Abstract

This study evaluated Brevibacillus laterosporus (PBC01) on growth performance, immunity and intestinal health of male Lohmann Brown laying chickens. A total of 144 7-day-old chickens were randomly assigned to four dietary treatments: a basal diet supplemented with 0%, 0.10%, 0.25%, or 0.50% (w/w) B. laterosporus PBC01 powder (1.0 × 109 cfu/g), designated as negative control group (NC), low-dose group (BL), medium-dose group (BM), and high-dose group (BH), respectively. Each group was fed the corresponding experimental diet for 56 days. Results showed that supplementally feeding with 0.25% PBC01 (BM) could enhance the chicken’s antioxidant capacity and improve body weight gain and and optimized the feed conversion ratio throughout the experimental period. PBC01 also promoted the relative weight of immune organs, enhanced lymphocyte conversion in peripheral blood and reduced the mRNA expression of IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, TNF-α in spleen. In addition, dietary with PBC01 enhanced cellulase and protease activity in the jejunum; It can lengthen the villi height, reduce the depth of the crypts, improve the intestinal morphology, enhance the intestinal viability, and also enhance the tight links of cells. Moreover, PBC01 also showed beneficial effects in sustaining chicken’s microbiota homeostasis by increasing the number of beneficial bacteria and reducing the pathogenic bacteria. In conclusion, this study showed that 0.25–0.50% supplementation of PBC01effectively improved antioxidant status, immune response, intestinal environment, and growth performance in male laying chickens, demonstrating its potential as a functional probiotic strain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chicken meat is the most widely consumed meat globally, and China is a major producer of broilers. Male layer chicken defined as the male chicks retained by egg hatcheries upon hatching1. While most male layer are culled shortly after birth, opposition to this practice is growing in western countries on humanitarian grounds. In recent years,, the dual-purpose poultry (DP) has been widely discussed2. Under the DP system, females are kept to produce eggs and males to produce meat. Compared with traditional roosters, male layer chicken has the advantages of low price, low mortality rate, etc.3 Moreover,, male layer chicken do not have poorer chicken meat quality than broilers4. Consequently, the rearing of male layer chickens has garnered significant interest and holds substantial potential for market development. For decades, antibiotics have served as effective agents for both prevention and treatment in human medicine and livestock production.. However, the long-term misuse of antibiotics had led to a growing problem of drug resistance in human and animal organisms, with an increasing number of drug-resistant bacteria5. In response, China banned the production of commercial feeds containing antibiotic growth promoters starting July 1, 2020. This regulatory shift underscores the urgent need to develop greener, safer and more efficient feed additives need to be produced. mong the currently available alternatives, probiotic feed additives, herbal supplements, and antimicrobial peptides represent some of the most promising options.

Probiotics are microorganisms that s that confer a health benefit on the host when administered in adequate amounts6. Various probiotics have been used in aquaculture7, poultry farming8, fattening of pigs9, and feeding of ruminant10. Among them, Bacillus probiotics have advantages of a broad antimicrobial spectrum11, applicable to various preparation techniques12 and high safety profile13, etc. These probiotics help enhance the local adaptative immune response, reduce the oxidative stress, adjust of the intestinal flora. Such mechanisms contribute to the maintenance of animal health and support growth and development14,15.

Brevibacilluslaterosporusisa number of Bacillus probiotics, produces a diverse array of metabolites, including antimicrobial peptides16, bioactive enzyme17, immunosuppressant18, polyketone metabolites19. Thus, B. laterosporus plays an important role in pollution degradation20, pest control21, cash crop22, livestock and poultry breeding23, aquaculture24, honey industry25 and other practical production areas. However, few studies have been conducted on its use as a feed additive in animals. Previous laboratory studies have shown that it has a wide range of probiotic properties and good safety26. In this experiment, we evaluate the effects of PBC01 on growth performance, antioxidant capacity, immunological capability, intestinal tight junction proteins, and intestinal flora of male layer. The findings aim to provide a scientific basis for the future development and application of PBC01 as a feed additive.

Materials and methods

Feed additive of PBC01

The powder-based PBC01 preparation utilized in this study was supplied by the Animal Microecology Institute of Sichuan Agricultural University. The detailed preparation methods followed the protocol outlined in reference27, with the spore concentration adjusted to 1.0 × 109 CFU/g.

Chickens and husbandry

A total of 144 healthy 1-day-old Lohmann Brown Lite male layer chickens, were acquired from Long Song Poultry Hatchery (Sichuan, China). 34 ℃ during first week and decrease every week by 3 degrees till reach to ambient temperature 23–26℃. Throughout the experimental period, chickens were provided 24 h of light and ad libitum access to water.

Experimental design and diets

All chickens received a standard starter diet from days 1 to 7. On day 7, 144 chickens were individually weighed on an empty stomach and allocated to four treatments. Each treatment was comprised of 3 replicates with 12 chickens in each. Dietary treatments of this experiment were corn-soybean meal basal diet supplemented with 0%, 0.10%, 0.25%, and 0.50% PBC01, regarded as negative control group (NC, 0%), low-dose group (BL, 0.10%), medium-dose group (BM, 0.25%), and high-dose group (BH, 0.50%), respectively. All the nutrients met or exceeded the nutrient requirements as recommended by National Research Council (1994)28 as shown in Table 1 refer to previous research in our lab29. Experimental diets were fed for 56 days, divided into starter (days 7–35) and finisher (days 35–63) two phases; meanwhile, the chicks of four groups were gotten the Newcastle Disease and Infectious Bronchitis Vaccine, Live (VG/GA + H120 Strain) (Guangxi Liyuan Biological Co., Ltd., China) by eye drip on day 7 and water drinking on day 21(Drink freely and consume within 1 to 2 h). The experimental grouping is shown in Table 2.

