Abstract

Cruciferous green vegetables are considered as one of the most important consumed vegetables world-wide owing to their rich nutritive value, characteristic taste as well as health benefits. Cruciferous vegetables are rich in a myriad of bioactive phytochemicals including phenolic compounds and glucosinolates (GLS). The current work aims to assess heterogeneity in secondary metabolites profile among six cruciferous green leafy vegetables including Brassica oleracea (cabbage), B. oleracea var. Italica (broccoli), B. oleracea var. oleracea (cauliflower), B. rapa (turnip), Raphanus sativus L. (radish), and Nasturtium officinale (watercress) using UHPLC-HRMS/MS coupled with chemometric analysis. A total of 149 metabolites were identified belonging to different phytochemical classes including flavonoids, phenolic acids, steroids, anthocyanins, fatty acids/acyl esters, and GLS. Flavonoids were detected as the most abundant class in cruciferous vegetables represented by 48 peaks, especially Broccoli, cabbage and cauliflower. Radish exhibited unique flavonoid profiles including kaempferol-O-pentosylhexoside-O-deoxyhexoside, kaempferol-O-hexosyl-O-di-deoxyhexoside, and quercetin-O-tri-deoxyhexoside, along with indole-derived GLS known as methoxyspirobrassinin. Distinct phenolic acid profile was observed where di-sinapoyl-O-hexoside was detected only in turnip and broccoli, p-coumaroyl-malic acid was enriched in turnip only, and feruloyl malate and coumaroyl malate were enriched in turnip and radish. Unsupervised PCA analysis revealed distinct variation of turnip from other cruciferous samples, while OPLS-DA distinguished non-edible broccoli from edible cabbage, showing enrichment of neoglucobrassicin and malic acid in broccoli and higher flavonoid and anthocyanin levels in cabbage. These findings highlight the metabolic diversity of cruciferous leaves and support the valorization of underutilized species as potential functional food resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A central question for consumers when selecting plant-based foods is whether a given plant part is commonly consumed or less frequently utilized. Recently, functional foods derived from natural sources catch the interest of both consumers and nutritional specialists as it plays a pivotal role in human diet not only because they are palatable but also due to their richness in several phytochemicals of both nutritional and health-promoting properties1. Such a revolution in functional foods manufacturing by role led to progress in quality assessment tools to ensure quality and identify new nutraceuticals. Green leafy vegetables are widely consumed worldwide either fresh or after processing or added to food recipes owing to their special taste and aroma, as well as their several health benefits2. Brassicaceae, also known as Cruciferae, is a well-known medium-sized flowering plant family that comprises ca. 360 genera, including 3709 species distributed worldwide3. Brassicaceae includes a wide variety of edible vegetables used widely in food owing to their nutritional value as being rich in vitamins (A, B1, B2, B6, C, E, and K) and minerals such as magnesium, iron, and calcium3. The most common vegetables in Brassicaceae include cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, turnip, radish, watercress, and rocket4. Owing to their richness in a myriad of phyto, macro/micronutrients i.e., vitamins, carotenoids, dietary fibers, amino acids, minerals, glucosinolates (GLS), and phenolic compounds, brassica vegetables possess both nutritional and potential health value5. Brassica vegetables encompass a large class of biologically active secondary metabolites including GLS and other sulfur containing compounds6,7. GLS (β-thioglucoside-N-hydroxysulfates) structure is composed of a β-D-glycopyranose moiety attached by sulfur-linkage to a hydroximinosulfate ester with another amino group8. GLS possess several biological activities in addition to their culinary uses attributed to their unique flavor and taste9. Owing to their richness in GLS, cruciferous vegetables are attributed several positive effects including reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease, anticancer effect against lung, stomach, bladder, and colorectal10. Despite their nutritional richness, not all Brassicaceae leaves are equally consumed. For instance, cabbage, radish, and watercress leaves are commonly eaten, while the leaves of broccoli, cauliflower, and turnip are frequently discarded as by-products7. This disparity is largely related to sensory attributes (bitterness, fibrous texture), cultural dietary preferences, and, in some cases, higher levels of antinutritional compounds, despite the fact that these leaves remain edible and potentially valuable sources of nutrients and bioactives2.

Cabbage (Brassica oleracea) is one of the most consumed edible cruciferous leafy vegetable worldwide owing to its special taste and richness in antioxidant phytochemicals11. Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) is likewise nutritionally important vegetable for its richness in vitamins A, B2, and C, minerals, in addition to phytonutrients such as polyphenols, β-carotene and α-tocopherol, and isothiocyanates12. Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. oleracea) is rich of antioxidants phytonutrients such as GLS, ascorbic acid and polyphenols13. Turnip (Brassica rapa) is a widely consumed brassica rich in GLS, flavonoids, indoles, phenolics, and essential oil14. Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leafy part is typically consumed green to encompass several chemicals including vitamins, carbohydrates, minerals, flavonoids, and GLS15. Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) is an important member of brassica vegetables rich in phytochemicals specially GLS16.

Ensuring the quality of plant-based functional foods, including chemical attributes, is important to assess their food or nutraceutical value based on chemical composition17. Recently, metabolomics represents an important platform used to characterize the quality of food-stuff using different spectroscopic techniques such as mass spectrometry based chromatographic techniques18. Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled with high resolution mass analyzer (UPLC-MS/MS) is a platform well suited for profiling secondary metabolites. We have previously reported on the application of MS-based metabolomics in aroma and nutrients profiling in cruciferous leafy vegetables via gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) in context to edible and non-edible plants7. Compared to GC-MS that targets aroma compounds, UPLC-MS/MS technique is more suited for large molecular weight polar metabolites that account for health benefits19,20. Distribution of secondary metabolites among leafy green crucifers in the context of edible or nonedible has yet to be reported, especially targeting its GLS composition. Further application of multivariate data analysis including unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA) and supervised orthogonal projection to latent structures discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) were employed for samples’ classification. Compared with PCA, OPLS-DA has a greater capacity for marker recognition and discrimination among samples by supplying the most pertinent variables for the distinction among two class groups2.

To date, the distribution of secondary metabolites among cruciferous leafy vegetables has not been systematically reported in relation to consumption practices, particularly regarding GLSs and phenolic compounds. Here, we employed UHPLC-HRMS/MS combined with multivariate data analysis, including PCA and supervised OPLS-DA, to assess metabolic heterogeneity among six cruciferous leafy vegetables three commonly consumed (cabbage, radish, watercress) and three less commonly consumed (broccoli, cauliflower, turnip) collected from the same origin. The main goal of this study was to investigate the heterogeneity of secondary metabolites in these six cruciferous leafy vegetables, with emphasis on GLSs and phenolic compounds, and to highlight the nutritional and potential health relevance of underutilized leafy parts. Such comprehensive profiling may support the valorization of agricultural by-products and contribute to their future use in functional foods and nutraceutical development.

