Abstract

In the accretionary complexes of areas where erosion is inactive, only biogenic chert is sometimes exposed and estimating diagenetic/metamorphic temperature in such areas is nearly impossible. We investigated the correlation of quartz crystallinity (CI), grain size (GS), and diagenetic/metamorphic temperature (PT) of biogenic chert and developed a quartz-based geothermometer to contribute to the advancement of tectonics in such regions. Sediments of microbial remains comprising amorphous silica can transform into biogenic chert/metachert during diagenesis/metamorphism through an increase in CI and GS. However, the relationship between CI, GS, and PT remains underexplored. By examining Paleozoic–Mesozoic biogenic chert/metachert from four regions of East Asia, we identified a systematic relationship between CI, GS, and PT. In cryptocrystalline chert (GS ≤ 1.94 μm), CI and GS exhibit a strong logarithmic relationship, whereas in crystalline chert, CI approaches its upper limit and GS widely varies. These relationships are consistent across four studied regions, irrespective of their geological age and location. CI and GS increase with increasing PT, with a positive linear relationship between CI and PT and a logarithmic relationship between GS and PT. CI and GS strongly correlate with PT (R > 0.929), making them reliable geothermometers for estimating diagenetic/metamorphic temperature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A geothermometer is used for measuring paleotemperature (PT) experienced by rocks. Some geothermometer approaches rely on the relationship between PT and phase equilibrium or mineral reaction rates and others use the correlation between PT and mineral crystallinity. Minerals in pelitic rocks are generally used as geothermometers for sedimentary rocks. However, in regions such as within a continent, where erosion is inactive and alluvial sediments predominantly cover the rocks. Therefore, in such regions, it is challenging to estimate the PT of the geologic units and understand the detailed tectonic history, especially in accretionary complexes formed by the subduction of an earlier oceanic plate. Biogenic chert, primarily composed of quartz, often forms exposed ridges due to its resistance to weathering, even in regions where pelitic rocks are absent (Fig. 1). Therefore, if the PT of biogenic chert is estimated, tectonics research in such regions may be greatly advanced.

Sediments composed of siliceous microbial remains, such as those of radiolarians, transform into biogenic chert and metachert through diagenesis and metamorphism, respectively, wherein amorphous silica is converted into quartz, often through the opal-CT phase1,2,4. Quartz crystallinity (CI)3 and grain size (GS) are believed to increase with increasing PT4,5,6. Numerous studies on the transformation of amorphous silica into quartz have been conducted4. It has been confirmed that higher temperatures lead to a higher conversion rate of amorphous silica into quartz, and the activation energy for this reaction has been calculated7,8,9,10,11. These results have been used to understand the mechanisms in the early stage of the diagenesis of silica deposits7,11,12,13,14,15.

However, the relationship between quartz CI and GS after the early stage of diagenesis as well as their correlation with PT remain unclear. For the radiolarian chert obtained from the Jurassic accretionary complex of the Tanba belt, Japan, it has been suggested that quartz CI and GS show a logarithmic relationship—CI and GS increasing as PT rises—based on the color index of co-existing conodont fossils16. Although the cited study provides an overview of the relationship between CI, GS, and PT, its accuracy seems insufficient. Moreover, the CI of radiolarian chert and metachert obtained from the Khangai–Daur belt, a Carboniferous accretionary complex in Mongolia, was reported to increase sharply with increasing GS. Even after CI has almost reached its maximum (8–10), GS continues to increase17. However, the detailed relationship between CI and GS as well as PT conditions experienced by the rocks remain unspecified. Clarifying the correlation between CI, GS, and PT can provide valuable insights into the tectonics of orogenic belts, especially in regions where other rock types are scarce.

This study investigated the relationship between the CI, GS, and PT of biogenic chert and metachert obtained from East Asia, specifically from accretionary complexes in Japan (Chubu province and Ashimidani area)18, Russia (Anyui area)19,20, and Mongolia (Ulaanbaatar area)21,22 (Figs. 1 and 2). In addition, the relationship between the CI or GS and PT of cryptocrystalline chert was discussed compared with the PT for mudstone, which conformably overlies the cryptocrystalline chert, to develop a new geothermometer. CI, GS, and PT were determined using X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM)/optical microscopy, and a Raman spectra of carbonaceous material (RSCM) geothermometer, respectively3,16,24. The results from the CI, GS, and PT measurements of each sample were analyzed using linear regression analysis with the least squares method to determine the relationships between the variables.

Index map of the study areas. Modified from Umeda et al. (2022)23. Sb: Siberian craton, NC: North China block, T–Qd: Tarim–Qaidam block, SM: South Mongolian block, B: Bureya block.

Samples analyzed

Samples of biogenic chert and metachert

A total of 112 samples from four regions were analyzed (Fig. 2; Table 1): 64 samples from Japan (Mino and Ryoke belts in Chubu province and the Tanba belt in the Ashimidani area)18, 14 from Russia (Samarka terrane and the Anyui metamorphic complex in the Anyui area)19,20, and 34 from Mongolia (Ulaanbaatar terrane at Ulaanbaatar area)21,22. These samples were selected based on their composition, and only those without significant secondary alteration or microquartz veins were analyzed.