Animal ethics statement

All experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Production Research Ethics Committee of Sichuan Agricultural University (SAU) (Ethics Number: SAU-20220461). All experiments were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the China Law of Animal Protection. Additionally, the study adhered to the ARRIVE guidelines. The primary method of euthanasia employed was CO₂ inhalation. Animals were placed in a chamber filled with CO₂ at a controlled rate of 80% of the chamber volume per minute to ensure a gradual and smooth transition to unconsciousness. Following euthanasia, all animal tissues were handled according to with institutional biosafety protocols and disposed of in compliance with local regulatory requirements.

Performance parameters

All chickens were individually weighed after fasting and allocated to four treatment groups on days 7, 35, and 63. Additionally, feed consumption was recorded daily for each group. Finally, the body weight gain (BW), feed intake (FI), average daily gain (ADG), average daily feed intake (ADFI), and feed conversion ratio (FCR, defined as the ratio of feed intake in grams to weight gain in grams) were calculated.

Sample collection

Blood samples were collected from the wing veins of six male layers per group on days 35 and 63 for serum an alysis and lymphocyte extraction. Subsequently, the heart, liver, thymus, spleen, and bursa of Fabricius were weighed and collected. The contents of the jejunum, ileum, and cecum were also collected, and two samples were taken from the jejunum and ileum for morphometric measurements and assessment of mRNA gene expression of tight junction proteins. The samples from the jejunum and ileum intended for histological examination were washed in saline and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, while the remaining samples were stored at −80 °C.

Determination of antioxidant capability

The activities of glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD), dicarboxylic aldehyde (MDA), and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) were measured in serum and liver homogenates using the corresponding diagnostic kits provided by Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute in Nanjing, China.

Determination of immunological indicators

Determination of immune organ index

The spleen, bursa of Fabricius and thymus on both sides will be removed, carefully stripped of fat and connective tissue, weighed and calculated the immune organ index.

Peripheral blood lymphocyte conversion rate measurement

The MTT method was used for the determination referred to Nikbakht30. The stimulation index (SI) was used to determine the lymphocyte proliferation function.

Expression of cytokine-genes and tight junction protein-genes

Total RNA of spleen, jejunum and ileum were extracted by using Animal Total Isolation Kit (Foregene Co., Ltd, Chengdu, China). Then, using 2 × RT OR-EasyTM Mix (Foregene Co., Ltd, Chengdu, China) reverse transcribed RNA into cDNA, cDNA was diluted to an appropriate concentration. The abundance of tight junction proteins and cytokine related mRNA were determined by relative quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using StepOnePlus™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and 2 × SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Servicebio Biotech Co., Ltd, Wuhan, China). Primer details are shown in Table 3. All the samples were analyzed in a total volume of 10 μl, and negative controls were included to check for the nonspecific amplification of primers. The PCR conditions were as follows: 1 cycle at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C (15 s) and optimum temperature (30 s). GAPDH and β-actin was used as reference gene to normalize the relative mRNA expression levels of target genes with values presented as 2−ΔΔCT.

The digestive enzyme activity of jejunum and ileum

Weighed about 0.2 g of jejunum and ileum contents and mixed 1:9 (w/v) with saline, homogenized for 3 min under the condition of ice bath, centrifuged at 1500 g for 10 min. Then, took appropriate amount of supernatant, measured its cellulase, amylase, protease activity, according to Folin-Ciocalteu method, DNS (3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid) method, and iodine colorimetry.

The morphology of jejunum and ileum

Prepared tissue sections by ServiceBio Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China. The target areas were imaged using Eclipse Ci-L photographic microscope (Nikon, Japan)0.15 fields in each intestinal sample were randomly selected to measure the villus height (VH) and crypt depth (CD), and the ratio (VH/CD) was calculated. Measurements of these indexes were made using an image processing and analysis system Image-Pro Plus version 6.0 (Rockville, Maryland, USA).

Quantitative analysis of ileum and cecum microbiota

Total DNA was extracted from about 200 mg ileum and cecum contents using the Stool Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Beijing Solarbio Science &Techology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China), and stored at −80 °C. Absolute qPCR was performed to calculate the populations of the several microbial species, the primers, and standard curves for different bacterial 16S rRNA are shown in Table 4. The PCR volume, cycling conditions, and analysis were the same as above. The CT of samples was used to calculate the copy numbers through the standard curves.

Statistical analysis

For multiple group comparisons, one-way ANOVA followed by a Friedman test was applied IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA) and expressed by means ± standard deviations (SD). Experimental data visualization was performed using Origin 2021b (OriginLab, Northampton, Massachusetts, USA). Significant difference analysis ABC letter notation: First, all the averages are arranged in descending order, and then the largest average is marked with the letter a; and compare the average with the following averages, and mark the letter A if there is no significant difference, until a certain average is significantly different from it, and mark the letter B; Then take the average number marked with b as the standard, and compare it with the average number above that is larger than it, and all those that are not significant are also marked with the letter b; Then take the maximum average marked with b as the standard, and compare with the following unmarked averages, and continue to mark the letter b if it is not significant, until it encounters a mean marked with a significant difference from it marked c. a, b, c Different superscript small letters within a row indicated a significant difference (p < 0.05). A, B, C Different superscript uppercase letters within a row indicated a highly significant difference (p < 0.01).

Results

Growth performance parameters

All groups of male layer chickens exhibited good spirits, and there were no mortalities during the 63 days of rearing. The data for each group are presented in Table 5. There were no significant differences in BW among the chickens at 7 d and 35 d. However, at 63 d, the BW of the chickens in the BM and BH groups was significantly higher than that of the NC group, with the BM group’s BW being 7.84% greater than that of the NC group. Similarly, the ADG of the chickens in each group did not differ significantly during the early period (7–35 d). In contrast, during the later period (35–63 d), the ADG of the BM and BH groups was significantly higher than that of the NC group (p < 0.05). We observed no differences in ADFI among the groups throughout the experiment, but the FCR in BM group was significantly lower than that in the NC group, so we can infer that supplementary feeding of PBC01 may enhance the growth performance of chickens by improving feed conversion efficiency.

