions. More recently, Wang et al.15 explored solar-panel-based receivers capable of decoding VLC signals while storing harvested energy. These works underscore the potential of photovoltaic receivers, but none have addressed the specific challenges of agricultural environments. This gap motivates our work to design and experimentally evaluate a VLC–solar panel system tailored for greenhouse communication, focusing on link reliability, bit-error performance, and the signal-conditioning aspects of photovoltaic receivers under varying humidity and propagation distances.

Reliable VLC communication depends on optimizing parameters such as wavelength selection and surface reflections, while other factors, such as scattering from airborne particles, affect the received optical power but cannot be directly controlled. We use BER to quantify link performance and inform the design of error-correction strategies.

Given the absence of experimental data on solar panel-based VLC in greenhouse environments, this study rigorously compares solar panel performance with traditional photodetectors, specifically evaluating metrics such as BER, received optical power across varying distances and resilience under different humidity levels16. Preliminary results reveal that performance significantly degrades beyond one meter, primarily due to the limited sensitivity and low-pass filtering characteristics of the solar panels, highlighting critical areas for future optimization.

It is important to note that although the solar panel used in this system can generate energy, this research will focus exclusively on evaluating communication via the visible-light system. The key contributions of this work are as follows.

-

1.

Design, build, and experimentally validate a VLC system using solar panels as receivers in greenhouse environments.

-

2.

Compare the performance of solar panel-based receivers with traditional photodetectors, using our experimental results and reference data from the literature, to evaluate the feasibility of this approach under greenhouse conditions.

-

3.

Analyze the impact of environmental factors, such as temperature and humidity, on the performance of the VLC system with solar panel receivers.

-

4.

Evaluate the technical viability and scalability of deploying solar panel-based VLC systems in commercial greenhouse settings.

Unlike previous PV-based VLC studies that focused on controlled indoor tests, this work presents, to the best of our knowledge, one of the first experimental validations in a real greenhouse with varying humidity, temperature. We also propose a bias-free analog conditioning circuit tailored to the low-pass behavior of commercial PV panels and use a pulse-width modulation-amplitude shift keying (PWM–ASK) modulation scheme for stable performance under humid conditions.

Moreover, conducting empirical studies of wireless communications–regardless of their operating frequency or technique–makes valuable contributions to the literature by providing real-world data collected under realistic operational conditions. Through such efforts, different authors collectively build a shared body of knowledge that supports the development and refinement of theoretical and simulation models, enabling more accurate and comprehensive multilayer performance analyses.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work; Section 3 presents the VLC theory for greenhouse environments; Section 4 details the experimental setup; Section 5 presents the performance results; Section 6 discusses the implications of these findings; and Section 7 concludes and outlines future research directions.

Related works

This section reviews the existing literature that focuses on VLC systems in agricultural contexts, highlighting three key areas: (i) VLC deployment in greenhouses and smart farming environments, (ii) the impact of environmental factors on VLC performance, and (iii) the development of solar panel-based VLC receivers. The selected studies highlight both the potential and limitations of VLC systems in realistic agricultural conditions.

VLC systems in agricultural environments

VLC has been proposed as a viable communication alternative in controlled environments such as greenhouses, where reducing RF interference is essential. The study by Vizuete et al.8 evaluates a VLC system using a multiple-input single-output (MISO) model and on-off keying (OOK) modulation. Their simulations, which analyze key metrics such as BER and Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), demonstrated stable performance within typical greenhouse illumination levels (600 to 900 lux), with a uniform light distribution significantly improving link stability.

In a complementary direction, Jativa et al.17 integrate VLC with digital twin simulation in greenhouse and underground farming environments. By strategically positioning the LEDs, the authors report improvement in photodetector performance of up to 10 dB. Despite its effectiveness in harsh environments, the authors suggest hybrid systems that combine VLC with WiFi or 5G to enhance coverage in extensive greenhouse areas.

Environmental impact on VLC performance

Environmental conditions are critical for evaluating VLC system reliability, particularly in greenhouse environments where humidity and airborne particles strongly influence optical propagation. Jativa et al.17 employed an empirical Beer-Lambert-based model to assess the effects of humidity and aerosols on VLC performance, showing that although adequate illuminance levels can be maintained, signal degradation occurs in high-humidity scenarios.

In this context, our work extends beyond the modeling by providing experimental evidence from a greenhouse testbed, where the optical power received and the BER are systematically evaluated under different humidity levels using solar panels as receivers. This connection between theoretical models and real measurements strengthens our understanding of the environmental impact on VLCs and highlights its practical implications for PV systems in precision agriculture. Moreover, recent studies have proposed dynamic models to optimize the frequency response of photovoltaic receivers18, strengthening the need to validate such approaches under realistic agricultural conditions.

