Abstract

Synthetic plastics dominate global markets but pose severe ecological threats through persistence and xenobiotic release. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), microbial biopolymers, offer biodegradable alternatives with tunable properties. This study isolated high-yield PHA-producing bacteria from petroleum-contaminated soils in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Five strains Paenibacillus lautus (MA2), Alcaligenes pakistanensis (MA3), Acinetobacter baumannii (MB1), Bacillus cereus (MB4), and Bacillus tropicus (MC3) were identified via 16 S rRNA sequencing against the NCBI BLAST database. Initial screening employed Sudan Black B staining for PHA granules. Antimicrobial susceptibility and enzyme assays evaluated strain ecology and utility. Cultures grew in modified glucose-tryptone-yeast extract-nutrient (GTYN) medium. Optimization revealed peak PHA yields at pH 7.0, 35–40 °C, with glucose and tryptone as optimal carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively. Incubation for 60–70 h maximized production at 70.44 ± 0.08% dry cell weight. PHAs extracted via sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) precipitation underwent structural analysis. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy detected signature bands: 1723–1740 cm⁻¹ (C = O stretch), 2922–2923 cm⁻¹ (CH₂ asymmetric stretch), 1634 cm⁻¹ (C = C), and 1231–1278 cm⁻¹ (C–O stretch), indicative of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV). Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (¹H NMR) confirmed copolymer composition, with 3-hydroxybutyrate signals at δ 1.28 ppm (CH₃), δ 2.56 ppm (CH₂–CO–), and δ 5.25 ppm (–CH–O–); 3-hydroxyvalerate peaks appeared at δ 0.9 ppm (terminal CH₃), δ 1.6–1.8 ppm (CH₂–), and δ 2.4–2.6 ppm (CH₂–CO–). These findings affirm the biopolymers’ authenticity and versatility, supporting applications in biomedicine, biotechnology, and sustainable manufacturing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Synthetic plastics have revolutionized manufacturing and packaging due to their low cost, lightweight nature, energy efficiency, durability, and ease of molding. However, their widespread use has triggered severe environmental and health crises. These materials resist natural degradation and persist in ecosystems for centuries1. Incineration of plastic waste releases substantial greenhouse gases, such as methane (CH₄) and carbon dioxide (CO₂), exacerbating global warming2. Notably, CO₂ and CH₄ can serve as substrates for sustainable polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production3. Microorganisms like cyanobacteria and methanotrophs utilize these gases to synthesize PHAs, mitigating atmospheric GHG levels while providing eco-friendly feedstocks for biopolymers. As xenobiotics, synthetic plastics often exhibit carcinogenic properties, adversely affecting humans, wildlife, and plants4. Their accumulation and non-biodegradability raise urgent environmental alarms. Meanwhile, dwindling petrochemical reserves demand viable alternatives. This urgency has fueled interest in biodegradable polymers from plants, animals, and microbes, which mimic conventional plastics’ properties5. Among these, PHAs stand out as microbial polyesters with strong potential to supplant petroleum-based polymers, addressing global disposal challenges. Their compostability, biocompatibility, thermal stability, and durability position them for broad market adoption6.

Microbes offer a renewable route to biopolymers, accumulated intracellularly under stress conditions. PHAs, a key family of such polyesters, hold commercial and ecological promise7. For instance, Bacillus megaterium accumulates up to 90% dry cell weight as poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB), a hydrophobic PHA, in carbon-rich, nutrient-poor media8. These polymers act as carbon and energy stores, aiding survival during nitrogen, phosphorus, or magnesium limitation9. PHB and its copolymer poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV) are the most studied, boasting versatile physicochemical traits for biodegradable applications5.

Over 300 bacterial species and numerous archaea produce PHAs across diverse niches, from soils and oceans to hypersaline lakes and hot springs10. Extremophiles, including thermophiles and halophiles, excel in harsh conditions, ideal for industrial PHA scaling11. Key genera encompass Bacillus megaterium, Cupriavidus necator (formerly Alcaligenes eutrophus), Alcaligenes latus, Bacillus spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, engineered Escherichia coli, and Halococcus spp. Other producers include Aeromonas hydrophila, Thiococcus pfennigii, Comamonas spp., Pseudomonas putida, Burkholderia spp., Thermus thermophilus, Ralstonia eutropha, Chromobacterium spp., and Clostridium kluyveri12. Pseudomonas spp. yield medium-chain-length (MCL) PHAs with superior flexibility compared to short-chain-length (SCL) versions from C. necator or B. megaterium13. Salt-tolerant Halomonas spp. enable cost-effective, non-sterile fermentations. Engineered E. coli strains further boost yields and tailor compositions for targeted uses14. This metabolic versatility underscores PHAs’ role in sustainable, application-specific bioplastics15. In Pakistan, PHA-producing bacteria from varied habitats include Bacillus spp., Pseudomonas spp., Stenotrophomonas, and Rhodococcus. Local studies confirm accumulation via low-cost substrates like sugarcane molasses and rice bran16. Yields vary but show scale-up potential post-optimization, leveraging wastes for economical, eco-friendly production17. PHB biosynthesis, the paradigm for PHAs, unfolds in three enzyme-driven steps in the cytoplasm. First, β-ketothiolase (PhaA) condenses two acetyl-CoA units from glycolysis into acetoacetyl-CoA, linking central metabolism to polymer synthesis. Next, acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhaB) reduces it to (R)-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA using NADPH, tying production to cellular redox status. Finally, PHA synthase (PhaC) polymerizes monomers into high-molecular-weight PHB granules, reaching 90% dry weight under carbon excess and nutrient scarcity18. Carbon source type profoundly influences PHA yield and composition. Simple sugars like glucose favor SCL-PHAs such as PHB, while lipids promote MCL variants19. ]. Nutrient imbalances—e.g., low nitrogen or oxygen with ample carbon—divert acetyl-CoA toward accumulation over growth20. Optimizing pH, temperature, aeration, and substrates tailors yields to strain-specific metabolism21.

Monomer chain length dictates PHA properties, including tensile strength, crystallinity, melting point, elasticity, and brittleness. SCL-PHAs (3–5 carbons), like PHB and PHBV, exhibit high crystallinity, ~ 175 °C melting points, and rigidity, suiting structural uses despite fragility18,22. Ultra-long-chain PHAs (> 14 carbons) remain underexplored but promise unique thermal and mechanical profiles23. This tunability supports applications in packaging, agriculture, and biomedicine24.

This study isolated PHA-producing bacteria from hydrocarbon-contaminated soils in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Isolates underwent Sudan Black B screening, biochemical profiling, and enzyme assays. Production optimization targeted pH, temperature, carbon/nitrogen sources, and incubation time. PHAs were extracted via sodium hypochlorite digestion for high recovery. Structural validation employed Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and proton nuclear magnetic resonance (¹H NMR) to identify signature groups. These indigenous strains highlight prospects for cost-effective, sustainable PHA biomanufacturing.

