Abstract

Pain associated to injuries is a complex experience that combine both objective and-subjective elements and which strongly affects rehabilitation outcomes of sport injuries. It may affect directly (e.g., reducing range and strength of the movements involved in the physical therapy), or indirectly (e.g., decreasing adherence, reducing psychological readiness). Cognitive factors such as rumination and catastrophic thinking may affect the perception of pain and play a role in athletes management of pain during this journey. This study is aimed at longitudinally examine the predictive role of ruminative and catastrophism thinking in the perception of pain among injured athletes. A total of 22 injured male soccer players were recruited (Mean age = 20.3 years old; SD = .991). The assessment instruments used were ad hoc questionnaire of personal and sports-related variables; a questionnaire of current injury and sports injury history; the Pain Catastrophism Scale (PCS); the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS); and the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) of Pain. The results showed a significant relationship between catastrophism, ruminative responses, and the perception of pain in injured athletes. Athletes with higher levels of catastrophism and rumination consistently reported a greater perception of pain. These results highlight the importance of targeted and tailored personalized psychological interventions for pain management to improve the rehabilitation process outcomes. Addressing individual coping strategies could improve recovery outcomes and support a more effective return -to-sport process.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Sustaining a sport injury (SI) is as multifaceted event in which the athlete plays an active role, potentially facilitating or hindering their recovery and return to sport1,2. The rehabilitation process demands time, effort and dedication3,4,5, involving cognitive, emotional and behavioural processes6,7 that impact athletes’ rehabilitation outcomes8. The psychological readiness playing a crucial role not only in a successful return to sport but also in the prevention of future injuries9,10.

In the context of SI rehabilitation, pain can pose a substantial threat to proper adaptation, effective rehabilitation, and successful return to sport11,12,13. Moreover, pain extensively contributes to the general athlete’s quality of life and wellbeing14,15. having significant physical, psychological, and emotional effects on almost every aspect of recovery16,17.

Different theoretical models aim to explain the interplay between biological, psychological and social factors in pain experience18 and how coping strategies may affect the pain experience19. Catastrophizing is one of these cognitive appraisals that affect the intensity, course and experience of pain20. Catastrophizing is defined as “an exaggerated negative “mental set” brought to bear during actual or anticipated pain experience”21. Catastrophizers tend to intensify their pain sensations and amplify the perceived threats supposedly associated to them22,23. Catastrophizing comprises: magnification and rumination, the affective components, and helplessness, the evaluative component24, with rumination itself considered a maladaptive form of self-reflection25.

Catastrophism seems to affect the attentional mechanisms related to pain26and it is associated with a threatening interpretation of pain and hypervigilance, magnifying the perception of that pain. Assa et al27. reported a negative correlation between catastrophizing thoughts and pain threshold. Similarly, Coronado et al28. found a significant but low correlation between catastrophizing and activity-related pain. However, in situations where pain is experimentally induced or embedded in a controlled activity, it may not be perceived as threatening, so these findings may not fully translate to injured athletes.

Catastrophizing also influence recovery. Kendall et al29. found that the higher participants scored on catastrophizing the longest the period they needed when they explored the effects of several psychological variables in the short-term recovery from surgery. Catastrophizing thoughts can trigger non-adaptive emotional and behavioral responses to the sport injury rehabilitation process, potentially jeopardizing an effective recovery30. Everhart et al31. observed that sport injured athletes with higher catastrophism scores were significantly less likely to return to their previous level of sport activity after surgery.

Hence, understanding the role of catastrophism and rumination in injured athletes and their relation to pain perception is crucial for optimizing the rehabilitation. The current study aims to explore the predictive role of catastrophism and ruminative responses on the perception of pain among injured athletes. Given that pain perception is dynamic and varies over time, this is a longitudinal study which monitors the progression of pain perception throughout a 21-day period of rehabilitation. It’s hypothesized that both ruminative and catastrophism are positively related with the perception of pain in injured athletes.

