Abstract

Acute febrile illness (AFI) is a sudden fever which can be caused by various viruses such as dengue, Zika, and chikungunya viruses. This study aimed to identify viruses present in AFI patients via metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) through meta-analysis, and to compare the prevalence and viral load of the common viruses between AFI patients and healthy blood donors in northeastern Thailand. Our meta-analysis revealed that human anelloviruses—including torque teno virus (TTV), torque teno mini virus (TTMV), and torque teno midi virus (TTMDV)—were the most prevalent viruses detected. We confirmed their presence in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 203 AFI patients and 100 healthy blood donors using real-time PCR. TTV was the most identified anellovirus, detected in 84% of healthy donors and 61.08% of AFI patients. The mean TTV load was significantly lower in AFI patients compared to healthy donors. In AFI patients, TTV load increased in those with higher total white blood cell and neutrophil counts but decreased in those with higher lymphocyte counts. Our findings demonstrate high prevalence of anelloviruses, particularly TTV, in both AFI patients and healthy donors, and highlight the potential value of the TTV load in blood as an immune status biomarker in AFI patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute febrile illness (AFI) is a fever sickness that occurs suddenly and without warning. It is common in tropical and subtropical regions, including Thailand1. AFI is caused by infection of a wide variety of pathogens (viruses, bacteria, or protozoa) or non-infection (such as autoimmune diseases, transfusion reactions, and drug hypersensitivity)2,3. Usually, such fevers resolve without treatment, but fevers may result in severe and potentially fatal illnesses, which are treatable if caught early and treated properly. Clinical characteristics of AFI are similar to other fever disorders, such as high body temperature of more than 37.5 °C, headache, arthralgia, and myalgia. The current study in Southeast Asia reported that viruses (33.0%), bacteria (20.6%), protozoa (2.4%), and co-infections (3.4%) were shown to be the main causes of AFI4. The most common viruses that cause AFI have been identified as the dengue virus, followed by the influenza and chikungunya viruses, with fatalities occurring at a rate of 0.5% in Southeast Asia4.

Although AFI has various etiologies, its clinical presentation is often nonspecific, particularly in the early stages of onset. Since the capacity to investigate the causative pathogen of AFIs may be insufficient in low- and middle-income countries, patient management may not be optimal. Traditional diagnosis for AFI has mainly been serological tests, although they may not provide a complete picture of the data. Currently, the factors most frequently associated with AFI have changed, with new causes becoming more recognized. Available diagnostic tools have a limited ability to detect viruses that cause emerging diseases, as well as new or unexpected virus strains that may be the cause of the disease. There has been a re-emergence of viruses previously under control (such as Zika, Nipah) and the appearance of novel pathogens (such as severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus; SFTSV) that had not been identified in clinical settings before5,6,17. This may lead to misdiagnosis, ineffective treatment, and disease spreading, leading to worldwide pandemics and public health issues. Thus, surveillance and detection of disease-causing unexpected viruses are essential.

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) is a platform that can simultaneously identify genetic material (genomes) from entirely different kingdoms of organisms. It is a massively parallel sequencing technology that provides ultra-high throughput, scalability, and speed7. mNGS enables laboratories to swiftly sequence complete genomes, deeply sequence specific sections, research the human microbiome, and discover new pathogens.

Among the viral taxa widely distributed in humans are human anelloviruses: small, non-enveloped DNA viruses about 30–50 nm in diameter and possess circular, negative-sense, single-stranded DNA genomes. They belong to the Anelloviridae family, which consists of 12 genera. Only three genera, Alphatorquevirus (Torque Teno Virus: TTV), Betatorquevirus (Torque Teno Mini Virus: TTMV), and Gammatorquevirus (Torque Teno Midi Virus: TTMDV) cause infections in humans. These anelloviruses are known for their high prevalence in human populations. However, they have not been conclusively associated with any specific disease. Some studies suggest that the level of anellovirus infections in humans may change with immune system status, like in immunocompromised individuals8,9,10,11,12.

Here, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of data obtained from multiple databases to analyze the virome profile identified by mNGS in patients with AFI and to assess the link between the virome and AFI. Anelloviruses are commonly detected in AFI patients, therefore we extended the meta-analysis findings by examining the prevalence and viral load of the viruses in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from AFI patients and healthy blood donors in Northeastern Thailand.

Results

Characteristics of studies included for meta-analysis

The publications were retrieved from three databases, including PubMed, Scopus and ScienceDirect. The study selection flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1. We conducted a preliminary search of 4,363 publication records, of which 812 records were from PubMed databases, 1,130 records were from Scopus databases, and 2,421 records were from ScienceDirect databases. After eliminating duplicate records, the titles and abstracts of 2,634 records were initially screened according to the inclusion criteria as shown in Table 3. After removing 1,270 ineligible records, 91 potentially relevant records were screened in full text. A total of 46 records were removed, including 5 records lacking valid data. Five publications13,14,15,16,17 that met our specific inclusion criteria and used mNGS to examine the virome in AFI plasma and serum specimens were eligible for this systematic review. The sample size of the studies included in this meta-analysis varied significantly, ranging from 12 to 816 cases. Of the five studies were cross-sectional studies. All three studies reported detailed information on the age distribution of AFI patients. The geographical distribution of the study population was two studies conducted in America, one in Africa and two in Europe. All studies used plasma or serum for the NGS method, with or without RT-PCR. The information on the studies is provided in Table 1. The proportions of viral-positive cases were reported in 70 viral species or genotypes from 24 families separated into 3 regions including America, Europe and Africa (Fig. S1).