Microfossils from the Middle Triassic to Middle Jurassic, including those of radiolarians and conodonts were recovered from chert in the Mino belt of the Jurassic accretionary complex of the study area25,26,27,28. The Ryoke belt is generally considered the metamorphosed facies of the Mino belt18. Microfossils of Permian radiolarians and conodonts have been found in chert of the Tanba belt, Ashimidani area, Japan29. The Samarka terrane and Anyui metamorphic complex, located ~ 250 km northeast of Khabarovsk, are the Jurassic–Cretaceous accretionary complex and its metamorphosed form, respectively20. Middle Triassic to Middle Jurassic radiolarians and conodonts were recovered from chert obtained from the Samarka terrane20. The Carboniferous accretionary complex of the Ulaanbaatar terrane, lying within the Eurasian continent, contains radiolarian chert from the Upper Silurian to the Upper Devonian22.

Samples from the Ryoke belt and Anyui metamorphic complex underwent contact metamorphism owing to Cretaceous igneous activity18,20. Some samples obtained from the Samarka and Ulaanbaatar terranes were also metamorphosed17,21.

All samples—composed mostly of quartz—were obtained from well-bedded chert or metachert outcrops (Fig. 3a). In the outcrops, chert or metachert layers with a thickness of several centimeters alternated with thin muddy films with a thickness of < 5 mm (Fig. 3a). Only the central part of the chert layer was examined as the part in contact with the thin muddy films may have undergone alteration4. As per microscopy results, the chert samples from the Mino and Tanba belts and the Samarka and Ulaanbaatar terranes were composed mainly of cryptocrystalline quartz. Individual crystals were difficult to identify at 40 × magnification and contained well-preserved or poorly preserved radiolarian tests (Fig. 3b; Table 1). Chert samples whose biogenic origin could not be verified, such as those lacking fossil remains, were not used in this study. The metachert samples from the Ryoke belt, the Samarka and Ulaanbaatar terranes, and the Anyui metamorphic complex comprised crystalline quartz (Fig. 3c and d; Table 1). Although no distinct fossil remains were visible in the metachert samples, a biogenic origin could be inferred as the origin field closely resembled that of radiolarian chert—well-bedded field with several-centimeter-thick layers and thin muddy interbeds. Approximately 54% of the analyzed samples consisted of cryptocrystalline quartz containing numerous radiolarian tests and 46% comprised crystalline quartz. Microscopic observations of thin sections in different directions of each sample confirmed that the quartz grains of all samples showed no particular anisotropy. Crystallinity index (CI) was determined based on XRD and GS was measured using SEM or optical microscopy.

(a) Field occurrence of the Upper Triassic bedded biogenic chert in the Mino belt in Chubu province, Japan (sample No. 10). Refer to Fig. 3e and Table 1 for locality details. (b) Optical photomicrograph (obtained in plane polarized light) of the Upper Triassic biogenic chert including numerous radiolarian tests (white spots in the picture). Plane polarized light. (c) Backscattered scanning electron image of a bedded metachert sample obtained from the Ryoke belt in Chubu province, Japan. (d) Optical photomicrograph (obtained in cross-polarized light) of a bedded metachert sample composed of crystalline quartz obtained from the Ryoke belt in Chubu province, Japan. (e) Satellite image of the locality around sample No. 10. The image was taken from Google Earth Pro (https://www.google.com/permissions/geoguidelines/?hl=ja). Following the oceanic plate stratigraphy, the chert layers are overlain by siliceous shale and clastic rocks. Ch.: bedded radiolarian chert, Ssh.: siliceous shale, Cl.: clastic rocks, Loc.: locality, Rv: river. (f) Field observation of the alternating layers of sandstone and mudstone beds overlying the radiolarian chert beds. The locality is shown in Fig. 3e.

Samples of the mudstone

Nine samples were collected from mudstone layers present near the chert exposed in the Mino and Tanba belts, Japan, for PT measurement using an RSCM geothermometer24. The mudstone outcrops were located approximately 5–800 m from the chert outcrops and stratigraphically present above them, following oceanic plate stratigraphy (Fig. 3 e and f)30,31,32,33. The mudstone samples were black to dark gray, mostly undeformed, well laminated, or alternating with sandstone (Fig. 3f). Microscopic examination of the samples showed no signs of shearing. The RSCM geothermometer was used to estimate the PT of the mudstone samples, which were obtained from nearby outcrops, to compare it with that of the chert samples.

Analytical methods

CI of the biogenic chert and metachert samples

The CI of all samples was measured using XRD (MultiFlex, Rigaku Corporation), installed at the Nagoya University Museum by following the method reported by Murata and Norman3. The samples were crushed and sieved to 75 μm. Then, SEM observation confirmed that most particles were in the range of 1–20 μm. The powdered samples were mounted in a glass holder for the measurement. Device background settings of XRD were as follows: X-ray: Ni–filtered copper radiation, scanning range: 2θ = 65°–70°, scanning speed: 1°/minute, voltage: 40 kV, current: 4 mA, and divergence slit: 1°.

The CI of the samples was calculated from the intensity of the (212) peak at 2θ = 67.74° of the samples using the following equation3:

CI = 10 F a / b.

The values “a” and “b” are shown in Fig. 4. Herein, euhedral quartz obtained from the Minas Gerais, Brazil was used as the standard sample to calculate the F value. The values of “a” and “b” determined from the analysis of the standard quartz sample were substituted into the above formula and found the F value as CI = 103. The analysis process of this research was divided into 15 sessions, and the F value was calculated each time (1.33–1.57).