Solar-panel-based VLC systems

A growing body of work investigates the use of PV panels as dual-purpose VLC receivers. Malik and Zhang14 presented one of the first studies to demonstrate simultaneous energy harvesting and communication using solar panels. Building on this, Shin et al.13 proposed a reverse-bias solar panel architecture that integrates a self-powered biasing circuit, achieving data rates of up to 17 Mbps. More recently, Wang et al.15 introduced an optical wireless receiver capable of decoding VLC signals while storing harvested energy. Despite these promising advances, limited attention has been paid to experimentally validating solar-panel-based VLC systems under realistic agricultural conditions. In contrast to previous work, our study provides experimental data collected in a controlled greenhouse environment, evaluating key metrics, including BER, received optical power, and resistance to humidity variations.

Advances in LED array modeling and optothermal control

Recent studies have explored advanced modeling and optimization techniques for LED arrays, emphasizing the coupling between thermal and optical behavior and the use of intelligent data-driven methods. Recent works19,20,21 highlight how optothermal characterization, hyperspectral imaging, and machine-learning-based control are reshaping the design of efficient and stable emitters. These developments illustrate the growing importance of thermal–optical co-design in modern LED-based systems, conceptually aligned with our analysis of VLC performance under varying environmental conditions.

Theoretical system model

This section presents the theoretical framework and the underlying assumptions for modeling the proposed VLC system within greenhouse environments. The modeling approach comprises five core components: the LED transmitter model, optical channel propagation (using combined Lambertian and Beer-Lambert assumptions), PV panel receiver characteristics, analog signal conditioning circuitry, and digital sampling and processing techniques. These models collectively enable a realistic evaluation of system performance under practical greenhouse conditions, explicitly accounting for environmental and device-specific factors.

Transmitter and optical channel overview

We adopted the LED emission strategy used by Pezoa et al.16, in which an LED serves as an optical source. Its emission is modeled using the Lambertian radiant intensity pattern. Specifically, the radiant intensity is defined as follows:

where \(m = 1\), corresponding to a half-power semi-angle \(\Phi _{1/2} \approx 60^\circ\), as per16, Eq. (1). Here, \(R_0(\phi )\) denotes the radiant intensity (in watts per steradian, W/sr), which describes the angular distribution of the optical power emitted by the LED. It indicates how the emitted power varies with the angle \(\phi\) relative to the axis of maximum emission. The parameter \(m\), known as the Lambertian order, controls the directivity of the emission pattern - higher values of \(m\) correspond to more directional beams.

The LED is placed to maintain a direct line-of-sight (LoS) path with the PV panel receiver. Its orientation is adjusted to either a vertical or an inclined configuration to optimize received power across the greenhouse coverage area.

In our implementation, the LED luminaire was driven in a simple on–off configuration without requiring an explicit device-level LED model or bias optimization study, as the focus of this work was on the receiver-side behavior. The LED unit and the driver were adopted from Pezoa et al.16 and operated under fixed-bias conditions in all experiments.

Unlike Pezoa et al.16, which employs OOK in some configurations, this work adopts PWM-ASK. The choice of this scheme was motivated by two factors: (i) maintaining consistency with the modulation scheme used in the study by Pezoa, which allows for a fairer comparison between photodetectors and solar panel receivers under similar greenhouse conditions, and (ii) its superior compatibility with the LED driver response, as previously demonstrated. Although OOK generally offers simpler demodulation, PWM-ASK provides a more stable optical signal in this experimental setup.

An exploratory analysis was conducted to assess the impact of temperature variations on optical power transmission. Under the relatively stable thermal conditions of the greenhouse, the measured fluctuations in received optical power were minimal and therefore were considered negligible for practical purposes. Consequently, temperature effects were not incorporated into the transmitter model. It is important to clarify that this assessment refers to environmental temperature variations that affect the optical channel, rather than self-heating of the LED source, which represents a distinct phenomenon.

Optical channel modeling: Lambertian propagation and atmospheric attenuation

The optical wireless channel is modeled as a LoS component subject to geometric spreading and atmospheric attenuation.

The LoS direct current (DC) channel gain, under the Lambertian model, represents the optical power gain and is given by:

where \(A\) is the effective area of the receiver, \(d\) is the distance between the LED and the PV, \(\phi\) and \(\psi\) are the angles of irradiance and incidence, \(T_s(\psi )\) is the optical filter gain, \(g(\psi )\) is the concentrator gain.

Atmospheric absorption is modeled by the Beer–Lambert Law (BLL), expressing exponential signal attenuation over distance, as follows:

Here, \(\alpha\) represents the attenuation coefficient, experimentally determined by measuring signal attenuation at varying humidity levels and aerosol densities specific to greenhouse environments.

