Abstract

The depositional age, provenance and tectonic setting of the Xujiahe Formation have been studied, but remain intensely debated. In this study, we focus on the second segment of the Xujiahe Formation (T3x2) as a research object. Several sandstone samples from three sections were collected for stratigraphic, geochemical and detrital zircon analyses. Stratigraphic assemblage and features of the three sections indicate a braided river delta depositional setting, and detrital zircon U–Pb dating constrains a Late Triassic depositional age. Whole-rock geochemistry suggests that the sandstones exhibit a low degree of palaeo-weathering and primarily derived from upper crustal felsic rocks. Detrital zircons within these sandstones display uniform age peaks at intervals of 2000–1800 Ma and 500–200 Ma, with similar Hf isotopic compositions compared to those of detrital and magmatic zircons from the South Qinling Block. Taken together, these zircon age spectra and Hf isotopic signatures is determined to be indicate a mixed clastic provenance, with contributions from both the Qinling Orogenic Belt and the Yangtze Block. The clastic particle composition and whole-rock geochemistry indicate that the T3x2 was deposited in a passive margin tectonic setting, located within a braided river delta fed by several NE-SW-oriented paleo-rivers

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Xujiahe Formation is a Triassic stratigraphic unit well known for its rich oil and gas resources1,2,3. As a very thick sequence widely distributed in the Sichuan Basin and composed mostly of clastic sediments, especially sandstones4, it is an ideal subject for investigating depositional environment and provenance. Recent studies remain controversial regarding the provenance of the Xujiahe Formation, entirely different viewpoints have been proposed including the Qinling Orogenic Belt, Yangtze Block, Songpan-Ganzi terrane and/or mixed origin5,6,7,8. Moreover, few studies have thoroughly investigated the depositional age and environment of the Xujiahe Formation. These controversies and research gaps have led to differing interpretations of the provenance and tectonic evolution of the Sichuan Basin.

To clarify these debates, Table 1 summarizes representative viewpoints from previous studies on the Xujiahe Formation’s depositional age, provenance, and tectonic setting. Earlier investigations have offered disparate interpretations: some argued for major sediment input from the west (the Songpan-Ganzi Terrane via the Longmenshan belt), others identified the northern Qinling Orogenic Belt as the primary source, while yet others suggested far-traveled detritus from the south (Yangtze and Cathaysia Blocks). There is also disagreement on the precise timing of deposition within the Triassic and on whether the basin was an active foreland or a passive margin during Xujiahe deposition. Table 1 highlights these contrasting viewpoints. These unresolved issues underscore the need for an integrated approach, which we undertake in this study.

The Xujiahe Formation is composed of four segments. Among these, the second segment (T3x2) contains the highest proportion of sandstone layers and serves as an ideal representative of the whole Xujiahe Formation9,10,11. In contrast, the other three segments contain large proportions of shale and mudstone, making it difficult to constrain their provenance using whole rock geochemistry due to the high loss on ignition and a scarcity of detrital zircons12,13. In this study, we examined three different stratigraphic profiles of the T3x2 in the Northeastern Sichuan Basin. Whole-rock geochemistry of the sandstones, U–Pb–Hf isotopes and trace elements of detrital zircons were conducted to precisely constrain the depositional age, environment and provenance of these sediments. Specifically, we address three questions: (1) when was the T3x2 deposited, (2) what were the main source areas of its detritus, and (3) under what tectonic setting did deposition occur? By investigating these newly uncovered profiles, this study addresses the above questions, which can provide further insight into the tectonic evolution and affinity of the Sichuan Basin.

Geological setting

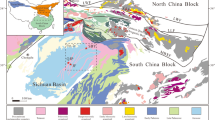

The Sichuan Basin lies in the northeastern part of the Yangtze Block with an area of approximately 260,000 km2 (Fig. 1a). As a well-known “red basin”, the Sichuan Basin is thought to have formed through multiple geological events. The initial shallow sea and delta deposition during the Triassic formed the basic sedimentary layers of the nascent Sichuan Basin3,14,15. Subsequently, as the Paleo-Tethys Ocean started its closure, and the northern, eastern and southern blocks amalgamated along with strong orogenic movements during the Jurassic16. The North China Block (to the north) and the Yangtze Block (to the south) amalgamated along the well-known Qinling–Dabie–Sulu Orogenic Belt, and the Sichuan Basin is located at the western segment-the southern side of the South Qinling Orogenic Belt17,18,19. The Songpan-Ganzi Terrane to the west accreted to the eastern Yangtze Block along the Longmenshan strike-slip fault zone, placing the Sichuan Basin on the eastern side of the Longmenshan fault zone20.

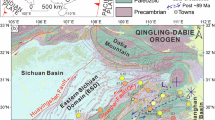

(a) Tectonic location of the Sichuan Basin; (b) Geological map showing the study area and sections. Abbreviations: NCB-North China Block; SCB-South China Block; CB-Cathaysia Block; YB-Yangtze Block; Ql-Qinling Orogenic Belt. The map was generated using CorelDRAW X7 (https://www.coreldrawchina.com/).

The study area is situated at the southeastern Sichuan Basin, within the interior of the Yangtze Block but adjacent to the Qinling Orogenic Belt to the north (Fig. 1b). The area preserves a continuous stratigraphic sequence from the Sinian to the Quaternary, except for an absence of the Silurian strata due to erosion. The Sinian strata are mainly pyroclastic rocks in the lower part, transitioning to shallow-marine carbonates in the upper part. The Cambrian strata comprises sandstone and shale in the lower part, and carbonate in the upper part. The Ordovician is dominated by shallow-marine carbonates with terrigenous mudstone interbeds near the top. The Devonian features deltaic conglomerate and sandstone, whereas the Carboniferous returns to shallow-marine carbonate deposition. From the Permian to the Lower Triassic, sedimentation was relatively stable and continuous in a shallow-marine setting, consisting of thick carbonate rocks with a few intercalated transitional mudstone and shale layers. However, in the Upper Triassic, the strata shifted to transitional (nearshore) and delta facies, mainly composed of conglomerate, sandstone and mudstone. The Jurassic strata consist of lacustrine sandstones and mudstones.

Structurally, the study area is complex due to overprinting of multiple orogenic events through time. During the amalgamation of the surrounding blocks, two primary fault orientations developed in the Sichuan Basin and adjacent blocks. NE–SW-striking faults are well developed along the Longmenshan strike-slip fault zone as subsidiary structures of that major fault system. NW–SE-trending faults occur mainly near the Qinling Orogenic Belt, including Mianlue suture, Shangdan suture, Luonan-Luanchuan fault and Chengkou-Fangxian fault, indicating complex, multi-phase tectonic movements during the convergence of the North China and Yangtze Blocks.