Quartz (212) peak at 2θ = 67.74° of the standard sample obtained from the Minas Gerais, Brazil. The values “a” and “b” determined by Murata and Norman (1976)3 are shown.

The analytical error in the CI measurements of six samples (Sample Nos. 2, 8, 11, 79, 87, and 152) was examined (Fig. 5a). Three powder mounts were prepared for the same sample. The analysis was then repeated five times for each powder mount. As a result, the standard deviation (1σ error) of the CI values for each sample was 0.32–0.52 (average: 0.45) in a total of 15 analyses/sample (Fig. 5a).

(a) Results of the repeated CI measurements of quartz in the biogenic chert and metachert samples. The standard deviations of the five analyses for each powder mount are shown with error bars. (b) Results of repeated GS measurements of quartz in the biogenic chert and metachert samples. The standard deviations of six and seven analyses by three authors for each sample are shown with error bars. The left Y-axis is for sample Nos. 11, 8, and 152, and the right Y-axis is for sample Nos. 8, 7, and 79. Relative standard deviations for each sample are also shown with three significant digits. No.: number.

GS of the biogenic chert and metachert samples

The measurement of quartz GS was carried out by following the method reported by Mikami et al. (2002)16. Apparent GS measured from the thin section or slab surfaces of the biogenic chert or metachert samples is defined as GS herein16. The samples were cut in multiple directions and each thin section was observed using an optical microscope. Results revealed that the quartz grains in all samples had not undergone shear deformation. Photomicrographs (taken in cross-polarized light) were used for the GS measurement of crystalline chert (Fig. 3d). For cryptocrystalline chert, the samples were cut into 1-cm square slabs and mirror polished using a diamond paste. The polished surface was etched with 15% hydrofluoric acid for 5 min, and then gold or carbon coating was performed. Subsequently, the gold- or carbon-coated etched surface was observed via SEM (Hitachi High-Tech Corporation, S-3400N and Miniscope TM-1000) installed at the Nagoya University Museum (Fig. 3c).

Further, 10–20 parallel lines were drawn on the obtained SEM image and the distance between each of the point that the lines and grain boundaries intersect was measured. Nearly 300 such measurements were performed for each sample. Histograms and cumulative frequency curves were then plotted, and the GS of the sample was determined as the GS corresponding to a cumulative relative frequency of 0.516.

We investigated the analytical errors in GS measurements for each of the six samples (Sample Nos. 2, 8, 11, 79, 87, and 152). A total of six to seven analyses were performed for each sample by three authors. The relative standard deviation of the 1σ error (RSD) of the GS for each sample was 8.46%–11.9% (average: 10.4%) (Fig. 5b).

PT of mudstone present nearby the biogenic chert and metachert samples

Nine mudstone samples exposed in close proximity to the chert samples were collected, and their PT values were measured using the RSCM geothermometer24. Then, the PT values of these mudstone samples were considered to be the same as those of the chert samples, because no fault relationship existed between the chert and mudstone layers. Diamond-polished thin sections were prepared for each mudstone sample and the RSCM were acquired using a spectrometer (Nicolet Almega XR, Thermo Fisher Scientific), installed at the Rock and Mineral Laboratory of Nagoya University. The Raman spectra were obtained in the wavenumber range of 655–1748 cm−1, and ~ 30 carbonaceous grains were detected in each sample. The spectra were decomposed into three to five peaks using PeakFit 4.12 (SeaSolve Software Inc.). Peak fitting was performed for each spectrum and mean values and standard deviations of FWHM-D1 were determined for each sample. The value “FWHM-D1” is the full width at half maximum of the peak named D1 occurring at ~ 1350 cm−1 in the spectra. Data deviating more than 2σ from the mean were omitted, and final means were determined using only remaining data. Then, temperatures were calculated using the following eqation 24. The analytical error in the temperature measurement was ± 30 °C24.

Results

Relationship between CI and GS

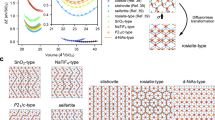

The data used in this study are provided in Table 1, and Fig. 6a shows a plot of the relationship between CI and GS. Data obtained from Japan, Russia, and Mongolia showed similar trends (Fig. 6a). Specifically, CI and GS showed in a logarithmic relationship when GS was low (roughly cryptocrystalline). Further, CI was stabilized at almost 8.0–10 and GS increased (roughly crystalline).

(a) Relationship between the quartz crystallinity index (CI) and grain size (GS) of the biogenic chert and metachert samples. The dotted line is the approximate line of CI vs. GS (for the group of datapoints with GS ≤ 1.94 μm). Paleotemperatures of the mudstone samples present nearby the chert samples are also shown. Cpt: cryptocrystalline chert, Cst: crystalline chert, M: Middle, U: Upper, Sil.: Silurian, Dev.: Devonian, Trias.: Triassic, Jura.: Jurassic. (b) Relationship between the correlation coefficient (R value) of CI and GS and the maximum crystal size (μm) in the group of datapoints. Refer to Table 2 for the data. GS: grain size, n: number of the data.