Methods

Participants

The participants in this study were federated football players who were injured at the time of the research. Twenty-two injured male soccer players of different competition levels from Murcia (Spain) were recruited. 13 played youth soccer and 9 played senior soccer. The mean age was 20.3 (SD = 0.9), with a minimum age of 16 years and a maximum age of 29 years.

On average, participants had played their sport at the higher competitive level for 1.8 years (SD = 0.7) while the average number of years they had been continuously practicing the sport was 11.4 years (SD = 1.0, ranging from 1 to 19 years). The average of weekly training days was 3.3 days (SD = 0.7) with an average of daily sessions of 2.6 h (SD = 0.7).

The participants had suffered a moderate to severe injury and did not have any chronic illness or psychiatric disorder. Regarding the injury, 14 athletes had sustained a very serious injury (more than 4 months of sports leave), and 8 a moderate or serious injury (between one to three months of sports leave). There were 4 athletes with a fracture, 4 athletes with sprains, 3 athletes with a muscle injury and 11 athletes with other types of injuries. The average number of injuries in the last two seasons was one injury.

All participants were informed of the purpose of the study and of the confidentiality of both their responses and the data obtained previously. Informed consent was obtained from each participant and, in the case of underage athletes, also from their parents. All procedures adherence to ethical standards and were approved under the correspondence author’s university’s IRB protocol CEI-2623–2019.

Instruments

Ad hoc sociodemographic and sports questionnaire. It collected information on age, sex, number of years practicing sports at the highest competitive level, number of years practicing federated sport continuously, training frequency per week and training duration per day.

Ad hoc current and previous injury history questionnaire32,33. This questionnaire gathered the current injury type (muscle, fracture, tendonitis, contusion, sprain or others) and the severity. Severity is categorized according to the number of days off into mild (one day without training), moderate (at least 6 days without training), serious (one to three months of sports leave) and very serious (more than 4 months of sports leave). The questionnaire also recorded the number of sports injuries suffered in the last two seasons.

The Spanish version of Ruminative Response Scale (RSS)34. The short version of this scale was adapted and validated into Spanish35. It measures ruminative style trait. People scoring high in this scale show frequent and excessive focusing on the causes and consequences of symptoms. This scale showed an internal consistency of α. = 0.93. The scale produces a total score for ruminative style and two scores corresponding to two sub-scales: brooding (maladaptive) and reflection (adaptative) rumination.

The Spanish version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS)36. The original version was validated and adapted into Spanish37. This scale consists of 13 items describing different thoughts and feelings that individuals may experience when they are in pain, with 5-point scales. This instrument reflects three aspects of catastrophism: a) Rumination; b) Magnification, and c) Helplessness. It showed a good internal consistency (α = 0.818).

Visual Analogue Scale of Pain (VAS)38. A self-report scale from 0 to 10measuring individual’s perception of pain intensity. Pain is usually classified as mild (1–4), moderate (5–6) and severe (7–10)39.

Procedure

After obtaining the University of Murcia’s IRB approval (CEI-2623–2019), researchers contacted physical therapists responsible for athletes rehabilitation to assist with participants recruitment, ensuring the confidentiality of the process throughout. Soccer players were informed about the objectives of the study and those willing to participate gave informed consent. Parental consent was also obtained with. The study lasted three weeks.

Participants were invited to participate in the study within a week they had sustained the injury, provided the met the inclusion criteria: currently injured, of moderate to severe severity, and no chronic illness or mental disorder. Once selected, they had to complete the questionnaires on demographic, sport and injury-related information. They also completed the PCS and RSS and received the VAS to assess their daily pain scores to complete it in a daily basis. After one week, athletes were contacted, Catastrophizing and Rumination were reassessed, VAS records were checked, and they were instructed to complete the VAS another week and appointed to a week later. The same procedure was followed in that week.