Results & discussion

Metabolites identification in cruciferous leaves via UPLC-MS/MS

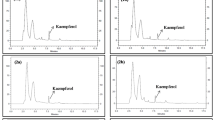

UPLC-MS/MS analysis led to the annotation of 149 metabolites in the examined cruciferous vegetables based on accurate mass, fragmentation patterns, comparison with literature, and in-house database searching. The derived base peak chromatograms for different extracts showed both qualitative and quantitative differences among the examined crucifers. Analysis was carried out in both negative (Fig. 1) and positive (Suppl. Fig. S1) ionization modes, providing greater coverage of the crucifer metabolome belonging to different classes including glucosinolates (GLS) (15 Peaks), phenolic acids (16 peaks), flavonoids (42 peaks), anthocyanidins (9 peaks), amino acids (10 peaks), fatty acids/fatty acyl glycosides (20 peaks), sulfolipids (3 peaks), and sterols (4 peaks), in addition to a number of identified metabolites belonging to different classes (Fig. 2). Due to their sulfate glucose core, Brassicaceae-specific glucosinolates ionize more readily in negative electrospray ionization mode (ESI) and can be better detected20. Also, secondary metabolites such as phenylpropanoids and flavonoids can be more readily detected in negative mode due to their relatively acidic nature. In contrast, metabolites showed improved detection in positive mode including polyamines, alkaloids, anthocyanins, and sterols, warranting the value of employing both modes in detection. Metabolite identification was based on their molecular formula, elution order, and main fragment ions in comparison to previously reported data (Table 1) and is detailed in the next subsections for each metabolite class.

Phenolic acids and their glycosides

The negative ionization mode led to the detection of 16 phenolic acids either free or conjugated with sugars and/or organic acids. The major phenolic acids detected in cruciferous leafy vegetables included quinic acid (peak 9) [(M-H)− m/z 191.0566 (C7H11O6)−], cinnamic acid (peak 28) [(M-H)− m/z 147.0456 (C9H7O2)−], and ferulic acid (peak 102) [(M-H)−m/z 193.0506 (C10H9O4)−]. Phenolic acid glycosides were also detected in gentisic acid-O-hexoside (peak 32) [(M-H)− m/z 315.0737 (C13H15O9)−], vanilllic acid-O-hexoside (peak 33) [(M-H)− m/z 329.0884 (C14H17O9)−], feruloyl-O-hexoside (peak 61) [(M-H)−m/z 355.1042 (C16H19O9)−], and caffeoyl-O-hexoside (peak 109) [(M-H)− m/z 341.0915 (C15H17O9)−] with the main fragment ion peaks at m/z 153.0194, m/z 167.0351, m/z 193.0520, m/z 223.0560 and 180.9824, respectively, corresponding to the deprotonated phenolic acid aglycone. Sinapic acid and sinapoyl esters are commonly reported in Brassicaceae family21,22, and to account for its leafy taste. Several sinapic acid glycosidic conjugates were annotated including sinapoyl-O-hexoside (peak 69)[(M-H)−m/z 385.1133 (C17H21O10)−] with fragment ion at m/z 223.0560 [M-H-162]− of deprotonated sinapic acid,, and peak 104 for sinapoyl-O- malate[(M-H)− m/z 339.0741 (C15H15O9)−] that was detected only in turnip with fragment ion peak at m/z 223.0618 of deprotonated sinapic acid. Malate esters were likewise detected in phenolic acids including p-coumaroyl-malic acid (peak 101) [(M-H)− m/z 279.0526(C13H11O7−)−] found exclusively in turnip, and feruloyl-O-malate (peak 105) [(M-H)− m/z 339.0741 (C15H15O9)−], based on the main loss of 116 amu corresponding to malic acid moiety. The examined 6 Brassicaceae samples showed qualitative differences in phenolic acid esters, in which feruloyl malate [(M-H)− m/z 339.0741 (C15H15O9)−] and coumaroyl malate [(M-H)− m/z 339.0741 (C15H15O9)−] were most prominent in turnip and radish.

Organic acids such as gluconic acid (peak 2) [(M-H)−m/z 195.0507 (C6H11O7)−], malic acid (peak 10) [(M-H)− m/z 133.0331 (C4H5O5)−] and citric acid (peak 13) [(M-H)− m/z 191.0186 (C6H7O7)−] were also detected, in which gluconic acid was the most abundant acid in 3 brassica taxa including the non-edible leaves, while present at low levels in turnip, radish, and watercress. Organic acids, including malic and citric acids, play a pivotal role in food safety acting as acidulant preservative23.

Flavonoid glycosides

A total of 42 flavonoids were annotated, of which 28 were flavonoid glycosides versus 14 acylated flavonoid glycosides. The identified flavonoids were mainly glycosylated derivatives of three flavonols viz., kaempferol, quercetin, and isorhamnetin, while only one apigenin conjugate was detected in turnip. The sugar moieties found in cruciferous vegetables typically occur as mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, and pentaglycosides24, they are also commonly found acylated by different hydroxycinnamic acids25, to further improve their absorption and cellular target interaction with myriad of health benefits including antimicrobial, antiparasitic, anti-inflammatory, anti-nociceptive, analgesic, and anti-complementary26. In MS/MS analysis, the nature of sugars and acyl groups could be revealed from elimination of the sugar residues, that are 162 amu for hexose (C6H10O5), 146 amu for deoxyhexose (C6H10O4) and 132 for pentose (C5H8O4),while acyl groups showed the losses of 176 amu for feruloyl, 162 amu for caffeoyl, 146 amu for p-coumaroyl, 206 for sinapoyl, 192 amu for methoxycaffeoyl and 116 for malic acid moieties. Analysis of crucifers revealed that the highly glycosylated flavonoids, including tetra- and penta-hexosides are more characteristic of the four Brassica taxa, albeit not detected in radish and watercress. In detail, highly glycosylated non-acylated flavonoids were found in negative mode as tetra-glycosides of quercetin, kaempferol, and isorhamnetin in peaks 40 with m/z 933.2563, peak 41 with m/z 933.2478, peak 99 with m/z 933.1791,and peak 66 with m/z 887.2451(C38H47O24). MS2 Fragment ions further distinguished between structural isomers in peaks 39, 45 and 99. For example in case of peak 40, fragment ion at m/z 771 [M-H-162 (C6H10O5)]−, m/z 609 [M-H-162 (C6H10O5)−162 (C6H10O5)]−, m/z 489 [M-H-162 (C6H10O5)−162 (C6H10O5)−120]− and aglycon fragment ion of kaempferol at m/z285 [M-H-162 (C6H10O5)−162 (C6H10O5)−324 (C12H20O10)]− was assigned as kaempferol-O- dihexoside–di-O-hexoside. While MS2 fragment ions for peak 41 at m/z 771 [M-H-162 (C6H10O5)]−, m/z 447 [M-H-162 (C6H10O5)−324 (C12H20O10)]− and m/z 301 [M-H-162 (C6H10O5)−324 (C12H20O10)−146 (C6H10O4)]− was identified as quercetin-O-dihexoside-O-hexosyl-deoxyhexoside. Peak 99 MS2 fragment ions at m/z 771 [M-H-162 (C6H10O5)]−, m/z 639 [M-H-162 (C6H10O5)−132 (C5H8O4)]−, m/z 477 [M-H-162 (C6H10O5)−132 (C5H8O4)−162 (C6H10O5)]− and m/z 315 relative to isorhamnetin post loss of another hexose moiety was identified as isorhamnetin-O-pentosyl-tri-O-hexoside (Suppl. Fig. S1).