Next, we discuss the range where a logarithmic relationship was observed between CI and GS holds. This study examined the group of datapoints showing the highest logarithmic correlation coefficient (R value) between CI and GS by adding datapoints in the ascending order of GS, starting with the smallest GS (0.306 µm for the sample No. 44) (Fig. 6b; Table 2). The R value increased with increasing number of datapoints, reaching the maximum for the group of datapoints with GS ≤ 1.94 µm. Thereafter, the R value gradually decreased as the number of datapoints increased. For the group with GS ≤ 1.94 µm, the approximation relation between CI and GS was as follows (Fig. 6):

The correlation coefficient of this equation is not low; therefore, this group can be regarded as the one that shows a logarithmic relationship between CI and GS (Fig. 6b).

Relationship between GS or CI and PT

This section discusses the relationship between CI or GS and PT for the group of datapoints for which Eq. 1 holds (the group with GS ≤ 1.94 µm) for the samples obtained from Japan. The investigated mudstone and chert samples have a conformable relationship and the PT experienced by both the rock types over geologic time was assumed to be nearly identical (Fig. 3a, e, and f). Therefore, the PT of the mudstone outcrops present near the chert outcrops, as measured using the RSCM geothermometer, was considered to be the PT of the chert samples. Furthermore, CI and GS were found to increase regularly with increasing PT, with a positive linear relationship observed between CI and PT (Fig. 7a) and a logarithmic relationship observed between GS and PT (Major Points) (Fig. 7b). Based on the actual measurements of CI for the chert samples and PT for the adjacent mudstone samples, the following equation between CI and PT was established (Fig. 7a):

where TCI is a PT value (in °C) corresponding to a CI value.

(a) Relationship between the quartz crystallinity index (CI) of chert vs. paleotemperature of mudstone present nearby the chert outcrops. Error bars for quartz crystallinity and paleotemperature denote ± 0.45 and ± 30 °C respectively. (b) Relationship between the quartz grain size (GS) of chert vs. paleotemperature of mudstone present nearby the chert outcrops. Error bars for GS and paleotemperature denote ± 10% of the data and ± 30 °C respectively. CI: quartz crystallinity index, GS: quartz grain size.

From Eq. 2, PT (TCI) was expressed as follows:

For the relationship between GS and PT, based on actual observations, the following equation was derived (Fig. 7b):

where TGS is a PT value (in °C) corresponding to a GS value.

Then, Eq. 4 was modified as follows:

Discussion

Spatiotemporal commonality of the CI versus GS relationship

In the circum-Pacific orogenic belt, the chert samples obtained from the Chubu province and Ashimidani area were assigned to the Triassic–Jurassic and Permian, respectively25,26,27,28,29. The chert samples obtained from the Anyui area, located ~ 1500 km north of the study areas in Japan, dated back to the Triassic–Jurassic period20. In the Central Asian orogenic belt of the Mongolia, the chert samples obtained from the Ulaanbaatar area contained microfossils from the Silurian and Devonian periods22. Samples obtained from the investigated regions of Japan, Russia, and Mongolia showed varying ages and places of origin (Fig. 2).

Some geological units analyzed in this study underwent various degrees of metamorphism and alteration and were intruded by dikes and mineral veins. Furthermore, chert exposed near basaltic rocks might have been of submarine hydrothermal origin. This study focused on the relationship between the CI, GS, and PT of biogenic chert through the diagenesis and metamorphism process, and factors that may affect the CI and GS data other than temperature were excluded as much as possible. For example, samples that may have undergone hydrothermal alteration (e.g., those located near the thin muddy films intercalated with chert layers, those near large veins, and those containing many quartz microveins) were excluded in this study. Samples, exposed near the basaltic rocks, without any fossil remains were avoided, considering the possibility of them being hydrothermal chert. It is widely known that the dynamic recrystallization of quartz can lead to GS reduction34. Consequently, all examined chert samples were confirmed to be undeformed. All data obtained from Japan, Russia, and Mongolia showed the same trend each other, i.e., CI and GS showed in a logarithmic relationship when GS was low, and CI were stabilized at almost 8.0–10 when GS was high. Therefore, the relationship between CI and GS discussed herein is probably a general principle for biogenic chert, regardless of rock age and place of origin (Figs. 2 and 6a).

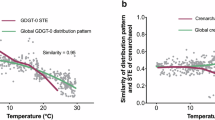

Spatial consistency verification of the derived equations

The derived equations were obtained empirically from independent observations of the CI–GS, CI–PT, and GS–PT relationships. The relationship between CI or GS and PT was derived from data obtained from Japan, and can be applied to the Jurassic accretionary complex in Japan. However, it still remains questionable whether the relationship between CI or GS and PT is also generally applicable. If these relationships are applicable to the other regions, it should be in concordant with the relationship between CI and GS which is a general principle of the biogenic chert regardless of age and place. Here, to assess the spatial consistency of these relationships, Eqs. 1, 3, and 5 were used to examine whether the correlation between CI and GS and that between CI or GS and PT aligned with each other. The relationship between TGS corresponding to any GS value (TGS†) and TCI corresponding to a CI value calculated by substituting any GS value into Eq. 1 (TCI†) is shown in Table 3. If Eq. 1—derived from data obtained from Japan, Russia, and Mongolia—and Eqs. 3 and 5—derived from data obtained from only Japan—are inconsistent, TCI† ≠ TGS† is expected. Further, if the Eqs. 1, 3, and 5 match, TCI† = TGS† should apply.

