Abstract

Ethiopia is renowned for its diverse phytomedicinal resources, with traditional knowledge forming a cornerstone of primary healthcare, particularly in rural areas. In the Jabitehnan district of West Gojjam Zone, communities depend extensively on medicinal plants to manage various health conditions. However, documentation of this knowledge and the associated plant species remains limited, while environmental degradation and modernization continue to threaten their sustainability. This study aims to document the medicinal plant species used in the district, examine knowledge variations across age and gender, and evaluate conservation challenges affecting these resources. An ethnobotanical survey was conducted using both qualitative and quantitative approaches. Data were collected from 90 informants through semi-structured interviews, field observations, group discussions, and guided walks. Analytical tools including fidelity level (FL), informant consensus factor (ICF), preference ranking, direct matrix ranking, and Jaccard similarity index were employed to assess the cultural significance and conservation status of the documented species. Statistical analyses (independent t-tests, one-way ANOVA, and correlation) were performed using R software to explore differences in ethnobotanical knowledge among informant groups. The study identified 95 medicinal plant species belonging to 88 genera and 53 families. Most were used to treat gastrointestinal issues, respiratory infections, skin ailments, and reproductive health problems. Asteraceae and Fabaceae were the most represented families, and shrubs were the predominant growth form. Leaves were the most commonly used plant part, prepared mainly by pounding and squeezing. Oral administration was the primary mode of application. The highest ICF was recorded for skin-related ailments (0.87), and Kalanchoe petitiana A. Rich. showed a high FL (0.92) for wound treatment. Ethnobotanical knowledge varied significantly by informant groups (P < 0.05). Major threats to medicinal plant availability included deforestation, agricultural expansion, and unsustainable harvesting. The findings underscore the vital role of traditional medicine in local healthcare and highlight the urgent need to safeguard both the plant species and the cultural knowledge tied to them. Strengthening intergenerational knowledge transfer, promoting sustainable use, and implementing community-based conservation strategies are essential for the long-term preservation of these resources. Additionally, the study supports further pharmacological and phytochemical research on the identified species to validate and enhance their medicinal applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The global use of phytomedicines has gained significant attention due to both its cultural relevance and its potential for drug discovery and the development of alternative treatments. Many plant species that were traditionally used for medicinal purposes are now being studied for their pharmacological properties1,2,3. The World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledges the importance of traditional medicine and advocates for its integration into national healthcare systems4. Countries like China and India have incorporated traditional medicine into their national health policies, and ongoing research into the medicinal properties of plants continues to be a major focus5,6. Ethiopia, with its rich plant diversity, holds significant potential to contribute to global ethnopharmacological research, particularly in documenting and validating its phytomedicinal species for broader therapeutic applications7,8. Ethiopia stands out as one of Africa’s most biodiverse and culturally rich nations. It is home to approximately 6000 plant species, with around 12% of these species being endemic9,10,11,12. The country’s unique cultural heritage and biodiversity are closely intertwined, with phytomedicines playing a crucial role in local healthcare systems. Traditional medicine, which predominantly relies on plant-based remedies, is especially vital in rural Ethiopia, where access to modern healthcare facilities is limited13,14. The use of medicinal plants has been an essential part of Ethiopian society for centuries, with knowledge being passed down through generations. Traditional healers and community members utilize a wide array of plants to treat conditions such as malaria, digestive problems, respiratory issues, and reproductive health disorders16,17. Despite the increasing use of modern medicine, plant-based therapies remain indispensable, particularly in remote areas where conventional healthcare services are scarce or too costly15,16,17,18.

In Africa, Ethiopia stands as a prominent leader in ethnobotanical research, with studies focused on the phytomedicines of various regions, including the South, North, and Western parts of the country. However, comprehensive ethnobotanical studies in the Amhara region, particularly in West Gojjam, are still limited. Existing research has documented a wide variety of plants used to treat common ailments, yet more in-depth surveys are required to fully capture the diversity of phytomedicine knowledge and its ecological and cultural significance19,20,21,22. Jabitehnan District, situated in the fertile agricultural lands of West Gojjam Zone, has a long-standing tradition of using phytomedicines. The district’s predominantly rural farming communities rely on local plants to address a range of health issues, from minor ailments like colds to more serious conditions such as hypertension, infections, and gastrointestinal disorders. The people in this district share a deep cultural connection with their land, where knowledge of plant species and their medicinal properties is essential for daily life. While the district is home to numerous medicinal plant species, many are poorly documented or not studied in detail. Ethnobotanical research in other regions of Ethiopia has shown that knowledge of phytomedicines often varies by gender, age, education, and occupation. Elderly individuals, particularly traditional healers, possess extensive knowledge of plant species, preparation techniques, and medicinal uses10,17,23. However, younger people and those with higher levels of formal education tend to favor modern medicine, which has contributed to a growing risk of losing traditional knowledge, as traditional healing practices become less prominent24,25,26. Understanding these demographic differences is crucial for effective documentation, as it helps identify the segments of the population with the most knowledge, as well as those at risk of losing their ethnobotanical heritage. The West Gojjam Zone, part of the Amhara Region, is renowned for its rich flora and deeply ingrained traditional medicinal practices. Jabitehnan District stands out due to its unique ecological and cultural characteristics. The communities here are heavily dependent on local plant species for treating various health conditions. The knowledge of identifying, preparing, and applying these medicinal plants has been passed down through generations, primarily through oral tradition27,28. Despite this rich tradition, there is a lack of thorough scientific documentation and analysis of the phytomedicines used in the district, which hinders efforts to conserve this knowledge and explore its potential for broader medical or pharmacological use.

The preservation of traditional knowledge faces significant challenges. Modernization, cultural changes, environmental degradation, and deforestation have all contributed to the erosion of indigenous knowledge systems. Furthermore, the older generation who traditionally serves as the guardians of this ethnobotanical knowledge is aging without sufficient transmission of information to the younger generation. This issue is particularly concerning in districts like Jabitehnan, where traditional medicine plays a crucial role in community health. The decline in the use of phytomedicines, driven by habitat destruction and the lack of systematic documentation, raises important concerns about the long-term survival of both the plants and the practices that rely on them. The need to document and analyze ethnobotanical knowledge in Jabitehnan District is driven by the multiple benefits such knowledge provides. First, it plays a vital role in preserving cultural identity by recording traditional wisdom that has supported local communities for generations. Second, it serves as a foundation for both local and national conservation strategies, especially for plant species that are rare or under threat. Third, from a global pharmaceutical perspective, many plants traditionally used in Ethiopian medicine may contain valuable bioactive compounds with medicinal potential. Lastly, a deeper understanding and recognition of traditional healing practices can help improve healthcare delivery and accessibility, particularly for rural populations that rely heavily on these methods.

With this background, the present study aims to address the existing knowledge gap by carrying out an in-depth ethnobotanical survey in the Jabitehnan District. The study focuses on five main objectives: (1) to document and identify phytomedicinal plants used by the local population; (2) to explore the associated traditional knowledge, including uses, preparation techniques, and application methods; (3) to assess the conservation status of these plants and the risks they face; (4) to investigate how this knowledge is passed down between generations; and (5) to highlight plant species that could be candidates for further pharmacological research. These goals aim not only to safeguard existing ethnobotanical knowledge but also to lay the groundwork for sustainable healthcare practices and effective biodiversity conservation. To guide the research, the study is built around several key hypotheses. First, it is expected that the Jabitehnan District harbors a wide variety of medicinal plants that are still actively used by the community. Second, the research assumes that traditional knowledge is largely held by older members of the population and is in danger of disappearing due to inadequate intergenerational knowledge transfer. Third, many medicinal plant species in the district are believed to be under ecological pressure from both natural and human activities. Lastly, the study hypothesizes that some of the recorded plants may contain pharmacologically active compounds that warrant scientific exploration for potential therapeutic use.