Peak 66 showed MS2 fragment ions at m/z755[M-H-132 (C5H8O4)]−due to loss of pentose moiety, m/z593[M-H-132 (C5H8O4)−162 (C6H10O5)]−, and m/z 431[M-H-132 (C5H8O4)−162 (C6H10O5)−162 (C6H10O5)]−assigned it as kaempferol-O-pentosyldeoxyhexoside-di-O-hexoside.

A total of 14 flavonol glycosides were acylated with hydroxycinnamic acids i.e., ferulic, caffeic, sinapic, and coumaric acid. They were detected most prominent in the 4 cruciferous viz., cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, and turnip. For example, peak 36 [(M-H)− m/z 1095.2897 (C48H55O29−)−] showed MS2 fragment ions at m/z 933.2426 [M-H-162 (C9H6O3)]− due to the loss of caffeic acid moiety, m/z 787.1872 [M-H-162 (C9H6O3)- 146 (C6H8O4)]− relative to the loss of deoxyhexose sugar and m/z 463.0463 [M-H-162 (C9H6O3)- 146 (C6H8O4)−324 (C12H20O10)]− due to the successive sugar loss ultimately yielding aglycon fragment ion at m/z301 annotated as quercetin-O-caffeoyldeoxyhexosyl–O-tri-hexoside (Suppl. Fig. S2). Peak 80 [(M-H)− m/z 725.1912 (C32H37O19-)−] showed fragment ions at m/z 593.1489 [M-H-132 (C5H8O4)]− due to the loss of pentose moiety, m/z 417.0817 [M-H-132 (C5H8O4)−176 (C10H8O3)]− for the loss of acyl and pentose moieties, identified as kaempferol- O-acyl-O-di-pentoside (Suppl. Fig. S3). A number of identified flavonoids were detected only on radish this include 3 non-acylated flavonoid glycosides as in peak 75 [(M-H)− m/z 725.1937(C32H27O19−)−], peak 92 [(M-H)− m/z 739.2100 (C33H39O19−)−], and peak 93 [(M-H)− m/z 739.2052 (C33H39O19−)−], in addition to 3 acylated flavonoid glycosides as in peaks 67 [(M-H)− m/z 741.1876 (C35H33O18−)−], peak 80 [(M-H)− m/z 725.1912 (C₃₂H₃₇O₁₉-)−], peak 90 [(M-H)− m/z 739.2076 (C33H39O19−)−] Thus radish may be considered as a prospective extract with potential effects such as antimicrobial, antiparasitic, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic effects27.

A proanthocyanidin was identified in peak 128 [(M-H)− m/z 881.4929(C45H37O19−)−] with fragment ions at m/z 593 [M-H-288]− and m/z305 [M-H-288-288]− due to successive losses of catechin units with quinone methide (QM) fragmentation and appearance of gallocatechin fragment ion peak at m/z 305 identified as gallocatechin-(epi)catechin-(epi)catechin detected in all extracts except cauliflower and cabbage28 (Suppl. Fig. S8).

Anthocyanins

Anthocyanins are widely distributed as colored pigments in different fruits and vegetables29. In crucifers, anthocyanins are highly conjugated with different sugars and/or acyl groups to improve their stability30. Due to their existence in a positively charged cationic form, they are more sensitive to be detected in positive ionization mode for such flavonoid subclass29 and confirmed in this study. Nine anthocyanins were detected belonging to either cyanidin or delphinidin aglycones. For example, peak 39 [(M + H)+ m/z 935.2672 (C39H51O26+)+] showed MS/MS ions at m/z 773 [M + H-162]+, m/z 611[M + H-2 × 162 amu]+, and finally m/z 287 for its aglycone post losses of hexose moieties assigned as cyanidin-O-tetra-hexoside-identified in broccoli and cabbage (Suppl. Fig. S7). Peak 62 [(M + H)+ m/z 773.2213 (C33H41O21+)+] is a delphinidin derivative showed MS/MS ions at m/z 611 [M + H-162]+,m/z449[M + H-2 × 162 amu]+, and finally m/z303 for delphinidin aglycone post losses of deoxyhexose moiety identified as delphinidin-O-deoxyhexoside-di-O-hexoside detected in radish and watercress. Among the examined crucifers, anthocyanins were detected in radish followed by turnip, in contrast no anthocyanins were detected in cauliflower. A thorough examination for radish and turnip leaves will be of interest owing to the anti-mutation, liver protection, and inhibiting the metastasis of tumor cells properties of such metabolites31.

Glucosinolates (GLS)

GLS were detected in the negative ion mode due to the sulfate moiety showing characteristic fragment ions at m/z 275, 259, 241, 195, and 9732. Fragment ion at m/z 259 corresponded to sulfated hexose moiety, while m/z 195 was attributed to the thio-glucose moiety. A total of 15 GLS were identified to be more prevalent in non-edible crucifers than edible ones (Fig. 3). This includes peak 14 [(M-H)− m/z 422.0228(C11H19NO10S3−)−] identified as glucoiberin and detected in cabbage and turnip only. Characteristic MS2 fragment ions at m/z 358.0237 [M-H-64 (CH3SO)]− indicative of a loss of methyl sulfoxide, m/z 195.0123 of thio-glucose residue and m/z 96.6577 of the sulfate moiety led to its assignment as glucoiberin33 (Suppl. Fig. S4), first time to be reported in turnip. Another GLS found only in turnip assigned as gluconapinin peak 15 [(M-H)− m/z 372.0422 (C11H18NO9S2−)−] with MS2 product ions at m/z 292.087 [M-H-80 (SO3)]− due to the neutral loss of 80 amu (SO3), and m/z 195.057 of thio-glucose moiety (Suppl. Fig. S5), following other previously reported studies34. Peak16 [(M-H)− m/z 436.0426 (C12H22NO10S3−)−] is a prominent GLS identified in broccoli, cauliflower, watercress and radish, exhibiting the main fragment ion peak at m/z 195.0421 of thio-glucose residue and identified as glucoraphanin previously reported in Brassica species35 (Suppl. Fig. S6). Several GLS were detected exclusively in radish and warranting for future studies on vegetables targeting its GLS profile including peak 17 [(M-H)− m/z 434.0255 (C12H20NO10S3−)−], peak 64 [(M-H)− m/z 508.0958 (C16H30N2O11S3−)−], and peak 76[(M-H)− m/z 506.1129 (C17H32NO10S3−)−] identified as glucoraphenin, (methylsulfonyl)octylglucosinolate, and glucoarabin (methylsulfinyl)nonylglucosinolate. These are aliphatic GLS detected previously in cabbage18 and first time reported in radish. In contrast to aliphatic GLS that showed diversity in composition among examined crucifers, indole GLS were detected in all examined crucifers. A major indole-derived GLS detected in all examined Brassicaceae, though most prominent in radish was methoxyspirobrassin in peak 125 [M-H)− m/z 279.1610(C12H27N2 OS2−)−]. Although some of the identified GLS were first reported in radish and turnip, non-edible broccoli and cauliflower showed to have more identified GLS. This raises interest in the valorization of such by-products for further analysis. Although certain GLS were newly reported in radish and turnip, non-edible species such as broccoli and cauliflower exhibited higher GLS diversity and abundance, suggesting potential valorization of these agricultural by-products as rich sources of bioactive GLS. This observation aligns with growing interest in the recovery of functional compounds from cruciferous waste streams for nutraceutical and pharmaceutical applications.