Materials and methodology

Sample collection

Three different sites: the Rawalpindi Waste Management Company (RWMC) landfill, the Losar landfill site, and another RWMC site were used to gather 10 g of contaminated soil. Samples were obtained from the top 10–15 cm of soil using a sterile spatula, placed in sterile polyethylene bags, and transported to the laboratory under cold chain conditions (4 °C). Sampling was conducted in triplicate to ensure representativeness and stored at 4 °C until analysis to minimize microbial activity.

Media preparation

A modified Glucose-Tryptone-Yeast Extract-Nutrient (GTYN) medium was prepared by dissolving tryptone (2 g/L), yeast extract (2.5 g/L), and NaCl (1.25 g/L) in 300 mL of distilled water in a 500 mL Erlenmeyer flask. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 ± 0.1 using 1 M HCl or 1 M NaOH, verified with a calibrated pH meter. The medium was autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min. A glucose solution (15 g/L) was separately sterilized via 0.22 μm syringe filtration and aseptically added to the cooled medium to prevent thermal degradation of glucose25.

Isolation of bacterial strains

About 1 g of soil from each soil sample was used in the serial dilution method with dilutions ranging from 10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁶, and 0.5 ml of dilutions was spread on GTYN media petri plates. Incubate petri plates at 37 °C for 24 h. Different bacterial colonies appeared and prepared for pure cultures in GTYN media26.

Screening and identification of selected bacterial strains

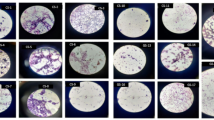

Preliminary screening for polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production was conducted using Sudan Black B staining. Bacterial cultures were smeared on glass slides, stained, and observed under a light microscope (1000× magnification). Strains exhibiting dark blue-black intracellular granules were identified as PHA producers. Selected strains with high PHA granule abundance were subjected to further analysis27.

Genomic DNA was extracted using a modified phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol method optimized for soil-derived bacteria. The 16 S rRNA gene was amplified via PCR using universal primers 27 F (5’-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3’) and 1492R (5’-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3’) to ensure amplification of a near-full-length gene fragment (~ 1.5 kb). PCR conditions included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 90 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. Amplified products were purified and sequences were analyzed using BLASTn against the NCBI GenBank database to identify closest matches. Phylogenetic relationships were inferred using MEGA 7.0 software with the neighbor-joining algorithm, supported by 1000 bootstrap replicates to ensure robust tree topology28.

Screening of antibacterial activity

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed on the chosen strains for ciprofloxacin (5 mg), nalidixic acid (30 mg), nitrofurantoin (300 mg), ofloxacin (5 mg), cefixime (5 mg), ceftriaxone (30 mg), levofloxacin (5 mg), and vancomycin (30 mg)29.

Screening of enzyme assay

The enzyme activity of the selected strains was examined for cellulase, lipase, amylase, and protease. The enzyme activity of the selected bacterial strains was assessed for cellulase, lipase, amylase, and protease production. For cellulase activity, strains were spot-inoculated on carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) agar plates and incubated at 30–37 °C for 24–48 h. After incubation, the plates were flooded with 0.1% Congo red solution and subsequently washed with 1 M NaCl to visualize clear hydrolysis zones, indicating cellulase activity. Lipase activity was determined by inoculating strains on tributyrin agar plates and incubating under similar conditions; the appearance of clear halos around the colonies confirmed lipase production. For amylase activity, strains were cultured on starch agar plates, incubated, and then flooded with iodine solution; clear zones around the colonies signified starch hydrolysis and amylase production. Protease activity was evaluated on skim milk agar plates, where the formation of clear zones around bacterial growth after incubation indicated casein degradation by protease enzymes. All assays were conducted in triplicates, and the diameters of the hydrolysis zones were measured to compare enzyme activity levels30.

Optimization of physicochemical parameters

The selected strains were optimized for pH (3, 5, 7, 9, and 11) and temperature (25, 30, 35, 40, and 45 °C). Different carbon sources (glucose, lactose, fructose, pyruvate, and glycolate) were used to get the maximum amount of PHA. Different nitrogen sources (tryptone, peptone, and ammonium chloride) were used to obtain the highest PHA production. The effect of time is a very important parameter for revealing the best time for harvesting PHA from bacterial strains. The PHA production was carried out at different time periods, i.e., 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84, and 96 h25. The experiments were performed in duplicate.

PHA extraction by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) method

For a complete dispersion of pellet in water, 1 g of pellet was added to 100 mL of distilled water, and the solution was sonicated using an ultrasonicator (35 kHz, 285 W, 25 °C) for 20 min. A 1:1 mixture of SDS and pellet solution in water was added. The solution was incubated for 1 h at 50 °C before being autoclaved for 20 min at 121 °C. After cooling, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C. The pellet was then washed twice with distilled water. Overnight, the pellet was left to dry. The dried PHA was weighed, and the PHA yield was calculated31.

The PHA yield was calculated by following equation:

Characterization of PHA

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

Different chemical functional groups of PHA were checked by FTIR analysis. In this study, the ATR-FTIR (Parkin Elmer Spectrum 65 FTIR) spectrometer was used for the structural analysis of dried PHA produced by isolates. To verify the presence of specific functional groups, the extracted PHB samples were processed for Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopic investigation. In order to get rid of any remaining cell debris, medium components, or contaminants, the PHB was first washed by repeatedly washing it with distilled water, acetone, and ethanol. Following purification, the PHB was vacuum-dried at 40–50 °C until its weight remained consistent. About 2–5 mg of the dried PHB was crushed into a fine powder for FTIR analysis. An FTIR spectrometer was then used to investigate the extracted pellets containing the PHB sample at a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹ across a scanning range of 4000 –400 cm⁻¹32.

Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (¹H-NMR)

¹H-NMR is a useful application of nuclear magnetic resonance in NMR spectroscopy. This technique is used for the determination of the structure of the required molecule, with respect to the hydrogen-1 nuclei within the molecule of a substance. The AVANCE 300 B spectrometer (Bruker 300 MHz NMR) is used for the determination of ¹H-NMR of PHA. The H-NMR analysis was done with the PHA produced by the MC3 strain, as the PHA yield produced by it was the highest. About 20 mg of polymer samples produced by MC3 was dissolved in chloroform-d (CdCl₃), vortexed for 10 min, and 0.75 mL of the solution was placed in the NMR tube33.

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were performed in duplicate. Standard error was calculated and ANOVA was also applied.