All methods performed in this manuscript has been carried out according with the relevant guidelines and regulations existing for carrying out these study.

Statistical analysis

We conducted descriptive statistical analyses for perceived pain, for the total sample and by group. No missing values were found in our dataset. To study the effect of the factors (reflective rumination, maladaptive rumination, catastrophic rumination, magnification, and helplessness) on perceived pain, two-way mixed ANOVAs were conducted (with time as a within-subjects factor) with the average pain score per week.

ANOVA assumptions were previously tested through Shapiro–Wilk tests and Q-Q plots for normality, and Levene tests for homoscedasticity. The Shapiro–Wilk test was significant for the third pain measurement, but the Q-Q plot suggested reasonable alignment with the normality assumption. However, the distribution of the pain variable in the third week shows a positive skew due to two outlier cases who had much higher pain than the average. Even though ANOVA is generally robust to slight violations of normality assumptions, we must interpret the findings with caution.

The minimum effect size detectable in our study was estimated using a sensitivity analysis40. For this analysis we considered a mixed ANOVA for our 2 × 3 mixed factorial design, using a risk level α = 0.05, and a statistical power 1 – β = 0.80. The current sample size, N = 22, would allow to detect a minimum effect size of f = 0.281 (equivalent to η2 = 0.073).

We conducted the sensitivity analysis using Gpower (version 3.1.9.2)40, and performed all other statistical analyses with SPSS 25. The significance level for all inferential tests was established at α = 0.050.

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the VAS, both for the total sample and for the subgroups formed based on scores on the catastrophism and ruminative response measures. At a descriptive level, it can be observed higher average levels of perceived pain in participants with higher levels of rumination, helplessness, magnification, and self-reproach. Conversely, participants with a lower level of reflective rumination reported a higher level of pain. This pattern was consistent across all the three weeks.

A general decrease in perceived pain scores over time was also observed. It is also worth noting that the perceived pain for the first week in the high-scoring groups on the three subscales of catastrophizing is consistently reported at a moderate to severe level, and the same applies to rumination-brooding. Likewise, participants with lower levels of rumination-reflective (adaptive) scores also reported higher pain during the same period (Table 1).

Tables 2 and 3 display the contrast statistics for the ANOVA tests. These tables report the following effects on VAS pain scores: the main effect of time, the main effect of group (in each subscale used), and the interaction effect between time and group.

From an inferential perspective, a significant main effect (p < 0.050) of the grouping variable was found on Pain Catastrophism – Helplessness (which explains 25.5% of pain score variance), Pain Catastrophism –Magnification (40.9% of explained variance), and Ruminative Response—Brooding (18.8% of explained variance).

Over the time, a significant decrease (p < 0.001) in perceived pain scores was observed. This time effect explains between 63.9% and 74.6% of the variance in pain scores (Table 2 and Table 3).

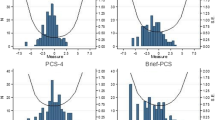

In addition to the main effects, a significant interaction effect between time and the level of Magnification on perceived pain scores was found. This interaction effect must be interpreted through the calculation of simple effects. The difference between the high and low levels of Magnification was significant in Week 1 (p = 0.001), Week 2 (p = 0.001), and Week 3 (p = 0.025). When comparing the change in perceived pain scores over time, we observe different results within each group. In the high magnification level, there was a significant decrease both from Week 1 to Week 2 (p < 0.001) and from Week 2 to Week 3 (p < 0.001). However, in the low magnification level, there was no significant decrease in perceived pain from Week 1 to Week 2 (p = 0.082), but there was one from Week 2 to Week 3 (p = 0.048). These changes can be observed descriptively in Fig. 1.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the predictive role of catastrophism and ruminative responses in injured athletes’ perception of pain, and to longitudinally analyze these relationships over a period of 21 days. According to our results, athletes with higher levels of catastrophism and maladaptive rumination perceived significantly greater pain. Previous research has related catastrophizing to the amplification of the perception of pain in different pain-related conditions and even to increased use of pain-related healthcare services in otherwise healthy adults23. Therefore, our results underscore how adaptive vs. maladaptive coping strategies strongly affect pain-related outcomes19 and highlight the role of psychosocial variables in pain perception and management12,41. The results obtained should have a direct impact on the design of clinical, rehabilitation team and psychological interventions.