Although both models (Lambertian propagation and Beer–Lambert attenuation) can be combined to obtain a complete analytical expression for the optical channel, in this work we focus primarily on the experimental characterization of received power and BER. Therefore, the equations are presented as a conceptual reference to highlight the main factors influencing VLC performance in greenhouse scenarios, rather than for direct numerical comparison.

Receptor model based on AC component

For VLC systems that employ PV panels as receivers, only the alternating current (AC) component of the photocurrent is typically used for communication, while the DC component serves as a power harvester22. Under small-signal AC conditions, the panel behaves as a first-order low-pass filter, with its cutoff frequency determined by the load resistance and the junction capacitance. This relationship explains the need to carefully select the load resistance: lower values increase bandwidth at the expense of signal amplitude. In our experiments, this trade-off motivated the choice of a 220 \(\Omega\) resistor, which provided sufficient bandwidth while maintaining acceptable signal strength.

As we can observe in work22, under small signal AC conditions, the terminal behavior of the photovoltaic panel resembles a first order low-pass filter, with the cutoff frequency governed by the internal capacitance of the panel \(C\) and the load resistance \(R_{\text {load}}\) as follows:

Typical cut-off frequencies \(f_{\text {cutoff}}\) for commercially available solar panels range between a few kHz to tens of kHz, governed by their internal capacitance (\(C \approx\) tens of nanofarads) and chosen load resistances.

Decreasing the load resistance \(R_{\text {load}}\) increases the bandwidth at the cost of reducing the amplitude of the signal, highlighting an essential trade-off for dual-purpose VLC systems. For example, halving \(R_{\text {load}}\) doubles \(f_{\text {cutoff}}\) while reducing the peak AC voltage by approximately 3 dB. This trade-off is critical in dual-purpose VLC systems, where optimizing communication can reduce energy-harvesting efficiency22.

Receiver architecture and signal conditioning

In the proposed system, the PV panel operates as a passive optical-to-electric transducer. Incident-modulated light induces a small potential across the panel terminals without external bias, simplifying the circuit and eliminating the need for a transimpedance amplifier. However, the resulting voltage signal is weak and must be conditioned prior to digital sampling.

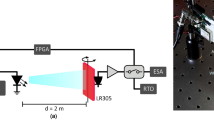

The analog front-end of the receiver, including the AC coupling, amplification, and offset adjustment stages, is shown in Fig. 1. This circuit conditions the weak voltage signal from the PV panel before digital sampling.

The analog front-end first removes the DC offset induced by ambient light through AC coupling, implemented via a high-pass filter as follows:

Using \(R = 1\,\text {k}\Omega\) and \(C = 100\,\text {nF}\), the filter exhibits a frequency cutoff at 1591 Hz. This value was selected to effectively isolate the AC communication signal from the ambient DC background, aligning optimally with the frequency range of our PWM modulation.

The AC component is then amplified using an operational TL072 amplifier in a non-inverting configuration. The TL072 was chosen for its higher supply-voltage tolerance compared to typical operational amplifiers, which was necessary for subsequent signal-processing stages. The voltage gain is given by:

with \(R_5 = 1\,\text {k}\Omega\) and \(R_6 = 10\,\text {k}\Omega\), resulting in a gain of \(G = 11\).

To align the amplified signal with the Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) input range (0–3.3 V), a voltage divider creates a mid-scale DC reference voltage as follows:

where \(R_9 = 10\,\text {k}\Omega\) and \(R_{10} = 1\,\text {k}\Omega\) set the reference near 1.65 V.

This reference and the amplified AC signal are summed via a non-inverting summing amplifier as follows:

where \(V_1\) is the amplified signal and \(V_2\) is the reference offset. A 3.3 V Zener diode clamps the final output voltage to protect the ADC input from overvoltage.

Sampling and signal processing

The conditioned analog signal is digitized by the 12-bit Raspberry Pi Pico (RPP) ADC, which maps input voltages in the 0 to 3.3 V range to integer values from 0 to 4095. The resulting voltage-time samples are processed offline using a multistage algorithm designed to robustly recover the transmitted information.

First, each ADC value is converted to its corresponding voltage, as we can see in the following expression:

After that, a square deviation metric \((SDM)\) is computed with respect to a predefined DC offset. This highlights signal transitions and suppresses the static background.

To improve detection of logical levels of ’1’, a selective enhancement is applied to the \(SDM\) signal. This operation, termed \(SDM_{crop}\), raises small \(\sigma\) values proportionally to a running local maximum, highlighting recent transitions while suppressing noise.

An aggregate feature named AddProd is then computed by combining recent \(SDM\) and \(SDM_{crop}\) values in a weighted product sum as follows:

Binary-state classification is performed using a fixed threshold as follows:

The threshold value of 0.01 was empirically determined by analyzing signal statistics in multiple trials to minimize false positives while preserving sensitivity to legitimate pulses.

