Abstract

In this study, the effects of nonlinear thermal radiation, Arrhenius activation energy, and chemical reactions on the flow and heat transfer of a water-based hybrid nanofluid containing SWCNT- \(TiO_{2}\) & MWCNT- \(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) nanoparticles over a rotating disk are examined. The investigation highlights the combined influence of nonlinear radiation and nanoparticle shape factors on the transport properties of the hybrid fluid. Given that the thermal and structural performance of nanomaterials is strongly dependent on their morphology, special attention is devoted to assessing the role of particle shape variations. The objective of this work is to advance the fundamental understanding of how nonlinear radiative processes, activation energy, and nanoparticle geometry interact in rotating disk flows, thereby contributing to the development of efficient nanofluid based thermal management systems. These materials find applications in energy storage, thermal stability, transistors, and electromagnetic shielding. Given the growing demand for nanotechnology, understanding these effects is crucial for enhancing performance in engineering and energy systems. The governing PDEs are simplified into dimensionless ODEs using similarity transformations. The Successive Over-Relaxation method, executed through a custom MATLAB code, is used to obtain the solutions of these equations. The effects of different parameter values on radial and transversal velocity, as well as heat and mass transfer, are examined using graphical analysis. In addition, tabular data are presented to evaluate the behavior of skin friction, Nusselt number, and Sherwood number under various parametric conditions. The results reveal that velocity diminishes with increasing magnetic parameter values, whereas nonlinear radiation enhances heat transfer. Activation energy augments both concentration and mass transfer, although the latter is influenced by the Schmidt number and the chemical reaction rate. Conversely, temperature decreases with a rise in the Prandtl number. Radial skin friction decreases by about 44% as the magnetic parameter increases, while tangential skin friction magnitude rises by nearly 78% at low suction and around 37% at high suction. Furthermore, the heat transfer rate improves from 25.27% at Rd = 0.5 to 37.18% at Rd = 1.4, indicating an overall enhancement of 11.91%. These outcomes hold practical significance for optimizing fluid behavior and heat transfer in rotating systems, with potential applications in energy systems, heat exchangers, and advanced cooling technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The study of fluid flow over rotating disks has gained considerable attention due to its broad industrial applications, including computer disk manufacturing, crystal growth, rotating viscometers, and various rotating machinery systems. It also serves as a useful model for analyzing cooling processes in rotating disks, where nanofluids are often employed as coolants to enhance heat transfer. The fluid characteristics in these systems play a crucial role in determining surface shear stress and heat transfer rates, which in turn influence the cooling process and ultimately the mechanical properties of the disk surface.

The classical rotating disk problem was originally investigated by Von Kármán1, who simplified the steady-state Navier–Stokes equations into a set of ordinary differential equations and solved them using an approximate integral technique. Later, researchers such as W. G. Cochran2, Benton3, and Rogers and Lance4 extended this analysis to impulsively started flows. Edrogan5 advanced the study further by exploring unsteady flows caused by non-coaxial rotation between the disk and the surrounding fluid at infinity. More recently, Sheikholeslami et al.6 focused on nanofluid flow and heat transfer over rotating disks, while Turkyilmazoglu7 examined the influence of magnetic fields in this context. Industrial heat transfer applications have long driven researchers to explore methods for enhancing the efficiency of working fluids. In many machines and thermal systems, conventional coolants such as water, ethylene glycol, and oil are commonly employed due to their availability and stability. However, these fluids inherently possess limitations, particularly in terms of thermal conductivity and operating temperature range, which restrict their effectiveness in high-performance applications. To overcome these drawbacks, engineers and scientists have explored the suspension of solid nanoscale particles within base fluids, thereby improving their thermophysical properties. This concept, first introduced by Choi and Eastman8, led to the development of nanofluids fluids with significantly enhanced heat transfer capabilities. Building upon this idea, researchers have more recently introduced hybrid nanofluids, created by dispersing two or more distinct types of nanoparticles into a single base liquid. This innovation combines the individual benefits of each nanoparticle type, enabling superior thermal conductivity, improved stability, and higher heat transfer rates compared to conventional nanofluids, thereby meeting the increasingly demanding requirements of modern industrial processes.

Compared to conventional heat transfer fluids, nanofluids offer superior thermal performance owing to their high aspect ratio and enhanced thermal conductivity. These fluids are produced by dispersing nanoscale solid particles within a base fluid, thereby significantly improving its thermal properties. A more advanced class, known as hybrid nanofluids, is formulated by suspending two different types of nanoparticles—typically a combination of metallic nanoparticles (e.g., Ag, Al, Cu, Si, Au, Ni) and metal oxides (e.g., ZnO, TiO₂, WO₃, ZrO₂, CeO₂, SnO₂)—each with a size below 100 nm, in a base liquid. This dual-component approach synergistically boosts thermal conductivity and other thermophysical characteristics, surpassing both conventional fluids and standard nanofluids. Owing to these enhanced properties, hybrid nanofluids have found applications across diverse sectors, including heat pipes, solar energy systems, cooling and heating processes, HVAC systems, machining and manufacturing coolants, biomedical devices, aerospace and spacecraft thermal management, as well as military technologies. Nihal et al.9,10,11 investigates nanofluid flows in different configurations, including Darcy–Forchheimer porous media with gyrotactic microorganisms, hybrid Fe₃O₄ & CoFe₂O₄ nanofluid in cone and disk geometry, and hybrid Casson nanofluid over porous stretching surfaces. Governing PDEs are reduced to ODEs and solved using RKF-45 and ANN techniques. Results show that wall stretching, activation energy, and heat source/sink significantly influence velocity, heat, and mass transfer, while ANN predictions align well with numerical outcomes, indicating potential applications in efficient thermal and biomedical systems.

Ahmad et al.12 examined the thermal behavior of mixed nanofluids containing \(Ni\,Zn\,Fe_{2} \,O_{4}\) and \(Mn\,Zn\,Fe_{2} \,O_{4}\), Muhammad and Nadeem13 analyzed the influence of \(Fe_{2} \,O_{4}\), \(Ni\,Zn\,Fe_{2} \,O_{4}\), \(Mn\,Zn\,Fe_{2} \,O_{4}\) on ferromagnetic nanofluids, while Zhao et al.14 compared ferromagnetic hybrid nanofluids under velocity slip and convective conditions. Firew et al.15 assessed the performance and emissions of a CI engine fueled with ethanol–diesel emulsions containing \(Ni\,Zn\,Fe_{2} \,O_{4}\) nanoparticles. Noor and Mukhtar16 studied heat transfer in \(Mg\,Zn_{6} Zr\,\)–engine oil mixtures, and Maraj and Shaiq17 investigated rotational effects of \(Fe_{2} \,O_{4}\),\(Ni\,Zn\,Fe_{2} \,O_{4}\),and \(Mn\,Zn\,Fe_{2} \,O_{4}\) nanoparticles in \(C_{2} H_{6} O_{2}\) between two stretchable discs. Sachhin et al.18 investigated Bi-viscous Bingham hybrid nanofluid flow with Brinkman number and variable MHD effects, modeled via similarity transformations and solved numerically. Findings reveal reduced velocity with higher inverse Darcy numbers and enhanced temperature under thermal radiation, with applications in engineering and biomedical systems. Bhashkar et al.19 studies unsteady MHD tangent hyperbolic hybrid nanofluid flow with Darcy Forchheimer, thermophoresis, Brownian motion, and activation energy effects. Results show rising concentration/temperature, while higher MHD and porosity reduce velocity.

Nonlinear thermal radiation is incorporated in mathematical models to more accurately capture heat transfer when temperature differences are large, where the linear approximation becomes insufficient. Unlike the simplified linear approach, the nonlinear form accounts for the fourth-power temperature dependence from the Stefan Boltzmann law, making it more realistic for high-temperature applications. This improves prediction accuracy in processes such as solar energy systems, re-entry aerodynamics, and high temperature manufacturing. Its key role lies in capturing the true radiative heat exchange between surfaces and fluids, enabling better design, optimization, and control of thermal systems under extreme conditions. Owing to its significance, numerous studies20,21,22,23,24,25 have addressed thermal radiation effects, although many have relied on the simplified linear Rosseland formulation.