Stratigraphy and sampling

Xujiahe Formation

The Xujiahe Formation is usually known as a complex unit composed mainly of conglomerate, sandstone, and mudstone, and it is also enriched in fossils, coal, oil and gas resources. Previous geological surveys have divided the Xujiahe Formation into six segments, and the second and fourth segments are the dominating oil–gas reservoirs. The second segment (T3x2), which is the focus of this study, contains the thickest sandstone succession in the Formation and is characterized by thick beds of medium to coarse sandstone underlain by conglomerates. Given its substantial sandstone development, T3x2 is an ideal unit to study depositional environment and provenance, which in turn shed lights on the forming of the Xujiahe deposits. In this study, we collect T3x2 samples from three sections in the eastern Sichuan Basin: the Gujunshan section (GS), the Xuanhan Qili section (XQS) and the Dazhu section (DS). Samples were collected for petrographic observation, whole-rock geochemical analysis, and zircon U–Pb–Hf isotopic analysis (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Gujunshan section

The Gujunshan section (GS; 108°07′07.81″E, 31°45′30.72″N), comprises strata from the underlying Leikoupo group and overlying first and second segments of the Xujiahe Formation. The Leikoupo group is mainly exposed as brecciate limestone, while the first segment of the Xujiahe Formation, forming the upper layer with a thickness of approximately 10 m, is composed predominantly of carbonaceous siltstone, carbonaceous shale and carbonaceous mudstone (Fig. 2).

The T3x2 in this section is approximately 160 m thick and can be divided into two parts. The lower to middle part (0–110 m) comprises, from bottom to top, a lithological sequence of coarse-grained sandstone, medium-grained arkosic sandstone, and fine-grained quartz sandstone. The upper part (110–160 m) comprises mudstone and siltstone. Four samples were collected from different layers, including three samples from the middle-lower part and one sample from the upper part. These samples are medium-grained lithic quartz sandstones with poor sorting, angular to subangular grains, and grain sizes of 0.3–0.5 mm (Fig. 3a). Microscopic observation reveals a composition of quartz (70–75%), feldspar (~ 10%), lithic fragments (15–20%) and interstitial material (~ 5%). The quartz predominantly appears as single-crystal quartz, the feldspar is mainly K-feldspar with minor microcline, and the lithic fragments are mainly mudstone, siltstone, andesite, slate and phyllite. The interstitial materials are primarily argillaceous and silty, supplemented by a small amount of carbonate minerals (Fig. 3b).

(a, c, e) Hand specimen photographs and (b, d, f) microscopic photos of sandstone samples from the GS, XQS and DS sections. Abbreviations: Qm-monocrystalline quartz; Qp-polycrystalline quartz; Pl-plagioclase; Kfs-K-feldspar; Ls-lithic fragments of sedimentary rocks; Lm-lithic fragments of metamorphic rocks; Lv-lithic fragments of volcanic rocks.

Xuanhan Qili section

The Xuanhan Qili section (XQS; 107°44′51.42″E, 31°11′41.77″N) similarly comprises strata from the underlying Leikoupo group and the overlying first and second segments of the Xujiahe Formation. The Leikoupo group is mainly argillaceous dolomite, while the first segment of the Xujiahe Formation (about 15–16 m thick), consists of coal-bearing mudstone in the lower part and silty mudstone in the upper part (Fig. 2).

The T3x2 in this section is approximately 180 m thick and can also be divided into two parts. The lower part (0–160 m) begins with basal conglomerate and coarse sandstone, and grades upward into several alternating sandstone-mudstone interlayers. The upper part (160–180 m) is composed of mudstone, fine-grained quartz sandstone and medium-grained lithic quartz sandstone. Eight samples are collected from different layers of the lower part, these are fine- to medium-grained lithic quartz sandstones with poor to moderate sorting and roundness, and grain sizes of 0.1–0.5 mm (Fig. 3c). Under the microscope, the samples consist of quartz (~ 70%), feldspar (10–15%), lithic fragments (∼15%) and interstitial material (~ 5%). The quartz is mostly monocrystalline, the feldspar is mainly K-feldspar with minor microcline; and the lithic fragments are mainly mudstone, siltstone, andesite, tuff and phyllite. The interstitial materials are primarily argillaceous and silty, supplemented by a small amount of carbonate minerals (Fig. 3d).

Dazhu section

The Dazhu section (XQS; 107°06′51.58″E, 30°45′55.98″N) also comprises strata from underlying Leikoupo Group and overlying first and second segments of the Xujiahe Formation. The Leikoupo Group is mainly exposed as calcitic dolomite with interbeds of dolomitic shale. The first segment of the Xujiahe Formation is exposed as argillaceous siltstone with interbeds of carbonaceous mudstone (Fig. 2).

The T3x2 in this section is approximately 160 m thick and can be divided into two parts. The lower part (0–130 m) contains multiple interbedded sandstone and mudstone units, with lithologies of medium- to coarse-grained feldspathic quartz sandstone, fine- to medium-grained lithic quartz sandstone, argillaceous siltstone and carbonaceous mudstone. The upper part (130–160 m) is mainly composed of carbonaceous mudstone. Four samples were collected from different layers of the lower part, which are fine-to medium-grained lithic quartz sandstones, with poor to medium sorting, poor roundness, and grain sizes of 0.1–0.5 mm (Fig. 3e). Microscopic examination reveals a composition of quartz (~ 65%), feldspar (10–15%), lithic fragments (∼20%) and interstitial material (~ 5%). The quartz predominantly appears as single-crystal quartz, the feldspar is mainly K-feldspar with minor microcline, and the lithic fragments are mainly mudstone, siltstone, andesite, tuff and phyllite. The interstitial materials are primarily argillaceous and silty (Fig. 3f).

Analytical methods

Whole-rock major and trace element analysis

Whole-rock major and trace element analyses were performed at ALS Chemex (Guangzhou, China). The samples were pulverized until they were fine enough to pass through a 200 mesh. Major element concentrations were determined using a Panalytical Axios Max X-ray fluorescence (XRF) instrument, achieving an analytical accuracy of 1–5%. For trace element analysis, an inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometer (ICP-MS; PerkinElmer Elan 9000) was employed, offering an analytical accuracy better than 5%. More details about the analytical methods are provided by Qiu et al.21 and Zhang et al.22.

Detrital zircon geochronology

The separation of zircon grains was carried out using standard magnetic and heavy liquid methods at Langfang Integrity Geological Services Co., Ltd. The grains were then meticulously selected under a binocular microscope. To minimize any risk of contamination, the mineral separation laboratory maintains a clean, dust-free environment. After each use, the pulverizer and ore beneficiation equipment were thoroughly washed with water and then air-dried for 15–30 min to eliminate any residual particles. The zircon grains were subsequently embedded in epoxy resin blocks and polished to achieve flat surfaces. For visualizing the internal structure of the zircon grains, cathodoluminescence (CL) imaging was performed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) at Chongqing Yujing Science and Technology Services Co. Ltd.