Human anelloviruses were the most prevalent viruses detected by NGS in AFI patients

The prevalence of viral infections in AFI patients detected by the NGS method was determined through meta-analysis, with prevalence rates analyzed by viral species from the recruited patients. The random effects model meta-analysis demonstrated the estimated prevalence of viral profiles detected by NGS in AFI patients. The top twenty viruses are shown in Fig. 2. The top three most prevalent in AFI patients were human anelloviruses (AVs) from Anelloviridae family including torque teno mini virus; TTMV (20.98%), torque teno virus; TTV (20.46%) and torque teno midi virus; TTMDV (19.83%), respectively. The proportions of virus-positive AFI cases in each included study are summarized in Table S1.

The odds ratio was estimated in subgroup analysis by dividing the virus into 3 groups, including (1) Recognized clinical virus, (2) Commensal virus, and (3) Unknown clinical virus, compared with non-infection cases in each study. The human anelloviruses were assigned to the commensal virus in this analysis. The results showed that the odds ratio was 3.75 (0.27, 52.94), 0.17 (0.00, 11.86), and 0.15 (0.02, 1.39), respectively (Fig. 3a). We also analyzed the recognized clinical viruses and unknown clinical viruses compared to other viruses in each study. In this analysis, the human anelloviruses were assigned to the unknown clinical viruses. The odds ratio of recognized clinical viruses and unknown clinical viruses was 3.50 (0.11, 107.94) and 0.31 (0.01, 8.83), respectively (Fig. 3b). The results demonstrated that human anelloviruses were not associated with AFI in both parts of the commensal virus and the unknown clinical virus, suggesting they are unlikely to be etiologic agents of AFI.

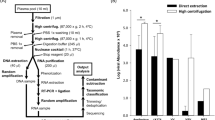

The prevalence of TTV and TTMDV was reduced in AFI patients compared to healthy blood donors

Although our meta-analysis indicates that human anelloviruses are unlikely etiologic agents of AFI, viral load has been reported to reflect immune status. To assess this relationship, we collected blood from 203 AFI patients and 100 healthy blood donors and firstly determined the prevalence of the three human anellovirus genera in PBMCs by real‑time PCR. The demographic data of all participants and dengue virus (DENV) detection rate in AFI patients by using RT-PCR are shown in Table 2. TTV prevalence was significantly lower in AFI cases (61.08%; 124/203) compared to healthy blood donors (84%; 84/100) (p-value < 0.0001) (Fig. 4a). Similarly, TTMDV prevalence was significantly lower in AFI cases (7.39%; 15/203) compared to healthy blood donors (29%; 29/100) (p-value < 0.0001) (Fig. 4b). The prevalence of TTMV was detected in only 1 sample (1%, 1/100) of healthy blood donors and 3 samples (1.48%, 3/203) of AFI cases which is not significantly different when compared between 2 groups (p-value = 0.7329) (Fig. 4c).

The prevalence (%) of human anelloviruses in healthy blood donors and AFI cases. (a) The prevalence (%) of TTV. (b) The prevalence (%) of TTMDV. (c) The prevalence (%) of TTMV. A t-test was used to compare the prevalence of TTV between the samples from AFI cases and healthy blood donors. (***; p-value < 0.001, ****; p-value < 0.0001). TTV: Torque teno virus, TTMDV: Torque teno midi virus, TTMV: Torque teno mini virus, AFI: acute febrile illness.

The presence of TTV was higher in AFI patients aged 55 and older

To assess whether the presence of human anelloviruses in healthy blood donors and AFI cases differs across different age groups, we divided the AFI cases and healthy blood donors into four age groups, including ≤ 20 years old, 21–35 years old, 36–54 years old, and ≥ 55 years old. In healthy blood donors, the TTV prevalence in ≤ 20 years old, 21–35 years old, 36–54 years old, and ≥ 55 years old was 94.74% (18/19), 75.86% (22/29), 80.49% (33/51) and 100% (11/11), respectively. Although TTV prevalence differed in age group, this difference was not significant (p-value = 0.1393) (Fig. 5a). In AFI cases, the TTV prevalence in ≤ 20 years old, 21–35 years old, 36–54 years old, and ≥ 55 years old was 45.25% (81/179), 59.38% (19/32), 59.26% (16/27) and 88.89% (8/9), respectively. The result revealed that the TTV prevalence in the ≥ 55 years old group was significantly higher compared to the ≤ 20 years old group (p-value = 0.0230) (Fig. 5b). However, the prevalence of TTMDV and TTMV in different age groups could not be analyzed because the amount of data is too small for statistical calculations.