Materials and methods

Study area description

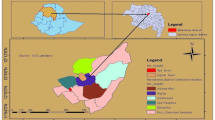

Jabitehnan District lies in the West Gojjam Zone of Ethiopia’s Amhara Region, covering about 1,600 km² between latitudes 10° 53′ 50″ N–10° 29′ 41″ N and longitudes 32° 22′ 16″ E–37° 08′ 33″ E. It borders Dembecha (southeast), Bure (west), Sekela (northwest), Kuarit (north), and Dega Damot (east) (Fig. 1). The administrative center, Finote Selam, is about 380 km northwest of Addis Ababa.

The district features diverse topography, including highland, midland, and lowland zones that support rich vegetation and numerous medicinal plant species. Administratively, it is divided into 42 kebeles, mostly rural farming communities. According to the 2007 CSA census, Jabitehnan had 179,342 residents (89,523 men and 89,819 women); recent estimates put the population at about 277,590. The Amhara ethnic group constitutes 99.51% of inhabitants, and Amharic is the primary language for 99.7%. Ge’ez is used mainly by Orthodox clergy for liturgical purposes.

Agriculture forms the backbone of the local economy. Soils include red (60%), brown (25%), and black (15%), with 27% classified as fertile, 71% moderately fertile, and 2% infertile. Land use comprises 49.8% cultivated land (58,262 ha), 4.4% cultivable (5,205 ha), 5.5% forest (6,502 ha), 17.6% bushland (20,662 ha), 9.3% settlement (10,931 ha), and 13% other uses (15,389 ha).

The district experiences a temperate climate with distinct wet (June–September) and dry (October–May) seasons. Average annual rainfall is about 1,050 mm, and means annual temperature is 21 °C, ranging from 10.3 to 33.2 °C (Fig. 2). These favorable conditions support diverse flora and fauna, making Jabitehnan an important phytomedicinal center.

Small-scale subsistence farming dominates, with major crops including maize, teff, wheat, barley, and pulses. Livestock rearing mainly cattle, sheep, and goats is also common. Many residents collect wild plants for food, medicine, and cultural uses. Traditional medicinal knowledge, deeply rooted in local culture, remains vital where modern healthcare is limited. Forests, wetlands, and bushlands are key sources of these plants, though biodiversity is increasingly threatened by deforestation, land degradation, and settlement expansion.

Medicinal plants also play central roles in spiritual and cultural practices. Sacred forests and groves, protected by local customs, contribute to biodiversity conservation. This close human–nature relationship reflects a holistic view of health, culture, and environment.

According to the Jabitehnan District Health Office (2021), acute upper respiratory infections were the most common illnesses, followed by febrile diseases, pneumonia, malaria, intestinal parasites, diarrhea, and skin infections.

Map of the study area showing Jabitehnan District, West Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia. The map was created by the authors using ArcGIS version 10.8.1 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc., Redlands, CA, USA; https://www.esri.com/). Base layers were obtained from the Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency and Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com/).

Reconnaissance survey, study site, and informant selection

Tïhis ethnobotanical study was conducted in Jabitehnan District, West Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia, to document and analyze traditional medicinal plant knowledge. Both qualitative and quantitative methods were used to collect data on plant use, knowledge variation, cultural significance, and conservation issues.

A reconnaissance survey was carried out from June 12–19, 2023, to understand the district’s biophysical and socio-cultural setting, identify suitable study sites, and establish rapport with local stakeholders. Meetings with community elders, traditional healers, and local leaders helped locate areas with intensive medicinal plant use and biodiversity hotspots. Main data collection followed between July 12, 2023, and January 29, 2024.

Purposive sampling was used to select study kebeles, focusing on areas with dense vegetation and strong phytomedicine traditions. Kebeles were chosen from both highland (Dega, > 2000 m) and midland (Woynadega, 1500–1800 m) zones to capture ecological and cultural diversity. Local health workers, elders, and healers contributed to site selection. From the district’s 39 kebeles, six were selected for detailed study: Woynma Worqima, Tach Ber Ersha Limat, Goref Kauncha, Mircha Borabur, Atat Ashiti, and Yeshert Jigur (Table 1). These rural communities preserve strong oral traditions of medicinal plant use.

Informant selection considered age, gender, education, and occupation to represent diverse knowledge holders. Participants were categorized as key informants (traditional healers with extensive expertise) and general informants (community elders and residents familiar with plant use)29. In total, 90 informants participated 15 from each kebele. Of these, 30 key informants were purposively selected based on recommendations from local experts, while 60 general informants were chosen using systematic random sampling30.

Informants were grouped by age to assess knowledge transfer across generations: young adults (20–30 years), middle-aged (31–50 years), and elders (51–90 years). Particular attention was given to younger participants to evaluate continuity of traditional knowledge22.

Participation was voluntary and based on individuals’ experience with medicinal plants and their community roles. Selection criteria were developed jointly with local leaders to ensure inclusion of knowledgeable and representative participants31.

Ethnobotanical data collection

Ethnobotanical data were collected using semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, and guided field observations. The semi-structured interviews served as the main tool, allowing flexibility to explore detailed information on medicinal plant species, preparation methods, plant parts used, and therapeutic applications. Open-ended questions encouraged informants to share traditional, cultural, and spiritual knowledge related to specific plants. All interviews were conducted in Amharic, with translations provided when necessary.

In each of the six selected kebeles, one focus group discussion was held with ten participants. These sessions enabled participants to exchange experiences, validate information, and ensure data consistency across communities. Group discussions also provided collective insights into shared practices and beliefs about medicinal plant use.

Guided field walks complemented interviews and discussions. During these walks, knowledgeable informants accompanied researchers to local sites where medicinal plants grow. Elders, community leaders, and kebele administrators assisted in identifying key local experts to lead the visits. Plants were identified, collected, and recorded in real time, allowing immediate verification and contextual discussion. Field observations also documented harvesting techniques, species distribution, and ecological conditions.

Combining interview-based and field-based methods provided a comprehensive understanding of both the practical use and environmental context of traditional medicinal plants in the study area.

Plant collection and identification

Plant specimens were collected from natural habitats and home gardens within Jabitehnan District, West Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia (10° 53′ 50″ N–10° 29′ 41″ N; 32° 22′ 16″ E–37° 08′ 33″ E). Prior to collection, permission was obtained from the Jabitehnan District Agricultural Office, local community leaders, and landowners, in accordance with ethical guidelines. Verbal consent was also secured from traditional healers and household owners who provided plant samples. Ethical clearance was granted by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Debre Markos University, and the study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and all procedures complied with national and institutional research standards.

Collection focused on plant species frequently cited by informants for medicinal use. Harvesting was done selectively, targeting specific plant parts (leaves, roots, stems, flowers, or bark) to minimize environmental disturbance and support natural regeneration32. Collected materials were pressed between layers of blotting paper, dried, and labeled following standard herbarium procedures.

Plant identification was conducted at the Mini Herbarium, Department of Biology, Debre Markos University, with assistance from local botanists and herbarium experts. Formal identification and authentication were performed by Dr. Nigussie Amsalu using The Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea and verified against reference specimens at the National Herbarium, Addis Ababa University33. Scientific names and taxonomic details were confirmed through reputable botanical databases, including Plants of the World Online, PlantNet, Flora Finder, USDA Plants Database, African Plant Database, Google Images, and the World Checklist of Selected Plant Families.