Therefore, TCI† = 0.920 TGS† + 26.0 was obtained as the correlation equation for TCI† and TGS†, with a slight deviation from the ideal equation (TCI† = TGS†) (Fig. 8a). This deviation might be attributed to CI and GS measurement errors, as discussed later. To assess the similarity between these two equations, cosine similarity can be used, which evaluates the parallelism of two vectors. Cosine similarity is defined as the cosine value of the angle between two vectors; for example, a cosine similarity of 1 indicates that the vectors are parallel (the angle between the two vectors is 0°), and a cosine similarity of 0 indicates that they are orthogonal (the angle between the two vectors is 90°). As the extent of parallelism between the two vectors increases the cosine similarity value approaches 1. The cosine similarity between the equations TCI† = 0.920 TGS† + 26.0 and the ideal equation (TCI† = TGS†) was almost 1 (0.999). Therefore, it was concluded that the slopes of the two equations for TCI† and TGS† were nearly identical. Moreover, the difference between TCI† and TGS† within the range investigated in this study (GS: 0.4–1.9 μm) was small: 8.4°C for TGS† = 220°C and 0.42°C for TGS† = 331°C (Fig. 8a). Thus, the relationship between CI, GS, and PT proposed in this study apparently hold well within the range of 220°C–330°C.

Figure 8b shows the TCI vs. TGS plots of the biogenic chert and metachert samples obtained from actual CI and GS values for Japan, Russia, and Mongolia using Eqs. 3 and 5. The data scattered along the ideal line (TCI = TGS), with the standard deviation of the difference between TCI and TGS being 17.9°C (1 σ) and 35.9°C (2 σ). Although this seems to be the error limit in the current investigation, the study clearly outlines the relationship between quartz CI, GS, and PT in the cryptocrystalline region. Furthermore, using the method presented in this study, the reliability of the results can be assessed by comparing TCI and TGS.

Limitations of this study and future aspects

The previous section confirms the spatial consistency of the CI–GS, CI–PT, and GS–PT relationships; however, the present data still show regional bias. This study was based on the data obtained from four regions in East Asia. Further collection of data for biogenic chert in other regions will refine the correlations among CI, GS, and PT. Notably, the mutual relationship between CI, GS, and PT proposed herein is only applicable for the group of datapoints with GS ≤ 1.94 µm. CI early reaches its maximum at GS = 1.94 µm, and for the group of datapoints with GS > 1.94 µm, CI and GS show a linear relationship (Fig. 6b). Therefore, the equations proposed in this study are applicable only to unmetamorphosed and weakly metamorphosed chert and cannot be applied to chert in the “metamorphic belt.” To estimate PT from quartz GS (in the range of 2.9–67 μm), the equation T (°C) = 39.7 ln (quartz GS) + 204 has been proposed in a study on low-grade metamorphic rocks in the Sambagawa belt, southwest Japan6. This equation, in combination with the equations derived in the present study, can form a powerful tool for clarifying the tectonothermal histories of metamorphic belts. However, this may not be always an easy and inexpensive method because it involves electron backscatter diffraction analysis etc. To clarify the tectonothermal histories of broader regions on Earth, the development of a simple method for estimating PT from the GS of crystalline chert using an optical microscope, as demonstrated in this study, might be important as well.

In the method proposed herein, the smaller GS values lead to larger differences between TCI† and TGS† (Fig. 8a). This might be attributed to CI and GS measurement errors. The standard deviation of the CI values in this study was 0.32–0.52 (1σ error), which might not be strictly small (Fig. 5a). Moreover, the microscopic examination of GS is a subject to observer bias; consequently, the RSD of GS in this study was 8.46%–11.9% and the average was 10.4% (Fig. 5b). In the low-temperature range, especially, these measurement errors of CI and GS may have a remarkable impact on PT estimation. In the future, by developing a method for accurately measuring a GS of < 1 μm or through some correction formula, the determination of more accurate values of TCI and TGS will be possible in the low-temperature range.

The results of this study were empirically derived and are not supported by theoretical background. It has been reported that when the spatial distribution of garnet in metamorphic rocks is uniform and sufficient time has elapsed for equilibrium to be reached, the GS distribution of garnet is consistent with the Lifshitz–Slyozov–Wagner distribution of Ostwald ripening35. Further, it has been revealed that higher temperatures lead to higher conversion rates of amorphous silica into quartz7,8,9,10,11. In future investigations, consideration of concepts such as Ostwald ripening, silica phase transformations, crystal growth under stress, can provide important insights into the theoretical understanding of the relationship between quartz CI, GS, and PT.

The XRD intensity of quartz powder is known to be the highest when the particle size is 1–10 μm; the intensity decreases when the particle size is < 1 μm or > 10 μm36. Herein, we determined the chert CI using powder samples with a mean particle size of 1–20 μm; however, we acknowledge that some larger/smaller particles contaminated the samples. For increased sufficient X-ray intensity, paying close attention to the particle size of the sample powder is necessary.