The TTV prevalence (%) between age groups. (a) The TTV prevalence (%) between age groups of healthy blood donors. (b) The prevalence (%) of TTV among age groups of AFI cases. Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to compare the prevalence of TTV positivity across the different age groups. (*: p-value < 0.05). TTV: Torque teno virus.

The TTV load in AFI cases was lower compared to that in healthy blood donors

We examined whether there was a difference in the viral load of human anelloviruses between healthy blood donors and AFI cases. The results indicated that the mean TTV load in healthy blood donors was 6.823 log10 copies in PBMCs/mL of whole blood, whereas in AFI cases, it was 5.790 log10 copies in PBMCs/mL of whole blood. A significant difference existed between the groups (p-value < 0.0001) (Fig. 6a). The mean TTMDV load in healthy blood donors was 5.991 log10 copies in PBMCs/mL of whole blood, while in AFI cases, it was 5.857 log10 copies in PBMCs/mL of whole blood. There was no significant difference between the groups (p-value = 0.5708) (Fig. 6b). Differences in TTMV load were not tested inferentially because the number of positive samples fell below our pre‑specified threshold for statistical analysis.

We further evaluated the association between viral load and age differences in healthy blood donors and AFI cases. Although the trend of TTV load was higher in older age groups of healthy blood donors, only the mean TTV load in the 20–35 years old was significantly higher than < 20 years old (p-value = 0.0261) (Fig. S2a). In AFI cases, the mean TTV loads in different age groups were not significantly different (p-value = 0.2087) (Fig. S2b). Interestingly, when compared between healthy blood donors and AFI groups, the TTV load in 20–35 years and 36–54 years of healthy blood donors was significantly higher than in AFI cases (p-value < 0.0001) (Fig. S3). Differences in TTMDV and TTMV viral loads by age group were not tested because the number of positive samples was below our threshold for statistical analysis.

Virus loads in PBMCs from AFI cases compared to healthy blood donors. (a) TTV loads compared to healthy blood donors. (b) TTMDV loads compared to healthy blood donors. The t-test was performed to compare mean values between the groups. (****; p-value < 0.0001). TTV: Torque teno virus, TTMDV: Torque teno midi virus, AFI: acute febrile illness.

The prevalence and viral load of TTV are not associated with DENV infection

DENV infection is one of the common causes of AFI in Thailand. We therefore assessed the association between TTV-DENV co-infection with the severity of the disease. We first determined the presence of DENV in AFI cases using RT-PCR. Of 203 AFI cases, 123 cases were DENV positive. Among those TTV-positive cases, forty-three cases (34.96%, 43/123) were positive with DENV. We further determined the TTV load in TTV-DENV and TTV alone groups. Among 203 AFI samples, the mean TTV load in TTV-DENV was 5.822 log10 copies in PBMC/mL whole blood, and in TTV alone was 5.748 log10 copies in PBMC/mL whole blood. However, there was no significant difference between the two groups (p-value = 0.6174) (Fig. S4).

To assess whether TTV infection with DENV affects disease severity, we collected the complete blood count (CBC) results of AFI patients and investigated the association of TTV load with platelet counts, and hematocrit level. Platelet counts of less than 100,000 cells/µL indicate a tendency to have a more severe disease. Among TTV-DENV AFI cases, the TTV load in the group with platelet counts < 100,000 cell/µL and ≥ 100,000 cell/µL were 5.654 log10 copies in PBMC/mL whole blood and 5.962 log10 copies in PBMC/mL whole blood, respectively. No significant difference was found (p-value = 0.3020) (Fig. S5). Therefore, we suggest that the TTV load is not associated with the severity of dengue fever. Unfortunately, we did not have the patient samples with increased hematocrit level greater than 20%, which is a sign of hemoconcentration and precedes shock. Thus, we could not analyze the correlation of TTV load with the level of hematocrit.

The TTV load was correlated with total white blood cell (WBC), neutrophil and lymphocyte levels

TTV has been explored as a functional marker of the immune system in patients with inflammatory disorders. We therefore studied whether TTV load is related to the immune status of AFI patients. We first determined the association of TTV load with total WBC levels. From the CBC results, we divided AFI patients without DENV infection into three groups according to the total WBC count including low WBC (< 4,500 cells/mL), normal WBC (4,500 − 10,000 cells/mL), and high WBC (> 10,000 cells/mL). The results showed that TTV load in AFI patients in the low WBC group was 5.501 log10 copies in PBMC/mL whole blood, in the normal WBC group was 5.986 log10 copies in PBMC/mL whole blood, and in the high WBC group was 6.636 log10 copies in PBMC/mL whole blood. The TTV load in the low WBC group was significantly lower than in the normal WBC group and high WBC group (p-value = 0.0024) (Fig. 7a).