Results

Screening and identification of selected bacterial strains

The bacterial isolates were initially tested for polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) accumulation using Sudan Black B staining. Sudan Black B staining is a rapid, reliable, and cost-effective screening technique used to detect polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA)-producing bacteria. PHAs are intracellular carbon and energy storage materials accumulated by microorganisms under nutrient-limited and carbon-rich conditions. The dye, Sudan Black B, has a strong affinity for lipid-like granules, including PHAs, making it easy to visualize under a light microscope. This method is particularly useful during initial bioprospecting or screening stages, helping researchers differentiate PHA-accumulating strains from non-producers and narrow down candidates for further biochemical and molecular characterization. Among the total of 12 isolates, MA2, MA3, MB1, MB4, and MC3 had substantial intracellular lipid inclusions, indicating high PHA synthesis. These five isolates were then selected for further optimization of growth and production parameters (Table 1) The study analyzed the enzymatic profiles of various strains of bacteria, revealing significant variability in their substrate utilization potential and industrial relevance. The strains showed strong amylolytic activity, proteolytic activity, lipolytic activity, and lignocellulosic activity, making them potential candidates for waste oil-based PHA production. Strains like MA2, MA3, and MB4 showed high PHA production and diverse enzymatic activity, making them ideal for industrial applications.

The phylogenetic tree in Fig. 1 was created using 16 S rRNA gene sequences from bacterial isolates MA2, MA3, MB1, MB4, and MC3, and reference sequences from the NCBI GenBank database. The relationships were inferred using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method and the Kimura 2-parameter model. A bootstrap analysis with 1000 replications assessed the tree’s reliability, showing robust branch support with bootstrap values ≥ 70%. Molecular identification through 16 S rRNA gene sequencing revealed the phylogenetic affiliations of the isolates, as shown in the constructed phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1). MA2 was closely linked to Paenibacillus lautus (GenBank accession no. ON968691.1), MA3 to Alcaligenes pakistanensis (ON968709.1), MB1 to Acinetobacter baumannii (ON968725.1), MB4 to Bacillus cereus (ON968695.1), and MC3 to Bacillus tropicus (ON968610.1).

Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of the selected isolates

Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of five bacterial strains (MA2, MA3, MB1, MB4, and MC3) indicate that Nalidixic acid shows the highest sensitivity, ranging from 87% (MB4) to 99% (MA3) [Table 2]. Nitrofurantoin is also effective, particularly against MA2 (90%) and MB4 (98%). MC3 has the highest sensitivity to several antibiotics, notably cefixime (98%) and ciprofloxacin (99%). Conversely, MB1 demonstrates low sensitivity with decreased sensitivity to Ciprofloxacin and Nitrofurantoin (both 45%). Vancomycin shows poor efficacy across strains, particularly in MB4 (16%). These findings are crucial for industrial bioprocessing, where antibiotic resistance may affect bacterial growth and PHA synthesis.

Enzyme assay assessment

Twelve bacterial strains (MA1–MA4, MB1–MB4, and MC1–MC4) were screened for their ability to produce polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) and for various hydrolytic enzyme activities, including amylolytic, proteolytic, lipolytic, and cellulolytic activity. Sudan Black B staining was used to visually confirm the accumulation of PHA granules inside the bacterial cells. The intensity of staining varied among the isolates, ranging from weak to strong. Strains MA2, MA3, MB1, MB4, and MC3 showed strong Sudan Black B staining (+++), indicating high levels of intracellular PHA accumulation. These strains were also categorized as good PHA producers, suggesting a direct relationship between the staining intensity and PHA synthesis capability. Moderate staining (++) was observed in strains MA4 and MC2, which showed normal PHA production, while weakly stained isolates such as MA1, MB2, MB3, MC1, and MC4 showed poor PHA accumulation.

The enzymatic profile of the isolates showed noticeable variation. Strong amylolytic activity (+++) was observed in MA4 and MB2, while MA2, MA3, and MC2 showed moderate activity (++). In contrast, MB1, MB3, MC1, and MC4 did not show any amylolytic activity. Proteolytic activity was prominent in MA3, MB2, MB4, and MC3, while other strains showed only weak or moderate levels. Lipolytic activity was also variable; strains MA1, MB1, MB4, MC2, and MC4 exhibited moderate activity, whereas MA4 and MB3 showed no lipase production. Cellulolytic activity was highest in MA4, MB4, and MC2, with strong (+++) results, while the rest showed low to moderate activity.

Comparing PHA production with enzyme activity, it was observed that strains with strong PHA accumulation often possessed higher hydrolytic enzyme activity. For example, MA3 and MB4, which showed good PHA production, also had high proteolytic activity, indicating their ability to utilize protein-rich substrates efficiently. Similarly, MA2 and MC3 displayed good PHA production along with moderate amylolytic and lipolytic activities, suggesting that these strains can degrade starch and lipids effectively to generate carbon sources for PHA synthesis. Interestingly, some strains like MA4 and MC2, although showing strong amylolytic or cellulolytic activity, had only normal PHA production, which indicates that the efficiency of substrate degradation alone does not guarantee high PHA accumulation. The metabolic regulation and balance between energy generation and polymer storage might influence the overall PHA yield. Overall, the results suggest that bacterial strains exhibiting multiple hydrolytic enzyme activities tend to have better potential for PHA production. Such strains are metabolically versatile and can utilize a wide range of organic materials. Among all isolates, MA3, MB4, and MC3 appeared to be the most promising candidates due to their combination of strong PHA production and diverse enzyme activities. These strains could be valuable for biotechnological applications, especially for converting complex waste materials into biodegradable plastics.

Optimization of physicochemical parameters

The effect of pH on bacterial growth showed that all isolates grew optimally at pH 7. Temperature optimization found that the best biomass output occurred between 35 °C and 40 °C. Carbon sources were evaluated, and glucose was shown to promote optimum development across all isolates, while lactose also contributed significantly to biomass production. Furthermore, fructose and pyruvate were discovered to be highly effective carbon sources for isolates MB4 and MC3. Among the nitrogen sources studied, tryptone had the highest growth rates, followed by peptone, which also produced successful outcomes.

The optimal PHA production was observed at 60 and 72 h of incubation, with 72 h being selected for further production experiments. PHA extraction was performed using the SDS-based method under these optimized conditions, and PHA yields were quantified, revealing that isolates MA2, MA3, and MC3 produced the highest levels of PHA, with yields ranging between 60% and 70% of cell dry weight (Fig. 2). Incubation time was found to be a critical factor in maximizing PHA accumulation.

