Abstract

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent malignancies worldwide. Modified radical mastectomy, as a conventional treatment for breast cancer, often leads to body image disturbance, which in turn can trigger negative psychosocial changes (such as anxiety, low self-esteem, and social withdrawal) and significantly impairs patients’ long-term quality of life. This study compared the differences in quality of life (QoL) and psychosocial adaptability between patients who underwent modified radical mastectomy and those who received breast reconstruction, with the aim of elucidating the long-term effects of these two surgical procedures on patients’ post-operative physical and mental well-being. Retrospective data were collected from breast cancer patients who underwent modified radical mastectomy or breast reconstruction at our institution between 2014 and 2020, and patients were assigned to the corresponding surgical groups. Propensity score matching was used to balance baseline characteristics (e.g., age, tumor stage, and education level) between the two groups. All included patients completed an online survey, which included the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B, a validated QoL scale with a total score range of 0–144, where higher scores indicate better QoL) and the Psychosocial Adaptation Questionnaire (PAQ, a scale evaluating psychosocial adaptability with a total score range of 0–100, where higher scores indicate stronger adaptability). Statistical analyses were performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (for non-normally distributed data) and two-sample independent t-test (for normally distributed data). A total of 260 matched patients (130 in each group) were included in the final analysis. Compared with the modified radical mastectomy group, the breast reconstruction group showed significantly better outcomes: (1) FACT-B score: the reconstruction group had a mean score of (107.58 ± 16.2), while the mastectomy group had a mean score of (100.18 ± 8.5),P < .01.(2) The total PAQ scores of the two groups were 176 (163,186) and 164 (158,172), respectively, with statistically significant differences (P < .01). Subgroup analysis further confirmed that the advantages of breast reconstruction in QoL and psychosocial adaptability were consistent across patients with different post-operative follow-up periods (< 3 years, 3–5 years, > 5 years). Breast reconstruction was associated with enhanced self-acceptance and self-identity, reduced psychological burden, and improved physical condition, and help them achieve a better quality of life and psychosocial adaptability. These findings provide evidence for optimizing breast cancer treatment decision-making in clinical practice. Healthcare providers (including nurses, surgeons, and psychologists) should fully inform patients of the psychosocial and functional benefits of breast reconstruction, and develop personalized care plans to support patients in selecting surgical options that match their physical conditions and psychological needs, ultimately improving their long-term post-operative recovery outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignant tumor in women and has become a global public health problem. In 2018, its incidence and mortality rates accounted for 11.9% of global cancer cases and 23% of cancer deaths in women, respectively, with a rising incidence in developing countries1,2,3. Breast cancer has become a global public health problem.

Modified radical mastectomy (MRM) is the main surgical treatment modality for breast cancer4. It involves the removal of all mammary glands, including the nipple and areola complex, the pectoralis major fascia, and part of the anterior sheath of the rectus abdominis, which may cause body image disorder. Research has shown that approximately 50%–67% of patients who have undergone MRM develop body image disorder characterized by negative body image, which increases their psychological pain, thus affecting their quality of life (QoL) and psychosocial adaptability5. The loss of breasts also increases the patient’s concern with physical appearance, who thus attempt to hide their body, especially the chest, in their daily lives. Body image disorder directly affects patients’ QoL, social functioning, well-being, sexuality, satisfaction with relationships, and other psychosocial aspects6. Therefore, in recent years, the demand for breast reconstruction (BR) has increased along with increasing attention to the postoperative QoL of breast cancer patients.

BR refers to the process of placing a graft (autologous reconstruction or implant reconstruction) into the defect site after a mastectomy to restore the size and shape of the breast7. It not only retains the treatment effect but also enhances the patient’s self-confidence, enhances their body image and sexual enjoyment, promotes harmony in their family relations, and benefits their psychosocial health, in addition to being feasible and safe8,9,10,11. With improvements in surgical technology and the evolution of social psychology, the importance of BR and its scale after mastectomy has been increasingly recognized in recent years12.

QoL is a comprehensive index that reflects the overall health status of and disease-related changes in individuals and has become a crucial indicator based on which to judge the prognosis of breast cancer patients. An 8-year follow-up study showed significant but fluctuating improvements in QoL during the first 5 years in the BR group and stable QoL and reduced depressive tendencies in the MRM group13. BR was found to be associated with less anxiety and depression than MRM14.