We next categorized AFI patients without DENV infection based on neutrophil levels into three groups: low (< 50%), normal (50–70%), and high (> 70%). The TTV loads measured were 5.479, 5.952, and 6.417 log10 copies in PBMC/mL whole blood for low, normal, and high neutrophils, respectively. Notably, TTV loads were significantly higher in the high-neutrophil group compared to the low-neutrophil group (p < 0.0069) (Fig. 7b). Lastly, based on the lymphocyte level included low (< 20%), normal (20–40%), and high (> 40%). TTV loads were 6.483, 5.978, and 5.049 log10 copies in PBMC/mL of blood for low, normal, and high lymphocytes, respectively. TTV loads in the low and normal lymphocyte groups were significantly higher than in the high lymphocyte group (p < 0.0005) (Fig. 7c).

The TTV load in different levels of total WBCs, neutrophils and lymphocytes. (a) The TTV load between WBC level groups in AFI patients without dengue virus co-infection cases. (b) The TTV loads between neutrophil level groups in AFI patients without dengue virus co-infection cases. (c) The TTV loads between lymphocyte level groups in AFI patients without dengue virus co-infection. (*; p-value < 0.05, **; p-value < 0.01). WBC: white blood cell, PBMC: peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic literature review and meta-analysis on AFI studies that used mNGS to examine the virome in plasma or serum specimens. Although we applied lenient inclusion criteria, only a few studies were eligible for our systematic review—five studies with a total of 1,006 patients diagnosed with AFI from three continents, notably, none were conducted in Asia. The results revealed that human anelloviruses including TTV, TTMDV and TTMV were the most prevalent, detected in approximately 20% of AFI patients. Following human anelloviruses, our systematic review found that mNGS detected many fever-causing viruses, notably Zika, dengue, and chikungunya viruses. However, one eligible study included in our analysis was conducted during the Zika outbreak in Bahia, Brazil14. Therefore, AFI patients who were admitted for treatment had a higher incidence of Zika virus than normal. Although anelloviruses, especially TTV, were the most frequently detected in AFI cases, they are considered commensal members of the human virome and are not known to cause pathology in humans18. In this exploratory study, our subgroup analyses suggested that human anelloviruses were not associated with AFI in both parts of the commensal virus and the unknown clinical virus. These results are consistent with previously reported studies, which still lack clarity regarding the role of anelloviruses in human disease19,20. However, the risk of coinfection should not be ignored. As previous studies reported, TTV coinfection with common respiratory virus (CRV) can lead to greater severity21. Our meta-analysis presents some limitations. First, differences were observed among the studies, including geographical, gender, and age. Second, the subgroup analyses for geographic, gender, and age were not conducted due to a lack of data. Third, a funnel plot and Egger’s test for each meta-analysis were not constructed according to the studies included in this meta-analysis are less than 10 according to the PRISMA guidelines 2020.

Although our sample population was limited to Northeastern Thailand and may not represent other populations, the observed TTV prevalence and viral load were consistent with previous studies reporting high prevalence20,22,23. According to our findings, 84% of healthy blood donors were positive with TTV, comparable to a prior study conducted in Qatar which reported 83.4% of TTV-positive in the healthy population24. The TTMDV prevalence in the healthy blood donors in this study was 29%, which is lower than the prevalence reported in the control group of the studies from Qatar (61.2%)24 and Romania (46.4%)25. The TTMV prevalence in healthy blood donors was as few as 1%, which is different from the prevalence in healthy people from Qatar and Romania reported as 74.6% and 32.1%, respectively24,25. The relatively low prevalence of TTMV is not surprising due to a previous report from an Asian representative study of healthy Korean individuals that detected 24% TTMV26, and relatively low TTMV prevalence has also been reported in healthy Italian individuals at 8.6%27.

Our findings demonstrated that TTV prevalence in AFI patients was comparable to the prevalence of TTV reported in COVID-19 patients at 59%28 and to the study in a group of patients with pathologies linked to low-grade inflammation or alteration of carbohydrate metabolism in Romania (73.4%)25. TTMDV prevalence was lower when compared to the previous study of patients infected with HBV or HCV in Qatar (98.1% and 88.7%, respectively)24. TTMV prevalence was lowest compared to the other two viruses. However, a low prevalence of TTMV has been previously reported in chronic periodontitis patients and periodontally healthy subjects detected in 6.00% and 1.33%, respectively29.

Our results revealed that the mean TTV load in AFI patients was significantly lower compared to healthy blood donors, which is an intriguing and novel finding. This observation contrasts with some previous reports indicating that patients generally have higher TTV levels than healthy donors31,32. Several possible explanations may account for this discrepancy. One possibility is that AFI triggers an activated immune response that transiently suppresses TTV replication. TTV has often been described as a commensal virus whose replication is closely linked to host immune status, and prior research has suggested that TTV load tends to rise in states of immunosuppression, such as in solid organ transplantation patients or HIV patients32,33,34. By contrast, during acute immune activation—such as the febrile and inflammatory responses observed in AFI—innate and adaptive immune mechanisms may restrict viral replication, resulting in reduced viral loads.