Our results also showed that, during the first week after sustaining the injury, the levels of perceived pain were moderate to severe in athletes with higher catastrophizing scores, either in rumination, magnification, or helplessness, while athletes scoring lower in each of the catastrophizing subscales scored just only mild levels of perceived pain. A similar trend was found with the Ruminative Response Scale: those showing higher levels of ruminative brooding reported moderate levels of pain while those with lower scores experienced mild level of pain. Adaptive reflective rumination showed the opposite though there were no significant differences between the two groups.

It is also worth noting that our results showed an interaction between Catastrophizing-Magnification and Week. This means that either group reduced the perception of pain as time progresses, but the pattern differed. The group showing higher scores sharply reduced their pain perception from severe to mild levels. This change was not just statistically significant but also clinically meaningful42. In contrast, the low Magnification group experienced mild level of pain from the start, with only slight reductions thereafter.

These results emphasize the importance of identifying athletes’ coping profiles during the rehabilitation to provide them with the corresponding support. Factors such as gender, competitive level, and performance orientation should also be considered43.

Pain is an extraordinary debilitating condition that impacts the life of people suffering from chronic diseases such as fibromyalgia or rheumatoid arthritis26. Nonetheless, pain also affects people suffering from acute conditions such as those who sustain severe sports injuries. In fact, pain is a pervasive and hampering barrier that can significantly impair almost every stage of the rehabilitation and the return to sport process11,13.

Catastrophism seems to affect the attentional mechanisms involved in the experience of pain26 and is associated with threatening interpretation of pain and hypervigilance mechanisms which magnify the perception of that pain. Moreover, hypervigilance has been also associated with fear-avoidance processes which have shown to result in poor behavioral performance, muscular reactivity and physical disuse in the initiation of chronic pain disability44.

In chronic pain syndromes, where pain is appraised as threatening, the hypervigilance towards possible and current painful situations rises, leading to rumination thoughts and emotional responses related to the intolerability and helplessness of the pain experience. This may drive to greater fearful attitude towards the pain experience and the situations related to it45,46. Rumination, on the other hand, increases sensitization towards the aversive stimuli which intensifies the emotional distress and promotes fear-avoidance behaviors13.

These mechanisms are also likely to influence SI recovery, increasing emotional distress and promoting fear avoidance processes that may lead to maladaptive responses to the rehabilitation (e.g. decreasing adherence to treatment, increasing fear of reinjury). Thus, pain perception becomes a central aspect in the rehabilitation process of injured athletes12.

Various cognitive-behavioral interventions have proven to be effective in improving pain management and in reducing maladaptive coping strategies, both in chronic-pain diseases47 and in athletes’ SI rehabilitation25,48,49. The present findings highlight the relevance of individualized profiling when designing psychological interventions to improve pain management. Rather than providing a one-size-fits-all intervention, it would be more effective to tailor interventions based on athletes’ initial levels of catastrophism and rumination. This may also help address the inconsistent results obtained in previous studies49 and improve treatment adherence by using validated scales to guide decision-making50.

The current study is not without limitations. First of all, the sample size is not larger enough to use some other data analyses that may have produced a more robust result. Assuming the challenges of recruiting sport injured athletes, particularly for their participation in longitudinal studies, future work should adopt a multicentric approach to increase the number of participants and improve generalizability.

Similarly, the sample is exclusively male, so it has not been possible to consider differences in pain perception between male and female athletes. Future studies should consider these differences, as it’s known that female athletes are three times more likely to develop depression than men51 and experience depression with lower levels of pain than men52.