Social adaptability refers to the ability of people to make various adaptive changes during their interactions with other individuals and the environment. Psychosocial adaptability is the ability of individuals to adapt to society psychologically15. In the process of breast cancer treatment and rehabilitation, patients tend to experience fatigue, irritability, memory loss, decreased energy levels, recurring pain, and other symptoms, which affect their psychosocial adaptability as they constantly need to adjust to changes in themselves and it would be helpful to describe how breast treatment changes the patient’s environment16. Research has reported that in breast cancer patients, the overall level of psychosocial adaptation is moderate and positively correlated with their QoL. Therefore, improving the psychosocial adaptation level in this population may be an effective way to improve their QoL17.

Although some studies have compared the QoL of patients who had undergone MRM versus BR, they have often focused on singular outcomes5. However, for breast cancer patients, QoL and psychosocial adaptability are not isolated concepts; impaired psychosocial adaptation often exacerbates declines in QoL, while poor physical QoL can further hinder psychosocial reintegration. To our knowledge, no study has yet compared both QoL and psychosocial adaptability simultaneously between these two surgical groups. Therefore, this study aimed to comparatively investigate the long-term effects of MRM and BR on breast cancer patients, with a focus on the intertwined differences in their QoL and psychosocial adaptability.”

Methods

Theoretical framework

The Roy adaptation model postulates that the life process of the human body is a process of adaptation to various stimuli it receives from its internal and external environments18. Only by constantly adapting to environmental changes can we ensure the health of the body, mind, and society. The theory of cognitive adaptation elaborates the process of an individual’s positive psychological adjustment to stressful events or situations and points out that the degree of adaptation depends greatly on the individual’s capacity for positive appraisal19. After undergoing different surgeries, the psychosocial adaptability of breast cancer patients changes, which affects their QoL.

Study design

We used a cross-sectional study to evaluate the differences in QoL and psychosocial adaptability outcomes between breast cancer patients who had undergone MRM and those who had undergone BR. The study period was September to November 2021. Participants were recruited through convenience sampling from Hunan Cancer Hospital in central China.

Participants and procedures

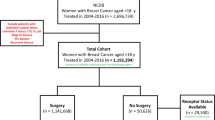

The inclusion criteria were (1) a confirmed diagnosis of stage 0 to 3 breast cancer in a pathological report after surgery, (2) an age of 18 years or older, (3) no recurrence or metastasis before surgery, and (4) consent to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were (1) having undergone bilateral MRM, (2) having other coexisting cancers, (3) a diagnosis of a cognitive disorder or mental disorder, and (4) inability to use smartphone. Of the 1,738 patients who met the study criteria, 1,316 patients agreed to participate in this study and completed all of the surveys (complete rate = 75.7%).We included a large sample initially to ensure coverage of patients with diverse baseline characteristics (e.g., age, tumor stage) — this enhances overall sample representativeness and provides an adequate candidate pool for subsequent bias-reduction analyses, avoiding limitations from a small, homogeneous sample. All questionnaires were administered using online survey methods and Questionnaire Star (www.wjx.cn), an electronic data collection tool. A QR code was generated to give the participants access to the online questionnaires. The patients were divided into MRM (n = 1,178) and BR (n = 138) groups according to the surgical procedure they had undergone. Due to the sample size being remarkably different between the two groups, we performed propensity score matching at a 1:1 ratio (with key baseline variables including age, tumor stage, and educational level as matching factors) to balance confounding variables between groups, ensuring unbiased comparative analysis. Finally, 260 matched participants were included in the study, with 130 patients in each group.

Sample size calculation

G Power 3.1.9.2 software was used to determine the number of participants. For a medium effect size with Cronbach’ s α set to 0.05 and power set to 0.8, we determined that 64 participants would be needed in each group. Allowing for 20% incomplete or missing data, a total sample of 154 participants was deemed appropriate. Allowing for 20% incomplete or missing data, a total sample of 154 participants was deemed appropriate. Our final matched sample of 260 patients (130 per group) comfortably exceeded this minimum requirement, ensuring the study was adequately powered for the primary outcomes.