Our additional analyses support this interpretation, as we observed correlations between TTV load and several immune parameters. Specifically, TTV load was higher in AFI patients with elevated total white blood cell counts and neutrophil levels, but significantly lower in those with higher lymphocyte counts. The inverse correlation with lymphocyte levels suggests that TTV may dynamically reflect the immune cell activity during acute infection. The observed decline of TTV load may represent an immune-mediated clearance or control of the virus during febrile illness. This interpretation is consistent with a report demonstrating that the replication rate of anelloviruses may serve as a measure of overall host immune function35, as well as with studies in which elevated TTV loads were associated with immunosuppression in transplant recipients36,37,38,39,40 and in HIV-infected patients32. Conversely, lower TTV loads have been associated with immunocompetence and humoral vaccine responses, as reported in studies of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in lung transplant recipients12,41. To the best of our knowledge, although a previous study conducted in Thailand reported that anelloviruses were identified in blood and serum samples of patients with AFI30, our study is the first to specifically report the association of TTV load with the level of the total white blood cells, neutrophils and lymphocytes in a Thai cohort. However, our analysis was limited to the immune cell level without the final clinical diagnosis data of the patients because the specimens were obtained as part of dengue virus surveillance program and individual clinical follow‑up data were not provided to our study. We therefore note the absence of confirmed final diagnoses as a limitation of the study in participants.

We also observed that TTV load tended to increase with age in both AFI patients and healthy donors, although the differences were not statistically significant, consistent with previously published studies42. Notably, within the age groups 20–35 years and 36–54 years, TTV loads in healthy donors were significantly higher than in AFI patients.

To investigate potential interactions with specific pathogens, we examined co-infection between TTV and DENV. Among TTV-positive cases, the mean TTV load in TTV–DENV co-infected patients was not significantly different from cases with TTV alone. Furthermore, no differences in TTV load were detected between dengue patients with low versus normal platelet counts, indicating no association between TTV levels and dengue severity. While co-infection with TTV has been reported to exacerbate other diseases, such as COVID-19, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and respiratory viral infections21,28,43, our data provide no evidence for such a role in AFI or dengue.

Taken together, our systematic review and meta-analysis confirmed the high prevalence of human anelloviruses in AFI patients. Our findings in patient samples indicated that TTV load is more likely a surrogate marker of immune activation during febrile illness rather than a direct pathogen. This supports the hypothesis that TTV load serves as a predictive biomarker of immune status. Further investigation is needed to clarify the potential clinical value of the TTV DNA load in blood, which might be used as a predictive biomarker for the effective management of AFI patients.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

The systematic literature review and meta-analysis were undertaken according to PRISMA guidelines44. Literature was retrieved from three databases including PubMed, Scopus, and ScienceDirect. For unbiased results in the article searching strategy, we performed combinations of word variants (“acute febrile illness” OR “acute unexplained illness” OR “fever of unknown origin”) AND (“virus” OR “viral” OR “virome”), restricted to the English language. The search was performed without regard to geography and was limited to studies of humans. Restriction to studies published from 2012 onward that used mNGS and other viral sequencing technologies. Eligible studies were observational (cohorts and retrospective studies), using mNGS to characterize the virome in human plasma and serum samples from AFI patients (Table 2). The searches were conducted between August to September 2023. Three reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of identified studies and then analyzed the shortlisted studies in full text for eligibility. Case reports/series, reviews and animal studies were omitted based on exclusion criteria (Table 3).

Data extraction and quality assessment

The extracted data included publication authors, year and geographical locations, study design, study participants, age, sample type, virus detection method, virus identification, and the number of virus-positive cases per total cases. We divided the viral profile into 3 groups17: (1) Viruses of clinical significance, i.e. viruses that are recognized as disease-causing pathogens in clinical practice and known to infect humans (2) Commensal viruses, i.e. viruses that infect humans and clinical relevance is unknown (3) Viruses of unknown clinical significance, i.e. viruses that are not commonly recognized to infect people and/or have never met Koch’s postulates, which would assign a potentially pathogenic role. To determine the quality of the included studies, three reviewers independently assessed the quality of the included studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) (Table S2). The total score was 9, where studies with a score of ≥ 7 were judged as high quality, 4–6 as moderate quality, and ≤ 3 as low quality.

Sample population

Peripheral blood samples were obtained as leftover specimens from the previous studies, collected from 203 AFI patients (axillary temperature ≥ 37.5 °C or self-reported fever) who presented to hospitals in Northeastern Thailand—including the provinces of Roi Et, Maha Sarakham, Khon Kaen, and Kalasin between June 2016 and June 201945,46,47. AFI patients aged 5 years or more presenting with a fever are eligible participants in this study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and a parent and/or legal guardian if the participants are minors. Subjects who are < 5 years of age and not able to sign the consent form due to severe symptoms, for example, shock, brain damage, liver failure or unconsciousness, are excluded from this study. For healthy blood donors, 100 whole blood samples were collected from the Central Blood Bank, Srinagarind Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University. All experimental protocols were approved by the Khon Kaen University Ethics Committee for Human Research and conducted in accordance with national guidelines.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolation and nucleic acid extraction