The magnetic field significantly influences the behavior of electrically conducting fluids by altering boundary layer motion through ionization effects. Strong electromagnetic fields in low-density ionized liquids reduce electrical conduction, while induced currents arise from the spiraling of free ions, affecting both electric and magnetic fields. Such magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) phenomena are critical in applications ranging from motors and gears to geophysical flows and chemical processing. Zainal et al.26 explored magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) water-based hybrid nanofluid flow over a porous stretched/shrunk surface with quadratic velocity. Patil et al.27 investigated the behavior of MHD Prandtl nano liquid flow over a stretching surface under convective boundary conditions. Elayarani et al.28 developed a model for bioconvective Carreau nanofluid containing microorganisms over a thin stretching sheet, incorporating magnetic wave effects and multiple slip conditions. Bhaskar et al.29,30,31 investigates hybrid nanofluid flows in porous media under electromagnetic and Darcy Forchheimer effects, considering heat absorption, viscous dissipation, chemical reactions, and diffusion phenomena. Various nanofluids (water based, blood based, and methanol based with metallic nanoparticles) are analyzed using similarity transformations and solved with MATLAB’s bvp4c solver. Results highlight the influence of buoyancy, slip, radiation, and activation energy on velocity, temperature, and concentration, with applications in biomedical engineering, environmental management, and industrial heat transfer systems. Sabu et al.32 examined ferro-nanofluid MHD convection in an inclined tube by considering Hall current, internal heat generation, and the Soret effect. Saqib et al.33 focused on hybrid ferro-nanofluid MHD flow in the presence of thermal radiation, heat generation, and nanoparticle structural influences. Almakki et al.34 analyzed entropy generation in micropolar nanofluid MHD flow over an overstretched sheet, whereas Yasmin et al.35 applied the Brinkman model to study MHD Casson nanofluid transport in a square cavity with a spatially varying heat source.

In 1889, Nobel laureate S. Arrhenius introduced the Arrhenius equation, which establishes the relationship between temperature and reaction rate and identifies the minimum energy required to initiate a chemical reaction, known as the activation energy (AE). AE is fundamental to various processes such as electron transfer, liquid-phase polymerization, solid desorption, and solid-state decomposition. Madhukesh et al.36 investigated the chemically reactive stretched flow of a non-liquid medium induced by a rotating disk, while Reddy et al.37 studied hybrid nanofluid MHD flow, emphasizing the influence of chemical reactions involving AE on mass transport. R. N. Kumar et al.38 explored the effect of dual nanoparticle suspensions in Casson liquid flow over a rotating disk with AE. Madhukesh et al.39,40 investigated various liquid flows incorporating AE, emphasizing its influence on mass transport. A numerical investigation of steady MHD micropolar fluid flow over an inclined surface was carried out by Ahmad et al.41 employing the SOR method and considering chemical reaction, Brownian motion, thermophoresis, and viscous dissipation. The study provides valuable insights for industrial heat and mass transfer applications such as magnetic material processing and molten metal purification.

K. Ali et al.42,43,44 analyzed EMHD and Casson fluid flows under slip conditions in microchannels, disks, and porous channels. Their studies highlight the influence of Reynolds and Hartmann numbers, disk motion, permeability, and slip on velocity and trapping behavior, while thermophoresis reduces and Brownian motion enhances temperature and concentration profiles. Recently, extensive studies have been conducted on nanofluid and hybrid nanofluid models to enhance heat and mass transfer performance in porous and non-porous media under various geometrical configurations45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55.

Building on previous investigations of hybrid nanofluids56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67, this study explores the unexplored combined effects of nonlinear thermal radiation, Arrhenius activation energy, chemical reactions, and nanoparticle shape factors in a rotating disk system. The work not only extends theoretical modeling but also provides insights relevant to advanced thermal management, energy conversion, and industrial fluid engineering applications. Table 1 presents the research gap or comparison of previous studies vs. present work. Table 2 outlines the thermophysical properties of the base fluid and nanoparticles, while Table 3 illustrates their correlation in the formation of the hybrid nanofluid. The shape factors of the nanoparticles are provided in Table 4.

Practical importance of the SWCNT-TiO 2 & MWCNT-C O Fe 2 O 4 configuration.

Thermal Management in Engineering Systems: SWCNTs and MWCNTs provide exceptional thermal conductivity and anisotropic heat transport, making them excellent heat-transfer enhancers. \(TiO_{2}\) improves chemical stability and acts as a photocatalyst, important in high-temperature and radiation-assisted thermal systems. \(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) is magnetic and electrically conductive, enabling tunable thermal and flow properties under electromagnetic fields. Combined, this tetra-hybrid suspension is highly effective for cooling rotating machinery, disk brakes, turbines, and nuclear reactor components where nonlinear radiation and strong shear environments are present.

Energy Conversion and Catalysis: The inclusion of Arrhenius activation energy reflects realistic temperature-dependent chemical kinetics, which are critical in catalytic reactors, fuel reformers, and polymerization processes. CNT supported \(TiO_{2}\) composites are widely used in photocatalytic hydrogen production, while MWCNT–\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) composites are useful for electrochemical energy storage and fuel cell electrodes.

Biomedical Relevance: \(TiO_{2}\) nanoparticles are biocompatible and used in drug delivery and biosensing.\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) nanoparticles are magnetic, enabling magnetic hyperthermia cancer treatment, MRI contrast enhancement, and targeted drug delivery. CNT-based composites improve drug loading capacity and controlled release. Modeling such fluids with radiation and activation energy mimics real biomedical conditions (e.g., laser-induced hyperthermia, enzyme-catalyzed drug release, localized heating for tumor therapy).

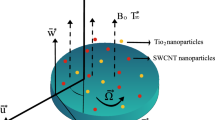

Multifunctionality and Control: The combination of high-conductivity CNTs, semiconducting \(TiO_{2}\), and magnetic \(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) produces a multifunctional fluid that can be externally controlled via heat, light, or magnetic fields. This flexibility is crucial for next-generation smart fluids in energy, aerospace, and biomedical applications. This configuration is practically important because it unites thermal management, catalytic reactivity, magnetic tunability, and biomedical compatibility into one suspension. Incorporating nonlinear radiation and Arrhenius activation energy ensures that the mathematical model realistically captures the conditions encountered in high-temperature engineering systems and biomedical treatments involving radiation or thermally activated reactions. The conceptual framework of the hybrid nanofluid system is illustrated in Fig. 1(a).

Novelty and research gap

Although several studies have analyzed hybrid nanofluid flows over rotating disks, the present work is distinct in terms of both the mathematical treatment and the physical modeling. First, unlike most existing studies20,35,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67 that employ standard numerical solvers (e.g., Runge–Kutta shooting, bvp4c), this study applies the Successive Over-Relaxation (SOR) method, which is rarely used for such highly nonlinear boundary layer formulations. The SOR scheme provides improved numerical stability and convergence for stiff nonlinear systems, ensuring accurate resolution of near wall gradients. Second, the model incorporates nonlinear thermal radiation, a more realistic representation compared to the frequently used linear Rosseland approximation. This extension captures stronger radiative heat transfer effects at higher temperature differences, making the analysis more applicable to high temperature rotating systems. Third, the inclusion of Arrhenius activation energy introduces a chemically reactive transport mechanism, which has received limited attention in the context of hybrid nanofluid flow over rotating disks. By accounting for the sensitivity of reaction rates to temperature, the model becomes relevant for catalytic reactors, polymer processing, and biochemical applications. Finally, the consideration of the nanoparticle shape factor adds another dimension of novelty. While many studies assume spherical nanoparticles65, this work explicitly evaluates how anisotropic particle geometries alter the effective thermophysical properties, thereby influencing velocity, temperature, and concentration fields. Together, these aspects establish the novelty of the present research: a comprehensive, multi-physics model solved with an unconventional but efficient numerical approach, providing insights not addressed in prior hybrid nanofluid rotating disk studies.

Research questions

To accomplish the aim of this research, the study seeks to answer the following questions:

-

How to model nonlinear thermal behavior of hybrid nanofluids with Arrhenius reactivity?

-

What are the key thermal transport traits in rotating disk flows?

-

How do activation energy and chemical reactions affect thermal and concentration layers?

-

How does the SOR method compare with conventional solvers for nonlinear flow equations?

-

What is the effect of relaxation parameter \(\left( \omega \right)\) on SOR convergence and stability?

-

How do nanoparticle composition and nonlinearities influence heat transfer?

-

How do activation energy, Schmidt number, and reaction rates shape concentration profiles?