Herein, PT of the mudstone sample obtained from the mudstone outcrop overlying the chert outcrop was that of the chert sample and the correlation between CI and GS vs. PT was investigated. Therefore, highly positive correlations (R > 0.93) were observed between CI and PT and between GS and PT (Fig. 7). However, a sample (No. 162) appears to lie outside the approximate lines of CI or GS vs. PT, toward the high-temperature side (Fig. 7). The mudstone sample for which PT was estimated was located only 100 m away from the chert outcrop of the sample No. 162. No fault rocks were recognized between them, and these chert and mudstone outcrops seemed to be in a conformable relationship. Further, the estimated reason for high PT of sample No. 162 was investigated.

A major thrust fault dividing the geological units existed just 200 m to the north of the chert and mudstone outcrops29. In general, the temperature around a fault rises owing to frictional heat and hot fluids entering the cracks created by fault activity, thereby causing hydrothermal alteration of the surrounding rocks. A previous study revealed that the fault gouge around the Nankai Trough was heated to > 300 °C using a vitrinite reflectance geothermometer37. Therefore, the mudstone sample might have been affected a local thermal event owing to the thrust fault activity. This might be the reason for the deviation from the approximate line. The deviation of the sample No. 162 from the approximate line is likely owing to higher sensitivity of carbonaceous material crystallinity to PT than quartz CI or GS. As the regression equations of CI or GS vs. PT were mostly the same even when including or excluding the mudstone sample data, this study presented them as well (Fig. 7). However, in future, when applying the method proposed in this study, paying attention to the surrounding geological structure, especially the fault distribution around the sampling locations to avoid the thermal influence of fault activities on analysis outcomes, is necessary.

According to a study of chert obtained from the Jurassic accretionary complex in Japan (Ashimidani area), a logarithmic relationship between CI and GS has been suggested for GS < 10 μm using the conodont color index, further suggesting an increase in CI and GS with increasing PT16. The results of this study are supported by these observations. Mikami’s results lacked the precision necessary for reliable PT estimation; however, this study provides high-precision empirical equations that offer a robust tool for estimating the PT of biogenic chert in the cryptocrystalline region.

In geosciences, mineral geothermometers, such as garnet–biotite thermometers, chlorite thermometers, and illite/carbonaceous material crystallinity thermometers, have been widely applied as powerful tools for understanding Earth’s history24,38,39,40,41. Minerals in pelitic rocks are commonly used as geothermometers for sedimentary rocks (including metamorphic rocks). For example, the PT estimation of rocks in accretionary complexes has helped clarify subduction and accretionary systems42. However, in regions where erosion is inactive and alluvial sediments mostly cover the rocks, no pelitic rocks are exposed; only relatively hard erosion-resistant biogenic chert and metachert rocks are present (Fig. 1). The method proposed herein has significant implications for geothermometers in regions with limited pelitic-rock exposure. In future, the methodology developed in this study can become an essential tool for geologists working in regions where pelitic rocks are inaccessible, improving our understanding of tectonic processes in underexplored geological settings. For example, Northeast Eurasia is considered to have formed by the collision of the Siberian and South Mongolian continents. Further, the boundary between the two continents is defined as the Mid-Mongolian Tectonic Line (MMTL)23,43. The southern part of Siberia (Carboniferous accretionary complex; Khangai–Daur belt) appears to show an increase in the metamorphic grade toward the MMTL, and its metamorphism is indispensable for understanding the tectonics of Northeast Eurasia44. However, the Khangai–Daur belt hardly exposes pelitic rocks, leaving its metamorphism poorly understood. The application of the method proposed herein as well as future geothermometers developed based on crystalline quartz to biogenic chert in the Khangai–Daur belt will probably promote greatly the study of the tectonics of Northeast Eurasia. Furthermore, a noteworthy aspect of this study is that it enables the reliable and easy estimation of PT using inexpensive equipment such as optical microscopes, SEM devices, and XRD devices. The proposed method is expected to significantly contribute to study of geology around the world for elucidating Earth’s history.

While the study provides a reliable method for estimating PT in the range of 220 °C–330 °C, its applicability at higher temperatures or other geological environments requires further investigation. Future research should focus on expanding the temperature range for quartz geothermometers, incorporating samples from different geological settings, and refining the CI–GS correlation in cryptocrystalline chert for broader applications.

Glossary of technical terms

Pelitic rocks: Sedimentary rocks composed of clay- or mud-size particles and their metamorphosed forms.

Alluvial sediments: The latest sediments carried by streams and deposited where the stream slows down.

Chert: Fine-grained sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz.

Metachert: Metamorphosed chert.

Radiolarians: A single-celled marine planktonic eukaryotic organism with a diameter of <1 mm and a skeleton composed of silica.

Diagenesis: A process by which sediments solidify to form sedimentary rocks.

Accretionary complex: A geological unit formed when sediments and other materials on an oceanic plate are accreted to the continental side after oceanic plate subduction.

Cryptocrystalline: A rock texture composed of very small crystals. Even under an optical microscope, the crystal shape is hardly recognized.

Crystalline: A rock texture composed of crystals that can be recognized under an optical microscope.

Microfossils: Fossils, which have a size of typically less than a few millimeters, that require a microscope to be observed.

Conodonts: “Tooth-like” microfossils of marine jawless vertebrates.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Grotzinger, J., Jordan, H. T., Press, F. & Siever, R. Understanding earth, 5th edition. 579p (W. H. Freeman and Company, 2007).