Characterization of PHA

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

The structural characterization of Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) produced by bacterial strains was conducted using Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy. The PHA samples showed characteristic absorption bands consistent with the known functional groups in PHAs, specifically PHB and PHBV. Key functional groups and their corresponding wavenumbers include C = O Stretching (Ester Group), CH₂ Asymmetric Stretching (CH₂ Asymmetric), C = C Stretching (C = C Double Bonds), C–O Stretching (Ether or Ester Linkages), and CH₃ Bending (–CH₃). These bands confirm the polymeric nature of the isolated biopolymer and validate its structural resemblance to known Polyhydroxyalkanoates. The presence of ester and alkyl groups supports the claim that the polymer is a biodegradable material with potential applications in the production of eco-friendly bioplastics. The PHA sample was obtained from bacterial strains MA2, MA3, MB1, MB4, and MC3 produced in modified GTYN medium and extracted by the sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) method. The FTIR spectrum of the sample produced by MA2 showed absorption bands at 3278, 2922, 1723, 1634, 1378, 1278 cm⁻¹, 1420, 1375, and 1244 cm־¹. The FTIR spectrum of the sample produced by MA3 showed absorption bands at 3279, 1723, 1634, 1448, 1278, 1379, and 1278 cm⁻¹. The FTIR spectrum of the sample produced by MB1 showed absorption bands at 3279, 2923, 1740, 1634, 1451, and 1231 cm⁻¹. The FTIR spectrum of the sample produced by MB4 showed absorption bands at 3280, 2922, 1634, 1394, 1314, and 1243 cm⁻¹. The FTIR spectrum of the sample produced by MC3 showed absorption bands at 3272, 2922, 1634, 1453, 1313, and 1233 cm⁻¹ (Fig. 3a, b,c, d,e). These peaks represented the –CH and –CH₂ anti-symmetric stretching, C–O and C = O groups, –CH and –CH₂ anti-symmetric stretching, and –CH₃ deformation vibration (Fig. 3a, b, c, d, e).

Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (¹H-NMR)

The peaks 1 and 3 appeared at 2.62 ppm were corresponding to the CH₂ groups of HB and HV. The peak 6 indicated at 1.62 ppm was representing the CH₂ group of HV and the peaks 2 and 4 showed at 5.24 ppm were corresponding to the CH groups of HB and HV. Saleem et al.,34 and Liu et al., (2010)6 reported about the characteristics peak at 0.90 and 1.25 ppm in ¹ H-NMR spectrum can be used for the determination of HV composition of PHBV sample by the following equation:

The structural elucidation of the extracted biopolymer was carried out using ¹H Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and the representative spectrum is shown in Fig. 4. The spectrum confirms that the polymer is a copolymer of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) [PHB-co-PHV], consisting of both 3-hydroxybutyrate (3HB) and 3-hydroxyvalerate (3HV) monomer units. The characteristic proton signals of the 3HB monomer were observed at δ = 1.28 ppm, corresponding to the methyl (–CH₃) group, δ = 2.56 ppm for the methylene (–CH₂–) group adjacent to the carbonyl carbon, and δ = 5.25 ppm for the methine (–CH–) proton attached to the oxygen atom. Similarly, the 3HV monomer exhibited signals at δ = 0.9 ppm (terminal –CH₃ group), δ = 1.6–1.8 ppm (methylene protons –CH₂–), and δ = 2.4–2.6 ppm (methylene group adjacent to the carbonyl carbon). The presence of these distinct peaks confirms the successful incorporation of both 3HB and 3HV units into the polymer backbone, validating the copolymeric nature of the extracted PHA. The absence of any impurity peaks further indicates the high purity of the biopolymer.

Discussion

The predominant use of conventional plastics derived from petroleum poses significant environmental challenges, as they are non-biodegradable and persist in the environment for generations. With approximately 180 million tons produced annually, much of this plastic waste contaminates land and marine ecosystem. The manufacturing processes often involve toxic substances, raising health concerns35. Consequently, there is a crucial need for non-toxic, biodegradable alternatives. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) represent a promising class of biopolymers, created by bacteria, that offer comparable thermoplastic properties to traditional plastics along with biodegradability and biocompatibility. The growing interest in sustainable substitutes for petrochemical plastics has led to the exploration of bio-based polymers, especially Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs)36. These natural polyesters, produced by various organisms, show promise as bioplastics37. Recent developments aim to utilize agroindustrial wastes such as cacao shells, cheese whey, wine byproducts, wood, and beet molasses as economical substrates for PHA production, though further optimization is necessary to enhance process efficiency38.

The study aimed to determine the selection of bacterial isolates MA2, MA3, MB1, MB4, and MC3 for polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production using Sudan Black B staining. A quantitative measure was used, evaluating the percentage of cells containing PHA globules. A threshold of ≥ 50% of cells exhibiting visible PHA granules was used for strong PHA producers. The results were compared to previously reported values for known PHA-producing bacteria, providing a more objective basis for isolate selection. Wei et al.. in 2011 evaluated local indigenous strains C. taiwanensis 184, 185, 186, 187, 204, 208, 209, and Pseudomonas oleovorans ATCC 29,347 to select a PHA production strain. PHA production and type were verified using Sudan Black staining, Gas Chromatography, and Infrared. C. taiwanensis 184 showed significant PHA granules and the highest PHA production of 0.14 g/L and 10% more PHA content than other strains39.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing is crucial for understanding the ecological and industrial relevance of bacterial strains. It helps in selecting strains that can tolerate environmental stresses, such as antibiotics, and assessing their stress response and ability to produce Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA). This is particularly important for industrial-scale PHA production, where strains that can tolerate environmental stresses are more likely to thrive. Antibiotic resistance can indicate genetic adaptations beneficial for PHA production, such as enhanced membrane permeability or protective metabolites. Testing for antimicrobial susceptibility also ensures the safety and adaptability of bacteria for large-scale and environmentally sustainable PHA production. In conclusion, while antimicrobial susceptibility does not directly influence PHA production, it provides valuable insights into the ecological and industrial relevance of bacterial strains, guiding strain selection, offering stress tolerance mechanisms, and ensuring the safety and adaptability of bacteria for large-scale and environmentally sustainable PHA production40. The results show that various bacterial strains clearly differ in their sensitivity to antibiotics. Nalidixic acid may be the recommended first-line therapy for infections brought on by these strains due to its consistently high sensitivity. Its broad-spectrum potential and ongoing significance in antimicrobial treatment are shown by its efficacy against all strains. Additionally, nitrofurantoin and ofloxacin showed high effectiveness, especially for MA2 and MB4, indicating their potential use in treating infections linked to these strains. However, MB1 limited responsiveness to many antibiotics and Ceftriaxone resistance raise concerns about multi-drug resistance and may call for combination therapy or other therapeutic options. It is interesting to note that MC3 exhibited great sensitivity to almost every antibiotic examined, indicating that it might not have yet established notable resistance mechanisms. MB1 and MB4, on the other hand, showed poor responses to a number of antibiotics, highlighting the significance of strain-specific sensitivity testing. The production of Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) by bacteria is influenced by environmental stress, nutrient availability, and exposure to antimicrobial agents. Antibiotics can alter bacterial metabolism, either promoting or inhibiting PHA accumulation. This study evaluated the antibiotic susceptibility profiles of various bacterial strains, focusing on their impact on PHA production. High-sensitivity antibiotics like Nalidixic acid and Ciprofloxacin may inhibit DNA replication and cell division, potentially limiting PHA accumulation. However, sub-lethal concentrations of certain antibiotics can induce stress responses, potentially triggering PHA biosynthesis as a protective mechanism. Strains like MC3 can still produce PHAs if appropriate conditions are maintained, while MB1 and MB4 may retain better growth and consistent PHA production unless severely stressed. Antibiotic pressure may also select PHA-producing strains with adaptive resistance traits41.