U–Pb geochronology of zircon was conducted using laser ablation inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) at Nanjing FocuMS Technology Co., Ltd. The setup included a Teledyne Cetac Technologies Analyte Excite LA system (Bozeman, USA) and an Agilent 7700 × quadrupole ICP-MS (Tokyo, Japan). The 193-nm ArF excimer laser, homogenized by a beam delivery system, was focused on the zircon surface with a fluence of 6.0 J/cm−2. The ablation process involved a 35 μm spot diameter, at an 8 Hz repetition rate for 40 s (~ 320 pulses). Helium was used as a carrier gas to efficiently transport the aerosol to the ICP-MS. Zircon 91,500 served as the external standard for correcting instrumental mass bias and elemental fractionation, while Zircon GJ-1 was used as secondary standard for quality control. Calibration of lead and other trace elements in zircon was performed against NIST SRM 610 glass (with Si as the internal standard), following the methodologies of Liu et al. and Hu et al.23,24 Raw data reduction was performed offline using ICPMSDataCal software. Quantitative calibration for Pb isotope dating was performed by ComPbcorr#3_1825, and Concordia diagrams and weighted mean calculations were generated using ISOPLOT 4.1526.

Zircon Lu–Hf isotope analysis

Zircon Lu–Hf isotopic analyses were carried out by LA-MC-ICP-MS at Nanjing FocuMS Technology Co. Ltd. The Teledyne Cetac Technologies Analyte Excite laser-ablation system (Bozeman, Montana, USA) and Nu Instruments Nu Plasma II MC-ICP-MS (Wrexham, Wales, UK) were combined for the experiments. The 193 nm ArF excimer laser, which was homogenized by a set of beam delivery systems, was focused on the zircon surface with fluence of 6.0 J/cm2. The ablation protocol employed a spot diameter of 50 μm at an 8 Hz repetition rate for 40 s (equating to 320 pulses). Helium was applied as a carrier gas to efficiently transport the aerosol to MC-ICP-MS. Two standard zircons (GJ-1 and 91,500) were treated as the quality control every ten unknown samples.

Clastic particle composition statistics

The detrital framework composition of the collected samples was analyzed using the Gazzi-Dickinson point counting method27. In this method, three straight lines were drawn across each thin section, and about 500 grains (with diameters between 0.2 and 2 mm) intersecting these lines were counted and classified as quartz, feldspar, or lithic fragments. To ensure accuracy and statistical significance, approximately 500 points were counted per sample. Samples with a high concentration of carbonate or those comprising more than 25% matrix and cement were excluded from the counts. However, grains affected by metasomatism were included in the counts, based on their remaining clastic components.

Results

Whole-rock major and trace elements

Sixteen representative samples (3 from GS, 8 from XQS, and 4 from DS), were selected for comprehensive whole-rock geochemical analysis (Supplementary Table 1). The GS samples exhibit high SiO2 (83.43–83.57 wt%) and Al2O3 (7.86–8.23 wt%), with low MgO (0.47–0.51 wt%), Fe2O3 (1.79–2.28 wt%), CaO (0.13–0.22 wt%) and Na2O (0.38–0.80 wt%), but moderate K2O (2.26–2.37 wt%) contents. The XQS samples also show high SiO2 (74.00–86.58 wt%) and Al2O3 (6.50–9.26 wt%), with variable MgO (0.42–1.59 wt%), Fe2O3 (0.89–3.39 wt%) and CaO (0.25–2.53 wt%), and moderate Na2O (0.74–1.13 wt%) and K2O (2.30–3.39 wt%) composition. Similarly, the DS samples have high SiO2 (82.01–87.03 wt%) and Al2O3 (6.04–8.66 wt%), but low MgO (0.32–0.49 wt%), Fe2O3 (1.13–2.04 wt%), CaO (0.16–0.25 wt%) and Na2O (0.30–0.48 wt%), and moderate K2O (2.87–3.69 wt%) concentrations. On a log (SiO2/Al2O3)–log (Na2O/K2O) diagram, the GS and XQS samples predominantly fall within the arkose to subarkose fields, whereas the DS samples plot chiefly in the arkose field. On a log (SiO2/Al2O3)–log (Fe2O3/K2O) diagram, the XQS samples fall mainly in the litharenite, arkose and subarkose fields; the GS samples plot in the arkose field; while the DS samples lie in the arkose and subarkose fields (Fig. 4a, b).

Samples from the GS, XQS and DS have similar trace element distribution patterns in both primitive mantle- and upper crust- normalized diagrams. They show slight enrichment in Th, U, La, Ce, Nd, Zr and Hf, and moderate depletion in Nb, Ta, Sr, P and Ti (Fig. 5b, d). Additionally, they are characterized by a high concentration of rare earth elements (REEs), with a particular enrichment in light REEs compared to heavy REEs when normalized to C1 chondrite. The REE distribution patterns typically show a right-dipping shape in chondrite normalized diagram, coupled with slight negative Eu anomalies (Fig. 5a). However, they show a relatively flat shape in the upper crust- normalized diagram, without Eu anomalies (Fig. 5c).

(a) Chondrite-normalized REEs distribution patterns of sandstone samples; (b) Primitive mantle-normalized trace element spider diagram; (c) Upper crust-normalized REE distribution patterns of sandstone samples; (d) Upper crust-normalized trace element spider diagrams. Normalizations are taken after Taylor and McLennan30 and Sun and McDonough31.

Zircon U–Pb ages

One representative sample from each section (GS, XQS and DS) was selected for zircon U–Pb dating. The dating results are provided in Supplementary Table 2, and the zircon CL images and age distributions are shown in Fig. 6.

In sample GJG3 (GS section), 70 zircons were randomly chosen for U–Pb isotopic analyses. Among these, 65 yielded consistent and concordant data. The determined ages of these zircons vary widely, ranging between 237 and 2606 Ma. Notably, two distinct age peaks are evident at 2000–1800 Ma and 500–200 Ma (Fig. 7a, b).

From sample QLG2 of the XQS, 70 zircons were randomly chosen for U–Pb isotopic analysis. Among these, 65 zircons provided concordant results. The age range of these zircons extends from 237 to 2606 Ma, with prominent age peaks primarily occurring at 2000–1800 Ma and 500–200 Ma (Fig. 7c, d).

In the case of sample DZG4 from the DS, a total of 70 zircons were selected at random for U–Pb isotopic analyses. From this selection, 70 zircons yielded consistent and reliable data. The age range for these zircons spans from 242 to 2548 Ma, with the most pronounced age peaks occurring at 2000–1800 Ma and 500–200 Ma (Fig. 7e, f).