Each species was documented with its scientific name, family, vernacular name, and the plant parts used for medicinal purposes. All voucher specimens (DMUH NA 01–NA95) are securely deposited in the Mini Herbarium, Department of Biology, Debre Markos University, for future reference, taxonomic verification, and educational use.

Informant consensus factor (ICF)

The Informant Consensus Factor (ICF) was used to evaluate the level of agreement among informants regarding the use of medicinal plants for specific categories of ailments. A high ICF value implies that a few species are widely used to treat a particular condition, which may indicate both the cultural salience and potential effectiveness of those plants34,35,36. In contrast, a low ICF suggests a lack of consensus and potentially random or individualized plant usage. The ICF was computed using the following formula:

Where: Nur = Number of use-reports for a particular illness category, Nt = Number of species used for that illness category. Values range from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 denoting a higher consensus among informants.

Fidelity level (FL)

The Fidelity Level (FL) quantifies the percentage of informants who consistently report the use of a specific plant for treating a particular ailment. It reflects the degree of specificity and reliability associated with the therapeutic application of a given species. A higher FL value indicates greater agreement among informants regarding a plant’s use, suggesting its cultural and medicinal prominence within the community34,35. The FL was calculated using the formula:

Where: FL = Fidelity Level (expressed as a percentage), Ip = Number of informants who independently cited a species for a specific ailment, Iu = Total number of informants who mentioned the species for any use.

This index enabled the identification of species with high therapeutic specificity and potential pharmacological interest.

Preference ranking and direct matrix ranking

To evaluate how local communities prioritize and value medicinal plants, two participatory methods were applied: preference ranking and direct matrix ranking.

Preference ranking assessed which medicinal plants were considered most effective or frequently used for treating specific ailments35. Following the approach of36, ten key informants evaluated the effectiveness of five medicinal plants commonly used against intestinal parasites in humans. Each informant assigned a score from 1 (least effective) to 5 (most effective). The total scores were summed to determine each species’ rank, revealing the most trusted remedies within the community.

Direct matrix ranking provided a broader assessment of multipurpose medicinal plants by comparing their various uses37. Informants evaluated selected species based on attributes such as medicinal value, cultural importance, and practical applications. A table was prepared with plant species as rows and use categories as columns. Five multipurpose tree species were selected based on their frequency of mention, and ten key informants scored each species in seven categories: medicine, construction, charcoal, furniture, food, firewood, and agricultural tools. Scores ranged from 1 (least useful) to 5 (most useful).

This matrix-based analysis provided insight into the wider roles of medicinal plants in daily life and identified species most vital for conservation and sustainable use. As emphasized by26, participatory methods like these are essential for recognizing and protecting plants with diverse community value.

Jaccard similarity index

The Jaccard index was used to compare the medicinal plant species documented in this study with those reported in other regions of Ethiopia, providing a broader perspective on regional similarities and differences. The similarity was calculated using the standard Jaccard formula:

Where: JSI represents the Jaccard similarity index, which measures the degree of similarity between two study areas, a refers to the number of plant species recorded in the current study area, b denotes the number of species identified in a different study area, c represents the number of species common to both study areas.

The JSI values range from 0 to 1, with a score of 1 indicating complete similarity and a score of 0 signifying no similarity between the compared areas. To express the JSI as a percentage, the index can be multiplied by 100, providing a clearer representation of similarity levels.

Data analysis

Data collected through semi-structured interviews, field observations, and ranking exercises were analyzed using both qualitative and quantitative methods.

Thematic analysis was applied to qualitative data to identify common patterns and themes related to medicinal plant use. Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) and specialized indices, including the Fidelity Level (FL), Informant Consensus Factor (ICF), and Jaccard Similarity Index, to assess patterns of plant utilization.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.2). The Shapiro–Wilk test assessed data normality prior to statistical testing. Differences in medicinal plant knowledge between genders were analyzed using independent t-tests, while variations by educational level and years of healing experience were also examined with t-tests. One-way ANOVA was used to evaluate knowledge differences among age groups. The relationship between age and the number of medicinal plants reported was examined using Pearson correlation and linear regression8,21.

Ethical considerations

Prior to fieldwork, permission was obtained from the Jabitehnan District Administration, and ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Debre Markos University. All participants provided informed verbal or written consent after being fully informed of the study’s objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Data were recorded and used only with participants’ approval, in accordance with institutional and international ethical guidelines, ensuring the protection of their rights and welfare throughout the research process.

Results and discussion

Sociodemographic characteristics of informants

A total of 90 individuals participated in this research. Among them, males accounted for the majority, representing 71.1% (n = 64), while females made up 28.9% (n = 26). In terms of their roles, most participants (66.6%, n = 60) were categorized as general informants, with the remaining 33.4% (n = 30) identified as key informants, such as traditional healers.

The age of participants ranged from 20 to 90 years. The largest age group was between 51 and 90 years, making up 46.6% (n = 42) of the respondents. This was followed by individuals aged 31 to 50 years (32.2%, n = 29), while the remaining participants were younger adults aged 20–30. Educational backgrounds varied significantly, with the majority of informants (65.5%, n = 59) being illiterate. The remaining 34.5% (n = 31) had some level of literacy. These demographic factors are summarized in Table 1.

Transmission of traditional phytomedicine knowledge

The primary means of transferring knowledge about medicinal plants in the study area was oral, passed mainly within families. Healers often shared their expertise covering plant types, treatments, preparation methods, modes of administration, dosages, and possible antidotes with trusted family members, typically the eldest son. This information was kept confidential, as it was regarded as a source of livelihood, respect, and social status.

Most practitioners believed that sharing such knowledge beyond the family could devalue its significance or misuse it. None of the participants reported having written records about their medicinal practices. Instead, all traditional healers indicated that they had learned through oral instruction, observation, and hands-on experience from close relatives. The knowledge was typically passed down from parents or grandparents and, in turn, shared with their children using the same methods.

Among the sources of traditional medicinal knowledge, the most frequently mentioned were fathers or mothers (44.4%, n = 40), followed by grandparents (23.3%, n = 21). Siblings accounted for 15.5% (n = 14) of the knowledge transmission, while neighbors were the least cited source at only 2.2% (n = 2). These findings highlight the deeply familial nature of ethnomedicinal knowledge transmission in the community.This finding is in agreement with the report of11,38,39,40.

Cultural naming of phytomedicinal plants in the study area

In the study area, the names given to medicinal plants in local languages often reflect their uses, physical characteristics, or cultural associations. These names provide meaningful insights into the plant’s role in traditional medicine. Through examining the local terminology for various phytomedicinal species, it was found that many names directly reference the plant’s healing properties, while others describe features like stem color, leaf shape, scent, taste, or even toxicity.

All medicinal plants identified during the study were found to have names in at least one of the languages spoken in the districts. Often, these names vary slightly in pronunciation or spelling across different communities. In some instances, a single name might be used for more than one species, particularly if the plants share similar therapeutic functions. For example, the plant Buddleja polystachya Fresen. is locally called “Nech anfar”, referring to its light-colored stem (“Nech” meaning white). Rosmarinus officinalis L. is known as “Siga metibesha”, indicating its common use in flavoring meat. Asparagus africanus Lam. is referred to as “Yeset qest”, a name linked to its traditional use by women in cotton processing using a tool called Ensirt, a cultural practice still recognized in Jabitehnan district and other parts of the Amhara region. However, this traditional activity, locally referred to as “Wovera”, is now in decline due to modernization. Another example is Rumex nepalensis Spreng., known as “Yewusha milas”, which translates to “dog’s tongue” in Amharic named after the leaf’s resemblance to a dog’s tongue. Ruta chalepensis L. is called “Tena adam”, meaning “Adam’s health” or “health for mankind,” highlighting its perceived value in promoting human well-being. Stephania abyssinica (Quart.-Dill. & A.Rich.) Walp. is locally named “Yaythareg”, referencing its association with rodents, as it typically grows in areas inhabited by rats.