Boggs, S. Jr. Principles of Sedimentology and Stratigraphy, 4th edition. 662p (Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006).

Murata, K. J. & Norman, M. B. An index of crystallinity for quartz. Am. J. Sci. 276, 1120–1130 (1976).

Hattori, I. Chert and siliceous sediments: their depositional processes and diagenesis. 272p (Kinmiraisha, 2008).

Hein, J. R., Vallier, T. L. & Allan, M. A. Chert petrology and geochemistry, Mid-pacific Mountains and Hess rise, deep sea drilling project leg 62. Init. Rep. DSDP 42, 711–748 (1981).

Hara, H., Mori, H., Tominaga, K. & Nobe, Y. Progressive low-grade metamorphism reconstructed from the Raman spectroscopy of carbonaceous material and an EBSD analysis of quartz in the Sanbagawa metamorphic event, central Japan. Minerals 11, 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/min11080854 (2021).

Mizutani, S. Progressive ordering of cristobalitic silica in the early stage of diagenesis. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 61, 129–140 (1977).

Ernst, W. G. & Calvert, S. E. An experimental study of the recrystallization of porcellanite and its bearing on the origin of some bedded cherts. Am. J. Sci. 267A, 114–133 (1969).

Kano, K. & Taguchi, K. Experimental study on the ordering of opal-CT. Geochem. J. 16, 33–44 (1982).

Mitsui, K. & Taguchi, K. Silica mineral diagenesis in Neogene Tertiary shales in the Tempoku district, Hokkaido Japan. J. Sediment. Petrol. 47, 158–167 (1977).

Reich, V. & von Rad, U. Silica diagenesis in the Atlantic Ocean: diagenetic potential and transformations. In Deep Sea Drilling Results in the Atlantic Ocean: Continental Margins and Paleoenvironment 315–340 (Am. Geophys. Union, 1979).

Mizutani, S. Kinetic aspects of diagenesis of silica in sediments. J. Earth Sci. Nagoya Univ. 15, 99–111 (1967).

Mizutani, S. Silica minerals in the early stage of diagenesis. Sedimentology 15, 419–436 (1970).

Murata, K. J. & Nakata, J. K. Cristobalitic stage in the diagenesis of diatomaceous Shale. Science 184, 567–568 (1974).

Inoue, M. Crystallization and recrystallization of siliceous sponge spicules in some marine sediments of Japan. J. Geol. Soc. Jap. 79, 277–286 (1973).

Mikami, T., Mukai, K., Tokuta, N. & Imoto, N. Relationships among quartz crystallinity index, grain size of quartz, and conodont color alteration index of bedded cherts in the Tanba Belt Southwest Japan. J. Geol. Soc. Japan 108, 806–812 (2002).

Sharav, D., Tsukada, K., Oyunchimeg, T., Manchuk, N. & Otgonbaatar, D. Quartz crystallinity of radiolarian chert in the Ulaanbaatar terrane. Bull. Geol. Mongolia 61, 186–193 (2019).

Geological Survey of Japan (ed.) Seamless Digital Geological Map of Japan 1: 200, 000. (Geol. Surv. Jap., 2020).

Khanchuk, A. I., Ratkin, V. V., Ryazantseva, M. D., Golozubov, V. V. & Gonokhova, N. G. Geology and Mineral Deposits of Primorsky Krai (Territory). (Far East Geol. Inst., Rus. Academy Sci., 1996).

Kojima, S. et al. Geological relationship between Anyui Metamorphic Complex and Samarka terrane Far East Russia. Island Arc 17, 502–516 (2008).

B. Dorjsuren, B. Bujinlkham, Ch. Minjin & Tsukada, K. Geological setting of the Ulaanbaatar terrane in the Hangay-Hentey zone of the Devonian accretionary complex, central Asian Orogenic belt. Tomurhuu, D., Natal’in, B.A., Ariunchimeg, Y., Khishigsuren, S., and Erdenesaikhan, G. (eds.), Structural and Tectonic Correlation Across the Central Asia Orogenic Collage: Implications for Continental Growth and Intracontinental Deformation (Second International Workshop and Field Excursions for IGC Project 480), Abstract and Excursion Guidebook, 39–42 (Institute of Geol. Min. Res., Mongolian Academy of Sci., 2006).

Kurihara, T. et al. Upper Silurian and Devonian pelagic deep-water radiolarian chert from the Khangai-Khentei belt of Central Mongolia: evidence for Middle Paleozoic subduction–accretion activity in the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Asian Earth Sci. 34, 209–225 (2009).

Umeda, K. et al. Permian-Triassic adakitic igneous activity at Northern Mongolia: Implication for Permian-Triassic subduction system at the Siberian continental margin. J. Geodynam. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jog.2022.101918 (2022).

Kouketsu, Y. et al. A new approach to develop the Raman carbonaceous material geothermometer for low-grade metamorphism using peak width. The Island Arc 23, 33–50 (2014).

Kano, K. Stratigraphy of the upper Paleozoic-Mesozoic strata in the northern Kiso-Azusagawa district Nagano prefecture. J. Geol. Soc. Jap. 81, 285–300 (1975).

Otsuka, T. Upper Paleozoic and Mesozoic strata in the northeastern part of the Mino Terrane, Nagano prefecture, central Japan. J. Geol. Soc. Jap. 91, 583–598 (1985).