Zircon Lu–Hf isotopes

The LA-MC-ICP-MS analytical results of detrital zircon Lu–Hf isotope compositions are presented in Supplementary Table 3 and Fig. 8. In sample GJG3 (GS), twelve detrital zircons with ages ranging from 1861 to 2594 Ma were analyzed, yielding εHf(t) values between − 5.1 and + 4.4 and two-stage model ages (TDM2) between 2571 and 3276 Ma. In sample QLG2 (XQS), twenty-three detrital zircons with ages of 1850–2557 Ma were examined, showing εHf(t) values from − 10.0 to + 5.4 and TDM2 ages ranging from 2664 to 3115 Ma. In sample DZG4 (DS), fourteen detrital zircons with ages of 1865–2550 Ma were analyzed, yielding εHf(t) values from − 7.4 to + 4.9 and TDM2 ages ranging from 2422 to 3451 Ma.

Detrital zircon εHf(t) vs t (Ma) diagram of sandstone samples from five sections of the T3x2. The colorful fields represent detrital zircons from different Blocks (after Liao et al.32). Abbreviations: NCB-North China Block; NQB-North Qinling Block; SQB-South Qinling Block; YB-Yangtze Block.

Additionally, detrital zircon Hf isotope analyses were conducted on two further sections from the T3x2 unit, namely the WSS (Wanyuan Shiguansi Section) and TNES (Tongjiang Nuoshuihe Erpingcun Section), for comparative purposes. At WSS, two samples (WYG2 and WYG3) were examined. Sample WYG2 yielded data from twenty-four detrital zircons with ages between 758 and 1933 Ma, recording εHf(t) values from –17.9 to + 5.8 and TDM2 ranging from 1351 to 3641 Ma. In contrast, sample WYG3 produced results from twenty zircons with ages of 707–3455 Ma, exhibiting εHf(t) values from − 29.0 to + 4.1 and TDM2 ages between 1452 and 4082 Ma. At TNES, two samples (TJG1 and TJG2) were analyzed. Sample TJG1 yielded eleven zircons with ages of 1847–1906 Ma, showing εHf(t) values from − 13.7 to + 31.2 and TDM2 ages of 542–3364 Ma. Sample TJG2 contained seven zircons with ages of 1854–1924 Ma, recording εHf(t) values from − 19.4 to + 24.2 and TDM2 ages of 1013–3706 Ma.

Clastic particle composition

Point-counting results of detrital grain compositions are presented in Supplementary Table 4. Three samples from the GS are dominated by quartz (73–81%, avg. 77%), with subordinate feldspars (7–10%, avg. 8%) and lithic fragments (12–19%, avg. 15%). Within the lithic fraction, sedimentary fragments are most abundant (37–65%, avg. 52%), followed by metamorphic (15–37%, avg. 25%) and volcanic components (17–27%, avg. 23%). Nineteen samples from the XQS exhibit similar characteristics, with quartz contents of 59–81% (avg. 71%), feldspars of 7–20% (avg. 14%), and lithic fragments of 9–21% (avg. 16%). Among the lithics, sedimentary fragments dominate (27–63%, avg. 52%), followed by volcanic (16–41%, avg. 29%) and metamorphic types (11–47%, avg. 18%). Four samples from the DS are also quartz-rich (68–71%, avg. 69%), with feldspars ranging from 10–16% (avg. 14%) and lithic fragments from 14–21% (avg. 17%). In these lithics, sedimentary fragments constitute the largest proportion (49–58%, avg. 54%), followed by volcanic (16–33%, avg. 24%) and metamorphic fragments (18–26%, avg. 22%).

Discussion

Depositional environment and ages

The lower part of the T3x2 in all three sections is predominantly composed of thick sandstone beds with variable grain sizes and interlayers. At the base, the sandstones commonly display irregular erosional surfaces containing gravels, which gradually decrease in abundance, grain size, and bed thickness upward. Well-developed sedimentary structures, including both cross-bedding and parallel bedding, are frequently observed intergrown within these sandstones. Parallel bedding is typically associated with high-energy river channel deposits, where sediment-laden flows migrate across the channel floor. The continuous rolling and sorting of grains under strong hydrodynamic conditions lead to gravity-driven segregation of coarse and fine particles, producing thin horizontal laminae that are relatively loose and prone to slippage33. Cross-bedding, on the other hand, results from frequent lateral migration of braided distributary channels, with rapidly shifting flow directions producing high-frequency, inclined stratification34. The large-scale intergrowth of cross- and parallel-bedding therefore reflects highly variable hydrodynamic conditions within braided distributary river channels on delta plains, indicating that the lower T3x2 was deposited in such an environment.

The upper part of the T3x2 is distinguished by widespread soft-sediment deformation structures, including convolute bedding and slump structures. Convolute bedding is interpreted to result from sediment liquefaction during deposition, with shear stress from flowing water or downslope gravity-driven movement inducing folding of primary stratification35. Slump structures formed as entire sediment packages were displaced downslope under gravitational forces. These features, together with the presence of inverted structures and thick, grey, sheet-like sandstones (observed in the upper part of the T3x2), are characteristic of rapid deposition under turbulent hydrodynamic conditions in braided-river estuary bars on delta fronts.

Because sediment deposition postdates the crystallization of detrital zircons, U–Pb dating of detrital zircons constrains the maximum depositional ages of the sedimentary sequences. In the GS section, sample GJG3 yielded a youngest coherent group of five zircons with an average age of 253.3 Ma. In the XQS section, sample QLG2 produced a youngest group of eight zircons averaging 260.1 Ma, while in the DS section, sample DZG4 yielded eight zircons with an average age of 267.0 Ma. Collectively, these data indicate a maximum depositional age of 253.3 Ma. This youngest Permian age is slightly older than the actual deposition, implying that 253.3 Ma is only a maximum age constraint. Deposition of the T3x2 occurred after this time (i.e., during the Triassic). Many published articles have proved that the youngest detrital zircon ages from the Xujiahe Formation are around 230–200 Ma3,6,7,8, especially a tuff interbedded with Member 5 of the Xujiahe Formation strata obtained 212 Ma in age (Jiang et al.7), which strongly proved the Late Triassic depositional age of the Xujiahe Formation. Moreover, some Late Triassic biological fossils are also discovered in the Xujiahe Formation, such as Archosaur (the earliest dinosaur tracks in China)36. Based on these evidences, we consider that the Xujiahe Formation is interpreted as a Late Triassic (Norian–Rhaetian) continental sequence; accordingly, we assign the T3x2 to a Late Triassic depositional age.