Fatty acids and fatty acyl esters

A total of 20 fatty acids were detected in examined crucifers, exhibiting relatively minor variationamong examined taxa compared to secondary metabolites such as GLS and flavonoids. Major prominent peaks identified in all samples included peaks 124, 127, 137, and 130 of which several are newly reported in crucifers belonging to hydroxylated fatty acids. Peak 124 [M-H)− m/z 327.2721 (C18H31O5−)−] showed fragment ion peaks at m/z 309.2078 [M-H-18]− and m/z 291.1971 [M-H-18-18]− due to successive losses of water molecules, identified as trihydroxyoctadecadienoic acid most prominent in broccoli, radish, and turnip. Peak 127 [(M-H)− m/z 307 (C18H27O4−)−] showed fragment ion peaks at m/z 289.1532[M-H-18]−and m/z 235.1342 [M-H-18-18-18]− due to successive losses of water identified as hydroxy-oxo-octadecatrienoic acid being most prominent in broccoli and cabbage. Likewise, peak 137 [M-H)− m/z 295.2276 (C18H31O3−)−] with MS2 fragments at m/z 277.1036 [M-H-18]− due to loss of water and m/z 195 corresponding to OH-CH (CH2)8COO− fragment identified as hydroxylinoleic acid. Two A glycosylated oxylipid peak 145 [M-H)− m/z 417.2856 (C22H41O7−)]− are detected in all examined cruciferous leaves except for cabbage and is first time to be reported in Brassicaceae. Identification was based on main fragment ion corresponding to the loss of hexose moiety with MS2 fragment at m/z 255.232 as in case of peak 130 [M-H)− m/z 721 (C34H57O16−)−. Because fatty acids and their derivatives contribute not only to the nutritional lipid profile of cruciferous vegetables but also to their bioactivity and health-promoting effects, their identification provides an important link between metabolomic profiling and potential functional food applications.

Sulfolipids

Sulfoquinovosyl monoacylglycerols are glycolipids (SQMGs) composed of a diacylglycerol esterified with fatty acids and a sulfoquinovose moiety36. Three sulfolipids were identified in extracts that are first time to be reported in Brassica showing improved detection in negative mode and suggestive the sulphur is incorporated in lypophilic metabolites in crucifers. MS/MS spectrum of peak 142 [M-H)− m/z 791.4956 (C41H75O12S−)− showed fragment ions at m/z 537 corresponds to loss of (C16:0) fatty acid and m/z 249 corresponds to the deprotonated sulfoquinovose identified as SQDG (16:1/16:0) and was detected only in non-edible broccoli and cauliflower. Indeed, broccoli, cauliflower and turnip were the most rich in SQMGs exemplified by SQDG (18:3/16:0) in peak 143[(M-H)- m/z 817.424 (C43H77O12S−)− showing fragment ions at m/z 539, m/z 561corresponding to [M–RCOOH]– where RCOOH are the C18:3 and C16:0 fatty acids, respectively, and a fragment ion peak at m/z 297.2425 [539–243 (C6H11O8S)]-, due to the loss of sulfoquinovosyl anion (Suppl. Fig. S9). In contrast, peak 144 [(M-H)- m/z 819.436 (C43H79O12S−) showed fragment ions at m/z 566.3446, m/z 540.3283 corresponding to [M–RCOOH-H]– where RCOOH are the C18:1 and C16:1 fatty acid, respectively, identified as SQDG (18:1/16:1) was detected in all most extracts. Within examined extracts, broccoli and cauliflower appeared most rich in sulfolipids, and yet to be tested for their role in health effects or to be targeted for isolation from these sources37.

Nitrogenous compounds

A total of 6 nitrogenous compounds were detected exclusively in cauliflower and radish including peak 56 [(M-H)− m/z 452.1662 (C14H30NO15−)−] with MS2 fragments at m/z 362, 184and179, peak 58 [(M-H)− m/z 372.1271 (C16H22NO9−)−] and peak 73 [(M-H)− m/z 210.0787 (C10H12NO4−)−] with 162 amu mass differences, and annotated as methoxytyrosin-O-hexoside and methoxytyrosin, respectively, posing cauliflower and radish as potential sources of these amino acid conjugates. Although the presence of methoxylated derivatives of tyrosine and related amino acids is previously reported in Brassica38, methoxytyrosin-O-hexoside and methoxytyrosin are first time to be identified in cauliflower and radish.

Multivariate data analysis of cruciferous leaves UPLC-MS/MS metabolite dataset

Unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA) model was employed to assess metabolite heterogeneity among examined crucifer leaves. Further, supervised orthogonal projection to latent structures discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was employed for classification between edible and non-edible cruciferous, alongside identification of markers.

Unsupervised PCA analysis of crucifer leaves

A PCA model (Fig. 4) was performed for both positive and negative metabolite datasets, resulting in two independent PCs with R2 = 0.799 and Q2 = 0.607, and R2 = 0.717 and Q2 = 0.499, respectively. The PCA score plot of the negative mode dataset (Fig. 4A) revealed clear differentiation of turnip on the left side of PC1, indicating its distinct composition compared to other cruciferous situated in five separate clusters consisting of radish, watercress, cabbage, broccoli, and cauliflower along PC2. Metabolites that influenced segregation were revealed from the corresponding loading plot (Fig. 4B) indicating that some polyphenols such as ferulic acid derivatives (peak106), rhamnetin-O-hexoside (peak113), as well as tri-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (peak124) were enriched in turnip, turnip, and posing as a rich source of polyphenols in crucifers, yet to be tested using proximate assays for phenolics. In contrast, the presence of gluconic acid accounted for cabbage, broccoli, and cauliflower separate clustering on the positive side of PC1. Gluconic acid was detected at relatively much higher levels in these crucifers compared to turnip, though of less taxonomical value as primary metabolite.

Unsupervised multivariate data analyses of the studied cruciferous leaves derived from modeling secondary metabolites dataset analysed via UHPLC-HRMS/MS. (A) PCA score plot of positive mode with PC1 vs. PC2. (B)Loading plot for positive mode providing variant peaks and their assignments. (C) PCA score plot of negative mode with PC1 vs. PC2. (D)Loading plot for negative mode providing variant peaks and their assignments.