Studies by20,41 in the Kaffa and Sheka zones of Southwest Ethiopia have documented similar naming conventions among the people. In their tradition, medicinal plants often include the suffix “Atto”, derived from the name of the disease they are used to treat symbolizing their healing function. Additionally, health conditions related to specific organs often end with “Bewo”, indicating ailments of that body part. For instance, “Dingare atto” is the local term for a remedy used to treat snakebites or venom-related conditions in Kafficho and Shekicho people of Southwest Ethiopia.

Diversity and distribution of phytomedicinal plants in the study area

The people of Jabitehnan District displayed a remarkable depth of knowledge regarding traditional medicinal plants, identifying a total of 95 species used for treating various human ailments. These species were classified into 88 genera across 53 plant families (Table 2), illustrating the district’s rich phytomedicinal biodiversity. This level of diversity not only reflects the region’s botanical richness but also underscores the community’s strong cultural connection to traditional healing practices.

When compared to similar ethnobotanical studies conducted in other parts of Ethiopia, which recorded 73, 81, and 85 species respectively8,39,42, Jabitehnan stands out for its abundance of medicinal plant knowledge. While some global studies have identified fewer species 42 and 55 in Tanzania and China respectively43,44 other reports surpass the findings of this study. For instance, researchers like3,20,22 have reported 122, 164, and 168 phytomedicinal species in various regions, suggesting regional variations in biodiversity and ethnobotanical practices.

From a public health perspective, such a rich repository of plant-based remedies plays a crucial role in supplementing healthcare for rural and economically disadvantaged populations. Among the documented plant families, Asteraceae and Fabaceae were the most prominent, each contributing 7 species (7.5%), followed closely by Solanaceae with 6 species (6.5%) (Table 2). The prominence of Asteraceae has also been observed in other studies2,21,45. Nationally, Asteraceae followed by Fabaceae is recognized as Ethiopia’s most diverse plant family, even surpassing Poaceae and Euphorbiaceae, and is known for its wide variety of leguminous species28,46,47. This aligns with findings from earlier ethnobotanical research31,48,49,50 The findings not only underscore the rich diversity of medicinal plants in the region but also highlight the important role that certain plant families play in traditional healthcare systems.

Local communities tend to favor plants that are easily accessible and perceived as safe, which emphasizes the importance of continued scientific research into their pharmacological properties, as well as the need for conservation efforts to protect these valuable natural resources. The study area covers a range of agroecological zones, particularly the highland (Dega) and midland (Woina Dega) regions, each contributing uniquely to the diversity of medicinal plants. A total of 32 plant species were found exclusively in the highland regions, including species such as Hagenia abyssinica (Bruce) J.F.Gmel., Podocarpus falcatus (Thunb.) Endl., Juniperus procera Hochst. ex Endl., Echinops kebericho Mesfin, and Rosa abyssinica R.Br. ex Lindl. In contrast, 44 species were unique to the midland regions, such as Allium sativum L., Vernonia amygdalina Delile, Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal, Citrus × sinensis (L.) Osbeck, Zingiber officinale Roscoe, Cucurbita pepo L., and Linum usitatissimum L. Additionally, 19 species were common to both zones. This variation is largely influenced by ecological factors like elevation, microclimates, and vegetation types, which all contribute to the distribution of plant species (Fig. 3). The higher plant diversity observed in the midland areas can likely be attributed to the more favorable climate and environmental conditions that support a broader range of plant species.

These areas are also more accessible, facilitating greater interaction between communities. This accessibility promotes the exchange of ethnobotanical knowledge, thereby increasing the diversity of medicinal plants in use. The overlap of 19 species between the highland and midland zones suggests a shared knowledge base, likely sustained through cultural exchanges, local trade, and intergenerational transmission of knowledge. These factors collectively help preserve traditional medicinal practices in the region.

Dynamics of traditional phytomedicine knowledge in Jabitehnan district: A diachronic, geographical, and cultural perspective

In Jabitehnan District, the practice of using medicinal plants is deeply rooted in history, with knowledge traditionally passed down through generations, primarily by elders and spiritual leaders who served as key healers in their communities. These figures were highly respected for their understanding of local plants and their healing properties. However, in recent years, rapid socio-economic changes and modernization have started to alter how this knowledge is valued and transmitted, particularly among younger people. Although the use of medicinal plants such as R. chalepensis, A. sativum, Z. scabra, V. sinaiticum, W. somnifera, J. schimperiana, and L. sativum persists, environmental degradation and shifts in cultural priorities have led to a noticeable decline in both plant availability and the intergenerational transfer of knowledge. Traditionally, plant remedies involved complex mixtures crafted for holistic healing, but modern practices tend to favor simplified preparations, such as using single-species remedies or commercial powders. This transition reflects both the adaptability and the vulnerabilities of local ethnomedical traditions, as external influences reshape health practices and perceptions22,29. The traditional belief that illnesses have spiritual origins is increasingly giving way to biomedical understandings, especially among the youth, leading to a reliance on pharmaceutical treatments and a growing marginalization of indigenous healing knowledge23,24,25,26.

When compared to other parts of Ethiopia, the medicinal plant practices in Jabitehnan display both similarities and distinct local characteristics. For instance, while R. chalepensis is widely recognized across Ethiopia for treating digestive issues, the preparation methods in Jabitehnan such as mixing crushed leaves with butter for topical application or combining them with honey for oral treatment of syphilis differ from the decoction based approaches observed in districts like Quara47. Such differences highlight how local environmental conditions and cultural traditions shape specific medicinal uses. Furthermore, the diversity of medicinal species in Jabitehnan is less extensive than in regions like Southwest Ethiopia, where rich montane forests offer a broader range of healing plants8,22,29,41.

The semi-agricultural setting of West Gojjam encourages reliance on drought-tolerant and readily available species. Ritual practices also vary; while plants like E. kebericho play a significant role in spiritual cleansing ceremonies in northern Ethiopia, in Jabitehnan, smoke from O. europaea is more commonly used in healing rituals. These regional distinctions underscore that even when communities share botanical resources, their cultural uses and symbolic meanings can differ significantly. Culturally, the traditional medicinal practices of Jabitehnan are intricately linked to indigenous worldviews that see health as a balance between physical, spiritual, and social well being. Many plants serve dual purposes: they are not only remedies but also offer protection against malevolent forces. For example, R. chalepensis is valued both for treating headaches and for warding off evil spirits, embodying a holistic approach to health that remains deeply ingrained despite biomedical influences27,28.

Beliefs in phenomena like the “evil eye” (Buda) and “spirit attacks” (Zār) still persist, and healing rituals involving prayers incense, and blessings by elders often accompany the use of herbal remedies28. Gender roles strongly influence the distribution of phytomedicinal knowledge; women are primarily responsible for treatments related to childbirth, children’s illnesses, and household care, while men focus more on animal health and spiritual ailments. This gendered division of knowledge mirrors broader ethnobotanical patterns across Ethiopia. Although modernization, religious shifts, and market commercialization of medicinal plants are altering traditional practices, a strong sense of cultural identity endures. Encouragingly, some younger healers are blending traditional wisdom with scientific knowledge, suggesting a path forward for sustaining and revitalizing ethnobotanical traditions29,42.