The PHA is synthesized by microorganisms, including both Gram-positive and -negative bacteria. Bacillus sp., including Bacillus megaterium NCIM 247534, Bacillus cereus YB-4, Bacillus cereus SPV, Bacillus sp. INT005, Bacillus cereus UW85, and were found to produce PHB, PHBV, and PHBHHx. The latter are specifically known to produce PHA. Large-scale PHA production is necessary since it has uses in biomedicine and the environment. In order to improve the quantity of PHA output, several growth conditions were adjusted for PHA production on a pilot scale30. Alcaligenes latus sp. was also discovered to synthesize the biopolymer PHA. The PHA output was 53.65% when sugarcane was present as a carbon source. There is another study in which Paenibacillus durus BV-1, isolated from oil mill soil, produced PHA in the presence of fructose as a carbon source. Different species of Acinetobacter, like Acinetobacter lwoffii, Acinetobacter johnsonii, and Acinetobacter junii, also produced PHA in the form of PHB and PHBV in the presence of different carbon sources42.

Microorganisms such as Gram-positive and -negative bacteria are involved in synthesizing the PHA. Specifically, Bacillus sp. are reported for PHA production, such as Bacillus megaterium NCIM 247541, Bacillus cereus, Bacillus cereus YB-4, Bacillus cereus SPV, Bacillus sp. INT005, Bacillus cereus UW85, and Bacillus sp.43 were reported to synthesize PHB, PHBV, and PHBHHx. PHA production is useful in environmental and biomedical applications, so there is a need to produce PHA on a large scale. Different culture conditions were optimized for the PHA production on a pilot scale so that the amount of PHA yield increased. It was reported that biopolymer PHA was also produced by Alcaligenes latus sp. In the presence of sugarcane as a carbon source, the PHA yield was 53.65%44. There is another study in which Paenibacillus durus BV-1, isolated from oil mill soil, produced PHA in the presence of fructose as a carbon source45. Different species of Acinetobacter, like Acinetobacter lwoffii, Acinetobacter johnsonii, Acinetobacter junii, and Acinetobacter, also produced PHA in the form of PHB and PHBV in the presence of different carbon sources46. The study focused on optimizing glucose and tryptone as the best carbon and nitrogen sources for Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) production by isolates. However, co-substrates could potentially enhance PHA yield by acting as an additional carbon source, facilitating the accumulation of PHA during the stationary phase of growth. These co-substrates could also provide a more diverse pool of precursors, further supporting the biosynthesis of PHA under nutrient-limited conditions. Future studies should explore the impact of such co-substrates on PHA production, especially under varying environmental conditions, to fully optimize the yield and quality of PHA from these isolates. In discussion on PHA biosynthesis, the key enzymatic pathways involve β-ketothiolase (PhaA), acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhaB), and PHA synthase (PhaC). PhaA catalyzes the formation of acetoacetyl-CoA from acetyl-CoA, regulated by intracellular levels of acetyl-CoA and CoA, linking polymer accumulation to carbon metabolism and nutrient status. PhaB reduces acetoacetyl-CoA to (R)-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA, a step sensitive to redox conditions that affects precursor availability. PhaC polymerizes (R)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA into PHA granules, with its activity influencing polymer characteristics based on kinetic parameters and substrate preferences of various PHA synthase classes. Environmental factors and regulatory proteins further modulate enzyme activity, while metabolic engineering strategies enhance PHA yield and tailor polymer composition, providing insights for optimizing biosynthesis and production potential.

In the current study, the bacterial strains were isolated, screened, and optimized. This bacterial strain was further checked by optimization of pH, temperature, carbon and nitrogen sources, and incubation time. In this study, the addition of different carbon sources was used in modified GTYN medium for the tailoring of monomer composites of PHA by PHA-producing isolates for green composite synthesis. The properties of PHA, such as biodegradability, non-toxicity, thermo-plasticity and biocompatibility, make it perfect for the substitution of synthetic polymers and can be used in biomedical and environmental applications47. The optimization of incubation time is a very important parameter for the commercial production of PHA. The influence of incubation time was studied by checking the PHA yield after every 12 h of incubation time, i.e., from 12 to 96 h. The PHA yield of modified GTYN medium was incubated for 96 h at 30 °C and 150 rpm in a shaking incubator. The PHA yields of different incubation times showed that the bacterial strains started to multiply in the medium after 12 h of incubation time, and this multiplication of strain increased in the medium as the incubation time increased48. The bacterial strains gave maximum PHA yield after 60 and 72 h of incubation time and then decreased with an increase in incubation time. It was reported in 2022 that the PHA production was carried out by using bacterial strain Alcaligenes latus in a medium having liquid bean curd waste as a low-cost carbon source. The reading of PHA production was taken after every 12 h of incubation time. It is studied that the bacterial strain A. latus began to grow and multiply in the medium after about 24 h of adaptation phase, and after 60 h of incubation time, the multiplication of the cell was decreased40. Singh et al. reported in 201149 that PHA production by using Bacillus sp. was done at different incubation times ranging from 24 to 120 h in optimized conditions. The decline in PHA yield after 72 h of incubation is a common trend in microbial PHA production, attributed to nutrient depletion, cell lysis, and cellular senescence. Nutrient depletion occurs when bacterial cultures consume available carbon and nitrogen sources, limiting growth and polymer synthesis. Cell lysis occurs when bacterial cells experience stress due to accumulation of metabolic byproducts, depletion of essential nutrients, or changes in the culture medium pH. This stress can lead to cell death or lysis, releasing intracellular PHA into the culture medium. Similar trends have been reported in other studies, such as Ralstonia eutropha, which also shows a decline in PHA yield beyond 72 h of incubation. To mitigate this decline, further optimization of incubation time, carbon source replenishment, or controlled fermentation conditions may be required.