From the resulting bitstream, the ON and OFF durations are identified and assigned to modulation patterns (e.g., 25/75 ms). Finally, the reconstructed data are compared with a reference sequence to compute the BER and quantify transmission accuracy.

Limitations: While this model accounts for primary attenuation mechanisms, secondary effects such as diffuse reflections from plant surfaces or structural materials are not explicitly modeled here and could influence real-world VLC performance.

Methods

This section presents the experimental methodology used to validate the VLC system within a realistic greenhouse environment. The description begins with an overview of the overall VLC system, followed by detailed descriptions of transmitter and receiver setups, including specific components, circuit configurations, and measurement protocols.

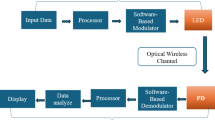

Overall VLC system

The dimensions of the greenhouse (\(126 \times 49 \times 69\) cm) replicate typical small-scale greenhouse modules commonly used for precision agriculture research and agriculture, ensuring realistic propagation characteristics. The plastic structure provides low optical reflectivity and creates a sealed environment, minimizing external interference. Live plants were strategically placed inside the greenhouse to simulate realistic vegetation-induced scattering and absorption effects on the propagation of VLC. Fig. 2 shows a schematic diagram of the greenhouse, while Fig. 3 presents an image of the experimental setup.

Typical greenhouse humidity conditions were simulated using a generic USB humidifier, while the temperature was naturally stabilized by the enclosed greenhouse structure. Temperature and humidity were monitored using a DHT22 sensor, which integrates a capacitive humidity sensing element and a thermistor for temperature measurement. Humidity was actively varied between 30% and 80%, a realistic range reflecting typical greenhouse conditions encountered in diverse agricultural climates, allowing for a detailed evaluation of the environmental robustness of the VLC system.

The solar panel was placed at seven discrete heights (30 to 130 cm at intervals of approximately 15 to 25 cm), systematically characterizing the performance of VLC in typical vertical variations representative of crop heights within greenhouses. Minor temperature fluctuations occurred naturally and were considered negligible in terms of their impact on the performance of the VLC system. These variations were mainly attributed to air exchange through structural gaps. Active temperature control was omitted for simplicity and practicality, given the greenhouse’s naturally stable thermal conditions. However, minor fluctuations were monitored to ensure minimal impact on the results.

Although the experimental configuration closely emulates realistic environmental conditions, potential limitations include the lack of active control of ambient temperature and the absence of a quantitative evaluation of plant-induced scattering and reflections, which may influence the fine-grain characterization of the system.

Summary: This setup replicates realistic greenhouse conditions, allowing controlled evaluation of VLC performance under plant-induced scattering and environmental variability.

Transmitter stage

The VLC transmitter employs a hybrid modulation scheme combining PWM and ASK, hereafter referred to as PWM–ASK. This approach encodes information in both the duty cycle and amplitude of the optical signal, enabling improved robustness under greenhouse lighting conditions. PWM defines the baseband symbol timing, while ASK modulates the optical carrier intensity generated by the LED driver.

A single high-power white LED (30 W) was driven using a DC bias tee to combine a 10 Vpp, 10 kHz sinusoidal carrier with a 10 Hz PWM envelope. The PWM duty cycles were selected from a set of predefined patterns (ON/OFF durations of 25/75, 50/50, and 75/25 ms) corresponding to the logical bits ‘1’ and ‘0’. The ASK depth was kept constant at 100% to ensure a stable optical amplitude and avoid perceptible flicker for plant illumination.

This hybrid PWM–ASK modulation provides continuous light emission compatible with horticultural lighting while maintaining data integrity through carrier-level amplitude modulation. Compared with OOK or pure PWM, PWM–ASK offers a higher SNR and improved resistance to ambient light interference, which is critical in greenhouse environments.

Fig. 4 presents the two-part schematic of the transmitter system, consisting of a microcontroller, signal generator, bias tee, and LED. The main functional elements and their roles in the transmitter stage are detailed below:

-

1.

An RPP is used that outputs a 10 Hz PWM signal with variable pulse width. This frequency was initially chosen as a simple baseline for experimental testing, mainly to facilitate implementation and observation of the LED response during early trials. However, the current from the RPP output is only 23 mA, which is less than the required to drive the LED directly. The signal must therefore be amplified and conditioned appropriately with other components to drive the LED properly.

-

2.

The RPP output is connected to a Tektronix TBS 1000C Signal Generator (SG) through the Trigger-In port. The SG operates in modulation mode, using the external trigger to modulate a sinusoidal carrier. When the SG detects an ON state at the Trigger-In input, it modulates the carrier in amplitude and pulse width, resulting in a signal that combines ASK and PWM. However, this output is a bipolar signal that cannot be used directly with an LED because it includes a negative voltage that the LED cannot represent.

-

3.