Data were shown as mean ± SD; Treatments include negative control group (NC), low-dose group (BL), medium-dose group (BM), and high-dose group (BH) fed with basal diet supplemented with 0%, 0.10%, 0.25%, or 0.50% PBC01 preparation, respectively. Significant difference analysis ABC letter notation: a, b, c Different superscript small letters within a row indicated a significant difference (p < 0.05). A, B, C Different superscript uppercase letters within a row indicated a highly significant difference (p < 0.01). The difference analysis of the NC group was based on its own comparison; The other groups of BL, BM, and BH were compared with the NC group.

Antioxidant status of serum and liver

The antioxidant status of serum and liver in male layer chickens is illustrated in Fig. 1. Our findings indicate that the total antioxidant capacity T-AOC in the BLand BH groups was significantly higher than that in the NC group within the liver. Furthermore, the total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD) activity in the BM and BH groups showed a highly significant difference compared to the NC group. GSH-Px activity in serum of experience groups were highly significantly increased than that of NC group, and in the liver, BL group was significantly higher than NC group. Moreover, the MDA content in serum and liver of NC group was the highest compared to experimental groups, which has highly significant difference from the BL and BM groups. These results suggest that supplementary feeding of PBC01 could improve the antioxidant capacity of male layer chickens.

Antioxidant status of serum and liver in male layer chickens on day 63. (a) T-AOC. (b) T-SOD. (c) GSH-Px. (d) MDA. Determination of immune organ index and peripheral T-lymphocyte conversion rate. a, b, c Different superscript small letters within a row indicated a significant difference (p < 0.05). A, B, C Different superscript uppercase letters within a row indicated a highly significant difference (p < 0.01).

The effects of PBC01 supplementation in the diet on the immune organ index of male layer chickens are shown in Table 6. Compared to the NC group, there was no significant difference in the organ index of the spleen at 63 d. The organ index of the thymus was significantly higher in the BH group at 63 d; the organ index of the bursa of Fabricius increased in BL, BM, and BH group at 63 d, with a significant increase in BL group, compared to the NC group.

Furthermore, the conversion rate of peripheral blood lymphocytes in the experimental groups were significantly increased at 35 d and 63 d (p < 0.05), compared to the NC group. It can be seen that supplementary feeding of PBC01 has the ability to promote peripheral blood lymphocyte conversion in male layer chickens.

Detection of mRNA expression levels of cytokines in the spleen

The expression levels of cytokines in the spleen of male layer chickens are shown in Fig. 2. The relative expression of IL-2, IL-4, IL-6 and TNF-α in the BM and BH groups was significantly lower than that in the NC group (p < 0.05). In contrast, the relative expression of IL-10 and IFN-γ in the BM and BH groups was not significantly different from that in the NC group, and the relative expression of IFN-γ in the BL group was significantly lower than that in the NC group. It can be observed that supplementary feeding of PBC01 could reduce the expression of expression levels of cytokines to a certain extent.

Relative expression of cytokine genes in spleen of male layer chickens on day 63. (a), (b), (c) Different superscript small letters within a row indicated a significant difference (p < 0.05). A, B, C Different superscript uppercase letters within a row indicated a highly significant difference (p < 0.01), three groups (n = 6 per group) on day 63.

Digestive enzyme activity in small intestine

The results of digestive enzyme activities in the small intestinal contents of male layer chickens are shown in the Fig. 3. The protease activity of BM group in jejunum significantly higher than that of the NC group; the cellulase activity in both jejunum and ileum of the BL, BM, BH group was significantly higher than that of NC group; the amylase activity of each group was no difference. This indicates that supplementary feeding of PBC01 can improve the digestive enzyme activity of male layer chickens, especially the cellulase activity.

Digestive enzyme activity in intestine of chickens on day 63. (a) Protease activity, (b) Cellulase activity, (c) Amylase activity. a, b, c Different superscript small letters within a row indicated a significant difference (p < 0.05). A, B, C Different superscript uppercase letters within a row indicated a highly significant difference (p < 0.01), three groups (n = 6 per group) on day 63.

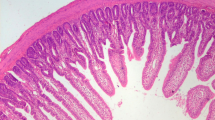

The Morphology of Jejunum and Ileum

The effects of PBC01 on the histomorphology of jejunum and ileum in male layer chickens are shown in Fig. 4. The analysis showed that the jejunum villus height (VH)of BM and BH groups were significantly higher than NC group; the ileum crypt depth (CD) of BL group was significantly lower than NC group. As a result, the VH/CD value of NC group was the lowest, and it was significantly lower than that of BM, BH groups in jejunum and significantly lower than BH group in ileum. This indicated that PBC01 could increase VH and decrease CD of intestinal in male layer chickens.

Supplemental feeding of PBC01 on intestinal morphology of male layer chickens on day 63. (a) Intestinal tissue observations, (b) Analysis of intestinal tissue structure of egg rooster. VH (µm): Villous Height; CD (µm): Crypt Depth VH/CD: Villous Height to Crypt Depth Ratio. a, b, c Different superscript small letters within a row indicated a significant difference (p < 0.05). A, B, C Different superscript uppercase letters within a row indicated a highly significant difference (p < 0.01), 3 groups (n = 6 per group) on day 63.