Growth forms of medicinal plants

Among the medicinal plant species identified in the study area, shrubs emerged as the dominant life form, making up 38 species (40%). Herbs followed closely behind with 34 species (35.7%), while trees accounted for 21 species (22.1%). Climbers were the least represented, with only 2 species (2.1%) documented (Fig. 4). The predominance of shrubs is consistent with findings from other ethnobotanical studies conducted across various Ethiopian regions40,47,51.

The widespread use of shrubs likely reflects their ecological adaptability and year-round availability. These plants are often more resilient to environmental stresses, including drought and the encroachment of invasive species, making them a reliable source for traditional remedies. Moreover, their accessibility and sustainable harvesting potential contribute to their frequent use in local healing practices.

The variation in plant life form preferences can also be influenced by several factors, including cultural traditions, ecological zones, topography, and the ease with which different plants can be accessed20. Interestingly, while shrubs dominated in the current study, research from other regions, particularly in southwestern Ethiopia, has shown a stronger reliance on herbaceous species for medicinal purposes8,21,22,38,41,46. This discrepancy may stem from the unique environmental conditions in southwestern Ethiopia, which benefits from year-round rainfall and is home to several UNESCO recognized biosphere reserves such as Kaffa, Sheka, Yayu, and Majang. These areas are characterized by dense natural forests that support a high abundance and diversity of herbaceous plants, which in turn shapes local medicinal practices8.

Habitats of medicinal plants

The majority of medicinal plants identified in the study 48 species (50.5%) were gathered from wild environments, while 36 species (37.9%) were sourced from home gardens. An additional 9 species (10%) were found in both wild and cultivated areas. These results reveal a strong dependence on wild vegetation for medicinal plant use within the community. Many informants emphasized that while there have been efforts to cultivate these species, such attempts often fail. The main reasons cited include the specific environmental conditions many of these plants require such as mountainous terrain, shaded areas, or unique soil and microclimates that are difficult to replicate in domestic settings. As a result, these plants tend to grow more successfully in their natural habitats. However, the increasing human population and associated land use changes are putting pressure on wild ecosystems, leading to the shrinking of these habitats. This concern was echoed by several community members who noted visible declines in the availability of certain wild species.

Similar observations have been reported in previous ethnobotanical studies across Ethiopia2,7,20,21,22, as well as in international studies52,53. These findings underscore the urgent need for effective conservation strategies to protect wild medicinal plant species and preserve traditional knowledge for future generations.

Phytomedicine plant parts used and methods of Preparation

In the study area, various parts of medicinal plants were reported to be used for traditional healing, including leaves, roots, fruits, seeds, stems, and bark. Among these, leaves were the most frequently utilized, making up 43% of all remedies, followed by roots (20%) and seeds (12%). Leaves were particularly favored due to their ease of collection, minimal harm to the plant during harvesting, and the perception that they possess strong therapeutic properties. This trend aligns with other ethnobotanical studies conducted in Ethiopia8,21,54,55.

Leaves are not only more accessible but also allow for more sustainable harvesting practices compared to roots or bark. However32, caution that excessive harvesting of leaves could disrupt photosynthesis and reproductive processes, potentially threatening plant populations over time. Roots, the second most used plant part, are often preferred for their high concentration of bioactive compounds56,57,58. Despite their medicinal value, heavy reliance on roots poses a significant risk to plant survival. For instance, in Bita district, southwest Ethiopia, the market demand for the roots of E. kebericho has brought the species close to extinction20. Similarly51, emphasize that roots play a critical role in both nutrient absorption and structural support, making their overharvesting particularly damaging. When it comes to preparation, remedies were most often made from dried plant parts (48%), closely followed by fresh preparations (46%). Only 6% of the informants reported using both fresh and dried forms. This distribution may be influenced by the region’s bimodal rainfall, which affects the availability of fresh materials, particularly between June and November during the wet seasons. The drying of plant materials is believed to help retain their medicinal properties longer and makes them easier to store.

The frequent use of fresh materials, while common, raises sustainability concerns, as it necessitates constant harvesting, placing added pressure on plant populations. Informants shared that for seasonal or rare plants, they typically preserve materials using traditional methods such as wrapping in paper, storing in animal horns, or placing them in bottles kept in cool, dry environments to extend their shelf life and ensure availability year-round. Various techniques were used to prepare the remedies. Physical methods were the most prevalent, including pounding (24%), squeezing (13.4%), and crushing (11.3%). These were followed by liquid-based methods such as boiling (decoction), steeping (infusion), and soaking (maceration) (Table 3). Such techniques are used to either reduce the size of plant parts or extract their active components. For instance, pounding and crushing help release therapeutic compounds, whereas decoctions effectively extract soluble ingredients. Similar preparation techniques have been noted in prior studies22,27,38,41,46,51. Decoctions, in particular, are valued for their ability to maximize medicinal extraction, while concoctions blends of multiple plant remedies are often used for their perceived synergistic effects in treating complex health conditions. These variations in preparation practices reflect a deep-rooted knowledge system that is shaped by cultural traditions, environmental conditions, and the accessibility of plant resources across different communities59.

In the study area, the primary method of administering phytomedicines was oral, with 55% of the cases reported. This was followed by dermal applications (27.5%), and nasal applications (11%). The remaining methods accounted for less than 10% of the total. These findings suggest that local communities predominantly use oral administration, followed by dermal application. The preference for these methods could be due to their ability to produce quick physiological responses, enhancing the effectiveness of treatments against various ailments60,61. Similar trends have been observed in other studies18,54. In addition to oral use, topical treatments, such as creams, ointments, or poultices, provide indigenous communities with more targeted and efficient remedies for skin conditions. As noted by8 dermal applications are favored because they are easier for patients to use and carry a lower risk of toxicity or absorption issues.

Phytomedicine dosage, additives, taboos and diagnostic features

The dosage of herbal medicines varied depending on the type of illness and the practitioner administering the treatment. Other factors, such as the patient’s age and condition, also influenced the prescribed amount. Informants shared that doses were generally estimated using various local measuring tools, such as cans (known as Tanica or Tassa), spoons (Mankiya), tea cups (Yeshay birchiqo), coffee cups (Finjal), water glasses (Birchiqo), and containers made from cattle horns. For certain plant parts, such as roots, stems, and bark, finger lengths (atik) or pinches for powdered materials were used, while numbers were applied for leaves, seeds, fruits, and flowers, depending on the patient’s age, the nature of the illness, and the patient’s overall health. Healers often relied on specific diagnostic features to determine both the diagnosis and the appropriate dosage, considering the type and duration of the ailment. Diagnosis was typically based on patient interviews and visual inspections. Practitioners would ask patients or their families about symptoms and how long they had been present, while also examining physical signs such as changes in the eyes, skin, urine, tongue, and throat. Other symptoms, such as body temperature, swelling, edema, coughing, bleeding, diarrhea, vomiting, parasitic presence, and the condition of sores, were also monitored. Smaller doses were typically given to children or more sensitive individuals. However, this method of estimation could lead to problems, such as overdosing, which could result in severe complications or even death, or underdosing, which might prevent effective treatment. While locals have developed an intuitive understanding of appropriate doses based on the patient’s physical condition, the lack of consistent precision and standardization remains a challenge in traditional medicine.