To adapt the signal for LED transmission, the SG output is connected to a DC Bias Tee. The Bias Tee shifts the signal by superimposing a 20 V DC component, converting it into a unipolar signal suitable for driving the LED. This adjustment ensures that the signal maintains only positive polarity while being powerful enough to activate the LED. The variations in signal amplitude are then interpreted as LED intensity modulation.

-

4.

The final output signal, which results from the combination of the RPP, SG, and Bias Tee stages, is used to drive the LED. The LED brightness varies according to the incoming data stream using an OOK non-return-to-zero (OOK-NRZ) modulation scheme.

Fig. 5 presents a diagram that illustrates the signal waveforms at different stages of the transmission chain: the initial PWM signal from the RPP, the modulated ASK+PWM signal from the signal generator and the signal shifted by the Bias Tee. This schematic representation is intended to facilitate the understanding of how the signal evolves throughout the system.

Summary: This transmitter setup ensures sufficient modulation of the intensity of the LED to validate communication performance under realistic greenhouse conditions, addressing both the variations of amplitude and pulse width.

Receiver stage

The VLC receiver system captures the modulated light signal, converts it to an electrical signal, and processes it for data extraction. It comprises three main components: a PV used as a light detector, an analog conditioning circuit, and an RPP microcontroller that performs digitization and initial data handling. The main components and their specific functions are detailed as follows:

-

1.

The PV serves as the optical front-end. Positioned at the same height as the crops and aligned directly with the LED source, it avoids the need for tilt-angle compensation and simplifies the experimental setup. This configuration ensures consistent reception under typical greenhouse conditions, including ambient light interference. The panel generates a voltage in response to incident modulated light. An oscilloscope visualization of the received waveform shows amplitude-modulated PWM pulses, allowing direct comparison between transmitted and received signals.

-

2.

The signal conditioning circuit processes the analog voltage derived from the panel to facilitate its digital conversion. It eliminates the DC component, amplifies the AC signal, and incorporates a reference offset to align the signal within the ADC range of the RPP. A Zener diode protects the input from voltage spikes, ensuring signal integrity and hardware safety.

-

3.

RPP samples the conditioned signal using its built-in ADC and applies a software-based decoding algorithm. This algorithm identifies logic levels based on voltage deviations, calculates pulse durations, detects signal patterns, and estimates the BER. The locked data are stored in CSV format for offline analysis. To ensure accurate digital reconstruction, the RPP operated at a sampling frequency of 62.5 kHz, comfortably exceeding the Nyquist criterion for the 10 kHz ASK-modulated PWM signal.

Prior to each measurement, receiver alignment was maximized, and measurements showing front-end saturation at short distances were discarded. In early trials, slight near-field angular misalignment and partial saturation occurred at very short distances (\(\approx 40\) cm), which we document here as a limitation.

Note that the mini polycrystalline PV panel used (6 V, 1 W, \(110 \times 60\) mm) does not include the manufacturer’s spectral responsivity curve. Polycrystalline silicon PV devices typically exhibit a strong response in 400 to 700 nm and measurable near-infrared sensitivity, with the highest efficiency near the red band (650 nm)23.

Table 1 summarizes the experimental conditions.

Receiver frequency characterization

To quantify the small-signal bandwidth of the photovoltaic (PV) receiver, we performed a frequency-sweep experiment using sinusoidal intensity modulation of the LED source. The subcarrier frequency was varied from 0.5 kHz to 50 kHz while maintaining a constant optical amplitude, and the AC voltage across the \(R_\textrm{load}\) was recorded at each frequency. The normalized magnitude response was then computed as

As expected, the measured response follows a first-order low-pass characteristic governed by the equivalent RC time constant of the PV junction and load network, which can be expressed as

Here, \(R_{\text {load}}=220~\Omega\) and \(C_{\text {eq}}\) represent the combined junction and input capacitance of the PV–amplifier interface (approximately 50 nF). The resulting cutoff frequency \(f_{-3\text {dB}}\approx 14\) kHz closely matches experimental observations, confirming the low-pass behavior reported in the main text. Operation within this regime did not show envelope compression or distortion, verifying a linear response across the communication bandwidth of interest.

To connect the frequency response to the system’s performance, BER was measured at several carrier frequencies between 2 kHz and 40 kHz under identical geometry and ambient conditions. For each case, a pseudorandom bit sequence of at least \(10^{6}\) symbols was transmitted and processed using the same decoding pipeline as in the main experiments. The BER remained below \(10^{-2}\) up to approximately 15 kHz, gradually increasing beyond the 14 kHz cutoff. These results confirm that the VLC system operates near the optimal frequency region around 10 kHz, where the PV receiver maintains a flat response and minimal intersymbol interference.

Summary: This receiver configuration enables the reliable detection of modulated light signals using low-cost components and real-time data acquisition, facilitating accurate performance evaluation of the VLC system under greenhouse conditions.