Instruments

We collected the demographic and medical characteristics of breast cancer patients who had undergone MRM or BR and used the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B) to measure QoL and the Psychosocial Adaptation Questionnaire (PAQ) to measure psychosocial adaptability.

Functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast

FACT-B is a breast cancer therapeutic function evaluation scale to evaluate the QoL of breast cancer patients20. The scale includes the subscales of physical well-being (7 items), social/family well-being (7 items), emotional well-being (6 items), functional well-being (7 items), and additional concerns (9 items). All items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = Not at all, 1 = A little bit, 2 = Somewhat, 3 = Quite a bit, 4 = Very much), with the total score ranging from 0 to 144 points. Cronbach’ s α coefficient for the FACT-B total score was 0.90, with those for the five subscales ranging from 0.63 to 0.86. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the scale have been proven in a study of breast cancer patients in China, and the scale is thus suitable for use in the Chinese population21.

Psychosocial adaptation questionnaire

The PAQ compiled by Cheng and Wang to evaluate the psychosocial adaptability of breast cancer patients was used in this study. 22 The questionnaire assesses anxiety/depression (8 items), self-esteem and self-acceptance (10 items), attitude (8 items), self-control/self-efficacy (9 items), and sense of belonging (9 items) and is rated on a 5-point Likert scale. The higher the score, the higher the level of psychosocial adaptability, with scores < 132 classified as low adaptation levels, 132–175 as moderate adaptation levels, and ≥ 176 as high adaptation levels. Cronbach’ s α coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.945, and the retest reliability was 0.961.The Psychosocial Adaptation Questionnaire (PAQ) underwent validation and revision in a 2022 study by Jiang et al., 23which enrolled women with breast cancer receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy. Psychometric evaluations confirmed strong internal consistency of the PAQ, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.876, thereby validating its reliability for assessing psychosocial adaptation in this target population.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Hunan Cancer Hospital Research Ethics Committee (Quick Review No. 16 in 2021). The research were performed in accordance with Hunan Cancer Hospital’s guidelines and regulations and informed consent was obtained from all participants.The collected data were anonymous and confidential and strictly used without disclosure of personal information.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.0 was used for data entry and statistical analysis. We used the “propensity score matching” function in this software with the caliper value set to 0.1, and the propensity score was calculated using logistic regression analysis. Two sets of data were matched according to propensity scores for variables, and both sets of baseline data were calibrated. For matching, we considered the variables age, body mass index (BMI), monthly family income, employment, menopause, disease duration, and operation time through literature search and expert consultation24,25,26. Finally, 260 patients (130 per group) were matched and compared. Means and standard deviations were computed for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Medians (quartiles) were calculated to represent age and PAQ scores. Chi-square tests and two-sample t tests were used to analyze the differences in categorical demographic variables and QoL, respectively, between the MRM and BR groups. Fisher’s exact test and the Mann–Whitney test were used to analyze the differences in age and PAQ scores, respectively, between the groups. Statistical significance was defined as p < .05, with the α level set to 0.05. Missing values were excluded from the statistical analysis.

Results

A total of 1,316 participants were recruited, of whom 1,178 patients had undergone MRM and 138 patients had undergone BR. After propensity score matching, a total of 260 patients were matched, with 130 patients in each group.

Characteristics of the matched data

There were statistically significant differences in age, BMI, menopause, marital status, education, employment, monthly household income, payment, and operation time between the two groups (Table 1). Most of the patients in the BR and MRM groups were 33–47 and 48–62 years old, respectively, which contributed to the differences in the proportions of employment, monthly income, and menopause between the two groups. Of the 130 patients in the BR group after propensity score matching, eight patients failed to match the corresponding patients in the MRM group (Table 1). Except for payment and operation time (p = .01), no other variable was significantly different between the two groups (p > .05). We then conducted multiple linear regression of two variables—payment and operation time—to explore their effects on the QoL and psychosocial adaptability of breast cancer patients. The results showed that these independent variables had a low impact on the QoL and psychosocial adaptability (13.6% and 3.7%, respectively) (Tables 2 and 3), with these outcomes being comparable between the two groups.