Thermophysical properties of nanofluid and nanoparticles

Thermal conductivity (T.C) strongly affects hybrid nanofluid heat transfer and depends on volume fraction, temperature, material, and particle geometry. In 1881, the Maxwell model originally developed to dilute suspensions of micro-particles, is still used for comparison due to its simplicity, though it ignores particle shape. Beyond doubt, this correlation is precise for globe-shaped and a low quantity of nanoparticles. The Maxwell correlation for T.C is \(\frac{{k_{nf} }}{{k_{bf} }} = \frac{{k_{np} + 2k_{bf} - 2\phi_{1} (k_{bf} - k_{np} )}}{{k_{np} + 2k_{bf} + \phi_{1} (k_{bf} - k_{np} )}},\) in which \(k_{bf}\) represents the T.C of the base fluid, \(k_{np}\) represents the T.C of nanoparticles and \(k_{nf}\) represent the T.C of nanofluid. Later, Hamilton and Crosser54,55 extended this model in 1962, \(\frac{{k_{nf} }}{{k_{bf} }} = \frac{{k_{np} + (n - 1)k_{bf} - (n - 1)\phi_{1} (k_{bf} - k_{np} )}}{{k_{np} + (n - 1)k_{bf} + \phi_{1} (k_{bf} - k_{np} )}},\) by introducing a shape factor n, (e.g., n = 3 for spheres, n = 3.7 for brick, n = 4.9 for cylinder, n = 5.7 for platelets), making it more applicable to nanofluids with diverse particle shapes, especially in biomedical applications66. In the above equation, \(n = \frac{3}{\psi }\) where ψ is sphericity. In the case of spherical nanoparticles, the shape factor takes values of ψ = 1 or n = 3, whereas for cylindrical nanoparticles, it is ψ = 0.62 or n = 4.9 (The shape factors of the nanoparticles are provided in Table 2). A wide range of theoretical investigations has been carried out to develop reliable models for predicting the effective viscosity and thermal conductivity of nanofluids. The effective electrical conductivity (E.C) for nano fluid (followed as in Maxwell model) is \(\frac{{\sigma_{nf} }}{{\sigma_{bf} }} = 1 + \frac{3(\sigma - 1)\phi }{{(\sigma + 2) + (\sigma - 1)\phi }},\,\,\,where\,\,\,\,\sigma = \frac{{\sigma_{s} }}{{\sigma_{bf} }}.\) Here \(\sigma_{bf}\),\(\sigma_{s}\) are the E.C of the base fluid and the solid nanoparticles.

Representation of hybrid and tetra hybrid nanofluid configurations

In the present work, two nanoparticle composites are considered: SWCNT \(TiO_{2}\)–MWCNT \(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\). Each of these combinations consists of two different nanoparticles and therefore can independently be regarded as a hybrid nanofluid when dispersed in water. However, in much of the nanofluid literature, such composite systems are often described more generally under the umbrella term nanofluid, since the hybrid pair is treated as a single effective nanoparticle type with its own thermophysical properties. For example, \(TiO_{2}\) nanoparticles may be decorated or attached on the surface of SWCNTs, forming one composite particle, while \(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) nanoparticles may cluster around MWCNTs, forming another. Accordingly, when both composites (SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\) & MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\)) are simultaneously suspended in the base fluid, the system may be viewed in two equivalent ways:

-

1.

As a nanofluid with two distinct nanoparticle species (the two composites), following the conventional terminology.

-

2.

As a tetra-hybrid nanofluid, since the suspension effectively contains four different nanoparticles (SWCNT, \(TiO_{2}\), MWCNT, and \(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\)).

For clarity and consistency, the current study adopts the first convention, referring to the suspension as a nanofluid while noting that it also qualifies as a tetra hybrid nanofluid in the more specific classification. (please see Fig. 1(b)).

The microstructural behavior of the prepared suspension can be visualized in Fig. 1(c), which compares two possible configurations of the SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\) & MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) system. In the first case, a homogeneous tetra-hybrid nanofluid is obtained, where all four nanoparticles remain distinct and uniformly dispersed within the base fluid. This structure ensures that the thermo-physical enhancements arise from the additive contributions of each nanoparticle type, leading to balanced improvements in thermal conductivity, Brownian motion effects, and suspension stability. In contrast, the second case illustrates a heterogeneous or composite nanofluid, where oxide nanoparticles (\(TiO_{2}\) and \(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\)) preferentially attach to the surfaces of carbon nanotubes. This interaction results in the formation of CNT–oxide composite clusters, increasing the effective particle size and promoting network like structures within the fluid. Such clustering can enhance thermal conductivity through percolation pathways but may also increase viscosity and sedimentation tendency, thereby influencing flow resistance. Hence, the classification of the system as a true tetra-hybrid nanofluid or a composite nanofluid depends strongly on the degree of nanoparticle interaction, which in turn is governed by preparation methods, surfactant choice, and surface functionalization.

Modeling formulation

In this communication, we investigate the key role of nonlinear thermal radiation in hybrid nanofluid flow driven by a rotating disk. Hybrid nanofluid consists of nanoparticles SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\) & MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4}\), with water \((H_{2} O)\) as a base liquid.

The following are the assumptions for the present flow configuration25,56,58,62,65,67.

-

This investigation encompasses nonlinear thermal radiation, viscous dissipation, chemical reaction, and Arrhenius activation energy.

-

Disk is rotating with an angular velocity \(\Omega\) about \(z = 0.\)

-

The velocity field consists of components in the radial, azimuthal, and axial directions, respectively.

-

\(B_{0}\) is the strength of Magnetic field (MF), exerted normal to the disk plane.

-

Since the magnetic Reynolds number is negligible, the magnetic field can be disregarded. The nanofluid is assumed to be incompressible with constant thermophysical properties, which is valid for low-Mach-number flows \(\left( {M < < 1} \right)\) and moderate temperature variations \(\left( {\Delta T/T_{\infty } < 0.1} \right)\). The magnetic Reynolds number is considered negligible \(\left( {Rm < < 1} \right)\), allowing induced magnetic fields to be ignored, a condition typically satisfied in liquid–metal and nanofluid flows with moderate electrical conductivity. These assumptions are consistent with established studies and clearly define the validity range of the present model.

-

Radioactive heat flux for nonlinear thermal radiation \(- \frac{{4\sigma^{*} }}{{3k^{*} }}\left( {\frac{{\partial T^{4} }}{\partial z}} \right)\) is regarded.

-

Moreover, Arrhenius activation energy \(- \frac{{E_{a} }}{KT}\) along with chemical reaction \(K_{cr}^{*} (C - C_{\infty } )\) is also incorporated.

-

Furthermore,\(\theta (\zeta ,\eta )\left( {T_{w} - T} \right) = T - T_{\infty } \,\,\) and \(\chi (\zeta ,\eta )\left( {C_{w} - C_{\infty } } \right) = C - C_{\infty } \,\,\) represents the surface temperature and concentration.

-

Physical representation of the current model can be seen in Fig. 1(d).

The hybrid nanofluid model is described by the following governing Eqs25,56,58,62,65,67.:

associated boundary conditions

The continuity Eq. (1) ensuring mass conservation in an incompressible flow using cylindrical coordinates. It connects velocity components and reflects radial, geometric, and axial variations in flow. The radial momentum Eq. (2) accounts for convection, pressure gradients, viscous effects, and magnetic forces in the radial direction. It plays a key role in modeling flow behavior under magnetic fields in hybrid nanofluids. The tangential momentum Eq. (3) governs the rotational behavior of the fluid. It includes convective transport, viscous effects, and magnetic damping relevant to rotating disk systems. The axial momentum Eq. (4) captures vertical fluid movement influenced by rotation and boundary conditions. It includes terms for convection, pressure gradient, and viscosity in both radial and axial directions. The energy balance Eq. (5) models heat transfer by considering convection, conduction, viscous dissipation, and nonlinear thermal radiation. It’s essential for understanding heat behavior in thermally active nanofluids. The species concentration Eq. (6) explains how chemical species spread due to convection, diffusion, and temperature-sensitive reactions. The Arrhenius term highlights how reaction rates accelerate with temperature. In this study, the chemical reaction is modeled as a first-order homogeneous process occurring uniformly within the fluid. This widely adopted assumption simplifies the coupling between solute concentration and reaction rate, while ensuring physical consistency by considering the reaction rate directly proportional to the local solute concentration, without involving surface or heterogeneous effects.

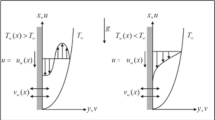

The boundary conditions in Eq. (7) describe the physical constraints of a rotating disk embedded in a quiescent fluid. At the wall (\(z = 0\)), the radial velocity \(u\, = \,\,0\) enforces the no-slip condition, preventing radial motion along the disk. The tangential velocity \(v = r\Omega\) ensures that the fluid rotates with the disk, initiating the swirl motion. The axial velocity \(w = w_{0}\) accounts for suction (\(w < 0\)) or injection (\(w> 0\)), modeling fluid drawn into or expelled from the surface. The temperature condition \(T\, = \,T_{w}\) fixes the disk at a constant wall temperature, driving heat transfer to or from the fluid depending on the thermal gradient, while \(C = \,C_{w}\) specifies a fixed wall concentration, initiating solutal diffusion. Far from the disk (z → ∞), all disturbances vanish, the velocities \(u,v,w \to 0\), temperature \(T \to T_{\infty }\), and concentration \(C \to C_{\infty }\), while the pressure returns to the ambient value \(P \to P_{\infty }\). Collectively, these conditions ensure that near the wall, the disk dictates motion, heat, and mass transfer, while at large distances the fluid remains undisturbed, restoring quiescent ambient conditions.