Results and analysis

This section presents the experimental evaluation and analysis of the VLC system’s performance using solar panels as receivers within the greenhouse. Two key metrics (received optical power and BER) are analyzed across varying distances and humidity levels, followed by an interpretive discussion comparing solar panels with conventional photodetectors.

To ensure measurement reliability, each scenario was evaluated in three repeated trials, with results averaged to reduce the influence of random fluctuations.

Received power

The optical power received was indirectly determined by measuring the solar panel’s electrical output and calibrating it to the incident optical intensity, thereby ensuring accurate quantification of VLC link performance. Measurements were systematically performed at multiple distances and across a range of humidity levels. Fig. 6 shows the relationship between the power received and the distance for humidity values ranging from 30 to 80%.

As expected, the received power decreased as the distance between the LED and the panel increased. Furthermore, lower humidity levels (for example, 30%) resulted in higher received power, particularly at short distances (e.g., 40–55 cm). The pronounced reduction in received power at high humidity levels (80%) is due to the increased scattering and absorption by airborne moisture particles, consistent with Beer-Lambert-based attenuation modeling.

Beyond 100 cm, the influence of humidity diminishes as signal attenuation is primarily governed by geometric path loss rather than environmental absorption.

Summary: These findings confirm that although the optical power received decreases with distance, the performance of the system remains robust at shorter distances under various humidity conditions, demonstrating the feasibility of VLC in realistic agricultural settings.

Bit error ratio (BER)

A large sample size of 300,000 transmitted pulses per scenario was selected, with the number of transmitted symbols sufficient to accumulate several thousand errors per scenario, ensuring statistically robust BER calculations and minimizing uncertainty and random fluctuations.

The BER was determined by transmitting 300,000 samples per test case and processing the received waveform using a decoding algorithm. The signal was reconstructed based on detection thresholds and bit intervals, with an error identified when the detected pulse width deviated by more than 10 ms from the expected pattern. This 10 ms threshold was empirically determined to balance timing sensitivity with robustness to noise-induced jitter.

Statistical uncertainty was evaluated under the binomial model using the Wilson score method to obtain 95% confidence intervals, which provide stable bounds even for small error probabilities. The resulting confidence intervals were narrow, typically within ±0.001, demonstrating high repeatability across all test conditions. For instance, at a distance of 70 cm and 70% relative humidity, the average BER was \(3.6\times 10^{-2}\) [95% CI: 3.58–\(3.65\times 10^{-2}\)], whereas at 115 cm and 50% humidity the BER increased to \(1.8\times 10^{-1}\) [95% CI: 1.79–\(1.80\times 10^{-1}\)]. This is also consistent with a static scenario with no temporal variations at the receiver end.

Fig. 7 shows the BER versus distance for various humidity levels. It can be observed that BER increases with distance, consistent with the expected degradation of signal quality over longer optical paths. Although in the early version of this curve there was a slight non-monotonic behavior around 40–80 cm, which was traced to near-field geometry and partial front-end saturation at short range. At short distances (55–70 cm), the BER values remained in the range of \(10^{-2}\) to \(10^{-1}\), showing limited variation in humidity conditions. These values are compatible with lightweight FEC for telemetry at several kbps. However, from 85 cm, the BER increased significantly, even exceeding \(10^{-1}\) at 110 cm. Interestingly, a slight improvement in BER at high humidity (70–80%) may result from reduced multipath interference, as moisture-induced absorption attenuates scattered reflections more than the direct path, effectively improving overall signal-to-noise conditions.

These results confirm that humidity has a more pronounced effect on BER at longer distances, whereas its impact is limited in the near-field.

Although the measurements captured key propagation factors, potential secondary influences, such as diffuse reflections from plant surfaces and structural components, were not individually quantified and could affect system performance.

Summary: These results highlight that although BER generally increases with distance, performance remains acceptable at close range. The unexpected improvement in BER under high-humidity conditions underscores the complex interplay between scattering and absorption in modulating VLC link quality.

Discussion and comparison

The following discussion compares the performance of the photodiode (PD) and PV receivers under experimental conditions as closely as possible. However, certain differences were unavoidable due to the specific objectives and constraints of each setup. For instance, in the PV panel tests, a fixed pulse width was used; given the IoT focus, temperature effects were deemed irrelevant; and the panel’s structural characteristics limited the maximum measurement distance. Both devices were tested in the same greenhouse environment, ensuring comparable ambient humidity and scattering factors. The modulation scheme, signal power, and test procedures were kept constant to enable a fair evaluation of BER, power received and communication range.

It is important to note that the PD front-end was not optimized in this study. The PD was operated without a transimpedance amplifier (TIA), with reduced effective transimpedance to favor bandwidth, a smaller active area than the PV panel, and without an optical concentrator or optical filtering. Consequently, the PD curve is reported as a qualitative baseline rather than a fundamental limit.