The FTIR absorption bands of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHA) produced by bacterial isolates, including MA2, were analyzed and mapped to standard functional groups associated with polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) and polyhydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate (PHBV). Key absorption bands include O–H stretching (3278 cm⁻¹), C = O stretching (1723 cm⁻¹), C–H asymmetric stretching (2922–2923 cm⁻¹), C = C stretching (conjugated double bonds) (1634 cm⁻¹), and C–O stretching (ester linkage) (1231–1278 cm⁻¹), which are associated with the stretching vibrations of the hydroxyl (–OH) group, ester carbonyl (C = O) group, methylene (–CH₂) groups in the polymer backbone, conjugated carbon-carbon double bonds (C = C), and ester linkages. These bands confirm the polymer’s ester-based structure typical of PHB and PHBV. In the current study, the absorption bands were at 2962, 2950, 2850, 1720, 1412, 1375, 1257, and 1244 cm⁻¹, corresponding to CH and CH₂ anti-symmetric stretching, C = O and C-O stretching, CH₃ deformation vibration, and CH₃ symmetric bending. The C = O and C-O stretching are represented at 1722.8 and 1276 cm⁻¹50. Kathiraser et al. reported in 2007 that the FTIR spectrum of PHA produced had absorption bands at 1750 –1735 cm⁻¹ corresponding to carbonyl (C = O) stretch, and 1500 and 1000 cm⁻¹ corresponding to deformations of methyl and methylene groups. Bari et al. reported in 151 that the FTIR absorption spectrum showed at 1720 cm⁻¹ corresponded to the stretching of the C = O group compared to standard PHB52. The FTIR spectrum of EPS was compared with a previous report, revealing asymmetrical deformation of the C-H bond in CH2 groups at 1455.36 cm⁻¹ and 1453.67 cm⁻¹, equivalent for CH3 groups at 1372.55 cm⁻¹ and 1371.60 cm⁻¹, and asymmetric stretching of the aliphatic chain at 2914.13 cm⁻¹ to 2950.62 cm⁻¹, and C-C stretching at 1015.81 cm⁻¹ and 735.33 cm⁻¹32. The results of our study, FTIR spectra compared to the results of different other FTIR spectra, confirmed that absorption bands at 2962, 2950, 2850, 1720, 1412, 1375, 1257, and 1244 cm⁻¹ showed different functional groups of the polymer produced. Lopez-Cuellar et al. in 2011 reported on the FTIR spectrum of PHA produced and found that the principal bands were observed in the interval of 4000–650 cm− 153. In the FTIR spectrum of certain strains MB4 and MC3, the absence of the carbonyl (C = O) stretching peak between 1723 and 1740 cm⁻¹ may indicate a structural change in the kind of PHA generated or restrictions in polymer concentration or purity that impact spectral resolution. Medium-chain-length (mcl) or short-chain-length (scl) PHA esters are usually linked to the C = O peak; however, in mixed or co-polymeric PHAs, where the percentage of C = O groups is comparatively low or orientated differently, changes or the lack of this peak have been documented. On the other hand, peak intensity may drop below the detection threshold due to insufficient extraction or low PHA concentration in the sample. The FTIR absorption bands observed in this study are generally consistent with previous data for polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) and polyhydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate (PHBV). However, some discrepancies, such as the O–H stretching band at 3272–3280 cm⁻¹. This discrepancy could be due to the isolate-specific composition of the PHA produced by Rawalpindi soil isolates, which could influence the side-chain composition or polymer blend. The C–H asymmetric stretching band, typically observed between 2962 cm⁻¹ and 2853 cm⁻¹ in previous studies, may also exhibit variation depending on the specific carbon sources used for cultivation. The use of glucose and tryptone in this study could also contribute to a different composition of the produced PHA. Differences in experimental conditions, such as temperature, solvent use, and FTIR instrument calibration, could also contribute to variations in peak positions. Further studies comparing the PHA produced by these isolates with standard PHA compositions using more detailed compositional analysis, such as NMR, would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the structural characteristics of the polymer produced by these isolates50.

The ¹H Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectrum of the extracted biopolymer [Figure 4] confirmed the production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) [PHB-co-PHV], a copolymer comprising 3-hydroxybutyrate (3HB) and 3-hydroxyvalerate (3HV) monomers. The characteristic proton signals of 3HB were detected at δ = 1.28 ppm (methyl group, –CH₃), δ = 2.56 ppm (methylene group, –CH₂–), and δ = 5.25 ppm (methine proton, –CH–O–), while additional peaks at δ = 0.9 ppm, δ = 1.6–1.8 ppm, and δ = 2.4–2.6 ppm corresponded to the 3HV unit. These findings are consistent with previous studies by Doi et al. (1990) and Kahar et al. (2004), who reported similar chemical shifts for PHB-co-PHV copolymers synthesized by Cupriavidus necator and Alcaligenes eutrophus. The observed spectrum confirms the incorporation of 3HV monomers into the PHB backbone, which significantly influences the physicochemical properties of the polymer33.

The incorporation of 3HV units disrupts the crystallinity of PHB, resulting in a more flexible and less brittle polymer. Similar results were described by Sudesh et al. (2000), who demonstrated that increasing the valerate fraction enhances the polymer’s elongation at break and reduces its melting temperature (Tm). This modification improves the processability of PHB-co-PHV compared to pure PHB, making it more suitable for applications requiring elasticity and toughness, such as biomedical implants, tissue scaffolds, and biodegradable films54. Furthermore, PHB-co-PHV copolymers exhibit improved thermal stability and lower glass transition temperature (Tg), which facilitates their industrial processing and expands their application potential in packaging and controlled drug delivery systems55. The combination of structural confirmation and property enhancement observed here suggests that the bacterial isolate employed in this study possesses promising biosynthetic capabilities for producing high-quality PHB-co-PHV copolymers. Overall, the results agree with earlier literature, demonstrating that copolymerization of 3HB with 3HV leads to biopolymers with improved mechanical flexibility, biodegradability, and thermal performance, reinforcing their suitability as sustainable alternatives to conventional plastics55.

Conclusion

The study identifies and characterizes multiple bacterial strains capable of producing Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), a class of biodegradable and biocompatible biopolymers. Five potent PHA-producing isolates were selected based on their accumulation of intracellular PHA granules. Molecular identification revealed they belonged to diverse genera including Paenibacillus, Alcaligenes, Acinetobacter, and Bacillus. Optimization of physicochemical parameters improved growth and PHA yield. Optimal growth conditions were pH 7 and temperatures ranging from 35 °C to 40 °C. Glucose supported the highest biomass accumulation across all strains, while tryptone emerged as the most effective nitrogen source. The optimized incubation period of 72 h led to enhanced PHA accumulation, with yields ranging between 60% and 70% of cell dry weight for the most productive strains. The study demonstrates the successful optimization of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production in bacterial isolates from hydrocarbon-contaminated soils in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. The optimized physicochemical parameters, including pH, temperature, and nutrient sources, enhanced PHA accumulation. They produce predominantly PHB-type polymers, suitable for rigid biodegradable packaging and biomedical applications. These strains are valuable for eco-friendly and economically viable PHA production. The findings underscore the metabolic versatility and industrial potential of naturally occurring PHA-producing bacteria and highlight the importance of medium and process optimization in maximizing biopolymer yield.

Data availability

The data for the DNA sequences are accessible at the NCBI website with accession numbers and links as such: accession numbers [ON968691], [ON968709], [ON968725], [ON968695], and [ON968610]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/ON968610, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/ON968695, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/ON968725, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/ON968709, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/ON968691 Any other data can be obtained on a reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not Applicable.