Rosseland approximation

Rosseland approximation is a well-established approach for modeling radiative heat transfer in optically thick media, where the photon means free path is much smaller than the characteristic length of the system. In such cases, radiative transport is predominantly driven by local temperature gradients due to the combined effects of absorption and emission. For nanofluids, the presence of suspended nanoparticles enhances absorption and scattering, thereby reducing the photon mean free path and reinforcing the assumption of optical thickness. Consequently, the application of the Rosseland diffusion model is physically appropriate for the Casson nanofluid examined in this study, particularly within the boundary layer where radiative interactions are significant. Under this framework, the radiative heat flux vector \(q_{r}\) is formulated to incorporate both emission and absorption processes making it a robust tool for characterizing radiative contributions to thermal energy transport31,43,46,48,58,59,67.

Here we will have \(T\, = \,T^{\infty } \left( {1 + \left( {\varepsilon - 1} \right)\theta } \right),\) here \(\varepsilon \, = \,{{T_{w} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{T_{w} } {T_{\infty } }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {T_{\infty } }}.\) In the energy equation, \(k^{*}\) denotes the Rosseland mean absorption coefficient, while \(\sigma^{*}\) represents the Stefan–Boltzmann constant. When temperature variations within the fluid are relatively small, the radiative term involving \(T^{4}\) can be expanded around the ambient temperature \(\left( {T_{\infty } } \right)\) using a Taylor series. By neglecting higher-order terms in this expansion, the radiative heat transfer expression is simplified, making it more tractable for analytical or numerical analysis.

With the implement nonlinear Rosseland diffusion approximation

By substituting the linearized form of \(T^{4}\) from Eqs. (8), (9) and (10) into the original energy Eq. (5), the modified form of the energy balance equation becomes:

Problem solution

A similarity transformation is employed to reduce the governing nonlinear partial differential equations of hybrid nanofluid dynamics into a system of ordinary differential equations. This approach reformulates the velocity, thermal, and solutal profiles in terms of a single similarity variable, thereby facilitating the analysis of boundary-layer flow over rotating disks. For the present hybrid nanofluid model, which accounts for both thermal and mass diffusion, the similarity variables are introduced following established formulations in the literature20,56,58.

The adopted similarity transformations are designed to exploit the rotational symmetry of the disk and the natural boundary layer scaling, thereby reducing the governing PDEs into a tractable set of ODEs. The radial and tangential velocity components are scaled with the disk surface speed \(\left( {r\Omega } \right),\) while the axial velocity is expressed in terms of the viscous length scale \(\sqrt {\upsilon_{f} /\Omega } \,,\) capturing the balance between centrifugal pumping and viscous diffusion. The similarity variable \(\zeta = y\sqrt {\Omega /\upsilon_{f} } \,,\) collapses the two spatial coordinates \(\left( {r,y} \right)\) into a single dimensionless variable representing the boundary layer thickness. Pressure is nondimensionalized with the viscous scale \(\mu_{f} \Omega ,\), ensuring that its gradients remain consistent with inertial and viscous forces after transformation. The temperature and concentration fields are normalized using wall to ambient differences, leading to simple boundary conditions. Altogether, this scaling captures the essential physical balances (centrifugal forcing versus viscous diffusion, and thermal/mass diffusion versus convection) while simultaneously simplifying the boundary conditions, which ensures the PDE system collapses into ODEs solely in terms of \(\zeta .\)

By substituting the similarity variables defined in Eq. (12) into the governing momentum, energy, and species Eqs. (2)–(6), the system of partial differential equations is transformed into a coupled set of ordinary differential equations, which are more amenable to analytical and numerical treatment.

The associated boundary conditions, expressed in terms of dimensionless variables, establish the coupling between the velocity, thermal, and concentration fields both at the surface and far from the boundary layer, and are given as follows:

where

To simplify the mathematical formulation, the physical variables are re-expressed in terms of dimensionless groups. These parameters account for the effects of magnetic forces \((M = {{\sigma_{hnf} B_{0}^{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\sigma_{hnf} B_{0}^{2} } {\rho_{f} \Omega }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\rho_{f} \Omega }}),\,\) Prandtl number \((\Pr = {{\nu_{f} \left( {\rho c_{p} } \right)_{f} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\nu_{f} \left( {\rho c_{p} } \right)_{f} } {k_{f} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {k_{f} }})\), Nonlinear thermal radiation parameter \((Rd = {{4\sigma^{*} T_{\infty }^{3} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{4\sigma^{*} T_{\infty }^{3} } {k^{*} k_{f} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {k^{*} k_{f} }})\), Eckert number \((E_{c} = {{\rho_{f} \left( {r\Omega } \right)^{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\rho_{f} \left( {r\Omega } \right)^{2} } {\left( {T_{w} - T_{\infty } } \right)\left( {\rho c_{p} } \right)_{f} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\left( {T_{w} - T_{\infty } } \right)\left( {\rho c_{p} } \right)_{f} }})\), Reynold number \(({\text{Re}} = {{r^{2} \Omega } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{r^{2} \Omega } {\upsilon_{f} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\upsilon_{f} }})\), Schmidt number \((S_{c} = {{\nu_{f} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\nu_{f} } {D_{f} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {D_{f} }})\), Temperature ratio parameter \((\varepsilon = {{T_{w} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{T_{w} } {T_{\infty } }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {T_{\infty } }})\), Chemical reaction parameter \((\sigma = {{k_{cr}^{2} a^{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{k_{cr}^{2} a^{2} } {\upsilon_{f} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\upsilon_{f} }})\) and Activation energy parameter \((E = {{E_{a} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{E_{a} } {KT_{\infty } }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {KT_{\infty } }})\), thereby providing a comprehensive framework for analyzing the velocity, thermal, and concentration distributions.

Engineering quantities

Heat transfer rate, mass transfer rate, and the associated skin friction coefficients are the prime quantities of engineering applications and may be described as20,56,63:

Here \({\text{Re}} = {{r\Omega } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{r\Omega } {2\nu_{f} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {2\nu_{f} }}\) depicts local Reynolds number. In rotating disk flow, these indicators capture the key transport processes within the boundary layer and act as benchmarks for model validation. Their accurate evaluation improves predictive reliability and aids in designing efficient thermal–fluid systems at micro- and nanoscale levels.

Computational method

In this work, we adopt a finite difference-based strategy to overcome the limitations of conventional approaches. The standard procedure of reducing the coupled system (13)–(16) to first-order equations and solving it with the Runge–Kutta method combined with the shooting technique often fails in the presence of widely separated eigenvalues, fast slow dynamics, or large integration intervals, which can lead to instability even with precise initial conditions (Nihaal et al.11). Although implicit and multi-step schemes may provide alternatives, they are usually computationally expensive. To address these challenges, the present study employs a finite difference formulation to approximate the derivatives at discrete grid points, and the resulting system is solved iteratively using the Successive Over-Relaxation (SOR) method. This approach ensures both stability and convergence while efficiently handling the prescribed boundary conditions.

The selection between SOR and bvp4c is primarily determined by the characteristics of the boundary value problem18,30,61. For highly nonlinear or strongly coupled systems, particularly those involving complex or slip-type boundary conditions, the SOR approach proves more effective because of its flexibility and robustness. On the other hand, for smooth and conventional problems that require high precision with minimal user adjustment, bvp4c is more appropriate, offering automated error control and reliable accuracy. In summary, SOR is better suited for complex or customized cases, whereas bvp4c performs best for smooth and standard problems. The decision flow for selecting between the SOR and bvp4c approaches is presented in Fig. 2(a). The advantages and disadvantages of the SOR method are summarized in Table 5.

The relaxation parameter plays a critical role in determining the efficiency of the method. A well-tuned \(\omega\) ensures stable and rapid convergence, while poor choices may lead to slow progress or divergence. In our computations, several values of ω were tested within the interval \(1 < \omega < 2\), as this is the theoretically stable range for most elliptic and parabolic PDE discretization. It was observed that values below 1.2 resulted in very slow convergence, while values above 1.9 often led to divergence of the iterative process. Based on numerical experiments, the optimal choice for our problem was found to be ω = 1.6, which provided a balance between stability and rapid convergence. A sensitivity analysis was also performed, confirming that the computed velocity, temperature, and concentration profiles remained unaffected (with variations below 0.1%) when ω was varied within ± 0.1 of the chosen value. This ensures that the numerical results are robust and reproducible.