The results shown in Figs. 6 and 7 show that while photodetectors exhibit superior sensitivity and lower BER at short distances (below 80 cm), their performance rapidly deteriorates beyond this range, especially under the combined effects of signal attenuation and environmental factors such as high humidity and scattering from plant surfaces. At humidity levels of 75% and 100%, the photodetector shows a BER approaching unity beyond 100 cm, indicating complete communication loss.

In contrast, the PV-based receiver maintains a remarkably stable BER within the intermediate distance range (40 to 100 cm), with minimum BER values below \(10^{-2}\) particularly observed at humidity levels 60% to 70%. This behavior directly correlates with the previously observed smoother decay of the optical power received in solar panels compared to the PD. The large active area and greater tolerance to diffuse and indirect light components enable the solar panel to maintain acceptable signal levels even at greater distances.

However, beyond 100 cm, the BER of the solar panel-based receiver progressively increases, converging with the photodetector’s poor performance at long ranges. This limitation is attributed to the inherently lower responsivity and slower response time of photovoltaic materials, which become critical as the signal power approaches the receiver noise floor.

Unlike previous studies of PV-based VLC conducted in lab settings, our results show that reliable communication is achievable under the varying humidity and diffuse light conditions of real greenhouses.

Future improvements may include enhanced signal-processing circuits to mitigate BER at longer distances or dynamic threshold algorithms that adapt to variations in received power.

Conclusions and future work

This study experimentally evaluated the feasibility and performance of using PV panels as optical receivers in VLC systems designed for realistic greenhouse environments. The experiments, conducted under varying humidity levels (30%–80%) and transmission distances (40–130 cm), confirmed that solar panels constitute a viable alternative to conventional photodetectors for short-range, low-data-rate VLC applications. The system achieved a low BER of approximately \(10^{-3}\) only at very short ranges (approximately 0.3–0.4 m). For intermediate distances (0.55–0.70 m), the BER increased to the \(10^{-2}\)–\(10^{-1}\) range, reflecting the combined effects of attenuation, ambient light interference, and the inherent low-pass filtering behavior of the PV receivers. These values are compatible with lightweight FEC for several kbps of telemetry. However, performance degradation was observed at longer distances due to the limited sensitivity and inherent low-pass filtering characteristics of PV panels, highlighting the practical constraints for long-range VLC deployment.

In general, the results demonstrate the potential of PV-based VLC systems to provide both communication and energy functionalities within controlled-environment agriculture. The findings suggest that further improvements in receiver design and signal processing could substantially enhance performance and enable scalable, energy-efficient communication networks in greenhouse settings.

Future work will address these challenges in the following directions:

-

Energy-harvesting receiver nodes: Integrate energy harvesting with data reception to enable battery-free or long-life VLC sensor nodes for precision agriculture, including co-optimization of energy harvesting and communication duty cycles.

-

Higher-bandwidth PV/TIA and receiver architectures: Develop and evaluate photovoltaic materials, packaging, and transimpedance amplifier (TIA) designs that increase receiver bandwidth and sensitivity to mitigate current low-pass limitations.

-

Adaptive detection, coding and modulation: Explore adaptive detection methods and forward-error-correction (FEC), as well as adaptive modulation schemes (e.g., M-QAM, OFDM), that react to changing illuminance and channel conditions to reduce BER and extend effective range.

-

MIMO and multi-point networking: Investigate arrays of LEDs and PV receivers (MIMO) and multi-node networking strategies to improve coverage, throughput, and resilience in dynamic greenhouse topologies.

-

Propagation and field characterization: Conduct targeted studies and long-duration trials to quantify diffuse reflections, scattering from plant canopies and structures, and other site-specific propagation effects; follow with field deployments to evaluate system performance under realistic operational cycles.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Van Straten, G., van Willigenburg, G., van Henten, E. & van Ooteghem, R. Optimal Control of Greenhouse Cultivation (CRC Press, 2010).

Badji, A., Benseddik, A., Bensaha, H., Boukhelifa, A. & Hasrane, I. Design, technology, and management of greenhouse: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 373, 133753 (2022).

Kochhar, A. & Kumar, N. Wireless sensor networks for greenhouses: An end-to-end review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 163, 104877 (2019).

Chen, F., Qin, L., Li, X., Wu, G. & Shi, C. Design and implementation of zigbee wireless sensor and control network system in greenhouse. In 2017 36th Chinese Control Conference (CCC) (ed. Chen, F.) 8982–8986 (IEEE, 2017).

Mirabella, O. & Brischetto, M. A hybrid wired/wireless networking infrastructure for greenhouse management. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 60, 398–407 (2010).

Zhou, X. & Wang, S. Recent developments in radio frequency drying of food and agricultural products: A review. Drying Technol. 37, 271–286 (2019).