A 6 mL whole blood sample from AFI patients and healthy donors was collected in heparin tubes to perform a separation using Lymphoprep solution (STEMCELL Technologies Singapore Pte Ltd) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) layer was washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) through centrifugation at 300 xg for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in CELLBANKER cell freezing media (AMS Biotechnology Ltd., Europe) and stored at −80 ◦C until use. Total nucleic acid was extracted from PBMC samples by using a TES buffer. Three hundred microliters of TES buffer were added to the cell pellet for cell lysis and briefly vortexed. Then, 5 µL of 20 mg/mL of RNase A was added. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Thirty microliters of 20 mg/mL Proteinase K were added and incubated at 56 °C for 30 min. Two hundred microliters of protein precipitation buffer were added and mixed by inverting. The cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 16,000 ×g for 5 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was collected. One volume of isopropanol was added and incubated at −70 °C for 1 h. The mixture was centrifuged at 16,000 ×g for 15 min at 4 °C to pellet DNA, which was then washed twice with 500 µL 70% ethanol and pelleted by centrifugation at 16,000 ×g, 5 min, 4 °C). and centrifugation at 16,000 x g for 5 min at 4 °C. The DNA pellet was dried at 37 °C for 5 min, resuspended in 20 µL nuclease-free water, and stored at − 20 °C.

Human anellovirus detection

TTV, TTMV, and TTMDV DNA were detected by quantitative real-time PCR (QuantStudio™ 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) in individual samples using the 5′UTR-based degenerate primers described in the previous publication48. The PCR amplification was performed using the SsoAdvanced™ Universal SYBR ® Green Supermix DNA Polymerase (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., California, USA). In a total reaction volume composed of 50 ng of individual DNA samples, 250 nM of each specific primer. For TTV and TTMV detection, the amplifications were performed for 35 cycles with the following parameters: denaturation at 94 °C, annealing at 57 °C, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. For TTMDV detection, the amplifications were performed for 35 cycles with the following parameters: denaturation at 94 °C, annealing at 59 °C, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. Three synthetic oligonucleotides were used as a positive control to detect human anelloviruses. Nucleotide sequences were received from NCBI with reference numbers following the prototype TTV isolate of TA278 (AB017610), TTMV isolate of CBD231 (AB026930), and TTMDV isolate of MD1-073 (AB290918) (Table S3). TTV and TTMV control were synthesized in the pUC57 vector, while TTMDV was synthesized in the PCU57-1800k vector. SnapGene® software version 7.0.3 (https://www.snapgene.com) was used to determine if the specific primers could bind to the vector positive control. TTV, TTMV and TTMDV loads were quantified within a linear range from 2 to 10 log10 copies in PBMC/mL whole blood, as determined by the use of ten-fold dilutions of a plasmid standard. The limit of detection was 2 log10 copies in PBMC/mL whole blood. We used this information to calculate the comparative viral copy number in our study. Standard curves for TTV, TTMV and TTMDV quantification are shown in Fig. S6-S8, respectively. To evaluate potential PCR inhibition, each DNA extract was assessed with GAPDH as an endogenous control49.

Statistical analysis

The viral prevalence from meta-analysis in this study was calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values for viruses present in AFI patients using random‐effects models due to the heterogeneity of study populations. Statistical heterogeneity was explored using Cochrane’s Q Test (χ 2) and the I2 statistic, which indicates the proportion of variance of the summary effect attributable to between‐study heterogeneity. A p-value < 0.10 was considered a statistically significant heterogeneity, while I2 ≤ 25% and ≥ 75% were deemed low and high heterogeneity, respectively. Sensitivity and influence analyses were conducted based on the study size. Data analysis was completed in Review Manager Version 5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration).

For our study, ANOVA tests were performed to analyze the general effect of the age groups on viral load, and to determine the specific changes between the age groups, the Mann-Whitney test was used. To analyze the mean viral loads within two groups, an unpaired t-test was used. For all statistical analyses, GraphPad Prism version 8.4.3 (GraphPad Software Inc., USA) was used. For all tests, p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Mendeley repository, https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/m5wyp77v8t/250.

Change history

30 January 2026

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37465-3

References

Capeding, M. R. et al. Dengue and other common causes of acute febrile illness in asia: an active surveillance study in children. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7(7), e2331 (2013).

Susilawati, T. N. & McBride, W. J. Acute undifferentiated fever in asia: a review of the literature. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health. 45 (3), 719–726 (2014).

Niven, D. J. & Laupland, K. B. Pyrexia: aetiology in the ICU. Crit. Care. (London, England). 20 (1), 247 (2016).

Wangdi, K. et al. A. Diversity of infectious aetiologies of acute undifferentiated febrile illnesses in South and Southeast asia: a systematic review. BMC Infect. Dis. 19 (1), 577 (2019).