Detection of tight junction protein-related genes in the jejunum and ileum

As shown in the Fig. 5, in the jejunum, the mRNA expression of tight junction protein-related genes in NC group was the lowest. In NC group, the mRNA expression of Claudin-1&ZO-2 was significantly lower than BL, BM, BH groups, the mRNA expression of Claudin-3 was significantly lower than BH group, the mRNA expression of ZO-1 was significantly lower than BL group, the mRNA expression of Occludin was significantly lower than BL, BH groups. In the ileum, the mRNA expression Claudin-1, Claudin-3, ZO-1, ZO-2 and Occludin of BM & BH were significantly higher than those in the NC group.

Relative gene expression of tight junction protein in jejunum and ileum of male layer chickens on day 63. (A) Relative expression level of Jejunum gene. (B) Relative expression level ofIleum gene. a, b, c Different superscript small letters within a row indicated a significant difference (p < 0.05). A, B, C Different superscript uppercase letters within a row indicated a highly significant difference (p < 0.01), 3 groups (n = 6 per group) on day 63.

Microbial populations of ileum and cecum digesta

The abundance of various bacterial populations in ileum and cecum of male layer chickens is shown in Fig. 6. In the ileum, the abundance of total bacteria, Firmicutes, Enterobacteriaceae, Enterococcus spp., Lactobacillus spp., and Clostridium cluster IV in the BL, BM, and BH groups did not differ from that of the NC group; the abundance of Bacteroidetes and Clostridium cluster XIVa in the BL, BM, and BH groups was significantly higher than that of the NC group; the abundance of Bifidobacteriumspp. in the BH group was significantly higher than that of the NC group.

Effects of PBC01 on ileum and cecal microbiota in male layer chickens on day 63. (a) Structure of the ileal flora, (b) Structure of the cecum flora. a, b, c Different superscript small letters within a row indicated a significant difference (p < 0.05). A, B, C Different superscript uppercase letters within a row indicated a highly significant difference (p < 0.01). three groups (n = 6 per group) on day 63.

In the cecum, the abundance of total bacteria, Firmicutes, Enterobacteriaceae, Lactobacillus spp. and Clostridium species group XIVa in the contents of BL, BM, and BH groups were not different from those of the NC group; the abundance of Clostridium cluster IV in the cecum of BL, BM, and BH groups was highly significantly higher than that of the NC group. The abundance of Bacteroidetes was significantly higher in the BM group than in the NC group; the abundance of Bifidobacterium spp. was significantly higher in the BH group than in the NC group; and the abundance of Enterococcus spp. was highly significant in the NC group than in the BL group. It is speculated that the addition of PBC01 can promote the improvement of digestive flora.

Discussion

The meat quality of male layers is not inferior to that of broilers, while their slower growth rate thus leads to poorer economic returns42. The key lies in improving the growth performance and accelerating the breeding of male layer. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of PBC01 preparation on growth performance, immune function, and intestinal health in roosters. The findings are expected to provide a theoretical basis for the application of PBC01 in livestock and poultry production. This approach is supported by previous studies demonstrating that various Bacillus species can exert beneficial effects on animal growth performance male layermale layer43. Xu44 and Zuo et al.45 found that supplementing probiotics in broilers during the late growth period can improve growth performance, significantly reduce serum IgA, IgY, and IgM concentrations as well as the anti-inflammatory IL-10 concentration, and significantly decrease pro-inflammatory IL-1β and IL-6. This may be related to the accumulation of probiotics in the intestines, which can only positively influence if they longstanding in the intestines46,47.

Antioxidant performance has been recognized as a critical indicator for evaluating the antioxidant defense system48. In our research, we found that supplementary feeding of PBC01 could the antioxidant capacity of male layer chickens. Similarly, Bai et al49 found that the inclusion of B. subtilis in broiler diets significantly increased the expression of antioxidant enzyme genes, including nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx). Additionally, Gurram50 discovered that the supplementation of a complex feed additive containing B. subtilis resulted in a significant increase in GSH-Px and SOD levels in the serum of broilers. These findings indicate that PBC01 can enhance the antioxidant capacity not only in male layers but also in broilers.

The size and weight of immune organs are directly correlated with the immune function of the body51,52,53. The study demonstrated that at 63 d, the thymus index was significantly higher in the BH group, and the bursa of Fabricius index was significantly higher in the BM group, compared to the NC group. These results align with the findings of Zhi54, who reported that B. laterosporus S62-9 promoted increases in the spleen, thymus, and bursa of Fabricius indexes of broiler chickens by 41.67%, 33.33%, and 21.43%, respectively. This enhancement may be attributed to the addition of Cyrtochlamys S62-9, which increases the relative abundance of beneficial bacteria such as Akkermansia, Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus, while simultaneously reducing the relative abundance of pathogenic bacteria like Klebsiella and Pseudomonas. In our experiment, we observed a significant increase in the conversion rate of peripheral blood lymphocytes in the experimental groups following the supplementary feeding of B. laterosporus PBC01. This finding is consistent with the results of Stringfellow55, Lee56 and lKirjavainen57, who also reported a significant increase in lymphocyte conversion rates after supplementary feeding with probiotics.

Cytokines play a crucial role in various aspects of immunity and inflammation, encompassing innate immunity, antigen presentation, myeloid differentiation, and cell recruitment58. In this study, we observed a reduction in the mRNA expression levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-6 and TNF-α in the spleen. This reduction may be attributed to probiotics’ ability to maintain the balance between Th1 and Th2 immune responses while exhibiting robust mucosal immune adjuvant functions59,60. Probiotics enhance immune performance through multiple mechanisms61. They can improv nonspecific cellular immune responses, characterized by the activation of macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes, and the release of various cytokines in a strain-specific and dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, immune-mediated gastrointestinal diseases have been associated with diminished spleen function, with spleen atrophy considered an indicator of poor prognosis in patients with celiac disease62. In conclusion, intestinal health is closely linked to spleen function, and PBC01 has been shown to support spleen health in male layer chickens.