In the same vein, greater homogeneity in SI type and severity may have also contributed to more consistent results and future studies should focus either on specific injury types or expanding sample size to control for this variable. Moreover, reliance on self-report data introduces the possibility of bias and more accurate ecological momentary approach measures should be considered in future studies.

Finally, the period analyzed does not necessarily cover the full rehabilitation process, despite the longitudinal approach used. To standardize comparisons across participants, a fixed three-week period was used. Future studies should consider designing a follow-up tailored to the individual course of each injury.

Conclusions

Catastrophizing and rumination play a significant role in the perception of pain in injured athletes undergoing rehabilitation. Specifically, those injured athletes with higher level of catastrophizing reported significantly higher perception of pain than those with a low level of catastrophizing. These results have direct implications for the design of interventions during the rehabilitation and return to play phase, for example, through the management of the injured athlete’s coping strategies.

Both catastrophizing and rumination showed a significant temporal trend, with the perception of pain decreasing as the rehabilitation process progressed. These data that opens the door to future research in this underexplored area.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SI:

-

Sport injury

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

Podlog, L., Heil, J. & Schulte, S. Psychosocial factors in sports injury rehabilitation and return to play. Phys Med Rehabil Clin 25(4), 915–930 (2014).

Christakou, A. & Lavallee, D. Rehabilitation from sports injuries: from theory to practice. Pers Public Health 129(3), 120–126 (2009).

Zadeh, M. M., Ajilchi, B., Salman, Z. & Kisely, S. Effect of a mindfulness programme training to prevent the sport injury and improve the performance of semi-professional soccer players. Australas Psychiat 27(6), 589–595. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856219859288 (2019).

Ardern, C., Taylor, N., Feller, J. A. & Webster, K. E. A systematic review of the psychological factors associated with returning to sport following injury. Br J Sports Med 47(17), 1120–1126. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2012-091203 (2013).

Cheney, S., Chiaia, T. A., de Mille, P., Boyle, C. & Ling, D. Readiness to return to sport after ACL Reconstruction: a combination of physical and psychological factors. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 28(2), 66–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSA.0000000000000263 (2020).

Forsdyke, D., Gledhill, A. & Ardern, C. Psychological readiness to return to sport: three key elements to help the practitioner decide whether the athlete is ready?. Br J Sports Med 51(7), 555–556. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096770 (2017).

Kunnen, M., Dionigi, R. A., Litchfield, C. & Moreland, A. “My desire to play was stronger than my fear of re-injury”: athlete perspectives of psychological readiness to return to soccer following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. An Leis Res https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2019.1647789 (2019).

Wiese-Bjornstal, D. M., Smith, A. M., Shaffer, S. M. & Morrey, M. A. An integrated model of response to sport injury: Psychological and sociological dynamics. J Appl Sport Psychol 10(1), 46–69 (1998).

Zarzycki, R., Failla, M., Capin, J. & Snyder-Mackler, L. Psychological readiness to return to sport in associated with knee kinematic asymmetry during gait following ACL reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 48(12), 968–973. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2018.8084 (2018).

Josefsson, T. et al. Mindfulness mechanisms in sports: mediating effects of rumination and emotion regulation on sport-specific coping. Mindfulness 8, 1354–1363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0711-4 (2017).

Ivarsson, A., Tranaeus, U., Johnson, U. & Stenling, A. Negative psychological responses of injury and rehabilitation adherence effects on return to play in competitive athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Access J Sports Med 8, 27–32 (2017).

Levy, A. R., Polman, R. C. J. & Clough, P. J. Adherence to sport injury rehabilitation programs: An integrated psycho-social approach. Scand J Med Sci Sports 18(6), 798–809 (2008).

Taylor, J. & Taylor, S. Pain education and management in the rehabilitation from sports injury. Sport Psychol 12(1), 68–88 (1998).