References

Palmeiro-Sánchez, T., O’Flaherty, V. & Lens, P. N. L. Polyhydroxyalkanoate bio-production and its rise as biomaterial of the future. J. Biotechnol. 348, 10–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2022.03.001 (2022).

Shah, T. A. et al. Whole cell of pure Clostridium Butyricum CBT-1 from anaerobic bioreactor effectively hydrolyzes agro-food waste into biohydrogen. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-22443-9 (2022).

Shah, T. A., Li, Z., Li, Z. & Zhang, A. Energy status, anaerobic digestion and role of genetic and metabolic engineering for hydrogen and methane. J. Water Process. Eng. 69, 106725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.106725 (2025).

Shah, A. & others Bacillus sp. strains to produce bio-hydrogen from the organic fraction of municipal solid waste. Appl. Energy. 176, 116–124 (2016).

Fayyazbakhsh, A., Hajinajaf, N. & others Bakhtiari, H. Eco-friendly additives for biodegradable polyesters: recent progress in performance optimization and environmental impact reduction. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 44 https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SUSMAT.2025.E01395 (2025).

Liu, Y., Li, G. R. & Guo, F. F. others Large-scale production of magnetosomes by chemostat culture of Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense at high cell density. Microb Cell Fact 9:1–8. (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-9-99

Tan, G. Y. A., Chen, C. L. & Li, L. others Start a research on biopolymer polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA): A review. Polym Basel 6:706–754. (2014). https://doi.org/10.3390/polym6030706

Thamarai, P., Vickram, A. S. & others Saravanan, A. Recent advancements in biosynthesis, industrial production, and environmental applications of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs): A review. Bioresour Technol. Rep. 27, 101957. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BITEB.2024.101957 (2024).

Malashin, I., Martysyuk, D., Tynchenko, V. & others Machine Learning-Based process optimization in biopolymer manufacturing: A review. Polym. Basel. 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/POLYM16233368 (2024).

Qie, Z., Sivashankari, R. M., Miyahara, Y. & Tsuge, T. Biosynthesis and property evaluation of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-2-hydroxyalkanoate) containing 2-hydroxy-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate unit. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 236 https://doi.org/10.1016/J.POLYMDEGRADSTAB.2025.111277 (2025).

Bassas Galià, M. Isolation and analysis of storage compounds. In: Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 3725–3741 (2010).

Getino, L., Martín, J. L. & Chamizo-Ampudia, A. A Review of Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Characterization, Production, and Application from Waste. Microorganisms 12:2028. (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/MICROORGANISMS12102028

López-Cuellar, M. D. R., Alba-Flores, J., Gracida-Rodríguez, J. & Pérez-Guevara, F. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) with Canola oil as carbon source. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 48, 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2010.09.016 (2010).

Galego, N., Rozsa, C. & Sánchez, R. others Characterization and application of poly(β-hydroxyalkanoates) family as composite biomaterials. Polym Test 19:485–492. (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0142-9418(99)00011-2

Sachan, R. S. K., Devgon, I., Karnwal, A. & Mahmoud, A. E. D. Valorization of sugar extracted from wheat straw for eco-friendly polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production by Bacillus megaterium MTCC 453. Bioresour Technol. Rep. 25 https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BITEB.2024.101770 (2024).

Surendran, A., Lakshmanan, M. & Chee, J. Y. others Can polyhydroxyalkanoates be produced efficiently from waste plant and animal oils? Front Bioeng Biotechnol 8:. (2020). https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2020.00169

Ichiro Matsumoto, K., Brigham, C. J. & Gross, R. A. others Can polyhydroxyalkanoates be produced efficiently from waste plant and animal Oils? Front Bioeng Biotechnol 1:169. (2020). https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2020.00169

Muneer, F., Rasul, I., Azeem, F. & others Microbial polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs): efficient replacement of synthetic polymers. J. Polym. Env. 28, 2301–2323. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10924-020-01772-1 (2020).

Hoşafcı, E., Ateş, C., Volkan, A. E. & others Effect of pH and salinity on photofermentative hydrogen and poly-hydroxybutyric acid production via rhodobacter capsulatus YO3. Int. J. Hydrog Energy. 118, 331–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHYDENE.2025.03.198 (2025).

Martínez-Herrera, R. E., González-Meza, G. M. & Meléndez-Sánchez, E. R. Toward sustainable bioplastics: the potential of algal biomass in PHA production and biocomposites fabrication. Process. Biochem. 150, 276–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PROCBIO.2025.01.019 (2025).

Brouchon, G., Alvarez, P. & others Six, A. Biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHBHV) using microalgae-derived starch and levulinic acid. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 233 https://doi.org/10.1016/J.POLYMDEGRADSTAB.2025.111176 (2025).

Hadri, S. H., Tareen, N. & others Hassan, A. Alternatives to conventional plastics: polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) from microbial sources and recent approaches – A review. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 195, 106809. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSEP.2025.106809 (2025).

Li, D., Wang, F., Zheng, X. & others Lignocellulosic biomass as promising substrate for polyhydroxyalkanoate production: advances and perspectives. Biotechnol. Adv. 79, 108512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2024 (2025).

Ladhari, S., Vu, N. N. & Boisvert, C. others Recent development of polyhydroxyalkanoates (pha)-based materials for antibacterial applications: A Review. ACS Appl Bio Mater 6:1398–1430. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/ACSABM.3C00078

Masood, F., Abdul-Salam, M., Yasin, T. & Hameed, A. Effect of glucose and olive oil as potential carbon sources on production of PHAs copolymer and tercopolymer by Bacillus cereus FA11. 3 Biotech 7:87. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-017-0712-y

Masood, F., Hasan, F., Ahmed, S. & Hameed, A. Biosynthesis and characterization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) from Bacillus cereus FA11 isolated from TNT-contaminated soil. Ann. Microbiol. 62, 1377–1384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13213-011-0386-3 (2012).

Ghosh, J. S. & Otari, S. Production and characterization of the polymer polyhydroxy Butyrate-co-polyhydroxy valerate by Bacillus megaterium NCIM 2475. Curr. Res. J. Biol. Sci. 1, 23–26 (2009). https://doi.org/maxwellsci/crjbs/(2)23-26

Cycil, L. M., DasSarma, S. & Pecher, W. others Metagenomic Insights Into the Diversity of Halophilic Microorganisms Indigenous to the Karak Salt Mine, Pakistan. Front Microbiol 11:1567. (2020). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01567

Shah, T. A. et al. Bacteriological analysis of Siran river system for fecal contamination and Metallo-β-Lactamase blaNDM-l gene. Pak J. Zool. 46: (2014).