The small intestine plays a crucial role in digestion and absorption, with the activity of digestive enzymes and the structure of intestinal tissue being key factors in its function. Sun et al.63 found that dietary supplementation with B. amyloliquefaciens CECT 5940 increased the activities of amylase, lipase, and pancreatic coagulase in broilers. Similarly, Li et al.64 reported that B. subtilis LB-Y-1 enhanced jejunal amylase and trypsin activities in broilers. The results of this study align with these findings, as supplemental feeding of PBC01 was observed to increase protease and cellulase activity in chickens. Furthermore, our research indicates that supplemental feeding of PBC01 improves intestinal morphology by increasing the length of jejunal villi and reducing the depth of ileal crypts in male layers. This enhancement in intestinal structure facilitates better absorption of nutrients, leading to improved daily weight gain performance better, suggesting that it has an important role in outlining intestinal morphology.

The intestinal mucosal barrier comprises a mechanical barrier, a chemical barrier, an immune barrier and a biological barrier. The mechanical barrier is formed by the tightly connected intestinal mucosal epithelial tissue. The chemical barrier consists of mucus, digestive fluid, and bacteriostatic substances. The immune barrier is represented by intestinal mucosal lymphoid tissue and sIgA, while the biological barrier includes the intestinal flora, which provides resistance against foreign bacterial strains65. The intestinal epithelium serves as a critical barrier between external and internal environments, playing a vital role in the health of the organism. The tight junctions formed between intestinal epithelial cells are a significant component of this barrier66. Our findings indicate that supplementary feeding with PBC01 markedly enhances the mRNA expression of tight junction proteins. This observation aligns with previous research; for instance, Rajput67 found that the expression level of Claudin-3 in the ileum of Sanhuang chickens was significantly higher than that of the control group following the supplemental feeding of B. subtilis B10. Additionally, this supplementation resulted in increased expression of ZO-1, Claudin-1 and Occludin in laying hens. Thus, it is evident that PBC01 positively influences the jejunum and ileum by elevating the expression of tight junction proteins, thereby strengthening the intestinal mucosal barrier.

Ther intestinal tract harbors numerous commensal bacteria, collectively referred to as the microbiota, which form a microbial barrier that maintains the integrity of epithelial barrier and mucosal immune system68. The quantity and structural composition of an organism’s intestinal flora significantly influence digestion, nutrient absorption, and overall health69. Bacteroidetes can utilize substances such as starch, xylan, pectin, galactomannan and arabinogalactan70; Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacterium, common probiotics in the intestinal tract, enhance immunity and promote nutrient absorption71; Bifidobacterium, in particular, is known for its ability to resist infections. Clostridium clusters IV and XIVa may produce butyric acid in the intestine72, which provides energy by oxidizing fatty acids, and has been shown to reduce intestinal inflammatory diseases73. In this study, we found that supplementary feeding with PBC01 significantly increased the populations of Bifidobacterium, Bacteroidetes, Clostridium cluster XIVa, and Clostridium cluster IV in the ileum and cecum. Enterococcus spp.,opportunistic pathogens within the Firmicutes phylum74, can cause enteritis and various infections75. Our analysis revealed that supplementary feeding with PBC01 significantly reduced the levels of Enterococcus spp. in the cecum, thereby safeguarding intestinal health. Extensive studies have demonstrated that various Bacillus probiotics can enhance the microbial structure of the gastrointestinal tracts of livestock and poultry, including aquatic animals76, ruminants77, swine78 and poultry79,80,81. In conclusion, PBC01 can maintain intestinal microbial homeostasis and enhance the microbial barrier function of the jejunum, ileum and cecum in male layer chickens.

Conclusions

In our study, we observed that the experimental group supplemented with0.25% PBC01 exhibited significant advantages, as evidenced by the increase in body weight and feed conversion ratio throughout the entire experimental phase. Collectively, these findings indicate that the supplementary feeding of 0.25% PBC01 effectively enhance antioxidant capacity, immune function, gut microbiota homeostasis, and growth performance in male layer chickens.

Data availability

All the data supporting this article are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Kreuzer, M., Müller, S., Mazzolini, L., Messikommer, R. E. & Gangnat, I. D. M. Are dual-purpose and male layer chickens more resilient against a low-protein-low-soybean diet than slow-growing broilers?. Br Poult Sci 61, 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071668.2019.1671957 (2020).

Gangnat, I. D. M. et al. Swiss consumers’ willingness to pay and attitudes regarding dual-purpose poultry and eggs. Poult Sci 97, 1089–1098. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pex397 (2018).

Agustono, B. et al. Efficacy of dietary supplementary probiotics as substitutes for antibiotic growth promoters during the starter period on growth performances carcass traits and immune organs of male layer chicken. Vet. World 15, 324–330 (2022).

Mueller, S. et al. Carcass and meat quality of dual-purpose chickens (Lohmann Dual, Belgian Malines, Schweizerhuhn) in comparison to broiler and layer chicken types. Poult Sci 97, 3325–3336. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pey172 (2018).

Cheng, G. et al. Antimicrobial Drugs in Fighting against Antimicrobial Resistance. Front Microbiol 7, 470. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00470 (2016).

Hill, C. et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 11, 506–514. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66 (2014).

Hai, N. V. The use of probiotics in aquaculture. J Appl Microbiol 119, 917–935. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.12886 (2015).

Gao, P. et al. Feed-additive probiotics accelerate yet antibiotics delay intestinal microbiota maturation in broiler chicken. Microbiome 5, 91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-017-0315-1 (2017).

Yeo, S. et al. Development of putative probiotics as feed additives: validation in a porcine-specific gastrointestinal tract model. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100, 10043–10054 (2016).