Successive over-relaxation (SOR) method

Incorporating the substitution \(f{\prime} = r = {{df} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{df} {d\eta }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {d\eta }}\) into the nonlinear coupled system of Eqs. (13)-(16) with boundary conditions (17), we obtain the system in the form:

With BCs:

The semi-infinite domain is truncated to \(\left[ {0,R} \right]\), where \(R\) is chosen so that further extension does not affect the solution. The domain is then discretized evenly with step size h. For the discretization of the above system of equations, the central difference approximation is used for the derivatives, at a general grid point \(\eta = \eta_{i} .\) The resulting algebraic equations are solved iteratively using the Successive Over-Relaxation (SOR) method, considering the boundary conditions from Eq. (30). The numerical form of Eqs. (26), (27), (28) and (29) for SOR implementation is given below.

The following computational routes are adopted to accelerate the systems Eqs. (31), (32), (33) and (34).

-

At the beginning, we specify \(r^{(0)} ,\) \(g^{(0)} ,\) \(\theta^{(0)}\) and \(\phi^{(0)}\) as initial guesses that satisfy the BCs given in relation (30).

-

The Simpson’s rule is employed to approximate the linear system \(f{\prime} = r = {{df} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{df} {d\eta }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {d\eta }}\) is solved to determine \(f^{(1)}\).

-

The central differences are used in the system (31)-(34) instead of derivatives, and then the approximations \(r^{(1)} ,\) \(g^{(1)} ,\) \(\theta^{(1)}\) and \(\phi^{(1)}\) are found from the resultant algebraic system.

-

The procedure continues until all the respective sequences converge to \(f,\) \(r,\) \(g,\) \(\theta\) and \(\phi .\)

-

The iterative process is continued till the criterion:\(\max \left( {\left\| {r^{{\left( {i + 1} \right)}} - r^{\left( i \right)} } \right\|_{2} ,\,\,\left\| {f^{{\left( {i + 1} \right)}} - f^{\left( i \right)} } \right\|_{2} ,\,\left\| {g^{{\left( {i + 1} \right)}} - g^{\left( i \right)} } \right\|_{2} ,\,\,\left\| {\theta^{{\left( {i + 1} \right)}} - \theta^{\left( i \right)} } \right\|_{2} ,\,\,\left\| {\phi^{{\left( {i + 1} \right)}} - \phi^{\left( i \right)} } \right\|_{2} } \right) < 10^{ - 8} ,\)

is met. For all the computations carried out in this study, the value is at least \(10^{ - 8}\). The flow chart of the adopted numerical technique is shown in Fig. 2(b).

Validation of numerical scheme

The numerical results for nondimensional velocity \(f(\zeta )\) on three grid sizes for \(fw = M = \,Ec\, = Rd = nn = 0.5\,,\,\varepsilon = 1.2,\,{\text{Re}} = 1,\Pr = 6.2,Sc = 0.9,E = 0.1,\sigma = 1.5\) are listed in Table 6. To confirm the correctness of the implemented code, results for a limiting case are compared with those reported by Kanwal et al.20 and Abdel-Wahed et al.58 (see Tables 7 and 8). The close agreement between the datasets confirms the reliability and precision of the proposed numerical method.

Results and discussion

This section investigates the influence of physical parameters on the velocity, concentration, and temperature profiles of hybrid nanofluid flow. Comparative analyses for nanofluid, and hybrid nanofluid are presented in Figs. 3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21 and 22, illustrating the role of physical constraints in altering flow and heat transfer properties. Furthermore, the study incorporates two types of nanoparticles: SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\), represented by solid lines, and MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\), represented by dashed lines in the plots. The working parameters and their ranges are selected based on values commonly reported in recent literature20,49,56,58, ensuring physical relevance, numerical stability, and meaningful representation of practical hybrid nanofluid flow applications. Each parameter is graphically analyzed by keeping the remaining parameters fixed at constant values within a specified range like \(0.1\, < fw\, < 0.9,\) \(0.4\, < M\, < 2.0,\)\(1.5\, < \varepsilon < 1.9,\)\(0.5\, < Ec\, < 2.5,\)\(0.1\, < Rd\, < 0.9,\)\(2.2\, < \Pr \, < 6.2,\)\(0.1\, < Sc\, < 0.9,\)\(0.5\, < E < 2.5,\)\(0.5 < \sigma < 1.5.\) The Prandtl number is fixed to 6.2 for water-based fluid at room temperature with volume fraction 0.01 < ϕ1 = ϕ2 > 0.09.

v

Effect of magnetic field parameter and suction/injection parameter

Figures 3, 4 and 5 illustrate the influence of the magnetic parameter M on the radial velocity \(f^{\prime}\left( \zeta \right)\), transverse velocity \(g\left( \zeta \right)\), and temperature field \(\theta \left( \zeta \right)\) for hybrid type nanofluids SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\) & MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) with different nanoparticle geometries (brick, cylinder). It is evident that increasing M leads to a reduction in both radial and transversal velocity components. The spike observed near \(\zeta = 0\) in Fig. 3 originates from the strong interaction between the rotating disk and the imposed magnetic field. At the disk surface, the fluid is subjected to the no slip condition while simultaneously experiencing the Lorentz force generated by the applied transverse magnetic field. This force directly resists fluid motion, resulting in a steep velocity gradient within the near wall region. The spike reflects the fluids rapid adjustment to this force balance, where rotational inertia attempts to drive the flow outward while magnetic resistance suppresses it. As the magnetic parameter M increases, the enhanced resistive force reduces the intensity of the spike, indicating stronger damping effects on the radial velocity. The attenuation of the velocity profile farther from the wall demonstrates that magnetic control is most pronounced near the boundary layer, diminishing as the influence of the wall weakens. Figure 4 depicts a similar trend for the transverse velocity \(g\left( \eta \right)\), where larger values of M cause further suppression of fluid motion. This trend aligns with the earlier findings of Waqas et al.56.

Figure 5 illustrates the influence of the magnetic parameter M on the dimensionless temperature profile \(\theta \left( \eta \right)\) for SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\) & MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\)hybrid nanofluids with different nanoparticle geometries (brick, cylinder). As M increases, the thermal boundary layer thickness decreases, leading to a sharper decay in temperature distribution. Physically, the Lorentz force generated by the applied magnetic field resists fluid motion and induces an additional drag effect. This enhances viscous dissipation, which in turn augments energy absorption near the wall and accelerates the thermal relaxation of the fluid. Consequently, higher values of M suppress the temperature farther from the wall and strengthens heat transfer at the boundary. Moreover, the distinction between brick-shaped and cylindrical nanoparticles highlights the role of shape factor in controlling effective conductivity: brick-shaped particles enhance energy diffusion more efficiently, yielding relatively higher thermal retention compared to cylindrical ones. Overall, the results confirm that both magnetic effects and nanoparticle morphology critically govern the heat transfer performance in hybrid nanofluids under nonlinear radiation and activation energy influences. A similar pattern has been reported in the previous work of Waqas et al.56.

The magnetic parameter characterizes the influence of an applied magnetic field on electrically conducting nanofluids. In engineering practice, this has direct applications in magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) pumps, nuclear cooling systems, and plasma confinement devices, where precise control of fluid motion is achieved using magnetic fields. Additionally, in metal casting and semiconductor manufacturing, MHD effects are exploited to suppress instabilities and improve product quality.

Figures 6 and 7 reveal that increasing the suction/injection parameter \(\left( {fw\,} \right)\) reduces both radial \(f^{\prime}\left( \eta \right)\) and transverse \(g\left( \eta \right)\) velocities of the SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\) & MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) hybrid type nano liquids. In Fig. 6, the spike near \(\zeta = 0\) is a direct outcome of wall mass flux. Suction accelerates the removal of fluid particles from the near-wall region, leading to sharper gradients in radial velocity and a confined, narrow spike. This reflects a thinner boundary layer with reduced momentum thickness, as suction effectively stabilizes the flow and enhances momentum transport away from the surface. Conversely, injection introduces additional fluid into the boundary layer, causing crowding near the wall and amplifying the overshoot in velocity. The resulting spike is broader and of greater magnitude, showing that injection promotes boundary-layer growth and enhances radial outflow near the disk. This behavior highlights how wall mass transfer critically modifies the near-surface momentum balance, with suction promoting stabilization and injection fostering destabilization. These results agree with the prior study conducted by Waqas et al.56. Figure 7 depicts the effect of the suction parameter on the transversal velocity profile. Increasing suction decreases the boundary layer thickness and accelerates the decay of velocity, as fluid is drawn toward the wall and mass diffusion is suppressed. This enhanced wall suction stabilizes the flow and limits particle dispersion. Moreover, the comparison between SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\) & MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) indicates that nanoparticle type and geometry significantly impact mass transfer behavior, reflecting their distinct diffusivity and interaction characteristics within the fluid. The observed trend is consistent with the findings of Waqas et al.56. Figure 8 reveals that the temperature field also exhibits a pronounced spike near \(\zeta = 0\), which stems from steep thermal gradients at the disk surface. Suction enhances convective heat transfer by removing hot fluid particles from the vicinity of the wall, resulting in a higher but narrower spike. This corresponds to a thinner thermal boundary layer and indicates improved cooling efficiency under suction conditions. In contrast, injection introduces additional fluid with higher thermal energy near the wall, broadening the temperature profile and producing a more gradual decay in the boundary layer. This leads to greater near wall thermal accumulation, reducing the cooling effectiveness. The variation of the spike with \(\left( {fw\,} \right)\) illustrates the strong coupling between mass flux and thermal transport, where suction strengthens energy removal while injection enhances heat retention. This trend aligns with the earlier findings of Waqas et al.56. The wall mass flux parameter governs suction and injection at the rotating surface. Suction is widely used in aerodynamic flow control to delay boundary-layer separation and reduce drag on aircraft wings and turbine blades. In contrast, injection plays a vital role in coolant distribution systems, fuel injection in combustion chambers, and chemical vapor deposition processes, where controlled addition of fluid enhances mixing, heat transfer, or reaction efficiency.