Similarly, PCA score plot for positive mode (Fig. 4C) confirmed the distinct turnip composition, being positioned far to the left of PC1. The close segregation of broccoli and cabbage on the positive left side implied similar metabolite composition and suggests that nonedible broccoli leaves share similarities with edible cabbage. Analysis of the corresponding loading plot (Fig. 4D) revealed richness in cyanidin-O-dihexoside-O-dihexoside and phenylalanine-O-hexoside in turnip. In contrast, the segregation of broccoli and cabbage was influenced by their richness in indole-acetic acid (peak 122). Additionally, loading plot revealed acyl carnitines exemplified by glutaroyl-carnitine (peak 21), fructosyl-valine (peak18), and methylmalonylcarnitine peak 12 in radish, cauliflower, and watercress posing them as potential source of acylcarnitines, especially considering their anti-obesity effects as they play a pivotal role in energy production and metabolism of fatty acids39.

Supervised OPLS-DA modelling of crucifer leaves

Compared to unsupervised PCA analysis, OPLS-DA allows for the maximum separation between groups and can identify key metabolites that contribute to the differentiation in a supervised pairwise manner. The first OPLS-DA model was developed to confirm turnip marker metabolites that showed distinct separation from other cruciferous vegetables in PCA analysis (Fig. 4). OPLS-DA Models were constructed for positive (Fig. S10A) and negative (Fig. S10C) ion mode dataset revealed distinct separation of turnip from other crucifers along the predictive component. The models showed high predictive capability with Q2 = 0.98, R2Y = 0.99 and Q2 = 0.99, R2Y = 0.99, for positive and negative datasets, respectively. Moreover, permutation tests confirmed the robustness of the models with negative Q2 intercept values and further validated the significance of the observed separation between turnip and other cruciferous vegetables. CV-ANOVA tests with p values less than 0.05 indicated model significance, further supporting the observed separation between turnip and other cruciferous vegetables. Metabolites that influence such patterns can be verified from the respective loading S-plots of negative (Fig. S10B) and positive (Fig. S10D) datasets. Interestingly, mostly polyphenols viz. ferulic acid, and rhamnetin–O-hexoside and cyanidin-O-dihexoside-O-dihexoside, that appeared to be significantly higher in turnip compared to other crucifer vegetables, and in agreement with PCA results. In addition, turnip was also enriched in primary metabolites viz. tri-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid and phenylalanine-O-hexoside, which further contribute to its unique metabolite composition compared to other cruciferous vegetables.

The second OPLS-DA model aimed to analyze metabolite composition of cabbage as an edible cruciferous vegetable and compared with other vegetables. The OPLS-DA analysis (Fig. S11) revealed clear differentiation of cabbage and other cruciferous vegetables, indicating that cabbage has a distinct flavonoid composition. Of these flavonoids, quercetin-O-deoxyhexosyl-O-hexoside, quercetin-dihexoside-O-deoxyhexoside were enriched in cabbage compared to other crucifers/quercetin has potential antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, in addition to anti-cancer properties40. Other metabolites belonging to fatty acids i.e. stearidonic acid and hydroxylinolenic acid were found enriched in cabbage compared to other cruciferous vegetables. Another OPLS-DA (Fig. S12) was employed to model broccoli against other edible crucifers, showing clear separation of broccoli along the predictive component. Key markers for broccoli included quinic acid, neoglucobrassicin, and indole acetic acid.

A final OPLS-DA comparison was adopted to model cabbage as an example of edible cruciferous vegetable in one class against broccoli as non-edible crucifer in another class (Fig. S13). Clear separation was observed attributed to quercetin-O-deoxyhexosyl-O-hexoside, quercetin-dihexoside-O-deoxyhexoside, and gluconic acid richness in cabbage.

Marker metabolites quantification and statistical analysis

The one-way ANOVA results revealed highly significant differences (FDR-adjusted p < 0.001) among cruciferous species for all identified marker metabolites (Table 2), confirming strong metabolic differentiation within the dataset. The abundance of top 10 significant metabolites based on peak area was listed in Table S1. Phenolic acids and flavonoid glycosides are the major contributors to interspecies metabolic variability within cruciferous vegetables. The boxplots of marker metabolites detected in the negative ionization mode (Figure S14) clearly demonstrate distinct species-dependent variations in metabolite accumulation among cruciferous vegetables. Turnip and watercress were enriched in quercetin-, rhamnetin-, and kaempferol-glycosides, while broccoli and cabbage exhibited higher levels of organic acids such as gluconic and malic acids. Lipid-derived metabolites such as trihydroxyoctadecadienoic acid and palmitoleic-linolenic-O-hexoside were more prominent in broccoli and cauliflower.

In the positive ionization mode (Table 3), all detected marker metabolites displayed highly significant interspecies differences (p < 0.001, FDR-adjusted p < 0.001), with large effect sizes (η2 > 0.92), indicating strong metabolic discrimination among cruciferous vegetables. The abundance of top 10 significant metabolites based on peak areas was listed in Table S2. The most discriminative metabolites were the anthocyanin derivatives delphinidin-O-deoxyhexoside and cyanidin-O-tetra-hexoside. Amino acid derivatives such as fructosyl-valine, hexose phenylalanine, and indole-acetic acid also showed strong species-dependent differences (η2 = 0.985–0.990). Lipid-related compounds, including monolinolenin and stearidonic acid, exhibited slightly lower but still substantial η2 values (0.974–0.981). Boxplots of the metabolites detected in the positive ionization mode (Figure S15) reveal clear interspecies differences in metabolite abundance, further emphasizing the metabolic diversity within cruciferous vegetables.

Conclusion

Secondary metabolites heterogeneity in 6 cruciferous leafy vegetables in the context of being edible and none-edible is introduced herein through UPLC-MS/MS-based metabolomics coupled with multivariate data analyses. UPLC-MS/MS analysis led to the detection of 149 peaks, including mostly phenolic acids, flavonoids, fatty acids/acyl esters, steroids, anthocyanins, and glucosinolates. Several identified metabolites are newly reported in crucifers belonging to hydroxylated fatty acids, oxylipid, sulfolipids, and tyrosine derivatives, besides a number of detected GLS for the first time in turnip include glucoiberin, and radish including (glucoraphenin, (methylsulfonyl)octylglucosinolate, and glucoarabin (methylsulfinyl)nonylglucosinolate)). Nonedible broccoli and cauliflower showed exclusively a number of identified compounds belonging to GLS, flavonoids and sulfolipids, posing them to be tested for their role in health effects or to be targeted for isolation from these sources. Turnip is shown to have a more characteristic profile based on the identified metabolites belonging to phenolic acids, sinapoyl derivatives, and anthocyanins. Multivariate data analysis revealed that turnip was the most distinct among all examined leaves. ferulic acid derivatives, and rhamnetin-O-hexoside, alongside tri-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid were key metabolites helped in discrimination of turnip from other samples. Quercetin-O-deoxyhexosyl-O-hexoside, quercetin hexoside deoxyhexoside-O-hexoside, gluconic acid, hydroxylinolenic acid, and palmitoleic-linolenic-O-hexoside were enriched in cabbage than other cruciferous leaves. Moreover, quinic acid, and neoglucobrassicin were enriched in broccoli as nonedible cruciferous vegetable while, quercetin-O-deoxyhexosyl-O-hexoside, quercetin-dihexoside-O-deoxyhexoside, and gluconic acid were enriched in edible cabbage leaves. A limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size, with only three biological replicates analyzed per variety. However, the consistent clustering and clear separation observed in the multivariate analyses (PCA and OPLS-DA) support the robustness and reproducibility of the detected metabolic patterns and have yet to be confirmed by analyzing specimens from other resources. Our study provides complementary phytochemical evidence that supports the functional components of cruciferous leaves to corroborate their utilization as functional foods or further in nutraceuticals.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Six cruciferous leaves viz. Brassica oleracea (cabbage), B. oleracea var. Italica (broccoli), B. oleracea var. oleracea (cauliflower), B. rapa (turnip), Raphanussativus L. (radish), and Nasturtium officinale (watercress) were collected from local farm in Qualuob, El-Qualuobia governorate (30.2220° N, 31.3084° E), Egypt, during October and November 2019. The botanical identification of the plants was confirmed by Prof. Dr. Rim Hamdy, Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Egypt. Fresh leaves were lyophilized and kept in airtight containers at −80 °C till preparation for UPLC-MS/MS analysis. Metabolite extraction and LC-MS analysis were conducted in 2020. Three biological replicates were analyzed for each sample. A voucher specimen was deposited at the College of Pharmacy Herbarium, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt.