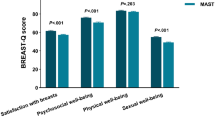

Comparison of QoL between the two groups

After propensity score matching, the mean FACT-B total scores in the BR and MRM groups were 107.58 (SD = 16.238) and 100.18 (SD = 8.556), respectively. Patients in the BR group had better social/family well-being (19.62 ± 4.330) and functional well-being (19.66 ± 5.046) than the MRM group, although the difference was not statistically significant (p > .05). However, the BR group had slightly higher FACT-B total scores and physical well-being, emotional well-being, and additional concerns subscale scores than the MRM group, with the differences being statistically significant (Table 4).

Comparison of psychosocial adaptability between the two groups

The total PAQ scores in the BR and MRM groups were 176 (163, 186) and 164 (158, 172), respectively (p < .05). In particular, scores in the domains of anxiety/depression, self-esteem and self-acceptance, self-control, and self-efficacy, but not in the domain of sense of belonging, were significantly different between the two groups (Table 5).

Discussion

This comparative study provides robust evidence that patients undergoing immediate or delayed breast reconstruction (BR) attain significantly superior long-term quality of life (QoL) and psychosocial adaptation outcomes relative to those treated with modified radical mastectomy (MRM) alone13. Beyond merely documenting these differences, we seek to elucidate the multifactorial mechanisms—psychological, sociodemographic, and physiological—that underlie these observed disparities.

A key interpretation of our findings centers on the role of BR in mitigating body image disturbance, a well-established sequelae of MRM with profound psychosocial implications5,6. Body image represents a core dimension of female self-concept and perceived attractiveness, and its disruption frequently precipitates emotionally distressing states, including shame, depressive symptoms, and anxiety5. Our results indicate that BR serves as a psychologically restorative intervention by reconstructing breast contour and bodily symmetry, thereby alleviating a primary source of distress and fostering a more integrated self-image23. This process of bodily reconciliation translates into measurable gains across emotional, self-evaluative, and interpersonal domains, offering a coherent explanation for the BR cohort’s elevated scores on the emotional well-being and additional concerns subscales of the FACT-B 28.

Presurgical demographic characteristics further contextualize these outcomes. The overrepresentation of younger, more educated, and economically advantaged women in the BR cohort—consistent with patterns reported elsewheret—suggests that sociocultural and economic factors meaningfully shape both treatment selection and postoperative adjustment29. Younger patients, often immersed in professional and social milieus where physical appearance is salient, may prioritize anatomical restoration as integral to preserving identity and QoL26 . Simultaneously, higher socioeconomic status expands access to specialized surgical information, enables financial coverage of reconstructive procedures, and often coincides with more robust social support networks. These resources not only inform initial decision-making but also bolster psychological resilience during recovery31,32. Thus, the benefits observed in BR patients likely arise from an interaction between surgical rehabilitation and structural advantages.

On a physiological level, the BR group’s enhanced physical well-being corroborates previous evidence indicating that reconstructive approaches can attenuate postoperative symptom burden, including chronic pain and lymphedema33,34. Somatic comfort is intrinsically linked to emotional well-being, as persistent physical distress exacerbates negative affect and impedes adaptive coping35. We posit a reciprocal relationship whereby physical improvements following BR support emotional regulation, which in turn facilitates broader psychosocial reintegration—a positive feedback cycle that merits further empirical investigation.

Finally, the BR group demonstrated strengthened self-efficacy, defined as individuals’ confidence in their capacity to execute behaviors necessary to achieve desired outcomes. This construct plays a critical role in ameliorating social avoidance and fostering re-engagement in valued roles and activities37. We contend that the recovery of bodily form and function through BR engenders a renewed sense of agency, which generalizes beyond physical recovery to empower patients in social and vocational contexts, reducing concealment behaviors and shame associated with mastectomy-related disfigurement15.

Future directions

Although our study offers compelling cross-sectional evidence, several investigative pathways remain open. Prospective longitudinal studies are warranted to characterize the temporal dynamics of QoL and psychosocial adaptation throughout the survivorship trajectory. Furthermore, multi-center studies incorporating diverse cultural and healthcare settings would enhance the external validity of our conclusions. Future work would also benefit from integrating objective biomeasures with patient-reported outcomes to minimize reporting bias, and from examining how culturally specific constructs of femininity and body image moderate surgical outcomes.