Source rock features

The geochemical composition of the studied sandstones reflects the influence of source rock composition, paleo-weathering, and sedimentary recycling. These signatures can be evaluated both quantitatively and qualitatively through the geochemical characteristics of the sedimentary rocks. Among the most widely applied parameters is the Chemical Index of Alteration37 (CIA), which assesses the relative proportions of stable feldspars and mafic minerals to clay minerals, thereby serving as an effective measure of paleo-weathering intensity. Fresh, unweathered magmatic rocks typically display CIA values of ~ 40–50, whereas intense chemical weathering may increase values toward 10038,39. In this study, CIA values for eight sandstone samples from the XQS range from 59 to 67, four sandstone samples from the DS range from 65 to 72, and three sandstone samples from the GS range from 70 to 74. These results suggest a progressive increase in paleo-weathering intensity, from relatively weak weathering in the XQS sandstones, to moderate levels in the DS, and the highest degree in the GS sandstones.

Another useful indicator of paleo-weathering intensity is the relative abundance of clay minerals, as increasing proportions of kaolinite and illite are typically associated with more advanced chemical weathering37. Such mineralogical changes are accompanied by systematic geochemical variations, which can be effectively illustrated on the Al2O3–(Na2O + CaO)–K2O ternary diagram (Fig. 9a). In this diagram, weathering trends are expressed as Al2O3–(Na2O + CaO) parallel regression lines, which can be used to track the composition of the original source rocks37,38. In this study, sandstone samples from the GS, XQS, and DS plot to the right of the granite weathering trend line, with the exception of a single XQS sample. This distribution suggests that granitic rocks represent the dominant source for these sandstones.

To better constrain the source rock signatures, trace element compositions provide a reliable tool, as these elements are relatively immobile during erosion, transport, and diagenesis30,42,43. In this study, sandstone samples from the GS, XQS, and DS show low La/Th ratios and variable Hf contents (Fig. 9b). The DS samples predominantly plot within the andesitic arc and mixed felsic/mafic source fields, the XQS samples cluster in the andesitic arc, felsic, and mixed felsic/mafic fields, while the GS samples lie mainly in or adjacent to the mixed felsic/mafic and felsic source fields.

REEs systematics provide further insights into provenance. The samples are characterized by high ∑LREE/∑HREE ratios (10.78–22.72) and pronounced negative Eu anomalies, with Eu/Eu* values ranging from 0.59 to 0.82, as shown in chondrite-normalized REE diagrams (Fig. 5). These features are typical of felsic source compositions30,44, on the Eu/Eu* versus Th/Sc diagram (Fig. 9c), all samples plot within the unevolved to evolved felsic source fields, confirming their derivation from felsic provenance.

Geochemical ratios further support this interpretation. Elevated La/Sc (5.43–10.67), Th/Cr (0.20–0.49), Th/Co (0.91–2.49), and Th/Sc (1.02–2.10) ratios align these sandstones with the chemical signatures of upper continental crust and siliceous sandstones, distinguishing them from lower crustal, oceanic crustal, or mafic sandstone compositions45. Moreover, discrimination diagrams such as SiO₂–Zr/Sc, Zr/Sc–Th/Sc, Rb–K₂O, and La/Sc–Co/Th (Fig. 10) consistently place the samples within the fields of quartz-rich sandstones and mudstones, upper crustal sources with multiple recycling episodes, intermediate–acidic rocks, and felsic rocks. Collectively, these geochemical features strongly indicate that the primary source rocks of the GS, XQS, and DS sandstones were predominantly upper crustal felsic rocks.

Detrital zircon provenance

Detrital zircon records provide a robust tool for constraining sediment provenance and tracing crustal evolution of source terranes. Because recycled sediments can yield detritus with similar bulk chemical compositions, precise source discrimination requires integration of detrital zircon geochronology and isotope geochemistry48,49,50. In this study, detrital zircons extracted from the GS, XQS, and DS sandstones display similar age distributions with shared peaks at ~ 2500 Ma, ~ 1800 Ma, and 500–200 Ma (Fig. 11), suggesting a broadly mixed provenance with variable contributions. Previous work has proposed that the T3x2 was deposited in the Late Triassic, with potential sediment contributions from the Qinling Orogenic Belt, Songpan–Ganzi Terrane, North China Block, and Yangtze Block.

The Yangtze Block is characterized by detrital zircon age peaks at ~ 2500 Ma, 2000–1800 Ma, and ~ 800 Ma (Fig. 11). The 2500 Ma and 1800 Ma peaks correlate well with the T3x2 spectra; however, the absence of the ~ 800 Ma peak in most samples, together with the prominent 500–200 Ma peak, indicates that the Yangtze Block alone cannot account for the full provenance. Similarly, the North China Block exhibits major peaks at ~ 2500 Ma, ~ 2300 Ma, ~ 1800 Ma, ~ 450 Ma, and ~ 270 Ma. While several of these match the T3x2 distributions, the 2300 Ma peak is absent, and the geographic separation of the North China Block from the depositional setting further weakens its role as a direct source.

The Songpan–Ganzi Terrane displays detrital zircon peaks at ~ 2500 Ma, ~ 1850 Ma, ~ 800 Ma, and 450–260 Ma (Fig. 11). The 2500 Ma, 1800 Ma, and 450–260 Ma peaks correspond well with the T3x2 spectra, and the minor ~ 800 Ma peak may explain the small zircon population in that range. However, lithic fragment compositions and zircon Hf isotopes show inconsistencies with a direct Songpan–Ganzi source16,51,52, implying instead that this terrane may have contributed indirectly through sedimentary recycling. The Qinling Orogenic Belt provides a more plausible contributor. The North Qinling segment shows zircon peaks at ~ 2500 Ma, 900–750 Ma, 400 Ma, and ~ 200 Ma, whereas the South Qinling segment records peaks at ~ 2500 Ma, ~ 750 Ma, and ~ 450 Ma (Fig. 11). Both belts, however, lack a distinct 1800 Ma peak, and instead display additional peaks (~ 900 Ma and ~ 750 Ma) that are weak or absent in the T3x2 spectra.

Taken together, these data indicate that the T3x2 sediments cannot be attributed to a single terrane, but instead reflect a mixed provenance. The most consistent explanation is a combination of sources from the Qinling Orogenic Belt and the Yangtze Block, with possible minor input from recycled Songpan–Ganzi material. This interpretation is further supported by zircon age–εHf(t) systematics: detrital zircons from five T3x2 sections (GS, XQS, DS, WSS, TNES) show age peaks and εHf(t) values broadly consistent with those of the South Qinling Belt and the Yangtze Block (Fig. 8).

The sedimentological framework also corroborates this provenance model. Previous studies have suggested that the Xujiahe Formation (T3x2) represents a braided river delta system located at the junction of the Qinling Orogenic Belt and Yangtze Block, where major paleorivers transported sediments southward to form littoral deltas along the Paleo-Tethys margin3,16. In the eastern regions, additional river systems flowing east–west further imply sediment supply from both the Yangtze Block and the adjacent orogenic belts, reinforcing the interpretation of a multi-sourced depositional system for the T3x2 Formation.