Abd El-Tawab, M. M., Youssef, I. M. I., Bakr, H. A., Fthenakis, G. C. & Giadinis, N. D. Role of probiotics in nutrition and health of small ruminants. Pol J Vet Sci 19, 893–906. https://doi.org/10.1515/pjvs-2016-0114 (2016).

de Oliveira, J. L., Fraceto, L. F., Bravo, A. & Polanczyk, R. A. Encapsulation Strategies for Bacillus thuringiensis: From Now to the Future. J Agric Food Chem 69, 4564–4577. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.0c07118 (2021).

do Carmo Alvesdo Carmo AlvesFerreira Rodriguesda Silva CeroziPossebon Cyrino, A. P. A. R. A. B. J. E. Microencapsulation of Bacillus subtilis and oat β-glucan and their application as a synbiotic in fish feed. J Microencapsul 40, 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/02652048.2023.2220394 (2023).

Bampidis, V. et al. Safety and efficacy of a feed additive consisting of Weizmannia faecalis DSM 32016 (TechnoSpore50®) for poultry for fattening, poultry reared for laying/breeding, ornamental birds and suckling and weaned Suidae piglets (Biochem Zusatzstoffe Handels- und Produktionsgesellschaft GmbH). EFSA J 21, e08355. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2023.8355 (2023).

Yue, S., Li, Z., Hu, F. & Picimbon, J.-F. Curing piglets from diarrhea and preparation of a healthy microbiome with Bacillus treatment for industrial animal breeding. Sci. Rep. 10, 19476. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75207-1 (2020).

Luise, D. et al. Bacillus spp. Probiotic Strains as a Potential Tool for Limiting the Use of Antibiotics, and Improving the Growth and Health of Pigs and Chickens. Front Microbiol 13, 801827. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.801827 (2022).

Krachkovskiĭ, S. A. et al. Isolation, biological properties, and spatial structure of an antibiotic loloatin A. Bioorg Khim 28, 298–302 (2002).

Tian, B., Huang, W., Huang, J., Jiang, X. & Qin, L. Investigation of protease-mediated cuticle-degradation of nematodes by using an improved immunofluorescence-localization method. J Invertebr Pathol 101, 143–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2009.05.001 (2009).

Okubo, M. et al. Lupus nephropathy in New Zealand F1 hybrid mice treated by (-)15-deoxyspergualin. Kidney Int. 34, 467–473 (1988).

Barsby, T., Kelly, M. T. & Andersen, R. J. Tupuseleiamides and basiliskamides, new acyldipeptides and antifungal polyketides produced in culture by a Bacillus laterosporus isolate obtained from a tropical marine habitat. J Nat Prod 65, 1447–1451 (2002).

Kurade, M. B., Waghmode, T. R. & Govindwar, S. P. Preferential biodegradation of structurally dissimilar dyes from a mixture by Brevibacillus laterosporus. J Hazard Mater 192, 1746–1755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.07.004 (2011).

Orlova, M. V., Smirnova, T. A., Ganushkina, L. A., Yacubovich, V. Y. & Azizbekyan, R. R. Insecticidal activity of Bacillus laterosporus. Appl Environ Microbiol 64, 2723–2725 (1998).

Li, Y. et al. BLB8, an antiviral protein from Brevibacillus laterosporus strain B8, inhibits Tobacco mosaic virus infection by triggering immune response in tobacco. Pest Manag Sci 77, 4383–4392. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.6472 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Dietary Effect of Brevibacillus laterosporus S62–9 on Chicken Meat Quality, Amino Acid Profile, and Volatile Compounds. Foods https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12020288 (2023).

Hermant, Y. et al. The Total Chemical Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of the Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides. Laterocidine and Brevicidine. J Nat Prod 84, 2165–2174. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c00222 (2021).

Khaled, J. M. et al. Brevibacillus laterosporus isolated from the digestive tract of honeybees has high antimicrobial activity and promotes growth and productivity of honeybee’s colonies. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 25, 10447–10455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-0071-6 (2018).

Jin, X., Su, M., Liang, Y. & Li, Y. Effects of chlorogenic acid on growth, metabolism, antioxidation, immunity, and intestinal flora of crucian carp (Carassius auratus). Front Microbiol 13, 1084500. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1084500 (2022).

Xiao, D. et al. Efficacy of Bacillus methylotrophicus SY200 strain as feed additive against experimental Salmonella typhimurium infection in mice. Microb Pathog 141, 103978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2020.103978 (2020).

Dale, N. National Research Council Nutrient Requirements of Poultry Ninth - Ninth Revised Edition. J. Appl. Poultry Res. 3, 101. https://doi.org/10.1093/japr/3.1.101 (1994).

Xiao, D. et al. Effects of Bacillus methylotrophicus SY200 Supplementation on Growth Performance, Antioxidant Status, Intestinal Morphology, and Immune Function in Broiler Chickens. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 15, 925–940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-022-09924-6 (2023).

Nikbakht, M., Pakbin, B. & Nikbakht Brujeni, G. Evaluation of a new lymphocyte proliferation assay based on cyclic voltammetry; an alternative method. Sci. Rep. 9, 4503. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41171-8 (2019).

Wu, Y., Zhen, W., Geng, Y., Wang, Z. & Guo, Y. Pretreatment with probiotic Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 11181 ameliorates necrotic enteritis-induced intestinal barrier injury in broiler chickens. Sci. Rep. 9, 10256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46578-x (2019).

Osho, S. O. & Adeola, O. Impact of dietary chitosan oligosaccharide and its effects on coccidia challenge in broiler chickens. Br Poult Sci 60, 766–776. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071668.2019.1662887 (2019).