Effect of temperature ratio, Prandtl number, viscous dissipation and nonlinear thermal radiation

Figure 9 shows that increasing the temperature ratio parameter amplifies the thermal field for SWCNT \(TiO_{2}\)& MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) hybrid nanofluids. This trend arises because a higher surface to ambient temperature ratio strengthens the thermal driving force, thereby thickening the thermal boundary layer. Notably, brick shaped nanoparticles (SF = 3.7) exhibit a stronger thermal field compared to cylindrical particles (SF = 4.9). This behavior is linked to the enhanced effective thermal conductivity of brick geometries, which facilitate superior heat transport within the fluid. Consequently, the thermal response of the hybrid nanofluid is not only governed by the temperature ratio but also significantly modulated by nanoparticle morphology. These results agree with the prior study conducted by Waqas et al.56 and Abdel-Wahed et al.58. The temperature ratio parameter represents the effect of surface-to-ambient temperature gradients on heat transfer. It finds application in thermal barrier coatings, turbine blade cooling, and electronic chip thermal management, where large temperature differences dictate system performance. In renewable energy systems, such as solar thermal collectors, the parameter helps optimize absorber plate design by accounting for non-linear temperature variations.

Figure 10 demonstrates that increasing the Prandtl number reduces the temperature distribution in the hybrid nanofluid. This occurs because a higher Prandtl number signifies weaker thermal diffusivity relative to momentum diffusivity, which restricts heat from spreading deeply into the fluid and results in a thinner thermal boundary layer. Consequently, less thermal energy is retained within the fluid domain. Moreover, the effect of nanoparticle shape factor is evident larger shape factors enhance effective thermal conductivity, allowing faster transport of heat away from the near wall region. This combined influence leads to a sharper decline in the temperature field, underscoring the critical role of Prandtl number in controlling heat transfer behavior in nanofluid systems. The observed trend is consistent with the findings of Waqas et al.56. The Prandtl number represents the relative strength of momentum to thermal diffusivity. Its relevance spans from cryogenic cooling systems (low Pr) to lubrication oils and molten salts (high Pr), determining the design of thermal management systems. In nanofluid applications, tuning Pr helps optimize heat exchangers and biomedical cooling devices.

Figures 11 and 12 illustrate the influence of the Eckert number (Ec) and nonlinear radiation parameter (Rd) on boundary layer temperature. An increase in the Eckert number amplifies viscous dissipation, converting kinetic energy into internal energy and elevating the fluid temperature. Shape factors further influence this behavior, larger factors (e.g. SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\)) enhance effective thermal conductivity, redistributing dissipated heat more efficiently than smaller factors (e.g. MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\)). This combined effect leads to a stronger thermal response near the rotating disk. This trend aligns with the earlier findings of Waqas et al.56 and Abdel-Wahed et al.58. The Eckert number quantifies viscous dissipation and kinetic energy conversion into thermal energy. This parameter becomes significant in turbomachinery, high-speed gas turbines, and microchannel heat exchangers, where strong viscous forces and frictional heating can elevate fluid temperatures and affect efficiency.

In the case of nonlinear thermal radiation, increasing reduces the mean absorption coefficient, intensifying radiative heat transfer. This nonlinearity amplifies temperature growth within the boundary layer, especially in regions where temperature gradients are high, making radiation effects more dominant than in the linear case. In summary, incorporating nonlinear radiation into the governing equations enables the model to capture intense thermal effects present in high-temperature or steep temperature-gradient flows. These results agree with the prior study conducted by Waqas et al.56 and Abdel-Wahed et al.58. The Rosseland radiation parameter describes thermal radiation effects in optically thick media. Its applications include solar energy collectors, thermal insulation systems, and high-temperature reactors, where radiative heat transfer significantly alters thermal behavior. In aerospace technology, radiation modelling is crucial for re-entry vehicles subjected to extreme thermal loads.

Effect of Schmidt number, Arrhenius energy, chemical reaction and nanoparticles concentration

Figures 13, 14 and 15 present the influence of Schmidt number (Sc), activation energy (E), and chemical reaction rate \(\left( \sigma \right)\) on the concentration distribution in SWCNT- \(TiO_{2}\)& MWCNT- \(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) hybrid type nano liquids. An increase in the Schmidt number reduces the concentration boundary layer, as higher momentum diffusivity relative to mass diffusivity limits species diffusion into the fluid. This effect is further strengthened by chemical reactions, which consume solute, and by activation energy, which controls the reaction rates sensitivity to temperature. Together, these parameters regulate species transport and result in thinner concentration profiles near the rotating disk. (please see Fig. 13). The Schmidt number relates momentum diffusivity to mass diffusivity and is critical in chemical process industries, membrane separation, and environmental engineering (e.g., pollutant dispersion in water bodies). Controlling Sc is essential in catalytic reactors and electrochemical energy devices for efficient mass transfer.

An increase in the chemical reaction parameter intensifies the rate of species consumption within the fluid. As the reaction rate becomes stronger, solute particles are depleted more rapidly near the rotating disk, which suppresses diffusion into the bulk fluid. (Please see Fig. 15). This accelerated consumption manifests as a sharper decline in concentration profiles and a thinner concentration boundary layer. The effect is particularly pronounced when coupled with higher Schmidt numbers, as limited mass diffusivity restricts replenishment of species from the outer flow. In addition, the interplay with activation energy further refines this behavior at elevated temperatures, lower activation energy enhances the reaction rate, amplifying concentration decay, whereas higher activation energy moderates this effect. The chemical reaction parameter quantifies the influence of homogeneous chemical reactions within the fluid phase. Applications include pollutant dispersion modeling, corrosion inhibition, fuel oxidation, and electrochemical energy devices. In biomedical engineering, this parameter is useful for drug delivery systems and tissue engineering, where controlled reaction diffusion mechanisms govern therapeutic outcomes. Conversely, higher activation energy acts as a barrier to reaction initiation, requiring greater thermal energy for molecules to react. This slows the reaction rate at the same temperature, allowing more particles to survive transport and resulting in an elevated concentration profile (please see Fig. 14). Physically, this reflects the balance between molecular diffusion, reaction kinetics, and thermal activation energy in controlling mass transport in reactive nanofluid systems. In this model, activation energy (E) represents the minimum thermal energy required for chemical reactions to occur within the SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\)& MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) hybrid type nano liquids. Higher E slows the reaction rate, allowing more species to remain in the fluid. This increases the concentration boundary layer and changes how heat and mass transfer interact. The activation energy parameter models the sensitivity of chemical reaction rates to temperature variations, as described by Arrhenius kinetics. It is particularly relevant in catalytic reactors, polymer processing, biochemical reactors, and combustion systems, where precise control of temperature dependent reaction rates is critical. In nanofluid assisted chemical processes, incorporating activation energy improves predictive modeling for reaction efficiency and product yield.

Effect of nanoparticles concentration

Figure 16 shows the variation of radial velocity profiles with increasing nanoparticle volume fractions \(\left( {\phi_{1\,\,} = \,\,\phi_{2\,\,} } \right)\) for SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\)& MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) hybrid nanofluids over a rotating disk. It is evident that higher nanoparticle concentration suppresses the radial velocity, leading to a thinner momentum boundary layer. This reduction is attributed to the increase in effective viscosity and density of the hybrid suspension when additional nanoparticles are introduced. The heavier and more viscous fluid resists radial stretching induced by the disk rotation, thereby reducing the outward transport of momentum. Moreover, the difference between brick and cylinder shaped particles reflects the role of geometry dependent thermal conductivity: cylindrical MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\)nanostructures, with higher shape factor, provide greater resistance to fluid motion than brick shaped SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\), amplifying the suppression effect. Physically, this suggests that tuning particle shape and volume fraction offers a means of controlling flow resistance in nanofluid-based rotating machinery.