Tectonic settings

Sandstone samples from the GS, XQS, and DS are characterized by high quartz contents, low proportions of feldspar and lithic fragments, and a dominance of sedimentary fragments within the lithic fraction. Such mineralogical assemblages typically indicate derivation from recycled crustal sources54,55,56. This interpretation is supported by Qt–F–L, Qm–F–Lt, and related ternary diagrams (Fig. 12a–d), where the samples consistently plot within the recycled orogen field, more specifically within the quartzose recycled subfield. This suggests that the sediments were mainly derived from an orogenic tectonic setting, consistent with erosion of the Qinling Orogenic Belt. Additional support is provided by Qp–Lv–Ls and Qm–P–K diagrams (Fig. 12e, f), in which the samples plot within fields of mixed orogenic and continental derivation, further reinforcing the Qinling provenance.

Trace-element discrimination diagrams provide complementary evidence. In La–Th–Sc, Th–Sc–Zr/10, Th–Co–Zr/10, and Ti/Zr–La/Sc plots (Fig. 13), the sandstones fall primarily within passive margin and secondary continental island arc fields, suggesting that the Qinling source underwent tectonic transition from an active continental island arc to a passive margin setting. This inference is corroborated by major-element discrimination diagrams (K2O/Na2O–SiO2/Al2O3, Fe2O3 + MgO–TiO2, SiO2–K2O/Na2O, and Fe2O3 + MgO–Al2O3/SiO2; Fig. 14), where the samples consistently fall within passive margin fields, indicating that the sedimentary detritus derived from the Qinling Orogenic Belt was deposited under long-lived passive margin conditions. This suggests that although the Qinling Belt was tectonically active during the Triassic, the Sichuan Basin acted as a foreland basin with passive-margin characteristics during deposition, allowing sediment from the active orogen to accumulate under relatively stable conditions.

Tectonic discrimination diagrams of (a) La–Th–Sc; (b) Th–Sc–Zr/10; (c) Th–Co–Zr/10; (d) Ti/Zr–La/Sc. Fields are after Roser and Korsch57. Abbreviation: PM-passive margin, ACM-active continental margin, CIA-continental island arc, OIA-oceanic island arc.

Tectonic discrimination diagrams of (a) K2O/Na2O vs. SiO2/Al2O3; (b) Fe2O3 + MgO vs. TiO2; (c) SiO2 vs. K2O/Na2O; (d) Fe2O3 + MgO vs. Al2O3/SiO2. Fields are after Bhatia60 PM-passive margin, ACM-active continental margin, CIA-continental island arc, OIA-oceanic island arc.

From a geodynamic perspective, the study area formed part of a foreland basin during the Late Triassic6,13,58. At this time, the Paleo-Tethys Ocean was closing in a scissor-like fashion from east to west39,59. Along the eastern margin, the Yangtze and North China blocks had already amalgamated along the Qinling Orogenic Belt, while the western part of the Paleo-Tethys remained as a gulf system. Numerous paleorivers drained into this gulf, constructing extensive braided river delta plains. The study area was located at the northeastern corner of this gulf, where multiple NE–SW-trending paleorivers transported abundant detritus from the Qinling Orogenic Belt and Yangtze Block. This continuous supply of sediments ultimately led to the accumulation of the exceptionally thick Xujiahe Formation (Fig. 15).

Conclusions

This study integrates stratigraphic, petrographic, whole-rock geochemistry, and detrital zircon U–Pb–Hf isotopic data to constrain the depositional age, provenance, and tectonic setting of the second member (T3x2) of the Xujiahe Formation in the northeastern Sichuan Basin. The results indicate that these sandstones were deposited during the Late Triassic in a braided river delta environment, as evidenced by their sedimentary structures, grain-size variations, and facies architecture. Whole-rock geochemistry and CIA values suggest a low degree of paleo-weathering, with source rocks dominated by upper-crustal felsic lithologies.

Detrital zircon geochronology reveals distinct age populations at ~ 2.5 Ga, 1.8–2.0 Ga, and 500–200 Ma, reflecting mixed provenances. Comparison with zircon age spectra from adjacent tectonic blocks demonstrates that both the Qinling Orogenic Belt and the Yangtze Block were the principal sources of detritus, with additional recycling contributions from older sediments. Zircon Hf isotopic data further confirm derivation from upper continental crustal sources, consistent with felsic provenance signatures in trace-element systematics.

Tectonic discrimination diagrams consistently point to a passive margin depositional setting, following an earlier arc-related phase. The Xujiahe basin was positioned at the southern flank of the Qinling Orogenic Belt during the final stages of Paleo-Tethys closure, with several paleo-rivers transporting sediments southwestward into a foreland basin.

Collectively, these results provide robust constraints on the timing, provenance, and tectonic evolution of the Xujiahe Formation. The findings not only resolve long-standing debates regarding its depositional age and source terranes but also contribute to a better understanding of Late Triassic basin evolution in South China.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Liu, J. et al. Geological characteristics and models of fault-fold-fracture body in deep tight sandstone of the second member of Upper Triassic Xujiahe Formation in Xinchang structural belt of Sichuan Basin SW China. Petrol. Explor. Dev. 50(3), 603–614 (2023).

Cai, W. et al. Developmental characteristics of fractures in deep tight sandstone reservoirs in the second Member of the Xujiahe Formation of Zhongjiang Gas Field. Unconv. Resour. 4, 100073 (2024).

Xie, F. et al. Tectonic evolution of the northeastern paleo-tethys ocean during the late triassic: Insights from depositional environment and provenance of the Xujiahe formation. Front. Earth Sci. 12, 1444679 (2024).

Liao, T., Hu, J., Zhang, F. & Liu, L. Reconsideration of the sediment characteristics of the second member of the Triassic Xujiahe Formation in Sanhuiba Huaying mountain. Min. Sci. Technol. 20(4), 591–599 (2010).

Yu, S. H. & Liang, X. Q. Provenance of the Xujiahe group of late Triassic in the Western Sichuan Basin: Evidence from detrital zircon U-Pb ages. Sci. Technol. Eng. 17(4), 13–24 (2017) (In Chinese with English abstract).

Mu, H. et al. Formation of the late Triassic western Sichuan foreland basin of the Qinling Orogenic Belt, SW china: Sedimentary and geochronological constraints from the Xujiahe Formation. J. Asian Earth Sci. 183, 103938 (2019).

Jiang, Z. et al. A Late Triassic depositional age for the Xujiahe formation, Sichuan basin: Implications for the closure of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean. Mar. Pet. Geol. 155, 106346 (2023).