Limitations

This study is subject to several limitations. First, despite the application of propensity score matching to enhance comparability, the considerable disparity in sample size between the BR and MRM groups prior to matching resulted in a suboptimal utilization of the available data. Second, as data were sourced from a single medical center in Hunan Province, the findings may have limited generalizability to populations in other regions with differing healthcare systems and sociocultural contexts. Third, the reliance on self-reported data collected via online questionnaires introduces the potential for biases, such as social desirability and recall bias. The retrospective survey design, wherein patient responses were collected at varying post-operative intervals (< 3 years, 3–5 years, and > 5 years), may introduce recall bias and increase outcome variability.

Fourth, propensity score matching can only balance observed covariates. Residual confounding may persist due to unmeasured factors. For instance, variables such as patient motivation, health literacy, preoperative psychological state, or the type of reconstruction (e.g., implant-based vs. autologous tissue) were not included in the matching model due to data unavailability. These unmeasured clinical and personal characteristics could influence both the choice of surgery and the outcomes. Finally, we did not assess whether patients received formal psychological counseling or participated in support groups, which could be a significant confounder affecting both quality of life and psychosocial adaptation.

Finally, the study cohort was restricted to patients with TNM stage 0 to III breast cancer; consequently, the results may not be generalizable to those with stage IV disease.

Relevance to clinical practice

Compared with the BR group, the MRM group had a heavier burden of symptoms, poor physiological condition, lower self-acceptance, less positive attitude toward the disease, and a tendency to develop negative emotions. Therefore, patients who have undergone MRM require more symptom management and psychological counseling to improve their QoL and psychological adaptability.

Conclusions

In this study, undergoing breast reconstruction was associated with a better quality of life and psychosocial adaptability compared to undergoing modified radical mastectomy alone. The BR group reported better physiological conditions, fewer negative emotions, a more positive attitude toward the disease, greater acceptance of their body, and a higher sense of self-efficacy. These results can serve as an important reference for medical staff when providing predischarge care and guidance to breast cancer patients during hospitalization, which will in turn help enhance patients’ mental well-being, reduce symptom distress, and improve QoL and psychosocial adaptability.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Akram, M. et al. Awareness and current knowledge of breast cancer. Biol. Res. 50, 33 (2017).

Fahad, U. M. Breast cancer: current perspectives on the disease status. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1152, 51–64 (2019).

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 394–424 (2018).

Zhang, B. et al. A 10-year (1999 ~ 2008) retrospective multi-center study of breast cancer surgical management in various geographic areas of China. Breast 22, 676–681 (2013).

Fobair, P. et al. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psycho Oncol. 15, 579–594 (2006).

Kołodziejczyk, A. & Pawłowski, T. Negative body image in breast cancer patients. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 28, 1137–1142 (2019).

Colwell, A. S. & Taylor, E. M. Recent advances in implant-based breast reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 145, 421e-432e (2020).

Al-Ghazal, S. K., Fallowfield, L. & Blamey, R. W. Comparison of psychological aspects and patient satisfaction following breast conserving surgery, simple mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Eur. J. Cancer. 36, 1938–1943 (2000).

Kim, E. K., Chae, S. & Ahn, S. H. Single-port laparoscopically harvested omental flap for immediate breast reconstruction. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 184, 375–384 (2020).

Qin, Q. et al. Postoperative outcomes of breast reconstruction after mastectomy: A retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore) 97, e9766 (2018).

Yan, H. et al. Study on short-term cosmetic effects and quality of life after breast cancer modified radical mastectomy combined with one-stage prosthesis implantation. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 18, 1988–1993 (2022).

Homsy, A. et al. Breast reconstruction: A century of controversies and progress. Ann. Plast. Surg. 80, 457–463 (2018).

Konara, M. S. et al. Dynamic changes in quality of life, psychological status, and body image in women who underwent a mastectomy as compared with breast reconstruction: an 8-year follow up. Breast Cancer. 30, 226–240 (2023).

Li, Y. J., Tang, X. N. & Li, X. Q. Effect of modified radical mastectomy combined with latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap breast reconstruction on patients’ psychology and quality of life. Am. J. Transl Res. 13, 11548–11555 (2021).

Xiao, H. M. et al. Influencing factors of stigma in breast cancer patients after operation and its relationship with self-esteem, quality of life and psychosocial adaptability. Progress Mod. Biomed. 21, 4522–4526 (2021).