Chemicals and reagents

Acetonitrile and formic acid (LC-MS grade) were obtained from J. T. Baker (The Netherlands); Milli-Q water was used for UHPLC analysis. Chromoband C18 (500 mg, 3 mL) cartridge was purchased from Macherey-Nagel (D¨uren, Germany). All other chemicals and standards were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA).

Preparation of leaf extracts for UHPLC-MS analysis

The extraction of the cruciferous leaves was performed as previously described41. Briefly, freeze dried leaves were ground with a pestle in a mortar, with 2 g of each leaf freeze dried powder homogenized with 5mL 100% MeOH containing 10 mg mL− 1 umbelliferone (an internal standard used for retention time alignment of UHPLC-MS features) using a Turrax mixer (11 000 rpm) for 20 s periods with recession time of 1 min. Extracts were then vortexed vigorously and centrifuged at 3000 g for 30 min to remove plant debris. For solid phase extraction, 500 µL were aliquoted and loaded on a (500 mg) C18 cartridge, which was preconditioned with methanol and water. Samples were then eluted using 3 µL 70% MeOH and 3 µL 100% MeOH, and eluents were evaporated to dryness under a gentle nitrogen stream. The obtained dry residue was re-suspended in 500 µL 100% methanol for further UHPLC-MS analysis.

High-resolution UPLC-MS/MS analysis

The analytical conditions for high-resolution UHPLC-MS/MS were employed as previously described41. The UHPLC analysis was performed on an Acquity UHPLC System (Waters) equipped with an HSS T3 column (100–1.0 mm, particle size 1.8 mm; Waters). The analysis was carried out by applying the following binary gradient at a low rate of 150 mL min− 1: 0–1 min, isocratic 95% A (water/formic acid, 99.9/0.1 [v/v]), 5% B (acetonitrile/formic acid, 99.9/0.1 [v/v]); 1–16 min, linear from 5 to 95% B; 16–18 min, isocratic 95% B; and 18–20 min, isocratic 5% B. The injection volume was 3.1 mL (full loop injection). Eluted compounds were detected from m/z 90 to 1000 using a MicroTOF-Q hybrid quadrupole time-of flight mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics) equipped with an Apollo- II electrospray ion source in negative and positive (deviating values in brackets) ion modes using the following instrument settings: nebulizer gas, nitrogen, 1.4 (1.6 bar); dry gas, nitrogen, 6.l min− 1, 190 °C; capillary, _5000 V (+ 4000 V); end plate offset, 500 V; funnel 1 RF, 200 Vpp; funnel 2 RF, 200 Vpp; in-source CID energy, 0 V; hexapole RF, 100 Vpp; quadrupole ion energy, 5 eV (3 eV); collision gas, argon; collision energy, 7 eV (3 eV); collision RF, stepping 150/350 Vpp (200/300Vpp), (timing 50/50); transfer time, 58.3 ms; prepulse storage, 5 ms; pulser frequency, 10 kHz; and spectra rate, 3 Hz. Internal mass calibration of each analysis was performed by infusion of 20 mL 10 mM lithium formate in isopropanol: water, 1 : 1 (v/v), at a gradient time of 18 min using a diverter valve. For Auto-MS/MS analysis, precursor ions were selected in Q1 with an isolation width of _3–10 Da and fragmented at collision energies of 15–70 eV using argon as a collision gas. Product ions detection was performed using the same settings as above, but with funnel 2 RF 300 Vpp in negative mode. Metabolites were characterized by their retention times relative to external standards, accurate MS, and the domino MS/MS spectra in comparison to our in-house database, phytochemical dictionary of natural products database, and reference literature. Levels of annotation were reported according to the guidelines of the metabolomics society compound identification work group at their annual meeting (Brisbane, Australia)42. Pattern isotopic similarity is already used in formula prediction by Bruker compass program. Metabolite annotation was accepted only when isotopic pattern fit exceeded 85%, and the observed mass error was below 10 ppm; few signals with mass deviation > 10 ppm were manually re-evaluated and excluded when confidence was low. Each crucifer species was represented by three independent biological replicates, which were extracted and analyzed separately to ensure reproducibility and robust statistical comparison.

MS data processing for multivariate data analysis

Features extraction of the examined cruciferous leaves MS files was performed using XCMS package under R 2.9.2 environment. The script employed for peak detection, alignment, and grouping of the extracted ion chromatograms (Suppl. Code S1) follows the exact steps described in 41. Normalization and Pareto scaling of the features prior to modelling were performed prior to multivariate models i.e., PCA and OPLS-DA using SIMCA-P Version 13.0 (Umetrics, Umea, Sweden).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Farag, M. A., Maamoun, A. A., Ehrlich, A., Fahmy, S. & Wesjohann, L. A. Assessment of sensory metabolites distribution in 3 cactus opuntia ficus-indica fruit cultivars using UV fingerprinting and GC/MS profiling techniques. Lwt 80, 145–154 (2017).

Baky, M. H., Shamma, S. N., Xiao, J. & Farag, M. A. Comparative aroma and nutrients profiling in six edible versus nonedible cruciferous vegetables using MS based metabolomics. Food Chem. 383, 132374 (2022).

Raza, A. et al. In the Plant Family Brassicaceae 1–43 (Springer, 2020).

Al-Shehbaz, I. A. A generic and tribal synopsis of the brassicaceae (Cruciferae). Taxon 61, 931–954 (2012).

Cartea, M. E., Francisco, M., Soengas, P. & Velasco, P. Phenolic compounds in brassica vegetables. Molecules 16, 251–280 (2011).

Bischoff, K. L. in Nutraceuticals 551–554 (Elsevier, 2016).

Baky, M. H., Kamal, A. M., Haggag, E. G. & Elgindi, M. R. Flavonoids from Manilkara Hexandra and antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 100, 104375 (2022).