In the area studied, herbal remedies were used both with and without additives. Most phytomedicines, however, were applied without additional ingredients. Some remedies did include additives, such as yogurt, cheese, sugar, niger, water, milk, teff injera, coffee, honey, meat, barley-made Beso, and “Tella” or “Arekie” (a local beer). These substances are believed to help ease symptoms like abdominal pain, vomiting, and discomfort, as well as improve the effectiveness of the treatment and reduce potential side effects. Similar findings were noted in studies by21,22,47. Although46 suggested that Ethiopian remedies do not produce negative side effects, further research is needed to confirm their safety and effectiveness. Informants in this study emphasized the importance of additives in enhancing the healing power of remedies. Healers also mentioned the use of antidotes to counter any negative effects from certain medicinal preparations, such as J. schimperiana and R. nepalensis, which are used to treat Hepatitis and Amoebiasis. Water was the most common solvent used in the preparation of herbal medicines, consistent with findings from previous studies8,13,21,62. These studies also highlighted the challenge of imprecision and the lack of standardization, which hinders the full recognition of traditional healthcare systems. Likewise22,63, noted that inaccurate dosages remain a significant limitation in traditional remedies, reinforcing the results of this study.

In this study, it was found that individuals infected with rabies are forbidden from crossing rivers while using traditional medicine. Violating this rule is believed to render the medicine ineffective, potentially resulting in death. This belief is consistent with findings from17,20. Additionally, some informants explained that phytomedicines, even when contained, should not be placed on the ground, as it is thought to reduce their potency. Informants also shared the belief that a person who has been bitten by a snake should not sleep until they have fully recovered, as local tradition holds that sleeping could lead to death. Traditional healers in the region typically gather herbal medicines early in the morning, before washing their hands or having breakfast, and they avoid contact with both people and animals during this process. Some believe that unwashed hands in the morning carry special healing powers2. Additionally, healers often isolate themselves during this preparation, as they believe it enhances the effectiveness of the remedies and prevents others from witnessing the process. Furthermore, some healers refrain from engaging in sexual activity during the days set aside for gathering, preparing, and applying herbal remedies, and they advise patients to do the same while undergoing treatment. It was also noted that Wednesdays and Fridays are regarded as the most favorable days for these activities. Any deviation from these practices is thought to render the remedies ineffective. For remedies used to treat spirits and the evil eye, the collection is done in the morning, with the healer often being completely nude. These findings are in line with previous reports by10,20.

Marketability of phytomedicines

Among the phytomedicines examined for their market potential in treating various health conditions, only four species were actively traded for their medicinal properties. These species include E. kebericho, O. europaea, C. anisata, A. abyssinica, and W. somnifera. In local markets, a single root of E. kebericho was typically priced around 50 Ethiopian Birr, while a bundle of leaves from (A) abyssinica and W. somnifera, along with a piece of stem from O. europaea and C. anisata, was sold for 25 Birr50,51,66. Other documented phytomedicines were mostly sold in bulk for non-medicinal purposes, such as culinary uses, spices, and beverages, though they were also used for traditional medicine when required. Notable examples of these species include O. europaea, E. kebericho, Z. officinale, C. annuum, (B) carinata, and L. sativum L.(Fig. 5). This observation aligns with findings from2,21,22,60.

A market survey indicated that while phytomedicines are commonly used to treat various ailments in the local community, they are mostly sold directly by healers to their clients, rather than through open markets. This is because healers typically tailor dosages based on individual patient needs, leading local people to prefer purchasing remedies from healers for their specific health concerns. As a result, medicinal herbs with market value are more often sold for non-medicinal purposes. These findings are consistent with those of55, who suggested that the taboo surrounding herbal medicine may stem from the belief that it is a sacred, spiritual practice that should not be commercialized. Similarly20,51, noted the cultural taboo against selling traditional herbal medicine in marketplaces.

The informants’ agreement on phytomedicines

The analysis of the Informant Consensus Factor (ICF) involved classifying diseases into eight categories (Table 4). These categories include dermatological conditions (e.g., wounds, dandruff, warts, eczema, allergic reactions, goiter, leprosy, measles, herpes, vesicular eruptions, and swelling), digestive and gastrointestinal diseases (such as typhoid, diarrhea, vomiting, liver disorders, stomach discomfort, ulcers, constipation, malaria, ascariasis, amoebiasis, and toothaches), nervous system disorders (like devil, evil eye, stroke, headache, fever, and sexual impotence), respiratory diseases (e.g., common cold, flu, asthma, bronchitis, tonsillitis, and sore throat), cardiovascular diseases (including hypertension, diabetes, and heart ailments), musculoskeletal conditions (e.g., back pain, joint injuries, and hepatitis), infective diseases (such as thorn injections, spider bites, snake bites, and rabies), and miscellaneous conditions (including ear infections, eye diseases, abortion, syphilis, and gonorrhea). This classification was based on several factors, including the nature of the disease, its causes, the affected body parts, and the symptoms displayed by individuals7,22.

In the study area, the popularity of different phytomedicines was assessed based on how frequently informants independently mentioned each medicine. Among the disease categories, dermatological ailments had the highest Informant Consensus Factor (ICF), followed by gastrointestinal conditions, suggesting that informants were more confident in using specific phytomedicines for treating these issues. While some informants showed low ICF values, indicating a diversity of opinions, those with higher ICF values largely agreed on the use of certain plants for skin conditions. As20 highlighted, a high ICF indicates strong agreement on the selection of plant species, while a low ICF suggests a lack of consensus.

Common skin problems in the area, such as wounds, measles, vesicular eruptions, warts, dandruff, and eczema, had a significant impact on daily life, as did gastrointestinal and parasitic infections. The discomfort and limitations these conditions cause may explain their prominent impact on daily activities. These findings suggest that the identified plant species may have potential for developing treatments for wound healing and parasitic infections. This is consistent with previous research2,46,55,64.

Healing potential of phytomedicines

The calculated fidelity level (FL) values showed that K. petitiana (used for wound healing) and P. dodecandra (for treating rabies) had the highest FL values for their respective ailments (Table 5). This suggests that these plants might possess bioactive compounds that could support and enhance the wound healing process. In contrast, C. macrostachyus achieved the highest FL value for ringworm treatment, while R. chalepensis scored high for addressing the common cold.

A study by20 found that C. papaya was highly effective in treating malaria, and38 reported that O. lamiifolium had the highest FL value (98%) in their study conducted in Asagirt District, Northeastern Ethiopia. Similarly, in research conducted by55 in Habru District, North Wollo Zone, Ethiopia, S. somalense (91.3% FL), O. lamiifolium (88.9% FL), and V. sinaiticum (85.7% FL) showed significant healing potential. These results suggest that the phytomedicines with the highest FL values may have strong therapeutic potential in the study area. Further phytochemical research should focus on exploring the bioactive compounds in these plants to understand their healing capabilities more thoroughly.

Preference ranking of phytomedicines

In the study area, six phytomedicines were identified as effective for treating wound infections. Ten key informants were selected to evaluate and rank these plants based on their healing potential. The informants assigned higher ranks to plants with greater healing properties and lower ranks to those with lesser effectiveness. The scores provided by the informants were then summed and organized in order of efficacy. K. petitiana received the highest score, securing the top rank, followed by D. angustifolia and S. anguivi, indicating that these species are considered the most effective and preferred for treating wound infections.

The other plants (A) africanus, V. sinaiticum, and E. brucei were ranked fourth to sixth, respectively, based on their treatment potential for this condition (Table 6). In contrast, a study by22 in central Ethiopia found that C. macrostachyus was the most preferred among seven different phytomedicines used to treat wounds. Additionally, a study conducted in Guraferda district by8 reported that (B) pilosa emerged as the most preferred plant species for wound management, due to its wide availability in various regions and ease of preparation for use.

Direct matrix ranking of multipurpose phytomedicines

The results from the direct matrix ranking (DMR) conducted in the study area revealed that many phytomedicinal species are at risk due to their various uses beyond medicinal purposes. These plants are utilized for food, firewood, charcoal, construction materials, farming, furniture, and forage. In this study, ten key informants were involved in assessing five multipurpose phytomedicinal species that are endangered due to multiple utilitarian demands.