Leena, M. C., Aamer, A. S., Abdul, H. & Fariha, H. Physiological, biochemical and phylogenetic characterization of extremely halophilic bacteria isolated from Khewra mine, Pakistan. Appl. Ecol. Env Res. 16, 1243–1256. https://doi.org/10.15666/aeer/1602_12431256 (2018).

Jha, A. & Kumar, A. Biobased technologies for the efficient extraction of biopolymers from waste biomass. Bioprocess. Biosyst Eng. 42, 1893–1901. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00449-019-02199-2 (2019).

Kinyanjui Muiruri, J., Chee Chuan Yeo, J. & Yun Debbie Soo, X. others Recent advances of sustainable Short-chain length polyhydroxyalkanoates (Scl-PHAs) – Plant biomass composites. Eur Polym J 187:111882. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EURPOLYMJ.2023.111882

Dienye, B. N., Agwa, O. K. & Abu, G. O. Molecular Characterization, optimization and production of PHA by Indigenous bacteria using alternative nutrient sources as substrate. Microbiol. Res. J. Int. 12–26. https://doi.org/10.9734/MRJI/2022/V32I111352 (2022).

Salam, M. A., Khan, A. & Rafiq, M. others Isolation of magnetotactic bacteria from environmental samples and optimization and characterization of extracted magnetosomes. Appl Ecol Env Res 17:5355–5367. (2019). https://doi.org/10.15666/aeer/1703_53555367

Akinmulewo, A. B. & Nwinyi, O. C. Polyhydroxyalkanoate: a biodegradable polymer (a mini review). J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1378, 042007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1378/4/042007 (2019).

Nizamuddin, S., Baloch, A. J., Chen, C. & others Bio-based plastics, biodegradable plastics, and compostable plastics: biodegradation mechanism, biodegradability standards and environmental stratagem. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 195, 105887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2024.105887 (2024).

Meereboer, K. W., Misra, M. & Mohanty, A. K. Review of recent advances in the biodegradability of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) bioplastics and their composites. Green. Chem. 22, 5519–5558. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0GC01647K (2020).

PiechaCR, AlvesTC, ZaniniML de O & others. Application of the solid-state fermentation process and its variations in PHA production: a review. Arch. Microbiol. 205 (4). https://doi.org/10.1007/S00203-022-03336-4 (2023).

Anburajan, P., Naresh Kumar, A. & Sabapathy, P. C. others Polyhydroxy butyrate production by Acinetobacter junii BP25, Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC 7966, and their co-culture using a feast and famine strategy. Bioresour Technol 293:122062. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122062

Sun, Z., Ramsay, J. A., Guay, M. & Ramsay, B. A. Fermentation process development for the production of medium-chain-length poly-3-hyroxyalkanoates. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 75, 475–485 (2007).

Che, L., Jin, W. & Zhou, X. others Current status and future perspectives on the biological production of polyhydroxyalkanoates. Asia-Pac J Chem Eng 18:. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/APJ.2899

Hong, Y., Ma, Y., Wu, L. & others Characterization and analysis of NifH genes from Paenibacillus sabinae T27. Microbiol. Res. 167, 596–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2012.05.003 (2012).

Jadoon, A., farooq, H. & ambreen, A. others Isolation and Identification of Potentially Pathogenic Bacteria from Second Hand Items of Flea Market of District Haripur, Pakistan. Turk J Physiother Rehabil 9:1–10 (2022).

Basharat, Z., Yasmin, A., He, T. & Tong, Y. Genome sequencing and analysis of Alcaligenes faecalis subsp. Phenolicus MB207. Sci. Rep. 8, 3616. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21919-4 (2018).

Hungund, B., Shyama, V. S., Patwardhan, P. & Saleh, A. M. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoate from Paenibacillus durus BV-1 isolated from oil mill soil. J. Microb. Biochem. Technol. 5, 13–17. https://doi.org/10.4172/1948-5948.1000092 (2013).

Farhan Zafar Chudhary, M., ur Rehman, S. & Rubab Kazmi, M. others Isolation and Characterization of Oil Degrading Bacteria from Soil Contaminated with Used Petroleum Products. Tob Regul Sci 8:335–343. (2022). https://doi.org/10.18001/TRS.8.1.31

Nasir, A., Masood, F., Yasin, T. & Hameed, A. Progress in polymeric nanocomposite membranes for wastewater treatment: Preparation, properties and applications. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 79, 29–40. https://doi.org/10.4172/1948-5948.1003476 (2019).

Satoh, K., Kawakami, T. & others Isobe, N. Versatile aliphatic polyester biosynthesis system for producing random and block copolymers composed of 2-, 3-, 4-, 5-, and 6-hydroxyalkanoates using the sequence-regulating polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase PhaCAR. Microb. Cell. Fact. 21, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-022-01811-7 (2022).

Singhaboot, P. & Kaewkannetra, P. A higher in value biopolymer product of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) synthesized by Alcaligenes latus in batch/repeated batch fermentation processes of sugar cane juice. Ann. Microbiol. 65, 2081–2089. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13213-015-1046-9 (2015).

Mahmoud, M. B. Biosynthesis of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) biopolymer by Bacillus megaterium SW1-2: application of Box-Behnken design for optimization of process parameters. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 6, 11. https://doi.org/10.5897/ajmr11.1382 (2012).

Baria, D. M., Dodiya, K. R. & others Shaikh, J. A. Isolation, screening and quantifying of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) using FTIR analysis. J. Microb. Biochem. Technol. 5, 13–17. https://doi.org/10.4172/1948-5948.1000092 (2023).

Siddharth, B. R. Isolation of plastic degrading bacteria. Int. J. Basic. Appl. Biol. 3: (2019).

Vu, D. H., Wainaina, S., Taherzadeh, M. J. & others Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) by Bacillus megaterium using food waste acidogenic fermentation-derived volatile fatty acids. Bioengineered 12, 2480–2498. https://doi.org/10.1080/21655979.2021.1935524 (2021).

Raza, Z. A., Abid, S. & Banat, I. M. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Characteristics, production, recent developments and applications. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 126, 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IBIOD.2017.10.001 (2018).

Misra, S. K., Ansari, T. & others Mohn, D. Effect of nanoparticulate bioactive glass particles on bioactivity and cytocompatibility of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) composites. J. R Soc. Interface. 7, 453–465. https://doi.org/10.1098/RSIF.2009.0255 (2010).

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, for funding the publication of this work (Grant KFU 254162).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAS, AH, U did writing—original draft, conceptualization, analysis, and investigation; MAS, AB: review & editing; MAS, AB revised the manuscript, review and did final validation; ZI: review, resources & editing; ZI funding and resources. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Not Applicable.

Consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salam, M.A., Hussain, A., Uzma et al. Isolation of high yield polyhydroxyalkanoate producing bacteria from contaminated soils and biopolymer characterization. Sci Rep 15, 45193 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29352-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29352-0