Figure 17 presents the corresponding transversal velocity response under the same conditions. Like the radial case, increasing nanoparticle loading reduces the transversal velocity, demonstrating a dampening effect on the secondary motion generated by disk rotation. This decline originates from the enhanced inertia and viscous drag of the nanoparticle laden fluid, which suppresses the vertical transport of momentum. Additionally, the nonlinear Rosseland thermal radiation mechanism indirectly influences this trend by redistributing thermal energy across the boundary layer, thus modifying buoyancy driven components of the flow. The presence of Arrhenius activation energy further couples the thermal and concentration fields, stabilizing the fluid motion and reducing transversal fluctuations. Between the two nanoparticle morphologies, brick shaped SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\) exhibits slightly higher transversal velocities than cylindrical MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} ,\) owing to relatively lower flow resistance.

Figure 18 illustrates how the volume fraction of nanoparticles and particle shape factors brick and cylinder influence the temperature distribution in SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\) & MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) hybrid type nano liquids flow. Increasing boosts the suspensions thermal conductivity, enhancing heat transport and raising temperature distribution. The SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\) component offers exceptional axial thermal conductivity, while MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) contributes both good heat conduction and magnetic responsiveness, enabling more efficient energy exchange. Shape factors further control the heat transfer rate by altering particle surface area and interaction with the fluid, with favorable geometries (e.g. rotating disk) delivering stronger thermal enhancement.

Effect of hybrid nanoparticles on Radial & Transversal Skin friction, Nusselt number and Sherwood number

The results show that radial and transverse skin friction coefficients, as well as the Nusselt number, remain nearly uniform in ζ but vary systematically with wall mass flux \(f_{w}\) and nanoparticle volume fraction \(\phi_{\,1} = \phi_{\,2}\).With increasing nanoparticle loading \((\phi_{\,1} = \phi_{\,2} )\) the radial skin-friction increases slightly for both hybrid fluids, indicating larger near wall shear (please see Fig. 19). This behavior is consistent with the nanoparticles increasing the effective suspension viscosity and momentum diffusivity; higher viscosity enhances the wall shear generated by the centrifugal acceleration of the rotating disk. Between the two hybrid pairs, the SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\) mixture yields a modestly higher radial skin friction than MWCNT-\(CoFe_{3} O_{4}\) at identical (\(\phi_{\,1} = \phi_{\,2}\)), which reflects differences in the composite thermophysical properties (shape factor and constituent conductivities) that change the effective viscosity and momentum transport. Increasing the wall mass-flux parameter \(f_{w}\)(i.e., stronger wall mass transfer in the chosen direction) reduces the radial skin friction coefficient in the present configuration, this indicates that the imposed mass flux modifies the near-wall momentum balance so as to lower the net shear at the disk surface (in the present sign convention, stronger wall flux produces an effective thickening of the momentum layer and hence reduced wall shear).

The transverse (azimuthal) skin friction displays a similar dependence, its magnitude changes systematically with \(\phi_{\,1} = \phi_{\,2}\) and \(f_{w}\)(Please see Fig. 20). Increasing nanoparticle concentration slightly increases the absolute transverse shear, consistent with enhanced viscous coupling in the azimuthal direction produced by higher effective viscosity. The two hybrid formulations again differ quantitatively, reflecting particle shape and material contrast that influence effective rheology. The monotonic variation with \(f_{w}\) shows that wall mass flux directly alters the azimuthal momentum transport near the disk; stronger wall flux shifts the balance of centrifugal and viscous forces, producing the observed change in transverse shear.

In Fig. 21,.the local Nusselt number decreases as the wall mass-flux parameter \(f_{w}\) increases in the present parameterization, implying diminished convective heat extraction from the disk with stronger wall flux in the chosen direction. Increasing nanoparticle volume fraction produces a small but discernible rise in the Nusselt number for both hybrid fluids, indicating improved heat transfer due to enhanced effective thermal conductivity of the suspension. The SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\) hybrid yields a slightly higher Nusselt number than MWCNT-\(CoFe_{3} O_{4}\) at the same \(\phi_{\,1} = \phi_{\,2}\), consistent with its greater enhancement of effective conductivity in the chosen thermo-physical model. Nonlinear Rosseland radiation increases the temperature sensitivity of thermal diffusion (the radiative conductive term scales with \(T^{3} \Delta T\)), so thermal gradients near the disk respond more strongly to changes in \(\phi_{\,1} = \phi_{\,2}\) and \(f_{w}\) then they would under a linearized radiative model. This amplifies the small increases in Nusselt number observed with rising. The Arrhenius activation energy couples the chemical kinetics to the local temperature field: temperature-sensitive reaction rates modify concentration profiles and may act as local heat sinks or sources, which in turn perturb the thermal boundary thickness and the Nusselt number. In the present parameter range these couplings produce modest adjustments to the heat-transfer and shear metrics, but they are important for accurate prediction in reactive, high-temperature rotating systems.

Figure 22 presents the variation of the Sherwood number with increasing nanoparticle volume fractions \(\phi_{\,1} = \phi_{\,2}\) for SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\) and MWCNT-\(CoFe_{3} O_{4}\) hybrid nanofluids with distinct shape factors, namely brick and cylinder. A consistent decreasing trend in the Sherwood number is observed as the wall suction parameter (\(f_{w}\)) increases. Physically, stronger suction extracts fluid from the boundary layer, thereby reducing species concentration gradients near the surface. This attenuation of concentration transfer manifests as a reduction in the Sherwood number. The influence of nanoparticle volume fractions (\(\phi_{\,1} = \phi_{\,2}\)) is relatively weak, and the Sherwood number curves remain nearly parallel across the range of ζ. This behavior arises because mass transport in hybrid nanofluids is less sensitive to nanoparticle loading compared with momentum and thermal fields. Comparing shapes, brick-type nanoparticles (n = 3.7) exhibit slightly higher Sherwood number magnitudes compared with cylindrical ones (n = 4.9). This can be attributed to differences in effective surface area and interaction with the base fluid, which alter micro-convective mass transfer. Bricks enhance particle–fluid interaction more efficiently, thereby promoting stronger concentration gradients at the wall.

The combined effect of hybrid nanoparticle loading, particle geometry (shape factor), wall mass flux, nonlinear radiation, and temperature-dependent reaction kinetics yields measurable but controlled changes in wall shear and heat transfer. For rotating-disk applications (e.g., high speed seals, disk reactors, and rotating heat exchangers), small increases in nanoparticle fraction can be used to enhance heat removal at the cost of modestly higher wall shear; conversely, manipulating wall mass flux provides an effective control parameter to tune both shear and thermal performance.

Table 9 illustrates the variation of skin friction with changes in the suction/injection parameter under different magnetic field strengths. Table 10 presents the influence of the nonlinear radiation parameter, Prandtl number, and Eckert number on the Nusselt number for various values of the temperature ratio parameter. Table 11 highlights the variation of the Sherwood number with Schmidt number and chemical reaction rate in the presence of activation energy.

Final remarks

The present study analyzed the flow and heat/mass transfer characteristics of hybrid nanofluids (SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\) & MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\)) over a rotating disk under the influence of nonlinear thermal radiation and Arrhenius activation energy with chemical reaction, solved using the SOR method. Some key concluding remarks are as follows:

-

Radial and tangential velocities of the SWCNT -\(TiO_{2}\) & MWCNT- \(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) hybrid nanofluid decrease with stronger magnetic fields, while suction/injection parameters influence fluid motion, by reducing velocity.

-

Thermal profiles rise with higher magnetic parameters, temperature ratio, Eckert number, and nanoparticle volume fraction, with noticeable dependence on particle shape factors.

-

Prandtl number, along with suction/injection, tends to suppress temperature distribution, and higher solid friction further raises thermal levels.

-

Larger Schmidt number and stronger chemical reaction rates reduce concentration, whereas higher activation energy boosts mass transfer.

-

Nonlinear radiation and activation energy introduce a strong coupling between thermal and concentration fields, capturing realistic radiative and chemically reactive transport effects in high-temperature rotating systems.

-

Radial and transverse skin friction were found to increase with nanoparticle volume fraction, confirming enhanced momentum transport due to higher effective viscosity and thermal conductivity of hybrid suspensions.

-

Radial skin friction decreases by about 44% as the magnetic parameter increases (M = 0.4 → 2.0), while tangential skin friction becomes more negative, with its magnitude rising by nearly 78% at low suction and about 37% at high suction.