Gou, M. et al. Tectonic–paleogeographic evolution of the Late Triassic in the Sichuan basin, SW China: Constraints from sedimentary facies and provenance analysis of the Xujiahe Formation. Mar. Pet. Geol. 160, 106649 (2024).

Huang, Y. et al. Analysis of lithofacies and evaluation of effective reservoirs of member 2 of Xujiahe Formation in the Xinchang area in Western Sichuan. Petrol. Res. 5(3), 244–253 (2020).

Liu, J., Liu, Z., Xiao, K., Huang, Y. & Jin, W. Characterization of favorable lithofacies in tight sandstone reservoirs and its significance for gas exploration and exploitation: A case study of the 2nd Member of Triassic Xujiahe Formation in the Xinchang area Sichuan Basin. Petrol. Explor. Dev. 47(6), 1194–1205 (2020).

Yang, P. et al. Diagenetic history and reservoir evolution of tight sandstones in the second member of the Upper Triassic Xujiahe Formation, western Sichuan Basin, China. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 201, 108451 (2021).

Zhou, G., Wei, G. & Hu, G. The geochemical and organic petrological characteristics of coal measures of the xujiahe formation in the sichuan basin, china. Energy Explor. Exploit. 37(3), 1–18 (2019).

Deng, J. et al. Controlling factors of tight sandstone gas accumulation and enrichment in the slope zone of foreland basins: The upper triassic Xujiahe Formation in Western Sichuan Foreland Basin, China. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 214, 110474 (2022).

Li, S. L. et al. Crustal growth event in the Cathaysia Block at 2.5 Ga: Evidence from chronology and geochemistry of captured zircons in Jurassic acidic dykes. Geol. Mag. 158, 567–582 (2021).

Xiao, W. et al. Long-lasting magmatic, metamorphic events in the cathaysia block: Insights from the geochronology and geochemistry of inherited zircons in Jurassic a-type granites. Minerals 14(2), 1247 (2024).

Gong, D. X. et al. Provenance analysis of late Triassic turbidites in the eastern Songpan-Ganzi flysch complex: Sedimentary record of tectonic evolution of the eastern Paleo-Tethys ocean. Mar. Pet. Geol. 126(1), 104927 (2021).

Yuan, D. et al. Zircon Geochronology and geochemistry of the taohualing pluton in Northern Dabieshan and their tectonic implications. J. Xinyang Normal Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 35(1), 97–102 (2022) (In Chinese with English abstract).

Li, Z. et al. Provenance transition of the Mesoproterozoic-Neoproterozoic Xuhuai Basin: Constraining the accretion of the Northern Qinling Terrane with the North China Craton. J. Asian Earth Sci. 251, 105675 (2023).

Zi, F. et al. Understanding the genesis of ore-bearing and ore-barren adakitic rocks: insights from geochronology and geochemical analysis of the Tuncang intrusion and enclaves along the South Tan-Lu Fault. Int. J. Earth Sci. 113, 1579–1598 (2024).

Zhang, L. Y. et al. Age and geochemistry of western Hoh-Xil–Songpan-Ganzi granitoids, northern Tibet: Implications for the Mesozoic closure of the Paleo-Tethys ocean. Lithos 190–191, 328–348 (2014).

Qiu, L. et al. Early to Middle Triassic sedimentary records in the Youjiang Basin, South China: Implications for Indosinian orogenesis. J. Asian Earth Sci. 141(15), 125–139 (2017).

Zhang, L. et al. Late Cretaceous granitic magmatism and mineralization in the Yingwuling W-Sn deposit, South China: Constraints from zircon and cassiterite U–Pb geochronology and whole-rock geochemistry. Ore Geol. Rev. 96, 115–129 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Continental and oceanic crust recycling-induced melt-peridotite interactions in the trans-North china orogen: U-Pb dating, Hf isotopes and trace elements in zircons from mantle xenoliths. J. Petrol. 51(51), 392–399 (2010).

Liu, Y. S. et al. Reappraisement and refinement of zircon U-Pb isotope and trace element analyses by LA-ICP-MS. Sci. Bull. 55(15), 1535–1546 (2010).

Andersen, T. Correction of Common Lead in U-Pb Analyses that do not Report 204Pb. Chem. Geol. 192(1/2), 59–79 (2002).

Ludwig, K.R., User’s Manual for Isoplot 3.00: A Geochronological Toolkit for Microsoft Excel. Berkeley: Berkeley Geochronology Center, Special Publication no. 4. (2003).

Ingersoll, R. V., Bullard, T. F., Ford, R. L., Grimm, J. P. & Sares, S. W. The effect of grain size on detrital modes: A test of the gazzi-dickinson point-counting method (holocene, sand, new mexico, usa). J. Sediment. Petrol. 54(1), 103–116 (1984).

Pettijohn, F. J., Potter, P. E. & Siever, R. Sand and Sandstone (Springer, 1972).

Herron, M. M. Geochemical classification of terrigenous sands and shales from core or log data. J. Sediment. Petrol. 58, 820–829 (1988).

Taylor, S. R. & McLennan, S. M. The Continental Crust: its Composition and Evolution (Blackwell, 1985).

Sun, S. S. & McDonough, W. F. Chemical and Isotopic Systematics of Oceanic Basalts: Implications for Mantle Composition And Processes. In Magmatism in the Ocean Basins Vol. 42 (eds Saunders, A. D. & Norry, M. J.) 313–345 (London, Special Publications, Geological Society, 1989).

Liao, X. Y., Wang, Y. W., Liu, L., Wang, C. & Santosh, M. Detrital zircon U-Pb and Hf isotopic data from the Liuling Group in the South Qinling belt: Provenance and tectonic implications. J. Asian Earth Sci. 134, 244–261 (2017).

Chen, Y., Zhang, Z., Li, K., Li, Q. & Luo, Z. Provenance of the Middle Permian Zhesi Formation in central Inner Mongolia, northern China: Constraints from petrography, geochemistry and detrital zircon U-Pb geochronology. Geol. J. 52, 92–109 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. Geochemistry and zircon U-Pb–Hf isotopic data for Permo-Carboniferous sediments in the Solonker Zone, Inner Mongolia, China: Constraints on depositional age, provenance and tectonic setting. J. Geol. Soc. 175, 3948325 (2018).

Chen, Y., Wu, T., Gan, L., Zhang, Z. & Fu, B. Provenance of the early to mid-Paleozoic sediments in the northern Alxa area: Implications for tectonic evolution of the southwestern Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Gondwana Res. 67, 115–130 (2019).

Li, M. et al. Astronomical tuning and magnetostratigraphy of the Upper Triassic Xujiahe Formation of South China and Newark Supergroup of North America: Implications for the Late Triassic time scale. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 475(1), 207–223 (2017).