Chopra, I. & Kamal, K. M. A systematic review of quality of life instruments in long-term breast cancer survivors. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 10, 14 (2012).

Liao, F. et al. Survey research on psychosocial adaptation level in postoperative patients with breast cancer. Chongqing Med. 51, 1–7 (2022).

Roy, C., Whetsell, M. V. & Frederickson, K. The Roy adaptation model and research. Nurs Sci Q. 22, 209–211 (2009).

Taylor, S. E. & Brown, J. D. Illusion and well-being: a social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychol. Bull. 103, 193–210 (1988).

Brady, M. J. et al. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast quality-of-life instrument. J. Clin. Oncol. 15, 974–986 (1997).

Wan, C. et al. Validation of the simplified Chinese version of the FACT-B for measuring quality of life for patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 106, 413–418 (2007).

Cheng, R. & Wang, A. P. Development of psychosocial adaption questionnaire for breast cancer patients. Chin. J. Practical Nurs. 28, 1–5 (2012).

Jiang, H., Zhang, X., Dong, Y., Xu, H. & Jin, F. Development and evaluation of a psychosocial adaptation questionnaire for women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant endocrine therapy:a single-centre, cross-sectional study in China. BMJ Open. 12 (11), e063082 (2022).

Liu, Y. H. & Zhu, W. Chinese expert consensus on breast reconstruction after breast cancer surgery(2019 edition). Chin. J. Practical Surg. 39, 1145–1147 (2019).

Breast Cancer Committee of Chinese anti-Cancer Association. Chinese anti-Cancer association guidelines and specifications for the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer (2021 edition). China Oncol. 29, 609–680 (2019).

Ma, L. X. X. et al. Relationship between breast reconstruction and travel distance. China Oncol. 28, 140–145 (2018).

Tsaras, K. et al. Assessment of depression and anxiety in breast cancer patients: prevalence and associated factors. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 19, 1661–1669 (2018).

Jankowska-Polańska, B. et al. The association between illness acceptance and quality of life in women with breast cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 12, 8451–8464 (2020).

Yao, Y. R. Analysis of the influencing factor about breast cancer patientschoosing reconstruction. Master Dissertation, Shanxi: Shanxi Medical University (2017).

Schumacher, J. R. et al. Socioeconomic factors associated with post-mastectomy immediate reconstruction in a contemporary cohort of breast cancer survivors. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 24, 3017–3023 (2017).

Gao, Q. Q. et al. Relation of psychosocial adjustment to social constraints and intrusive thoughts in patients with breast cancer. Chin. Mental Health J. 34, 756–760 (2020).

Qiu, J. J. & He, Y. Q. Investigation on social-psycholocical adaptation of young patients with breast cancer and analysis of influencing factors. Shanghai Nurs. 20, 27–31 (2020).

Xu, M. Clinical efect of simultaneous breast reconstruction with latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap and modified radical mastectomy for breast cancer. Guide China Med. 18, 126–127 (2020).

Zhou, Z. Z. Effects of Breast Reconstruction on Lymphedema:a Meta-analysis [Master dissertation], Jiangxi: Nanchang University; (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Quality of life in patients with breast cancer following breast conservation surgery: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Healthc. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3877984 (2022).

Bu, X. et al. Unmet needs of 1210 Chinese breast cancer survivors and associated factors: a multicentre cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer. 22, 135 (2022).

Jin, H. Y. et al. [Current status and influencing factors of social avoidance and distress in patients with breast cancer after surgery]. Maternal Child. Health Care China. 36, 1613–1616 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement: Professional English language editing support was provided by AsiaEdit (asiaedit.com).

Funding

Supported by 2022 Hunan Provincial High Level Health Talents and 2023 Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation, grand number:2023JJ60328.

The authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions: Wenjing Hong: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing - original draft. Zhengdi She: Writing - review & editing; Supervision; Software, the coauthor contributed equally to the study as the first author. Xiangyu Liu: Project administration; Resources; Funding acquisition; Validation. Pei Yang: Project administration; Resources; Methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, W., She, Z., Liu, X. et al. A comparative study of quality of life and psychosocial adaptability following modified radical mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Sci Rep 15, 45382 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29121-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29121-z