Shakour, Z. T., Shehab, N. G., Gomaa, A. S., Wessjohann, L. A. & Farag, M. A. Metabolic and biotransformation effects on dietary glucosinolates, their bioavailability, catabolism and biological effects in different organisms. Biotechnol. Adv. 54, 107784 (2022).

Li, N. et al. Cruciferous vegetable and isothiocyanate intake and multiple health outcomes. Food Chem 375, 131816 (2021).

Traka, M. Health benefits of glucosinolates. Adv. Bot. Res. 80, 247–279 (2016).

Singh, J. et al. Antioxidant phytochemicals in cabbage (Brassica Oleracea L. var. capitata). Sci. Hort. 108, 233–237 (2006).

Moreno, D. A., Pérez-Balibrea, S., Ferreres, F. & Gil-Izquierdo, Á. García-Viguera, C. Acylated anthocyanins in broccoli sprouts. Food Chem. 123, 358–363 (2010).

Scalzo, R. L., Genna, A., Branca, F., Chedin, M. & Chassaigne, H. Anthocyanin composition of cauliflower (Brassica Oleracea L. var. botrytis) and cabbage (B. Oleracea L. var. capitata) and its stability in relation to thermal treatments. Food Chem. 107, 136–144 (2008).

Paul, S., Geng, C. A., Yang, T. H., Yang, Y. P. & Chen, J. J. Phytochemical and health-beneficial progress of turnip (Brassica rapa). J. Food Sci. 84, 19–30 (2019).

Banihani, S. A. Radish (Raphanus sativus) and diabetes. Nutrients 9, 1014 (2017).

Giallourou, N., Oruna-Concha, M. J. & Harbourne, N. Effects of domestic processing methods on the phytochemical content of watercress (Nasturtium officinale). Food Chem. 212, 411–419 (2016).

Bell, L., Spadafora, N. D., Müller, C. T., Wagstaff, C. & Rogers, H. J. Use of TD-GC–TOF-MS to assess volatile composition during post-harvest storage in seven accessions of rocket salad (Eruca sativa). Food Chem. 194, 626–636 (2016).

Rochfort, S. J., Trenerry, V. C., Imsic, M., Panozzo, J. & Jones, R. Class targeted metabolomics: ESI ion trap screening methods for glucosinolates based on MSn fragmentation. Phytochemistry 69, 1671–1679 (2008).

Li, Z. et al. Profiling of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of 12 cruciferous vegetables. Molecules 23, 1139 (2018).

Yu, X. et al. Determination of 18 intact glucosinolates in brassicaceae vegetables by UHPLC-MS/MS: comparing tissue disruption methods for sample Preparation. Molecules 27, 231 (2021).

Engels, C., Schieber, A. & Gänzle, M. G. Sinapic acid derivatives in defatted Oriental mustard (Brassica juncea L.) seed meal extracts using UHPLC-DAD-ESI-MS n and identification of compounds with antibacterial activity. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 234, 535–542 (2012).

Farag, M. A., Sharaf Eldin, M. G. & Kassem, H. Abou El Fetouh, M. Metabolome classification of brassica Napus L. organs via UPLC–QTOF–PDA–MS and their anti-oxidant potential. Phytochem. Anal. 24, 277–287 (2013).

Coban, H. B. Organic acids as antimicrobial food agents: applications and microbial productions. Bioprocess. Biosystems Eng. 43, 569–591 (2020).

Llorach, R., Gil-Izquierdo, A., Ferreres, F., Tomás-Barberán, F. A. & HPLC-DAD-MS/MS ESI characterization of unusual highly glycosylated acylated flavonoids from cauliflower (Brassica Oleracea L. v ar. botrytis) agroindustrial byproducts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51, 3895–3899 (2003).

Cartea, M. E., Francisco, M., Soengas, P. & Velasco, P. Phenolic compounds in brassica vegetables. Molecules 16, 251–280 (2010).

Essa, A. F. et al. Natural acylated flavonoids: their chemistry and biological merits in context to molecular Docking studies. Phytochem. Rev. 22, 1469–1508 (2023).

Essa, A. F. et al. Natural acylated flavonoids: their chemistry and biological merits in context to molecular Docking studies. Phytochem. Rev. 22, 1–40 (2022).

Rue, E. A., Rush, M. D. & van Breemen, R. B. J. P. r. Procyanidins: A comprehensive review encompassing structure Elucidation via mass spectrometry. Phytochem. Rev. 17, 1–16 (2018).

Mansour, K. A., Moustafa, S. F., Abdelkhalik, S. M. & High-Resolution UPLC-MS profiling of anthocyanins and flavonols of red cabbage (Brassica Oleracea L. var. Capitata f. rubra DC.) cultivated in Egypt and evaluation of their biological activity. Molecules 26, 7567 (2021).

McDougall, G. J., Fyffe, S., Dobson, P. & Stewart, D. Anthocyanins from red cabbage–stability to simulated Gastrointestinal digestion. Phytochemistry 68, 1285–1294 (2007).

Zhuang, H. et al. Differential regulation of anthocyanins in green and purple turnips revealed by combined de Novo transcriptome and metabolome analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 4387 (2019).

Francisco, M. et al. Simultaneous identification of glucosinolates and phenolic compounds in a representative collection of vegetable brassica Rapa. J. Chromatogr. A. 1216, 6611–6619 (2009).

Velasco, P. et al. Phytochemical fingerprinting of vegetable brassica Oleracea and brassica Napus by simultaneous identification of glucosinolates and phenolics. Phytochem. Anal. 22, 144–152 (2011).

Dejanovic, G. M. et al. Phytochemical characterization of turnip greens (Brassica Rapa ssp. Rapa): A systematic review. PLoS One. 16, e0247032 (2021).

West, L. G. et al. Glucoraphanin and 4-hydroxyglucobrassicin contents in seeds of 59 cultivars of broccoli, raab, kohlrabi, radish, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, kale, and cabbage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 52, 916–926 (2004).

Shakour, Z. T. A. et al. Dissection of Moringa Oleifera leaf metabolome in context of its different extracts, origin and in relationship to its biological effects as analysed using molecular networking and chemometrics. Food Chem. 399, 133948 (2023).

Bergé, J., Debiton, E., Dumay, J., Durand, P. & Barthomeuf, C. In vitro anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative activity of sulfolipids from the red Alga porphyridium cruentum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 50, 6227–6232 (2002).

Wiesner, M., Hanschen, F. S., Schreiner, M., Glatt, H. & Zrenner, R. Induced production of 1-methoxy-indol-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate by jasmonic acid and Methyl jasmonate in sprouts and leaves of Pak Choi (Brassica Rapa ssp. chinensis). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 14996–15016 (2013).

Nguyen, P. J., Rippa, S., Rossez, Y. & Perrin, Y. Acylcarnitines participate in developmental processes associated to lipid metabolism in plants. Planta 243, 1011–1022 (2016).

Aghababaei, F. & Hadidi, M. Recent advances in potential health benefits of Quercetin. Pharmaceuticals 16, 1020 (2023).