Emami, N. K., Calik, A., White, M. B., Young, M. & Dalloul, R. A. Necrotic Enteritis in Broiler Chickens: The Role of Tight Junctions and Mucosal Immune Responses in Alleviating the Effect of the Disease. Microorganisms https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7080231 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Effects of Antimicrobial Peptides Gal-13 on the Growth Performance, Intestinal Microbiota, Digestive Enzyme Activities, Intestinal Morphology, Antioxidative Activities, and Immunity of Broilers. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 15, 694–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-021-09905-1 (2023).

Denman, S. E. & McSweeney, C. S. Development of a real-time PCR assay for monitoring anaerobic fungal and cellulolytic bacterial populations within the rumen. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 58, 572–582 (2006).

Guo, X. et al. Development of a real-time PCR method for Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in faeces and its application to quantify intestinal population of obese and lean pigs. Lett Appl Microbiol 47, 367–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02408.x (2008).

Bartosch, S., Fite, A., Macfarlane, G. T. & McMurdo, M. E. T. Characterization of bacterial communities in feces from healthy elderly volunteers and hospitalized elderly patients by using real-time PCR and effects of antibiotic treatment on the fecal microbiota. Appl Environ Microbiol 70, 3575–3581 (2004).

Rinttilä, T., Kassinen, A., Malinen, E., Krogius, L. & Palva, A. Development of an extensive set of 16S rDNA-targeted primers for quantification of pathogenic and indigenous bacteria in faecal samples by real-time PCR. J Appl Microbiol 97, 1166–1177 (2004).

Walter, J. et al. Detection of Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Leuconostoc, and Weissella species in human feces by using group-specific PCR primers and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl Environ Microbiol 67, 2578–2585 (2001).

Matsuki, T., Watanabe, K., Fujimoto, J., Takada, T. & Tanaka, R. Use of 16S rRNA gene-targeted group-specific primers for real-time PCR analysis of predominant bacteria in human feces. Appl Environ Microbiol 70, 7220–7228 (2004).

Matsuki, T. et al. Development of 16S rRNA-gene-targeted group-specific primers for the detection and identification of predominant bacteria in human feces. Appl Environ Microbiol 68, 5445–5451 (2002).

Jaturasitha, S., Kayan, A. & Wicke, M. Carcass and meat characteristics of male chickens between Thai indigenous compared with improved layer breeds and their crossbred. Arch. Anim. Breed. 51, 283–294. https://doi.org/10.5194/aab-51-283-2008 (2008).

Wang, H. et al. Effects of compound probiotics on growth performance, rumen fermentation, blood parameters, and health status of neonatal Holstein calves. J Dairy Sci 105, 2190–2200. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2021-20721 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Effects of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis on growth performance, immunity, short chain fatty acid production, antioxidant capacity, and cecal microflora in broilers. Poult Sci 100, 101358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2021.101358 (2021).

Zou, Q., Fan, X., Xu, Y., Wang, T. & Li, D. Effects of dietary supplementation probiotic complex on growth performance, blood parameters, fecal harmful gas, and fecal microbiota in AA+ male broilers. Front Microbiol 13, 1088179. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1088179 (2022).

Leser, T. D., Knarreborg, A. & Worm, J. Germination and outgrowth of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis spores in the gastrointestinal tract of pigs. J Appl Microbiol 104, 1025–1033 (2008).

Latorre, J. D. et al. Evaluation of germination, distribution, and persistence of Bacillus subtilis spores through the gastrointestinal tract of chickens. Poult Sci 93, 1793–1800. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2013-03809 (2014).

Michalak, I. et al. Antioxidant effects of seaweeds and their active compounds on animal health and production - a review. Vet Q 42, 48–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/01652176.2022.2061744 (2022).

Bai, K. et al. Supplemental effects of probiotic Bacillus subtilis fmbJ on growth performance, antioxidant capacity, and meat quality of broiler chickens. Poult Sci 96, 74–82 (2017).

Gurram, S. et al. Synergistic effect of probiotic, chicory root powder and coriander seed powder on growth performance, antioxidant activity and gut health of broiler chickens. PLoS ONE 17, e0270231. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270231 (2022).

Farag, M. R. et al. In ovo protective effects of chicoric and rosmarinic acids against Thiacloprid-induced cytotoxicity, oxidative stress, and growth retardation on newly hatched chicks. Poult Sci 102, 102487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2023.102487 (2023).

Islam, R., Sultana, N., Haque, Z. & Rafiqul Islam, M. Effect of dietary dexamethasone on the morphologic and morphometric adaptations in the lymphoid organs and mortality rate in broilers. Vet Med Sci 9, 1656–1665. https://doi.org/10.1002/vms3.1139 (2023).

Chang, Q., Lu, Y. & Lan, R. Chitosan oligosaccharide as an effective feed additive to maintain growth performance, meat quality, muscle glycolytic metabolism, and oxidative status in yellow-feather broilers under heat stress. Poult Sci 99, 4824–4831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2020.06.071 (2020).

Zhi, T. et al. Dietary Supplementation of Brevibacillus laterosporus S62–9 Improves Broiler Growth and Immunity by Regulating Cecal Microbiota and Metabolites. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 16, 949–963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-023-10088-0 (2024).

Stringfellow, K. et al. Evaluation of probiotic administration on the immune response of coccidiosis-vaccinated broilers. Poult Sci 90, 1652–1658. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2010-01026 (2011).

Lee, K. W. et al. Effects of direct-fed microbials on growth performance, gut morphometry, and immune characteristics in broiler chickens. Poult Sci 89, 203–216. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2009-00418 (2010).

Kirjavainen, P. V., ElNezami, H. S., Salminen, S. J., Ahokas, J. T. & Wright, P. F. Effects of orally administered viable Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Propionibacterium freudenreichii subsp. shermanii JS on mouse lymphocyte proliferation. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 6, 799–802 (1999).