Ibraiwish, H., Eltokhey, M. W. & Alouini, M.-S. Uav-assisted vlc using led-based grow lights in precision agriculture systems. IEEE Internet Things Magazine 7, 100–105 (2024).

Vizuete, J. D. R., Canchingre, F. G. T., Caicedo, S. S. G. & Mera, C. A. C. Diseño y evaluación de un sistema de comunicación por luz visible aplicado a entornos de invernaderos: Design and evaluation of a visible light communication system applied to greenhouse environments. Revista Cientifica Multidisciplinar G-nerando4 (2023).

Khreishah, A. et al. A hybrid rf-vlc system for energy efficient wireless access. IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw. 2, 932–944 (2018).

Tavakkolnia, I. et al. Organic photovoltaics for simultaneous energy harvesting and high-speed mimo optical wireless communications. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 41 (2021).

Das, S. et al. Effect of sunlight on photovoltaics as optical wireless communication receivers. J. Lightwave Technol. 39, 6182–6190 (2021).

Kong, M. et al. Toward self-powered and reliable visible light communication using amorphous silicon thin-film solar cells. Opt. Express 27, 34542–34551 (2019).

Shin, W.-H., Yang, S.-H., Kwon, D.-H. & Han, S.-K. Self-reverse-biased solar panel optical receiver for simultaneous visible light communication and energy harvesting. Opt. Express 24, A1300–A1305 (2016).

Malik, B. & Zhang, X. Solar panel receiver system implementation for visible light communication. In 2015 IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits, and Systems (ICECS) (ed. Malik, B.) 502–503 (IEEE, 2015).

Wang, Z., Tsonev, D., Videv, S. & Haas, H. On the design of a solar-panel receiver for optical wireless communications with simultaneous energy harvesting. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 33, 1612–1623 (2015).

Pezoa, M. C. et al. Design and evaluation of a visible light communication system under varied atmospheric conditions for smart and sustainable farming. IEEE Access (2024).

Játiva, P. P. et al. Hybrid digital twin model for greenhouse and underground environments. IEEE Access 12, 73906–73924 (2024).

Chen, S., Yu, H., Zhao, N. & Chen, L.-K. A dynamic model for frequency response optimization in photovoltaic visible light communication. J. Lightwave Technol. 41, 6923–6929 (2023).

Zhang, R. et al. Accurate measurement and fast prediction of optothermal properties of led arrays. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement (2025).

Liu, G. et al. Two-dimensional photothermal modeling of multichip leds device with thermal coupling matrix by microscopic hyperspectral imaging. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices (2024).

Shen, C. et al. Machine-learning-assisted and real-time-feedback-controlled growth of inas/gaas quantum dots. Nat. Commun. 15, 2724 (2024).

González-Uriarte, A., Azurdia, C., Torreblanca, D., Palacios-Jativa, P. & Zabala-Blanco, D. Design and implementation of a low-cost vlc photovoltaic panel-based receiver with off-the-shelf components. In 2024 IEEE Latin-American Conference on Communications (LATINCOM) (ed. González-Uriarte, A.) 1–6 (IEEE, 2024).

Gouvêa, E. .C., Sobrinho, P. M. & Souza, T. M. Spectral response of polycrystalline silicon photovoltaic cells under real-use conditions. Energies 10, 1178 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Project FONDECYT Iniciación 11240799; Project FONDECYT Regular 1211132; Proyecto ANID Vinculación Internacional FOVI 240009; STIC-AMSUD AMSUD240007 DORSAL-IoT; CORFO CoTH2O - 20CTECGH-145896; Universidad de Las Américas under Project 563.B.XVI.25, Department of Networking and Telecommunication Engineering; Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador under Project PEP QINV0485-IINV528020300, FIA(Chile) PYT-2024-0492 and Advanced Center for Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Basal Project CIA 250006.

Funding

This work was supported by Project FONDECYT Iniciación 11240799; Proyecto ANID Vinculación Internacional FOVI 240009; STIC-AMSUD AMSUD240007 DORSAL-IoT; CORFO CoTH2O - 20CTECGH-145896; Universidad de Las Américas under Project 563.B.XVI.25, Department of Networking and Telecommunication Engineering; Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador under Project PEP QINV0485-IINV528020300, and FIA(Chile) PYT-2024-0492.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.C., P.P. conceived the experiment(s), G.C., P.P. conducted the experiment(s), G.C., P.P., D.D., L.A. analysed the results. G.C., P.P wrote the first version of the manuscript. G.C., P.P, C.A., I.S.S., I.S., C.S, wrote the second version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morales, G.C., Játiva, P.P., Dujovne, D. et al. Experimental design and performance evaluation of a solar panel-based visible light communication system for greenhouse applications. Sci Rep 15, 45184 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29067-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29067-2