Serag, A., Baky, M. H., Döll, S. & Farag, M. A. UHPLC-MS metabolome based classification of umbelliferous fruit taxa: a prospect for phyto-equivalency of its different accessions and in response to roasting. RSC Adv. 10, 76–85 (2020).

Blaženović, I., Kind, T., Ji, J. & Fiehn, O. Software tools and approaches for compound identification of LC-MS/MS data in metabolomics. Metabolites 8, 31 (2018).

Cocuron, J. C., Ross, Z. & Alonso, A. P. Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry quantification of 13 C-labeling in sugars. Metabolites 10, 30 (2020).

Oliveira, A. P. et al. Free amino acids of Tronchuda cabbage (Brassica Oleracea L. Var. Costata DC): influence of leaf position (internal or external) and collection time. J. Agric. Food Chem. 56, 5216–5221 (2008).

Kim, H. W. et al. Identification and quantification of glucosinolates in Korean leaf mustard germplasm (Brassica juncea var. integrifolia) by liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization/tandem mass spectrometry. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 242, 1479–1484 (2016).

Yi, G. et al. Root glucosinolate profiles for screening of radish (Raphanus sativus L.) genetic resources. J. Agric. Food Chem. 64, 61–70 (2016).

Li, R. et al. Glucoraphenin, sulforaphene, and antiproliferative capacity of radish sprouts in germinating and thermal processes. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 243, 547–554 (2017).

Rangkadilok, N. et al. Determination of sinigrin and Glucoraphanin in brassica species using a simple extraction method combined with ion-pair HPLC analysis. Sci. Hort. 96, 27–41 (2002).

Moore, T., Le, A. & Cowan, T. M. An improved LC-MS/MS method for the detection of classic and low excretor glutaric acidemia type 1. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 35, 431–435 (2012).

Kokkonen, P. et al. Identification of intact glucosinolates using direct coupling of high-performance liquid chromatography with continuous‐flow Frit fast atom bombardment tandem mass spectrometry. Biol. Mass Spectrom. 20, 259–267 (1991).

Mageney, V., Neugart, S. & Albach, D. C. A guide to the variability of flavonoids in brassica Oleracea. Molecules 22, 252 (2017).

Nielsen, J. K., Nørbæk, R. & Olsen, C. E. Kaempferol tetraglucosides from cabbage leaves. Phytochemistry 49, 2171–2176 (1998).

Hadacek, F. Secondary or specialized Metabolites, or natural products: A case study of untargeted LC–QTOF Auto-MS/MS analysis. Cells 11, 1025 (2022).

Ferreres, F. et al. Tronchuda cabbage (Brassica Oleracea L. var. Costata DC) seeds: phytochemical characterization and antioxidant potential. Food Chem. 101, 549–558 (2007).

Ferreres, F. et al. Phenolic compounds in external leaves of Tronchuda cabbage (Brassica Oleracea L. var. Costata DC). J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 2901–2907 (2005).

Schmidt, S. et al. Identification of complex, naturally occurring flavonoid glycosides in Kale (Brassica Oleracea var. sabellica) by high-performance liquid chromatography diode‐array detection/electrospray ionization multi‐stage mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 24, 2009–2022 (2010).

Villarreal-García, D. et al. Effects of different defrosting methods on the stability of bioactive compounds and consumer acceptability of frozen broccoli. CyTA-Journal Food. 13, 312–320 (2015).

Schwartz, H. & Sontag, G. Determination of secoisolariciresinol, Lariciresinol and isolariciresinol in plant foods by high performance liquid chromatography coupled with coulometric electrode array detection. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 838, 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.03.058 (2006).

Kulma, A. & Szopa, J. Catecholamines are active compounds in plants. Plant Sci. 172, 433–440 (2007).

Heng, S. et al. Metabolic and transcriptome analysis of dark red taproot in radish (Raphanus sativus L). Plos One. 17, e0268295 (2022).

Lin, L. Z. et al. Profiling of glucosinolates and flavonoids in Rorippa indica (Linn.) Hiern.(Cruciferae) by UHPLC-PDA-ESI/HRMS n. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62, 6118–6129 (2014).

Oszmiański, J., Kolniak-Ostek, J. & Wojdyło, A. Application of ultra performance liquid chromatography-photodiode detector-quadrupole/time of flight-mass spectrometry (UPLC-PDA-Q/TOF-MS) method for the characterization of phenolic compounds of lepidium sativum L. sprouts. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 236, 699–706 (2013).

Alrifai, O. et al. Characterization and profiling of polyphenolics of brassica microgreens by LC-HRMS/MS and the effect under LED light. J. Food Bioact. 14, 60–74 (2021).

Rue, E. A., Rush, M. D. & van Breemen, R. B. Procyanidins: A comprehensive review encompassing structure Elucidation via mass spectrometry. Phytochem. Rev. 17, 1–16 (2018).

Huang, Y., Chen, L., Feng, L., Guo, F. & Li, Y. Characterization of total phenolic constituents from the stems of Spatholobus suberectus using LC-DAD-MSn and their inhibitory effect on human neutrophil elastase activity. Molecules 18, 7549–7556 (2013).

Pierson, J. T. et al. Phytochemical extraction, characterisation and comparative distribution across four Mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit varieties. Food Chem. 149, 253–263 (2014).

Ravi, B. G., Guardian, M. G. E., Dickman, R. & Wang, Z. Q. Profiling and structural analysis of cardenolides in two species of digitalis using liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 1618, 460903 (2020).

Şişek, D. Antep turpu (Raphanus sativus L.) ve fındık turpu (Raphanus sativus L. var. radicula)’nun bazı tek yıllık ve çok yıllık yabancı otlar üzerindeki allelopatik etkilerinin belirlenmesi. Zanco j. pure appl. sci. (2020).

Ateya, A., Al-Gendy, A., Kotob, S. & Hafez, A. Chemical constituents, antioxidant, antimicrobial and antiinflammatory activities of erysimum corinthium boiss.(Brassicaceae). Int. J. Pharmacogn Phytochem Res. 8, 1601–1609 (2016).

Fischer, J., Treblin, M., Sitz, T. & Rohn, S. Development of a targeted HPLC-ESI-QqQ-MS/MS method for the quantification of sulfolipids from a cyanobacterium, selected leafy vegetables, and a microalgae species. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 413, 1941–1954 (2021).

Münger, L. H., Boulos, S. & Nyström, L. UPLC-MS/MS based identification of dietary Steryl glucosides by investigation of corresponding free sterols. Front. Chem. 6, 342 (2018).

Acknowledgements

Dr. Mohamed Farag acknowledges the Alexander von Humboldt foundation, Germany.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E. M. K.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. M. H. B.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. A. S.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. S. D.: Methodology, Review & editing. M. A. F.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Plant ethics

The botanical identification of the plants was confirmed by Prof. Dr. Rim Hamdy, Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Egypt. The methods in plant collection and experimentation were carried out in accordance with the guidelines prescribed by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists and adopted by the institutional research committee.w.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baky, M.H., Kabbash, E.M., Serag, A. et al. Unveiling crucifer metabolomes via UPLC-HRMS/MS and chemometric analysis of edible and non-edible varieties. Sci Rep 15, 43481 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29178-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29178-w