The plants were ranked across eight categories of use, from highly threatened to least threatened. The ranking system was as follows: 5 = best, 4 = very good, 3 = good, 2 = less used, 1 = least used, and 0 = not used. Based on the rankings, H. abyssinica, C. africana, and P. falcatus were identified as the top three most threatened indigenous phytomedicinal species. These were followed by J. procera and S. longepedunculata, which were considered the least threatened by activities such as firewood collection, charcoal production, and the use of these plants in construction and furniture making (Table 7).

Consistent with these findings, reports by20,41,47,65 highlighted that C. africana is among the most threatened phytomedicinal species. Additionally, a study in Guraferda district indicated that S. longepedunculata faces significant threats29. These results suggest that the decline of multipurpose phytomedicines leads to the loss of related indigenous knowledge, which could contribute to an increase in health problems in the region. Therefore, it is crucial to manage these plants sustainably and prioritize their conservation both within the study area and across the country.

Traditional knowledge of phytomedicines among different informant groups

Variation in phytomedicine knowledge among informants types

A t-test conducted using R software was employed to assess the differences in phytomedicine knowledge between key informants and general informants. The results revealed a statistically significant difference in knowledge between the two groups (t = 9.4, P < 0.05). Key informants demonstrated a significantly higher average knowledge score (M = 5.5, SD = 1.4) compared to general informants (M = 2.4, SD = 1.3) (Table 8). These findings align with previous studies by20,21,22,65 which also highlighted a knowledge gap between these groups. This suggests that key informants are more familiar with traditional knowledge, likely due to their deeper cultural engagement and extensive experience with plant resources.

The pronounced knowledge gap between key and general informants carries significant implications. It emphasizes the need to acknowledge the expertise of key informants, who play a crucial role in preserving traditional knowledge and practices related to phytomedicines. Additionally, they contribute to promoting sustainable harvesting and cultivation methods. Given the significant disparity in knowledge, it is essential to implement targeted educational programs to improve the understanding of phytomedicines among general informants. By enhancing the broader community’s knowledge and skills, we can encourage the sustainable use of phytomedicines and cultivate a greater appreciation for traditional healing practices.

Gender based variations in phytomedicine knowledge

A t-test was conducted using R software to examine the differences in phytomedicine knowledge between male and female informants. The results revealed a significant gender disparity in phytomedicine knowledge scores (t = 6.7, P < 0.05), as shown in Table 8. Specifically, male informants had a higher average knowledge score (M = 4.8, SD = 1.6) compared to female informants (M = 2.4, SD = 1.5) (Fig. 6). This finding is consistent with previous studies by20,22,63. However, research by66 suggests that women may possess more knowledge about medicinal plants than men, while other studies38,67 have indicated similar knowledge levels between genders.

A study in Mizoram, India, found no significant difference in knowledge between male and female informants (p > 0.05)68. In many traditional societies, including those in Jabitehnan District, the distribution of ethnobotanical knowledge often reflects gender roles. Men and women tend to have distinct knowledge sets due to differences in labor division, cultural norms, and access to various environments. Male informants, who are more likely to be involved in farming, hunting, herding, and other outdoor activities, typically have knowledge of plants used to treat wounds, respiratory issues, or livestock diseases. In contrast, female informants tend to be more familiar with plants used for childcare, reproductive health, and common household ailments such as colds or digestive issues. This gendered division of knowledge enriches the community’s overall understanding of phytomedicines, underscoring the value of incorporating both male and female perspectives in ethnobotanical studies. Research in other regions of Ethiopia, such as by13,21,61, has similarly shown that including diverse gender groups provides a more comprehensive understanding of phytomedicine use.

The findings also indicated that men were more actively involved and knowledgeable in collecting and using traditional medicines than women. This can be attributed to the fact that men are often guided by their fathers or elders and participate in activities such as agriculture, animal husbandry, wood collection, and hunting, which expose them to plants used in traditional medicine. On the other hand, many women in the study area primarily engage in domestic tasks, which are less directly related to herbal medicine practices, resulting in fewer female healers. This male dominance in phytomedicine practices has been reported by other researchers, including2,8,22,46. These gender differences may be influenced by historical, social, or cultural factors. One possible explanation is that men often have more opportunities to interact with natural environments, such as fields and forests, which are rich in medicinal plants. Additionally, some studies20,21,22suggest that medical knowledge is traditionally passed down to sons rather than daughters. However, this assumption is not universally true, as women have historically participated in hunting and gathering activities and have made significant contributions to collecting plant species. Therefore, it is important to challenge the stereotype that only men can contribute to plant collection and recognize the roles of both genders in these practices. To address these disparities, further research is needed to explore the factors contributing to this inequality and inform the development of programs and policies that empower female informants and promote gender-inclusive strategies in resource management and traditional medicine.

Educational influence on traditional knowledge

A t-test was conducted using R software to analyze the differences in phytomedicine knowledge among informants based on their educational backgrounds. The results revealed a statistically significant difference in knowledge between the two groups (t = 5.7, P < 0.05). Specifically, illiterate informants had a significantly higher mean knowledge score (M = 4.1, SD = 1.9) compared to literate informants (M = 2.1, SD = 1.3) (Fig. 7). This suggests that the variation in phytomedicine knowledge across different educational levels may stem from the impact of formal education on the acquisition and transmission of traditional medicinal knowledge. These findings align with previous studies conducted nationwide2,20,21.

In Jabitehnan District, individuals with no formal education or only primary schooling often demonstrate a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of phytomedicine than those with higher education levels. This difference can likely be attributed to greater exposure to modern healthcare information among more educated individuals, which may reduce their reliance on traditional practices. Moreover, formal education can unintentionally lead to the erosion of traditional knowledge, particularly when indigenous knowledge systems are not incorporated into the curriculum. However, some educated individuals, particularly those with an interest in local culture or environmental studies, have expressed a strong desire to preserve traditional practices. This highlights the potential benefits of including ethnobotany in local educational curricula as a way to safeguard traditional knowledge46,65. Fewer individuals with advanced degrees tend to possess in-depth knowledge of phytomedicines, often due to limited exposure to traditional practices in formal education, especially in higher education institutions.

Cultural factors also influence the awareness of phytomedicines across different educational levels, as knowledge is often passed down within specific communities. Those with higher education may become disconnected from traditional medical practices due to the focus on Western medicine in their studies. These findings have significant implications for public health and educational policies, underscoring the need for targeted interventions to bridge the knowledge gap between individuals with different educational backgrounds. To foster a more holistic approach to healthcare, it is essential to integrate traditional medical knowledge into both formal education and healthcare systems.

Age as determinant of ethnobotanical knowledge

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) conducted in R revealed that age groups—young, middle-aged, and elderly significantly influenced phytomedicine knowledge scores (p < 0.05) (Table 9). Further examination through Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests showed that the elderly group had significantly higher mean scores (M = 4.3, SD = 2.4, p < 0.05) compared to both the middle-aged group (M = 2.9, SD = 1.5, p < 0.05) and the young group (M = 1.2, SD = 1.0, p < 0.05) (Fig. 8). Age is a crucial factor influencing the depth and scope of traditional medicinal knowledge. Elderly informants, particularly those over 51 years old, possess a much more comprehensive understanding of phytomedicines, including their identification, preparation, and traditional uses. This knowledge is attributed to years of direct exposure to nature, hands-on practice, and cultural immersion.