Mourya, D. T. et al. Emerging/re-emerging viral diseases & new viruses on the Indian horizon. Indian J. Med. Res. 149 (4), 447–467 (2019).

Casel, M. A., Park, S. J. & Choi, Y. K. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus: emerging novel phlebovirus and their control strategy. Exp. Mol. Med. 53 (5), 713–722 (2021).

Behjati, S. & Tarpey, P. S. What is next generation sequencing? Archives Disease Child. Educ. Pract. Ed. 98 (6), 236–238 (2013).

Kuczaj, A., Przybyłowski, P. & Hrapkowicz, T. Torque Teno virus (TTV)-A potential marker of immunocompetence in solid organ recipients. Viruses 16 (1), 17 (2023).

van Rijn, A. L., Roos, R., Dekker, F. W., Rotmans, J. I. & Feltkamp, M. Torque Teno virus load as marker of rejection and infection in solid organ transplantation - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Med. Virol. 33 (1), e2393 (2023).

Berg, R. et al. Kinetics of torque Teno virus in heart transplant patients. Hum. Immunol. 84 (12), 110720 (2023).

Görzer, I. et al. Pre-transplant plasma torque Teno virus load and increase dynamics after lung transplantation. PloS One 10(3), e0122975 (2015).

Focosi, D., Baj, A., Azzi, L., Novazzi, F. & Maggi, F. TTV viral load as a predictor of antibody response to SARS COV-2 vaccination. J. Heart Lung Transplantation: Official Publication Int. Soc. Heart Transplantation. 42 (2), 143–144 (2023).

Yozwiak, N. L. et al. Virus identification in unknown tropical febrile illness cases using deep sequencing. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6 (2), e1485 (2012).

Sardi, S. I. et al. Coinfections of Zika and Chikungunya viruses in Bahia, Brazil, identified by metagenomic next-generation sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 54 (9), 2348–2353 (2016).

Williams, S. H. et al. Investigation of the plasma Virome from cases of unexplained febrile illness in Tanzania from 2013 to 2014: a comparative analysis between unbiased and VirCapSeq-VERT high-throughput sequencing approaches. mSphere 3 (4), e00311–e00318 (2018).

Jerome, H. et al. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing aids the diagnosis of viral infections in febrile returning travellers. J. Infect. 79 (4), 383–388 (2019).

Cordey, S. et al. Blood virosphere in febrile Tanzanian children. Emerg. Microbes Infections. 10 (1), 982–993 (2021).

Bernardin, F., Operskalski, E., Busch, M. & Delwart, E. Transfusion transmission of highly prevalent commensal human viruses. Transfusion 50 (11), 2474–2483 (2010).

De Vlaminck, I. et al. Temporal response of the human Virome to immunosuppression and antiviral therapy. Cell 155 (5), 1178–1187 (2013).

Rezahosseini, O. et al. Torque-Teno virus viral load as a potential endogenous marker of immune function in solid organ transplantation. Transplantation Reviews (Orlando Fla). 33 (3), 137–144 (2019).

Del Rosal, T. et al. Torque Teno virus in nasopharyngeal aspirate of children with viral respiratory infections. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 42 (3), 184–188 (2023).

Okamoto, H. History of discoveries and pathogenicity of TT viruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 331, 1–20 (2009).

Burra, P. et al. Torque Teno virus: any pathological role in liver transplanted patients? Transpl. International: Official J. Eur. Soc. Organ. Transplantation. 21 (10), 972–979 (2008).

Al-Qahtani, A. A. et al. Prevalence of anelloviruses (TTV, TTMDV, and TTMV) in healthy blood donors and in patients infected with HBV or HCV in Qatar. Virol. J. 13 (1), 208 (2016).

Spandole-Dinu, S. et al. Prevalence of human anelloviruses in Romanian healthy subjects and patients with common pathologies. BMC Infect. Dis. 18 (1), 334 (2018).

Chong, Y., Lee, J. Y., Thakur, N., Kang, C. S. & Lee, E. J. Strong association of torque Teno virus/Torque Teno-like minivirus to Kikuchi-Fujimoto lymphadenitis (histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis) on quantitative analysis. Clin. Rheumatol. 39 (3), 925–931 (2020).

Andreoli, E. et al. Small anellovirus in hepatitis C patients and healthy controls. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12 (7), 1175–1176 (2006).

Stincarelli, M. A. et al. Plasma Torquetenovirus (TTV) MicroRNAs and severity of COVID-19. Virol. J. 19 (1), 79 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. X. P. A novel species of torque Teno mini virus (TTMV) in gingival tissue from chronic periodontitis patients. Sci. Rep. 6, 26739 (2016).

Jitvaropas, R. et al. Identification of bacteria and viruses associated with patients with acute febrile illness in Khon Kaen Province, Thailand. Viruses 16 (4), 630 (2024).

Batista, A. M. et al. Quantification of torque Teno virus (TTV) DNA in saliva and plasma samples in patients at short time before and after kidney transplantation. J. Oral Microbiol. 14 (1), 2008140 (2021).