-

The Nusselt number rises significantly with nanoparticle loading, indicating improved convective heat transfer, with SWCNT-\(TiO_{2}\) yielding superior performance compared to MWCNT-\(CoFe_{2} O_{4} \,\) because of its higher aspect ratio and stronger thermal conductivity. The heat transfer rate increases by about 11.9%, rising from 25.27% at Rd = 0.5 to 37.18% at Rd = 1.4.

-

Furthermore, rotation enhances radial advection and secondary flows, producing thin boundary layers, elevated local Nusselt numbers, and anisotropic temperature distributions, thereby highlighting the coupled effects of flow dynamics and heat transport in rotating hybrid nanofluid systems.

Limitations, future scope, applications of the current research work

Limitations: The model assumes incompressibility, constant thermophysical properties, and negligible magnetic Reynolds number, which restricts its applicability to moderate temperature differences and low Mach number flows. Nonlinear radiation and chemical kinetics are simplified to first-order homogeneous reactions, and nanoparticle agglomeration or slip effects are not considered.

Future Scope: The study can be extended to unsteady or turbulent regimes, variable thermophysical properties, higher order or heterogeneous reactions, and more complex nanoparticle interactions. Coupling with experimental validation and advanced numerical solvers could further enhance applicability.

Applications: Findings are relevant to high temperature rotating systems, catalytic reactors, polymer extrusion, MHD energy systems, biomedical processes, and thermal management technologies utilizing hybrid nanofluids.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- (u,v,w) :

-

Velocity components (ms-1)

- w 0 :

-

Suction/injection

- Ω:

-

Angular velocity

- σ:

-

Electrical conductivity (Ω-1m-1)

- P:

-

Pressure (Nm-2)

- μhnf, ρhnf, khnf, Dhnf, σhnf :

-

Dynamic viscosity, density, thermal conductivity, diffusivity and electrical conductivity of hybrid nanofluid (kg/m3)

- μf, ρf, kf, Df, σf :

-

Dynamic viscosity, density, thermal conductivity, diffusivity and electrical conductivity of base fluid (kg/m3)

- ʋf :

-

Kinematic viscosity of nanofluid (m2/s)

- ρC p :

-

Specific heat capacity (JKgK)

- B 0 :

-

Magnetic field variable (Ω-1/2m-1s-1/2kg1/2)

- T ∞ :

-

Temperature away from the surface (k)

- C ∞ :

-

Concentration away from the surface

- σ∗ :

-

Stefan–Boltzmann constant (Ω-1m-1)

- qr :

-

Radiative heat flux (kgs-3)

- k ∗ :

-

Mean absorption coefficient (m-1)

- T :

-

Non-dimensional temperature (K)

- C :

-

Non-dimensional concentration

- f w :

-

Suction and injection

- ζ:

-

Dimensionless variable

- f ’ :

-

Dimensionless radial velocity

- g :

-

Dimensionless transversal velocity

- θ :

-

Dimensionless temperature

- ϕ:

-

Dimensionless concentration

- ϕ1 :

-

The volume of nanoparticles concentration of SWCNT-TiO2

- ϕ2 :

-

The volume of nanoparticles concentration of MWCNT-COFe2O4

- M=σhnf \({B}_{0}^{2}\) /ρfΩ:

-

Magnetic interaction parameter

- Pr=ʋf(ρc P)f/kf :

-

Prandtl number

- Rd=4σ∗ \({T}_{\infty }^{3}/{k}^{*}{k}_{f}\) :

-

Nonlinear thermal radiation parameter

- Ec=ρf(rΩ)2/Tw-T ∞)(ρcp):

-

Eckert number

- Re=r2Ω/ʋf :

-

Reynold number

- Sc=v f/Df :

-

Schmidt number

- ε=T w/T ∞ :

-

Temperature ratio parameter

- σ=\({k}_{cr}^{2}\) a 2/ʋf :

-

Chemical reaction parameter

- E=Ea /KT ∞ :

-

Activation energy parameter (J)

- C f :

-

Radial skin friction

- C fr :

-

Dimensionless skin friction

- C g :

-

Tangential skin friction

- C gr :

-

Dimensionless tangential skin friction

- Nu :

-

Nusselt number

- Sh :

-

Sherwood number

References

Von Karman, T. Classical problem of rotating disk. Transfer ASME 61, 705 (1939).

Cochran, W. G. The flow due to a rotating disk. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 30(3), 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305004100012561 (1934).

Benton, E. R. On the flow due to a rotating disk. J. Fluid Mech. 24(4), 781–800. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112066001009 (1966).

Rogers, M. H. & Lance, G. N. The rotationally symmetric flow of a vis cous fluid in presence of infinite rotating disk. J. Fluid Mech. 7(4), 617–631. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112060000335 (1960).

Erdogan, M. E. Unsteady flow of a viscous fluid due to non-coaxial rotations of a disk and a fluid at infinity. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 32(2), 285–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7462(96)00065-0 (1997).

Sheikholeslami, M., Hatami, M. & Ganji, D. D. Nanofluid flow and heat transfer in a rotating system in the presence of a magnetic field. J. Mol. Liq. 190, 112–120 (2014).

Turkyilmazoglu, M. Nanofluid flow and heat transfer due to a rotating disk. Comput. Fluids 94, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2014.02.009 (2014).

Choi, S. U. & Eastman, J. A. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles 99–105 (Argonne National Lab, 1995).

Nihaal, K. M., Mahabaleshwar, U. S. & Joo, S. W. Darcy Forchhiemer imposed exponential heat source-sink and activation energy with the effects of bioconvection over radially stretching disc. Sci. Rep. 14, 7910. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58051-5 (2024).

Nihaal, K. M., Mahabaleshwar, U. S., Swaminathan, N., Laroze, D. & Shevchuk, I. V. A numerical investigation of activation energy impact on MHD water-based Fe3O4 and CoFe2O4 flow between the rotating cone and expanding disc. Mathematics 12(16), 2530. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12162530 (2024).

Nihaal, K. M., Mahabaleshwar, U. S., Laroze, D. & Wang, J. Thermal analysis of casson-based hybrid nanofluid flow on a permeable stretching surface with heat source and sink: A new stochastic Approach. Int. J. Thermophys. 46, 80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10765-025-03546-0 (2025).

Ahmad, S. et al. Novel thermal aspects of hybrid nanofluid flow comprising of manganese zinc ferrite MnZnFe2O4, nickel-zinc ferrite NiZnFe2O4, and motile microorganisms. Ain Shams Eng. J. 13(5), 101668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2021.101668 (2022).

Muhammad, N. & Nadeem, S. Ferrite nanoparticles Ni-ZnFe2O4, Mn-ZnFe2O4, and Fe2O4 in the flow of ferromagnetic nanofluid. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 132(377), 1–12 (2017).

Zhao, T. H. et al. Comparative study of ferromagnetic hybrid (manganese zinc ferrite, nickel zinc ferrite) nanofluids with velocity slip and convective conditions. Phys. Scr. 96(7), 075203. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/abf26b (2021).

Firew, D., Nallamothu, R. B., Alemayehu, G. & Gopal, R. Performance and emission evaluation of CI engine fueled with ethanol diesel emulsion using NiZnFe2O4 nanoparticle additive. Heliyon 8(11), e11639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11639 (2022).

Noor, S. & Mukhtar, S. Study of heat transfer in magnesium zinc zirconium MgZn6Zr alloy suspended in engine oil. J. Math. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9950020 (2021).

Maraj, E. N. & Shaiq, S. Rotational impact on nanoscale particles Fe2O4, NiZnFe2O4, MnZnFe2O4 suspended in C2H6O2 confined between two stretchable disks: a computational study. Can. J. Phys. 98(3), 312–325. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjp-2019-0208 (2020).

Sachhin, S. M., Mahabaleshwar, U. S., Nayakar, S. N. R. & Oronzio, M. Effect of Brinkman number on Chemically reactive Bi-viscous Bingham hybrid nanofluid flow across the penetrable sheet with mass transfer. CU J. Nonlinear Fluid Mech. 1(01), 43–60. https://doi.org/10.11615/cujnlfm.01104-5 (2025).

Bhaskar, K., Sharma, K., Bhaskar, K. & Chamkha, A. J, Impact of non-uniform heat flux, Arrhenius activation energy on gyrotactic microorganisms in conducting a nanofluid flow. Int. J. Ambient Energy 45(1), 2402737. https://doi.org/10.1080/01430750.2024.2402737 (2024).

Kanwal, S. et al. Insight into the dynamics of heat and mass transfer in nanofluid f low with linear/nonlinear mixed convection, thermal radiation, and activation energy effects over the rotating disk. Sci. Rep. 13, 23031. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49988-0 (2023).

Nisar, Z., Hayat, T., Alsaedi, A. & Ahmad, B. Significance of activation energy in radiative peristaltic transport of Eyring-Powell nanofluid. Int. Com. Heat Mass Transf. 116, 104655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2020.104655 (2020).