Otsuka, T. Deformation of the Mesozoic strata in the northeastern part of the Mino-Ryoke Terrane, Nagano prefecture, central Japan. News Osaka Micropleontol Sp. 7, 187–196 (1986).

Takeuchi, M., Nakano, S., Harayama, S. & Otsuka, T. Geology of the Kiso- Fukushima district with Geological Sheet Map at 1:50,000. 94p (Geol. Surv. Jap., 1998).

Imoto, N., Shimizu, D., Musashino, M. & Ishida, S. Geology of the Kyoto seihokubu district with Geological Sheet Map at 1:50,000. 84p (Geol. Surv. Jap., Tsukuba, 1989).

Matsuda, T. & Isozaki, Y. Well-documented travel history of Mesozoic pelagic chert in Japan: From remote ocean to subduction zone. Tectonics 10, 475–499 (1991).

Kojima, S. et al. Pre-Cretaceous accretionary complexes. in The Geology of Japan, 61–100 (Geol. Soc. London, London, 2016).

Isozaki, Y. Jurassic accretion tectonics of Japan. Island Arc 6, 25–51 (1997).

Maruyama, S. et al. A new perspective on metamorphism and metamorphic belts. Gondwana Res. 18, 106–137 (2010).

Passchier, C.W. Microtectonics. 289p (Springer, 1995).

Miyazaki, K. Textural evolution of metemorphic rocks due to Ostwald ripening. J. Min. Soc. Jap. 24, 107–115 (1996).

Shimazu, M. Relationship between the particle size and the X-ray diffraction intensity of the quartz powders treated with NaOH solution, and the structural disturbance of crushed microparticles of quartz. J. Min. Soc, Jap. 6, 259–276 (1963).

Sakaguchi, A. et al. Seismic slip propagation to the updip end of plate boundary subduction interface faults: vitrinite reflectance geothermometry on integrated ocean drilling program NanTro SEIZE cores. Geology 39, 395–398 (2011).

Ferry, J. M. & Spear, F. S. Experimental calibration of the partitioning of Fe and Mg between biotite and garnet. Cont. Mineral. Petrol. 66, 113–117 (1978).

Kisch, H. J. Illite crystallinity and coal rank associated with lowest-grade metamorphism of the Taveyanne greywacke in the Helvetic zone of the Swiss Alps. Eclogae geol. Helv. 73, 753–777 (1980).

Hara, H. & Kimura, K. New proposal of standard specimens for illite crystallinity measurement: its usefulness as paleo-geothermal indicator. Bull. Geol. Surv. Japan 54, 239–250 (2003).

de Caritat, P., Hutcheon, I. & Walshe, J. L. Chlorite geothermometry: a review. Clays Clay Miner. 41, 219–239 (1993).

Wallis, S. R. & Okudaira, T. Paired metamorphic belts of SW Japan: the geology of the Sanbagawa and Ryoke metamorphic belts and the median tectonic line. The Geol Japan, 101–124 (Geol. Soc. London, 2016).

Tomurtogoo, O. Tectonic Map of Mongolia at the Scale of 1:1,000,000, and Tectonics of Mongolia (Brief Explanatory Notes to Tectonic Map of Mongolia at the scale of 1:1,000,000) (Mineral Resources Authority of Mongolia, 2003).

Tsukada, K. et al. Geological setting of basaltic rocks in an accretionary complex, Khangai-Khentei Belt Mongolia. Island Arc 22, 227–241 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Emeritus Prof. S. Kojima of Gifu University, Japan, for providing his samples collected from the Anyui area, Russia. This study was conducted as a part of the master’s degree of the first author at the Nagoya University and the second author at the Mongolian University of Science and Technology (MUST). We would like to thank Prof. M. Takeuchi, Prof. H. Yoshida, and Dr. Umemura from the Nagoya University, Japan, and Dr. Manchuk, N. from the MUST (Current affiliation: Mongolian Natural History Museum) for helpful discussions. We are grateful to Associate Prof. Y. Kouketsu, Nagoya University, Japan, for discussions regarding the RSCM geothermometer. The samples obtained from Mongolia were processed at the Field Research Center of MUST. Special thanks to Mr. Lodoidanzan, A. Dr. Mukhtsetseg O., and Prof. Khavalbolot K. from the MUST. We are grateful to Emeritus Prof. K. Yamamoto from the Nagoya University for his technical support during the HF-etching of the chert samples and fruitful discussions. We greatly gratitude to two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. A part of this study was supported by the Support for Research Activities and Holding Research Gatherings, the Graduate School of Environmental Studies of Nagoya University, 2023 Ito Chubei Research Grant as well as the joint research project of the Mongolia–Japan Higher Engineering Education Project (MJEED-JR22B15).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. T.: field research in Japan and Mongolia, sample processing, experiments, data processing, and draft writing. S. D.: field research in Mongolia, sample processing, experiments, and data processing. B. N.: field research in Japan and Mongolia, and sample processing. K. T.: research designing, field research in Japan, Mongolia, and Russia, sample processing, data processing, and draft writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka, H., Davaanyam, S., Nadmid, B. et al. Development of a quartz-based geothermometer for biogenic chert. Sci Rep 15, 45573 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29140-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29140-w