Schmidt, L. et al. Torque Teno virus plasma level as novel biomarker of retained immunocompetence in HIV-infected patients. Infection 49 (3), 501–509 (2021).

Albert, E. et al. The kinetics of torque Teno virus plasma DNA load shortly after engraftment predicts the risk of high-level CMV dnaemia in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transpl. 53 (2), 180–187 (2018).

Lapa, D. et al. Clinical relevance of torque Teno virus (TTV) in HIV/HCV coinfected and HCV monoinfected patients treated with direct-acting antiviral therapy. J. Clin. Med. 10 (10), 2092 (2021).

Kulifaj, D. et al. Development of a standardized real time PCR for torque Teno viruses (TTV) viral load detection and quantification: A new tool for immune monitoring. J. Clin. Virol. 105, 118–127 (2018).

Maggi, F. et al. Early Post-Transplant Torquetenovirus viremia predicts cytomegalovirus reactivations in solid organ transplant recipients. Sci. Rep. 8 (1), 15490 (2018).

Mafi, S. et al. Torque Teno virus viremia and QuantiFERON®-CMV assay in prediction of cytomegalovirus reactivation in R + kidney transplant recipients. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 10, 1180769 (2023).

Velleca, A. et al. The international society for heart and lung transplantation (ISHLT) guidelines for the care of heart transplant recipients. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 42 (5), e1–e141 (2023).

Görzer, I., Haloschan, M., Jaksch, P., Klepetko, W. & Puchhammer-Stöckl, E. Plasma DNA levels of torque Teno virus and immunosuppression after lung transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplantation: Official Publication Int. Soc. Heart Transplantation. 33 (3), 320–323 (2014).

Jaksch, P., Görzer, I., Puchhammer-Stöckl, E. & Bond, G. Integrated Immunologic monitoring in solid organ transplantation: the road toward torque Teno virus-guided immunosuppression. Transplantation 106 (10), 1940–1951 (2022).

Hoek, R. A. et al. High torque tenovirus (TTV) load before first vaccine dose is associated with poor serological response to COVID-19 vaccination in lung transplant recipients. J. Heart Lung Transplantation. 41 (6), 765–772 (2022).

Haloschan, M. et al. TTV DNA plasma load and its association with age, gender, and HCMV IgG serostatus in healthy adults. Age (Dordrecht Netherlands). 36 (5), 9716 (2014).

Xie, Y. et al. Associations between sputum torque Teno virus load and lung function and disease severity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Front. Med. 8, 618757 (2021).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. & PRISMA group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6(7), e1000097 (2009).

Overgaard, H. J. et al. Assessing dengue transmission risk and a vector control intervention using entomological and immunological indices in thailand: study protocol for a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Trials 19 (1), 122 (2018).

Fustec, B. et al. Complex relationships between Aedes vectors, socio-economics and dengue transmission-Lessons learned from a case-control study in Northeastern Thailand. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14(10), e0008703 (2020).

Nonyong, P. et al. Dengue virus in humans and mosquitoes and their molecular characteristics in Northeastern Thailand 2016–2018. PLoS One. 16 (9), e0257460 (2021).

Ninomiya, M., Takahashi, M., Nishizawa, T., Shimosegawa, T. & Okamoto, H. Development of PCR assays with nested primers specific for differential detection of three human anelloviruses and early acquisition of dual or triple infection during infancy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46 (2), 507–514 (2008).

Malat, P. et al. Andrographolide inhibits epstein-barr virus lytic reactivation in EBV-positive cancer cell lines through the modulation of epigenetic-related proteins. Molecules 27 (14), 4666 (2022).

Aromseree, S., Angwong, C. & Project Virome profile in acute febrile illness patients using metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing: A systematic review, meta-analysis and Torque Teno Virus abundance in Northeastern Thailand: Mendeley Data, V2;. (2025). https://doi.org/10.17632/m5wyp77v8t.2

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the scholarship support from the Graduate School of Khon Kaen University and the Invitation Research from the Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Thailand. Importantly, we would like to thank all teaching staff in the Department of Microbiology, and staff of the Central Blood Bank, Srinagarind Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, for their assistance in this project.

Funding

This study was supported by the Graduate School, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand and the Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand (grant number IN66039).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.A. - completed the sample collection, design and performed experiments, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, writing-review & editing, and wrote the manuscript’s text. C.P. and T.E. - conceived the study, advised, interpreted the data, and provided resources. A.B. - provided statistical advice and interpreted the data. P.T. - provided equipment and formed experimental design advice. H.J.O. - provided additional experimental samples and advice. S.A. - conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, experimental design, analyzed the results, advice, supervision, review & editing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethic declaration

Sample collection from AFI patients (approval no. HE591099) and healthy blood donors (approval no. HE661015), along with all experimental protocols, were approved by the Khon Kaen University Ethics Committee for Human Research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in Figure 3. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Angwong, C., Pientong, C., Ekalaksananan, T. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of virome profiles and quantification of Torque teno virus load in blood of acute febrile illness patients. Sci Rep 15, 45340 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29413-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29413-4