In contrast, younger individuals often have limited knowledge, mainly due to urban migration, changes in lifestyle, and increased reliance on modern healthcare systems. The generational gap in knowledge transfer is further widened by the lack of interest or time among the youth to engage in traditional apprenticeships. Similar patterns have been observed in ethnobotanical studies across Ethiopia, stressing the urgency of documenting elders’ knowledge before it is lost20,21,30.

Research from Ethiopia and other parts of the world69 supports the idea that older individuals are more likely to use phytomedicines compared to younger generations20,22,62. This difference is likely due to the elders’ extensive experience with local medicinal plants and their use in treating various ailments through traditional methods. Meanwhile, younger generations are increasingly distanced from these practices, influenced by modernization and globalization. Many young people are drawn to contemporary education, which leads to a decline in interest in traditional ethnomedicinal knowledge. This growing disconnection from local knowledge is a serious concern.

The positive correlation between age and phytomedicine knowledge, with a correlation coefficient of 0.79 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 9), suggests that as individuals age, their understanding of phytomedicines increases. These findings align with previous research20,22,30,70. Therefore, these results highlight the importance of prioritizing the knowledge of older generations and supporting their role in preserving and transmitting ethnobotanical knowledge.

Novel ethnobotanical findings in Jabitehnan district

The ethnobotanical research carried out in Jabitehnan District, West Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia, revealed several important new insights into how local communities traditionally use medicinal plants. A particularly noteworthy discovery is the medicinal application of U. simensis. Although commonly valued for its nutritional benefits, the plant is also used to treat conditions like Ascariasis and digestive ailments. Local healers prepare the plant in various ways, such as chopping its leaves and shoots, demonstrating its flexibility in both food and medicine. This highlights how traditional knowledge systems seamlessly integrate nutrition and healing, reinforcing the idea that food plants can serve as essential elements of healthcare. Moreover, U. simensis plays a significant role in seasonal celebrations and communal events, further underscoring its importance in promoting both health and social cohesion. Another remarkable finding is the widespread use of R. abyssinica, known locally as “Qega” in Amharic and “Mersanie” in the ancient Ge’ez language. Beyond its nutritional qualities, this plant holds considerable medicinal value. Traditional practitioners use its leaves, seeds, and stems to address various health problems such as malnutrition, inflammation, and bronchial spasms.

Additionally, the stems are culturally significant; they are burned to impart a pleasant scent to traditional clay containers (Ensar or Madiga) used for storing water and milk. This dual role of R. abyssinica both as a health remedy and a cultural artifact reflects a holistic approach to wellbeing, deeply embedded in local traditions and daily life. A further noteworthy discovery is the traditional use of V. sinaiticum known primarily for its role in preparing “Dibin,” a local yeast used in baking Enjera, it is also employed to treat digestive issues and various skin conditions. This multifunctional use once again demonstrates the close relationship between diet and medicine in local knowledge systems.

Documenting these newly reported uses of plants in Jabitehnan is critical, as it preserves valuable ethnobotanical knowledge that risks being lost. Moreover, these findings point to the need for detailed phytochemical studies to scientifically validate the medicinal properties attributed to these plants. Such research could enrich modern medical understanding while supporting the continuity of traditional healthcare practices that have been sustained over generations.

Threats to phytomedicines in Jabitehnan district

The findings of this study indicate that various factors are contributing to the decline of phytomedicines in the Jabitehnan District. The most significant threats include agriculture, firewood collection, construction, charcoal production, house and fence building, overgrazing, and urbanization. These factors were ranked according to their contribution to the loss of phytomedicines in the environment. Agriculture, construction, and firewood collection were identified as the top three threats, ranking first, second, and third, respectively, followed by house and fence building, charcoal production, and overgrazing, which ranked fourth to sixth (Table 10).

The prevalence of agriculture, construction, and firewood collection as primary threats can be attributed to the daily activities of the local communities, which heavily depend on these practices. This finding is consistent with reports by20,21,22. Agriculture in the study area has been expanding rapidly due to the growing population. Deforestation is increasingly common, with both individual farmers and farming groups engaging in land clearing, often for investment purposes. Women and youth frequently collect firewood for sale, and they not only gather shrubs and branches but also cut down large trees for their stems, contributing significantly to the loss of phytomedicines in the area. Urbanization has also been on the rise, leading to increased road and house construction, which further reduces the availability of phytomedicines. Urban areas have a high demand for charcoal, and as a result, phytomedicines close to urban centers are being deforested for charcoal production, making it one of the most significant threats. According to local informants, species such as H. abyssinica, C. africana, P. falcatus, J. procera, S. longepedunculata, E. globulus, and O. europaea are most affected by these activities.

Overgrazing, driven by the community’s dependence on animal husbandry, also poses a significant threat to phytomedicines in the region. Similar findings have been reported by2,8,21,22,71,72, who identified agriculture, firewood collection, construction, and charcoal production as the primary drivers of phytomedicine loss.

Traditionally, healers in Jabitehnan District have relied on oral transmission within families to share their knowledge of herbal remedies and diagnostic methods. Healers, often the custodians of local knowledge, have passed this information down to their family members, particularly their elder sons. However, the study reveals that indigenous knowledge is increasingly at risk of disappearing due to a combination of factors. These include the younger generation’s decreasing interest in traditional practices, as well as the widespread influence of globalization, industrialization, and modernization. Unless the local community takes active steps to preserve and apply their indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants (MPs), this invaluable resource may vanish from the area.

The transfer of traditional plant knowledge has been primarily oral, and the death of many elder healers without passing on their knowledge has resulted in a rapid decline in authentic traditional practices. This decline can be attributed to several factors: (i) younger generations’ preference for modern education over traditional knowledge, (ii) cultural changes due to urbanization, and (iii) some traditional healers not having heirs to continue the knowledge. Previous studies have highlighted the loss of ethnomedicinal knowledge as a direct result of acculturation, declining interest in traditional practices, and the diminishing availability of phytomedicines20,22,55,73.

Management and conservation of phytomedicines in Jabitehnan district

According to the responses from informants in the study area, traditional practitioners manage and conserve plants in their locality to meet various needs, including food, construction materials, firewood, fodder, commercial purposes, cultural and spiritual values, and medicinal use. Indigenous people in the area possess knowledge that helps them understand plant habitats, distribution, harvesting techniques, optimal harvest times, and the conservation status of plants in their region. Traditional practitioners play a more active role in the conservation and management of phytomedicines compared to other members of the community.

Most often, they conserve these plants by cultivating them in their home gardens or in spiritual areas, particularly within the grounds of Orthodox tewahedo churches. This suggests that phytomedicines found around home gardens and spiritual sites are better conserved and managed than those in the wild. The spiritual, ritual, and material values attached to these plants by the local people contribute significantly to their conservation. Field observations in areas such as Woynma Woqima and Miricha Borabora Kebeles indicated that spiritual and ritual areas were better protected and managed than other areas, as cutting or harvesting plants in these zones is not allowed.

In addition to spiritual areas, other protected zones within the study area also demonstrated better conservation and management practices than other parts of the land. Informants mentioned that certain areas are culturally protected by the community. In Jabitehnan District, the conservation efforts promoted by Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Dr. Abiy Ahmed, such as the Green Legacy initiative, which involves seedling planting during the rainy season and soil tracing in barren land during the winter season, play a crucial role in soil, water, and medicinal plant conservation. This initiative has now expanded throughout the Amhara region and beyond. Activities related to traditional beliefs and reverence, including conflict resolution and other social events known locally as “Mahiber,” are conducted in these protected areas. As a result, individuals or groups cannot harvest or cut plants from these areas unless permitted by cultural leaders.