Houston, M. N., Hoch, M. C. & Hoch, J. M. Health-related quality of life in athletes: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Athl Train 51(6), 442–453. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-51.7.03 (2016).

Lahuerta-Martin, S. et al. The effectiveness of nos-surgical interventions in athletes with groin pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BCM Sports Sci, Med Rehab 15, 81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-023-00684-6 (2023).

Taylor, J. & Taylor, S. Psychological Approaches to Sport Injury Rehabilitation (Aspen Publishers, 1997).

Dal Farra, F. et al. Sport and non-specific low back pain in athletes: a scoping review. BCM Sports Sci, Med Rehab 14, 216. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-022-00609-9 (2022).

Brewer, B. & Redmond, C. J. Psychology of Sport Injury (Human Kinetics, 2017).

Tan, G., Teo, I., Anderson, K. O. & Jensen, M. P. Adaptive versus maladaptive coping and beliefs and their relation to chronic pain adjustment. Clin J Pain 27(9), 769–774 (2011).

Edwards, R. R., Cahalan, C., Mensing, G., Smith, M. & Haythornthwaite, J. A. Pain, catastrophizing, and depression in the rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 7(4), 216–224 (2011).

Sullivan, M. J. et al. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain 17(1), 52–64 (2001).

Chaves, J. F. & Brown, J. M. Spontaneous cognitive strategies for the control of clinical pain and stress. J Behav Med 10, 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00846540 (1987).

Severeijns, R., Vlaeyen, J. W., van den Hout, M. A. & Picavet, H. S. J. Pain catastrophizing is associated with health indices in musculoskeletal pain: a cross-sectional study in the Dutch community. Health Psychol 23(1), 49–57 (2004).

Sullivan, M. J., Tripp, D. A., Rodgers, W. M. & Stanish, W. Catastrophizing and pain perception in sport participants. J Appl Sport Psychol 12(2), 151–167 (2000).

Nirit, G. & Defrin, R. Enhanced pain modulation among triathletes: a possible explanation for their exceptional capabilities. Pain 154, 2317–2323 (2013).

Edwards, R. R., Bingham, C. O. III., Bathon, J. & Haythornthwaite, J. A. Catastrophizing and pain in arthritis, fibromyalgia, and other rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Care Res 55(2), 325–332 (2006).

Assa, T., Geva, N., Zarkh, Y. & Defrin, R. The type of sport matters: Pain perception of endurance athletes versus strength athletes. Eur J Pain 23(4), 686–696 (2019).

Coronado, R. A. et al. Suprathreshold heat pain response predicts activity-related pain, but not rest-related pain, in an exercise-induced injury model. PLoS ONE 9(9), e108699 (2014).

Kendell, K., Saxby, B., Farrow, M. & Naisby, C. Psychological factors associated with short-term recovery from total knee replacement. Br J Health Psychol 6(1), 41–52 (2001).

Baranoff, J., Hanrahan, S. J. & Connor, J. P. The roles of acceptance and catastrophizing in rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Sci Med Sport 18(3), 250–254 (2015).

Everhart, J. S. et al. Pain perception and coping strategies influence early outcomes following knee surgery in athletes. J Sci Med Sport 23(1), 100–104 (2020).

Edwards, R. R., Fillingim, R. B., Maixner, W., Sigurdsson, A. & Haythornthwaite, J. Catastrophizing predicts changes in thermal pain responses after resolution of acute dental pain. Pain 5, 164–170 (2004).

San-Antolín, M. et al. Central sensitization and catastrophism symptoms are associated with chronic myofascial pain in the gastrocnemius of athletes. Pain Med https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnz296 (2019).

Hervás, G. Spanish adaptation of an instrument to assess ruminative style: ruminative responses scale. Rev Psicop Psic Clín https://doi.org/10.5944/rppc.vol.13.num.2.2008.4054 (2008).