Borish, L. C. & Steinke, J. W. 2. Cytokines and chemokines. J Allergy Clin Immunol 111, S460–S475 (2003).

Chen, B. et al. Surface Display of Duck Hepatitis A Virus Type 1 VP1 Protein on Bacillus subtilis Spores Elicits Specific Systemic and Mucosal Immune Responses on Mice. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-024-10323-2 (2024).

Chen, B. et al. Targeted Screening of Fiber Degrading Bacteria with Probiotic Function in Herbivore Feces. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-024-10215-5 (2024).

Ashraf, R. & Shah, N. P. Immune system stimulation by probiotic microorganisms. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 54, 938–956. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2011.619671 (2014).

Di Sabatino, A., Carsetti, R. & Corazza, G. R. Post-splenectomy and hyposplenic states. Lancet (London, England) 378, 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61493-6 (2011).

Sun, Y. et al. Effects of dietary Bacillus amyloliquefaciens CECT 5940 supplementation on growth performance, antioxidant status, immunity, and digestive enzyme activity of broilers fed corn-wheat-soybean meal diets. Poult Sci 101, 101585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2021.101585 (2022).

Li, C. et al. Screening and characterization of Bacillus velezensis LB-Y-1 toward selection as a potential probiotic for poultry with multi-enzyme production property. Front Microbiol 14, 1143265. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1143265 (2023).

Natividad, J. M. M. & Verdu, E. F. Modulation of intestinal barrier by intestinal microbiota: pathological and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol Res 69, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2012.10.007 (2013).

Camilleri, M., Madsen, K., Spiller, R., Greenwood-Van Meerveld, B. & Verne, G. N. Intestinal barrier function in health and gastrointestinal disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil 24, 503–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01921.x (2012).

Rajput, I. R. et al. Effect of Saccharomyces boulardii and Bacillus subtilis B10 on intestinal ultrastructure modulation and mucosal immunity development mechanism in broiler chickens. Poult Sci 92, 956–965. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2012-02845 (2013).

Kayama, H., Okumura, R. & Takeda, K. Interaction Between the Microbiota, Epithelia, and Immune Cells in the Intestine. Annu Rev Immunol 38, 23–48. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-070119-115104 (2020).

Zhang, H., Huang, L., Hu, S., Qin, X. & Wang, X. Moringa oleifera Leaf Powder as New Source of Protein-Based Feedstuff Improves Growth Performance and Cecal Microbial Diversity of Broiler Chicken. Animals (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13061104 (2023).

Martens, E. C. et al. Recognition and degradation of plant cell wall polysaccharides by two human gut symbionts. PLoS Biol 9, e1001221. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001221 (2011).

Chen, J., Chen, X. & Ho, C. L. Recent Development of Probiotic Bifidobacteria for Treating Human Diseases. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 9, 770248. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2021.770248 (2021).

Moens, F. & De Vuyst, L. Inulin-type fructan degradation capacity of Clostridium cluster IV and XIVa butyrate-producing colon bacteria and their associated metabolic outcomes. Benef Microbes 8, 473–490. https://doi.org/10.3920/BM2016.0142 (2017).

Zhang, M. et al. Mechanistic basis and preliminary practice of butyric acid and butyrate sodium to mitigate gut inflammatory diseases: a comprehensive review. Nutr Res https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2021.08.007 (2021).

Arias, C. A. & Murray, B. E. The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol 10, 266–278. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2761 (2012).

Růžičková, M., Vítězová, M. & Kushkevych, I. The Characterization of Enterococcus Genus: Resistance Mechanisms and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Open Med (Wars) 15, 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2020-0032 (2020).

Zhou, P. et al. Comparative Study of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens X030 on the Intestinal Flora and Antibacterial Activity Against Aeromonas of Grass Carp. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 12, 815436. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.815436 (2022).

Schofield, B. J. et al. Beneficial changes in rumen bacterial community profile in sheep and dairy calves as a result of feeding the probiotic Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57. J Appl Microbiol 124, 855–866. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.13688 (2018).

Ding, H. et al. Dietary supplementation with Bacillus subtilis and xylo-oligosaccharides improves growth performance and intestinal morphology and alters intestinal microbiota and metabolites in weaned piglets. Food Funct 12, 5837–5849. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1fo00208b (2021).

Yang, J. et al. Combined Use of Bacillus subtilis yb-114,246 and Bacillus licheniformis yb-214,245 Improves Body Growth Performance of Chinese Huainan Partridge Shank Chickens by Enhancing Intestinal Digestive Profiles. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 13, 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-020-09691-2 (2021).

Zou, X. Y. et al. Bacillus subtilis inhibits intestinal inflammation and oxidative stress by regulating gut flora and related metabolites in laying hens. Animal 16, 100474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.animal.2022.100474 (2022).

Neveling, D. P. & Dicks, L. M. T. Probiotics: an Antibiotic Replacement Strategy for Healthy Broilers and Productive Rearing. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-020-09640-z (2021).

Funding

This research was funded by the Technology Innovation Research Team in the University of Sichuan Province (Award Number: KM406183.1), and Sichuan Agricultural University Double Branch Program (Award Number: 03571146) and Sichuan Province “TianfuQingcheng Plan” Tianfu agricultural master project (Award Number: ChuanQingcheng 1309).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Formal analysis and Writing – original draf L. F.; Data curation, Y. C., N. Y. and Y. Y.; Funding acquisition, X. N. and K. P.; Investigation, M. Z. and Y. Z.; Writing – review & editing: all authors; Methodology, D. Z. and X. N.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fei, L., Cao, Y., Yang, Y. et al. A probiotic Brevibacillus laterosporus promotes chicken growth performance immunity and gut health. Sci Rep 16, 21 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29309-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29309-3