Nesbitt, H. W. & Young, G. M. Prediction of some weathering trends of plutonic and volcanic rocks based on thermodynamic and kinetic considerations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 48, 1523–1534 (1984).

Li, Q. G. et al. Contrasting provenance of Late Archean metasedimentary rocks from the Wutai Complex, North China Craton: Detrital zircon U-Pb, whole-rock Sm-Nd isotopic, and geochemical data. Int. J. Earth Sci. 97, 443–458 (2008).

Fathy, D., Baniasad, A., Littke, R. & Sami, M. Tracing the geochemical imprints of Maastrichtian black shales in southern Tethys, Egypt: Assessing hydrocarbon source potential and environmental signatures. Int. J. Coal Geol. 283, 104457 (2024).

Floyd, P. A. & Leveridge, B. E. Tectonic environment of the Devonian Gramscatho basin, south Cornwall: Framework mode and geochemical evidence from turbiditic sandstones. J. Geol. Soc. 144(4), 531–542 (1987).

Jorge, R. C. G. S., Fernandes, P., Rodrigues, B., Pereira, Z. & Oliveira, J. T. Geochemistry and provenance of the Carboniferous Baixo Alentejo Flysch Group, South Portuguese Zone. Sed. Geol. 284–285, 133–148 (2013).

McLennan, S. M. & Taylor, S. R. Geochemistry of Archean metasedimentary rocks from West Greenland. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 48, 1–13 (1984).

McLennan, S. M., Hemming, S., McDaniel, D. K. & Hanson, G. N. Geochemical approaches to sedimentation, provenance, and tectonics. Geol. Soc. Am. Spec. Pap. 284, 21–40 (1993).

Cullers, R. L. The controls on the major- and trace-element evolution of shales, siltstones and sandstones of Ordovician to Tertiary age in the Wet Mountains region, Colorado, U.S.A. Chem. Geol. 123, 107–131 (1995).

Gu, X. X., Liu, J. M., Zheng, M. H., Tang, J. X. & Qi, L. Provenance and tectonic setting of the Proterozoic turbidites in Hunan, south China: Geochemical evidence. J. Sediment. Res. 72(3), 393–407 (2002).

Cingolani, C. A., Manassero, M. & Abre, P. Composition, provenance and tectonic setting of Ordovician siliciclastic rocks in the San Rafael block: Southern extension of the Precordillera crustal fragment, Argentina. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 16(1), 91–106 (2003).

Spalletti, L. A., Queralt, I., Matheos, S. D., Colombo, F. & Maggi, J. Sedimentary petrology and geochemistry of siliciclastic rocks from the upper Jurassic Tordillo Formation (Neuquén Basin, western Argentina): Implications for provenance and tectonic setting. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 25(4), 440–463 (2008).

Hawkesworth, C. J. & Kemp, A. I. S. Using hafnium and oxygen isotopes in zircons to unravel the record of crustal evolution. Chem. Geol. 226, 144–162 (2006).

Kemp, A. I. S., Hawkesworth, C. J., Paterson, B. A. & Kinny, P. D. Episodic growth of the Gondwana supercontinent from hafnium and oxygen isotopes in zircon. Nature 439, 580–583 (2006).

Gehrels, G. E. Detrital zircon U-Pb geochronology applied to tectonics. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 42, 127–149 (2014).

Tang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Tong, L. Mesozoic-Cenozoic evolution of the Zoige depression in the Songpan-Ganzi flysch basin, eastern Tibetan plateau: Constraints from detrital zircon U-Pb ages and fission-track ages of the Triassic sedimentary sequence. J. Asian Earth Sci. 151, 285–300 (2018).

Zhang, C., Liu, D., Zhang, X., Spencer, C. & Kong, X. Hafnium isotopic disequilibrium during sediment melting and assimilation. Geochem. Perspect. 12, 34–39 (2020).

She, Z.B., Detrital Zircon Geochronology of the Upper Proterozoic-Mesozoic Clastic Rocks in the Mid-Upper Yangtze Region. Wuhan: China University of Geoscience (Phd. Thesis): 1–143. (In Chinese with English abstract) (2007).

Dickinson, W. R. & Suczek, C. A. Plate tectonics and sandstone compositions. Am. Assoc. Petrol. Geol. Bull. 63, 2164–2182 (1979).

Dickinson, W. R. et al. Provenance of North American Phanerozoic sandstones in relation to tectonic setting. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 94, 222–235 (1983).

Dickinson, W. R. Interpreting Provenance Relations from Detrital Modes of Sandstones. In Provenance of Arenites Vol. 148 (ed. Zuffa, G. G.) 333–361 (NATO ASI Series, 1985).

Roser, B. P. & Korsch, R. J. Determination of tectonic setting of sandstone–mudstone suites using SiO2 content and K2O/Na2O ratio. J. Geol. 94(5), 635–650 (1986).

Luo, L. et al. Diagenetic characteristics, evolution, controlling factors of diagenetic system and their impacts on reservoir quality in tight deltaic sandstones: Typical example from the Xujiahe Formation in Western Sichuan Foreland Basin SW China. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 103, 231254 (2019).

Ding, L. et al. Provenance analysis of the Mesozoic Hoh-XilSongpan- Ganziturbidites in northern Tibet: Implications for the tectonic evolution of the eastern paleo-Tethys ocean. Tectonics 32, 34–48 (2013).

Bhatia, M. R. Plate tectonics and geochemical composition of sandstones. J. Geol. 91(6), 611–627 (1983).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the valuable comments and suggestions provided by the anonymous reviewers and the editor, which significantly enhanced the clarity of the manuscript and the interpretation of the data. This research was funded by Ongoing Research Funding program, ORF-2025-1459, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

This research was supported by Ongoing Research Funding program, ORF-2025-1459, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; UPAR funded project of United Arab Emirates University, UAE (12S218); the Talent Introduction and Scientific Research Start-up Funded Project of Northeast Petroleum University (No.2019KQ87); Higher Education Research Project of Heilongjiang Higher Education Association (No.23GJYBJ019); Higher Education Scientific Research Projects of the “14th Five-Year Plan” by the Hebei Higher Education Association (GJXH2024-300) and Qinhuangdao Social Science Development Research Project (2024LX220).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.X. did data collection and analysis, interpretation, writing and editing figures of the main manuscript; M.S., I.S., S.A., L.H. and Y.W. did editing and discussion of the main manuscript; F.X., W.X., M.S. and S.A. provided supervision and funding acquisition. All authors read the article, provided critical feedback and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, F., Xiao, W., Sami, M. et al. Geochemistry and detrital zircon U–Pb–Hf isotopic data reveal the provenance and tectonic setting of the Xujiahe Formation. Sci Rep 15, 45308 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29114-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29114-y