Extremera, N. & Fernández-Berrocal, P. Validity and reliability of Spanish versions of the ruminative responses scale-short form and the distraction responses scale in a simple of Spanish high school and college students. Phycol Rep 98(1), 141–150 (2006).

Sullivan, M. J. L., Stanish, W., Waite, H., Sullivan, M. & Tripp, D. A. Catastrophizing, pain, and disability in patiens with soft tissue injuries. Pain 77, 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00097-9 (1998).

Olmedilla-Zafra, A., Ortega, E. & Abenza, L. Validation of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale in Spanish athletes. Cuad Psic Dep 13(1), 83–94 (2013).

Begum, M. R. & Hossain, M. A. Validity and reliability of visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain measurement. J Med Case Rep Rev 2(11), 394 (2019).

Serlin, R. C., Mendoza, T. R., Nakamura, Y., Edwards, K. R. & Cleeland, C. S. When is cancer pain mild, moderate or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function. Pain 61, 277–284 (1995).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146 (2007).

Iwatsu, J. et al. Knee pain in young sports players aged 6–15 years: a cross-sectional study in Japan. BMC Sports Sci, Med Rehab 15, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-022-00606-y (2023).

Gallagher, E. J., Liebman, M. & Bijur, P. E. Prospective validation of clinically important changes in pain severity measured on a visual analog scale. Ann Emerg Med 38(6), 633–638 (2001).

Diotaiuti, P. et al. Both gender and agonistic experience affect perceived pain during the cold pressor test. In J Environ Res Public Health 19(4), 2336 (2022).

Vlaeyen, J. W. & Linton, S. J. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain 85(3), 317–332 (2000).

Schütze, R., Rees, C., Preece, M. & Schütze, M. Low mindfulness predicts pain catastrophizing in a fear-avoidance model of chronic pain. Pain 148(1), 120–127 (2010).

Mekoilou Ndongo, J. et al. Poor quality of speep and musculoskeletal pains among highly trained and elite athletes in Senegal. BMC Sports Sci, Med Rehab. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-023-00705-4 (2024).

Jensen, M. P., Nygren, A., Romano, J. M. & Karoly, P. Coping with chronic pain: a critical review of the literature. Pain 47, 249–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(91)90216 (1991).

Jones, M. I. & Parker, J. K. Mindfulness mediates the relationship between mental toughness and pain catastrophizing in cyclist. Eur J Sport Sci 18(6), 872–881. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2018.1478450 (2018).

Petrini, L. & Arendt-Nielsen, L. Understanding pain catastrophizing: putting pieces together. Front Psychol 11, 603420 (2020).

Diotaiuti, P. et al. The use of the decision regret scale in non-clinical contexts. Front Psychol 13, 945669 (2022).

Walker, D., Qureshi, A. W., Marchant, D. & Balani, A. B. Developing a simple risk metric for the effect of sport-related concussion and physical pain on mental health. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292751 (2023).

Walker, D. & McKay, C. Interactive effects of sex and pain on elevated depressive symptoms in university student athletes. Int J Sport Exerc Ps 21(3), 428–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2022.2057571 (2022).

Funding

This work has been financed, in part, by the Football Federation of the Region of Murcia, within the framework of a research project together with the University of Murcia. Under the following code: FFRM + UMU-36731–GINVEST-12574.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EOT and ISI carried out the statistical analysis. AGM, VJR and AO, they carried out the bibliographic search of existing research that was of interest, the introduction and the references. VGE carried out the method, discussion and conclusions. All carried out the revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved from the ethical point view of the research by the Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia (Spain), with reference number CEI-2623–2019. All participants were informed of the purpose of the study and of the confidentiality of both their responses and the data obtained previously. Informed consent was obtained from the athletes and authorization from parents in the case of underage athletes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gómez-Espejo, V., Olmedilla, A., García-Mas, A. et al. Rumination catastrophism and pain in injured athletes. Sci Rep 16, 132 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29247-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29247-0